Abstract

BACKGROUND:

Undisclosed antiretroviral drug (ARV) use among blood donors who tested HIV antibody positive, but RNA negative, was previously described by our group. Undisclosed ARV use represents a risk to blood transfusion safety. We assessed the prevalence of and associations with undisclosed ARV use among HIV-positive donors who donated during 2017.

STUDY DESIGN AND METHODS:

SANBS blood donors are screened by self-administered questionnaire, semi-structured interview and individual donation antibody and nucleic acid amplification testing for HIV. Stored samples from HIV-positive donations were tested for ARV and characterised as recent/longstanding using lag avidity testing.

RESULTS:

Of the 1462 HIV-positive donations in 2017, 1250 had plasma available for testing of which 122 (9.8%) tested positive for ARV. Undisclosed ARV use did not differ by gender (p=0.205) or ethnicity (p=0.505) but did differ by age category (p<0.0001), donor (p<0.0001) and clinic type (p=0.012) home province (p= 0.01) and recency (p<0.0001). Multivariable logistic regression found older age (aOR 3.73, 95% CI 1.98–7.04 for donors >40 compared to those <21), first-time donation (aOR 5.24; 95%CI 2.48–11.11) and donation in a high HIV-prevalence province (aOR 9.10; 95%CI 2.70–30.72) compared to Northern Rural provinces to be independently associated with undisclosed ARV use.

DISCUSSION:

Almost 1 in 10 HIV-positive blood donors neglected to disclose their HIV status and ARV use. Demographic characteristics of donors with undisclosed ARV use differed from those noted in other study. Underlying motivations for nondisclosure among blood donors remains unclear and may differ from those in other populations with significant undisclosed ARV use.

Keywords: HIV, anti-retroviral agents, disclosure, prevalence, blood donors, South Africa

INTRODUCTION

A safe, sustainable blood supply remains an essential pillar of medical care.1 Although only about 0.6% of the South African population receives transfusions annually2, the blood donor population is less than the WHO’s recommended 1%,3 therefore, meeting the local demand for blood products is challenging. Furthermore, South Africa has the largest HIV epidemic in the world,4 which hampers the recruitment of sufficient low-risk blood donors to provide for the country’s blood demand. Blood donor selection programs and pre-donation risk screening by questionnaire resulted in HIV prevalence among first-time donors of 1.14% even though >18% of the population aged 15–49, the target age group for blood donors, is HIV positive.5,6 Despite this relative success, the continued high residual risk of HIV transmission prompted implementation of highly sensitive individual donation nucleic acid amplification testing (ID-NAT) for HIV and Hepatitis C (HCV) RNA as well as Hepatitis B (HBV) DNA in 2005.7 The implementation of ID-NAT has allowed the recognition of acute HIV infections (RNA+/HIV antibody (Ab)-) and presumed HIV elite controllers, namely those who are Ab+ but RNA- due to inherent immunologic control of the virus. Such categorization of HIV infections is important for estimation of incidence and valuable for research.

While enrolling participants into a study of HIV elite controllers, we received anecdotal reports that some of these donors were previously diagnosed HIV-positive, taking concurrent anti-retroviral drugs (ARV) and presented to donate blood without disclosing their HIV status or ARV use. We conducted a study of ARV drug assays on stored plasma and found a high proportion (66.4%) of ARV use among presumed EC.8 This study suggests that blood donors with known HIV status and concurrent ARV use (HIV+/ARV+) presenting to donate blood pose a new and growing threat to the safety of the country’s blood supply as early initiation of ARV (current public health policy in SA (Ref)) may reduce HIV RNA and Ab levels.9–11 While the likelihood of occurrence and potential number of such instances are currently small, the impact of the community trust in the blood supply may be significant.

The failure by presumed EC to disclose ARV use raises broader research questions regarding the prevalence among the entire blood donor pool of persons previously diagnosed with HIV and taking ARV. Given the limits of blood donation testing sensitivity, potential sero-reversion with early ART initiation and the possibility of human error, all of which could lead to transfusion-transmitted infection, there is urgency to understand the extent of blood donation by this population and investigate interventions to reduce it. In this study, we assessed the prevalence of and demographic (age, sex, ethnicity, donor type and geographical location) correlates with undisclosed ARV use among HIV-positive donors who donated at the South African National Blood Service (SANBS) during 2017. We hypothesised that undisclosed ARV use will be lower in males, younger age and in recent and longstanding HIV cases compared to potential EC.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study design, setting and participants:

We performed a cross-sectional study of the prevalence of undisclosed ARV use among donors who tested HIV positive after donating at a SANBS donor centre during 2017. SANBS annually collects about 830,000 whole blood donations from voluntary, non-remunerated donors in eight of the nine South African provinces. Blood is collected at both fixed-site as well as mobile blood drives; the latter includes high school blood drives as the minimum age for donation in South Africa is 16 years. SANBS donors complete a self-administered questionnaire, which includes questions on HIV status and ARV use. Trained staff review donor responses; donors who disclose HIV risk factors and/or positive HIV status and/or ARV use are excluded from donation. Donor demographic and donation history data are captured and stored in a database on a secure server. Two specimens are collected from the donor at the time of donation for HIV serologic and ID-NAT which are performed on all blood donations. Frozen plasma aliquots of donors who test HIV-positive are stored at −20°C. All HIV-positive donors who donated during 2017 and for whom plasma aliquots were available for ARV assays were included in the study.

Laboratory assays:

Serological assays for HIV antibodies (Ab) were performed in parallel with multi-marker ID-NAT. The Abbott Prism HIV 1/2® (Abbott Diagnostics, Delkenheim, Germany) was used to screen for anti-HIV 1/2 Ab; specimens with reactive test results were retested in duplicate using the same assay and serology was deemed repeat reactive if either one of the replicates was reactive. In parallel, the Ultrio Elite® multimarker probe assay (Grifols Diagnostics, Barcelona, Spain) on the Procleix Panther® platform was used to screen for HIV RNA, HCV RNA and HBV DNA. Specimens with reactive test results were repeated in duplicate using the Ultrio Elite® multimarker assay as well as individually with the discriminatory probe assays for HIV, Hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV) to determine which virus was reacting. ID-NAT was deemed repeat reactive if any of the repeat tests were positive.

Donations were classified as HIV positive if HIV ID-NAT and/or serology and immunoblot tests were positive. Based on the combination of their NAT and serology result, HIV-positive donations were classified as RNA+/Ab-, RNA-/Ab+ or RNA+/Ab+. The Bio-Rad Geenius® HIV 1/2 immunoblot assay was performed to confirm and differentiate between HIV 1 and 2 in RNA-/Ab+ donation; donations were classified as from potential elite controllers if the supplemental immunoblot assay confirmed HIV-1 infection. Donations for whom the HIV NAT was reactive and serology negative (RNA+/Ab-) were requested to provide a follow up sample to check for seroconversion. Where no follow up occurred the results of multiple replicate tests from the original plasma bag were used to classify the donation as an acute HIV infection. Donations that were RNA+/Ab+ was classified as concordant positive HIV infections.

All donations found to be Ab+ (RNA+/Ab+; RNA-/Ab+) and for which plasma was available for testing, were further classified as being a recent or longstanding HIV infection using the Sedia® HIV-1 LAg-Avidity EIA test (Sedia Biosciences Corporation, Portland, Oregon, USA), a limiting antigen avidity (LAg) test. This assay has a mean duration of recency (MDRI) of 195 (95% CI: 168–222) days at a normalized optical density (ODn) <1.5 recency/longstanding threshold.12

Stored plasma aliquots of HIV-positive donations were sent for batch ARV testing at the Division of Clinical Pharmacology laboratory, University of Cape Town. A validated, high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry assay was used for the qualitative determination of nevirapine, efavirenz, lopinavir and atazanavir; this drug combination was selected to detect the vast majority of antiretroviral regimens in use in South Africa during the study period.13,14 The samples were processed with a protein precipitation extraction method. Deuterated internal standards were used for each analyte. The extraction procedure was followed by liquid chromatographic separation using an Atlantis T3® (3 μm, 2.1 mm x 100 mm) analytical column. An AB Sciex API 4000® mass spectrometer at unit resolution in the multiple reaction-monitoring mode was used to monitor the transition of the protonated precursor ions m/z 705.6, 316.0, 629.6, and 267.1 to the product ions m/z 168.2, 243.9, 447.3, and 226.0 for atazanavir, efavirenz, lopinavir, and nevirapine respectively. Electron Spray Ionisation was used for ion production. The validated cut-off concentration for all four analytes was 0.02 μg/mL.

Definitions:

Donors are classified as first-time if they have never donated a unit of blood before, repeat if they have donated at least one unit in the 12 months preceding the index donation and lapsed if they donated previously but not in the 12 months preceding the index donation. Recency category “unknown” refers to donors for whom no LAg test result is available.

Statistical analysis:

We estimated that stored plasma samples of 1350 HIV-positive donors would be available for ARV testing. Given this sample size, we would have adequate precision to detect ARV prevalence ranging from 5% (95% CI: 4.0, 6.4%) to 20% (95% CI: 17.9, 22.3%). Donor demographic and donation history characteristics were summarised using descriptive statistics. Chi-square tests were used to assess the differences in the frequencies of undisclosed ARV use by donor demographic and donation history factors. Multivariable logistic regression models for factors associated with undisclosed ARV used were then developed. Variables were first evaluated separately in unadjusted models. After assessing the data for multi-collinearity, a variable-inclusive approach was used to develop adjusted models. All variables with a significance level p<0.1 in the bivariate analysis were included in the model. All statistical analyses were performed using STATA SE software (StataCorp. 2019. Stata Statistical Software: Release 16. College Station, TX: StataCorp LLC).

Ethical considerations:

All blood donors consented to HIV testing and the use of their blood and data for research aimed at improving the safety of the country’s blood supply at the time of donation. Ethics approval for this study was obtained from the SANBS and University of Cape Town Human Research Ethics Committees as well as the University of California San Francisco Institutional Review Board, which included a waiver for individual informed consent.

RESULTS

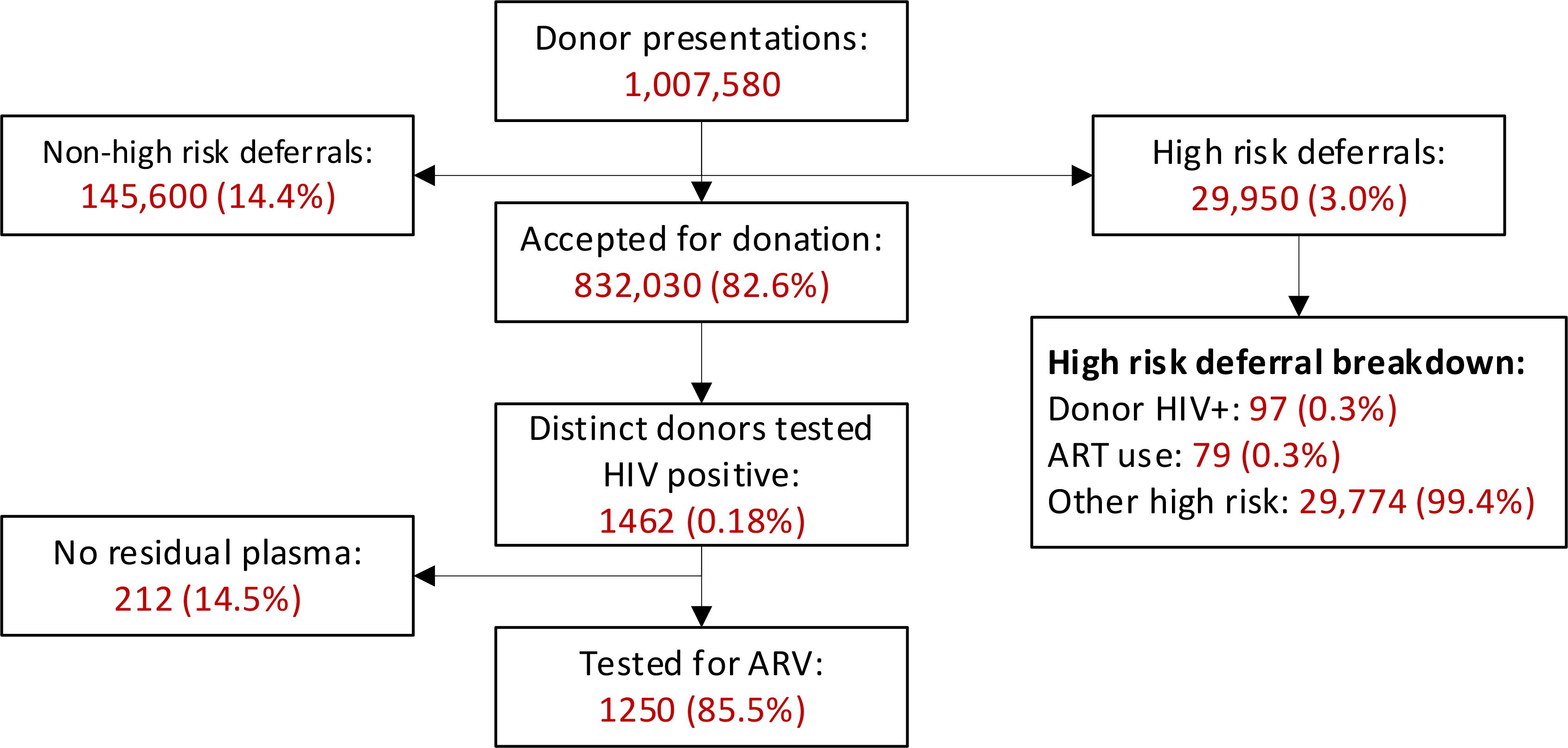

Of the 1,007,580 presentations for blood donation at SANBS donor centres during 2017, 3% resulted in deferral for high HIV risk exposures including self-reported ARV use (Figure 1). Of the 1462 (0.18%) donations that tested HIV positive (all from unique donors), 1250 (85.5%) had frozen aliquots of plasma available for ARV testing. The demographic distribution of donors for whom no frozen aliquots were available did not differ significantly from those for whom aliquots were available. The baseline characteristics of the 1250 donors included in the analysis are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1:

Schematic illustration of donor presentations, deferrals, HIV status and sample availability for HIV testing at SANBS during 2017.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the 1250 HIV-positive donors by undisclosed ARV status.

| ARV Negative | ARV Positive | Total | P-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Total | 1128 | 90.2 | 122 | 9.8 | 1250 | |

| Gender | 0.205 | |||||

| Female | 808 | 89.6 | 94 | 10.4 | 902 | |

| Male | 320 | 92.0 | 28 | 8.0 | 348 | |

| Ethnicity | 0.505 | |||||

| Asian/Indian | 10 | 90.9 | 1 | 9.1 | 11 | |

| Black | 1021 | 90.2 | 111 | 9.8 | 1132 | |

| Coloured | 30 | 85.7 | 5 | 14.3 | 35 | |

| Unknown | 29 | 87.9 | 4 | 12.1 | 33 | |

| White | 38 | 97.4 | 1 | 2.6 | 39 | |

| Age Cat | <0.0001 | |||||

| <21 | 290 | 93.2 | 21 | 6.8 | 311 | |

| 21 – 30 | 479 | 93.2 | 35 | 6.8 | 514 | |

| 31 – 40 | 226 | 85.3 | 39 | 14.7 | 265 | |

| >40 | 133 | 83.1 | 27 | 16.9 | 160 | |

| Donor Type | <0.0001 | |||||

| First-time | 605 | 85.7 | 101 | 14.3 | 706 | |

| Lapsed* | 250 | 95.1 | 13 | 4.9 | 263 | |

| Repeat | 273 | 97.2 | 8 | 2.8 | 281 | |

| Clinic Type | 0.012 | |||||

| Fixed | 238 | 94.4 | 14 | 5.6 | 252 | |

| Mobile | 890 | 89.2 | 108 | 10.8 | 998 | |

| Home Province | 0.010 | |||||

| Eastern Cape | 100 | 91.7 | 9 | 8.3 | 109 | |

| Free State | 94 | 89.5 | 11 | 10.5 | 105 | |

| Gauteng | 406 | 91.2 | 39 | 8.8 | 445 | |

| KwaZulu Natal | 199 | 85.0 | 35 | 15.0 | 234 | |

| Limpopo | 65 | 97.0 | 2 | 3.0 | 67 | |

| Mpumalanga | 196 | 88.7 | 25 | 11.3 | 221 | |

| North West | 58 | 100.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 58 | |

| Northern Cape | 10 | 90.9 | 1 | 9.1 | 11 | |

Lapsed donors: previous donation was more than 12-months before the index donation.

ARVs were detected in 122 (9.8%) of tested HIV positive donations. Among the 122 donors with undisclosed ARV use, most (94.3%) tested positive for efavirenz while none tested positive for zidovudine. No participant tested positive for more than one drug (data not shown). There was no difference in undisclosed ARV use by gender or ethnicity (Table 1). ARV prevalence increased significantly (p<0.0001) with increasing age, was highest among first-time donors (14.3%, p<0.0001) and those donating at mobile blood drives (10.8%, p<0.0001). The distribution of undisclosed ARV use differed significantly (p=0.010) by home province of the donors, with the highest prevalence in KwaZulu Natal, Mpumalanga and the Free State. ARV use differed significantly by HIV diagnostic category (p <0.0001), with the highest prevalence of 68/80, (85.0%) among the RNA-/Ab+ donors and no ARV detected in the RNA+/Ab- group (Table 2). Among the 1188 HIV Ab+ donors (both RNA- and RNA+ groups), 1153 (97.1%) had samples available for LAg testing of whom 347 (30.1%) tested LAg recent. Undisclosed ARV use prevalence were similar among those who tested LAg Recent (9.8%) and those who tested LAg longstanding (9.2%).

Table 2.

HIV testing characteristics of the 1250 participant by ARV status

| ARV Negative | ARV Positive | Total | P-Value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |||

| Total | 1128 | 90.2 | 122 | 9.8 | 1250 | |

| Diagnostic category | <0.0001 | |||||

| RNA+/Ab− | 62 | 100 | 0 | 0 | 62 | |

| RNA−/Ab+ | 12 | 15.0 | 68 | 85.0 | 80 | |

| RNA+/Ab+: | 1054 | 95.1 | 54 | 4.9 | 1108 | |

| Recency category* | 1066 | 89.7 | 122 | 10.3 | 1188 | |

| Longstanding** | 732 | 90.8 | 74 | 9.2 | 806 | <0.0001 |

| Recent~ | 313 | 90.2 | 34 | 9.8 | 347 | |

| Not Tested | 21 | 60.0 | 14 | 40.0 | 35 | |

LAg testing performed on Ab+ samples only

Estimated MDRI of ≤195 days

Estimated MDRI of > 195 days

A multivariable logistic regression model of factors associated with undisclosed ARV use are shown in Table 3. Factors independently associated with undisclosed ARV use were increasing age (aOR 3.73; 95%CI 1.98–7.04) in donors >40 compared to donors younger than 21, first-time donors (compared to repeat donors; aOR 5.24; 95%CI 2.48–11.11) and provinces with a high HIV burden (highest odds in KwaZulu Natal; aOR 9.10; 95%CI 2.70–30.72). There was a non-significant trend of higher undisclosed ARV use among donors donating at mobile blood drives compared to those who donated at fixed sites (OR: 1.75; 95%CI 0.95 – 3.21).

Table 3.

Multivariable model of factors associated with undisclosed ARV use among HIV-positive blood donors.

| Bivariate Analysis | Multivariable Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reference Group | OR* | 95% CI** | aOR# | 95% CI | ||

| Gender | ||||||

| Female | 1.33 | 0.86 | 2.07 | - | ||

| Male | Reference | |||||

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Asian/Indian | 0.92 | 0.12 | 7.25 | - | ||

| Black | Reference | . | . | |||

| Coloured | 1.53 | 0.58 | 4.03 | |||

| Unknown | 1.27 | 0.44 | 3.68 | |||

| White | 0.24 | 0.03 | 1.78 | |||

| Age Category | ||||||

| <21 | Reference | Reference | ||||

| 21–30 | 1.01 | 0.58 | 1.767 | 1.52 | 0.85 | 2.73 |

| 31–40 | 2.38 | 1.37 | 4.17 | 3.22 | 1.80 | 5.77 |

| >40 | 2.80 | 1.53 | 5.14 | 3.73 | 1.98 | 7.04 |

| Donor Type | ||||||

| Repeat | Reference | Reference | ||||

| First-time | 5.70 | 2.74 | 5.24 | 2.48 | 11.11 | |

| Lapsed~ | 1.77 | 0.72 | 1.49 | 0.60 | 3.70 | |

| Clinic Type | ||||||

| Fixed | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Mobile | 2.06 | 1.16 | 3.67 | 1.75 | 0.95 | 3.21 |

| Home Province | ||||||

| Northern Rural## | Reference | Reference | ||||

| Eastern Cape | 3.99 | 1.05 | 15.12 | 4.63 | 1.19 | 17.95 |

| Free State | 5.19 | 1.41 | 19.11 | 6.44 | 1.71 | 24.29 |

| Gauteng | 4.26 | 1.30 | 14.01 | 4.12 | 1.24 | 13.73 |

| KwaZulu Natal | 7.80 | 2.35 | 25.87 | 9.10 | 2.70 | 30.72 |

| Mpumalanga | 5.66 | 1.67 | 19.11 | 5.48 | 1.60 | 18.80 |

Odds ratio

Confidence interval

Adjusted odds ratio

Limpopo, North West, Northern Cape

Lapsed donors: previous donation was more than 12-months before the index donation.

DISCUSSION

We confirmed that a substantial proportion of HIV positive, prospective South African blood donors had undisclosed ARV use. The overall prevalence of undisclosed ARV use was 9.8% with no significant difference by gender or ethnicity. Undisclosed ARV use was high among donors found to be HIV RNA-/Ab+, a phenotype likely associated with their ARV intake and previously described as “false elite controllers”.8 Factors independently associated with undisclosed ARV use were increasing age, first-time donor status, donation in provinces in South Africa with the highest HIV burden15.

Failure to disclose ARV use within clinical or research settings has been previously demonstrated.16–18 Failure to disclose health information, even under direct questioning is common, with 10.4% to 15.5% of patients not disclosing medication use for a variety of conditions to their attending doctor.19 Several national and community household surveys in Africa reported varying rates of undisclosed ARV use among both those who self-disclose as well as among those who deny HIV-positive health status.16,20–24 In addition, studies among high-risk populations, such as men-who-have-sex-with-men (MSM) communities18 and those enrolled in the HIV Prevention Trials Network (HPTN) 052 study17, demonstrated high rates of undisclosed ARV. Undisclosed ARV use ranged from 2.2% (South Africa) to 44.4% (Malawi) among persons enrolled in HPTN 052, to as high as 49% among HIV-positive MSM who self-reported an HIV-negative health status.

We found an association between undisclosed ARV use and increasing age, first-time donation status, and residence in South African provinces with highest HIV prevalence. Studies investigating determinants of undisclosed ARV use have been conducted in a variety of settings, including household surveys, HIV vaccine trials, and high-risk populations, and have disparate results in relation to age, education or wealth levels, but consistently found no association with gender, which we also found.8,16–18,20–22 Neither HPTN 05217 nor HPTN 07525 demonstrated associations with age, but did show local as well as between-country regional differences. Household and community surveys generally reported younger age to be associated with greater odds of undisclosed ARV use, but had disparate results in terms of wealth and education.16,20,21,23,24 By contrast, undisclosed ARV use and HIV status were associated with older age among American MSM.18 These disparate results may suggest differing behavioural motivations for undisclosed ARV use among different populations.

Our study confirmed the high proportion of undisclosed ARV use among RNA-/Ab+ donors noted by Sykes et al8 The proportion undisclosed ARV use among RNA-/Ab+ donors in our study period (2017) was 85% compared to the 76.1% reported by Sykes et al for 2016; and may be related to the increasing ARV coverage in South Africa.26,27 Over this study period, Sykes et al found a temporal increase in the proportion of HIV-positive blood donors who were RNA-/Ab+ and within this group, undisclosed ARV use increased from 38.5% in 2010 to 76.1% in 2016. Similar high rates of undisclosed ARV use have been reported among presumed ARV naïve HIV-positive persons who had suppressed viral loads, particularly in settings involving HIV treatment studies.17 A US study investigating the factors associated with patient nondisclosure of medically relevant information found that concerns about being judged, lectured or embarrassed to be independently associated with nondisclosure.19 In relation to blood donors, feelings of being judged or embarrassed or potentially believing that HIV-positive donors with undetectable viral loads should be able to donate may similarly be reasons for not disclosing their HIV status and ARV use. The higher odds of undisclosed ARV use at mobile blood drives may be indicative of a relative lack of privacy at these settings which potentially creates a barrier to disclosed HIV status and ARV use. Potential test seeking behaviour either to confirm HIV status or efficacy of treatment in controlling the virus may also be motivating non-disclosure.

Despite similar prevalence of undisclosed ARV use among HIV-positive LAg recent (9.8%) and LAg longstanding donor, these data may conceal “false” recency test due to prolonged ARV use. Studies have shown that prolonged ARV use affects most tests, including the LAg avidity test, aimed at determining recency of HIV infection, resulting in over-estimation of recent infections.28–30 The false-recent rate of these tests range from 50% to 76% among persons on ARV, which more likely explains the high proportion (34 of 347) of undisclosed ARV use among donors classified as having “recent infection”.28 Failed pre-exposure prophylaxis and early ART initiation are associated with delayed seroconversion and in some instances with sero-reversion.9,31 Rapid initiation of ART in persons with recently acquired HIV could therefore result in failure to identify donors with suppressed VL and delayed or reversed seroconversion with current blood banking testing algorithms.32 Vermeulen et al reported a 2% probability of transfusion transmitted HIV infection from a red blood cell product donated by donors who are RNA-/Ab+. This finding would suggest that blood products donated by HIV-positive donors who sero-reverted or who failed to seroconvert due to very early ART initiation, would likely have a similar probability of transmitting HIV to recipients. While the absolute risk of transmission of HIV through a blood transfusion remains relatively small, the effect on the public’s trust may be significant. The impact of the international outcry of what was considered the failure of blood services to protect blood transfusion recipients from HIV and HCV infections during the 1980’s33, still affects existing and potential blood donor perception of the risks involved in donating blood, with >5% of both groups citing risk of “contamination” as a deterrent to blood donation.34 Furthermore, the perceived incidence of transfusion transmissible infections was 13.5% among patients surveyed in an academic hospital in Germany with 38% of those surveyed having a significant risk perception about possible transfusion transmissible infections.35

The 9.8% prevalence of undisclosed ARV use among South African blood donors is alarming and has implications for blood transfusion safety. The higher prevalence of non-disclosure among first-time donors was not unexpected since they had not been previously exposed to the blood service’s behavioural screening. However, the non-disclosure among repeat and lapsed donors is more alarming because it indicates a failure of repeated exposures to the SANBS donor self-assessment questionnaire and one-on-one interview procedure to identify HIV-positive donors on ARV.

Our study has limitations. First, no samples were available for ARV testing from 14.5% of HIV-positive donations. While some plasma bags were destroyed due to leakage and other operational factors, the majority of these was discarded following failure of a freezer at one of the two SANBS testing sites, which may affect some of the geographic sub-analysis as most of the discarded units were from two geographical areas. Second, due to the short half-life of some ARV drugs our testing algorithm may have missed donors on ARV who had interrupted therapy in the days prior to donation, which may result in underestimation of undisclosed ARV use. We only tested for four of the most commonly prescribed ARV in South Africa (nevirapine, efavirenz, lopinavir and zidovudine). However, at the time, efavirenz was standard in the three-drug fixed dose combination therapy prescribed as first-line therapy for the majority of adults diagnosed with HIV in South Africa and zidovudine was a key component of second-line therapy.13 Third, we also did not test for tenofovir, which may have missed donors on pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). At the time, though, PrEP was not yet widely available in South Africa and unlikely to have materially affected the overall results of this investigation,

CONCLUSION

We confirmed that almost 1 in 10 HIV positive blood donors in South Africa did not disclose their known HIV status and ARV use, likely an unintended consequence of the massive national ART rollout. Potential for sero-reversion and non-seroconversion with early ART or delayed seroconversion with PrEP will confirm increased potential risk to blood safety. While the absolute number of cases is currently still small, the impact of even one case of transfusion transmitted HIV by a blood donor who failed to disclose their HIV status and ARV use, may have a significant impact on the trust of both the donor and recipient communities. While we identified a number of factors associated with undisclosed ARV use among blood donors, the underlying cause and motivation remains unclear and further research is required to better understand this behaviour. Our research may help increase awareness of this phenomenon and help inform blood safety strategies globally, in particular in other high HIV prevalence countries with large-scale ARV availability.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge the support from the following principal investigators (PI’s), committee chairs and program staff who were responsible for the following aspects of the REDS-III South Africa program: a) Field sites: Edward L. Murphy (PI, UCSF) and Ute Jentsch (PI, South African National Blood Service); b) Data Coordinating Center: Donald Brambilla and Marian Sullivan (co-PI’s RTI International); c) Central Laboratory: Michael P. Busch (PI, Vitalant Research Institute); d) Steering Committee and Publications Committee chairs: Steven Kleinman and Roger Dodd NHLBI: Kelli Malkin and Simone Glynn; e) SANBS field staff: Cynthia Nyoni, Daphne Mohapi, Debbie Strydom; Wendy Ntaka and Cecilia Nomsobo; f) SANBS data analytics staff: Ronel Swanevelder and Tinus Brits

FUNDING:

This work was supported by research contracts from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) of the National Institutes of Health for the Recipient Epidemiology and Donor Evaluation Study-III International program: HHSN268201100009I (to UCSF and the South African National Blood Service), HHSN268201100002I (to RTI International) and HHSN2682011-00001I (to Vitalant Research Institute). KvdB, ELM and VL were also supported by NIH Fogarty International Center training grant 1D43-TW010345.

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST:

The authors certify that they have no affiliations with or involvement in any organization or entity with any financial interest (such as honoraria, educational grants, participation in speakers’ bureaus, membership, employment, consultancies, stock ownership, or other equity interest; and expert testimony or patent-licensing arrangements), or non-financial interest (such as personal or professional relationships, affiliations, knowledge or beliefs) in the subject matter or materials discussed in this manuscript.

REFERRENCES

- 1.Thomson J, Hofmann A, Barrett CA, et al. Patient blood management: A solution for South Africa. S Afr Med J 2019;109:471–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.South African National Blood Service. South African Haemovigilance Report. Johannesburg: South African National Blood Service, Western Province Blood Transfusion Service,; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organisation. Availability, safety and quality of blood products Geneva: World Health Organisation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS), (WHO) WHO. Global AIDS Update 2016. Geneva: UNAIDS; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vermeulen M, Lelie N, Coleman C, et al. Assessment of HIV transfusion transmission risk in South Africa: a 10-year analysis following implementation of individual donation nucleic acid amplification technology testing and donor demographics eligibility changes. Transfusion 2019;59:267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Statistics South Africa. Mid-year population estimates, 2020. Pretoria: Statistics South Africa; 202009July2020. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vermeulen M, Lelie N, Sykes W, et al. Impact of individual-donation nucleic acid testing on risk of human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis B virus, and hepatitis C virus transmission by blood transfusion in South Africa. Transfusion 2009;49:1115–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sykes W, van den Berg K, Jacobs G, et al. Discovery of “false Elite Controllers”: HIV antibody-positive RNA-negative blood donors found to be on antiretroviral treatment. J Infect Dis 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hare CB, Pappalardo BL, Busch MP, et al. Seroreversion in subjects receiving antiretroviral therapy during acute/early HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2006;42:700–8. Epub 2006 Jan 23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.de Souza MS, Pinyakorn S, Akapirat S, et al. Initiation of Antiretroviral Therapy During Acute HIV-1 Infection Leads to a High Rate of Nonreactive HIV Serology. Clin Infect Dis 2016;63:555–61. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw365.Epub 2016 Jun 17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jagodzinski LL, Manak MM, Hack HR, et al. Impact of Early Antiretroviral Therapy on Detection of Cell-Associated HIV-1 Nucleic Acid in Blood by the Roche Cobas TaqMan Test. Journal of clinical microbiology 2019;57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sedia Biosciences Corporation. Sedia® HIV-1 LAg-Avidity EIA (for serum or plasma specimens). In: Corporation SB, ed. Portland, Oregon USA: Sedia Biosciences Corporation; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Meintjes G, Moorhouse MA, Carmona S, et al. Adult antiretroviral therapy guidelines 2017. 20172017;18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Camponeschi G, Fast J, Gauval M, et al. An overview of the antiretroviral market. Current opinion in HIV & AIDS 2013;8:535–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Simbayi L, Zuma K, Zungu N, et al. South African National HIV Prevalence, Incidence, Behaviour and Communication Survey, 2017. In: Randall S, ed. South African National HIV Survey, 2017. Cape Town: HSRC Press; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim AA, Mukui I, Young PW, et al. Undisclosed HIV infection and antiretroviral therapy use in the Kenya AIDS indicator survey 2012: relevance to national targets for HIV diagnosis and treatment. Aids 2016;30:2685–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fogel JM, Wang L, Parsons TL, et al. Undisclosed antiretroviral drug use in a multinational clinical trial (HIV Prevention Trials Network 052). J Infect Dis 2013;208:1624–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hoots BE, Wejnert C, Martin A, et al. Undisclosed HIV infection among MSM in a behavioral surveillance study. Aids 2019;33:913–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Levy A, Scherer AM, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Larkin K, Barnes GD, Fagerlin A. Prevalence of and factors associated with patient nondisclosure of medically relevant information to clinicians. JAMA Network Open 2018;1:e185293. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moyo MS, Gaseitsiwe KS, Powis EK, et al. Undisclosed antiretroviral drug use in Botswana: implication for national estimates. AIDS 2018;32:1543–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Grabowski MK, Reynolds SJ, Kagaayi J, et al. The validity of self-reported antiretroviral use in persons living with HIV: a population-based study. Aids 2018;32:363–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dietrich C, Moyo S, Briggs-Hagen M, et al. Sensitivity and specificity of self-reported ARV use in a South African national household survey. AIDS Impact. London, United Kingdom: 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manne-Goehler J, Rohr J, Montana L, et al. ART Denial: Results of a Home-Based Study to Validate Self-reported Antiretroviral Use in Rural South Africa. AIDS Behav 2019;23:2072–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huerga H, Shiferie F, Grebe E, et al. A comparison of self-report and antiretroviral detection to inform estimates of antiretroviral therapy coverage, viral load suppression and HIV incidence in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. BMC Infect Dis 2017;17:653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fogel JM, Sandfort T, Zhang Y, et al. Accuracy of Self-Reported HIV Status Among African Men and Transgender Women Who Have Sex with Men Who were Screened for Participation in a Research Study: HPTN 075. AIDS Behav 2019;23:289–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). UNAIDS DATA 2017. Geneva: UN Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); 201720July2017. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). UNAIDS DATA 2018. Geneva: UN Joint Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS); 201812July2018.Report No.: UNAIDS/JC2929E. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kassanjee R, Pilcher CD, Keating SM, et al. Independent assessment of candidate HIV incidence assays on specimens in the CEPHIA repository. Aids 2014;28:2439–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rehle T, Johnson L, Hallett T, et al. A Comparison of South African National HIV Incidence Estimates: A Critical Appraisal of Different Methods. PLoS One 2015;10:e0133255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laeyendecker O, Konikoff J, Morrison DE, et al. Identification and validation of a multi-assay algorithm for cross-sectional HIV incidence estimation in populations with subtype C infection. J Int AIDS Soc 2018;21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Manak MM, Jagodzinski LL, Shutt A, et al. Decreased Seroreactivity in Individuals Initiating Antiretroviral Therapy during Acute HIV Infection. Journal of clinical microbiology 2019;57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Gosbell IB, Hoad VC, Styles CE, Lee J, Seed CR. Undetectable does not equal untransmittable for HIV and blood transfusion. Vox sanguinis 2019;114:628–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Krever H. Final report: Commission of Inquiry on the Blood System in Canada. Ottawa: Government of Canada; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Muthivhi TN, Olmsted MG, Park H, et al. Motivators and deterrents to blood donation among Black South Africans: a qualitative analysis of focus group data. Transfus Med 2015;25:249–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Graw JA, Eymann K, Kork F, Zoremba M, Burchard R. Risk perception of blood transfusions - a comparison of patients and allied healthcare professionals. BMC Health Serv Res 2018;18:122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]