Abstract

Purpose

Despite a few recent reports of patients harboring truncating variants in NSD2, a gene considered critical for the Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome (WHS) phenotype, the clinical spectrum associated with NSD2 pathogenic variants remains poorly understood.

Methods

We collected a comprehensive series of 18 unpublished patients carrying heterozygous missense, elongating, or truncating NSD2 variants; compared their clinical data to the typical WHS phenotype after pooling them with ten previously described patients; and assessed the underlying molecular mechanism by structural modeling and measuring methylation activity in vitro.

Results

The core NSD2-associated phenotype includes mostly mild developmental delay, prenatal-onset growth retardation, low body mass index, and characteristic facial features distinct from WHS. Patients carrying missense variants were significantly taller and had more frequent behavioral/psychological issues compared with those harboring truncating variants. Structural in silico modeling suggested interference with NSD2’s folding and function for all missense variants in known structures. In vitro testing showed reduced methylation activity and failure to reconstitute H3K36me2 in NSD2 knockout cells for most missense variants.

Conclusion

NSD2 loss-of-function variants lead to a distinct, rather mild phenotype partially overlapping with WHS. To avoid confusion for patients, NSD2 deficiency may be named Rauch–Steindl syndrome after the delineators of this phenotype.

INTRODUCTION

Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome (WHS, also known as 4p-syndrome, OMIM 194190) caused by partial deletions of the short arm of chromosome 4 is one of the first microscopically recognized structural chromosomal disorders, and was named after Ulrich Wolf (Freiburg, Germany) and Kurt Hirschhorn (New York, NY, USA), who first described it in 1965.1,2 Hallmarks of the syndrome are prenatal-onset growth deficiency, microcephaly, intellectual disability (ID), epilepsy, muscular hypotonia and hypotrophy, facial clefts, congenital heart defects and other malformations, as well as a very characteristic craniofacial gestalt, often described as resembling a Greek helmet.3 With the advent of molecular cytogenetics a number of patients with smaller deletions encompassing 4p16.3 were identified, with deletions below 3.5 Mb found to be associated with a milder phenotype without major malformations.3 Following an observation by Dian Donnai (Manchester, UK)4 individuals described as having Pitt–Rogers–Danks syndrome were shown to also harbor 4p16.3 microdeletions sizing at least 3.7 Mb5 and, as pointed out by Agatino Battaglia (Pisa, Italy) and John C. Carey (Salt Lake City, UT, USA), are actually clinically indistinguishable from WHS.6 Further refinement of the WHS critical region hinted at NSD2 (also named WHSC1 or MMSET, OMIM *602952) as the gene possibly responsible for part of the manifestations of WHS, including growth retardation, ID, and possibly susceptibility to infections.7–10 This hypothesis was supported by a role for NSD2 in neuronal development as well as in the regulation of cellular proliferation in vitro.11–13 A total of eight truncating, two splicing, and six missense variants were listed among many others in sequencing studies of patient cohorts with neurodevelopmental disorders, growth abnormality, or congenital heart defects without deep phenotyping information (Table S1).

Recently, eight individual patients with developmental delay (DD) and growth retardation carrying truncating or protein-elongating variants in NSD2 have been described,14–18 with phenotypes that partially overlap with those of individuals carrying very small chromosomal deletions encompassing NSD2.8–10

However, the lack of larger systematic patient series and functional validation is hampering the understanding of the phenotype associated with NSD2 constitutional variants. Here we report 18 additional deep-phenotyped individuals carrying heterozygous (likely) pathogenic NSD2 variants, including a prenatal and two familial cases, together with in silico and in vitro data providing insight into the underlying pathomechanism and genotype–phenotype correlations.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

The 18 previously undescribed patients with pathogenic NSD2 variants reported in this study were identified by research or diagnostic exome or Mendeliome sequencing in various laboratories and collected via GeneMatcher (see Web Resources). When no developmental testing was performed, the degree of ID was estimated using the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5) severity levels for ID (see Web Resources). Standard deviation scores for growth parameters were calculated based on the data sets provided by the Swiss Society of Pediatrics, which combine World Health Organization, Swiss, and German population data (see Web Resources). The facial overlay Fig. 4b was obtained using the Face2Gene RESEARCH application (FDNA Inc., Boston, MA, USA) taking one frontal photo for each patient at the youngest available age.

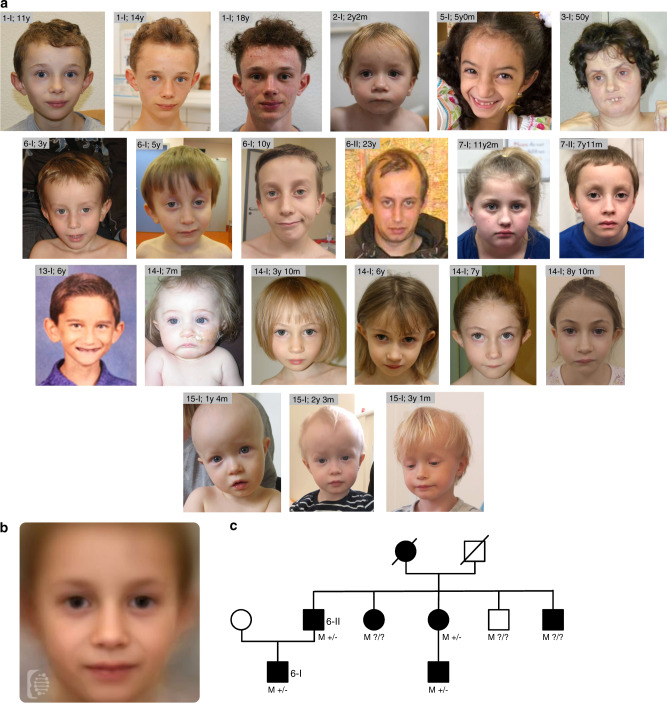

Fig. 4. Clinical data.

(a) Facial features of the affected individuals reported in this study. The age in years (y) and months (m) is reported beside each patient ID. (b) Combined facial gestalt obtained by combining frontal photos using the Face2Gene online research tool (see Materials and Methods and Web Resources). Photos from 12 different patients, including those depicted in (a), were used for this purpose. (c) Family tree of family number 6 in this study. M+/−/? = presence (+), absence (−), or unknown status (?) for the p.Asp1158Glyfs*11 variant in each NSD2 allele. Clinically affected individuals are shown as full symbols.

NSD2 variant nomenclature refers to the NM_133330.2 transcript and pathogenicity classification is based on the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics/Association for Molecular Pathology (ACMG/AMP) guidelines.19 Structural analysis of NSD2 variants was performed using SwissModel, RasMol, and Smart (see Web Resources). While the experimental crystal structure of the NSD2 N-methyltransferase domain was available (Protein Data Bank, PDB: 5LSU), the PHD and PWWP domains were modeled using the homologous domains from TRIM24 (PDB: 4ZQL) and NSD3 (PDB code: 2DAQ), respectively.

GST fusion proteins were obtained as described in the Supplementary methods. In vitro methylation assays were performed as described in Mazur et al.20 and the Supplemental methods using reagents listed in Table S2.

The data in Fig. 2n, p, r, t are represented as mean ± SD of two independent biological replicates; statistical significance was tested by one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by two-tailed Dunnett’s test without adjusting for multiple testing. The data in Fig. 3c–e are represented as mean ± SD. Groups in Fig. 3e were compared by homoscedastic two-tailed Student’s t-test after testing for equal variance by F-test.

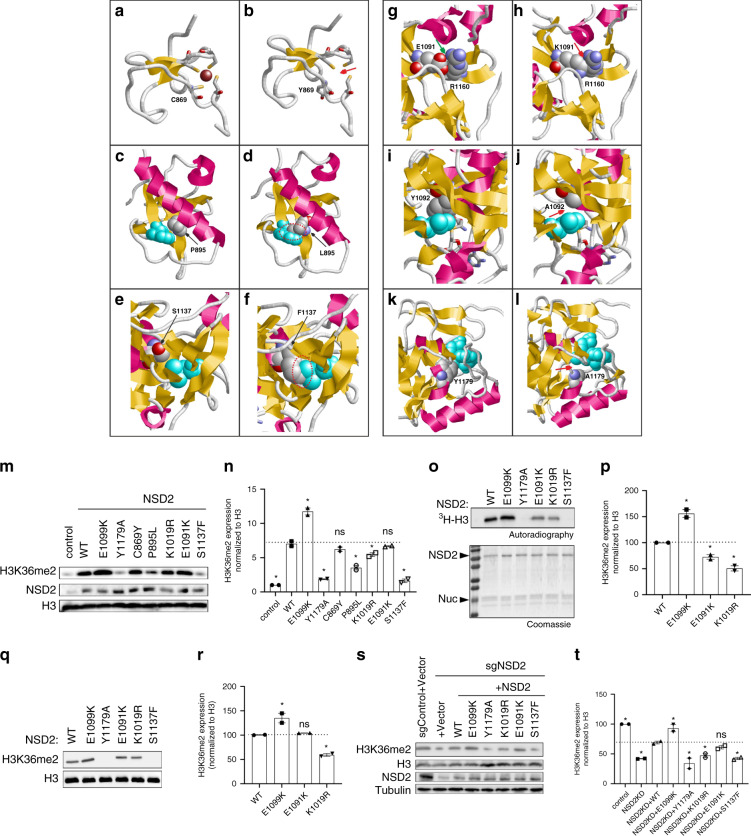

Fig. 2. Structural and functional effect of two synthetic and four naturally occurring pathogenic NSD2 missense variants.

(a) Wild-type (WT) Cys869 is one of four cysteines that tetrahedrally coordinate a zinc ion (Cys846, Cys849, Cys869, Cys872 are shown in stick presentation; the Zn2+ is depicted as a brown ball). (b) The variant Tyr869 adopts a different sidechain orientation resulting in a loss of the zinc ion (marked by a red arrow). (c) WT Pro895 is located in spatial proximity of Trp885 (cyan). (d) The longer Leu895 sidechain present in the variant results in steric clashes with Trp885 (marked by a red dotted circle). (e) WT Ser1137 is located in spatial proximity of Leu1163 (cyan). (f) The bulkier Phe1173 sidechain present in the variant results in steric clashes with Leu1163 (marked by a red dotted circle). (g) WT Glu1091 forms a salt bridge to Arg1160 (green arrow), which is disrupted in the (h) Lys1091 variant and steric clashes are formed instead (red arrow). (i) WT Tyr1092 forms tight van der Waals interactions with Leu1120 (cyan), which are lost in the synthetic (j) Ala1092 variant11 (the site of altered interactions is denoted by a red arrow). (k) WT Tyr1179 forms stabilizing interactions to S-adenosylmethionine (SAM, cyan). (l) The shorter sidechain in the synthetic Ala1179 variant11 results in a loss of interactions with the SAM cofactor (red arrow), which is expected to result in a drastic loss of enzymatic activity. (m) Western analysis with the indicated antibodies of whole-cell extracts (WCEs) from 293 T cells overexpressing vector control, full-length WT NSD2, or NSD2 mutants as indicated. Histone H3 is shown as a loading control. (n) Quantification of western blot data in (m). (o) In vitro methylation assay with recombinant WT NSD2 or mutant NSD2 derivatives as indicated on recombinant nucleosomes (rNuc) as substrates. Top panel, 3H-SAM is the methyl donor and methylation is visualized by autoradiography and indicated as 3H-H3. Bottom panel, Coomassie stain of proteins in the reaction. (p) Quantification of all detectable bands in the autoradiography in (o). (q) Western analysis with the indicated antibodies of in vitro methylation assay with nonradiolabeled SAM. (r) Quantification of all detectable bands in the western blot data in (q). (s) Western analysis with the indicated antibodies of WCEs from WT or NSD2 deficient HT1080 cells complemented with CRISPR-resistant NSD2 (WT or mutants), or control as indicated. Histone H3 and tubulin are shown as loading controls. (t) Quantification of western blots in (s). The data in (n, p, r, t) are represented as mean ± SD of two independent experiments. *p < 0.05 based on a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by two-tailed Dunnett’s test.

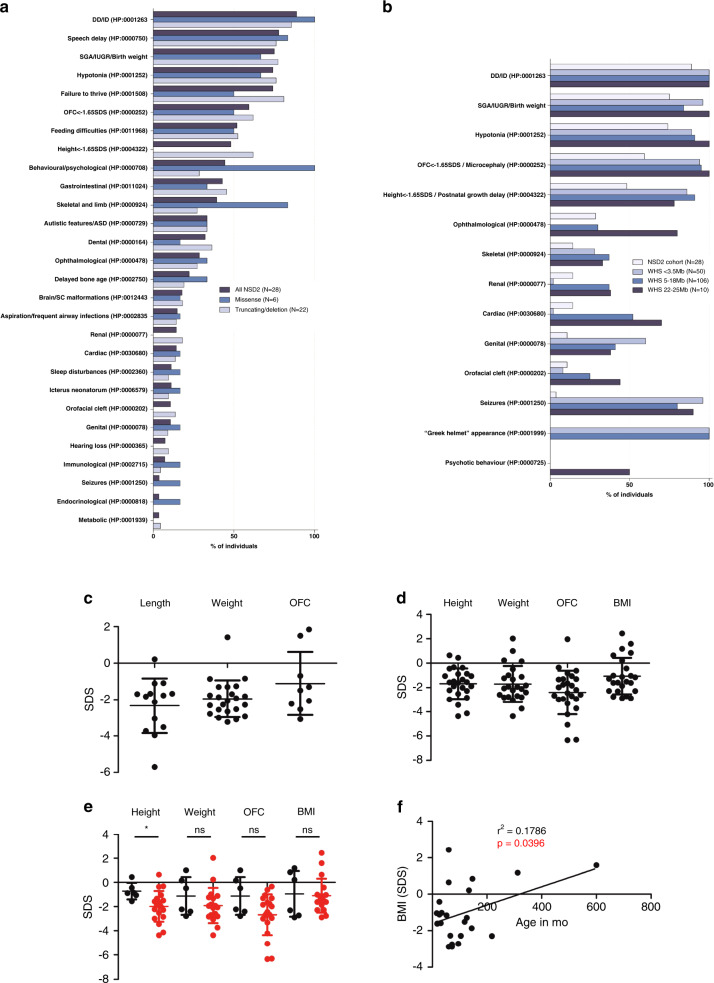

Fig. 3. Phenotypic features and growth parameters of the individuals carrying NSD2 pathogenic variants and comparison with Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome (WHS).

The diagram in (a) summarizes the phenotypic features of the individuals described in this study (18 additional patients together with 10 previously reported individuals) based on the type of NSD2 variant carried. In (b) all individuals are compared with WHS patients, subdivided according to the size of the 4p deletion carried, as reported in Zollino et al.3 Data in (a) and (b) are expressed as percentages. Growth parameters at birth (c; included the parameters at termination of pregnancy for individual 16-I) and at last visit (d) are reported. The average measures for all combined individuals standard deviation score (SDS [SD]) were length (L): -2.3 (1.5); weight (W): -2.0(1.0); occipitofrontal circumference (OFC): -1.1(1.7); gestational weeks (GW): 38.5(3.8) at birth and height (H): -1.7(1.3); W: -1.7(1.5); OFC: -2.4(1.8); body mass index (BMI): -1(1.5) at last visit. (e) Comparison of the growth parameters at last visit for patients carrying missense variants (black) compared with patients carrying other variants as well as deletions encompassing NSD2 (red). *p value < 0.05 as tested by two-tailed Student’s t-test. The data in (c–e) are expressed as SDS based on the respective growth charts. Lines and whiskers represent mean ± SD. (f) Linear correlation analysis between age and BMI and last visit. ASD DD/ID developmental delay/intellectual disability, IUGR intrauterine growth restriction, SC spinal cord, SGA small for gestational age.

The graphs in Figs. 2n, p, r, t and 3a–f were generated using GraphPad Prism version 5.00 for Windows, (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). All statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Prism, except for F- and t-tests, which were performed using Microsoft© Excel.

RESULTS

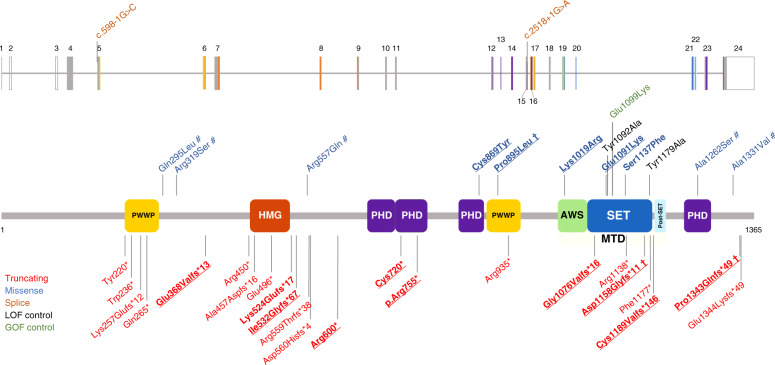

We describe 18 patients, 16 of whom unrelated, carrying ultrarare (absent in gnomAD) pathogenic or likely pathogenic NSD2 variants (Table S3). Of these, 6 carried 5 different missense variants while 12 carried 10 different truncating variants. Nine of the truncating and four of the missense variants were not reported previously (Fig. 1). Variant inheritance could not be determined in 4/18 cases, and was confirmed parental in 3/18 cases and de novo in 11/18 cases.

Fig. 1. Localization of the NSD2 variants.

The diagram shows the structure of the NSD2 gene (above) and protein (below, isoform 1, encoded by the NM_133330.2 transcript) together with the variants discussed in this study as well as variants that have previously been reported in large sequencing studies. The variants carried by the 18 additional individuals described in this study are in bold. Observed germline variants absent in the HGMD database are underlined. † Shared by more than one patient; # variant of uncertain significance (VUS)/likely benign. The observed pathogenic missense variants we found map to three distinct domains of NSD2: a PHD zinc-finger domain (residues 831–875), a PWWP domain (residues 880–942), and the catalytic methyltransferase domain (residues 1011–1203; composed of three subdomains, namely an AWS, a SET, and a post-SET domain). The color coding of the variants and protein domains is reported in the legend. AWS Associated With SET domain (IPR006560), GOF gain of function, HMG high mobility group box domain (IPR009071), LOF loss of function, MTD catalytic methyltransferase domain, composed by the AWS, SET and a post-SET domain, PHD zinc-finger domain, Plant-HomeoDomain type (IPR001965), PWWP proline–tryptophan–tryptophan–proline domain (IPR000313), SET Su(Var)3-9, enhancer-of-zeste, trithorax domain (IPR001214). Domains were annotated according to the Uniprot databank (see Web Resources).

NSD2 is the principal enzyme that dimethylates histone H3 at lysine 36 (H3K36me2)11 in most cell types and tissues.21 H3K36me2 is an evolutionarily conserved histone modification linked to transcriptional activation. The (likely) pathogenic missense variants we found map to three distinct domains of NSD2. The Cys869Tyr (patient 1-I) substitution disrupts zinc binding within a PHD finger domain (residues 831-875) and hence induces improper folding and loss of function for this domain. Although the function of the NSD2 PHD domain is unknown, these domains are virtually always found on chromatin-associated proteins and may function as epigenetic reader domains (Fig. 2a, b). The Pro895Leu variant (patients 7-I and 7-II) is located in the core of one of NSD2’s PWWP domains (Fig. 2c), another motif that generally functions as an epigenetic reader.22 The leucine substitution at Pro895 is predicted to destabilize the domain through steric clashes with the adjacent Trp885 (Fig. 2d).

All remaining missense variants are located within the methyltransferase domain of NSD2. Lys1019Arg (patient 12-I) is located in a loop of the methyltransferase domain that exhibits high local mobility or is entirely missing in the isolated NSD2 crystal structure. This hampers reliable modeling but suggests that this region is flexible and might become stabilized upon protein–protein interactions, such as binding to the nucleosome substrate. Ser1137 is located in the domain’s core (Fig. 2e) and substitution to phenylalanine (p.Ser1137Phe, patient 10-I) is predicted to result in steric clashes with the adjacent Leu1163 residue (Fig. 2f), leading to domain destabilization. Glu1091 forms a salt bridge to Arg1160 in the wild-type structure (Fig. 2g), which is disrupted due to the charge inversion in the Glu1091Lys variant (patient 5-I, Fig. 2h). In addition, the longer Lys1091 sidechain forms steric clashes with Arg1160, which are expected to additionally destabilize the methyltransferase domain. To corroborate our in silico and in vitro data, we also tested previously functionally characterized substitutions within the methyltransferase domain, namely Glu1099Lys, Tyr1092Ala, and Tyr1179Ala. Glu1099Lys is a recurrent variant found somatically in multiple cancer types including childhood leukemia and enhances methylation activity to alter global histone methylation.23 Molecular modeling23 suggested that the positively charged lysine may disrupt the favorable histone–enzyme interactions leading to a gain of function. Tyr1092Ala and Tyr1179Ala were not previously identified in patients but had been shown to abrogate catalytic activity based on homology to other SET domain protein lysine methyltransferase enzymes.11 Tyr1092 forms tight hydrophobic interactions with Leu1120 in the protein core (Fig. 2I). Due to the shorter sidechain, these interactions are lost in the Ala1092 variant (Fig. 2j) thereby predicted to destabilize the protein domain. Modeling of the Tyr1179Ala variant reveals that Tyr1179 forms direct interactions with the bound methyl donor S-adenosylmethionine (SAM, Fig. 2k). These interactions are lost in the Tyr1179Ala mutant (Fig. 2l), resulting in a predicted strong reduction of cofactor binding and hence loss of enzymatic activity. Based on these data, we postulated that one functional consequence of the NSD2 missense variants identified in patients with developmental disorders might be disruption of NSD2’s ability to generate H3K36me2.

To test this hypothesis, we determined H3K36me2 levels in HEK293T cells transiently transfected with NSD2 wild-type or derivatives harboring the various variants (Fig. 2m, n). Consistent with previous work,11,22 overexpression of wild-type NSD2 and a cancer-related NSD2 gain-of-function mutant (Glu1099Lys [E1099K])23 caused a global increase in H3K36me2. Contrarily, the NSD2 derivatives carrying variants observed in patients, apart from Cys869Tyr [C869Y] (patient 1-I) and Glu1091Lys [E1091K] (patient 5-I), significantly reduced the levels of H3K36me2 (Fig. 2m; quantitation in Fig. 2n). In particular, Ser1137Phe [S1137F] (patient 10-I) largely behaved like the negative control and the known NSD2 catalytic mutant Tyr1179Ala [Y1179A] (Fig. 2m, n). Given that Ser1137Phe (patient 10-I) is located within the SET domain, the data suggest that this variant causes direct impairment of NSD2’s catalytic activity. To test this hypothesis, in vitro methylation assays were performed using a minimal domain of NSD2 that retains enzymatic activity11 and recombinant nucleosomes as substrates. As shown in Fig. 2o and q (quantitation in Fig. 2p and r, respectively), Ser1137Phe (patient 10-I) abrogates NSD2’s ability to methylate nucleosomes in vitro similarly to the previously characterized catalytic mutant Tyr1179Ala [Y1179A]), while Glu1091Lys (patient 5-I) and Lys1019Arg [K1019R] (patient 12-I) showed a modest reduction in methylation of nucleosomes (Fig. 2o–r). Cys869Tyr (patient 1-I) and Pro895Leu (patients 7-I and 7-II) lie outside of the minimal catalytic domain and thus could not be tested in this assay. Next, we used the CRISPR/Cas9 system to generate NSD2-depleted HT1080 cells, which leads to depletion of global H3K36me2, and then complemented these cells with CRISPR-resistant wild-type NSD2 or the DD-associated NSD2 variants to test their role in reconstituting physiologic levels of H3K36me2. In contrast to complementation with wild-type NSD2 and gain-of function NSD2-Glu1099Lys, cells complemented with the DD-associated NSD2 variants were partially to largely compromised in their ability to rescue physiologic H3K36me2 levels, with Glu1091Lys (patient 5-I) being the only variant that did not reach statistical significance (Fig. 2s, t). The Ser1137Phe variant (patient 10-I) completely failed to rescue, indicating that it essentially abolishes enzymatic activity. Overall, these data are consistent with all variants except Cys869Tyr (patient 1-I) compromising to varying degrees the ability of NSD2 to generate H3K36me2, a key epigenetic modification.

The main clinical features of the NSD2 cohort consisting of 18 individuals described here and 10 previously published individuals (8 carrying truncating or protein-elongating variants14–18 and 2 carrying a microdeletion that encompasses the NSD2 gene only10) are summarized in Fig. 3a and compared to patients with WHS due to 4p deletions of different sizes reported in a large series of 166 affected individuals3 (Fig. 3b). Postmortem pathological findings for case 16-I, a male fetus whose pregnancy was terminated at the 27th week of gestation, are shown in Figure S1. Detailed clinical descriptions are provided in the supplement.

In the NSD2 cohort, the average age at last visit (±SD) was 9.3 (±10.3) years and the male to female ratio was 18:10 (male 64%, female 36%). Seventy-five percent of the NSD2 variants were de novo, 14% were inherited from an affected parent, while in 11% of the cases, the inheritance pattern could not be established.

Patients with (likely) pathogenic NSD2 variants shared a similar facial gestalt characterized by a triangular face, broad forehead, high anterior hairline, deeply set eyes, large palpebral fissures, broad arched and laterally sparse eyebrows, periorbital hyperpigmentation, full cheeks, a thin and elevated nasal bridge, smooth short philtrum, prominent cupid bow, thick everted lower lip vermilion, and/or protruding ears (Fig. 4a, b). Noticeably, the facial appearance evolved over time, with older patients developing deeper infraorbital creases. Family 6 comprised a total of 7 clinically similarly affected individuals, with molecular confirmation available for four of them, and represents to date the largest known family affected by this disorder (Fig. 4c). The core phenotype of the NSD2 cohort (>50% of patients) is characterized by DD, intrauterine growth retardation and low birth weight, feeding difficulties, failure to thrive, height and head circumference below the 5th centile (<−1.65 SDS), speech delay, and muscular hypotonia. Although these manifestations are present in WHS as well, the majority of the individuals in the NSD2 cohort lack many of the most common manifestations of WHS such as seizures,3 orofacial clefts, and coloboma, as well as genital, cardiac, and renal malformations and display a distinct facial phenotype that lacks the classical “Greek helmet” aspect. Furthermore, the severity of the ID in the NSD2 cohort was milder compared with patients carrying the most common 4p deletions (between 5 and 18 Mb), who are severely affected in 76% of the cases.3 While individuals 1-I, 13-I, and 14-I harboring the NSD2 Cys869Tyr, p.Cys1183Valfs*146, and p.Arg600* variants respectively, either had an IQ in the lower-normal range (78–81 and 89, respectively) or presented with learning difficulties, individuals old enough for evaluation commonly showed mild ID, with only three individuals presenting with severe ID. The latter carried truncating variants (3-I c.3223_3226dup p.Gly1076Valfs*16; 4-1c.1588_1589dupAA p.Ile532Glyfs*67; Bernardini et al., patient 3, exon 1–20 deletion), which may not be held responsible for the severe ID. Both siblings described as patients 2 and 3 in Bernardini et al. carry in fact the same exon 1–20 deletion, with one sibling showing mild ID, while the other had autism and severe ID.10

Behavioral and psychological issues as well as autistic features were observed in 44% and 33%, respectively, with the most frequently reported manifestations being anxiety (15%), hyperactivity (22%), and aggressiveness (11%). Individual 1-I had suicidal ideations related to his poor academic performance at the age of 11 years. Of note, all the individuals carrying missense variants presented with behavioral and psychological issues (Fig. 3a), compared to 29% of patients with truncating variants or deletions (p value = 0.0031 by two-tailed Fisher’s exact test).

Growth parameters at birth were largely below the norm (Fig. 3c). Feeding difficulties were described in 52% of the affected individuals and may at least in part contribute to the failure to thrive. Short stature and growth retardation persisted later in life (Fig. 3d). Delayed bone age was detected in 6 individuals (22%). Length and occipitofrontal circumference (OFC) at birth as well as all growth parameters at last visit were normally distributed according to a D’Agostino–Pearson omnibus normality test, while birth weight was skewed toward lower values (p = 0.0002). Notably, heterozygotes for missense variants were significantly taller than patients carrying truncating variants as well as small deletions encompassing NSD2 (p = 0.03 by homoscedastic t-test after checking for comparable variance by F-test; Fig. 3e) and none of them fell below the 5th centile for height at last visit. Weight and OFC at last visit were also higher in patients carrying missense variants, although this difference was not statistically significant (p = 0.27 and 0.17, respectively). Finally, a linear regression analysis showed that older patients had significantly higher body mass index (BMI) values (r² = 0.1786, p = 0.0396; Fig. 3f).

Gastrointestinal abnormalities were also quite common (43%), with constipation representing the most frequent manifestation (26%). Ophthalmological abnormalities were observed in 29% of patients and mostly included mild refraction defects and strabismus, while no individual presented with coloboma, which is considered a recurrent feature in WHS (see Fig. 3b). One exception is represented by individual 3-I, who presented with bilateral keratoconus, retinitis pigmentosa, and optic atrophy and received a corneal transplant at the age of 32. Reanalysis of her exome data revealed three rare variants of unknown significance in RHO, KRT3, and UNC45B (Table S3), which were, however, maternally inherited and also present in her healthy sister. Skeletal and limb abnormalities were reported in 39% of the cases. Individual 12-I presented with a craniosynostosis that was surgically corrected at the age of 6 months, which may be explained by the patient’s additional de novo heterozygous AGO2 variant (Table S3). Also, of note, individual 7-II presented with 11 ossified ribs and 6 non-rib-bearing lumbar vertebrae. Dental abnormalities were also quite frequent (32%). Brain and spinal cord malformations were present in 5 individuals (18%) and were mostly of minor importance except for individual 16-I, who presented with vermis hypoplasia. Less frequent manifestations among patients carrying NSD2 pathogenic variants included a history of aspiration, cardiac and renal anomalies, neonatal jaundice, sleep disturbances, hearing loss, genital abnormalities, and orofacial clefts (Table S3). Immunological abnormalities as well as recurrent infections, which represent a common morbidity and mortality cause in WHS,24 were infrequent in the NSD2 cohort, where patient 5-I presented with latex allergy, patient 11-I with low IgA and IgG3 levels, and patients 2-I, 11-I and Derar-1 with recurrent respiratory infections. Seizures, which are common in WHS (Fig. 3b), were reported only in individual 10-I, while individual 15-I presented subclinical electroencephalogram (EEG) abnormalities at the age of 4 4/12 years. Endocrinological abnormalities seem not to be part of the phenotypic spectrum, with only individual 5-I presenting limited signs of precocious puberty at 15 months of age, which were nonprogressive and were associated with a normal endocrine evaluation. Likewise, metabolic abnormalities were only observed in individual 2-I.

DISCUSSION

In this work we describe a large series of patients carrying pathogenic variants in NSD2, thus allowing delineation of the associated manifestations, which include prenatal-onset failure to thrive with all body measurements below the mean and low BMI, mild DD and muscular hypotonia, and a distinct facial gestalt. Furthermore, we provide in silico and in vitro mechanistic data showing loss of histone methylation activity as a common feature of NSD2 deficiency.

The phenotype observed in the NSD2 cohort is consistent with many of the known functions of NSD2. First, NSD2 has long been known to regulate embryonic development and body growth, with heterozygous Nsd2 constitutive knockout mice growing at a much slower rate compared with wild-type littermates, homozygous knockout mice dying in the first days of life,25 and common variants showing strong (p = 10−24) association with height in genome-wide association study (GWAS).26 Recently NSD2 was shown to regulate adipose tissue development in mice by controlling the activity of the master adipogenic transcription factor peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPARγ).27 Interestingly, in this work mice overexpressing the mutant histone protein H3.3K36M, an NSD2 inhibitor, resisted white adipose tissue expansion in response to a high-fat diet. These findings support the idea that the low BMI observed in the NSD2 cohort may be due to the inability of body fat to expand in response to feeding rather than a consequence of the neonatal feeding difficulties that, although observed in multiple affected individuals, disappear later in life. Furthermore, NSD2 has been shown to play a key role in promoting adipogenesis and myogenesis in precursor cells, as well as thermogenesis in brown adipose tissue and insulin sensitivity in white adipose tissue.27 In pancreatic β-cell lines in vitro NSD2 has also been shown to promote proliferation and to regulate insulin secretion.28 However, since diabetes has not been reported as a recurrent feature neither in our cohort nor in patients with WHS we assume that in humans, glycemic control may be maintained despite impaired NSD2 function.

Likewise, some other known or supposed functions of NSD2 did not result in a recurrent phenotype in our cohort. NSD2 has been suggested to contribute to the immune defects typical of WHS by regulating the hematopoietic process at multiple stages as well as B-29 and T-cell30 differentiation. Nevertheless, only a minority of the patients in this series presented with recurrent infections. Also, while heterozygous Nsd2 deficient mice present with heart defects25 and de novo variants in NSD2 were shown to associate with congenital heart malformations,31 cardiac anomalies were present only in a minority of the individuals in this series, and, with the exception of individual 16-I, were of minor clinical importance. The low prevalence of epilepsy in this cohort is compatible with the assumption that other genes such as LETM1 are responsible for seizures in WHS.32,33

While heterozygotes for missense variants were on average significantly taller, the overall clinical severity correlated only loosely with the measured alteration in NSD2 enzymatic function. Furthermore, for the Cys869Tyr (patient 1-I) variant, which can be categorized as likely pathogenic based on the current ACMG/AMP recommendations,19 we did not detect significant loss of methylation activity in our in vitro assays. These data suggest that in addition to H3K36 dimethylation, other functions of NSD2 such as its genomic localization, and likely other potential genetic differences among the patients, contribute to the pathogenesis of the complex phenotypes described here. Moreover, as the missense variants that we tested did not display any obvious stability issue upon overexpression, dominant negative effects cannot be excluded. Finally, second hits or blending phenotypes with additional variants in other (known or unknown) genes associated with the clinical phenotypes described in this study could contribute to the observed clinical variability.

Patients 11-I and 15-I carried the same protein-elongating p.Pro1343Glnfs*49 variant. Although this variant occurs too distally in the messenger RNA (mRNA) sequence to induce nonsense-mediated decay, its pathogenicity is supported by the fact that this variant, together with the previously described p.Glu1344Lysfs*49 variant,18 all occurred de novo in similarly affected individuals. Although some of the patients in this series carried additional rare variants, none of these are likely pathogenic. Individual 1-I carries a 441-kb heterozygous interstitial microduplication in 22q11.2 (hg19 (chr22:22,817,344–23,258,369) that does not contain any disease-associated genes and was inherited from his healthy father. Individual 5-I carried the recurrent 312-kb interstitial duplication at 15q11.2 (hg19: 22,770,421–23,082,328) that was inherited from her healthy mother. In a large study on the effect of copy-number variants on cognition, 136 control individuals carrying the 15q11.2 duplication performed to a similar level as population controls on all tests of cognitive function.34 In family 7, where both mildly affected siblings (individuals 7-I and 7-II) inherited the NSD2 variant from their similarly affected mother, we additionally found that individual 7-I carries a paternally inherited 783-kb deletion at 9p13.3 (hg19: 35,487,232-36,270,255) as well as the maternally inherited GABBR2 c.1656_1657delTT, p.Cys553Hisfs*96 variant. Her father had learning disability and depression. No overlapping deletion was present in the DECIPHER database but, based on the gene content and on the family history, a modulatory role of the 9p13.3 deletion on her phenotype cannot be excluded. Except for one truncating variant described in a large sequencing study on patients with neurodevelopmental delay,35 all GABBR2 pathogenic variants described until now in this gene are missense (source: HGMD Professional, release 2020.2, see Web Resources). This, together with the fact that her similarly affected brother (individual 7-II) did not carry the p.Cys553Hisfs*96 GABBR2 variant, speaks against a determining role on the phenotype. Individual 10-I carries a 38-kb partial HUWE1 duplication in Xp11.2, which overlaps with a recurrent polymorphic copy-number variant that does not affect the expression of HUWE1 and thus should have no effect on cognition.36

Our study leaves unanswered questions for future research, such as the clarification of the full molecular mechanisms. This may reveal potential targets for therapeutic interventions relevant not only to patients with NSD2 deficiency, but also potentially even to patients with obesity in general.

In conclusion, our data support the concept that NSD2 loss of function is associated with a distinct phenotype that only partially overlaps with WHS and constitutes a differential diagnosis to Silver–Russell and similar syndromes. This phenotype is in line with the distinct features described in the first patient with a small deletion encompassing NSD2 by Rauch et al.8 This patient now at age 26 years is 172 cm tall (-0.55 SDS), weighs 45–50 kg (ca. -2.5 SDS), and has a “small head.” Despite his normal eating behavior, all attempts to gain weight have been unsuccessful. He has an IQ in the lower-normal range, a calm and content personality, and lives with his parents. As a reflection of the distinct facial gestalt and the greatly different disease severity, especially concerning ID, of NSD2 deficiency and contiguous gene deletions leading to WHS, which may also be important for families’ and physicians' perception of the patients’ prognosis, the NSD2-related disorder may be named Rauch–Steindl syndrome after the delineators of this phenotype.8

Web Resources

DECIPHER: https://decipher.sanger.ac.uk

DSM-5 severity levels for intellectual disability: https://dsm.psychiatryonline.org/doi/full/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.dsm01

Face2Gene: https://www.face2gene.com/

GeneMatcher: https://genematcher.org

gnomAD: https://gnomad.broadinstitute.org/

Growth curves of the Swiss society of pediatrics: https://www.kispi.uzh.ch/de/zuweiser/broschueren/Seiten/document.axd?id=56c0bb56-1793-48f3-968e-238915f47bbd9

HGMD Professional: http://www.hgmd.cf.ac.uk/ac/index.php

OMIM: http://www.omim.org/

RasMol: http://www.openrasmol.org/

Smart: http://smart.embl-heidelberg.de/

SwissModel: https://swissmodel.expasy.org/

Uniprot databank entry for NSD2: https://www.uniprot.org/; Entry O96028

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

The project was supported in part by the Swiss National Science Foundation grant 320030_179547 to A.R., by RO1 grant R35GM139569 from the NIH to O.G., by grants from the Dutch Organization for Health Research and Development (ZON-MW grants 917–86–319 and 912–12–109 to B.B.A.d.V.) and by grants from the Estonian Research Council (grants PUT355 and PRG471 to K.Õ.). D.S. was supported by a grant from Stanford Maternal and Child Health Research Institute. A.R. and H.S. were supported by the UZH Clinical Research Priority Program Praeclare. The Broad Center for Mendelian Genomics (UM1 HG008900) is funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute with supplemental funding provided by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute under the Trans-Omics for Precision Medicine (TOPMed) program and the National Eye Institute. C.M.A.R.-A., B.B.A.d.V., D.L., R.P., L.S.B., and M.R.W. are members of the European Reference Network on Rare Congenital Malformations and Rare Intellectual Disability ERN-ITHACA (EU Framework Partnership Agreement ID: 3HP-HP-FPA ERN-01-2016/739516).

Author contributions

Conceptualization: K.S., O.G., A.R. Formal analysis: P.Z., D.S., H.S. Funding acquisition: A.R., H.S., O.G., B.B.A.d.V. Investigation: P.Z., K.S., D.S., H.S., P.J., A.B., M.L.M., C.M.A.R.-A., MS, M.A., T.A.-B., I.M., N.B., V.B., G.D., B.B.A.d.V., S.G., D.L., A.L., J.M., K.Õ., G.P., R.P., K.R., L.S.B., V.T., A.V., L.F., P.G.W., M.R.W., M.W., M.Z. Project administration: P.Z., K.S., A.R., O.G. Supervision: A.R., O.G. Visualization: P.Z., D.S., H.S., P.G. Writing—original draft: P.Z. Writing—review & editing: K.S., D.S., A.R., H.S., O.G.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by University of Zurich.

Data availability

All materials, data sets, and protocols presented in this work are available upon request to the corresponding authors. NSD2 variants have been deposited in the DECIPHER database (see Web Resources) under the following IDs: 422873, 422875, 422876, 422877, 422878, 422879, 422880, 422881, 422882, 422883, 422885, 422886, 422887, 422888, 422889, 422890, 422891, 422892.

Competing interests

O.G. is a co-founder and member of the Board of Directors of EpiCypher, Inc. The other authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics declaration

This study was performed as part of a research study approved by the ethics commission of the Canton of Zurich (PB_2016-02520). Written informed consent for genetic testing and publication of genetic and clinical data, and photos was obtained from each individual, their parents, or their legal guardian. Genetic testing in collaborating centers was performed either in the setting of routine diagnostic without the requirement for institutional review board (IRB) approval or within research settings, under the following approvals: p.3-I: Comité de Protection des Personnes (Dijon), #DC2011-1332; p.4-I: Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board, #19-0751; p.5-I: Western Institutional Review Board, #20120789; p.15-I: #287/M-15, The Ethics Committee of University of Tartu.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Paolo Zanoni, Katharina Steindl, Deepanwita Sengupta.

These authors contributed equally: Or Gozani, Anita Rauch.

Contributor Information

Paolo Zanoni, Email: paolo.zanoni@uzh.ch.

Anita Rauch, Email: anita.rauch@medgen.uzh.ch.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41436-021-01158-1.

References

- 1.Wolf U, Reinwein H, Porsch R, Schröter R, Baitsch H. [Deficiency on the short arms of a chromosome no. 4] Humangenetik. 1965;1:397–413. doi: 10.1007/BF00395654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hirschhorn K, Cooper HL, Firschein IL. Deletion of short arms of chromosome 4-5 in a child with defects of midline fusion. Humangenetik. 1965;1:479–482. doi: 10.1007/BF00279124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zollino M, et al. On the nosology and pathogenesis of Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome: genotype-phenotype correlation analysis of 80 patients and literature review. Am. J. Med. Genet. C Semin. Med. Genet. 2008;148:257–269. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Donnai D. Editorial comment: Pitt–Rogers–Danks syndrome and Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1996;66:101–103. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19961202)66:1<101::AID-AJMG27>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kant SG, et al. Pitt–Rogers–Danks syndrome and Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome are caused by a deletion in the same region on chromosome 4p16.3. J. Med. Genet. 1997;34:569–572. doi: 10.1136/jmg.34.7.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Battaglia A, Carey JC. Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome and Pitt–Rogers–Danks syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1998;75:541. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(19980217)75:5<541::AID-AJMG18>3.0.CO;2-K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright TJ, et al. A transcript map of the newly defined 165 kb Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome critical region. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1997;6:317–324. doi: 10.1093/hmg/6.2.317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rauch A, et al. First known microdeletion within the Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome critical region refines genotype–phenotype correlation. Am. J. Med. Genet. 2001;99:338–342. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Okamoto N, Ohmachi K, Shimada S, Shimojima K, Yamamoto T. 109kb deletion of chromosome 4p16.3 in a patient with mild phenotype of Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2013;161:1465–1469. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.35910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bernardini L, et al. Small 4p16.3 deletions: three additional patients and review of the literature. Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2018;176:2501–2508. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.40512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuo AJ, et al. NSD2 links dimethylation of histone H3 at lysine 36 to oncogenic programming. Mol Cell. 2011;44:609–620. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gabriele M, Lopez Tobon A, D’Agostino G, Testa G. The chromatin basis of neurodevelopmental disorders: rethinking dysfunction along the molecular and temporal axes. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry. 2018;84:306–327. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2017.12.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yang P, et al. Histone methyltransferase NSD2/MMSET mediates constitutive NF-κB signaling for cancer cell proliferation, survival, and tumor growth via a feed-forward loop. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2012;32:3121–3131. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00204-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lozier ER, et al. De novo nonsense mutation in WHSC1 (NSD2) in patient with intellectual disability and dysmorphic features. J. Hum. Genet. 2018;63:919–922. doi: 10.1038/s10038-018-0464-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boczek NJ, et al. Developmental delay and failure to thrive associated with a loss-of-function variant in WHSC1 (NSD2) Am. J. Med. Genet. A. 2018;176:2798–2802. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.40498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Derar N, et al. De novo truncating variants in WHSC1 recapitulate the Wolf–Hirschhorn (4p16.3 microdeletion) syndrome phenotype. Genet. Med. 2019;21:185–188. doi: 10.1038/s41436-018-0014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barrie ES, et al. De novo loss-of-function variants in NSD2 (WHSC1) associate with a subset of Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome. Mol. Case Stud. 2019;5:a004044. doi: 10.1101/mcs.a004044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jiang Y, et al. De novo truncating variant in NSD2gene leading to atypical Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome phenotype. BMC Med. Genet. 2019;20:134. doi: 10.1186/s12881-019-0863-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Richards S, et al. Standards and guidelines for the interpretation of sequence variants: A joint consensus recommendation of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics and the Association for Molecular Pathology. Genet. Med. 2015;17:405–424. doi: 10.1038/gim.2015.30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mazur PK, et al. SMYD3 links lysine methylation of MAP3K2 to Ras-driven cancer. Nature. 2014;510:283–287. doi: 10.1038/nature13320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Husmann D, Gozani O. Histone lysine methyltransferases in biology and disease. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2019;26:880–889. doi: 10.1038/s41594-019-0298-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sankaran SM, Wilkinson AW, Elias JE, Gozani O. A PWWP Domain of histone-lysine N-methyltransferase NSD2 binds to dimethylated lys-36 of histone H3 and regulates NSD2 function at chromatin. J. Biol. Chem. 2016;291:8465–8474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.720748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Oyer JA, et al. Point mutation E1099K in MMSET/NSD2 enhances its methyltranferase activity and leads to altered global chromatin methylation in lymphoid malignancies. Leukemia. 2014;28:198–201. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shannon NL, Maltby EL, Rigby AS, Quarrell OWJ. An epidemiological study of Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome: life expectancy and cause of mortality. J. Med. Genet. 2001;38:674–679. doi: 10.1136/jmg.38.10.674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nimura K, et al. A histone H3 lysine 36 trimethyltransferase links Nkx2-5 to Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome. Nature. 2009;460:287–291. doi: 10.1038/nature08086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kichaev G, et al. Leveraging polygenic functional enrichment to improve GWAS power. Am J. Hum. Genet. 2019;104:65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhuang L, et al. Depletion of Nsd2-mediated histone H3K36 methylation impairs adipose tissue development and function. Nat. Commun. 2018;9:1796. doi: 10.1038/s41467-018-04127-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shi S, Zhao L, Zheng L. NSD2 is downregulated in T2DM and promotes ß cell proliferation and insulin secretion through the transcriptionally regulation of PDX1. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018;18:3513–3520. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.9338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Campos-Sanchez E, et al. Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome candidate 1 is necessary for correct hematopoietic and B cell development. Cell Rep. 2017;19:1586–1601. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.04.069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Long, X. et al. Histone methyltransferase Nsd2 is required for follicular helper T cell differentiation. J. Exp. Med. 10.1084/jem.20190832 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Jin SC, et al. Contribution of rare inherited and de novo variants in 2,871 congenital heart disease probands. Nat Genet. 2017;49:1593–1601. doi: 10.1038/ng.3970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hart L, Rauch A, Carr AM, Vermeesch JR, O’Driscoll M. LETM1 haploinsufficiency causes mitochondrial defects in cells from humans with Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome: Implications for dissecting the underlying pathomechanisms in this condition. Dis. Model. Mech. 2014;7:535–545. doi: 10.1242/dmm.014464. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ho KS, et al. Chromosomal microarray testing identifies a 4p terminal region associated with seizures in Wolf–Hirschhorn syndrome. J. Med. Genet. 2016;53:256–263. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2015-103626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stefansson H, et al. CNVs conferring risk of autism or schizophrenia affect cognition in controls. Nature. 2014;505:361–366. doi: 10.1038/nature12818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kosmicki JA, et al. Refining the role of de novo protein-truncating variants in neurodevelopmental disorders by using population reference samples. Nat. Genet. 2017;49:504–510. doi: 10.1038/ng.3789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Froyen G, et al. Copy-number gains of HUWE1 due to replication- and recombination-based rearrangements. Am J. Hum. Genet. 2012;91:252–264. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2012.06.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All materials, data sets, and protocols presented in this work are available upon request to the corresponding authors. NSD2 variants have been deposited in the DECIPHER database (see Web Resources) under the following IDs: 422873, 422875, 422876, 422877, 422878, 422879, 422880, 422881, 422882, 422883, 422885, 422886, 422887, 422888, 422889, 422890, 422891, 422892.