Abstract

OBJECTIVES:

To review the diagnostic performance of contemporary imaging modalities for determining local disease extent and nodal metastasis in patients with newly-diagnosed cervical cancer.

METHODS:

Pubmed and Embase databases were searched for studies published from 2000 to 2019 that used ultrasound (US), CT, MRI, and/or PET for evaluating various aspects of local extent and nodal metastasis in patients with newly-diagnosed cervical cancer. Sensitivities and specificities from the studies were meta-analytically pooled using bivariate and hierarchical modelling.

RESULTS:

Of 1,311 studies identified in the search, 115 studies with 13,999 patients were included. MRI was the most extensively studied modality (MRI, CT, US, and PET were evaluated in 78, 12, 9 and 43 studies, respectively). Pooled sensitivities and specificities of MRI for assessing all aspects of local extent ranged between 0.71–0.88 and 0.86–0.95, respectively. In assessing parametrial invasion (PMI), US demonstrated pooled sensitivity and specificity of 0.67 and 0.94, respectively—performance levels comparable to those found for MRI. MRI, CT and PET performed comparably for assessing nodal metastasis, with low sensitivity (0.29–0.69) but high specificity (0.88–0.98), even when stratified to anatomical location (pelvic or paraaortic) and level of analysis (per patient vs. per site).

CONCLUSIONS:

MRI is the method of choice for assessing any aspect of local extent, but where not available, US could be of value, particularly for assessing PMI. CT, MRI and PET all have high specificity but poor sensitivity for detection of lymph node metastases.

Keywords: Uterine cervical neoplasms, Neoplasm staging, Ultrasonography, Magnetic resonance imaging, Positron-emission tomography

Introduction

Cervical cancer is the fourth most common cancer worldwide, with an estimated 570,000 new cases having occurred in 2018 [1]. That year, cervical cancer was linked to 311,000 deaths, most of them in low- and middle-income countries, where the disease is most prevalent and more often diagnosed at advanced stages [1–4]. The anatomic extent of disease at diagnosis significantly affects prognosis and is used to tailor the initial treatment strategy. Small (<4-cm) tumors confined to the cervix are treated surgically, while “advanced” disease (e.g., extending to the parametrial tissues and beyond) is treated with concurrent chemoradiation [5].

The staging system most commonly used for cervical cancer is that of the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO). In the updated 2018 guidelines, FIGO for the first time recommended using “any available” imaging modality for staging cervical cancer, reflecting increasing recognition of the value of imaging for disease management [6].

State-of-the-art imaging technologies, such as magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and positron emission tomography (PET), have repeatedly been shown to aid in cervical cancer staging but have historically had limited availability, especially in low-income countries. Though many studies have reported on the roles of these technologies [7–9], a lesser number have reported on ultrasound (US) and computed tomography (CT)-modalities that are more widely available in low-income countries [10]. While a direct comparison of the four imaging modalities in a single patient population is not feasible, the purpose of this study was to systematically review the diagnostic performance of all four of them for determining local disease extent and nodal metastasis in patients with treatment-naive cervical cancer of any clinical stage.

Materials and methods

Literature search

This study was performed according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines [11]. Pubmed and Embase databases were systematically searched for original articles published from January 1, 2000 to December 5, 2019 assessing the diagnostic performance of US, CT, MRI, and PET in determining local extent and nodal metastasis in patients with treatment-naive cervical cancer using a search query shown in supplementary data. The references in the eligible studies found were then screened for additional potentially eligible studies. The search was limited to studies published in English.

Inclusion criteria

Inclusion was based on the PICOS criteria [11]: (1) patients (P), newly-diagnosed cervical cancer; (2) index test (I), US, CT, MRI, or PET; (3) comparator (C), surgico-pathological findings as reference standard, with the exception of bladder or rectal invasion, for which cystoscopy and proctoscopy with or without biopsy could be used; (4) outcomes (O), 2 × 2 contingency table regarding sensitivity and specificity of each imaging modality could be reconstructed for various endpoints of local extent and nodal metastases; and (5) study design (S), randomized controlled trials (RCT), quasi-RCTs, and prospectively or retrospectively performed observational studies.

Exclusion criteria

Studies meeting any of the following criteria were excluded: (1) published before 1 January 2000; (2) <10 patients; (3) publication type other than original research article (i.e., conference abstract, case report, etc.); (4) patients with recurrent tumors or who received neoadjuvant treatment; (5) “investigational” techniques, including texture analysis, radiomics, intravoxel incoherent motion (IVIM) MRI, or others not representative of current daily practice; (6) insufficient data for reconstructing 2 × 2 contingency tables; and (7) substantial overlap in patient population. When publications’ patient populations overlapped substantially, only the study with the largest population was used.

One investigator (S.W.) performed the initial systematic search, which was double-checked by another investigator (H.A.V.).

Data extraction and quality assessment

We extracted the following information from the studies using a standardized form: first author, publication year, institution, duration of patient enrollment; study design (whether prospective, multicenter, consecutive enrollment or not); number of patients; FIGO stages; imaging modality used (US, CT, MRI, or PET); evaluated endpoint (e.g., parametrial invasion [PMI], vaginal invasion, bladder invasion, pelvic nodal metastasis); level of analysis (e.g., per patient vs. per site [stratified to side/region/node]). Methodological quality was evaluated based on the Quality Assessment of Diagnostic Accuracy Studies-2 (QUADAS-2) tool at the study level [12]. One reviewer (S.W.) extracted these data and performed quality assessment, and the results were double checked by another (H.A.V.).

Data synthesis and analysis

Reconstructed raw data in the form of 2 × 2 contingency tables were used to calculate sensitivity and specificity values from each study. When diagnostic performance values of multiple imaging criteria/techniques were reported within a single study, for each imaging modality and endpoint, the one most widely available and clinically feasible was used to represent that study. For example, if a study compared MRI with pelvic phased-array coils to MRI with endovaginal coils for determining PMI, the former was used; if a study reported mean apparent diffusion coefficient (ADC) and minimum ADC values for detecting metastatic lymph nodes, we used the former. Furthermore, when multiple readers’ diagnostic performance values were given, we used the average value across all readers.

Pooled sensitivity and specificity were calculated using hierarchical logistic regression modelling including bivariate modelling and hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic (HSROC) modelling [13]. We only meta-analytically pooled endpoints that had at least four available studies, as pooling small numbers of studies has been recognized as misleading [14]. HSROC curves with 95% confidence and prediction regions were plotted. Publication bias was tested for analyses including more than 10 studies and was considered present if visually present on Deeks’ funnel plot or when p-values for Deeks’ asymmetry test were <0.1 [15].

Heterogeneity between the studies was assessed using Cochran’s Q-test and Higgins I2 test and was considered present if p-value for the Q-test was <0.05. The degree of heterogeneity was categorized using the inconsistency index (I2) as follows: 0–40%, might not be important; 30–60%, moderate heterogeneity; 50–90%, substantial heterogeneity; and 75–100%, considerable heterogeneity [16]. For PMI and nodal metastasis, we additionally reported diagnostic performance for each combination of (1) level of analysis and (2) anatomical location (e.g., PMI per patient and PMI per side [right vs left], pelvic lymph node metastasis per patient, paraaortic lymph node metastasis per region, etc.).

For statistical analysis, the ‘midas’ and ‘metandi’ modules in Stata 13.0 were used (StataCorp LP) and the ‘mada’ package in R software version 3.2.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing).

Results

Lieaure each

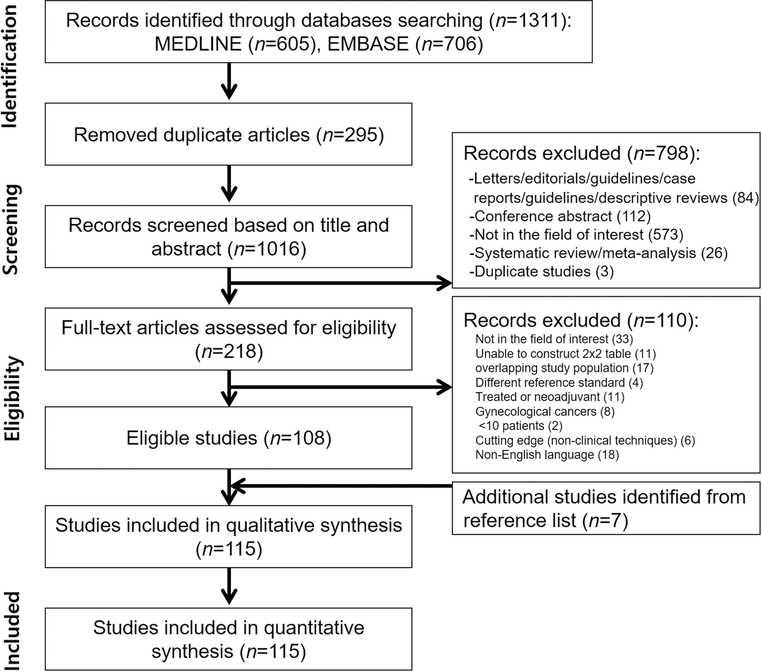

Figure 1 presents a flowchart of the study selection process. Ultimately, 115 articles reporting on a total of 13,999 patients were included (Supplementary material). US was assessed in 9 studies, CT in 12, MRI in 78, and PET in 43.

Figure 1.

Flowchart showing study selection process.

Study characteristics

Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the individual studies. In short, 44 studies were prospective and 71 were retrospective. Thirteen were multi-center and 102 were single-institution studies; 81, 29 and 5 studies were performed in high-, upper middle-, and lower middle-income countries, respectively, as defined by the World Bank. The numbers of patients ranged from 14 to 1,347. The distribution of patients’ FIGO stages was heterogeneous: 46 studies only included early stages (≤IIA), 2 only included advanced stages (≥IIB), while 67 included patients with both early (≤IIA) and advanced (stage ≥IIB) disease. Evaluated endpoints were PMI, deep stromal invasion, internal cervical os invasion, vaginal invasion, bladder invasion, rectal invasion, and lymph node metastases, which were categorized as pelvic, paraaortic, or both.

Table 1.

Study Characteristics

| Author, year* | Institution | Period | Country | Prospective | No. of patients | FIGO stages | Imaging modality | Endpoint |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anner P et al, 2018 | Medical University of Vienna | January 2008 - July 2011 | Austria | No | 27 | NR | MRI, PET | PLN |

| Atri M et al, 2016 | Multicenter | September 2007 - June 2013 | US, Canada | Yes | 153 | IB2 - IVA | CT, PET | PLN, PALN, PLN+PALN |

| Atri M et al, 2015 | Multicenter | September 2007 - June 2013 | US, Canada | Yes | 33 | IB2 - IVA | MRI | PLN, PALN, PLN+PALN |

| Bhosale PR et al, 2016 | The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center | NR | US, Canada | No | 79 | IA - IB2 | MRI | Internal os, PLN |

| Bipat et al, 2011 | Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam | January 2003 - December 2007 | The Netherlands | No | 27 | 1B1 | MRI | Internal os, PLN |

| Bleker SM et al, 2013 | Academic Medical Centre, University of Amsterdam | January 2003 - January 2011 | The Netherlands | No | 203 | IB - IIA | MRI | PMI |

| Bourgioti C et al, 2014 | Aretaieion Hospital | September 2008 - June 2013 | Greece | Yes | 21 | IA - IB1 | MRI | Internal os, deep stromal invasion |

| Brocker KA et al, 2014 | University of Heidelberg Medical School | February 2007 - September 2010 | Germany | Yes | 44 | IA1 - IV | MRI | PMI |

| Byun JM et al, 2013 | Busan Paik Hospital | January 2009 - December 2009 | Korea | Yes | 24 | IA - IIB | US, MRI | PMI, vagina |

| Canaz E et al, 2017 | Istanbul Kanuni Sultan Suleyman Training and Research Hospital | 2001 - 2015 | Turkey | No | 76 | IB1 - IIA2 | US, MRI | PMI |

| Chen YB et al, 2011 (1) | Fujian Medical University Teaching Hospital | September 2006 - March 2009 | China | Yes | 26 | NR | MRI | PLN-r |

| Chen YB et al, 2011 (2) | Fujian Medical University Teaching Hospital | September 2006 - March 2009 | China | Yes | 61 | IB - IIB | MRI | PLN-n |

| Choi HJ et al, 2006 | National Cancer Center, Korea | October 2001 - October 2004 | Korea | No | 55 | IB - IVA | MRI | PLN+PALN-r, PLN+PALN-n |

| Choi SH et al, 2004 | Seoul National University College of Medicine | January 2000 - June 2003 | Korea | Yes | 115 | NR | MRI | PMI-s, vagina, PLN |

| Chou HH et al, 2010 | Chang Gung Memorial Hospital | April 2002 - March 2008 | Taiwan | No | 83 | IB1 - IIB | MRI, PET | PLN+PALN-r, PLN-r, PALN-r |

| Chung HH et al, 2009 | Seoul National University College of Medicine | January 2003 - July 2007 | Korea | No | 34 | IA2 - IIB | PET | PLN-r |

| Chung HH et al, 2010 | Seoul National University College of Medicine | January 2004 - December 2008 | Korea | No | 83 | IB1 - IIB | MRI, PET | PLN |

| Chung HH et al, 2007 | Seoul National University College of Medicine | January 2004 - May 2006 | Korea | No | 119 | IA1 - IIB | MRI | PMI, PLN+PALN, PLN+PALN-r |

| Crivellaro C et al, 2012 | University of Milano Bicocca | January 2005 - December 2010 | Italy | Yes | 69 | IB1 - IIA | PET | PLN |

| De Cuypere M et al, 2019 | Multicenter | March 2010 - December 2016 | Belgium, Spain | No | 168 | IB2 - IVA | PET | PALN |

| deSouza NM et al, 2006 | Hammersmith Hospital | February 1993 - January 2002 | UK | No | 119 | IA - IIB | MRI | PMI |

| Dong Y et al, 2014 | Shanghai First People’s Hospital Affiliated to Shanghai Jiaotong University | September 2009 - November 2012 | China | No | 63 | IA - IIA | PET | Vagina, PLN |

| Downey K et al, 2016 | The Institute of Cancer Research and Royal Marsden NHS Foundation Trust | May 2013 - August 2014 | United Kingdom | Yes | 25 | IA/IB | MRI | PMI-s |

| Driscoll DO et al, 2015 | St. James Hospital, Ireland | January 2009 - September 2011 | Ireland | No | 47 | IA - IB1 | PET | PLN+PALN |

| Duan X et al, 2016 | Sun Yat-Sen Memorial Hospital | February 2006 - July 2014 | China | No | 20 | NR | MRI | PMI |

| Epstein E et al, 2013 | Multicenter | September 2007 - April 2010 | Sweden, Italy, Lithuania, Belgium, Czech Republic | Yes | 182 | IA2 - IIA | US, MRI | PMI, deep stromal invasion |

| Fischerova D et al, 2008 | General Teaching Hospital, Charles University | January 2004 - February 2006 | Czech Republic | Yes | 95 | IA1 - IIA | US, MRI | PMI |

| Fujiwara K et al, 2000 | Kawasaki Medical School | August 1997 - December 1998 | Japan | Yes | 75 | IA - IB | MRI | Deep stromal invasion |

| Ghi T et al, 2007 | Universit’a degli Studi di Bologna | January 2005 - May 2006 | Italy | Yes | 14 | NR | US | PMI-s, rectum, bladder |

| Goyal BK et al, 2010 | Army Hospital (Research & Referral), New Delhi | May 2007 - November 2009 | India | No | 80 | IB1 - IIA | PET | PLN+PALN |

| Grueneisen J et al, 2015 | University Hospital Essen | NR | Germany | Yes | 27 | NR | PET | PMI, vagina, bladder/rectum, PLN+PALN |

| Hancke K et al, 2008 | University of Ulm | 1992 - 2003 | Germany | No | 109 | NR | CT, MRI | PMI |

| Hansen MA et al, 2000 | Copenhagen University Hospital | June 1993 - June 1996 | Denmark | No | 61 | IB - IIB | MRI | PMI |

| He F et al, 2018 | The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanchang University | 2005 - 2012 | China | No | 1347 | IB1 - IIA2 | MRI | PMI |

| Hertel H et al, 2002 | Friedrich-Schiller-University of Jena | April 1995 - March 2001 | Germany | No | 109 | IB2 - IVB | CT, MRI | Bladder, rectum, PLN, PALN |

| Hori M et al, 2009 | Osaka University Graduate School of Medicine | November 2006 - October 2007 | Japan | No | 31 | IA1 - IIB | MRI | PMI, vagina, PLN |

| Hricak H et al, 2005 | Multicenter | March 2000 - November 2002 | US | Yes | 172 | IA - IVA | CT, MRI | PLN+PALN |

| Jena A et al, 2005 | Rajiv Gandhi Cancer Institute & Research Centre | 1999 - 2002 | India | No | 105 | NR | MRI | PMI |

| Jeong BK et al, 2012 | Samsung Medical Center | January 1997 - December 2010 | Korea | No | 769 | IA - IVB | MRI, CT | Bladder, rectum |

| Jung DC et al, 2010 | Seoul National University Hospital | 2006 - 2009 | Korea | No | 167 | IA2 - IIA | MRI | PMI |

| Jung W et al, 2017 | Ewha Womans University Mokdong Hospital | January 2009 - March 2015 | Korea | No | 114 | IA1 - IIB | CT, MRI, PET | PLN-s |

| Kan Y et al, 2019 | Dalian Medical University, Cancer Hospital of China Medical University, Liaoning Cancer Hospital & Institute | March 2014 - October 2017 | China | No | 143 | IA2 - IIB | MRI | PLN |

| Kang S et al, 2013 | Asan Medical Center | January 2001 - January 2010 | Korea | No | 699 | IB1 - IIA | MRI | PLN+PALN-r |

| Kido A et al, 2014 | Graduate School of Medicine, Kyoto University | 1998 - 2012 | Japan | No | 67 | IA - IVA | MRI | PMI, vagina |

| Kim M et al, 2017 | Seoul National University Bundang Hospital | 2003 - 2014 | Korea | No | 215 | IB1 - IIA2 | MRI | PMI |

| Kim MH et al, 2011 | Asan Medical Center | January 2005 - March 2009 | Korea | No | 143 | NR | MRI | PLN-n |

| Kim SH et al, 2012 | Keimyung University, Dongsan Hospital | January 2005 - January 2010 | Korea | No | 200 | IB - IIA | MRI | PLN+PALN, PLN+PALN-r |

| Kim SK et al, 2009 | Asan Medical Center | October 2001 - December 2007 | Korea | No | 79 | IB - IVA | PET | PLN+PALN, PLN+PALN-r |

| Kim WY et al, 2011 | Myongji Hospital, Kwandong University School of Medicine | January 2005 - December 2009 | Korea | No | 257 | NR | MRI | Bladder/rectum |

| Kitajima K et al, 2014 | Kobe University Graduate School of Medicine | December 2011 - February 2013 | Japan | No | 30 | IB1 - IV | MR, PET | PMI, vagina, bladder, PLN |

| Klerkx WM et al, 2012 | Multicenter | 2006 - 2009 | The Netherlands | Yes | 68 | IA2 - IIB | MRI | PLN-r |

| Kong TW et al, 2016 | Ajou University Hospital | February 2000 - March 2015 | Korea | No | 298 | IB | MRI | PMI |

| Lakhman Y et al, 2013 | MSKCC | November 2001 - January 2011 | US | No | 62 | IB1 | MRI | Deep stromal invasion |

| Lam WW et al, 2000 | Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin | December 1995 - January 1998 | Hong Kong | Yes | 38 | I | MRI | PMI-s |

| Leblanc E et al, 2011 | Multicenter | 2004 - 2008 | France | No | 125 | IB2 - IVA | PET | PALN |

| Li K et al, 2019 | Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University | January 2013 - June 2017 | China | No | 394 | IA - IIA | PET | PLN |

| Lin AJ et al, 2019 | Washington University School of Medicine | March 1999 - February 2018 | US | Yes | 212 | IB1 - IB2 | PET | PLN, PALN |

| Lin WC et al, 2003 | China Medical College Hospital | NR | China | Yes | 50 | IIB - IVA | PET | PALN |

| Liu Y et al, 2011 | Tianjin Medical University Cancer Institute and Hospital | October 2006 - January 2010 | China | Yes | 42 | IB - IIB | MRI | PLN |

| Loft A et al, 2007 | Copenhagen University Hospital | November 2002 - October 2005 | Denmark | Yes | 27 | IB1 - IVA | PET | PLN, PALN |

| Lv K et al, 2014 | Shandong Provincial Hospital affiliated to Shandong University | October 2009 - November 2011 | China | No | 87 | IA1 - IIB | MRI, PET | PLN+PALN, PLN+PALN-n |

| Ma X et al, 2017 | Kunshan Hospital Affiliated to Jiangsu University | May 2014 - June 2016 | China | Yes | 39 | IB1 - IV | US, MRI | PMI |

| Manfredi R et al, 2009 | University of Verona | NR | Italy | Yes | 53 | <IIB | MRI | Vagina, internal os, PLN+PALN |

| Mansour SM et al, 2017 | Kasr Al Ainy Hospital | March 2015 - September 2016 | Egypt | No | 50 | IB - IVB | MRI | PMI, PLN+PALN |

| Massad LS et al, 2000 | Cook County Hospital | July 1994 - July 1999 | US | No | 96 | IB2 - IVB | CT | Bladder |

| Mayoral et al, 2017 | Hospital Clinic, Barcelona | June 2011 - January 2013 | Spain | Yes | 17 | IA2 - IB1 | PET | PLN, PALN |

| Moloney F et al, 2016 | Cork University Hospital | January 2011 - December 2013 | Ireland | Yes | 33 | IB - IIA | US, MRI | PMI, deep stromal invasion |

| Monteil J et al, 2011 | University Hospital, Limoges | September 2004 - December 2007 | France | Yes | 40 | IA - IB1 | MRI, PET | PLN, PALN |

| Narayan K et al, 2001 | Peter MacCallum Cancer Institute | November 1998 - August 2000 | Australia | No | 27 | IB - IVB | MRI, PET | PLN, PALN |

| Nogami et al, 2015 | School of Medicine, Keio University | September 2012 - March 2014 | Japan | No | 70 | IA1 - IIB | PET | PLN+PALN, PLN+PALN-r |

| Palsdottir K et al, 2015 | Multicenter | December 2007 - October 2012 | Sweden | Yes | 104 | IA2 - IIB | US | PLN, deep stromal invasion |

| Papadia A et al, 2017 | University Hospital of Bern and University of Bern | December 2008-November 2016 | Switzerland | No | 60 | IA1 - IIA | PET | PLN+PALN |

| Park JJ et al, 2014 | Samsung Medical Center | January 2010 - December 2012 | Korea | No | 152 | IA - IIA | MRI | PMI |

| Park W et al, 2005 | Samsung Medical Center | 1997 - 2003 | Korea | No | 36 | 1B1 - IIA | MRI, PET | PMI, PLN, PLN-s |

| Perez-Medina T et al, 2013 | Multicenter | January 2009 - June 2012 | Spain | Yes | 52 | IB2 - IVA | PET | PALN |

| Postema S et al, 2000 | Leiden University Medical Center | NR | The Netherlands | No | 82 | IA - IV | MRI | PMI-s, bladder |

| Qu JR et al, 2018 | The Affiliated Cancer Hospital of Zhengzhou University | January 2010 - October 2014 | China | No | 192 | IB1 - IIA | MRI | PMI |

| Ramirez PT et al, 2011 | Multicenter | April 2004 - May 2009 | US | Yes | 60 | IB2 - IVA | PET | PALN |

| Reinhardt MJ et al, 2001 | University Hospital of Freiburg | 1995 - 1998 | Germany | Yes | 35 | IB - IIA | MRI, PET | PLN+PALN, PLN+PALN-r |

| Rizzo S et al, 2014 | European Institute of Oncology | 2006 - 2012 | Italy | No | 217 | IA1 - IIB | MRI | Deep stromal invasion, PLN |

| Roh HJ et al, 2018 | Asan Medical Center | January 2007 - December 2016 | Korea | No | 260 | IA2 - IIA | MRI | PMI |

| Roh JW et al, 2005 | National Cancer Center, Korea | May 2002 - August 2003 | Korea | Yes | 54 | IB - IVA | PET | PLN+PALN-r |

| Sahdev A et al, 2007 | St. Bartholomew’s Hospital | 1995 - 2005 | UK | No | 150 | ≤IB | MRI | PMI, internal os, PLN, PLN-n |

| Sandvik RM et al, 2011 | Glostrup Hospital | May 2006 - November 2007 | Denmark | No | 41 | IA - IVB | PET | PLN+PALN |

| Sarabhai T et al, 2018 | University Hospital Essen | NR | Germany | Yes | 53 | IB - IV | MRI, PET | PMI, vagina, bladder/rectum, PLN, PALN, PLN+PALN |

| Sharma DN et al, 2010 | All India Institute of Medical Sciences | 2003 - 2005 | India | No | 305 | IB - IVB | CT | Bladder |

| Sheu MH et al, 2001 | Veterans General Hospital-Taipei and School of Medicine | April 1996 - June 1999 | Taiwan | Yes | 41 | IA - IVA | MRI | PMI, vagina, PLN |

| Shin YR et al, 2013 | Seoul St. Mary’s Hospital | August 2009 - November 2010 | Korea | No | 45 | ≥IB | MRI | PMI, vagina, PLN |

| Shweel MA et al, 2012 | Minia University | February 2009 - August 2010 | Egypt | Yes | 30 | IB - IVA | MRI | PMI, vagina, bladder, rectum |

| Signorelli M et al, 2011 | Multicenter | January 2004 - December 2010 | Italy | Yes | 159 | IB1 - IIA | PET | PLN+PALN, PLN+PALN-r |

| Sironi S et al, 2006 | University of Milano Bicocca | January 2003 - August 2004 | Italy | Yes | 47 | IA1 - IB2 | PET | PLN, PLN-n |

| Song J et al, 2019 | The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University | January 2011 - December 2016 | China | No | 92 | IB - III | MRI | PLN-n |

| Song J et al, 2019 | The First Affiliated Hospital of Nanjing Medical University | January 2011 - December 2017 | China | No | 81 | IB - IIA | MRI | PMI |

| Sozzi G et al, 2019 | Multicenter | January 2013 - December 2018 | Italy | No | 79 | IA1 - IIB | US, MRI | PMI, vagina |

| Tanaka T et al, 2018 | Osaka Medical College | September 2013 - January 2016 | Japan | No | 48 | IA2 - IIA | PET | PLN-s |

| Vazquez-Vicente D et al, 2018 | Jiménez Díaz Foundation Hospital | 2009 - 2015 | Argentina, Spain | No | 59 | IB2 - IVA | CT | PALN |

| Vural GU et al, 2014 | Ankara Oncology Education and Research Hospital | NR | Turkey | No | 74 | IB - IVB | PET | PLN+PALN |

| Wagenaar HC et al, 2001 | Leiden University Medical Center | January 1994 - July 1997 | The Netherlands, Belgium | Yes | 90 | IA - IVA | MRI | Deep stromal invasion |

| Wang T et al, 2019 | Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University | December 2016 - October 2018 | China | No | 79 | IB - IIB | MRI, PET | PMI |

| Woo S et al, 2018 | Seoul National University | 2010 - 2013 | Korea | No | 87 | IA2 - IIB | MRI | PMI |

| Wright JD et al, 2005 | Barnes-Jewish Hospital | January 1999 - September 2004 | US | No | 59 | IA - IIA | PET | PLN, PLN-s, PALN, PALN-s |

| Wu Q et al, 2017 | Henan Provincial People’s Hospital | May 2015 - August 2016 | China | Yes | 50 | NR | MRI | PLN-n |

| Xu D et al, 2017 | Cancer Hospital of China Medical University | March - December 2016 | China | Yes | 159 | IB1 - IA1 | CT | PLN+PALN |

| Xu X et al, 2016 | The First Affiliated Hospital of Anhui Medical University | January 2011 - October 2015 | China | No | 51 | IB - IVA | PET | PLN+PALN |

| Xue HD et al, 2008 | Peking Union Medical College Hospital | December 2006 - March 2008 | China | No | 24 | IB1 - IIB | MRI | PLN-n |

| Yang K et al, 2017 | Samsung Medical Center | 2001 - 2011 | Korea | No | 303 | IB1 - IIA2 | MRI | PMI |

| Yang WT et al, 2000 | Chinese University of Hong Kong, Prince of Wales Hospital, Shatin | NR | Hong Kong | Yes | 43 | IA - IIB | CT, MRI | PLN-s |

| Yang Z et al, 2016 | Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University | January 2006 - June 2013 | China | No | 113 | IB - IIA | PET | PLN+PALN, deep stromal invasion |

| Yildirim Y et al, 2008 | Aegean Obstetrics and Gynecology Training and Research Hospital | March 2006 - November 2006 | Turkey | Yes | 16 | IIB - IVA | PET | PALN |

| Yu L et al, 2011 | The Affiliated Tumor Hospital of Harbin Medical University | NR | China | Yes | 16 | IB1 - IIA | PET | PLN |

| Yu X et al, 2015 | Peking Union Medical College Hospital | April 2009 - September 2010 | China | No | 71 | IB1 - IIB | MRI | PMI, vagina |

| Yu YY et al, 2019 | Cancer Hospital of China Medical University | January 2015 - October 2017 | a,ma | No | 153 | IB - IIA | MRI | PLN |

| Zade AA et al, 2019 | Tata Memorial Hospital | NR | India | Yes | 44 | IA2 - IIB | CT,PET | PLN, PALN |

| Zhang W et al, 2019 | Multicenter | January 2009 - December 2015 | China | No | 1016 | IB1 - IIA2 | MRI | PMI, vagina |

| Zhang W et al, 2014 | Peking Union Medical College Hospital | September 2009 - December 2013 | China | No | 125 | IA2 - IIA | MRI | PLN+PALN |

CT = computed tomography; MRI = magnetic resonance imaging; NR = not reported; PALN = paraaortic lymph node (per patient); PET = positron emission tomography; PMI = parametrial invasion; PLN = pelvic lymph node (per patient); PLN+PALN = pelvic and/or paraaortic lymph node; US = ultrasonography; -n = per node; -r = per nodal region; -s = per-side

Full bibiliographical details provided in electronic supplementary data

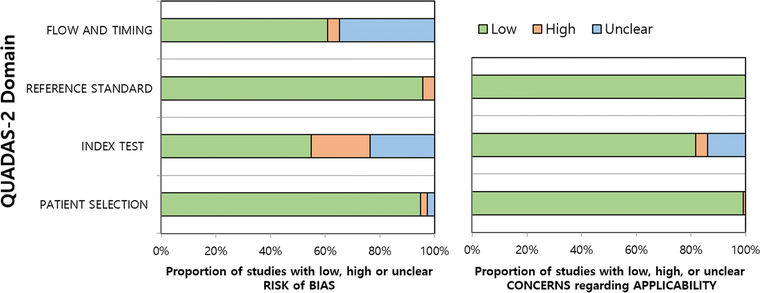

Methodological quality

In general, the quality of the studies was considered at least moderate, with 86% (99/115) showing low risk of bias and low concern for applicability in five or more of the seven domains (Figure 2). Regarding the patient selection domain, the risk of bias was high in three studies due to issues with the exclusion criteria and unclear in three others in which it was not specified whether the study population was consecutive. Concern for applicability was high in one study that only included patients with neuroendocrine cancers. Regarding the index test domain, risk of bias was considered high in 25 studies because radiologists were not blinded to the pathological results (n=2) or criteria for determining positive index test results were not pre-specified (n=10) or were derived from receiver operating characteristic curve analysis (n=13), and it was considered unclear in 27 studies because blinding was uncertain (n=18) or it was uncertain whether the criteria were pre-specified (n=9). The concern for applicability was high in 5 studies because MRI was performed using endovaginal coils (n=3) or only lymph nodes >5mm were assessed (n=2), and concern for applicability was unclear in 16 studies because the criteria for determining positive index test results were not provided. Regarding the reference standard domain, 5 studies had a high risk of bias because some patients did not have a pathological reference standard. Regarding the flow and timing domain, these same 5 studies were considered to have a high risk of bias because not all patients received the same reference standard. Furthermore, 40 studies had an unclear risk of bias because the interval between index test and reference standard was not provided.

Figure 2.

QUADAS-2 plots summarizing risk of bias and concern for applicability in the 115 studies included.

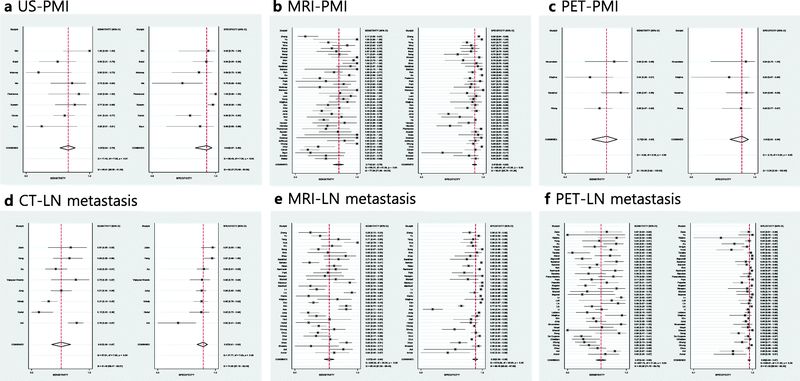

Diagnostic performance of imaging modalities in determining local disease extent

The diagnostic performance of PMI was assessed in 8, 1, 42, and 4 studies using US, CT, MRI, and PET, respectively. For US, the pooled sensitivities and specificities were 0.67 (95% CI 0.54–0.78) and 0.94 (95% CI 0.87–0.98), respectively). For CT, they were 0.43 and 0.71, respectively. For MRI, the pooled estimates were 0.71 (0.62–0.79) and 0.91 (95% CI 0.88–0.93), respectively. With regard to PET, the sensitivity and specificity were 0.73 (95% CI 0.56–0.85) and 0.91 (95% CI 0.83–0.96), respectively. Details of the sensitivity and specificity estimates for other endpoints regarding local extent along with the heterogeneity indices are summarized in Table 2. The HSROC curves and coupled forest plots of sensitivities and specificities for US, MRI, and PET for determining PMI are provided in Figures 3 and 4, while those for other combinations of imaging modalities and endpoints are provided in Supplementary Figures 1 and 2.

Table 2.

Diagnostic performance of various imaging modalities in determining local extent of cervical cancer.

| Sensitivity | Specificity | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||||||||

| Endpoint | Modality | No. of studies | Publication years | Summary estimate | 95% CI* | I2 (%) | Summary estimate | 95% CI* | I2 (%) | Cochran’s Q | P-value |

|

| |||||||||||

| PMI | US | 8 | 2007–2019 | 0.67 | 0.54–0.78 | 59.8 | 0.94 | 0.87–0.98 | 82.3 | 2.994 | 0.112 |

| per patient | 7 | 2008–2019 | 0.63 | 0.50–0.73 | 45.7 | 0.94 | 0.85–0.98 | 83.2 | 4.924 | 0.043 | |

| per side | 1 | 2007 | N/A | 1.00 | N/A | 0.95 | |||||

| CT | 1 | 2008 | N/A | 0.43 | N/A | 0.71 | |||||

| MRI | 42 | 2000–2019 | 0.71 | 0.62–0.79 | 78.0 | 0.91 | 0.88–0.93 | 88.5 | 105.480 | <0.001 | |

| per patient | 38 | 2000–2019 | 0.72 | 0.62–0.79 | 78.7 | 0.90 | 0.87–0.93 | 88.2 | 93.953 | <0.001 | |

| per side | 4 | 2000–2016 | 0.60 | 0.28–0.85 | 65.6 | 0.95 | 0.87–0.98 | 91.8 | 7.095 | 0.014 | |

| PET | 4 | 2014–2019 | 0.73 | 0.56–0.85 | 54.4 | 0.91 | 0.83–0.96 | 0.0 | 0.178 | 0.457 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Deep stromal invasion | US | 3 | 2013–2016 | N/A | 0.80–0.91 | N/A | 0.50–0.97 | ||||

| MRI | 7 | 2000–2016 | 0.82 | 0.71–0.90 | 79.6 | 0.91 | 0.73–0.97 | 88.0 | 12.892 | <0.001 | |

| PET | 1 | 2016 | N/A | 0.98 | N/A | 0.59 | |||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Internal os invasion | MRI | 5 | 2007–2016 | 0.84 | 0.70–0.92 | 0.0 | 0.96 | 0.93–0.98 | 0.0 | 0.004 | 0.499 |

|

| |||||||||||

| Vaginal invasion | US | 2 | 2013, 2019 | N/A | 0.00–0.44 | N/A | 0.99–1.00 | ||||

| MRI | 13 | 2001–2019 | 0.71 | 0.54–0.84 | 76.3 | 0.86 | 0.81–0.89 | 68.4 | 28.651 | <0.001 | |

| PET | 4 | 2014–2017 | 0.88 | 0.53–0.98 | 68.1 | 0.93 | 0.72–0.99 | 85.3 | 9.960 | 0.003 | |

|

| |||||||||||

| Bladder invasion | US | 1 | 2007 | N/A | 1.00 | N/A | 1.00 | ||||

| CT | 4 | 2000–2012 | 0.41 | 0.01–0.98 | 91.4 | 0.92 | 0.82–0.96 | 93.8 | 23.103 | <0.001 | |

| MRI | 5 | 2002–2014 | 0.84 | 0.57–0.95 | 18.8 | 0.95 | 0.87–0.98 | 75.2 | 0.011 | 0.497 | |

| PET | 1 | 2014 | N/A | 0.00 | N/A | 1.00 | |||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Rectum invasion | US | 1 | 2007 | N/A | 1.00 | N/A | 0.92 | ||||

| CT | 2 | 2002, 2012 | N/A | 0.00–0.86 | N/A | 0.85–0.99 | |||||

| MRI | 3 | 2002–2012 | N/A | 0.50–1.00 | N/A | 0.86–1.00 | |||||

|

| |||||||||||

| Bladder or rectum invasion | MRI | 2 | 2011, 2018 | N/A | 1.00 (both) | N/A | 0.96–0.98 | ||||

| PET | 2 | 2015, 2017 | N/A | 1.00 (both) | N/A | 0.98–1.00 | |||||

CI = confidence interval; N/A = none available

ranges for endpoints with ≤3 included studies

Figure 3.

Hierarchic summary ROC curves of diagnostic performance for assessment of parametrial invasion (PMI) using (A) ultrasound (US), (B) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), (C) positron emission tomography (PET) and nodal metastasis using (D) computed tomography (CT), (E) MRI, and (F) PET in patients with newly diagnosed cervical cancer.

Figure 4.

Coupled forest plots of sensitivity and specificity for studies assessing parametrial invasion (PMI) using (A) ultrasound (US), (B) magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), (C) positron emission tomography (PET) and nodal metastasis using (D) computed tomography (CT), (E) MRI, and (F) PET in patients with newly diagnosed cervical cancer. Numbers are Dashed vertical lines and diamonds represent meta-analytically pooled estimates with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). Heterogeneity statistics are provided on lower right corners.

Diagnostic performance of imaging modalities in detecting nodal metastases

Our review included 1, 8, 38, and 42 studies assessing the diagnostic performance of US, CT, MRI, and PET, respectively, in the evaluation of any metastatic nodes, regardless of anatomical location (pelvic and/or paraaortic) and level of analysis (per patient or per site). The study using US demonstrated sensitivity of 0.43 and specificity of 0.96. The pooled sensitivities and specificities were 0.51 (95% CI 0.36–0.67) and 0.87 (95% CI 0.81–0.92), respectively, for CT, 0.57 (95% CI 0.49–0.64) and 0.93 (95% CI 0.89–0.95), respectively, for MRI, and 0.57 (95% CI 0.48–0.65) and 0.95 (95% CI 0.93–0.97), respectively for PET. Table 3 shows the breakdown of the diagnostic performance levels with their heterogeneity indices. The HSROC curves and coupled forest plots of sensitivities and specificities for the overall analysis are provided in Figures 3 and 4.

Table 3.

Diagnostic performance of various imaging modalities in detecting nodal metastases.

| Sensitivity | Specificity | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||||||

| Anatomic Location | Analysis level | Modality | No. of studies | Publication Years | Summary estimate | 95% CI* | I2 (%) | Summary estimate | 95% CI* | I2 (%) | Cochran’s Q | P-value |

|

| ||||||||||||

| All | Any | US | 1 | 2015 | N/A | 0.43 | N/A | 0.96 | ||||

| CT | 8 | 2000–2019 | 0.51 | 0.36–0.67 | 81.5 | 0.87 | 0.81–0.92 | 74.8 | 15.264 | <0.001 | ||

| MRI | 37# | 2000–2019 | 0.57 | 0.49–0.64 | 85.5 | 0.93 | 0.89–0.95 | 96.5 | 590.416 | <0.001 | ||

| PET | 42 | 2001–2019 | 0.57 | 0.48–0.65 | 80.3 | 0.95 | 0.93–0.97 | 91.0 | 198.715 | <0.001 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Pelvic | Patient | US | 1 | 2015 | N/A | 0.43 | N/A | 0.96 | ||||

| CT | 3 | 2002–2019 | N/A | 0.15–0.79 | N/A | 0.63–0.97 | ||||||

| MRI | 19 | 2001–2019 | 0.61 | 0.51–0.70 | 72.6 | 0.88 | 0.82–0.92 | 91.0 | 115.860 | <0.001 | ||

| PET | 18 | 2001–2019 | 0.60 | 0.48–0.70 | 73.8 | 0.93 | 0.87–0.96 | 82.9 | 70.132 | <0.001 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Pelvic | Site | CT (per side) | 2 | 2000, 2017 | N/A | 0.51–0.65 | N/A | 0.86–0.97 | ||||

| MRI | 12 | 2000–2019 | 0.59 | 0.43–0.74 | 90.4 | 0.94 | 0.88–0.97 | 97.3 | 253.112 | <0.001 | ||

| per side | 3 | 2000–2017 | N/A | 0.24–0.71 | N/A | 0.80–0.96 | ||||||

| per region | 3 | 2010–2012 | N/A | 0.25–0.83 | N/A | 0.93–0.98 | ||||||

| per node | 6 | 2007–2019 | 0.66 | 0.44–0.82 | 93.8 | 0.92 | 0.80–0.97 | 98.4 | 213.770 | <0.001 | ||

| PET | 7 | 2005–2018 | 0.44 | 0.35–0.54 | 56.1 | 0.98 | 0.93–0.99 | 92.1 | 18.478 | <0.001 | ||

| per side | 4 | 2005–2018 | 0.38 | 0.24–0.54 | 53.6 | 0.95 | 0.88–0.98 | 70.5 | 5.818 | 0.027 | ||

| per region | 2 | 2009, 2010 | N/A | 0.36–0.46 | N/A | 0.94–0.99 | ||||||

| Per node | 1 | 2006 | N/A | 0.72 | N/A | 1.00 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Paraaortic | Patient | CT | 4 | 2002–2019 | 0.29 | 0.06–0.71 | 64.8 | 0.91 | 0.83–0.96 | 49.1 | 2.403 | 0.150 |

| MRI | 4 | 2002–2018 | 0.40 | 0.17–0.68 | 60.1 | 0.91 | 0.79–0.97 | 76.9 | 8.431 | 0.007 | ||

| PET | 15 | 2001–2019 | 0.59 | 0.37–0.77 | 78.8 | 0.96 | 0.92–0.98 | 83.5 | 26.834 | <0.001 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Paraaortic | Site | MRI (per region) | 1 | 2010 | N/A | 0.25 | N/A | 0.94 | ||||

| PET | 2 | 2005, 2010 | N/A | 0.40–0.67 | N/A | 0.99–1.00 | ||||||

| per side | 1 | 2005 | N/A | 0.40 | N/A | 0.99 | ||||||

| per region | 1 | 2010 | N/A | 0.67 | N/A | 1.00 | ||||||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Pelvic or paraaortic | Patient | CT | 3 | 2005–2017 | N/A | 0.31–0.76 | N/A | 0.62–0.88 | ||||

| MRI | 10 | 2001–2018 | 0.55 | 0.41–0.69 | 79.5 | 0.90 | 0.81–0.95 | 88.7 | 48.196 | <0.001 | ||

| PET | 15 | 2007–2017 | 0.69 | 0.53–0.81 | 81.3 | 0.90 | 0.84–0.94 | 83.1 | 49.770 | <0.001 | ||

|

| ||||||||||||

| Pelvic or paraaortic | Site | MRI | 8 | 2001–2014 | 0.39 | 0.29–0.50 | 92.6 | 0.96 | 0.94–0.98 | 99.1 | 213.842 | <0.001 |

| per region | 6 | 2001–2012 | 0.37 | 0.26–0.49 | 91.4 | 0.97 | 0.94–0.98 | 91.5 | 100.231 | <0.001 | ||

| per node | 2 | 2006, 2014 | N/A | 0.37–0.58 | N/A | 0.88–0.99 | ||||||

| PET | 7 | 2001–2015 | 0.53 | 0.33–0.73 | 91.6 | 0.98 | 0.96–0.99 | 92.0 | 45.766 | <0.001 | ||

| per region | 6 | 2001–2015 | 0.44 | 0.30–0.58 | 77.5 | 0.98 | 0.96–0.99 | 93.0 | 30.214 | <0.001 | ||

| per node | 1 | 2014 | N/A | 0.91 | N/A | 0.98 | ||||||

CI = confidence interval; N/A = none available

ranges for endpoints with ≤3 included studies

1 of 38 studies (Kang S et al, 2013) assessing nodal metastasis using MRI was excluded due to instability of hierarchical modeling

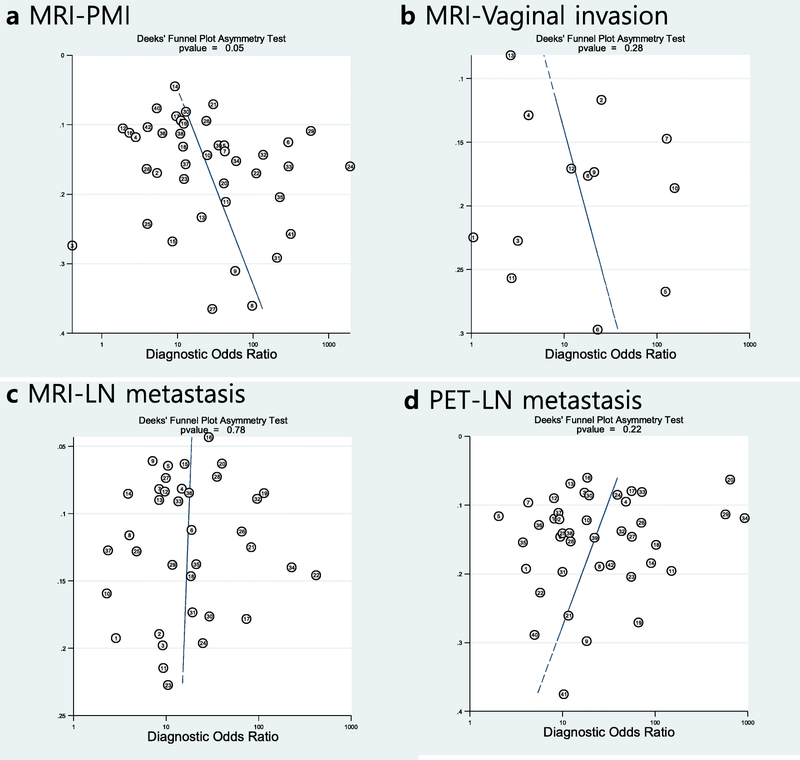

Publication bias

Publication bias was suggested for studies using MRI for PMI (p=0.05) but not for any of the other endpoints that included more than 10 patients (MRI for vaginal invasion, MRI for nodal metastasis, and PET for nodal metastasis; Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Deek’s funnel plots for endpoints including more than 10 studies. Publication bias (p = 0.05) was only suggested in (A) studies using MRI for assessment of parametrial invasion (PMI) but not in those assesing vaginal invasion using MRI (B) and lymph node metastasis using MRI (C) and PET (D). Circles represent each study while line indicates the regression line. ESS = effective sample size

Discussion

Our systematic review and meta-analysis comprehensively evaluated data published over the last two decades on the diagnostic performance of US, CT, MRI, and PET in assessing local extent and lymph node metastasis of patients with newly diagnosed cervical cancer. Our findings indicate that MRI has been extensively evaluated for assessing all aspects of local extent, demonstrating moderate sensitivity and good specificity; CT has been much less well studied and generally shows slightly lower performance levels than MRI in the assessment of local extent, while there is a paucity of data for US except with respect to assessment of PMI, where it performs comparably to MRI. For analysis of nodal metastasis, MRI and PET were the most extensively studied of the cross-sectional modalities, all of which performed comparably, with low and varied sensitivity but high specificity.

Our findings support the recommendation in the FIGO 2018 guidelines for utilization of “any imaging modality,” as they confirmed that all four modalities assessed have the potential to contribute clinically meaningful information. Because our review examined state-of-the-art and standard imaging modalities currently used to evaluate local extent and nodal metastasis of cervical cancer, it is relevant to diverse health-care settings, including low- and middle-income countries where ultrasound and CT are more widely available than MRI and PET. Furthermore, it focused on treatment-naive disease, whereas earlier published studies mostly did not differentiate between newly diagnosed, neoadjuvant treated, and recurrent disease. In addition, it included a large number of studies (n=115) and patients (n=13,999) to provide a robust overview of the role of imaging in pretreatment evaluation of cervical cancer. In our review, the diagnostic performance levels of MRI for assessing PMI and vaginal invasion–important determinants of treatment selection–were assessed in 42 and 13 studies, respectively. Regardless of the individual endpoint regarding local extent, MRI consistently demonstrated high pooled specificities (0.86–0.95), likely due to its excellent soft-tissue resolution, which enables differentiation of tumor from adjacent structures [17]. The high specificity of MRI may explain why it was recommended (although not required) in earlier FIGO guidelines [18]. Guidelines of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network and European Society of Urogenital Radiology have also recommended MRI as the imaging modality of choice in this setting [19; 20].

Our review included only 5 studies in which CT was evaluated for assessment of local extent in treatment-naive cervical cancer. The literature is sparse relative to MRI even when taking into account an earlier systematic review by Bipat et al [21] in 2003 that included studies performed between 1985 and 2002, which only found 2, 3, and 9 studies assessing rectal, bladder and PMI, respectively. Although direct comparison is not possible, in our meta-analysis, CT demonstrated inferior performance compared to MRI for several endpoints regarding assessment of local extent which are consistent with results showing inferior performance for the assessment of PMI and invasion of bladder and rectum in studies published in 1985–2002 [21]. Because CT has poorer soft-tissue resolution than MRI as well as lower spatial resolution than ultrasound, it is generally not considered to be a modality of choice for evaluating local extent, as it cannot differentiate the anatomical details of the uterus and adjacent structures. Nevertheless, as shown in our pooled analysis of endpoints related to local extent, CT can provide clinically useful information, as its specificity, though lower than that of MRI, is moderate to good.

The performance of US is more difficult to interpret for several reasons. Ultrasound has excellent soft-tissue resolution, especially when performed transvaginally [22]. However, of the four modalities we assessed, it is also the most operator dependent. Furthermore, if applied to a patient population with more advanced stages of disease, it could artificially inflate performance estimates, as patients with markedly evident extension beyond the cervix are grouped together with those with microscopic involvement. Notwithstanding these considerations, when limited to PMI, the sensitivity and specificity estimates of US appear comparable to those of MRI: 0.67 (95% CI 0.54–0.78) and 0.94 (95% CI 0.87–0.98), respectively, for US vs. 0.71 (95% CI 0.62–0.79) and 0.91 (95% CI 0.88–0.93), respectively, for MRI. Nevertheless, it should be cautioned that these similar values cannot be directly compared, as they were not acquired only from studies that were head-to-head comparisons. Taking into account all above mentioned factors, our findings suggest there may be a potential role for US in the assessment of cervical cancer, especially in certain clinical settings—for example, patients in resource-constrained areas, where access to MRI is very limited, US in addition to clinical examination would be superior to clinical examination alone for local staging. Although implementation of screening programs is one of the most important factors in facilitating detection of cervical cancer at earlier stages and in turn improve survival, potentially better evaluation of local extent by using US in certain settings will be of incremental value in this regard [23].

Regarding the detection of lymph node metastases, CT, MRI and PET were evaluated in 8, 38, and 42 studies included in our meta-analysis, respectively. Though pooled sensitivities and specificities differed slightly when stratified by level of analysis (per patient, side, station, and node) and anatomical location (pelvic and/or para-aortic), as noted above, these modalities consistently showed poor sensitivity (0.29–0.69) and high specificity (0.88–0.98). This is mainly because metastatic nodes are evaluated based on size on CT and MRI or elevated radiotracer uptake on PET—criteria that are well known to have limitations for detecting micro-metastases across various types of pelvic malignancies [24–26]. Our search yielded only 1 study since 2000 that used US to evaluate nodal metastasis, almost certainly because the field of view of US is inherently limited (especially in terms of depth) for assessing pelvic or paraaortic nodes.

Our study had several limitations. First, we could not directly compare the diagnostic performance levels of the modalities examined due to a paucity of studies providing such information. However, theoretically, network meta-analyses based on indirect comparisons could be performed, despite their inherent limitations [27]. An earlier meta-analysis that used such a methodology and included a small number of studies showed a possible, though not statistically significant, trend for PET to outperform other modalities in detecting nodal metastasis [28]. Second, the pooled sensitivities and specificities for each diagnostic modality should be used to gain a general idea of their performance for each endpoint but not compared directly, partly because they could have been influenced by the characteristics of their respective patient populations. Furthermore, in our review, we purposefully avoided incorporating cutting-edge, non-standard techniques, which include analytical methods (e.g., radiomics, histogram analysis), acquisition techniques (e.g., IVIM, integrated PET/MRI), and investigational contrast media (e.g., USPIO). There are early data supporting the incremental value of some of these techniques, but they need validation, and furthermore, they are unlikely to be available in the regions where cervical cancer is most prevalent [29–31]. It should also be noted that we focused on the diagnostic performance of imaging modalities but not on outcomes or cost. However, some studies have reported that using certain imaging modalities (e.g., MRI) for triage before treatment is cost effective [32] and that pretreatment imaging has prognostic value regarding recurrence and survival [33; 34].

In conclusion, multiple imaging modalities can contribute to the assessment of local extent of newly diagnosed cervical cancer. MRI is the method of choice for assessing any aspect of local extent, but where it is not available, US could be of value, particularly for assessing PMI. CT, MRI and PET all have high specificity but poor sensitivity for the detection of lymph node metastases and cannot obviate the need for node sampling or dissection in high-risk patients.

Supplementary Material

Supplmentary Figure 1. Hierarchical summary ROC curves of diagnostic performance of various imaging modalities for assessment of local extent other than parametrial invasion in cervical cancer.

Supplementary Figure 2. Coupled forest plots of sensitivity and specificity for studies assessing local extent other than parametrial invasion. Squares with horizontal lines represent sensitivities and specificities of each included study. Numbers are Dashed vertical lines and diamonds represent meta-analytically pooled estimates with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). Heterogeneity statistics are provided on lower right corners.

Key points.

Magnetic resonance imaging is the method of choice for assessing local extent.

Ultrasound may be helpful in determining parametrial invasion, especially in lower-resourced countries.

Computed tomography, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron emission tomography perform similarly for assessing lymph node metastasis, with high specificity but low sensitivity.

Acknowledgements

We thank Ada Muellner, Editor, Department of Radiology, Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center, for editorial assistance.

Funding Information

The work of Drs. Hricak, Vargas and Woo was supported by a P30 Cancer Center Support Grant (P30 CA008748) from the National Cancer Institute to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center. Otherwise, the authors state that this work has not received any funding.

Abbreviations:

- ADC

apparent diffusion coefficient

- CT

computed tomography

- FIGO

International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics

- HSROC

hierarchical summary receiver operating characteristic

- IVIM

intravoxel incoherent motion

- MRI

magnetic resonance imaging

- PET

positron emission tomography

- PICOS

patient, index test, comparator, outcome, and study design

- PMI

parametrial invasion

- PRISMA

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

- US

ultrasound

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest:

The authors of this manuscript declare no relationships with any companies whose products or services may be related to the subject matter of the article.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Guarantor:

The scientific guarantor of this publication is Sungmin Woo (woos@mskcc.org).

Statistics and Biometry:

No complex statistical methods were necessary for this paper.

Informed Consent:

Written informed consent was not required for this study because this was a systematic review and meta-analysis using published studies in the literature but not analysing specific human subjects.

Ethical Approval:

Institutional Review Board approval was not required because this was a systematic review and meta-analysis using published studies in the literature but not analysing specific human subjects.

Methodology

• retrospective

• multicenter study

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

References

- 1.Arbyn M, Weiderpass E, Bruni L et al. (2019) Estimates of incidence and mortality of cervical cancer in 2018: a worldwide analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 10.1016/s2214-109x(19)30482-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.FIGO World Congress (2019) International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics Global Declaration on Cervical Cancer Elimination. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet 41:102–103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rebbeck TR (2020) Cancer in sub-Saharan Africa. Science (New York, NY) 367:27–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canfell K, Kim JJ, Brisson M et al. (2020) Mortality impact of achieving WHO cervical cancer elimination targets: a comparative modelling analysis in 78 low-income and lower-middle-income countries. Lancet. 10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30157-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dursun P, Gultekin M, Ayhan A (2011) The history of radical hysterectomy. J Low Genit Tract Dis 15:235–245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhatla N, Berek J, Cuello M (2018) New revised FIGO staging of cervical cancer (2018). Abstract S020. 2FIGO XXII World Congress of Gynecology and Obstetrics Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, pp 22–36 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Woo S, Suh CH, Kim SY, Cho JY, Kim SH (2018) Magnetic resonance imaging for detection of parametrial invasion in cervical cancer: An updated systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature between 2012 and 2016. Eur Radiol 28:530–541 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thomeer MG, Gerestein C, Spronk S, van Doom HC, van der Ham E, Hunink MG (2013) Clinical examination versus magnetic resonance imaging in the pretreatment staging of cervical carcinoma: systematic review and meta-analysis. Eur Radiol 23:2005–2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu B, Gao S, Li S (2017) A Comprehensive Comparison of CT, MRI, Positron Emission Tomography or Positron Emission Tomography/CT, and Diffusion Weighted Imaging-MRI for Detecting the Lymph Nodes Metastases in Patients with Cervical Cancer: A Meta-Analysis Based on 67 Studies. Gynecol Obstet Invest 82:209–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.“World Bank Country and Lending Groups.” The World Bank, https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups. Accessed January 20, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J et al. (2009) The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J Clin Epidemiol 62:e1–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Whiting P, Rutjes AW, Reitsma JB, Bossuyt PM, Kleijnen J (2003) The development of QUADAS: a tool for the quality assessment of studies of diagnostic accuracy included in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol 3:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suh CH, Park SH (2016) Successful Publication of Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Studies Evaluating Diagnostic Test Accuracy. Korean J Radiol 17:5–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McInnes MDF, Bossuyt PMM (2015) Pitfalls of Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses in Imaging Research. Radiology 277:13–21 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Deeks JJ, Macaskill P, Irwig L (2005) The performance of tests of publication bias and other sample size effects in systematic reviews of diagnostic test accuracy was assessed. J Clin Epidemiol 58:882–893 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Higgins J, Green S Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. The Cochrane Collaboration. http://handbook.cochrane.org/chapter_9/9_5_2_identifying_and_measuring_heterogeneity.htm. Updated March 2011. Accessed January 3, 2017.

- 17.Okamoto Y, Tanaka YO, Nishida M, Tsunoda H, Yoshikawa H, Itai Y (2003) MR Imaging of the Uterine Cervix: Imaging-Pathologic Correlation. Radiographics 23:425–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pecorelli S, Zigliani L, Odicino F (2009) Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the cervix. Int J Gynaecol Obstet 105:107–108 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nougaret S, Horta M, Sala E et al. (2019) Endometrial Cancer MRI staging: Updated Guidelines of the European Society of Urogenital Radiology. Eur Radiol 29:792–805 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Freeman SJ, Aly AM, Kataoka MY, Addley HC, Reinhold C, Sala EJR (2012) The revised FIGO staging system for uterine malignancies: implications for MR imaging. Radiographics 32:1805–1827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bipat S, Glas AS, van der Velden J, Zwinderman AH, Bossuyt PM, Stoker J (2003) Computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging in staging of uterine cervical carcinoma: a systematic review. Gynecol Oncol 91:59–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bega G, Lev-Toaff AS, O’Kane P, Becker E Jr, Kurtz AB (2003) Three-dimensional Ultrasonography in Gynecology: technical aspects and clinical applications. J Ultrasound Med 22:1249–1269 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Olson B, Gribble B, Dias J, Curryer C, Vo K, Kowal P, Byles J (2016) Cervical cancer screening programs and guidelines in low- and middle-income countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet; 134:239–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Woo S, Suh CH, Kim SY, Cho JY, Kim SH (2018) The Diagnostic Performance of MRI for Detection of Lymph Node Metastasis in Bladder and Prostate Cancer: An Updated Systematic Review and Diagnostic Meta-Analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 210:W95–w109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hoshino N, Murakami K, Hida K, Sakamoto T, Sakai Y (2019) Diagnostic accuracy of magnetic resonance imaging and computed tomography for lateral lymph node metastasis in rectal cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Clin Oncol 24:46–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kakhki VR, Shahriari S, Treglia G et al. (2013) Diagnostic performance of fluorine 18 fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography imaging for detection of primary lesion and staging of endometrial cancer patients: systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. Int J Gynecol Cancer 23:1536–1543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chaimani A, Salanti G, Leucht S, Geddes JR, Cipriani A (2017) Common pitfalls and mistakes in the set-up, analysis and interpretation of results in network meta-analysis: what clinicians should look for in a published article. Evidence-based mental health 20:88–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Luo Q, Luo L, Tang L (2018) A Network Meta-Analysis on the Diagnostic Value of Different Imaging Methods for Lymph Node Metastases in Patients With Cervical Cancer. Technol Cancer Res Treat 17:1533034617742311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kan Y, Dong D, Zhang Y et al. (2019) Radiomic signature as a predictive factor for lymph node metastasis in early-stage cervical cancer. J Magn Reson Imaging 49:304–310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarabhai T, Schaarschmidt BM, Wetter A et al. (2018) Comparison of (18)F-FDG PET/MRI and MRI for pre-therapeutic tumor staging of patients with primary cancer of the uterine cervix. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 45:67–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Atri M, Zhang Z, Marques H et al. (2015) Utility of preoperative ferumoxtran-10 MRI to evaluate retroperitoneal lymph node metastasis in advanced cervical cancer: Results of ACRIN 6671/GOG 0233. Eur J Radiol Open 2:11–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lee JY, Kwon JS, Cohn DE et al. (2016) Treatment strategies for stage IB cervical cancer: A cost-effectiveness analysis from Korean, Canadian and U.S. perspectives. Gynecol Oncol 140:83–89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Han S, Kim H, Kim YJ, Suh CH, Woo S (2018) Prognostic Value of Volume-Based Metabolic Parameters of (18)F-FDG PET/CT in Uterine Cervical Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. AJR Am J Roentgenol 211:1112–1121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang YT, Li YC, Yin LL, Pu H (2016) Can Diffusion-weighted Magnetic Resonance Imaging Predict Survival in Patients with Cervical Cancer? A Meta-Analysis. Eur J Radiol 85:2174–2181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplmentary Figure 1. Hierarchical summary ROC curves of diagnostic performance of various imaging modalities for assessment of local extent other than parametrial invasion in cervical cancer.

Supplementary Figure 2. Coupled forest plots of sensitivity and specificity for studies assessing local extent other than parametrial invasion. Squares with horizontal lines represent sensitivities and specificities of each included study. Numbers are Dashed vertical lines and diamonds represent meta-analytically pooled estimates with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (CI). Heterogeneity statistics are provided on lower right corners.