This meta-analysis examines the global prevalence of clinically elevated symptoms of depression and anxiety in youth during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Key Points

Question

What is the global prevalence of clinically elevated child and adolescent anxiety and depression symptoms during COVID-19?

Findings

In this meta-analysis of 29 studies including 80 879 youth globally, the pooled prevalence estimates of clinically elevated child and adolescent depression and anxiety were 25.2% and 20.5%, respectively. The prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms during COVID-19 have doubled, compared with prepandemic estimates, and moderator analyses revealed that prevalence rates were higher when collected later in the pandemic, in older adolescents, and in girls.

Meaning

The global estimates of child and adolescent mental illness observed in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic in this study indicate that the prevalence has significantly increased, remains high, and therefore warrants attention for mental health recovery planning.

Abstract

Importance

Emerging research suggests that the global prevalence of child and adolescent mental illness has increased considerably during COVID-19. However, substantial variability in prevalence rates have been reported across the literature.

Objective

To ascertain more precise estimates of the global prevalence of child and adolescent clinically elevated depression and anxiety symptoms during COVID-19; to compare these rates with prepandemic estimates; and to examine whether demographic (eg, age, sex), geographical (ie, global region), or methodological (eg, pandemic data collection time point, informant of mental illness, study quality) factors explained variation in prevalence rates across studies.

Data Sources

Four databases were searched (PsycInfo, Embase, MEDLINE, and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials) from January 1, 2020, to February 16, 2021, and unpublished studies were searched in PsycArXiv on March 8, 2021, for studies reporting on child/adolescent depression and anxiety symptoms. The search strategy combined search terms from 3 themes: (1) mental illness (including depression and anxiety), (2) COVID-19, and (3) children and adolescents (age ≤18 years). For PsycArXiv, the key terms COVID-19, mental health, and child/adolescent were used.

Study Selection

Studies were included if they were published in English, had quantitative data, and reported prevalence of clinically elevated depression or anxiety in youth (age ≤18 years).

Data Extraction and Synthesis

A total of 3094 nonduplicate titles/abstracts were retrieved, and 136 full-text articles were reviewed. Data were analyzed from March 8 to 22, 2021.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Prevalence rates of clinically elevated depression and anxiety symptoms in youth.

Results

Random-effect meta-analyses were conducted. Twenty-nine studies including 80 879 participants met full inclusion criteria. Pooled prevalence estimates of clinically elevated depression and anxiety symptoms were 25.2% (95% CI, 21.2%-29.7%) and 20.5% (95% CI, 17.2%-24.4%), respectively. Moderator analyses revealed that the prevalence of clinically elevated depression and anxiety symptoms were higher in studies collected later in the pandemic and in girls. Depression symptoms were higher in older children.

Conclusions and Relevance

Pooled estimates obtained in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic suggest that 1 in 4 youth globally are experiencing clinically elevated depression symptoms, while 1 in 5 youth are experiencing clinically elevated anxiety symptoms. These pooled estimates, which increased over time, are double of prepandemic estimates. An influx of mental health care utilization is expected, and allocation of resources to address child and adolescent mental health concerns are essential.

Introduction

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, rates of clinically significant generalized anxiety and depressive symptoms in large youth cohorts were approximately 11.6%1 and 12.9%,2 respectively. Since COVID-19 was declared an international public health emergency, youth around the world have experienced dramatic disruptions to their everyday lives.3 Youth are enduring pervasive social isolation and missed milestones, along with school closures, quarantine orders, increased family stress, and decreased peer interactions, all potential precipitants of psychological distress and mental health difficulties in youth.4,5,6,7 Indeed, in both cross-sectional8,9 and longitudinal studies10,11 amassed to date, the prevalence of youth mental illness appears to have increased during the COVID-19 pandemic.3 However, data collected vary considerably. Specifically, ranges from 2.2%12 to 63.8%13 and 1.8%12 to 49.5%13 for clinically elevated depression and anxiety symptoms, respectively. As governments and policy makers deploy and implement recovery plans, ascertaining precise estimates of the burden of mental illness for youth are urgently needed to inform service deployment and resource allocation.

Depression and generalized anxiety are 2 of the most common mental health concerns in youth.14 Depressive symptoms, which include feelings of sadness, loss of interest and pleasure in activities, as well as disruption to regulatory functions such as sleep and appetite,15 could be elevated during the pandemic as a result of social isolation due to school closures and physical distancing requirements.6 Generalized anxiety symptoms in youth manifest as uncontrollable worry, fear, and hyperarousal.15 Uncertainty, disruptions in daily routines, and concerns for the health and well-being of family and loved ones during the COVID-19 pandemic are likely associated with increases in generalized anxiety in youth.16

When heterogeneity is observed across studies, as is the case with youth mental illness during COVID-19, it often points to the need to examine demographic, geographical, and methodological moderators. Moderator analyses can determine for whom and under what circumstances prevalence is higher vs lower. With regard to demographic factors, prevalence rates of mental illness both prior to and during the COVID-19 pandemic are differentially reported across child age and sex, with girls17,18 and older children17,19 being at greater risk for internalizing disorders. Studies have also shown that youth living in regions that experienced greater disease burden2 and urban areas20 had greater mental illness severity. Methodological characteristics of studies also have the potential to influence the estimated prevalence rates. For example, studies of poorer methodological quality may be more likely to overestimate prevalence rates.21 The symptom reporter (ie, child vs parent) may also contribute to variability in the prevalence of mental illness across studies. Indeed, previous research prior to the pandemic has demonstrated that child and parent reports of internalizing symptoms vary,22 with children/adolescents reporting more internalizing symptoms than parents.23 Lastly, it is important to consider the role of data collection timing on potential prevalence rates. While feelings of stress and overwhelm may have been greater in the early months of the pandemic compared with later,24 extended social isolation and school closures may have exerted mental health concerns.

Although a narrative systematic review of 6 studies early in the pandemic was conducted,8 to our knowledge, no meta-analysis of prevalence rates of child and adolescent mental illness during the pandemic has been undertaken. In the current study, we conducted a meta-analysis of the global prevalence of clinically elevated symptoms of depression and anxiety (ie, exceeding a clinical cutoff score on a validated measure or falling in the moderate to severe symptom range of anxiety and depression) in youth during the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. While research has documented a worsening of symptoms for children and youth with a wide range of anxiety disorders,25 including social anxiety,26 clinically elevated symptoms of generalized anxiety are the focus of the current meta-analysis. In addition to deriving pooled prevalence estimates, we examined demographic, geographical, and methodological factors that may explain between-study differences. Given that there have been several precipitants of psychological distress for youth during COVID-19, we hypothesized that pooled prevalence rates would be higher compared with prepandemic estimates. We also hypothesized that child mental illness would be higher among studies with older children, a higher percentage of female individuals, studies conducted later in the pandemic, and that higher-quality studies would have lower prevalence rates.

Methods

Search Strategy and Selection Criteria

This systematic review was registered as a protocol with PROSPERO (CRD42020184903) and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) reporting guideline was followed.27 Ethics review was not required for the study. Electronic searches were conducted in collaboration with a health sciences librarian in PsycInfo, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Embase, and MEDLINE from inception to February 16, 2021. The search strategy (eTable 1 in the Supplement) combined search terms from 3 themes: (1) mental illness (including depression and anxiety), (2) COVID-19, and (3) children and adolescents (age ≤18 years). Both database and subject headings were used to search keywords. As a result of the rapidly evolving nature of research during the COVID-19 pandemic, we also searched a repository of unpublished preprints, PsycArXiv. The key terms COVID-19, mental health, and child/adolescent were used on March 8, 2021, and yielded 38 studies of which 1 met inclusion criteria.

The following inclusion criteria were applied: (1) sample was drawn from a general population; (2) proportion of individuals meeting clinical cutoff scores or falling in the moderate to severe symptom range of anxiety or depression as predetermined by validated self-report measures were provided; (3) data were collected during COVID-19; (4) participants were 18 years or younger; (5) study was empirical; and (6) studies were written in English. Samples of participants who may be affected differently from a mental health perspective during COVID-19 were excluded (eg, children with preexisting psychiatric diagnoses, children with chronic illnesses, children diagnosed or suspected of having COVID-19). We also excluded case studies and qualitative analyses.

Five (N.R., B.A.M., J.E.C., R.E. and J.Z.) authors used Covidence software (Covidence Inc) to review all abstracts and to determine if the study met criteria for inclusion. Twenty percent of abstracts reviewed for inclusion were double-coded, and the mean random agreement probability was 0.89; disagreements were resolved via consensus with the first author (N.R.). Two authors (N.R. and B.A.M.) reviewed full-text articles to determine if they met all inclusion criteria and the percent agreement was 0.80; discrepancies were resolved via consensus.

Data Extraction

When studies met inclusion criteria, prevalence rates for anxiety and depression were extracted, as well as potential moderators. When more than 1 wave of data was provided, the wave with the largest sample size was selected. For 1 study in which both parent and youth reports were provided,26 the youth report was selected, given research that they are the reliable informants of their own behavior.28 The following moderators were extracted: (1) study quality (see the next subsection); (2) participant age (continuously as a mean); (3) sex (% female in a sample); (4) geographical region (eg, East Asia, Europe, North America), (5) informant (child, parent), (6) month in 2020 when data were collected (range, 1-12). Data from all studies were extracted by 1 coder and the first author (N.R.). Discrepancies were resolved via consensus.

Study Quality

Adapted from the National Institute of Health Quality Assessment Tool for Observation Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies, a short 5-item questionnaire was used (eTable 2 in the Supplement).29 Studies were given a score of 0 (no) or 1 (yes) for each of the 5 criteria (validated measure; peer-reviewed, response rate ≥50%, objective assessment, sufficient exposure time) and summed to give a total score of 5. When information was unclear or not provided by the study authors, it was marked as 0 (no).

Data Analysis

All included studies are from independent samples. Comprehensive Meta-Analysis version 3.0 (Biostat) software was used for data analysis. Pooled prevalence estimates with associated 95% confidence intervals around the estimate were computed. We weighted pooled prevalence estimates by the weight of the inverse of their variance, which gives greater weight to large sample sizes.

We used random-effects models to reflect the variations observed across studies and assessed between-study heterogeneity using the Q and I2 statistics. Pooled prevalence is reported as an event rate (ie, 0.30) but interpreted as prevalence (ie, 30.0%). Significant Q statistics and I2 values more than 75% suggest moderator analyses should be explored.30 As recommended by Bornstein et al,30 we examined categorical moderators when k of 10 or higher and a minimum cell size of k more than 3 were available. A P value of .05 was considered statistically significant. For continuous moderators, random-effect meta-regression analyses were conducted. Publication bias was examined using the Egger test31 and by inspecting funnel plots for symmetry.

Results

Our electronic search yielded 3094 nonduplicate records (eFigure 1 in the Supplement). Based on the abstract review, a total of 136 full-text articles were retrieved to examine against inclusion criteria, and 29 nonoverlapping studies10,12,13,17,19,20,26,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53 met full inclusion criteria.

Study Characteristics

A total of 29 studies were included in the meta-analyses, of which 26 had youth symptom reports and 3 studies39,42,48 had parent reports of child symptoms. As outlined in Table 1, across all 29 studies, 80 879 participants were included, of which the mean (SD) perecentage of female individuals was 52.7% (12.3%), and the mean age was 13.0 years (range, 4.1-17.6 years). All studies provided binary reports of sex or gender. Sixteen studies (55.2%) were from East Asia, 4 were from Europe (13.8%), 6 were from North America (20.7%), 2 were from Central America and South America (6.9%), and 1 study was from the Middle East (3.4%). Eight studies (27.6%) reported having racial or ethnic minority participants with the mean across studies being 36.9%. Examining study quality, the mean score was 3.10 (range, 2-4; eTable 3 in the Supplement).

Table 1. Characteristics of Studies Included.

| Source | No.a | Age, y | Female, % | Country | Racial and ethnic minority, %b | Mental health measured | Name of mental health measures | Data collection date | Published |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlAzzam et al,32 2021 | 384 | 17.6 | 60.2 | Jordan | 0 | Anxiety, depression | GAD-7, PHQ-9 | NR | Yes |

| Asanov et al,33 2021 | 1550 | Grade 10-12 | 54.3 | Ecuador | 16 | Depression | MHI-5 | March 31 to May 3, 2020 | Yes |

| Cao et al,34 2021 | 11 180 | 14.3 | 49.9 | China | 0 | Anxiety, depression | GAD-7, PHQ-9 | March 20-31, 2020 | Yes |

| Cheah et al,35 2020 | 230 | 13.8 | 47.9 | US | 100 | Anxiety | GAD-7 | March 14 to May 31, 2020 | Yes |

| Chen et al,36 2020 | 1036 | 6-15 | 48.7 | China | 0 | Anxiety, depression | SCARED, DSRS-C | April 16 to 23, 2020 | Yes |

| Chen et al,37 2020 | 7772 | Grade 7-12 | 52.2 | China | 0 | Anxiety, depression | GAD-7, PHQ-9 | February 22 to March 8, 2020 | Yes |

| Chi et al,38 2021 | 1794 | 15.3 | 43.9 | China | 0 | Anxiety, depression | GAD-7, PHQ-9 | May 13 to 20, 2020 | Yes |

| Crescentini et al,39 2020 | 721 | 10.1 | 48.4 | Italy | 1.7 | Anxiety, depression | CBCL | April 16 to May 7, 2020 | Yes |

| Dong et al,40 2020 | 2050 | 12.3 | 48.4 | China | 0 | Anxiety, depression | DASS-21 | February 19 to March 15, 2020 | Yes |

| Duan et al,20 2020 | 3613 | 7-18 | 49.8 | China | 0 | Depression | CDI | March 2020 | Yes |

| Garcia de Avila et al,41 2020 | 289 | 8.8 | 54.3 | Brazil | NR | Anxiety | CAQ | April 25 to May 25, 2020 | Yes |

| Giannopoulou et al,13 2021 | 442 | NA | 68.8 | Greece | NR | Anxiety, depression | GAD-7, PHQ-9 | April 16 to 30, 2020 | Yes |

| Glynn et al,42 2021 | 168 | 4.1 | 46.7 | US | 67.5 | Depression | Preschool Feelings Checklist | May 5 to June 9, 2020 | Yes |

| Hou et al,43 2020 | 859 | <16 | 38.6 | China | 0 | Anxiety, depression | GAD-7, PHQ-9 | NR | Yes |

| Li et al,44 2021 | 7890 | 12-18 | 52.1 | China | 0 | Anxiety, depression | HADS | March 30 to April 7, 2020 | Yes |

| Luthar et al,45 2021 | 2078 | Grade 9-12 | 52.0 | US | 39.7 | Anxiety, depression | Well-Being Index | NR | Yes |

| McGuine et al,46 2020 | 13 002 | 16.3 | 52.9 | US | NR | Anxiety, depression | GAD-7, PHQ-9 | April to May 2020 | Yes |

| MacTavish et al,26 2020 | 158 (Anxiety), 156 (depression) | 10.8 | 49.5 | Canada | 25.8 | Anxiety, depression | SCARED, SMFQ | June to July 2020 | Yes |

| Murata et al,47 2021 | 464 (Anxiety), 455 (depression) | 15.8 | 80.0 | US | 29 | Anxiety, depression | GAD-7, PHQ-9 | April 27 to July 13, 2020 | Yes |

| Orgilés et al,48 2021 | 509 (Anxiety), 515 (depression) | 9.0 | 45.8 | Italy, Spain, Portugal | NR | Anxiety, depression | SCAS-P-8, SMFQ-P | March to May 2020 | Yes |

| Ravens-Sieberer et al,49 2021 | 1040 | 14.3 | 51.1 | Germany | 15.5 Migrants | Anxiety | SCARED | May 26 to June 10, 2020 | Yes |

| Tang et al,50 2021 | 4342 | 11.9 | 49.0 | China | 0 | Anxiety, depression | DASS-21 | March 13 to 23, 2020 | Yes |

| Xie et al,19 2020 | 1784 | Grade 2-6 | 43.3 | China | 0 | Anxiety, depression | SCARED, CDI-SF | February 28 to March 5, 2020 | Yes |

| Yue et al,12 2020 | 1356 (Anxiety), 1352 (depression) | 10.6 | 46.0 | China | 0 | Anxiety, depression | SAS, CES-DC | February 13 to 29, 2020 | Yes |

| Zhang et al,53 2020 | 1025 | 15.6 | 48.5 | China | 0 | Anxiety, depression | DASS-21 | April 7 to 24, 2020 | Yes |

| Zhang et al,10 2020 | 1241 | 12.6 | 40.7 | China | 0 | Anxiety, depression | MHBQ, MFQ | May 2020 | Yes |

| Zhang et al,52 2020 | 1018 | 16.6 | 53.5 | China | 0 | Anxiety, depression | GAD-7, PHQ-9 | May 1 to 7, 2020 | Yes |

| Zhou et al,51 2020 | 4805 | 15 | 100 | China | 0 | Depression | CESD | February 20 to 27, 2020 | Yes |

| Zhou et al,17 2020 | 8079 | 16 | 53.5 | China | 0 | Anxiety, depression | GAD-7, PHQ-9 | March 8 to 15, 2020 | Yes |

Abbreviations: CAQ, Child Anxiety Questionnaire; CBCL, Child Behavior Checklist; CDI, Child Depression Inventory; CDI-SF, Child Depression Inventory, Short Form; CES-D, Centre for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale; DASS-21, Depression, Anxiety, and Stress Scale; DSRS-C, Depression Self-rating Scale for Children; GAD-7, Generalized Anxiety Disorder–7; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; MHBQ, MacArthur Health and Behavior Questionnaire; MHI-5, Mental Health Inventory-5; MFQ, Mood and Feelings Questionnaire; NA, not applicable; NR, not reported; PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire–9; SAS, Self-rating Anxiety Scale; SCAS-P-8, Spence Children’s Anxiety Scale–Parent Version; SCARED, Screen for Child Anxiety Related Disorders; SMFQ, Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire; SMFQ-P, Short Mood and Feelings Questionnaire–Parent Version.

Sample size entered into the meta-analysis.

When race or ethnicity was not explicitly reported but it could be assumed that the study was conducted with a homogeneous or dominant group, a score of 0 was allocated. When the racial and ethnic composition of the sample was not reported in large samples in geographic regions that are known to be ethnically and racially diverse, this variable was coded as missing.

Pooled Prevalence of Clinically Elevated Depressive Symptoms in Youth During COVID-19

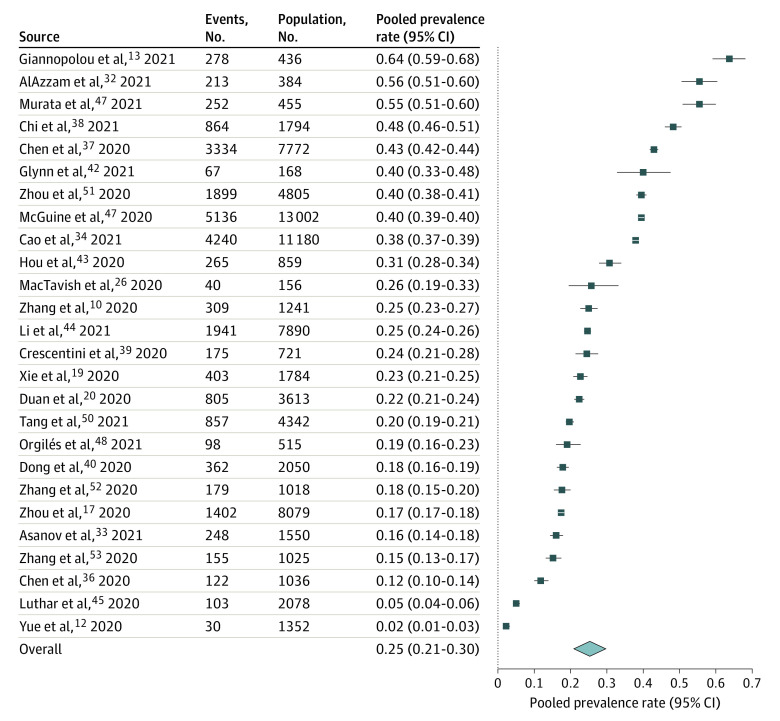

The pooled prevalence from a random-effects meta-analysis of 26 studies revealed a pooled prevalence rate of 0.25 (95% CI, 0.21-0.30; Figure 1) or 25.2%. The funnel plot was symmetrical (eFigure 2 in the Supplement); however, the Egger test was statistically significant (intercept, −9.5; 95% CI, −18.4 to −0.48; P = .02). The between-study heterogeneity statistic was significant (Q = 4675.91; P < .001; I2 = 99.47). Significant moderators are reported below, and all moderator analyses are presented in Table 2.

Figure 1. Forest Plots of the Pooled Prevalence of Clinically Significant Depressive Symptoms in Youth During the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Contributing studies for clinically elevated depression symptoms are presented in order of largest to smallest prevalence rate. Square data markers represent prevalence rates, with lines around the marker indicating 95% CIs. The diamond data marker represents the overall effect size based on included studies.

Table 2. Results of Moderator Analyses for the Prevalence of Depressive Symptoms in Children and Adolescence During COVID-19.

| Categorical moderators | No. of studies | Prevalence (95% CI) | Homogeneity Q | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study quality scorea | ||||

| 2-3 | 21a | 0.27 (0.23-0.32)b | 3.64 | .06 |

| 4 | 5 | 0.18 (0.11-0.26)b | ||

| Symptom reporter | ||||

| Self-report | 23 | 0.25 (0.208-0.30)b | 0.06 | .80 |

| Parent report | 3 | 0.27 (0.16-0.42)c | ||

| Geographical region | ||||

| East Asia | 16 | 0.22 (0.17-0.28)b | 2.83 | .24 |

| North America | 5 | 0.28 (0.19-0.41)d | ||

| Europe | 3 | 0.34 (0.20-0.51) | ||

| Continuous moderators | No. of studies | Estimate (95% CI) | z | P value |

| Participant | ||||

| Age | 26 | 0.08 (0.01-0.15) | 2.10 | .04 |

| Sex | 26 | 0.03 (0.01-0.05) | 3.03 | .002 |

| Month of data collection in 2020 | 23 | 0.26 (0.06-0.46) | 2.54 | .01 |

Two studies had a study quality of 2 and were combined with those with a study quality of 3.

P < .001.

P = .01.

As the number of months in the year increased, so too did the prevalence of depressive symptoms (b = 0.26; 95% CI, 0.06-0.46). Prevalence rates were higher as child age increased (b = 0.08; 95% CI, 0.01-0.15), and as the percentage of female individuals (b = 0.03; 95% CI, 0.01-0.05) in samples increased. Sensitivity analyses removing low-quality studies were conducted (ie, scores of 2)32,43 (eTable 4 in the Supplement). Moderators remained significant, except for age, which became nonsignificant (b = 0.06; 95% CI, −0.02 to 0.13; P = .14).

Pooled Prevalence of Clinically Elevated Anxiety Symptoms in Youth During COVID-19

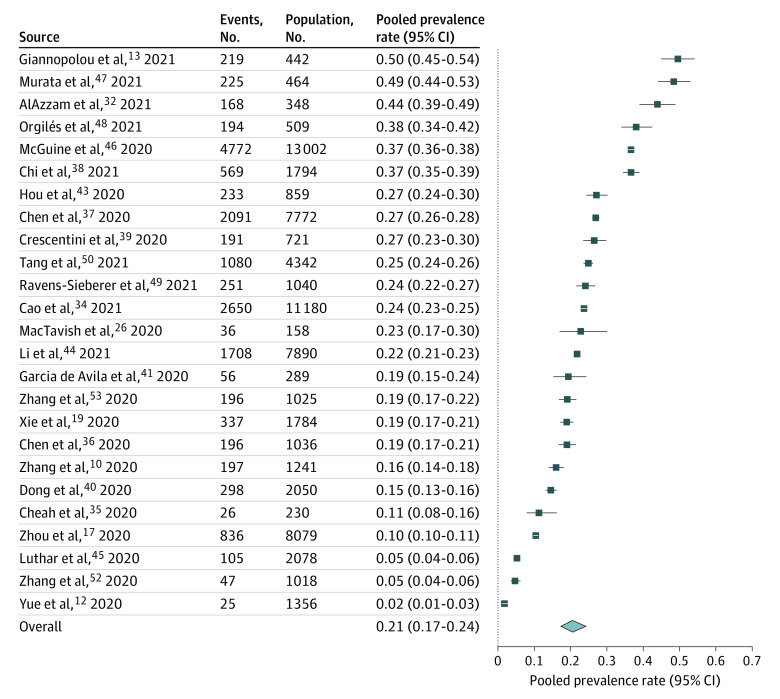

The overall pooled prevalence rate across 25 studies for elevated anxiety was 0.21 (95% CI, 0.17-0.24; Figure 2) or 20.5%. The funnel plot was symmetrical (eFigure 3 in the Supplement) and the Egger test was nonsignificant (intercept, −6.24; 95% CI, −14.10 to 1.62; P = .06). The heterogeneity statistic was significant (Q = 3300.17; P < .001; I2 = 99.27). Significant moderators are reported below, and all moderator analyses are presented in Table 3.

Figure 2. Forest Plots of the Pooled Prevalence of Clinically Significant Anxiety Symptoms in Youth During the COVID-19 Pandemic.

Contributing studies for clinically elevated anxiety symptoms are presented in order of largest to smallest prevalence rate. Square data markers represent prevalence rates, with lines around the marker indicating 95% CIs. The diamond data marker represents the overall effect size based on included studies.

Table 3. Results of Moderator Analyses for the Prevalence of Anxiety Symptoms in Children and Adolescence During COVID-19.

| Categorical moderatorsa | No. of studies | Prevalence (95% CI) | Homogeneity Q | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study quality score | ||||

| 2-3 | 21b | 0.22 (0.18 to 0.27)c | 4.92 | .03 |

| 4 | 4 | 0.12 (0.07 to 0.20)d | ||

| Geographical region | ||||

| East Asia | 14 | 0.17 (0.13 to 0.21)d | 10.04 | .01 |

| North America | 5 | 0.21 (0.14 to 0.30)d | ||

| Europe | 4 | 0.34 (0.23 to 0.46)e | ||

| Continuous moderators | k | Estimate (95% CI) | z | P value |

| Participant | ||||

| Age | 25 | 0.07 (−0.02 to 0.15) | 1.53 | .13 |

| Sex | 25 | 0.04 (0.01 to 0.07) | 2.95 | .003 |

| Month of data collection in 2020 | 22 | 0.27 (0.10 to 0.44) | 3.10 | .001 |

Symptom reporter (self-report vs parent report) could not be examined as there were insufficient studies at each level of the categorical comparison (ie, 2 studies had parent report).

Two studies had a study quality of 2 and were combined with those with a study quality of 3.

P < .001.

P < .05.

P = .002.

As the number of months in the year increased, so too did the prevalence of anxiety symptoms (b = 0.27; 95% CI, 0.10-0.44). Prevalence rates of clinically elevated anxiety was higher as the percentage of female individuals in the sample increased (b = 0.04; 95% CI, 0.01-0.07) and also higher in European countries (k = 4; rate = 0.34; 95% CI, 0.23-0.46; P = .01) compared with East Asian countries (k = 14; rate = 0.17; 95% CI, 0.13-0.21; P < .001). Lastly, the prevalence of clinically elevated anxiety was higher in studies deemed to have poorer quality (k = 21; rate = 0.22; 95% CI, 0.18-0.27; P < .001) compared with studies with better study quality scores (k = 4; rate = 0.12; 95% CI, 0.07-0.20; P < .001). Sensitivity analyses removing low quality studies (ie, scores of 2)32,43 yielded the same pattern of results (eTable 5 in the Supplement).

Discussion

The current meta-analysis provides a timely estimate of clinically elevated depression and generalized anxiety symptoms globally among youth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Across 29 samples and 80 879 youth, the pooled prevalence of clinically elevated depression and anxiety symptoms was 25.2% and 20.5%, respectively. Thus, 1 in 4 youth globally are experiencing clinically elevated depression symptoms, while 1 in 5 youth are experiencing clinically elevated anxiety symptoms. A comparison of these findings to prepandemic estimates (12.9% for depression2 and 11.6% for anxiety1) suggests that youth mental health difficulties during the COVID-19 pandemic has likely doubled.

The COVID-19 pandemic, and its associated restrictions and consequences, appear to have taken a considerable toll on youth and their psychological well-being. Loss of peer interactions, social isolation, and reduced contact with buffering supports (eg, teachers, coaches) may have precipitated these increases.3 In addition, schools are often a primary location for receiving psychological services, with 80% of children relying on school-based services to address their mental health needs.54 For many children, these services were rendered unavailable owing to school closures.

As the month of data collection increased, rates of depression and anxiety increased correspondingly. One possibility is that ongoing social isolation,6 family financial difficulties,55 missed milestones, and school disruptions3 are compounding over time for youth and having a cumulative association. However, longitudinal research supporting this possibility is currently scarce and urgently needed. A second possibility is that studies conducted in the earlier months of the pandemic (February to March 2020)12,51 were more likely to be conducted in East Asia where self-reported prevalence of mental health symptoms tends to be lower.56 Longitudinal trajectory research on youth well-being as the pandemic progresses and in pandemic recovery phases will be needed to confirm the long-term mental health implications of the COVID-19 pandemic on youth mental illness.

Prevalence rates for anxiety varied according to study quality, with lower-quality studies yielding higher prevalence rates. It is important to note that in sensitivity analyses removing lower-quality studies, other significant moderators (ie, child sex and data collection time point) remained significant. There has been a rapid proliferation of youth mental health research during the COVID-19 pandemic; however, the rapid execution of these studies has been criticized owing to the potential for some studies to sacrifice methodological quality for methodological rigor.21,57 Additionally, several studies estimating prevalence rates of mental illness during the pandemic have used nonprobability or convenience samples, which increases the likelihood of bias in reporting.21 Studies with representative samples and/or longitudinal follow-up studies that have the potential to demonstrate changes in mental health symptoms from before to after the pandemic should be prioritized in future research.

In line with previous research on mental illness in childhood and adolescence,58 female sex was associated with both increased depressive and anxiety symptoms. Biological susceptibility, lower baseline self-esteem, a higher likelihood of having experienced interpersonal violence, and exposure to stress associated with gender inequity may all be contributing factors.59 Higher rates of depression in older children were observed and may be due to puberty and hormonal changes60 in addition to the added effects of social isolation and physical distancing on older children who particularly rely on socialization with peers.6,61 However, age was not a significant moderator for prevalence rates of anxiety. Although older children may be more acutely aware of the stress of their parents and the implications of the current global pandemic, younger children may be able to recognize changes to their routine, both of which may contribute to similar rates of anxiety with different underlying mechanisms.

In terms of practice implications, a routine touch point for many youth is the family physician or pediatrician’s office. Within this context, it is critical to inquire about or screen for youth mental health difficulties. Emerging research42 suggests that in families using more routines during COVID-19, lower child depression and conduct problems are observed. Thus, a tangible solution to help mitigate the adverse effects of COVID-19 on youth is working with children and families to implement consistent and predictable routines around schoolwork, sleep, screen use, and physical activity. Additional resources should be made available, and clinical referrals should be placed when children experience clinically elevated mental distress. At a policy level, research suggests that social isolation may contribute to and confer risk for mental health concerns.4,5 As such, the closure of schools and recreational activities should be considered a last resort.62 In addition, methods of delivering mental health resources widely to youth, such as group and individual telemental health services, need to be adapted to increase scalability, while also prioritizing equitable access across diverse populations.63

Limitations

There are some limitations to the current study. First, although the current meta-analysis includes global estimates of child and adolescent mental illness, it will be important to reexamine cross-regional differences once additional data from underrepresented countries are available. Second, most study designs were cross-sectional in nature, which precluded an examination of the long-term association of COVID-19 with child mental health over time. To determine whether clinically elevated symptoms are sustained, exacerbated, or mitigated, longitudinal studies with baseline estimates of anxiety and depression are needed. Third, few studies included racial or ethnic minority participants (27.6%), and no studies included gender-minority youth. Given that racial and ethnic minority64 and gender-diverse youth65,66 may be at increased risk for mental health difficulties during the pandemic, future work should include and focus on these groups. Finally, all studies used self- or parent-reported questionnaires to examine the prevalence of clinically elevated (ie, moderate to high) symptoms. Thus, studies using criterion standard assessments of child depression and anxiety disorders via diagnostic interviews or multimethod approaches may supplement current findings and provide further details on changes beyond generalized anxiety symptoms, such symptoms of social anxiety, separation anxiety, and panic.

Conclusions

Overall, this meta-analysis shows increased rates of clinically elevated anxiety and depression symptoms for youth during the COVID-19 pandemic. While this meta-analysis supports an urgent need for intervention and recovery efforts aimed at improving child and adolescent well-being, it also highlights that individual differences need to be considered when determining targets for intervention (eg, age, sex, exposure to COVID-19 stressors). Research on the long-term effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, including studies with pre– to post–COVID-19 measurement, is needed to augment understanding of the implications of this crisis on the mental health trajectories of today’s children and youth.

eTable 1. Example Search Strategy from Medline

eTable 2. Study Quality Evaluation Criteria

eTable 3. Quality Assessment of Studies Included

eTable 4. Sensitivity analysis excluding low quality studies (score=2) for moderators of the prevalence of clinically elevated depressive symptoms in children and adolescence during COVID-19

eTable 5. Sensitivity analysis excluding low quality studies (score=2) for moderators of the prevalence of clinically elevated anxiety symptoms in children and adolescence during COVID-19

eFigure 1. PRISMA diagram of review search strategy

eFigure 2. Funnel plot for studies included in the clinically elevated depressive symptoms

eFigure 3. Funnel plot for studies included in the clinically elevated anxiety symptoms

References

- 1.Tiirikainen K, Haravuori H, Ranta K, Kaltiala-Heino R, Marttunen M. Psychometric properties of the 7-item Generalized Anxiety Disorder Scale (GAD-7) in a large representative sample of Finnish adolescents. Psychiatry Res. 2019;272:30-35. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu W. Adolescent depression: National trends, risk factors, and healthcare disparities. Am J Health Behav. 2019;43(1):181-194. doi: 10.5993/AJHB.43.1.15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lee J. Mental health effects of school closures during COVID-19. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(6):421. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30109-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sprang G, Silman M. Posttraumatic stress disorder in parents and youth after health-related disasters. Disaster Med Public Health Prep. 2013;7(1):105-110. doi: 10.1017/dmp.2013.22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brooks SK, Webster RK, Smith LE, et al. The psychological impact of quarantine and how to reduce it: rapid review of the evidence. Lancet. 2020;395(10227):912-920. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30460-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Loades ME, Chatburn E, Higson-Sweeney N, et al. Rapid systematic review: the impact of social isolation and loneliness on the mental health of children and adolescents in the context of COVID-19. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;59(11):1218-1239.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2020.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Golberstein E, Wen H, Miller BF. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) and mental health for children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(9):819-820. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1456 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Racine N, Cooke JE, Eirich R, Korczak DJ, McArthur B, Madigan S. Child and adolescent mental illness during COVID-19: a rapid review. Psychiatry Res. 2020;292:113307. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh S, Roy D, Sinha K, Parveen S, Sharma G, Joshi G. Impact of COVID-19 and lockdown on mental health of children and adolescents: a narrative review with recommendations. Psychiatry Res. 2020;293:113429. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang L, Zhang D, Fang J, Wan Y, Tao F, Sun Y. Assessment of mental health of Chinese primary school students before and after school closing and opening during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(9):e2021482. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21482 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hafstad GS, Sætren SS, Wentzel-Larsen T, Augusti E. Adolescents’ symptoms of anxiety and depression before and during the Covid-19 outbreak: a prospective population-based study of teenagers in Norway. Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021;5:100093. doi: 10.1016/j.lanepe.2021.100093 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yue J, Zang X, Le Y, An Y. Anxiety, depression and PTSD among children and their parent during 2019 novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) outbreak in China. Curr Psychol. 2020;1-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Giannopoulou I, Efstathiou V, Triantafyllou G, Korkoliakou P, Douzenis A. Adding stress to the stressed: senior high school students’ mental health amidst the COVID-19 nationwide lockdown in Greece. Psychiatry Res. 2021;295:113560. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication—Adolescent Supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980-989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 5th ed. American Psychiatric Association; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Courtney D, Watson P, Battaglia M, Mulsant BH, Szatmari P. COVID-19 impacts on child and youth anxiety and depression: challenges and opportunities. Can J Psychiatry. 2020;65(10):688-691. doi: 10.1177/0706743720935646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhou SJ, Zhang LG, Wang LL, et al. Prevalence and socio-demographic correlates of psychological health problems in Chinese adolescents during the outbreak of COVID-19. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2020;29(6):749-758. doi: 10.1007/s00787-020-01541-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Magson NR, Freeman JYA, Rapee RM, Richardson CE, Oar EL, Fardouly J. Risk and protective factors for prospective changes in adolescent mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Youth Adolesc. 2021;50(1):44-57. doi: 10.1007/s10964-020-01332-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Xie X, Xue Q, Zhou Y, et al. Mental health status among children in home confinement during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak in Hubei Province, China. JAMA Pediatr. 2020;174(9):898-900. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.1619 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Duan L, Shao X, Wang Y, et al. An investigation of mental health status of children and adolescents in China during the outbreak of COVID-19. J Affect Disord. 2020;275:112-118. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.06.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pierce M, McManus S, Jessop C, et al. Says who? the significance of sampling in mental health surveys during COVID-19. Lancet Psychiatry. 2020;7(7):567-568. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(20)30237-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Klein R. Parent-child agreement in clinical assessment of anxiety and other psychopathology: a review. J Anxiety Disord. 1991;5(2):187-198. doi: 10.1016/0887-6185(91)90028-R [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edelbrock C, Costello AJ, Dulcan MK, Conover NC, Kala R. Parent-child agreement on child psychiatric symptoms assessed via structured interview. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1986;27(2):181-190. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.1986.tb02282.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hawes MT, Szenczy AK, Olino TM, Nelson BD, Klein DN. Trajectories of depression, anxiety and pandemic experiences: a longitudinal study of youth in New York during the spring-summer of 2020. Psychiatry Res. 2021;298:113778. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2021.113778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cost KT, Crosbie J, Anagnostou E, et al. Mostly worse, occasionally better: impact of COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of Canadian children and adolescents. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01744-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.MacTavish A, Mastronardi C, Menna R, et al. The acute impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on children’s mental health in southwestern Ontario. PsyArXiv. Preprint posted online September 19, 2020. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/5cwb4 [DOI]

- 27.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group . Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7):e1000097. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ebesutani C, Bernstein A, Martinez JI, Chorpita BF, Weisz JR. The youth self report: applicability and validity across younger and older youths. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2011;40(2):338-346. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2011.546041 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. Study quality assessment tools: quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. Accessed July 6, 2021. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

- 30.Borenstein M, Hesdges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H.. Introduction to Meta-Analysis. Wiley; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629-634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.AlAzzam M, Abuhammad S, Abdalrahim A, Hamdan-Mansour AM. Predictors of depression and anxiety among senior high school students during COVID-19 pandemic: the context of home quarantine and online education. J Sch Nurs. 2021;1059840520988548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asanov I, Flores F, McKenzie D, Mensmann M, Schulte M. Remote-learning, time-use, and mental health of Ecuadorian high-school students during the COVID-19 quarantine. World Dev. 2021;138:105225. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cao Y, Huang L, Si T, Wang NQ, Qu M, Zhang XY. The role of only-child status in the psychological impact of COVID-19 on mental health of Chinese adolescents. J Affect Disord. 2021;282:316-321. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.12.113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cheah CSL, Wang C, Ren H, Zong X, Cho HS, Xue X. COVID-19 racism and mental health in Chinese American families. Pediatrics. 2020;146(5):e2020021816. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-021816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen F, Zheng D, Liu J, Gong Y, Guan Z, Lou D. Depression and anxiety among adolescents during COVID-19: a cross-sectional study. Brain Behav Immun. 2020;88:36-38. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2020.05.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chen S, Cheng Z, Wu J. Risk factors for adolescents’ mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic: a comparison between Wuhan and other urban areas in China. Global Health. 2020;16(1):96. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00627-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chi X, Liang K, Chen ST, et al. Mental health problems among Chinese adolescents during the COVID-19: the importance of nutrition and physical activity. Int J Clin Health Psychol. 2021;21(3):100218. doi: 10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.100218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crescentini C, Feruglio S, Matiz A, et al. Stuck outside and inside: an exploratory study on the effects of the COVID-19 outbreak on Italian parents and children’s internalizing symptoms. Front Psychol. 2020;11:586074. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.586074 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Dong H, Yang F, Lu X, Hao W. Internet addiction and related psychological factors among children and adolescents in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) epidemic. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:00751. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garcia de Avila MA, Hamamoto Filho PT, Jacob FLDS, et al. Children’s anxiety and factors related to the COVID-19 pandemic: an exploratory study using the Children’s Anxiety Questionnaire and the Numerical Rating Scale. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020;17(16):E5757. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17165757 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Glynn LM, Davis EP, Luby JL, Baram TZ, Sandman CA. A predictable home environment may protect child mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurobiol Stress. 2021;14:100291. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2020.100291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hou TY, Mao XF, Dong W, Cai WP, Deng GH. Prevalence of and factors associated with mental health problems and suicidality among senior high school students in rural China during the COVID-19 outbreak. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020;54:102305. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li W, Zhang Y, Wang J, et al. Association of home quarantine and mental health among teenagers in Wuhan, China, during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Pediatr. 2021;175(3):313-316. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2020.5499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Luthar SS, Ebbert AM, Kumar NL. Risk and resilience during COVID-19: a new study in the Zigler paradigm of developmental science. Dev Psychopathol. 2021;33(2):565-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.McGuine TA, Biese KM, Petrovska L, et al. Mental health, physical activity, and quality of life of us adolescent athletes during COVID-19-related school closures and sport cancellations: a study of 13 000 athletes. J Athl Train. 2020. doi: 10.4085/478-20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murata S, Rezeppa T, Thoma B, et al. The psychiatric sequelae of the COVID-19 pandemic in adolescents, adults, and health care workers. Depress Anxiety. 2021;38(2):233-246. doi: 10.1002/da.23120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Orgilés M, Espada JP, Delvecchio E, et al. Anxiety and depressive symptoms in children and adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic: a transcultural approach. Psicothema. 2021;33(1):125-130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ravens-Sieberer U, Kaman A, Erhart M, Devine J, Schlack R, Otto C. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on quality of life and mental health in children and adolescents in Germany. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2021. doi: 10.1007/s00787-021-01726-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tang S, Xiang M, Cheung T, Xiang YT. Mental health and its correlates among children and adolescents during COVID-19 school closure: the importance of parent-child discussion. J Affect Disord. 2021;279:353-360. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhou J, Yuan X, Qi H, et al. Prevalence of depression and its correlative factors among female adolescents in China during the coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak. Global Health. 2020;16(1):69. doi: 10.1186/s12992-020-00601-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Zhang Z, Zhai A, Yang M, et al. Prevalence of depression and anxiety symptoms of high school students in Shandong province during the COVID-19 epidemic. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:570096. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.570096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zhang C, Ye M, Fu Y, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on teenagers in China. J Adolesc Health. 2020;67(6):747-755. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.08.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Masonbrink AR, Hurley E. Advocating for children during the COVID-19 school closures. Pediatrics. 2020;146(3):e20201440. doi: 10.1542/peds.2020-1440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schaller J, Zerpa M. Short-run effects of parental job loss on child health. Am J Health Econ. 2019;5(1):8-41. doi: 10.1162/ajhe_a_00106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Marques L, Robinaugh DJ, LeBlanc NJ, Hinton D. Cross-cultural variations in the prevalence and presentation of anxiety disorders. Expert Rev Neurother. 2011;11(2):313-322. doi: 10.1586/ern.10.122 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Rzymski P, Nowicki M, Mullin GE, et al. Quantity does not equal quality: scientific principles cannot be sacrificed. Int Immunopharmacol. 2020;86:106711. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2020.106711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Essau CA, Lewinsohn PM, Seeley JR, Sasagawa S. Gender differences in the developmental course of depression. J Affect Disord. 2010;127(1-3):185-190. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.05.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Riecher-Rössler A. Sex and gender differences in mental disorders. Lancet Psychiatry. 2017;4(1):8-9. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(16)30348-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Oldehinkel AJ, Verhulst FC, Ormel J. Mental health problems during puberty: Tanner stage-related differences in specific symptoms: the TRAILS study. J Adolesc. 2011;34(1):73-85. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2010.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hall-Lande JA, Eisenberg ME, Christenson SL, Neumark-Sztainer D. Social isolation, psychological health, and protective factors in adolescence. Adolescence. 2007;42(166):265-286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Christakis DA, Van Cleve W, Zimmerman FJ. Estimation of US children’s educational attainment and years of life lost associated with primary school closures during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2028786. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.28786 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Madigan S, Racine N, Cooke JE, Korczak DJ. COVID-19 and telemental health: benefits, challenges, and future directions. Can Psychol. 2021;62(1):5-11. doi: 10.1037/cap0000259 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Webb Hooper M, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020;323(24):2466-2467. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Hawke LD, Hayes E, Darnay K, Henderson J. Mental health among transgender and gender diverse youth: an exploration of effects during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. Published online February 4, 2021. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000467 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Craig S, Ames ME, Bondi BC, Pepler DJ. Canadian Adolescents’ mental health and substance use during the covid-19 pandemic: associations with COVID-19 stressors. PsyArXiv. Preprint posted online September 9, 2020. doi: 10.31234/osf.io/kprd9 [DOI]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable 1. Example Search Strategy from Medline

eTable 2. Study Quality Evaluation Criteria

eTable 3. Quality Assessment of Studies Included

eTable 4. Sensitivity analysis excluding low quality studies (score=2) for moderators of the prevalence of clinically elevated depressive symptoms in children and adolescence during COVID-19

eTable 5. Sensitivity analysis excluding low quality studies (score=2) for moderators of the prevalence of clinically elevated anxiety symptoms in children and adolescence during COVID-19

eFigure 1. PRISMA diagram of review search strategy

eFigure 2. Funnel plot for studies included in the clinically elevated depressive symptoms

eFigure 3. Funnel plot for studies included in the clinically elevated anxiety symptoms