Abstract

Background

Health-related patient reported outcome measures are considered essential to determine the impact of disease on the life of individuals. Aim of this study is to culturally adapt the Italian version of the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI). The secondary aim is to evaluate psychometric proprieties in patients with non-specific shoulder pain.

Methods

The current study is an analysis of a sample of 59 adult patients with non-specific shoulder pain. The SPADI was translated and cross-culturally adapted, and then psychometric properties were tested. Participants completed the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index-Italian (SPADI-I), 36-item short form health survey, the Oxford Shoulder Score, the Disability of Arm, Shoulder, and Hand scale and a pain intensity visual analogue scale.

Results

SPADI-I included two domains. Internal consistency analysis showed good values for total (α = 0.84) and subscales (α = 0.94 and α = 0.76). For construct validity, there was good correlation between the visual analogue scale, the Oxford Shoulder Score, the DASH and the SPADI-I total score and subscales. Standard error of measurement and minimally detectable change were calculated.

Conclusions

The SPADI-I was culturally adapted into Italian. SPADI-I is centred on pain and disability of the shoulder only and can be considered as a useful tool in daily clinical practice for assessing musculoskeletal non-specific shoulder pain because of its good internal consistency and validity. Further studies should focus on other psychometric proprieties such as test re-test reliability, responsiveness and clinical interpretability to improve the available clinimetrics of the tool.

Keywords: Shoulder Pain and Disability Index, painful shoulder, non-specific shoulder pain, validation, patient reported outcome measure

Introduction

Shoulder pain is a common musculoskeletal condition among the general population with lifetime prevalence ranging from 7% to 67%.1 When pain becomes intense and persistent, it could lead to disability or impair activities of daily living and sleep quality.2 Health-related patient reported outcome measures (PROMs) are considered essential to determine the impact of disease on the life of individuals, taking account not only the clinical diagnosis of a disease but also its impact on patient perception.3 PROMs for the evaluation of shoulder disability are useful tools for clinicians to evaluate the patients’ symptoms after an intervention. Many shoulder disability questionnaires are available, a few of which are adapted and validated in Italian such as the Disability of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand scale (DASH), the Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS) and the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI).

The SPADI was developed to measure the pain and disability associated with shoulder pathology. The SPADI is a self-administered index consisting of 13 items divided into two subscales: pain and disability; a 5-item subscale that measures pain and an 8-item subscale that measures disability.4 It has reasonably good psychometric properties, so the clinician can be sure that the scores that are obtained are an accurate reflection of the patient's state. If the measurement of pain and disability are of primary interest, the SPADI is a useful tool for a wide range of patients presenting with most shoulder conditions.5 There are two versions of the SPADI; the original version has each item scored on a visual analogue scale (VAS), while a second version has items scored on an Numeric rating scale (NRS).5 The latter version was developed to make the tool easier to administer and score.6 Both versions take less than 5 min to complete.6,7 Each subscale is summed and transformed to a score out of 100, with a higher score indicating greater impairment or disability. In the original version, the patient was instructed to place a mark on the VAS for each item that best represented their experience of their shoulder condition over the last week.4 In the NRS version, the VAS is replaced by a 0–10 scale and the patient is asked to circle the number that best describes the pain or disability.6 The total score is derived in the same manner as the VAS version. In each subscale, patients may mark one item only as not applicable and the item is omitted from the total score. If a patient marks more than two items as non-applicable, no score is calculated.4

To date, the SPADI has been used in both primary care on mixed diagnosis and surgical patient populations including rotator cuff disease,8 osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis, adhesive capsulitis,9 joint replacement surgery10 and in a large population-based study of shoulder symptoms. Translation and cultural adaptation of the SPADI questionnaire has been done in German,10 Portuguese,11 Arabic,12 Tamil (Indian),13 Turkish,14 Slovene15 and Greek16 in order to detect pain and functional status of patients with a wide range of shoulder conditions. Previously, the SPADI has already been validated in Italian to assess shoulder dysfunction in patients treated for neck cancer17 and in Italian patients after shoulder surgery for anterior instability.18 The authors have chosen to translate this scale for its excellent psychometric properties demonstrated in the studies just mentioned. It has good validity and reliability and excellent psychometric properties both in its original version and in the translated versions.

Unfortunately, the samples of Italian population examined in the literature are limited to those who had a neck dissection17 and those who had experienced episodes of instability.18 The SPADI is recommended and frequently used with patients with multiple shoulder conditions. Psychometric properties of a PROM are influenced by many different factors (e.g. social, environmental, clinical).19 The validity of the SPADI are unknown in Italian patients with non-specific shoulder pain20 and for a reliable and valid use of this instrument in Italian, it is mandatory to assess the SPADI measurement properties in a representative sample of Italian patients.21

Therefore, the purpose of the present study was to translate and culturally adapt the SPADI from English to an Italian version (Shoulder Pain and Disability Index-Italian (SPADI-I)). The secondary aim was to evaluate psychometric proprieties in patients with non-specific shoulder pain.

Material and methods

Cross-cultural adaptation

A two-stage observational study was conducted. The first stage comprised the translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the SPADI, while the second stage consisted of an evaluation of the domains of the scale, internal consistency, construct validity and standard error measurement of the Italian version of the SPADI.

In accordance with Beaton's guidelines,22 the scale in the first step was translated from English to Italian by two females, one healthcare professional (i.e. a physiotherapist not included in this study) and one non-healthcare person (i.e. a high-school English teacher); the two translations have been compared and a last version has been extrapolated to have a single translated version, the first Italian version. This version was once retranslated by two native English speakers (both English teachers at the authors University) to check if there was any correspondence with the original scale. From these two back-translations, a single version was obtained and translated again into Italian by a third English high-school teacher that was adopted as a pre-final version.

The pre-final version of the scale was administered to 30 patients with painful shoulder conditions. These patients were asked about any difficulties in understanding and completing the questionnaire. There were no unclear words or poorly proposed sentences according to this initial group of patients. After that, a committee of experts composed of translators, physiotherapists and promoters of the study, met to discuss the correspondence of the text submitted to the aforementioned group of patients and finally obtained the final version of the questionnaire, which represents the version used in this study.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

As proposed for other body regions (e.g. lumbar spine, cervical spine), as well as in the shoulder complex, there is a growing awareness of the very limited ability to identify a specific structure responsible for the patient's symptoms.20 The literature has shown poor reliability of clinical physical tests23 and diagnostic imaging,24,25 making it unlikely to identify the structure causing a patient's symptomatology, the classification developed by Ristori et al.20 was used with the aim to classify patients according to recent evidence based clinical tools. The diagnostic triage proposed by Ristori et al. adopted a classification system similar to the one already adopted for other regions: red flags,26 specific pain,27,28 non-specific pain. Red flags are serious diseases (i.e. systemic, infectious, neoplastics, fractures, dislocation) masquerading as musculoskeletal conditions that are out of the scope of practice of a physiotherapist.26 Specific shoulder pain indicates that symptoms could refer to a pathology that has a clear structural, patho-anatomic or patho-physiologic origin.20 Finally, the physiotherapist can classify as non-specific shoulder pain29,30 the patients presenting clinical features that do not belong to the two categories described above. A population of subjects with non-specific shoulder pain were chosen because this population is more common in daily clinical practice of physiotherapists.

After medical screenings to exclude red flags,26 patients with shoulder pain that increases with movements against resistance31 and with negative X-ray (no signs of fracture, dislocation or severe osteoarthrosis) were included. Patients were excluded according to the following criteria: younger than 18 years old, unable to understand Italian and positive case history for traumatic shoulder pathology and for cognitive impairments. Furthermore, we excluded also patients with specific shoulder pain secondary to massive rotator cuff tear, fractures, serious joint diseases (positive X-ray for severe arthrosis or bone's undefined masses), frozen shoulder (i.e. stiff shoulder, clear limitation on external-rotation at arm by side),32 shoulder instability (i.e. positive apprehension test)33 and painful shoulder linked to cervical dysfunctions.31The correlation between shoulder or arm pain and cervical dysfunction was assessed by administration of repeated movements of the cervical spine, that is recognised to be a valid clinical approach34,35 for confirming the cervical origin of shoulder and back referred symptoms. Moreover, Wainner's cluster (Spurling test, Distraction test, deficit in cervical rotation, Upper Limb Neurodinamic Test -ULNT1-) was administered to patients to exclude pain of radicular origin.36

All procedures involving human participants were in accordance with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments. This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Lecce, Italy with protocol n.14 of 15th of January 2018. The final version of the SPADI-I was included in a booklet that also contained the Italian versions of the OSS, the DASH scale, the VAS for shoulder pain and the 36-item short form health survey (SF-36). Personal information and informed consent were obtained from all of the patients to participate in the study.

Scales for comparative analysis

The DASH was developed by the Institute for Work and Health and the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons37 and consists of 30 questions inquiring symptoms and functions of the upper limbs which are affected by orthopaedic or neurologic disorders. These provide a single total score, the DASH function/symptoms (DASH-FS) scale, which is a summation of the responses on a one-to-five scale, after transformation to a zero (no disability) to 100 (severe disability) scale. In addition to the 30-item core, there are two optional four-item question sets, the DASH sport/music and DASH work, which are scored similarly.37 The questions test the degree of difficulty in performing a variety of physical activities because of arm, shoulder or hand problems (21 items). They also investigate the severity of pain, activity-related pain, tingling, weakness and stiffness (five items) and the effect of the upper limb problem on social activities, work, sleep and self-image (four items).38 The two optional domains contain activity-specific items concerning the performance of sports and/or the playing of musical instruments, and the ability to work. All the items have five response choices ranging from “no difficulty or no symptoms” (scores 1 point) to “unable to perform activity or severe symptoms” (scores 5 points).37 In 2003, the DASH was translated to the Italian version with cross-cultural adaptation and validation.21 This scale is not very practical in clinical use because it requires time for completion and is not specific for shoulder disorders.39 To reduce the time to complete the form, a new form has been designed shortening disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire, the Quick Dash form,40 more applicable in the clinical daily activity. However, in this study we adopted the longer form because it is more informative than the Quick Dash. In the current study, the VAS was used to record the patients' level of pain. The VAS is considered to be one of the best methods available for the estimation of the intensity of pain.41 The VAS provides a continuous scale for magnitude estimation and consists of a straight line of 100 mm (10 cm) with an anchor at each end defined as the extreme limits of personal pain experience.42 The use of VAS is considered preferable than discrete outcome measures, such as numerical and verbal rating scales, because it represents a continuous range of values. Nevertheless, high correlations have been reported between the VAS, verbal and numerical rating scales.43

The SF-36 consists of 36 questions on the general health status of patients. This questionnaire provides eight separate scale scores (physical functioning, role-physical, bodily pain, general health, vitality, social functioning, role emotional, mental health), which are then aggregated into two main scores: the physical composite score (PCS) and the mental composite score (MCS).44 Very low scores for PCS indicate severe physical disorder, distressing bodily pain, frequent tiredness and an unfavourable evaluation of health status. Very low scores for MCS indicate frequent psychological distress and severe social and role disability due to emotional problems. The SF-36 is commonly used in the literature with valid translations in many languages allowing the use of this scale as a standard tool. A high score represents a better status of health.44

The OSS is a 12-item self-assessment questionnaire for assessing a degenerative or inflammatory state of the shoulder. It is not suitable for patients with instability of the shoulder.45 Each question has five categories of response, corresponding to a score ranging from 1 to 5. Overall score ranges from 12 (best) to 60 (worst). The questions investigate both pain and influence on the quality of life. The OSS is short, practical, reliable, valid and sensitive to clinically important changes.46,47

Sample size calculation

A sample size of 51 subjects was estimated given α = 5% and 1 – β = 0.80 for significant Pearson's r correlation test. Moreover, a dropout rate of 15% was considered (N = 7.65) for a final sample size of 59 patients with non-specific shoulder pain, to be enrolled.

Constructs investigated

The authors analysed internal consistency by performing a principal component analysis followed by a confirmatory factor analysis.

Internal consistency was tested using Cronbach's alpha value of correlations between all the items of the SPADI-I scale and for each of the subscales (pain and disability). For rating internal consistency, an a priori value equal or higher than 0.7 of the Cronbach's alpha coefficient was set as threshold of acceptance, particularly the range of grading were defined as following: 0.70–0.79 acceptable; 0.80–0.89 good; ≥0.90 excellent.48 A low Cronbach's alpha indicates a lack of correlation between the items in a scale, which makes summarizing the items unjustified. A very high Cronbach's alpha (>0.95) indicates high correlations among the items in the scale, i.e. redundancy of one or more items.

Thus, a positive rating for internal consistency when factor analysis was applied occurs when Cronbach's alpha is between 0.70 and 0.95.48

To analyse the pain construct, the authors compared SPADI-I with VAS; to analyse shoulder disability, compared SPADI-I with DASH and OSS, because DASH refers to disability of the arm, shoulder and hand and results may not be specific for the shoulder only. To analyse the effect on the quality of life, the SPADI-I was compared to the SF-36.

Construct validity refers to the extent each item composing an outcome measure correlate to other outcome measures consistently with the domains the respective outcome measures are supposed to assess.49

Construct validity has been tested by Pearson's or Spearman correlation coefficients (depending on data distribution) between the SPADI-I and the other scales administered to the patients (i.e. OSS, VAS, DASH, SF-36). Statistical analysis was performed using the R-Studio software and statistical significance was set at p = 0.05.The following ranges were considered for rating the robustness of construct validity: 0–0.20 poor, 0.21–0.40 discrete, 0.41–0.60 good, 0.61–0.80 very good, 0.81–1.0 excellent.49

Results

The sample was composed of 59 patients (35 male, 24 female), with an overall mean age of 54.34 ± 12.5 years (52.94 ± 14.2 year for males, 56.38 ± 9.5 years for females), whose demographic characteristics are reported in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of demographic characteristics of the sample.

| Characteristics | Cases (%) |

|---|---|

| Maritial status | |

| Yes | 39 (66%) |

| No | 18 (31%) |

| N/A | 2 (3%) |

| Educational level | |

| Primary school | 1 (2%) |

| Secondary school | 8 (14%) |

| High-school | 22 (37%) |

| University | 28 (47%) |

| Work | |

| N/A | 1 (2%) |

| Free lance | 19 (32%) |

| Housewife | 7 (12%) |

| Employee | 14 (24%) |

| None | 3 (5%) |

| Retired | 14 (24%) |

| Student | 1 (2%) |

| Physical activities | |

| None | 20 (34%) |

| <3 h/week | 19 (32%) |

| >3 h/week | 19 (32%) |

| N/A | 1 (2%) |

| Smoking | |

| N/A | 1 (2%) |

| No | 38 (64%) |

| Yes | 10 (17%) |

| EX | 10 (17%) |

| Pain duration | |

| <3 months | 3 (5%) |

| 3 to 6 months | 30 (51%) |

| >6 months | 25 (42%) |

| N/A | 1 (2%) |

| Pain referred to Ul | |

| Yes | 26 (44%) |

| No | 29 (49%) |

| N/A | 4 (7%) |

| Therapies | |

| Anxiolytic/antidepressants | 1 (2%) |

| Pain killers | 18 (31%) |

| Myorelaxant | 0 (0%) |

| NSAD/cortisone | 13 (22%) |

| Comorbidities | |

| Cardiac | 16 (27%) |

| Respiratory | 3 (5%) |

| Endocrinologic | 5 (8%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 11 (19%) |

| Kidney | 4 (7%) |

| Anxiety/delusion | 2 (3%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) |

N/A: not applicable, UL: upper limb; EX: Ex Smoker.

Clinical and physical characteristics of sampled patients have been reported in Table 2 with descriptive statistics showing distribution properties for each variable. Mean disability observed in our sample resulted similar with the one of patients recruited in the study of Littlewood et al.31

Table 2.

Physical and clinical characteristics of the sample.

| Variable | Mean (SD) | Median |

|---|---|---|

| Weight (kg) | 73.34 (14) | 75 |

| Height (m) | 1.73 (0.09) | 1.72 |

| Number of visits (N) | 2.3 (2.2) | 2 |

| Rest (h) | 2.55 (3.6) | 0 |

| No work (days) | 2 (10) | 0 |

| SPADI totala | 56.42 (27) | 57 (31) |

| SPADI painb | 26.22 (10.7) | 27 (11.9) |

| SPADI disabilityc | 31.47 (18) | 33 (22) |

| VASd | 3.39 (1.6) | 3.34 (1.8) |

| OSSe | 28.59 (8.8) | 29 (0.9) |

| DASHf | 75.47 (26) | 73 (28.17) |

| SF-36g | 97.8 (12.7) | 101 (7.41) |

SPADI: Shoulder Pain Disability Index; VAS: visual analogic scale; OSS: Oxford Shoulder Score; DASH: Disability of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand scale; SF-36: 36-item short form health survey.

Range 0–100 (0 = no disability, 100 = worst disability).

Range 0–50 (0 = no pain; 50 = worst pain).

Range 0–80 (0 = no disability; 80 = worst disability).

Range 0–10 (0 = no pain; 10 = worst pain).

Range 12–60 (12 = no pain; 60 = worst pain).

Range 0–100 (0 = no disability, 100 = worst disability).

Range 0–100 (0=less quality of life, 100=better quality of life).

Psychometric analyses were made with R-studio software following criteria of the Scientific Advisory Committee of Medical Outcomes Trust.50

Internal consistency of the SPADI-I

Internal consistency is a measure of the extent to which items in a questionnaire (sub)scale are correlated (homogeneous), thus measuring the same concept. Good internal consistency occurs when construct is clearly defined by appropriate items and is tested by principal component analysis or exploratory factor analysis, followed by confirmatory factor analysis. Thus, an exploratory factor analysis with principal components extraction on all items to examine the latent dimensions of the scale was performed.51 The optimum number of factors was determined by the number of principal component coefficients greater than 0.4.52 An applied principal component analysis was used to determine whether the items form only one overall scale (dimension) or more than one.53 An assessment of the number of components was made using cumulative variance percentages of the components and by scree-plot.48

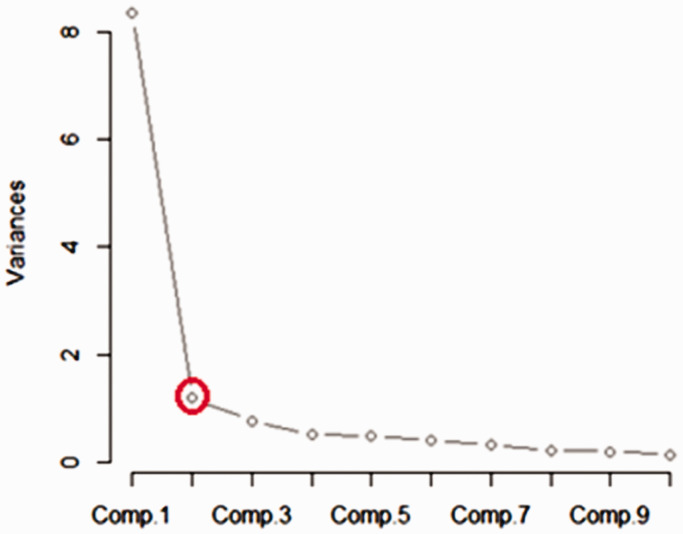

The analysis showed that SPADI-I had two sub scales because just the first two factors obtained 73% of the whole variance, as showed in Table 3 and Figure 1 (scree-plot).

Table 3.

Components calculation.

| Importance of components | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comp. 1 | Comp. 2 | Comp. 3 | Comp. 4 | |

| Standard deviation | 2.887666 | 1.09154532 | 0.88450581 | 0.71903114 |

| Prop. of variance | 0.641432 | 0.09165163 | 0.06018081 | 0.03976968 |

| Cumulative prop. | 0.641432 | 0.73308360 | 0.79326441 | 0.83303409 |

Comp.: component; Prop.: proportion. Numbers in bold highlight numbers of component.

Figure 1.

Scree-plot. Note: Comp. – component. Red circle indicates variance's value.

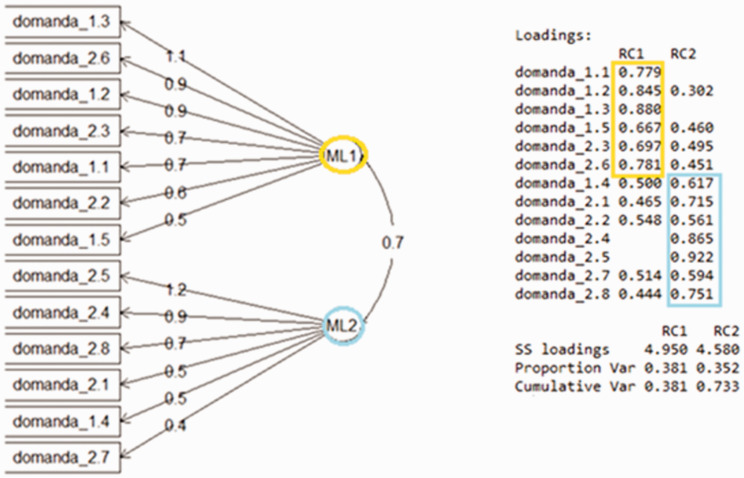

Following the results of the principal component analysis, the results suggest that the SPADI-I should include two domains and this was confirmed by a confirmatory factor analysis.54

This type of analysis determined construct validity and structure validity by maximum likelihood extraction with a matrix of rotation Varimax establishing the satisfaction of the following criteria set a priori: scree-plot inflection and variance >10%.

This confirmatory factor analysis showed an acceptability of the domains with two factors Chi squared test as statistically significant: χ2 = 151.025, p < 0.001 (Table 4) (Figure 2).

Table 4.

Confirmatory factor analysis.

| Factor correlations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | |

| Factor 1 | 1.00 | 0.788 |

| Factor 2 | 0.788 | 1.00 |

| Model Chi squared = 151.0245 | DF = 64 Pr (>Chi squared) = 5.397716e-09 | |

| RMSEA Index = 0.1531147 | ||

| Bentler-Bonnett NFI = 0.79867 | ||

| Bentler CFI = 0.8705251 | ||

Note: Number in bold means significant value.

DF: degrees of freedom; NFI: normed fit index; RSMEA: root square mean error of approximation; CFI: comparative fit index.

Figure 2.

Factors analysis. Note: Factors analysis – SS: sum of square; RC1: rotated component with varimax matrix 1; RC2: rotated component with varimax matrix 2; Var: variance; ML1: maximum likehood1; ML2: maximum likehood2. Yellow and blue colors highlighting the two domains of the scale.

After determining the number of homogeneous subscales, Cronbach's alpha was calculated for each subscale separately. Cronbach's alpha is considered as an adequate measure of internal consistency.

Internal consistency of the Italian version of the scale in our sample was good (α = 0.84) overall, with excellent (α = 0.94) and acceptable (α = 0.76) performance for pain and disability subscales, respectively. Furthermore, standard error of measurement and minimally detectable change were calculated (Table 5).55

Table 5.

Internal consistency of the SPADI scale.

| Cronbach's alpha | SEM | MDC | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pain subscale (5 Items) | 0.94 | 2.62 | 3.70 |

| Disability subscale (8 items) | 0.76 | 8.96 | 12.58 |

| Total scale (13 items) | 0.84 | 10.82 | 15.30 |

MDC: minimally detectable change; SEM: standard error measurement.

Construct validity of the SPADI-I

The correlation coefficients between the SPADI-I and its subscales with the other scales administered to patients are reported in Table 6.

Table 6.

Construct validity of the SPADI scale.

| VAS |

OSS |

DASH |

SF-36 |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| r | p | r | p | r | P | r | p | |

| Pain subscale | 0.54 | <0.001* | 0.74 | <0.001* | 0.67 | <0.001* | −0.27 | 0.04* |

| Disability subscale | 0.49 | 0.0001* | 0.78 | <0.001* | 0.73 | <0.001* | −0.26 | 0.046* |

| Total score | 0.52 | <0.001* | 0.77 | <0.001* | 0.76 | <0.001* | −0.29 | 0.02* |

VAS: visual analogic scale; OSS: oxford shoulder score; DASH: Disability of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand scale; SF-36: 36-item short form health survey; r = Pearson's or Spearman correlation coefficient.

Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05.

There was good correlation between the VAS scale and the SPADI-I total score and subscales. The correlation with SPADI-I was very good for both the OSS and the DASH with regard to total scores and subscales, coherently. Furthermore, the results showed a discrete correlation between SPADI-I and the SF-36 scale, again for both total scores and subscale.

Discussion

Outcome questionnaires measure the patients' perspective with regard to symptoms and function. Most of the questionnaires in the literature are in English and are tailored to the Anglo-Saxon culture.

There are many differences in the social and cultural context of the populations which may prevent a “tout court” translation of the questionnaire.19 Infact, a simple linguistic translation could be misleading and could undermine the strength of the tool.

This misrepresentation implies that a validation process should take into account all of the peculiarities of the cultural social context to which the evaluation scale will be used. Questions should not be replaced as it may eliminate a functional domain, so a methodologically transparent and correct transcultural validation process is necessary.56 The current study was based on current evidence available in which patients were recruited according to stringent criteria, such as structured case history, evidence-based physical examination and bioimaging with the aim to include only non-specific causes of shoulder pain.

The current study was conducted to provide a specific instrument to Italian health professionals that was efficient and easy to use and suitable for most patients that present in outpatient clinics with non-specific shoulder pain.57–59

The original SPADI lists 13 questions for “pain” and “disability”4 but these two dimensions are not supported by all validity studies. The version in the Turkish language mentions three dimensions,14 whereas Tveita et al. report that the SPADI may be one-dimensional reporting that high Cronbach's alpha >0.9 and the analysis of the structure of the factors leads to the conclusion that the SPADI questions only assess “pain”, which is the main cause of functionality problems.9 Thoomes-de Graaf et al. translated the SPADI in Dutch and showed that the scale consists of only one factor,60 probably because pain is the main limitation for the execution of various functional activities, such as those recorded with the SPADI, as also described in other studies.61–63 However, factor analysis in our data revealed that SPADI-I has two factors, with six items (four pain/two disability) weighting the first factor by >0.5, and seven items (six disability/one pain) weighting the second factor.

The authors of the current study suggest that the two-dimensions of the SPADI scale (i.e. “pain”, “disability”) reflects the original version of the questionnaire.4 The confirmatory factor analysis showed an acceptable fit with a comparative fit index of 0.87 and normed fit index of 0.79, but the error was higher (root mean square error of approximation = 0.15) than the recommended value of 0.08.64 The fit indices associated with the confirmatory factor analysis model were satisfactory, although the error of approximation was an exception and did not indicate an optimal fit, which may be due to an effect of the population on the factor structure. It should be bear in mind that a slightly increased error does not necessarily imply that the structure of the scale is poor.65 The good construct validity obtained with this Italian version supports its usefulness for evaluating patients' perception of the impact of non-specific shoulder pain.

In previous studies, the following samples were considered: 136 patients in a Spanish study,65 134 patients in a Greek study,16 120 patients in a Chinese study,66 98 patients in another Italian study targeted patients after shoulder surgery for anterior instability.18 All samples reported were bigger than the current study; however, type 1 and 2 errors were specified for sample size calculation and power analysis. Only in one study, sample was calculated with 4–7 people for each items of the scale,65 but in the majority of other manuscripts there was no justification for sample size recruited.10,16–18,66,67

The correlations showed in the present study can be compared with other SPADI cross-cultural adaptation studies:65–67 in the Chinese cultural adaptation,66 Pearson's “r” for SPADI total and subscales for pain and disability was 0.40, 0.49, 0.31 with VAS and 0.36, 0.31, 0.35 with SF-36, respectively. In the SPADI Spanish version,65 correlation values were tested with DASH (pain: r = 0.80; disability: r = 0.76), VAS (pain: r = 0.67, disability: r = 0.65) and SF-36 (r = 0.40). In the Thai version of the SPADI,67 correlations between SPADI pain subscale, disability subscale and total score and DASH scale were 0.59, 0.83 and 0.79, respectively. Overall, our results are similar to the ones obtained in other adaptation studies, especially for correlation between SPADI and VAS or DASH, but correlation results with SF-36 were different. Authors' perspective is that restrictions in quality of life and impairments of physical and psychological domains following shoulder diseases and pain were variable in the sampled population. However, this aspect highlights the possibility that assessment of the multidimensional aspects of patient's burden can be better targeted if SPADI and SF-36 are both administered in patients with non-specific shoulder pain.

After translation and cultural adaptation of the SPADI questionnaire into Italian, its internal consistency (rated by Cronbach's alpha) was calculated to be 0.84, which is considered a reliable result in other two studies.48,68 Our results are consistent with those obtained by testing the questionnaire in other languages11,16,65,66 demonstrating that the SPADI-I is a valid questionnaire for patients with non-specific shoulder symptoms in assessing pain and functional disability.

Moderate correlation with the SF-36 may be related to the purpose of the SF-36 to assess all of the aspects determining the individual health status and the patient's perception of own quality of life. In this regard, our results are not aligned with other cross-cultural translation studies of the SPADI perhaps because many other things could impact health-related quality of life, so the relationship between SPADI-I and SF-36 was not as strong as in other cross-cultural translation studies of the SPADI.65,66 However, when the SPADI-I was compared with PROM tools, much more oriented to the specific region or otherwise to the upper limb, the correlation indexes improved.

The Italian SPADI is complete, imposes very little burden to the patients, and provide valid and responsive data on the perception of shoulder disability. Questions of the scale are simple and straightforward, which make the questionnaire very well accepted by patients, as the criterion validity was assessed in the original version, and easy to complete.4 Furthermore, patients do not require any further explanation to answer questions and the Italian version of SPADI is suitable for e-mail surveys4; which are powerful tools for clinicians because of its ease and fast administration to patients, even if they are faraway. Furthermore, it is specific for the shoulder complex. Due to its robust construct validity, the SPADI provides information on pain and disability of patients with non-specific shoulder pain. It is important for physiotherapists to collect patient reported information after interventions with the aim of quantifying baseline and to monitor the recovery process.

The main limitations of our study are worth noting: the lack of the re-test phase limiting information about reliability of the scale. Furthermore, the results may lack of generalizability, as this cross-cultural adaptation study was targeted only on subjects with non-specific shoulder pain.

Further researches should confirm the two-factor structure of the SPADI-I and the construct validity should be confirmed also in other sampling with different shoulder diseases (e.g. frozen shoulder, multidirectional instability). Moreover, other psychometric properties should be investigated, such as test re-test reliability, interpretability and responsiveness of the instrument in future studies.

Conclusion

The SPADI-I has good internal consistency and validity and is correlated with other validated outcome measuring the same construct for patients with non-specific shoulder pain. The SPADI was cross-culturally adapted for Italian-speaking participants and can be implanted as a useful tool by clinicians for the assessment of patients with non-specific shoulder pain.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank Professor Rita Bennett, PhD, for the translation of the instrument. The authors are also grateful to Alessandro Chiarotto (PT, PhD) for his precious advices during the advancement of this article (scientific advisor) and to John Heick (PT, PhD) for his precise contributions to the writing of the article (language advisor). The authors also thank Stefano Gumina and Vittorio Candela (MD). They were fundamentals to collect our patient's documentation needed for writing this original article.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Ethical Review and Patient Consent: This study was approved by the Ethical Committee of Lecce (Italy) with protocol n.14 of 15th of January 2018. Personal information and informed consent were obtained from all of the patients to participate in the study.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Guarantor: FB.

ORCID iDs

Fabrizio Brindisino https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8950-8203

Andrea Turolla https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1609-8060

References

- 1.Luime JJ, Koes BW, Hendriksen IJ, et al. Prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain in the general population; a systematic review. Scand J Rheumatol 2004; 33: 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Minns Lowe CJ, Moser J, Barker K. Living with a symptomatic rotator cuff tear ‘bad days, bad nights’: a qualitative study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014; 15: 228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.World Health Organization. ICF – international classification of functioning, disability and health. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2001, pp.10–20.

- 4.Roach KE, Budiman-Mak E, Songsiridej N, et al. Development of a shoulder pain and disability index. Arthritis Care Res 1991; 4: 143–149. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Breckenridge JD, McAuley JH. Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI). J Physiother 2011; 57: 197. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Williams JW, Jr, Holleman DR, Jr, Simel DL. Measuring shoulder function with the shoulder pain and disability index. J Rheumatol 1995; 22: 727–732. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Beaton DE, Richards RR. Measuring function of the shoulder. A cross-sectional comparison of five questionnaires. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1996; 78: 882–890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ekeberg OM, Bautz-Holter E, Tveita EK, et al. Agreement, reliability and validity in 3 shoulder questionnaires in patients with rotator cuff disease. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2008; 9: 68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tveita EK, Ekeberg OM, Juel NG, et al. Responsiveness of the shoulder pain and disability index in patients with adhesive capsulitis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2008; 9: 161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Angst Goldhahn J, Pap G, Mannion AF, et al. Cross-cultural adaptation, reliability and validity of the German Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI). Rheumatology 2007; 46: 87–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Martins J, Napoles BV, Hoffman CB, et al. The Brazilian version of shoulder pain and disability index – translation, cultural adaptation and reliability. Rev Bras Fisioter 2010; 14: 527–536. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Guermazi M, Allouch C, Yahia M, et al. Arabic translation and validation of the SPADI index. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2011; 54: 228–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeldi AJ, Aseer AL, Dhandapani AG, et al. Cross-cultural adaption, reliability and validity of an Indian (Tamil) version for the shoulder pain and disability index. Hong Kong Physiother J 2012; 30: 99–104. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bumin G, Tuzon E, Tonga E. The shoulder pain and disability index (SPADI): cross-cultural adaptation, reliability, and validity of the Turkish version. J Back Musculoskeletal Rehabil 2008; 21: 57–62. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jamnik H, Spevak MK. Shoulder pain and disability index: validation of Slovene version. Int J Rehabil Res 2008; 31: 337–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vrouva S, Batistaki C, Koutsioumpa E, et al. The Greek version of Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI): translation, cultural adaptation, and validation in patients with rotator cuff tear. J OrthopTraumatol 2016; 17: 315–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Marchese C, Cristalli G, Pichi B, et al. Italian cross-cultural adaptation and validation of three different scales for the evaluation of shoulder pain and dysfunction after neck dissection: University of California – Los Angeles (UCLA) Shoulder Scale, Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) and Simple Shoulder Test (SST). Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2012; 32: 12–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vascellari A, Venturin D, Ramponi C, et al. Psychometric properties of three different scales for subjective evaluation of shoulder pain and dysfunction in Italian patients after shoulder surgery for anterior instability. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2018; 27: 1497–1504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use, 2nd ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ristori D, Miele S, Rossettini G, et al. Towards an integrated clinical frame work for patient with shoulder pain. Arch Physiother 2018; 8: 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Padua R, Padua L, Ceccarelli E, et al. Italian version of the Disability of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand (DASH) questionnaire. Cross-cultural adaptation and validation. J Hand Surg Br 2003; 28: 179–186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Beaton DE, Bombardier C, Guillemin F, et al. Guidelines for the process of cross-cultural adaptation of self-report measures. Spine 2000; 25: 3186–3191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.May S, Chance-Larsen K, Littlewood C, et al. Reliability of physical examination tests used in the assessment of patients with shoulder problems: a systematic review. Physiotherapy 2010; 96: 179–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lenza M, Buchbinder R, Takwoingi Y, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging, magnetic resonance arthrography and ultrasonography for assessing rotator cuff tears in people with shoulder pain for whom surgery is being considered. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2013; 24: CD009020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frost P, Andersen JH, Lundorf E. Is supraspinatus pathology as defined by magnetic resonance imaging associated with clinical sign of shoulder impingement?. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1999; 8: 565–568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Goodman C, Snyder T. Differential diagnosis for physical therapists, screening for referral. 5th ed. USA: Elsevier, 2012.

- 27.Lewis J. Rotator cuff related shoulder pain: assessment, management and uncertainties. Man Ther 2016; 23: 57–68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Warby SA, Pizzari T, Ford JJ, et al. The effect of exercise-based management for multidirectional instability of the glenohumeral joint: a systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014; 23: 128–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Pillastrini P, Gardenghi I, Bonetti F, et al. An updated overview of clinical guidelines for chronic low back pain management in primary care. Joint Bone Spine 2012; 79: 176–185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Littlewood C. Contractile dysfunction of the shoulder (rotator cuff tendinopathy): an overview. J Man Manip Ther 2012; 20: 209–213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Littlewood C, Bateman M, Brown K, et al. A self-managed single exercise programme versus usual physiotherapy treatment for rotator cuff tendinopathy: a randomised controlled trial (the SELF study). Clin Rehabil 2016; 30: 686–696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hanchard NC, Goodchild L, Thompson J, et al. Evidence-based clinical guidelines for the diagnosis, assessment and physiotherapy management of contracted (frozen) shoulder. Physiotherapy 2012; 98: 117–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Milgrom C, Milgrom Y, Radeva-Petrova D, et al. The supine apprehension test helps predict the risk of recurrent instability after a first-time anterior shoulder dislocation. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014; 23: 1838–1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McKenzie R, May S. The human extremities: mechanical diagnosis & therapy, Waikanee: Spinal Publications, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 35.May S, Ross J. The McKenzie classification system in the extremities: a reliability study using Mckenzie assessment forms and experienced clinicians. J Manipulative Physiol Ther 2009; 32: 556–563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wainner RS, Fritz JM, Irrgang JJ, et al. Reliability and diagnostic accuracy of the clinical examination and patient self-report measures for cervical radiculopathy. Spine 2003; 28: 52–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Themistocleous GS, Goudelis G, Kyrou I, et al. Translation into Greek, cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand Questionnaire (DASH). J Hand Ther 2006; 19: 350–357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gummesson C, Atroshi I, Ekdahl C. The disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand (DASH) outcome questionnaire: longitudinal construct validity and measuring self-rated health change after surgery. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2003; 4: 11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Angst F, Schwyzer HK, Aeschlimann A, et al. Measures of adult shoulder function: Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder, and Hand Questionnaire (DASH) and its short version (QuickDASH), Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI), American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) Society standardized shoulder assessment form, Constant (Murley) Score (CS), Simple Shoulder Test (SST), Oxford Shoulder Score (OSS), Shoulder Disability Questionnaire (SDQ), and Western Ontario Shoulder Instability Index (WOSI). Arthritis Care Res 2011; 11: S174–S188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gummesson C, Ward MM, Atroshi I. The shortened disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire (QuickDASH): validity and reliability based on responses within the full-length DASH. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2006; 7: 44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Scott J, Huskisson EC. Graphic representation of pain. Pain 1976; 2: 175–184. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Langley G, Sheppeard H. The visual analogue scale: its use in pain measurement. Rheumatol Int 1985; 5: 145–148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Carlsson AM. Assessment of chronic pain. I Aspects of the reliability and validity of the visual analogue scale. Pain 1983; 16: 87–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Apolone G, Mosconi P. The Italian SF-36 health survey: translation, validation and norming. J. Clin Epidemiol 1998; 51: 1025–1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murena L, Vulcano E, D'Angelo F, et al. Italian cross-cultural adaptation and validation of the Oxford Shoulder Score. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010; 19: 335–341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Dawson J, Fitzpatrick R, Carr A. Questionnaire on the perceptions of patients about shoulder surgery. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996; 78: 593–600. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Huber W, Hofstaetter JG, Hanslik-Schnabel B, et al. The German version of the Oxford Shoulder Score – cross-cultural adaptation and validation. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2004; 124: 531–536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol 2007; 60: 34–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Streiner DL, Norman GR. Health measurement scales. A practical guide to their development and use, New York: Oxford University Press, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Scientific Advisory Committee of the Medical Outcomes Trust. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res 2002; 11: 193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pickering PM, Osmotherly PG, Attia JR, et al. An examination of outcome measures for pain and dysfunction in the cervical spine: a factor analysis. Spine 2008; 36: 581–588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Norman G and Streiner D. Biostatistics, the bare essentials. St. Louis, MO: Mosby Inc., 1994.

- 53.Floyd FJ, Widaman KF. Factor analysis in the development and refinement of clinical assessment instruments. Psychol Assess 1995; 7: 286. [Google Scholar]

- 54.de Vet HCW, Ader HJ, Terwee CB, et al. Are factor analytical techniques appropriately used in the validation of health status questionnaires? A systematic review on the quality of factor analyses of the SF-36. Qual Life Res 2005; 14: 1203–1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.de Vet HC, Terwee CB, Ostelo RW, et al. Minimal changes in health status questionnaires: distinction between minimally detectable change and minimally important change. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2006; 4: 54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Zanoli G, Stronqvist B, Padua R, et al. Lesson learned searching for HRQoL instruments to assess the results of treatment in person with lumbar disorder. Spine 2000; 25: 3178–3185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Luime JJ, Koes BW, Hendriksen IJ, et al. Prevalence and incidence of shoulder pain in the general population; a systematic review. Scand J Rheumatol 2004; 33: 73–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Schellingerhout JM, Verhagen AP, Thomas S, et al. Lack of uniformity in diagnostic labeling of shoulder pain: time for a different approach. Man Ther 2008; 13: 478–483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Buchbinder R, Goel V, Bombardier C, et al. Classification systems of soft tissue disorders of the neck and upper limb: do they satisfy methodological guidelines?. J Clin Epidemiol 1996; 49: 141–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Thoomes-de Graaf M, Scholten-Peeters GGM, Duijn E, et al. The Dutch Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI): a reliability and validation study. Qual Life Res 2015; 24: 1515–1519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Orfale AG, Araújo PMP, Ferraz MB, et al. Translation into Brazilian Portuguese, cultural adaptation and evaluation of the reliability of the disabilities of the arm, shoulder and hand questionnaire. Braz J Med Biol Res 2005; 38: 293–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roddey TS, Cook KF, O'Malley KJ, et al. The relationship among strength and mobility measures and self-report outcome scores in persons after rotator cuff repair surgery: impairment measures are not enough. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2005; 14: 95S–98S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Engebretsen K, Grotle M, Bautz-Holter E, et al. Determinants of the shoulder pain and disability index patients with subacromial shoulder pain. J Rehabil Med 2010; 42: 499–505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Model 1999; 6: 1–55. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Membrilla-Mesa MD, Cuesta-Vargas AI, Pozuelo-Calvo R, et al. Shoulder pain and disability index: cross cultural validation and evaluation of psychometric properties of the Spanish version. Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015; 13: 200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yao M, Yang L, Cao ZY, et al. Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) into Chinese. Clin Rheumatol 2017; 36: 1419–1426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Phongamwong C, Choosakde A. Reliability and validity of the Thai version of the Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (Thai SPADI). Health Qual Life Outcomes 2015; 13: 136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yfantopoulos J. Measuring quality of life and the European health model. Arch Hell Med 2007; 24: 6–18. [Google Scholar]