Abstract

This cohort study uses Medicare Part D data to examine whether there is an association between the implementation of state limits on opioid prescription duration and changes in prescribing.

Between March 2016 and July 2018, 23 states implemented legislation limiting the duration of initial opioid prescriptions to a maximum of 7 days (17 states [74%] limited to 7 days or less, 2 [9%] to 5 days or less, and 4 [17%] to 3 days or less),1 yet the effect of these policies on opioid prescribing remain poorly understood.2 A previous analysis of Massachusetts and Connecticut found inconsistent results between states.3 As 43% of the US population lives in one of these 23 states, it is worthwhile to examine whether legislation limiting opioid prescription duration is associated with changes in prescribing.

Methods

Using Medicare Part D Prescriber Public Use File between January 1, 2013, and December 31, 2018, we performed a controlled before-and-after cohort study using a difference-in-differences model with state-level fixed effects to assess the influence of laws limiting initial opioid prescriptions to a maximum of 7 days across all episodes of care. We excluded states that implemented selective policies (ie, where restrictions on opioid prescribing applied only to a subset of Medicare beneficiaries or to selected medical specialties, or where the state delegated authority to another entity). Our primary outcome was the mean number of days of opioids prescribed per Medicare Part D enrollee per year. States exposed to the policy were coded as a continuous variable between 0 and 1, adjusting for the proportion of the year that the law was in effect and including a 30-day washout period to allow for uptake. Our model adjusted for state-level differences in race, urbanization, median income, tobacco use, alcohol use, serious mental illness, region, and state-level fixed effects using data from the US census and the National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Statistical analysis was conducted with SPSS, version 26 (IBM). Data were analyzed from December 1, 2020, to April 1, 2021.

This cohort study followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline. As an analysis of deidentified, publicly available data, this study was determined to be exempt from informed consent by the institutional review board of Wayne State University.

Results

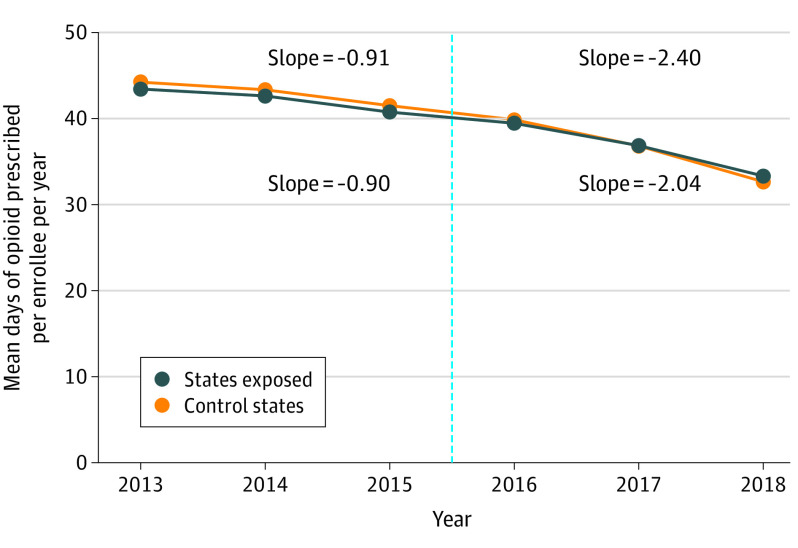

The mean number of days of opioid prescribed per enrollee decreased by a mean (SD) of 11.6 (4.7) days (from 44.2 days in 2013 to 32.7 days in 2018) in states exposed to duration limits compared with a mean (SD) of 10.1 (2.9) days in control states (from 43.4 days in 2013 to 33.3 days in 2018) (Figure). Before the start of duration limits in 2016, days of opioid prescribed were parallel in exposed states and control states. After adjustment in difference-in-differences models, state laws limiting opioid prescriptions to 7 day or less were associated with a reduction in opioid prescribing by 1.7 days per enrollee (95% CI, −0.62 to −2.87 days) (Table). Primary care physicians had the largest decrease in opioid prescribing, but this was not significantly different in exposed states vs control states. State laws limiting duration had a significant reduction in days of opioid prescribed among surgeons and dentists (0.90-day decrease per prescription; 95% CI, −1.37 to −0.42), pain specialists (0.45-day decrease; 95% CI, 0.73 to 0.17), and other specialists (0.29-day decrease; 95% CI, −0.50 to −0.09).

Figure. Mean Days of Opioid Prescribed per Medicare Part D Enrollee Before and After Laws Limiting Duration of Opioids.

Graph shows the timing of implementation of opioid duration limits of 7 days or less across the 23 states that enacted opioid duration limits (states exposed). States exposed included Massachusetts, Connecticut, New York, Maine, Virginia, Rhode Island, Utah, Delaware, New Jersey, Kentucky, Indiana, Hawaii, Alaska, Louisiana, Ohio, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Colorado, South Carolina, West Virginia, Florida, Tennessee, and Michigan. Control states included Alabama, Arkansas, California, Georgia, Iowa, Idaho, Illinois, Kansas, Maryland, Mississippi, Montana, North Dakota, Nebraska, New Mexico, South Dakota, Texas, Wyoming, and Washington, DC. Excluded states included Arizona, Missouri, Minnesota, Nevada, Vermont, Pennsylvania, New Hampshire, Oregon, Washington, and Wisconsin. The vertical line represents the start of the intervention period.

Table. Changes in Opioid Prescribing After Implementation of Laws Restricting Prescribing to 7 Days or Less.

| Days of any opioid prescription | Control states (n = 18) | States exposed to policy (n = 23) | Difference-in-differences estimate (95% CI)a | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2013 | 2018 | Difference | 2013 | 2018 | Difference | ||

| Per enrollee | 43.43 | 33.33 | −10.1 | 44.23 | 32.66 | −11.57 | −1.75 (−2.87 to −0.62) |

| Per enrollee by specialty | |||||||

| Primary care | 25.29 | 16.3 | −8.99 | 24.07 | 14.39 | −9.68 | −0.26 (−1.05 to 0.53) |

| Surgeon or dentist | 9.65 | 9.44 | −0.21 | 11.79 | 11.2 | −0.59 | −0.90 (−1.37 to −0.42) |

| Emergency medicine | 0.73 | 0.34 | −0.39 | 0.51 | 0.22 | −0.29 | 0.06 (−0.02 to 0.13) |

| Pain specialist | 2.68 | 3.23 | 0.55 | 2.98 | 3.51 | 0.53 | −0.45 (−0.73 to −0.17) |

| Other specialistb | 4.11 | 3.49 | −0.62 | 3.98 | 2.85 | −1.13 | −0.29 (−0.50 to −0.09) |

| Trainee/midlevel/institutionc | 0.98 | 0.54 | −0.44 | 0.9 | 0.48 | −0.42 | 0.10 (0.02 to 0.17) |

Estimates are from linear probability models adjusting for race, ethnicity, urbanization, income, tobacco use, alcohol use, serious mental illness, region, year, and state-level fixed effects. The steeper reduction of days of opioid prescription per enrollee in states with laws restricting opioid prescribing was primarily due to relative differences in prescribing among surgeons and dentists, pain specialists, and other specialists.

Other specialists included 23 specialties that did not fit into the other groups.

Trainee/midlevel/institution included trainees, physician assistants, nurse practitioners, and institutions.

Discussion

This cohort study found that in the Medicare population, total days of opioid prescribed per enrollee decreased from 2013 to 2018, with a slightly greater reduction in states with laws restricting initial opioid prescriptions to 7 days or less, suggesting a significant but limited outcome for such legislation. The decline in opioid prescribing occurred in states exposed to the policy and in control states, suggesting either that state laws influenced prescribing behavior across state lines or that this legislation is just one of many interventions that have helped to reduce opioid prescribing.4 The state legislation on opioid prescribing primarily targets initial opioid prescriptions provided for acute pain, and we observed decreases that were most pronounced among surgeons and dentists.

This study is limited to Medicare beneficiaries (individuals aged 65 years or older, with a disability, or with end-stage renal disease); however, excess opioid prescribing is prevalent across all patient poulations.5 The Medicare data also suppresses data for clinicians writing 10 or fewer prescriptions per year, and we were unable to examine differences in initial and subsequent opioid prescriptions.

References

- 1.Davis CS, Lieberman AJ, Hernandez-Delgado H, Suba C. Laws limiting the prescribing or dispensing of opioids for acute pain in the United States: a national systematic legal review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2019;194:166-172. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.09.022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chua KP, Brummett CM, Waljee JF. Opioid prescribing limits for acute pain: potential problems with design and implementation. JAMA. 2019;321(7):643-644. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.0010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Agarwal S, Bryan JD, Hu HM, et al. Association of state opioid duration limits with postoperative opioid prescribing. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2(12):e1918361. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.18361 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers For Disease Control And Prevention Public Health Service US Department Of Health And Human Services . Guideline for prescribing opioids for chronic pain. J Pain Palliat Care Pharmacother. 2016;30(2):138-140. doi: 10.3109/15360288.2016.1173761 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Santosa KB, Hu HM, Brummett CM, et al. New persistent opioid use among older patients following surgery: a Medicare claims analysis. Surgery. 2020;167(4):732-742. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2019.04.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]