Abstract

The disturbance of strictly regulated self-regeneration in mammalian intestinal epithelium is associated with various intestinal disorders, particularly inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs). TNFα, which plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of IBDs, has been reported to inhibit production of ketone bodies such as β-hydroxybutyrate (βHB). However, the role of ketogenesis in the TNFα-mediated pathological process is not entirely known. Here, we showed the regulation and role of HMGCS2, the rate-limiting enzyme of ketogenesis, in TNFα-induced apoptotic and inflammatory responses in intestinal epithelial cells. Treatment with TNFα dose-dependently decreased protein and mRNA expression of HMGCS2 and its product, βHB production in human colon cancer cell lines HT29 and Caco2 cells and mouse small intestinal organoids. Moreover, the repressed level of HMGCS2 protein was found in intestinal epithelium of IBD patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis as compared with normal tissues. Furthermore, knockdown of HMGCS2 enhanced and in contrast, HMGCS2 overexpression attenuated, the TNFα-induced apoptosis and expression of pro-inflammatory chemokines (CXCL1–3) in HT29, Caco2 cells and DLD1 cells, respectively. Treatment with βHB or rosiglitazone, an agonist of PPARγ, which increases ketogenesis, attenuated TNFα-induced apoptosis in the intestinal epithelial cells. Finally, HMGCS2 knockdown enhanced TNFα-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation. In addition, hydrogen peroxide, the major ROS contributing to intestine injury, decreased HMGCS2 expression and βHB production in the intestinal cells and mouse organoids. Our findings demonstrate that increased ketogenesis attenuates TNFα-induced apoptosis and inflammation in intestinal cells, suggesting a protective role for ketogenesis in TNFα-induced intestinal pathologies.

Keywords: HMGCS2, ketogenesis, TNFα, intestinal cells, Crohn’s disease, inflammatory bowel disease, colorectal cancer

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

The mammalian intestinal epithelium undergoes a highly regimented and tightly controlled process of continuous self-renewal, which includes balanced proliferation, apoptosis and differentiation [1]. An imbalance of this orderly process is associated with various intestinal pathologies such as colorectal cancer and inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) [2, 3].

Patients with IBD, a chronic inflammatory disorder characterized by periods of remission and relapse [4], suffer from a number of debilitating symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, weight loss and rectal bleeding [5]. These diseases include primarily Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis, which differ in several features including the location and the nature of the inflammation [5, 6]. Recent studies have shown that IBDs are a result of a combination of multi-factorial etiologies such as genetic, microbial, and environmental factors [4, 7]. Although the exact pathogenesis for IBDs is still not entirely known, IBDs are characterized by a deregulated production of pro-inflammatory mediators including tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) [7, 8].

TNFα is associated with cellular processes such as cell proliferation, survival and death and is a key regulator of the inflammatory response in a variety of human diseases, including psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis, and IBDs [8–10]. TNFα has an important role in maintaining the intestinal integrity and in the pathogenesis of intestinal inflammation [8, 10]. Increased systemic and intestinal tissue levels of TNFα in IBD patients and IBD risk alleles, associated with TNF signaling components that have been identified by genome wide association studies, suggest an essential function for TNFα in the pathogenesis of IBD [11–13]. In addition, anti-TNFα therapy is considered as a beneficial therapeutic option for some IBD patients [8, 10, 11, 14].

Ketogenesis represents a series of metabolic reactions that produce ketone bodies, which provide a substitute source of energy in the body during fasting and starvation [15, 16]. This process primarily occurs in the mitochondria of liver cells but is also carried out in the kidney, brain and colon to a lesser extent [16, 17]. Ketogenesis is regulated by transcriptional and posttranslational modifications of some key ketogenic enzymes [15, 17]. Mitochondrial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 2 (HMGCS2) is the rate-limiting enzyme of ketogenesis, which generates ketone bodies such as β-hydroxybutyrate (βHB) [17, 18]. We and others have shown that the expression of HMGCS2 is regulated by PPARs, c-Myc or the Wnt/β-catenin pathway [19–21]. Cytokines (e.g., TNFα) have been reported to inhibit ketone body production in animal models and isolated rat hepatocytes [22–24]. However, detailed mechanisms and the potential role of ketogenic enzymes, especially HMGCS2, in this process are not known.

In our current study, we investigated the regulation of HMGCS2 expression and βHB concentration by TNFα in intestinal epithelial cells and mouse intestinal organoids and the protein level of HMGCS2 in IBD patient tissues. We also determined the effect of HMGCS2 and βHB on TNFα-induced responses in the intestinal epithelial cells. Furthermore, we showed the effect of HMGCS2 on TNFα-induced reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation and the influence of ROS on ketogenesis regulation in intestinal cells. Our findings suggest a novel protective role for ketogenesis in TNFα-induced apoptosis and inflammatory responses in intestinal epithelial cells.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell culture, transfection and treatment.

Human colorectal cancer epithelial cell lines, HT29, Caco2 and DLD1, were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA). HT29 and Caco2 cells were cultured in McCoy’s 5A medium supplemented with 10% FBS and MEM with 15% FBS, 1% sodium pyruvate and 1% nonessential amino acids, respectively. DLD1 cells were grown in RPMI1640 with 10% FBS. The cells were maintained at 37°C in a humidified 5% CO2 incubator. Transfection with ON-TARGET plus SMARTpool siRNAs (Dharmacon, Lafayette, CO) for non-targeting control (NTC, catalog #, D-001810–10), and HMGCS2 (catalog #, L-010179–00) was performed using Lipofectamine RNAi MAX (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. To establish stable cell lines expressing HMGCS2, pCMV6-Entry-HMGCS2 cDNA clone (RC208128, OriGene Technologies, Rockville, MD) or pCMV6-Entry [empty vector (EV), PS100001, OriGene] were transfected into DLD1 or HT29 cells using Lipofectamine™ 2000 and stable transfectants were obtained following G418 selection. Recombinant human TNFα and rosiglitazone (RGZ; a PPARγ agonist) were purchased from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ) and Tocris Bioscience (Bristol, UK), respectively. βHB, 2ʹ,7ʹ-dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) were obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO).

Western blot analysis.

Western blotting was carried out as described previously [25]. The antibodies for HMGCS2 and β-actin were purchased from Abcam (Cambridge, MA) and Sigma-Aldrich, respectively. The antibodies for cleaved PARP (cPARP) and cleaved caspase-3 (cCaps-3) were acquired from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). The anti-PPARγ antibody was obtained from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Densitometric analysis from three different experiments for HMGCS2 expression was performed using ImageJ software.

RNA isolation and real time reverse transcription-PCR (RT-PCR) analysis.

RT-PCR reactions were performed using cDNA synthesized from total RNA isolated using RNeasy kits (Qiagen, Valencia, CA), High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems, Austin, TX), a TaqMan Gene Expression Master Mix, and TaqMan probes for human HMGCS2 (assay ID, Hs00985427_m1), CXCL1 (Hs00236937_m1), CXCL2 (Hs00601975_m1), CXCL3 (Hs00171061_m1) and GAPDH (Hs99999905_m1) or for mouse Hmgcs2 (Mm00550050_m1), Cxcl1 (Mm04207460_m1), Cxcl2 (Mm00436450_m1), Cxcl3 (Mm01701838_m1) and Gapdh (Mm99999915_g1) according to instruction provided by the manufacturer (Applied Biosystems).

βHB assay.

Intracellular βHB content was measured using a Beta-Hydroxybutyrate Assay Kit (MAK041; Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instruction. Each plotted value was normalized to total amount of protein used from cell or organoid cultures.

Intestinal organoid culture.

Isolation and culture of mouse small intestinal organoids, collected from the small intestinal mucosa, were carried out as described previously [21]. Briefly, isolated crypts were mixed with Matrigel (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) and cultured in basic culture medium (ENR) containing advanced DMEM/F12 medium with 50 ng/ml EGF (PeproTech), 100 ng/ml noggin (PeproTech), and 100 ng/ml R-spondin (PeproTech). The organoids were treated with TNFα or H2O2 for 48 h and total protein and RNA were extracted. All animal procedures were conducted in accordance with National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Immunohistochemistry.

Human intestine biopsy specimens were obtained from patients at the University of Kentucky undergoing diagnostic or surveillance colonoscopy for known or suspected Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis. For comparison, biopsy specimens were obtained from healthy patients undergoing routine colon cancer surveillance. Collection of all patient materials for this study was approved by the University of Kentucky Institutional Review Board (#48678) and their information is represented in Supplementary Table 1. The slides of paraffin-embedded intestine tissue blocks from ulcerative colitis (n=20) or Crohn’s disease (n=7, small intestine; n=5, colon) patients or patients without intestinal inflammation (n=6, small intestine; n=5, colon) were used and immunostaining was performed with an antibody against HMGCS2 (Abcam) by the University of Kentucky Department of Pathology and the Markey Cancer Center Biospecimen Procurement and Translational Pathology Shared Resource Facility as described previously [25, 26]. Assessment of inflamed diseases from patients with ulcerative colitis or Crohn’s disease and scoring of the stained slides was performed blindly.

DNA fragmentation ELISA assay.

Cells were plated in 24-well plates for 24 h and then treated with TNFα for an additional 48 h. Apoptosis was measured by DNA fragmentation using the Cell Death Detection ELISAplus (Roche, Indianapolis, IN) as described previously [26].

Measurement of secreted CXCL1 by ELISA.

DLD1 cells stably transfected with empty control vector or vector expressing HMGCS2 were seeded into 6-well plates 24 h before treatment. The cells were then treated with TNFα for 48 h and conditioned media was collected and centrifuged to remove any debris. Secreted CXCL1 was measured using Human CXCL1/GRO alpha Quantikine ELISA Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

PPARγ transcription factor assay.

The DNA binding activity of PPARγ was assessed using a PPARγ Transcription Factor Assay Kit (Abcam), as described previously [21]. Briefly, the nuclear proteins were incubated in wells immobilized with specific PPAR-binding element (PPRE) sequences with the primary anti-PPARγ antibody, HRP-conjugated secondary antibody subsequently, and the absorbance was measured at 450 nm to determine the transcriptional activity of PPARγ.

Measurement of ROS generation.

The assessment of ROS production was performed using the fluorescent dye, DCFH-DA, by confocal microscopy and flow cytometry, respectively. Briefly, HT29 cells transfected with siRNAs were incubated with TNFα for 48 h. Then, the cells were washed with PBS and incubated with 10 μM DCFH-DA at 37°C for 30 min. The ROS generation was checked by DCF fluorescence, and the fluorescent images were collected by a single rapid scan using identical parameters for all samples. To measure the ROS concentration by flow cytometry, cells were loaded with 10 μM DCFH-DA for 30 min, trypsinized, and washed with cold PBS two times followed by fluorescence-activated cell sorting analysis using the Becton-Dickinson FACSort flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, NJ, USA).

Statistical analysis.

Bar graphs were generated to represent mean ± SD for each cell culture condition. Relative levels of protein, mRNA, βHB concentration, apoptosis, CXCL1 secretion, PPARγ transcriptional activity and ROS generation were calculated based on mean levels in control group (NTC or EV) or mean of control cell culture conditions. Fold-change of western blot densitometry relative to control were calculated for each replicate. Statistical analyses for comparison across groups or dose levels were performed using two-sample t-test or analysis of variance with log transformation on IHC scores in human samples. Multiple testing for pairwise comparisons was adjusted using the Holm’s method. p-values< 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4. All experiments were performed in triplicate.

RESULTS

TNFα inhibits ketogenesis through suppression of HMGCS2 expression in intestinal cells.

Previous studies have shown that cytokines (e.g., TNFα) inhibit ketone body production in several animal models and isolated rat hepatocytes [22–24]. To determine how ketogenesis is regulated by TNFα, the expression of HMGCS2, a rate-limiting ketogenic enzyme, was determined in human colon epithelial cancer cell lines, HT29 and Caco2 cells. As shown in Fig. 1A, treatment of HT29 (left) and Caco2 (right) cells with TNFα (50 and 100 ng/ml) significantly decreased HMGCS2 protein expression in both cell lines. Consistent with the reduced protein expression, TNFα suppressed the expression of HMGCS2 mRNA in these cells as detected by real time RT-PCR (Fig. 1B). To further determine if TNFα-mediated HMGCS2 reduction correlates with inhibition of ketogenesis, we measured the concentration of βHB, the most abundant ketone body. In agreement with the decreased protein and mRNA expression of HMGCS2, TNFα treatment (50 and 100 ng/ml) significantly decreased intracellular βHB content by 23% and 35% and 24% and 48% in HT29 and Caco2 cells, respectively, compared with the control group (Fig. 1C). To demonstrate the effect of TNFα on HMGCS2 expression in normal intestinal cells, mouse small intestinal organoids cultured in Matrigel were incubated with TNFα for 48 h. TNFα (20 and 50 ng/ml) treatment dose-dependently suppressed the expression of HMGCS2 protein and mRNA and βHB production compared with vehicle treatment (Fig. 1D). Together, our findings demonstrate that TNFα inhibits ketogenesis through suppression of HMGCS2 expression in intestinal epithelial cells.

Figure 1. TNFα reduces HMGCS2 expression and βHB concentration in intestinal cells and mouse intestinal organoids.

HT29 and Caco2 cells treated with TNFα were incubated for 24 h. (A) Western blot analysis was performed using the indicated antibodies. Signals of HMGCS2 from three separate western blots were quantitated densitometrically and expressed as fold change with respect to β-actin (n =3, data represent mean ± SD; *p < 0.05 vs 0 ng/ml TNFα). (B) The level of HMGCS2 mRNA was assessed by real-time RT-PCR (n= 3, data represent mean ± SD; *p < 0.05 vs 0 ng/ml TNFα). (C) Cell lysates for HT29 and Caco2 cells treated with TNFα for 24 h were used for measurement of βHB content using a βHB assay kit (n=3, data represent mean ± SD; *p < 0.05 vs 0 ng/ml TNFα). (D) Mouse small intestinal organoids were treated with TNFα for 48 h; HMGCS2 mRNA and protein levels and βHB content were determined as described above.

The expression of HMGCS2 protein is repressed in inflamed tissues from patients with IBD.

Decreased HMGCS2 expression has been described in inflamed Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis patient tissues as determined by RNA-seq and proteomics analyses, respectively [27, 28]. To assess whether HMGCS2 protein expression is reduced specifically in the inflamed intestinal epithelium in IBD, we analyzed intestinal tissues from patients with Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Each tissue sample was assigned an immunoreactivity score ranging from 0–9. Representative samples for HMGCS2 are shown (Fig. 2A) along with the analysis (Fig. 2B). While normal intestinal epithelium demonstrated strong staining of HMGCS2, small intestinal mucosa from Crohn’s disease and colonic mucosa from ulcerative colitis patients exhibited negative or relatively mild staining. A decrease in HMGCS2 levels, although not statistically significant, was observed in the colonic mucosa of patients with Crohn’s disease (Fig. 2B, middle panel) compared with normal control. These results demonstrate that HMGCS2 protein expression is dramatically suppressed in intestinal epithelial cells from Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis patient tissues as compared with control (i.e., non-IBD), indicating a possible role of HMGCS2 in the inflammatory process.

Figure 2. Decreased protein expression of HMGCS2 is associated with human inflamed IBD tissues.

(A) Representative images are shown for H&E or HMGCS2 staining in small intestine (left panel) and colon (right panel) from patients with (Crohn’s disease; ulcerative colitis) or without (normal) intestinal inflammation. (B) Tissue sections for human small intestinal normal (n = 6) and Crohn’s disease (n = 7) (left), and colonic normal (n = 5) and Crohn’s disease (n = 5) (middle) and normal colon (n = 5) and ulcerative colitis (n = 20) (right) were stained with anti-HMGCS2 antibody. Immunoreactivity scores were determined by multiplication of the values for staining intensity (0, no staining; 1, weak staining; 2, moderate staining; 3, strong staining) and for percentage of positive staining cells (0, no positive; 1, 0%−10% positive; 2, 11%−50% positive; 3, 51%−100% positive); *p < 0.05 vs normal tissue.

HMGCS2 attenuates TNFα-induced apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells.

TNFα, a key cytokine that triggers apoptosis of intestinal epithelial cells, plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of IBD [8, 10]. To elucidate the role of HMGCS2 in TNFα-induced apoptosis, HT29 and Caco2 cells, transiently transfected with NTC siRNA or siRNA targeting HMGCS2, were treated with TNFα over a 48 h time period and apoptosis was analyzed by measuring the intracellular apoptotic markers (i.e., cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase-3). As shown in Figs. 3A&B, treatment with TNFα induced apoptosis as noted by the increased PARP and caspase-3 cleavage; these increases were enhanced by HMGCS2 knockdown (Fig. 3A) and attenuated by HMGCS2 overexpression (Fig. 3B). We noted that exogenous HMGCS2 was increased by TNFα in DLD1 cells (Fig. 3B), which may be due to the known characteristics of the plasmid carrying the human cytomegalovirus (CMV) promoter and enhancers that respond to TNFα [29] (Fig. 3B). Similarly, overexpression of HMGCS2 attenuated the apoptotic response to TNFα in stable HMGCS2 HT29 clones showing reduced endogenous but increased exogenous HMGCS2 expression by TNFα (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Figure 3. HMGCS2 attenuates TNFα-induced apoptosis in human intestinal epithelial cells.

(A) Western blot analysis for cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase-3 in HT29 and Caco2 cells transfected with non-targeting control (NTC) or HMGCS2 siRNA after TNFα treatment for 48 h. (B) Western blotting for the apoptotic markers in stable transfected DLD1 cells with empty vector (EV) or HMGCS2 expression vector (HMGCS2) after TNFα treatment for 48 h. (C) Assessment of TNFα-induced apoptosis in HT29 and DLD1 cells using Cell Death Detection ELISAplus; *p < 0.05 vs untreated NTC or EV, †p < 0.05 vs NTC or EV plus TNFα, ‡p < 0.05 vs untreated cells with HMGCS2 knockdown or overexpression.

To further determine the role of HMGCS2 in TNFα-induced apoptosis, we assessed the effect of HMGCS2 on TNFα-induced apoptosis using a Cell Death Detection ELISAplus. As shown in Fig. 3C, TNFα-induced apoptosis was noted by the increased DNA fragmentation in HT29 and DLD1 cells. Knockdown of HMGCS2 increased, while overexpression of HMGCS2 attenuated, TNFα-induced DNA fragmentation compared with control cells. Collectively, these results suggest that HMGCS2 plays a protective role in TNFα-induced apoptosis.

HMGCS2 inhibits TNFα-induced pro-inflammatory chemokine expression in intestinal cells.

TNFα stimulates the expression and release of several pro-inflammatory chemokines, such as CXCL1–3, in human epithelial cells [30, 31]. In addition, deregulated production of these molecules is implicated in the pathogenesis of IBD [31, 32]. We first investigated TNFα-induced Ccxl1–3 expression in mouse small intestinal organoids. As shown in Fig. 4A, treatment of the organoid cultures with TNFα (20 and 50 ng/ml) dramatically increased Cxcl1–3 mRNA expression (45- and 54-fold increase for Cxcl1; 27- and 57-fold increase for Cxcl2; and 1.6 and 2.5-fold for Cxcl3 compared with vehicle treated controls). Next, we determined the effects of HMGCS2 on TNFα-induced expression of pro-inflammatory chemokines in human colorectal cancer epithelial cell lines. TNFα (50 and 100 ng/ml) treatment reduced HMGCS2 mRNA expression (Supplementary Fig. 2A) and enhanced mRNA expression of CXCL1–3 in HT29, and DLD1 cells. Moreover, this increase was significantly enhanced by HMGCS2 siRNA transfection in HT29 (Fig. 4B) and Caco2 cells (Fig. 4C) compared with cells transfected with the NTC siRNA. In contrast, overexpression of HMGCS2 attenuated TNFα-induced CXCL1–3 mRNA expression in DLD1 (Fig. 4D) and HT29 cells (Supplementary Fig. 2B) compared with cells transfected with empty vector. To examine whether HMGCS2 affects CXCL1 protein secretion, DLD1 cells with overexpression of HMGCS2 were treated with TNFα. Consistent with the increased mRNA expression, TNFα (50 and 100 ng/ml) increased CXCL1 secretion, and this increase was attenuated by HMGCS2 overexpression (Fig. 4E). Taken together, these results demonstrate that HMGCS2 alleviates TNFα-induced expression of CXCL1–3 associated with intestinal inflammation.

Figure 4. HMGCS2 alleviates TNFα-induced CXCL1–3 expression in intestinal cells.

(A) Expression of Cxcl1–3 mRNA was measured in mouse small intestinal organoids treated with TNFα for 48 h by real-time RT-PCR (n=3, data represent mean ± SD; *p < 0.05 vs 0 ng/ml TNFα). Expression of pro-inflammatory chemokine family (CXCL1–3) mRNA in HT29 (B) and Caco2 (C) cells transfected with NTC or HMGCS2 siRNA after TNFα treatment for 48 h. (D) Expression of the pro-inflammatory chemokine mRNA expression in stable DLD1 cells with empty or HMGCS2 vector after TNFα treatment for 48 h. Expression of CXCL1–3 mRNA was assessed by real-time RT-PCR (n=3, data represents mean ± SD; *p < 0.05 vs untreated NTC or EV, †p < 0.05 vs NTC or EV plus TNFα, ‡p < 0.05 vs untreated HMGCS2). (E) Secretion of CXCL1 in DLD1 cells stably transfected with HMGCS2 or empty vector and treated with TNFα for 48 h (n=3, data represent mean ± SD; *p < 0.05 vs untreated EV, †p < 0.05 vs EV plus TNFα, ‡p < 0.05 vs untreated cells with HMGCS2 overexpression).

βHB attenuates TNFα-induced apoptosis in intestinal cells.

As described above, HMGCS2 is a key enzyme in the synthesis of βHB, which reduces TNFα-induced physio-pathological responses in several neurological models [33–35]. To elucidate the influence of βHB on TNFα-induced apoptosis in intestinal epithelial cells, we determined the level of cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase-3 in HT29, Caco2 and DLD1 cells co-treated with TNFα and βHB for 48 h. As shown in Fig. 5, TNFα-induced apoptosis was observed by the induction of PARP and caspase-3 cleavage; this increase was attenuated by βHB treatment. These results suggest that βHB mediates the role of HMGCS2 in the protection against TNFα-induced apoptosis.

Figure 5. βHB lessens TNFα-induced apoptosis in human intestinal epithelial cells.

Western blotting for cleaved PARP and cleaved caspase-3 in HT29 (left), Caco2 (middle) and DLD1 (right) cells co-treated with TNFα and βHB (10 mM) for 48 h.

Activation of PPARγ as an upstream regulator of HMGCS2 attenuates TNFα- induced apoptosis in human intestinal epithelial cells.

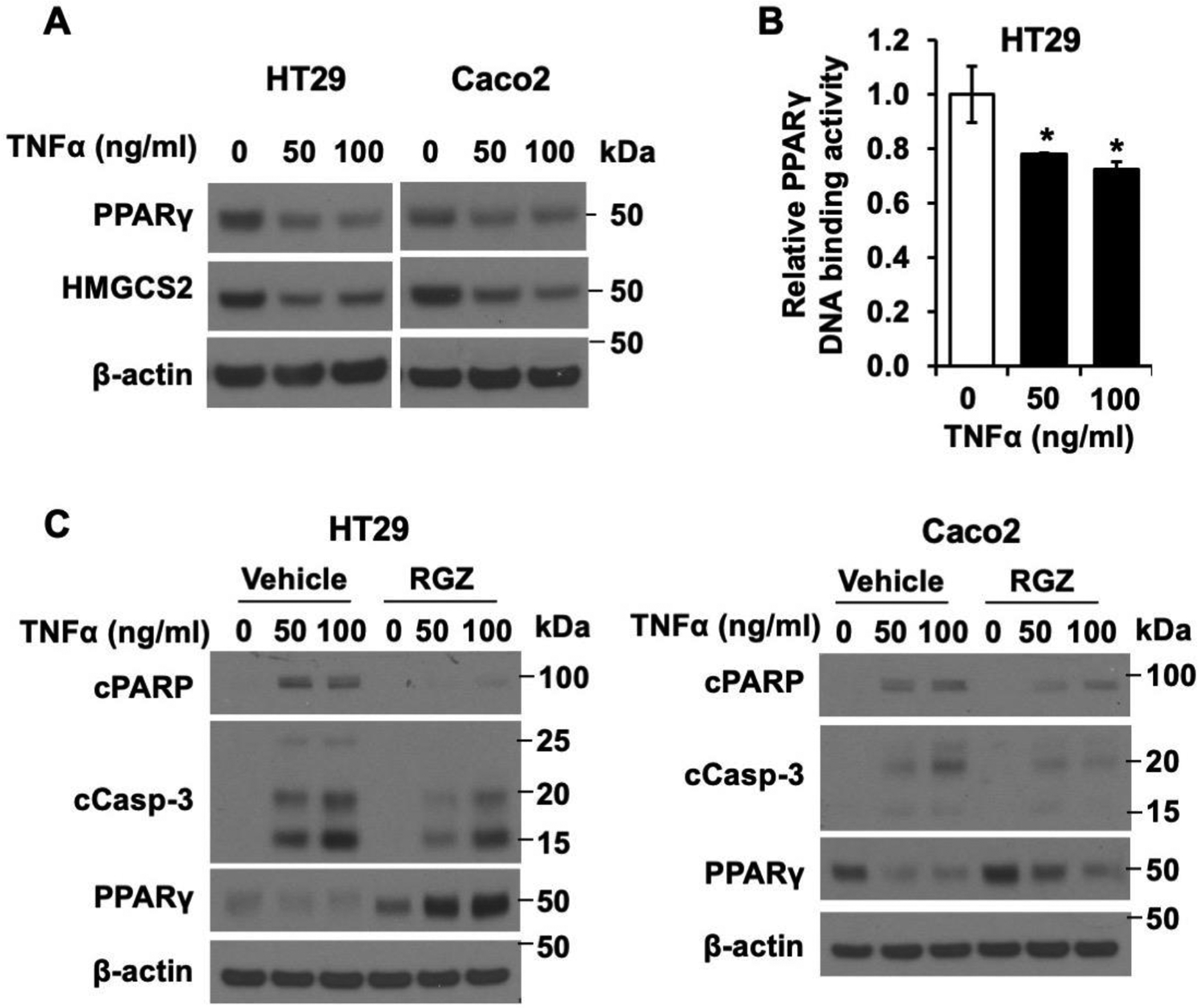

Recent studies from our laboratory and others have shown that PPARγ induces HMGCS2 expression [21, 36]. It has also been reported that PPARγ agonists, including RGZ, protect against TNFα-induced cell damage [37, 38]. Moreover, TNFα is known to repress PPARγ expression in adipocytes [38–40]. To determine whether TNFα regulates PPARγ expression in intestinal cells, we determined the protein levels of PPARγ in HT29 and Caco2 cells treated with TNFα. Treatment of TNFα decreased the protein level of PPARγ (Fig. 6A). In addition, using a PPARγ Transcription Factor Assay Kit, we found a 22% and 28% reduction in the DNA binding activity of PPARγ in HT29 cells treated with TNFα (50 and 100 ng/ml) compared with untreated cells (Fig. 6B). These results demonstrate that TNFα decreases HMGCS2 expression, at least in part, through the inhibition of PPARγ expression and transcriptional activity.

Figure 6. Activation of PPARγ attenuates TNFα-induced apoptosis in human intestinal epithelial cells.

(A) Western blot analysis for PPARγ in HT29 and Caco2 cells treated with TNFα for 48 h. (B) PPARγ DNA-binding activity was determined using HT29 cells treated with 0, 50 or 100 ng/ml TNFα as described in the Materials and Methods (n=3, data represent mean ± SD; *p < 0.05 vs 0 ng/ml TNF). (C) Western blotting for cleaved PARP, cleaved caspase-3 and PPARγ in HT29 (left) and Caco2 (right) cells co-treated with TNFα and RGZ [50 (HT29) or 75 (Caco2) μM] for 48 h.

To next determine the impact of PPARγ on TNFα-induced apoptosis, we determined the cleavage of PARP and caspase-3 in HT29 and Caco2 co-treated with TNFα and RGZ, a highly potent and selective PPARγ agonist [41]. As shown in Fig. 6C, induction of PARP and caspase-3 cleavage was detected in HT29 and Caco2 cells treated with TNFα; this induction was attenuated by RGZ treatment. Altogether, these data demonstrate that TNFα decreases HMGCS2 expression through the inhibition of PPARγ and that the increase of PPARγ/HMGCS2 decreases TNFα-induced apoptosis in intestinal epithelial cells.

HMGCS2 mitigates TNFα-induced ROS production in intestinal cells.

TNFα has been shown to stimulate epithelial cells to produce ROS [42, 43], which we have shown induces intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis [44]. To investigate the effect of HMGCS2 on TNFα-induced ROS generation in intestinal epithelial cells, we determined the level of ROS in HT29 cells transfected with HMGCS2 siRNA followed by treatment with TNFα (Fig. 7A). TNFα treatment increased ROS production in HT29 cells; this increase was enhanced by knockdown of HMGCS2. The effect of HMGCS2 on TNFα-induced ROS production was further confirmed by flow cytometry as shown in Fig. 7B. The increase of TNFα-induced ROS generation was further enhanced by HMGCS2 knockdown (1.9-fold vs 5.1-fold, respectively, compared with untreated cells transfected with NTC siRNA). These findings demonstrated that HMGCS2 protects against TNFα-induced ROS generation in intestinal cells.

Figure 7. HMGCS2 mitigates TNFα-induced ROS production in intestinal epithelial cells.

(A) The DCF fluorescence was visualized by confocal microscopy using NTC or HMGCS2 siRNA transfected HT29 cells treated with TNFα for 48 h. (B) The amount of fluorescence was measured using flow cytometry as described in MATERIALS AND METHODS. The quantification of ROS generation acquired in three independent experiments is represented by the geometric (Geo) mean values of DCF fluorescence (n=3, data represent mean ± SD; *p < 0.05 vs untreated NTC, †p < 0.05 vs NTC plus TNFα, ‡p < 0.05 vs untreated cells with HMGCS2 knockdown).

ROS represses ketogenesis in intestinal cells.

We have shown that an increase in ketogenesis (HMGCS2 overexpression and treatment with βHB) attenuates TNFα-induced ROS production. To determine whether ROS regulates ketogenesis, the expression of HMGCS2 was determined in HT29 and Caco2 cells treated with H2O2, one of the major contributing factors to intestinal injury [45]. H2O2 (200 and 400 μM) repressed the expression of HMGCS2 protein (Fig. 8A) and mRNA (Fig. 8B) and βHB production (Fig. 8C) in these cells. Similarly, H2O2 treatment decreased HMGCS2 protein and mRNA expression levels and βHB concentration in mouse small intestinal organoids (Fig. 8D). Collectively, these data show that H2O2 suppresses ketogenesis in intestinal cells as noted by the decreased HMGCS2 expression and βHB production. Importantly, our results demonstrate a novel cross-talk between ketogenesis and ROS in TNFα-induced inflammatory responses.

Figure 8. H2O2 diminishes HMGCS2 expression and βHB production in intestinal epithelial cells.

(A) Western blot analysis was performed using HT29 and Caco2 cells treated with H2O2 for 24 h. Signals of HMGCS2 from three separate experiments were quantitated densitometrically and expressed as fold change with respect to β-actin (n =3, data represent mean ± SD; *p < 0.05 vs 0 μM H2O2). (B) The level of HMGCS2 mRNA was evaluated by real-time RT-PCR (n= 3, data represent mean ± SD; *p < 0.05 vs 0 μM H2O2). (C) Cell lysates for HT29 and Caco2 cells treated with H2O2 for 24 h were used for measurement of βHB concentration using a βHB assay kit (n=3, data represent mean ± SD; *p < 0.05 vs 0 μM H2O2). (D) Mouse small intestinal organoids were treated with H2O2 for 48 h; HMGCS2 mRNA and protein levels and βHB production were determined as described above. (E). Proposed model of ketogenesis in TNFα-induced apoptosis and inflammation in intestinal cells.

DISCUSSION

The intestinal epithelium closely interacts with the microbiota and immune system to maintain a tight equilibrium and balance between proliferation and programmed cell death. Disruption of this highly-regimented process can lead to a number of intestinal diseases [2, 3]. Cytokines and chemokines play a critical role in the integrity of the intestinal epithelium and can initiate and drive intestinal damage [31, 32]. Previously, the inhibitory effect of cytokines, especially TNFα, on ketone body production, was described in isolated hepatocytes and murine and rat models of infection and sepsis [22–24]. HMGCS2, a key enzyme for ketogenesis, plays a central role in ketone body production, and its expression is modulated by several mechanisms such as transcriptional regulation or posttranslational modification [15, 17]. Here, we provide evidence showing that TNFα inhibits βHB production through reduction of endogenous HMGCS2 expression in human intestinal epithelial cells and mouse intestinal organoids. Importantly, we demonstrate a critical role for ketogenesis in TNFα-induced inflammatory responses.

We found that HMGCS2 expression is repressed in the intestinal epithelium from patients with IBD. The expression level and cellular function of HMGCS2 appears to be dependent on the tissue and cell type21. Ketogenesis primarily occurs in the mitochondria of liver cells but is also carried out in the kidney, brain and colon [16, 17]. In addition, HMGCS2 is predominantly expressed in the most differentiated region of the intestinal mucosa and contributes to the regulation of intestinal cell differentiation [20, 46]. Previous studies have shown that HMGCS2 expression was reduced in the mucosa of patients with Crohn’s disease compared to normal mucosa as noted by RNA-seq [27]. Consistent with the results in Crohn’s disease patients, decreased protein expression of HMGCS2 was detected in inflamed tissues of untreated ulcerative colitis patients compared to healthy controls [28]. In our current study, we demonstrate decreased expression of HMGCS2 specifically in the epithelium of the small bowel mucosa from Crohn’s disease patients and colonic mucosa from ulcerative colitis patients compared to normal mucosal samples. Taken together, these data suggest a role for ketogenesis in the pathological process of IBD. Moreover, we also noted a decrease in HMGCS2 levels in colonic mucosa from patients with Crohn’s disease compared with normal controls; however, this difference did not achieve statistical significance possibly due to the small sample size.

TNFα is a critical pro-inflammatory cytokine in IBD. Increased expression of TNFα has been found in the inflamed mucosa of patients with IBD [13]. Therapies that target TNFα are effective for treatment of IBD [8, 10, 11, 14] Our findings demonstrate that an increase in ketogenesis attenuates TNFα-induced apoptosis and inflammatory responses noted by the repressed expression of pro-inflammatory chemokines, CXCL1–3. An inverse correlation between HMGCS2 and CXCL1 expression has been found in Crohn’s disease mucosa [27] and inflamed ulcerative colitis biopsies [47] and in cell lines with decreased HMGCS2 expression [48]. In addition, CXCL1 has tumorigenic and angiogenic effects that contribute to chronic inflammation [27, 49, 50]. Expression of CXCL1–3 is well correlated with the inflammatory status, and the level of CXCL1 is significantly upregulated in the serum and mucosa of IBD patients and in the colonic mucosa of rats and mice with chemical-induced intestinal inflammation [30, 31, 51, 52].

It is becoming increasingly evident that ketogenic diets or the administration of ketone bodies have a beneficial effect on a variety of pathophysiologic conditions including obesity, neurological and neurodegenerative diseases, and physical activity [16, 53, 54]. The administration of a ketogenic diet has been well established in the treatment of pediatric epilepsy [55], the reduction of pain and inflammation [56], and neuroprotective functions in a wide range of disease models [16, 35]. We also showed that an increase in ketogenesis by βHB treatment attenuated TNFα-induced apoptotic responses in intestinal cells. These results suggest a potential role for ketogenic diets in the protection against intestinal epithelial inflammation.

We have shown that HMGCS2 expression in intestinal cells is regulated by PPARγ, a key regulator of lipid and glucose metabolism [21]. Our current studies demonstrate that activation of PPARγ, as an upstream regulator of HMGCS2, suppresses TNFα-induced apoptosis in intestinal epithelial cells. A number of studies have shown that inhibition of PPARγ by cytokines leads to a number of pathological conditions such as inflammation. Moreover, PPARγ agonists (e.g., RGZ) have been demonstrated as effective therapeutic drugs for the prevention and treatment of IBD [38, 57, 58]. Together, our findings indicate a novel protective role of PPARγ/ketogenesis in TNFα-induced apoptosis.

Our current data demonstrate a cross talk between ketogenesis and ROS. H2O2 is one of the main free radical for ROS-induced injury in IBD [45, 59]. TNFα induces the production of ROS including H2O2 as well as the other ROS types in several types of cells [60–62]. We clearly show that inhibition of ketogenesis, by knockdown of HMGCS2, enhances TNFα-induced ROS generation. Aberrant generation of ROS, which is involved in the regulation of immune responses and inflammation, is associated with various cardiovascular and neurological disorders and cancers [63]. Additionally, excessive ROS hinders gastrointestinal function such as nutrient absorption, intestinal permeability and gut motility, suggesting a role for oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of IBD [63, 64]. In agreement with our results, ketone bodies have been shown to inhibit ROS generation, and a ketogenic diet reduces oxidative stress in neuronal tissues [34, 65–68]. Moreover, we found that H2O2 reduces HMGCS2 expression and βHB content in human intestinal cells. These results demonstrate a novel negative feedback loop between ketogenesis and ROS in the process of intestinal inflammation. Repression of ketogenesis disrupted the balance of this feedback loop and may contribute to intestinal inflammation.

In summary, we have shown that decreased ketogenesis is one of the features of TNFα-mediated inflammation in intestinal cells. Furthermore, we show that the protein level of HMGCS2 is dramatically decreased in the intestinal epithelium of IBD patients compared to normal tissues. Activation of PPARγ/ketogenesis pathway attenuated TNFα-induced apoptosis in intestinal cells. Finally, we found that an increase in ketogenesis attenuates TNFα-induced generation of ROS. Taken together, our findings demonstrate a novel role for ketogenesis in TNFα-induced inflammatory responses in intestinal cells (Fig. 8E). Inhibition of ketogenesis may exacerbate intestinal pathologies, and conversely, an increase in ketogenesis may contribute to protection against intestinal inflammation.

Supplementary Material

TNFα suppresses intestinal cell ketogenesis by inhibition of HMGCS2 expression.

Protein levels of HMGCS2 are decreased in human IBD tissues.

HMGCS2 attenuates TNFα-induced apoptosis, CXCL1–3 expression and ROS generation.

Treatment of β-hydroxybutyrate or rosiglitazone alleviates TNFα-induced apoptosis.

ROS represses ketogenesis in intestinal cells.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank the Markey Cancer Center Research Communications Office for editorial support and manuscript preparation. We also thank the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource Facility, the Biospecimen Procurement and Translational Pathology Shared Resource Facility, and the Flow Cytometry and Immune Monitoring Shared Resource Facility of the University of Kentucky Markey Cancer Center. This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute (R01 DK048498 and P30 CA177558).

ABBREVIATIONS

- EV

empty vector

- H2O2

hydrogen peroxide

- HMGCS2

Mitochondrial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase 2

- IBD

inflammatory bowel disease

- NTC

non-targeting control

- RGZ

rosiglitazone

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor α

- βHB

β-hydroxybutyrate

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

STATEMENT OF DATA AVAILABILITY

The data underlying this article are available in the article and in its online supplementary material.

REFERENCES

- [1].Noah TK, Donahue B, Shroyer NF, Intestinal development and differentiation, Exp Cell Res 317(19) (2011) 2702–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Maloy KJ, Powrie F, Intestinal homeostasis and its breakdown in inflammatory bowel disease, Nature 474(7351) (2011) 298–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Negroni A, Cucchiara S, Stronati L, Apoptosis, Necrosis, and Necroptosis in the Gut and Intestinal Homeostasis, Mediators Inflamm 2015 (2015) 250762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Shouval DS, Rufo PA, The Role of Environmental Factors in the Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases: A Review, JAMA Pediatr 171(10) (2017) 999–1005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Seyedian SS, Nokhostin F, Malamir MD, A review of the diagnosis, prevention, and treatment methods of inflammatory bowel disease, J Med Life 12(2) (2019) 113–122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Domenech E, Manosa M, Cabre E, An overview of the natural history of inflammatory bowel diseases, Dig Dis 32(4) (2014) 320–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Pedersen J, Coskun M, Soendergaard C, Salem M, Nielsen OH, Inflammatory pathways of importance for management of inflammatory bowel disease, World journal of gastroenterology 20(1) (2014) 64–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ruder B, Atreya R, Becker C, Tumour Necrosis Factor Alpha in Intestinal Homeostasis and Gut Related Diseases, International journal of molecular sciences 20(8) (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Annibaldi A, Meier P, Checkpoints in TNF-Induced Cell Death: Implications in Inflammation and Cancer, Trends in molecular medicine 24(1) (2018) 49–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Gareb B, Otten AT, Frijlink HW, Dijkstra G, Kosterink JGW, Review: Local Tumor Necrosis Factor-alpha Inhibition in Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Pharmaceutics 12(6) (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Blander JM, Death in the intestinal epithelium-basic biology and implications for inflammatory bowel disease, FEBS J 283(14) (2016) 2720–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Blander JM, On cell death in the intestinal epithelium and its impact on gut homeostasis, Curr Opin Gastroenterol 34(6) (2018) 413–419. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Franca R, Curci D, Lucafo M, Decorti G, Stocco G, Therapeutic drug monitoring to improve outcome of anti-TNF drugs in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease, Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 15(7) (2019) 527–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ungaro R, Mehandru S, Allen PB, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF, Ulcerative colitis, Lancet 389(10080) (2017) 1756–1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Newman JC, Verdin E, Ketone bodies as signaling metabolites, Trends Endocrinol Metab 25(1) (2014) 42–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Puchalska P, Crawford PA, Multi-dimensional Roles of Ketone Bodies in Fuel Metabolism, Signaling, and Therapeutics, Cell metabolism 25(2) (2017) 262–284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Grabacka M, Pierzchalska M, Dean M, Reiss K, Regulation of Ketone Body Metabolism and the Role of PPARalpha, International journal of molecular sciences 17(12) (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Hegardt FG, Mitochondrial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase: a control enzyme in ketogenesis, Biochem J 338 (Pt 3) (1999) 569–82. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Rodriguez JC, Gil-Gomez G, Hegardt FG, Haro D, Peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor mediates induction of the mitochondrial 3-hydroxy-3-methylglutaryl-CoA synthase gene by fatty acids, The Journal of biological chemistry 269(29) (1994) 18767–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Camarero N, Mascaro C, Mayordomo C, Vilardell F, Haro D, Marrero PF, Ketogenic HMGCS2 Is a c-Myc target gene expressed in differentiated cells of human colonic epithelium and down-regulated in colon cancer, Mol Cancer Res 4(9) (2006) 645–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Kim JT, Li C, Weiss HL, Zhou Y, Liu C, Wang Q, Evers BM, Regulation of Ketogenic Enzyme HMGCS2 by Wnt/beta-catenin/PPARgamma Pathway in Intestinal Cells, Cells 8(9) (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Beylot M, Vidal H, Mithieux G, Odeon M, Martin C, Inhibition of hepatic ketogenesis by tumor necrosis factor-alpha in rats, The American journal of physiology 263(5 Pt 1) (1992) E897–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Memon RA, Feingold KR, Moser AH, Doerrler W, Adi S, Dinarello CA, Grunfeld C, Differential effects of interleukin-1 and tumor necrosis factor on ketogenesis, The American journal of physiology 263(2 Pt 1) (1992) E301–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Pailla K, Lim SK, De Bandt JP, Aussel C, Giboudeau J, Troupel S, Cynober L, Blonde-Cynober F, TNF-alpha and IL-6 synergistically inhibit ketogenesis from fatty acids and alpha-ketoisocaproate in isolated rat hepatocytes, JPEN. Journal of parenteral and enteral nutrition 22(5) (1998) 286–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Kim JT, Li J, Song J, Lee EY, Weiss HL, Townsend CM Jr., Evers BM, Differential expression and tumorigenic function of neurotensin receptor 1 in neuroendocrine tumor cells, Oncotarget 6(29) (2015) 26960–70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Kim JT, Napier DL, Weiss HL, Lee EY, Townsend CM Jr., Evers BM, Neurotensin Receptor 3/Sortilin Contributes to Tumorigenesis of Neuroendocrine Tumors Through Augmentation of Cell Adhesion and Migration, Neoplasia 20(2) (2018) 175–181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Hong SN, Joung JG, Bae JS, Lee CS, Koo JS, Park SJ, Im JP, Kim YS, Kim JW, Park WY, Kim YH, RNA-seq Reveals Transcriptomic Differences in Inflamed and Noninflamed Intestinal Mucosa of Crohn’s Disease Patients Compared with Normal Mucosa of Healthy Controls, Inflammatory bowel diseases 23(7) (2017) 1098–1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Schniers A, Goll R, Pasing Y, Sorbye SW, Florholmen J, Hansen T, Ulcerative colitis: functional analysis of the in-depth proteome, Clinical proteomics 16 (2019) 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Stein J, Volk HD, Liebenthal C, Kruger DH, Prosch S, Tumour necrosis factor alpha stimulates the activity of the human cytomegalovirus major immediate early enhancer/promoter in immature monocytic cells, J Gen Virol 74 (Pt 11) (1993) 2333–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Puleston J, Cooper M, Murch S, Bid K, Makh S, Ashwood P, Bingham AH, Green H, Moss P, Dhillon A, Morris R, Strobel S, Gelinas R, Pounder RE, Platt A, A distinct subset of chemokines dominates the mucosal chemokine response in inflammatory bowel disease, Alimentary pharmacology & therapeutics 21(2) (2005) 109–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Wang D, Dubois RN, Richmond A, The role of chemokines in intestinal inflammation and cancer, Current opinion in pharmacology 9(6) (2009) 688–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Andrews C, McLean MH, Durum SK, Cytokine Tuning of Intestinal Epithelial Function, Frontiers in immunology 9 (2018) 1270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Yamanashi T, Iwata M, Kamiya N, Tsunetomi K, Kajitani N, Wada N, Iitsuka T, Yamauchi T, Miura A, Pu S, Shirayama Y, Watanabe K, Duman RS, Kaneko K, Beta-hydroxybutyrate, an endogenic NLRP3 inflammasome inhibitor, attenuates stress-induced behavioral and inflammatory responses, Scientific reports 7(1) (2017) 7677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Lu Y, Yang YY, Zhou MW, Liu N, Xing HY, Liu XX, Li F, Ketogenic diet attenuates oxidative stress and inflammation after spinal cord injury by activating Nrf2 and suppressing the NF-kappaB signaling pathways, Neuroscience letters 683 (2018) 13–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Yang H, Shan W, Zhu F, Wu J, Wang Q, Ketone Bodies in Neurological Diseases: Focus on Neuroprotection and Underlying Mechanisms, Frontiers in neurology 10 (2019) 585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Sikder K, Shukla SK, Patel N, Singh H, Rafiq K, High Fat Diet Upregulates Fatty Acid Oxidation and Ketogenesis via Intervention of PPAR-gamma, Cellular physiology and biochemistry : international journal of experimental cellular physiology, biochemistry, and pharmacology 48(3) (2018) 1317–1331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Xu S, Zhao Y, Yu L, Shen X, Ding F, Fu G, Rosiglitazone attenuates endothelial progenitor cell apoptosis induced by TNF-alpha via ERK/MAPK and NF-kappaB signal pathways, Journal of pharmacological sciences 117(4) (2011) 265–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Vallee A, Lecarpentier Y, Crosstalk Between Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptor Gamma and the Canonical WNT/beta-Catenin Pathway in Chronic Inflammation and Oxidative Stress During Carcinogenesis, Frontiers in immunology 9 (2018) 745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zhang B, Berger J, Hu E, Szalkowski D, White-Carrington S, Spiegelman BM, Moller DE, Negative regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-gamma gene expression contributes to the antiadipogenic effects of tumor necrosis factor-alpha, Molecular endocrinology 10(11) (1996) 1457–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Ye J, Regulation of PPARgamma function by TNF-alpha, Biochemical and biophysical research communications 374(3) (2008) 405–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Dang YF, Jiang XN, Gong FL, Guo XL, New insights into molecular mechanisms of rosiglitazone in monotherapy or combination therapy against cancers, Chemico-biological interactions 296 (2018) 162–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Babbar N, Casero RA Jr., Tumor necrosis factor-alpha increases reactive oxygen species by inducing spermine oxidase in human lung epithelial cells: a potential mechanism for inflammation-induced carcinogenesis, Cancer research 66(23) (2006) 11125–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Yang D, Elner SG, Bian ZM, Till GO, Petty HR, Elner VM, Pro-inflammatory cytokines increase reactive oxygen species through mitochondria and NADPH oxidase in cultured RPE cells, Experimental eye research 85(4) (2007) 462–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Zhou Y, Wang Q, Evers BM, Chung DH, Signal transduction pathways involved in oxidative stress-induced intestinal epithelial cell apoptosis, Pediatric research 58(6) (2005) 1192–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Sasaki M, Joh T, Oxidative stress and ischemia-reperfusion injury in gastrointestinal tract and antioxidant, protective agents, Journal of clinical biochemistry and nutrition 40(1) (2007) 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Wang Q, Zhou Y, Rychahou P, Fan TW, Lane AN, Weiss HL, Evers BM, Ketogenesis contributes to intestinal cell differentiation, Cell Death Differ 24(3) (2017) 458–468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Low END, Mokhtar NM, Wong Z, Raja Ali RA, Colonic Mucosal Transcriptomic Changes in Patients with Long-Duration Ulcerative Colitis Revealed Colitis-Associated Cancer Pathways, Journal of Crohn’s & colitis 13(6) (2019) 755–763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Chen SW, Chou CT, Chang CC, Li YJ, Chen ST, Lin IC, Kok SH, Cheng SJ, Lee JJ, Wu TS, Kuo ML, Lin BR, HMGCS2 enhances invasion and metastasis via direct interaction with PPARalpha to activate Src signaling in colorectal cancer and oral cancer, Oncotarget 8(14) (2017) 22460–22476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Kuo PL, Shen KH, Hung SH, Hsu YL, CXCL1/GROalpha increases cell migration and invasion of prostate cancer by decreasing fibulin-1 expression through NF-kappaB/HDAC1 epigenetic regulation, Carcinogenesis 33(12) (2012) 2477–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Han KQ, He XQ, Ma MY, Guo XD, Zhang XM, Chen J, Han H, Zhang WW, Zhu QG, Zhao WZ, Targeted silencing of CXCL1 by siRNA inhibits tumor growth and apoptosis in hepatocellular carcinoma, International journal of oncology 47(6) (2015) 2131–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Boshagh MA, Foroutan P, Moloudi MR, Fakhari S, Malakouti P, Nikkhoo B, Jalili A, ELR positive CXCL chemokines are highly expressed in an animal model of ulcerative colitis, Journal of inflammation research 12 (2019) 167–174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Shang K, Bai YP, Wang C, Wang Z, Gu HY, Du X, Zhou XY, Zheng CL, Chi YY, Mukaida N, Li YY, Crucial involvement of tumor-associated neutrophils in the regulation of chronic colitis-associated carcinogenesis in mice, PloS one 7(12) (2012) e51848. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Newman JC, Verdin E, beta-Hydroxybutyrate: A Signaling Metabolite, Annu Rev Nutr 37 (2017) 51–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Murphy EA, Jenkins TJ, A ketogenic diet for reducing obesity and maintaining capacity for physical activity: hype or hope?, Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care 22(4) (2019) 314–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Neal EG, Chaffe H, Schwartz RH, Lawson MS, Edwards N, Fitzsimmons G, Whitney A, Cross JH, The ketogenic diet for the treatment of childhood epilepsy: a randomised controlled trial, The Lancet. Neurology 7(6) (2008) 500–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Ruskin DN, Kawamura M, Masino SA, Reduced pain and inflammation in juvenile and adult rats fed a ketogenic diet, PloS one 4(12) (2009) e8349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Vetuschi A, Pompili S, Gaudio E, Latella G, Sferra R, PPAR-gamma with its anti-inflammatory and anti-fibrotic action could be an effective therapeutic target in IBD, European review for medical and pharmacological sciences 22(24) (2018) 8839–8848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Decara J, Rivera P, Lopez-Gambero AJ, Serrano A, Pavon FJ, Baixeras E, Rodriguez de Fonseca F, Suarez J, Peroxisome Proliferator-Activated Receptors: Experimental Targeting for the Treatment of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases, Frontiers in pharmacology 11 (2020) 730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].McKenzie SJ, Baker MS, Buffinton GD, Doe WF, Evidence of oxidant-induced injury to epithelial cells during inflammatory bowel disease, J Clin Invest 98(1) (1996) 136–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Hoffman M, Weinberg JB, Tumor necrosis factor-alpha induces increased hydrogen peroxide production and Fc receptor expression, but not increased Ia antigen expression by peritoneal macrophages, J Leukoc Biol 42(6) (1987) 704–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Radeke HH, Meier B, Topley N, Floge J, Habermehl GG, Resch K, Interleukin 1-alpha and tumor necrosis factor-alpha induce oxygen radical production in mesangial cells, Kidney Int 37(2) (1990) 767–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Young CN, Koepke JI, Terlecky LJ, Borkin MS, Boyd SL, Terlecky SR, Reactive oxygen species in tumor necrosis factor-alpha-activated primary human keratinocytes: implications for psoriasis and inflammatory skin disease, J Invest Dermatol 128(11) (2008) 2606–2614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Bourgonje AR, Feelisch M, Faber KN, Pasch A, Dijkstra G, van Goor H, Oxidative Stress and Redox-Modulating Therapeutics in Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Trends in molecular medicine (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Bhattacharyya A, Chattopadhyay R, Mitra S, Crowe SE, Oxidative stress: an essential factor in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal mucosal diseases, Physiol Rev 94(2) (2014) 329–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Maalouf M, Sullivan PG, Davis L, Kim DY, Rho JM, Ketones inhibit mitochondrial production of reactive oxygen species production following glutamate excitotoxicity by increasing NADH oxidation, Neuroscience 145(1) (2007) 256–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Stafford P, Abdelwahab MG, Kim DY, Preul MC, Rho JM, Scheck AC, The ketogenic diet reverses gene expression patterns and reduces reactive oxygen species levels when used as an adjuvant therapy for glioma, Nutrition & metabolism 7 (2010) 74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Greco T, Glenn TC, Hovda DA, Prins ML, Ketogenic diet decreases oxidative stress and improves mitochondrial respiratory complex activity, Journal of cerebral blood flow and metabolism : official journal of the International Society of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 36(9) (2016) 1603–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Pinto A, Bonucci A, Maggi E, Corsi M, Businaro R, Anti-Oxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Activity of Ketogenic Diet: New Perspectives for Neuroprotection in Alzheimer’s Disease, Antioxidants 7(5) (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.