Abstract

Introduction:

The pandemic caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), or coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has affected many people in the world and has impacted the physical, social, and mental health of the world population. One of these psychological consequences is intimate partner violence affecting sexual health.

Methods:

This study was performed as a systematic review on the effect of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic on sexual function and domestic violence in the world. Accordingly, all English-language studies conducted from the beginning of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic to the end of 2020 were extracted by searching in the Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed (including Medline), Cochrane Library, and Science Direct databases and then reviewed. The quality of the articles was assessed using the STROBE checklist.

Results:

A total of 11 studies were included in the systematic review. Accordingly, domestic violence during the exposure to COVID-19 had increased. Moreover, the mean scores of sexual function and its components had reduced at the time of exposure to the pandemic compared to before.

Conclusion:

Given the potential long-term effects of the coronavirus crisis and the large population being affected by this disease, strategies to promote sexual health and fertility of families to prevent or further reduce violence and sexual functions should be chosen.

Keywords: COVID-19, intimate partner violence, pandemic, sexual function, systematic review

Introduction

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), a new coronavirus infection that was discovered in Wuhan, China in December 2019, has now been declared by the World Health Organization (Geneva, Switzerland) as a pandemic that has led to wide-spread panic and anxiety around the world.1 As the death toll from the spread of the virus has risen around the world, governments have imposed quarantines or social isolation in communities to protect lives. Following these restrictions, people in the community experienced sudden changes in their daily lives, and as a result, they limited their work activities. Consequently, as people decrease social interactions and increase the number of hours they stay at home, they may experience increased levels of anxiety and stress.2 Previous studies have pointed out that major epidemics in the world have had a significant psychological burden on individuals.3

Increased mortality from the COVID-19 pandemic and drastic measures to enforce restrictions have led to an increase in psychological outcomes in different populations in most societies.4 One of the behaviors that may be affected by quarantine and social distancing is sexual intercourse.5 According to the definition of the World Health Organization, sexual health requires a positive and respectful approach to sexual desires and relationships, as well as having pleasant and safe sexual experiences, free from coercion, discrimination, and violence.6

By virtue of restrictions imposed by various countries, as well as the general public’s fear of being infected, coronavirus outbreaks have changed social relations between individuals. These changes were such that they deprived individuals of the opportunity to adapt their physical and mental systems and put them under pressure.7 Grief caused by the prevailing conditions due to the spread of the virus, and exposure to numerous news related to the infected people and deaths, transformed people’s emotional stability. Everyday turmoil, lack of freedom of action, lack of independence, and feelings of helplessness led to feelings of disability in people, and as a result, people’s psychological distress affected their sexual activity.8 Sexual desires are complex and involve numerous phenomena that include participation, behavior, attitude, identity, orientation, beliefs, and sexual activity.5

Sex is influenced by the interaction of biological, psychological, social, economic, political, cultural, legal, historical, religious, and spiritual factors.9 Accordingly, it is logical to assume that sex life is profoundly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic at the individual and environmental levels. At the individual level, all forms of sexual contact carry the risk of transmitting the virus. Therefore, people should refrain from sexual contact for fear of transmitting the virus. At the environmental level, quarantine and social distancing can affect people’s sex lives.10

The effects of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) on human sexual and reproductive function, including whether or not the virus crosses the blood-barrier testicles and ovaries, or whether it affects the production of sex hormones, are still unknown.11 However, fear of virus transmission is one of the consequences of the spread of coronavirus in communities, which leads to changes in sexual function and behavior in couples. In this case, the couple, due to fear of infection, limit and in some cases cut off physical contact from a simple kiss to full sexual intercourse. Also, long-term home quarantine and longer couples’ contacts within 24 hours lead to an increase in marital conflicts and thus intensifies negative feelings.12 Moreover, the constant presence of children or other family members on the one hand and mandatory restrictions on the other hand led to the loss of privacy of couples and can exacerbate the problems in this area.13

The results of a study comparing sexual behaviors among women in Turkey showed that although sexual desire and frequency of intercourse increased significantly during the COVID-19 pandemic, the quality of sexual life decreased significantly. This pandemic has been associated with decreased desire for pregnancy, decreased contraception in women, and increased menstrual disorders.14

Another consequence of the coronavirus pandemic is concerns about an increase in violence, including sexual violence. In many countries, governments have used housing policy extensively to control the effects of the virus, which has raised many concerns. Many international organizations have stated that housekeeping policy increases violence against women, and this is based on the effects of the previous SARS pandemic on increasing sexual partner violence against women.15,16

Although the COVID-19 pandemic is a new disease that has led to global effects on human life around the world and requires further studies in various fields, given the importance of sexual health in promoting health and the fertility of communities, studying the field of sexual life during this pandemic seems necessary. Therefore, the present study was to investigate the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic with sexual function and intimate partner violence as a systematic review of the world.

Material and Methods

This study was a systematic review conducted to investigate the association between the COVID-19 pandemic with intimate partner violence and sexual function. The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) standard guideline was used to follow up the review process and report findings.17

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

This review focused on studies about intimate partner violence and sexual functions that were published in English-language journals up to the end of 2020. The databases of Scopus (Elsevier; Amsterdam, Netherlands), Web of Science (Thomson Reuters; New York, New York USA), PubMed (including Medline; National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, Maryland USA), Cochrane Library (The Cochrane Collaboration; London, United Kingdom), and Science Direct (Elsevier; Amsterdam, Netherlands) were searched using medical subject headings (MeSH) and relevant keywords, including: “Sexual Behavior,” “Sexual function,” “Sexually function,” “partnered sexual behaviors,” “sexuality,” “sexual dysfunction,” “Intimate partner violence,” “Domestic violence,” “sexual activity,” “COVID-19,” “COVID-19 virus,” “coronavirus disease 2019,” “SARS-CoV-2,” “pandemic,” and “outbreak.” They were used in isolation or in combination through the Boolean method.

Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

All English-language articles published in the world on disasters and domestic violence or sexual function and COVID-19 which were of high quality entered the study. Articles of low quality, studies conducted on other infectious diseases, people over 60 years, people without sexual activity, or people with genitourinary diseases were excluded from the study. Those articles published in non-English language were also excluded. Additionally, review studies, meta-analysis, case reports, or series of cases were excluded as well.

Quality Assessment

The quality of the articles was assessed using the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist.18 This checklist has 22 parts that are scored based on the importance of each section, the lowest score of this checklist is 15 and the maximum is 33. In this study, score 20-24 as low, score 25-29 as medium, and score upper 29 as high quality were considered.

Screening and Data Extraction

The search results were imported into the Endnote software v.x8-1 (Clarivate Analytics; Philadelphia, Pennsylvania USA) and duplicate titles were deleted. Selected studies entered the abstract reading process and were checked against the inclusion criteria. Of which, the most relevant studies were selected for independent full-text reading by two researchers (SD, JB), and a third person as the expert-epidemiologist checked the result. Reasons for the rejection of studies were mentioned, and in case of disagreement between the researchers, a third researcher evaluated the research. A checklist was used to extract data from the selected studies in terms of the sample size, study location, year of study, type of study, COVID-19 pandemic, sexual function, and intimate partner violence.

Selection of Articles

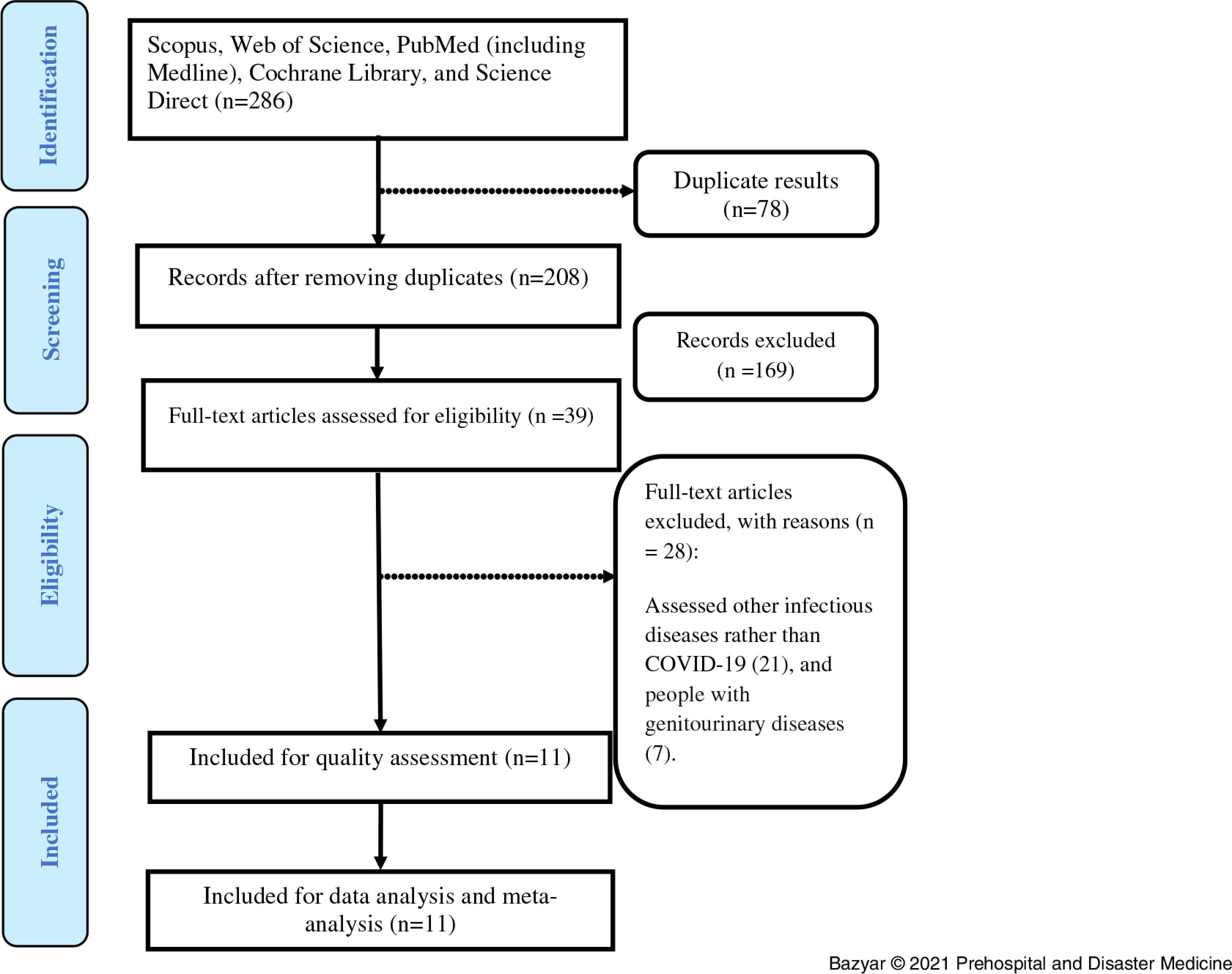

By searching databases, 286 studies were extracted. Initially, the articles were entered into Endnote software, and after an initial review, 78 articles were removed from the study due to duplication. Then, by reviewing the titles and abstracts of articles, 169 articles were removed due to irrelevance, and after reviewing the full text of articles, 28 articles were excluded due to assessing other infectious diseases rather than COVID-19 and people with genitourinary diseases. Finally, eleven articles met the inclusion criteria and entered the process of systematic review (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

The PRISMA Flow Diagram.

Abbreviation: COVID-19, coronavirus disease 2019.

Results

A total of eleven cross-sectional studies, including five studies on COVID-19 and domestic violence and six studies on COVID-19 and sexual function conducted in 2020, were included in the systematic review. The specifications of the reviewed articles are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics and Appraisal of Included Articles (n = 11)

| Author | Place of Study | Variable Investigated | Quality Level | Summary of Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jetelina KK19 | USA | Intimate Partner Violence | High | 18% prevalence of violence and 1.63-fold increase |

| Gebrewahd GT20 | Ethiopia | Intimate Partner Violence | Medium | 26.6% prevalence of violence against women |

| Sediri S21 | Tunisia | Intimate Partner Violence | Medium | 14.4% prevalence of pandemic holidays and 19.34-fold increase in violence against women who were exposed to violence before the pandemic |

| Gosangi B22 | USA | Intimate Partner Violence | High | 1.8-times more violence than before the pandemic |

| Agüero JM23 | Pro | Intimate Partner Violence | Medium | 48% increase in calls during the pandemic compared to before |

| Panzeri M13 | Italy | Sexual Function | High | Decreased sexual desire, decreased sexual intercourse, decreased sexual satisfaction, decreased orgasm |

| Hensel DJ24 | USA | Sexual Function | Medium | 22.7% decrease in hugging, kissing, and touching; 19.4% decrease in romantic sex; 8.9% decrease in sending sexually explicit messages or images by intimate partner |

| Schiavi MC2 | Italy | Sexual Function | High | Decreased score of sexual function components during pandemic compared to before |

| Fuchs A25 | Poland | Sexual Function | High | Decreased score of sexual function components during pandemic compared to before |

| Yuksel B14 | Turkey | Sexual Function | Medium | Decreased score of sexual function components during pandemic compared to before |

| Luetke M26 | USA | Sexual Function | Medium | 34% difference between sexual partners in the components of romantic relationships |

Violence and COVID-19

Domestic violence against women is one of the problems that endangers women’s health, and its elimination is one of the public health concerns in the world.27–29 In the 2020 study of Jetelina, et al in the United States, the prevalence of domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic was reported to be 18.0%. Also, changes in income and employment increased the incidence of domestic violence by 1.63-times.19 In a 2020 study by Gebrewahd, et al in Ethiopia, the prevalence of domestic violence against women during the COVID-19 pandemic was estimated at 26.6%. The prevalence of psychological violence was 13.3%, physical violence was 8.3%, and sexual violence was 5.3%.20 According to the 2020 study of Sediri, et al conducted in Tunisia, the prevalence of domestic violence against women was 4.4% before the COVID-19 pandemic and 14.4% during the holidays. Moreover, women who were exposed to violence before the COVID-19 pandemic had a 19.34-fold increased chance of encountering violence during the pandemic.21 In the 2020 study by Gosangi, et al in the United States, the incidence of physical domestic violence against women during the COVID-19 pandemic was 1.8-times higher than before.22 In a 2020 study by Agüero, et al in Peru, which examined the number of calls made to the Domestic Violence Control and Assistance Unit, the findings showed that the number of calls during the COVID-19 pandemic was increased by 48.0% compared with before the pandemic.23 In general, according to the results of the studies, it can be mentioned that the COVID-19 pandemic had increased violence against women and negatively affected their security due to various negative effects on society, including economic, psychological, and social factors.

Sexual Function and COVID-19

Another factor that has been affected by COVID-19 is sexual function in the community. According to the results of previous studies, factors such as stress, anxiety, lack of security, and health risks affected the sexual performance of men and women.13 The following is a review of the studies conducted in the world to investigate the relationship between the COVID-19 pandemic and sexual function in women and men.

In the 2020 study by Panzeri, et al in Italy, which examined the relationship between COVID-19 and sexual function in women and men, sexual desire increased in 12.1% of men and in 18.7% of women and decreased in 18.2% of men and in 26.4% of women; arousal increased in 15.2% of men and in 20.9% of women and decreased in 12.1% of men and in 20.9% of women; sexual intercourse increased in 9.1% of men and in 26.4% of women and decreased in 24.2% of men and in 30.8% of women; sexual satisfaction increased in 3.0% of men and in 13.3% of women and decreased in 6.1% of men and in 15.4% of women; and difficulty reaching orgasm decreased in 6.1% of men and in 17.6% of women. In general, study participants reported that there was not much change in their sexual function compared to before the COVID-19 pandemic.13 In a 2020 study by Hensel, et al in the United States on sexual intercourse during the COVID-19 pandemic, in 22.7% of the participants, the desire to be hugged, kissed, and touched by a sexual partner was decreased. In 19.4% of the participants, the desire of romantic sex was reduced. In addition, 8.9% were reluctant of receiving sexual or nude messages or images by a sexual partner.24 In a 2020 study by Schiavi, et al in Italy, women’s sexual performance during the COVID-19 pandemic was assessed using the Female Sexual Function Index (FSFI) questionnaire. According to the findings, the average numbers of sexual intercourse per month had decreased by 6.3-times before the COVID-19 pandemic and by 2.3-times during the pandemic. Mean score of sexual function in the time before the pandemic and at the time of the pandemic had decreased from 29.2 to 19.2, tendency from 3.8 to 3.2, arousal from 4.8 to 3.6, lubrication from 4.9 to 4.4, orgasm from 4.7 to 4.2, sexual satisfaction from 5.9 to 4.2, and pain from 4.8 to 4.5.2 In a 2020 study by Fuchs, et al in Poland, evaluation of female sexual function during the COVID-19 pandemic using the FSFI questionnaire showed that the mean score of female sexual function before the pandemic compared to the pandemic time was decreased from 30.1 to 25.8, tendency from 4.5 to 4.2, arousal from 5.1 to 4.1, lubrication from 5.4 to 4.5, orgasm from 4.8 to 3.9, sexual satisfaction from 5.2 to 4.7, and pain from 5.1 to 4.3.25 Moreover, in the 2020 study of Yuksel, et al in Turkey, the mean score of sexual function six to twelve months before the COVID-19 pandemic had decreased from 20.52 to 17.56, tendency from 3.42 to 3.94, arousal from 3.34 to 2.17, lubrication from 2.49 to 2.62, orgasm from 3.47 to 2.02, sexual satisfaction from 2.97 to 2.45, and pain from 4.83 to 4.36. However, the average numbers of sexual intercourse per week increased from 1.9 to 2.4.14 In the 2020 study by Luetke, et al in the United States, which examined differences in romantic relationships during the COVID-19 pandemic, 34.0% of the participants reported experiencing conflict in romantic relationships during the coronavirus outbreak. A comparison of the conflicts in the subsets of romantic relationships during the pandemic compared to before the pandemic showed that the frequency of hugging, kissing, cuddling, or holding hands increased by 3.2-times compared to before the pandemic. Also, masturbation decreased 3.7-times, sexual partner satisfaction or genital touch decreased 4.6-times, and vaginal sexual contact decreased 4.4-times.26 In general, based on the findings of these studies, it can be mentioned that exposure to the COVID-19 pandemic had increased the sexual dysfunction of people in the community, which could lead to family disputes, domestic violence, and mental illness.

Discussion

The findings of the present study showed that domestic violence against women increased during the coronavirus outbreak; also, the mean score of sexual function and its components including lubrication, desire, arousal, orgasm, pain, and sexual satisfaction during exposure to the COVID-19 pandemic had decreased compared to before. The results of studies have also shown that anxiety caused by facing crises or various diseases can affect sexual function in individuals. The results of a 2020 study by Jakob, et al examining the challenges of sexual therapy during the COVID-19 pandemic show that in their sample, 39.9% had sex at least once a week. Moreover, the prevalence of sexual activity in their samples was less than 40.0%.30 Lemiller, et al in their 2020 study on a population from several countries showed that 43.5% of participants reported a decrease in sexual quality along with a sharp decrease in the frequency of intercourse during forced restrictions compared to the previous year.31 An online poll also conducted during the recent COVID-19 pandemic between March and April 2020 in the UK and Spain reported that 10.0% of participants masturbated during the extraordinary quarantine.12 In another online study conducted in China in May 2020, the results showed that 30.0% of participants reported an increase in the numbers of masturbation.32 Li, et al in 2020 showed that major crises can widely lead to sexual dysfunction and reduced sexual satisfaction.32 In the 2020 study conducted by Baran, et al, 23.9% of the respondents to the questionnaire stated that they worry about the transfer of coronavirus to their spouses and that this led to a decrease in the numbers of sexual intercourse during the COVID-19 pandemic period.33 Fear of the spread of the disease, and fear of having sex with a sexual partner who works outside the home during the pandemic, led to increased anxiety and depression, and as a result, affected married life.2 In the 2020 study by Micelli, et al, it was found that more than one-third of couples who were planning to have children ignored this decision at the time of the coronavirus outbreak.34 Among the various reasons, the fear of pregnancy outcomes related to coronavirus infection led to a change in sexual function.25

Although various studies have shown positive effects of mental health on sexual function and marital quality, anxiety and panic caused by the possibility of transferring the coronavirus and the unknown definitive routes of transmission caused a variety of changes in people’s sex lives.35,36 Decreased access to physical activity, out-of-home social centers, limited access to mental health care (individual or marital therapy), and other health care services, home quarantine, and limited social interactions are some of the stressors caused by the COVID-19 pandemic.26

In addition, the present review findings showed that domestic violence had increased during the COVID-19 pandemic compared to before. The results of previous studies showed that dealing with major crises can lead to reduced access to health services and facilities, exposure to sexual violence and poverty, and vulnerability to poor reproductive and sexual health outcomes.37,38 The results of the 2020 study by Gebrewahd, et al showed that in the study population, the prevalence of violence against women by their sexual partner during the COVID-19 pandemic was 26.6%, among which psychological violence had the highest percentage (13.3%), and then physical (8.3%) and sexual (5.3%) violence were, respectively, the next ranks.20

It appears that factors such as isolation and confinement, limited access to help resources to protect individuals from violence, which has increased pressure on and control of marital relationships as a result of the spread of the coronavirus, are significant factors in the persistence of violence. Unfortunately, the public’s fear and distrust of recognizing the virus and the social policies adopted to control it have led to further harm to these individuals by putting more pressure on stressful relationships and isolating victims of violence; this isolation has jeopardized victims’ access to important psychological and social services, and led to an under-estimation of the issue of violence among those in quarantine.39–41 Prolonged home quarantine reduces peace of mind due to increased parental conflict and increases the likelihood of partner violence. Uncertainty about the future and fear of the unknown events also led to increased psychological consequences, such as stress and anxiety, followed by increased violence.42

Prior to the coronavirus outbreak, the World Health Organization estimated that 35.0% of women world-wide had experienced physical or sexual violence from their sexual partner during their lifetime. However, many strategies which are critical to ensuring the public health of the community during this dreaded disease may put people at greater risk for physical, sexual, and psychological violence.43

Limitations

Limitations of this study included: (1) the limitation of the number of studies on domestic sexual violence and sexual function; (2) previous studies have been conducted in only a few countries around the world; and (3) only English-language studies were included and relevant studies in other languages, or those without English abstract, were not included in the study.

Conclusion

Based on the findings of this systematic review, the COVID-19 pandemic has affected sexual function and intimate partner violence, a cause to sexual dysfunction, and has increased domestic violence. Regarding to the global spread of the COVID-19 pandemic, large populations are affected by this phenomenon. Accordingly, it is recommended that policy makers and health officials intervene to prevent the occurrence of these disorders through interventions such as social, economic, psychological, and health support.

Conflicts of interest/funding

none

References

- 1.Xu K, Cai H, Shen Y, et al. Management of corona virus disease-19 (COVID-19): the Zhejiang experience. Journal of Zhejiang University. 2020;49(1):147–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schiavi MC, Spina V, Zullo MA, et al. Love in the time of COVID-19: sexual function and quality of life analysis during the social distancing measures in a group of Italian reproductive-age women. Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2020;17(8):1407–1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Van Bortel T, Basnayake A, Wurie F, et al. Psychosocial effects of an Ebola outbreak at individual, community, and international levels. Bull World Health Organ. 2016;94(3):210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Omar SS, Dawood W, Eid N, Eldeeb D, Munir A, Arafat W.Psychological and sexual health during the CoViD-19 pandemic in Egypt: are women suffering more? Sex Med. 2021;9(1):100295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu H, Waite LJ, Shen S, Wang DH.Is sex good for your health? A national study on partnered sexuality and cardiovascular risk among older men and women. J Health Soc Behav. 2016;57(3):276–296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Edwards WM, Coleman E.Defining sexual health: a descriptive overview. Arch Sex Behav. 2004;33(3):189–195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ludwig S, Zarbock A.Coronaviruses and SARS-CoV-2: A Brief Overview. Anesth Analg. 2020;131(1):93–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cocci A, Presicce F, Russo GI, Cacciamani G, Cimino S, Minervini A.How sexual medicine is facing the outbreak of COVID-19: experience of Italian urological community and future perspectives. Int J Impot Res. 2020;32(5):480–482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Torales J, O’Higgins M, Castaldelli-Maia JM, Ventriglio A.The outbreak of COVID-19 and its impact on global mental health. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2020;66(4):317–320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ko N-Y, Lu W-H, Chen Y-L, et al. Changes in sex life among people in Taiwan during the covid-19 pandemic: the roles of risk perception, general anxiety, and demographic characteristics. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):5822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Simoni M, Hofmann MC.The COVID-19 pandemics: shall we expect andrological consequences? A call for contributions to ANDROLOGY. Andrology. 2020;8(3):528–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ibarra FP, Mehrad M, Mauro MD, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the sexual behavior of the population. The vision of the east and the west. Int Braz J Urol. 2020;46(suppl1):104–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Panzeri M, Ferrucci R, Cozza A, Fontanesi L.Changes in sexuality and quality of couple relationship during the Covid-19 lockdown. Front Psychol. 2020;11:565823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuksel B, Ozgor F.Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on female sexual behavior. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2020;150(1):98–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Roesch E, Amin A, Gupta J, García-Moreno C.Violence against women during covid-19 pandemic restrictions. BMJ. 2020;369:m1712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Durevall D, Lindskog A.Intimate partner violence and HIV infection in sub-Saharan Africa. World Development. 2015;72:27–42. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, et al. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. Int J Surg. 2014;12(12):1495–1499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jetelina KK, Knell G, Molsberry RJ. Changes in intimate partner violence during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic in the USA. Inj Prev. 2021. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 20.Gebrewahd GT, Gebremeskel GG, Tadesse DB.Intimate partner violence against reproductive age women during COVID-19 pandemic in northern Ethiopia 2020: a community-based cross-sectional study. Reprod Health. 2020;17(1):152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sediri S, Zgueb Y, Ouanes S, et al. Women’s mental health: acute impact of COVID-19 pandemic on domestic violence. Arch Womens Ment Health. 2020;23(6):749–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gosangi B, Park H, Thomas R, et al. Exacerbation of physical intimate partner violence during COVID-19 lockdown. Radiology. 2020:202866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Agüero JM.COVID-19 and the rise of intimate partner violence. World Dev. 2020;137:105217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hensel DJ, Rosenberg M, Luetke M, Fu T-c, Herbenick D. Changes in solo and partnered sexual behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic: findings from a US probability survey. medRxiv. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.Fuchs A, Matonóg A, Pilarska J, et al. The impact of COVID-19 on female sexual health. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(19):7152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luetke M, Hensel D, Herbenick D, Rosenberg M.Romantic relationship conflict due to the COVID-19 pandemic and changes in intimate and sexual behaviors in a nationally representative sample of American adults. J Sex Marital Ther. 2020;46(8):747–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bott S, Guedes A, Goodwin MM, Mendoza JA.Violence Against Women in Latin America and the Caribbean: A Comparative Analysis of Population-Based Data from 12 Countries. Washington, DC USA: PAHO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Peterman A, Potts A, O’Donnell M, et al. Pandemics and Violence Against Women and Children. Washington, DC USA: Center for Global Development (working paper). 2020.

- 29.Bradbury-Jones C, Isham L.The pandemic paradox: the consequences of COVID-19 on domestic violence. J Clin Nurs. 2020;29(13-14):2047–2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jacob L, Smith L, Butler L, et al. Challenges in the practice of sexual medicine in the time of COVID-19 in the United Kingdom. J Sex Med. 2020;17(7);1229–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lehmiller JJ, Garcia JR, Gesselman AN, Mark KP.Less sex, but more sexual diversity: Changes in sexual behavior during the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. Leisure Sciences. 2020:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Li G, Tang D, Song B, et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on partner relationships and sexual and reproductive health: cross-sectional, online survey study. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e20961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Baran O, Aykac A.The effect of fear of covid-19 transmission on male sexual behavior: a cross-sectional survey study. Int J Clin Pract. 2021;75(4):e13889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Micelli E, Cito G, Cocci A, et al. Desire for parenthood at the time of COVID-19 pandemic: an insight into the Italian situation. J Psychosom Obstet Gynecol. 2020;41(3):183–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Costa RM, Brody S.Sexual satisfaction, relationship satisfaction, and health are associated with greater frequency of penile–vaginal intercourse. Arch Sex Behav. 2012;41(1):9–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Flynn T-J, Gow AJ.Examining associations between sexual behaviors and quality of life in older adults. Age Ageing. 2015;44(5):823–828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Warren E, Post N, Hossain M, Blanchet K, Roberts B.Systematic review of the evidence on the effectiveness of sexual and reproductive health interventions in humanitarian crises. BMJ Open. 2015;5(12). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sohrabizadeh S, Jahangiri K, Jazani RK.Reproductive health in the recent disasters of Iran: a management perspective. BMC Pub Health. 2018;18(1):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gupta J. What does coronavirus mean for violence against women? Women’s Media Centre. 2020.

- 40.Boserup B, McKenney M, Elkbuli A.Alarming trends in US domestic violence during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. 2020;38(12):2753–2755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Parveen N, Grierson J.Warning over rise in UK domestic abuse cases linked to coronavirus. Guardian. 2020;26:3–20. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912–920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Holmes EA, O’Connor RC, Perry VH, et al. Multidisciplinary research priorities for the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for action for mental health science. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(6):547–550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]