Abstract

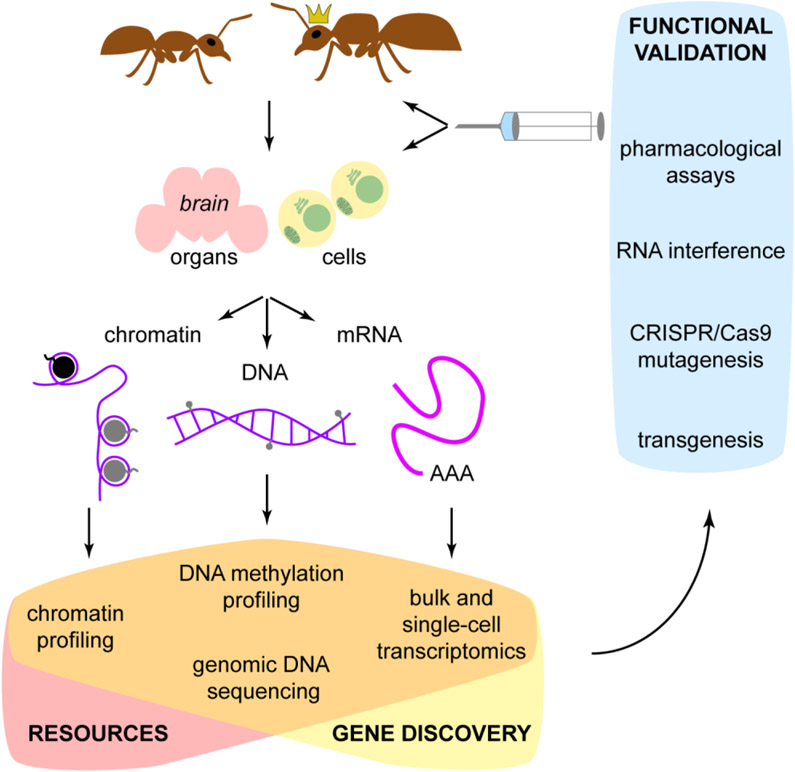

Social insects, such as ants, bees, wasps, and termites, draw biologists’ attention due to their distinctive lifestyles. As experimental systems, they provide unique opportunities to study organismal differentiation, division of labor, longevity, and the evolution of development. Ants are particularly attractive because several ant species can be propagated in the lab. However, the same lifestyle that makes social insects interesting also hampers the use of molecular genetic techniques. Here, we summarize the efforts of the ant research community to surmount these hurdles and obtain novel mechanistic insight into the biology of social insects. We review current approaches and propose novel ones involving genomics, transcriptomics, chromatin and DNA methylation profiling, RNA interference, and genome editing in ants and discuss future experimental strategies.

Keywords: Ants, single-cell sequencing, epigenetics, RNAi, CRISPR, transgenesis

Molecular biology in ants

Most studies that investigate the mechanistic detail of how cells and organisms function are performed in model species, such as yeast, Drosophila, and mice. Research on these easy-to-breed species laid the foundation of modern biology. As studies in model organisms rely on decades of knowledge acquired by thousands of labs and on vast community resources, performing similar research in non-model organisms may seem a daunting task. However, recent technological advances have provided new and improved experimental tools that can be applied to a great variety of species. Investigations in non-model organisms bring value because gene functions evolve rapidly, and studying the same process in different organisms always has potential to provide novel mechanistic insight [1]. More importantly, some species have interesting traits not present in model organisms.

Social insects, such as ants, bees, wasps, and termites, receive considerable attention due to their unique lifestyles. In some insect societies, the roles played by different individuals are so segregated and specialized that their colonies are sometimes called “superorganisms”, drawing an analogy between individuals in the colony and organs in the body. Sociality in most species relies on the existence of castes, or groups of individuals with distinct roles in the colony. In many cases, members of different castes are genetically identical, yet they display different behaviors (e.g. soldiers hunt and nurses care for the brood), physiology (e.g. queens lay eggs while other castes rarely do) and lifespan (queens live considerably longer than workers) [2]. These biological properties raise many important questions. What signaling mechanisms translate environmental cues and social context into molecular cues that specify the caste in developing larvae? How broadly do the mechanisms of cellular differentiation and fate maintenance that have been discovered in cell cultures apply to whole organisms? How are the brains organized to drive altruistic behaviors in non-reproducing members of the colony? Which mechanisms allow queens to live longer than workers while reproduction is linked to decreased lifespan in most other animals? How did sociality evolve and what selective pressure acts on the underlying genes? Ants represent a particularly attractive model to address these questions owing to their diversity and the fact that some species can be propagated in the lab indefinitely [3-6]. Here, we summarize the tools of molecular biology which have been applied to ants and suggest novel alternatives and potentially useful techniques for future research. This review is intended to serve as a primer for anyone who is interested in applying molecular techniques to ants and non-model species of insects in general.

Genome assembly and annotation

The application of most molecular biological techniques requires knowing the sequence either of the gene of interest or of the entire genome. Therefore, a genome assembly is one of the first resources that needs to be generated for a new non-model species. Conveniently, ants tend to have small-to-intermediate genome sizes: the genomes assembled to date by The Global Ant Genomics Alliance (GAGA) range from 191 Mb to 599 Mb [7]. This means that sequencing is relatively inexpensive, and genome assembly suffers from fewer computational challenges than the assembly of the large and repeat-rich genomes of some other insects [8]. Additionally, most ant species have haploid males, and sequencing a single male helps avoid assembly problems caused by heterozygosity and haplotypes [9]. There are several approaches to de novo genome assembly. First, “classical” short-read sequencing can generate an assembly that will be highly fragmented but will nevertheless recover the majority of genes [10,11]. However, many applications require better contiguity. It can be achieved by utilizing long reads (which yield longer contigs), linked reads or proximity ligation methods (which improve scaffolding), or a combination thereof. A high-quality genome assembly can be constructed using Oxford Nanopore or PacBio long reads alone, as exemplified by a mosquito genome assembled using DNA from a single individual [12]. A linked-read technology, best known by 10X Genomics' discontinued Chromium Genome platform (but see Glossary for newer, low-cost alternatives, such as stLFR and haplotagging), can also produce contiguous, haplotype-resolved genome assemblies [13-15]. In both cases, scaffold links can be further enhanced by proximity ligation methods such as Hi-C and Chicago [16,17]. Ant genome assemblies at near-chromosome resolution have been constructed by combining long reads with either stLFR or Hi-C, although using the newest PacBio long read technology (HiFi reads) alone has also yielded highly contiguous assemblies [7]. Finally, there are several ongoing massive sequencing projects that continuously generate new genome assemblies of arthropods (e.g., i5k) or ants specifically (e.g., GAGA) [7,18]. These sequencing efforts have the potential to identify the genomic basis of evolutionary innovations in ants and provide vital genomic resources for molecular biological studies in previously unexplored species. Thus, an ever-increasing number of ant genomes are being publicly released and generating a genome assembly on demand is also reasonably straightforward. The optimal benefit-cost ratio is achieved by assembling PacBio Hi-Fi or Oxford Nanopore long reads.

The most common gene annotation strategies rely on empirical evidence of gene structure provided by gene expression data, such as RNA-seq. The caveat of transcriptomics is that only a fraction of genes are detected at a given life stage in a given tissue. Therefore, best annotation accuracy is achieved when RNA-seq is performed on different developmental stages, sexes, castes, and tissues, and the data are combined [19,20]. Additionally, certain applications require accurate annotation of specific transcript features, such as alternative isoforms or untranslated regions. Long-read RNA-seq using PacBio or Oxford Nanopore, which captures whole-length transcripts, may address this and dramatically improve genome-wide analyses [21,22]. In many cases, genes can be annotated in a semi-automated fashion using the Eukaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline. It is a comprehensive annotation workflow developed by NCBI which can be run on any publicly deposited genome assembly, as long as it satisfies all the quality requirements [23].

Traditional and single-cell transcriptomics

In the absence of the ability to perform genetic screens, gene expression studies have become the main source of gene candidates for the regulators of various biological phenomena in non-model organisms [24]. Transcriptomics has some drawbacks, such as difficulty in prioritizing large lists of differentially expressed genes and limited ability to detect functionally important genes that are constitutively expressed [25]. Nevertheless, it has become an invaluable tool due to its accessibility and moderate cost. Many pioneering studies are restricted to description of gene expression profiles in different individuals or conditions, implicating specific signaling pathways in the biological process of interest [3,26-28]. Some studies are further complemented by other exploratory methods to corroborate the proposed mechanism. For example, transcriptomic profiling of the antennae, combined with molecular evolution studies, linked the emergence of complex social behaviors with the evolution of odorant receptors and odorant binding proteins [29-32]. Finally, some studies take it a step further and experimentally validate the gene candidates identified. Identification of an insulin-like peptide encoded by the only gene consistently differentially expressed between reproductive and non-reproductive individuals across seven ant species led to an experiment where insulin injected into non-reproductive individuals of the clonal raider ant Ooceraea biroi activated their ovaries [33]. Transcriptomic analyses of several tissues in the jumping ant Harpegnathos saltator implicated the neuropeptide corazonin, as well as vitellogenin, ecdysone, and juvenile hormone into the regulation of caste-specific traits. Their injection into the ants, combined in one case with RNA interference, demonstrated their effects on behavior and physiology [4,34]. Thus, gene expression studies enable discovery of candidate regulators of important biological processes, which can be further experimentally validated.

Recently, transcriptomic approaches have gained an additional dimension thanks to the boom in single-cell mRNA sequencing. It provides an unprecedented opportunity to analyze highly cell-heterogeneous tissues and organs, such as the brain, whereby gene expression changes that are masked in bulk transcriptomics can be mapped to specific cell types. Additionally, single-cell sequencing enables cell type composition analysis and inference of cell type-specific gene regulatory networks [35-37]. As these techniques are relatively new, only one study in ants has been published to date. Single-cell RNA-seq of non-visual brains in the workers and gamergates (pseudoqueens) of the jumping ant H. saltator revealed a higher proportion of ensheathing glia, which has neuroprotective properties, in the gamergate brains. Consistent with the shorter lifespan of workers, the proportion of this glial type declines with age, a phenomenon that appears to be conserved in Drosophila [38]. Given the rapid improvement in cost and performance of single-cell techniques, we expect more such studies in ants in the near future. Importantly, single-cell RNA-seq can be combined with chromatin accessibility profiling (ATAC-seq, see below), enabling a comprehensive description of the cell regulatory landscape [39]. Several important limitations remain, such as the lack of cell-type specific markers in non-model species and the loss of spatial information during single-cell library preparation. Nevertheless, techniques to transfer cell type identities from Drosophila cell atlases, as well as methods that incorporate spatial information have been developed and are being continuously improved [40-42].

Chromatin profiling

Caste-specific gene expression is associated with distinct chromatin states [43,44]. Therefore, the description of the latter has potential to identify genes differentially regulated between castes and the mechanism by which their differential expression is maintained. Chromatin profiling establishes the pattern of accessibility, describes the distribution of histone posttranslational modifications, and determines the binding of transcription factors and other DNA-interacting proteins. The most commonly used technique to profile accessible chromatin is ATAC-seq [45]. Recently published data for the pharaoh ant Monomorium pharaonis showed that the brains of different castes and sexes have distinct ATAC-seq profiles, whereby chromatin accessibility mirrors the expression level of nearby genes [46]. Future studies in ants will take advantage of the modest requirements for the amount of input chromatin, which allows ATAC-seq to be performed at a single-cell resolution [39]. ChIP-seq maps histone modifications and DNA-binding proteins. ChIP-seq for the histone H3 and its several modifications, as well as for RNA polymerase II and the acetyltransferase CBP was performed in different castes and sexes of the carpenter ant C. floridanus. These chromatin maps enabled identification of regions differentially marked between the castes, whereby gene-proximal H3K27ac displayed the strongest correlation with gene expression, and its levels strongly discriminated between castes and sexes, especially in the regions bound by CBP [44]. This study paved the way for experimental manipulation of CBP-dependent histone acetylation, which alters the behavior of major workers [47]. Most importantly, it also led to the identification of a more downstream effector CoREST, which is a direct repressor of juvenile hormone-degrading genes (and thus an indirect activator of juvenile hormone signaling) in minor workers [48]. The significance of this finding is that it described in detail the regulation of juvenile hormone signaling, a pathway that appears to have been the main evolutionary target during the emergence of sociality [49,50].

Nevertheless, ChIP-seq suffers from several drawbacks. ChIP-seq typically requires a high amount of input chromatin, which limits its use in non-model organisms, especially those species that cannot be propagated in the lab. Additionally, it requires high sequencing depth, and the assay may need considerable optimization for each sample and antibody. In contrast, recently developed techniques called cleavage under targets and release using nuclease (CUT&RUN) and cleavage under targets and tagmentation (CUT&Tag) may overcome these limitations. They utilize nuclease- or transposome-tethered antibodies that are allowed to diffuse into immobilized cells or nuclei. DNA immediately adjacent to the antibody-recognized protein is cleaved (CUT&RUN) or directly tagged by sequencing adapters (CUT&Tag) [51,52]. CUT&RUN and CUT&Tag are more straightforward than ChIP-seq, they provide better resolution, require lower sequencing depth and a considerably lower amount of input material. Importantly, CUT&Tag protocol is also compatible with single-cell approaches [53]. Therefore, these two techniques will be useful for chromatin profiling in ants in the future.

DNA methylation profiling

DNA methylation, in particular 5-methylcytosine (5mC) methylation, has a well-known role in transcriptional silencing in mammals. Therefore, it attracted considerable attention among researchers studying social insects as it could potentially serve as an additional source of genes underlying caste-specific phenotypes [43,54]. However, the real picture appears to be more nuanced in ants and bees [55,56]. Bisulfite sequencing was used to contrast the levels of DNA methylation between reproductive and non-reproductive individuals in the carpenter ant C. floridanus, the jumping ant H. saltator, the clonal raider ant O. biroi, and the South American ant Dinoponera quadriceps. Somewhat surprisingly, it identified few or no regions differentially methylated between reproductives and non-reproductives, and instead highlighted the association of DNA methylation with highly and constitutively expressed genes, as well as with constitutively included exons [57-59]. On the other hand, pharmacological manipulation of DNA methylation changed the size distribution of C. floridanus workers. The methylation level of a specific locus that controls growth, Egfr, negatively correlates with its expression level, suggesting that transcriptional silencing via DNA methylation is a plausible, albeit not universal, mechanism to regulate caste-specific gene expression [60]. A further potential function of DNA methylation was revealed by a study in the fire ant S. invicta, which showed a far greater difference in the pattern of DNA methylation between haploid and diploid males than between any diploid sexes or castes [61]. This intriguing finding suggests that DNA methylation may be involved in the regulation of gene dosage in haploid males, although the requirement for such regulation remains hypothetical. Finally, a study in the species complex of the harvester ants Pogonomyrmex barbatus/rugosus found higher levels of DNA methylation in parental species than in their hybrids, possibly owing to allele-specific methylation [62]. Together, this shows considerable differences in the potential role of DNA methylation between ants and mammals. Surveying for genes differentially methylated between castes appears to have limited potential to uncover new genes regulating caste-specific phenotypes, and the results of such studies must be interpreted with caution due to the poorly understood role of DNA methylation in ants.

Pharmacological assays

Manipulating the activity of signaling pathways and other biochemical targets via treatment with chemicals is a classical experimental technique which still finds its use today. For example, applying methoprene as a juvenile hormone analog is a well-established approach to activate juvenile hormone signaling [63]. Recently, methoprene was applied to the developing individuals of Pheidole to explore the mechanism and evolution of the worker subcaste decision [64,65]. Another example is a study in the jumping ant H. saltator where transcriptomics performed during the worker-to-pseudoqueen transition in adults implicated juvenile hormone and ecdysone signaling in the regulation of caste-specific physiology and gene expression. Injections of either methoprene or 20-hydroxyecdysone into the body and into the food helped to functionally validate this hypothesis [34]. In addition to hormones, chemical treatment is commonly used to manipulate histone acetylation machinery. The chromatin profiling of the carpenter ant C. floridanus described above and a recent study in Temnothorax rugatulus successfully used Trichostatin A and valproic acid to inhibit histone deacetylases, and C646 to inhibit histone acetylases [47,48,66]. Thus, pharmacological treatment is a straightforward way to manipulate various biochemical targets. As a disadvantage, administration of chemicals by injection, feeding or topical application provides limited control over their efficiency and distribution among target tissues. In the future, performing ex vivo experiments on organ explants or primary cell cultures may be a way to bring pharmacological assays into a more controlled biochemical setting, especially in the context of hormonal treatments which often induce a complex tissue cross-talk [67,68]. Separating different tissues will allow disentangling direct and indirect effects of the chemical, while treating isolated cells or tissues in vitro may provide a better control over drug delivery.

RNA interference

RNAi has been one of the most accessible molecular techniques for functional studies in non-model organisms [69]. Injections of double-stranded RNAs (dsRNAs) have been performed into embryos, larvae, pupae, and adults of various ant species to test the function of genes with known role in other organisms and to validate candidates identified through transcriptomics [4,47,48,64,70-72]. For instance, injection of dsRNAs against a homolog of vestigial, which controls wing development in Drosophila, into soldier-destined larvae of Pheidole hyatti leads to the reduction of their rudimentary wing discs. As a consequence, head-to-body size ratio changes, too, providing functional evidence for the role of rudimentary wing discs in allometric scaling of worker subcastes [64]. Furthermore, injection or feeding invasive ant species with dsRNAs enables exploration of possible target genes for pest management [73,74]. Altogether, RNAi is a powerful tool that has been applied to a plethora of ant species at all developmental stages. Still, the tissue specificity is difficult to achieve, and RNAi is mostly performed in ants by injection, which is highly invasive. It also shows variable efficiency, although there are cases when this may be advantageous. For example, variable or low efficiency of RNAi may uncover a range of intermediate phenotypes between castes, lending insight into caste differentiation. In an attempt to overcome some of these limitations, the delivery technologies are being continuously improved. For example, adding liposomes or nanocarriers may stabilize dsRNAs and enhance their uptake by cells [69]. Nevertheless, a real breakthrough will only come once transgenic technology is established. Expression of dsRNAs from an integrated transgene will be more consistent across cells and tissues than delivery by injection or feeding. Using tissue-specific promoters will allow targeting specific tissues, and adoption of binary expression systems (e.g. Gal4-UAS) will provide a way to fine-tune the timing and level of dsRNA expression [75].

Genetic knockouts and knock-ins

Recently, the set of functional tools to study non-model organisms has been enriched by the advent of CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing. The simplest application of CRISPR-based techniques only requires knowing the sequence of the target site and a way to deliver guide RNA (gRNA) and Cas9 to the tissue. Therefore, CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing has been used for functional genetic studies in a myriad of organisms. In contrast, in social insects, it is inherently limited by the difficulties or inability to set up genetic crosses in the lab. Yet, two studies were able to obtain stable mutant lines generated using CRISPR-Cas9 in the jumping ant H. saltator and the clonal raider ant O. biroi. Both studies targeted the gene Orco. The mutants have a defective sense of smell and exhibit aberrant social behaviors that are mediated by pheromones. Unexpectedly, they also lack the majority of olfactory sensory neurons in the antennae, and the antennal lobes of the brain are strongly reduced. This suggests that the survival of olfactory sensory neurons during development depends on their activity, similar to what is observed in mammals and opposite to the “hardwired” development in Drosophila, which yet again highlights the importance of performing functional studies in non-model species [76-78]. Recently, a proof-of-principle CRISPR-Cas9 experiment, which targeted the odorant-binding protein Gp9 and Epidermal growth factor, was also performed in the fire ant S. invicta. Although the study only examined the directly injected generation zero animals, mutations were observed at high frequency, demonstrating that efficient somatic genome editing can be achieved in species that cannot be reared in the lab [79].

Nevertheless, CRISPR-Cas9 experiments in ants remain a challenging endeavor. First, gRNA and Cas9 injections into embryos create mosaic mutants. Thus, obtaining stable mutant lines requires controlled genetic crosses, but most embryos develop into non-reproductive workers which cannot be mated. To overcome this, the two Orco studies described above were performed in species that have rather unique life cycles. H. saltator workers can be experimentally induced to become reproducing queen substitutes, called “gamergates” (Fig. 2), and O. biroi colonies consist of females, all of which reproduce parthenogenetically. Second, generation of mutants in sexual species takes a long time (although in asexual ones, such as O. biroi, homozygous mutants are obtained in the first generation). Homozygous Orco mutants in H. saltator could only be obtained in the fourth generation, which took a year and a half. Third, nurses in the colony tend to destroy injected embryos and reject the larvae that develop from them. Possible solutions include letting embryos hatch on agar plates in isolation from nurses and mixing experimental larvae with unmanipulated larvae [76,77,80]. Finally, future studies will likely need to focus on a small number of very important genes, some of which may be essential for survival, mating, or reproduction, making it difficult to obtain stable mutant lines or to analyze mutant phenotypes that manifest late in development (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. Comparison of experimental strategies to obtain stable and conditional mutants.

This figure uses H. saltator as an example but this is also applicable to other species. On the left, previously used strategy to obtain Orco mutants (see [80] for method details). Cas9 protein and gRNA are combined in vitro and then injected into embryos. The embryos are allowed to hatch on agar plates and the larvae are placed into colonies with nursing workers (not shown). All animals develop into workers. Isolation of adult workers induces transition into an egg laying queen substitute (“gamergate”). Eggs laid by unfertilized females develop into males. Genotyping is done by Sanger sequencing. In males, DNA for genotyping is extracted from a clipped wing. Females are sacrificed and genotyped after a cross. P0 and F1-F4 are parental and offspring generations, respectively. “X” stands for “crossed to”. In genotype notations, “+” is a wild-type allele, “−” is a mutant allele, and “0” underscores that males are haploid. On the right, proposed strategy to generate transgenic animals for conditional mutagenesis or other applications. Instead of Cas9-gRNA complexes, a mixture of mRNA that codes for a transposase (in this example, the piggyBac transposase) and a plasmid that contains the construct to be inserted are injected instead. Black arrowheads on the piggyBac plasmid in the upper right corner symbolize inverted terminal repeat sequences recognized by the transposase. “PBac” in the genotype notations is an integrant allele. Green eye color symbolizes the expression of Px3P::GFP as an example of a selection marker.

A simple solution is to study mosaic mutants obtained as a result of somatic mutagenesis in injected embryos instead of establishing stable lines. The frequency of somatic mutations was relatively high in the previous experiments, which confirms the feasibility of this approach [77,79]. Generating mosaics does not require the ability to mate animals in the lab, making it the only viable approach in most ant species, and it permits studying homozygous lethal mutations [81,82]. Furthermore, mosaic mutant analysis may be combined with single-cell transcriptomics akin to pooled CRISPR screens in cell cultures [83]. Another strategy is to develop a technique to generate conditional mutants in those ants that can be propagated in the lab. While it may remain limited to species with unusual life cycles (see above), and experiments in true queens may be impossible, conditional mutagenesis will nevertheless be a big step in the development of a molecular toolkit for ants. A transgenic construct that carries Cas9 and guide RNAs (gRNAs) driven by a tissue-specific or inducible promoter along with a fluorescent selection marker can be integrated into the genome using one of the transposon-based transgenic techniques widely used in other insects, such as piggyBac (Fig. 2) [84-89]. Creation of such transgenes will provide a way to control genome editing in time and space and will enable studying essential genes. Importantly, transgenes are also expressed in heterozygous state, and skipping the crosses necessary to obtain homozygous lines may considerably speed up the experiments.

To develop conditional mutagenesis, it will be first necessary to optimize the transgenesis strategy. piggyBac and its hyperactive version, as well as other transposons, such as Hermes and mariner-class transposons, have been successfully used in various insects, but the efficiency of each transposon may differ from species to species [84,85,87-90]. Thus, several strategies may need to be tried in ants simultaneously. Importantly, (semi-)random insertion of transposons into the genome means that multiple transgenic lines need to be constructed each time to compensate for possible mis-expression due to position effects [87,91]. As an alternative, CRISPR-Cas9-mediated homology-directed repair (HDR) may enable transgene integration [92,93]. Still, insertion of large fragments is inefficient in many species, limiting the use of HDR to targeted substitutions and insertions of small epitope tags. In such a case, HDR may at least be used to create ant lines suitable for PhiC31-assisted integration [91,93]. PhiC31 landing sites can be knocked-in using HDR into regions that are known or expected to be euchromatic. Ideally, such a landing site would be located in the intron of a haploinsufficient gene that produces a distinct morphological phenotype when mutated. Thus, successful integration would lead to a visible phenotype that can be used to screen for integrants.

Next, it is important to generate a construct that can be used both to test the transgenesis efficiency and as a selectable marker in subsequent transgenesis experiments. Fluorescent proteins driven by 3xP3, three binding sites for the eye selector transcription factor Pax6, have been shown to work in diverse insects, as well as crustaceans [85,86,94]. Thus, 3xP3 constructs may allow the selection of transformants by screening for fluorescence in the eye. Should the dark pigmentation of the eye conceal the fluorescent signal, the ie1 promoter can be used instead, as it drives broad expression in the body throughout development [95,96]. In the best case, the only optimization step required will be to test several fluorescent proteins, which should additionally be codon-optimized for the focal species [97]. The final step will be to select upstream regulatory regions for Cas9 and gRNA expression [89]. Identification of tissue-specific promoters will make use of tissue and cell type-specific RNA-seq data that are already available and will greatly benefit from additional ATAC-seq data [5,19,34,38]. As for inducible expression, heat-shock and Tetracycline-inducible promoters work universally in insects, albeit with varying efficiency [93,98]. In summary, establishment of transgenic tools is the next step in the development of genetic techniques in ants. In addition to conditional CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis, the same genetic reagents and the same experimental strategy will be used to perform RNAi, to create expression reporters and to apply more sophisticated techniques, such as Calcium imaging in the nervous system.

Concluding remarks

Both classical and novel approaches described above (genome assembly and annotation, bulk and single-cell transcriptomics, chromatin and DNA methylation profiling, pharmacological assay, RNA interference, and genome editing) combined with the ability to rear ants in the lab, represent a formidable toolkit to tackle the unique biology of social insects (see Outstanding questions for examples of specific experimental questions for the future). Still, the application of molecular biological tools is inherently limited by the long life cycles and social lifestyles, prompting a somewhat different approach to molecular biology in ants and other non-model species in comparison to “traditional” model organisms. As mutant or RNAi screens are virtually impossible, we predict that transcriptomics will remain the main source of candidate genes for functional studies. The explosion of single-cell techniques with their unprecedented resolution and novel statistical approaches to the inference of gene regulatory relationships has already powered the discovery of important biological regulators in Drosophila and has potential to do the same in ants [99]. When complemented by chromatin-based techniques, transcriptomics uncovers additional biological regulators providing a more comprehensive picture of the biological process in question. In the future, in vivo studies may be complemented by ex vivo experiments on isolated organs or cells and by in vitro experiments on cultured cells. These techniques may enhance the efficiency of functional manipulations and facilitate the experimental readout. Finally, establishment of transgenic techniques is the necessary next step in the development of functional tools which will enable more efficient and fine-tuned RNAi, conditional knockouts, expression reporters and Calcium imaging of neuronal activity.

Outstanding questions.

Similar to mammals, the survival of developing olfactory sensory neurons in ants appears to depend on their activity. Is this mode of development linked to sociality or is it also present in solitary hymenopterans? Would conditional Orco knockout in adults (only affecting smell and not the development of the antennae or the brain) cause the same behavioral phenotypes as the early knockout?

The neuropeptide corazonin induces hunting behavior in workers. How is this achieved? Which areas of the brain are targeted by neurons that produce corazonin and how does the activity of these regions differ between foragers and nurses?

Studies in various social insects documented differences between castes in the volume of the entire brain, or specific regions. Volumetric changes appear to even occur in adulthood, e.g. during the transition from workers to pseudoqueens. Does this simply reflect pruning or growth of processes during synaptic remodeling, or do apoptosis and neurogenesis also take place? Which cell types are affected? How is this linked to caste-specific behaviors?

How do hormonal and other cues in larvae activate the mechanisms that regulate the establishment of different chromatin states in different castes?

In social insects, queens or their equivalents exhibit elevated expression of insulin-like peptides and produce many progeny while being long-lived. This seemingly contradicts what is known for other animals in which reproduction and insulin signaling and correlates with shorter lifespan. How does insulin-like signaling selectively regulate reproduction without affecting physiological processes associated with aging? What is the contribution of different downstream branches of the insulin-like pathway(s)?

What are the targets of insulin-like peptides, juvenile hormone, and ecdysone in different tissues? How do tissues talk to each other?

Figure 1. Experimental approaches in ant biology.

See table 1 for a summary of specific experimental techniques, their advantages and disadvantages.

Table 1.

Summary of the techniques discussed.

| Class of techniques |

Technique | Published examples in ants [citations] |

Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| De novo genome sequencing | Illumina short reads | YES [11] | The least expensive | Fragmented assembly, poor recovery of low-complexity regions |

| PacBio HiFi or Oxford Nanopore long reads | YES [7] | Contiguous assembly | More expensive than short reads, high molecular weight DNA required, high error rate (Oxford Nanopore) | |

| stLFR or haplotagging linked reads | YES (stLFR) [7] | Highly contiguous assembly when used in combination with long reads, less expensive than proximity-based ligation | High molecular weight DNA required | |

| Hi-C or Chicago proximity-based ligation | YES (Hi-C) [7] | Highly contiguous assembly when used in combination with long reads | The most expensive, high molecular weight DNA required | |

| Transcriptomics | Bulk RNA-seq | YES [3,26-34] | Inexpensive, deep, analysis strategies well-established | Cell-specific signals are diluted or lost |

| Single-cell RNA-seq | YES [38] | Single-cell resolution, high statistical power to identify genes with correlated expression | Expensive, high-throughput methods (10X) result in shallow sequencing, low-throughput methods (SMART-Seq) profile low numbers of cells | |

| Chromatin profiling: accessibility | Bulk ATAC-seq | YES [46] | Less expensive, deep | Cell-specific signals are diluted or lost, high number of reads are derived from mitochondrial DNA |

| Single-cell ATAC-seq | NO | Single-cell resolution, can be combined with RNA-seq | Expensive, shallow, high number of reads are derived from mitochondrial DNA | |

| Chromatin profiling: localization | ChIP-seq | YES [44,47,48] | Golden standard, analysis strategies well-established, straightforward normalization controls | High input amount of chromatin and high sequencing depth required, the coarsest resolution, nuclei isolation required in most protocols, limited number of commercially available antibodies suitable for non-model species, custom antibodies may be expensive |

| CUT&RUN | NO | Low input amount of chromatin and moderate sequencing depth required, compatible with both nuclei and cells, the highest base-pair resolution | Limited normalization strategies, protocol longer than in CUT&Tag, limited number of commercially available antibodies suitable for non-model species, custom antibodies may be expensive | |

| CUT&Tag | NO | Low input amount of chromatin and low sequencing depth required, compatible with single-cell approaches, the fastest protocol | High number of reads are derived from mitochondrial DNA, nuclei isolation preferred, limited normalization strategies, resolution coarser than in CUT&RUN, limited number of commercially available antibodies suitable for non-model species, custom antibodies may be expensive | |

| DNA methylation | Bisulfite sequencing | YES [57-62] | Single-nucleotide resolution | C-T conversion reduces sequence complexity which may affect alignment, nucleotide polymorphisms may be missed or misidentified as methylation events |

| Localization | Immunohistochemistry | YES [33,38,64,70,76,77] | Direct and quantitative way to determine protein localization at the subcellular level | Limited number of commercially available antibodies suitable for non-model species, custom antibodies may be expensive, raising antibodies to proteins that contain hydrophobic domains may be challenging, substantial protocol optimization is required in some cases |

| “Traditional” RNA in situ hybridization | YES [25,64] | Less expensive than hybridization chain reaction, suitable for shorter (<1 kb) mRNAs | Limited or no information about the subcellular localization of the encoded protein, less sensitive than hybridization chain reaction | |

| In situ hybridization chain reaction (HCR) | YES [100] | Highly sensitive, quantitative | Limited or no information about the subcellular localization of the encoded protein, more expensive than “traditional” in situ hybridization, designing a sufficient number of probes for shorter (<1 kb) mRNAs may be impossible | |

| Pharmacological assays | Pharmacological assays | YES [34,47,48,64-66] | No knowledge about gene sequence is required | Limited number of commercially available compounds, specificity may be difficult to verify, little control over tissue distribution when injecting or feeding |

| RNA interference | Injection of double-stranded or Dicer-substrate short interfering RNAs | YES [4,48,49,64,70-72] | Fast, no genetic tools are required | Highly invasive, efficiency is frequently low, limited control over tissue distribution |

| Expression of double-stranded RNAs from an integrated transgene | NO | Possibility to control the strength, timing and tissue specificity of expression | Genetic tools need to be developed, time-consuming in sexual species with long generation time | |

| Genome editing | Stable mutant lines generated using CRISPR/Cas9 | YES [76,77] | Heritable, all cells carry the same allele | Time-consuming in sexual species with long generation time, not suitable for lethal mutations and those that cause sterility or affect mating behavior, no tissue specificity |

| Mosaic mutants generated using CRISPR/Cas9 | YES [76,77,79] | Fast, suitable for species that cannot be mated in the lab, suitable for lethal mutations and those that cause sterility or affect mating behavior | Heterogeneity within tissues may partially mask the mutant phenotype, not heritable unless the germline has been mutagenized | |

| Transgenesis via CRISPR/Cas9-based homology-directed repair | NO | Integration in pre-defined location | Time-consuming in sexual species with long generation time, integration efficiency of large inserts may be low | |

| Transposon-mediated transgenesis | NO | Less limited by insert size than homology-directed repair | Time-consuming in sexual species with long generation time, (semi-)random integration may cause transgene silencing if inserted into heterochromatin |

Highlights.

While many social insects remain genetically intractable, several ant species possess features which enable their propagation in the lab and allow mechanistic, molecular genetic research on caste-specific behaviors and physiology, developmental plasticity, and aging.

In ants and other non-model organisms, gene expression studies have become the major source of candidate genes. The recent boom in single-cell transcriptomics complemented by chromatin-based techniques further increase the power of this approach to discover regulators of various biological processes.

Historically, experimental validation of the candidate genes in ants has been done by RNAi injections. Recently, CRISPR-Cas9 mutagenesis was performed. Next, transgenic technology will allow precise genetic manipulation and enable the use of other approaches, such as imaging of neural activity.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Nikolaos Konstantinides, Yingguang Frank Chan, Hua Yan, Comzit Opachaloemphan, Long Ding, and Francisco Carmona Aldana for their comments on the manuscript and Amanda Araujo Gomes Ferreira for the feedback on the figures. B.S. was supported by the Long-Term Fellowship LT000010/2020-L from the Human Frontier Science Program.

Glossary

- High-throughput chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) and Chicago

native (Hi-C) or in vitro reconstituted (Chicago) chromatin is cross-linked, and the DNA within is fragmented, ligated, and sequenced. Physically interacting DNA fragments are recovered together.

- Single-tube long fragment reads (stLFR) and haplotagging

DNA is exposed to beads that carry transposomes, which insert unique sequencing barcodes into the DNA. Physically close DNA fragments acquire the same barcodes.

- Transposome

a complex of a transposase and a synthetic transposon that contains sequencing adapters.

- ATAC-seq

assay for transposase-accessible chromatin. Chromatin is exposed to transposomes, which insert sequencing barcodes into accessible DNA more frequently than into compacted DNA. More sequences are derived from accessible regions.

- ChIP-seq

chromatin immunoprecipitation. Chromatin is fragmented and incubated with an antibody against the protein of interest. The antibody-chromatin complexes are pulled down, DNA is eluted and sequenced to determine where the protein was bound.

- CBP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate response element-binding protein binding protein. A transcriptional coactivator and a histone acetyltransferase.

- H3K27ac

acetylated Lysine-27 of the histone H3. A histone posttranslational modification.

- CoREST

corepressor for element-1-silencing transcription factor. A transcriptional repressor.

- Egfr

epidermal growth factor receptor. A member of a signaling pathway that controls growth and development.

- Bisulfite sequencing

DNA is treated with bisulfite ions, which convert cytosines, but not 5-methylcytosines, to uracils. Treated DNA is sequenced and mapped to the genome to infer the location of 5-methylcytosines.

- RNAi

RNA interference. Endogenous Argonaute proteins interact with artificially delivered small RNAs (or longer double-stranded RNAs) and trigger the degradation of complementary mRNAs.

- CRISPR-Cas9 technology

the use of clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats-associated proteins, such as Cas9, to change DNA sequence. Cas9 binds guide RNAs that direct the protein to a complementary DNA target, which Cas9 then cleaves.

- Orco

odorant receptor co-receptor, a universal binding partner of odorant receptors in ants and some other insects.

- piggyBac

a “cut and paste” transposon flanked by two characteristic inverted tandem repeat sequences. It is randomly integrated into TTAA sites in the genome by the piggyBac transposase.

- HDR

homology-directed repair. Double-strand breaks produced by Cas9 can be repaired using homologous DNA as a template. DNA containing a custom insert flanked by sequences homologous to the ends of the double-strand break is usually co-injected with the ribonucleoprotein.

- PhiC31

a retroviral integrase that mediates precise recombination between donor DNA and genomic DNA, as long as they contain specific sequences called attB and attP.

- Pax6

paired box protein 6, a transcription factor that regulates eye development in animals.

- ie1

immediate-early gene 1 of lepidopteran nucleopolyhedroviruses. Its promoter drives ubiquitous expression in different insects.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Hakeemi MS et al. (2021) Large portion of essential genes is missed by screening either fly or beetle indicating unexpected diversity of insect gene function. bioRxiv 2021.02.03.429118, [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hölldobler B et al. (2009) The Superorganism: The Beauty, Elegance, and Strangeness of Insect Societies, W. W. Norton & Company. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schrader L et al. (2015) Sphingolipids, Transcription Factors, and Conserved Toolkit Genes: Developmental Plasticity in the Ant Cardiocondyla obscurior. Mol. Biol. Evol 32, 1474–1486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gospocic J et al. (2017) The Neuropeptide Corazonin Controls Social Behavior and Caste Identity in Ants. Cell 170, 748–759.e12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Libbrecht R et al. (2018) Clonal raider ant brain transcriptomics identifies candidate molecular mechanisms for reproductive division of labor. BMC Biol. 16, 89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pontieri L et al. (2020) From egg to adult: a developmental table of the ant Monomorium pharaonis. bioRxiv [Google Scholar]

- 7.Boomsma JJ et al. (2017) The Global Ant Genomics Alliance (GAGA). Myrmecol. News 25, 61–66 [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wu C et al. (2017) Assembling large genomes: analysis of the stick insect (Clitarchus hookeri) genome reveals a high repeat content and sex-biased genes associated with reproduction. BMC Genomics 18, 884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yahav T and Privman E (2019) A comparative analysis of methods for de novo assembly of hymenopteran genomes using either haploid or diploid samples. Sci. Rep 9, 6480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Love RR et al. (2016) Evaluation of DISCOVAR de novo using a mosquito sample for cost-effective short-read genome assembly. BMC Genomics 17, 187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Privman E et al. (2018) Positive selection on sociobiological traits in invasive fire ants. Mol. Ecol 27, 3116–3130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kingan SB et al. (2019) A High-Quality De novo Genome Assembly from a Single Mosquito Using PacBio Sequencing. Genes 10, 62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weisenfeld NI et al. (2017) Direct determination of diploid genome sequences. Genome Res. 27, 757–767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang O et al. (2019) Efficient and unique cobarcoding of second-generation sequencing reads from long DNA molecules enabling cost-effective and accurate sequencing, haplotyping, and de novo assembly. Genome Res. 29, 798–808 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meier JI et al. (2020) Haplotype tagging reveals parallel formation of hybrid races in two butterfly species. bioRxiv 2020.05.25.113688, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Korbel JO and Lee C (2013) Genome assembly and haplotyping with Hi-C. Nat. Biotechnol 31, 1099–1101 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Putnam NH et al. (2016) Chromosome-scale shotgun assembly using an in vitro method for long-range linkage. Genome Res. 26, 342–350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Robinson GE et al. (2011) Creating a buzz about insect genomes. Science 331, 1386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shields EJ et al. (2018) High-Quality Genome Assemblies Reveal Long Non-coding RNAs Expressed in Ant Brains. Cell Rep. 23, 3078–3090 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oxley PR et al. (2014) The genome of the clonal raider ant Cerapachys biroi. Curr. Biol 24, 451–458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bohn J et al. (2021) Genome assembly and annotation of the California harvester ant Pogonomyrmex californicus. G3 Genes∣Genomes∣Genetics 11, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shields E et al. (2021) Genome annotation with long RNA reads reveals new patterns of gene expression in an ant brain. bioRxiv [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Thibaud-Nissen F et al. (2013) Eukaryotic Genome Annotation Pipeline. In The NCBI Handbook [Internet]. 2nd edition National Center for Biotechnology Information (US) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Oppenheim SJ et al. (2015) We can’t all be supermodels: the value of comparative transcriptomics to the study of non-model insects. Insect Mol. Biol 24, 139–154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khila A and Abouheif E (2008) Reproductive constraint is a developmental mechanism that maintains social harmony in advanced ant societies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 105, 17884–17889 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.de Bekker C et al. (2015) Gene expression during zombie ant biting behavior reflects the complexity underlying fungal parasitic behavioral manipulation. BMC Genomics 16, 620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gruber MAM et al. (2017) Single-stranded RNA viruses infecting the invasive Argentine ant, Linepithema humile. Sci. Rep 7, 3304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okada Y et al. (2017) Social dominance alters nutrition-related gene expression immediately: transcriptomic evidence from a monomorphic queenless ant. Mol. Ecol 26, 2922–2938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhou X et al. (2012) Phylogenetic and transcriptomic analysis of chemosensory receptors in a pair of divergent ant species reveals sex-specific signatures of odor coding. PLoS Genet. 8, e1002930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McKenzie SK et al. (2016) Transcriptomics and neuroanatomy of the clonal raider ant implicate an expanded clade of odorant receptors in chemical communication. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 113, 14091–14096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hojo MK et al. (2015) Antennal RNA-sequencing analysis reveals evolutionary aspects of chemosensory proteins in the carpenter ant, Camponotus japonicus. Sci. Rep 5, 13541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pracana R et al. (2017) Fire ant social chromosomes: Differences in number, sequence and expression of odorant binding proteins. Evolution Letters 1, 199–210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chandra V et al. (2018) Social regulation of insulin signaling and the evolution of eusociality in ants. Science 361, 398–402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Opachaloemphan C et al. (2021) Early behavioral and molecular events leading to caste switching in the ant Harpegnathos. Genes Dev. DOI: 10.1101/gad.343699.120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Davie K et al. (2018) A Single-Cell Transcriptome Atlas of the Aging Drosophila Brain. Cell 174, 982–998.e20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackson CA et al. (2020) Gene regulatory network reconstruction using single-cell RNA sequencing of barcoded genotypes in diverse environments. Elife 9, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Büttner M et al. (2020) scCODA: A Bayesian model for compositional single-cell data analysis. bioRxiv 2020.12.14.422688, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sheng L et al. (2020) Social reprogramming in ants induces longevity-associated glia remodeling. Science Advances 6, eaba9869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ma S et al. (2020) Chromatin Potential Identified by Shared Single-Cell Profiling of RNA and Chromatin. Cell 183, 1103–1116.e20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lotfollahi M et al. (2020) Query to reference single-cell integration with transfer learning. bioRxiv [Google Scholar]

- 41.Butler A et al. (2018) Integrating single-cell transcriptomic data across different conditions, technologies, and species. Nat. Biotechnol 36, 411–420 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Maynard KR et al. (2021) Transcriptome-scale spatial gene expression in the human dorsolateral prefrontal cortex. Nat. Neurosci 24, 425–436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Opachaloemphan C et al. (2018) Recent Advances in Behavioral (Epi)Genetics in Eusocial Insects. Annu. Rev. Genet 52, 489–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Simola DF et al. (2013) A chromatin link to caste identity in the carpenter ant Camponotus floridanus. Genome Res. 23, 486–496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Buenrostro JD et al. (2013) Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position. Nat. Methods 10, 1213–1218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wang M et al. (2020) Chromatin accessibility and transcriptome landscapes of Monomorium pharaonis brain. Sci Data 7, 217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Simola DF et al. (2016) Epigenetic (re)programming of caste-specific behavior in the ant Camponotus floridanus. Science 351, aac6633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Glastad KM et al. (2019) Epigenetic Regulator CoREST Controls Social Behavior in Ants. Mol. Cell DOI: 10.1016/j.molcel.2019.10.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.West-Eberhard MJ (1996) Wasp societies as microcosms for the study of development and evolution. In Natural History and Evolution of Paper-Wasps (West-Eberhard MJ, T. S, ed), pp. 290–317, Oxford University Press [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jones BM et al. (2021) Convergent selection on juvenile hormone signaling is associated with the evolution of eusociality in bees. bioRxiv [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meers MP et al. (2019) Improved CUT&RUN chromatin profiling tools. Elife 8, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Kaya-Okur HS et al. (2019) CUT&Tag for efficient epigenomic profiling of small samples and single cells. Nat. Commun 10, 1930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wu SJ et al. (2021) Single-cell CUT&Tag analysis of chromatin modifications in differentiation and tumor progression. Nat. Biotechnol DOI: 10.1038/s41587-021-00865-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Yan H et al. (2015) DNA methylation in social insects: how epigenetics can control behavior and longevity. Annu. Rev. Entomol 60, 435–452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Glastad KM et al. (2017) Variation in DNA Methylation Is Not Consistently Reflected by Sociality in Hymenoptera. Genome Biol. Evol 9, 1687–1698 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Oldroyd BP and Yagound B (2021) The role of epigenetics, particularly DNA methylation, in the evolution of caste in insect societies. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci 376, 20200115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bonasio R et al. (2012) Genome-wide and caste-specific DNA methylomes of the ants Camponotus floridanus and Harpegnathos saltator. Curr. Biol 22, 1755–1764 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Patalano S et al. (2015) Molecular signatures of plastic phenotypes in two eusocial insect species with simple societies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 112, 13970–13975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Libbrecht R et al. (2016) Robust DNA Methylation in the Clonal Raider Ant Brain. Curr. Biol 26, 391–395 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Alvarado S et al. (2015) Epigenetic variation in the Egfr gene generates quantitative variation in a complex trait in ants. Nat. Commun 6, 6513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Glastad KM et al. (2014) Epigenetic inheritance and genome regulation: is DNA methylation linked to ploidy in haplodiploid insects? Proc. Biol. Sci 281,20140411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Smith CR et al. (2012) Patterns of DNA methylation in development, division of labor and hybridization in an ant with genetic caste determination. PLoS One 7, e42433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Wheeler DE and Nijhout HF (1983) Soldier determination in Pheidole bicarinata: Effect of methoprene on caste and size within castes. J. Insect Physiol 29, 847–854 [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rajakumar R et al. (2018) Social regulation of a rudimentary organ generates complex worker-caste systems in ants. Nature 562, 574–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rajakumar R et al. (2012) Ancestral developmental potential facilitates parallel evolution in ants. Science 335, 79–82 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Choppin M et al. (2021) Histone acetylation regulates the expression of genes involved in worker reproduction and lifespan in the ant Temnothorax rugatulus. Authorea Preprints DOI: 10.22541/au.161865246.65161792/v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Jimenez-Gonzalez A et al. (2018) Morphine delays neural stem cells differentiation by facilitating Nestin overexpression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Gen. Subj 1862, 474–484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ayaz D et al. (2008) Axonal injury and regeneration in the adult brain of Drosophila. J. Neurosci 28, 6010–6021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Zhu KY and Palli SR (2020) Mechanisms, Applications, and Challenges of Insect RNA Interference. Annu. Rev. Entomol 65, 293–311 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rafiqi AM et al. (2020) Origin and elaboration of a major evolutionary transition in individuality. Nature 585, 239–244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Lu H-L et al. (2009) Oocyte membrane localization of vitellogenin receptor coincides with queen flying age, and receptor silencing by RNAi disrupts egg formation in fire ant virgin queens. FEBS J. 276, 3110–3123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Moreira AC et al. (2020) Analysis of the Gene Expression and RNAi-Mediated Knockdown of Chitin Synthase from Leaf-Cutting Ant Atta sexdens. J. Braz. Chem. Soc 31, 1979–1990 [Google Scholar]

- 73.Meng J et al. (2020) Suppressing tawny crazy ant (Nylanderia fulva) by RNAi technology. Insect Sci. 27, 113–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Choi M-Y et al. (2012) Phenotypic impacts of PBAN RNA interference in an ant, Solenopsis invicta, and a moth, Helicoverpa zea. J. Insect Physiol 58, 1159–1165 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Scott JG et al. (2013) Towards the elements of successful insect RNAi. J. Insect Physiol 59, 1212–1221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Trible W et al. (2017) orco Mutagenesis Causes Loss of Antennal Lobe Glomeruli and Impaired Social Behavior in Ants. Cell 170, 727–735.e10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Yan H et al. (2017) An Engineered orco Mutation Produces Aberrant Social Behavior and Defective Neural Development in Ants. Cell 170, 736–747.e9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Jafari S et al. (2012) Combinatorial activation and repression by seven transcription factors specify Drosophila odorant receptor expression. PLoS Biol. 10, e1001280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chiu Y-K et al. (2020) Mutagenesis mediated by CRISPR/Cas9 in the red imported fire ant, Solenopsis invicta. Insectes Soc. 67, 317–326 [Google Scholar]

- 80.Sieber K et al. (2021) Embryo Injections for CRISPR-Mediated Mutagenesis in the Ant Harpegnathos saltator. J. Vis. Exp DOI: 10.3791/61930 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Perry M et al. (2016) Molecular logic behind the three-way stochastic choices that expand butterfly colour vision. Nature 535, 280–284 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Livraghi L et al. (2018) Chapter Three - CRISPR/Cas9 as the Key to Unlocking the Secrets of Butterfly Wing Pattern Development and Its Evolution. In Advances In Insect Physiology 54 (ffrench-Constant RH, ed), pp. 85–115, Academic Press [Google Scholar]

- 83.Dixit A et al. (2016) Perturb-Seq: Dissecting Molecular Circuits with Scalable Single-Cell RNA Profiling of Pooled Genetic Screens. Cell 167, 1853–1866.e17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Schulte C et al. (2014) Highly efficient integration and expression of piggyBac-derived cassettes in the honeybee (Apis mellifera). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111, 9003–9008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Labbé GMC et al. (2010) piggybac- and PhiC31-mediated genetic transformation of the Asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus (Skuse). PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis 4, e788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Berghammer AJ et al. (1999) A universal marker for transgenic insects. Nature 402, 370–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fraser MJ Jr (2012) Insect transgenesis: current applications and future prospects. Annu. Rev. Entomol 57, 267–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Ben-Shahar Y (2014) A piggyBac route to transgenic honeybees. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 111, 8708–8709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Port F et al. (2020) A large-scale resource for tissue-specific CRISPR mutagenesis in Drosophila. Elife 9, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Eckermann KN et al. (2018) Hyperactive piggyBac transposase improves transformation efficiency in diverse insect species. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol 98, 16–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Markstein M et al. (2008) Exploiting position effects and the gypsy retrovirus insulator to engineer precisely expressed transgenes. Nat. Genet 40, 476–483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gratz SJ et al. (2014) Highly specific and efficient CRISPR/Cas9-catalyzed homology-directed repair in Drosophila. Genetics 196, 961–971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Gratz SJ et al. (2013) Genome engineering of Drosophila with the CRISPR RNA-guided Cas9 nuclease. Genetics 194, 1029–1035 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Pavlopoulos A and Averof M (2005) Establishing genetic transformation for comparative developmental studies in the crustacean Parhyale hawaiensis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A 102, 7888–7893 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Masumoto M et al. (2012) A Baculovirus immediate-early gene, ie1, promoter drives efficient expression of a transgene in both Drosophila melanogaster and Bombyx mori. PLoS One 7, e49323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Suzuki MG et al. (2003) Analysis of the biological functions of a doublesex homologue in Bombyx mori. Dev. Genes Evol 213, 345–354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Han Z et al. (2020) Improving Transgenesis Efficiency and CRISPR-Associated Tools Through Codon Optimization and Native Intron Addition in Pristionchus Nematodes. Genetics 216, 947–956 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lycett GJ et al. (2004) Conditional expression in the malaria mosquito Anopheles stephensi with Tet-On and Tet-Off systems. Genetics 167, 1781–1790 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Konstantinides N et al. (2018) Phenotypic Convergence: Distinct Transcription Factors Regulate Common Terminal Features. Cell 174, 622–635.e13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Nagel M et al. (2020) The gene expression network regulating queen brain remodeling after insemination and its parallel use in ants with reproductive workers. Sci Adv 6, [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]