Abstract

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is a rare but potentially serious complication of pregnancy, the main symptom of which is intense pruritus with elevated serum levels of bile acids. The elevated serum bile acid concentration is regarded as a predictor for poor perinatal outcome including intrauterine death. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) has become established as the treatment of choice in clinical management to achieve a significant improvement in symptoms and reduce the cholestasis. Pregnant women with severe intrahepatic cholestasis should always be managed in a perinatal centre with close interdisciplinary monitoring and treatment involving perinatologists and hepatologists to minimise the markedly increased perinatal morbidity and mortality as well as maternal symptoms.

Key words: cholestasis of pregnancy, pruritus, bile acids, antenatal care, induction of labor, fetal death

Introduction

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is a reversible liver disease that involves disturbed secretion of biliary substances and pruritus in previously healthy skin. This disorder is usually characterised by its reversible and benign course. It consists diagnostically of maternal pruritus with elevated bile acids and/or elevated transaminases in the serum, usually from the late second or third trimester. There are no primary skin changes though intense scratching can lead to secondary excoriations.

The pruritus ceases immediately postpartum, usually within a few days, and the elevated liver function tests should normalise within a few weeks. Recurrence is frequent at up to 70% in subsequent pregnancies. There is currently no guideline in Germany on intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) can significantly reduce the maternal pruritus and the elevated bile acids.

Epidemiology

ICP is subject to considerable geographic and ethnic variation. In Germany, roughly 0.7 – 1% of all pregnancies are affected. Throughout Europe, the highest incidence is found in Scandinavian countries. The incidence can be much higher in South America and China 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 . A seasonal increase in incidence in the winter months has been described 5 .

Pathogenesis and Risk Factors

The pathogenesis of ICP is so far not fully understood. It was first described by Ahlfeld in 1883 6 . Genetic 7 , 8 , 9 , hormonal 10 and environmental 5 factors are involved in the aetiology. The disease occurs more often in multiparous women and multiple pregnancies 2 , 3 , 11 , 12 . Other risk factors are maternal age > 35 years and low selenium 13 , 14 and vitamin D levels 15 , 16 . An increased risk was also reported in women with chronic hepatitis C infection 17 , 18 . The incidence appears to be increased after assisted reproduction treatment as raised bile acids are found more often in these women 19 . Because of hormonal triggering with accumulation of progesterone metabolites there is a disturbance of hepatocyte bile acid secretion with a cholestatic effect. Certain sulphated progesterone metabolites such as PM2DiS, PM3S and PM3DiS appear to play an important part in the pathogenesis of ICP and pruritus 20 . For instance, vaginal progesterone replacement increased the incidence of ICP compared with controls (0.75 vs. 0.23%, aOR 3.16, 95% CI 2.23 – 4.49, p < 0.01) 21 . Cholestasis parameters can increase and pruritus can occur with oral contraceptives with a high oestrogen content 22 . This should also be borne in mind when contraceptives are re-prescribed. The WHO recommends progestogen mono- or depot preparations, progestogen-containing IUDs or etonogestrel implants for these women. Combined oral contraceptives can be prescribed after a strict benefit-risk assessment provided the benefit outweighs the risk 23 ( Table 1 ).

Table 1 Maternal risk factors.

| Maternal risk factors |

|---|

| Maternal age (> 35 years) |

| Low selenium level |

| Low vitamin D level |

| Chronic HCV infection |

| Polymorphisms in bile transporters (e.g. ABCB4, ABCB11, etc.) |

| Multiple pregnancy |

Pruritus as the main symptom occurs particularly in the third trimester as the highest concentrations of oestrogen and progesterone metabolites in the course of the pregnancy are reached then. The function of the two important transport proteins BSEP (bile salt export pump, bile acid transporter) and MDR3 (multidrug resistance associated protein 3, phospholipid transporter) is reduced 24 ( Table 2 ).

Table 2 Symptoms.

| Clinical features |

|---|

| Pruritus |

| Effects of scratching (e.g., excoriations, prurigo nodularis) |

| Mental stress (insomnia, fatigue) |

| Malabsorption (steatorrhoea, vitamin K deficiency, rarely peripartum haemorrhage) |

| Dyslipidaemia |

| Upper abdominal discomfort |

| Nausea |

| Anorexia |

In pregnancy there is a physiological rise and a change in the composition of the bile acids. In women with ICP the concentration of cholic acid (CA) increases proportionally compared with that of chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA). In normal pregnancies the ratio of CDCA to CA is the same, possibly with slight predominance of CDCA 25 . There is also a shift to the taurine-conjugated bile acids and thus to a reduction in the glycine-taurine ratio 26 . At the same time, a foeto-maternal bile acid concentration gradient develops 25 . In addition, a maternal immunological imbalance has been described in association with ICP.

The pathogenesis is also influenced by molecular genetic factors that affect the mechanisms of the bile acid receptor and bile acid transport. Genetic variations are found in ca. 10 – 15% of cases of ICP 27 . The most frequent genetic abnormality at 16% involves mutations in the ABCB4 gene, which codes for MDR3 (multidrug resistance-associated protein 3), responsible for the transmembrane transport of phospholipids into bile 7 , 27 . In 5% there is a mutation of the ABCB11 gene, which codes for the liver-specific protein BSEP (bile salt export pump). This can result in liver cell damage due to accumulation of toxic bile acids in the hepatocytes as transport of bile acids from the hepatocytes into bile is impaired due to the mutation 27 , 29 . This gene mutation is also associated with an increased risk of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) 27 . The altered genes can be diagnosed by means of Sanger sequencing and NGS panel sequencing. Genetic testing after a pregnancy with these clinical features could be considered in an individual case with regard to the late consequences. Other genes that play a part in ICP are ATP8B1, TJP2, ABCC2, NR1H4, FGF19 and SLC4A2 13 , 27 , 30 , 31 , and the development of cholestasis is due to the complex variability, differences in penetrance and a variety of environmental factors 13 . It can be assumed that certain pregnancy-associated changes such as the altered oestrogen and progesterone levels and pre-existing raised bile acid levels lead to increased expression of the disorder in genetically predisposed women 32 .

It is important to note at this point that intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is a diagnosis of exclusion and the laboratory and clinical changes must cease completely after delivery. If elevated liver and cholestasis parameters persist, further investigation by a hepatologist is important as primary biliary cholangitis (PBC), primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), autoimmune hepatitis (AIH) or familial cholestasis syndromes can be associated with similar laboratory abnormalities and clinical symptoms (pruritus) in pregnancy ( Table 3 ).

Table 3 Differential diagnosis.

| Differential diagnosis |

|---|

| Viral hepatitis (A – E) |

| Pre-existing liver disease (PBC, PSC) |

| Obstructive jaundice |

| Fatty liver of pregnancy |

| HELLP/PE |

Complications and Prognosis

Placental insufficiency or foetal arrhythmias resulting in intrauterine foetal death (1.5%) are feared complications 9 , 22 , 33 . Moreover, depending on the bile acid concentration, premature delivery, often induced 33 , foetal stress with meconium-containing amniotic fluid or respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) and thus the need for neonatal intensive care, can occur in up to 25% 22 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 . The risk for foetal morbidity and mortality correlates with the level of the bile acids 13 , 36 , which accumulate in the foetal compartment 26 . The risk for the foetus appears to be caused by increased myocardial and contractile complications 37 , 38 , 39 , 40 . In addition, pathological vasoconstrictor mechanisms acting on the foeto-placental vessels due to bile acids are suspected 32 . Uterine contractility can increase 42 through increased expression of oxytocin receptors in the myometrium caused by bile acids 41 . The risk for intrauterine foetal death rises significantly and is more than doubled in women with a bile acid concentration of over 100 µmol/l 36 , 43 , 44 . The risk for IUFT also increases with pregnancy age.

Geenes et al. showed a significantly increased risk for IUFT in 713 women at a bile acid concentration of ≥ 40 µmol compared with the control group with a normal pregnancy (1.5 vs. 0.5%; adjusted OR 2.58, 95% CI 1.03 – 6.49). An increased rate of premature deliveries was also described compared with the control group (non-adjusted OR 7.39, 95% CI 5.33 – 10.25), especially iatrogenically induced 33 .

In the meta-analysis by Ovadia et al. a significantly increased rate of IUFT was seen only at bile acid concentrations above 100 µmol/l (3.44%, 95% CI 2.05 – 5.37) while only a tendency was observed at a concentration up to 40 µmol/l (0.13%, 95% CI 0.02 – 0.38) and at 40 – 99 µmol/l (0.28%, 95% CI 0.08 – 0.72). The large meta-analysis also showed that women with ICP have a significantly increased risk of both spontaneous (OR 3.47, 95% CI 3.06 – 3.95) and iatrogenically induced premature delivery (OR 3.65, 95% CI 1.94 – 6.85). The prevalence was high in all three groups (< 40 µmol/l [16.5%, 95% CI 15.1 – 18.0]; 40 – 99 µmol/l [19.1%, 95% CI 17.1 – 21.1]; ≥ 100 µmol/l [30.5%, 95% CI 26.8 – 34.6]). In addition, neonates of women with ICP had a significantly higher rate of meconium-stained amniotic fluid (OR 2.60, 95% CI 1.62 – 4.16) and also had to be admitted more often to a neonatal intensive care unit (OR 2.12, 95% CI 1.48 – 3.03) 36 .

A systematic review based on 1200 singleton pregnancies found perinatal mortality of 6.8% at maternal bile acid concentrations of ≥ 100 µmol/l compared with 0.3% at bile acid concentrations of ≥ 40 µmol/l. The preterm delivery rate and the rate of meconium-stained amniotic fluid were also significantly increased 45 . Due to the vasoconstrictor effect of the meconium, acute foetal danger may occur as a result of reduced placental perfusion 46 . Pregnancy-associated comorbidities such as pre-eclampsia and gestational diabetes can increase the risk for intrauterine foetal death even in women with lower bile acid concentrations 36 , 43 . The risk of preterm delivery increases for women above bile acid concentrations of over 40 µmol/l 36 .

In a French cohort with 140 women a significantly increased risk was also found for respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) in neonates of women with ICP (17.1 vs. 4.6%, p < 0.001; crude OR 4.46 (95% CI 2.49 – 8.03) 35 .

Clinical Features

The disorder manifests towards the end of the first trimester in 10%, in the second trimester in 25% and predominantly in the third trimester in 65% of cases 47 . The main symptom is new-onset severe cholestatic pruritus. This is accompanied by jaundice as a result of extrahepatic cholestasis in fewer than 10% 48 . The pruritus usually starts in the extremities, can become generalised over the entire integument and can be very troublesome for the pregnant woman 13 . Typically, the palms of the hands and soles of the feet are most affected. This can occur before any skin or laboratory manifestation. It is suspected that this pruritus is attributable to the direct pruritogenic effect of bile acids in the skin 5 , though the serum concentration of the bile acids does not correlate with the severity of the pruritus 49 , 50 . The subjective perception of pruritus can vary greatly individually. Other nonspecific symptoms are right-sided upper abdominal pain due to stretching of the liver capsule, nausea and anorexia. In very rare cases, secondary steatorrhoea and vitamin K deficiency may develop. There are usually no primary skin changes. Secondary effects in the skin produced by intensive scratching may appear. The association between the pruritus and the laboratory changes remains unclear as these may precede the itching but may also only occur subsequently 13 .

Women with ICP are affected more often by dyslipidaemia, gestational diabetes and foetal macrosomia and pre-eclampsia 12 , 15 , 22 , 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 . In a recently published study, an increased incidence of pre-eclampsia was found in women with ICP (7.78 vs. 2.41%, aOR 3.74, 95% CI 12.0 – 7.02, p < 0.0001), and also in women with a twin pregnancy. The earlier in pregnancy the ICP occurred, the higher was the association with pre-eclampsia. On average, affected women developed pre-eclampsia about 30 days after the diagnosis (29.7 ± 24 days) 52 .

The incidence of intrauterine foetal death in pregnant women with ICP depends on the serum bile acid concentration and is ca. 1,5%.

As a rule, the disorder resolves completely in the mother within a few days to 6 weeks postpartum and the liver tests normalise. A protracted postpartum course occurs rarely. If the liver function tests are still abnormal 6 weeks postpartum, other causes of liver dysfunction must be considered. Recurrence in subsequent pregnancy is common, occurring in up to 70% 17 . There is an increased lifetime risk in the mother for hepatobiliary disease 17 , such as gallstone disorders and cholangitis 55 and for cardiovascular and immunological diseases such as diabetes mellitus, hypothyroidism or Crohnʼs disease 51 .

Diagnosis

ICP is a diagnosis of exclusion. Elevated transaminases in combination with elevated bile acids and pruritus confirm the suspected diagnosis. It must be ensured that the bile acids in the serum are measured in the fasting state as oral food ingestion leads to a rise in this parameter. The bile acids play an important part in fat digestion and as a solubiliser and inhibitor of cholesterol synthesis. The primary bile acids cholic acid (CA), and chenodeoxycholic acid (CDCA), which are present in conjugated compounds, are the most important representatives. They are excreted as lithocholic and deoxycholic acid. Because of their hydrophobic structure, they could play a clinically important part as a toxic metabolite in the pathomechanism of cholestasis 56 .

The transaminases can be increased 2 – 10-fold in 20 – 60% 48 . The ratio of ASAT/ALAT is usually < 1 47 , 57 . The bile acid concentration in the serum is regarded as the most sensitive parameter. In late pregnancy, depending on the laboratory, a concentration of up to 11 µmol/l is considered normal 26 . Hyperbilirubinaemia occurs in only 10 – 20%. The partial thromboplastin time (pTT) can be prolonged because of possible vitamin K deficiency 5 . The enzyme autotaxin has been described as a highly sensitive predictive marker for cholestasis of pregnancy but it is not available in routine clinical practice 50 .

Liver ultrasonography usually appears normal in women with ICP. Nevertheless, posthepatic biliary obstruction should be excluded by abdominal ultrasound, especially as the incidence of ICP is increased in patients with cholelithiasis 48 . In any case, however, this should be done postpartum at the latest if the symptoms persist longer than 4 – 6 weeks after delivery. Since microscopic liver changes are usually nonspecific, liver biopsy for histological confirmation is not indicated. As well as other pregnancy-related dermatoses, viral hepatitis in particular (e.g., hepatitis viruses A – E), pre-existing liver disease such as primary biliary cholangitis (PBC) or primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), obstructive jaundice and pre-eclampsia/HELLP syndrome and acute fatty liver of pregnancy should be excluded in the differential diagnosis. Certain genetic causes for ICP are also associated with an increased risk for gallstones, cholecystitis or cholangitis and with the development of liver fibrosis and malignant disease. For this reason, affected persons, especially those with severe disease, should be offered genetic counselling and genetic testing if appropriate 27 .

Treatment

The primary aim of treatment is to reduce the clinical symptoms by reducing the laboratory test results while reducing foetal complications also.

The agent of choice is ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), a tertiary, hydrophilic bile acid that occurs physiologically 43 . Absorption takes place both passively via diffusion in the jejunum and ileum and actively in the distal ileum 58 . A dose of 13 – 15 mg/kg body weight/d 2 , 59 is recommended. The starting dose should be 500 mg and the maximum daily dose is 2 g 60 . In a meta-analysis, pruritus was reduced significantly with this compared with placebo (OR 0.21, 95% CI 0.07 – 0.62, p < 0.01), the transaminases were normalised (OR 0.18, 95% CI 0.06 – 0.52, p < 0.001) or reduced (OR 0.12, 95% CI 0.05 – 0.31, p < 0.0001) and the bile acids were reduced (OR 0.30, 95% CI 0.12 – 0.73, p < 0.01). The authors concluded that the use of UDCA would also be able to improve the perinatal outcome 61 . However, this was not confirmed in the recently published PITCHES study with 605 women, though the study was underpowered for patients with severe forms of ICP 43 . It is of particular importance that UDCA can also reduce the bile acids in amniotic fluid and cord blood 25 , 62 . Since the drug is not licensed in pregnancy, it requires separate informed consent (off-label use). UDCA was used successfully in many thousands of pregnant women and significant side effects did not occur apart from mild diarrhoea 61 .

Treatment with UDCA can increase the measured bile acids in the serum. UDCA accounts for approximately 60% of total bile acids 63 . This should be noted so as to avoid misinterpretation and resulting indication for delivery.

According to a Cochrane review from 2013 statistically significantly fewer preterm deliveries were seen in women on treatment with UDCA compared with placebo (RR 0.46, 95% CI 0.28 – 0.73). The results were not significant with regard to fewer signs of foetal stress and less meconium in the amniotic fluid and higher birth weight in the UDCA group 64 .

Two more meta-analyses also reported a reduction in the rate of preterm deliveries 65 , 79 .

Cholestyramine can be used as an alternative, but this proved inferior to UDCA in a randomised study 66 . Reduced fat absorption with cholestyramine therapy can cause vitamin K deficiency and subsequently an increased bleeding tendency in mother and child. Vitamin K can be given intravenously to reduce the risk of peripartum haemorrhage in severe cases 3 .

Other treatment options are S-adenosylmethionine (SAM) 47 , 61 , which can be used in dosages of about 1000 mg/day as second-line therapy, especially for persistent pruritus. In a randomised controlled study by Roncaglia et al. SAM proved less effective than UDCA as regards reducing the serum levels of bile acids, transaminases and bilirubin. The improvement in the pruritus was similar 67 . This is also confirmed by a meta-analysis from 2016, in which UDCA was more effective than SAM in the treatment of ICP and significantly and effectively reduced the pruritus score, bile acids and rate of preterm delivery 68 . Combined treatment with both medications in 89 pregnant women with mild ICP (bile acid concentration < 40 µmol/l) was shown to be equivalent with regard to an unfavourable perinatal outcome 69 .

Rifampicin in dosages of 150 – 300 (up to a maximum of 600) mg/d can be considered as third-line therapy. This bactericidal tuberculostatic drug exhibits anticholestatic mechanisms 59 . The intensity of the pruritus can diminish and the cholestasis parameters can be reduced by combined treatment with UDCA 70 .

A Cochrane analysis from 2019 of pharmacological interventions concluded that treatment with UDCA reduces pruritus symptoms only slightly. A reduction in the foetal risks remains unclear. There is insufficient evidence for other pharmacological therapies, for example SAM, dexamethasone, cholestyramine and others 71 .

Supportive treatment with moisturising and cooling effects, e.g. with menthol ingredients, is possible and may provide relief 13 . If a patient is found to have a genetic disease-associated variant of ABCB4, lifelong treatment by UDCA must be discussed 27 .

Management

There are no uniform recommendations internationally on monitoring a pregnant woman with ICP 72 . Since last year, the S2k guideline on induction of delivery includes recommendations on the procedure in cases of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy 73 .

The severity of the maternal symptoms and the risks to the child from an iatrogenic preterm delivery must be weighed against the risk of acute placental insufficiency and subsequent intrauterine foetal death in the third trimester with expectant management.

During the pregnancy, weekly laboratory measurement of the transaminases, bilirubin and bile acids is indicated to monitor treatment so as to identify possible short-term progression of the ICP 74 . If outpatient treatment is unsuccessful, the patient must be admitted to hospital for foetal monitoring and appropriate treatment adjustment.

Termination of pregnancy must be considered depending on the age of the pregnancy at bile acid concentrations above 40 µmol/l. If treatment is unsuccessful, premature delivery appears to be the only possible intervention that can prevent an unfavourable perinatal outcome. UDCA alone was unable to significantly reduce the occurrence of IUFT, the preterm delivery rate and foetal stress 43 .

The extent to which maternal bile acids influence foetal heart rate alterations in women with and without ICP is currently being investigated in a prospective pilot study (Bile Acid Effects in Fetal Arrhythmia Study, “BEATS”) 75 .

Delivery of pregnant women with ICP after 36 weeks proved to be the optimal procedure in a statistical decision analysis of pre- and postpartum decision-making factors 76 .

In a large American retrospective study the perinatal mortality with delivery after 36 weeks was much lower compared with a wait-and-see approach (4.7 vs. 19.2 per 10 000 deliveries out of a total of 1.6 million deliveries) 77 .

Since severe ICP with maternal jaundice and highly elevated bile acids of ≥ 100 µmol is associated with high perinatal mortality, early inpatient foeto-maternal monitoring and delivery after 35 – 36 weeks should be discussed despite the paucity of data 45 . There is no absolute indication for caesarean section.

Since definite predictive factors, especially for the risk of IUFT are lacking, the bile acid concentration remains the most important factor in decision-making, even though IUFT can occur suddenly without warning as the most severe though rare complication. Management should be tailored individually all the more.

Since December 2020 the new S2k guideline on induction of delivery provides recommendations on management at term of pregnant women with ICP 73 . According to this, induction of delivery must be recommended from 38 + 0 weeks if ICP is present (expert consensus; consensus strength +++). It is also stated that induction of delivery should be recommended from 37 + 0 weeks and that induction of delivery can be recommended even in the period from 34 + 0 to 36 + 6 weeks when the bile acid concentration is above > 100 µmol/l (expert consensus; consensus strength +++).

Comment: The graduation in the German-language recommendations is divided according to the respective binding strength of the recommendations. “Must” stands for a strong recommendation with highly binding character and “should” for a regular recommendation with moderately binding character 73 .

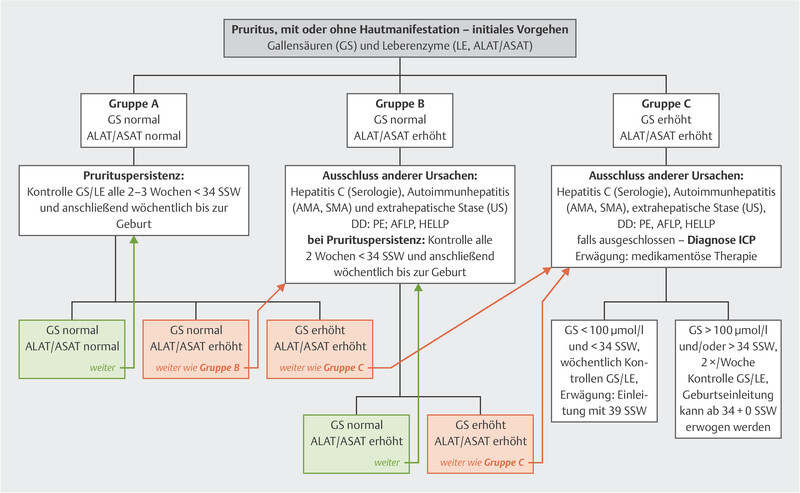

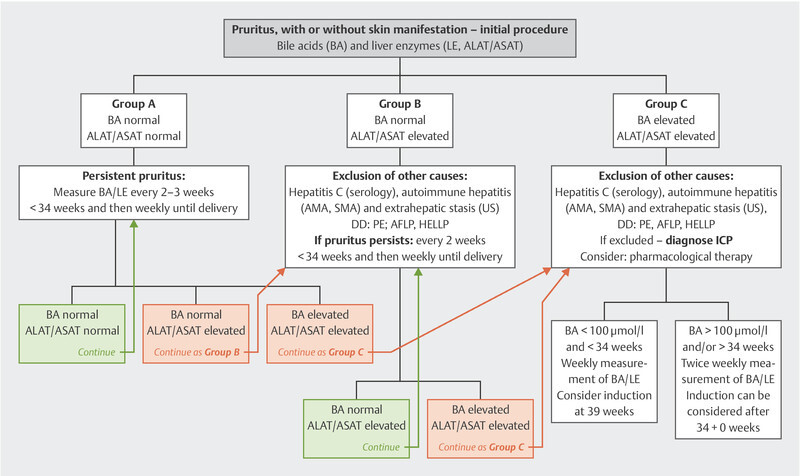

A very discriminating recommendation based on constantly updated literature searches can be found at www.icpsupport.org 60 . The sometimes different treatment recommendations regarding the times in the German S2k guideline are explained by the unclear data internationally and should be noted ( Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Management of women with ICP according to www.icpsupport.org 60 , modified and adapted to the German recommendations of 73 .

Fig. 1 is based on the RCOG Green-top Guideline No. 43 from 2011 which is continually updated according to the most recent findings (see also Mitchell et al., 2021 78 and Ovadia et al. 2021 79 ). When this article went to press, the RCOG had not yet updated its recommendations. Once their new recommendations are published, this Figure will be updated promptly and will be available at www.icpsupport.org .

In future, progesterone metabolites could be a predictive marker for ICP; these can be found in raised concentrations in early pregnancy and show an association with pruritus 20 .

The decision for expectant management or active termination of pregnancy can only be made with consideration of the pregnant womanʼs individual risk profile based on the subjective pruritus stress, laboratory test results and their course, additional risks (gestational diabetes, pre-eclampsia) and additional foetal diagnostics (CTG, biometry/Doppler ultrasonography) and may require interdisciplinary consultation and care of the pregnant woman by obstetricians, neonatologists and hepatologists.

Summary

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) is a rare but potentially serious complication of pregnancy, the main symptom of which is intense pruritus with elevated serum levels of bile acids. These are regarded as a predictor for poor perinatal outcome including intrauterine death. Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) has become established as the treatment of choice in clinical management to achieve a significant improvement in symptoms and reduce the cholestasis. Pregnant women with severe intrahepatic cholestasis should always be managed in a perinatal centre with close interdisciplinary monitoring and treatment involving perinatologists and hepatologists to minimise the markedly increased perinatal morbidity and mortality as well as maternal symptoms.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest/Interessenkonflikt The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest./Die Autorinnen/Autoren geben an, dass kein Interessenkonflikt besteht.

References/Literatur

- 1.Pusl T, Beuers U. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:26. doi: 10.1186/1750-1172-2-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Floreani A, Gervasi M T. New insights on intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Clin Liver Dis. 2016;20:177–189. doi: 10.1016/j.cld.2015.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ovadia C, Williamson C. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: recent advances. Clin Dermatol. 2016;34:327–334. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2016.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geenes V, Williamson C, Chappel L C. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Obstet Gynaecol. 2016;18:273–281. doi: 10.1111/tog.12308. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith D D, Rood K M. Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2020;63:134–151. doi: 10.1097/GRF.0000000000000495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ahlfeld F. Leipzig: Grunow FW; 1883. Berichte und Arbeiten aus der geburtshilflich-gynaekologischen Klinik zu Giessen 1881 – 1882; p. 148. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dixon P H, Wadsworth C A, Chambers J. A comprehensive analysis of common genetic variation around six candidate loci for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2014;109:76–84. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacquemin E, De Vree J M, Cresteil D. The wide spectrum of multidrug resistance 3 deficiency: from neonatal cholestasis to cirrhosis of adulthood. Gastroenterology. 2001;120:1448–1458. doi: 10.1053/gast.2001.23984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lammert F, Marschall H U, Glantz A. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: molecular pathogenesis, diagnosis and management. J Hepatol. 2000;33:1012–1021. doi: 10.1016/s0168-8278(00)80139-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Reyes H, Sjövall J. Bile acids and progesterone metabolites in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Ann Med. 2000;32:94–106. doi: 10.3109/07853890009011758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez M C, Reyes H, Arrese M. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy in twin pregnancies. J Hepatol. 1989;9:84–90. doi: 10.1016/0168-8278(89)90079-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raz Y, Lavie A, Vered Y. Severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is a risk faktor for preeclampsia in singleton and twin pregnancies. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:3950–3.95E10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kremer A E, Wolf K, Ständer S. Intrahepatische Schwangerschaftscholestase. Hautarzt. 2017;68:95–102. doi: 10.1007/s00105-016-3923-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kauppila A, Korpela H, Mäkilä U M. Low serum selenium concentration and glutathione peroxidase activity in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1987;294:150–152. doi: 10.1136/bmj.294.6565.150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wikström Shemer E, Marschall H U. Decreased 1,25-dihydroxy vitamin D levels in women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:1420–1423. doi: 10.3109/00016349.2010.515665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gençosmanoğlu Türkmen G, Vural Yilmaz Z, Dağlar K. Low serum vitamin D level is associated with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol Res. 2018;44:1712–1718. doi: 10.1111/jog.13693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marshall H U, Wikstrom Shermer E, Ludvigsson J F. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy ans associated hepatobiliary disease: a population-base cohort study. Hepatology. 2013;58:1385–1391. doi: 10.1002/hep.26444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wijarnpreecha K, Thongprayoon C, Sanguankeo A. Hepatitis C infection and intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2017;41:39–45. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2016.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolubkas F F, Bolubkas C, Balaban H Y. Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy: Spontaneous vs. in vitro Fertilization. Euroasian J Hepat-Gastroenterol. 2017;7:126–129. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10018-1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abu-Hayyeh S, Ovadia C, Lieu T. Prognostic and mechanistic potential of progesterone sulfates in intrahepatic cholestasis of preganancy and pruritus gravidarum. Hepatology. 2016;63:1287–1298. doi: 10.1002/hep.28265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsur A, Kan P. 68: Vaginal progesterone treatment is associated with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020;222:S58–S59. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2019.11.084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Glantz A, Marshall H U, Mattsson L A. Intraheptaic cholestasis of pregnancy: relationship between bile acid levels and fetal complication rates. Hepatology. 2004;40:467–474. doi: 10.1002/hep.20336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.WHO . World Health Organization; 2015. Medical Eligibility Criteria for Contraceptive Use. 5th ed. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kondrackiene J, Kupcinskas L. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy – current achievements and unsolved problems. World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5781–5788. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Geenes V, Lövgren-Sandblom A, Benthin L. The Reversed Feto-Maternal Bile Acid Gradient in Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy IS Corrected by Ursodeoxycholic Acid. PLoS One. 2014;9:e83828. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brites D. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: changes in maternal-fetal bile acid balance and improvement by ursodeoxycholic acid therapy in cholestasis of pregnancy. Ann Hepatol. 2002;1:20–28. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keitel V, Dröge C, Häussinger D.Genetische Ursachen cholestatischer Lebererkrankungen. Falk Gastro-Kolleg 3/2019Accessed March 30, 2020 at:https://www.drfalkpharma.de/uploads/tx_toccme2/FGK_3_19_Keitel_Web.pdf

- 28.Dixon P H, Williamson C. The pathophysiology on intrahepatic cholestasis pf pregnancy. Clin Res Hepatol Gastroenterol. 2016;40:141–153. doi: 10.1016/j.clinre.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dixon P H, van Mil S W, Chambers J. Contribution of variant alleles of ABCB11 to susceptibility to intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Gut. 2009;58:537–544. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.159541. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Dixon P H, Sambrotta M, Chambers J. An expanded role for heterozygous mutations of ABCB4, ABCB11, ATP8B1, ABCC2 and TJP2 in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Sci Rep. 2017;7:11823. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-11626-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Henkel S A, Squires J H, Ayers M. Expanding etiology of progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis. World J Hepatol. 2019;11:450–463. doi: 10.4254/wjh.v11.i5.450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Williamson C, Geenes V. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:120–133. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0000000000000346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Geenes V, Chappell L C, Seed P T. Association of severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with adverse pregnancy outcomes: a prospective population-based case-control study. Hepatology. 2014;59:1482–1491. doi: 10.1002/hep.26617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Brouwers L, Koster M P, Page-Christiaens G C. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: maternal and fetal outcomes associated with elevated bile acid levels. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:1000–1.0E9. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2014.07.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Arthuis C, Diguisto C, Lorphelin H. Perinatal outcomes of intrahepatic cholestasis during pregnancy: An 8-year case-control study. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0228213. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0228213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ovadia C, Seed P T, Sklavounos A. Association of adverse perinatal outcomes of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with biochemical markers: results of aggregate and individual patient data meta-analyses. Lancet. 2019;393:899–909. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31877-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Al Inizi S, Gupta R, Gale A. Fetal tachyarrhythmia with atrial flutter in obstetric cholestasis. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 2006;93:53–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2005.12.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ataalla W M, Ziada D H, Gaber R. The impact of total bile acid levels on fetal cardiac function in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy using fetal echocardiography: a tissue Doppler imaging study. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2016;29:1445–1450. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2015.1051020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sanhal C Y, Kara O, Yucel A. Can fetal left ventricular modified myocardial performance index predict adverse perinatal outcomes in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy? J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2017;30:911–916. doi: 10.1080/14767058.2016.1190824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williamson C, Miragoli M, Sheikh Abdul Kadir S. Bile acid signaling in fetal tissues: implications for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Dig Dis. 2011;29:58–61. doi: 10.1159/000324130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Germain A M, Kato S, Carvajal J A. Bile acids increase response and expression of human myometrial oxytocin receptor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:577–582. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00545-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zhao P, Zhang K, Yao Q. Uterine contractility in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2014;34:221–224. doi: 10.3109/01443615.2013.834878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.for the PITCHES study group . Chappell L C, Bell J L, Smith A. Ursodeoxycholic acid versus placebo in women with intraheptic cholestasis of pregnancy (PITCHES): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019;394:849–860. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31270-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kawakita T, Parikh L I, Ramsey P S. Predictors of adverse neonatal outcomes in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;213:5700–5.7E10. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.06.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Di Mascio D, Quist-Nelson J, Riegel M. Perinatal death by bile acid levels in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a systematic review. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2019 doi: 10.1080/14767058.2019.1685965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Altshuler G, Arizawa M, Molnar-Nadasdy G. Meconium-induced Umbilical Cord Vascular Necrosis and Ulceration: A Potential Link Between the Placenta and Poor Pregnancy Outcome. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79 (5 Pt 1):760–766. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lammert F, Rath W, Matern S. Lebererkrankungen in der Schwangerschaft. Molekulare Pathogenese und interdisziplinäres Management. Gynäkologe. 2004;37:418–426. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lammert F, Rath W. 3. Aufl. München: Elsevier GmbH; 2016. Lebererkrankungen; pp. 450–453. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ghent C N, Bloomer J R, Klatskin G. Elevations in skin tissue levels of bile acids in human cholestasis: relation to serum levels and topruritus. Gastroenterology. 1977;73:1125–1130. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kremer A E, Bolier R, Dixon P H. Autotaxin activity has a high accuracy to diagnose intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. J Hepatol. 2015;62:897–904. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2014.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Wikström Shemer E A, Stephansson O, Thuresson M. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy and cancer, immunemediated and cardiovascular diseases: A population-based cohort study. J Hepatol. 2015;63:456–461. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2015.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mor M, Shmueli A, Krispin E. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy as a risk factor for preeclampsia. Arch Gynecol Obstet. 2020;301:655–664. doi: 10.1007/s00404-020-05456-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Martineau M G, Raker C, Dixon P H. The metabolic profile of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy is associated with impaired glucose tolerance, dysllipidemia, and increased fetal growth. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:243–248. doi: 10.2337/dc14-2143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Majewska A, Godek B, Bomba-Opon D. Association between intrahepatic cholestasis in pregnancy and gestational diabetes mellitus. A retrospective analysis. Ginekol Pol. 2019;90:458–463. doi: 10.5603/GP.2019.0079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ropponen A, Sund R, Riikonen S. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy an an indicator of liver and biliary diseases: a population-based study. Hepatology. 2006;43:723–728. doi: 10.1002/hep.21111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sinakos E, Marshall H U, Kowdley K V. Bile acid chnages after high-dose ursodeoxycholic acid treatment in primary sclerosing cholangitis: Relation to disease progression. Hepatology. 2010;52:197–203. doi: 10.1002/hep.23631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hammoud G M, Ibdah J A. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2012. The Liver in Pregnancy; pp. 919–940. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Parquet M, Metman E H, Raizman A. Bioavailability, gastrointestinal transit, solubilization and faecal excretion of orsodeoxycholic acid in man. Eur J Clin Invest. 1985;15:171–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.1985.tb00164.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.European Association for the Study of the Liver . EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines: management of cholestatic liver diseases. J Hepatol. 2009;51:237–267. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2009.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Accessed June 17, 2021 at:https://www.icpsupport.org/protocol.shtml

- 61.Bacq Y, Sentilhes L, Reyes H B. Efficacy of ursodeoxycholic acid in treating intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:1492–1501. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Geenes V, Williamson C. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. World J Gastroenterol. 2009;15:2049–2066. doi: 10.3748/wjg.15.2049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Manna L B, Ovadia C, Lövgren-Sandblom A. Enzymatic quantification of total serum bile acids as a monitoring strategy for women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy receiving ursodeoxycholic acid treatment: a cohort study. BJOG. 2019;126:1633–1640. doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.15926. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gurung V, Middleton P, Milan S J. Interventions for treating cholestasis in pregnancy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;(06):CD000493. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD000493.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.GrandʼMaison S, Durand M, Mahone M. The effects of ursodeoxycholic acid treatment for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy on maternal and fetal outcomes: a meta-analysis including non-randomized studies. J Obstet Gynaecol Can. 2014;36:632–641. doi: 10.1016/S1701-2163(15)30544-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kondrackiene J, Beuers U, Kupcinskas L. Efficacy and safety of ursodeoxycholic acid versus cholestyramine in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Gastroenterology. 2005;129:894–901. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Roncaglia N, Locatelli A, Arreghini A. A randomised controlled trial of ursodeoxycholic acid and S-adenosyl-l-methionine in the treatment of gestational cholestasis. BJOG. 2004;111:17–21. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-0528.2003.00029.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zhang Y, Lu L, Victor D W. Ursodeoxycholic Acid and S-adenosylmethionine for the Treatment of Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy: A Meta-analysis. Hepat Mon. 2016;16:e38558. doi: 10.5812/hepatmon.38558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Triunfo S, Tomaselli M, Ferraro M I. Does mild intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy require an aggressive management? Evidence from a prospective observational study focused on adverse perinatal outcomes and pathological placental findings. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2020 doi: 10.1080/14767058.2020.1714583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Geenes V, Chambers J, Khurana R. Rifampicin in the treatment of severe intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2015;189:59–63. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2015.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Walker K F, Chappell L C, Hague W M.Pharmacological interventions for treating intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy Cochrane Database Syst Rev 202007CD000493 10.1002/14651858.CD000493.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bicocca M J, Sperling J D, Chauhan S P. Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: Review of six national and regional guidelines. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2018;231:180–187. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2018.10.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.für die DGGG und Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Geburtshilfe und Pränatalmedizin in der DGGG e. V. Kehl S, Abou-Dakn M.S2k-Leitlinie GeburtseinleitungAccessed December 27, 2020 at:https://www.awmf.org/uploads/tx_szleitlinien/015-088l_S2k_Geburtseinleitung_2020-12.pdf

- 74.Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists . London: RCOG; 2011. Obstetric Cholestasis. RCOG Green-top Guideline No. 43. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bile Acid Effects in Fetal Arrhythmia Study (BEATS)Accessed August 31, 2020 at:https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03519399

- 76.Lo J O, Shaffer B L, Allen A J. Intrahepatic Cholestasis of Pregnancy and Timing of Delivery. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2015;28:2254–2258. doi: 10.3109/14767058.2014.984605. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Puljic A, Kim A, Page J. The risk of infant and fetal death by each additional week of expectant management in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy by gestational age. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:6670–e667.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2015.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mitchell A, Ovadia C, Syngelaki A. Re-evaluating diagnostic thresholds for intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: case-control and cohort study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2021 doi: 10.1111/1471-0528.16669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Ovadia C, Sajous J, Seed P T.Ursodeoxycholic acid in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a systematic review and individual participant data meta-analysis Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol 20216547–558.Online:https://www.thelancet.com/journals/langas/article/PIIS2468-1253(21)00074-1/fulltext [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]