Abstract

The paradigm for treatment of PDAC is shifting from a “one size fits all” of cytotoxic therapy to a precision medicine approach based on specific predictive biomarkers for a subset of patients. As the genomic landscape of pancreatic carcinogenesis has become increasingly defined, several oncogenic alterations have emerged as actionable targets and their use has been validated in novel approaches such as targeting mutated germline DNA damage response genes (BRCA) and mismatch deficiency (dMMR/MSI-H) or blockade of rare somatic oncogenic fusions. Chemotherapy selection based on transcriptomic subtypes and developing stroma- and immune-modulating strategies have yielded encouraging results and may open therapeutic refinement to a broader PDAC population. Notwithstanding, a series of negative late-stage trials over the last year continue to underscore the inherent challenges in the treatment of PDAC. Multifactorial therapy resistance warrants further exploration in PDAC ‘omics’ and tumor-stroma-immune cells crosstalk. Herein, we discuss precision medicine approaches applied to the treatment of PDAC, its current state and future perspective.

Keywords: pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma, precision medicine, somatic, germline, targeted therapy, KRAS, BRCA

Introduction

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) is an aggressive malignancy with limited survival. Despite a comparatively low incidence of 57,600 cases/year in the United States [1], it is projected to become the second leading cause of cancer death within a decade, surpassing more common neoplasia including breast, prostate and colorectal cancers [2]. This estimation is based on the late clinical presentation and relative resistance to current standard treatments, along with the stagnant development of validated predictive biomarkers and relatively low success of novel therapeutic strategies. Indeed, approximately 50% of PDAC are typically diagnosed at advanced stage, where a traditional “one size fits all” chemotherapy is typically delivered irrespective of biomarker or patient selection factors. The last two decades of innovation have substantially deepened our understanding of PDAC genomics, the tumor microenvironment (TME) and the disease immune landscape, albeit these observations have yet to be translated into major improvements in outcome. As opposed to certain types of leukemias that originate from a single driver mutation, PDAC arises from a multiplicity of tumorigenic pathways which harbor potentially actionable somatic and germline alterations. Thus, the genetic diversity of PDAC opens to a plausible therapeutic point of inflection: precision medicine based on individualized tumor profiling. The review herein aims (1) to outline relevant developments in the characterization of the molecular profiling of PDAC, and (2) to highlight major new therapeutic directions including approved and developing targeted agents along with their corresponding predictive biomarkers.

1. Somatic Mutational Landscape of PDAC

In 2008, Jones et al. conducted the first exome-wide sequencing on PDAC tissues and observed a heterogenous genomic landscape comprised of genetic alterations implicated in twelve candidate tumorigenic pathways [3]. Subsequent studies supported these findings and identified the four most frequently mutated albeit as yet non-targetable somatic genes: mutated Kirsten rat sarcoma viral oncogene homolog (K-Ras) in over 90% of patients, followed by TP53, mothers against decapentaplegic homolog 4 (SMAD4), and cyclin dependent kinase inhibitor 2A (CDKN2A) [4–6]. Following these core driver mutations, there is a series of less frequently recurring mutated genes implicated in diverse pathways including DNA damage repair (DDR) and chromatin modification. Finally, there is a long tail of rarely altered genes and copy number variations that lead to significant intertumoral heterogeneity and abundance of redundant mechanisms implicated in treatment resistance [4–6]. These latter observations may explain the relative favorable outcome of non-selected cytotoxic therapy, as opposed to the comparatively low success of agents targeting one specific pathway.

Collisson et al. analyzed the global gene expression of 27 PDAC samples and observed three transcriptional subgroups: classical, quasi-mesenchymal, and exocrine-like [7]. Retrospective studies with larger cohorts subsequently confirmed the feasibility of PDAC molecular subtyping and provided additional supporting findings (Table 1) [8–11]. Proposed transcriptional subtypes displayed unique gene signatures that were validated across independent cohorts (Figure 1). For instance, Collisson’s classical subtype overlapped with Moffitt’s classical and Bailey’s pancreatic progenitor subtypes [7, 10, 11]. The classical subtype exhibits high expression of epithelial and adhesion genes, as well as GATA-binding protein 6 (GATA6) and KRAS, both implicated in pancreatic tumorigenesis. Whereas, quasi-mesenchymal correlated with squamous subtype in Bailey’s study, and displayed upregulation in genes involved in inflammation, hypoxia response, MYC, and TP53 [11]. The classical subtype had significantly longer median overall survival (mOS) compared to quasi-mesenchymal subgroup: 26.2 months vs 10.1 months (P=0.038) respectively in the Collisson et al. study, and 25.6 months vs 13.3 months (P=0.03) in the Bailey et al. cohort [7, 11]. Of clinical significance, transcriptional signatures served as biomarkers for therapy response: the classical subtype correlated with better response to epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitors (i.e., erlotinib), while the quasi-mesenchymal subtype was more sensitive to gemcitabine [7]. Translating directly to practice, the COMPASS trial enrolled advanced PDAC patients whose tumor tissue and blood collected prior to therapy were analyzed by whole genome sequencing and RNA sequencing [12]. In this study, a higher objective response rate (ORR) of 33% (confidence interval [CI] not reported) was observed in classical PDAC treated with modified FOLFIRINOX (5-fluorouracil/oxaliplatin/leucovorin/irinotecan) (mFOLFIRINOX), as opposed to an ORR of 10% in the basal-like subtype (P=0.02) [13]. GATA6 expression was significantly correlated with transcriptional subtypes (P<0.001) and distinguished classical from basal-like PDAC when detected by in situ hybridization (sensitivity 89%, specificity 83%) or by immunohistochemistry (IHC) (sensitivity 83%, specificity 60%). The upcoming PASS-01 trial will compare the efficacy of the two current standard regimens for patients with metastatic PDAC (mPDAC), FOLFIRINOX and gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel (GnP), and retrospectively examine treatment responses based on subtypes, gene expression signatures including GATA6, and other tissue and blood correlates (NCT04469556).

Table 1.

Approaches to Molecular Classification of Pancreas Cancer

| Reference | Molecular Subtypes | Median Survival (months) | Analytic Methodology | Tissue Source | Additional Comments |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collisson et al. [7] | Classical |

26.2 |

– Global RNA microarray analysis – NMF analysis with consensus clustering |

– Microdissected PDAC material (N=27) – Human PDAC cell lines (N=19) – Murine PDAC cell lines (N=15) |

– Exocrine-like subtype concerned for nontumoral tissue contamination – Classical constitute better prognosis, more responsive to erlotinib – Gemcitabine more sensitive in Quasi-mesenchymal |

| Quasi-mesenchymal |

10.1 |

||||

| Exocrine-like |

18.8 |

||||

|

| |||||

| Waddell et al. [9] | Stable |

NA |

– Array-based CNV analysis – WES |

– PDAC samples (N=75) – Cell lines (N=25) |

– Subtypes based on variation in chromosomal structure – Genomic instability and BRCA mutational signature as biomarker for platinum therapy and PARPi |

| Locally rearranged |

NA |

||||

| Scattered |

NA |

||||

| Unstable |

NA |

||||

|

| |||||

| Moffitt et al. [10] | Tumor-specific “classical” subtype |

19 |

– Whole genome DNA microarrays – RNA-based sequencing |

– DNA microarrays: – Primary PDAC samples (N=145) – mPDAC tumors (N=61) – Cell lines (N=17) – Normal pancreatic tissue (N=46) – Normal tissue adjacent to metastatic sites (N=88) – RNA sequencing: – Primary tumors (N=15) – Pancreatic PDX (N=37), – Cell lines (N=3) – CAF (N=6) |

– Applied virtual microdissection using NMF – Added stroma-specific subtypes – Suggested Collisson et al. exocrine subtype was due to contamination |

| Tumor-specific “basal-like” subtype |

11 |

||||

| Stroma-specific “normal” subtype |

24 |

||||

| Stroma-specific “activated” subtype |

15 |

||||

|

| |||||

| Bailey et al. [11] | Squamous |

13.3 |

– WES when tumor cellularity was >40% – Deep-exome sequencing for sample cellularity of 12–40% – RNA sequencing – CNV analysis with SNP BeadChips |

– Pancreatic cancer including variants* (N=382) – Previously published PC exomes (N=74) |

– Subtypes correlated with specific histological features – Subtypes correlated with Collisson et al. study – Introduced immunogenic type – 9% had DDR pathway mutations |

| Pancreatic progenitor |

25.6 |

||||

| Immunogenic |

30 |

||||

| ADEX |

23.7 |

||||

|

| |||||

| Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network [8] | basallike/squamous |

NA |

– WES and SNP microarrays for recurrent somatic mutations and copy number aberrations – Matched germline exome sequencing data – DNA methylation analysis |

– Primary PDAC and matched germline DNA from whole blood (N=150) | – 8% had pathogenic germline mutation – 10% had somatic or germline mutations affecting DDR genes – Prior immunogenic, ADEX and exocrine-like subtypes were likely contaminant |

| classical/progenitor |

NA |

||||

|

| |||||

Variants included PDAC and subtypes adenosquamous, colloid, IPMN and rare acinar cell carcinomas

Abbreviations: ADEX, aberrantly differentiated endocrine exocrine; CAF, cancer-associated fibroblast; CNV, copy number variation; DDR, DNA damage response; IPMN, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasm; mPDAC, metastatic pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; NMF, nonnegative matrix factorization; PARPi, poly-ADP ribose polymerase inhibitor; PDX, patient-derived xenografts; WES, whole exome sequencing.

Figure 1.

Molecular Classifications of Pancreas Cancer. Outer ring represents transcriptional subtypes from selective pancreatic cancer sequencing cohorts. Inner ring compiles main similarities in gene expressions amongst the subtypes. Abbrev. ADEX, aberrantly differentiated endocrine exocrine.

2. Germline Alterations in PDAC

In addition to environmental risk factors, acquired somatic mutations, and other unknown factors, inherited germline mutations contribute to PDAC development [14]. Germline pathogenic variants (GPVs) are identified in 5–19% of PDACs and may participate in early pancreatic carcinogenesis and in KRAS-independent pathways [9, 15–17]. Many GPVs are implicated in DNA damage response (DDR) and chromosomal stability, specifically, loss-of-function mutations of BRCA1/2 or PALB2 in 5–9% of PDACs are associated with increased tumor sensitivity to DNA-damaging agents [18, 19]. This provided rationale for PDAC trials with platinum regimens and poly-ADP-ribose polymerase (PARP) inhibitors (PARPi) [20, 21]. GPVs were also detected in patient with PDAC with none or a limited family history of pancreatic malignancy; conversely, in 80% of patients with a positive family history, the genetic predisposition remains unknown [17, 22, 23]. The recently updated American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) guideline recommends somatic and germline testing as initial assessment for all patient with a diagnosis of PDAC, in order to ensure readily available results at the time of treatment decision making (type: informal consensus; strength of recommendation: strong) (Table 3) [24].

Table 3.

Minimum Recommended Testing Panel for Somatic and Germline Alterations in Pancreas Cancer

| Somatic Alterations | Germline Alterations | Under Investigation |

|---|---|---|

| • KRAS, BRCA1, BRCA2, HER2, PALB2 | BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, ATM, MLH1, MSH2, MSH6, EPCAM, CDKN2A, and TP53 | BAP1, BARD1, BRIP1, BLM, CHEK2, CDK4, FAM175A, FANCA, FANCC, FANCD, FANCE, FANCF, MRE11A, NBN, PMS2, RAD51C, and RAD51D |

| • In KRAS wild type, to include gene fusions (ALK, NRG1, NTRK, ROS1) and alterations (RET, FGFR, BRAF and EGFR) | ||

| • MMR deficiency and MSI status | ||

|

| ||

Abbrev. MSI, microsatellite instability. MMR, mismatch repair.

3. Biomarkers and Targeted Therapy

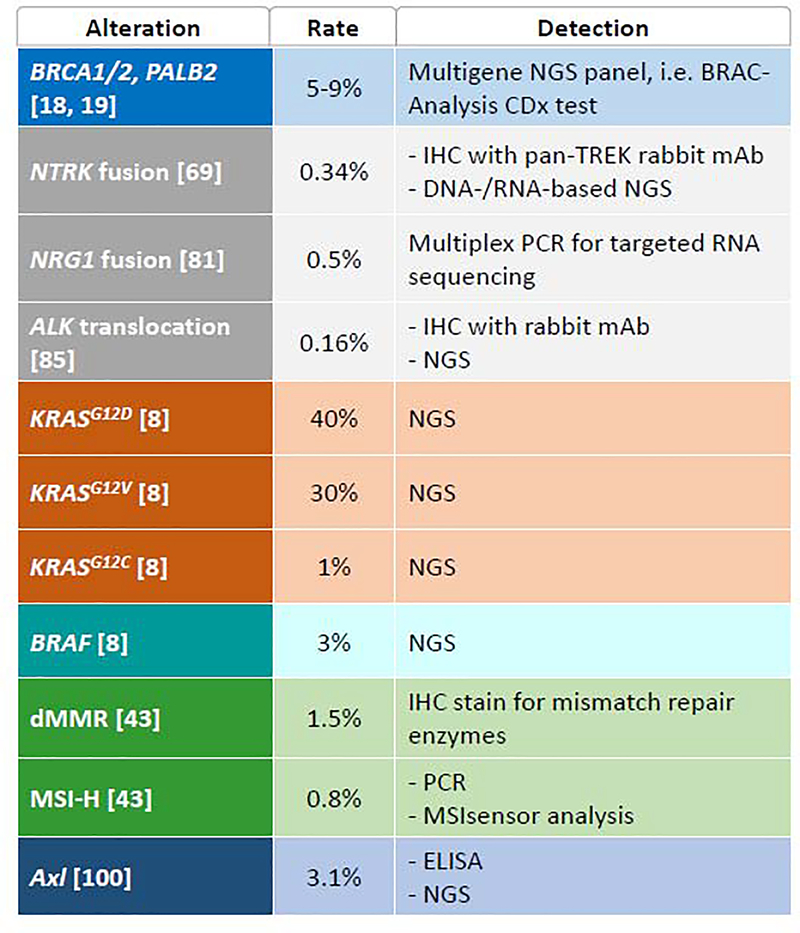

Continued effort in PDAC ‘omics’ exploration has demonstrated potentially actionable molecular alterations in 20–25% of patients [25]. In the two years since the last update, the 2020 American Society of Clinical Oncology (ASCO) mPDAC guideline incorporated two new targeted therapeutic approaches: PARPi, given the successful POLO (Pancreas OLaparib Ongoing) trial in germline BRCA patients, and NTRK inhibitors [24]. To follow we summarize key actionable pathways in PDAC, their corresponding biomarkers as well as approved and developing targeted agents (Figure 2) (Table 4).

Figure 2a.

Selective Targeted Approaches in Development for the treatment of Pancreas Cancer. Inner circle represents key potentially actionable pathways implicated in pancreatic tumorigenesis. Outer color-coded squares contain specifically targeted mutations, followed by key therapeutic agents in development. 2b. Key Genomic Alterations, Prevalence and Overview of Detection Methods. *Approximate detection rate based on published cohorts. Abbreviations. CTGF, connective tissue growth factor. dMMR, mismatch repair-deficiency. HCQ, hydroxychloroquine. IHC, immunohistochemistry. mAb, monoclonal antibody. MSI-H, microsatellite instability-high. NGS, next generation sequencing. PBL, peripheral blood lymphocyte. PCR, polymerase chain reaction.

Table 4.

Ongoing Registered Clinical Trials Evaluating Experimental Agents Targeting Specific Genetic Alterations or Pathways in Pancreas Cancer

| NCT Identifier | Phase | Status | Tested Specific Biomarker | Experimental arm | Control arm | Primary Endpoints | Targeted population | Estimated completion date |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Damage Response Pathway^ | ||||||||

| NCT03140670 | 2 | Active, not recruiting | BRCA1/2 or PALB2 | Rucaparib | None | AE | PDAC, locally advanced or metastatic | June 1, 2022 |

| NCT04171700 | 2 | Recruiting | BRCA1, BRCA2, PALB2, RAD51C, RAD51D, BARD1, BRIP1, FANCA, NBN, RAD51 or RAD51B | Rucaparib | None | ORR | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | May 2022 |

| NCT03337087 | 1/2 | Recruiting | Phase 1 only:BRCA1/2, PALB2 Phase 2 only: genomic markers of HRD, BRCA1/2 or PALB2 mutation |

5-FU plus irinotecan plus leucovorin plus rucaparib | None | MTD, DLT, ORR | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | July 1, 2022 |

| NCT03601923 | 2 | Recruiting | Somatic or germline mutations of BRCA1/2, PALB2, CHEK2 or ATM | Niraparib | None | PFS | PDAC, locally advanced or metastatic | February 28, 2025 |

| NCT03553004 | 2 | Recruiting | Germline or somatic mutation in genes involved in DNA repair (gene list not provided) | Niraparib | None | ORR | PDAC, stage IV | February 1, 2025 |

| NCT03404960 | 1/2 | Recruiting | N/A | Niraparib plus nivolumab or ipilimumab | None | PFS | PDAC, locally advanced or metastatic | June 2021 |

| NCT02498613 | 2 | Recruiting | HER2 | cediranib plus olaparib | None | ORR | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | December 31, 2020 |

| NCT04005690 | 1 | Recruiting | N/A | Cobimetinib or olaparib | None | Feasibility of collecting tumor tissue for biomarker evaluation prior to treatment | PDAC, locally advanced or metastatic | February 1, 2025 |

| NCT04550494 | 2 | Not yet recruiting | N/A | Talazoparib | None | PD | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | August 1, 2022 |

| NCT03851614 | 2 | Recruiting | N/A | Durvalumab plus cediranib or olaparib | None | Changes in genomic and immune biomarkers | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | March 1, 2022 |

| NCT03682289 | 2 | Recruiting | ARID1A, ATM | AZD6738 +/− olaparib | None | ORR | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | March 19, 2023 |

| NCT03637491 | 1/2 | Recruiting | N/A | Binimetinib +/− avelumab +/− talazoparib | None | DLT, ORR | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | November 28, 2024 |

| Immune Modulating Agents | ||||||||

| NCT03006302 | 2 | Recruiting | N/A | Arm A: epacadostat, pembrolizumab, cyclophosphamide, GVAX Arm B: epacadostat, pembrolizumab, CRS-207 |

None | Recommended dose, 6-month survival | PDAC, stage IV | June 2023 |

| NCT03264404 | 2 | Recruiting | N/A | Azacitidine plus pembrolizumab | None | PFS | PDAC, locally advanced or metastatic | September 2020 |

| NCT02907099 | 2 | Active, not recruiting | N/A | Pembrolizumab and CXCR4 Antagonist BL-8040 | None | ORR | PDAC, stage IV | December 31, 2022 |

| NCT04007744 | 1 | Recruiting | N/A | Sonidegib plus pembrolizumab | None | MTD, ORR | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | July 31, 2021 |

| NCT03723915 | 2 | Active, not recruiting | N/A | Pembrolizumab and Pelareorep | None | ORR | PDAC, locally advanced or metastatic | June 15, 2021 |

| NCT02600949 | 1 | Recruiting | N/A | Synthetic Tumor-Associated Peptide Vaccine Therapy plus pembrolizumab plus imiquimod | None | DLT, proportion of patients that receives personalized vaccine | Metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | May 31, 2021 |

| NCT03214250 | 1/2 | Active, not recruiting | N/A | GnP +/− nivolumab +/− APX005M | None | AE, OS | PDAC, stage IV | September 1, 2022 |

| NCT03190265 | 2 | Recruiting | N/A | Nivolumab plus ipilimumab plus CRS-207 +/− cyclophosphamide and GVAX pancreas vaccine | None | ORR | PDAC, stage IV | October 2023 |

| NCT02879318 | 2 | Active, not recruiting | N/A | GnP plus durvalumab plus tremelimumab | GnP | ORR | PDAC, stage IV | June 30, 2021 |

| NCT03454451 | 1 | Recruiting | N/A | CPI-006 +/− pembrolizumab +/− ciforadenant | None | DLT, AE, MTD | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | December 2023 |

| NCT03207867 | 2 | Recruiting | N/A | NIR178 plus PDR001 | None | ORR | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | December 1, 2021 |

| NCT03884556 | 1 | Recruiting | N/A | TTX-030 +/− pembrolizumab +/− docetaxel +/− GnP | None | RP2D | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | March 2022 |

| NCT04050085 | 1 | Recruiting | N/A | Nivolumab plus radiation plus TLR9 Agonist SD-101 | None | AE | PDAC, stage IV | November 5, 2021 |

| KRAS-Targeted Therapy | ||||||||

| NCT04185883 | 1b | Recruiting | KRASG12C | AMG 510 (sotorasib) plus additional agents* | None | AE, DLT, changes in vital signs and laboratory test values | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | June 1, 2026 |

| NCT03600883 | 1/2 | Recruiting | KRASG12C | AMG 510 (sotorasib) | None | ORR, changes in vital signs and laboratory test values | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | March 31, 2024 |

| NCT03785249 | 1/2 | Recruiting | KRASG12C | MRTX849 alone, or with pembrolizumab, cetuximab or afatinib | None | ORR, PK, AE | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | September 2021 |

| NCT03608631 | 1 | Not yet recruiting | KRASG12D | Mesenchymal Stromal Cells-derived Exosomes with KRASG12D siRNA | None | MTD, OS, PFS, minimal residual disease rate | PDAC, stage IV | March 2022 |

| NCT01676259 | 2 | Active | KRAS G12D | siG12D-LODER plus chemotherapy | None | PFS | PDAC, locally advanced | Pending update$ |

| NCT04330664 | 1/2 | Recruiting | KRAS G12C | MRTX849 plus TNO155 | None | Safety, PK | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | October 2022 |

| NCT03745326 | 1/2 | Recruiting | KRASG12D> | anti-KRASG12D mTCR PBL, Fludarabine, Cyclophosphamide, Aldesleukin | None | DLT, ORR | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | December 1, 2028 |

| NCT03190941 | 1/2 | Recruiting | KRAS G12V | anti-KRASG12V mTCR PBL, Fludarabine, Cyclophosphamide, Aldesleukin | None | DLT, ORR | Metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | June 29, 2028 |

| NCT03948763 | 1 | Recruiting | KRAS mutation at codons G12D, G12V, G13D or G12C | V941(mRNA-5671/V941) +/− pembrolizumb | None | DLT, AE, discontinuation rate | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | November 19, 2026 |

| Specific Mutation or Oncogenic Fusion | ||||||||

| NCT02912949 | 1/2 | Recruiting | NRG1 fusion, HER2/3 | Zenocutuzumab (MCLA-128) | None | AE, DOR, ORR, correlation of antitumor activity and biomarker | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | September 2022 |

| NCT02568267 | 2 | Recruiting | NTRK1/2/3, ROS1, or ALK gene fusion | Entrectinib (RXDX-101) | None | ORR | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | December 2, 2024 |

| NCT03093116 | 1/2 | Recruiting | NTRK1/2/3, ROS1, ALK | Repotrectinib | None | DLT, RP2D, ORR | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | December 2022 |

| NCT04094610 | 1/2 | Recruiting | NTRK1/2/3, ROS1, ALK | Repotrectinib | None | DLT, RP2D, ORR | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | December 2023 |

| NCT02395016 | 3 | Unknown | EGFR | Nimotuzumab plus Gemcitabine | Gemcitabine | OS | PDAC, locally advanced or metastatic | Unknown |

| NCT02451553 | 1/1b | Recruiting | EGFR/HER2 | Afatinib + Capecitabine | None | AE, DLT, MTD, RP2D | Advanced refractory pancreatic and biliary cancer | September 30, 2022 |

| NCT04390243 | 2 | Not yet recruiting | BRAFV600E | Binimetinib plus encorafenib | None | ORR | PDAC, stage IV | December 29, 2024 |

| NCT02546531 | 1 | Active, not recruiting | FAK | Defactinib plus pembrolizumab, with or without gemcitabine | None | RP2D, MTD | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | July 31, 2021 |

| NCT02758587 | 1/2 | Recruiting | FAK | Defactinib plus pembrolizumab | None | AE | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | December 2021 |

| NCT02428270 | 2 | Active, not recruiting | FAK, MEK1/2 | GSK2256098 and Trametinib | None | ORR | PDAC, locally advanced or metastatic | September 2021 |

| NCT03649321 | 1/2 | Recruiting | Axl | Bemcentinib plus GnP plus cisplatin | GnP plus cisplatin | Complete response rate | PDAC, stage IV | July 2022 |

| NCT03086369 | 1b/2 | Active, not recruiting | PDGFR-a | Olaratumab plus GnP | GnP | DLT, OS | PDAC, stage IV | August 30, 2022 |

| Autophagy | ||||||||

| NCT01506973 | 1/2 | Active, not recruiting | N/A | Hydroxychloroquine plus GnP | None | OS | PDAC, locally advanced or metastatic | March 2021 |

| NCT03825289 | 1 | Recruiting | N/A | Hydroxychloroquine plus trametinib | None | DLT, RP2D | PDAC, stage II to IV | January 18, 2025 |

| NCT04132505 | 1 | Recruiting | N/A | Hydroxychloroquine plus binimetinib | None | MTD | PDAC, stage IV | May 31, 2020 |

| NCT04214418 | 1/2 | Recruiting | N/A | Cobimetinib plus Hydroxychloroquine plus Atezolizumab | None | MTD | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | September 2023 |

| Stroma-Modulating Agents | ||||||||

| NCT03941093 | 3 | Recruiting | CTGF | Pamrevlumab plus GnP | GnP | OS, resection rate | PDAC, locally advanced | December 2023 |

| NCT03415854 | 2 | Active, not recruiting | Vitamin D receptor | Paricalcitol, cisplatin, GnP | None | Pathologic complete response rate | PDAC, stage IV | December 31, 2020 |

| NCT03520790 | 1/2 | Active, not recruiting | N/A | Paricalcitol and GnP | GnP | AE, OS | PDAC, stage IV | November 30, 2025 |

| Metabolism | ||||||||

| NCT03504423 | 3 | Recruiting | N/A | CPI-613 (devimistat) plus modified FOLFIRINOX | FOLFIRINOX | ORR, PFS | PDAC, stage IV | June 2021 |

| NCT03665441 | 3 | Recruiting | N/A | Eryaspase plus GnP or irinotecan/5-FU | GnP or irinotecan/5-FU | OS | PDAC, locally advanced or metastatic | October 2021 |

| Transcriptional Subtype-Directed Therapy | ||||||||

| NCT04469556 | 2 | Not yet recruiting | GATA6 | FOLFIRINOX | GnP | PFS | PDAC, stage IV | August 2023 |

| Adaptative Clinical Trials | ||||||||

| NCT03193190 | 1b/2 | Recruiting | Multiple biomarkers | Multiple agents | None | ORR, AE | PDAC, stage IV | November 3, 2021 |

| NCT02465060 | 2 | Recruiting | Multiple biomarkers | Multiple agents | None | ORR | Advanced refractory solid tumors, lymphomas, or multiple myeloma | June 30, 2022 |

| NCT04229004 | 3 | Recruiting | N/A | SM-88 with methoxsalen, phenytoin, and sirolimus | GnP and mFOLFIRINOX | OS | PDAC, stage IV | February 20, 2024 |

| NCT02925234 | 2 | Recruiting | Multiple biomarkers | 27 agents | None | Percentage of patients who received selective targeted therapy, ORR, AE | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | December 2022 |

| NCT02693535 | 2 | Recruiting | Multiple biomarkers | 13 agents | None | ORR | Locally advanced or metastatic solid tumor including PDAC | December 31, 2023 |

combinational regimens may include experimental agents targeting various actionable pathways

including PD-1/L1 inhibitor, MEK inhibitor, SHP2 allosteric inhibitor, Pan-ErbB tyrosine kinase inhibitor, EGFR inhibitor or chemotherapy

Study design had been modified to single arm without comparator, awaiting information update on clinicaltrials.gov

Abbrev. 5-FU, fluorouracil. AE, adverse events. DLT, dose limiting toxicity. DOR, duration of response. GnP, gemcitabine and nab-paclitaxel. HRD, homologous recombination deficiency. MTD, maximum tolerated dose. mTR, murine T-cell receptor. ORR, objective response. OS, overall survival. PBL, peripheral blood lymphocytes. PD, pharmacodynamic. PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. PFS, progression-free survival. PK, pharmacokinetics. RP2D, recommended phase 2 dose. siRNA, small interference RNA.

3.1. DNA Damage Response

Based on the frequency and types of structural variations, Waddell et al. proposed four PDAC subtypes: stable, locally rearranged, scattered, and unstable subtypes (Table 1) [9]. This latter type was characterized by highly recurrent structural variation events due to somatic and germline mutations of DDR genes, including ATM, BRCA1/2, and PALB2. The BRCA1/2 genes encode key proteins involved in the repair of DNA double-strand breaks (DSB) by homologous recombination (HR) [26], while PALB2 binds and recruits BRCA2 and RAD51 to DNA break locations [27]. While incompletely understood, it is hypothesized that PARP inhibition may prevent the repair of DNA single-strand breaks, which combined with DSB leads to synthetic lethality of tumor cells [28].

3.1.1. DDR and PARP Inhibition

In a multicenter phase 2 study that enrolled patients with ovarian, breast, prostate and PDAC germline BRCA1/2-mutations, the oral PARPi olaparib showed antitumor activity regardless of tumor type or type of BRCA mutation (ORR (overall Response Rate) 26.2%, 95% CI 21.3–31.6) [29]. In the PDAC cohort of 23 patients with advanced disease, five (ORR 21.7%, 95% CI 7.5–43.7) had an objective response, including one complete response (CR) and four partial responses (PR). In the phase 3 POLO trial, maintenance olaparib was studied in patients with mPDAC who had stable or responding disease after ≥ 16 weeks of first-line platinum-based chemotherapy [20]. Olaparib demonstrated a significantly longer median progression-free survival (mPFS) compared to placebo (7.4 vs 3.8 months, respectively: HR 0.53, 95% CI 0.35–0.82, P=0.004). At 46% data maturity, no difference was observed in mOS (18.9 months with olaparib vs 18.1 months with placebo; HR 0.91, 95% CI, 0.56–1.46, P=0.68) [20]. This trial confirmed the safety and benefit of maintenance olaparib as a novel therapeutic approach for PDAC harboring germline BRCA-mutations and led to its Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approval in December 2019 [30]. Nonetheless, critiques included the lack of an “active” chemotherapy control arm and absence of survival benefit from the initial report. Updated survival data are anticipated in 2021.

Beyond olaparib, other PARPi have been studied actively in patients with PDCA harboring BRCA mutations. The phase 2 RUCAPANC study with rucaparib in patients with locally advanced or metastatic PDAC was terminated due to futility: interim analyses with 19 patients showed limited ORR in three (15.8%, 95% CI 3.4–39.6) patients including one with a somatic BRCA mutation, albeit responses were durable (≥ 12 weeks) [31]. In retrospect this trial was probably terminated inadvertently early. Veliparib monotherapy did not demonstrate any objective response in a phase 2 trial with 16 patients with stage III/IV PDAC with germline PALB2 or BRCA1/2 mutation, although disease in four (25%) patients remained stable (SD) for ≥ 4 months [32]. Notably, most patients had platinum resistance, likely in part accounting for the limited signal.

Combination strategies with PARPi are being explored. Preclinically, PARPi plus immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) have led to synergistic antitumoral effect via accumulation of tumor neoantigens and upregulation of interferon pathways [33, 34], and their safety and efficacy in locally advanced and mPDAC are currently under evaluation in early phase studies (NCT03637491, NCT03404960, NCT03851614). ATR kinase-mediated DDR pathways are hypothesized to promote tumor survival under PARP inhibition, and the ATR-inhibitor AZD6738 (ceralasertib) plus olaparib demonstrated synergistic tumor suppression in preclinical models [35]. The efficacy of AZD6738 with/without olaparib is being examined in a phase 2 trial with stage III/IV solid tumors including PDAC (NCT03682289). PARPi may also decrease tumor angiogenesis by suppressing endothelial cell migration [36]. Olaparib combined with the anti-VEGF agent, cediranib, is being studied in advanced malignancies including PDAC (NCT02498613). Combined PARP and MEK inhibition is being investigated both in neoadjuvant (olaparib/cobimetinib, NCT04005690) and advanced settings (talazoparib/binimetinib/avelumab, NCT03637491).

The Myriad Genetic Laboratories BRAC-Analysis CDx test is currently approved by the FDA as a companion diagnostic to identify patients with PDAC harboring a BRCA 1/2 mutation [37]. This test applies polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and Sanger sequencing to detect single nucleotide variants and small insertions and deletions, as well as multiplex PCR to identify large deletions and duplications in the BRCA genes. Beyond BRCA 1/2, ongoing clinical trials are exploring predictive values of moderate-penetrance DDR genes (e.g., ARID1A, ATM, ATRX, CHEK2, and RAD51 amongst others) in patients treated with PARPi (NCT03601923, NCT04171700, NCT04550494) (Table 4).

3.1.2. DDR and Platinum-Based Chemotherapy

‘Know Your Tumor’ (KYT) is a program sponsored by the advocacy organization, Pancreatic Cancer Action Network (PanCAN), that aims to systematize the implementation of precision medicine in PDAC by allowing patients to undergo commercially available multi-omics profiling of their tumor [25]. In an initial subset of 820 patients with PDAC, 25% harbored mutant somatic or germline genes implicated in the HR-DDR pathway, including BRCA1/2, PALB2, ATM, RAD50, and the Fanconi anemia genes [38]. In their multivariable model examining patients with advanced PDAC previously treated with a platinum agent, HR-DDR-deficiency was associated with better outcomes than HR-DDR-proficiency in terms of mOS (2.37 vs 1.45 years, respectively; HR 0.44, 95% CI 0.29–0.66, P=0.000072) and mPFS (13.7 vs 8.1 months; HR 0.47, 95% CI 0.3–0.74, P=0.0011). Similarly, Park et al. from Memorial Sloan Kettering observed germline or somatic mutant HR genes predicted improved mPFS when patients with stage III/IV PDAC were treated with first-line platinum vs non-platinum regimens (12.6 vs 4.4 months, respectively: HR 0.44, 95% CI 0.29–0.67, p<0.01) [39]. Notably, higher genomic instability and further improved response to platinum were observed in patients with biallelic HR genes mutations (mPFS in platinum- vs non-platinum-treated patients: 13.3 [95% CI 9.57–NR] vs 3.8 [95% CI 2.79–NR] months; P<0.0001), and with BRCA1/2 and PALB2 mutations (HR 0.43, 95% CI 0.26–0.70, P<0.05).

In an attempt to deepen tumor responses and delay emergence of resistance, the PARPi veliparib was studied in a phase 2 trial by O’Reilly et al. in untreated locally advanced and mPDAC with germline BRCA1/2 or PALB2 mutations [21]. Patients were randomized to receive cisplatin/gemcitabine with/without veliparib. ORRs in both groups were high albeit similar (74.1% with veliparib vs 65.2% without veliparib, P=0.55). mOS were respectively 15.5 months (95% CI 12.2–24.3) vs 16.4 months (95% CI 11.7–23.4, P=0.6), which were notably longer relative to other PDAC trials. These data underscore that a mutant BRCA/PALB2 is a predictive biomarker for better survival with platinum therapy and establishes cisplatin/gemcitabine as a standard-of-care regimen in this subset of PDAC patients and an alternative to FOLFIRINOX.

3.2. Mismatch Repair-Deficient (dMMR) and Microsatellite Instability-High (MSI-H) PDAC

dMMR/MSI-H occurs rarely in PDAC with one report noting an incidence of 0.8% [40]. dMMR is associated with up to a 100-fold increase in mutations particularly in repetitive DNA sequences termed microsatellite, thus causing MSI [41]. dMMR status is typically confirmed by IHC with absent nuclear staining of mismatch repair enzymes in the presence of positive staining in a normal tissue control [40]. MSI status may be determined with PCR or MSIsensor analysis. MSI-H is confirmatory if PCR detects instability at ≥ 2 microsatellite loci. MSIsensor is a next-generation sequencing (NGS) bioinformatic algorithm that compares length distribution of all genomic microsatellite loci to matched normal tissue. MSI-H is defined if >10% of loci show instability [40].

dMMR/MSI-H tumors harbor extensive mutation-associated neoantigens, which have been correlated with intratumoral immune cell infiltration and response to PD-1 (programmed death-1) inhibitors regardless of tumor type [42, 43]. Le et al. enrolled 86 patients across twelve dMMR tumor types whose disease had progressed on prior therapies. Among eight patients with advanced PDAC, two achieved a CR and three a PR, survival data were not reported [42]. The non-randomized phase 2 KEYNOTE-158 trial evaluated advanced solid tumors with dMMR/MSI-H treated with pembrolizumab [44]. In a preliminary analysis of 22 patients with PDAC, only four (18.2%) experienced an objective response (one CR, three PRs), mPFS and mOS were 2.1 months (95% CI 1.9–3.4) and 4 months (95% CI 2.1–9.8), respectively.

Favorable results from five uncontrolled, open-label trials including KEYNOTE-158 led to the first FDA tissue/site-agnostic accelerated approval for pembrolizumab in May 2017 for unresectable or metastatic dMMR/MSI-H tumors [45, 46]. Its approval was expanded in June 2020 to include mutational burden-high (TMB-H) advanced tumors [47]. This extension was based on another retrospective analysis of KEYNOTE-158. TMB-H, defined as ≥10 mutations/megabase, showed significantly higher ORR (29%, 95%CI 21–39) compared to non-TMB-H patients (6%, 95%CI 5–8) when treated with pembrolizumab [48]. Notably, this dataset did not include any PDAC patients. The 2020 ASCO mPDAC guideline update recommends pembrolizumab as second-line therapy for tumors with dMMR/MSI-H (evidence quality: high; strength of recommendation: strong) [24].

3.2.1. Immunotherapy in non-dMMR/MSI-H PDAC

Beyond dMMR/MSI-H, PDAC has been considered an immunologically “cold” tumor with poor response to immunotherapy. In patients with locally advanced or metastatic PDAC ICI monotherapy has resulted in few to no responses [49, 50]. In settings of dual CTLA-4 and PD-L1 blockade in patients with mPDAC whose disease progressed on first-line fluorouracil-/gemcitabine-based therapy, a phase 2 trial demonstrated an ORR of 3.1% (95%CI 0.08–16.22) with durvalumab plus tremelimumab and 0% (95%CI 0.0–10.6) with durvalumab alone [51]. mOS was 3.1 months (95%CI 2.2–6.1) in the combination arm vs 3.6 months (95%CI 2.7–6.1) in durvalumab alone arm, both notably inferior to historical outcomes with chemotherapy [52, 53].

In patients with mPDAC previously not treated, a phase 1b/2 study with pembrolizumab plus GnP reported encouraging mPFS and mOS of 9.1 months (95% CI 4.9–15.3) and 15 months (95% Cl 6.8–22.6), respectively [54]. A phase 1 trial with nivolumab plus GnP in 50 treatment-naïve advanced PDAC patients reported an overall ORR of 18% (95%CI 8.6–31.4) [55]. Interestingly, patients with baseline tumor PD-L1 expression ≥5% had a nonsignificant yet numerically longer mOS than those with <5% (11.6 vs 9.7 months, respectively: HR 0.9, 95%CI 0.32–2.37) [55]. In a large randomized phase 2 trial with 180 patients with untreated mPDAC, adding durvalumab/tremelimumab to GnP did not improve mOS (9.8 months in quartet regimen vs 8.8 months in GnP alone; HR 0.94, 90%CI 0.71–1.25, P=0.72), or ORR (30.3% vs 23.0% respectively; OR 1.49, 90%CI 0.81–2.72, P=0.28) despite lower CI levels [56].

The phase 2 COMBAT trial evaluated the CXCR4 antagonist motixafortide (BL-8040) and pembrolizumab with/without chemotherapy (liposomal irinotecan/5-fluorouracil/leucovorin) [57]. In their expansion cohort of 22 mPDAC patients, the combined regimen achieved disease control in 17 (77%) cases including seven PRs and ten SD, which were higher than the historically reported outcome in the NAPOLI-1 study with liposomal irinotecan/5-fluorouracil/leucovorin alone (ORR 17%, 95%CI 10–24; DCR 52%, 95%CI 43–61) [58].

Increasing research focus has shifted towards turning tumors from “cold” to “hot”. CD40 is a tumor necrosis factor receptor on the surface of antigen-presenting cells that interacts with the CD40-ligand expressed on activated T cells [59]. The CD40 pathways play a critical regulatory role in T and B cells in the TME [60]. Preclinically, combined CD40 and PD-1/L1 blockade showed synergistic antitumor activity [61]. When administered with GnP, CD40 agonists sensitized tumor to ICIs in murine models [62]. A multi-center phase 1b study observed promising results from the combinations of GnP with the CD40 antibody APX005M and with/without nivolumab. Among 24 patients with mPDAC at a median follow-up of 32.2 weeks, only one patient had disease progression, while 14 (58%) had a PR and 8 (33%) had SD [63]. The phase 2 portion of this trial has completed enrollment and results are expected in 2021 (NCT03214250).

3.3. KRAS Wild-Type PDAC

KRASWT is observed in 6–8% of PDAC and confers better survival outcome [64, 65]. Sequencing of these samples reveals enrichment for dMMR and potentially actionable pathways including mutation of downstream Ras/Raf/MAPK genes and oncogenic fusions including NTRK, NRG1, ROS1 and ALK genes [8].

3.3.1. NTRK Gene Fusions

Oncogenic NTRK fusions occur in approximately 0.34% of PDAC patients and may be detected by IHC using a targeted rabbit monoclonal antibody (mAb) [66]. DNA- and RNA-based sequencing may also be applied with a specificity of 99.9%, although false negatives may occur in fusions involving breakpoints not covered by the assay [66].

Larotrectinib and entrectinib are multitargeted TRK inhibitors, and their efficacy were tested in six trials that enrolled patients with various locally advanced and metastatic solid tumors with NTRK fusions [67, 68]. Only four PDAC cases were included. A PR was achieved in two out of three PDAC patients in the entrectinib studies, and in the one patient treated with larotrectinib. PDAC-specific survival data were not reported. Larotrectinib and entrectinib are FDA-approved for adult and pediatric patients with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors that harbor NTRK fusions [69, 70]. The 2020 ASCO mPDAC guideline update recommends larotrectinib or entrectinib in patients with NTRK fusion-positive PDAC whose disease progressed on first-line therapy (evidence quality: low; strength of recommendation: moderate) [24]. Given the potential for acquired resistance, second-generation NTRK inhibitors are being explored including selitrectinib (LOXO-195) (NCT03206931), and repotrectinib (TPX-0005) (NCT03093116, NCT04094610).

3.3.2. Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor

EGFR overexpression is associated with tumor metastasis and poor outcome in PDAC [71]. EGFR inhibition may confer improved benefit in KRASWT tumors [72, 73]. The EGFR inhibitor erlotinib combined with gemcitabine achieved statistically significant yet clinically modest results in a phase 3 trial in advanced PDAC: one-year OS was 23% (95%CI 18–28) with erlotinib/gemcitabine vs 17% (95%CI 12–21) with placebo/gemcitabine (P=0.023) [74]. Subsequent molecular analysis from the same cohort did not identify EGFR copy number variation (HR 0.90, 95%CI 0.49–1.65, P=0.73) or KRASWT (HR 0.66, 95%CI 0.28–1.57, P=0.34) as predictor of erlotinib response [75]. Another randomized trial observed that in patients with untreated mPDAC, EGFR mutations caused by amino acid substitutions was associated with improved survival with erlotinib/gemcitabine vs with gemcitabine/placebo, with mOS respectively 8.7 months (95%CI 6.2–11.1) vs. 6.0 months (95%CI 3.0–8.9; P=0.044) [76]. Nimotuzumab is a highly selective anti-EGFR mAb. Compared to gemcitabine alone, nimotuzumab/gemcitabine improved mOS (8.6 vs 5.1 months: HR 0.69, 95%CI 0.49–0.98, P=0.034) in a phase 2b trial in patient with untreated locally advanced or metastatic PDAC [77]. The prevalence of KRASWT in 33 out of 97 patients in this cohort was remarkably high, and correlated with a significantly higher one-year survival rate with the doublet regimen vs with gemcitabine monotherapy (53.8% vs 15.8%, respectively; HR 0.32, 95%CI 0.13–0.84, P=0.026). However, EGFR overexpression did not impact the one-year survival rate (HR 0.75, 95%CI 0.35–1.56, P=0.045). A larger phase 3 study of nimotuzumab plus gemcitabine in patients with KRASWT PDAC registered since March 2015 albeit the current status is marked as unknown (NCT02395016), suggesting recruitment challenges related to the relative infrequency of KRASWT PDAC.

3.3.3. Neuregulin 1 (NRG1)

Oncogenic NRG1 fusions occur in 0.5% of PDAC tumors and may be detected with anchored multiplex PCR targeted RNA sequencing [78]. A small case series included two mPDAC patients with KRASWT and NRG1 fusions treated with the HER-family kinase inhibitor, afatinib, as monotherapy, Both experienced a PR with duration of best response of 5.5 and 8 months [79]. In another series, two patients with NRG1-rearranged mPDAC both received afatinib and experienced a PR. At study cutoff, one had disease progression at 5.5 months, the other patient had ongoing response at 5 months [80]. The bispecific HER-2/HER-3 antibody, zenocutuzumab (MCLA-128), showed favorable preliminary results in two patients with mPDAC. The first patient experienced a PR with 54% tumor reduction, while a second patient achieved SD. Both had durable responses and at data cutoff had remained on therapy over 28 weeks [81]. A single-arm phase 2 trial of zenocutuzumab in NRG1-positive advanced solid tumors including PDAC is underway (NCT02912949).

3.3.4. Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK)

Translocations of ALK with different partner genes lead to activating fusions in 0.16% of PDAC patients [82, 83]. ALK rearrangements are confirmed by fluorescence in situ hybridization if >15% of tumor cells demonstrate split signals. In a cohort with five ALK-fusion positive patients with locally advanced or mPDAC, four received ALK inhibitors including crizotinib, alectinib, and ceritinib. All four patients achieved SD with variable response duration from two to fifteen months [82]. In a non-randomized phase 1 trial (NCT02227940), patients with locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors including PDAC were enrolled to receive ceritinib/gemcitabine (arm 1), or with additional nab-paclitaxel (arm 2) or cisplatin (arm 3). Each arm included an expansion cohort with ALK-rearranged tumors. The study appears completed although pending presentation of data. Another trial of ceritinib in patients with ALK- and ROS1-activated gastrointestinal malignancies was terminated due to lack of enrollment (NCT02638909), speaking to the rarity of these mutations.

3.4. Targeting KRAS

The frequency of specific oncogenic substitution in KRAS varies by cancer type. In PDAC, mutational activation of KRAS occurs in codon G12 in up to 93% of cases, and at lower prevalence in hotspots G13 and Q61 [8, 84]. At position G12, G12D remains the most common mutational substitution (41–44%), followed by G12V (29–34%), G12R (16–20%), and G12C (1–3%) [8, 84]. The “undruggability” of KRAS is due in part to its smooth molecular surface without a clear binding pocket and its high affinity for GTP while in active state [85]. Nevertheless, discovery of allele-specific inhibitors and small interference RNA (siRNA)-based therapies has provided a renewed focus on KRAS inhibition. LODER™ (Local Drug EluteR) (Silenseed Ltd., Jerusalem, Israel) is a biodegradable polymeric matrix that provides consistent release of anti-KRASG12D siRNA over months. In an open-label phase 1/2a study with locally advanced PDAC, single dose of LODER™ was delivered intratumorally via standard biopsy procedure to 15 patients in addition to gemcitabine, FOLRIFINOX, or gemcitabine/oxaliplatin/erlotinib [86]. The LODER™ administration had a favorable safety profile without dose-limiting toxicity. mOS was 15.1 months (95% CI 10.2–18.4) in all patients and was 27 months (range not reported) in the small FOLFIRINOX-treated group (n=3). A single-arm, open-label phase 2 PROTACT trial with LODER™ is currently ongoing. Patients with locally advanced PDAC will receive up to three doses of the experimental agent plus investigator’s choice of chemotherapy (GnP or mFOLFIRINOX). The primary endpoint is ORR [87].

Oral allele-specific inhibitors have been developed to target KRASG12C, which occurs in 1% to 3% of PDAC [88]. Sotorasib (AMG510) is a first-in-class small molecule that irreversibly inhibits KRASG12C, and its safety and efficacy were evaluated in the phase 1/2 dose-escalation CodeBreak 100 trial. Patients with KRASG12C-mutant locally advanced or metastatic solid tumors including twelve PDAC cases were assessed. Responses were evaluable in eleven and included eight cases with SD and one PR [89]. The safety and efficacy of MRTX849, another orally available small molecule KRASG12C inhibitor, are being assessed in advanced or metastatic tumors including PDAC with mutant KRASG12C (NCT03785249, NCT04330664). Lastly, a phase 1 trial with a selective oral KRASG12C inhibitor, JNJ-74699157, was recently completed in September 2020, with results still pending (NCT04006301).

Antitumoral peripheral blood lymphocytes (PBLs) were designed to recognize and target specific KRAS mutations. This cell therapy requires harvesting of HLA-A1101-positive PBLs from patients with, for instance, KRASG12D, which are then transfected by a retroviral vector encoding anti-KRASG12D murine T-cell receptor (mTCR), followed by in vitro expansion of transduced PBLs. Anti-KRASG12D mTCR PBLs are then administered back to patient via autologous leukapheresis [90]. The safety and antitumor activity are being evaluated in patients with unresectable or metastatic solid tumors including PDAC that harbor KRASG12D (NCT03745326) and KRASG12V mutations (NCT03190941).

V941 is an mRNA-derived cancer vaccine that harbors immunostimulatory and antineoplastic activity against four of the most frequent KRAS mutations (G12D, G12V, G13D, and G12C). An ongoing dose-finding phase 1 trial is evaluating safety and tolerability of V941 with/without pembrolizumab in advanced or metastatic tumors including PDAC with mutant KRAS (NCT03948763).

Mutation of downstream effector pathways (e.g. RAF/MEK/ERK cascade) may cause resistance to anti-KRAS strategies. In PDAC models with mutant KRASG12C, KRASG12V or KRASQ61K, trametinib with BI-3406, an orally bioavailable inhibitor of the KRAS activator, SOS1, displayed promising synergistic antitumor activity although its efficacy and safety are yet to be tested in patients with KRAS-driven PDAC [91].

3.5. Autophagy Inhibition

Autophagy (“self-devouring”) is an adaptive metabolic process upregulated in PDAC with KRAS mutations whereby cells degrade their own organelles to support increased energy needs and ensure cell survival [92]. Hydroxychloroquine (HCQ) inhibits autophagy by preventing fusion between the autophagosome and lysosome. In a phase 2 randomized trial of 112 patients with untreated locally advanced or metastatic PDAC, HCQ plus GnP demonstrated a higher ORR compared to GnP alone (38% vs 21% respectively, range not reported, P=0.047) [93]. However, adding HCQ did not improve the primary endpoint of 12-month survival rate which were 41% (95% CI 27–53) in HCQ group vs 49% (95% CI 35–61) in non-HCQ group (P =0.44). Preclinical models suggest that KRAS and ERK suppression upregulates autophagic flux, and that chloroquine combined with ERK inhibitors may enhance synergistic antitumor effect in PDAC with KRAS mutations [94]. The THREAD trial is an ongoing phase 1 dose-finding trial assessing trametinib plus HCQ in locally advanced or metastatic PDAC (NCT03825289). Binimetinib plus HCQ will be studied in phase 1 study enrolling only patients with mPDAC (NCT04132505). Additionally, a triplet regimen of HCQ plus MEK inhibitor (cobimetinib) plus immunotherapy (atezolizumab) is underway in a phase 1/2 study with subjects with advanced solid tumors including PDAC (NCT04214418).

3.6. BRAF

Alterations in BRAF including single amino acid substitutions, amplification, deletion or oncogenic fusions occurs in approximately 3% of PDAC and leads to activation of the downstream MAPK pathway [8, 95]. Vemurafenib is a BRAF inhibitor approved for melanoma with specific anti-BRAFV600E activity [96]. Evidence for BRAF-targeting in PDAC remains scarce. MyPathway, an open-label phase 2a multiple basket study included 251 patients across 35 tumor types who received targeted therapy [97]. Only one patient with a diagnosis of PDAC and a CUX1-BRAF fusion was identified who achieved a PR with vemurafenib (response duration not reported). The KYT registry trial included two patients who received BRAF inhibitors: one patient with a BRAFV600E mutation had a sustained response for eleven months (type of response unspecified) with dabrafenib plus trametinib, the other patient whose tumor had concurrent KRASG12A and BRAFK601N mutations had disease progression on trametinib monotherapy [95, 98]. The combination of binimetinib and encorafenib in stage III/IV PDAC with BRAFV600E mutations is being examined in a single-arm, non-randomized phase 2 trial (NCT04390243).

3.7. Stromal Modulation

Tumor-adjacent pancreatic stellate cells produce a dense, collagen-rich extracellular stroma. This desmoplastic reaction creates a hypovascular TME that putatively impairs effective chemotherapy delivery [99]. Connective tissue growth factor (CTGF) affects tumor cell biology and is associated with PDAC with high degrees of desmoplasia [100]. In a phase 1/2 trial of 37 patients with locally advanced PDAC, neoadjuvant GnP was administered with (arm A) and without (arm B) pamrevlumab, a humanized anti-CTGF mAb [101]. A PR was observed in five (21%) and three (23%) patients in arms A and B, respectively (P value not reported). Pamrevlumab was associated with improved eligibility for surgical exploration (17 patients in arm A vs two in arm B, P=0.0019), although resection rates were not significantly different in both arms (eight in arm A vs one in arm B, P=0.119). The mOS were overlapping at 19.3 months (95% CI 13.3–27.7) in arm A and 19.0 months (95% CI 13.2–not reached [NR]) in arm B, respectively. The safety and efficacy of neoadjuvant pamrevlumab plus GnP is being explored in a phase 3 trial with enrolling patients with locally advanced PDAC (NCT03941093).

The vitamin D receptor is upregulated in PDAC stroma and its blockade results in stromal remodeling, tumor shrinkage, and increased survival in murine models [102]. The vitamin D analog paricalcitol is being investigated in trials enrolling patients with mPDAC including one in combination with chemotherapy (with GnP in NCT03520790; gemcitabine/nab-paclitaxel/cisplatin in NCT03415854). A maintenance strategy comparing pembrolizumab/paricalcitol vs pembrolizumab/placebo was evaluated in advanced patients with PDAC who achieved at least SD after conventional chemotherapy (NCT03331562). This phase 2 trial is currently completed and pending results.

3.8. Targeting PDAC Metabolism

KRAS signaling is linked to metabolic dysregulation and tumor dependence on glutamine and asparagine [103]. Argininosuccinate synthetase (ASS1), a rate-limiting enzyme involved in arginine synthesis, is often deficient in PDAC [104]. ADI-PEG 20 is a Mycoplasma-derived pegylated arginine deiminase that was shown to have arginine-depleting activity and synthetic lethality in preclinical ASS1-deficient PDAC models [105]. A single-arm phase 1/1b study examined intramuscular ADI-PEG 20 plus GnP in 18 patients with mPDAC. Disease control was achieved in 17 (94%) patients including seven cases with PR and 10 with SD. In patients who received the treatment as first-line therapy at maximum tolerated doses, mPFS and mOS were 6.1 months (95% CI 5.3–11.2) and 11.3 months (95% CI 6.7–NR), respectively [106].

Asparagine synthetase (ASNS) is associated with tumor resistance to apoptosis and its expression may be enhanced in PDAC [103]. Eryaspase is an agent with a novel asparaginase delivery approach: asparaginase is encapsulated within erythrocytes, which limits toxicity and prevents premature enzymatic degradation [107]. Eryaspase plus modified FOLFOX6 (oxaliplatin, leucovorin, fluorouracil), or gemcitabine were evaluated in a randomized phase 2b trial that enrolled patients with advanced PDAC whose disease progressed after first-line treatment [108]. Eryaspase plus chemotherapy were well-tolerated and resulted in a prolongation of mOS compared to chemotherapy alone (6.0 vs 4.4 months respectively: HR 0.60, 95% CI 0.41–0.87, P=0.008). Baseline ASNS expression determined by IHC did not significantly predict overall survival (low ASNS expression: HR 0.63, 95% CI 0.39–1.01, P=0.056; high ASNS expression: HR 0.52, 95% CI 0.26–1.04, P=0.063). The TRYbeCA-1 trial is an ongoing randomized phase 3 trial which will further explore the efficacy of eryaspase in advanced PDAC (NCT03665441) [109].

Devimistat (CPI-613), a novel mitochondrial inhibitor combined with mFOLFIRINOX showed encouraging results in a phase 1 study with newly diagnosed mPDAC. Responses were observed in 11 (61%) out of 18 patients, and included three cases with CR and eight with PR [110]. The AVENGER 500 trial is an ongoing phase 3 study that will compare efficacy and safety of devimistat plus mFOLFIRINOX vs FOLFIRINOX alone in treatment-naïve mPDAC patients (NCT03504423) [111].

4. Current Challenges and Future Perspectives

Several large, randomized trials have recently reported disappointingly negative. The Bruton’s tyrosine kinase inhibitor, ibrutinib, was hypothesized to add antitumoral activity via TME modulation. However, in the phase 3 RESOLVE study ibrutinib plus GnP had a shorter mPFS compared to GnP alone (5.3 vs 6.0 months, respectively; HR 1.525, CI not reported, P<0.0001) [112]. Development of napabucasin, a first-in-class cancer stemness inhibitor, was halted after interim analysis showed futility in the CanStem111P phase 3 trial although specific details are awaited [113]. Despite encouraging early data with the hyaluronic acid (HA) degrading enzyme, pegvorhyaluronidase alfa (PEGPH20) [114, 115], in the subsequent phase 3 HALO-109–301 trial in patients with untreated mPDAC with high HA expression, PEGPH20 plus GnP compared to GnP alone did not improve in mOS (11.2 vs 11.5 months respectively; HR 1.00, CI not reported, P=0.9692) [116]. The PDAC TME is a highly complex and dynamic structure that directly influences behavior both at molecular and clinical levels. The stroma holds abundant immunosuppressive cells (e.g. myeloid-derived suppressor cells) which hinder antitumoral function of cytotoxic T cells, leading to immune evasion [117]; these cells also release proinflammatory cytokines which activate stellate cells further exacerbating desmoplasia [118]. Perennial hypoxic conditions in the TME upregulate pathways involved in cell survival and multidrug resistance, including MDR1, hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, BRCA2 and Rad51 [119–121]. Further investigation is warranted on the crosstalk between tumor, stroma and immune cells, with a focus on exosome-mediated intercellular signaling between PDAC cells and adjacent organs. Exosomal RNA and protein have been implicated in PDAC metastasis and chemoresistance, and their detection may serve as a biomarker for early diagnosis and prognostication [122]. Inhibition of exosome release or uptake may provide an additional valuable therapeutic target.

Aside from genomics and transcriptomics, epigenomic alterations add an additional layer of complexity to pancreatic carcinogenesis. Many mutated oncogenes, including KRAS, promote cell survival in part by dysregulating histone and DNA modifying enzymes [123]. While oncogenic driver mutations initiate PDAC development, mounting evidence suggests epigenomic super-enhancers directly influence the transcriptional phenotypes [124]. In preclinical models, inactivation of MET resulted in increased GATA6 transcription and led to conversion from the more aggressive basal to classical subtype, suggesting the existence of phenotypic plasticity [123]. Further therapeutic exploration for PDAC will require epigenomic-specific approaches.

In addition to new drug and target discovery, logistic barriers hinder application of precision medicine. While data have suggested a real-time genomic characterization of PDAC is feasible within a reasonable timeframe (median biopsy-to-result time 20–35 days) [12, 125], implementing an efficient testing protocol remains a challenging task requiring a significant multidisciplinary effort which is mostly not feasible for frontline treatment decision making. Circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) analysis provides an easily accessible methods for noninvasive tumor molecular profiling which has showed promising value in PDAC prognostication [126, 127], albeit its role in biomarker identification remains to be tested. Noteworthy, novel clinical trials designs have been constructed to facilitate targeted therapy development. PanCAN launched Precision Promise, an adaptive clinical trial at 14 consortium sites across the United States [128]. This is a multi-center, phase 2/3 platform trial that aims to offer investigational therapies based on molecular profiling hence allowing simultaneous evaluation of targeted agents (NCT04229004). Similarly, the Precision-Panc initiative will deliver tailored treatment to PDAC through the United Kingdom National Health Service across over 20 sites (NCT04161417) [129]. The current ASCO and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines for patients with locally advanced and metastatic PDAC recommend early testing for somatic and germline genomic alteration in patients who may be candidates for targeted therapy [24, 130]. Table 3 summarizes the minimum recommended testing panel for somatic and germline alterations in PDAC.

In conclusion, the paradigm in the treatment of PDAC is evolving for subsets of patients towards targeted therapy based on established specific tumor biomarkers such as germline BRCA1/2, dMMR/MSI-H status, and KRASWT with actionable fusions. Emerging predictors such as specific gene alterations and transcriptomic subtypes will open additional therapeutic refinements to include a broader PDAC population. Despite encouraging results in some settings, past trial failures indicate the necessity of a deeper understanding and ability to surmount the crosstalk between the tumor, the stroma and the immune cells. Moreover, streamlining of individual tumor profile testing is warranted for timely implementation of a precision medicine strategy.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Selective Pancreas Cancer Germline Sequencing Cohorts

| Reference | Patient population | Sample source | Scope of germline sequencing | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network [8] | 150 with PDAC | Peripheral blood | – Exome sequencing of 13 known germline predisposition genes | – GPV present in 11 patients (8%) – BRCA2 was the most frequent (6/11) – Enrichment for germline mutations in KRAS wild-type samples (P=0.027) |

|

| ||||

| Lowery et al. [131] | 615 with exocrine pancreatic cancer, 554 were PDAC | Peripheral blood | – 76 genes associated with cancer susceptibility | – GPV involving 24 different genes found in 122 (19.8%) – 20 (18%) of 111 Ashkenazi Jewish patients harbored common BRCA Ashkenazi Jewish founder’s mutations – 41.8% did not meet guideline criteria for germline testing – Presence of germline alteration did not affect mOS (two-sided P=0.94) |

|

| ||||

| Skaro et al. [16] | 315 with resected IPMNs | Non-tumor tissue from duodenum, gallbladder, liver, or spleen | – 94 genes with variants associated with cancer risk | – 23 (7.3%) with germline mutation – IPMNs with germline mutations associated with higher rate of concurrent invasive pancreatic carcinoma (P=0.032) |

|

| ||||

| Roberts et al. [132] | 638 with FPC*^ | Blood (n=454), lymphoblastoid cell line (n=158), nontumoral tissue (n=26) | – WGS – In-depth analysis of all variants of 87 selected germline genes – Matched with tumor exomes in 39 patients |

– 214 deleterious variants of the 87 selected genes found – 32 patients had two or more deleterious events – Proposed new candidate genes (BUB1B, CPA1, FANCC, and FANCG) – Results validated in an independent WES cohort |

|

| ||||

| Earl et al. [133] | 43 PDAC from families with an apparent hereditary pancreatic cancer syndrome | Peripheral blood | – 35-genes panel sequencing | – GPVs in 19% (5/26) – Low frequency variants in other DNA repair genes found in 35% – Concluded that genetic basis of familial or hereditary pancreatic cancer may be explained in 21% of families |

|

| ||||

| Cremin et al. [134] | 177 PDAC, irrespective of family history | Saliva | – 30-gene NGS panel test – A subset received 17 gene panel including BRCA1/BRCA2 – if history suggestive for other genetic syndromes: larger panel with 42–83 genes |

– GPV found in 25/177 (14.1%) – 19 out of 25 had known PDAC susceptibility larger panel with 42-83 genes |

|

| ||||

| Shindo et al. [23] | 854 with PDAC 288 with other pancreatic and periampullary neoplasms 51 with non-neoplastic diseases who underwent pancreatic resection | Normal nontumoral tissue | – 32 genes, including known pancreatic cancer susceptibility genes | – 33 (3.9%) patients with PDAC had GPVs – Patients with GPVs were younger (mean age 60.8 years v 65.1 years, P=0.03) – Only 3 of 33 patients had family history of pancreatic cancer |

|

| ||||

| Takai et al. [135] | Japan-based study with 1197 with pancreatic cancer including variants Of which, 88 with PDAC and at least one first-degree relative with PDAC Only 54 out of these 88 underwent sequencing | Peripheral blood | – 21-genes NGS panel | – No significant differences between individuals with family history vs sporadic cases in terms of gender, age, tumor location, stage, family history of nonpancreatic cancer – Eight patients with available germline DNA carried deleterious mutations in BRCA2, PALB2, ATM, or MLH1 |

|

| ||||

| Chaffee et al. [17] | 302 with PDAC: 185 were FPC*; 117 had positive family history without meeting FPC criteria. | Lymphocyte DNA | – 5 cancer susceptibility genes | – Of FPC patients, 25/185 (14%) were carriers – Of non-FPC cases with family history, 11/117 (9%) were carriers |

|

| ||||

Defined as PDAC patients with at least two affected first-degree relatives

Patients with previously reported FPC susceptibility gene were excluded

High-risk families identified with the following criteria: familial pancreatic cancer families with ≥2 affected first degree relatives; Hereditary Breast and Ovarian Cancer families with at least one case of pancreatic cancer; Familial Atypical Multiple Mole Melanoma families; Hereditary Non-Polyposis Colorectal Cancer (HNPCC) families with at least one case of pancreatic cancer and PDAC cases diagnosed at ≤50 years of age

Abbrev. FPC, familial pancreatic cancer; GPV, Germline pathogenic variant; IPMN, intraductal papillary mucinous neoplasms; NGS, next generation sequencing; PDAC, pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma; WES, whole exome sequencing; WGS, whole genome sequencing.

Acknowledgments

Funding

NCI Cancer Center Support Grant: P30 CA008478

David M. Rubenstein Center for Pancreas Cancer Research

Conflict of Interest/Disclosure Statement

EOR: Research funding to MSK: Genentech-Roche, Celgene-BMS, BioNTech, BioAtla, AstraZeneca, Arcus Consulting/Advisory/DSMB: Cytomx Therapeutics, Rafael Therapeutics, Sobi, Silenseed, Molecular Templates, Boehringer Ingelheim, BioNTech, Ipsen, Polaris, Merck, AstraZeneca, Bayer, Genentech-Roche, Celgene-BMS, Eisai. MSK Institutional COI: BioNTech

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rahib L, Smith BD, Aizenberg R, Rosenzweig AB, Fleshman JM, Matrisian LM. Projecting cancer incidence and deaths to 2030: the unexpected burden of thyroid, liver, and pancreas cancers in the United States. Cancer Res. 2014;74(11):2913–21. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-0155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jones S, Zhang X, Parsons DW, Lin JC, Leary RJ, Angenendt P, et al. Core signaling pathways in human pancreatic cancers revealed by global genomic analyses. Science. 2008;321(5897):1801–6. doi: 10.1126/science.1164368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torres C, Grippo PJ. Pancreatic cancer subtypes: a roadmap for precision medicine. Ann Med. 2018;50(4):277–87. doi: 10.1080/07853890.2018.1453168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Biankin AV, Waddell N, Kassahn KS, Gingras MC, Muthuswamy LB, Johns AL, et al. Pancreatic cancer genomes reveal aberrations in axon guidance pathway genes. Nature. 2012;491(7424):399–405. doi: 10.1038/nature11547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Harada T, Chelala C, Bhakta V, Chaplin T, Caulee K, Baril P, et al. Genome-wide DNA copy number analysis in pancreatic cancer using high-density single nucleotide polymorphism arrays. Oncogene. 2008;27(13):1951–60. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Collisson EA, Sadanandam A, Olson P, Gibb WJ, Truitt M, Gu S, et al. Subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma and their differing responses to therapy. Nat Med. 2011;17(4):500–3. doi: 10.1038/nm.2344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cancer Genome Atlas Research Network. Electronic address aadhe, Cancer Genome Atlas Research N. Integrated Genomic Characterization of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma. Cancer Cell. 2017;32(2):185–203 e13. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.07.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Waddell N, Pajic M, Patch AM, Chang DK, Kassahn KS, Bailey P, et al. Whole genomes redefine the mutational landscape of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2015;518(7540):495–501. doi: 10.1038/nature14169. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moffitt RA, Marayati R, Flate EL, Volmar KE, Loeza SG, Hoadley KA, et al. Virtual microdissection identifies distinct tumor- and stroma-specific subtypes of pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Nat Genet. 2015;47(10):1168–78. doi: 10.1038/ng.3398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bailey P, Chang DK, Nones K, Johns AL, Patch AM, Gingras MC, et al. Genomic analyses identify molecular subtypes of pancreatic cancer. Nature. 2016;531(7592):47–52. doi: 10.1038/nature16965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aung KL, Fischer SE, Denroche RE, Jang GH, Dodd A, Creighton S, et al. Genomics-Driven Precision Medicine for Advanced Pancreatic Cancer: Early Results from the COMPASS Trial. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(6):1344–54. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-2994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.O’Kane GM, Grunwald BT, Jang GH, Masoomian M, Picardo S, Grant RC, et al. GATA6 Expression Distinguishes Classical and Basal-like Subtypes in Advanced Pancreatic Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(18):4901–10. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hruban RH, Zamboni G. Pancreatic cancer. Special issue--insights and controversies in pancreatic pathology. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(3):347–9. doi: 10.1043/1543-2165-133.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rainone M, Singh I, Salo-Mullen EE, Stadler ZK, O’Reilly EM. An Emerging Paradigm for Germline Testing in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma and Immediate Implications for Clinical Practice: A Review. JAMA Oncol. 2020;6(5):764–71. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2019.5963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skaro M, Nanda N, Gauthier C, Felsenstein M, Jiang Z, Qiu M, et al. Prevalence of Germline Mutations Associated With Cancer Risk in Patients With Intraductal Papillary Mucinous Neoplasms. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(6):1905–13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chaffee KG, Oberg AL, McWilliams RR, Majithia N, Allen BA, Kidd J, et al. Prevalence of germ-line mutations in cancer genes among pancreatic cancer patients with a positive family history. Genet Med. 2018;20(1):119–27. doi: 10.1038/gim.2017.85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Friedenson B BRCA1 and BRCA2 pathways and the risk of cancers other than breast or ovarian. MedGenMed. 2005;7(2):60. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lynch HT, Deters CA, Snyder CL, Lynch JF, Villeneuve P, Silberstein J, et al. BRCA1 and pancreatic cancer: pedigree findings and their causal relationships. Cancer Genet Cytogenet. 2005;158(2):119–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cancergencyto.2004.01.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Golan T, Hammel P, Reni M, Van Cutsem E, Macarulla T, Hall MJ, et al. Maintenance Olaparib for Germline BRCA-Mutated Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(4):317–27. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1903387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O’Reilly EM, Lee JW, Zalupski M, Capanu M, Park J, Golan T, et al. Randomized, Multicenter, Phase II Trial of Gemcitabine and Cisplatin With or Without Veliparib in Patients With Pancreas Adenocarcinoma and a Germline BRCA/PALB2 Mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(13):1378–88. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02931. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hruban RH, Canto MI, Goggins M, Schulick R, Klein AP. Update on familial pancreatic cancer. Adv Surg. 2010;44:293–311. doi: 10.1016/j.yasu.2010.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Shindo K, Yu J, Suenaga M, Fesharakizadeh S, Cho C, Macgregor-Das A, et al. Deleterious Germline Mutations in Patients With Apparently Sporadic Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2017;35(30):3382–90. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.72.3502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sohal DPS, Kennedy EB, Cinar P, Conroy T, Copur MS, Crane CH, et al. Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol. 2020:JCO2001364. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.01364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pishvaian MJ, Bender RJ, Halverson D, Rahib L, Hendifar AE, Mikhail S, et al. Molecular Profiling of Patients with Pancreatic Cancer: Initial Results from the Know Your Tumor Initiative. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(20):5018–27. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-18-0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holter S, Borgida A, Dodd A, Grant R, Semotiuk K, Hedley D, et al. Germline BRCA Mutations in a Large Clinic-Based Cohort of Patients With Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(28):3124–9. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.59.7401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xia B, Sheng Q, Nakanishi K, Ohashi A, Wu J, Christ N, et al. Control of BRCA2 cellular and clinical functions by a nuclear partner, PALB2. Mol Cell. 2006;22(6):719–29. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Francica P, Rottenberg S. Mechanisms of PARP inhibitor resistance in cancer and insights into the DNA damage response. Genome Med. 2018;10(1):101. doi: 10.1186/s13073-018-0612-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kaufman B, Shapira-Frommer R, Schmutzler RK, Audeh MW, Friedlander M, Balmana J, et al. Olaparib monotherapy in patients with advanced cancer and a germline BRCA1/2 mutation. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(3):244–50. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2014.56.2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.FDA approves olaparib for gBRCAm metastatic pancreatic adenocarcinoma. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-approves-olaparib-gbrcam-metastatic-pancreatic-adenocarcinoma (2019). Accessed Oct 6 2020.

- 31.Shroff RT, Hendifar A, McWilliams RR, Geva R, Epelbaum R, Rolfe L, et al. Rucaparib Monotherapy in Patients With Pancreatic Cancer and a Known Deleterious BRCA Mutation. JCO Precis Oncol. 2018;2018. doi: 10.1200/PO.17.00316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lowery MA, Kelsen DP, Capanu M, Smith SC, Lee JW, Stadler ZK, et al. Phase II trial of veliparib in patients with previously treated BRCA-mutated pancreas ductal adenocarcinoma. Eur J Cancer. 2018;89:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nesic K, Wakefield M, Kondrashova O, Scott CL, McNeish IA. Targeting DNA repair: the genome as a potential biomarker. J Pathol. 2018;244(5):586–97. doi: 10.1002/path.5025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mouw KW, Goldberg MS, Konstantinopoulos PA, D’Andrea AD. DNA Damage and Repair Biomarkers of Immunotherapy Response. Cancer Discov. 2017;7(7):675–93. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-17-0226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lloyd RL, Wijnhoven PWG, Ramos-Montoya A, Wilson Z, Illuzzi G, Falenta K, et al. Combined PARP and ATR inhibition potentiates genome instability and cell death in ATM-deficient cancer cells. Oncogene. 2020;39(25):4869–83. doi: 10.1038/s41388-020-1328-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tentori L, Lacal PM, Muzi A, Dorio AS, Leonetti C, Scarsella M, et al. Poly(ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibition or PARP-1 gene deletion reduces angiogenesis. Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(14):2124–33. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2007.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gunderson CC, Moore KN. BRACAnalysis CDx as a companion diagnostic tool for Lynparza. Expert Rev Mol Diagn. 2015;15(9):1111–6. doi: 10.1586/14737159.2015.1078238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pishvaian MJ, Blais EM, Brody JR, Rahib L, Lyons E, Arbeloa PD, et al. Outcomes in Patients With Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma With Genetic Mutations in DNA Damage Response Pathways: Results From the Know Your Tumor Program. JCO Precision Oncology. 2019(3):1–10. doi: 10.1200/po.19.00115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Park W, Chen J, Chou JF, Varghese AM, Yu KH, Wong W, et al. Genomic Methods Identify Homologous Recombination Deficiency in Pancreas Adenocarcinoma and Optimize Treatment Selection. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26(13):3239–47. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-20-0418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hu ZI, Shia J, Stadler ZK, Varghese AM, Capanu M, Salo-Mullen E, et al. Evaluating Mismatch Repair Deficiency in Pancreatic Adenocarcinoma: Challenges and Recommendations. Clin Cancer Res. 2018;24(6):1326–36. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cancer Genome Atlas N. Comprehensive molecular characterization of human colon and rectal cancer. Nature. 2012;487(7407):330–7. doi: 10.1038/nature11252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Le DT, Durham JN, Smith KN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Aulakh LK, et al. Mismatch repair deficiency predicts response of solid tumors to PD-1 blockade. Science. 2017;357(6349):409–13. doi: 10.1126/science.aan6733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Le DT, Uram JN, Wang H, Bartlett BR, Kemberling H, Eyring AD, et al. PD-1 Blockade in Tumors with Mismatch-Repair Deficiency. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(26):2509–20. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1500596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marabelle A, Le DT, Ascierto PA, Di Giacomo AM, De Jesus-Acosta A, Delord JP, et al. Efficacy of Pembrolizumab in Patients With Noncolorectal High Microsatellite Instability/Mismatch Repair-Deficient Cancer: Results From the Phase II KEYNOTE-158 Study. J Clin Oncol. 2020;38(1):1–10. doi: 10.1200/JCO.19.02105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.FDA grants accelerated approval to pembrolizumab for first tissue/site agnostic indication. https://www.fda.gov/drugs/resources-information-approved-drugs/fda-grants-accelerated-approval-pembrolizumab-first-tissuesite-agnostic-indication (2017). Accessed Sep 5 2020.

- 46.Keytruda (pembrolizumab) injection for intravenous use prescribing information, Merck and Co, Inc. www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/125514s014lbl.pdf (2017). Accessed Sep 5 2020.