Abstract

Plasmids, circular DNA that exist and replicate outside of the host chromosome, have been important in the spread of non-essential genes as well as the rapid evolution of prokaryotes. Recent advances in environmental engineering have aimed to utilize the mobility of plasmids carrying degradative genes to disseminate them into the environment for cost-effective and environmentally friendly remediation of harmful contaminants. Here, we review the knowledge surrounding plasmid transfer and the conditions needed for successful transfer and expression of degradative plasmids. Both abiotic and biotic factors have a great impact on the success of degradative plasmid transfer and expression of the degradative genes of interest. Properties such as ecological growth strategies of bacteria may also contribute to plasmid transfer and may be an important consideration for bioremediation applications. Finally, the methods for detection of conjugation events have greatly improved and the application of these tools can help improve our understanding of conjugation in complex communities. However, it remains clear that more methods for in situ detection of plasmid transfer are needed to help detangle the complexities of conjugation in natural environments to better promote a framework for precision bioremediation.

Keywords: Bioremediation, Horizontal gene transfer, Plasmids

Introduction

The simplicity and specificity of microorganisms, compared to higher-order organisms, has allowed them to evolve strikingly rapidly. Mobile genetic elements (MGEs) such as plasmids have played a key role in this rapid evolution because of an organism’s ability to easily transfer genes to an organism of a different species (Frost et al. 2005; Gogarten and Townsend 2005). Plasmids are circular genetic elements made up of deoxyribose nucleic acid (DNA) that can replicate independently from the chromosome of the host cell. Plasmids can transfer via a process called conjugation which involves cell-to-cell contact. Genes responsible for conjugation can often be found on the plasmid itself or nearby helper plasmids (Sørensen et al. 2005). Plasmids, ranging from less than one kilobase pairs (kb) to several hundred kb, can represent a significant amount of the genetic material and plasticity in an organism (Hayes 2003). These MGEs often include non-essential genes that provide an organism with a particular competitive advantage in a selective environment, such as antibiotic and metal resistance or contaminant degradation. Because of this competitive advantage, plasmid transfer via conjugation has widely contributed to the spread of antibiotic resistance, of which genes are commonly carried by plasmids (O’Brien 2002; Alanis 2005; Von Wintersdorff et al. 2016). Of recent public health concern is the ability of plasmids to carry resistance to multiple antibiotics and successfully conjugate into a wide range of bacterial hosts (Alanis 2005; Fricke et al. 2009; Gullberg et al. 2014).

Due to their transferability and provision of selective advantages, plasmids have also been widely useful in medicine and biotechnology. Utilizing the conjugative capabilities of plasmids to widely disseminate pollutant degradation genes in the environment is of particular interest to environmental engineers, specifically to break down organic contaminants that are harmful to human and ecological health (Venkata Mohan et al. 2009; Mrozik and Piotrowska-Seget 2010). Xenobiotics found to be degraded via plasmid-mediated biodegradation are numerous and include various hydrocarbons (benzene, toluene, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons), pesticides, and other toxic compounds such as chlorinated biphenyls or phthalates. Bioremediation of these contaminants utilizing plasmid-mediated degradation tends to be less environmentally intrusive and costly than physical remediation approaches such as dredging and capping and can be applied broadly. Bioremediation is accomplished either by stimulating endogenous microorganisms or augmenting exogenous organisms with known degradative capabilities; however, when there are no endogenous organisms capable of degradation, augmented microorganisms that are not site-adapted may not survive (Thompson et al. 2005). In those instances, the addition of mobilizable degradative plasmids to the polluted environment, termed genetic bioaugmentation (Fig. 1), can be used to overcome these challenges by increasing the abundance of relevant biodegradative genes in indigenous, well-adapted bacteria and stimulate their expression (Top et al. 2002; Top and Springael 2003; Ikuma and Gunsch 2012).

Fig. 1.

Schematic representing a genetic bioaugmentation remediation scheme. a Exogenous bacteria harboring degradative plasmids (green) are augmented into the environment where they can transfer plasmids to well-adapted native bacteria for contaminant degradation (blue). b Conjugation of a degradative plasmid occurs via transfer through the pilus of a replicated plasmid

Although promising, genetic bioaugmentation relies on many processes that scientists have yet to fully understand. Successful genetic bioaugmentation requires the survival of the donor organisms harboring the degradative plasmids, which could be reliant on various biotic and abiotic factors. Conjugation itself has already been found to rely on a multitude of factors—however many properties affecting transfer of plasmids have yet to be understood, such as which microorganisms are more likely to participate in conjugation events. Finally, successful genetic bioaugmentation requires plasmid stability and expression in transconjugants. Current studies that have investigated how these key factors affect plasmid transfer, stability, and expression are limited for degradative plasmids likely due to lack of methods for tracking conjugation and difficulty identifying and characterizing degradative plasmids in the environment. However, recent advances in plasmid transfer detection methods as well as identification and characterization of new, relevant degradation plasmids has expanded the possibility of genetic bioaugmentation as a sustainable remediation method. This necessitates a complete understanding of key factors influencing plasmid transfer, stability, and expression for successful genetic bioaugmentation. The current review addresses these key factors and knowledge gaps while highlighting research needs to understand and quantify these factors.

Genetic basis of conjugation

Successful genetic bioaugmentation relies on a fundamental understanding of conjugation from a genetic standpoint. The F plasmid from Escherichia coli K-12 was the first described plasmid responsible for genetic transfer. The fertility (F) factor encodes a sex pilus responsible for connecting the donor and recipient species to allow for transfer of plasmid DNA (Cavalli et al. 1953). The F plasmid is a 100 kb plasmid with multiple segments consisting of regions responsible for replication, conjugation, and multiple transposable elements (Firth et al. 1996). All F-like plasmids carrying this unique fertility factor, though functionally diverse in replication or partition systems, have been classified into the Incompatibility Group F (IncF). Plasmids in unique incompatibility groups are unable to stably coexist in a cell due to sharing elements of the same replication system. Competition of replication factors leads to the ability of one plasmid to solely exist in the cell (Novick and Hoppensteadt 1978).

In addition to IncF plasmids, there are multiple other incompatibility groups that contain self-conjugatable plasmids. Plasmids in incompatibility groups P, N, W, and X form a short, rigid pilus compared to the more ancestral long and flexible pilus formed by F-like plasmids (Fernandez-Lopez et al. 2016). This type of sex pilus is more relevant compared to the F-type sex pilus because most xenobiotic-degrading plasmids that are self-conjugatable belong to these incompatibility groups (Fernandez-Lopez et al. 2017). The genetic region involved in incompatibility groups P, N, W, and X is shorter than its ancestral relative’s transfer region and is controlled by multiple promoters (Kennedy et al. 1977; Frost et al. 1994; Lawley et al. 2003). This region is constituted as a Type IV secretion system (T4SS). The T4SS is initiated by the binding of a relaxase and accessory factors to the origin of transfer (oriT), resulting in a complex called the relaxosome. The relaxosome is responsible for translocating the DNA through a channel as well as catalyzing recirculation of the DNA in the recipient cell (Draper et al. 2005; César et al. 2006; Garcillán-Barcia et al. 2007). The channel used in translocation of the DNA is formed by the mating-pair formation (mpf). The mpf is comprised of an ATPase and a cross-membrane protein subunit—together which are responsible for the translocation channel as well as the pilus filament (Lawley et al. 2003; Christie and Cascales 2009).

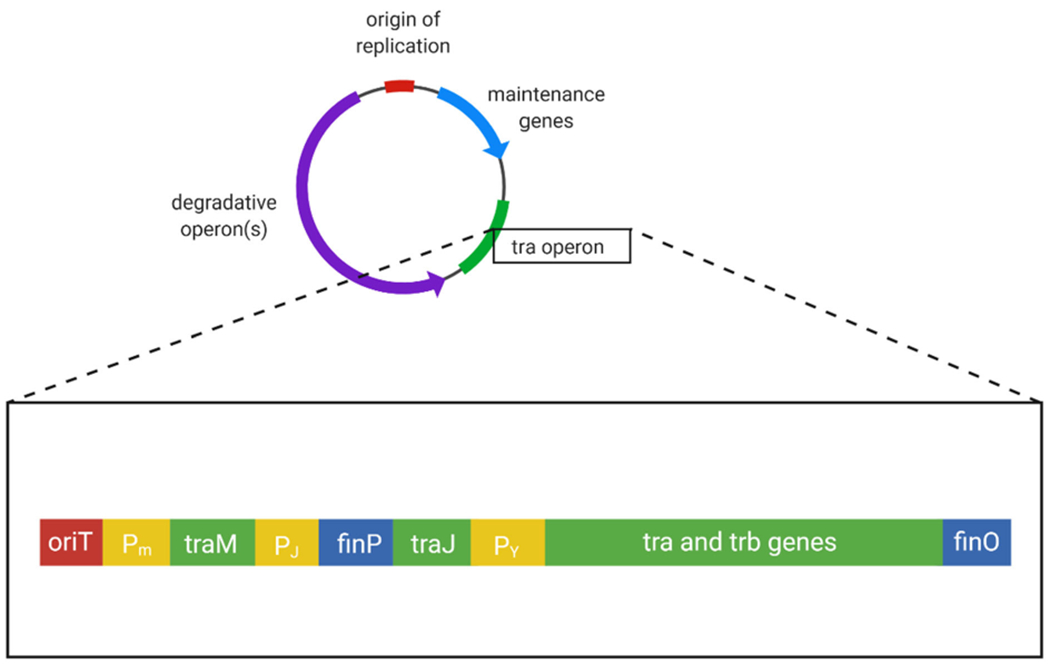

Genes responsible for the relaxosome and mpf complexes are located on a 34 kb transfer region consisting of tra and trb genes and two regulatory genes, finP and finO (Fig. 2). The relaxosome consists of proteins both chromosomally and plasmid encoded, particularly from the tra genes (Furste et al. 1989; Lanka and Wilkins 1995). The mpf complex is primarily formed by eleven components encoded by genes trbB to trbL, as well as traF (Haase et al. 1995). Outside of these two complexes, accessory genes in the transfer region aid in regulation and incompatibility. Regulation is carried out by finP and finO which repress the positive regulatory product of traJ in which transfer is dependent upon. Surface exclusion, carried out by the gene products of traS and traT, is a method of plasmid incompatibility in which they block the entry of a similar T4SS plasmid into a cell that already contains one. This T4SS transfer region consisting of tra, trb, and fin genes are regulated by promotors Pm, Pi, and Py (Grohmann et al. 2003). Many genes present in this region, however, still have unknown function and importance in conjugation.

Fig. 2.

A generalized map of a mobilizable degradative plasmid zoomed in to reveal the tra operon. Represented within the operon are the origin of transfer (red), promotors (yellow), regulatory genes (blue) and genes responsible for transfer (green)

Abiotic properties affecting conjugation

Efficient plasmid conjugation in heterogeneous environments is challenging. Various abiotic properties have been considered in isolation; however, their aggregate impact is yet to be fully understood. Moisture content, temperature, pH, organic matter, dissolved oxygen, and nutrient bioavailability are known to play an important role in determining conjugation occurrence and transfer efficiency, especially for plasmids involved in degradation in xenobiotics (Garbisu et al. 2017).

Moisture can readily become limiting for degradative microorganisms in contaminated soils that are undergoing active bioremediation, which in turn can decrease conjugation occurrence. Moisture content affects contact between donor and recipient cells which will decrease the physical contact that is needed for conjugation to occur (Miller et al. 2004; Aminov 2011). In soil, the optimal moisture content for RP4 (a non-degradative plasmid), a DDT-degrading plasmid, and a chlorpyrifos-degrading plasmid is between 40 and 60% (Lafuente et al. 1996; Zhang et al. 2012; Gao et al. 2015). Some studies, such as Shintani et al. (Shintani et al. 2008) found the highest conjugation occurrence of a carbazole degradative plasmid at 100% soil moisture. Conversely, when ample nutrients are available, Bleakley and Crawford (1989) found that as low as a 20% moisture content, compared to 40–60%, showed the highest conjugation frequency between Streptomyces species. Therefore, although it is clear that soil moisture content has an effect on conjugation, optimal levels of moisture content may be compounded with other abiotic and biotic factors.

Temperature is known to affect conjugation; however, most published studies have focused on the transfer of non-catabolic plasmids between Escherichia coli strains. In those studies, an increase in conjugation is generally observed with increasing temperatures with peak conjugation frequency occurring between 30 and 37 °C (Fernandez-Astorga et al. 1992; Lafuente et al. 1996; Headd and Bradford 2018). In few studies performed with degradative plasmids the optimal temperature for conjugation and degradation was between 29 and 35 °C (Johnsen and Kroer 2007; Zhang et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2014; Gao et al. 2015). Temperature is thought to be a key factor in conjugation possibly due to its role in the regulation of proteins encoded in the transfer (tra) regions of mobilizable plasmids (Forns et al. 2005). Similarly, pH is known to affect the stability of proteins depending on the acceptable range of the donors and recipients and therefore is another important abiotic factor to consider. In general, the range of pH that confers the highest amount of plasmid transfer is between 6 and 8 (Fernandez-Astorga et al. 1992; Lafuente et al. 1996).

Secondary factors such as high concentrations of oxygen, inorganic nutrients, and carbon substrates may indirectly affect conjugation by conferring an advantage in a xenobiotic-contaminated environment via promotion of degradative genes on the plasmid or by stimulating production of normal cell functions (Seoane et al. 2010). Subsequently, many biostimulation strategies involve addition of these nutrients to promote contaminant degradation. The first step in most aerobic xenobiotic degradation involves the addition of oxygen to the molecule. Therefore, most degradative plasmids are only useful to aerobic organisms that already require oxygen as an electron acceptor with an abundance oxygen present in the environment. To our knowledge, no studies have looked a catabolic plasmid transfer under anaerobic conditions. Krol et al. (2011) found that an increase in oxygen concentration can increase plasmid transfer through an oxygen-related mechanism or indirectly due to its impact on normal cell functionality. For inorganic nutrients such as nitrogen and phosphorus, results remain unclear whether or not the addition of nutrients directly stimulates conjugation—particularly in cases where addition of nitrogen and phosphorus happens less frequently than every day (Elsas and Bailey 2006; Fox et al. 2008; Shintani et al. 2008). However, there are evidence that an increase in nutrients increases degradative plasmid transfer and degradation of contaminants likely as an indirect affect due to the promotion of microbial growth more broadly (Seoane et al. 2010; Wang et al. 2014). It is likely, therefore, that the diversity of microorganisms and complexity of the environment plays a large role in determining whether the increased availability of nutrients is necessary for an increase in conjugation frequency. More cohesive studies investigating the composition of microbial communities, nutrient availability, and their effects on plasmid transfer is required to untangle these complexities.

For catabolic plasmids, the presence of the substrate in high enough concentrations is often necessary as a selective pressure for a cell to host the plasmid and encourage conjugation. DiGiovanni et al. (1996) observed that 2,4-D present exhibited enough selective pressure for the transfer of the relative degradative plasmid. In many cases for conjugation of degradative plasmids, higher concentrations of the substrate will increase conjugation and degradation (Zhang et al. 2012; Wang et al. 2014). Contrarily, however, Ikuma and Gunsch (2012) found that environmentally relevant concentrations of toluene might not exhibit a selective pressure high enough to promote transfer of the toluene-degrading TOL plasmid. Oftentimes the substrate is not bioavailable because of its chemical nature or interaction with the organism. For example, hydrophobic contaminants, such as PAHs and PCBs, readily sorb to soils and sediments and avoid the aqueous phase, making it harder for bacteria to uptake (Megharaj et al. 2011). Without the selective pressure of the contaminant of interest, the metabolic burden of large catabolic plasmids might be too great to encourage production of conjugation machinery or even continue to host the plasmid. Organic matter or carbon sources other than the contaminant of interest has also been shown to increase conjugation of catabolic plasmids indirectly. For example, adding organic growth substrates to bioreactors has been shown to increase conjugation and plasmid expression of antibiotic plasmids (Bleakley and Crawford 1989). Another example of growth substrate added to increase conjugation is glucose. Studies such as Pearce et al. (2008) have described an increase in conjugation with the addition of glucose in soils. Similarly, Johnsen and Kroer (2007) found an increase in transfer of the 2,4-D degradative plasmid pRO103 with addition of maltose. Furthermore, many plasmid-encoded degradation phenotypes are co-metabolic and necessitate an additional carbon source to carry out the function of interest.

It is important to note that most studies on conjugation involve antibiotic resistance plasmids (i.e. R plasmids). These plasmids tend to be smaller in size, more prevalent, and better characterized than the catabolic counterparts that are instrumental to bioremediation applications. While extremely useful data have been garnered from those studies, care must be taken when translating those findings to degradative plasmids. For example, Ikuma et al. (2012) found no change in conjugation of a toluene-degradative plasmid with addition to glucose which is contrary to results found with antibiotic resistance plasmids. Catabolic plasmids tend to be larger in size and the role metabolic burden plays on conjugation efficiency of degradative plasmids remains an open question.

Organismal and community properties affecting conjugation

In addition to the abiotic factors discussed previously, there are also several biological properties to consider. For instance, morphological, physical, and biochemical traits of donor and recipient bacteria could have a sizable effect on plasmid transfer and gene expression. While it is known that many of these properties can affect conjugation, only a handful of studies have considered their impact.

First, high specific growth rate and metabolic activity has been shown to increase transfer efficiency (Johnsen and Kroer 2007; Smets et al. 1993). Specifically, a high metabolic rate in the donor increased the transfer of a catabolic plasmid (Johnsen and Kroer 2007). Growth rate and metabolic activity are linked to many different ecological processes, but Wickham and Lynn (1990) proposed that DNA size has a large influence on these properties likely due to more complex molecular and regulation properties with a larger amount of DNA. Therefore, the energy and resources it requires to maintain larger plasmids may affect the growth of a donor which, consequently, can decrease conjugation occurrence and persistence of the plasmid in the organisms and in the environment long-term.

The ability of both the donor and recipient in conjugation to form biofilms also has a great effect on competition and conjugation. Biofilms not only protect bacteria against predation or toxins, but also provide environments where conjugation can happen more frequently due to the close nature of cells in the biofilm, making biofilms ‘hot spots’ for horizontal gene transfer (Stalder and Top 2016). Similarly, cell motility is a property of both donor and recipient strains that can directly affect the occurrence and rates of conjugation or indirectly affect these rates by encouraging biofilm formation (Garbisu et al. 2017). Interestingly, many study designs involve homogenous liquid cultures of bacteria which is suboptimal for biofilm formation which, in turn, could result in lower conjugation rates due to the lower likelihood of contact between cells. Pinedo and Smets (2005) determined the most effective ratio of donor to recipient to be 1:103 in liquid cultures due to the requirement of cell-to-cell contact. More studies in environments promoting biofilm formation are needed to identify how biofilms increase conjugation events of catabolic plasmids and help differentiate the effects of other properties on plasmid transfer (Stalder and Top 2016).

Although some degradative plasmids have a broad-host range, phylogenetic relatedness, guanine-cytosine (G+C) content, codon usage biases, and restriction proficiency of the recipient have been shown to be important properties affecting conjugation efficiency and phenotypic expression (Pinedo and Smets 2005; Thomas and Nielsen 2005; Ikuma and Gunsch 2012). Phylogenetic relatedness of donor and recipient strains is a property that encompasses a combination of genetic properties of both bacteria. However, many studies indicate an increase in transfer of degradative plasmids with closer species relatedness. Through a meta-analysis of thirty-two plasmid conjugation studies, Alderliesten et al. (2020) reported a lower conjugation frequency in liquid matings with an increase in phylogenetic distance. For filter matings, the influence of relatedness on conjugation is still unclear. Interestingly, Hall et al. (2016) describes that single-species transfer might limit sustained plasmid transfer compared to two-species communities in both models and experiments. This phenomenon, termed ‘source-sink plasmid dynamics’, is where the source of a plasmid (donor) transfers the plasmid to recipient which is a sink for further conjugation. The two-species communities are able to better maintain access to plasmid accessory genes compared to single-species communities due to the segregation and purifying selection that occurs in conjugation between a singular species. The impact of phylogenetic relatedness on degradative plasmid transfer is a multi-level, intricate relationship that still needs to be further investigated.

The influence phylogenetic relatedness has on conjugation occurrence and frequency is likely linked to genetic factors such as G+C content and codon usage bias (Santos and Ochman 2004). Popa et al. (2011) demonstrated that donors and recipients that underwent successful conjugation had less than a 5% deviation in G+C content Additionally, genomic G+C content may be an indicator of codon usage biases which could create differences between codon usage in the donor and recipient. Codon usage is especially important in transcription and translation which particularly will affect the expression of the plasmids more than transfer (Garbisu et al. 2017).

One of the most important genetic factors determining the occurrence and rate of conjugation are restriction mechanisms encoded by the donor and recipient. Plasmids can be grouped into incompatibility groups based on these restriction mechanisms. Plasmids within an incompatibility group are unable to exist and be inherited in a single bacterium. In general, this is due to two incompatible plasmids sharing elements of the replication system. A formal classification scheme based on incompatibility was first developed by Datta and Hedges. To this day, there are about 30 incompatibility groups for enteric bacteria and 7 for staphylococcus (Datta and Hedges 1973). Incompatibility can be symmetric, where one of the two plasmids is lost with equal probability, or vectorial, where one plasmid is lost almost exclusively when residing with another plasmid. Symmetric incompatibility arises as a consequence of random selection of replication gene copies, whereas vectorial incompatibility is usually due to interference of replication by regulatory genes carried by the plasmid (Novick 1987).

Vectorial incompatibility in plasmids is attributed to two main mechanisms: inhibitor-target and iteron-binding. These mechanisms involve the negative regulation of plasmid replication and can occur directly or indirectly. In inhibitor-target incompatibility, a plasmid encodes for a replication inhibitor that binds to a specific target on the plasmid (Tomizawa et al. 1981; Light and Molin 1982; Kumar and Novick 1985). Iteron-binding incompatibility involves a plasmid encoding an initiator protein which initiates tandem, arrayed repeated oligonucleotides (known as iterons) near the origin of replication. This allows the plasmid to control the concentration of the initiator protein as well as binding of the initiator to the iterons which encode for proteins responsible for direct or indirect replication inhibition (Novick 1987). Within the context of inhibitor-target and iteron-binding mechanisms, incompatibility is due to interference with self-correcting processes of the plasmid that involve copy number of the replication system (Novick and Hoppensteadt 1978). Because conjugation requires replication of the plasmid into the recipient cell, restriction mechanisms are highly important in determining transfer occurrence (Thomas and Nielsen 2005). Although many degradative plasmids belong to a select few incompatibility groups, new groupings are being discovered as more are sequenced and knowledge of restriction mechanisms continues to grow. Therefore, a plasmid’s incompatibility group solely will not determine its conjugation success and subsequently its conjugation efficiency.

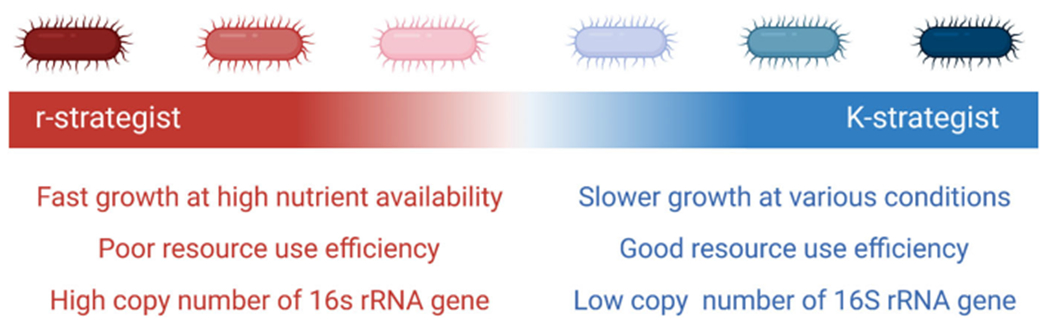

There has been limited research measuring the prevalence of conjugation in complex communities especially where heterogeneous conditions exist. One approach for considering the impact of community dynamics on conjugation that has not been extensively studied is investigating ecological growth strategies (Fig. 3). Bacterial evolution has favored two ecological growth strategies: high reproduction rate (the r-strategists), or optimal resource utilization (the K-strategists). This designation stems from survival curves where r-strategists maximize their intrinsic rate of growth (r) and K-strategists are well-adapted when populations are near carrying capacity (K) (Atlas and Bartha 1997). Depending on the resource availability and the microbial density, the ecology of an ecosystem may change over time to favor a particular life strategy which can change the functional dynamics of the microbial community and the gene pool. Frier et al. (2007, 2017) attempted an ecological classification of bacterial phyla to better understand the structure and function of bacterial communities based on a phylum’s growth response to carbon amendments. They found a negative relationship between carbon amendment level, nutrient level and Acidobacteria abundance, and a positive relationship for Bacteriodetes and β-Proteobacteria suggesting those phyla were K- and r-strategists, respectively.

Fig. 3.

A spectrum of growth strategies of microorganisms exist with r-strategists (red) on one end and K-strategists (blue) on the other. Properties seen for each extreme are listed

Though helpful in a larger context, these designations are not narrow enough for use in the implementation of genetic bioaugmentation. Bacterial strains residing in the same phylum or even in the same genus can adapt widely different ecological growth strategies. In addition, characterizing these ecological strategies solely on growth could be problematic as organismal growth is dependent on environmental conditions and community dynamics. Therefore, other means have been used to designate these ecological relationships. The most supported correlation is between the number of copies of the 16S rRNA gene within the genome and the ecological growth strategy. A higher copy number of 16S rRNA genes in the genome is associated with a higher specific growth rate and lower carbon use efficiency (Klappenbach et al. 2000; Roller et al. 2016; Wu et al. 2017; Ortiz-Álvarez et al. 2018). This finding supports the notion that ecological growth strategies have been inherently adapted by bacterial species and the adaptation has been imprinted in the genome on a spectrum—r-strategists on one side and K-strategists on the other. Vieria-Silva and Rocha (2010) also found positive correlations between codon usage bias and specific growth rate suggesting more genome imprinting from adapted growth strategies. Certain environments also select for specific growth strategies. For example, relevant to bioremediation, toxic environments often select for K-strategists because these bacteria are better suited for resource use efficiency particularly under more stressful environments. However, in heterogeneous environments such as soils, selection for particular growth strategies may not be uniform depending on the micro-environment.

Although there is substantial theoretical evidence for ecological growth strategies of bacteria influencing conjugation, this area of research is vastly understudied with only a few studies relating to this topic. Conjugation of the toluene-degrading TOL plasmid has been found to increase with the specific growth rate of both the donor and recipient (Seoane et al. 2010; Smets et al. 1993a). This relationship suggests a likely influence of faster-growing bacteria (r-strategists) being able to transfer and receive degradative plasmids better than the slower-growing K-strategists, especially in environments with ample nutrient availability. Sysoeva et al. (2019) furthered this research with antibiotic resistance plasmids. In that work, they discovered that plasmids exhibit three types of transfer regimens: (1) the growth stage of an organism had no effect on conjugation, (2) plasmid transfer occurred more often with donors in exponential phase of growth, and (3) plasmid transfer occurred more often with donors in stationary phase of growth. Not only was the donor’s growth phase important, the researchers found that the growth stage of the recipient had a significant effect on the rate of plasmid transfer. This work further supports the rationale that conjugation is affected by the growth strategies of not only the donor but also the recipient. Brzeszcz et al. (2016) was the first study to explicitly assess the relationship between ecological growth strategies and hydrocarbon degradation. They found that Mycobacterium fredericks-bergense IN53, a K-strategist, was a much more efficient hydrocarbon degrader than Acinetobacter sp. IN47, an r-strategist, in an environment with low moisture content and high hydrocarbon load. This suggests that a K-strategists might be more adept at maintaining or transferring a catabolic plasmid in limiting conditions compared to an r-strategist. Although these studies point to an influence of ecological growth strategies on conjugation and expression, much more research needs to be done to disentangle these relationships to understand and promote successful genetic bioaugmentation.

Catabolic plasmid expression and stability

Successful bioaugmentation relies not only on fast and sustained plasmid transfer but also expression of degradation genes and stability of the plasmid in individual bacteria and throughout the environment long-term. G+C content, phylogenetic relatedness, and various environmental conditions have been shown to impact whether plasmid genes are expressed following conjugation, however expression is often linked to multiple reasons which are often hard to detangle and identify. The long term survival of a plasmid within a bacterial population can be influenced by a plethora of contributing factors. Although some factors, including sustained selective pressures, are known to have a profound influence on the persistence of plasmids, more research needs to be done to understand all confounding influences on plasmid persistence.

Expression of a plasmid phenotype may be associated with the G+C content of the recipient cell. The basis of this concept is that the expression of transferred genes depends most importantly on the recognition of the promoter sequence by the transcription machinery. This promoter recognition is dependent on the G+C content of the sequence which may be deduced from the overall genomic G+C content and, subsequently, phylogenetic relatedness (Mulligan and Mcclure 1986). Two studies from Navarre et al. (2006, 2007) found transferred DNA that is G+C-poor compared to the recipient genome may experience silencing and therefore will not be expressed. Furthermore, studies by Ikuma and Gunsch (2012, 2013) demonstrated that expression of the catabolic pWW0 TOL plasmid was higher in transconjugants with a similar genomic G+C content and phylogenetic relatedness to the donor. They also found an increase in expression of transconjugants with the addition of glucose as an alternative carbon source to the toluene. Some additional evidence has reached contradictory conclusions regarding the more successful plasmid expression in phylogenetically related organisms. Between members of the same genus and even the same species, De Gelder et al. (2007) found that the stability of an IncP antibiotic resistance plasmid had large variation in the stability of the plasmid. Variation seemed to be due to segregational loss of the plasmid and high plasmid cost rather than phylogenetic relatedness. The stability of plasmids, particularly larger plasmids, appears to be dependent on specific genetic interaction between the plasmid and the host chromosome which is increasingly complex in diverse environments (Hall et al. 2016; Kottara et al. 2018). Some of the genetic interactions can be described by direct factors such as G+C content and general phylogenetic relatedness, however these relationships are often complex and other factors likely also contribute to gene expression patterns.

The complexity of a plasmid stably being maintained and expressed within a host often is associated with the metabolic burden a plasmid exerts on a host. The host bacterium may not express or keep a plasmid if the metabolic burden becomes too large so that the bacterium’s fitness is decreased in particular environments. The reduced fitness effects for the host include increased biosynthetic burden, reduced translational efficiency, impaired chromosomal replication, and other energetic costs (Shachrai et al. 2010; Baltrus 2013; Vogwill and Maclean 2015; San Millan et al. 2018). These fitness effects can be especially problematic for larger plasmids. However, plasmid expression and survival is possible if other factors are able to overcome the negative fitness effects of the plasmid. One of the most common explanations for the survival and expression of a plasmid is in an environment with enough selective pressure to give the host an advantage (Bergstrom et al. 2000; Simonsen 2018). Selective pressures are often essential for plasmid transfer as well because of their necessity in long-term survival of the plasmid; however, the type and amount of pressure required depends on the plasmid. For example, DiGiovanni et al. (1996) found that the contaminant 2,4-D, in which the harbored plasmid could degrade, was sufficient pressure to promote conjugal transfer. Contrarily, theoretical analysis has often suggested that fast transfer rate could possibly compensate for the fitness cost of a plasmid and prevent its loss (Andreoni and Gianfreda 2007; De Gelder et al. 2007). Recently, studies have experimentally shown that high transfer rates are able to overcome the metabolic burden and fitness costs of antibiotic resistance plasmids (Svara and Rankin 2011; Lopatkin et al. 2017). However, because large catabolic plasmids exhibit a greater burden on the host cell than smaller, antibiotic resistance plasmids, it is yet to be determined if fast transfer rates can overcome these costs to benefit genetic bioaugmentation. Additionally, the large metabolic burden of degradative plasmids and the necessity for selective pressure lessons the chances of plasmid survival in the environment after full degradation of the pollutant.

Plasmids can benefit the host in multiple other ways besides the direct effect of giving the host a competitive advantage in a selective environment which can lead to the expression and survival of plasmids without these selective pressures. Plasmids can co-evolve with hosts in as little as fifty generations due to mutations in regulatory genes. This plasmid-host co-evolution is likely why some plasmids persist in particular hosts for many years, yet the mechanisms and mutations contributing to this are poorly understood (Harrison et al. 2015; MacLean and San Millan 2015). Plasmid persistence can also be explained by ‘‘plasmid hitchhiking” which is a phenomenon where plasmids transfer into already fit organisms (Bergstrom et al. 2000). These fitness benefits of an antibiotic resistance IncP plasmid have been confirmed in complex communities (Li et al. 2020). However, not one model has been identified that universally describes these associations likely due to variations between phylotypes.

Moving forward

Horizontal gene transfer via conjugation has contributed to the tremendous diversity of prokaryotes. This naturally occurring phenomenon has beneficial attributes that can be utilized by environmental engineers into biomedical and environmental applications such the spread of xenobiotic-degrading genes via catabolic plasmid transfer. Utilizing conjugation for bioremediation has the potential for long-term degradation of toxic pollutants that is more cost-effective and environmentally friendly than traditional remediation methods. Although this technology is promising it is clear that researchers, consultants, and public health professionals need a full understanding of factors contributing to plasmid transfer in order to harness it for beneficial use. Understanding these properties will allow researchers to advance bioremediation technologies that promote plasmid transfer and expression of degradation genes.

Researchers have begun to investigate these properties affecting conjugation of catabolic plasmids, yet knowledge gaps remain. First, many studies have been performed with smaller antibiotic resistance plasmids. Larger degradative plasmids relevant for genetic bioaugmentation have different properties and effects on host metabolism which could greatly affect plasmid transfer and persistence in the environment. Because of this, it is still unclear whether fast catabolic transfer rates can overcome metabolic costs to benefit genetic bioaugmentation.

Studies focused on catabolic plasmids rather than antibiotic resistant plasmids have increased knowledge of plasmid transfer and expression; however, these studies are often limited to only testing one or two variables and their impact on conjugation (Table 1). There is insufficient evidence for the aggregate impact of various abiotic properties (such as moisture, temperature, and pH) as well as the impact of compounded abiotic and biotic properties. This is particularly important to enhance genetic bioaugmentation strategies because of the heterogeneous conditions and complexity of the microbial communities that exist in soils and sediments. Therefore, more cohesive studies investigating the impact of the composition of microbial communities, growth strategies of organisms, and nutrient availability on conjugation occurrence and contaminant degradation are required to untangle these complexities. Additionally, moving these lab-scale studies to the field requires an understanding of the overall community structure which is absent in current applications. Successful translation into field methods will require a fuller understanding of the ecological complexity of conjugation systems as well as an understanding of the effects of conditions on these communities.

Table 1.

Findings from studies that have investigated the impact of specific abiotic or biotic properties on catabolic plasmid transfer and expression

| Property | Plasmid | Contaminant | Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soil moisture | pDOD | DDT | Number of transconjugants and amount of DDT degraded highest at 60% soil moisture | Gao et al. (2015) |

| pCAR1 | carbazole | Number of transconjugants and amount of carbazole degraded highest at 100% soil moisture compared to 67% | Shintani et al. (2008) | |

| pDOC | chlorpyrifos | Number of transconjugants and amount of chlorpyrifos degraded highest at 60% soil moisture | Zhang et al. (2012) | |

| Temperature | pDOD | DDT | Number of transconjugants and amount of DDT degraded highest at 30 °C | Gao et al. (2015) |

| pDOC | chlorpyrifos | Number of transconjugants and amount of chlorpyrifos degraded highest at 30 °C | Zhang et al. (2012) | |

| TOL-like | phenol | Number of transconjugants highest at 35 °C | Wang et al. (2014) | |

| pRO103 | 2,4-D | Number of transconjugants highest at 29 °C | Johnsen and Kroer (2007) | |

| Nutrients | pCAR1 | carbazole | Number of transconjugants and amount of carbazole degraded not affected by nutrient addition | Shintani et al. (2008) |

| TOL-like | phenol | Highest degradation and transconjugant occurrence at highest levels of LB dilutions | Wang et al. (2014) | |

| pWW0 TOL | toluene | Increase in conjugation with an increase in nutrients up to 10 mM | Seoane et al. (2010) | |

| Contaminant concentration | pJP4 | 2,4-D | Conjugation and 2,4-D degradation occurred with 1000 μg of 2,4-D present | DiGiovanni et al. (1996) |

| pWW0 TOL | toluene | The presence of toluene as a selective pressure was not enough to promote conjugation | Ikuma and Gunsch (2012) | |

| TOL-like | phenol | Number of transconjugants increased with increasing phenol concentrations and remained unchanged between 150–300 mg/kg of phenol | Wang et al. (2014) | |

| pDOC | chlorpyrifos | Number of transconjugants and amount of chlorpyrifos degraded increased with concentrations of chlorpyrifos added | Zhang et al. (2012) | |

| Alternative carbon sources | pWW0 TOL | toluene | Addition of glucose had limited affect on conjugation but increased degradation of toluene in transconjugants | Ikuma et al. (2012) |

| pRO103 | 2,4-D | Addition of maltose increased plasmid transfer up to 0.125 mM | Johnsen and Kroer (2007) | |

| G+C content | pWW0 TOL | toluene | Toluene degradation varied with G+C content of the transconjugants; when glucose was added, there was a negative correlation between toluene degradation and G+C content | Ikuma and Gunsch (2012) |

| pWW0 TOL | toluene | Toluene degradation increased with increasing G+C contents, likely because of similarity to the G+C content of the plasmid | Ikuma and Gunsch (2013) | |

| Bacterial Growth Rates | TOL | toluene | Plasmid transfer rate increased with increasing specific growth rate of the donor | Smets et al. (1993) |

| pWW0 TOL | toluene | Plasmid transfer increased as the recipient growth stage increased | Seoane et al. (2010) |

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under grant no. DGE-1644868 and the National Institute of Health under grant no. P42ES010356.

Funding

This work is supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under grant no. DGE-1644868 and the National Institute of Health under grant no. P42ES010356.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors declare that they have no have conflict of interests.

Ethical approval This review is original and has not been submitted or published for simultaneous consideration.

Consent to participate The authors consent to participation in this work.

Consent for publication The authors consent to publication of this work.

Availability of data and materials

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- Alanis AJ (2005) Resistance to antibiotics: are we in the postantibiotic era? Arch Med Res 36:697–705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alderliesten JB, Duxbury SJN, Zwart MP et al. (2020) Effect of donor-recipient relatedness on the plasmid conjugation frequency: a meta-analysis. BMC Microbiol. 10.1186/s12866-020-01825-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aminov RI (2011) Horizontal gene exchange in environmental microbiota. Front Microbiol 2:158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreoni V, Gianfreda L (2007) Bioremediation and monitoring of aromatic-polluted habitats. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 76:287–308. 10.1007/s00253-007-1018-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atlas RM, Bartha R (1997) Microbial ecology: fundamentals and applications, 4th edn. Benjamin Cummings, San Francisco [Google Scholar]

- Baltrus DA (2013) Exploring the costs of horizontal gene transfer. Trends Ecol Evol 28:489–495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergstrom CT, Lipsitch M, Levin BR (2000) Natural selection, infectious transfer and the existence conditions for bacterial plasmids. Genetics 155:1505–1519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleakley BH, Crawford DL (1989) The effect of varying moisture and nutrient levels on the transfer of a conjugative plasmid between Streptomyces species in soil Fungal Growth on Soil Substances View project. The potential effects of woodchip bioreactors on transporting microbes. Can J Microbiol. 10.1139/m89-086 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brzeszcz J, Steliga T, Kapusta P et al. (2016) r-strategist versus K-strategist for the application in bioremediation of hydrocarbon-contaminated soils. Int Biodeterior Biodegrad 106:41–52. 10.1016/j.ibiod.2015.10.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli LL, Lederberg J, Lederberg EM (1953) An infective factor controlling sex compatibility in Bacterium coli. J Gen Microbiol 8:89–103. 10.1099/00221287-8-1-89 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- César CE, Machón C, De La Cruz F, Llosa M (2006) A new domain of conjugative relaxase TrwC responsible for efficient oriT-specific recombination on minimal target sequences. Mol Microbiol 62:984–996. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05437.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christie PJ, Cascales E (2009) Structural and dynamic properties of bacterial Type IV secretion systems (Review). Mol Membr Biol 22:51–61. 10.1080/09687860500063316 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Datta N Hedges RW(1973) R factors of compatibility group A. J Gen Microbiol 74:335–337. 10.1099/00221287-74-2-335 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gelder L, Ponciano JM, Joyce P, Top EM (2007) Stability of a promiscuous plasmid in different hosts: No guarantee for a long-term relationship. Microbiology 153:452–463. 10.1099/mic.0.2006/001784-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DiGiovanni GD, Neilson JW, Pepper IL, Sinclair NA (1996) Gene transfer of Alcaligenes eutrophus JMP134 plasmid pJP4 to indigenous soil recipients. Appl Environ Microbiol 62:2521–2526. 10.1128/aem.62.7.2521-2526.1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Draper O, César CE, Machón C et al. (2005) Site-specific recombinase and integrase activities of a conjugative relaxase in recipient cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102:16385–16390. 10.1073/pnas.0506081102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elsas JD, Bailey MJ (2006) The ecology of transfer of mobile genetic elements. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 42:187–197. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb01008.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Astorga A, Muela A, Cisterna R et al. (1992) Biotic and abiotic factors affecting plasmid transfer in Escherichia coli strains. Appl Environ Microbiol 58:392–398 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lopez R, de Toro M, Moncalian G et al. (2016) Comparative genomics of the conjugation region of F-like plasmids: five shades of F. Front Mol Biosci. 10.3389/fmolb.2016.00071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez-Lopez R, Redondo S, Garcillan-Barcia MP, de la Cruz F (2017) Towards a taxonomy of conjugative plasmids. Curr Opin Microbiol 38:106–113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierer N (2017) Embracing the unknown: disentangling the complexities of the soil microbiome. Nat Publ Gr. 10.1038/nrmicro.2017.87 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fierer N, Bradford MA, Jackson RB (2007) Toward an ecological classification of soil bacteria. Ecology 88:1354–1364. 10.1890/05-1839 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Firth N, Ippen-ihler K, Skurray RA (1996) Structure and function of the F factor and mechanism of conjugation Escherichia coli Salmonella typhimurium. Cell Mol Biol 126:2377–2401 [Google Scholar]

- Forns N, Baños RC, Balsalobre C et al. (2005) Temperature-dependent conjugative transfer of R27: role of chromosome-and plasmid-encoded Hha and H-NS proteins. J Bacteriol 187:3950–3959. 10.1128/JB.187.12.3950-3959.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox RE, Zhong X, Krone SM, Top EM (2008) Spatial structure and nutrients promote invasion of IncP-1 plasmids in bacterial populations. ISME J 2:1024–1039. 10.1038/ismej.2008.53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fricke WF, Welch TJ, McDermott PF et al. (2009) Comparative genomics of the IncA/C multidrug resistance plasmid family. J Bacteriol 191:4750–4757. 10.1128/JB.00189-09 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost LS, Ippen-Ihler K, Skurray RA (1994) Analysis of the sequence and gene products of the transfer region of the F sex factor. Microbiol Rev 58:162–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frost LS, Leplae R, Summers AO, Toussaint A (2005) Mobile genetic elements: the agents of open source evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol 3:722–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furste JP, Pansegrau W, Ziegelin G et al. (1989) Conjungative transfer of promiscuous IncP plasmids: interaction of plasmid-encoded products with the transfer origin. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 86:1771–1775. 10.1073/pnas.86.6.1771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao C, Jin X, Ren J et al. (2015) Bioaugmentation of DDT-contaminated soil by dissemination of the catabolic plasmid pDOD. J Environ Sci (china) 27:42–50. 10.1016/j.jes.2014.05.045 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garbisu C, Garaiyurrebaso O, Epelde L et al. (2017) Plasmid-mediated bioaugmentation for the bioremediation of contaminated soils. Front Microbiol 8:1966. 10.x3389/fmicb.2017.01966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcillán-Barcia MP, Jurado P, González-Pérez B et al. (2007) Conjugative transfer can be inhibited by blocking relaxase activity within recipient cells with intrabodies. Mol Microbiol 63:404–416. 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05523.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gogarten JP, Townsend JP (2005) Horizontal gene transfer, genome innovation and evolution. Nat Rev Microbiol 3:679–687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grohmann E, Muth G, Espinosa M (2003) Conjugative plasmid transfer in Gram-positive bacteria. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev 67:277–301. 10.1128/mmbr.67.2.277-301.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gullberg E, Albrecht LM, Karlsson C et al. (2014) Selection of a multidrug resistance plasmid by sublethal levels of antibiotics and heavy metals. Mbio. 10.1128/mBio.01918-14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haase J, Lurz R, Grahn AM et al. (1995) Bacterial conjugation mediated by plasmid RP4: RSF1010 mobilization, donor-specific phage propagation, and pilus production require the same Tra2 core components of a proposed DNA transport complex. J Bacteriol 177:4779–4791. 10.1128/jb.177.16.4779-4791.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall JPJ, Wood AJ, Harrison E, Brockhurst MA (2016) Source-sink plasmid transfer dynamics maintain gene mobility in soil bacterial communities. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 113:8260–8265. 10.1073/pnas.1600974113 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison E, Guymer D, Spiers AJ et al. (2015) Parallel compensatory evolution stabilizes plasmids across the parasitism-mutualism continuum. Curr Biol 25:2034–2039. 10.1016/j.cub.2015.06.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes F (2003) The function and organization of plasmids. Methods Mol Biol 235:1–17. 10.1385/1-59259-409-3:1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Headd B, Bradford SA (2018) Physicochemical factors that favor conjugation of an antibiotic resistant plasmid in non growing bacterial cultures in the absence and presence of antibiotics. Front Microbiol 9:2122. 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02122 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikuma K, Gunsch CK (2012) Genetic bioaugmentation as an effective method for in situ bioremediation: functionality of catabolic plasmids following conjugal transfers. Bioengineered 3:236–241. 10.4161/bbug.20551 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikuma K, Gunsch CK (2013) Functionality of the TOL plasmid under varying environmental conditions following conjugal transfer. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 97:395–408. 10.1007/s00253-012-3949-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ikuma K, Holzem RM, Gunsch CK (2012) Impacts of organic carbon availability and recipient bacteria characteristics on the potential for TOL plasmid genetic bioaugmentation in soil slurries. Chemosphere 89:158–163. 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2012.05.086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnsen AR, Kroer N (2007) Effects of stress and other environmental factors on horizontal plasmid transfer assessed by direct quantification of discrete transfer events. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 59:718–728. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2006.00230.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy N, Beutin L, Achtman M et al. (1977) Conjugation proteins encoded by the F sex factor. Nature 270:580–585. 10.1038/270580a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klappenbach JA, Dunbar JM, Schmidt TM (2000) rRNA operon copy number reflects ecological strategies of bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 66:1328–1333. 10.1128/AEM.66.4.1328-1333.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottara A, Hall JPJ, Harrison E, Brockhurst MA (2018) Variable plasmid fitness effects and mobile genetic element dynamics across Pseudomonas species. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 94:172. 10.1093/femsec/fix172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Król JE, Nguyen HD, Rogers LM et al. (2011) Increased transfer of a multidrug resistance plasmid in Escherichia coli biofilms at the air-liquid interface. Appl Environ Microbiol 77:5079–5088. 10.1128/AEM.00090-11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar CC, Novick RP (1985) Plasmid pT181 replication is regulated by two countertranscripts. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 82:638–642. 10.1073/pnas.82.3.638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lafuente R, Maymó-Gatell X, Mas-Castellá J, Guerrero R (1996) Influence of environmental factors on plasmid transfer in soil microcosms. Curr Microbiol 32:213–220 [Google Scholar]

- Lanka E, Wilkins BM (1995) DNA processing reactions in bacterial conjugation. Annu Rev Biochem 64:141–169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawley TD, Klimke WA, Gubbins MJ, Frost LS (2003) F factor conjugation is a true type IV secretion system. FEMS Microbiol Lett 224:1–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Dechesne A, Madsen JS et al. (2020) Plasmids persist in a microbial community by providing fitness benefit to multiple phylotypes. ISME J 14:1170–1181. 10.1038/s41396-020-0596-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Light J, Molin S (1982) The sites of action of the two copy number control functions of plasmid R1. MGG Mol Gen Genet 187:486–493. 10.1007/BF00332633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopatkin AJ, Meredith HR, Srimani JK et al. (2017) Persistence and reversal of plasmid-mediated antibiotic resistance. Nat Commun. 10.1038/s41467-017-01532-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLean RC, San Millan A (2015) Microbial evolution: towards resolving the plasmid paradox. Curr Biol 25:R764–R767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Megharaj M, Ramakrishnan B, Venkateswarlu K et al. (2011) Bioremediation approaches for organic pollutants: a critical perspective. Environ Int. 10.1016/j.envint.2011.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller MN, Stratton GW, Murray G (2004) Effects of soil moisture and aeration on the biodegradation of pentachlorophenol contaminated soil. Bull Environ Contam Toxicol 72:101–108. 10.1007/s00128-003-0246-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mrozik A, Piotrowska-Seget Z (2010) Bioaugmentation as a strategy for cleaning up of soils contaminated with aromatic compounds. Microbiol Res 165:363–375. 10.1016/j.micres.2009.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulligan ME, Mcclure WR (1986) Analysis of the occurrence of promoter-sites in DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 14:109–126. 10.1093/nar/14.1.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarre WW, McClelland M, Libby SJ, Fang FC (2007) Silencing of xenogeneic DNA by H-NS - Facilitation of lateral gene transfer in bacteria by a defense system that recognizes foreign DNA. Genes Dev 21:1456–1471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navarre WW, Porwollik S, Wang Y et al. (2006) Selective silencing of foreign DNA with low GC content by the H-NS protein in Salmonella. Science 313:236–238. 10.1126/science.1128794 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick RP (1987) Plasmid incompatibility. Microbiol Rev 51:381–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Novick RP, Hoppensteadt FC (1978) On plasmid incompatibility. Plasmid 1:421–434. 10.1016/0147-619X(78)90001-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Brien TF (2002) Emergence, spread, and environmental effect of antimicrobial resistance: how use of an antimicrobial anywhere can increase resistance to any antimicrobial anywhere else. Clin Infect Dis 34:S78–S84. 10.1086/340244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz-Álvarez R et al. (2018) Consistent changes in the taxonomic structure and functional attributes of bacterial communities during primary succession. ISME J. 10.1038/s41396-018-0076-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce DA, Bazin MJ, Lynch JM (2008) Substrate concentration and plasmid transfer frequency between bacteria in a model rhizosphere. Microbiol Ecol 40:2357–2368. 10.1016/B978-008045405-4.00519-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinedo CA, Smets BF (2005) Conjugal TOL transfer from Pseudomonas putida to Pseudomonas aeruginosa: effects of restriction proficiency, toxicant exposure, cell density ratios, and conjugation detection method on observed transfer efficiencies. Appl Environ Microbiol 71:51–57. 10.1128/AEM.71.1.51-57.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Popa O, Hazkani-Covo E, Landan G et al. (2011) Directed networks reveal genomic barriers and DNA repair bypasses to lateral gene transfer among prokaryotes. Genome Res 21:599–609. 10.1101/gr.115592.110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roller BRK, Stoddard SF, Schmidt TM (2016) Exploiting rRNA operon copy number to investigate bacterial reproductive strategies. Nat Microbiol 1:1–7. 10.1038/nmicrobiol.2016.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- San Millan A, Toll-Riera M, Qi Q et al. (2018) Integrative analysis of fitness and metabolic effects of plasmids in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. ISME J 12:3014–3024. 10.1038/s41396-018-0224-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santos SR, Ochman H (2004) Identification and phylogenetic sorting of bacterial lineages with universally conserved genes and proteins. Environ Microbiol 6:754–759. 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2004.00617.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seoane J, Yankelevich T, Dechesne A et al. (2010) An individual-based approach to explain plasmid invasion in bacterial populations. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 75:17–27. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.00994.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shachrai I, Zaslaver A, Alon U, Dekel E (2010) Cost of unneeded proteins in E. coli is reduced after several generations in exponential growth. Mol Cell 38:758–767. 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shintani M, Matsui K, Takemura T et al. (2008) Behavior of the IncP-7 carbazole-degradative plasmid pCAR1 in artificial environmental samples. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 80:485–497. 10.1007/s00253-008-1564-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simonsen L (2018) The existence conditions for bacterial plasmids: theory and reality. Microbiol Ecol 22:187–205 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smets BF, Rittmann BE, Stahl DA (1993a) The specific growth rate of Pseudomonas putida PAW1 influences the conjugal transfer rate of the TOL plasmid. Appl Environ Microbiol 59:3430–3437. 10.1128/aem.59.10.3430-3437.1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sørensen SJ, Bailey M, Hansen LH et al. (2005) Studying plasmid horizontal transfer in situ: a critical review. Nat Rev Microbiol 3:700–710. 10.1038/nrmicro1232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stalder T, Top E (2016) Plasmid Transfer in biofilms: a perspective on limitations and opportunities. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes. 10.1038/npjbiofilms.2016.22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svara F, Rankin DJ (2011) The evolution of plasmid-carried antibiotic resistance. BMC Evol Biol 11:130. 10.1186/1471-2148-11-130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sysoeva TA, Kim Y, Rodriguez J et al. (2019) Growth-stage-dependent regulation of conjugation. AIChE J 66:1–10. 10.1002/aic.16848 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas CM, Nielsen KM (2005) Mechanisms of, and barriers to, horizontal gene transfer between bacteria. Nat Rev Microbiol 3:711–721. 10.1038/nrmicro1234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thompson IP, Van Der Gast CJ, Ciric L, Singer AC (2005) Bioaugmentation for bioremediation: the challenge of strain selection. Environ Microbiol 7:909–915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomizawa J, Itoh T, Selzer G, Som T (1981) Inhibition of ColE1 RNA primer formation by a plasmid-specified small RNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 78:1421–1425. 10.1073/pnas.78.3.1421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Top EM, Springael D (2003) The role of mobile genetic elements in bacterial adaptation to xenobiotic organic compounds. Curr Opin Biotechnol 14:262–269. 10.1016/S0958-1669(03)00066-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Top EM, Springael D, Boon N (2002) Catabolic mobile genetic elements and their potential use in bioaugmentation of polluted soils and waters. FEMS Microbiol Ecol 42:199–208. 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2002.tb01009.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkata Mohan S, Falkentoft C, Venkata Nancharaiah Y et al. (2009) Bioaugmentation of microbial communities in laboratory and pilot scale sequencing batch biofilm reactors using the TOL plasmid. Bioresour Technol 100:1746–1753. 10.1016/j.biortech.2008.09.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira-Silva S, Rocha EPC (2010) The systemic imprint of growth and its uses in ecological (meta)genomics. PLoS Genet. 10.1371/journal.pgen.1000808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogwill T, Maclean RC (2015) The genetic basis of the fitness costs of antimicrobial resistance: a meta-analysis approach. Evol Appl 8:284–295. 10.1111/eva.12202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Von Wintersdorff CJH, Penders J, Van Niekerk JM et al. (2016) Dissemination of antimicrobial resistance in microbial ecosystems through horizontal gene transfer. Front Microbiol 7:173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y, Kou S, Jiang Q et al. (2014) Factors affecting transfer of degradative plasmids between bacteria in soils. Appl Soil Ecol 84:254–261. 10.1016/j.apsoil.2014.07.009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham SA, Lynn DH (1990) Relations between growth rate, cell size, and DNA content in colpodean ciliates (Ciliophora: Colpodea). Eur J Protistol 25:345–352. 10.1016/S0932-4739(11)80127-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu L, Yang Y, Chen S et al. (2017) Microbial functional trait of rRNA operon copy numbers increases with organic levels in anaerobic digesters. ISME J 11:2874–2878. 10.1038/ismej.2017.135 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Wang B, Cao Z, Yu Y (2012) Plasmid-mediated bioaugmentation for the degradation of chlorpyrifos in soil. J Hazard Mater 221-222:178–184. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.04.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data analyzed during this study are included in this published article or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.