ABSTRACT

Regulated exocytosis is an essential process whereby specific cargo proteins are secreted in a stimulus-dependent manner. Cargo-containing secretory granules are synthesized in the trans-Golgi network (TGN); after budding from the TGN, granules undergo modifications, including an increase in size. These changes occur during a poorly understood process called secretory granule maturation. Here, we leverage the Drosophila larval salivary glands as a model to characterize a novel role for Rab GTPases during granule maturation. We find that secretory granules increase in size ∼300-fold between biogenesis and release, and loss of Rab1 or Rab11 reduces granule size. Surprisingly, we find that Rab1 and Rab11 localize to secretory granule membranes. Rab11 associates with granule membranes throughout maturation, and Rab11 recruits Rab1. In turn, Rab1 associates specifically with immature granules and drives granule growth. In addition to roles in granule growth, both Rab1 and Rab11 appear to have additional functions during exocytosis; Rab11 function is necessary for exocytosis, while the presence of Rab1 on immature granules may prevent precocious exocytosis. Overall, these results highlight a new role for Rab GTPases in secretory granule maturation.

KEY WORDS: Rab GTPase, Regulated exocytosis, Secretory granule, Mucin, Salivary gland, Drosophila

Summary: Rab GTPases are critical regulators of intracellular trafficking. Here, we show that Rab1 and Rab11 localize to secretory granule membranes and regulate granule size during maturation in Drosophila salivary glands.

INTRODUCTION

Regulated exocytosis begins at the trans-Golgi network (TGN); here, cargo proteins destined for exocytosis are packaged into specialized organelles called secretory granules. After budding from the TGN, nascent granules undergo many modifications in a process called secretory granule maturation (Bonnemaison et al., 2013; Kögel and Gerdes, 2010b). One of the conspicuous modifications that occurs during maturation is an increase in secretory granule size as immature granules fuse with one another (Bonnemaison et al., 2013; Hammel et al., 2010; Kögel and Gerdes, 2010b). Secretory granule ‘growth’ has been described in a variety of mammalian professional secretory cells, including pancreatic acinar cells (Lew et al., 1994; Weintraub et al., 1992), pancreatic β-cells (Du et al., 2016), mast cells (Hammel et al., 1983, 1985), pituitary mammotrophs (Farquhar et al., 1978; Smith et al., 1966) and PC12 cells (derived from adrenal chromaffin cells) (Ahras et al., 2006; Urbé et al., 1998; Wendler et al., 2001). Although this phenomenon has frequently been observed, the molecular mechanisms that regulate secretory granule growth remain poorly understood.

Rab proteins are small GTPases that play a role in regulating nearly every aspect of intracellular trafficking, including regulated exocytosis. These proteins are highly conserved throughout eukaryotes, although the number of Rabs increases with the complexity of the organism; the yeast genome contains 11 Rab proteins, while the human genome contains at least 60 (Homma et al., 2021; Li and Marlin, 2015; Pfeffer, 2017). Rab proteins are prenylated at their C-terminus, allowing for membrane localization (Khosravi-Far et al., 1991; Kinsella and Maltese, 1991; Leung et al., 2006; Rossi et al., 1991). Inactive Rab proteins are bound to GDP and GDP-dissociation inhibitor (GDI) and localized to the cytoplasm; upon approaching their target membrane, GDI is displaced by GDI displacement factor (GDF), allowing membrane insertion of the Rab protein (Li and Marlin, 2015; Müller and Goody, 2018; Pfeffer et al., 1995; Sasaki et al., 1990; Sivars et al., 2003). The Rab protein then interacts with a cognate guanine nucleotide exchange factor (GEF), which facilitates the replacement of GDP for GTP, activating the Rab (Barr and Lambright, 2010; Blümer et al., 2013; Müller and Goody, 2018; Soldati et al., 1994; Ullrich et al., 1994). GTP-bound Rabs physically interact with their effector proteins to regulate membrane trafficking, including vesicle budding, movement and fusion, among other functions (Homma et al., 2021; Li and Marlin, 2015). Rab proteins are inactivated via interaction with GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs), which aid in catalyzing the hydrolysis of GTP to GDP, allowing the Rab to be removed from the membrane via interaction with GDI (Barr and Lambright, 2010; Garrett et al., 1993; Müller and Goody, 2018; Soldati et al., 1993; Ullrich et al., 1993). Each Rab protein is localized to specific membrane compartments, allowing these small GTPases to direct and orchestrate many of the complex trafficking events required for regulated exocytosis. Rab3D and Rab27A have previously been reported to localize to secretory granule membranes in mammalian neuroendocrine and endothelial cells, respectively, where they may play a functional role in regulating secretory granule membrane and cargo remodeling during maturation (Hannah et al., 2003; Kögel and Gerdes, 2010a; Kögel et al., 2013). However, a role for other Rab proteins in secretory granule maturation in different cell types has not been described.

The Drosophila larval salivary glands are composed of professional secretory cells that synthesize and secrete massive quantities of mucin-like ‘glue’ proteins via regulated exocytosis (Beckendorf and Kafatos, 1976; Korge, 1977). Mucin biogenesis and secretion are developmentally controlled. Biogenesis begins at the mid-third-instar larval transition, and exocytosis begins about 4 h before the onset of metamorphosis, 24 h later (Beckendorf and Kafatos, 1976; Biyasheva et al., 2001; Kang et al., 2017). Once exocytosis is complete, the mucins are expelled out of the lumen of the salivary glands and onto the surface of the animal, where they act like glue, allowing the puparium to adhere to a solid surface during metamorphosis (Biyasheva et al., 2001; Kang et al., 2017). Like secretory granules in many types of mammalian cells, these mucin-containing granules undergo a maturation process, increasing in size over time (Farkaš and Šut'áková, 1998; Neuman and Bashirullah, 2018; Niemeyer and Schwarz, 2000; Reynolds et al., 2019). Because mucin production is a developmentally controlled process consisting of a single round of biogenesis, maturation and exocytosis, we are able to view the events that occur during maturation with a high degree of temporal resolution. Moreover, fluorescent tagging of mucins (Sgs3-GFP or Sgs3-DsRED) (Biyasheva et al., 2001; Costantino et al., 2008) allows us to view these events in living tissue in real-time.

Here, we have leveraged mucin secretion in the larval salivary glands as a model system to examine the role of Rab proteins in secretory granule maturation. We screened Drosophila Rab proteins using stage- and tissue-specific RNAi knockdown for defects in secretory granule size. This screen demonstrated that RNAi knockdown of Rab1 and Rab11 resulted in a striking small-granule phenotype. We found that Rab1 and Rab11 protein localized to secretory granule membranes; Rab11 was present on granule membranes from biogenesis through secretion, while Rab1 was only present on granule membranes during the process of maturation. We also demonstrate that Rab1 and Rab11 localization to granule membranes requires GTP binding, and that Rab11 is required for recruitment of Rab1. Rab11 function is required for both maturation and exocytosis, as loss of Rab11 results in secretion defects and impairs the ability of granules to dock and fuse with the apical membrane. Finally, surprisingly, we found that small granules lacking Rab1 are able to be secreted, suggesting that Rab1 may have a role in preventing precocious secretion of immature granules. Overall, these results highlight a previously unknown role for Rab proteins on secretory granule membranes during the process of secretory granule maturation and provide new insights into the role of maturation during regulated exocytosis.

RESULTS

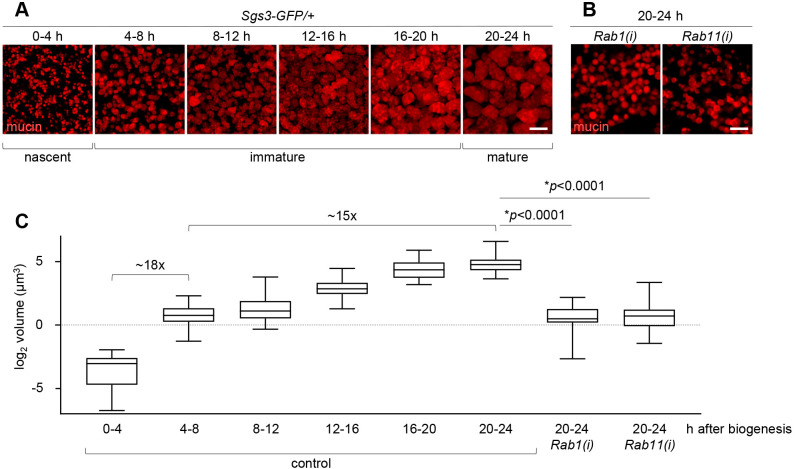

Secretory granules dramatically increase in size from biogenesis to secretion

The biogenesis of mucin-containing secretory granules in the Drosophila larval salivary glands begins when animals reach the mid-third instar larval transition and ends with secretion at the onset of metamorphosis (puparium formation) 24 h later (Beckendorf and Kafatos, 1976; Biyasheva et al., 2001). Previous work has shown that mucin-containing granules undergo a maturation process, increasing in size by fusing with one another (Farkaš and Šut'áková, 1998; Neuman and Bashirullah, 2018; Niemeyer and Schwarz, 2000; Reynolds et al., 2019). To further characterize and quantify the changes in secretory granule size that occur during this 24 h period from biogenesis to secretion, we synchronized animals at the onset of mucin biogenesis and used confocal microscopy to analyze mucin granule size in 4 h windows spanning this time period. We defined granules in the 0–4 h timepoint as ‘nascent granules’, granules in the 4–20 h period as ‘immature granules’, and granules in the 20–24 h period (when exocytosis has begun) as ‘mature granules’ (Fig. 1A). We observed that granules dramatically increased in size, with nearly a 300-fold increase in overall volume when comparing nascent versus mature granules (Fig. 1A,C). Interestingly, the single largest increase in volume occurred between the 0–4 h and 4–8 h timepoints, with an ∼18-fold change in average volume, indicating that the granules doubled in size every 1 h (Fig. 1C). Thereafter, the secretory granules doubled in size about every 4 h, with a total of ∼15-fold change in average volume between the 4–8 h and 20–24 h timepoints (Fig. 1C). This dramatic difference in growth rate between nascent granules and immature granules suggests that there may be independent regulatory mechanisms mediating each of these stages of granule growth.

Fig. 1.

Analysis of secretory granule volume during maturation. (A) Live-cell imaging of mucins (red) from staged salivary glands spanning from the onset of biogenesis (0–4 h) to the onset of exocytosis (20–24 h). Timepoints are shown in hours after biogenesis; see Materials and Methods section for a detailed description of developmental staging. Each image shows a maximum intensity projection of ten optical slices from z-stacks comprising 24–32 total slices at a step size of 0.28 µm. (B) Live-cell imaging of mucin granules (red) at the 20–24 h after biogenesis timepoint in salivary glands expressing Rab1- or Rab11-RNAi. Full genotypes: Sgs3-GFP/UAS-Rab1-RNAi; Sgs3>/+ [denoted Rab1(i)] and UAS-Rab11-RNAi/+; Sgs3-GFP/+; Sgs3>/+ [denoted Rab11(i)]. Images shown are representative of three experimental replicates with n≥10 salivary glands from independent animals analyzed per timepoint/genotype. Scale bars: 5 µm. (C) Box-and-whisker plot showing the volume of secretory granules from staged salivary glands. Z-stack imaging data was used to identify the medial cross-section of each granule for quantification. x-axis reflects the developmental stages and genotypes analyzed; y-axis shows log2-transformed volumes in µm3. Boxes outlines the 25th to 75th percentiles; middle line indicates the median. Whiskers extend to the minimum and maximum values. n=50 granules from one representative gland per timepoint/genotype. Statistics calculated with an unpaired, two-tailed t-test.

An RNAi screen for Rab proteins that regulate secretory granule size

The Drosophila genome contains 33 annotated Rab proteins (Zhang et al., 2007). To test whether any of these Rabs play a role in regulating secretory granule size, we conducted a salivary gland-specific RNAi screen and looked for a reduction in mature granule size. We used the stage- and tissue-specific Sgs3-GAL4 driver for this screen (Cherbas et al., 2003); since GAL4 expression is driven by the same promoter as mucins, we were able to examine specific effects on mucin granules without affecting development or earlier functions of the larval salivary glands. We tested each of the 30 annotated Drosophila Rab proteins that had one or more RNAi lines publicly available. This screen identified Rab1 and Rab11 as high-confidence hits with a significant reduction in secretory granule size validated by multiple independent RNAi lines (Table S1; Fig. 1B,C). We also identified Rab3, Rab5, Rab10 and Rab27 as lower-confidence hits with a moderate reduction in granule size that was only observed in a single RNAi line (Table S1). A recent study also identified Rab5 and Rab11 as regulators of mucin granule size in the larval salivary glands (Ma et al., 2020), and RAB-5 and RAB-10 have been shown to regulate neuronal dense core vesicle exocytosis in C. elegans (Sasidharan et al., 2012). Quantitative (q)PCR analysis in dissected salivary glands confirmed that Rab1-RNAi and Rab11-RNAi (Satoh, 2005) significantly reduced Rab1 and Rab11 expression levels, respectively (Fig. S1A). The terminal size of mucin granules in salivary glands expressing Rab1- or Rab11-RNAi was similar to that of controls at the 4–8 h timepoint (Fig. 1C), indicating that disruption of Rab1 or Rab11 function severely inhibits mucin granule growth. Note that because the Sgs3-GAL4 driver does not become active until the onset of mucin biogenesis, we do not expect to see a significant degree of knockdown at the 0-4 h after biogenesis timepoint and thus cannot assess a requirement for Rab1 or Rab11 function in the first stage of granule growth. Overall, these screen results highlight a novel role for Rab proteins in the regulation of secretory granule size.

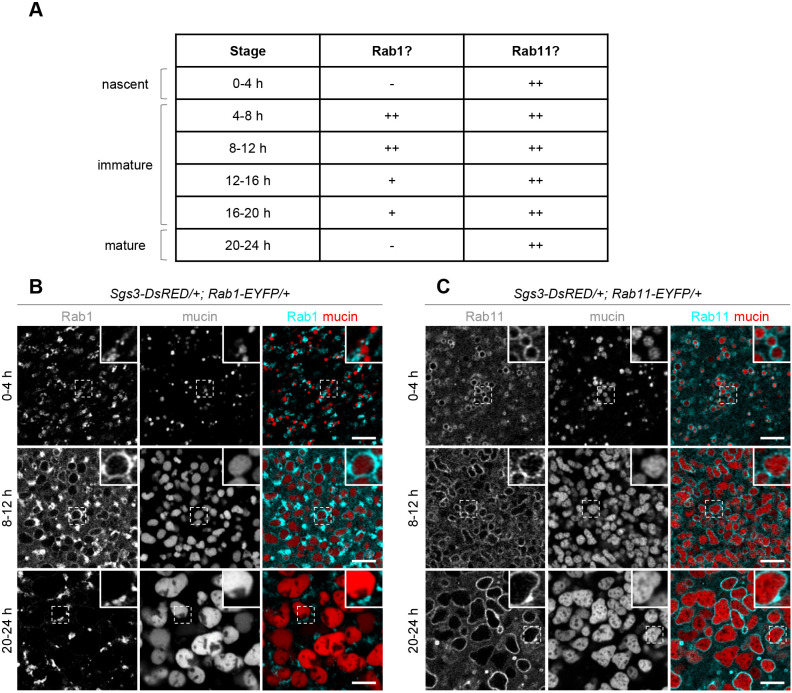

Rab1 and Rab11 localize to secretory granule membranes

Many Rab proteins localize to specific organelle membranes, and this specificity in localization allows them to carry out their roles in intracellular trafficking (Homma et al., 2021; Li and Marlin, 2015; Zhen and Stenmark, 2015). To begin to gain an understanding of how Rab proteins regulate mucin granule size, we used a collection of endogenously regulated, EYFP-tagged Rab proteins (Dunst et al., 2015) to assess the subcellular localization patterns of our screen hits in salivary glands during the 24 h time period spanning mucin biogenesis through secretion. Notably, we observed that both Rab1 and Rab11 were enriched on secretory granule membranes. Rab11 appeared to be enriched on secretory granule membranes throughout the entire 24 h period from biogenesis through secretion (Fig. 2A,C). Rab11 has typically been reported to localize to the Golgi and to recycling endosomes (Calhoun and Goldenring, 1996; Ullrich et al., 1996; Urbé et al., 1993; Welz et al., 2014; Zhen and Stenmark, 2015), and we did observe colocalization of Rab11 with a pan-Golgi marker, as well as small Rab11-positive puncta that are likely recycling endosomes (Fig. S1C), indicating that Rab11 localizes both to the expected organelles and to secretory granule membranes. Rab1, in contrast, exhibited stage-specific localization to granule membranes; Rab1 was absent from both nascent (0–4 h) and mature (20–24 h) granules but present on nearly all granules at the 4-8 h and 8-12 h timepoints and present on some granules at the 12–16 h and 16–20 h timepoints (Fig. 2A,B). Rab1 is typically thought to localize to endoplasmic reticulum exit sites (ERES), where it plays a role in promoting anterograde ER-to-Golgi trafficking (Plutner et al., 1991; Schmitt et al., 1988; Segev et al., 1988; Zhen and Stenmark, 2015). We observed colocalization of Rab1 with Sec31 (Fig. S1B), a component of the COPII coat protein complex and marker for ERES (Förster et al., 2010), indicating that Rab1 also localizes to ERES in salivary glands. A recent study also reports the presence of Rab1 and Rab11 on secretory granule membranes in salivary glands (Ma and Brill, 2021). In contrast, our lower-confidence screen hits did not appear to localize to secretory granule membranes (Fig. S2; Chan et al., 2011; Gaudet et al., 2011), suggesting that Rab1 and Rab11 may play a granule-autonomous role in regulating secretory granule size.

Fig. 2.

Association of Rab proteins with secretory granules during maturation. (A) Summary table showing a qualitative analysis of the presence of Rab1 and Rab11 on secretory granule membranes in staged salivary glands. ++ indicates the protein is present on most granule membranes, + indicates the protein is present on some granule membranes, and – indicates that the protein is not present on granule membranes. See Materials and Methods for criteria used to define localization categories. Developmental stages are shown in hours after biogenesis. The time course analysis was repeated three times with n⩾10 glands from independent animals imaged per timepoint/genotype. Representative images from three of these timepoints are shown in B and C. (B) Live-cell imaging analysis of Rab1–EYFP (cyan) localization with mucins (red). Rab1 is absent from granule membranes at 0–4 h after biogenesis, present at 8–12 h after biogenesis, and absent at 20–24 h after biogenesis. Images shown are a single slice from a z-stack comprising three slices at a 0.30 µm step size. The boxed area is magnified in the upper right corner of each image. (C) Live-cell imaging analysis of Rab11-EYFP (cyan) localization with mucins (red). Rab11 is present on granule membranes at 0-4, 8-12, and 20-24 h after biogenesis. Images shown are a single slice from a z-stack comprising ten slices at a 0.31 µm step size. The boxed area is magnified in the upper right corner of each image. Scale bars: 5 µm.

GTP binding is required for Rab1 and Rab11 localization and function in maturation

Rab protein function is dependent on binding to GTP; only GTP-bound Rab proteins can recruit their effector proteins to carry out their biological functions (Homma et al., 2021; Li and Marlin, 2015). To examine the role of GTP binding in Rab1 and Rab11 function during mucin granule maturation, we overexpressed YFP-tagged dominant negative Rab1 and Rab11 specifically in the salivary glands using the Sgs3-GAL4 driver. These dominant-negative constructs contain a point mutation that changes a serine in the GTP-binding domain to an asparagine, effectively preventing association with GTP (Zhang et al., 2007). Localization analysis showed that Rab1DN–YFP was absent from secretory granule membranes at the 8–12 h timepoint (Fig. 3B), when wild-type Rab1–EFYP is highly enriched on secretory granule membranes (Fig. 3A). Similarly, Rab11DN–YFP did not appear enriched on secretory granule membranes at the 8–12 h timepoint (compare Fig. 3C versus D). These results suggest that GTP binding is required for localization of Rab1 and Rab11 to secretory granule membranes. We did find that expression of the Rab11DN–YFP construct was delayed compared to Rab1DN–YFP; Rab1DN–YFP was barely detectable at 0–4 h after biogenesis but robustly expressed by 4–8 h after biogenesis (Fig. S3A), while Rab11DN–YFP was undetectable at 0–4 h after biogenesis and barely detectable at 4–8 h after biogenesis (Fig. S3B). When examining the effect of Rab1DN and Rab11DN overexpression on secretory granule size, we found that salivary gland-specific overexpression of both of these proteins resulted in a substantial decrease in secretory granule size at the 20–24 h timepoint (Fig. 3E). However, the phenotype appeared slightly weaker and more variable in Rab11DN-expressing glands, likely due to delayed expression of this transgenic construct. Overall, this data validates our RNAi screen results and indicates that GTP binding is required for Rab1 and Rab11 function during mucin granule maturation.

Fig. 3.

Dominant-negative Rab1 and Rab11 do not localize to secretory granule membranes. (A) Live-cell imaging of Rab1–EYFP (cyan) and mucin (red) localization at 8–12 h after biogenesis. Rab1 is present around granule membranes at this timepoint. Image shown is a single slice from a z-stack comprising three slices at a step size of 0.30 µm. (B) Live-cell imaging of Rab1DN–YFP (cyan) and mucin (red) localization at 8–12 h after biogenesis. Rab1DN is not enriched around granule membranes at this timepoint. Image shown is a single slice from a z-stack comprising 12 slices at a 0.31 µm step size. (C) Live-cell imaging of Rab11–EYFP (cyan) and mucin (red) localization at 8–12 h after biogenesis. Rab11 is present around granule membranes at this timepoint. Image shown is a single slice from a z-stack comprising ten slices at a step size of 0.31 µm. (D) Live-cell imaging of Rab11DN–YFP (cyan) and mucin (red) localization at 8–12 h after biogenesis. Rab11DN is not enriched around granule membranes at this timepoint. Image shown is a single slice from a z-stack comprising ten slices at a 0.31 µm step size. (E) Live-cell imaging of mucin granules (red) in control and Rab1DN- and Rab11DN-expressing glands at 20–24 h after biogenesis. Mucin granules are reduced in size in Rab1DN- and Rab11DN-expressing glands. Full genotypes: control, Sgs3-GFP/+; Sgs3>/+; Rab1DN, Sgs-GFP/UAS-Rab1DN-YFP; Sgs3>/+; Rab11DN, Sgs3-GFP/UAS-Rab11DN-YFP; Sgs3>/+. Images shown are representative of three experimental replicates with n≥10 salivary glands from independent animals analyzed per genotype. Scale bars: 5 µm.

Rab11 is required for Rab1 localization to secretory granule membranes

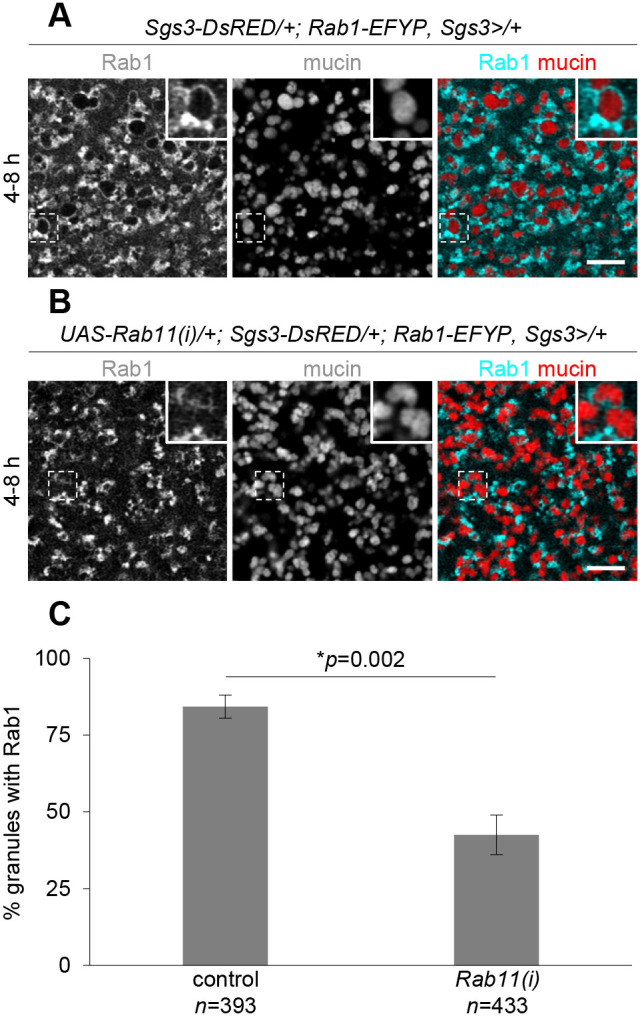

Many Rabs function sequentially to regulate membrane trafficking; for example, Rab5 and its effectors are required for Rab7 recruitment to endosomal membranes, regulating the transition from an early endosome to a late endosome (Wandinger-Ness and Zerial, 2014). To test whether Rab1 and Rab11 function in this manner on secretory granule membranes, we tested whether RNAi knockdown of one of these Rabs affected localization of the other. Since Rab11 was present on the membranes of nascent secretory granules (0–4 h timepoint) while Rab1 was not, we first tested whether Rab11 knockdown affected localization of Rab1 protein. Strikingly, we observed a significant reduction in the percentage of granules with Rab1 on their membrane at 4–8 h after biogenesis upon knockdown of Rab11 (Fig. 4). Additionally, in cases where secretory granules did have Rab1 present, the amount of Rab1 was dramatically reduced upon loss of Rab11 (Fig. 4A,B). Similar results were seen with a second, independent Rab11-RNAi line (Fig. S4A). qPCR analysis of dissected salivary glands showed that Rab11-RNAi did not significantly alter Rab1 mRNA expression levels (Fig. S1A), suggesting that loss of Rab11 specifically affects Rab1 localization, not expression. In contrast, RNAi knockdown of Rab1 did not alter Rab11 expression levels or localization patterns (Figs S1A, S4B–D). Taken together, these results suggest that Rab11 is required for Rab1 recruitment to the membrane of immature secretory granules.

Fig. 4.

Rab11 is required for Rab1 localization to mucin granule membranes. (A) Live-cell imaging of Rab1–EFYP (cyan) and mucin (red) localization at 4–8 h after biogenesis. Rab1 is enriched around granule membranes at this timepoint. Image shown is a single slice from a z-stack comprising six slices at a 0.31 µm step size. The boxed area is magnified in the upper right corner of each image. (B) Live-cell imaging of Rab1–EYFP (cyan) and mucin (red) localization upon salivary gland-specific expression of Rab11-RNAi at 4–8 h after biogenesis. Rab1 localization to mucin granule membranes is significantly impaired. Image shown is a single slice from a z-stack comprising six slices at a 0.31 µm step size. The boxed area is magnified in the upper right corner of each image. Images shown are representative of three experimental replicates with n≥10 salivary glands from independent animals analyzed per genotype. Scale bars: 5 µm. (C) Quantification of the percentage of granules surrounded by Rab1 showing that there is a significant reduction in Rab11-RNAi-expressing glands compared to controls at 4–8 h after biogenesis. Genotypes in C are the same as shown in A and B. Graph shows mean±s.d. from cropped images of three cells from three separate salivary glands isolated from independent animals. Statistics calculated with an unpaired, two-tailed t-test.

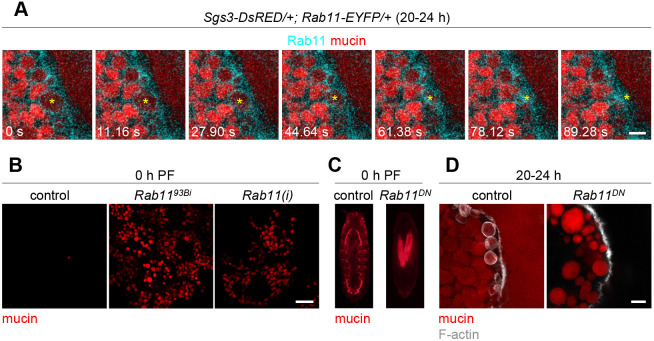

Rab11 function is required for exocytosis

Interestingly, in control cells, we observed that Rab11 protein continued to associate with the membrane of secretory granules during the process of exocytosis (Movie 1; Fig. 5A), suggesting that Rab11 may play a functional role in exocytosis. To begin to test this hypothesis, we first looked for retention of mucin granules at the onset of metamorphosis [puparium formation (PF)] in salivary glands defective for Rab11 function. Some animals homozygous for the hypomorphic Rab1193Bi mutation (Eisenberg et al., 1990; Giansanti et al., 2007; Jankovics et al., 2001) survive to enter metamorphosis, making it possible to test for exocytosis defects in this mutant background. All mucin proteins had been secreted by the onset of metamorphosis in the salivary glands of control animals; however, Rab1193Bi mutant salivary glands still contained a significant amount of unsecreted mucin granules (Fig. 5B), indicating that there were exocytosis defects upon loss of Rab11 function. Notably, the unsecreted granules were quite small, further confirming a functional role for Rab11 in regulating secretory granule size. Similar phenotypes were observed in salivary glands expressing Rab11-RNAi (Fig. 5B). To further confirm these results, we examined the localization of mucins in whole animals at the onset of metamorphosis. Mucins are expelled out of the salivary gland lumen and onto the surface of control animals at puparium formation (Biyasheva et al., 2001; Kang et al., 2017), forming a visible fluorescent ‘halo’ around the prepupa (Fig. 5C). In contrast, mucins were present only within the salivary glands and not on the surface of animals upon salivary gland-specific overexpression of Rab11DN (Fig. 5C), confirming that exocytosis fails upon loss of Rab11 function.

Fig. 5.

Rab11 function is required for exocytosis. (A) Live-cell time-lapse imaging of Rab11–EYFP (cyan) and mucin (red) localization during granule exocytosis showing that Rab11 stays associated with granule membranes during exocytosis. Yellow asterisk denotes a granule undergoing exocytosis over the course of the time-lapse. Images shown are stills from Movie 1 and represent a maximum intensity projection of nine optical slices acquired at a 0.31 µm step size; these images were not deconvolved. The salivary gland lumen is on the right side of the images. Note that this time-lapse shows only the final steps of secretory granule fusion with the plasma membrane. (B) Live-cell imaging of mucins (red) in control (Sgs3-GFP/+), Rab1193Bi mutant (Sgs3-GFP/+; Rab1193Bi/Rab1193Bi), and Rab11-RNAi [Rab11(i); UAS-Rab11-RNAi/+; Sgs3-GFP/+; Sgs3>/+] salivary glands shows that Rab11 mutant and RNAi glands have secretion defects at the onset of metamorphosis (puparium formation, PF). Rab1193Bi image shows a single slice from a z-stack comprising 31 optical slices at a 0.36 µm step size. (C) Imaging of whole puparia at the onset of metamorphosis (0 h PF) showing that mucins (red) have been expelled out of the glands and onto the surface of the animal in controls (Sgs3-DsRED/+; Sgs3>/+) but remain trapped in the glands upon expression of Rab11DN (Sgs3-DsRED/+; Sgs3>/UAS-Rab11DN-YFP). (D) Phalloidin staining (gray) to detect F-actin in fixed cells shows that F-actin wraps around mucin granules (red) undergoing exocytosis in control but not Rab11DN-expressing salivary glands at 20–24 h after biogenesis. Genotypes are as shown in C. Control image shows a single slice from a z-stack comprising eight optical slices at a 0.20 µm step size. Rab11DN image shows a single slice from a z-stack comprising 21 slices at a 0.36 µm step size. The salivary gland lumen is on the right side of the images. Note that the variability in secretory granule size observed in Rab11DN-expressing glands likely results from a delay in expression of that transgene (see Fig. S3 for details). Images shown are representative of three experimental replicates with n≥10 salivary glands/puparia analyzed per genotype. Scale bars: 5 µm (A,D); 20 µm (B).

We next wanted to understand why loss of Rab11 function inhibits secretory granule maturation and exocytosis. Previous work by us and others has demonstrated that defects in secretory granule membrane fusion protein trafficking result in both maturation and exocytosis defects (Burgess et al., 2012; Ma et al., 2020; Neuman and Bashirullah, 2018), prompting us to test whether these membrane fusion proteins were present on secretory granule membranes upon loss of Rab11. The SNARE protein SNAP-24 was present on the membranes of secretory granules in control glands (Fig. S5A), consistent with previously reported results (Neuman and Bashirullah, 2018; Niemeyer and Schwarz, 2000). SNAP-24 was also present on the membranes of small secretory granules in salivary glands with RNAi knockdown of Rab11 (Fig. S5C), indicating that a defect in membrane fusion protein trafficking is not responsible for the maturation or exocytosis defects observed upon loss of Rab11.

As a next step to understanding why exocytosis fails upon loss of Rab11, we took a more mechanistic approach and examined the machinery required for physical fusion of secretory granule membranes with the apical plasma membrane. Previous work has demonstrated that the actomyosin cytoskeleton is required for exocytosis of these large mucin-containing secretory granules, and assembly of filamentous actin (F-actin) is the first observable event during this process (Rousso et al., 2015; Tran et al., 2015). As expected, we observed filamentous actin (F-actin), as assessed by phalloidin staining, wrapped around granules undergoing exocytosis in control salivary glands, and the presence of mucin proteins in the lumen indicated that other secretory granules had already undergone exocytosis (Fig. 5D). In contrast, no mucin protein was visible in the lumen of salivary glands overexpressing Rab11DN at the 20–24 h timepoint, and no secretory granules near the apical membrane were wrapped in F-actin (Fig. 5D), indicating that this process fails without functional Rab11 present on mucin granule membranes. Taken together, these results suggest that Rab11 may play a functional role in promoting F-actin-dependent fusion of mucin-containing secretory granules during exocytosis.

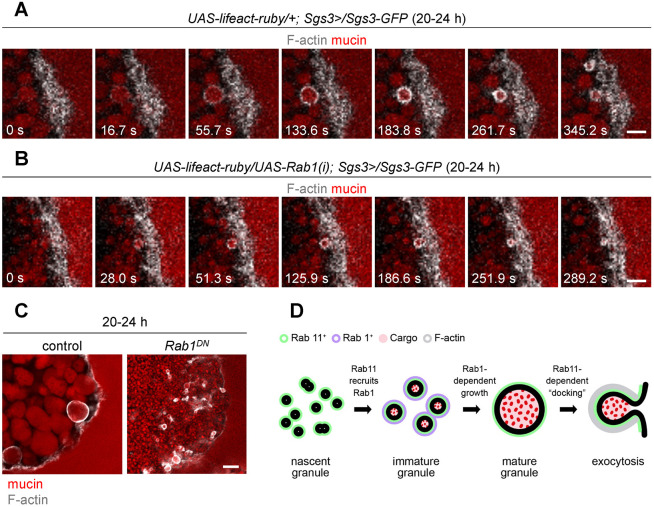

Small granules lacking Rab1 are secreted

Our next goal was to determine whether loss of Rab1 affected exocytosis. Like Rab11, we first looked for retention of mucin granules upon loss of Rab1. Interestingly, we found that no mucin granules were retained at the onset of metamorphosis in salivary glands expressing Rab1-RNAi, and just prior to the onset of metamorphosis, the lumen was fully expanded and filled with secreted mucins (Fig. S6), indicating that exocytosis proceeded normally upon loss of Rab1. Additionally, Rab1 knockdown did not appear to perturb trafficking of SNAP-24, since this SNARE protein was still present on the membranes of small secretory granules (Fig. S5A,B). We also examined F-actin dynamics during exocytosis. Surprisingly, unlike what was seen with Rab11DN, salivary glands expressing Rab1DN had tiny secretory granules near the apical membrane wrapped in F-actin at the 20-24 h timepoint and visible mucin proteins in the lumen (Fig. 6C). To confirm these results, we performed live-cell time-lapse imaging of mucin granules and F-actin dynamics using the fluorescently tagged F-actin binding peptide Lifeact–ruby (Riedl et al., 2008). Consistent with previous reports (Rousso et al., 2015; Tran et al., 2015), we observed F-actin assemble around mucin granules as they were undergoing exocytosis in control cells (Movie 2; Fig. 6A). Similarly, F-actin assembled around small granules in salivary glands expressing Rab1-RNAi, and these small granules were secreted (Movie 3; Fig. 6B). This data shows that immature granules lacking Rab1 can be secreted and suggests that an increase in mucin granule size is not required for exocytosis.

Fig. 6.

Small granules lacking Rab1 undergo exocytosis. (A) Live-cell time-lapse imaging of the actin-binding peptide Lifeact–ruby to detect F-actin (gray) and mucins (red) in control cells during the process of exocytosis shows that F-actin forms around granules undergoing exocytosis. Images shown are stills from Movie 2 and represent single slices from a z-stack comprising 16 slices at a 0.75 µm step size. The salivary gland lumen is on the right side of the images. (B) Live-cell time-lapse imaging of F-actin (gray) and mucins (red) shows that small granules in Rab1-RNAi-expressing cells undergo exocytosis. Images shown are stills from Movie 3 and represent single slices from a z-stack comprising 13 slices at 1.0 µm step size. The salivary gland lumen is on the right side of the images. The time-lapses in A and B show events that occur immediately prior to and during exocytosis. (C) Phalloidin staining to detect F-actin (gray) in fixed cells shows that F-actin wraps around normal size granules undergoing exocytosis in controls (Sgs3-DsRED/+; Sgs3>/+) and small granules undergoing exocytosis in Rab1DN-expressing (Sgs3-DsRED/UAS-Rab1DN-YFP; Sgs3>/+) glands at 20–24 h after biogenesis. Control image shows a single slice from a z-stack comprising 19 optical slices at a 0.36 µm step size; Rab1DN image shows a single slice from a z-stack comprising 15 optical slices at a 0.20 µm step size. The salivary gland lumen is on the right side of the images. Images shown are representative of three experimental replicates with n≥10 salivary glands from independent animals analyzed per genotype. Scale bars: 5 µm. (D) Summary model. Mucin-containing secretory granules undergo two distinct ‘phases’ of growth; the first involves a rapid, Rab1-independent fusion of nascent granules to generate an ∼18-fold increase in volume in just 4 h. The second phase of growth begins at 4 h after biogenesis and involves a more gradual Rab1-dependent ∼15-fold increase in granule volume over the following 16 h. Rab11 is present on nascent granule membranes and recruits Rab1 to immature granule membranes. Rab1 is removed from mature granules, while Rab11 remains on granule membranes and regulates secretory granule ‘docking’ to the plasma membrane and/or F-actin recruitment during exocytosis.

DISCUSSION

Secretory granule maturation is a poorly understood process during regulated exocytosis. Here, we have identified a new role for Rab proteins in the regulation of secretory granule size during maturation. Rab11 is present on nascent secretory granule membranes and is required for recruitment of Rab1; Rab1, in turn, drives growth of immature secretory granules, and Rab1 removal may signal the completion of maturation. Rab11 appears to have a second functional role in initiating secretory granule fusion with the plasma membrane during regulated exocytosis (Fig. 6D). Overall, these findings provide unexpected new insights into the function of Rab proteins during secretory granule maturation and regulated exocytosis.

The Drosophila larval salivary glands provide unique advantages as a model system for analysis of secretory granule maturation and regulated exocytosis. First, the glands complete a single round of mucin granule biogenesis, maturation, and secretion that unfolds sequentially over a 24 h period. This stands in stark contrast to many other systems, where granule biogenesis, maturation and secretion occur simultaneously. Secondly, the larval salivary glands allow us to perform genetic manipulations that are both tissue- and stage-specific by expressing GAL4 under control of the same promoter as the Salivary gland secretion 3 (Sgs3) mucin (Sgs3-GAL4). Using this driver, we knocked down Rab protein expression without interfering with the function of these critical GTPases during development of the glands and thus could observe specific effects on mucin granule maturation. Other recent studies examined the role of Rab proteins in mucin granule maturation using a different GAL4 driver (AB1-GAL4) (Ma and Brill, 2021; Ma et al., 2020), which is constitutively active in the larval salivary glands from embryogenesis and also appears to be expressed in the central nervous system (FlyBase). Use of this driver confounds interpretation of mucin granule phenotypes, since any phenotypes observed result from cumulative effects after multiple days of RNAi knockdown in developing animals. In contrast, our studies examine mucin granule phenotypes just hours after initiation of RNAi knockdown in salivary glands; therefore, in spite of the inability to examine effects on the earliest stage of granule growth, the stage- and tissue-specificity conferred by the Sgs3-GAL4 driver provides an optimal system to examine gene function during secretory granule maturation.

Our results demonstrate that Rab1 plays a critical functional role in promoting growth of immature granules during maturation. However, how Rab1 facilitates fusion of immature granules remains an unanswered question. Secretory granule membrane protein trafficking appears to be unaffected upon loss of Rab1; therefore, other as-yet-unidentified factors must function downstream of Rab1 to regulate granule–granule fusion. Rab proteins function through direct interaction with effector proteins; therefore, one or more Rab1 effectors likely play a role in secretory granule growth. However, most of the known Rab1 effectors localize to the ER, ERES and/or Golgi to regulate ER exit (Homma et al., 2021), raising the possibility that Rab1 may work with a distinct subset of effectors that are specific to secretory granules. What regulates removal of Rab1 from mature granules also remains an open question. It is possible that removal of Rab1 may be triggered by a granule-autonomous process that ‘senses’ when the granule has reached its final mature size; alternatively, removal of Rab1 could be triggered by an independent developmental signal. Rab GAPs are frequently involved in removal of Rabs from their target membrane (Müller and Goody, 2018); therefore, a change in the localization or developmental expression levels of Rab1 GAPs may facilitate Rab1 removal.

Rab11 appears to have two roles during mucin exocytosis, first in recruiting Rab1 to immature granule membranes, and second in promoting mucin granule fusion with the plasma membrane during secretion. However, we cannot eliminate a possible earlier function for Rab11 in regulating fusion of nascent granules due to technical limitations. The Sgs3-GAL4 driver does not drive robust expression of double-stranded (ds)RNA hairpins early enough to interfere with a function during the first growth phase of nascent granules, and the Rab1193Bi allele is quite weak, with a significant fraction of the animals surviving to adulthood (Jankovics et al., 2001). In contrast, the requirement for Rab11 function during exocytosis, like the role of Rab11 in recruiting Rab1 to immature granules, is much more conclusive. A functional role for Rab11B in insulin granule exocytosis from murine MIN6 cells has previously been described (Sugawara et al., 2009), and Rab11 also plays a role in exosome biogenesis in Drosophila secondary cells (Fan et al., 2020), providing evidence that Rab11 function is essential for secretion in multiple systems. However, we do not yet know how Rab11 promotes exocytosis in the larval salivary glands. During mucin exocytosis, the granules fuse with the apical membrane, forming a ‘neck-like’ fusion pore; this is followed by the recruitment of F-actin and non-muscle myosin, which generate a contractile force to drive cargo release (Rousso et al., 2015; Tran et al., 2015). Rab11 could be required for either of these steps or for an earlier membrane attachment or tethering step. Sec15, a component of the exocyst complex that plays a role in tethering of vesicles to the plasma membrane, has been reported to be an effector of Rab11 (Wu et al., 2005; Zhang et al., 2004), suggesting that Rab11 function may be required for plasma membrane tethering of mucin-containing vesicles in the larval salivary glands. Given the high penetrance and severity of the secretion defects observed upon loss of Rab11 function, we posit that Rab11 function is likely required for an early membrane attachment or fusion pore formation step during mucin exocytosis. Future studies will be required to test this model.

Secretory granule maturation, including the process of granule fusion, is essential for regulated exocytosis in some cell types, as immature granules are not responsive to stimulation with secretagogues (Bonnemaison et al., 2013). However, our data indicate that small granules lacking Rab1 can still undergo regulated exocytosis, suggesting that at least some aspects of secretory granule maturation may be dispensable. Alternatively, this finding raises the possibility that Rab1 may serve as a ‘marker’ for immature granules, and the presence of Rab1 on secretory granule membranes may prevent those granules from undergoing exocytosis. Our unpublished observations suggest that the mucins secreted from these small granules are abnormal, since a substantial amount of the secreted mucins are retained in the lumen and not expelled onto the surface of the animal. A number of other processes are known to occur during secretory granule maturation, including refinement of secretory granule membrane and cargo content (Bonnemaison et al., 2013; Kögel and Gerdes, 2010b), suggesting that Rab1 function may be required for other processes during secretory granule maturation beyond granule growth and that the presence of Rab1 on granules may inhibit the precocious release of immature granules.

One of the unique features of mucin granules in the larval salivary glands is their large size; mature granules reach an average volume of 30 µm3. This large size presents significant mechanical challenges for membrane fusion events, suggesting that these granules may require additional factors to generate sufficient contractile forces to drive granule–granule fusion during maturation and granule–plasma membrane fusion during exocytosis. However, large secretory granules are not unique to the Drosophila larval salivary glands; several mammalian cell types also produce and secrete large vesicles, including digestive enzymes in the exocrine pancreas (Geron et al., 2013), surfactants in the lungs (Miklavc et al., 2015), and von Willebrand factor in endothelial cells (Nightingale et al., 2011). Future analysis of the localization and function of Rab1 and Rab11 in these systems may reveal a shared requirement for these proteins in secretory vesicle trafficking.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly stocks and husbandry

The following fly stocks were obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center: all UAS-Rab-RNAi lines (stock identifiers listed in Table S1), w1118, Sgs3-GFP, Rab1-EFYP, Rab3-EFYP, Rab5-EYFP, Rab10-EFYP, Rab11-EYFP, Rab27-EFYP, UAS-Rab1DN-YFP, UAS-Rab11DN-YFP, Sgs3-GAL4, UAS-lifeact-ruby, Rab1193Bi, UAS-Sec31-RFP, UAS-Golgi-RFP. Sgs3-DsRED was provided by Andrew Andres (University of Nevada, Las Vegas, NV, USA). We have used the ‘>’ symbol in genotypes as shorthand for ‘GAL4’. All experimental crosses were grown in uncrowded vials or bottles on standard cornmeal-molasses media in an incubator set to 25°C.

Developmental staging

Animals were synchronized at the onset of mucin/glue biogenesis as previously described (Neuman et al., 2021). Given that there is some degree of variability in developmental rates between animals, a second layer of tissue-autonomous synchronization was used to further confirm developmental stages. Since glue protein synthesis begins in the cells at the distal tip of the glands and progresses forward (Biyasheva et al., 2001), the number of cells that synthesized glue was used to confirm developmental timing according to the following criteria: 0–4 h after biogenesis, glue protein visible only in the cells at the distal tip of the glands; 4–8 h after biogenesis, glue protein visible in the distal one-third to one-half of the gland; 8–12 h after biogenesis, glue protein visible in the distal one-half to two-thirds of the gland; 12–16 h after biogenesis, glue protein visible in all the large acinar cells of the gland; 16–20 h after biogenesis, glue protein visible in all cells of the gland, including smaller acinar cells located near the salivary gland duct; 20–24 h after biogenesis, onset of secretion with glue protein visible in the lumen. Only cells near the distal tip of the gland were imaged to ensure consistency across developmental stages and genotypes.

Quantitative real-time PCR

qPCR was performed as previously described (Ihry et al., 2012). Total RNA was isolated from dissected salivary glands of the appropriate developmental stage and genotype using the RNeasy Plus Mini Kit (Qiagen). 400 ng of total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA with the SuperScript III First-Strand Synthesis System (Invitrogen). Samples were collected and analyzed in biological triplicates. qPCR was performed on a Roche LightCycler 480 with LightCycler 480 SYBR Green I Master Mix (Roche). The Relative Expression Software Tool (REST; Pfaffl et al., 2002) was used to calculate relative expression and p-values; REST calculates standard error using a confidence interval centered on the median and calculates P-values for relative expression ratios using integrated randomization and bootstrapping methods (Pfaffl et al., 2002). Expression was normalized to the reference gene rp49; primers for rp49 were previously published (Ihry et al., 2012). New primers for Rab1 and Rab11 were designed using FlyPrimerBank (Hu et al., 2013): Rab1 F, 5′-CGACGGAAAGACCATTAAACTGC-3′; Rab1 R, 5′-GCGCCCCTATAATATGAAGACG-3′; Rab11 F, 5′-ATTTGCTCTCACGTTTCACGC-3′; Rab11 R, 5′-GCCATCGACCTCTATGCTGC-3′.

Confocal microscopy and immunofluorescence

All images except those in Figs 5C, 6C, and Fig. S5 were obtained from live, unfixed tissue. For live tissue imaging, salivary glands of the appropriate developmental stage and genotype were dissected in PBS and mounted in 1% low-melt agarose (Apex Chemicals) made in PBS. Tissues were imaged for no more than 15 min after mounting, and imaging was carried out at room temperature. At least 10 salivary glands were imaged per experiment. Images were acquired using an Olympus FV3000 laser scanning confocal microscope (40× silicon oil immersion objective, NA 1.25; 60× oil immersion objective, NA 1.42; 100× oil immersion objective, NA 1.49) with FV31S-SW software. Brightness and contrast were adjusted post acquisition with FV31S-SW software. Spectral unmixing was conducted using the blind unmixing algorithm in FV31S-SW software. Images acquired as z-stacks (as indicated in figure legends) were deconvolved using three iterations of the Olympus CellSens Deconvolution for Laser Scanning Confocal Advanced Maximum Likelihood algorithm. Movies were acquired using the Olympus FV3000 resonant scan head. For fixed tissue imaging, immunofluorescence staining for SNAP-24 was carried out as previously described (Neuman and Bashirullah, 2018; Yin et al., 2007). Salivary glands of the appropriate stage and genotype were dissected in PBS, fixed for 30 min at room temperature in PBS with 0.1% Triton-X 100 (PBST) and 4% formaldehyde, and blocked overnight at 4°C in PBST with 4% BSA. The SNAP-24 antibody (gift from Thomas Schwarz, Harvard Medical School) (Niemeyer and Schwarz, 2000) was diluted at 1:200 in PBST with 4% BSA and tissues were stained overnight at 4°C. Anti-rabbit-IgG conjugated to Cy3 (Jackson Immuno-Research Labs 711-165-152) secondary antibody was diluted at 1:200 in PBST with 4% BSA. For phalloidin staining, salivary glands of the appropriate stage and genotype were fixed and blocked as described above. Tissues were incubated in 1:250 Oregon Green 488 conjugated to phalloidin (Invitrogen O7466) for 30 min at room temperature. Stained tissues were mounted in Vectashield (Vector Laboratories) and imaged as described above. For quantification of granule volume, we used data from confocal z-stacks to identify the largest cross-sectional area of each granule; only granules that were fully imaged in the z-direction were used for analysis. We then used ImageJ to measure the cross-sectional diameter of each granule (using an embedded scale bar to convert pixels to µm in ImageJ). The cross-sectional diameter value was then recorded in Excel, where volume calculations were performed. Granules were assumed to be spherical. Box-and-whisker plot was generated using Prism. Analysis of Rab1 and Rab11 localization to granule membranes was conducted by all authors of the manuscript, and we used look-up tables (LUTs) to temporarily over-contrast images to remove background cytoplasmic signal. If ‘halos’ were still visible around mucin cargo with background removed, the Rab protein was classified as being enriched on granule membranes at a particular timepoint. Quantification of the percentage of granules with Rab1–EFYP or Rab11–EYFP was undertaken using FV31S-SW software. Images of whole puparia were obtained using an Olympus SXZ16 stereomicroscope coupled to an Olympus DP72 digital camera with DP2-BSW software.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Stocks obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (NIH P40OD018537) were used in this study. The authors thank Lora Luo for assistance with illustration.

Footnotes

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing or financial interests.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: S.D.N., A.B.; Methodology: S.D.N., A.B.; Validation: S.D.N., A.B.; Investigation: S.D.N., A.R.L., J.E.S., A.T.C.; Data curation: S.D.N., A.R.L.; Writing - original draft: S.D.N.; Writing - review & editing: S.D.N., A.B.; Visualization: S.D.N., A.B.; Supervision: A.B.; Project administration: A.B.; Funding acquisition: A.B.

Funding

This work was supported in part by the National Institutes of Health (GM123204 to A.B.). Deposited in PMC for release after 12 months.

References

- Ahras, M., Otto, G. P. and Tooze, S. A. (2006). Synaptotagmin IV is necessary for the maturation of secretory granules in PC12 cells. J. Cell Biol. 173, 241-251. 10.1083/jcb.200506163 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barr, F. and Lambright, D. G. (2010). Rab GEFs and GAPs. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 461-470. 10.1016/j.ceb.2010.04.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beckendorf, S. K. and Kafatos, F. C. (1976). Differentiation in the salivary glands of Drosophila melanogaster: Characterizaion of the glue proteins and their developmental appearance. Cell 9, 365-373. 10.1016/0092-8674(76)90081-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Biyasheva, A., Do, T.-V., Lu, Y., Vaskova, M. and Andres, A. J. (2001). Glue secretion in the Drosophila salivary gland: a model for steroid-regulated exocytosis. Dev. Biol. 231, 234-251. 10.1006/dbio.2000.0126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blümer, J., Rey, J., Dehmelt, L., Maze, T., Wu, Y.-W., Bastiaens, P., Goody, R. S. and Itzen, A. (2013). RabGEFs are a major determinant for specific Rab membrane targeting. J. Cell Biol. 200, 287-300. 10.1083/jcb.201209113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonnemaison, M. L., Eipper, B. A. and Mains, R. E. (2013). Role of adaptor proteins in secretory granule biogenesis and maturation. Front. Endocrinol. (Lausanne) 4, 1-17. 10.3389/fendo.2013.00101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess, J., Del Bel, L. M., Ma, C.-I. J., Barylko, B., Polevoy, G., Rollins, J., Albanesi, J. P., Krämer, H. and Brill, J. A. (2012). Type II phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase regulates trafficking of secretory granule proteins in Drosophila. J. Cell Sci. 125, 3040-3050. 10.1242/jcs.117010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calhoun, B. C. and Goldenring, J. R. (1996). Rab proteins in gastric parietal cells: evidence for the membrane recycling hypothesis. Yale J. Biol. Med. 69, 1-8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan, C. C., Scoggin, S., Wang, D., Cherry, S., Dembo, T., Greenberg, B., Jin, E. J., Kuey, C., Lopez, A., Mehta, S. Q.et al. (2011). Systematic discovery of Rab GTPases with synaptic functions in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 21, 1704-1715. 10.1016/j.cub.2011.08.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cherbas, L., Hu, X., Zhimulev, I., Belyaeva, E. and Cherbas, P. (2003). EcR isoforms in Drosophila: testing tissue-specific requirements by targeted blockade and rescue. Development 130, 271-284. 10.1242/dev.00205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costantino, B. F. B., Bricker, D. K., Alexandre, K., Shen, K., Merriam, J. R., Antoniewski, C., Callender, J. L., Henrich, V. C., Presente, A. and Andres, A. J. (2008). A novel ecdysone receptor mediates steroid-regulated developmental events during the mid-third instar of Drosophila. PLoS Genet. 4, e1000102. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du, W., Zhou, M., Zhao, W., Cheng, D., Wang, L., Lu, J., Song, E., Feng, W., Xue, Y., Xu, P.et al. (2016). HID-1 is required for homotypic fusion of immature secretory granules during maturation. Elife 5, e18134. 10.7554/eLife.18134.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dunst, S., Kazimiers, T., von Zadow, F., Jambor, H., Sagner, A., Brankatschk, B., Mahmoud, A., Spannl, S., Tomancak, P., Eaton, S.et al. (2015). Endogenously tagged Rab proteins: a resource to study membrane trafficking in Drosophila. Dev. Cell 33, 351-365. 10.1016/j.devcel.2015.03.022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg, M., Gathy, K., Vincent, T. and Rawls, J. (1990). Molecular cloning of the UMP synthase gene rudimentary-like from Drosophila melanogaster. MGG Mol. Gen. Genet. 222, 1-8. 10.1007/BF00283015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan, S., Kroeger, B., Marie, P. P., Bridges, E. M., Mason, J. D., McCormick, K., Zois, C. E., Sheldon, H., Khalid Alham, N., Johnson, E.et al. (2020). Glutamine deprivation alters the origin and function of cancer cell exosomes. EMBO J. 39, e103009. 10.15252/embj.2019103009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkaš, R. and Šut'áková, G. (1998). Ultrastructural changes of Drosophila larval and prepupal salivary glands cultured in vitro with ecdysone. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol. Anim. 34, 813-823. 10.1007/s11626-998-0036-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farquhar, M. G., Reid, J. A. J. and Daniell, L. W. (1978). Intracellular transport and packaging of prolactin: a quantitative electron microscope autoradiographic study of mammotrophs dissociated from rat pituitaries. Endocrinology 102, 296-311. 10.1210/endo-102-1-296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Förster, D., Armbruster, K. and Luschnig, S. (2010). Sec24-dependent secretion drives cell-autonomous expansion of tracheal tubes in Drosophila. Curr. Biol. 20, 62-68. 10.1016/j.cub.2009.11.062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garrett, M. D., Kabcenell, A. K., Zahner, J. E., Kaibuchi, K., Sasaki, T., Takai, Y., Cheney, C. M. and Novick, P. J. (1993). Interaction of Sec4 with GDI proteins from bovine brain, Drosophila melanogaster and Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Conservation of GDI membrane dissociation activity. FEBS Lett. 331, 233-238. 10.1016/0014-5793(93)80343-S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaudet, P., Livstone, M. S., Lewis, S. E. and Thomas, P. D. (2011). Phylogenetic-based propagation of functional annotations within the Gene Ontology consortium. Brief. Bioinform. 12, 449-462. 10.1093/bib/bbr042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geron, E., Schejter, E. D. and Shilo, B. Z. (2013). Directing exocrine secretory vesicles to the apical membrane by actin cables generated by the formin mDia1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 110, 10652-10657. 10.1073/pnas.1303796110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giansanti, M. G., Belloni, G. and Gatti, M. (2007). Rab11 is required for membrane trafficking and actomyosin ring constriction in meiotic cytokinesis of Drosophila males. Mol. Biol. Cell 18, 5034-5047. 10.1091/mbc.e07-05-0415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammel, I., Lagunoff, D., Bauza, M. and Chi, E. (1983). Periodic, multimodal distribution of granule volumes in mast cells. Cell Tissue Res. 228, 51-59. 10.1007/BF00206264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammel, I., Dvorak, A. M., Peters, S. P., Schulman, E. S., Dvorak, H. F., Lichtenstein, L. M. and Galli, S. J. (1985). Differences in the volume distributions of human lung mast cell granules and lipid bodies: Evidence that the size of these organelles is regulated by distinct mechanisms. J. Cell Biol. 100, 1488-1492. 10.1083/jcb.100.5.1488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hammel, I., Lagunoff, D. and Galli, S. J. (2010). Regulation of secretory granule size by the precise generation and fusion of unit granules. J. Cell. Mol. Med 14, 1904-1916. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2010.01071.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hannah, M. J., Hume, A. N., Arribas, M., Williams, R., Hewlett, L. J., Seabra, M. C. and Cutler, D. F. (2003). Weibel-Palade bodies recruit Rab27 by a content-driven, maturation-dependent mechanism that is independent of cell type. J. Cell Sci. 116, 3939-3948. 10.1242/jcs.00711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homma, Y., Hiragi, S. and Fukuda, M. (2021). Rab family of small GTPases: an updated view on their regulation and functions. FEBS J. 288, 36-55. 10.1111/febs.15453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Y., Sopko, R., Foos, M., Kelley, C., Flockhart, I., Ammeux, N., Wang, X., Perkins, L., Perrimon, N. and Mohr, S. E. (2013). FlyPrimerBank: an online database for Drosophila melanogaster gene expression analysis and knockdown evaluation of RNAi reagents. G3 3, 1607-1616. 10.1534/g3.113.007021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ihry, R. J., Sapiro, A. L., Bashirullah, A., Akagi, K. and Takai, M. (2012). Translational control by the DEAD box RNA helicase belle regulates ecdysone-triggered transcriptional cascades. PLoS Genet. 8, e1003085. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jankovics, F., Sinka, R. and Erdélyi, M. (2001). An interaction type of genetic screen reveals a role of the Rab11 gene in oskar mRNA localization in the developing Drosophila melanogaster oocyte. Genetics 158, 1177-1188. 10.1093/genetics/158.3.1177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang, Y., Neuman, S. D. and Bashirullah, A. (2017). Tango7 regulates cortical activity of caspases during reaper-triggered changes in tissue elasticity. Nat. Commun. 8, 603. 10.1038/s41467-017-00693-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khosravi-Far, R., Lutz, R. J., Cox, A. D., Conroy, L., Bourne, J. R., Sinensky, M., Balch, W. E., Buss, J. E. and Der, C. J. (1991). Isoprenoid modification of rab proteins terminating in CC or CXC motifs. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 6264-6268. 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinsella, B. T. and Maltese, W. A. (1991). rab GTP-binding proteins implicated in vesicular transport are isoprenylated in vitro at cysteines within a novel carboxyl-terminal motif. J. Biol. Chem. 266, 8540-8544. 10.1016/S0021-9258(18)93008-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kögel, T. and Gerdes, H. H. (2010a). Roles of myosin Va and Rab3D in membrane remodeling of immature secretory granules. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 30, 1303-1308. 10.1007/s10571-010-9597-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kögel, T. and Gerdes, H.-H. (2010b). Maturation of secretory granules. Results Probl. Cell Differ. 50, 1-20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kögel, T., Rudolf, R., Hodneland, E., Copier, J., Regazzi, R., Tooze, S. A. and Gerdes, H. H. (2013). Rab3D is critical for secretory granule maturation in PC12 cells. PLoS ONE 8, e57321. 10.1371/journal.pone.0057321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korge, G. (1977). Larval saliva in Drosophila melanogaster: Production, composition, and relationship to chromosome puffs. Dev. Biol. 58, 339-355. 10.1016/0012-1606(77)90096-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leung, K. F., Baron, R. and Seabra, M. C. (2006). Geranylgeranylation of Rab GTPases. J. Lipid Res. 47, 467-475. 10.1194/jlr.R500017-JLR200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lew, S., Hammel, I. and Galli, S. J. (1994). Cytoplasmic granule formation in mouse pancreatic acinar cells. Evidence for formation of immature granules (condensing vacuoles) by aggregation and fusion of progranules of unit size, and for reductions in membrane surface area and immature granule volume during granule maturation. Cell Tissue Res. 278, 327-336. 10.1007/BF00414176 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li, G. and Marlin, M. C. (2015). Rab family of GTPases. Methods Mol. Biol. 1298, 1-15. 10.1007/978-1-4939-2569-8_1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C.-I. J. and Brill, J. A. (2021). Endosomal Rab GTPases regulate secretory granule maturation in Drosophila larval salivary glands. Commun. Integr. Biol. 14, 15-20. 10.1080/19420889.2021.1874663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma, C. I. J., Yang, Y., Kim, T., Chen, C. H., Polevoy, G., Vissa, M., Burgess, J. and Brill, J. A. (2020). An early endosome-derived retrograde trafficking pathway promotes secretory granule maturation. J. Cell Biol. 219, e201808017. 10.1083/jcb.201808017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miklavc, P., Ehinger, K., Sultan, A., Felder, T., Paul, P., Gottschalk, K. E. and Frick, M. (2015). Actin depolymerisation and crosslinking join forces with myosin II to contract actin coats on fused secretory vesicles. J. Cell Sci. 128, 1193-1203. 10.1242/jcs.165571 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller, M. P. and Goody, R. S. (2018). Molecular control of Rab activity by GEFs, GAPs and GDI. Small GTPases 9, 5-21. 10.1080/21541248.2016.1276999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, S. D. and Bashirullah, A. (2018). Hobbit regulates intracellular trafficking to drive insulin-dependent growth during Drosophila development. Development 145, dev161356. 10.1242/dev.161356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuman, S. D., Terry, E. L., Selegue, J. E., Cavanagh, A. T. and Bashirullah, A. (2021). Mistargeting of secretory cargo in retromer-deficient cells. Dis. Model. Mech. 14, dmm046417. 10.1242/dmm.046417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niemeyer, B. A. and Schwarz, T. L. (2000). SNAP-24, a Drosophila SNAP-25 homologue on granule membranes, is a putative mediator of secretion and granule-granule fusion in salivary glands. J. Cell Sci. 113, 4055-4064. 10.1242/jcs.113.22.4055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nightingale, T. D., White, I. J., Doyle, E. L., Turmaine, M., Harrison-Lavoie, K. J., Webb, K. F., Cramer, L. P. and Cutler, D. F. (2011). Actomyosin II contractility expels von Willebrand factor from Weibel-Palade bodies during exocytosis. J. Cell Biol. 194, 613-629. 10.1083/jcb.201011119 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl, M. W., Horgan, G. W. and Dempfle, L. (2002). Relative expression software tool (REST) for group-wise comparison and statistical analysis of relative expression results in real-time PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 30, e36. 10.1093/nar/30.9.e36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, S. R. (2017). Rab GTPases: Master regulators that establish the secretory and endocytic pathways. Mol. Biol. Cell 28, 712-715. 10.1091/mbc.e16-10-0737 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfeffer, S. R., Dirac-Svejstrup, A. B. and Soldati, T. (1995). Rab GDP dissociation inhibitor: Putting Rab GTPases in the right place. J. Biol. Chem. 270, 17057-17059. 10.1074/jbc.270.29.17057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plutner, H., Cox, A. D., Pind, S., Khosravi-Far, R., Bourne, J. R., Schwaninger, R., Der, C. J. and Balch, W. E. (1991). Rab1b regulates vesicular transport between the endoplasmic reticulum and successive Golgi compartments. J. Cell Biol. 115, 31-43. 10.1083/jcb.115.1.31 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, H. M., Zhang, L., Tran, D. T. and Ten Hagen, K. G. (2019). Tango1 coordinates the formation of endoplasmic reticulum/ Golgi docking sites to mediate secretory granule formation. J. Biol. Chem. 294, 19498-19510. 10.1074/jbc.RA119.011063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Riedl, J., Crevenna, A. H., Kessenbrock, K., Yu, J. H., Neukirchen, D., Bista, M., Bradke, F., Jenne, D., Holak, T. A., Werb, Z.et al. (2008). Lifeact: a versatile marker to visualize F-actin. Nat. Methods 5, 605-607. 10.1038/nmeth.1220 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi, G., Jiang, Y., Newman, A. P. and Ferro-Novick, S. (1991). Dependence of Ypt1 and Sec4 membrane attachment on Bet2. Nature 351, 158-161. 10.1038/351158a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rousso, T., Schejter, E. D. and Shilo, B.-Z. (2015). Orchestrated content release from Drosophila glue-protein vesicles by a contractile actomyosin network. Nat. Cell Biol. 18, 181-190. 10.1038/ncb3288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasaki, T., Kikuchi, A., Araki, S., Hata, Y., Isomura, M., Kuroda, S. and Takai, Y. (1990). Purification and characterization from bovine brain cytosol of a protein that inhibits the dissociation of GDP from and the subsequent binding of GTP to smg p25A, a ras p21-like GTP-binding protein. J. Biol. Chem. 265, 2333-2337. 10.1016/S0021-9258(19)39980-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasidharan, N., Sumakovic, M., Hannemann, M., Hegermann, J., Liewal, J. F., Olendrowitz, C., Koenig, S., Grant, B. D., Rizzoli, S. O., Gottschalk, A.et al. (2012). RAB-5 and RAB-10 cooperate to regulate neuropeptide release in Caenorhabditis elegans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 109, 18944-18949. 10.1073/pnas.1203306109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satoh, A. K., O'Tousa, J. E., Ozaki, K. and Ready, D. F. (2005). Rab11 mediates post-Golgi trafficking of rhodopsin to the photosensitive apical membrane of Drosophila photoreceptors. Development 132, 1487-1497. 10.1242/dev.01704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, H. D., Puzicha, M. and Gallwitz, D. (1988). Study of a temperature-sensitive mutant of the ras-related YPT1 gene product in yeast suggests a role in the regulation of intracellular calcium. Cell 53, 635-647. 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90579-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segev, N., Mulholland, J. and Botstein, D. (1988). The yeast GTP-binding YPT1 protein and a mammalian counterpart are associated with the secretion machinery. Cell 52, 915-924. 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90433-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sivars, U., Aivazian, D. and Pfeffer, S. R. (2003). Yip3 catalyses the dissociation of endosomal Rab-GDI complexes. Nature 425, 856-859. 10.1038/nature02057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R. E., Farquhar, M. G., Smith, R. E. and Farquhar, M. G. (1966). Lysosome function in the regulation of the secretory process in cells of the anterior pituitary gland. J. Cell Biol. 31, 319-347. 10.1083/jcb.31.2.319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldati, T., Riederer, M. A. and Pfeffer, S. R. (1993). Rab GDI: a solubilizing and recycling factor for rab9 protein. Mol. Biol. Cell 4, 425-434. 10.1091/mbc.4.4.425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldati, T., Shapiro, A. D., Dirac Svejstrup, A. B. and Pfefffer, S. R. (1994). Membrane targeting of the small GTPase Rab9 is accompanied by nucleotide exchange. Nature 369, 76-78. 10.1038/369076a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sugawara, K., Shibasaki, T., Mizoguchi, A., Saito, T. and Seino, S. (2009). Rab11 and its effector Rip11 participate in regulation of insulin granule exocytosis. Genes Cells 14, 445-456. 10.1111/j.1365-2443.2009.01285.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tran, D. T., Masedunskas, A., Weigert, R. and Ten Hagen, K. G. (2015). Arp2/3-mediated F-actin formation controls regulated exocytosis in vivo. Nat. Commun. 6, 1-10. 10.1038/ncomms10098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich, O., Stenmark, H., Alexandrov, K., Huber, L. A., Kaibuchi, K., Sasaki, T., Takai, Y. and Zerial, M. (1993). Rab GDP dissociation inhibitor as a general regulator for the membrane association of rab proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 268, 18143-18150. 10.1016/S0021-9258(17)46822-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich, O., Horiuchi, H., Bucci, C. and Zerial, M. (1994). Membrane association of Rab5 mediated by GDP-dissociation inhibitor and accompanied by GDP/GTP exchange. Nature 368, 157-160. 10.1038/368157a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich, O., Reinsch, S., Urbé, S., Zerial, M. and Parton, R. G. (1996). Rab11 regulates recycling through the pericentriolar recycling endosome. J. Cell Biol. 135, 913-924. 10.1083/jcb.135.4.913 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbé, S., Huber, L. A., Zerial, M., Tooze, S. A. and Parton, R. G. (1993). Rab11, a small GTPase associated with both constitutive and regulated secretory pathways in PC12 cells. FEBS Lett. 334, 175-182. 10.1016/0014-5793(93)81707-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urbé, S., Page, L. J. and Tooze, S. A. (1998). Homotypic fusion of immature secretory granules during maturation in a cell-free assay. J. Cell Biol. 143, 1831-1844. 10.1083/jcb.143.7.1831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandinger-Ness, A. and Zerial, M. (2014). Rab proteins and the compartmentalization of the endosomal system. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 6, a022616. 10.1101/cshperspect.a022616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weintraub, H., Abramovici, A., Amichai, D., Eldar, T., Ben-Dor, L., Pentchev, P. G. and Hammel, I. (1992). Morphometric studies of pancreatic acinar granule formation in NCTR-Balb/c mice. J. Cell Sci. 102, 141-147. 10.1242/jcs.102.1.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welz, T., Wellbourne-Wood, J. and Kerkhoff, E. (2014). Orchestration of cell surface proteins by Rab11. Trends Cell Biol. 24, 407-415. 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.02.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wendler, F., Page, L., Urbé, S. and Tooze, S. A. (2001). Homotypic fusion of immature secretory granules during maturation requires syntaxin 6. Mol. Biol. Cell 12, 1699-1709. 10.1091/mbc.12.6.1699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu, S., Mehta, S. Q., Pichaud, F., Bellen, H. J. and Quiocho, F. A. (2005). Sec15 interacts with Rab11 via a novel domain and affects Rab11 localization in vivo. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 879-885. 10.1038/nsmb987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yin, V. P., Thummel, C. S. and Bashirullah, A. (2007). Down-regulation of inhibitor of apoptosis levels provides competence for steroid-triggered cell death. J. Cell Biol. 178, 85-92. 10.1083/jcb.200703206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, X.-M., Ellis, S., Sriratana, A., Mitchell, C. A. and Rowe, T. (2004). Sec15 is an effector for the Rab11 GTPase in mammalian cells. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 43027-43034. 10.1074/jbc.M402264200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J., Schulze, K. L., Robin Hiesinger, P., Suyama, K., Wang, S., Fish, M., Acar, M., Hoskins, R. A., Bellen, H. J. and Scott, M. P. (2007). Thirty-one flavors of Drosophila Rab proteins. Genetics 176, 1307-1322. 10.1534/genetics.106.066761 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhen, Y. and Stenmark, H. (2015). Cellular functions of Rab GTPases at a glance. J. Cell Sci. 128, 3171-3176. 10.1242/jcs.166074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.