Abstract

INTRODUCTION:

Congenital facial weakness (CFW) can result from facial nerve paresis with or without other cranial nerve and systemic involvement, or generalized neuropathic and myopathic disorders. Moebius syndrome (MBS) is one type of CFW. This study explored the utility of electrodiagnostic studies (EDX) in the evaluation of individuals with CFW.

METHODS:

Forty-three subjects enrolled prospectively into a dedicated clinical protocol and had EDX evaluations, including blink reflex, facial and peripheral nerve conduction studies, with optional needle electromyography.

RESULTS:

MBS and hereditary congenital facial paresis (HCFP) subjects had low amplitude CN7 responses without other neuropathic or myopathic findings. Carriers of specific pathogenic variants in TUBB3 had, in addition, a generalized sensorimotor axonal polyneuropathy with demyelinating features. Myopathic findings were detected in individuals with Carey-Fineman-Ziter syndrome, myotonic dystrophy, other undefined myopathies or CFW with arthrogryposis, ophthalmoplegia and other system involvement.

DISCUSSION:

EDX in CFW subjects can assist in characterizing the underlying pathogenesis, as well as guide diagnosis and genetic counseling.

Keywords: Carey-Fineman-Ziter syndrome, CFEOM3A-TUBB3 mutations, Congenital cranial dysinnervation disorders, Facial nerve palsy, Hereditary congenital facial paresis, Moebius syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Congenital facial weakness (CFW) presents as decreased facial animation from birth, resulting from facial nucleus or nerve impairment, an inherent muscle disorder, or a defect at the neuromuscular junction.1–5 CFW may be a sporadic occurrence or segregate in an autosomal dominant or autosomal recessive inheritance pattern. Moreover, CFW can occur in isolation, as part of disorders affecting multiple cranial nerves, grouped as the “congenital cranial dysinnervation disorders” (CCDD)4, 6, 7, 8 or as a broader syndrome. One form of CFW, believed to be a CCDD, is Moebius syndrome (MBS), which presents with congenital, non-progressive facial weakness (CN7) with limited abduction (CN6) of one or both eyes.9–11 MBS is often associated with swallowing and speech difficulties (CN 9,10,12), limb anomalies, Poland syndrome, and in some cases intellectual disability and autism.2, 3, 10–14

Only a few genetic causes of CFW have been defined, while the molecular genetics in the majority of cases remains unknown. Inherited congenital facial weakness is referred to as Hereditary Congenital Facial Paresis (HCFP) and has been associated with facial nerve atrophy or absence.1, 15 HCFP3 results from autosomal recessive pathogenic variants in HOXB1 (OMIM 614744, HCFP3)16, while HCFP1 and 2 (OMIM 601471, 604185) are autosomal dominant and not genetically defined.17, 18 A subset of individuals with congenital fibrosis of extraocular muscles (CFEOM3A) who harbor specific dominant missense mutations in the TUBB3 gene have CFW, along with oculomotor nerve palsy (CN3), sensorimotor neuropathies, Kallmann syndrome (CN1), and intellectual and social disabilities.19–21 Most MBS cases are sporadic and genetically undefined, although a few cases harbor de novo variants in PLXND1 or REV3L.22 Carey-Finemann-Ziter (CFZ) syndrome is an autosomal recessive myopathy associated with facial and generalized muscle weakness, Robin sequence, arthrogryposis, and scoliosis, caused by pathogenic variants in myomaker (MYMK).5 Other primary muscle disorders associated with congenital or early facial weakness include facioscapulohumeral dystrophy23 , myotonic dystrophy, congenital myasthenic syndromes and congenital myopathies such as nemaline myopathy24, RYR1-related myopathies25, and STAC3 myopathy26. Local musculoskeletal anomalies, such as hemifacial myohyperplasia27and craniofacial microsomia, as well as, other syndromes, such as CHARGE (coloboma, heart defects, atresia choanae, growth retardation, genital abnormalities, and ear abnormalities)28, can present with asymmetric facial weakness. Finally, intrauterine cerebrovascular insults29 and toxic intrauterine exposures such as misoprostol exposure30 can lead to CFW.

This study evaluated subjects with CFW, referred mostly with a prior diagnosis of MBS. Utilizing electrodiagnostic (EDX) testing, we identified key features of CFW, differentiating generalized neuromuscular disorders from disorders limited primarily to facial weakness, thus better classifying subjects.

MATERIALS and METHODS.

Subjects:

Participants enrolled in the “Study on Moebius Syndrome and Other Congenital Facial Weakness Disorders” (NCT02055248) through the Moebius Syndrome Research Consortium (NIH/NICHD U01 HD079068), as part of a collaborative effort between the NIH Intramural Program, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, NYC, NY, and Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA, to conduct deep phenotyping in a cohort of subjects with CFW and elucidate potential genetic causes. Subjects were either self-referred or referred by members of the Moebius Syndrome Research Consortium and the Moebius Syndrome Foundation. Main inclusion criterion was a clinical diagnosis of isolated or syndromic congenital facial palsy, based on review of prior medical records and interview with the subject. The subjects were evaluated prospectively at the NIH Clinical Center. All subjects or their legal guardians signed an Institutional Review Board approved written consent. Enrollment dates were between 2014 and 2016 with 4 familial CFW subjects enrolled between 2010 and 2011 on a different protocol (NCT00369421) for evaluation of an underlying genetic etiology. The study included multimodality evaluation including family pedigree, genetic, ophthalmologic, audiology, dental and craniofacial, neuropsychiatric, and imaging studies. The data was analyzed by different members of the collaborative group based on their expertise. Only the neurological and EDX data are presented in this paper. Several subjects who self-identified or were previously diagnosed by their physician as MBS, received a different diagnosis after participation in the study.

Electrodiagnostic studies:

All of the EDX studies were performed in the EMG Lab at the NIH Clinical Center by one of the authors (TJL). Subjects underwent blink studies and cranial nerve 7 (CN7) motor nerve conduction studies (MNCS) using standard techniques. Blink studies were performed by stimulating at the supraorbital notch with bilateral periorbital recording sites. The CN7 MNCS were recorded in the upper face from the orbicularis oculi muscle (CN7-OOC), and in the lower face from the orbicularis oris muscle (CN7-OOR). Optional studies per protocol included median and fibular MNCS; median and sural sensory nerve conduction studies (SNCS); and needle EMG (NEMG) to face (orbicularis oculi, mentalis) and limbs (biceps brachii, tibialis anterior). The needle EMG was limited to subjects who agreed to NEMG and was not performed on pediatric subjects. EDX studies were performed on a Viking Select EMG machine (Natus, Middleton, WI). Published normal amplitudes for CN7 MNC OOC are ≥ 1.0 mV though not stated for CN7 MNC OOR.31 For the blink reflexes, the published normal latencies are: R1 ≤ 13 ms, ipsiR2 ≤ 41 ms, and contaR2 y ≤ 44 ms.31

Statistical Analysis:

The average of both CN7 MNC sides was used for statistical analysis since a paired t-test determined that there were no significant differences (p>0.95) between the sides. Non-parametric methods were used since the two variables did not fit normal distribution. For each subject group, Spearman correlation coefficient was used for assessing the relationship between age and CN7 amplitude, and one-sample Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test for evaluating the difference between CN7-OOC and CN7-OOR. Kruskal-Wallis test was applied to examine the difference in CN7 amplitude between the three subject groups (HCFP, MBS, CFEOM3A-TUBB3) since age did not have a significant effect on amplitude. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) and p<0.05 was used as significance level.

RESULTS:

Forty-three subjects (34 families) underwent EDX evaluation that included facial studies (Table 1). An additional two CFEOM3A-TUBB3 subjects and one CFZ subject only had peripheral NCS.

Table 1.

Demographics of Subjects with Facial EDX Studies.

| Disorder | Subject # | Families | Age (years) mean±std (range) | Gender |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Moebius, sporadic | 19 | 19 | 29.3±17.3 (8-64) |

13F; 6M |

| HCFP, undefined | 11 | 6 | 30.2±14.5 (10-57) |

4F; 7M |

| CFEOM3A-TUBB3 | 6 | 3 | 29.3±18.1 (12-61) |

4F; 2M |

| Carey-Fineman-Ziter- MYMK | 1 | 1 | 36 | 1M |

| Facial palsy, ophthalmoplegia, arthrogryposis | 3 | 2 | 25.7 (11-49) |

2F; 1M |

| Indeterminate muscle disorder | 1 | 1 | 37 | 1F |

| Myotonic dystrophy | 1 | 1 | 23 | 1M |

| Hemifacial myohyperplasia | 1 | 1 | 24 | 1F |

| Total | 43 | 34 | 28.4±15.6 (7-64) |

25F; 18M |

HFCP - Hereditary Congenital Facial Paresis; CFEOM - Congenital fibrosis of extraocular muscles, CFEOM3A-TUBB3; CFZS – Carey-Fineman- Ziter syndrome

Of the nineteen subjects with MBS, all had low or absent CN7 MNCS responses (Figure 1) though 4 subjects had unilateral normal responses; most subjects (n =16) had abnormal blink responses, although 3 had unilateral normal responses (Table 2). NEMG of facial muscles showed a neurogenic pattern with large motor unit potentials and reduced recruitment noted in the mentalis muscle (n=6) and OOC (n=2) though a few individuals had limited or no motor unit activation in these muscles (mentalis n=1, OOC n=3). One subject had only the frontalis tested with no motor unit activation. Only two subjects had peripheral nerve abnormalities in addition to their facial neuropathy; one had a sensory neuropathy associated with prior chemotherapy and another had a possible lumbar radiculopathy with low amplitude CMAP on stimulation of the fibular nerve, normal sural response, and NEMG showing large motor unit potentials in the tibialis anterior. Ten of the 19 MBS subjects had additional clinical findings including mild impairment of vertical gaze, tongue weakness, and upper and lower limb anomalies.

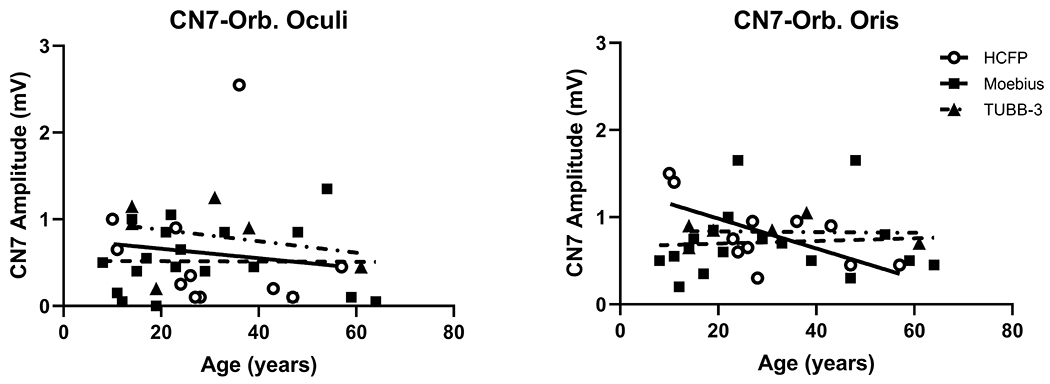

Figure 1.

Comparison of Age vs CN7 Amplitudes. Age in years (x-axis) at time of EDX study versus CN7 (y-axis) upper face (orbicularis oculi) and lower face (orbicularis oris) amplitudes for the MBS, n=19 (о, solid line), HCFP, n=11 (∎, dashed line), and CFEOM3a-TUBB, n=6 (▴, dot-dash line) groups.

Table 2.

Electrodiagnostic findings in 43 patients with Congenital Facial Weakness.

| Disorder | Facial Motor NCS (amplitude) | Blink Study (latencies) | Facial EMG | Limb NCS | Limb EMG | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OOC (mV) | OOR (mV) | R1 (ms) | IpsiR2 (ms) | ContraR2 (ms) | OOC/mentalis | |||

| Moebius syndrome (n=19) Median range (no response/total tests performed) | 0.45 0.0-1.4 (4/38) |

0.65 0.2-1.7 (3/38) |

9.9 0.0-13.4 (28/38) |

36.7 0.0-72.4 (24/38) |

37.8 0.0-73.6 (24/38) |

OOC: No MU (2), Rare MU (1), Neuro (2) Mentalis: Neuro (6),rare MU (1) Frontalis: No MU (1) |

Nl (9), SN (1), MN(1) | Nl (4), Neuro (2) |

| HCFP, undefined (n=11) Median range (no response/total bilateral tests performed) | 0.35 0.0-2.6 (1/22) |

0.85 0.2-2.7 (0/22) |

10.5 0.0-22.8 (6/22) |

35.6 0.0-48.9 (6/22) |

37.0 (0.0-63.4) (6/22) |

OOC: No MU (2), Neuro (4) Mentalis: No MU (1), Neuro (4), Nl (2) |

Nl (8) | Nl (7) |

| CFEOM 3A-TUBB3 (n=6) Median range (no response/total bilateral tests performed) | 0.78 0.5-1.3 (0/12) |

0.90 0.5--1.2 (0/12) |

11.8 (0.0-12.8 (6/12) |

37.8 0.0-54.2 (6/12) |

36.6 0.0-52.8 (6/12) |

OOC: Nl (2) Mentalis: Neuro (2) |

SMN(6) | Nl (1), Neuro (3) |

| Carey-Fineman-Ziter- MYMK (n=1) Median range (no response/total bilateral tests performed) | NA 0.0,0.0 (2/2) |

NA 0.1,0.1 (0/2) |

NR (2/2) |

NR (2/2) |

NR (2/2) |

OOC: ND Mentalis: Neuro (1) |

Nl(1) | Myo (1) |

| Facial palsy, ophthalmoplegia, arthrogryposis (n=3) Median range (no response/total bilateral tests performed) | 0 0.0-0.1 (3/6) |

0.3 0.3-0.7 (0/6) |

NA 0.0-10.6 (4/6) |

NA 0.0-34.2 (4/6) |

NA 0.0-30.9 (4/6) |

ND | MNC low (2) | Myo (2) |

| Indeterminate Muscle disorder (n=1) Median Range (no response/total bilateral tests performed) | NA 0.9,1.0 (0/2) |

NA 1.2,1.3 (0/2) |

NA 8.2,8.6 (0/2) |

NA 31.9,33.4 (0/2) |

NA 33.5,36.9 (0/2) |

OOC: Myo (1) | Nl(1) | Myo (1) |

| Myotonic dystrophy (n=1) Median range (no response/total bilateral tests performed) | NA 0.2,0.1 (0/2) |

NA 0.0,0.4 (0/12) |

NA 10.9,9.9 (0/2) |

NA 27.1,32.4 (0/2) |

NA 38.4,41.6 (0/2) |

ND | Nl(1) | Myt, Myo (1) |

| Hemifacial myohyperplasia (n=1) Median range (no response/total tests performed) | NA 2.1,0.6 (0/2) |

NA 2.4,1,2 (0/2) |

10.9,9.6 (0/2) |

31.4,26.5 (0/2) |

28.7,28.6 (0/2) |

OOC: ND Mentalis: Neuro (1) |

ND | ND |

| Total Median range (no response/total) | 0.5 0.0-2.6 (10/86) |

0.7 0.0-2.0 (3/86) |

10.4 0.0-16.8 (46/86 |

35.6 0.0-73.6 (42/86) |

35.8 0.0-73.6 (42/86) |

|||

HFCP - Hereditary Congenital Facial Paresis; CFEOM - Congenital fibrosis of extraocular muscles, CFEOM3A-TUBB3; CFZS – Carey-Fineman- Ziter syndrome, NCS – nerve conduction studies, EMG – electromyography, NCS – nerve conduction studies, EMG – electromyography, OOC-orbicularis oculi, OOR – orbicularis oris, IpR1 - ipsilateral R1 latency, IpR2 – ipsilateral R2 latency, ContraR2 – contralateral R2 latency, MU – motor unit, Neuro – neurogenic, defined as large amplitude, long-duration motor unit potentials with reduced recruitment, Myo – myopathic, defined as low amplitude, short-duration motor unit potentials with early recruitment, Myt – myotonia, Nl – Normal, SN – sensory neuropathy, MN – motor neuropathy, SMN – sensorimotor neuropathy, ND - not done, NA- not available NR- no response.

Eleven subjects had presumed HCFP (5 pedigrees, 2 autosomal dominant, 3 autosomal recessive) with clinical findings limited to CN7 weakness. Low amplitude CN7 MNCS responses (Figure1) were observed in most HCFP subjects (n=9) though 2 subjects only had abnormalities in the OOC. Blink responses were abnormal in only 5 HCFP subjects (Table 2). Abnormal NEMG studies with neurogenic changes with large motor unit potentials and decreased recruitment were limited to facial nerve-innervated muscles with normal NEMG in the limbs. Most subjects with normal blink and CN7 responses deferred the NEMG study.

Six subjects were diagnosed with CFEOM-3A-TUBB3 and harbored recurrent heterozygous missense mutations, (3 with c.1249G>C (p.Asp417His), 3 with c.785G>A (p.Arg262His)) (Figure 1, Table 2). All of these subjects had low amplitude CN7 MNCS responses, though 4 subjects had asymmetrical findings. Three subjects had absent blink responses and 1 subject only had abnormal R2(ipsi and contra) latencies. NCS of the limbs showed an axonal sensorimotor neuropathy with demyelinating features of slowed conduction velocity. The mean (with standard deviation) conduction velocity for the median motor nerve was 31.8±6.6 m/s and for the fibular nerve was 29.7±3.1 m/s. However, the NEMG in 3 subjects showed high amplitude motor unit potentials with reduced recruitment in the limb muscles consistent with the presence of an axonopathy.

Five subjects referred with the diagnosis of MBS had EDX evidence of a generalized muscle disorder (Table 2). One subject had genetically confirmed CFZ syndrome5 and had small motor unit potentials on NEMG, as well as absent CN7 MNCS and blink responses. This subject also had neurogenic changes with large motor unit potentials in the mentalis muscle related to a prior myoplasty. Three subjects had facial weakness, ophthalmoplegia, and arthrogryposis; two had NEMG studies with small motor unit potentials, low amplitude CN7 and limb MNCS responses and no blink responses. One subject had normal facial NCS and blink study with no NEMG study. These subjects had early infantile histories that were consistent with a fetal akinesia/congenital arthrogryposis syndrome and analysis of whole exome sequencing data did not reveal pathogenic variants for known congenital myopathy32, fetal akinesia syndrome33, or CMS genes34. Muscle biopsy in one of the subjects with arthrogryposis was non-diagnostic. Finally, one subject had an indeterminate muscle disorder with facial weakness and ophthalmoplegia. This subject had small motor unit potentials and early recruitment on NEMG with normal CN7 MNCS and blink responses. This subject self-identified as MBS syndrome and had facial weakness and absent horizontal and vertical eye movements that were consistent with a clinical diagnosis of CFEOM. In addition, she had mild weakness of neck flexors, arm abductors, elbow extensors, and great toe extensors. . She had a normal creatine kinase and aldolase, and no muscle biopsy had been performed.

One subject was diagnosed with myotonic dystrophy-Type 1 and had low amplitude CN7 MNCS responses, normal blink study with myotonic discharges and short duration motor unit potentials on NEMG. There was one subject with hemifacial myohyperplasia and no facial weakness. Electrodiagnostic testing revealed no CN7 abnormalities except for neurogenic changes with large motor unit potentials in the platysma related to several surgical procedures to reduce the unilateral myohyperplasia. No subjects with facioscapulohumeral or other myopathies were identified in this study.

Kruskal-Wallis test indicated that there were no significant differences among the MBS, HCFP, and CFEOM3A-TUBB3 groups for either CN7-OOC or CN7-OOR MNCS. Wilcoxon Signed-Rank test found that in the HCFP, the CN7-OOC amplitude was significantly lower than CN7-OOR (p=0.0391, median difference=0.35). In MBS, the median CN7-OOC amplitude was lower than the CN7-OOR but did not reach significance. CFEOM3A-TUBB3 had no significant differences between the upper and lower face. Spearman correlation showed there was no significant correlation between age and the CN7 amplitudes for any group, though CN7-OOR tended to decrease with age (r=−0.56, p=0.073) in HCFP.

DISCUSSION:

This study demonstrates the value of EDX evaluations in supporting the correct diagnosis underlying CFW. Subjects with HCFP, an isolated CN7 disorder, had abnormalities limited to CN7 including CN7 MNCS, blink studies, and NEMG findings in CN7 innervated muscles compatible with a neurogenic disorder. Subjects with MBS also had EDX abnormalities limited to CN7 MNCS and blink studies with the exception of two subjects who also had secondary abnormalities due to prior chemotherapy-induced neuropathy and a radiculopathy. In HCFP and to a lesser extent, MBS, there was relative sparing of the lower face, similar to what was reported in previous EDX studies in a pediatric MBS cohort 35. CFEOM3A-TUBB3 subjects had a combination of abnormal CN7, blink and sensorimotor neuropathies with low amplitude or absent responses and slow conduction velocities suggestive of an axonal process with demyelinating features, as previously described in this condition36, without prolonged latencies for the facial studies. The electrodiagnostic findings reflect the clinical presentation in CFEOM3A-TUBB3 of a nonprogressive CN7 neuropathy from birth with a progressive peripheral neuropathy. The severity of the peripheral neuropathy is based on specific mutations, with older subjects having a milder phenotype and a milder later-onset neuropathy, and younger subjects demonstrating a more severe phenotypic presentation of early onset neuropathy. The muscle disorders mostly showed low amplitude CN7 MNCS responses but not abnormal blink studies. NEMG of the limb muscles confirmed the diagnosis of a muscle disorder including myotonic dystrophy. Two subjects had normal facial nerve and blink studies, one subject with an indeterminate muscle disorder and another with hemifacial myohyperplasia. Importantly, EDX was able to differentiate the subject with an undefined myopathy from the congenital cranial dysinnervation disorder group, in agreement with the findings of our DTI-driven tensor-based morphometry analysis that showed no volumetric abnormality in the brainstem of this subject37.

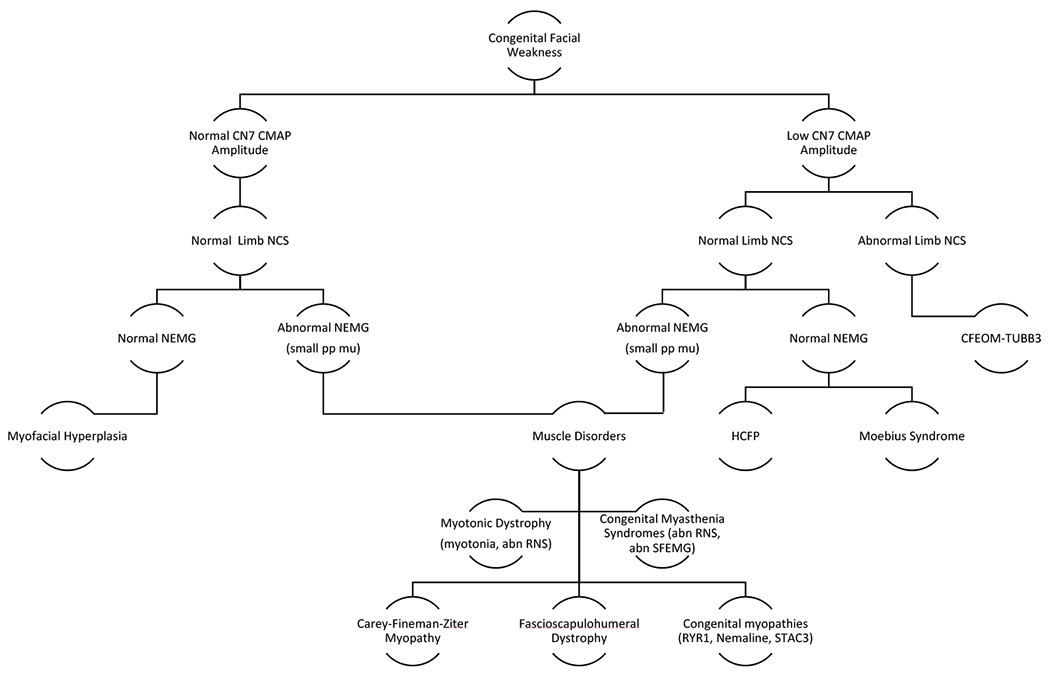

Testing CN7 MNCS established the degree and distribution of facial nerve weakness. The CN7 MNCS amplitudes do not appear to change with age with the exception on the decline in the CN7 OOR amplitude in the HCFP population. The numbers are limited but suggest that there may be mild CN7 deterioration with age in the HCFP group but not in Moebius or CFEOM3A-TUBB3 groups. The blink responses, when present, generally had normal latencies suggesting sparing of the V-VII internuclear pathways. There were a few prolonged blink latencies that were not associated with evidence of demyelination in the nerves of the limbs. An incidental finding in this study is that CN7 motor amplitudes greater than 1.0 mV will produce a reliable blink response. As the amplitude decreases, the ability to obtain a blink response becomes more variable. CN7 amplitudes less than 0.5 mV do not have a recordable blink response. Peripheral MNCS and SNCS were useful to confirm the presence of a generalized neuropathic disorder, such as in CFEOM3A-TUBB3, and would be useful to follow the disease progression in this disorder. NEMG of the limbs were important to diagnose if the facial weakness was associated with a muscle or generalized motor neuron disorder. NEMG of facial muscles was less useful than NEMG of limb muscles to diagnose generalized muscle or motor neuron disorders because of the frequency of facial surgery or severe atrophy of the facial muscles. In this study, we found that an algorithm of using a CN7 facial NCS, limb NCS, and NEMG was useful in differentiating the etiologies of CFW (Figure 2). The blink studies were less consistently present, so were not used in the algorithm.

Figure 2.

Algorithm for Electrodiagnostic Testing of Congenital Facial Weakness. Serial testing of Facial NCS, Limb NCS, NEMG, and possible RNS and SFEMG. (Abbreviations: CN7 – cranial nerve 7, CMAP – compound muscle action potential, NCS – nerve conduction studies, EMG – electromyography, small pp mu – small polyphasic motor unit potentials, RNS – repetitive nerve stimulation, SFEMG – single fiber EMG, HCFP – Hereditary Congenital Facial Paresis, Ryr – Ryanodine)

This study did not include more common neuromuscular disorders associated with CFW such as facioscapulohumeral dystrophy, congenital myasthenic syndromes, or more cases of myotonic dystrophy that can be identified by distinct clinical features and more widely available genetic testing. Additional EDX studies, such as repetitive nerve stimulation, jitter, and more extensive EMG studies, may also be important for diagnosing neuromuscular disorders, and may further guide testing decisions and genetic counseling. For clinicians who perform EDX, this study shows the value of performing a combination of CN7 and limb NCS and a limited number of NEMG studies to refine the diagnosis of facial weakness.

Acknowledgments including sources of support:

This study was supported by the Intramural Research Programs of National Institutes of Neurological Disorders and Stroke and Human Genome Research Institute. Grant support – U01HD079068 NICHD (EWJ, IM, ECE, Moebius Syndrome Collaborative Research Group); 1U54HD090255 NICHD (ECE, Boston Children’s Hospital Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities Research Center); Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Chevy Chase, MD 20815, USA. (ECE), and Moebius Syndrome Foundation. This work is in collaboration with the Moebius Syndrome Collaborative Research consortium (see below).

Abbreviations:

- CCDD

Congenital cranial dysinnervation disorders

- CN

Cranial nerve

- CN7-OOC

Cranial nerve 7-orbicularis oculi

- CN7-OOR

Cranial nerve 7-orbicularis oris

- CFEOM

Congenital fibrosis of extraocular muscles

- CFW

Congenital facial weakness

- EDX

electrodiagnostic

- HCFP

Hereditary Congenital Facial Paresis

- MBS

Moebius syndrome

- MNCS

Motor nerve conduction studies

- ms

Milliseconds

- m/s

Meters/second

- NEMG

Needle electromyography

- SNCS

Sensory nerve conduction studies

Moebius Syndrome Collaborative Research consortium:

1. Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York City, New York, USA—group

Monica Erazo1,2, Tamiesha Frempong3, Ke Hao1,4, Ethylin Wang Jabs1,5,6, Thomas P. Naidich6,7, Janet C. Rucker8,9, Bryn D. Webb1,6, and Zhongyang Zhang1,4.

1Department of Genetics and Genomic Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York

2Department of Neuroscience and Physiology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, New York (current affiliation)

3Department of Ophthalmology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York

4Icahn Institute for Data Science and Genomic Technology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York

5Cell, Developmental and Regenerative Biology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York

6Pediatrics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York

7Departments of Radiology, Neurosurgery, and Pediatrics, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York

8 Department of Neurology, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, New York

9Department of Neurology, New York University Grossman School of Medicine, New York, New York

2. Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA—group

Brenda J. Barry1,2,3,4, Wai-Man Chan1,4, Silvio Alessandro DiGioia1,2,3, Elizabeth Engle1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8, David G.Hunter6,7, Julie Jurgens1,2,3 Arthur Lee1,2,3, Sarah E. MacKinnon6, Caroline Robson9, and Matthew Rose1,5,2,8,10, and Alan Tenney1,2,3.

1Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA

2F.M. Kirby Neurobiology Center, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA

3Department of Neurology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

4Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Chevy Chase, MD

5Department of Pathology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA

6Department of Ophthalmology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA

7Department of Ophthalmology, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

8Medical Genetics Training Program, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

9Department of Radiology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA

10Department of Pathology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA

3. National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD—Group

Barbara B. Biesecker1, Lori L. Bonnycastle2, Carmen C. Brewer3, Brian P. Brooks4, John A. Butman5, Wade W. Chien3, Peter S. Chines2, Francis S. Collins2,6, Flavia Facio2, Kathleen Farrell7, Edmond J. FitzGibbon4, Andrea L. Gropman8, Elizabeth Hutchinson9, Mina S. Jain7, Kelly A. King3, Tanya J. Lehky10, Janice Lee11, Denise K. Liberton11, Irini Manoli2, Narisu Narisu2, Scott M. Paul7, Carlo Pierpaoli9, Neda Sadeghi9, Joseph Snow12, Beth Solomon7, Angela Summer12, Amy J. Swift2, Camilo Toro13, Audrey Thurm14, Carol Van Ryzin2 and Chris K. Zalewski3.

1Social and Behavioral Research Branch, National Human Genome Research Institute, Bethesda, MD

2Medical Genomics and Metabolic Genetics Branch, National Human Genome Research Institute, Bethesda, MD

3Audiology Unit, Otolaryngology Branch, National Institute of Deafness and other Communications Disorders, Bethesda, MD

4Ophthalmic Genetics & Visual Function Branch, National Eye Institute, Bethesda, MD

5Radiology and Imaging Sciences, Clinical Research Center, Bethesda, MD

6Office of the Director, National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD

7Rehabilitation Medicine Department, Clinical Research Center, Bethesda, MD

8George Washington University and Children’s National Medical Center, Washington, DC

9Quantitative Medical Imaging Section, National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering, Bethesda, MD

10Electromyography Section, National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, Bethesda, MD

11Office of the Clinical Director, National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research, Bethesda, MD

12Office of the Clinical Director, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD

13NIH Undiagnosed Diseases Program, Common Fund, National Human Genome Research Institute, Bethesda, MD

14Pediatrics and Developmental Neuroscience Branch, National Institute of Mental Health, Bethesda, MD

Footnotes

Ethical Statement: “We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.”

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to report.

Contributor Information

TANYA LEHKY, EMG Section, NINDS, NIH, Bethesda, MD.

REVERSA JOSEPH, EMG Section, NINDS, NIH, Bethesda, MD, Chalmers P Wylie Veterans Administration Columbus, Ohio.

CAMILO TORO, Undiagnosed Disease Program, OCD, NHGRI, NIH, Bethesda, MD.

TIANXIA WU, Clinical Trials Unit, NINDS, NIH, Bethesda, MD.

CAROL VAN RYZIN, Medical Genomics and Metabolic Genetics Branch, NHGRI, NIH, Bethesda, MD.

ANDREA GROPMAN, Neurodevelopmental Pediatrics and Neurogenetics, Children’s National Medical Center, 111 Michigan Avenue NW, Washington, D.C., 20010.

FLAVIA M. FACIO, Medical Genomics and Metabolic Genetics Branch, NHGRI, NIH, Bethesda, MD.

BRYN D. WEBB, Department of Genetic and Genomic Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 1425 Madison Avenue, NYC, NY 10029.

ETHYLIN WANG JABS, Department of Genetics and Genomic Sciences, Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, 1425 Madison Avenue, NYC, NY 10029.

BRENDA S. BARRY, Department of Neurology, Boston Children’s Hospital, Boston, MA 02115. Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Chevy Chase, MD 20815.

ELIZABETH C. ENGLE, Departments of Neurology and Ophthalmology, Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115. Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Chevy Chase, MD 20815.

FRANCIS S. COLLINS, Office of the Director & Medical Genomics and Metabolic Genetics Branch, IMOD, NIH, Bethesda, MD.

IRINI MANOLI, Medical Genomics and Metabolic Genetics Branch, NHGRI, NIH, Bethesda, MD.

References

- 1.Verzijl HT, van der Zwaag B, Lammens M, ten Donkelaar HJ, Padberg GW. The neuropathology of hereditary congenital facial palsy vs Mobius syndrome. Neurology 2005;64:649–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.MacKinnon S, Oystreck DT, Andrews C, Chan WM, Hunter DG, Engle EC. Diagnostic distinctions and genetic analysis of patients diagnosed with moebius syndrome. Ophthalmology 2014;121:1461–1468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rucker JC, Webb BD, Frempong T, Gaspar H, Naidich TP, Jabs EW. Characterization of ocular motor deficits in congenital facial weakness: Moebius and related syndromes. Brain 2014;137:1068–1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Whitman MC, Engle EC. Ocular congenital cranial dysinnervation disorders (CCDDs): insights into axon growth and guidance. Hum Mol Genet 2017;26:R37–R44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Di Gioia SA, Connors S, Matsunami N, et al. A defect in myoblast fusion underlies Carey-Fineman-Ziter syndrome. Nat Commun 2017;8:16077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Traboulsi EI. Congenital cranial dysinnervation disorders and more. J AAPOS 2007;11:215–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bosley TM, Abu-Amero KK, Oystreck DT. Congenital cranial dysinnervation disorders: a concept in evolution. Curr Opin Ophthalmol 2013;24:398–406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Engle EC. Oculomotility disorders arising from disruptions in brainstem motor neuron development. Arch Neurol 2007;64:633–637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Miller G Neurological disorders. The mystery of the missing smile. Science 2007;316:826–827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Verzijl HT, van der Zwaag B, Cruysberg JR, Padberg GW. Mobius syndrome redefined: a syndrome of rhombencephalic maldevelopment. Neurology 2003;61:327–333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carta A, Mora P, Neri A, Favilla S, Sadun AA. Ophthalmologic and systemic features in mobius syndrome an italian case series. Ophthalmology 2011;118:1518–1523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stromland K, Sjogreen L, Miller M, et al. Mobius sequence--a Swedish multidiscipline study. Eur J Paediatr Neurol 2002;6:35–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lopez de Lara D, Cruz-Rojo J, Sanchez del Pozo J, Gallego Gomez ME, Lledo Valera G. Moebius-Poland syndrome and hypogonadotropic hypogonadism. Eur J Pediatr 2008;167:353–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Briegel W, Schimek M, Kamp-Becker I. Moebius sequence and autism spectrum disorders--less frequently associated than formerly thought. Res Dev Disabil 2010;31:1462–1466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mohammad SA, Abdelaziz TT, Gadelhak MI, Afifi HH, Abdel-Salam GMH. Magnetic resonance imaging of developmental facial paresis: a spectrum of complex anomalies. Neuroradiology 2018;60:1053–1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Webb BD, Shaaban S, Gaspar H, et al. HOXB1 founder mutation in humans recapitulates the phenotype of Hoxb1−/− mice. Am J Hum Genet 2012;91:171–179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michielse CB, Bhat M, Brady A, et al. Refinement of the locus for hereditary congenital facial palsy on chromosome 3q21 in two unrelated families and screening of positional candidate genes. Eur J Hum Genet 2006;14:1306–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Verzijl HT, van den Helm B, Veldman B, et al. A second gene for autosomal dominant Mobius syndrome is localized to chromosome 10q, in a Dutch family. Am J Hum Genet 1999;65:752–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tischfield MA, Baris HN, Wu C, et al. Human TUBB3 mutations perturb microtubule dynamics, kinesin interactions, and axon guidance. Cell 2010;140:74–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chew S, Balasubramanian R, Chan WM, et al. A novel syndrome caused by the E410K amino acid substitution in the neuronal beta-tubulin isotype 3. Brain 2013;136:522–535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grant PE, Im K, Ahtam B, et al. Altered White Matter Organization in the TUBB3 E410K Syndrome. Cereb Cortex 2019;29:3561–3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tomas-Roca L, Tsaalbi-Shtylik A, Jansen JG, et al. De novo mutations in PLXND1 and REV3L cause Mobius syndrome. Nat Commun 2015;6:7199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolski HK, Leonard NJ, Lemmers RJ, Bamforth JS. Atypical facet of Mobius syndrome: association with facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Muscle Nerve 2008;37:526–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xue Y, Magoulas PL, Wirthlin JO, Buchanan EP. Craniofacial Manifestations in Severe Nemaline Myopathy. J Craniofac Surg 2017;28:e258–e260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Abath Neto O, Moreno CAM, Malfatti E, et al. Common and variable clinical, histological, and imaging findings of recessive RYR1-related centronuclear myopathy patients. Neuromuscul Disord 2017;27:975–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Telegrafi A, Webb BD, Robbins SM, et al. Identification of STAC3 variants in non-Native American families with overlapping features of Carey-Fineman-Ziter syndrome and Moebius syndrome. Am J Med Genet A 2017;173:2763–2771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee S, Sze R, Murakami C, Gruss J, Cunningham M. Hemifacial myohyperplasia: description of a new syndrome. Am J Med Genet 2001;103:326–333. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bergman JE, Janssen N, Hoefsloot LH, Jongmans MC, Hofstra RM, van Ravenswaaij-Arts CM. CHD7 mutations and CHARGE syndrome: the clinical implications of an expanding phenotype. J Med Genet 2011;48:334–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lipson AH, Gillerot Y, Tannenberg AE, Giurgea S. Two cases of maternal antenatal splenic rupture and hypotension associated with Moebius syndrome and cerebral palsy in offspring. Further evidence for a utero placental vascular aetiology for the Moebius syndrome and some cases of cerebral palsy. Eur J Pediatr 1996;155:800–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Marques-Dias MJ, Gonzalez CH, Rosemberg S. Mobius sequence in children exposed in utero to misoprostol: neuropathological study of three cases. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 2003;67:1002–1007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Preston DC & Shapiro B. Electromyography and Neuromuscular Disorders: Clinical-Electrophysiological Correlations, 3rd Edition ed: Elsevier, Inc., 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 32.North KN, Wang CH, Clarke N, et al. Approach to the diagnosis of congenital myopathies. Neuromuscul Disord 2014;24:97–116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pergande M, Motameny S, Ozdemir O, et al. The genomic and clinical landscape of fetal akinesia. Genet Med 2020;22:511–523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Abicht A, Dusl M, Gallenmuller C, et al. Congenital myasthenic syndromes: achievements and limitations of phenotype-guided gene-after-gene sequencing in diagnostic practice: a study of 680 patients. Hum Mutat 2012;33:1474–1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Renault F, Flores-Guevara R, Sergent B, et al. Pathogenesis of cranial neuropathies in Moebius syndrome: Electrodiagnostic orofacial studies. Muscle Nerve 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tischfield MA, Engle EC. Distinct alpha- and beta-tubulin isotypes are required for the positioning, differentiation and survival of neurons: new support for the ‘multi-tubulin’ hypothesis. Biosci Rep 2010;30:319–330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sadeghi NHE, Van Ryzin C, FitzGibbon EJ, Butman JA, Webb BD, Facio F, Brooks BP, Collins FS, Jabs EW, Engle EC, Manoli I, Pierpaoli C, Moebius Syndrome Research consortium. Brain phenotyping in Moebius syndrome and other congenital facial weakness disorders by diffusion MRI morphometry. Brain Communications 2020:1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]