Abstract

Microrchidia 2 (MORC2) is an emerging chromatin modifier with a role in chromatin remodeling and epigenetic regulation. MORC2 is found to be upregulated in most cancers, playing a significant role in tumorigenesis and tumor metastasis. Recent studies have demonstrated that MORC2 is a scaffolding protein, which interacts with the proteins involved in DNA repair, chromatin remodeling, lipogenesis, and glucose metabolism. In this review, we discuss the domain architecture and cellular and subcellular localization of MORC2. Further, we highlight MORC2-specific interacting partners involved in metabolic reprogramming and other pathological functions such as cancer progression and metastasis.

Keywords: MORC2, Chromatin modifiers, Interacting partners, Metabolism, Cancer

Introduction

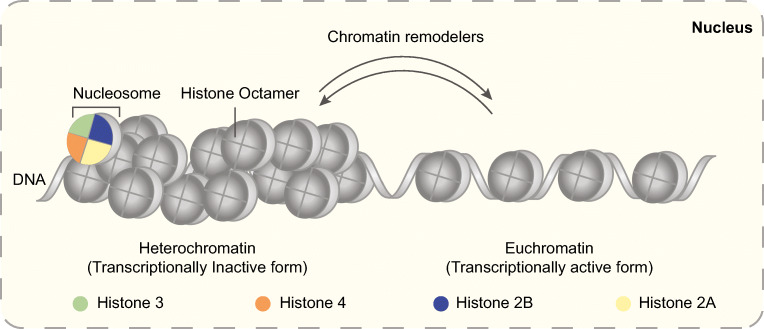

Cancer is the leading cause of mortality worldwide (Ferlay et al. 2020). Genome instability is one of the hallmarks of cancer development (Hanahan and Weinberg 2011). Genome regulation and surveillance are monitored by a set of proteins known as chromatin regulators (Swygert and Peterson 2014). In distinct cancer types, deregulated expression or altered function of these genome regulators is associated with tumorigenesis (Morgan and Shilatifard 2015; Farooqi et al. 2020; Ghasemi 2020). And also, the epigenetic mechanisms like DNA methylation, histone modifications, and noncoding RNAs are playing a pivotal role in tumorigenesis (Dawson and Kouzarides 2012; Sharma et al. 2010). Epigenetic drugs against protein domains involved in chromatin regulation have shown promising results as cancer therapeutics (Dawson and Kouzarides 2012; Yao et al. 2020). Chromatin regulators can be broadly classified as enzymes catalyzing chromatin modification (Kouzarides 2007) and for chromatin remodeling (Sahu et al. 2020). The chromatin remodelers help to open the chromatin in order to drive the process of gene expression (Fig. 1) (Nair and Kumar 2012). One group of ubiquitously expressed chromatin regulators is the Microrchidia (MORC) protein family, which belongs to an evolutionarily conserved CW-type zinc finger (ZF-CW) nuclear protein superfamily. MORC family proteins are strongly involved in chromatin remodeling and epigenetic regulation (Perry and Zhao 2003; Iyer et al. 2008; Li et al. 2013). The morc gene was first identified in a mouse by its spontaneous autosomal recessive mutation. This mutation results in the arrest of spermatogenesis in meiosis and reduced testicular mass (Watson et al. 1998). Four convergent and least characterized MORC family members: MORC1 (CT33 or ZCW6), MORC2 (ZCWCC1, ZCW3, KIAA0852, CMT2Z or AC004542.C22.1), MORC3 (ZCWCC2, ZCW5, KIAA0136 or NXP2), and MORC4 (ZCWCC2, ZCW4, DJ75H8.2, or FLJ11565) have been reported in humans (Li et al. 2013; Hong et al. 2017)). The common structural features of the MORC family of proteins include GHKL (gyrase, hsp90, histidine kinase, and MutL)-ATPase domain, ZF-CW domain, a nuclear localization signal (NLS), and coiled-coil domains (Li et al. 2013). Based on their ZF-CW domain architectures, MORC1 and MORC2 are grouped under subfamily I; MORC3 and MORC4 are assigned under subfamily IX (Perry and Zhao 2003). Emerging evidence reveals that MORC proteins have been associated with cancer development. In this review, we focus on the MORC2 protein and its associated functions in cancer.

Fig. 1.

Chromatin structure in a eukaryotic cell. Chromatin is composed of histone octamer, and DNA exists in two major forms, heterochromatin and euchromatin. Chromatin remodelers play an essential role in the interconversion of two chromatin forms

MORC2 expression

MORC2 is a ubiquitously expressed protein in human cells and tissues and was found to be upregulated in most cancers including the lung, kidney, prostate, esophagus, breast, liver, colon, stomach, ovary, pancreas, skin, endometrium, nasopharynx, and bladder (Ding et al. 2018). MORC2 also shows high expression levels in the mouse ovary, testis, and brain (Wang et al. 2010). MORC2 expression levels were more elevated in high-grade cancer tissues and associated with poor overall survival and unfavorable pathological conditions in breast cancer and non-small cell lung cancer (Ding et al. 2018).

MORC2 primary structure

MORC2 gene is located on the reverse strand at the region q12.2 of chromosome 22. Among 13 transcripts, 2 isoforms have complete coding sequence: MORC2 isoform-1 (1032 amino acids) and MORC2 isoform-2 (970 amino acids). MORC2 protein isoform-2 lacks 62 amino acid residues from the N-terminal region, which are present in its canonical form. Irrespective of the difference, both isoforms of MORC2 are fully functional.

MORC2 like other MORCs have conserved domains such as (i) GHKL-type ATPase which is a split ATPase composed of GHKL and S5 domain (Douse et al. 2018); (ii) ZF-CW, reader domain which has not been well characterized, functionally (Andrews et al. 2016; Liu et al. 2016); and (iii) coiled coils, which known to play a role in protein-protein interactions (Xie et al. 2019). These structural domains can be present as a single copy, such as ZF-CW, or multiple copies, such as coiled coils (Fig. 2). Although coiled coils are present in multiple copies, each single domain has its own unique interactome and associated function. For instance, coiled coil 1 of MORC2 binds DNA and plays a vital role in chromatin interaction (Douse et al. 2018), whereas the C-terminal coiled coil facilitates its dimerization, which is essential for its role in DNA damage repair and cell survival (Xie et al. 2019). Along with the conserved domains, MORC2 has several unique domains such as the chromo-like domain and the proline-rich domain.

Fig. 2.

Schematic representation of MORC2 domain architecture and its domain-specific interacting partners. Conserved ATPase domain in brown (1–469 a.a.) is a split module composed of GHKL (1–278 a.a.) and S5 (323–469 a.a.) domains. PHD-X/ZF-CW or zinc finger domain is represented as ZF (490–544 a.a.) in purple and multiple coiled coils in gray as CC-1 or coiled coil-1 (282–362 a.a.), CC-2 or coiled coil-2 (547–584 a.a.), CC-3 or coiled coil-3 (741–761 a.a.), CC-4 or coiled coil-4 (966–1016 a.a.), and CC-5 or coiled coil-5 (1024–1032 a.a.). Two unique domains, proline-rich domain (PRD) (601–734 a.a.) and chromo-like domain (CLD) (790–854 a.a.), are shown in green and blue, respectively. Solid lines indicate MORC2 region required for interaction with its interacting partners PARP1, NAT10, C/EBPα, HSPA8, LAMP2A, CTNND1, TASOR and MPP8, PAK1, and ACLY

MORC2 localization

MORC2 can be localized to both the nucleus and cytoplasm as it is containing the nuclear localization signal, NLS (657-781 a.a), and the cytoplasm localization signal or nuclear export signal, NES (481-657 a.a.). However, MORC2 is predominantly localized to the nucleus compared to the cytoplasm as the NLS predominates over the NES (Wang et al. 2010). Within the nucleus, it is highly involved with the regulation of gene transcription (Guddeti et al. 2021), chromatin remodeling (Li et al. 2012), and DNA damage response (Zhang and Li 2019). Apart from the nuclear functions, MORC2 also regulates cytosolic functions like lipogenesis and adipogenesis (Sánchez-Solana et al. 2014).

Protein degradation in eukaryotes is largely carried out by the autophagy-lysosome system and the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Autophagy regulates the degradation of long-lived proteins and organelles in lysosomes whereby the ubiquitin-proteasome system targets short-lived regulatory proteins (Ravid and Hochstrasser 2008). Autophagy in mammalian cells basically consists of three types – microautophagy, macroautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy (CMA) (Mizushima et al. 2008). In CMA, proteins having a KFERQ-like motif are recognized by HSPA8 which brings about selective degradation of the protein. MORC2 amino acid analysis showed the presence of two putative KFERQ-like motifs in its structure, and it has been found to be degraded in lysosomes by CMA (Yang et al. 2020). Serum deprivation promotes MORC2 translocation from the nucleus to cytoplasm where a cytosolic lysosomal protein HSPA8 and LAMP2A interact with MORC2 at regions 352-356 a.a. and 628-632 a.a., respectively, facilitating lysosomal degradation of MORC2 by CMA (Yang et al. 2020). Basically, the transcriptional and chromatin regulatory role of MORC2 associated with oncogenesis is attributed to its subcellular localization, from the cytoplasm to nucleus (Wang et al. 2010).

MORC2 in cancer

Induced expression of MORC2 in cancer cells is associated with proliferation, invasion, migration, metastasis, and tumorigenesis (Pan et al. 2018; Zhang et al. 2018; Liao et al. 2019). MORC2 overexpression is implicated in radioresistance, chemoresistance, and endocrine resistance in cancer progression (Pan et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2020; Yang et al. 2020). Emerging studies revealed that MORC2, through its ATPase-dependent chromatin remodeling activity, plays an important role in DNA damage response (DDR) by enabling the recruitment of DNA repair proteins to the sites of DNA lesions (Li et al. 2012; Zhang and Li 2019; Xie et al. 2019). Recent studies demonstrated that MORC2, by regulating glucose metabolism and lipogenesis, is also involved in cancer metabolic reprogramming (Sánchez-Solana et al. 2014; Guddeti et al. 2021).

MORC2 interacting partners and their associated functions in tumorigenesis

Although MORC2 is associated with chromatin remodeling, it does not have the ability to directly catalyze the modification. The function of MORC2 is attributed to its domain organization, where distinct domains interact with modifiers to modulate the function of MORC2 or its downstream targets. Known interacting partners were summarized in Fig. 2 and Table 1.

Table 1.

MORC2 interacting partners and the functional outcome of the interaction in cancer

| MORC2 PPIs | Mechanism | Functional outcome | Type of cancer | Reference (PMID) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MYC | Transcriptional regulation of LDHA expression and activity | Reprogramming of glucose metabolism | Breast cancer | Guddeti et al. 2021 |

| ACLY | Increased ACLY activation | Enhanced lipid synthesis and adipocyte differentiation | Breast cancer | Sánchez-Solana et al. 2014 |

| PAK1 | Phosphorylated MORC2 confers increased ATPase activity to remodel chromatin | DNA repair | Cervical cancer and breast cancer | Li et al. 2012 |

|

PARP1 NAT10 |

Activation of chromatin remodeling activity of PARylated MORC2 upon DNA damage and stabilization of PARP1 by acetylation | DNA repair and cell survival | Breast cancer | Zhang and Li 2019 |

|

PRKACA HSPA8 LAMP2A |

Stabilized MORC2 upon induction with anti-estrogens exerts an oncogenic effect | Endocrine resistance to cancer cells | Breast cancer | Yang et al. 2020 |

| HDAC4 | Transcriptional regulation of CAIX enzyme | Growth and survival | Gastric cancer | Shao et al. 2010 |

|

NAT10 SIRT2 PP1y |

Enhanced acetylation of MORC2 by NAT10 upon DNA damage facilitates dephosphorylation of H3T11P and transcriptional repression of CDK1 and Cyclin B1 to arrest cell cycle at the G2 checkpoint | Ensures cell survival by G2/M cell 1cycle arrest upon DNA damage | Breast cancer | Liu et al. 2020 |

| DNMT3A | Transcriptional repression of Hippo signaling regulators, NF2 and KIBRA | Cancer stemness and proliferation | Liver cancer | Wang et al. 2018 |

| HDAC1 | Transcriptional repression of p21 | Cell proliferation | Gastric cancer | Zhang et al. 2015 |

| PAK1 | Phosphorylated MORC2 promote the expression of cyclin D-CDKs, pushing cells from G1 to S phase | Cell proliferation | Gastric cancer | Wang et al. 2015 |

| C/EBPα | Sumoylation mediated degradation of C/EBPα by MORC2 | Cell proliferation | Gastric cancer | Liu et al. 2019b |

| EZH2 HSF1 | Transcriptional silencing of ArgBP2 expression | Cell proliferation, invasion and migration | Gastric cancer | Tong et al. 2015, 2018 |

| SIRT1 | Transcriptional downregulation of NDRG1 | Cell invasion, migration, and metastasis | Colorectal cancer | Liu et al. 2019a |

| hnRNPM | Enhanced interaction mediates the splicing switch from epithelial to the mesenchymal isoform of CD44 | Cell invasion, migration, and metastasis | Breast cancer | Zhang et al. 2018 |

| CTNND1 | Unknown | Cell invasion, migration and metastasis | Breast cancer | Liao et al. 2017 |

MORC2 role in cancer cell proliferation, invasion, and migration

Upregulated MORC2 inhibits tumor suppressor genes (Tong et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2018; Liu et al. 2019a) or activates oncogenes (Liu et al. 2018) as a coregulator (Table 1) in order to promote cancer cell proliferation, invasion, migration, and metastasis. The regulatory switch of MORC2 depends on the interactome, cell type, and signal; for instance, MORC2 upregulates C/EBPα in adipocytes (Sánchez-Solana et al. 2014) whereas it downregulates C/EBPα (interacting region: 719-843) in gastric cancer cells by different mechanisms (Liu et al. 2019b). This MORC2 regulated C/EBPα expression was found to cause cell proliferation and tumorigenesis (Liu et al. 2019b).

Carbonic anhydrase IX (CAIX) is a transmembrane isoenzyme that regulates tumor cell growth and survival (Robertson et al. 2004). CAIX was found to play a key role in early gastrogenesis as CAIX knockout mice show increased cell proliferation (Gut et al. 2002). Shao et al. reported that the MORC2-HDAC4 complex is recruited to the CAIX promoter and causes repression of CAIX transcription in gastric cancer cells (Shao et al. 2010). MORC2 also interacts with HDAC1 to form a complex which then gets recruited to the p21 promoter in a p53-independent manner. This results in downregulation of p21 expression leading to cell cycle progression in gastric cancer cells (Zhang et al. 2015). Furthermore, Wang et al. demonstrated that PAK1-mediated MORC2 phosphorylation is one of the lead causes for gastric tumorigenesis (Wang et al. 2015). MORC2 in combination with DNA methyltransferase 3A (DNMT3A) recruits at the promoters of neurofibromatosis 2 and KIBRA, controls their DNA hypermethylation and transcriptional repression, and thereby promoted cancer stemness and tumorigenesis of hepatocellular carcinoma cells (Wang et al. 2018).

In addition to proliferation, MORC2 also regulates the invasion and migratory functions in different types of cancers. The ArgBP2 protein is known for its repressive functions in the proliferation, cell migration, and invasion of gastric cancer cells (Taieb et al. 2008). MORC2 was found to regulate the transcriptional repression of ArgBP2 by forming a complex either with EZH2 or HSF1 and binding to the ArgBP2 promoter, thereby modulating the proliferative, invasion, and migratory functions of cancer cells (Tong et al. 2015, 2018). In addition, MORC2 has been shown to downregulate NDRG1 in association with histone deacetylase sirtuin 1(SIRT1) and activate colorectal cancer metastasis (Liu et al. 2019a). A recent study established MORC2 role in breast cancer invasion and metastasis by interacting with catenin delta 1 (CTNND1) (Liao et al. 2017). Similarly, the interaction between mutant MORC2 (M276I) and hnTNPM (heterogenous nuclear ribonucleoprotein M) stimulated the splicing-based switch of CD44 from the epithelial isoform to the mesenchymal isoform, leading to an epithelial to mesenchymal transition, which is a prerequisite for the metastasis (Zhang et al. 2018).

MORC2 role in metabolism

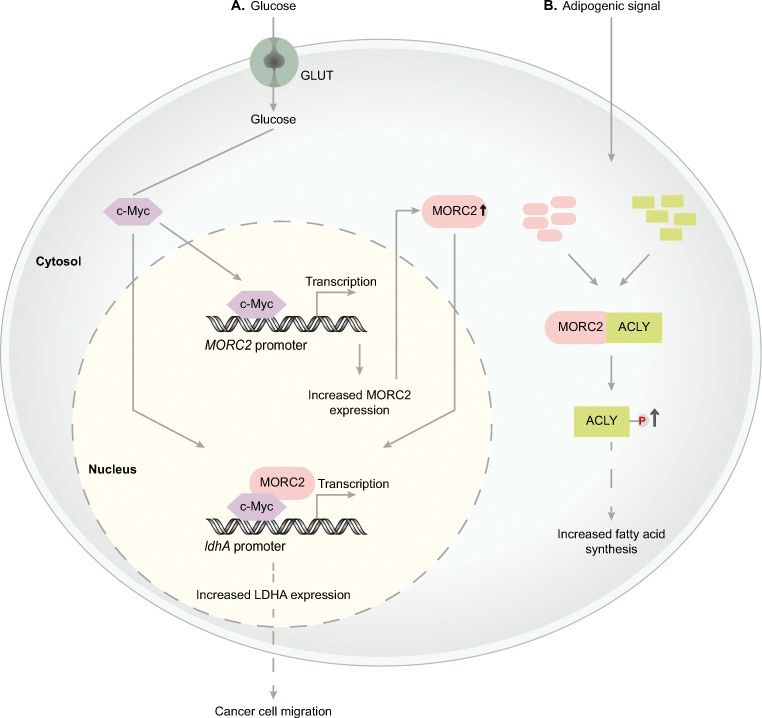

To meet the continuous energy requirements for tumor growth and progression, cancer cells undergo metabolic reprogramming, which is considered one of the important hallmarks of cancer (Hanahan and Weinberg 2011). Even if there is little to no availability of oxygen, cancer cells can rely on glycolysis rather than mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation for their energy requirements – with this phenomenon known as the Warburg effect (Heiden et al. 2009). Recently we identified that MORC2 plays a key role in rewiring glucose metabolism to promote breast cancer cell migration (Fig. 3) (Guddeti et al. 2021). We found that MORC2 is a glucose-inducible gene and transcriptional target of c-Myc where c-Myc specifically binds to the E-box sequence (5’-CACGTG-3’) of the MORC2 promoter and regulates the expression of MORC2 under high glucose concentration in cancer cells (Guddeti et al. 2021). Further to this, we noticed a positive correlation between MORC2 expression and the expression of a number of glycolytic enzymes (e.g., hexokinase 1, lactate dehydrogenase A, phosphofructokinase liver type (PFKL) and phosphofructokinase platelet isoform (PFKP) in breast cancer patients. It was found that c-Myc stimulates the expression of MORC2 and consequently interacts with MORC2 in a feed-forward loop mechanism, in order to transcriptionally regulate LDHA (lactate dehydrogenase A) expression (Fig. 3A) and in turn the enzyme activity. LDHA activity was found to be very crucial for cancer cell migration (Guddeti et al. 2021).

Fig. 3.

Model depicting the role of MORC2 in cancer metabolism. A Schematic representation of MORC2 regulation of LDHA expression and function: high glucose concentration in the culture medium stimulates the induction of MORC2 expression in cancer cells. Once, MORC2 is induced, it forms a complex with c-Myc and gets recruited to LDHA promoter to induce LDHA expression, which in turn is responsible for cancer cell migration. B A model representing the interaction between MORC2 and ACYL: adipogenic signal promotes the interaction between MORC2 and ACYL in the cytosol leading to the activation of ACYL. This activated ACYL is essential for increased fatty acid synthesis in cancer cells. Bold black arrows represent either the induction of MORC2 or increased activation of ACYL proteins

A recent study found that MORC2 promotes lipogenesis and adipocyte differentiation by posttranslational activation of ATP-citrate lyase (ACLY) enzyme, which catalyzes the formation of acetyl-coA (Sánchez-Solana et al. 2014). Adipogenic signals facilitate MORC2 and ACLY protein-protein interaction where ACYL was found to interact with MORC2 region 63-718 a.a. with the interaction taking place within the cytosol (Table 1), to promote ACLY phosphorylation and, thereby, also promote its activity (Sánchez-Solana et al. 2014). Activated ACLY enzyme results in increased production of acetyl-CoA, which is an essential building block for the fatty acid synthesis (Fig. 3B).

The microRNA (miRNA) sponges contain complementary binding sites to a specific miRNA. miRNA sponges bind to the target miRNAs through these complementary sequences and inhibit the action of miRNAs (Ebert and Sharp 2010). Interestingly in cholangiocarcinoma (CCA) cells, Su et al. identified that circular RNA CircDNM3OS is a sponging miR of miR-145-5p and MORC2 is a specific target gene of miR-145-5p (Su et al. 2021). Their study revealed that in CCA cells, MORC2 expression levels were elevated by circular RNA circDNM3OS via sponging miR-145-5p in order to modulate glutamine metabolism and malignancy. Furthermore, MORC2 upregulation also increased glutamine consumption, its conversion to α-ketoglutarate, and ATP levels in CCA cells (Su et al. 2021). Together, these findings established a promising role for MORC2 in cancer metabolic reprogramming.

MORC2 role in DNA repair

Posttranslational modification of a protein can regulate its specific function; for instance, upon DNA damage, the balance of activity between acetyltransferase NAT10 and deacetylase SIRT2 is shifted to affect acetylation of MORC2 in breast cancer cell lines (Liu et al. 2020). Enhanced acetylation of MORC2 (K767Ac) ensures both resistance to DNA damaging agents and breast cancer cell survival by regulating cell cycle progression at the G2-M checkpoint (Liu et al. 2020). Along with acetylation, MORC2 phosphorylation (Wang et al. 2015; Yang et al. 2020) and PARylation (Zhang and Li 2019) by virtue of its interaction with PAK1 (interacting region: 719-843) and PARP1 (interacting region: 490-718), respectively, have also been shown to play an essential role in maintaining high levels of MORC2 in cancer cells, thereby facilitating its role in DNA repair.

MORC2 role in endocrine resistance

Aberrant activation of estrogen signaling is one of the major route causes for breast cancer progression and pathogenesis (Yager and Davidson 2006). Antiestrogen treatment using drugs like tamoxifen (TAM) and fulvestrant (FUL) was found to be more effective in estrogen-positive breast tumors but resulted in endocrine resistance (Mo et al. 2013; Ignatov et al. 2010; Ignatov et al. 2011; Yang et al. 2020). Yang et al. reported that TAM and FUL stabilize MORC2 in a GPER1 (G protein-coupled estrogen receptor 1)-dependent manner (Yang et al. 2020). The underlying mechanism included activation of PRKACA (protein kinase cAMP-activated catalytic subunit alpha) by GPER1, with phosphorylation of MORC2 at threonine 582 (T582), resulting in its decreased interaction with HSPA8 and LAMP2A. This resulted in MORC2 protection from CMA-mediated lysosomal degradation, leading to the MORC2 stabilization and in turn endocrine resistance (Yang et al. 2020).

Conclusions

MORC2 functions as a scaffolding protein, and its unique domain architecture facilitates protein-protein interactions. These interactions of MORC2 are found to be important for proliferation, invasion, migration, cancer stemness, DNA repair mechanisms, and metabolism in cancer. Current knowledge about MORC2 interacting partners is quite basic and warrants more efforts to identify novel interacting partners for MORC2. This will help in developing new therapeutic strategies to disrupt the interactions of MORC2 with specific protein partners in tumor cells for effective targeting of cancers.

Acknowledgements

PSB thanks IISER Tirupati for the support. RKG is thankful to the Department of Biotechnology, Government of India, for awarding SRF, and NC is thankful to IISER Tirupati, India, for awarding JRF and providing the financial support.

Author contribution

RKG, NC, and PSB wrote this review.

Date availability

Not applicable

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rohith Kumar Guddeti and Namita Chutani contributed equally to this work.

References

- Andrews FH, Tong Q, Sullivan KD et al (2016) Multivalent chromatin engagement and inter-domain crosstalk regulate MORC3 ATPase. Cell Rep. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.08.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Dawson MA, Kouzarides T. Cancer epigenetics: from mechanism to therapy. Cell. 2012;150:12–27. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding QS, Zhang L, Cheng WB, et al. Aberrant high expression level of MORC2 is a common character in multiple cancers. Hum Pathol. 2018;76:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2018.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douse CH, Bloor S, Liu Y et al (2018) Neuropathic MORC2 mutations perturb GHKL ATPase dimerization dynamics and epigenetic silencing by multiple structural mechanisms. Nat Commun 9. 10.1038/s41467-018-03045-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Ebert MS, Sharp PA. MicroRNA sponges: progress and possibilities. RNA. 2010;16:2043–2050. doi: 10.1261/rna.2414110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farooqi AA, Fayyaz S, Poltronieri P et al (2020) Epigenetic deregulation in cancer: enzyme players and non-coding RNAs. Semin Cancer Biol. 10.1016/j.semcancer.2020.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ferlay J, Ervik M, Lam F, et al. Global cancer observatory: cancer today. Lyon: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi Cancer’s epigenetic drugs: where are they in the cancer medicines? Pharm J. 2020;20:367–379. doi: 10.1038/s41397-019-0138-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guddeti RK, Thomas L, Kannan A et al (2021) The chromatin modifier MORC2 affects glucose metabolism by regulating the expression of lactate dehydrogenase A through a feed forward loop with c-Myc. FEBS Lett. 10.1002/1873-3468.14062 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gut MO, Parkkila S, Vernerová Z, et al. Gastric hyperplasia in mice with targeted disruption of the carbonic anhydrase gene Car9. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:1889–1903. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanahan D, Weinberg RA. Hallmarks of cancer: the next generation. Cell. 2011;144:646–674. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heiden MGV, Cantley LC, Thompson CB. Understanding the Warburg effect: the metabolic requirements of cell proliferation. Science. 2009;324:1029–1033. doi: 10.1126/science.1160809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong G, Qiu H, Wang C, et al. The emerging role of MORC family proteins in cancer development and bone homeostasis. J Cell Physiol. 2017;232:928–934. doi: 10.1002/jcp.25665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignatov A, Ignatov T, Roessner A, et al. Role of GPR30 in the mechanisms of tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer MCF7- cells. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010;123:87–96. doi: 10.1007/s10549-009-0624-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ignatov A, Ignatov T, Weissenborn C, et al. G-protein-coupled estrogen receptor GPR30 and tamoxifen resistance in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;128:457–466. doi: 10.1007/s10549-011-1584-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer LM, Abhiman S, Aravind L (2008) MutL homologs in restriction-modification systems and the origin of eukaryotic MORC ATPases. Biol Direct 3. 10.1186/1745-6150-3-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Kouzarides T. Chromatin modifications and their function. Cell. 2007;128:693–705. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DQ, Nair SS, Kumar R. The MORC family: New epigenetic regulators of transcription and DNA damage response. Epigenetics. 2013;8:685–693. doi: 10.4161/epi.24976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li DQ, Nair SS, Ohshiro K, et al. MORC2 signaling integrates phosphorylation-dependent, ATPase-coupled chromatin remodeling during the DNA damage response. Cell Rep. 2012;2:1657–1669. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2012.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao G, Liu X, Wu D, et al. MORC2 promotes cell growth and metastasis in human cholangio-carcinoma and is negatively regulated by miR-186-5p. Aging. 2019;11:3639–3649. doi: 10.18632/aging.102003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liao XH, Zhang Y, Dong WJ, et al. Chromatin remodeling protein MORC2 promotes breast cancer invasion and metastasis through a PRD domain-mediated interaction with CTNND1. Oncotarget. 2017;8:97941–97954. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu HY, Liu YY, Yang F, et al. Acetylation of MORC2 by NAT10 regulates cell-cycle checkpoint control and resistance to DNA-damaging chemotherapy and radiotherapy in breast cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:3638–3656. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkaa130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Shao Y, He Y, et al. MORC2 promotes development of an aggressive colorectal cancer phenotype through inhibition of NDRG1. Cancer Sci. 2019;110:135–146. doi: 10.1111/cas.13863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J, Zhang Q, Ruan B, et al. MORC2 regulates C/EBPα-mediated cell differentiation via sumoylation. Cell Death Differ. 2019;26:1905–1917. doi: 10.1038/s41418-018-0259-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu M, Sun X, Shi S. MORC2 enhances tumor growth by promoting angiogenesis and tumor-associated macrophage recruitment via Wnt/β-catenin in lung cancer. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;51:1679–1694. doi: 10.1159/000495673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Tempel W, Zhang Q, et al. Family-wide characterization of histone binding abilities of human CW domain-containing proteins. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:9000–9013. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M116.718973. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, Klionsky DJ. Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature. 2008;451:1069–1075. doi: 10.1038/nature06639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mo Z, Liu M, Yang F, et al. GPR 30 as an initiator of tamoxifen resistance in hormone-depedendent breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 2013;15:R114. doi: 10.1186/bcr3581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan MA, Shilatifard A. Chromatin signatures of cancer. Genes Dev. 2015;29:238–249. doi: 10.1101/gad.255182.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nair SS, Kumar R. Chromatin remodeling in cancer: a gateway to regulate gene transcription. Mol Oncol. 2012;6:611–619. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2012.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Z, Ding Q, Guo Q et al (2018) MORC2, a novel oncogene, is upregulated in liver cancer and contributes to proliferation, metastasis and chemoresistance. Int J Oncol. 10.3892/ijo.2018.4333 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Perry J, Zhao Y. The CW domain, a structural module shared amongst vertebrates, vertebrate-infecting parasites and higher plants. Trends Biochem Sci. 2003;28:576–580. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2003.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ravid T, Hochstrasser M. Diversity of degradation signals in the ubiquitin-proteasome system. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:679–689. doi: 10.1038/nrm2468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson N, Potter C, Harris AL. Role of carbonic anhydrase IX in human tumor cell growth, survival, and invasion. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6160–6165. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-03-2224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sahu RK, Singh S, Tomar RS (2020) The mechanisms of action of chromatin remodelers and implications in development and disease. Biochem Pharmacol 180 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sánchez-Solana B, Li DQ, Kumar R. Cytosolic functions of MORC2 in lipogenesis and adipogenesis. Biochim Biophys Acta, Mol Cell Res. 2014;1843:316–326. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2013.11.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shao Y, Li Y, Zhang J, et al. Involvement of histone deacetylation in MORC2-mediated down-regulation of carbonic anhydrase IX. Nucleic Acids Res. 2010;38:2813–2824. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma S, Kelly TK, Jones PA. Epigenetics in cancer. Carcinogenesis. 2010;31:27–36. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgp220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su Y, Yu T, Wang Y, et al. Circular RNA CircDNM3OS functions as a miR-145-5p sponge to accelerate cholangiocarcinoma growth and glutamine metabolism by upregulating morc2. OncoTargets and Therapy. 2021;14:1117–1129. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S289241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swygert SG, Peterson CL. Chromatin dynamics: interplay between remodeling enzymes and histone modifications. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta - Gene Regulatory Mechanisms. 2014;1839:728–736. doi: 10.1016/j.bbagrm.2014.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taieb D, Roignot J, André F, et al. ArgBP2-dependent signaling regulates pancreatic cell migration, adhesion, and tumorigenicity. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4588–4596. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Y, Li Y, Gu H, et al. HSF1, in association with MORC2, downregulates ArgBP2 via the PRC2 family in gastric cancer cells. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol basis Dis. 2018;1864:1104–1114. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tong Y, Li Y, Gu H, et al. Microchidia protein 2, MORC2, downregulates the cytoskeleton adapter protein, ArgBP2, via histone methylation in gastric cancer cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;467:821–827. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.10.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang G, Song Y, Liu T, et al. PAK1-mediated MORC2 phosphorylation promotes gastric tumorigenesis. Oncotarget. 2015;6:9877–9886. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang GL, Wang CY, Cai XZ, et al. Identification and expression analysis of a novel CW-type zinc finger protein MORC2 in cancer cells. Anat Rec. 2010;293:1002–1009. doi: 10.1002/ar.21119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T, Yi QZ, Zhi WL, et al. Epigenetic restriction of Hippo signaling by MORC2 underlies stemness of hepatocellular carcinoma cells. Cell Death Differ. 2018;25:2086–2100. doi: 10.1038/s41418-018-0095-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson ML, Zinn AR, Inoue N, et al. Identification of more (microrchidia), a mutation that results in arrest of spermatogenesis at an early meiotic stage in the mouse. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1998;95:14361–14366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.24.14361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie HY, Zhang TM, Hu SY et al (2019) Dimerization of MORC2 through its C-terminal coiled-coil domain enhances chromatin dynamics and promotes DNA repair. Cell Communication and Signaling 17. 10.1186/s12964-019-0477-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Yager JD, Davidson NE. Estrogen carcinogenesis in breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:270–282. doi: 10.1056/nejmra050776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F, Xie HY, Yang LF, et al. Stabilization of MORC2 by estrogen and antiestrogens through GPER1- PRKACA-CMA pathway contributes to estrogen-induced proliferation and endocrine resistance of breast cancer cells. Autophagy. 2020;16:1061–1076. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2019.1659609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Z, Chen Y, Cao W, Shyh-Chang N (2020) Chromatin-modifying drugs and metabolites in cell fate control. Cell Prolif 53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Zhang FL, Cao JL, Xie HY et al (2018) Cancer-associated MORC2-mutant M276I regulates an hnRNPM-mediated CD44 splicing switch to promote invasion and metastasis in triple-negative breast cancer. Cancer Res. 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-1394 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Zhang L, Li DQ. MORC2 regulates DNA damage response through a PARP1-dependent pathway. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:8502–8520. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Q, Song Y, Chen W, et al. By recruiting HDAC1, MORC2 suppresses p21Waf1/Cip1 in gastric cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;6:16461–16470. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.3889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable