Abstract

Introduction

The HIV epidemic is increasingly penetrating rural areas of the U.S. due to evolving epidemics of injection drug use. Many rural areas experience deficits in availability of HIV prevention, testing and harm reduction services, and confront significant stigma that inhibits care seeking. This paper examines enacted stigma in healthcare settings among rural people who inject drugs (PWID) and explores associations of stigma with continuing high-risk behaviors for HIV.

Methods

PWID participants (n=324) were recruited into the study in three county health department syringe service programs (SSPs), as well as in local community-based organizations. Trained interviewers completed a standardized baseline interview lasting approximately 40 minutes. Bivariate logistic regression models examined the associations between enacted healthcare stigma, health conditions, and injection risk behaviors, and a mediation analysis was conducted.

Results

Stigmatizing health conditions were common in this sample of PWID, and 201 (62.0%) reported experiencing stigma from healthcare providers. Injection risk behaviors were uniformly associated with higher odds of enacted healthcare stigma, including sharing injection equipment at most recent injection (OR=2.76; CI 1.55, 4.91), and lifetime receptive needle sharing (OR=2.27; CI 1.42, 3.63). Enacted healthcare stigma partially mediated the relationship between having a stigmatizing health condition and engagement in high-risk injection behaviors.

Discussion

Rural PWID are vulnerable to stigma in healthcare settings, which contributes to high-risk injection behaviors for HIV. These findings have critical public health implications, including the importance of tailored interventions to decrease enacted stigma in care settings, and structural changes to expand the provision of healthcare services within SSP settings.

Keywords: PWID, substance use disorder, stigma, HIV, rural

1.0. Introduction

The HIV epidemic is increasingly penetrating rural areas of the U.S., with growing HIV incidence documented in historically low prevalence rural communities due to evolving epidemics of injection drug use (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017; Lerner and Fauci, 2019). Recent notable HIV outbreaks among rural people who inject drugs (PWID) occurred in 2018–2019 in rural West Virginia and North Carolina (Samoff et al., 2020); of note, many of these affected counties were identified as highly vulnerable to HIV by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) in 2016 (Van Handel et al., 2016).

Kentucky is among seven states with high rural HIV burden (Giroir, 2020). Rural Appalachian Kentucky has experienced an entrenched substance use epidemic for the past two decades involving opioids (Havens et al., 2013; Staton-Tindall et al., 2015; Surratt et al., 2018) and more recently, growing stimulant use (Surratt et al., 2020a). Serious health consequences associated with injection drug use in Kentucky include elevated rates of acute hepatitis C (HCV) infection (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014), particularly among persons aged ≤30 years residing in non-urban areas, with a risk factor of injection drug use (Zibbell et al., 2015) and overdose rates that far exceed the national average (Slavova et al., 2020). Incident HIV cases related to injection drug use in Kentucky have increased from 6% of new diagnoses in 2013 to 21% in 2018 and reach 36.4% among women diagnosed in 2018 (Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services. Department for Public Health., 2020).

PWID often engage in high-risk behaviors for HIV including risky injection practices (Boodram et al., 2011; Hagan et al., 2004; Hahn et al., 2002, 2001; Meade et al., 2009), having an injecting sex partner (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012), and having unprotected sex and multiple sex partners (Booth et al., 2011). Rural PWID are generally an understudied population (Paquette and Pollini, 2018) yet elevated injection risk behavior profiles have been described (Havens et al., 2011b, 2011a; Staton-Tindall et al., 2015; Young et al., 2013). Many rural areas experience critical deficits in access to primary care, availability of HIV prevention, testing and harm reduction services, and affordable transportation, and confront significant stigma surrounding substance use and HIV services that inhibits care seeking (AIDSVu, 2016; Bolinski et al., 2019; Des Jarlais et al., 2015, 2005; Schafer et al., 2017; Schranz et al., 2018). Suboptimal access to harm reduction and treatment services in rural areas has recently been characterized as a major threat to longstanding progress on injection drug use (IDU)-related HIV transmission in the US (Lerner and Fauci, 2019).

Stigma acts as a fundamental driver of population health, contributing to adverse outcomes across numerous health conditions through multiple pathways (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013). Stigma is a complex social process incorporating the co-occurrence of labeling, stereotyping, separation, status loss, and discrimination (Link and Phelan, 2001). Stigma involves a fundamentally devalued social identity (Goffman, 1963) based on labeled attributes that diverge from the socially judged ideal (Becker, 1963). Madden (2019) describes prevalent stigma in the healthcare sector directed toward individuals with specific health conditions such as HIV and mental illness and varying according to overlapping membership in socially marginalized groups, condition visibility, and perceived agency over the condition. HIV has long been a morally and behaviorally stigmatized condition (Chambers et al., 2015) that is intersected by multiple social identities (Jackson-Best and Edwards, 2018; Lacombe-Duncan, 2016). Despite increased knowledge about HIV and a radically improved treatment landscape, significant stigma related to HIV persists (Levi-Minzi and Surratt, 2014; Pulerwitz et al., 2010; Stangl and Grossman, 2013), including among healthcare providers (Nyblade et al., 2009; Stringer et al., 2016), which represents a formidable barrier to care that fuels risk of HIV-related morbidity and mortality (Muncan et al., 2020). Among people who use drugs, pervasive stigma surrounding substance use disorder (SUD) has also been reported as a major contributor to suboptimal treatment seeking and disengagement from care (Tsai et al., 2019), resulting in adverse mental and physical health outcomes (Muncan et al., 2020).

Stigma encompasses distinct domains including internalized or self-stigma (negative feelings and beliefs applied to the self), enacted stigma (actual experiences of discrimination, stereotyping, and/or prejudice from others), and anticipated stigma (expectations of discrimination, stereotyping and/or prejudice from others in the future) (Earnshaw and Chaudoir, 2009). A robust research literature has indicated that each of these multiple domains of stigma is associated with adverse impacts to quality of life, the experience of healthcare, and overall health outcomes among people living with HIV (Calabrese et al., 2016; Chambers et al., 2015; Earnshaw et al., 2013; Sayles et al., 2007). Similarly, condition stigma (Madden, 2019) has been widely documented with regard to HCV infection (Brener et al., 2015; Dowsett et al., 2017; Marinho and Barreira, 2013; Saine et al., 2020), mental illness (Corrigan et al., 2006; Knaak et al., 2017; Link and Phelan, 2001; Mannarini and Rossi, 2018), opioid overdose (Tsai et al., 2019) and chronic pain (De Ruddere and Craig, 2016), including in healthcare settings, which creates significant barriers to care utilization and contributes to suboptimal health outcomes (Tsai et al., 2019).

SUD is arguably one of the most stigmatized health conditions (Smith et al., 2016), even among healthcare professionals (McGinty and Barry, 2020). At the provider level, stigma can manifest as reduced willingness to screen for or treat SUD and negative attitudes toward patients that lead to poor care delivery (Paquette and Pollini, 2018), all of which are compounded by a general lack of education and training among providers and poor support structures for patients (van Boekel et al., 2013; Yang et al., 2017). Stigma among people with SUD contributes to loss of self-esteem, isolation, low levels of care seeking to avoid rejection, and low trust in healthcare providers to deliver needed care (Pullen and Oser, 2014; Rural Health Information Hub, 2018; Yang et al., 2017).

Among individuals impacted by SUD, particularly high levels of stigma have been documented among PWID, including enacted, perceived, and self-stigma (Luoma et al., 2007; Wilson et al., 2014). Evidence suggests that PWID experience significant stigma from a variety of sources, including community members and healthcare providers (Brener et al., 2015; von Hippel et al., 2018). Although not specific to the healthcare setting, approximately 60% of the sample in the Luoma study (2007) reported enacted stigma related to their SUD. Brener and colleagues (Brener et al., 2015, 2010) demonstrated pervasive stigma among PWID associated with healthcare and treatment encounters, which suggests that PWID are intensely vulnerable to stigmatizing experiences that dissuade care seeking and contribute to lower likelihood of healthcare uptake in the future (Muncan et al., 2020; Paquette and Pollini, 2018). In the context of elevated health complications, including overdose, mental distress, chronic health problems, and physical pain, which frequently impact PWID (Anagnostopoulos et al., 2018; Dahlman et al., 2017; Otachi et al., 2020; Reddon et al., 2018; Staton et al., 2018), stigma presents a potentially formidable barrier to uptake of needed care that contributes to poor health outcomes (Cloud et al., 2019; Muncan et al., 2020; Wilson et al., 2014).

This paper examines the experience of discrimination in healthcare settings among rural PWID impacted by stigmatized health conditions and explores associations of stigma with engagement in high-risk injecting behaviors for HIV. An emerging research literature among urban PWID has described an association between discrimination against PWID and injecting-related risks and harms (Bayat et al., 2020; Couto E Cruz et al., 2018; Friedman et al., 2017; Latkin et al., 2010; Wilson et al., 2014), but this phenomenon has been understudied in rural settings. In low resource and medically underserved rural areas, health provider-based stigma toward PWID may have a chilling effect on care and services uptake, effectively limiting exposure to health promotion and treatment interventions. This paper explores enacted stigma toward rural PWID with chronic health conditions as a potential contributor to ongoing engagement in high-risk injection behaviors.

2.0. Methods

Data are drawn from a National Institute on Drug Abuse supported study of syringe service program (SSP) utilization among PWID in three Appalachian Kentucky counties.

2.1. Study Sample

Participants (n=324) were recruited through multiple methods, including respondent driven sampling (RDS) (Heckathorn, 1997), and direct outreach when RDS referrals were not robust. Details of the study recruitment strategies have been previously reported (Buttram and Surratt, 2020). Eligible participants were age 18 or over and reported injection drug use at least once in the past 30 days. By design, the sample included both current SSP users and non-users. 324 PWID participants enrolled and completed baseline interviews between February 2018 and October 2019.

2.2. Study procedures

Study enrollment and interviews were conducted in three county health department fixed site SSPs, as well as in local faith organizations for the non-SSP sample. All study protocols were reviewed and approved by the university’s Institutional Review Board. Following study eligibility screening, study staff reviewed informed consent materials and obtained written consent to participate. Trained interviewers then completed a standardized face to face baseline interview lasting approximately 40 minutes. All questions were read to participants to enhance comprehension and ensure completeness of information. A $20 gift card incentive was provided to participants upon interview completion.

2.3. Study Measures

The study questionnaire was adapted from the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs GAIN; (GAIN, 2016) and included abbreviated segments of several GAIN core domains: demographics, substance use, physical health, sexual risk behaviors, and environment.

2.4. Variables of Interest.

Demographic characteristics.

Participants were asked to report age, gender, and race/ethnicity. Participants were able to identify as male, female, transgender, or other. For analyses, this variable was dichotomized as “female” versus all other. Ethnicity was ascertained by asking all participants whether they were Hispanic and asking all participants for self-identified race(s). County indicates the location of study enrollment. Counties varied in population size and rural status. Clark County is metropolitan with rurally designated census tracts, while both Knox and Owsley Counties are entirely non-metropolitan based on Rural-Urban Continuum Code indicators.

Substance Use Behaviors.

By design, all study participants had injected substances at least once in the month prior to interview. Current primary drug of injection was assessed with the question, “In the past month which drug did you inject most often?” Frequency of injection was gathered by asking participants, “How many times (number of injections) did you inject drugs in the last 30 days?”

Stigmatized Health Conditions.

We assessed five health conditions that have been associated with stigma in the scientific literature (Corrigan et al., 2006; De Ruddere and Craig, 2016; Dowsett et al., 2017; Knaak et al., 2017; Link and Phelan, 2001; Madden, 2019; Mannarini and Rossi, 2018; Marinho and Barreira, 2013; Saine et al., 2020; Tsai et al., 2019). The 6 item GAIN Internalizing Disorder Screener, which includes symptoms and recency of depression, anxiety, trauma, psychosis, and suicidality, was used to assess mental health problems. Severe distress in the past 90 days resulted from endorsement of three or more symptoms. Substance Use Disorder was ascertained using the 11-item GAIN Substance Use Disorder scale based on Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (GAIN, 2016). Three or more symptoms endorsed during the past 90 days was classified as “severe” versus “not severe” for the present analysis. Overdose was assessed by a single item asking participants if they had ever personally experienced an overdose event. Hepatitis C status was based on self-report to two paired items: “Have you ever had a blood test to check for Hepatitis C infection,” followed by “What was the result of your most recent test?” Finally, physical pain was assessed with the question, “During the past 90 days have you had a lot of physical pain or discomfort?” with a yes/no response choice. We did not include HIV status in our analysis of health conditions, due to the extremely low prevalence of self-reported HIV in our sample (1.2%). For analysis, we summed endorsements of these five health conditions and dichotomized into presence of stigmatizing condition (yes/no).

Health Care Utilization.

Substance use treatment was assessed by asking participants, “when was the last time (if ever) you receive any counseling, treatment, medication, case management or aftercare for your use of alcohol or any drug?” We categorized endorsement of treatment participation in the past 90 days into “treatment” versus “no treatment”. Participants also responded to additional dichotomous questions to assess general healthcare utilization, including ““Have you received any care from a doctor in the past year?” For HIV testing, we asked participants to report the time interval that they received their last test, and dichotomized responses to within the past 6 months versus more than 6 months ago, following testing guidelines for high-risk populations. Finally, to measure SSP utilization, we asked participants “How many times have you visited this SSP site in the past 6 months?”

Substance Use Stigma.

We measured enacted or experienced stigma related to substance use using the validated Substance Use Stigma Mechanisms Scale (SU-SMS) (Smith et al., 2016). The SU-SMS captures enacted stigma from both family members and healthcare providers, with 3 self-report items tapping each stigma source. Items are measured on a five-point Likert scale ranging from never to very often, with higher scores representing more enacted stigma. For this analysis, we examined enacted stigma from healthcare providers. Responses from the three items were summed and dichotomized into healthcare stigma (yes/no) for descriptive presentation.

Injection Risk Behaviors.

Injection related risk via sharing behaviors was ascertained by examining five indicators that capture recent risk at last injection, as well as past three month and lifetime periods. Participants reported responses to the following prompts: “Was any equipment shared the last time you injected?” (no/yes); “How many people did you share needles or syringes with in the past 3 months?” (0/1+); “How many people did you share cooker/cotton/rinse water with in the past three months? (0/1+); “When was the last time you used needles previously used by someone else?” (never/ever); and “How often do you inject with a brand-new needle? (always/less than always).

2.5. Analyses

Descriptive statistics, including means, standard deviations and proportions were calculated for the variables of interest in SPSS version 25. Bivariate logistic regression models examined the associations between enacted healthcare stigma, health conditions, injection risk behaviors and other independent variables of interest. Significant associations are indicated at p≤.05 in Table 1. We then performed a mediation analysis to further examine the observed associations between the presence of stigmatizing health conditions, enacted healthcare stigma, and high-risk injection behaviors.

Table 1:

Sample Characteristics by Enacted Healthcare Stigma (N=324)

| Healthcare Stigma* | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Demographics and Background | ||||

| Age (mean; SD) | 37.4 (9.2) | 36.9 (10.1) | 1.006 | .98, 1.03 |

| Female gender | 101 (50.2) | 58 (50.0) | 1.010 | .64, 1.60 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Hispanic | 4 (2.0) | 3 (2.6) | ref | ref |

| African American/Black | 3 (1.5) | 2 (1.7) | 1.28 | .28, 5.83 |

| White | 181 (91.0) | 106 (92.2) | 1.13 | .11, 11.6 |

| Other race/ethnicity | 11 (5.5) | 4 (3.5) | 2.06 | .31, 13.6 |

| County of residence | ||||

| Clark | 100 (49.8) | 48 (41.4) | ref | ref |

| Knox | 74 (36.8) | 55 (47.4) | .65 | .40, 1.05 |

| Owsley | 27 (13.4) | 13 (11.2) | .99 | .47, 2.10 |

| Drug Injection | ||||

| Years of Injection history (mean; SD) | 9.5 (7.8) | 7.7 (8.3) | 1.03 | .99, 1.06 |

| Times injecting, past month** (mean; SD) | 92.9 (78.2) | 77.5 (72.2) | 1.00 | 1.00,1.01 |

| Primary Drug of Injection, past month | ||||

| Heroin | 24 (11.9) | 16 (13.9) | ref | ref |

| Methamphetamine | 100 (49.8) | 65 (56.5) | 1.03 | .51, 2.08 |

| Prescription opioids | 30 (14.9) | 6 (5.2) | 3.33 | 1.13, 9.83 |

| Buprenorphine | 43 (21.4) | 25 (21.7) | 1.15 | .51, 2.56 |

| Other | 4 (2.0) | 3 (2.6) | .89 | .18, 4.52 |

| Shared any Equipment at last injection | 69 (36.3) | 19 (17.1) | 2.76 | 1.55, 4.91 |

| Shared Needles/Syringes, past 90 days | 83 (41.5) | 27 (23.5) | 2.31 | 1.38, 3.87 |

| Shared Cooker/Cotton/Rinse water, past 90 days | 89 (45.6) | 30 (26.5) | 2.32 | 1.40, 3.84 |

| Receptive needle sharing, lifetime | 112 (56.3) | 42 (36.2) | 2.27 | 1.42, 3.63 |

| Did not always inject with new needle, past 90 days | 46 (23.4) | 45 (39.5) | 2.14 | 1.30, 3.53 |

| Health Conditions | ||||

| Severe mental distress, past 90 days | 170 (84.6) | 86 (74.1) | 1.91 | 1.09, 3.37 |

| Severe substance use disorder, past 90 days | 148 (73.6) | 58 (50.0) | 2.79 | 1.73, 4.52 |

| Overdose history | 84 (41.8) | 34 (29.3) | 1.73 | 1.06, 2.82 |

| HCV positive | 99 (49.5) | 27 (23.3) | 3.23 | 1.94, 5.39 |

| Severe pain, past 90 days | 126 (63.6) | 51 (44.7) | 2.16 | 1.35, 3.46 |

| Health Services Utilization | ||||

| Substance use treatment, past 90 days | 56 (27.9) | 20 (17.4) | 1.83 | 1.04, 3.25 |

| Received any medical care, past year | 149 (76.0) | 73 (63.5) | 1.82 | 1.11, 3.01 |

| HIV testing, past 6 months*** | 68 (36.6) | 35 (32.7) | 1.19 | .72, 1.96 |

| SSP visits, past month (mean; SD) | 1.79 (2.70) | 1.83 (3.70) | .996 | .93, 1.07 |

N=317;

N=303;

N=293

The mediation analysis was performed using Mplus version 8.5 (Muthén and Muthén, 2017). For the mediation analysis, latent variables were used to represent both the mediator (healthcare related stigma) and the outcome (risky injection behaviors). Latent variables represent hypothetical constructs that are not measured directly, but instead constructed via a measurement model using observed variables as indicators of the latent construct. Three continuous indicators were used to represent the health care related stigma latent variable, and five indicators were used to represent risky injection behaviors. Both latent variables were continuous, all factor loads were freely estimated, and the scale of the latent variable was set by fixing its variance equal to one.

Due to the inclusion of latent variables, a structural equation modeling (SEM) framework was utilized to test the mediation hypothesis. Prior to testing direct and indirect effects, the degree to which the model fit the data was first assessed. The goodness of fit indices reported and assessed include: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and the Comparative Fit Index (CFI). Hu and Bentler’s (1999) cutoffs were used for determining model adequacy.

To aid in interpretation, only endogenous variables were standardized. For direct effects, the significance of standardized path coefficients was found by dividing the estimate by its standard error and comparing the resulting statistic to the critical value from a standard normal distribution. These values were also used to construct 95% confidence intervals. However, using a similar approach to test mediated effects (i.e., the Sobel method) results in low power and Type I error rates (Mackinnon et al., 2004). Instead, bias corrected bootstrapped confidence intervals are the preferred method of assessing statistical significance and are reported here. Theta parameterization was used with a weighted least square mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimator. Bootstrap confidence intervals were estimated using 5,000 resamples.

3.0. Results

Sample characteristics and associations with enacted healthcare stigma are presented in Table 1. Overall, the sample had a mean age of 37.3 years and was 50% female, 49.4% male, 0.3% transgender, and 0.3% other. Of the 324 respondents, 201 (62.0%) reported experiencing substance use stigma from healthcare providers. No differences in enacted stigma were observed by age, gender, race/ethnicity, or county of residence. The most frequently reported substance of injection among our sample was methamphetamine, with more than half of the sample endorsing this as their primary drug in the past month. In terms of primary drug, only primary prescription opioids were associated with enacted stigma; the odds of enacted stigma were more than three times higher among primary prescription opioid injectors as compared to other substance injectors (OR=3.33; CI 1.13, 9.83). Neither length of injection history nor frequency of injecting was associated with enacted stigma in this sample.

Injection sharing behaviors were uniformly associated with endorsement of enacted healthcare stigma. Specifically, those who shared injection equipment at most recent injection (OR=2.76; CI 1.55, 4.91), those who shared injection equipment in the past 90 days (OR=2.31; CI 1.38, 3.87), those who shared cooker, cotton or rinse water in the past 90 days (OR=2.32; CI 1.40,3.84), those who reported lifetime receptive needle sharing (OR=2.27; CI 1.42, 3.63), and those who reported not always using new needles to inject (OR=2.14, CI 1.30, 3.53) each had significantly higher odds of experiencing enacted healthcare stigma.

Stigmatizing health conditions were exceedingly common in this sample of PWID. Moreover, the experience of healthcare stigma was significantly associated with the presence of chronic health conditions. Those endorsing severe mental health problems had increased odds of enacted stigma (OR=1.91; CI 1.09, 3.37), as did those endorsing severe substance use disorder (OR=2.79, CI 1.73, 4.52) and severe pain (OR=2.16; CI 1.35, 3.46) in the past 90 days. We also found significant differences with those having an overdose history (OR=1.73; CI 1.06, 2.82) and a positive HCV result (OR=3.23; CI 1.94, 5.39) experiencing higher odds of enacted healthcare stigma. With regard to health services utilization, those seeking substance use treatment in the past 90 days (OR=1.83; CI 1.04, 3.25) and medical care in the past year (OR=1.82; CI 1.11, 3.01) also reported higher odds of healthcare stigma. HIV testing uptake and SSP utilization were not significantly associated with enacted healthcare stigma in this sample.

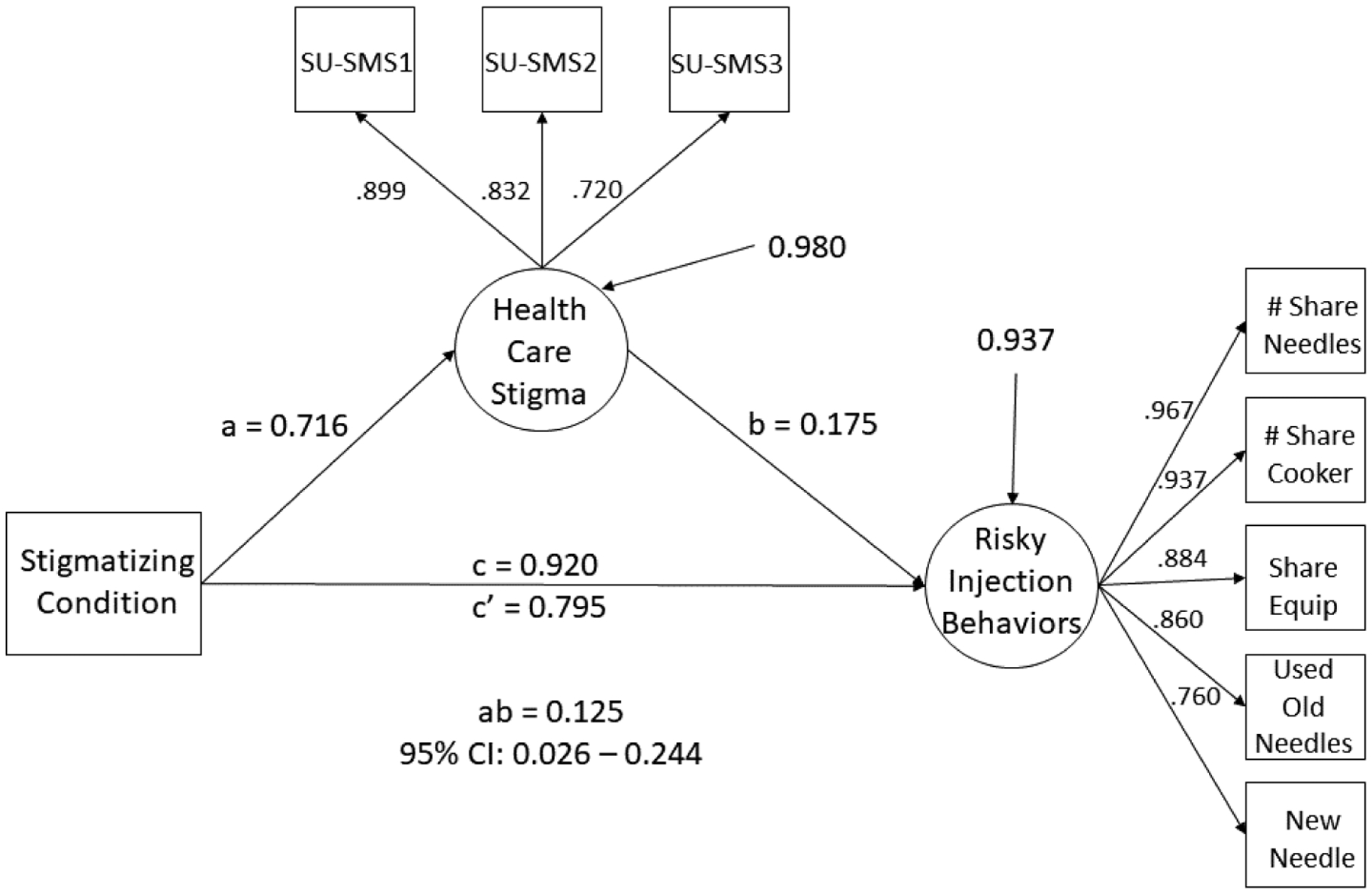

The results of the mediation analysis, including the measurement portion of the full SEM mediation model, can be seen in Figure 1. The standardized factor loadings for health care related stigma were all large (range: .720 – .899, mean = .817), as were the standardized factor loadings for risky injection practices (range: .706 – .967, mean = .871). Fit indices for the full measurement model indicated that the model provided a good fit to the data (CFI = 0.984; RMSEA = 0.066, RMSEA 90% CI: 0.042 – 0.091, probability RMSEA ≤ .05 = 0.129). For the structural model, all goodness of fit indices indicated that the model provided good fit to the data (CFI = 0.985; RMSEA = 0.057, RMSEA 90% CI: 0.034 – 0.079, probability RMSEA ≤ .05 = 0.284). As a result, the next step was to estimate and interpret the path coefficients in the structural model.

Figure 1.

Latent variable mediation model where Healthcare Stigma mediates the relationship between having a stigmatizing condition and engaging in risky injection behaviors. Squares represent observed variables/indicators, and circles represent latent variables. All loadings and paths are standardized and significant at p < .05. Variance estimates for endogenous latent variables represent residual variance.

The total effect of having a stigmatizing condition on risky injection behaviors was significant (c path, β = 0.920, 95% CI: 0.128 – 1.309, p = .006). The effect of having a stigmatizing condition was significantly associated with the experience of health care related stigma (a path, β = 0.716, 95% CI: 0.369 – 0.979, p < .001). The association between health care related stigma and risky injection behaviors was also significant (b path, β = 0.175, 95% CI: 0.045 – 0.304, p = 0.009). After controlling for health care related stigma, the direct effect of having a stigmatizing condition on risky injection behaviors was still significant, but reduced in magnitude (c’ path, β = 0.795, 95% CI: 0.010 – 1.194, p = 0.010). Furthermore, the indirect effect of having a stigmatizing condition on risky injection behaviors through the experience of health care related stigma was significant (ab path, β = 0.125, 95% Bootstrap CI: 0.026 – 0.244) as the 95% bootstrap confidence intervals did not contain zero.

4.0. Discussion

Our findings indicate that rural PWID experience elevated levels of enacted stigma and discrimination in healthcare settings, with nearly two-thirds reporting this experience. Our findings are consistent with Luoma et al. (2007), who reported a high prevalence of enacted stigma (~60%) in a sample of PWID patients in treatment settings and research groups in Australia that have documented frequent discrimination against PWID across multiple sectors (Brener et al., 2015; Couto E Cruz et al., 2018; von Hippel et al., 2018).

PWID living in rural areas may be especially impacted by enacted healthcare stigma given the limited availability of healthcare and social services in these communities (Muncan et al., 2020), which constrains options to change providers or seek services in alternate locations. This situation is often compounded by poor transportation systems and stigmatizing community attitudes toward persons who use drugs and/or are infected with HIV (Cloud et al., 2019; Des Jarlais et al., 2018). Prior research in rural or remote locations has demonstrated specific health provider-based stigma in hospital, urgent care, and pharmacy settings as PWID attempted to seek treatment for SUD-related issues or access sterile syringes (McCutcheon and Morrison, 2014; Paquette et al., 2018). In these settings, PWID reported being exposed to shaming and negative attitudes from providers and poor care provision or outright refusal of care, including being actively dissuaded from returning. These experiences were linked by participants to delays or complete avoidance of future care seeking. Of note, in the bivariate analyses we observed that primary prescription opioid injection was associated with higher enacted healthcare stigma compared to other substance injection. Given that healthcare practices are often sources for obtaining opioid medications that may be misused (Cicero et al., 2011), we speculate that this finding may reflect the potential for negative or disparaging encounters with providers around medication use and compliance.

Our sample reported an elevated prevalence of multiple health conditions that are highly stigmatized, based on membership in socially marginalized groups, condition visibility and perceived agency over the condition (Madden, 2019). Specifically, we observed more than 3 times higher odds of enacted stigma among individuals reporting HCV positivity and 2.8 times higher odds among persons with severe substance use disorder. Though approximately 39% (N=126) of our overall respondents reported having tested positive for Hepatitis C, nearly two-thirds did not receive follow-up care after diagnosis, which is likely due to avoidance of care or unavailability of care. Additionally, only 23.8% had accessed any type of substance use disorder treatment within the past 90 days. Thus, our data indicates high levels of unmet need for treatment and other medical care in PWID recruited to this study.

PWID appear vulnerable to stigmatizing experiences generally, but also in the context of seeking treatment or healthcare, which Madden (2019) has referred to as intervention stigma. In our study, those seeking substance use treatment in the past 90 days and medical care in the past year reported higher odds of experiencing healthcare stigma. Thus, our findings resonate or support the notion of intervention stigma, where care seeking serves to amplify or exacerbate exposure to discriminatory attitudes and behaviors by disclosing that the individual has injected substances. Moreover, in the rural Appalachian context, stigma in small communities is pervasive and may prevent PWID from seeking services due concerns of confidentiality, judgement, or community backlash (Cloud et al., 2019; Surratt et al., 2020b, 2020a).

Our findings highlight the critical need for interventions that address stigma targets among healthcare providers in order to increase compassionate and non-judgmental care provision, and engagement and retention in care for PWID. Educational interventions could potentially be tailored for particular groups of health professionals likely to come into contact with people who use alcohol or other drugs (Lancaster et al., 2017), increasing education around the medical aspects of addiction and discussing anti-stigma practices and language usage (Harling and Turner, 2012). Additionally, educational interventions for providers should seek to enhance their awareness of substance use as a medical disorder (Biancarelli et al., 2019), challenge or reframe stigmatizing beliefs that may hinder provision of optimal care, and increase their awareness of available evidence-based substance use treatment interventions (Tsai et al., 2019) as a way of improving healthcare utilization and outcomes for PWID. The creative integration of peer health workers and peer navigators into healthcare teams may also be an effective approach to bridge the divide between PWID patients and providers, to provide advocacy, and to increase access to appropriate care (Hallum-Montes et al., 2013; Pitpitan et al., 2020).

Importantly, we found that healthcare stigma among rural PWID contributes to continued risk for HIV through high-risk injection practices, even among PWID who currently access the local SSPs. In our sample of PWID, we found significantly higher odds of experiencing enacted healthcare stigma among those who shared injection equipment in their most recent injection and in the past 90 days, those who shared cooker, cotton or rinse water in the past 90 days, those reporting lifetime receptive needle sharing, and those reporting to not always use new needles to inject. Thus, addressing stigma is an important step in reducing HIV risk behaviors among PWID. These findings resonate with prior literature in urban settings, which documented increased injection related harms among PWID experiencing frequent stigma and discrimination (Couto E Cruz et al., 2018; Wilson et al., 2014).

In the mediation model, we demonstrated that enacted healthcare stigma partially mediated the relationship between having a stigmatizing health condition and engagement in high-risk injection behaviors. The mediation model indicates that experienced healthcare stigma was positively associated with both presence of a stigmatizing health condition and greater injection risk. This model provides evidence that enacted healthcare stigma carries part of the influence of chronic health conditions to ongoing injection risk. This finding is particularly important for HIV prevention planning with rural PWID, as it suggests that intervening on stigma targets would reduce injection risk among this group. This finding resonates with Bayat et al., (2020) highlighting the importance of taking stigma into consideration when designing drug use prevention strategies. Educational interventions geared towards addressing drug-related stigma should challenge negative attitudes towards drug use and enhance the understanding of problematic drug use among providers (Bayat et al., 2020). Additionally, these programs should seek to address multiple stigma domains related to HIV and injection drug use, which hinder healthcare utilization (Stringer et al., 2019). The inclusion of peer support workers and peer navigators as change agents in stigma reduction interventions in traditional healthcare settings may build on the widespread use of peers as effective educators and advocates for harm reduction services, which is premised on using lived experience and experiential knowledge to appropriately engage those in active use (Bassuk et al., 2016; Gilchrist et al., 2017; Hay et al., 2017; Henderson et al., 2017; Strike et al., 2015). Although there are fewer studies to document the effectiveness of peer supported health interventions in rural areas, a recent review article found that peer-led support for chronic health conditions showed positive outcomes in the majority of studies (Lauckner and Hutchinson, 2016).

Given that utilization of the SSPs in the present study was not independently associated with experienced healthcare stigma, an alternative, promising approach may involve structural changes to support integrating additional services and expand scope of practice for healthcare provision at point of care in rural SSPs, which is experienced as a safe, non-judgmental space operating under harm reduction principles. Moving care outside of traditional medical settings that expose PWID to stigma may improve uptake of preventive care and treatment (Lancaster et al., 2017). SSPs are a proven structural HIV prevention tool (Des Jarlais et al., 2005; Neaigus et al., 2008; Vogt et al., 1998), and are beneficial in reducing other healthcare related complications among PWID due to their comfort with the program and staff (Castillo et al., 2020). Therefore, utilizing SSPs as a safety-net for providing wrap around services seems promising in encouraging more PWID to seek care and engage in treatment.

4.1. Limitations

There are several limitations to this study that warrant mentioning. First, the sample cannot be considered representative, given that RDS recruitment of PWID was not robust in these rural community sites, warranting caution in generalizing the findings. The study also relied on self-report data gathered in face-to-face interviews, which may have been impacted by recall problems and social desirability bias; nevertheless, the high levels of mental health problems, substance use disorder symptoms, and injection risk behaviors reported suggest that respondents generally felt comfortable to reliably report sensitive information regarding socially undesirable behaviors. Importantly, our analyses involve cross-sectional data, which does not allow for the examination of temporal change and limited our modelling approach. Nevertheless, these strong associations suggest that interventions related to stigma reduction in healthcare settings may be important in increasing care and reducing high risk injection behaviors.

5.0. Conclusion

Rural PWID are vulnerable to episodes of stigma and discrimination in healthcare settings, which contributes to lack of routine care and continued engagement in high-risk injection behaviors for HIV and HCV. These findings have critical public health implications, including the importance of developing specifically tailored interventions to decrease enacted stigma in case settings, and considering structural changes to expand the provision of healthcare services within SSP settings. In the context of high HCV prevalence among rural PWID and the growing availability of effective treatments (Fraser et al., 2019), reducing enacted stigma could contribute to increased treatment uptake and continued progress on HCV elimination.

Highlights.

Rural people who inject drugs experience significant stigma in healthcare settings

Healthcare stigma among rural PWID contributes to high-risk injection practices

Expanding healthcare provision in rural SSPs may further reduce HIV risk among PWID

Acknowledgements:

This research was supported by Grant Number R21DA044251 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Role of funding source

This research was supported by Award Number R21DA044251 from the National Institute on Drug Abuse. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of interest

No conflicts declared.

References

- AIDSVu, 2016. Local Data : Kentucky [WWW Document]. Emory Univ. Roll. Sch. Public Heal Atlanta, GA. URL https://aidsvu.org/local-data/united-states/south/kentucky/ (accessed 2.20.20). [Google Scholar]

- Anagnostopoulos A, Abraham AG, Genberg BL, Kirk GD, Mehta SH, 2018. Prescription drug use and misuse in a cohort of people who inject drugs (PWID) in Baltimore. Addict. Behav 81, 39–45. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.01.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bassuk EL, Hanson J, Greene RN, Richard M, Laudet A, 2016. Peer-Delivered Recovery Support Services for Addictions in the United States: A Systematic Review. J. Subst. Abuse Treat 63, 1–9. 10.1016/j.jsat.2016.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bayat A-H, Mohammadi R, Moradi-Joo M, Bayani A, Ahounbar E, Higgs P, Hemmat M, Haghgoo A, Armoon B, 2020. HIV and drug related stigma and risk-taking behaviors among people who inject drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Addict. Dis 38, 71–83. 10.1080/10550887.2020.1718264 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becker HS, 1963. Outsiders: Studies in the Sociology of Deviance. The Free Press, New York, New York. 10.1111/j.1754-8845.1990.tb00088.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biancarelli DL, Biello KB, Childs E, Drainoni M, Salhaney P, Edeza A, Mimiaga MJ, Saitz R, Bazzi AR, 2019. Strategies used by people who inject drugs to avoid stigma in healthcare settings. Drug Alcohol Depend. 198, 80–86. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2019.01.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolinski R, Ellis K, Zahnd WE, Walters S, McLuckie C, Schneider J, Rodriguez C, Ezell J, Friedman SR, Pho M, Jenkins WD, 2019. Social norms associated with nonmedical opioid use in rural communities: a systematic review. Transl. Behav. Med 9, 1224–1232. 10.1093/tbm/ibz129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boodram B, Hershow RC, Cotler SJ, Ouellet LJ, 2011. Chronic hepatitis C virus infection and increases in viral load in a prospective cohort of young, HIV-uninfected injection drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 119, 166–171. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Booth RE, Campbell BK, Mikulich-Gilbertson SK, Tillotson CJ, Choi D, Robinson J, Calsyn DA, Mandler RN, Jenkins LM, Thompson LL, Dempsey CL, Liepman MR, McCarty D, 2011. Reducing HIV-related risk behaviors among injection drug users in residential detoxification. AIDS Behav. 10.1007/s10461-010-9751-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener L, Horwitz R, Von Hippel C, Bryant J, Treloar C, 2015. Discrimination by health care workers versus discrimination by others: Countervailing forces on HCV treatment intentions. Psychol. Heal. Med 20, 148–153. 10.1080/13548506.2014.923103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brener L, von Hippel W, von Hippel C, Resnick I, Treloar C, 2010. Perceptions of discriminatory treatment by staff as predictors of drug treatment completion: Utility of a mixed methods approach. Drug Alcohol Rev. 29, 491–497. 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00173.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buttram ME, Surratt HL, 2020. Factors Associated with Gabapentin Misuse among People Who Inject Drugs in Appalachian Kentucky. Subst. Use Misuse 55, 2364–2370. 10.1080/10826084.2020.1817082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calabrese SK, Burke SE, Dovidio JF, Levina OS, Uusküla A, Niccolai LM, Heimer R, 2016. Internalized HIV and Drug Stigmas: Interacting Forces Threatening Health Status and Health Service Utilization Among People with HIV Who Inject Drugs in St. Petersburg, Russia. AIDS Behav. 20, 85–97. 10.1007/s10461-015-1100-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castillo M, Ginoza MEC, Bartholomew TS, Forrest DW, Greven C, Serota DP, Tookes HE, 2020. When is an abscess more than an abscess? Syringe services programs and the harm reduction safety-net: a case report. Harm Reduct. J 17, 34. 10.1186/s12954-020-00381-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2017. HIV and Injection Drug Use [WWW Document]. Vital Signs. URL https://www.cdc.gov/vitalsigns/hiv-drug-use/infographic.html (accessed 2.28.20). [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2014. Viral Hepatitis Surveillance - United States, 2014.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012. HIV infection and HIV-associated behaviors among injecting drug users- 20 cities, United States, 2009. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 61, 133–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers LA, Rueda S, Baker DN, Wilson MG, Deutsch R, Raeifar E, Rourke SB, Team TSR, 2015. Stigma, HIV and health: a qualitative synthesis. BMC Public Health 15, 848. 10.1186/s12889-015-2197-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicero TJ, Kurtz SP, Surratt HL, Ibanez GE, Ellis MS, Levi-Minzi MA, Inciardi JA, 2011. Multiple Determinants of Specific Modes of Prescription Opioid Diversion. J. Drug Issues 41, 283–304. 10.1177/002204261104100207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloud DH, Ibragimov U, Prood N, Young AM, Cooper HLF, 2019. Rural risk environments for hepatitis c among young adults in appalachian kentucky. Int. J. Drug Policy 72, 47–54. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.05.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan PW, Watson AMYC, Barr L, 2006. The Self-Stigma of Mental Illness : Implications for Self-Esteem and Self-Efficacy. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol 25, 875–884. [Google Scholar]

- Couto E Cruz C, Salom CL, Dietze P, Lenton S, Burns L, Alati R, 2018. Frequent experience of discrimination among people who inject drugs: Links with health and wellbeing. Drug Alcohol Depend. 190, 188–194. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.06.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dahlman D, Kral AH, Wenger L, Hakansson A, Novak SP, 2017. Physical pain is common and associated with nonmedical prescription opioid use among people who inject drugs. Subst. Abuse Treat. Prev. Policy 12, 29. 10.1186/s13011-017-0112-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Ruddere L, Craig KD, 2016. Understanding stigma and chronic pain: a-state-of-the-art review. Pain 157, 1607–1610. 10.1097/j.pain.0000000000000512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Hammett TM, Kieu B, Chen Y, Feelemyer J, 2018. Working With Persons Who Inject Drugs and Live in Rural Areas: Implications From China/Vietnam for the USA. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep 15, 302–307. 10.1007/s11904-018-0405-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Nugent A, Solberg A, Feelemyer J, Mermin J, Holtzman D, 2015. Syringe Service Programs for Persons Who Inject Drugs in Urban, Suburban, and Rural Areas — United States, 2013. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 64, 1337–1341. 10.15585/mmwr.mm6448a3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Des Jarlais DC, Perlis T, Arasteh K, Torian LV, Beatrice S, Milliken J, Mildvan D, Yancovitz S, Friedman SR, 2005. HIV incidence among injection drug users in New York City, 1990 to 2002: use of serologic test algorithm to assess expansion of HIV prevention services. Am. J. Public Health 95, 1439–1444. 10.2105/AJPH.2003.036517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowsett LE, Coward S, Lorenzetti DL, MacKean G, Clement F, 2017. Living with Hepatitis C Virus: A Systematic Review and Narrative Synthesis of Qualitative Literature. Can. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol 2017, 3268650. 10.1155/2017/3268650 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Chaudoir SR, 2009. From conceptualizing to measuring HIV stigma: a review of HIV stigma mechanism measures. AIDS Behav. 13, 1160–1177. 10.1007/s10461-009-9593-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Amico KR, Copenhaver MM, 2013. HIV stigma mechanisms and well-being among PLWH: a test of the HIV stigma framework. AIDS Behav. 17, 1785–1795. 10.1007/s10461-013-0437-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser H, Vellozzi C, Hoerger TJ, Evans JL, Kral AH, Havens J, Young AM, Stone J, Handanagic S, Hariri S, Barbosa C, Hickman M, Leib A, Martin NK, Nerlander L, Raymond HF, Page K, Zibbell J, Ward JW, Vickerman P, 2019. Scaling Up Hepatitis C Prevention and Treatment Interventions for Achieving Elimination in the United States: A Rural and Urban Comparison. Am. J. Epidemiol 188, 1539–1551. 10.1093/aje/kwz097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedman SR, Pouget ER, Sandoval M, Rossi D, Mateu-Gelabert P, Nikolopoulos GK, Schneider JA, Smyrnov P, Stall RD, 2017. Interpersonal Attacks on the Dignity of Members of HIV Key Populations: A Descriptive and Exploratory Study. AIDS Behav. 21, 2561–2578. 10.1007/s10461-016-1578-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- GAIN, 2016. Global Appraisal of Individual Needs - Individual (GAIN-I) version [GVER]: 5.7.6.

- Gilchrist G, Swan D, Widyaratna K, Marquez-Arrico JE, Hughes E, Mdege ND, Martyn-St James M, Tirado-Munoz J, 2017. A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Psychosocial Interventions to Reduce Drug and Sexual Blood Borne Virus Risk Behaviours Among People Who Inject Drugs. AIDS Behav. 21, 1791–1811. 10.1007/s10461-017-1755-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giroir BP, 2020. The Time Is Now to End the HIV Epidemic. Am. J. Public Health 110, 22–24. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goffman E, 1963. Stigma: Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. Prentice Hall, Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. 10.1007/978-3-476-05728-0_9208-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hagan H, Thiede H, Des Jarlais DC, 2004. Hepatitis C Virus Infection among Injection Drug Users: Survival Analysis of Time to Seroconversion. Epidemiology 15, 543–549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JA, Page-Shafer K, Lum PJ, Bourgois P, Stein E, Evans JL, Busch MP, Tobler LH, Phelps B, Moss AR, 2002. Hepatitis C virus seroconversion among young injection drug users: relationships and risks. J. Infect. Dis 186, 1558–1564. 10.1086/345554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hahn JA, Page-Shafer K, Lum PJ, Ochoa K, Moss AR, 2001. Hepatitis C virus infection and needle exchange use among young injection drug users in San Francisco. Hepatology 34, 180–187. 10.1053/jhep.2001.25759 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hallum-Montes R, Morgan S, Rovito HM, Wrisby C, Anastario MP, 2013. Linking peers, patients, and providers: a qualitative study of a peer integration program for hard-to-reach patients living with HIV/AIDS. AIDS Care 25, 968–972. 10.1080/09540121.2012.748869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harling MR, Turner W, 2012. Student nurses’ attitudes to illicit drugs: a grounded theory study. Nurse Educ. Today 32, 235–240. 10.1016/j.nedt.2011.05.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG, 2013. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am. J. Public Health 103, 813–821. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens JR, Lofwall MR, Frost SDW, Oser CB, Leukefeld CG, Crosby RA, 2013. Individual and network factors associated with prevalent hepatitis C infection among rural Appalachian injection drug users. Am. J. Public Health 103, e44–52. 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens JR, Oser CB, Knudsen HK, Lofwall M, Stoops WW, Walsh SL, Leukefeld CG, Kral AH, 2011a. Individual and network factors associated with non-fatal overdose among rural Appalachian drug users. Drug Alcohol Depend. 115, 107–112. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2010.11.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Havens JR, Oser CB, Leukefeld CG, 2011b. Injection risk behaviors among rural drug users: implications for HIV prevention. AIDS Care 23, 638–645. 10.1080/09540121.2010.516346 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hay B, Henderson C, Maltby J, Canales JJ, 2017. Influence of Peer-Based Needle Exchange Programs on Mental Health Status in People Who Inject Drugs: A Nationwide New Zealand Study. Front. Psychiatry 7, 211. 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00211 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heckathorn DD, 1997. Respondent-Driven Sampling: A New Approach to the Study of Hidden Populations*. Soc. Probl 44, 174–199. 10.2307/3096941 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henderson C, Madden A, Kelsall J, 2017. “Beyond the willing & the waiting” - The role of peer-based approaches in hepatitis C diagnosis & treatment. Int. J. Drug Policy 50, 111–115. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2017.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu L, Bentler PM, 1999. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct. Equ. Model. A Multidiscip. J 6, 1–55. 10.1080/10705519909540118 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson-Best F, Edwards N, 2018. Stigma and intersectionality: a systematic review of systematic reviews across HIV/AIDS, mental illness, and physical disability. BMC Public Health 18, 919. 10.1186/s12889-018-5861-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services. Department for Public Health., 2020. HIV AIDS Surveillance Report, 2019 [WWW Document]. [Google Scholar]

- Knaak S, Mantler E, Szeto A, 2017. Mental illness-related stigma in healthcare: Barriers to access and care and evidence-based solutions. Healthc. Manag. Forum 30, 111–116. 10.1177/0840470416679413 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacombe-Duncan A, 2016. An Intersectional Perspective on Access to HIV-Related Healthcare for Transgender Women. Transgender Heal. 1, 137–141. 10.1089/trgh.2016.0018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster K, Seear K, Ritter A, 2017. Reducing stigma and discrimination for people experiencing problematic alcohol and other drug use. (Drug Policy Modelling Program Monograph Series; No. 26). National Drug and Alcohol Research Centre, Sydney NSW Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Latkin CA, Kuramoto SJ, Davey-Rothwell MA, Tobin KE, 2010. Social norms, social networks, and HIV risk behavior among injection drug users. AIDS Behav. 14, 1159–1168. 10.1007/s10461-009-9576-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lauckner HM, Hutchinson SL, 2016. Peer support for people with chronic conditions in rural areas: a scoping review. Rural Remote Health 16, 3601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lerner AM, Fauci AS, 2019. Opioid Injection in Rural Areas of the United States: A Potential Obstacle to Ending the HIV Epidemic. JAMA 322, 1041–1042. 10.1001/jama.2019.10657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levi-Minzi MA, Surratt HL, 2014. HIV stigma among substance abusing people living with HIV/AIDS: implications for HIV treatment. AIDS Patient Care STDS 28, 442–451. 10.1089/apc.2014.0076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link BG, Phelan JC, 2001. Conceptualizing Stigma. Annu. Rev. Sociol 27, 363–385. 10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.363 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Luoma JB, Twohig MP, Waltz T, Hayes SC, Roget N, Padilla M, Fisher G, 2007. An investigation of stigma in individuals receiving treatment for substance abuse. Addict. Behav 32, 1331–1346. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2006.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackinnon DP, Lockwood CM, Williams J, 2004. Confidence Limits for the Indirect Effect: Distribution of the Product and Resampling Methods. Multivariate Behav. Res 39, 99. 10.1207/s15327906mbr3901_4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madden EF, 2019. Intervention stigma: How medication-assisted treatment marginalizes patients and providers. Soc. Sci. Med 232, 324–331. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.05.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannarini S, Rossi A, 2018. Assessing Mental Illness Stigma: A Complex Issue. Front. Psychol 9, 2722. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02722 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marinho RT, Barreira DP, 2013. Hepatitis C, stigma and cure. World J. Gastroenterol 10.3748/wjg.v19.i40.6703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCutcheon JM, Morrison MA, 2014. Injecting on the Island: a qualitative exploration of the service needs of persons who inject drugs in Prince Edward Island, Canada. Harm Reduct. J 11, 10. 10.1186/1477-7517-11-10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinty EE, Barry CL, 2020. Stigma Reduction to Combat the Addiction Crisis — Developing an Evidence Base. N. Engl. J. Med 382, 1291–1292. 10.1056/NEJMp2000227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meade CS, McDonald LJ, Weiss RD, 2009. HIV risk behavior in opioid dependent adults seeking detoxification treatment: an exploratory comparison of heroin and oxycodone users. Am. J. Addict 18, 289–293. 10.1080/10550490902925821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muncan B, Walters SM, Ezell J, Ompad DC, 2020. “They look at us like junkies”: influences of drug use stigma on the healthcare engagement of people who inject drugs in New York City. Harm Reduct. J 17, 53. 10.1186/s12954-020-00399-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO, 2017. MPlus user’ guide.

- Neaigus A, Zhao M, Gyarmathy VA, Cisek L, Friedman SR, Baxter RC, 2008. Greater drug injecting risk for HIV, HBV, and HCV infection in a city where syringe exchange and pharmacy syringe distribution are illegal. J. Urban Health 85, 309–322. 10.1007/s11524-008-9271-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nyblade L, Stangl A, Weiss E, Ashburn K, 2009. Combating HIV stigma in health care settings: what works? J. Int. AIDS Soc 12, 15. 10.1186/1758-2652-12-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otachi JK, Vundi N, Surratt HL, 2020. Examining Factors Associated with Non-Fatal Overdose among People Who Inject Drugs in Rural Appalachia. Subst. Use Misuse 55, 1935–1942. 10.1080/10826084.2020.1781179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette CE, Pollini RA, 2018. Injection drug use, HIV/HCV, and related services in nonurban areas of the United States: A systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 188, 239–250. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2018.03.049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paquette CE, Syvertsen JL, Pollini RA, 2018. Stigma at every turn: Health services experiences among people who inject drugs. Int. J. Drug Policy 57, 104–110. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitpitan EV, Mittal ML, Smith LR, 2020. Perceived Need and Acceptability of a Community-Based Peer Navigator Model to Engage Key Populations in HIV Care in Tijuana, Mexico. J. Int. Assoc. Provid. AIDS Care 19, 1–8. 10.1177/2325958220919276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulerwitz J, Michaelis A, Weiss E, Brown L, Mahendra V, 2010. Reducing HIV-related stigma: lessons learned from Horizons research and programs. Public Health Rep. 125, 272–281. 10.1177/003335491012500218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pullen E, Oser C, 2014. Barriers to substance abuse treatment in rural and urban communities: counselor perspectives. Subst. Use Misuse 49, 891–901. 10.3109/10826084.2014.891615 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reddon H, Pettes T, Wood E, Nosova E, Milloy MJ, Kerr T, Hayashi K, 2018. Incidence and predictors of mental health disorder diagnoses among people who inject drugs in a Canadian setting. Drug Alcohol Rev. 37, S285–S293. 10.1111/dar.12631 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rural Health Information Hub, 2018. Substance Abuse in Rural Areas Introduction [WWW Document]. RHI Hub. URL https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/topics/substance-abuse (accessed 2.21.20). [Google Scholar]

- Saine ME, Szymczak JE, Moore TM, Bamford LP, Barg FK, Schnittker J, Holmes JH, Mitra N, Lo Re V III, 2020. Determinants of stigma among patients with hepatitis C virus infection. J. Viral Hepat 27, 1179–1189. 10.1111/jvh.13343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samoff E, Mobley V, Hudgins M, Cope AB, Adams ND, Caputo CR, Dennis AM, Billock RM, Crowley CA, Clymore JM, Foust E, 2020. HIV Outbreak Control With Effective Access to Care and Harm Reduction in North Carolina, 2017–2018. Am. J. Public Health 110, 394–400. 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayles JN, Ryan GW, Silver JS, Sarkisian CA, Cunningham WE, 2007. Experiences of social stigma and implications for healthcare among a diverse population of HIV positive adults. J. Urban Health 84, 814–828. 10.1007/s11524-007-9220-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schafer KR, Albrecht H, Dillingham R, Hogg RS, Jaworsky D, Kasper K, Loutfy M, MacKenzie LJ, McManus KA, Oursler KAK, Rhodes SD, Samji H, Skinner S, Sun CJ, Weissman S, Ohl ME, 2017. The Continuum of HIV Care in Rural Communities in the United States and Canada: What Is Known and Future Research Directions. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr 75, 35–44. 10.1097/QAI.0000000000001329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schranz AJ, Barrett J, Hurt CB, Malvestutto C, Miller WC, 2018. Challenges Facing a Rural Opioid Epidemic: Treatment and Prevention of HIV and Hepatitis C. Curr. HIV/AIDS Rep 15, 245–254. 10.1007/s11904-018-0393-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Slavova S, Rock P, Bush HM, Quesinberry D, Walsh SL, 2020. Signal of increased opioid overdose during COVID-19 from emergency medical services data. Drug Alcohol Depend. 214, 108176. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2020.108176 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith LR, Earnshaw VA, Copenhaver MM, Cunningham CO, 2016. Substance use stigma: Reliability and validity of a theory-based scale for substance-using populations. Drug Alcohol Depend. 16,(3Suppl, 34–43. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2016.02.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stangl AL, Grossman CI, 2013. Global Action to reduce HIV stigma and discrimination. J. Int. AIDS Soc 10.7448/IAS.16.3.18934 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton-Tindall M, Webster JM, Oser CB, Havens JR, Leukefeld CG, 2015. Drug use, hepatitis C, and service availability: perspectives of incarcerated rural women. Soc. Work Public Health 30, 385–396. 10.1080/19371918.2015.1021024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton M, Ciciurkaite G, Havens J, Tillson M, Leukefeld C, Webster M, Oser C, Peteet B, 2018. Correlates of Injection Drug Use Among Rural Appalachian Women. J. Rural Heal 34, 31–41. 10.1111/jrh.12256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strike C, Watson TM, Gohil H, Miskovic M, Robinson S, Arkell C, Challacombe L, 2015. Best practice recommendations for Canadian harm reduction programs that provide service to people who use drugs and are at risk for HIV, HCV, and other harms-part 2: Service models, referrals for services, and emerging areas of practice. Can. J. Infect. Dis. Med. Microbiol 26, 148. [Google Scholar]

- Stringer KL, Mukherjee T, McCrimmon T, Terlikbayeva A, Primbetovac S, Darisheva M, Hunt T, Gilbert L, El-Bassel N, 2019. Attitudes towards people living with HIV and people who inject drugs: A mixed method study of stigmas within harm reduction programs in Kazakhstan. Int. J. Drug Policy 68, 27–36. 10.1016/j.drugpo.2019.02.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stringer KL, Turan B, McCormick L, Durojaiye M, Nyblade L, Kempf M-C, Lichtenstein B, Turan JM, 2016. HIV-Related Stigma Among Healthcare Providers in the Deep South. AIDS Behav. 20, 115–125. 10.1007/s10461-015-1256-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surratt HL, Cowley AM, Gulley J, Lockard AS, Otachi J, Rains R, Williams TR, 2020a. Syringe Service Program Use Among People Who Inject Drugs in Appalachian Kentucky. Am. J. Public Health 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surratt HL, Staton M, Leukefeld CG, Oser CB, Webster JM, 2018. Patterns of buprenorphine use and risk for re-arrest among highly vulnerable opioid-involved women released from jails in rural Appalachia. J. Addict. Dis 37, 1–4. 10.1080/10550887.2018.1531738 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Surratt HL, Staton MC, Vundi N, 2020b. Expanding Access to HIV testing and diagnosis among people who inject drugs in high HIV burden areas of the rural United States, International Aids Conference. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai AC, Kiang MV, Barnett ML, Beletsky L, Keyes KM, McGinty EE, Smith LR, Strathdee SA, Wakeman SE, Venkataramani AS, 2019. Stigma as a fundamental hindrance to the United States opioid overdose crisis response. PLoS Med. 16, e1002969. 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Boekel LC, Brouwers EPM, van Weeghel J, Garretsen HFL, 2013. Stigma among health professionals towards patients with substance use disorders and its consequences for healthcare delivery: systematic review. Drug Alcohol Depend. 131, 23–35. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.02.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Handel MM, Rose CE, Hallisey EJ, Kolling JL, Zibbell JE, Lewis B, Bohm MK, Jones CM, Flanagan BE, Siddiqi A-E-A, Iqbal K, Dent AL, Mermin JH, McCray E, Ward JW, Brooks JT, 2016. County-Level Vulnerability Assessment for Rapid Dissemination of HIV or HCV Infections Among Persons Who Inject Drugs, United States. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr 73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogt RL, Breda MC, Des Jarlais DC, Gates S, Whiticar P, 1998. Hawaii’s statewide syringe exchange program. Am. J. Public Health 88, 1403–1404. 10.2105/ajph.88.9.1403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Hippel C, Brener L, Horwitz R, 2018. Implicit and explicit internalized stigma: Relationship with risky behaviors, psychosocial functioning and healthcare access among people who inject drugs. Addict. Behav 76, 305–311. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2017.08.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson H, Brener L, Mao L, Treloar C, 2014. Perceived discrimination and injecting risk among people who inject drugs attending Needle and Syringe Programmes in Sydney, Australia. Drug Alcohol Depend. 144, 274–278. 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.08.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang LH, Wong LY, Grivel MM, Hasin DS, 2017. Stigma and substance use disorders: an international phenomenon. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 30, 378—388. 10.1097/yco.0000000000000351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young AM, Jonas AB, Mullins UL, Halgin DS, Havens JR, 2013. Network structure and the risk for HIV transmission among rural drug users. AIDS Behav. 17, 2341–2351. 10.1007/s10461-012-0371-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zibbell JE, Iqbal K, Patel RC, Suryaprasad A, Sanders KJ, Moore-Moravian L, Serrecchia J, Blankenship S, Ward JW, Holtzman D, 2015. Increases in hepatitis C virus infection related to injection drug use among persons aged ≤30 years - Kentucky, Tennessee, Virginia, and West Virginia, 2006–2012. Morb. Mortal. Wkly. Rep 64, 453–458. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]