Abstract

Background:

Impulsivity has been identified as playing a role in cocaine use. The purpose of this study was to explore self-report measures of impulsivity in large groups of male and female cocaine users and matched controls and to determine if differences in impulsivity measures within a group of cocaine users related to self-reported money spent on cocaine and route of cocaine use.

Methods:

Eight self-report impulsivity measures yielding 34 subscales were obtained in 230 cocaine users (180M, 50F) and a matched group of 119 healthy controls (89M, 30F). Correlational analysis of the questionnaires revealed 2 factors: Impulsive Action (Factor 1) consisting of many traditional impulsivity measures and Thrill-seeking (Factor 2) consisting of delay discounting, sensation and thrill seeking.

Results:

Sex influenced within group comparisons. Impulsive Action scores did not vary as a function of sex within either group. But, male controls and male cocaine users had greater Thrill-seeking scores than females within the same group. Sex also influenced between group comparisons. Male cocaine users had greater Impulsive Action scores while female cocaine users had greater Thrill-seeking scores than their sex-matched controls. Among cocaine users, individuals who preferred insufflating (“snorting”) cocaine had greater Thrill-seeking scores and lower Impulsive Action scores than individuals who preferred smoking cocaine. Individuals who insufflate cocaine also spent less money on cocaine.

Conclusions:

Greater Impulsive Action scores in males and Thrill-seeking scores in females were associated with cocaine use relative to controls.

Keywords: Impulsivity, Delay discounting, sensation-seeking, cocaine, preferred route, Sex Differences

1. Introduction

Cocaine users are more impulsive based on self-report measures and discount the value of future rewards at a faster rate than non-cocaine users, suggesting that impulsive behavior plays a role in cocaine abuse. Evenden (1999) defined impulsive behaviors as “…actions that are poorly conceived, prematurely expressed, unduly risky, or inappropriate to the situation and that often result in undesirable outcomes (p.348).” Variations in behavioral impulsivity are reliably related to a range of disorders, including drug abuse, and can be predictive of other psychiatric disorders (Koritzky et al., 2012; Reimers et al., 2009; Swann et al., 2002) as well asresponse to treatment (e.g., MacKillop and Kahler, 2009). Accordingly, Robbins et al. (2012) argued that the impulsivity construct is an ideal “neurocognitive endophenotype” that is a unifying dimension across a range of psychiatric disorders. The purpose of this study was to 1) explore self-report measures of impulsivity in large groups of cocaine users and matched controls and 2) determine if differences in impulsivity measures within a group of cocaine users related to self-reported amount of money spent on cocaine and preferred route of cocaine use.

Cocaine users have elevated scores on many self-report measures of impulsivity (Vonmoos et al., 2013; Davis et al., 2008) and greater impulsivity is associated with drug use (Moeller et al., 2001; de Wit, 2009). Specifically, higher impulsivity as measured by the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11; Patton et al., 1995) is associated with quantity of cocaine use and severity of withdrawal symptoms (Hulka et al., 2015; Moeller et al., 2001), earlier onset of cocaine use (Lister et al., 2015), increased likelihood of cocaine dependence (Ahn et al., 2016), longer duration of cocaine use, and increased craving (Vonmoos et al., 2013). Further, self-reported impulsivity appears to increase with chronic cocaine exposure (Ersche et al., 2010), and may negatively impact treatment retention (Moeller et al., 2001; Poling et al., 2007). A limitation of previous studies is that they commonly utilized only one or two self-reportmeasures of impulsivity. By contrast, in the present study we assessed 4 commonly used self-report measures of impulsive traits: the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11; Patton et al., 1995); Eysenck’s Impulsivity Questionnaire (IQ;Eysenck et al., 1985); Zuckerman’s Sensation-Seeking Scale (SSS; Zuckerman et al., 1978); and the UPPS Impulsive Behavior scale (UPPS; Whiteside and Lynam, 2001). Use of all four measures enables a more comprehensive understanding of self-reported impulsivity and allows a more nuanced comparison to prior work.

Temporal or delay discounting which refers to a decrease in the perceived value of a reward as the time to its delivery increases may be a proxy measure of impulsivity (Bickel et al., 2008), and in a large population sample was associated with more self-reported impulsive behaviors (Reimers et al., 2009). Drug users commonly discount the value of future rewards more than healthy controls (Coffey et al., 2003; MacKillop et al., 2011). Cocaine-dependent individuals are more likely to discount delayed rewards than healthy controls (Cox et al., 2020, Heil et al., 2006; Johnson et al., 2015; Kirby and Petry, 2004) and higher delay discounting appears to predict likelihood of cocaine dependence (Ahn et al., 2016). Greater discounting also has clinical applications. For example, cocaine-dependent (Washio et al., 2011) individuals who discounted future rewards more quickly also responded more poorly to treatment. Some work suggests that greater delay discounting persists after periods of abstinence in cocaine users suggesting that steeper delay discounting is a vulnerability that predates cocaine use rather than a result of cocaine use (Heil et al., 2006; Kirby and Petry, 2004; Mendez et al., 2010; Simon et al., 2007). In the present study we assessed delay discounting using the Kirby et al. (1999) self-report questionnaire. We also administered the Delaying Gratification Inventory (Hoerger et al., 2011), the Sensitivity to Reward subscale on the Behavioral Activation System and the Sensitivity to Punishment subscale on the Behavioral Inhibition System (BIS/BAS - Carver and White, 1994) as self-report measures of reward value and temporal discounting.

Some differences in impulsivity have been observed among cocaine users based on their route of cocaine use (Reed and Evans, 2016). Smoked cocaine users scored higher on the self-reported BIS-II relative to users who insufflated cocaine. A comparison of treatment outcomes (Kiluk et al., 2013) suggests that those who primarily smoked cocaine had poorer treatment outcomes than those who primarily insufflated cocaine. Perhaps lower impulsivity may be associated with better treatment outcomes. Further work is needed to determine the degree to which impulsivity impacts preferred route of cocaine administration and associated clinical outcomes.

With respect to sex differences, although several papers have concluded than men are generally more impulsive than women and have more disorders associated with impulse control (e.g., Chamorro et al., 2012; Strüber et al., 2008), the effects are modest. A large scale analysis of early BIS data failed to find sex differences (Patton et al., 1995). A meta-analysis of 277 studies examining impulsivity (Cross et al., 2011) concluded that females were more punishment sensitive, perhaps contributing to less risky decision-making (Stoltenberg et al., 2008), while males were more likely to be sensation seekers and behavioral risk-takers. Studies of cocaine users have not had sufficient sample sizes of males and females to conduct direct comparisons. In the present study a sufficient sample size was obtained to investigate the interactive effects of sex and impulsivity on the amount of cocaine use.

Previous studies in cocaine users have commonly 1) used modest sample sizes, 2) lacked matched-controls and 3) assessed only 1 or 2 self-report measures. The present study addressed all of these limitations. We assessed a range of self-report measures of impulsivity in large samples of male and female cocaine users and sex-matched non-cocaine using controls. We examined the correlational structure of the self-report measures independently ignoring group membership. We hypothesized that 1) cocaine users of both sexes would be more impulsive than controls and in contrast to controls female cocaine users would be more impulsive than male cocaine users, 2) greater levels of impulsivity would be associated with greater cocaine use, and 3) individuals who smoke cocaine would be more impulsive than individuals who insufflate cocaine.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

The majority of the participants in this study were recruited using advertisements in local newspapers. A smaller number responded to volunteer listings in the New York city region on Google and some were referred by other participants. The advertisements targeted cocaine users who smoke cocaine, cocaine users who “snort” cocaine, and non-drug using individuals between the ages of 18 to 63. Individuals were told that the purpose of the study was to determine how decision making was affected by cocaine use and whether individuals who use cocaine differ from those who do not on multiple measures of decision making: impulsivity was not specifically mentioned. The Institutional Review Board of the New York State Psychiatric Institute approved this study. Participants gave their written informed consent before beginning the study and were paid for their involvement.

Over 2,500 individuals were screened by phone and of those 658 cocaine users (482M, 176F) and 282 healthy controls (219M, 63F) were enrolled. The lower number of controls was due to the difficulty in matching to the cocaine group. 230 cocaine users (180M, 50F) and 119 healthy controls (89M, 30F) met criteria for study participation and completed all study assessments.

Drug use of all participants was carefully assessed via self-report by phone, then during an interview with an experienced researcher, and finally a structured clinical interview. Drug toxicology via urinalysis was conducted at each study visit. Individuals reporting wide ranges of cocaine use by varying routes of administration were included. Because occasional cocaine users were included in the sample, a positive cocaine urine sample was not required for study admission. Healthy controls could not report any regular lifetime use of cocaine or any use within the past 6 months. Drug use other than cocaine was allowed in both groups, but dependence on drugs other than nicotine and caffeine was exclusionary.

2.2. Procedures

Following telephone screening, eligible applicants were invited to the laboratory to provide informed consent, provide a urine sample for drug screening, have a breathalyzer test for recent alcohol use, complete demographic and drug use questionnaires and have drug use assessed by an experienced researcher. Social status was estimated using the Barratt Simplified Measure of Social Status (BSMSS; permission granted by William Barratt). The BSMSS provides an ordinal measure of social status based on a participant’s marital status, retired/employed status (retired individuals used their last occupation) educational attainment, and occupational prestige, and their parent’s educational attainment and occupational prestige.

Eligible participants were then scheduled for an extensive clinical interview conducted by a masters- or PhD-level psychologist. Participants were administered a standard battery of structured clinical interviews and intelligence/achievement tests, comprised of a) The MINI International Neuropsychiatric Interview for DSM-5 (Sheehan, 2014) assessing psychiatric diagnoses, b) Substance use history; c) Assessment of neurodevelopmental disorders and ADHD; and d) Word-Reading, Block Design and Vocabulary assessments (WRAT-4; WAIS-IV; Ringe et al., 2002). Participants were excluded from study participation if they met any of the following ineligibility criteria based on the research protocol: a) DSM-5 severe Substance Use Disorder criteria for drugs other than cocaine, nicotine and caffeine within the past 12 months; b) current DSM-5 criteria for other major psychiatric disorders (other than specific phobias or Major Depressive Disorder); c) diagnosis of a neurodevelopmental disorder; and d) low neurocognitive scores as defined by 2 or more scores below the 5th percentile.

Individuals who passed the clinical assessments then attended 1 or 2 laboratory sessions during which they completed a battery of self-report questionnaires. Participants were instructed to not use drugs including cocaine for 3 days before testing sessions and this was confirmed via urine and breath samples. Individuals who presented intoxicated or had positive breath alcohol or urine samples (excluding marijuana) were rescheduled for another day.

2.3. Self-report Questionnaires

We administered 4 self-report assessments of impulsive traits: the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale (BIS-11; Patton et al., 1995); Eysenck’s Impulsivity Questionnaire (IQ; Eysenck et al., 1985); Zuckerman’s Sensation-Seeking Scale (SSS; Zuckerman et al., 1978); and the Impulsive Behavior scale (UPPS; Whiteside and Lynam, 2001). Decision-making styles were assessed using the Melbourne Decision-Making Scale (MDMQ; Mann et al., 1997). We obtained 3 self-report measures of reward salience and discounting: the Delaying Gratification Inventory (DGI; Hoerger et al., 2011), the Behavioral Inhibition Scale/Behavioral Activation System (BIS/BAS; Carver and White, 1994) and a standardized delay-discounting questionnaire (DD; Kirby et al., 1999). All paperwork completed by participants was double checked by staff to confirm that all forms were completely and legibly filled out. All of the self-report questionnaires yield multiple measures.

2.4. Data Analysis

2.4.1. Demographics and Self-reported Questionnaire Comparisons.

To compare demographics and self-reported impulsivity items between cocaine users and healthy controls, two-sample t-tests were conducted for continuous measures and chi-square tests were conducted for categorical variables. The difference in each self-reported impulsivity subscale between these two groups and the standard deviation for the difference were plotted in the figures (forest plots). Stratified analyses by sex were conducted to investigate whether associations differed between males and females. Additionally, within cocaine users and within healthy controls respectively, we compared the self-reported items between males and females by two-sample t-tests. The effect of age (continuous variable), marital (single vs. married/cohabitating) and employment status (unemployed vs. employed) on each self-reported impulsivity subscale and the two factor scores between these two groups were examined using linear regressions. Due to the relatively small sample sizes these analyses were not stratified by sex.

2.4.2. Correlations Amongst Measures and Factor Analyses.

Pearson correlations were plotted for each pair of impulsivity measures. Variables were ordered by similarity using angular order of the eigenvectors of the correlation matrix (each variable was represented by a vector whose endpoint was the coordinates of the first two eigenvectors, and then the variables were ordered by the angle of this vector; Friendly, 2002) in the correlation plot. Exploratory factor analyses were conducted for the self-reported items separately. The factor loadings for each item on each latent factor were summarized. Based on the fitted factor models, factor scores for each participant were estimated by Thomson’s regression method (Thomson, 1935). The mean and median values of the factor scores for the cocaine users and healthy controls were compared by two-sample t-tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, respectively.

2.4.3. Associations between Self-reported Cocaine Use and Impulsivity Measures.

The associations between cocaine use, based on how much money (USD) participants reported they spent weekly on cocaine, and the impulsivity measures were determined using simple linear regressions with log-transformed cocaine use amount as the outcome (amounts were transformed to account for the skewed distribution) and each impulsivity measure as the predictor. The estimated regression coefficients, confidence intervals and the p-values were determined. Stratified analysis by sex was conducted to examine whether the association differed between males and females. Association between weekly self-reported cocaine use and the factors scores among cocaine users were examined using linear regression with the log-transformed cocaine use amount as the outcome and the estimated factor scores as the predictors adjusted for age, sex and BSMSS. Stratified analyses by sex were conducted to investigate whether the associations differed between males and females.

2.4.4. Preferred Route of Cocaine Taking.

Whether the self-reported items differed by the preferred route of cocaine intake was examined. Mean and median values of cocaine use amount by preferred route of intake were compared by two-sample t-tests and Wilcoxon rank-sum tests, respectively. Stratified analyses by sex were not conducted due to the small sample sizes of female cocaine users with differing route preferences.

All analyses were conducted in R (The R Project for Statistical Computing; https://www.r-project.org).

3. Results

3.1. Participants

As shown in Table 1, 658 cocaine users (482M, 176F) and 282 healthy controls (219M, 63F) passed the telephone screening and provided informed consent. Although not statistically different, approximately 30% of the cocaine users and 20% of the controls were excluded during the clinical interview. Although the number of participants excluded for neurocognitive, psychiatric and other substance use reasons varied amongst the 4 participant groups these differences were not statistically significant. Approximately one third of both groups dropped out of the study by failing to attend scheduled appointments.

Table 1.

Number of Participants Screened and Study Outcome.

| Female Cocaine User | Control | Male Cocaine User | Control | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number Screened | 176 | 63 | 482 | 219 |

| Clinically Excluded (percentage) | 57 (32 %) | 12 (19 %) | 138 (28 %) | 50 (23 %) |

| Neurocognitive | 21 | 7 | 56 | 16 |

| Psychiatric Disorder | 30 | 5 | 44 | 16 |

| Other Substance Use | 18 | 1 | 58 | 4 |

| Dropped Out (percentage) | 69 (39 %) | 21 (33 %) | 164 (34 %) | 80 (36 %) |

| Completed (percentage) | 50 (28 %) | 30 (48 %) | 180 (37 %) | 89 (41 %) |

As shown in Table 2 50 female cocaine users, 30 female controls, 180 male cocaine users and 89 male controls met criteria for study participation and completed all study assessments for a total of 230 cocaine users (180M, 50F) and 119 healthy controls (89M, 30F). Female participants ranged in age from 23 to 59 and male participants ranged in age from 18 to 61. Male cocaine users were significantly older than male controls by an average of 3 years. About 80% of participants self-identified as Black and about 20% of the participants self-identified as Latinx with no significant differences between groups within each sex. The minority of participants were married or cohabitating. Importantly, male and female cocaine users did not differ from controls in the BSMSS measure of social status. Female cocaine users and female controls had similar distributions of education history. In contrast male cocaine users differed from male controls in education with a greater proportion of male controls receiving a High School diploma than male cocaine users [graduate equivalent degree (GED) holders were not included in the HS graduate group]. Female and male cocaine users were twice as likely as female and male controls to be unemployed. While a greater proportion of cocaine users than controls had histories of arrest, this difference was only statistically significant in males. In most cases, for both sexes, a greater proportion of cocaine users than controls used alcohol, cannabis and tobacco on a weekly basis.

Table 2.

Demographics of Study Completers.

| Female Cocaine User | Control | Male Cocaine User | Control | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of Completers | 50 | 30 | p-Value | 180 | 89 | p-Value |

| Age (range) | 46.5 (23–59) | 45.4 (35–55) | 0.5996 | 48.5 (18–60) | 45.4 (25–61) | 0.0061 |

| Ethnicity (percentage) | ||||||

| Black | 84 % | 83 % | 0.9322 | 79% | 80 % | 0.8463 |

| Latinx | 12 % | 27 % | 0.0946 | 14 % | 22 % | 0.0999 |

| Marital Status (percentage) | ||||||

| Married/Cohabitating | 36 % | 23 % | 0.417 | 13 % | 25 % | 0.0507 |

| Social Status | ||||||

| BSMSS Score | 29.6 | 33.7 | 0.1438 | 30.4 | 31.8 | 0.3412 |

| Education Level (percentage) | ||||||

| HS/ College Graduate | 14 %/ 12 % | 7 %/ 17 % | 0.2785 | 9%/ 18 % | 22 %/ 12 % | 0.0074 |

| Employment (percent employed) | 24 % | 50 % | 0.0173 | 28 % | 47 % | 0.0016 |

| History of Arrest (percentage) | 42 % | 23 % | 0.0901 | 63% | 39 % | 0.0002 |

| Other Weekly Drug Use (percentage) | ||||||

| Alcohol | 54 % | 13 % | 0.0003 | 67 % | 52 % | 0.0174 |

| Cannabis | 32 % | 10 % | 0.0252 | 32 % | 21 % | 0.0634 |

| Tobacco | 82 % | 20 % | 0.0001 | 76% | 56 % | 0.0008 |

Age compared using t-tests, other variables compared using chi-square tests.

3.2. Self-reported Questionnaire and Computerized-Task Assessments

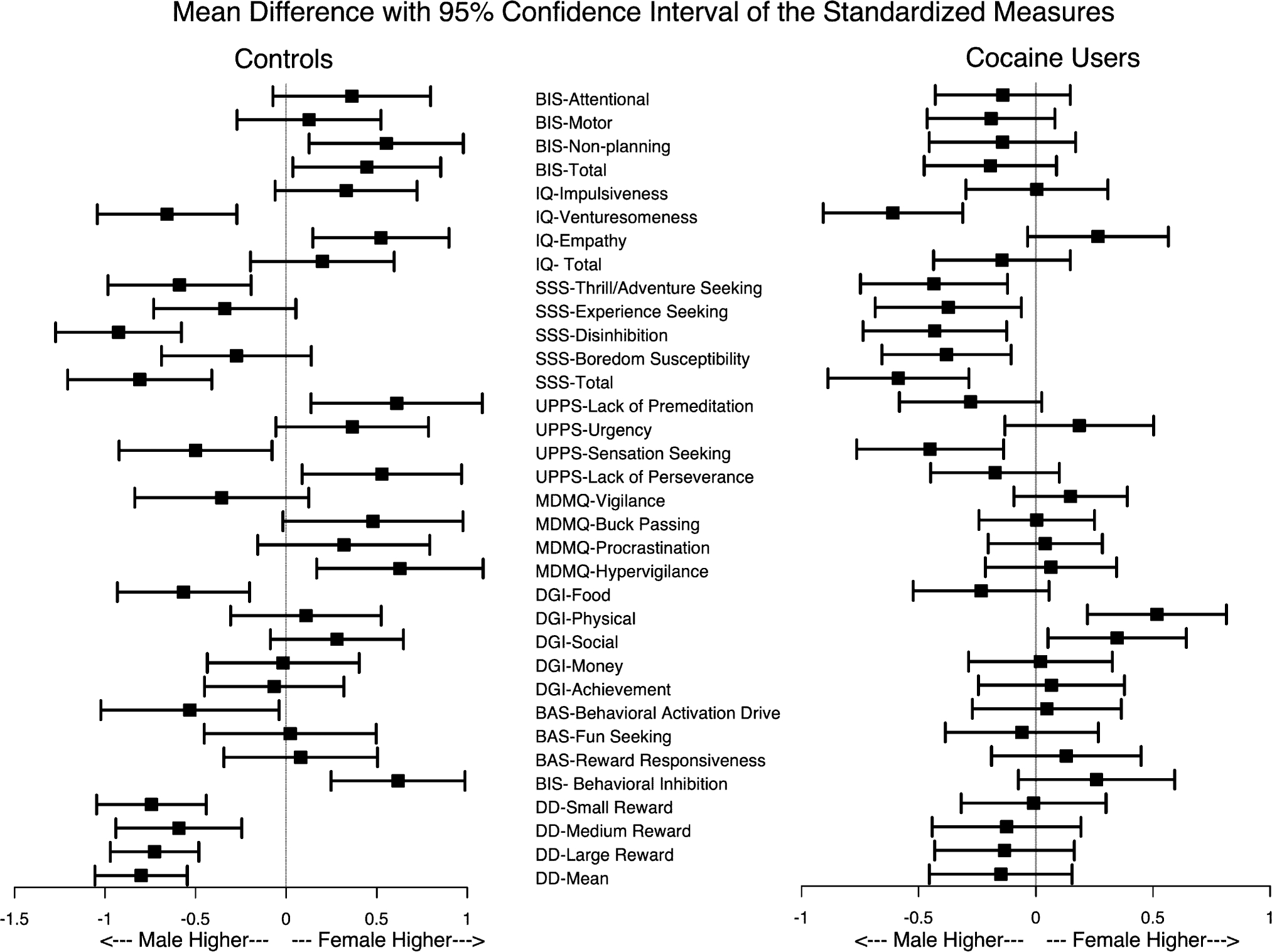

Figure 1 compares the mean difference between standardized scores (each score was standardized to a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1) on the self-report questionnaires between the males and females in each group. Female and male controls (left panel) differed significantly on 18 of the self-report subscales. Female controls scored higher on traditional impulsivity questionnaires such as the BIS and IQ, while male controls scored higher on measures of sensation seeking (e.g., SSS) and had higher scores on the delay-discounting (DD) questionnaire. Female and male cocaine users (right panel) differed significantly on 9 of the self-report subscales. Males again scored higher on measures of sensation seeking while females score higher on several of the items on the DGI (greater scores indicate greater ability to delay reinforcement). In contrast to controls, there were no differences in delay discounting between female and male cocaine users.

Figure 1.

Mean difference in standardized scores (each score was standardized to a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1) on the self-report questionnaires between the males and females in the control (left panel) group and cocaine-user (right panel) group.

Figure 2 compares the mean difference between the standardized scores on the self-report questionnaires between the cocaine users and controls for females and males. Female cocaine users differed from female controls on 8 self-report subscales with female cocaine users having several greater sensation seeking scores, several lower delaying gratification scores and higher delay discounting scores. In contrast, male cocaine users differed from male controls on 22 self-report subscales. Male cocaine users had greater scores on many measures of impulsivity and lower scores on all 5 delaying gratification scales. In contrast to females, there were no differences in delay discounting between male cocaine users and male controls.

Figure 2.

Mean difference in standardized scores (each score was standardized to a mean of 0 and a standard deviation of 1) on the self-report questionnaires between the cocaine users and controls for females (left panel) and males (right panel).

Cocaine users differed from controls on 20 self-report subscales when age, employment and marital status each were not included in the regressions. Including age or marital status in the regressions resulted in the same 20 significant subscales but added one additional subscale (MDMQ-Buck Passing) as significantly different between groups. Including employment status in the regressions did not affect the outcome. Similarly, cocaine users differed from controls on both Factor scores when age, employment and marital status each were not included in the regressions. These three demographic variables did not alter the differences in the impulsivity measures between the group of cocaine users and the group of controls. Marital and employment status did not affect the Factors scores after controlling for group. Age however affected the Thrill-seeking Factor, with Thrill-seeking Factor scores significantly decreasing with increasing age (p-value <0.002).

3.3. Correlations Amongst Measures and Factor Analyses

Figure 3 shows the correlation matrix for each pair of self-report impulsivity measures. The correlations are color coded such that blue represents a positive correlation with darker shades of blue representing greater positive correlations and orange-red represent a negative correlation with darker shades of red representing greater negative correlations. Looking at the data along the diagonal representing each measure correlated with itself suggests that four behavioural domains were assessed. As shown in the upper left corner, the delay discounting measures correlated positively with each other and minimally to the other measures: delay discounting domain. The next lower blue box along the diagonal contains mostly the delaying-gratification items (DGI) where higher scores are indicative of greater ability to delay gratification: delaying gratification domain. These items correlate positively with each other but correlate negatively with the items in the slightly light blue colored box next down the diagonal. This box contains the common measures of impulsivity such as the BIS and Eysenck scores: greater scores on measures of impulsivity are negatively related to ability to delay gratification: impulsivity domain. Further down the diagonal are 6 items related to fun-seeking that are slightly correlated with each other and to the 3 items next on the diagonal, but not correlated to delay discounting or the delay gratification and impulsivity items above. At the far-right the bottom 3 items that measure thrill seeking are strongly correlated with each other and slightly correlated with the fun-seeking group, but not correlated with the impulsivity or delay-discounting group. These later 2 groups comprise a sensation/thrill seeking domain.

Figure 3.

Correlation matrix for each pair of self-report impulsivity measures. The correlations are color coded such that blue represents a positive correlation with darker shades of blue representing greater positive correlations and red represents a negative correlation with darker shades of red representing greater negative correlations.

Table 3 shows the loading scores for all of the self-report items that had a loading of 0.3 or greater in the factor analysis for the first 2 Factors that accounted for the majority of the variance. All of the delaying gratification measures loaded negatively (greater scores indicate greater ability to delay a reward) and the established self-report impulsivity measures loaded positively in Self-report Factor 1 (Impulsive Action Factor). All of the delay discounting measures and the thrill- and fun-seeking measures loaded positively on Self-report Factor 2 (Thrill-seeking Factor).

Table 3.

Results of Factor Analysis

| Factor 1 (Impulsive Action) | Factor 2 (Thrill-seeking) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Loading | Item | Loading |

| Delaying Gratification Domain | Delay Discounting Domain | ||

| DGI - Physical | −0.7 | Delay Discounting – Small Reward | 0.4 |

| DGI – Money | −0.7 | Delay Discounting – Medium Reward | 0.4 |

| DGI – Achievement | −0.7 | Delay Discounting – Large Reward | 0.4 |

| DGI – Food | −0.5 | Delay Discounting – Mean | 0.4 |

| DGI – Social | −0.4 | Sensation/Thrill Seeking Domain | |

| Impulsivity Domain | SSS – Experience Seeking | 0.4 | |

| IQ – Empathy | 0.3 | BAS – Drive | 0.4 |

| SSS – Boredom Susceptibility | 0.3 | SSS – Disinhibition | 0.5 |

| BIS – Motor | 0.4 | BAS – Fun Seeking | 0.5 |

| MDMQ – Buck Passing | 0.5 | SSS – Thrill and Adventure Seeking | 0.7 |

| MDMQ – Procrastination | 0.5 | IQ – Venturesomeness | 0.8 |

| MDMQ- Vigilance | 0.6 | UPPS – Sensation Seeking | 0.8 |

| BIS – Attentional | 0.7 | ||

| BIS – Non-planning | 0.7 | ||

| IQ – Impulsiveness | 0.7 | ||

| UPPS – Lack of Premeditation | 0.7 | ||

| UPPS – Lack of Perseverance | 0.7 | ||

| BIS – Behavioral Inhibition | 0.7 | ||

| UPPS – Urgency | 0.8 |

As a group, cocaine users had greater Impulsive Action Factor (p-value <0.0001) and Thrill-seeking Factor (p-value < 0.006) scores than the control group. The rank order of Impulsive Action Factor median scores was male controls (−0.69) < female controls (−0.30) < female cocaine users (0.12) < male cocaine users (0.15). Male, but not female cocaine users had greater Impulsive Action Factor scores than sex-matched controls (p-value <0.00001). The rank order of Thrill-seeking Factor median scores was female controls (−1.08) < female cocaine users (−0.27) < male controls (0.03) < male cocaine users (0.32). Female, but not male cocaine users had greater Thrill-seeking Factor scores than sex-matched controls (p-value <0.006).

3.4. Association between Self-reported Cocaine Use and Impulsivity Measures

Figure 4 shows the US dollar amount each cocaine-using participant reported spending on cocaine each week. For females only the self-report Eysenck empathy and the MDMQ Procrastination scores were related to cocaine use with greater scores associated with less cocaine use per week. Neither factor score was predictive of cocaine use in female cocaine users. No self-report measure nor the factor scores were significantly related to self-reported cocaine use in male cocaine users.

Figure 4.

United States dollar amount each cocaine-using participant reported spending on cocaine each week for females (left panel) males (right panel). Data points are not shown for 3 females and 7 males who reported spending >$500/week on cocaine.

3.5. Preferred Route of Cocaine Taking

Preferred route of cocaine use and money (USD) spent per week on cocaine was available for 217 cocaine users (49F, 168M). Fifteen females preferred to insufflate cocaine, 24 females preferred to smoke cocaine and 10 females had no preference. Fifty males preferred to insufflate cocaine, 91 males preferred to smoke cocaine and 37 males had no preference. Thus 180 cocaine users had clear route of use preferences: 65 preferred to insufflate cocaine and 115 preferred to smoke cocaine. Individuals who preferred to smoke cocaine spent significantly (p-value <0.004) more on cocaine, spending a median of $120/week, compared to those who insufflated cocaine, spending a median of $50/week on cocaine. As shown in Figure 5, 9 standardized self-report measures were significantly different between those who preferred to insufflate and those who preferred to smoke cocaine. Individuals who preferred to smoke cocaine had greater impulsivity scores on the BIS and lack of perseverance scores on the UPPS, while individuals who preferred to insufflate cocaine had greater sensation seeking scores on the UPPS and greater delaying money and achievement scores on the DGI. Individuals who preferred to insufflate cocaine had lower median scores on Impulsive Action Factor 1 (−0.18 vs. 0.25; p-value <0.026) and greater median scores on Thrill-seeking Factor (0.47 vs. −0.06; p-value <0.026) than individuals who smoked cocaine.

Figure 5.

Mean difference in standardized scores (each score was standardized to a mean of 0 and standard deviation of 1) on the self-report questionnaires between the cocaine users who preferred to smoke cocaine and the cocaine users who preferred to insufflate cocaine.

4. Discussion

Analysis of the correlation matrix of the self-report measures indicated that the measures assessed 4 behavioral domains: 1) delay discounting, 2) delaying gratification, 3) impulsivity and 4) sensation/thrill seeking. The factor analysis of the self-report measures yielded 2 factors. Factor 1 (Impulsive Action) consisted of the traditional measures of impulsivity, e.g., BIS, UPPS, Eysenck, and the delaying gratification measures, i.e., impulsivity and delaying gratification domains. Measures of impulsivity were weighted positively while the measures of delaying gratification were weighted negatively, e.g., greater DGI scores are associated with greater ability to delay gratification. Factor 2 (Thrill-seeking) consisted of the measures of delay discounting and the measures of sensation and thrill seeking with both groups weighted positively, i.e., delay discounting and sensation/thrill seeking domains. Male controls and male cocaine users were greater Thrill-seekers than females. A sex-dependent pattern emerged when healthy controls were compared to cocaine users. Male cocaine users had greater Impulsive Action Factor scores than male controls while female cocaine users had greater Thrill-seeking Factor scores than female controls. Smoked cocaine use was associated with greater Impulsive Action Factor scores but lower Thrill-seeking Factor scores: the small sample size of females precluded including sex as a variable in the analysis of route preference. Finally, there was little evidence that measures of impulsivity were related to amount of self-reported cocaine use for either sex.

One goal of this study was to recruit a similar number of age-, ethnicity-, sex- and social status-matched healthy controls and cocaine users with similar amounts of tobacco use. In spite of screening by phone over 2500 individuals this proved impossible and the control groups were about half the size of the cocaine using groups. Although the male cocaine users were on average 3 years older than the male controls, the groups were otherwise well matched, e.g., ethnicity, marital and social status. Females did not differ on education levels. The education distribution varied for males with fewer male cocaine users finishing high school than controls but more male cocaine users graduated college than male controls. Cocaine users were less likely to be employed (~25% vs ~50% employment for both sexes) and more male cocaine users had spent time in jail compared to the male controls. For the most part cocaine users also used more alcohol, cannabis and tobacco than controls. In contrast to expectations there was no evidence that the cocaine users had greater clinical issues than controls or were less reliable in making appointments than relatively matched controls.

Although employment/income (Daly et al., 2015; Reimers et al., 2009), marital status (Blair and Menasco, 2016) and age (Reimers et al., 2009) can affect impulsivity these demographic variables did not alter the differences between cocaine users and controls in self-reported measures of impulsivity. Increasing age was significantly associated with decreasing Thrill-seeking factor scores. It is possible that greater impulsivity, when these variables are controlled for, is a risk factor for, or an antecedent to later cocaine use. Alternatively, the greater impulsivity in the cocaine users is a consequence of cocaine use. Data about impulsivity at a young age are needed to disentangle the question of impulsivity as an antecedent or a consequence of drug use.

Before commenting on the specific questions that were examined, a few comments on the outcome of the factor analysis are warranted. The current two-factor model is similar to one proposed by Dawe and Loxton (2004). Their model consisted of a “Rash-spontaneous impulsivity” domain and a “Reward sensitivity/drive” domain. Their Rash-Spontaneous impulsivity domain overlaps with our Impulsive Action Factor with the exception that their Rash-spontaneous impulsivity domain included sensation seeking. We have added to their list of BIS and Eysenck impulsivity measures many of the MDMQ measures, e.g., buck passing, procrastination lack of premeditation and many UPPS measures, e.g., lack of premeditation and urgency. The positive loading of the impulsivity domain measures is combined with the negative loading of the delaying gratification domain in our Impulsive Action Factor. These differences most likely reflect that many of these measures were not available to be included in the Dawe and Loxton (2004) analysis. The present Thrill-seeking Factor shares several of the self-report measures within Dawe and Loxton’s (2004) Reward Sensitivity/Drive domain, e.g., BAS drive, BAS fun-seeking, but moves the measures of sensation seeking, e.g., UPPS – sensation seeking, total SSS score, from the Rash-spontaneous impulsivity domain to the current Thrill-seeking Factor. The current finding that some measures of reward sensitivity were related to sensation seeking and delay discounting argue that sensation and thrill seekers also discount future reinforcers more rapidly.

The decision to treat the delay-discounting questionnaire as a self-report measure allowed us to show that the data provided by this instrument is minimally correlated with the other self-report measures and provides unique information. Meda et al. (2009), using principal component analyses of data collected in 176 participants (55% female) including 31 current cocaine users, concluded that the self-report measures they used had 3 domains: Behavioral activation, e.g., BAS scales, Reward/punishment sensitivity and Impulsivity, e.g., BIS scales. In their case, as with Dawe and Loxton (2004) sensation seeking measures were included in the impulsive action or Rash-Spontaneous impulsivity scale domain. In the present dataset the BAS measures were in the sensation and thrill-seeking domain and only the BAS Drive measure loading on the Thrill-seeking Factor. The present results complement the previous studies and argue that delaying gratification, impulsive action, sensation and thrill-seeking including reward sensitivity, and delay discounting are 4 domains related to impulsive behaviors and these 4 domains are accounted for by 2 factors representing Impulsive Action and Thrill-seeking.

The first purpose of this study was to examine sex differences in impulsivity measures and factor scores in a group of cocaine users and matched controls. In contrast to expectations there were many sex differences on individual subscales in the control group, but fewer in the cocaine group. Numerous studies have failed to find differences in BIS scores between healthy male and female controls (Patton et al., 1995; Kogachi et al., 2017) or problem drinkers (Ide et al., 2017). A single impulsivity question in the NESARC (National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions) database differentiated males and females (Chamorro et al., 2012) with males and young adults being more impulsive. In the current study males had greater Thrill-seeking Factor scores, but there were no differences in Impulsive Action Factor scores.

Cross et al. (2011) performed a meta-analysis of 277 studies examining sex differences. They examined four domains related to self-report questionnaires: Reward Sensitivity assessed here with the BAS measures, Punishment Sensitivity assessed here using the Behavioral Inhibition item from the Behavioral activation/inhibition questionnaire of Carver and White (1994), Sensation Seeking assessed here using the SSS measures and the UPPS sensation seeking scale, and Effortful Control measured here by the BIS and Eysenck questionnaires. With respect to the controls, the present outcomes match the earlier meta-analysis in many ways. There were no sex effects on Reward Sensitivity, females were more punishment sensitive, males were more sensation seeking and males had less effortful control (impulsivity in current study), albeit the latter difference was small. Greater differences in individual impulsivity subscales were observed here.

The greater sex differences in the impulsivity domain in the current study may be related to the 50% unemployment level and lower BMSS level in our samples compared to studies with non-drug using samples. Male cocaine users had greater scores than female cocaine users on many of the same items as healthy controls (Eysenck venturesome, sensation seeking and reward sensitivity factor items). Female cocaine users only had greater scores on 2 DGI items (physical and social) than male cocaine users. Kogachi et al. (2017) failed to find sex differences on the BIS in a smaller sample of methamphetamine users. There were fewer differences between male and female cocaine users than expected in impulsivity measures. Sex differences in the impulsive domain vary among studies and the effects are small such that significant differences are observed in mostly large sample studies and meta-analyses of multiple studies.

Many studies have reported greater impulsivity amongst drug users but the role of sex has not been well analyzed. For example, Mahoney et al. (2015) reported that cocaine users had greater BIS and SSS scores than an age and ethnicity-matched control group (sex effects were not examined). In their review of 29 papers that assessed impulsivity in behavioral disorders, Leeman et al. (2019) concluded that greater self-reported impulsivity (using many of the impulsive scales used here) was associated with greater alcohol and drug use and high-risk sexual activity. There are few data specifically comparing male to female cocaine users or comparing female drug users to female controls on impulsivity measures. Hess et al. (2018) administered the BIS to a group of female “crack” users who were at least 20 days abstinent and a group of control females. In contrast to the present outcome, cocaine-using females had greater BIS scores than age-matched controls. Additional data on impulsivity as a function of sex and drug use are needed. Because females often escalate to problematic drug use more quickly than males (e.g., Greenfield et al., 2010; Kerridge et al., 2017; Khan et al., 2013; Schepis et al., 2011; but see Lopez-Quintero et al., 2011), we had expected more differences from matched controls for female cocaine users than male cocaine users. The finding that female cocaine users had greater Thrill-seeking Factor scores than female controls suggests that thrill seeking is an important variable in female drug use. Similarly, the finding that male cocaine users had greater Impulsive Action Factor scores than male controls suggests that impulsivity is an important factor in male drug use.

Of note female, but not male cocaine users had greater delay discounting than their sex-matched controls. Greater delay discounting in individuals who use drugs has been a hallmark of the experimental literature for decades. For example MacKillop et al. (2011) conducted a meta-analysis of 46 studies on delay discounting with over 56,000 participants and concluded that although there was great variability in effect sizes among studies, greater delay discounting was significantly related to substance use. Cocaine users (mostly male) have been repeatedly shown to discount futures rewards at a greater rate than matched controls (e.g., Coffey et al., 2003; Cox et al., 2020; Moody et al., 2016). Perhaps the high levels of unemployment (50 to 75%) in all 4 of the groups made the delay discounting measure less sensitive to drug use in the present study.

The second purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between impulsivity measures and amount of self-reported cocaine use. In the present study, cocaine users reported a wide range of cocaine use with about one third spending between $100 and $200 per week. The median amount spent per week was not different between males ($100) and females ($125). Neither scores on the impulsivity questionnaires nor the factor scores were related to cocaine use in males. In females only two individual subscales were related to cocaine use. Thus, while on average cocaine users differed from controls on many impulsivity measures and on both factor scores, contrary to expectations impulsivity was not significantly related to amount of cocaine used. The relationship between impulsivity and amount of cocaine use may require a larger sample to be quantified.

The third purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between impulsivity measures and preferred route of cocaine administration. Individuals who insufflated cocaine spent less than half as much money on cocaine each week. Only a few impulsivity measures were related to preferred route of cocaine use. Individuals who preferred to smoke cocaine had greater scores on the Impulsive Action factor while individuals who preferred to insufflate cocaine had greater scores on the Thrill-Seeking factor. This outcome contrasts with (Reed and Evans, 2016) who reported that smoked cocaine users were more impulsive than users who insufflate cocaine on several measures. In addition to impulsivity there are many other variables that might account for the small differences between the 2 groups including differences in money to buy drugs, availability of cocaine powder vs. “crack” cocaine, etc.

In the present study significant differences were readily observed between relatively large groups of individuals on impulsivity measures. For example, a difference in Impulsive Action and Thrill-seeking was observed when a group of individuals (n = 65) who spent $50/week on cocaine, i.e., individuals who preferred to insufflate cocaine, were compared to a group (n = 115) of individuals who spent $120/week on cocaine, i.e., individuals who preferred to smoke cocaine. Such outcomes were not observed in the correlations between impulsivity measures and associations between impulsivity measures and money spent on cocaine were minimal. Knowledge about an individual’s impulsivity as measured using the self-report instruments used here may only provide categorical information about vulnerability to a behavioral disorder with minimal information about the severity of the disorder. Though previous work suggests sensation and thrill seeking are unique predictors of cocaine use disorder, the current findings do not replicate that finding. We hypothesize that thrill seeking is a predictor of cocaine use onset, but not necessarily a correlate of sustained use. That is, the role for thrill seeking in cocaine use declines with long-term use and impulsive action becomes more predictive of cocaine use patterns.

Some clinical implications can be drawn from the present data. Psycho-education should be used to help clients understand impulsive action and thrill seeking and their role in cocaine use and other non-productive behavioral patterns. Acceptance-based techniques (Hayes et al., 2011) within the framework of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT) would be useful in acknowledging and accepting impulsivity as a stable trait, while encouraging behaviors that are more consistent with a client’s values. Behavioral techniques from several evidence-based therapies could be used to address delaying drug taking. Addressing distress tolerance and emotion regulation within a Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT: DBT Coach; Linehan, 2014) approach would improve a client’s ability to pre-emptively recognize internal and external cues that precede risky or impulsive behavior and take an active effort to intervene on a cognitive, behavioral or emotional level to produce a more desirable outcome (Daley and Douaihy, 2019). The utilization of simple pro-con lists (Daley and Douaihy, 2019; Grant et al., 2011) that explore the short and long-term pros and cons of engaging in a behavior versus resisting an urge or impulse to engage in that behavior would encourage clients to focus on their behavior and its consequences. Finally, the commonly used mindfulness-based therapeutic technique of urge surfing could be used to help clients recognize the transient nature of urges to engage in impulsive action while delaying engagement in the target behavior until the urge passes or reduces in intensity (Marlatt and Donovan, 2005; Prisciandaro et al., 2013). Thus, helping individuals acknowledge the role of impulsivity and thrill seeking in their behavioral choices and providing therapeutic tools to manage these urges within a broader therapeutic context will provide a supportive approach to reducing harmful behaviors (e.g., Blonigen et al., 2013; Schag et al., 2015).

In summary, 1) the correlational structure of the 8 commonly used self-report impulsivity questionnaires yielded 4 domains of self-reported impulsivity: delay discounting, delaying gratification, impulsivity, and thrill-seeking. 2) Factor analysis yielded 2 factors: Impulsive Action and Thrill-seeking. 3) Males had greater Thrill-seeking Factor scores than females within each group but there were no sex differences in Impulsive Action within each group. 4) Male cocaine users had greater Impulsive Action scores while female cocaine users had greater Thrill-seeking scores than their sex-matched controls. 5) Individuals who preferred insufflating cocaine had greater Thrill-seeking Factors and smaller Impulsive Action Factors than individuals who preferred to smoke cocaine. In conclusion, Impulsive Action and Thrill-seeking are 2 aspects of impulsivity that independently influence behavior.

Highlights.

Impulsivity domains: delay discounting, delaying gratification, impulsivity and thrill seeking

Factor analysis yielded 2 factors: Impulsive Action and Thrill-seeking

Male cocaine users had greater Impulsive Action scores than male controls

Female cocaine users had greater Thrill-seeking scores than female controls

Impulsivity levels were not predictive of current cocaine use

Acknowledgements

The assistance of Drs. Kenneth Carpenter, Gillinder Bedi and Thomas Chao is gratefully appreciated. Alex Dopp, Jessica Slonim, Payal Pandya, and Drs. Melissa Mahoney and Patrick Robke provided the clinical assessments. Benjamin Bilingsley, Tara Hoda, Yousr Shaltout and Molly Tow coordinated study activities and supervised additional assistance provided by Tanya Lalwani, Madeline Finkel and Ashley Soh.

Role of Funding Source

This research was supported by RO1 DA-035846 from The National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest

No conflict declared

References

- Ahn W-Y, Ramesh D, Moeller FG, Vassileva J, 2016. Utility of machine-learning approaches to identify behavioral markers for substance use disorders: impulsivity dimensions as predictors of current cocaine dependence. Front. Psychiatry 7, 34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel WK, Yi R, Kowal BP, Gatchalian KM, 2008. Cigarette smokers discount past and future rewards symmetrically and more than controls: is discounting a measure of impulsivity? Drug Alcohol Depend. 96(3), 256–262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair SL, Menasco MA, 2016. Gender differences in substance use across marital statuses. Int. J. Criminol. Sociol 5, 1–13 [Google Scholar]

- Blonigen DM, Timko C, Moos RH, 2013. Alcoholics Anonymous and reduced impulsivity: a novel mechanism of change. Subst. Abus 34(1), 4–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS, White TL, 1994. Behavioral inhibition, behavioral activation, and affective responses to impending reward and punishment: the BIS/BAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol 67, 319–333. [Google Scholar]

- Chamorro J, Bernardi S, Potenza MN, Grant JE, Marsh R, Wang S, Blanco C, 2012. Impulsivity in the general population: a national study. J. Psychiatr. Res 46(8), 994–1001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coffey SF, Gudleski GD, Saladin ME, Brady KT, 2003. Impulsivity and rapid discounting of delayed hypothetical rewards in cocaine-dependent individuals. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol 11(1), 18–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox DJ, Dolan SB, Johnson P, Johnson MW, 2020. Delay and probability discounting in cocaine use disorder: comprehensive examination of money, cocaine, and health outcomes using gains and losses at multiple magnitudes. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol 28(6), 724–738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross CP, Copping LT, Campbell A, 2011. Sex differences in impulsivity: a meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull 137(1), 97–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daley DC, Douaihy AB, 2019. Managing Substance Use Disorder: Practitioner Guide. Oxford University Press, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Daly M, Delaney L, Egan M, Baumeister RF, 2015. Childhood self-control and unemployment throughout the life span: evidence from two British cohort studies. Psychol. Sci 26(6), 709–723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis BA, Clinton SM, Akil H, Becker JB, 2008. The effects of novelty-seeking phenotypes and sex differences on acquisition of cocaine self-administration in selectively bred High-Responder and Low-Responder rats. Pharmacol. Biochem. Behav 90(3), 331–338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawe S, Loxton NJ, 2004. The role of impulsivity in the development of substance use and eating disorders. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev 28, 343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Wit H, 2009. Impulsivity as a determinant and consequence of drug use: a review of underlying processes. Addict. Biol 14, 22–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ersche KD, Bullmore ET, Craig KJ, Shabbir SS, Abbott S, Müller U, Ooi C, Suckling J, Barnes A, Sahakian BJ, Merlo-Pich EV, Robbins TW, 2010. Influence of compulsivity of drug abuse on dopaminergic modulation of attentional bias in stimulant dependence. Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 67(6), 632–644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenden JL, 1999. Varieties of impulsivity. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 146(4), 348–361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eysenck SBG, Pearson PR, Easting G, Allsopp JF, 1985. Age norms for impulsiveness, venturesomeness and empathy in adults. Personal. Individ. Diff 6, 613–619. [Google Scholar]

- Friendly M, 2002. Corrgrams: exploratory displays for correlation matrices. Am. Stat 56. 316–324. [Google Scholar]

- Grant JE, Donahue CB, Odlaug BL, 2011. Treating Impulse Control Disorders: A Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy Program, Therapist Guide. New York, Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greenfield SF, Back SE, Lawson K, Brady KT, 2010. Substance abuse in women. Psychiatr. Clin. North Am 33(2), 339–355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayes SC, Strosahl KD, Wilson KG, 2011. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The Process and Practice of Mindful Change. New York, Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heil SH, Johnson MW, Higgins ST, Bickel WK, 2006. Delay discounting in currently using and currently abstinent cocaine-dependent outpatients and non-drug-using matched controls. Addict. Behav 31(7), 1290–1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess A, Menezes CB, de Almeida R, 2018. Inhibitory control and impulsivity levels in women crack users. Subst. Use Misuse 53(6), 972–979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoerger M, Quirk SW, Weed NC, 2011. Development and validation of the delaying gratification inventory. Psychol. Assess 23(3), 725–738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulka LM, Vonmoos M, Preller KH, Baumgartner MR, Seifritz E, Gamma A, Quednow BB, 2015. Changes in cocaine consumption are associated with fluctuations in self-reported impulsivity and gambling decision-making. Psychol. Med 45(14), 3097–3110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ide JS, Zhornitsky S, Hu S, Zhang S, Krystal JH, Li CR, 2017. Sex differences in the interacting roles of impulsivity and positive alcohol expectancy in problem drinking: a structural brain imaging study. NeuroImage. Clin 14, 750–759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson MW, Johnson PS, Herrmann ES, Sweeney MM, 2015. Delay and probability discounting of sexual and monetary outcomes in individuals with cocaine use disorders and matched controls. PloS One 10(5), e0128641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerridge BT, Pickering R, Chou P, Saha TD, Hasin DS, 2017. DSM-5 cannabis use disorderin the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions-III: gender-specific profiles. Addict. Behav 76, 52–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan SS, Secades-Villa R, Okuda M, Wang S, Pérez-Fuentes G, Kerridge BT, Blanco C, 2013. Gender differences in cannabis use disorders: results from the National Epidemiologic Survey of Alcohol and Related Conditions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 130(1–3), 101–108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiluk BD, Babuscio TA, Nich C, Carroll KM, 2013. Smokers versus snorters: do treatment outcomes differ according to route of cocaine administration? Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol 21, 490–498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, 2004. Heroin and cocaine abusers have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than alcoholics or non-drug-using controls. Addiction 99(4), 461–471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirby KN, Petry NM, Bickel WK, 1999. Heroin addicts have higher discount rates for delayed rewards than non-drug-using controls. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen 128, 78–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kogachi S, Chang L, Alicata D, Cunningham E, Ernst T, 2017. Sex differences in impulsivity and brain morphometry in methamphetamine users. Brain Struct. Funct 222(1), 215–227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koritzky G, Yechiam E, Bukay I, Milman U, 2012. Obesity and risk taking. A male phenomenon. Appetite 59, 289–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leeman RF, Rowland B, Gebru NM, Potenza MN, 2019. Relationships among impulsive, addictive and sexual tendencies and behaviours: a systematic review of experimental and prospective studies in humans. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B. Biol. Sci 374(1766), 20180129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linehan MM, 2014. DBT Skills Training Handouts and Worksheets. New York, Guilford Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lister JJ, Ledgerwood DM, Lundahl LH, Greenwald MK, 2015. Causal pathways between impulsiveness, cocaine use consequences, and depression. Addict. Behav 41, 1–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Quintero C, Pérez de los Cobos J, Hasin DS, Okuda M, Wang S, Grant BF, Blanco C, 2011. Probability and predictors of transition from first use to dependence on nicotine, alcohol, cannabis, and cocaine: results of the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). Drug Alcohol Depend. 115(1–2), 120–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Kahler CW, 2009. Delayed reward discounting predicts treatment response for heavy drinkers receiving smoking cessation treatment. Drug Alcohol Depend. 104(3), 197–203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacKillop J, Amlung MT, Few LR, Ray LA, Sweet LH, Munafò MR, 2011. Delayed reward discounting and addictive behavior: a meta-analysis. Psychopharmacology (Berl.) 216(3), 305–321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahoney JJ, Thompson-Lake DG, Cooper K, Verrico CD, Newton TF, De La Garza R, 2015. A comparison of impulsivity, depressive symptoms, lifetime stress and sensation seeking in healthy controls versus participants with cocaine or methamphetamine use disorders. J. Psychopharmacol 29(1), 50–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mann L, Burnett P, Radford M, Ford S, 1997. The Melbourne decision making questionnaire: an instrument for measuring patterns for coping with decisional conflict. J. Behav. Decis. Mak 10(1), 1–19. [Google Scholar]

- Marlatt GA, Donovan DM, 2005. Relapse Prevention: Maintenance Strategies in the Treatment of Addictive Behaviors. New York, Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Meda SA, Stevens MC, Potenza MN, Pittman B, Gueorguieva R, Andrews MM, Thomas AD, Muska C, Hylton JL, Pearlson GD, 2009. Investigating the behavioral and self-report constructs of impulsivity domains using principal component analysis. Behav. Pharmacol 20(5–6), 390–399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendez IA, Simon NW, Hart N, Mitchell MR, Nation JR, Wellman PJ, Setlow B, 2010. Self-administered cocaine causes long-lasting increases in impulsive choice in a delay discounting task. Behav. Neurosci 124(4), 470–477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moeller FG, Dougherty DM, Barratt ES, Schmitz JM, Swann AC, Grabowski J, 2001. The impact of impulsivity on cocaine use and retention in treatment. J. Subst. Abuse Treat 21, 193–198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moody L, Franck C, Hatz L, Bickel WK, 2016. Impulsivity and polysubstance use: a systematic comparison of delay discounting in mono-, dual-, and trisubstance use. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol 24(1), 30–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patton JH, Stanford MS, Barratt ES, 1995. Factor structure of the Barratt Impulsiveness Scale. J. Clin. Psychol 51, 768–774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poling J, Kosten TR, Sofuoglu M, 2007. Treatment outcome predictors for cocaine dependence. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abuse 33, 191–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prisciandaro JJ, Myrick H, Henderson S, McRae-Clark AL, Santa Ana EJ, Saladin ME, Brady KT, 2013. Impact of DCS-facilitated cue exposure therapy on brain activation to cocaine cues in cocaine dependence. Drug Alcohol Depend. 132(1–2), 195–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed SC, Evans SM, 2016. The effects of oral d-amphetamine on impulsivity in smoked and intranasal cocaine users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 163, 141–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reimers S, Maylor E, Stewart N, Chater N, 2009. Associations between a one-shot delay discounting measure and age, income, education and real world impulsive behavior. Personal. Individ. Diff 47, 973–978. [Google Scholar]

- Ringe WK, Saine KC, Lacritz LH, Hynan LS, Cullum CM, 2002. Dyadic short forms of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale–III. Assessment 9(3), 254–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robbins TW, Gillan CM, Smith DG, de Wit S, Ersche KD, 2012. Neurocognitive endophenotypes of impulsivity and compulsivity: towards dimensional psychiatry. Trends Cogn. Sci 16(1), 81–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schag K, Leehr EJ, Martus P, Bethge W, Becker S, Zipfel S, Giel KE,2015. Impulsivity-focused group intervention to reduce binge eating episodes in patients with binge eating disorder: study protocol of the randomised controlled IMPULS trial. BMJ Open 5(12), e009445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schepis TS, Desai RA, Cavallo DA, Smith AE, McFetridge A, Liss TB, Potenza MN, Krishnan-Sarin S, 2011. Gender differences in adolescent marijuana use and associated psychosocial characteristics. J. Addict. Med 5(1), 65–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan DV, 2014. Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview for DSM-5 (MINI 7.0.0). Medical Outcome Systems, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Simon NW, Mendez IA, Setlow B, 2007. Cocaine exposure causes long-term increases in impulsive choice. Behav. Neurosci 121(3), 543–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoltenberg SF, Batien BD, Birgenheir DG (2008). Does gender moderate associations among impulsivity and health-risk behaviors? Addict. Behav 33(2), 252–265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strüber D, Lück M, Roth G, 2008. Sex, aggression and impulse control: an integrative account. Neurocase 14(1), 93–121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swann A, Bjork J, Moeller G, Dougherty D, 2002. Two models of impulsivity: relationship to personality traits and psychopathology. Biol. Psychiatry 51, 988–994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomson GH, 1935. The definition and measurement of “g” (general intelligence). J. Educ. Psychol 26(4), 241–262. [Google Scholar]

- Vonmoos M, Hulka LM, Preller KH, Jenni D, Schulz C, Baumgartner MR, Quednow BB, 2013. Differences in self-reported and behavioral measures of impulsivity in recreational and dependent cocaine users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 133, 61–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washio Y, Higgins ST, Heil SH, McKerchar TL, Badger GJ, Skelly JM, Dantona RL,2011. Delay discounting is associated with treatment response among cocaine-dependent outpatients. Exp. Clin. Psychopharmacol 19(3), 243–248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whiteside SP, Lynam D, 2001. The Five Factor Model and impulsivity: using a structural model of personality to understand impulsivity. Personal. Individ. Diff 30, 669–689. [Google Scholar]

- Zuckerman M, Eysenck S, Eysenck HJ, 1978. Sensation seeking in England and America: cross-cultural, age, and sex comparisons. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol 46, 139–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]