Abstract

Objective

To document the prevalence of anxiety disorders in the USA during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Design

A cross-sectional analysis.

Setting

A nationally representative sample in the USA between 31 March and 13 April 2020.

Participants

1450 English-speaking adult participants in the AmeriSpeak Panel. AmeriSpeak is a probability-based panel designed to be representative of households in the USA.

Main outcome measures

Prevalence of probable generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) using the GAD-7 and post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) using the four-item PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) checklist. Both outcomes were stratified by demographics and COVID-19-related stressors.

Results

The majority of participants were female (51.8%), non-Hispanic white (62.9%) and reported a household saving of $5000 or more. Those between 18 and 29 years old were the largest age group (38.1%) compared with 40–59 years (32.0%) and 60 years or more (29.9%). The prevalence of probable GAD was 10.9% (95% CI 9.1% to 13.2%) and the prevalence of PTSS was 21.7% (95% CI 19.1% to 24.6%). Among participants reporting five or more COVID-19-related stressors, the prevalence of probable GAD was 20.5% (95% CI 16.1% to 25.8%) and the prevalence of PTSS was 35.7% (95% CI 30.2% to 41.6%). Experiencing five or more COVID-19-related stressors was a predictor of both probable GAD (OR=4.5, 95% CI 2.3 to 8.8) and PTSS (OR=3.3, 95% CI 2.1 to 5.1).

Conclusions

The prevalence of probable anxiety disorders in the USA, as the COVID-19 pandemic and policies implemented to tackle it unfolded, is higher than estimates reported prior to the pandemic and estimates reported following other mass traumatic events. Exposure to COVID-19-related stressors is associated with higher prevalence of both probable GAD and PTSS, highlighting the role these stressors play in increasing the risk of developing anxiety disorders in the USA. Mitigation and recovery policies should take into account the mental health toll the pandemic had on the USA population.

Keywords: mental health, COVID-19, anxiety disorders

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This analysis uses a nationally representative sample in the USA.

This study was conducted within a short duration following the implementation of statewide policies to tackle the COVID-19 pandemic and includes questions about a wide range of social and economic COVID-19-related stressors.

To assess the risk of developing anxiety disorders, the study uses screening rather than diagnostic tools.

However, these screening tools have been validated extensively for assessment of anxiety disorders in the general populations.

The use of a preselected panel of participants can lead to selection bias.

Introduction

The effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on the American public has been profound. More than 600 000 people have died from COVID-19 in the USA, and a number of unprecedented physical distancing policies were implemented during the early phases of the pandemic to limit the spread of the virus. The pandemic changed daily life for most people in the USA significantly and continues to have large-scale social and economic consequences. The physical toll of COVID-19, coupled with the ubiquity and severity of the policies, distinguishes the pandemic as a mass traumatic event, one that is associated with extensive loss of lives and financial strains that can lead to severe and lasting psychological consequences, anxiety disorders in particular.1–4

Uncertainty, fear, economic and social costs, and disruptions to daily life all contribute to a high prevalence of anxiety disorders following mass traumatic events.5 6 For example, a study assessing the mental health consequences of the Ebola epidemic in Sierra Leone found that, a year following the epidemic, 6% of participants reached the threshold for a combined anxiety-depression measure and 27% reached the threshold for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).7 Another study estimated that, following Hurricane Katrina, the 30-day prevalence of PTSD was 30.3% among residents of the New Orleans metropolitan area, which was severely affected by the hurricane.8

This previous work suggests that the COVID-19 pandemic will have a substantial impact on the prevalence of anxiety disorders in the USA. Early evidence has found that COVID-19 pandemic is associated with adverse mental health consequences9,9–22 However, to our knowledge, the association between COVID-19 and related stressors—both due to the pandemic and policies implemented to halt its spread—and the risk of developing anxiety disorders in the USA is yet to be fully documented.

We assessed the prevalence of anxiety disorders, specifically probable generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) and post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS), as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded in the USA. We also assessed the association between COVID-19-related stressors and the risk of developing anxiety disorders following the implementation of widespread physical distancing policies in the USA.

Methods

Data collection and sample

This analysis was based on data from our COVID-19 and Life stressors Impact on Mental Health and Well-being Study (CLIMB). We collected nationally representative data using a random sample of adult participants in the AmeriSpeak Panel between 31 March and 13 April 2020. AmeriSpeak is a probability-based panel designed to be representative of households in the USA. The panel is funded and operated by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) at the University of Chicago and their sampling frame covers approximately 97% of households in the country. The survey was offered to English-speaking participants who had completed an AmeriSpeak survey in the last 6 months.

In total, 1470 participants completed the survey, 1385 online and 85 via the phone, representing 64.3% of invited panellists. From those 1470 participants, 20 had missing data on either GAD or PTSS questions, which were removed; the final analysis included 1450 participants.

Exposure variables

Our structured survey included questions on demographic characteristics (sex, age, race and ethnicity, education, marital status, household income, household savings and household size) and whether the respondent had or knew anyone who had COVID-19. The primary exposure of interest was reporting COVID-19-related stressors. The stressor list was based on prior analyses following traumatic events.17 23 The list included financial stressors (eg, losing a job, having difficulty paying rent, having financial problems, a member of your family losing a job and having hours reduced at your job) and social and emotional stressors (eg, feeling along, having relationship problems, family or relationship problems, not being able to get food due to shortages, not being able to get supplies due to shortages, challenges finding childcare, not going to school, travel restrictions, seeing family less in person and death of someone close to you due to COVID-19). We excluded stressors that were applicable to only a subset of the population, ultimately including 14 stressors in our analysis. We then created a cumulative stressor score and divided the score into three stressor categories: low (0–2 stressors), medium (3–4 stressors) and high (5–14 stressors). The score reflects the symptom distribution in the sample, with approximately one-third of the sample in each category.

Outcome variables

For psychological assessment, we used two validated anxiety disorders questionnaires. We used the GAD-7 to assess GAD. The cut-off for probable GAD in our analysis was a score of 15 or more. This cut-off was based on the recommended cut-offs for GAD-7 to screen for GAD.24 We also conducted a sensitivity analysis with a cut-off score of 10 or more. We used the four-item PTSD checklist (PCL) to screen for PTSS. The cut-off for PTSS was a score of 3 or more.25

Statistical analysis

We used STATA V.16.1 to conduct the analysis for this study. All analyses were weighted using complex survey weights to adjust for sample selection and post-stratification. We calculated the overall prevalence of probable GAD and PTSS and the prevalence of each outcome stratified by number of stressors. We then conducted a bivariable analysis comparing probable GAD and PTSS prevalence across demographic characteristics, stressor score and each type of stressor using a two-tailed χ2 test. We used complete case analysis for the multivariable logistic regression models to estimate the ORs of the association between COVID-19-related stressor score and probable GAD and PTSS when controlling for sex, age, race, education, marital status, household income, household savings and household size. In a sensitivity analysis, we included concern about COVID-19 in the multivariable logistic regression model. We also constructed other multivariable logistic regression models with the number of stressors as a continuous variable and models that divide the stressors into two continuous variables (financial stressors and social stressors) as sensitivity analyses. We followed the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) reporting guideline for cross-sectional studies when designing and reporting on this analysis.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in developing the research question, design or implementation of this analysis. This is primarily because we did not have funding to support such involvement and our analysis was on a national level using validated assessment tools.

Results

Of the 1450 participants, 10.9% (95% CI 9.1% to 13.2%) reached the threshold for probable GAD, using a score of 15 as a cut-off. When using a score of 10 as a cut-off point, 25% (95% CI 22.2% to 28.0%) reached the threshold for probable GAD. In terms of PTSS, 21.7% (95% CI 19.1% to 24.6%) reached the threshold.

Table 1 shows the association between demographic characteristics and the two outcomes. In particular, female sex was associated with a higher prevalence of both probable GAD and PTSS in the bivariable analysis. The prevalence of probable GAD was 14.1% (95% CI 11.2% to 17.6%) among females compared with 7.6% (95% CI 5.4% to 10.4%) among males. The prevalence of probable PTSS was 26.1% (95% CI 22.3% to 30.2%) among females compared with 17% (95% CI 13.5% to 21.2%) among males. Other demographic variables associated with both outcomes in the bivariable analysis were age and household savings. In the multivariable analysis, reporting household savings of less than $5000 was a predictor of GAD (OR=1.9, 95% CI 1.2 to 3.1).

Table 1.

Generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) and post-traumatic distress symptoms (PTSS) in adults 18 years and older in the USA by demographic characteristics and COVID-19-related stressors

| Generalised anxiety disorder | Post-traumatic stress symptoms | ||||||||

| N (%) |

% (95% CI) |

P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | % (95% CI) |

P value | OR (95% CI) | P value | |

| Overall | 1450 | 10.9 (9.1 to 13.2) |

21.7 (19.1 to 24.6) |

||||||

| Sex | |||||||||

| Male | 725 (48.2) | 7.6 (5.4 to 10.4) |

0.0018 | Ref | 17 (13.5 to 21.2) |

0.0017 | Ref | ||

| Female | 725 (51.8) | 14.1 (11.2 to 17.6) |

1.6 (1.0 to 2.5) |

0.055 | 26.1 (22.3 to 30.2) |

1.5 (1.1 to 2.1) |

0.024 | ||

| Age (years) | |||||||||

| 18–39 | 623 (38.1) | 16.6 (13.0 to 21.2) |

<0.0001 | Ref | 26.1 (21.5 to 31.3) |

<0.0001 | Ref | ||

| 40–59 | 461 (32.0) | 9.2 (6.6 to 12.6) |

0.6 (0.3 to 1.0) |

0.035 | 25.5 (20.9 to 30.7) |

1.0 (0.7 to 1.5) |

0.850 | ||

| ≥60 | 366 (29.9) | 5.6 (3.4 to 9.1) |

0.50 (0.2 to 1.1) |

0.078 | 12.0 (8.5 to 16.6) |

0.6 (0.3 to 1.0) |

0.050 | ||

| Race/ethnicity | |||||||||

| Non-Hispanic white | 939 (62.9) | 10.8 (8.6 to 13.5) |

0.3468 | Ref | 22.0 (18.9 to 25.4) |

0.1914 | Ref | ||

| Non-Hispanic black | 143 (11.9) | 11.9 (6.8 to 20.1) |

0.8 (0.4 to 1.8) |

0.603 | 18.9 (12.5 to 27.6) |

0.7 (0.4 to 1.2) |

0.157 | ||

| Hispanic | 258 (16.7) | 11.3 (6.8 to 18.3) |

0.8 (0.4 to 1.3) |

0.307 | 27.0 (19.5 to 36.2) |

1.1 (0.7 to 1.8) |

0.749 | ||

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 36 (3.1) | 0.8 (0.1 to 5.5) |

0.1 (0.0 to 0.7) |

0.023 | 8.7 (2.4 to 26.8) |

0.3 (0.1 to 1.4) |

0.142 | ||

| Other | 74 (5.4) | 15.1 (7.4 to 28.6) |

1.0 (0.4 to 2.7) |

0.919 | 15.8 (7.7 to 29.5) |

0.6 (0.3 to 1.2) |

0.131 | ||

| Education | |||||||||

| No high school diploma | 67 (9.9) | 13.4 (6.2 to 26.5) |

0.0230 | 1.2 (0.5 to 3.2) |

0.643 | 19.7 (10.9 to 32.8) |

0.3825 | 0.7 (0.4 to 1.5) |

0.393 |

| High school grad or GED | 276 (27.9) | 10.4 (6.8 to 15.4) |

1.2 (0.6 to 2.4) |

0.615 | 25.3 (19.5 to 32.2) |

1.2 (0.7 to 1.9) |

0.560 | ||

| Some college | 638 (27.6) | 15.8 (12.4 to 20.0) |

2.0 (1.2 to 3.3) |

0.013 | 22.2 (18.5 to 26.5) |

1.0 (0.7 to 1.5) |

0.933 | ||

| College grad or more | 469 (34.6) | 6.8 (4.7 to 9.7) |

Ref | 18.9 (15.2 to 23.3) |

Ref | ||||

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Married | 716 (47.8) | 7.6 (5.6 to 10.3) |

0.0016 | Ref | 19.0 (15.8 to 22.8) |

0.1686 | Ref | ||

| Widowed, divorced or separated | 254 (18.8) | 10.2 (6.8 to 15.1) |

1.3 (0.7 to 2.6) |

0.392 | 20.9 (15.3 to 27.9) |

1.1 (0.6 to 1.9) |

0.693 | ||

| Never married | 345 (24.1) | 14.3 (10.0 to 20.2) |

1.4 (0.8 to 2.6) |

0.273 | 24.9 (19.0 to 31.9) |

1.1 (0.7 to 1.9) |

0.566 | ||

| Living with partner | 135 (9.3) | 20.8 (12.7 to 32.0) |

1.5 (0.7 to 2.9) |

0.286 | 28.6 (19.5 to 39.8) |

1.0 (0.6 to 1.7) |

0.925 | ||

| Household income | |||||||||

| $0–$19 999 | 251 (20.3) | 16.9 (11.7 to 23.7) |

0.0311 | 0.9 (0.4 to 1.9) |

0.746 | 28.6 (21.7 to 36.8) |

0.1188 | 1.2 (0.6 to 2.2) |

0.660 |

| $20 000–$44 999 | 358 (25.7) | 12.0 (8.4 to 17.0) |

0.6 (0.3 to 1.3) |

0.219 | 19.5 (15.1 to 24.8) |

0.7 (0.4 to 1.2) |

0.158 | ||

| $45 000–$74 999 | 356 (24.8) | 9.0 (6.0 to 13.2) |

0.6 (0.3 to 1.2) |

0.138 | 22.0 (16.9 to 28.1) |

0.9 (0.6 to 1.5) |

0.688 | ||

| ≥$75 000 | 452 (29.2) | 8.5 (5.7 to 12.6) |

Ref | 19.7 (15.3 to 25.0) |

Ref | ||||

| Household savings | |||||||||

| $0–$4999 | 578 (42.9) | 17.2 (13.6 to 21.6) |

<0.0001 | 1.9 (1.2 to 3.1) |

0.010 | 27.6 (23.2 to 32.6) |

0.0011 | 1.2 (0.8 to 1.9) |

0.349 |

| ≥$5000 | 827 (57.1) | 6.9 (5.0 to 9.3) |

Ref | 18.0 (14.8 to 21.8) |

Ref | ||||

| COVID-related stressor score | |||||||||

| Low | 460 (31.2) | 4.0 (2.2 to 7.0) |

<0.0001 | Ref | 12.4 (8.9 to 17.0) |

<0.0001 | Ref | ||

| Medium | 544 (37.0) | 8.6 (6.2 to 11.8) |

2.0 (1.0 to 4.0) |

0.046 | 17.4 (13.6 to 22.0) |

1.4 (0.9 to 2.3) |

0.139 | ||

| High | 446 (31.8) | 20.5 (16.1 to 25.8) |

4.5 (2.3 to 8.8) |

<0.0001 | 35.7 (30.2 to 41.6) |

3.3 (2.1 to 5.1) |

<0.0001 | ||

| Household size (mean) | 3.2 | 1.0 (0.8 to 1.1) |

0.710 | 1.0 (0.9 to 1.1) |

0.910 | ||||

All percentages are weighted. Missing data: household income (n=33), household savings (n=45) and COVID-19 stressor score (n=3). GED is the general education diploma. COVID-19 stressor score calculated from stressor summation ranging from 0 to 13; categories represent low (score of 0–2), medium (score of 3–4) and high (score of 5–14) exposure to stressors due to COVID-19. GAD defined by a GAD-7 score ≥15. PTSS defined by a four-item PTSD checklist score ≥3. Two-tailed χ2 analysis conducted for significance testing. This analysis is based on data from our COVID-19 and Life stressors Impact on Mental Health and Well-being Study.

PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

COVID-19-related stressors and anxiety disorders

Higher stressor score was positively associated with, and a predictor of, both probable GAD and PTSS. The prevalence of probable GAD was 4% (95% CI 2.2% to 7.0%) among participants with low stressor score, 8.6% (95% CI 6.2% to 11.8%) among participants with medium stressor score and 20.5% (95% CI 16.1% to 25.8%) among participants with high stressor score. High stressor score was a predictor of probable GAD (OR=4.5, 95% CI 2.3 to 8.8) compared with reporting a low stressor score (table 1). High stressor score remained a predictor of probable GAD (OR=3.5, 95% CI 1.8 to 6.9) compared with reporting a low stressor score after including concern about COVID-19 in the model (online supplemental appendix table 1). In the models that included COVID-19-related stressors as a continuous variable, the OR of probable GAD was 1.3 (95% CI 1.2 to 1.4) (online supplemental appendix table 2). Dividing COVID-19-related stressors into two continuous variables depending on the nature of the stressor in the multivariable model produced consistent results for financial stressors (OR=1.4, 95% CI 1.2 to 1.6), and social and emotional stressors (OR=1.2, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.5) (online supplemental appendix table 3).

bmjopen-2020-044125supp001.pdf (83.5KB, pdf)

The prevalence of PTSS was 12.4% (95% CI 8.9% to 17.0%) among participants with low stressor score, 17.4% (95% CI 13.6% to 22.0%) among participants with medium stressor score and 35.7% (95% CI 30.2% to 41.6%) among participants with high stressor score. Reporting a high stressor score, compared with a low stressor score, was a predictor of PTSS (OR=3.3, 95% CI 2.1 to 5.1) (table 1). High stressor score remained a predictor of PTSS (OR=2.7, 95% CI 1.7 to 4.3) compared with reporting a low stressor score after including concern about COVID-19 in the model (online supplemental appendix table 1). In the models that included COVID-19-related stressors as a continuous variable, the OR was 1.3 (95% CI 1.2 to 1.4) (online supplemental appendix table 2). Dividing COVID-19-related stressors into two continuous variables, the multivariable model depending on the nature of the stressor produced consistent results for financial stressors (OR=1.3, 95% CI 1.2 to 1.6), and social and emotional stressors (OR=1.3, 95% CI 1.1 to 1.5) (online supplemental appendix table 3).

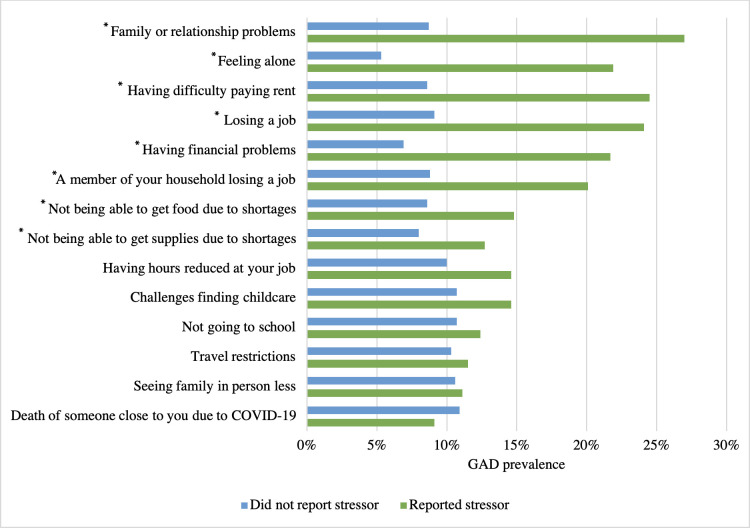

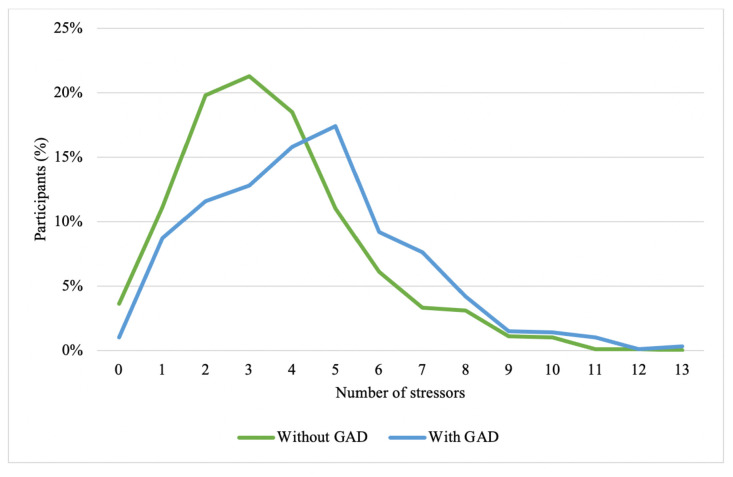

Figure 1 shows that reporting any COVID-19-related stressor, except for experiencing travel restrictions, was associated with higher probable GAD prevalence. The greatest difference in probable GAD prevalence by COVID-19-related stressor was between participants who reported having family or relationship problems (prevalence=27%, 95% CI 19.6% to 36.1%) compared with participants who did not report family or relationship problems (prevalence=8.7%, 95% CI 6.9% to 10.9%). Other stressors leading to a significant difference in probable GAD prevalence included feeling lonely, having difficulty paying the rent, losing a job, having financial problems and a household member losing a job. Figure 2 shows that participants who reached the threshold for probable GAD reported, on average, experiencing a higher number of stressors compared with participants who did not reach the threshold for probable GAD.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of probable generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) for persons reporting different COVID-19 stressors. *P<0.05. GAD defined by a GAD-7 score of ≥15. Percentages are weighted to the US population. This analysis is based on data from the COVID-19 and Life stressors Impact on Mental Health and Well-being Study.

Figure 2.

Distribution of number of stressors among participants depending on whether they reported symptoms consistent with probable generalised anxiety disorder (GAD) status. GAD defined by a GAD-7 score of ≥15. Percentages are weighted to the US population. This analysis is based on data from the COVID-19 and Life stressors Impact on Mental Health and Well-being Study.

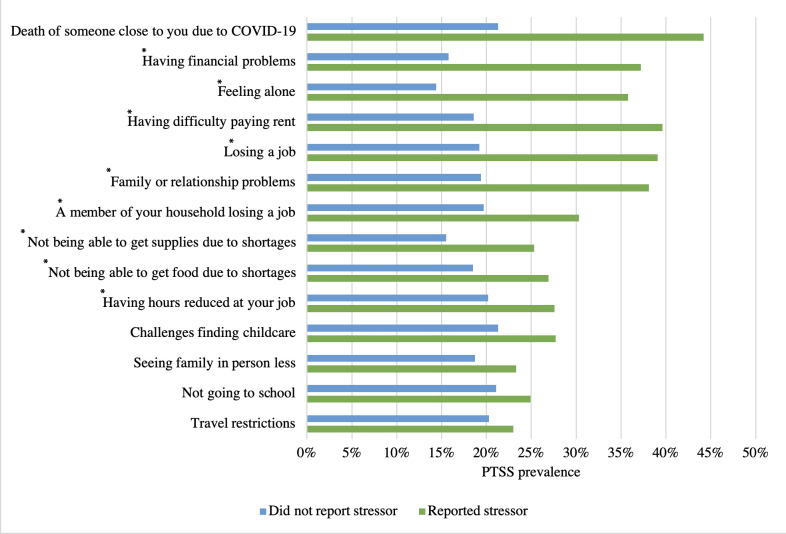

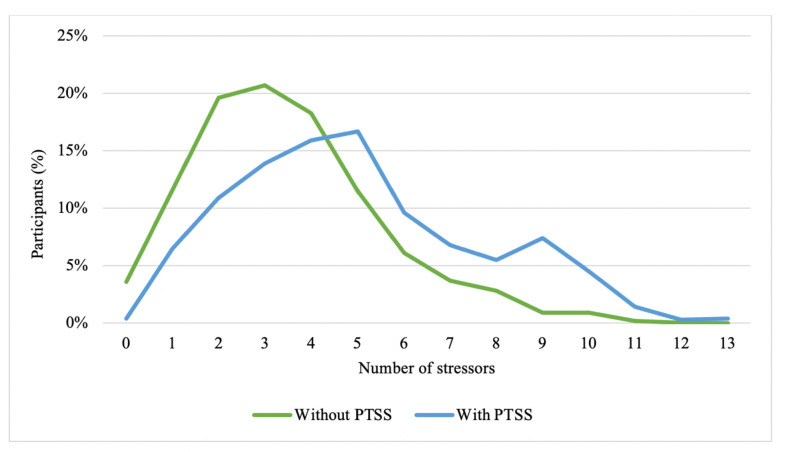

Figure 3 shows that reporting any COVID-19-related stressor was associated with higher PTSS prevalence. The greatest significant difference in PTSS prevalence was between participants who reported having financial problems (prevalence=37.2%, 95% CI 31.1% to 43.7%) compared with participants who did not report having financial problems (prevalence=15.8%, 95% CI 13.2% to 18.8%). Other stressors leading to a significant difference in PTSS prevalence included feeling along, losing a job, and having difficulty paying the rent. Figure 4 shows that participants who reached the threshold for PTSS reported, on average, experienced a higher number of stressors compared with participants who did not reach the threshold for PTSS.

Figure 3.

Prevalence of post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) for persons reporting different COVID-19 stressors. *P<0.05. PTSS defined by a four-item PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) checklist score of 23. Percentages are weighted to the US population. This analysis is based on data from our COVID-19 and Life stressors Impact on Mental Health and Well-being Study.

Figure 4.

Distribution of number of stressors among participants depending on whether they reach the cut-off for post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) status. PTSS defined by a four-item PTSD (post-traumatic stress disorder) checklist score of 23. Percentages are weighted to the US population. This analysis is based on data from the COVID-l9 and Life stressors Impact on Mental Health and Well-being Study.

Discussion

In a survey of a representative sample of adults in the USA conducted between 31 March and 13 April 2020, 10.9% of adults reported a score indicative of probable GAD and 21% reported PTSS. These numbers are significantly higher than the expected prevalence of anxiety disorders in the USA. For example, the National Comorbidity Survey replication estimated that the prevalence of GAD and PTSD in the USA were 3.1% and 3.5%, respectively (collected before COVID-19).26 Another analysis showed that the 12-month prevalence of GAD in the USA in 2017 was 4%.27 However, our results are lower than a recent analysis by Twenge and Joiner, which found that, compared with 2019, adults in the USA were more than three times as likely to screen positive for anxiety (using GAD-2) between 23 April and May 2020. The study reports that on the week of 21 May 2020, 29.4% of participants screened positive for GAD.18 The difference in results can potentially be due to the higher threshold for screening positive for probable GAD by our screening tool.

We also found that COVID-19-related stressors were associated with participants reporting more symptoms of GAD or PTSS. The prevalence of GAD was four times higher among participants reporting five or more stressors compared with participants reporting two or fewer stressors. The prevalence of PTSS was about three times higher among participants reporting five or more stressors compared with participants reporting two or fewer COVID-19-related stressors. This reinforces the hypothesis that the pandemic behaves like a mass traumatic event, wherein experiences related to COVID-19 and its consequences are directly linked to adverse mental health consequences. These results are consistent with other epidemiologic analyses that studied COVID-19 stressors and mental health. For example, Fitzpatrick et al found in a nationally representative sample that fear of COVID-19 was linked to both depression and anxiety, and that more than 25% of participants reported moderate to severe anxiety symptoms, which may warrant clinical treatment.28 Another study found that between 13 April and 19 May 2020, young adults (18–20 years) reported high levels of GAD (45.4% with a 10 score cut-off) and PTSD symptoms (31.8% with a 45 PCL-C score cut-off).16 28 Conditions associated with anxiety disorders often also lead to depression.29 This is consistent with our analysis that found that the prevalence of depression symptoms has risen during the study period as well.30

Our study is consistent with existing literature showing higher prevalence of anxiety disorders following mass traumatic events, even if our results suggest the severity of anxiety disorders due to the COVID-19 pandemic is greater than that previously recorded after other mass traumas.1 Agyapong et al reported that the prevalence of GAD after 1 month following a wildfire—which physically, emotionally and economically affected the community—was 19.8%.31 Their results were based on using a score of 10 points on the GAD-7 scale as the cut-off. Using the same cut-off, the prevalence of probable GAD in our analysis rises to 25%. Silver et al found that 17% of the US population that lives outside New York city reported PTSS 2 months after the September 11 terrorist attack.32

Our study complements studies from China showing that COVID-19 has led to adverse psychological consequences.10 33 We add to the literature by quantifying the probable prevalence of GAD and PTSS as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded in the USA. Our results also support analysis from Nelson et al showing the widespread concerns and stressors due to COVID-19 in the USA.11 Our work both describes the experience of particular stressors and quantifies their contribution to the risk of developing anxiety disorders in the country. In particular, we show that financial (eg, having difficulty paying rent) and social and emotional (eg, feeling lonely) stressors contribute to higher rates of both probable GAD and PTSS, which aligns with existing literature.6

These results should be considered with the following limitations in mind. First, our study uses screeners for GAD and PTSS. A definitive diagnosis of either will require clinical assessment. As such, these results should be confirmed in a representative sample using diagnostic tools. However, both screening questionnaires in our analysis are validated tools used extensively to assess the prevalence of GAD and PTSS in the population.24 25 Second, the use of a prespecified panel can lead to selection bias. However, the AmeriSpeak Panel has been used reliably for years to provide representative samples of the USA.34 Third, there are a large number of other covariates—including features of context such as estimates of pandemic severity—that could be considered to more fully assess the determinants of anxiety disorders in this study. This is beyond the scope of the paper but potentially a fruitful direction for future work. Fourth, our post-only design, which does not allow for information on the mental health status of the participants prior to the pandemic, suggests that we cannot causally link the pandemic, and the policies implemented to tackle it, to a subsequent increased risk of developing anxiety disorders. However, the specificity of stressors reported and the high risk of developing of reported anxiety disorders, consistent with previous knowledge and expectation, strongly suggest that we are observing reliable associations that can be further examined in subsequent longitudinal work.

Conclusion

The prevalence of anxiety disorders as the COVID-19 pandemic unfolded in the USA is substantially higher than the expected baseline prevalence in the USA and of the burden reported following other mass traumatic events. This potentially reflects the scale of the pandemic, the ubiquity of the impact of the policies implemented to tackle it, and the economic and social consequences of both. Persons experiencing COVID-19-related stressors, particularly financial, and social and emotional stressors, were more likely to report both probable GAD and PTSS, indicating the critical role these stressors are play in increasing the risk of developing anxiety disorders in the USA. Mitigation and recovery policies should take into account the mental health toll the pandemic had on the US population.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Twitter: @SalmaMHAbdalla

Contributors: CKE and SMA developed the first draft of the survey. SG reviewed the survey. SMA conducted the data analysis and wrote the manuscript draft. CKE, GHC and SG contributed to study conception and manuscript drafting. All authors acknowledge full responsibility for the analyses and interpretation of the report. The corresponding author attests that all listed authors meet authorship criteria and that no others meeting the criteria have been omitted.

Funding: The research was funded by the Rockefeller Foundation-Boston University 3-D Commission (grant number 2019 HTH 024). The Rockefeller Foundation had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis and interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Competing interests: The authors declare support from the Rockefeller Foundation-Boston University 3-D Commission; no financial relationships with any organisation that might have an interest in the submitted work in the previous 3 years; no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Data availability statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Email the corresponding author for more details.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

Ethics approval

The institutional review boards of NORC and Boston University Medical Campus (H-39986) approved the study. NORC obtained written consent from study participants when they first enrolled in the AmeriSpeak Panel.

References

- 1.Goldmann E, Galea S. Mental health consequences of disasters. Annu Rev Public Health 2014;35:169–83. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ni MY, Kim Y, McDowell I, et al. Mental health during and after protests, riots and revolutions: a systematic review. Aust N Z J Psychiatry 2020;54:232–43. 10.1177/0004867419899165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Peng EY-C, Lee M-B, Tsai S-T, et al. Population-based post-crisis psychological distress: an example from the SARS outbreak in Taiwan. J Formos Med Assoc 2010;109:524–32. 10.1016/S0929-6646(10)60087-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.David D, Mellman TA, Mendoza LM, et al. Psychiatric morbidity following Hurricane Andrew. J Trauma Stress 1996;9:607–12. 10.1002/jts.2490090316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jeong H, Yim HW, Song Y-J, et al. Mental health status of people isolated due to middle East respiratory syndrome. Epidemiol Health 2016;38:e2016048. 10.4178/epih.e2016048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Viseu J, Leal R, de Jesus SN, et al. Relationship between economic stress factors and stress, anxiety, and depression: moderating role of social support. Psychiatry Res 2018;268:102–7. 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jalloh MF, Li W, Bunnell RE, et al. Impact of Ebola experiences and risk perceptions on mental health in Sierra Leone, July 2015. BMJ Glob Health 2018;3:e000471. 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000471 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galea S, Brewin CR, Gruber M, et al. Exposure to hurricane-related stressors and mental illness after Hurricane Katrina. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2007;64:1427–34. 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Trappler B, Friedman S. Posttraumatic stress disorder in survivors of the Brooklyn bridge shooting. Am J Psychiatry 1996;153:705–7. 10.1176/ajp.153.5.705 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cao W, Fang Z, Hou G, et al. The psychological impact of the COVID-19 epidemic on college students in China. Psychiatry Res 2020;287:112934. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Nelson LM, Simard JF, Oluyomi A, et al. US public concerns about the COVID-19 pandemic from results of a survey given via social media. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:1020. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1369 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okely JA, Corley J, Welstead M, et al. Change in physical activity, sleep quality, and psychosocial variables during COVID-19 lockdown: evidence from the Lothian birth cohort 1936. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;18:210. 10.3390/ijerph18010210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.García-Fernández L, Romero-Ferreiro V, Padilla S, et al. Gender differences in emotional response to the COVID-19 outbreak in Spain. Brain Behav 2021;11:e01934. 10.1002/brb3.1934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li J, Yang Z, Qiu H, et al. Anxiety and depression among general population in China at the peak of the COVID-19 epidemic. World Psychiatry 2020;19:249–50. 10.1002/wps.20758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wang C, Pan R, Wan X, et al. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17. 10.3390/ijerph17051729. [Epub ahead of print: 06 Mar 2020]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liu CH, Zhang E, Wong GTF, et al. Factors associated with depression, anxiety, and PTSD symptomatology during the COVID-19 pandemic: clinical implications for U.S. young adult mental health. Psychiatry Res 2020;290:113172. 10.1016/j.psychres.2020.113172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boardman JD, Finch BK, Ellison CG, et al. Neighborhood disadvantage, stress, and drug use among adults. J Health Soc Behav 2001;42:151–65. 10.2307/3090175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Twenge JM, Joiner TE. U.S. census Bureau-assessed prevalence of anxiety and depressive symptoms in 2019 and during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. Depress Anxiety 2020;37:954–6. 10.1002/da.23077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salari N, Khazaie H, Hosseinian-Far A, et al. The prevalence of stress, anxiety and depression within front-line healthcare workers caring for COVID-19 patients: a systematic review and meta-regression. Hum Resour Health 2020;18:100. 10.1186/s12960-020-00544-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lasheras I, Gracia-García P, Lipnicki D, et al. Prevalence of anxiety in medical students during the covid-19 pandemic: a rapid systematic review with meta-analysis. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020;17:6603–12. 10.3390/ijerph17186603 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Salari N, Hosseinian-Far A, Jalali R, et al. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Global Health 2020;16:57. 10.1186/s12992-020-00589-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fiorillo A, Sampogna G, Giallonardo V, et al. Effects of the lockdown on the mental health of the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy: results from the comet collaborative network. Eur Psychiatry 2020;63:e87. 10.1192/j.eurpsy.2020.89 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galea S, Tracy M, Norris F, et al. Financial and social circumstances and the incidence and course of PTSD in Mississippi during the first two years after Hurricane Katrina. J Trauma Stress 2008;21:357–68. 10.1002/jts.20355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Spitzer RL, Kroenke K, Williams JBW, et al. A brief measure for assessing generalized anxiety disorder: the GAD-7. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:1092–7. 10.1001/archinte.166.10.1092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bliese PD, Wright KM, Adler AB, et al. Validating the primary care posttraumatic stress disorder screen and the posttraumatic stress disorder checklist with soldiers returning from combat. J Consult Clin Psychol 2008;76:272–81. 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kessler RC, Chiu WT, Demler O, et al. Prevalence, severity, and comorbidity of 12-month DSM-IV disorders in the National comorbidity survey replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2005;62:617–27. 10.1001/archpsyc.62.6.617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ruscio AM, Hallion LS, Lim CCW, et al. Cross-sectional comparison of the epidemiology of DSM-5 generalized anxiety disorder across the globe. JAMA Psychiatry 2017;74:465–75. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Fitzpatrick KM, Harris C, Drawve G. Fear of COVID-19 and the mental health consequences in America. Psychol Trauma 2020;12:S17–21. 10.1037/tra0000924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bueno-Notivol J, Gracia-García P, Olaya B, et al. Prevalence of depression during the COVID-19 outbreak: a meta-analysis of community-based studies. Int J Clin Health Psychol 2021;21:100196. 10.1016/j.ijchp.2020.07.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ettman CK, Abdalla SM, Cohen GH, et al. Prevalence of depression symptoms in US adults before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e2019686. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Agyapong VIO, Hrabok M, Juhas M, et al. Prevalence rates and predictors of generalized anxiety disorder symptoms in residents of Fort mcmurray six months after a wildfire. Front Psychiatry 2018;9:345. 10.3389/fpsyt.2018.00345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Silver RC, Holman EA, McIntosh DN, et al. Nationwide longitudinal study of psychological responses to September 11. JAMA 2002;288:1235–44. 10.1001/jama.288.10.1235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lai J, Ma S, Wang Y, et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3:e203976. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.NORC.org . AmeriSpeak: NORC’s Breakthrough Panel-Based Research Platform. Available: https://www.norc.org/Research/Capabilities/Pages/amerispeak.aspx [Accessed 18 May 2020].

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

bmjopen-2020-044125supp001.pdf (83.5KB, pdf)

Data Availability Statement

Data are available on reasonable request. Email the corresponding author for more details.