We appreciate the interest of Stengel et al 1 in our recent multicenter study published in Gut.1 2 The group suggests that peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) are a source of interleukin (IL)-1β in acute decompensation (AD) independent of the canonical inflammasome activation pathway.1

While we acknowledge this meticulous work performed, we still think that the source of IL-1 and, therefore, the site of inflammasome activation is rather the diseased liver than circulating PBMC. Especially since in our work, we found these pathways persistently increased even in compensated, recompensated and decompensated cirrhosis.

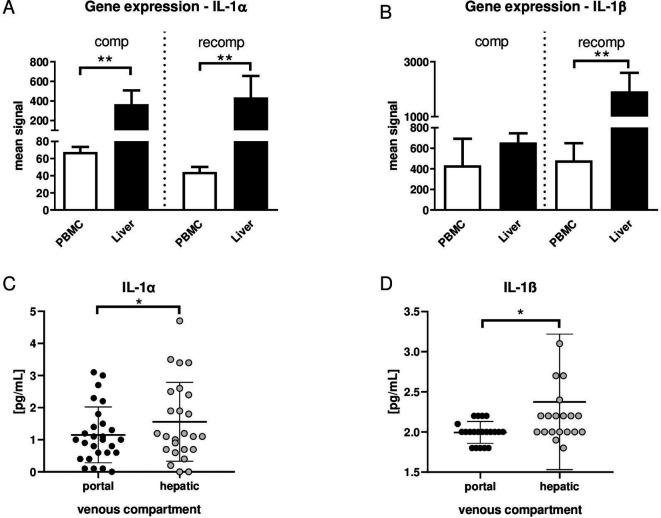

In order to prove the origin of IL-1α and IL-1β, we assessed gene expression in PBMC and liver from our animal model of compensated and recompensated (after recovery from AD) cirrhosis. In this model, bile duct ligation in rats was used to induce liver cirrhosis and lipopolysaccharide to induce AD as described previously.2 Gene expression of both IL-1α and IL-1β is significantly higher in liver tissue compared with PBMC in recompensated cirrhosis. In compensated cirrhosis, gene expression of IL-1α, but not IL-1β, is significantly increased in liver tissue compared with PBMC (figure 1A, B).

Figure 1.

(A) Gene expression of interleukin (IL)-1α and (B) IL-1β in liver tissue and peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) in compensation (comp; left) and recompensation (recomp; right) model, as described in Monteiro et al.2 n=5 in all groups. **p<0.01 PBMC versus liver. (C) Serum concentrations of IL-1α and (D) IL-1β in portal venous compartment (black dots) and in hepatic venous compartment (gray dots) from patients with cirrhosis. n=27. *p<0.05 portal vein versus hepatic vein.

Translating those results into the clinical setting, portal venous and hepatic venous blood samples from patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis were collected. Levels of IL-1α and IL-1β were significantly higher in hepatic veins compared with portal veins (figure 1C, D), suggesting a net production of IL-1 in the liver. That this may be inflammasome dependent is also suggested by our previous publication, showing that several inflammasome-dependent ILs, such as IL-18, also are elevated in the hepatic outflow compared with the portal vein in patients who develop organ failures.3 4

Moreover, the relevant pathway of inflammasome activation in human whole blood and liver tissue was assessed by correlation analyses of gene expression of IL-1α and IL-1β with NACHT, LRR and PYD domains-containing protein 3 (NLRP3) and Caspase-1 (CASP1) (as markers of canonical inflammasome activation) as well as CASP4 and CASP5 (as markers of non-canonical inflammasome activation).5 Gene expression of IL-1α showed significant correlation with NLRP3, CASP1, CASP4 and CASP5 in liver tissue but not in whole blood (online supplemental figure 1A, B). However, gene expression of IL-1β is strongly correlated with the expression of NLRP3, CASP1, CASP4 and CASP5 in liver tissue, as well as in whole blood (online supplemental figure C, D).

gutjnl-2020-322621supp001.pdf (300.7KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-322621supp002.pdf (35.1KB, pdf)

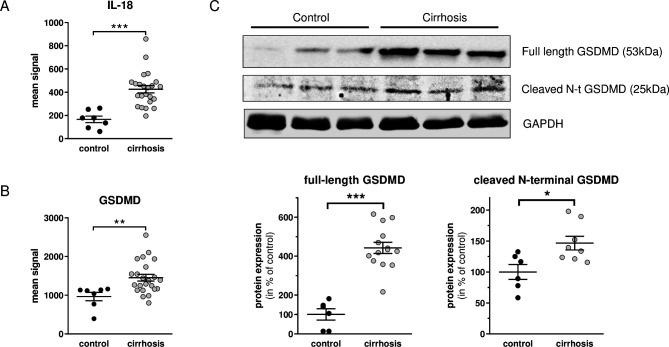

Gene expression of key downstream effectors of inflammasome activation, IL-18 and gasdermin-D (GSDMD), was assessed in liver tissue from cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic control patients. The analysis showed significantly higher expression of both downstream effectors (IL-18 and GSDMD) of inflammasome activation in the cirrhotic liver tissue (figure 2A, B). After cleavage of GSDMD, the N-terminal cleavage product is biologically active. We, therefore, assessed GSDMD and its cleaved N-terminal GSDMD on the protein level via western blot (online supplemental material 1). Importantly, full-length GSDMD and cleaved N-terminal GSDMD are both significantly higher expressed in cirrhotic livers (figure 2C).

Figure 2.

(A) Gene expression of interleukin (IL)-18 and (B) Gasdermin-D (GSDMD) in liver tissue from cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic control patients. (C) Protein levels of GSDMD and cleaved N-terminal GSDMD by Western Blot in liver tissue from cirrhotic and non-cirrhotic control patients. Controls (black dots), cirrhosis (gray dots). *p<0.05, **p<0.01, ***p<0.001 cirrhosis versus control.

Our results indicate that (1) the liver is a significant contributing source of circulating IL-1α and IL-1β, (2) the expression of IL-1α in the liver, but not in peripheral blood, is associated with canonical and non-canonical inflammasome activation and its downstream effectors and (3) the expression of IL-1β is highly associated with canonical and non-canonical inflammasome activation in both liver and whole blood. The study of Stengel et al 1 and our current data suggest multiple cellular sources in different stages of cirrhosis, mainly hepatic tissue and PBMC. In conclusion, there is evidence for canonical, non-canonical and alternative inflammasome activation in the liver involved in the release of IL-1α and IL-1β.

Footnotes

Twitter: @R_Schierwagen, @UschnerFrank

Contributors: MP and RS: acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, statistical analysis. SM, CO, FEU, CJ and JC: acquisition of data and analysis of data. JT: study concept and design, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of data, drafting of the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript regarding important intellectual content, funding recipient, administrative, technical and material support, and study supervision.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Supplemental material: This content has been supplied by the author(s). It has not been vetted by BMJ Publishing Group Limited (BMJ) and may not have been peer-reviewed. Any opinions or recommendations discussed are solely those of the author(s) and are not endorsed by BMJ. BMJ disclaims all liability and responsibility arising from any reliance placed on the content. Where the content includes any translated material, BMJ does not warrant the accuracy and reliability of the translations (including but not limited to local regulations, clinical guidelines, terminology, drug names and drug dosages), and is not responsible for any error and/or omissions arising from translation and adaptation or otherwise.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not required.

References

- 1.Stengel S, Steube A, Köse-Vogel N, et al. Primed circulating monocytes are a source of IL-1β in patients with cirrhosis and ascites. Gut 2021;70:622–3. 10.1136/gutjnl-2020-321597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Monteiro S, Grandt J, Uschner FE, et al. Differential inflammasome activation predisposes to acute-on-chronic liver failure in human and experimental cirrhosis with and without previous decompensation. Gut 2021;70:379–87. 10.1136/gutjnl-2019-320170 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jansen C, Möller P, Meyer C, et al. Increase in liver stiffness after transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt is associated with inflammation and predicts mortality. Hepatology 2018;67:1472–84. 10.1002/hep.29612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Praktiknjo M, Monteiro S, Grandt J, et al. Cardiodynamic state is associated with systemic inflammation and fatal acute-on-chronic liver failure. Liver Int 2020;40:1457–66. 10.1111/liv.14433 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tang Z, Li C, Kang B, et al. GEPIA: a web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res 2017;45:W98–102. 10.1093/nar/gkx247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

gutjnl-2020-322621supp001.pdf (300.7KB, pdf)

gutjnl-2020-322621supp002.pdf (35.1KB, pdf)