ABSTRACT

DnaA is the initiator protein of chromosome replication, but the regulation of its homoeostasis in enterobacteria is not well understood. The DnaA level remains stable at different growth rates, suggesting a link between metabolism and dnaA expression. In a bioinformatic prediction, which we made to unravel targets of the sRNA rnTrpL in Enterobacteriaceae, the dnaA mRNA was the most conserved target candidate. The sRNA rnTrpL is derived from the transcription attenuator of the tryptophan biosynthesis operon. In Escherichia coli, its level is higher in minimal than in rich medium due to derepressed transcription without external tryptophan supply. Overexpression and deletion of the rnTrpL gene decreased and increased, respectively, the levels of dnaA mRNA. The decrease of the dnaA mRNA level upon rnTrpL overproduction was dependent on hfq and rne. Base pairing between rnTrpL and dnaA mRNA in vivo was validated. In minimal medium, the oriC level was increased in the ΔtrpL mutant, in line with the expected DnaA overproduction and increased initiation of chromosome replication. In line with this, chromosomal rnTrpL mutation abolishing the interaction with dnaA increased both the dnaA mRNA and the oriC level. Moreover, upon addition of tryptophan to minimal medium cultures, the oriC level in the wild type was increased. Thus, rnTrpL is a base-pairing sRNA that posttranscriptionally regulates dnaA in E. coli. Furthermore, our data suggest that rnTrpL contributes to the DnaA homoeostasis in dependence on the nutrient availability, which is represented by the tryptophan level in the cell.

KEYWORDS: Attenuator, sRNA, target prediction, dnaA, tryptophan

Introduction

Virtually all bacteria have DnaA protein that initiates chromosome replication. DnaA is the master regulator of the initiation and therefore, the regulation of dnaA expression is crucial for the cell [1–3]. In Escherichia coli and other Gammaproteobacteria, the cellular concentration of DnaA is nearly constant in cultures growing with doubling times between 22 and 150 min [4]. It was suggested that RNA-based regulation plays a role in this DnaA homoeostasis [3], but the identities of the riboregulator(s) and the intracellular signal(s) are unknown.

In E. coli, the regulation of the initiation of dnaA transcription, the concentration of the activated DnaA form (ATP-DnaA), its binding to so-called DnaA boxes near oriC, and the DNA unwinding at the origin were intensely studied [2,3,5,6]. In addition to being autoregulated, dnaA transcription also depends on the cell cycle [2]. Furthermore, it is known that the dnaA transcription is inhibited at high (p)ppGpp levels, and that it decreases with a decrease in the growth rate [3,7]. Moreover, it was suggested that the following dnaA mRNA features contribute to the DnaA homoeostasis: 1) it has a GUG start codon, which ensures a relatively low translation efficiency and 2) dnaA mRNA is highly unstable (3.5 min in LB and 1.9 min in minimal medium, respectively) [8]. It was estimated that due to the mentioned mRNA characteristics and the moderate dnaA transcription, each transcript gives on average one molecule DnaA [3]. This, however, suggests that changes in the dnaA mRNA level due to posttranscriptional regulation may strongly influence DnaA production.

Posttranscriptional regulation in bacteria is often mediated by trans-acting, base-pairing small RNAs (sRNAs), which mostly affect the translation and/or the stability of their target mRNAs [9,10]. The majority of the known bacterial sRNAs are generated from orphan genes or 3′-UTRs [11]. In contrast, 5ʹ-UTR derived, trans-acting sRNAs were rarely described [12]. Common source of bacterial, 5ʹ-UTR derived sRNAs are transcription attenuators [13–15], but such sRNAs are usually considered non-functional. Recently, it was shown that in the soil alphaproteobacterium Sinorhizobium meliloti, the attenuator sRNA rnTrpL of the tryptophan (Trp) biosynthesis gene trpE(G) acts in trans by base pairing with target mRNAs [16]. The role of the homologous attenuator sRNA Ec-rnTrpL in E. coli was not analysed yet.

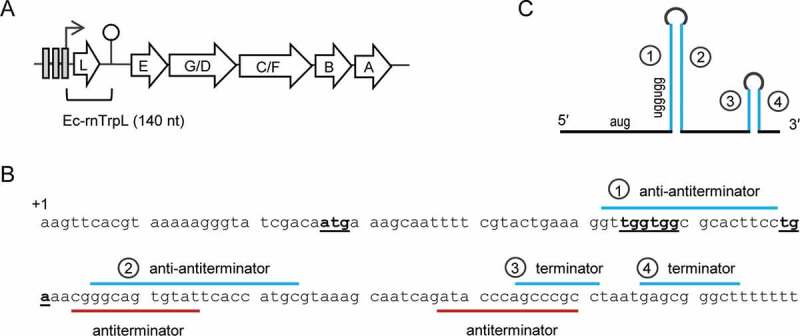

In E. coli and other Enterobacteriaceae members, the Trp biosynthesis genes are organized in a single operon trpEGDCFBA, which is preceded by the small ORF trpL harbouring two consecutive Trp codons. At the transcriptional level, the E. coli trp operon is regulated by a repressor, which binds to operators when the Trp supply is high (Fig. 1A) [17,18], for example when bacteria grow in rich LB medium. In minimal medium, transcription is derepressed; trpL is transcribed and concomitantly translated. Due to the consecutive Trp codons in trpL, the availability of charged tRNATrp, reflecting the cellular Trp availability, determines whether transcription of trpEGDCFBA is attenuated [13,19]. The trp attenuator contains regions 1 to 4, which can undergo alternative base pairing. If the cellular Trp level is extremely low [20], the ribosomes transiently stall at the Trp codons of trpL. This leads to base pairing of regions 2 and 3, which form an antiterminator structure, and the trpEGDCFBA genes are transcribed. If, however, the cellular Trp concentration is sufficient, trpL translation is fast and regions 1 and 2 as well as regions 3 and 4 form stem-loops. In this case, transcription is terminated (attenuated), because the stem-loop formed by regions 3 and 4 is a Rho-independent transcription terminator (Fig. 1) [13]. The trp attenuator helps bacteria to save energy, because Trp is the most costly to synthesize amino acid [19]. Therefore, in prototrophic E. coli growing in minimal medium, trpEGDCFBA transcription is expected to be regularly attenuated, resulting in liberation of the leader transcript (attenuator sRNA) Ec-rnTrpL. Since this attenuation mechanism is conserved in Enterobacteriaceae, it is possible that this leader transcript adopted conserved functions in trans.

Figure 1.

The trp operon and the sRNA Ec-rnTrpL in E. coli. (A) The trpLEGDCFBA operon with indicated operators (grey rectangles), transcription start site (flexed arrow) and attenuation terminator (hairpin). The region corresponding to Ec-rnTrpL is indicated. (B) Sequence of the Ec-rnTrpL gene with indicated trpL ORF (start, Trp and stop codons are in bold and underlined) and base pairing regions involved in the regulation of the trp operon by transcription attenuation are marked. (C) Schematic representation of Ec-rnTrpL, which arises by transcription attenuation. Base pairing regions leading to formation of the anti-antiterminator (1 and 2) and the terminator (3 and 4) are indicated. For details, see (B)

The function of most enterobacterial sRNAs with investigated molecular mechanisms depends on RNA chaperones such as Hfq and ProQ [21,22]. Interestingly, in a recent study with E. coli grown in LB medium, in which UV cross-linking, ligation and sequencing of hybrids (CLASH) were used to detect Hfq-associated RNA-RNA interactions, it was reported that trpL mRNA interacts with hdeD mRNA during the transition growth phase [23]. Since in the case of transcription attenuation the trpL mRNA corresponds to Ec-rnTrpL sRNA, this finding suggests that Ec-rnTrpL is an Hfq-dependent sRNA.

Recent high-throughput studies for experimental detection of sRNAs and their targets, such as the above-mentioned CLASH method, dramatically expanded our knowledge on the sRNA networks in E. coli under specific physiological conditions [21–26]. On the other hand, targets of an sRNA can also be predicted by bioinformatics methods [27]. Although the limited complementarity between an sRNA and its multiple targets poses a challenge for target prediction, the CopraRNA tool, which uses comparative genomics to identify targets of conserved sRNAs, was successfully used in detecting novel sRNA–mRNA interactions [28].

In this work, we used CopraRNA [28] to predict targets of rnTrpL in Enterobacteriaceae. We analysed the mRNA of four candidates in E. coli and found that the mRNA levels of dnaA, sanA and mhpC are affected by the Ec-rnTrpL sRNA. We studied the interaction between Ec-rnTrpL and dnaA mRNA, and provide evidence for a direct posttranscriptional regulation of dnaA by this conserved sRNA. Since the Ec-rnTrpL production depends on the Trp level, our data suggest that Trp could act as an internal signal to link the dnaA expression to the cellular metabolism.

Material and methods

Cultivation of bacteria

E. coli strains (supplementary Table S1) were cultivated in LB or M9 minimal medium with glucose, supplemented with appropriate antibiotics: Tetracycline (Tc, 20 µg/ml), gentamicin (Gm, 10 µg/ml), or ampicillin (Ap, 200 µg/ml). Addition of Trp to the minimal medium is indicated. Liquid cultures of E. coli strains were cultivated in 10 ml medium in a 50 ml Erlenmeyer flask with shaking at 180 rpm at 37°C from an OD600 of 0.02 to an OD600 of 0.2 to 0.4 (indicated), and then processed further.

Plasmid construction for E. coli MG1655

Isolation of total DNA, plasmid purification and cloning procedures were performed according to Sambrook et al. [29]. FastDigest Restriction Endonucleases and Phusion polymerase (Thermo Fischer Scientific) were used for cloning in E. coli JM109 or E. coli DH5α. When pJet1.2/blunt (CloneJet PCR Cloning Kit, Thermo Fischer Scientific) was used for cloning, inserts for IPTG-inducible expression were subcloned into the plasmids pSRKGm or pSRKTc, which contain the lac operators O1 and O3 and ensure tight repression [30]. Insert sequences were analysed by Sanger sequencing with plasmid-specific primers (sequencing service by Microsynth Seqlab, Göttingen, Germany) prior to transformation into the E. coli MG1655 strain. Oligonucleotides used for cloning and site directed mutagenesis are listed in supplementary Table S2.

Plasmids pRS-Ptrp-egfp and pRS-PtrprnTrpL-egfp were constructed as follows. First pRS1 plasmid (a pSRKGm derivative in which the E. coli lacR-lacZYA module was replaced by a NheI-HindIII- XbaI-SpeI-BamHI-PstI-EcoRI multiple cloning site) [31] was used to clone a promoterless egfp between the XbaI and EcoRI restriction sites. A Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence was included in the forward primer (Table S2). Then, the trp promoter region with the three operators (position – 61 to + 10; +1 is the transcription start site) was amplified and the PCR product was cloned between the NheI and XbaI restriction sites upstream of SD-egfp, resulting in pRS-Ptrp-egfp. Similarly, the region from position −61 to position + 140, which includes the trp promoter and the Ec-rnTrpL sequence corresponding to the trp transcription attenuator, was amplified and cloned upstream of SD-egfp, resulting in pRS-PtrprnTrpL-egfp.

Plasmid pSRKTc-Ec-rnTrpL for IPTG-inducible transcription of lacZ′-Ec-rnTrpL was described previously [16]. Plasmid pSRKGm-Ec-rnTrpL was constructed similarly. The Ec-rnTrpL sequence from position + 27 to + 140 (+1 is the transcription start site; position +27 correspond to A of the ATG start codon of the trpL ORF; see Fig. 1B), which was present in plasmid pJet-Ec-rnTrpL, was cleaved out with NdeI and XbaI and inserted into pSRKGm, which was cleaved by the same restriction endonucleases. To introduce mutations M1 and M2 in Ec-rnTrpL, site-directed mutagenesis of pJet-Ec-rnTrpL was performed, and the mutated sRNA sequence was re-cloned in pSRKTc.

To construct pSRKGm-dnaA’-egfp, first the egfp sequence of plasmid pLK64 was amplified from the third to the stop codon [16]. The forward primer contained a BamHI restriction site and codons for a GGGS linker in frame with EGFP, while the reverse primer contained a Hind III restriction site. The PCR product was cloned between the BamHI and HindIII restriction sites of pSRKGm, resulting in pSRKGm-GGGSegfp. Then, the dnaA sequence from the first to the 32th codon was amplified with primers containing the NdeI (forward primer) and BamHI (reverse primer) restriction sites and cloned in pJet1.2, resulting in plasmid pJet-dnaA′. The insert was cleaved out using NdeI and BamHI and cloned in frame with egfp between the NdeI and BamHI restriction sites of pSRKGm-GGGSegfp. The resulting plasmid pSRKGm-dnaA′-egfp allows for IPTG-inducible transcription of dnaA′::egfp mRNA. To introduce compensatory mutation cM1, which restores the interaction with Ec-rnTrpL-M1, pJet-dnaA′ was subjected to site-directed mutagenesis, and the mutated dnaA′-cM1 sequence was re-cloned in pSRKGm-GGGSegfp, resulting in pSRKGm-dnaA′-cM1-egfp.

Construction of gene deletions and chromosomal mutations

An E. coli MG1655 ΔtrpL mutant lacking the Ec-rnTrpL positions from +3 to +142 (+1 is the transcription start site) was constructed as described [32] using the λ red genes for homologous recombination [33]. A chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (cat) gene was amplified using primers with Ec-rnTrpL gene-specific overhangs of 40 bp (Table S2). The PCR product was transformed by electroporation into E. coli MG1655 (pSim5-tet) [34]. After selection on chloramphenicol containing plates (12.5 µg/ml Cm), a ΔtrpL::cat mutant was obtained, which was verified by PCR with primers targeting sequences outside the Ec-rnTrpL gene (Table S2). Then, the ΔtrpL::cat mutant was used for FLP-mediated flipping in the presence of plasmid 709-FLPe (Gene Bridges) to generate the marker-less deletion strain MG1655 ΔtrpL according to the manufacturer’s instructions. M1 and M2 mutations in the chromosomal Ec-rnTrpL gene were constructed using a two-step λ red protocol. First, a cat-sacB fragment was amplified and introduced into the Ec-rnTrpL gene using primers with specific overhangs for recombination (Table S2). Clones were selected on chloramphenicol-containing plates (12.5 µg/ml Cm). In a second λ red step, oligos trpL-M1 and trpL-M2 (Table S2) were used to remove the cat-sacB fragment and to introduce M1 (TGG to ACC) and M2 (GAA to CTT) mutations, respectively. Plates containing 5% sucrose were used for sacB counter-selection. To verify mutations, the Ec-rnTrpL locus was amplified and sequenced. An MG1655 Δhfq::cat mutant was constructed by λ red recombineering as described above. The whole hfq ORF was replaced by a cat gene using primers with specific overhangs for recombination (Table S2). Insertion of the cat gene was verified by PCR.

EGFP fluorescence measurement

Fluorescence of overnight cultures harbouring pRS-Ptrp-egfp or pRS-PtrprnTrpL-egfp was measured using a Tecan Infinite M200 reader. Values were normalized to the ODs measured on the Tecan and to the autofluorescence of the empty vector control.

RNA isolation

RNA was isolated as described [16,31]. Briefly, unless stated otherwise, at OD600 of 0.3, 10 ml culture was filled into tubes with ice rocks (corresponding to a volume of 15 ml) and pelleted by centrifugation at 6,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. RNA was purified using 1 ml TRIzol (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer instructions. After RNA precipitation, an additional hot phenol step was performed to remove residual RNases. RNA concentration and purity were analysed by measuring absorbance at 260 nm and 280 nm, and a 10% polyacrylamide-urea gels and staining with ethidium bromide were used to control the integrity of the isolated RNA.

RNA isolation from the rne mutant

To compare the influence of lacZ’-Ec-rnTrpL production on dnaA mRNA in thermosensitive rne mutant N3431 (rnets) to that in the isogenic parental strain N3433 (rne+), it was necessary to inactivate the mutated RNase E at 42°C prior to IPTG addition [35]. Cultures grown in LB medium to OD 0.3 were shifted to 42°C. Ten minutes thereafter, 1 mM IPTG was added to induce sRNA transcription. Three minutes after IPTG addition, cells were harvested and RNA was isolated.

Northern blot analysis

Total RNA (10 µg) was denatured in urea-formamide containing loading buffer at 65°C, placed on ice and loaded on 1 mm thick, 20 × 20 cm, 10% polyacrylamide-urea gel. Separation by electrophoresis in TBE buffer was performed at 300 V for 4 h. The RNA was transferred to a positively charged nylon membrane for 2 h at 100 mA using a Semi-Dry Blotter. After crosslinking of the RNA to the membrane by UV light, the membrane was pre-hybridized for 2 h at 56°C with a buffer containing 6× SSC, 2.5× Denhardts solution, 1% SDS and 10 µg/ml Salmon Sperm DNA. Hybridization was performed with radioactively labelled oligonucleotides (Table S2) in a solution containing 6× SSC, 1% SDS, 10 µg/ml Salmon Sperm DNA for at least 6 h at 56°C. The membranes were washed twice for 2 to 5 min in 0.01% SDS, 5× SSC at room temperature. Signal detection was performed with a Bio-Rad molecular imager and the Quantity One (Bio-Rad) software. For quantification, the intensity of the sRNA bands was normalized to the intensity of the 5S rRNA. For re-hybridization, membranes were stripped for 20 min at 96°C in 0.1% SDS.

Radiolabeling of oligonucleotides

5′-labelling of 10 pmol oligonucleotide was performed with 5 U T4 polynucleotide kinase (PNK) and 15 µCi [γ-32P]-ATP in 10 µl reaction mixture containing buffer A provided by the manufacturer. The reaction mixture was incubated for 60 min at 37°C. After adding of 30 µl water, unincorporated nucleotides were removed using MicroSpin G-25 columns.

qRT-PCR analysis

The quantitative (real time) reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) analysis of RNA was conducted as previously described [16]. Briefly, to remove residual DNA from the RNA samples, 10 µg RNA was incubated with 1 µl TURBO-DNase for 30 minutes. PCR with rpoB-specific primers was performed for each sample, to test whether DNA is still present. The DNA-free RNA was then diluted to a concentration of 20 ng/µl for the qRT-PCR analysis, which was conducted as previously described using Brilliant III Ultra Fast SYBR® Green QRT-PCR Mastermix (Agilent) and a spectrofluorometric thermal cycler (Bio-Rad). The quantification cycle (Cq), was set to a cycle at which the curvature of the amplification is maximal. As a reference gene for determination of changes in the steady-state mRNA levels after induction of Ec-rnTrpL production, rpoB (encodes the β subunit of RNA polymerase) was used. To compare the steady-state levels of mRNAs (including the rpoB mRNA) between the WT and the ΔtrpL mutant, a rrp41 spike in control was used as a reference gene. For this, a 740 bp part of the rrp41 gene of the archaeon Sulfolobus solfataricus [36] was amplified. A T7 promoter sequence was integrated in the forward primer, and the PCR product was used for in vitro transcription as described [16]. The purified in vitro transcript was diluted to 1 ng/µl, and 1 µl was added to the cells, which were mixed with TRIzol at the begin of the RNA purification. Cq-values of genes of interest and the reference gene were used in the Pfaffl-formula to calculate fold changes of mRNA amounts [37]. Used primer pairs and their efficiencies (as determined by PCR using serial two-fold dilutions of RNA) are listed in Table S2.

sRNA half-life determination

E. coli MG1655 strain was pre-cultivated in M9 minimal medium at 37°C overnight. After dilution to an OD600 of 0.02, a culture was grown to OD600 of 0.3 at 37°C in 100 ml M9 minimal medium in 500 ml Erlenmeyer flasks. Then, rifampicin was added to a final concentration of 50 µg/ml, and the culture was divided in 10 portions (10 ml in a 50 ml Erlenmeyer flask) as fast as possible. They were incubated at 180 rpm and 37°C for the indicated time points (for the 0.5 min time point, the flask was shaken by hand), before the cells were harvested for RNA isolation as described above. After Northern blot analysis with radioactively labelled oligonucleotides complementary to Ec-rnTrpL and the internal control 5S rRNA (Table S2), linear-log graphs were used for half-life calculation.

qPCR for determination of oriC and terC levels

Overnight cultures of strain E. coli MG1655 (pSRKGm) and the deletion mutant E. coli MG1655 ΔtrpL (pSRKGm) were diluted to OD600 of 0.02 and grown to OD600 of 0.2 in M9 minimal medium. Then, cells were harvested, total DNA was purified and diluted to 20 ng/µl. The qPCR analysis was performed using Power SYBR® PCR Mastermix as specified by the manufacturer. Primers targeting sequences located in close proximity to oriC and terC were used (Table S2) [38,39].

Bioinformatic prediction of sRNA targets

We used GLASSgo [40] to find homologs of Ec-rnTrpL in the Proteobacteria taxon with a pairwise identity cut-off of 55%, a maximum allowed E-value of 1 and without structural filtering. We selected 20 homologs including Ec-rnTrpL for CopraRNA [28] sRNA target prediction. We used a slightly modified version of CopraRNA which is available at: https://github.com/JensGeorg/CopraRNA/tree/dev. The input sRNAs with the refseq IDs of the corresponding organisms are listed in supplementary Table S3. The CopraRNA prediction was done based on single organisms IntaRNA [41] predictions allowing for lonely base pairs (default settings), while lonely base pairs were not allowed (–noLP) for the actual interaction site predictions as shown in this study. The initial top 1 target yciV (b1266) was excluded from further analysis, because Ec-rnTrpL is encoded antisense to the 5ʹ region of b1266 which results in a perfect complementarity.

Results

Chromosomal production of the sRNA Ec-rnTrpL in rich and minimal medium

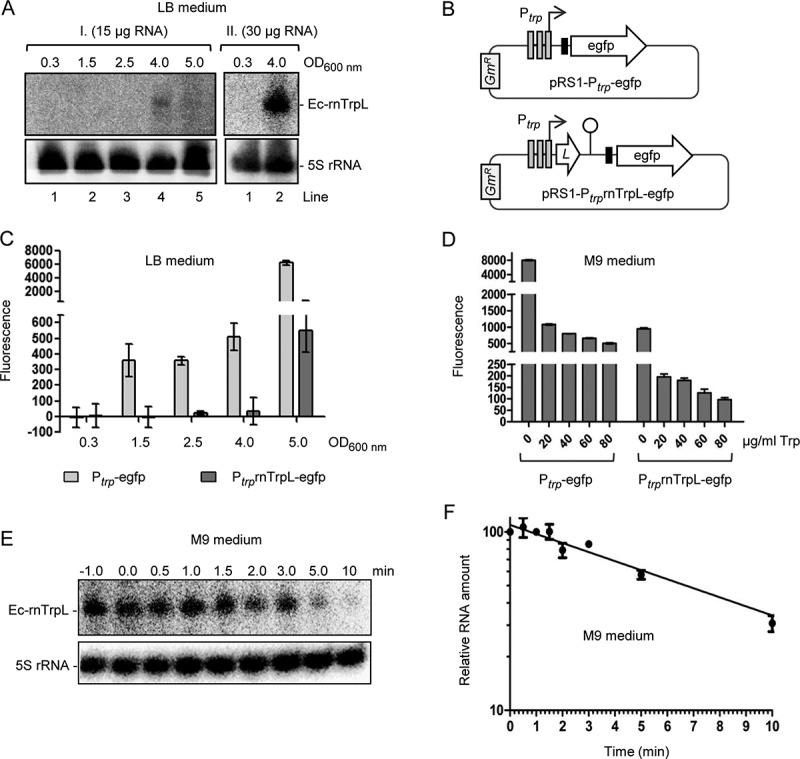

First, we analysed whether Ec-rnTrpL is produced in rich and in minimal medium. When total RNA from exponential E. coli MG1655 cultures grown in LB medium was separated in a 10% polyacrylamide-urea gel and blotted, no signal was detected after hybridization with an Ec-rnTrpL directed probe (Fig. 2A, lanes labelled with 1). This could be expected, because under these conditions (enough Trp supply by the rich medium), transcription of trpLEGDCFBA is repressed. Since previously trpL mRNA (e.g., Ec-rnTrpL) was detected by the Hfq CLASH approach [23] in cells grown in LB medium to the transition phase, we tested whether Ec-rnTrpL is detectable at late growth stages. Indeed, the sRNA was detected in the late transition phase, at an OD of 4.0 (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Analysis of Ec-rnTrpL in rich and minimal media. (A) Northern blot analysis of Ec-rnTrpL in total RNA from cells cultivated in LB to the indicated ODs. Results of two independent experiments (I. and II.) are shown. The loaded RNA amount is given. After hybridization with an Ec-rnTrpL specific probe, the membrane was rehybridized with a probe detecting 5S rRNA (loading control). Detected RNAs are indicated on the right. (B) Schematic representation of the plasmids, which contain egfp reporter fusions and were used to analyse the impact of transcription and attenuation on the trp operon expression. The Shine-Dalgarno sequence upstream of egfp is indicated by a black, small rectangle. GmR, gentamycin resistance. For other details, see Fig. 1A. (C) Fluorescence of cultures harbouring the indicated constructs, which were cultivated in LB medium to the indicated ODs. Normalization to the EVC was performed. (D) Fluorescence of cultures harbouring the indicated constructs, which were cultivated in M9 medium supplemented with Trp (the Trp concentrations are given). (E) Northern blot analysis for determination of the half-life of Ec-rnTrpL in M9 medium without Trp addition. The time after addition of rifampicin is indicated above the panel (in min). Detected RNAs are indicated on the left. A representative blot is shown. For other details see panel (A). For size markers, see Fig. S1. (F) Graphical representation of the results from (E) and an additional, independent experiment. Shown are mean values and standard deviations. The standard deviations at the time points 1 min and 3 min are smaller than the symbol

To analyse the regulation of Ec-rnTrpL production, we used egfp reporter plasmids. In the promoter fusion plasmid pRS1-Ptrp-egfp, the egfp ORF (preceded by a Shine-Dalgarno sequence) is under the control of the promoter of the trp operon (Ptrp) only, while in the promoter-attenuator fusion plasmid pRS1-PtrprnTrpL-egfp, it is under the control of Ptrp and the trp attenuator (Fig. 2B). Strains harbouring one of the plasmids were cultivated in LB medium and fluorescence was measured during growth. As expected, at OD of 0.3 no fluorescence was detected, because transcription from Ptrp is repressed (Fig. 2C). At the ODs 1.5, 2.5 and 4.0, fluorescence was detected in cultures harbouring pRS1-Ptrp-egfp but not in those harbouring pRS1-PtrprnTrpL-egfp, suggesting that at these ODs the Trp concentration was low enough to allow for transcription but not to abolish transcription attenuation. Using pRS1-PtrprnTrpL-egfp, fluorescence was detected at the OD of 5.0, showing that at this growth stage abolishment of transcription attenuation takes place, probably because of strong Trp shortage. Altogether, Fig. 2C suggests that the transcription regulation of the trp operon by repression and attenuation allows for production of the sRNA Ec-rnTrpL in the transition from exponential to stationary growth phase.

We also analysed fluorescence of the strains with the above-mentioned plasmids in M9 medium, to which Trp was added at different concentrations (Fig. 2D). Addition of increasing Trp amounts decreased the fluorescence, in line with promoter repression and transcription attenuation under conditions of Trp availability. Under all tested Trp concentrations, the attenuator caused a drop in fluorescence, indicating transcription termination and thus sRNA Ec-rnTrpL production. As expected, the highest fluorescence was observed using the promoter fusion in M9 medium without Trp addition, confirming promoter derepression. Under these conditions, the attenuator presence led to an 8-fold decrease in fluorescence (Fig. 2D, see bars 0 µg/ml Trp), suggesting Ec-rnTrpL sRNA production. As mentioned in the introduction, transcription attenuation can be expected in minimal medium without Trp supply when prototrophic bacteria are used. Indeed, in total RNA isolated from E. coli MG1655 exponentially growing in M9 medium, the attenuator sRNA was detected by Northern blot hybridization (Fig. 2E and Fig. S1). Under these conditions, the half-life of Ec-rnTrpL was 6 min 40 sec ± 20 sec (Fig. 2F).

Prediction of Ec-rnTrpL targets

CopraRNA target prediction was performed on 20 selected rnTrpL homologs (Tables S3 and S4); the top 10 target candidates are shown in Table 1. A comparison of the actual predicted target sites of the top 4 targets (Fig. 3A) indicates that the dnaA site seems to be fairly conserved, while the other sites seem to be rather E. coli specific (Fig. 3B and 3C, Fig. S2).

Table 1.

Top 10 predicted targets of Ec-rnTrpL, based on the CopraRNA p-value. For each gene, 200 nt upstream and 100 nt downstream of the first nucleotide of the coding region are extracted as 5ʹUTR for target prediction. The interaction site coordinates are given relative to the first nucleotide of the coding region. Positive coordinates indicate interaction in the coding regions. In case of operons, negative numbers might indicate an interaction within the predecessor gene in the operon. 1The upstream gene sanA was tested, in which the interaction site is located; 2mhpC was tested, although the interaction site is located in the upstream gene mhpB (see Fig. 4); NA, not applicable

| p-value | Locustag | Gene | Interaction site borders in mRNA | Experimentally tested | Regulation | Annotation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 6,55E-09 | b3702 | dnaA | +12 to + 87 | yes | negative | chromosomal replication initiator protein DnaA |

| 2,58E-05 | b0905 | ycaO | +70 to +89 | yes | no effect | ribosomal protein S12 methylthiotransferase accessory factor YcaO |

| 5,32E-05 | b2145 | sanA/yeiS | −180 to −142 | yes | negative1 | DUF2542 domain-containing protein YeiS |

| 7,95E-05 | b0349 | mhpB/mhpC | −200 to −177 | yes | positive2 | 2-hydroxy-6-ketonona-2 4-dienedioate hydrolase |

| 0,000186 | b2182 | bcr | −74 to −20 | no | NA | multidrug efflux pump Bcr |

| 0,000189 | b0661 | miaB | −200 to −185 | no | NA | isopentenyl-adenosine A37 tRNA methylthiolase |

| 0,000368 | b3052 | rfaE | −95 to −87 | no | NA | fused heptose 7-phosphate kinase/heptose 1-phosphate adenyltransferase |

| 0,000433 | b2465 | tktB | −178 to −169 | no | NA | transketolase 2 |

| 0,000488 | b1888 | cheA | −1 to +6 | no | NA | chemotaxis protein CheA |

| 0,000766 | b2808 | gcvA | −142 to −118 | no | NA | DNA-binding transcriptional dual regulator GcvA |

Figure 3.

Prediction of rnTrpL targets in Enterobacteriaceae reveals dnaA mRNA as most conserved candidate. (A) Heatmap showing the predicted target and interaction site conservation for the four investigated targets. The columns are clustered based on a 16S rRNA tree. Matching colours within a row indicate the same predicted interaction site, grey indicates no site conservation and white that no homolog was detected in the respective organism. A fill in the lower triangle corresponds to the optimal predicted interaction and in the upper triangle to the first suboptimal prediction. (B) Interaction probability landscape for the most likely dnaA/rnTrpL nucleotide pairs. A distinct peak represents a conserved interaction site starting 29 nt 3ʹ of the first nucleotide of the start codon indicated by an arrow. The landscape is drawn based on the individual organism IntaRNA predictions mapped to the multiple sequence alignments of dnaA and rnTrpL. (C) Partial multiple sequence alignment of the investigated dnaA homologs. The predicted interaction regions are highlighted in green if belonging to the conserved site, otherwise in grey

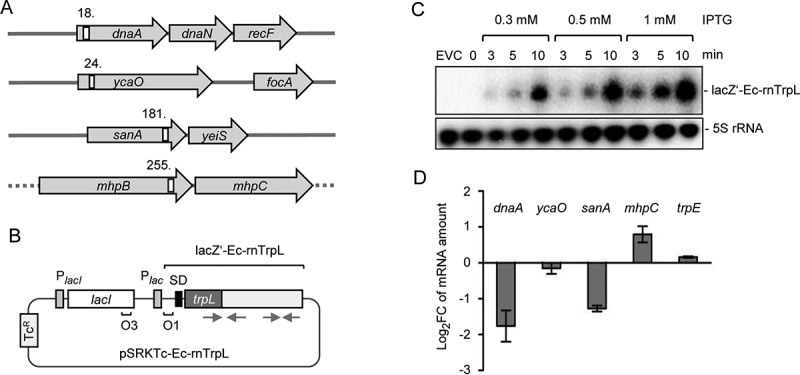

Ec-rnTrpL overproduction influences the mRNA levels of predicted targets

The top four predicted targets of Ec-rnTrpL in E. coli are dnaA (encoding the chromosomal replication initiator protein), ycaO (encoding a ribosomal protein S12 methylthiotransferase accessory factor), sanA (inner membrane protein which is likely to be involved in cell envelope barrier functions), and mhpB (3-carboxyethylcatechol 2,3-dioxygenase). Their genomic loci and the positions of the putative Ec-rnTrpL binding sites are shown in Fig. 4A. We decided to test whether the mRNA levels of dnaA, ycaO, sanA and mhpC (which is in an operon with mhpB) change after induction of sRNA overproduction, since this would suggest an interaction between the sRNA and the respective mRNA. For this, we used plasmid pSRKTc-Ec-rnTrpL (Fig. 4B), which allows for a tight control of IPTG-inducible transcription of a lacZ′-Ec-rnTrpL derivative harbouring the lacZ 5′-UTR instead of the trpL 5′-UTR. This plasmid should be useful, because the proposed interactions (Fig. S3) did not include the 5′-UTR of trpL.

Figure 4.

Induced Ec-rnTrpL overproduction affects the levels of three predicted target mRNAs. (A) Schematic representation of the localization of the putative interaction sites of Ec-rnTrpL in the analysed, predicted targets. Annotated genes are indicated by grey arrows and the putative interaction sites by white rectangles. The numbers indicate the codon at which the predicted interaction starts (see also Fig. 6A and Fig. S3). The grey horizontal line indicates chromosomal DNA; the dashed line indicates that mhpB and mhpC are part of a larger operon harbouring upstream and downstream genes. (B) Schematic representation of the tetracycline-resistance (TcR) plasmid used for IPTG-inducible production of lacZ′-Ec-rnTrpL. The promoter of the repressor gene lacI and the lac promoter are indicated by grey rectangles, the lacZ Shine-Dalgarno sequence by a black rectangle, the operators O1 and O3 are also indicated. The cloned Ec-rnTrpL sequence starts with ATG of trpL and ends with the transcription terminator (positions 27–140, see Fig. 1B). The grey arrows indicate the sRNA regions that base pair to form the anti-antiterminator and the terminator stem-loops (compare to Fig. 1). (C) Northern blot analysis of induced lacZ′-Ec-rnTrpL production in LB medium. Used IPTG concentrations and the induction time are indicated. EVC, empty vector control. After hybridization with an Ec-rnTrpL specific probe, the membrane was rehybridized with a probe detecting 5S rRNA (loading control). A representative blot is shown. (D) Analysis by qRT-PCR of changes in the levels of the indicated mRNAs upon Ec-rnTrpL induction in LB medium. The levels at 3 min after IPTG addition were compared to the levels before addition of IPTG (0 min). A control experiment with the EVC revealed no decrease in the mRNA levels of dnaA and sanA (Fig. S4). The rpoB gene was used as a reference. Shown are means and standard deviations from three independent experiments

Overproduction of the sRNA was conducted in LB cultures. Fig. 4C shows that using Northern blot hybridization, lacZ′-Ec-rnTrpL was not detectable in the overexpressing strain before IPTG addition. However, already 3 minutes (min) post induction with three different IPTG concentrations, lacZ′-Ec-rnTrpL sRNA was detected, and its level increased with the induction time (Fig. 4C). To avoid artefacts due to high overproduction levels and/or long induction that might cause secondary effects, we decided to use 1 mM IPTG for 3 min. Three min post induction, the levels of dnaA and sanA mRNAs were decreased, and that of mhpC mRNA was increased, when compared to the levels before induction (Fig. 4D). The mRNA levels of ycaO and the control mRNA trpE were not changed. The strongest change was observed for the dnaA mRNA level. Since the DnaA protein is necessary for initiation of chromosome replication, this implies that Ec-rnTrpL could be involved in the regulation of this central process in the cell. Therefore, we focused our further analysis on dnaA.

In a control experiment, we observed that the dnaA mRNA level was not decreased if IPTG was added to the EVC culture (Fig. S4), thus confirming that the Ec-rnTrpL production was responsible for the above-described dnaA mRNA decrease. Furthermore, based on previous observations that in S. meliloti some rnTrpL targets were affected in the presence of tetracycline but not gentamycin [42], we additionally constructed the gentamycin resistance plasmid pSRKGm-Ec-rnTrpL. Overproduction of the sRNA from this plasmid also decreased the dnaA mRNA level (Fig. S4), suggesting that this effect does not depend on tetracycline.

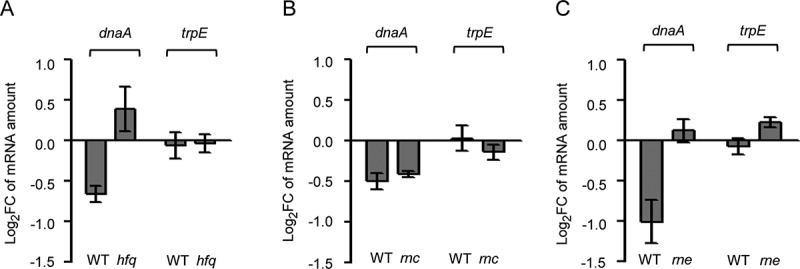

Influence of Ec-rnTrpL on dnaA mRNA depends on hfq and rne

To test whether the decrease in the dnaA mRNA level by overproduction of lacZ’-Ec-rnTrpL depends on the RNA chaperone Hfq, a Δhfq mutant of strain MG1655 was constructed. Transcription of the recombinant sRNA was induced by IPTG in wild type and Δhfq background for 3 min, and changes in the level of dnaA mRNA were analysed by qRT-PCR. Similarly, the importance of the endoribonucleases RNase III and RNase E (encoded by rnc and rne, respectively) for the influence of Ec-rnTrpL on dnaA mRNA was studied using available mutants and their isogenic, parental strains. Fig. 5A shows that while in MG1655 background the induced overproduction of the sRNA decreased the dnaA mRNA level, in the MG1655 Δhfq mutant the dnaA mRNA level was increased. Further, in the rnc mutant and its isogenic, parental strain the dnaA mRNA levels were similarly decreased upon sRNA overproduction (Fig. 5B). Finally, in the rne mutant the dnaA mRNA level was essentially not changed upon sRNA overproduction, although in the isogenic, parental strain it was decreased (Fig. 5C). While in all parental strains and in the Δhfq mutant the levels of the negative control trpE mRNA were not significantly changed upon sRNA overproduction, slight changes were detected in the both RNase mutant strains. In all cases, the results for trpE mRNA were significantly different from the results for dnaA mRNA (Fig. 5). In summary, the data suggest that Hfq and RNase E (but not RNase III) are involved in the action of the sRNA on dnaA mRNA.

Figure 5.

Downregulation of dnaA by the sRNA Ec-rnTrpL depends on hfq and rne. Analysis by qRT-PCR of changes in the dnaA mRNA level 3 min after addition of IPTG to strains containing plasmid pSRKTc-Ec-rnTrpL for induced production of the recombinant sRNA lacZ′-Ec-rnTrpL. As a negative control, trpE mRNA was analysed. The dnaA mRNA level after induction was compared to that before induction. Strains with following genetic backgrounds were analysed: (A) the parental strain MG1655 and its mutant MG1655 Δhfq; (B) the parental strain BL322 and its rnc− mutant BL321; (C) the parental strain N3433 and its thermosensitive mutant N3431 (rnets). Cultures were grown in LB medium. The rpoB gene was used as a reference. Shown are means and standard deviations from three independent experiments

Ec-rnTrpL directly interacts with dnaA mRNA in vivo

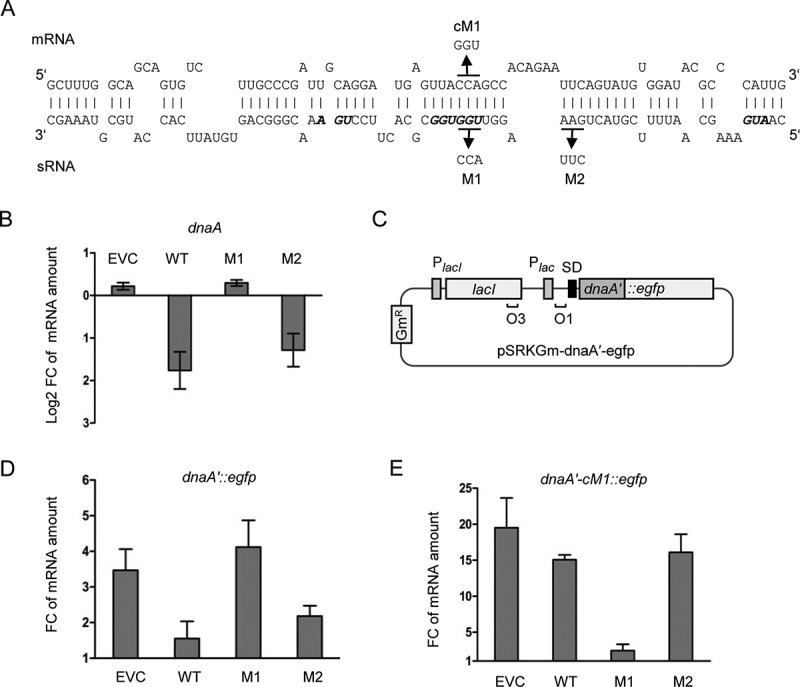

The predicted interaction between Ec-rnTrpL and dnaA mRNA encompasses an extended region, which contains the trpL ORF (Fig. 6A). To validate a direct interaction, two mutations in the lacZ′-Ec-rnTrpL sRNA were conducted, which should weaken the base pairing with the mRNA and thus also the negative effect of sRNA overproduction on the mRNA level. The largest uninterrupted base pairing region (10 bp) comprises the two Trp codons of trpL. Mutation M1 in this region exchanged the first Trp codon, thereby disrupting the predicted 10 bp sRNA – mRNA duplex, while mutation M2 was located upstream in the trpL ORF and was designed to affect a 9 bp duplex region (Fig. 6A). Three minutes after induction of their transcription with IPTG, the levels of the mutated sRNAs were similar to the levels of the induced, wild-type lacZ’-Ec-rnTrpL (Fig. S5), suggesting that the stability of the mutated sRNAs is not strongly changed. Analysis by qRT-PCR of changes in the level of dnaA mRNA revealed that the M1 mutation abolished the decrease in the dnaA mRNA level upon sRNA overproduction. By contrast, the M2 mutation had no significant effect (the decrease in the dnaA mRNA level upon overproduction of the M2-mutated sRNA was similar to the decrease caused by overproduction of the wild-type sRNA; Fig. 6B). This suggests that the region of the Ec-rnTrpL sRNA, which contains the conserved Trp codons, is of critical importance for the negative effect of the sRNA on dnaA mRNA.

Figure 6.

Validation of direct interaction between Ec-rnTrpL and dnaA mRNA in vivo. (A) Scheme of the duplex structure predicted to be formed between dnaA (mRNA) and Ec-rnTrpL (sRNA) (ΔG = −11,74 kcal/mol). The used mutations M1 and M2 in lacZ′-Ec-rnTrpL and the mutation cM1 in dnaA mRNA, which restores the base pairing with the M1-mutation harbouring sRNA, are given. (B) Analysis by qRT-PCR of changes in the dnaA mRNA level 3 min after addition of IPTG to strains containing the empty plasmid pSRKTc (EVC) or its derivatives for induced production of the wild-type, recombinant sRNA lacZ′-Ec-rnTrpL (WT; see Fig. 4B) or mutated sRNAs harbouring one of the indicated mutations (see panel A). (C) Schematic representation of the plasmid used for IPTG-inducible transcription of the dnaA′::egfp reporter fusion. For other details, see Fig. 4B and Fig. 2B. (D) Analysis by qRT-PCR of changes in the dnaA′::egfp mRNA level 3 min after addition of IPTG cultures harbouring pSRKTc (EVC) or its derivatives for induced production of WT or mutants sRNAs (see panel B). (E) Analysis by qRT-PCR of changes in the dnaA′-cM1::egfp mRNA level 3 min after addition of IPTG cultures harbouring pSRKTc (EVC) or its derivatives for induced production of WT or mutants sRNAs (see panel B). The rpoB gene was used as a reference. Cultures grown in LB medium were used. Each graph shows means and standard deviations from three independent experiments

To validate the predicted base pairing between the Ec-rnTrpL sRNA and dnaA mRNA, strains containing two plasmids were used. Each strain contained either the empty pSRKTc plasmid or a pSRKTc-derivative for production of an sRNA (wild-type sRNA lacZ′-Ec-rnTrpL or one of its M1 and M2 variants), and a pSRKGm-based plasmid for production of a translational dnaA′::egfp fusion representing the target mRNA (Fig. 6C). In addition to the wild-type dnaA sequence harbouring the predicted interaction site, a variant with a compensatory M1 mutation (cM1) was constructed (dnaA′-cM1::egfp). This mutation restores the base pairing of the mRNA to the M1-harbouring sRNA (Fig. 6A). Both the sRNA production and egfp reporter expression were induced with IPTG and the level of the reporter mRNA was analysed at the time points 0 min and 3 min post induction using egfp-directed primers. According to Fig. 6D, co-induction of lacZ′-Ec-rnTrpL led to a significant decrease in the reporter mRNA level, when compared to the level in the strain containing the empty plasmid pSRKTc (EVC). This result is in line with the suggested downregulation of dnaA by the sRNA. In contrast, when the M1-harbouring sRNA was co-induced, the dnaA′::egfp mRNA level remained similar to the level in the EVC, suggesting that the M1 mutation abolishes the effect of the sRNA. Furthermore, co-induction of the M2-containing sRNA reduced the dnaA′::egfp mRNA level similar to the wild-type sequence harbouring sRNA. Together, Fig. 6B and 6D show that the M1 region is important for the sRNA effect on dnaA, while the M2 region is not.

Finally, the cM1-containing reporter fusion dnaA′-cM1::egfp was co-induced with each of the sRNA variants (Fig. 6E). Co-induction of the wild-type sequence sRNA or the M2-containing sRNA did not influence the reporter mRNA level (it was not significantly different from the level in the EVC). Importantly, co-induction of the M1-containing sRNA led to significantly lower dnaA′-cM1::egfp mRNA level when compared to the EVC. Thus, the compensatory cM1 mutation, which allows the reporter mRNA to base pair with the M1-containing sRNA, leads to decreased mRNA level only upon co-induction with this mutated sRNA. This result demonstrates the base pairing between Ec-rnTrpL and dnaA mRNA in vivo and indicates that Ec-rnTrpL has the capacity to directly regulate dnaA expression.

Analysis of a ΔtrpL mutant supports a function of Ec-rnTrpL in dnaA regulation

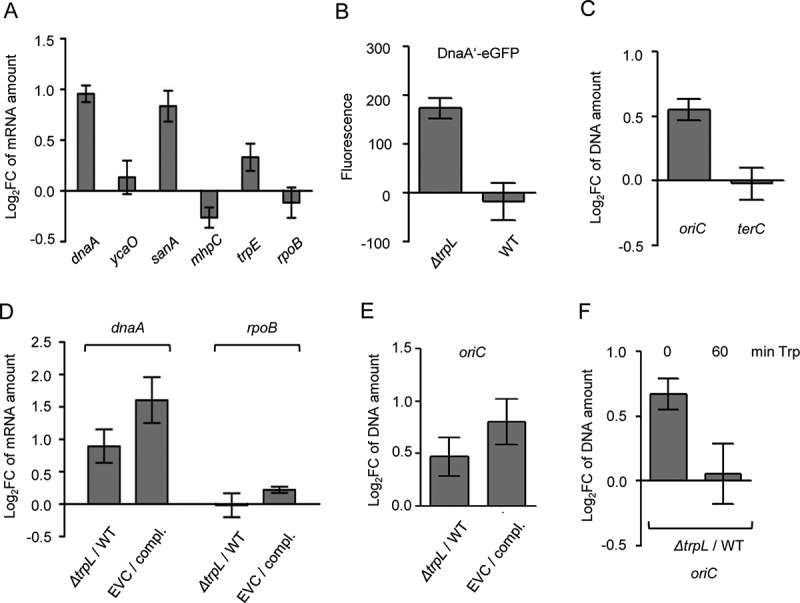

To further validate the importance of Ec-rnTrpL for gene regulation in E. coli, we constructed the deletion mutant E. coli MG1655 ΔtrpL, in which the sequence corresponding to Ec-rnTrpL is deleted from position +3 to +142 (including the transcription terminator; + 1 is the transcription start site). To compare the mRNA levels of dnaA, ycaO, sanA and mhpC in the wild type and the mutant, RNA was isolated from M9 cultures at OD of 0.2 and qRT-PCR was performed. In line with the above results suggesting downregulation of dnaA by Ec-rnTrpL, in the deletion mutant, the dnaA mRNA level was increased when compared to the wild type (Fig. 7A). Furthermore, in the mutant, the level of sanA mRNA was also increased to a similar extent like that of dnaA mRNA, and the level of mhpC mRNA was slightly decreased. The level of ycaO mRNA, which seems not to be affected by the sRNA, was similar in both strains. In addition, trpE and rpoB mRNAs were analysed as non-targets. An increase in the level of trpE mRNA in the mutant was expected due to the lack of transcription attenuation of the trp operon, and a slight increase was detected (Fig. 7A). Moreover, the level of the control mRNA rpoB was similar in both strains. The rpoB mRNA encoding the catalytic subunit of RNA polymerase was used as reference gene in the qRT-PCR analyses shown in Fig. 4, Fig. 5 and Fig. 6. In the Fig. 7A experiment, an external, spike-in control was used as a reference gene. Altogether, these results strongly suggest that dnaA is regulated by Ec-rnTrpL and that sanA and mhpC are also targets of this sRNA.

Figure 7.

Comparison between the ΔtrpL mutant and the parental strain MG1655 confirms the role of Ec-rnTrpL in regulation of dnaA expression and initiation of chromosome replication. (A) The relative amount of the indicated mRNAs were analysed by qRT-PCR and the levels in the ΔtrpL mutant were compared to those in the parental strain MG1655. In vitro transcript was used as reference gene (spike in control). (B) Fluorescence of MG1655 ΔtrpL (pSRKGm-dnaA’-egfp) and MG1655 (pSRKGm-dnaA’-egfp) cultures supplemented with 0.2 mM IPTG. Normalization to EVC cultures was performed. (C) The levels of oriC and terC in the ΔtrpL mutant were compared to those in the parental strain using qPCR. Both strains contained pSRKGm, and the Gm resistance gene was used as reference gene. (D) The relative amounts of dnaA mRNA were analysed by qRT-PCR. The level in the EVC ΔtrpL (pSRKTc) was compared to the level in the complemented strain (compl.) ΔtrpL (pSRKTc-Ec-rnTrpL). Both strains were cultivated in the presence of 0.2 mM IPTG. In parallel, the level in the ΔtrpL mutant was compared to that in the wild type. The rpoB mRNA was analysed as a non-target RNA. A spike-in transcript was used as reference. (E) The oriC level was analysed by qPCR. The level in the EVC was compared to the level in the complemented strain (compl.) (for strain description and growth conditions, see panel D). In parallel, the ΔtrpL mutant was compared to the wild type. As a reference, terC was used. (F) The oriC level was analysed by qPCR. The level in the ΔtrpL mutant was compared to that in the wild type before and 1 h after addition of Trp (20 µg/ml). As a reference, terC was used. Cultures grown in minimal medium were used. Shown are means and standard deviations from three independent experiments

Next, we addressed the question whether the decrease in the dnaA mRNA level by Ec-rnTrpL has influence on protein level. Since we do not have antibodies against DnaA, we used plasmid pSRKGm-dnaA′::egfp (see Fig. 6C) and analysed the level of the fusion protein DnaA′-eGFP in wild type and ΔtrpL background. Cultures were grown in M9 medium supplemented with 0.2 mM IPTG to an OD of 0.7, and fluorescence was measured. Fluorescence was detected in the ΔtrpL mutant but not in the wild type (Fig. 7B). A possible explanation of this result is that in the ΔtrpL mutant the level of the dnaA′::egfp mRNA was sufficient to allow for accumulation of DnaA′-eGFP to a detectable level, while in the wild type Ec-rnTrpL diminished this mRNA. This result suggests that the posttranscriptional regulation of dnaA by the sRNA Ec-rnTrpL could influence the DnaA level.

Next, we asked whether in the deletion mutant, the lack of posttranscriptional regulation of dnaA by Ec-rnTrpL influences the initiation of chromosome replication. It is known that dnaA overexpression leads to increased initiation of chromosome replication, which can be measured as an increase in the copy number of chromosomal origins (oriC) in the cell [39,43]. We used cultures of strains MG1655 (pSRKGm) and MG1655 ΔtrpL (pSRKGm) grown in M9 medium. At an OD of 0.2, DNA was purified and using qPCR, the oriC level in the wild type was compared to that in the mutant, while the Gm-resistance gene present on the plasmid was used as a reference gene. We detected an increased level of oriC in the mutant (Fig. 7C). In contrast, there was not difference between the two strains in the level of the terminus of replication (terC; Fig. 7C), suggesting that the increased oriC level is due to increased initiation of chromosome replication.

To corroborate the above results, complementation experiments were conducted. Cultures of the complemented strain MG1655 ΔtrpL (pSRKTc-Ec-rnTrpL) and of the EVC MG1655 ΔtrpL (pSRKTc) were cultivated in M9 medium supplemented with 0.2 mM IPTG to an OD of 0.3, and then RNA (for qRT-PCR analysis of dnaA mRNA) and DNA (for qPCR analysis of oriC) were isolated. According to Fig. 7D, the level of dnaA mRNA was higher in the EVC than in the complemented strain, showing that even in ΔtrpL background, induction of the sRNA production by IPTG decreased the dnaA mRNA. In line with this, the oriC level was higher in the EVC than in the complemented strain (Fig. 7E). The differences in the dnaA mRNA and oriC levels between the EVC and the complemented strain were somewhat stronger than the differences between the ΔtrpL mutant and the wild type, which were tested in parallel (Fig. 7D and 7E). The results suggest that in the complemented strain, the dnaA downregulation by the ectopically produced sRNA resulted in downregulation of initiation of chromosome replication.

The above results suggest that the sRNA Ec-rnTrpL posttranscriptionally downregulates dnaA to indirectly regulate initiation of chromosome replication. Since the cellular Ec-rnTrpL production depends on the Trp availability, the above results imply that Trp could be a signal for modulation of initiation of chromosome replication. To address this, 20 µg/ml Trp was added to MG1655 and MG1655 ΔtrpL cultures grown in M9 medium to an OD of 0.2. Before Trp addition, the oriC level in the ΔtrpL mutant was higher than in the wild type (Fig. 7F), probably due to Ec-rnTrpL production resulting in dnaA downregulation in the wild type. One hour after Trp addition, the oriC levels in the ΔtrpL mutant and in the wild type were similar (Fig. 7F). This could be explained by transcriptional repression of Ec-rnTrpL production in the wild type, which would result in dnaA upregulation followed by increased initiation of chromosome replication. This result is in line with the role of Trp as a signal of nutrient availability for the regulation of replication initiation.

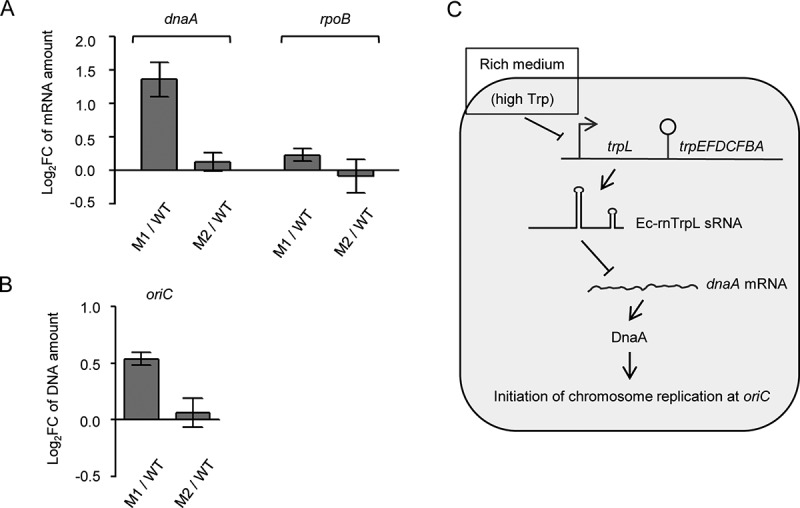

Chromosomal Ec-rnTrpL mutations confirm the sRNA role in regulation of dnaA and replication initiation

To further corroborate the above results, the M1 and M2 mutations (see Fig. 6A above) were introduced into the E. coli chromosome. Resulting strains MG1655 trpL-M1 and MG1655 trpL-M2 and the wild-type strain were grown in M9 medium to an OD of 0.3, and the levels of dna mRNA and oriC were analysed by qRT-PCR and qPCR, respectively. In the trpL-M1 mutant, the dnaA mRNA and oriC levels were higher than the levels in wild type (Fig. 8A and 8B). This is in line with our finding that the M1 mutation abolishes the interaction of the sRNA with dnaA mRNA (see Fig. 6). Furthermore, in the trpL-M2 mutant, the dnaA mRNA and oriC levels were similar to those in the wild type (Fig. 8A and 8B), in line with our observation that the M2-containing sRNA still downregulates dnaA (see Fig. 6). In summary, these results support the role of Ec-rnTrpL in regulation of dnaA and initiation of chromosome replication.

Figure 8.

Chromosomal mutations in Ec-rnTrpL confirm function in regulation of dnaA and replication initiation. (A) The relative amounts of dnaA mRNA were analysed by qRT-PCR. The level in strains carrying the M1 or M2 mutations (see Fig. 6A above) was compared to the level in the wild type. The rpoB mRNA was analysed as a non-target RNA. A spike-in transcript was used as reference. (B) The oriC level was analysed by qPCR. The level in strains carrying the M1 or M2 mutations was compared to the level in the wild type. As a reference, terC was used. Cultures grown in minimal medium to the OD of 0.3 were used. Shown are means and standard deviations from three independent experiments. (C) Model for posttranscriptional regulation of dnaA expression and initiation of chromosome replication by Ec-rnTrpL. In rich medium, the high Trp supply leads to repression of Ec-rnTrpL transcription. Since Ec-rnTrpL binds to dnaA mRNA and downregulates its level, in rich medium the dnaA expression is activated at the level of RNA, leading to more frequent initiation of chromosome replication

Discussion

In this work, we provide evidence for functions in trans of the small RNA Ec-rnTrpL, which arises by transcription attenuation of the E. coli trp operon. Our bioinformatic prediction shows that this sRNA has the capacity to base pair with multiple mRNAs. The results from the validation experiments strongly suggest that dnaA mRNA is a direct target of this sRNA: the dnaA mRNA level was decreased upon sRNA overproduction, increased in the ΔtrpL deletion mutant, and a base pairing in vivo was demonstrated, which negatively affected the expression of the reporter fusion construct. Our data revealed that the trp operon is suitable source of an sRNA acting at higher ODs (Fig. 1A and Fig. 1C). This sRNA expression pattern fits well with a function in downregulation of the gene encoding the master regulator of chromosome replication initiation. However, although the promoter and promoter/attenuator reporter constructs suggested that Ec-rnTrpL is produced at ODs between 1.0 and 2.0, the sRNA was under the limit of detection by Northern blot at these ODs. A possible explanation of this result would be a fast degradation of the sRNA, possibly together with its targets [44]. In the above-mentioned CLASH study of the Hfq interactome, trpL mRNA (which corresponds to Ec-rnTrpL) was detected together with a hdeD mRNA when cells grown in LB to ODs of 1.2–1.8 were used [23]. Very few reads of trpL mRNA (Ec-rnTrpL) were detected in that study [23], probably explaining why targets such as dnaA mRNA were missed. Our data suggest that Ec-rnTrpL is a typical enterobacterial sRNA [9], which needs Hfq and RNase E to regulate its target dnaA mRNA (Fig. 5).

Furthermore, our observation that the levels of sanA and mhpC mRNA were inversely affected in the overproducing and deletion mutant strains suggests that Ec-rnTrpL binds to the predicted interaction regions in these mRNAs and regulates the expression of the corresponding genes and operons in a negative and a positive way, respectively. The gene sanA has a role in the RpoS-dependent SDS resistance in carbon-limited stationary phase [45]. The possible regulation of sanA and hdeD (the latter encodes an acid-resistance membrane protein needed at high cell densities and is regulated by two other sRNAs [46]) by Ec-rnTrpL suggests that this sRNA could play a role in the modulation of the cell envelope. Since SanA is needed at high cell densities, but Ec-rnTrpL decreases the sanA mRNA level, in this case, Ec-rnTrpL could act in the fine-tuning of sanA expression [47–49]. The mhp operon is responsible for degradation of aromatic compounds [50]. The possible positive regulation of the mhp operon by Ec-rnTrpL could contribute to the usage of alternative carbon sources. In future, it will be interesting to analyse these and additional predicted targets of Ec-rnTrpL.

We note that the predicted base pairing of the sRNA with each of the four top predicted targets overlaps with the trpL ORF. The functionally important Trp codons UGGUGG of the trpL ORF are predicted to be involved in the base pairing of Ec-rnTrpL with dnaA and sanA mRNAs (Fig. S3), which were affected to a similar extent in the deletion mutant (Fig. 7A). Moreover, we demonstrated the crucial importance of the first Trp codon for the in vivo interaction between Ec-rnTrpL and dnaA mRNA, thus showing that this codon belongs to the sRNA seed region needed for this interaction (Fig. 6). This is in line with previous observations showing that often highly conserved sRNA parts harbour the seed region [51,52]. The S. meliloti Trp codons of trpL were also predicted to base pair with trpD mRNA [16]. However, in that study, it was not tested whether these codons belong to the sRNA seed region.

Ec-rnTrpL is a homolog of the attenuator sRNA rnTrpL (synonym RcsR1) in Rhizobiaceae and Bradyrhizobiaceae [16,53]. In S. meliloti, rnTrpL is constitutively transcribed during growth, and its termination is regulated by attenuation [54]. The primary function of the rhizobial sRNA seems to be the coordination of the expression of separate trp operons. In E. coli having the trp genes in a single operon, this function is not needed and consequently, overproduction of Ec-rnTrpL has no effect on the expression of the trp genes [16]. Despite these differences, Ec-rnTrpL obviously adopted functions in trans during evolution and was integrated into the cellular regulatory networks of E. coli. This was probably favoured by its Rho-independent terminator, which probably serves as an Hfq-binding site, thus making the attenuation-liberated Ec-rnTrpL sRNA a suitable candidate for a riboregulator [47].

It is known that overproduction of DnaA stimulates initiation of chromosome replication, but leads to decreased replication speed, and therefore the total DNA amount in the cell is not increased [55]. Additionally, it was reported that up to four-fold overproduction of DnaA increases the origins per mass ratio up to 1.8 -fold [56]. Thus, the here observed increase in the oriC level of approximately 1.5-fold in the ΔtrpL mutant supports the view that the posttranscriptional regulation of dnaA by sRNA Ec-rnTrpL affects the cellular level of the DnaA protein and its role in initiation of chromosome replication.

As explained in the introduction, the production of Ec-rnTrpL is regulated at the transcriptional and posttranscriptional level by repression and attenuation, respectively [19]. Since the transcription initiation of Ec-rnTrpL depends on the cellular Trp level, while its termination and thus the liberation as sRNA on the amount of charged tRNATrp [13], Ec-rnTrpL may link important cellular processes in response to Trp availability. Such a link is plausible, because Trp is the most costly to synthesize amino acid [19]. Thus, the cellular level of Trp may serve as a measure of ‘prosperity’ and be used to regulate (via Ec-rnTrpL) dnaA expression under different nutritional conditions. Considering this hypothesis and our data, we suggest the following model for regulation of chromosome replication initiation (Fig. 8C): In rich medium with high Trp supply, transcription of the sRNA is mostly repressed by the Trp-binding repressor. This leads to accumulation of dnaA mRNA, higher DnaA production and more frequent initiation of chromosome replication, which is needed for faster growth under these conditions. In minimal medium, however, Ec-rnTrpL transcription is derepressed. Since relieve of transcription attenuation (co-transcription of trpLEGDCFBA) takes place only under severe Trp insufficiency conditions [20], in prototrophic E. coli in minimal medium, Ec-rnTrpL transcription is regularly terminated and the sRNA accumulates. The increased Ec-rnTrpL production in minimal medium leads to downregulation of dnaA expression, which helps to adjust the levels of the DnaA protein to the slower growth rate (Fig. 8C).

Due to the transcription attenuation [13], in minimal medium oscillation in the Ec-rnTrpL production is expected. On the one hand, since the Trp biosynthesis ensures Trp supply, transcription of the structural genes is mostly attenuated and the Ec-rnTrpL sRNA is liberated. On the other hand, during cellular growth, when the intracellular Trp becomes scarce, attenuation is relieved and Ec-rnTrpL production decreased (trpL is cotranscribed with the structural genes). This is counterintuitive in the light of the here proposed dnaA regulation, since it implies an increase in the level of dnaA mRNA and thus accumulation of DnaA under conditions of Trp insufficiency. Whether such an oscillation influences dnaA expression in minimal medium (for example, via a negative feedback-loop [47–49];), remains to be analysed. However, since the attenuator regulates the trp operon expression 5- to 8-fold, while the transcription repression is capable to regulate it over a 100-fold range [20], the production of Ec-rnTrpL in response to the cellular Trp concentration is regulated mainly at the transcriptional level. Thus, the sRNA Ec-rnTrpL is well suited to regulate dnaA expression according to the nutrient availability. The predicted conservation of the rnTrpL/dnaA interaction site in various Enterobacteriaceae (Fig. 3A) furthermore indicates that this regulatory circuit may exist beyond E. coli.

Interestingly, interconnection between dnaA and the trp attenuator in E. coli was observed previously and it was suggested that the DnaA protein increases the transcription attenuation [57]. Our data reinforce the genetic interaction between dnaA and the trp attenuator, showing that the released attenuator sRNA downregulates dnaA posttranscriptionally. Together, this suggests a regulatory loop ensuring efficient dnaA downregulation by Ec-rnTrpL at high intracellular DnaA concentration.

Recently, RNA-based regulation of dnaA was described in Alphaproteobacteria. In S. meliloti, dnaA mRNA is not a predicted target of rnTrpL [53], but is destabilized by the sRNA EcpR1, which is induced in a stress- and growth-stage dependent manner [58]. Indeed, the transcription of S. meliloti rnTrpL in the exponential growth phase under conditions of Trp availability makes this sRNA unsuitable for regulation of DnaA homoeostasis at different growth rates. The differences in transcription regulation of rnTrpL in S. meliloti and E. coli probably led to diversification of the functions of these homologous sRNAs. In Caulobacter crescentus, regulation of dnaA mRNA translation initiation in response to nutrient availability was shown [59]. Furthermore, sRNAs were predicted to regulate dnaA in C. crescentus [60], and trans-translation was described to affect dnaA expression in C. crescentus and E. coli [61]. Thus, the here described regulation of dnaA by the sRNA Ec-rnTrpL may be only a part of the posttranscriptional mechanisms regulating dnaA expression in Gammaproteobacteria.

If defined as an sRNA liberated by transcription attenuation upstream of structural Trp biosynthesis genes, rnTrpL homologs are found in a variety of Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria [19,62]. This suggests that rnTrpL could belong to the most conserved base-pairing sRNAs in bacteria. However, due to the different attenuation mechanisms of trp operons, which are typically found in Gram-positive [63,64] and Gram-negative [13,19] bacteria, their attenuator sRNA candidates differ markedly. Those of Gram-negative bacteria harbour a trpL ORF and arise due to ribosome-dependent attenuation. Therefore, they are potential dual-function sRNAs, which in addition to being candidates for base-pairing riboregulators, can also act as small mRNAs [65,66]. Indeed, the trpL-encoded leader peptide peTrpL was shown to have an independent role in multiresistance of S. meliloti and related Alphaproteobacteria [31]. Now, after providing evidence for an own function of Ec-rnTrpL as a riboregulator in this work, it is tempting to speculate that the corresponding Ec-peTrpL peptide is also functional, and that the fascinating multifunctionality of the trp attenuator is not restricted to the Alphaproteobacteria.

In summary, our work expands the limited knowledge on trans-acting sRNAs derived from 5′-UTRs in bacteria. The data suggest that the ancient sRNA rnTrpL, the cellular level of which is related to Trp availability, is a base-pairing riboregulator in enterobacteria, where it is involved in the regulation of dnaA and thus of initiation of chromosome replication. Based on this, we propose that Trp is an intracellular signal linking metabolism to DnaA homoeostasis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Susanne Barth-Weber for excellent technical assistance, Robina Scheuer for the spike-in transcript, and Robina Scheuer and Saina Azarderakhsh for help with the mRNA half-life determination.

Funding Statement

This work was supported by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft [grant numbers Ev42/6-1 to E.E.H. and GE 3159/1‐1 to J.G.] and China Scholarship Council [grant number 2017080800082 to S.L].

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- [1].Løbner-Olesen A, Skarstad K, Hansen FG, et al. The DnaA protein determines the initiation mass of Escherichia coli K-12. Cell. 1989;57(5):881–889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Skarstad K, Katayama T.. Regulating DNA replication in bacteria. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2013;5:a012922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Hansen FG, Atlung T. The DnaA Tale. Front Microbiol. 2018;9:319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hansen FG, Atlung T, Braun RE, et al. Initiator (DnaA) protein concentration as a function of growth rate in Escherichia coli and Salmonella typhimurium. J Bacteriol. 1991;173:5194–5199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Boye E, Løbner-Olesen A, Skarstad K. Limiting DNA replication to once and only once. EMBO Rep. 2000;1:479–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Leonard AC, Rao P, Kadam RP, et al. Changing Perspectives on the Role of DnaA-ATP in Orisome Function and Timing Regulation. Front Microbiol. 2019;10:2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Chiaramello AE, Zyskind JW. Coupling of DNA replication to growth rate in Escherichia coli: a possible role for guanosine tetraphosphate. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:2013–2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Bernstein JA, Khodursky AB, Lin PH, et al. Global analysis of mRNA decay and abundance in Escherichia coli at single-gene resolution using two-color fluorescent DNA microarrays. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:9697–9702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Storz G, Vogel J, Wassarman KM. Regulation by small RNAs in bacteria: expanding frontiers. Mol Cell. 2011;43:880–891. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Wagner EGH, Romby P. Small RNAs in bacteria and archaea: who they are, what they do, and how they do it. Adv Genet. 2015;90:133–208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Miyakoshi M, Chao Y, Vogel J. Regulatory small RNAs from the 3ʹ regions of bacterial mRNAs. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2015;24:132–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].De Lay NR, Garsin DA. The unmasking of ‘junk’ RNA reveals novel sRNAs: from processed RNA fragments to marooned riboswitches. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2016;30:16–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Yanofsky C. Attenuation in the control of expression of bacterial operons. Nature. 1981;289:751–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Gollnick P, Babitzke P. Transcription attenuation. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1577:240–250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Turnbough CL Jr. Regulation of Bacterial Gene Expression by Transcription Attenuation. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2019;83:e00019-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Melior H, Li S, Madhugiri R, et al. Transcription attenuation-derived small RNA rnTrpL regulates tryptophan biosynthesis gene expression in trans. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:6396–6410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zubay G, Morse DE, Schrenk WJ, et al. Detection and isolation of the repressor protein for the tryptophan operon of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1972;69:1100–1103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Shimizu Y, Shimizu N, Hayashi M. In vitro repression of transcription of the tryptophan operon by trp repressor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1973;70:1990–1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Merino E, Jensen RA, Yanofsky C. Evolution of bacterial trp operons and their regulation. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2008;11:78–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Yanofsky C, Horn V. Role of regulatory features of the trp operon of Escherichia coli in mediating a response to a nutritional shift. J Bacteriol. 1994;176:6245–6254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Holmqvist E, Li L, Bischler T, et al. Global Maps of ProQ Binding In Vivo Reveal Target Recognition via RNA Structure and Stability Control at mRNA 3ʹ Ends. Mol Cell. 2018;70(5):971–982.e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Melamed S, Adams PP, Zhang A, et al. RNA-RNA Interactomes of ProQ and Hfq Reveal Overlapping and Competing Roles. Mol Cell. 2020;77(2):411–425.e7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Iosub IA, van Nues RW, McKellar SW, et al. Hfq CLASH uncovers sRNA-target interaction networks linked to nutrient availability adaptation. Elife. 2020;9:e54655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Lalaouna D, Massé E. Identification of sRNA interacting with a transcript of interest using MS2-affinity purification coupled with RNA sequencing (MAPS) technology. Genom Data. 2015;5:136–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Melamed S, Peer A, Faigenbaum-Romm R, et al. Global Mapping of Small RNA-Target Interactions in Bacteria. Mol Cell. 2016;63:884–897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Waters SA, McAteer SP, Kudla G, et al. Small RNA interactome of pathogenic E. coli revealed through crosslinking of RNase E. Embo J. 2017;36:374–387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Wright PR, Richter AS, Papenfort K, et al. Comparative genomics boosts target prediction for bacterial small RNAs. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E3487–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Raden M, Ali SM, Alkhnbashi OS, et al. Freiburg RNA tools: a central online resource for RNA-focused research and teaching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:W25–W29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Sambrook J, Fritsch EF, Maniatis T. Molecular cloning: A laboratory manual. 2. Cold Spring Harbor, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- [30].Khan SR, Gaines J, Roop RM 2, et al. Broad-host-range expression vectors with tightly regulated promoters and their use to examine the influence of TraR and TraM expression on Ti plasmid quorum sensing. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2008;74:5053–5062. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Melior H, Maaß S, Li S, et al. The Leader Peptide peTrpL Forms Antibiotic-Containing Ribonucleoprotein Complexes for Posttranscriptional Regulation of Multiresistance Genes. mBio. 2020;11:e01027–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Berghoff BA, Hoekzema M, Aulbach L, et al. Two regulatory RNA elements affect TisB-dependent depolarization and persister formation. Mol Microbiol. 2017;103:1020–1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Datsenko KA, Wanner BL. One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:6640–6645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Datta S, Costantino N, Court DL. A set of recombineering plasmids for gram-negative bacteria. Gene. 2006;379:109–115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Basineni SR, Madhugiri R, Kolmsee T, et al. The influence of Hfq and ribonucleases on the stability of the small non-coding RNA OxyS and its target rpoS in E. coli is growth phase dependent. RNA Biol. 2009;6:584–594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Evguenieva-Hackenberg E, Walter P, Hochleitner E, et al. An exosome-like complex in Sulfolobus solfataricus. EMBO Rep. 2003;4:889–893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Pfaffl MW. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Res. 2001;29:e45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Haugan MS, Charbon G, Frimodt-Møller N, et al. Chromosome replication as a measure of bacterial growth rate during Escherichia coli infection in the mouse peritonitis model. Sci Rep. 2018;8:14961. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Riber L, Olsson JA, Jensen RB, et al. Hda-mediated inactivation of the DnaA protein and dnaA gene autoregulation act in concert to ensure homeostatic maintenance of the Escherichia coli chromosome. Genes Dev. 2006;20:2121–2134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Lott SC, Schäfer RA, Mann M, et al. GLASSgo - Automated and Reliable Detection of sRNA Homologs From a Single Input Sequence. Front Genet. 2018;9:124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Mann M, Wright PR, Backofen R. IntaRNA 2.0: enhanced and customizable prediction of RNA-RNA interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45:W435–W439. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Melior H, Maaß S, Stötzel M, et al. The bacterial leader peptide peTrpL has a conserved function in antibiotic-dependent posttranscriptional regulation of ribosomal genes. biorXiv. 2019. 26 September 2019, pre-print: not peer-reviewed. DOI: 10.1101/606483. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Grimwade JE, Rozgaja TA, Gupta R, et al. Origin recognition is the predominant role for DnaA-ATP in initiation of chromosome replication. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:6140–6151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Massé E, Escorcia FE, Gottesman S. Coupled degradation of a small regulatory RNA and its mRNA targets in Escherichia coli. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2374–2383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Mitchell AM, Wang W, Silhavy TJ. Novel RpoS-Dependent Mechanisms Strengthen the Envelope Permeability Barrier during Stationary Phase. J Bacteriol. 2016;199,:e00708–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Lalaouna D, Prévost K, Laliberté G, et al. Contrasting silencing mechanisms of the same target mRNA by two regulatory RNAs in Escherichia coli. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46:2600–2612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Hör J, Matera G, Vogel J, et al. Trans-Acting Small RNAs and Their Effects on Gene Expression in Escherichia coli and Salmonella enterica. EcoSal Plus. 2020;9. DOI: 10.1128/ecosalplus.ESP-0030-2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Mank NN, Berghoff BA, Klug G. A mixed incoherent feed-forward loop contributes to the regulation of bacterial photosynthesis genes. RNA Biol. 2013;10:347–352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Nitzan M, Rehani R, Margalit H. Integration of Bacterial Small RNAs in Regulatory Networks. Annu Rev Biophys. 2017;46:131–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Manso I, Torres B, Andreu JM, et al. 3-Hydroxyphenylpropionate and phenylpropionate are synergistic activators of the MhpR transcriptional regulator from Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:21218–21228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Sharma CM, Darfeuille F, Plantinga TH, et al. A small RNA regulates multiple ABC transporter mRNAs by targeting C/A-rich elements inside and upstream of ribosome-binding sites. Genes Dev. 2007;21:2804–2817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Peer A, Margalit H. Accessibility and evolutionary conservation mark bacterial small-rna target-binding regions. J Bacteriol. 2011;193:1690–1701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Baumgardt K, Šmídová K, Rahn H, et al. The stress-related, rhizobial small RNA RcsR1 destabilizes the autoinducer synthase encoding mRNA sinI in Sinorhizobium meliloti. RNA Biol. 2016;13:486–499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Bae YM, Crawford IP. The Rhizobium meliloti trpE(G) gene is regulated by attenuation, and its product, anthranilate synthase, is regulated by feedback inhibition. J Bacteriol. 1990;172:3318–3327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Atlung T, Løbner-Olesen A, Hansen FG. Overproduction of DnaA protein stimulates initiation of chromosome and minichromosome replication in Escherichia coli. Mol Gen Genet. 1987;206:51–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Atlung T, Hansen FG. Three distinct chromosome replication states are induced by increasing concentrations of DnaA protein in Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:6537–6545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Atlung T, Hansen FG. Effect of dnaA and rpoB mutations on attenuation in the trp operon of Escherichia coli. J Bacteriol. 1983;156:985–992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Robledo M, Frage B, Wright PR, et al. A stress-induced small RNA modulates alpha-rhizobial cell cycle progression. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Leslie DJ, Heinen C, Schramm FD, et al. Nutritional Control of DNA Replication Initiation through the Proteolysis and Regulated Translation of DnaA. PLoS Genet. 2015;11:e1005342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Beroual W, Brilli M, Biondi EG. Non-coding RNAs Potentially Controlling Cell Cycle in the Model Caulobacter crescentus: A Bioinformatic Approach. Front Genet. 2018;9:164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Wurihan W, Wunier W, Li H, et al. Trans-translation ensures timely initiation of DNA replication and DnaA synthesis in Escherichia coli. Genet Mol Res. 2016;15:3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Vitreschak AG, Lyubetskaya EV, Shirshin MA, et al. Attenuation regulation of amino acid biosynthetic operons in proteobacteria: comparative genomics analysis. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 2004;234:357–370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Gollnick P, Babitzke P, Antson A, et al. Complexity in regulation of tryptophan biosynthesis in Bacillus subtilis. Annu Rev Genet. 2005;39:47–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Babitzke P, Lai YJ, Renda AJ, et al. Posttranscription Initiation Control of Gene Expression Mediated by Bacterial RNA-Binding Proteins. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2019;73:43–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Vanderpool CK, Balasubramanian D, Lloyd CR. Dual-function RNA regulators in bacteria. Biochimie. 2011;93:1943–1949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Gimpel M, Brantl S. Dual-function small regulatory RNAs in bacteria. Mol Microbiol. 2017;103:387–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.