Abstract

Background

Among Aboriginal children, the burden of acute respiratory tract infections (ALRIs) with consequent bronchiectasis post-hospitalisation is high. Clinical practice guidelines recommend medical follow-up one-month following discharge, which provides an opportunity to screen and manage persistent symptoms and may prevent bronchiectasis. Medical follow-up is not routinely undertaken in most centres. We aimed to identify barriers and facilitators and map steps required for medical follow-up of Aboriginal children hospitalised with ALRIs.

Methods

Our qualitative study used a knowledge translation and participatory action research approach, with semi-structured interviews and focus groups, followed by reflexive thematic grouping and process mapping.

Findings

Eighteen parents of Aboriginal children hospitalised with ALRI and 144 Australian paediatric hospital staff participated. Barriers for parents were lack of information about their child's condition and need for medical follow-up. Facilitators for parents included doctors providing disease specific health information and follow-up instructions. Staff barriers included being unaware of the need for follow-up, skills in culturally responsive care and electronic discharge system limitations. Facilitators included training for clinicians in arranging follow-up and culturally secure engagement, with culturally responsive tools and improved discharge processes. Twelve-steps were identified to ensure medical follow-up.

Interpretation

We identified barriers and enablers for arranging effective medical follow-up for Aboriginal children hospitalised with ALRIs, summarised into four-themes, and mapped the steps required. Arranging effective follow-up is a complex process involving parents, hospital staff, hospital systems and primary healthcare services. A comprehensive knowledge translation approach may improve the follow-up process.

Funding

State and national grants and fellowships.

Abbreviations

- ALRI

Acute lower respiratory tract infections

- WA

Western Australia

- ATSI

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

- GP

General Practice doctor

- AHP

Aboriginal Health Practitioner

- SMS

Short Message Service

- ALO

Aboriginal Liaison Officer

RESEARCH IN CONTEXT.

Evidence before this study

There are large differences in health outcomes and life expectancy between Aboriginal and non-Non-Aboriginal Australians, as recently highlighted by a Lancet editorial that expressed ‘a feeling of déjà vu’, finding the ‘2018 Closing the Gap report on health of Aboriginal people in Australia’ ‘utterly disappointing’. Contributors to this gap include respiratory diseases such as bronchiectasis; the life expectancy for Aboriginal people with bronchiectasis is 20 years less than for non-Aboriginal people. Aboriginal children experience disproportionately higher rates of both acute and chronic respiratory disease and higher rates of hospitalisation for respiratory disease. Aboriginal children who are admitted with acute respiratory infections are particularly vulnerable to developing chronic respiratory disease, namely, bronchiectasis. However effective follow-up and treatment of persistent symptoms may prevent bronchiectasis. While national guidelines recommend medical follow-up 3-4 weeks post discharge from hospital, there are currently no widespread strategies to follow up Aboriginal children in Australia.

We conducted a PubMed and OVID search for studies published between 12 March January 2001 and 12 March 2021 with search terms (Indigenous OR Aboriginal OR First Nations) AND (child OR children OR paediatric OR pediatric) AND (lower respiratory tract infection OR pneumonia OR bronchiolitis OR chest infection) AND (hospitalisation OR follow-up OR post-hospitalisation OR medical follow-up) AND (persistent symptoms OR bronchiectasis). We searched articles published in all languages.

Added value of this study

We demonstrated that arranging effective post-hospitalisation follow-up for Aboriginal children is a complex process involving parents, hospital staff, hospital systems and primary healthcare services. We identified key barriers and facilitators for parents and staff for effective follow-up, which included the need for culturally responsive care, provision of health information in a culturally secure way and health systems changes. Twelve key steps were identified as being necessary in the process from admission to discharge and then medical follow-up.

Implications of all the available evidence

Comprehensive knowledge translation initiatives, which addresses the identified barriers and facilitators, may improve the follow-up process by empowering families to seek medical follow-up and equip hospital staff with skills and environment to provide culturally responsive care to Aboriginal children. Careful implementation and evaluation of the strategies will provide insight into potential solutions to the current gap in respiratory health outcomes for this group of children and potentially narrow the elusive health gap between First nations and non-First Nations people in Western countries.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. INTRODUCTION

Aboriginal children have higher rates of hospitalisation for acute lower respiratory tract infections (ALRI) and experience more severe disease [1] than non-Aboriginal children in Australia regardless of where they live. [2] In Western Australia (WA), the burden is particularly high, with admission rates for ALRI's and pneumonia 7•5 and ~14 times higher respectively, in Aboriginal children compared to non-Aboriginal children. [3]

Aboriginal children are at high risk of developing chronic lung disease post-hospitalisation. Two studies found that 15-19% of First Nations children hospitalised with ALRI have bronchiectasis within 18-months of discharge from hospital. [[4],[5]] Specifically, those with a persistent wet cough at 3-4 weeks post-discharge post-bronchiolitis have significantly higher risk of a future diagnosis of bronchiectasis. [5]

Australian national guidelines for Aboriginal children recommend primary care follow-up at four-weeks post-hospitalisation to screen for and manage persistent wet cough, if present. [[6],[7]] The recommended management of children with a chronic wet cough (>4 weeks) in the absence of pointers to alternative causes, is to prescribe appropriate antibiotics i.e., treatment of protracted bacterial bronchitis, so as to ameliorate development of bronchiectasis. [6]

There are currently no state-level hospital policies for routine follow-up of Aboriginal children hospitalised with chest infections. Therefore, there is a need to develop and implement strategies for effective post-hospitalisation follow-up for this at-risk group. For long-term success, strategies implemented should be developed with a comprehensive and integrated approach, based on identified barriers and facilitators, which draw on local knowledge of both Aboriginal families and hospital staff. [8] Hence, our aims were to (i)identify the barriers and facilitators and (ii)map the steps required for following-up Aboriginal children hospitalised with ALRIs.

2. METHODS

We used a knowledge translation and Aboriginal driven [9] participatory action research design. [10] The participatory action research approach was selected to ensure Aboriginal perspectives informed and transformed existing biomedical paradigms. [10] The project represents the first phase of a larger knowledge translation study, which applied the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) [11] to investigate the effectiveness of implementing strategies, based on the identified barriers and facilitators identified in this paper.

As part of the CFIR process, widespread external stakeholder consultations were undertaken prior to data collection. External consultations included the Aboriginal Medical Services (Kimberley and Pilbara regions, i.e., two northern most regions of WA where approximately 40% of the population are Aboriginal), Aboriginal Health Council WA, a non-government, not for profit organisation supporting state-wide Aboriginal controlled primary health services, a rural primary care health support organisation, and the WA Country Health Service which provides primary and secondary level care to regional WA.

2.1. Framework for interview questions and coding

The process for developing interview questions was based on our previous work, [12] where both parents and primary care clinicians highlighted the need for improved follow-up mechanisms for children hospitalized with ALRI and following external stakeholder input. Semi-structured questions were refined between two qualitative researchers. Following analysis of all interview data, identified themes were allocated to the questions. i.e., 1. Knowledge, 2. Skills, 3. Hospital environment and resources and 4. Beliefs and attitudes. (Table 1 and Table 2). The themes were selected by the researchers, based on the best-fit, to capture succinctly and efficiently the key issues surrounding patient care and follow-up.

Table 1.

Interview question guide to conduct parent interviewers

| Question | Theme |

|---|---|

| 1. Did the doctor or other staff talk to you about your child's condition and the need to follow-up in a month? | 1. Knowledge |

| 2. What did the doctor/nurses tell you when you were in the hospital? | |

| 3. Did the doctor or other staff explain to you about lung health? | |

| 4. What did you know about lung health in children? | |

| 5. Did the doctor explain medial information in a way you understood? What would help improve understanding? | 2. Skills (of hospital staff) |

| 6. What is it like coming to the hospital when your child is sick? (Do you feel safe or scared?) | 3. Hospital environment and processes |

| 7. Did you feel okay about talking with the doctors/nurses? How can we help improve things for families? | |

| 8. What can the hospital staff or system do to help you see a doctor in 1-month? | |

| 9. What things might make it hard to follow-up with your doctor or AMS when you leave the hospital? | |

| 10. Did you feel your Aboriginality or your child's Aboriginality affected anything while you were at the hospital? | 4. Beliefs and attitudes |

| 11. Did you feel comfortable to ask your doctor questions? | |

| 12. Did you feel listened to or understood by doctor/nurse? |

Table 2.

Interview question guide to conduct with hospital staff

| Question | Theme |

|---|---|

| 1. What do you need to know/do to provide health information to families and arrange follow-up for Aboriginal children admitted with ALRI? | Knowledge |

| 2. What would prevent you providing health information to Aboriginal parents and arranging follow up? | |

| 3. Do you feel confident in providing health information to Aboriginal families and arranging follow-up for Aboriginal children admitted with ALRI? What skills do you need? | Skills |

| 4. What do you think are the barriers to providing health information and arranging follow-up for Aboriginal children hospitalised with ALRI? (i.e., lack of awareness, skills, knowledge, lack of training) | |

| 5. Are there factors within the hospital setting that could be a barrier or facilitator for Aboriginal families to take on board medical information and attend follow-up? | Hospital environment and processes |

| 6. What processes or policies would assist or prevent with arranging follow-up? | |

| 7. Who is best placed to provide health information to families and arrange follow-up? | Beliefs and attitudes |

2.2. Focus groups with staff

Staff were presented with an outline and rationale of the process required to facilitate follow-up for Aboriginal children with ALRIs, by a senior member of the research team who was also a consultant respiratory physician at the hospital and known to the participants. Staff were then given “a brief”, i.e.,

-

•Aboriginal children hospitalized with ALRIs are at risk of developing chronic lung disease and there is currently no routine follow-up arranged. The solution: Hospital staff will facilitate primary care follow-up at 1-month. To facilitate follow-up at one-month:

-

○Clinicians need to give parents/carers lung health information in a culturally secure way, including the need for follow-up.

-

○Follow-up needs to be arranged through discharge instructions being sent to primary healthcare clinic/clinician

-

○

Barriers and facilitators were then identified and discussed regarding the required procedures. Staff were asked two key questions:

-

1.

What are the barriers to you/your team arranging follow-up?

-

2.

How can follow-up be facilitated by your team?

2.3. Interviewers for interviews and focus groups

The interview team consisted of five researchers in total: a female physiotherapist (PL) with expertise in Aboriginal qualitative research, a male Aboriginal Health practitioner (JW), a male respiratory physician (AS), a female qualitative researcher with expertise in Aboriginal research (RW) and a registered nurse and knowledge translation research expert (FG). Interviews and focus groups were conducted by at least two members of the research team with either audio recordings or written notes (as preferred by participants). Issues related to confidentiality, interview bias, role designation, power imbalance and assumptions influencing participants were discussed and resolved within the research team.

2.3.1. Interviews with parents

Semi-structured individual interviews were conducted with parents/carers of Aboriginal (henceforth respectfully termed parents) of children hospitalised with ALRI. JW was available for all parent interviews to ensure the cultural integrity for parent interviews. The interview process for parents first included an informal yarn, (Aboriginal term for informal conversation to first establish context, content, and trust about both the family and the researchers). The parents were then provided with lung health information, using a flip chart, with an explanation of the child's ALRI and the link to development of chronic lung disease following ALRI. [13] Table 1 outlines the framework for the semi-structured questions.

2.3.2. Staff interviews and focus groups

Knowledge of provision of culturally secure health information and the importance of clinicians arranging medical follow-up one-month post discharge were investigated. Staff were first provided with the rationale for arranging follow-up for Aboriginal children hospitalised with ALRI. Following this, semi-structured questions were asked. (Table 2). All staff approached for interview or focus group agreed to participate. One participant subsequently withdrew consent, due to concerns at their identifiability due to being Aboriginal.

The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research reporting guidelines were followed. [14] Ethical approval was granted from the WA Aboriginal Health Ethics Committee (HREC 920) and the Child and Adolescent Child Health Service Ethics Committee (RGS 3220). All participants provided written, informed consent.

The study was conducted between October 2019 and December 2020 in the only paediatric hospital in WA. The hospital has 298 beds and provides paediatric care to children aged 0-16 years. WA is large, (2•6 million square kilometres) with most of the state classified as very remote. Four percent of the State's population are Aboriginal, a third of whom are aged <15 years. More than 60% of the Aboriginal population live outside metropolitan Perth in regional or remote settings. [15]

External stakeholders were consulted prior to hospital data collection to provide insight into regional service delivery, primary care follow-up mechanisms and logistics, and to better understand the needs and processes of state-level primary health care.

2.3.3. Selection criteria and recruitment

Parents of Aboriginal children hospitalised with ALRI were recruited during their child's hospitalisation. Parents were invited to participate in an interview during their child's hospitalisation. The invitation for the interview was suggested by the researcher. Pragmatically the interview occurred either at the time of recruitment or later during the child's hospitalisation, depending on the priorities of the parent/child and the hospital staff caring for the child. Hospital staff involved in caring for Aboriginal children with ALRIs were recruited via departmental meetings or by verbal or email invitation.

Purposive sampling was used with both criterion and snowball sampling [16] techniques to ensure a representative sample of parents was recruited. Similarly, the same technique was used for recruitment of clinicians and administrative staff, to represent all staff integral to influencing effective follow-up.

Sample size estimation is detailed in the supplement. Recruitment for both groups (parents and hospital staff) continued until information saturation was achieved for each group i.e., no new information or themes were evident. [17]

2.3.4. Data collection and analysis

Data from recorded interviews were transcribed verbatim. Hand-written notes were transcribed and crosschecked between at least two researchers (PL, JW, AS, RW or FG). Inconsistencies were discussed until consensus was reached or clarified with the interviewee when necessary. Reflexive thematic analysis, using deductive and inductive analysis [18] was undertaken to map themes by identifying codes and then sub-themes and agreed by the researchers using an iterative process. Key steps required to ensure medical follow-up were mapped, based on the identified barriers and facilitators, according to knowledge mapping processes. [19]

2.3.5. Analysis of data

Thematic analysis was undertaken in a step-wise process, which was consistent to the process outlined by Creswell et.al. [20] Figure 1 describes the systematic process and attributes researcher contributions.

Figure 1.

Steps of thematic analysis

Trustworthiness is outlined in the supplement

2.4. Knowledge mapping

Knowledge mapping [20] was undertaken using a process with four process steps based on Vail. [[19],[21]] The processes are outlined in Figure 2. The mapping process forms part of the CFIR framework to ensure all stakeholders are engaged and their needs are considered in the planning and organizing of the implementation process, complexities within the health system are accounted for to maximise both knowledge translation and its sustainability. [11] The knowledge map creation included identification of (i) all key people, i.e., child, parents, hospital clinicians, clerks, primary care doctors, (ii) key knowledge (iii) key resources (iv) process flow from beginning to end to ensure all essential elements were identified, and (v) identification and minimization of knowledge gaps. The mapping process was undertaken to promote knowledge translation within the health system for the implementation and evaluation phase of the larger project, using the CFIR framework.

Figure 2.

Knowledge mapping process

Role of the funding source: This project was supported by the Western Australian Health Translation Network and the Australian Governments Medical Research Future Fund (MRFF) as part of the Rapid Applied Research Translation Programme. The grant covered all direct research costs associated with the project including patient recruitment, data collection, production of health literacy tools and data analysis. PL's role in this project was funded by a grant from the Perth Children's Hospital Foundation. No payment or funding was made to write the manuscript by a pharmaceutical company or other agency.

3. RESULTS

External stakeholder findings are summarised in Table 3.

Table 3.

Summary of consultations with external stakeholders

| Theme | Subtheme | Specifics |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Knowledge | 1•1 Primary care clinicians identified need to know how to manage children and recognise chronic wet cough |

|

| 1•2 Hospital staff need to ask parents about Aboriginal status |

|

|

| 1•3 Hospital staff to ask parents for local clinic details |

|

|

| 3. Skills | 3•1 Liaison between hospitals and primary care is needed following discharge of children with ALRI |

|

| 3•2 Expert input locally |

|

|

| 3. Environmental context and resources | 2•1 Discharge summaries |

|

| 2•3 Schedule appointment |

|

3.1. Demographics

Eighteen parents (16-female) aged 18-59 years, of children hospitalised with ALRI, were represented from the state's six major health regions, i.e., metropolitan Perth, South-west, Goldfields, Mid-west, Pilbara and Kimberley. Within the regions, families from both towns and remote Aboriginal communities were interviewed. Table-4 outlines demographics for parents. Figure 3 represents the flow of parents recruited for interview.

Figure 3.

Codes, subthemes and themes for parents to attend and hospital staff to arrange medical follow-up 1-month post discharge for ALRI in children

The 144-hospital staff interviewed (11-focus-group discussions [138-participants] and six-individual interviews) included doctors (paediatricians, respiratory physicians, Aboriginal services coordinator Aboriginal health practitioner, primary-care liaison), nurses, physiotherapists, and clerks. Clinicians and clerks from the hospital varied in experience (new trainees to specialist clinicians with >30 years expertise) and ethnic backgrounds (Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal). Interview duration 10-30 minutes.

3.2. Findings

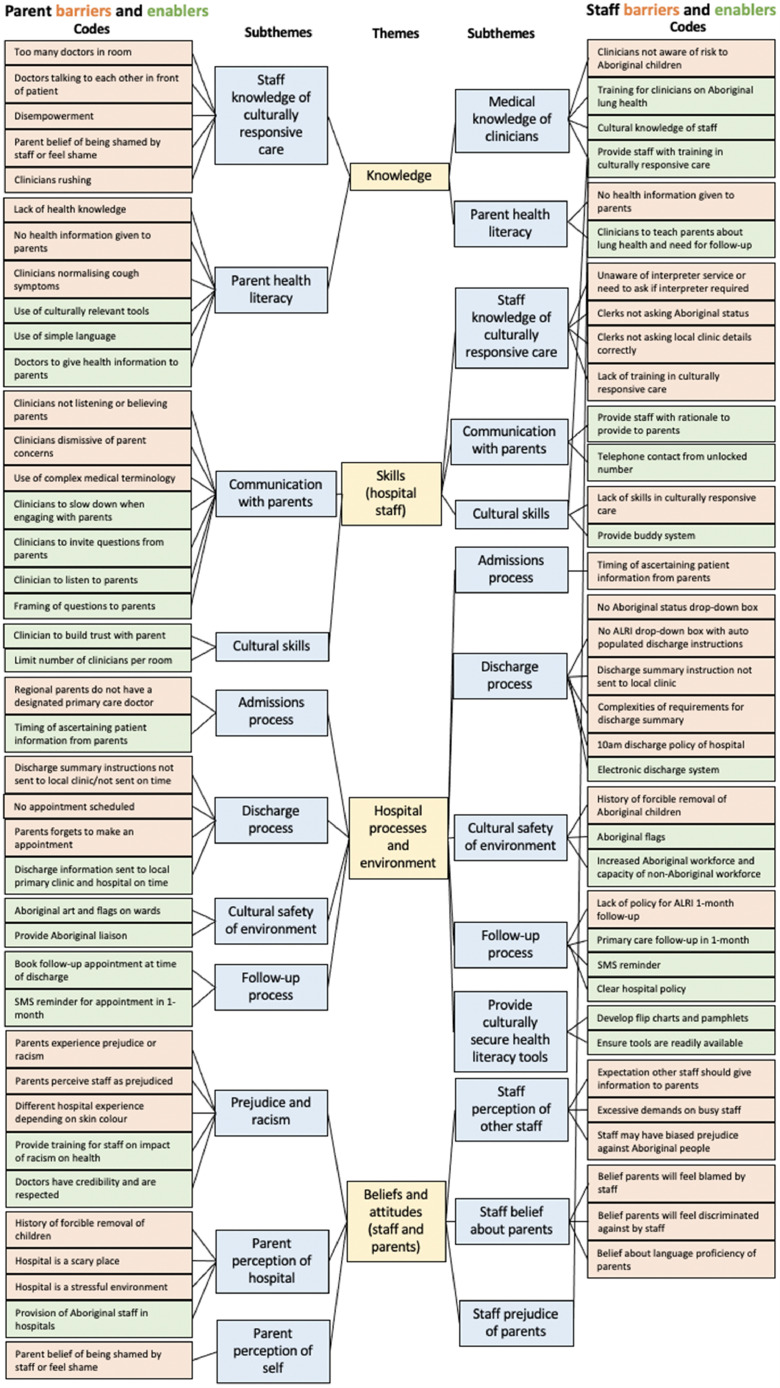

Key barriers and facilitators for parents and staff are summarised in Table-5,6,7 and 8 respectively. We identified four themes [(i)Knowledge, (ii)Skills, (iii)Hospital processes and environment and (iv)Beliefs and attitudes)] derived from 11 and 13-subthemes and 40 and 38-codes for parents and staff respectively (Figure 4). We report parents and hospital staff themes together.

Figure 4.

Steps required to facilitate medical follow-up 1-month post hospitalization for ALRI.

4. PARENTS

4.1. Knowledge

A lack of health knowledge was a key barrier for parents to attend medical follow-up one-month post hospital discharge. Lack of clinician knowledge about culturally responsive engagement and care, with clinicians rushing, talking amongst themselves was also a barrier. Some parents reported previous doctors’ normalisation of cough symptoms (i.e., “wet cough is normal") also prevented their medical help seeking. However, parents reported culturally responsive engagement and provision of health information using simple language and teaching tools facilitated their attendance for medical follow-up.

4.2. Skills

A common barrier reported by parents was poor communication skills of clinicians with parents, i.e., clinicians not listening, dismissing parent concerns, using complex medical terminology, or failing to explain their child's health condition, resulting in parents feeling disempowered to ask questions. Parents stated clinicians who engaged with parents in a culturally responsive way, e.g., built trust, limited the number of doctors in the patient room, took time during consultations, invited questions, and listened to parents facilitated them to attend follow-up.

4.3. Hospital environment and processes

Several parents reported that discharge summaries did not reach their local clinics, and therefore local clinicians were not able to action follow-up. Parents suggested that the hospital could schedule appointments and send SMS reminder-texts to facilitate medical follow-up. Lastly, parents thought the hospital environment could be more inclusive of Aboriginal people if Aboriginal flags and art were clearly visible throughout.

4.4. Beliefs and attitudes

Some parents believed being Aboriginal negatively affected the way hospital staff engaged with them. Several parents felt discriminated against based on their race. The barriers facing parents are contextualised with hospitals being viewed as a “scary” place for Aboriginal people, due in part to the historical forcible removal of children and belief that hospitals were places where people died. Feelings of insecurity, fear or being overwhelmed, were reported as hindering parents’ communication and likelihood of asking questions. Parents expressed the need for Aboriginal staff to improve their cultural safety and for cultural training for non-Aboriginal staff. Lastly, some parents expressed that doctors’ authority was respected and information given to parents by doctors was highly regarded.

5. STAFF

All staff approached for interview or focus group agreed to participate. One participant subsequently withdrew consent, due to concerns at their identifiability due to being Aboriginal.

5.1. Knowledge

Clinicians generally did not know that current guidelines recommend that children should be followed-up one-month post-discharge, and they did not fully appreciate the importance of providing culturally secure health information to parents. [9] Many staff reported lack of knowledge about culturally responsive care. Clerks generally did not know that establishing Aboriginality was a national health requirement. [22] Key facilitators identified included provision of staff training in culturally responsive care and training in best-practice management for Aboriginal children hospitalised with ALRI, including knowledge of and access to Aboriginal interpreter services.

5.2. Skills

While all staff had completed mandatory on-line cultural training, many staff expressed low confidence in their skills to engage with Aboriginal families in an effective way, due to limitations in the scope of the mandatory training. However, some thought more training (including role-modelling ‘buddy’ system) would improve their knowledge, skills, and confidence.

5.3. Hospital processes and environment

Some staff acknowledged that the hospital environment may be intimidating for families, and the placement of Aboriginal art and flags throughout the hospital may provide a more welcoming environment. The lack of hospital policy for arranging medical follow-up was a barrier. Deficiencies in the electronic discharge system, which lacked an ethnic status drop-down option or pre-populated templates, were identified as barriers for efficient transmission of discharge instructions to local primary clinicians. Time pressures and high workloads were identified as barriers to staff completion of discharge summaries and provision of parent-health information. Facilitators identified included improving the electronic discharge system and the availability of easily accessible health literacy tools. There was widespread clinician agreement that follow-up would be best managed in primary care rather than through hospital outpatient clinics.

5.4. Beliefs and attitudes

While all clinicians agreed parents should be given culturally secure health information, there was widespread belief that it was other clinicians’ roles to deliver it, i.e., doctors suggested nurses provide education, nurses believed doctors or ALOs should and ALOs reported that they had no capacity to undertake disease specific education for all Aboriginal families. It was identified that the ideal was that doctors should provide education to parents, with support and reinforcement by nurses and physiotherapists.

While all staff expressed positive attitudes toward caring for Aboriginal children, some staff recognised the implications of institutional racism and individual prejudice or bias against Aboriginal people, and how this could negatively impact parents’ engagement within the health system. A belief that offence may be caused if clerks asked about Aboriginal status was the reason Aboriginality was not routinely ascertained.

5.5. Knowledge mapping

Figure 5 outlines the six-phases with 12 essential steps from the point at which a parent presents to the hospital with their child, to completing one-month medical follow-up.

6. DISCUSSION

Arranging medical follow-up for Aboriginal children hospitalised with ALRIs is a complex process involving parents, hospital staff, hospital systems, primary care (ideally local Aboriginal Medical Services) and clear and compatible communication systems between providers. Multiple steps (Figure 4) are required to facilitate effective follow-up, from initial contact with clerks to dispatch of discharge instructions to primary care clinics. Failure to implement any step could compromise follow-up. These complexities highlight the need to systematically address existing inadequacies using a theory-informed implementation framework [11] to facilitate measurable and sustainable improvements that translate to improved health outcomes. We identified barriers and facilitators to medical follow-up from parents and from hospital staff. The four themes were [i] Knowledge, [ii] Skills, [iii] Hospital processes and environment and [iv] Beliefs and attitudes.

Key barriers to effectively arrange follow-up included clinicians being unaware of the need for follow-up post-ALRI and not providing health information to parents. In addition, hospital staff did not routinely ascertain patients’ Aboriginal status. Time-pressures and a belief that other staff were responsible for discussing lung health with parents further compounded the problem. Limitations of existing health electronic systems prevented creation and sending out discharge instructions to primary health clinicians. Lack of disease specific health literacy was identified as a key barrier for parents understanding their child's medical condition and being aware of the importance of medical follow-up. These findings are consistent with previous research into health seeking by Aboriginal parents for their child's chronic wet cough, where parents reported lack knowledge about chronic wet cough delayed help seeking. [12] Importantly, when Aboriginal parents were provided with culturally secure health information, the number of parents seeking medical help for their child almost tripled. [9] Given that health literacy is a key determinant of health and wellbeing that strongly influences individual health care utilisation and outcomes, [23] provision of health literacy is critical to empower Aboriginal people.

Quality healthcare and health literacy are key facilitators of better health outcomes, requiring both health systems and providers to be culturally responsive to Aboriginal perspectives. [24] Indeed, the Australian policy context recognises that improving cultural safety can improve access and quality health care for First Nations. [24] Our findings highlight a gap in knowledge and skills of hospital staff in providing culturally responsive care. Parents reported how clinicians’ failure to engage in a culturally secure way left parents feeling disempowered and without knowledge of their child's health condition, its management and need for follow-up. Disempowerment was exacerbated by clinicians feeling rushed when engaging with parents, talking amongst themselves about the child in front of parents, using complex medical terminology and failing to listen to parents about their child's health. Perceptions of prejudice and racism by staff toward Aboriginal families during the hospital experience, compounded their feelings of disempowerment, disengagement and mistrust. [25] These findings are consistent with the Australian literature and government reports regarding negative impacts of culturally insecure practices within the health system on patient outcomes. [[26],[27]] Implicit and explicit racism within non-Aboriginal health systems, and has been widely reported in other studies, [12] highlighting the importance of improving cultural competency of the clinical workforce, [28] provision of culturally secure health care and health information. [29]

Failures to identify Aboriginal status and correctly document local primary-care clinicians confirms previous investigations into similar failings within the health system [27] and therefore underscores the need to identify Aboriginal status. Our study outlined that important demographic information may best be obtained once a patient has settled on the ward, when families are under less stress, when a child's medical status has settled. Many hospital staff cited time pressure as a barrier to providing culturally appropriate health information to parents, and follow-up instructions to the primary care provider. While time pressures have been cited as a barrier to providing health information in previous research [30], when considering how lack of follow-up places patients at risk, the provision of basic information to parents and primary care providers is essential to improve health outcomes. Indeed, previous research has confirmed improved health outcomes when clinicians provide culturally secure health information [9].

Facilitators for parents were culturally secure engagement by clinicians, which includes listening to parents, inviting questions, taking time to explain medical processes and timelines, and providing health information. Parents also expressed that increasing the Aboriginal workforce would improve cultural security as families can more easily relate to Aboriginal staff. These strategies to enhance cultural engagement are consistent with both the research to date [12] and National recommendations. [29]

Study limitations included being a single-site study and results might not be applicable to other sites. However, the hospital is the only referral hospital for children in the state, with relatively large systems and staff numbers. Hence, identifying barriers and tailoring solutions in this context will likely be generalisable to other sites. Some of the steps necessary to facilitate follow-up might have to be amended for local contexts, for instance, where follow-up would routinely be provided by the same service (and not by the local clinic). Another limitation was that staff working in primary care were not interviewed to understand local context. However, health professionals from the primary-care sector were consulted in the preparatory stages of the project and a primary care liaison doctor (with strong relationships with and experience in primary-care) was interviewed.

7. Conclusion

The process for ensuring medical follow-up of Aboriginal children post-hospitalisation for ALRI complex and includes at least 12 steps. Many of the facilitators, such as ascertaining Aboriginal status, providing Aboriginal parents with culturally appropriate health information should be embedded in routine medical care for all health conditions. Cultural competence training is an important strategy to improve the knowledge and skills for staff to confidently engage with Aboriginal parents will facilitate medical follow-up.

Declaration of Competing Interest

Prof. Chang reports fees to the institution from work relating to being a IDMC Member of an unlicensed vaccine (GSK) and an advisory member of study design for unlicensed molecule for chronic cough (Merck) outside the submitted work. The rest authors declare no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Dr Laird was funded by a Perth Children's Hospital Foundation New Investigator Grant, A/Prof Schultz is supported by an NHMRC Trip fellowship [Grant APP1168022]. Prof Chang is supported by an NHMRC Practitioner Fellowship [Grant 1058213] and a Queensland Children's Hospital Foundation top-up [Grant 50286], and has received multiple NHMRC grants related to topics of cough and bronchiectasis including Centre of Research Excellence grants for lung disease [Grant 1040830] among Indigenous children and bronchiectasis [Grant 1170958].

Author contribution

Conceptualization: PL, AS, RW, FG, AC.

Data Curation: PL.

Figures: PL

Formal Analysis: PL, RW, FG, AS, JW.

Funding acquisition: AS, PL, RW, FG, AC.

Investigation: PL, AS, RW, FG, JW.

Literature search: PL

Methodology: AS, PL, RW, FG, AC.

Project Administration: PL.

Resources: PL, AS, AC, RW.

Supervision: AS, AC, RW.

Validation: PL, RW, AS, FG.

Visualization: PL.

Writing- original draft: PL, AS.

Writing-review and editing: PL, AS, RW, FG, AC, JW.

Data sharing statement

Data collected from the study has been included in the manuscript (Table 4, Table 5, Table 6, Table 7). The study protocol and informed consent forms are available if requested.

Table 8.

Facilitators for hospital staff to facilitate medical follow-up for Aboriginal children hospitalised with ALRI

| Theme | Subtheme | Domain | Exemplars or consensus of focus group |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1.Knowledge | 1•1Medical knowledge of clinicians | Training for clinicians on Aboriginal lung health | Focus group consensus: 1. Provide training to clinicians – at hospital and in primary care in person, online modules, and podcasts. 2. Easy access to best practice guidelines |

| 1•2 Cultural knowledge of staff | Training for staff on culturally responsive care | Provide training for clerks:1. How to ask Aboriginal status. 2. How to ask about local doctor. Doctor in Aboriginal health: “The question needs to be rephrased: ‘where is your local clinic?’” | |

| 1•3Parent health literacy | Clinicians to teach parents about lung health and need for follow-up | Focus group consensus:1. Doctors teach parents on wards. 2. Nurses provide follow-up support education. 3. Clinicians ensure families given pamphlet with instructions | |

| 2. Skills | 2•1Communication with parents | Provide staff with rationale to provide to parents | Aboriginal health practitioner: “We need to make sure we have a reason why we need to do these things and explain that to our families...” |

| Telephone contact from unblocked number | Nurse in Aboriginal health: “We have had the (telephone) number of our unit unblocked so our families know it is us. We have an easier time getting hold of families since we made this change.” | ||

| 2•2Cultural skills | Provide staff with training in culturally responsive care and engagement | Clerk 4: “It would be really helpful if we had mandatory training, so we know how to talk with families with actual examples...” Doctor 6: “It was not until now talking to you in person that I really understood the reason why we are following-up these kids and importance of engaging effectively with families. Most docs just won't get this from one lecture…Also, if you could offer … cultural training for all the doctors. We need practical ideas on how to engage. You will get more engagement and motivation by docs that way.” A lead clerk: “The clerks found the training in culturally secure engagement very helpful, and I would like all clerks to do it as I think it will help get the right information for the families.” Clinical nurse specialist: “…what we really need is practical training in how to work with families...” | |

| Provide role modelling | Doctor 2: “I think observing someone who is confident engaging with Aboriginal families would be very helpful. I can understand this may be logistically difficult, but it would be very helpful.” Doctor 3: “A buddy opportunity where I can observe a fellow clinician engaging with an Aboriginal family on the ward would be very helpful.” | ||

| 3.Hospital processes and environment | 3•1Cultural safety of environment | Aboriginal flags | Clerk 2: “I think the Aboriginal flags on the desk would be helpful...” |

| Increase Aboriginal workforce and capacity of non-Aboriginal workforce | Doctor in Aboriginal health: “We have 2 ALOs for the whole hospital and their workload is too high. We need to improve the cultural capacity of our non-Aboriginal workforce and we need more ALOs employed.” | ||

| 3•2Provide culturally secure health literacy tools | Develop flip charts and pamphlets | Nurse in Aboriginal health: “Some families can't read, so we do not just want to give them a flyer. We need tools that will explain things to families, so they understand...” | |

| Ensure tools are readily available | Focus group feedback:1. Tools to easily accessible in clinical workrooms of each ward. 2. Tools need to be accessible electronically on hospital intranet | ||

| 3•3Admissions process | Timing of ascertaining patient information from parents | A lead Clerk: “The ward is calmer. We can have a nice conversation at admissions. It is a nicer situation for families as the ward gives everyone breathing time.” | |

| 3•4Discharge process | Electronic discharge system | Focus group consensus:1. Add Aboriginal status to electronic discharge system. 2. Ensure local clinic is populated. 3. Template to be embedded into electronic system with clear instructions for local primary care clinician to know how to follow-up | |

| 3•5Follow-up process | Primary care follow-up in 1-month | Focus group consensus: Follow-up should happen in primary care not at hospital | |

| SMS reminder | Focus group consensus:Send automated SMS reminder to patients to book an appointment with primary care doctor | ||

| Clear hospital policy | Develop hospital policy for provision of culturally secure health information and follow-up for Aboriginal children hospitalised with ALRI, with clear directives on roles and responsibilities and processes. | ||

| 4. Professional role and identity | 4•1 Staff prejudice of parents | Provide staff with training in culturally responsive care | Provide staff with training in culturally responsive care |

Abbreviations:

ALO: Aboriginal Liaison Officer

SMS: Short Message Service

Table 4.

Demographics of parents interviewed

| ID Number | Age of child (in years) | Diagnosis | Relationship to child | Aboriginality of parent | Location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0.6 | Bronchiolitis | Mum | (non-Aboriginal) | Mid-west |

| 2 | 9.8 | Acute exacerbation of Bronchiectasis | Mum | Aboriginal | Kimberley |

| 3 | 1.1 | Bronchiolitis | Mum | Aboriginal | Pilbara and Metropolitan Perth |

| 4 | 1.4 | Viral Induced Wheeze | Mum | Aboriginal | Metropolitan Perth |

| 5 | 1.1 | Bronchiolitis | Mum | Aboriginal | Kimberley |

| 6, 7 | 2.4 | Pneumonia | Mum & Dad | Aboriginal | Mid-west |

| 8 | 0.9 | Bronchiolitis | Mum | Aboriginal | Metropolitan Perth |

| 9 | 1.8 | Bronchiolitis | Mum | Aboriginal | Metropolitan Perth |

| 10 | 2.8 | Viral Induced Wheeze | Mum | Aboriginal | Metropolitan Perth |

| 11,12 | 0.4 | Bronchiolitis | Mum & Dad | Aboriginal | Metropolitan Perth |

| 13 | 9.0 | Aspiration Pneumonia | Mum | Aboriginal | South-west |

| 14 | 10.6 | Chronic Lung Disease | Mum | Aboriginal | Goldfields and South-west |

| 15 | 1.2 | Bronchiolitis/ Pneumonia | Mum | Aboriginal | Metropolitan Perth |

| 16 | 0.11 | Acute bronchiolitis | Foster Mum | Aboriginal | Metropolitan Perth |

| 17 | 7.4 | Acute exacerbation of Bronchiectasis | Grandmother and leader in remote community | Aboriginal | Kimberley |

| 18 | 3.2 | Recurrent bronchiolitis | Mum | Aboriginal | Kimberley |

Table 5.

Barriers for parents to follow-up with their child hospitalised with ALRI post-discharge

| Theme | Sub-theme | Code | Exemplars |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Knowledge | 1•1Staff knowledge of culturally responsive care | Many doctors in room | Mum 4: “When the doctors … come into your room – there are so many doctors all standing around and talking about bubba and you don't have any clue what they are saying…us black fellas…feel shame to speak up. And you don't know what's going on. And they don't ask you what you think.” |

| Doctors talking to each other in front of patient and family | Mum 3: “When they (doctors) do the rounds, they all talk amongst themselves, and you have no idea what is going on.” | ||

| Disempowerment | Mum 2: “Many parents they won't ask – they are afraid to ask… a mum from up north...would just nod at everything the doctors said.” Mum 1: “The doctors don't help…A lot of doctors’ ridicule. They think they know everything. And they don't listen.” Mum 10: “And I don't know if doctors don't listen because I am a single mum with 3 children. They say to me: ‘Oh are you struggling’ and that makes me feel like they are saying it's me with the problem and not that the kids are sick…I was going around and around in circles. They just fob it off a lot.” | ||

| Parent belief of being “shamed” by staff or feel shame | Mum 2: “The physiotherapist didn't really approach (child) in the right way. (child) was scared and had shame and she would hide... I don't think the staff understand about what it is like for Aboriginal people coming from a remote community. The ways the staff talk can make us feel unwelcome and shamed." | ||

| Clinicians rushing | Mum 2: “Some of the (physiotherapists) would rush and force her and she would get very frightened.” | ||

| 1•2Parent health literacy | No health knowledge | Mum 4: “I didn't know what was wrong with her breathing or that she needed follow-up at the clinic when we left.” | |

| No health information or explanations given to parents by clinicians | Mum 2: “When (child) came in with pneumonia when she was 5 weeks old...There was no information on what I needed to do…I was never told she was at risk. Now she has bronchiectasis and if I had known, I could have got her followed-up...” Mum 3: “My son…has been in and out of hospital his whole life…you are the first person to ever talk to me about lung health and his lungs. I would have thought with my son being born with lung disease from prematurity that we would have had follow-up arranged and information given… but I would have thought it would be more of a priority.” Mum 3: “If they are going to take him off high flow, they just take him off. They don't tell me what the process is – for instance – we are going to take him off high flow, go to regular oxygen and then this is when we are thinking of sending you home. Instead, I have no idea what the timeline or process is. They just took him straight off and I am not clear... A lot of the time you don't want to ask.” | ||

| Clinicians normalising cough symptoms | Mum 6: “I have been in hospital a lot with (daughter) for her breathing… this is the first time anyone has properly explained to me about what to look for when we go home…Nobody ever worried about her coughing before. They all just say that it's normal for her to cough as she was born so early.” | ||

| 2. Skills (hospital staff) | 2•1 Staff communication with parents | Clinicians not listening or believing parents | Mum 4: “…we get admitted and nobody listens to me… it makes it so stressful.” Mum 2: “I felt some of the staff were not so good at listening to us. It felt very much like it had to happen the hospital way and we were not getting heard.” Mum 10: “When he was sick, I went to the doctor and they just kind of fobbed me off. They didn't take it seriously that he was sick … I still just feel like I don't get listened to...” Mum 11: “A lot of the time I feel like they are not listening…And I feel like they think I am overly anxious… but I know the difference and I am his advocate...If I wasn't insisting, I worry that they would have sent me home and he would have deteriorated” |

| Clinicians dismissive of parent concerns | Aboriginal co-researcher case notes: “Some families say to me they don't see the point in following-up with (primary care doctor) because doctors dismiss them. Then they end up in hospital with bronchiolitis and they can't breathe. So, they think there is no point in going back as he will dismiss them again.” Mum 10: “No I wouldn't go back to the (primary care doctor), because I went to him in the first place, and he just told me he had asthma and then we ended up in hospital.” | ||

| Use of complex medical terminology by Clinicians | Grandmother: “Don't use big words when you speak to them (families)…” Mum 3: “The doctors would do their rounds and talk about your child in front of you. And then when the doctors leave, the other mums would … ask me ‘What were the doctors saying?’ because they didn't understand. They would ask me to interpret for them. Trouble was that half the time I did not know what the doctors were saying as they were using medical terms.” | ||

| 3. Hospital processes and environment | 3•1 Admissions process | Regional parents do not have a designated primary care doctor | Mum 2: “The other thing is that (child) doesn't have a GP. We only have one doctor in the clinic one day a week and the doctor changes all the time. So, if they ask a family who the doctor is, they are probably going to say they don't have a doctor because they don't remember his name or the doctor changes so much.” |

| 3̏•2 Discharge processes | Discharge summary and instructions not sent to local clinic/not sent on time | Mum 2: “For our last admission…the clinic had to ring up to get information on what to do for her management almost 3 months later – I should have had that information before I left the hospital…The doctor at the hospital wanted antibiotic medicine. But then the information never got sent …So, months later we are still waiting for her medicine. And then her port needed flushing but nobody from the hospital is explaining that to the clinic. So, then her port gets blocked, and we have to get a whole new one put in. And that is very painful and stressful because it means we have to put her to sleep again and then there's the whole recovery after. But if everyone at the hospital was communicating with the clinic back home all of this could be avoided.” Grandmother: “The problem is (local clinic) haven't received the discharge summary from the hospital – this is months later…the clinic needs the time to sort what the doctor at the hospital wants…We only have a doctor in the clinic one day a week. So, it is really important to have information in the summary for the Aboriginal health worker and nurse to know what is needed to make it easier when the doctor comes. That way the doctor knows what needs to happen.” | |

| No appointment scheduled | Mum 2:“We got sent home with no follow-up afterwards...” | ||

| Parent forgets to make appointment | Mum 2: “Families may forget to make the appointment.” Grandmother: “If you tell the parents to make the appointment they might forget and if you give them the paper, they might lose it or throw it in the bin, especially if they are going all the way back to community from Perth...” | ||

| 4. Beliefs and attitudes | 4•1 Prejudice and racism | Parents experience prejudice or racism | Mum 10: “I felt like they were saying I was overreacting…And I have wondered if it is because I am Aboriginal… I think it (Aboriginality) does come into it a little bit to be honest.” |

| Parents perceive staff as prejudiced | Mum 15: “I work at (hospital) as a nurse. I have seen the same standard of care given to both Aboriginal and other patients. But there have been occasions where the Aboriginal patient has got very upset because they feel the staff are being discriminating due to their race. One lady had to be isolated due to an infection. Despite staff explaining why she had to be isolated, she insisted the staff were being racist. Sometimes, I think some Aboriginal patients are convinced staff are racist… I can see why it happens because I see racism and attitudes from staff at the hospital. Sometimes it's subtle. I often hear the nurses say ‘Oh she (Aboriginal patient) won't show up. She'll be walkabout’… Some nurses will predict what the Aboriginal patients will do before the patient has even had the chance to do anything. The doctors can do the same. And actually, even … clerks can have an attitude that is condescending towards Aboriginal patients…I understand why Aboriginal patients end up feeling that they are being discriminated against. When you add up all the looks and the little comments, then they end up just expecting it to happen to them...” | ||

| Different hospital experience depending on skin colour | Mum 10: “I have 2 very white children and one that is very, very tanned. If I go in with my tanned child, I have had to wait…They made me feel stupid…And I don't know if that is because it's her skin colouring or not, but I don't need to wait that long with my white children… I wonder. I know outside of the hospital I get a lot more judgement with my tanned child.” Mum 11: “Yes I think race comes into it. The difference is, when I come in with …the fair ones I get treated very differently…my husband…is quite dark. So, when he comes in then, yeah, they talk differently to him…with me, because I look fair, they [any staff, but often, senior doctors] are really…understanding. But then with the dark kids or if my husband is with me, the tone is completely different, and they are more dismissive. And I don't know if they mean it or because they seem like very lovely genuine people, whether they realise they are doing it? But it is noticeably different …With my husband at the hospital, he says he will wait in the car, and let me go it, because he is dark, and I am fairer…because he thinks I will get the help with him not there…” | ||

| 4•2 Parent perception of hospital | History of forcible removal of children | Mum 1: “For lot of Aboriginal families, it would be them thinking the worse thing will happen. They might think they have done something wrong. They would worry they would be in trouble for doing the wrong thing even though they didn't do anything wrong. I think many Aboriginal people have a fear – especially from fostering point of view they are afraid the child might be taken as they will be blamed.” | |

| Hospital is a scary place | Mum 4: “Hospitals are scary places for black fellas...We know stories of bad things that have happened to other babies, and we think if it can happen to them, it can happen to us.” Mum 8: “It was really scary for us because the last time we came here our daughter died here. It is hard to come back.” | ||

| Hospital is a stressful environment | Mum 2: “When families are first coming to the hospital, especially through the emergency, they are really stressed and it's a scary time. It's not the best time to ask families all these questions about contact people and who the doctor is. It's too rushed." Grandmother: “It's very overwhelming for our people when we come from remote communities when we don't have our family here to help us.” | ||

| 4•3 Parent perception of self | Parent belief of being “shamed” by staff or feel shame | Mum 2: “(Aboriginal people) might have shame that they are going to be growled [blamed].” |

Abbreviations:

GP: General Practice doctor

Table 6.

Facilitators for parents to follow-up with their child hospitalised with ALRI post-discharge

| Theme | Subtheme | Code | Exemplars |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Knowledge | 1•1 Parent health literacy | Use of culturally relevant tools | Mum 2: “The flip chart helps to explain to the family the importance of follow-up -yes.” Mum 3: “I would love a pamphlet to teach me. I want information. I have all this time when I am in here and I want to learn. So, teach me. Nobody told me what to look out for. They tell me what to look out for when he can't breathe, but nobody is telling me what to do long term. It would be nice to know the warning signs for long term.” Mum 9: “You giving me all this information is very helpful to help me understand it all...” Mum 11: “With you explaining to me about his lungs and the cough, I would definitely go to the GP and follow-up with his cough. I would take this paper to show the doctor, so he knows what to do. I would tell him you spoke with me about it, would you mind if I mentioned your name?” |

| Use of simple language | Mum 4: “It would help if doctors gave us explanations in plain English. Many of our mob don't understand the high jargon doctor's use. So, it is good to explain about the cough and breathing simply…” Mum 5: Yes, the flip chart is great, but you have to change the words because people don't understand acute and chronic. We understand about pneumonia and bronchiolitis and how you get them with a fever and hard breathing. But you need to explain the cough for a long time. You need to say things like “a long time” not chronic.” | ||

| Doctors to give health information to parents | Mum 3: “Maybe once they have finished checking the patient over and talking amongst themselves one of them could actually come over and tell you clearly this is what they want to do… If they took 5 minutes to explain it would help…I would prefer if they (doctors) could explain things more clearly. A clearer understanding to the parents would help” Mum 5: “I felt confused and didn't know what was going on until you explained to me about the breathing problem and the coughing. I think you need to explain why we need to see the doctor back at home. When we come into hospital, she's got a fever and she has trouble breathing. So, we need to understand why the coughing is a problem even when the fever goes, and the breathing is better." | ||

| 2. Skills (hospital staff) | 2•1Cultural skills | Clinician to build trust with parent | Mum 2: It can take time to build her trust. You took the time with her and you earned her trust. She is good with you. But she won't do her (treatment) with the other (clinicians) because she doesn't trust them.” |

| Limit number of clinicians in patient room | Clinicians to have skills in engaging with families. Grandmother: “It is best if only one doctor comes into the room…Especially if a lot of them (doctors) come into the room.” | ||

| 2•2 Staff communication with parents | Clinicians to slow down when engaging with parents | Mum 3: “…and don't rush. You have to take time with Aboriginal people. They will watch you when you come into the room. They will figure out in seconds if they are going to listen to you or talk to you just by your body language. They will pick up on the cues and if you are in a rush, they will shut down and withdraw away. I know doctors and nurses are always busy, but rushing will just put us off.” | |

| Clinicians to invite questions from parents | Mum 2: “I think asking the parents what they think and acknowledge that we know what is going on with our child.”Grandmother: “The quiet ones won't ask questions. Especially if a lot of them (doctors) come into the room. So, the doctor needs to ask the parent ‘what do you think?’…We need to tell the parents: ‘you gotta ask!’’ | ||

| Clinician to listen to parents | Mum 2: “ask us and listen to what we say. If you ask, ‘Does it hurt?’ then listen for the response – and if we tell you it hurts, then listen!” | ||

| Framing of questions to parents | Mum 2: “…maybe don't ask about the GP (Primary-care doctor) because the GPs change all the time, and we don't see the same doctor. Maybe ask which clinic they go to instead. And send the information to the local clinic because they will track the kids down.” | ||

| 3. Hospital process and environment | 3•1 Cultural safety of environment | Aboriginal art and flags on the wards | Mum 4: “I noticed all the Aboriginal art on the walls. I love it. One of my aunties did the painting on (ward). I think if you had the Aboriginal flag at the main desks, it would also make Aboriginal families feel welcome.” |

| Provide Aboriginal liaison staff | Mum 9: “I think if there were more AHPs, it would be better. Aboriginal people feel a lot more comfortable talking to Aboriginal people...” | ||

| 3•2 Admissions process | Timing of ascertaining patient information from parents | Mum 2: “When families are first coming to the hospital, especially through the Emergency, they are really stressed and it's a scary time. It's not the best time to ask families all these questions about contact people and who the doctor is.... So maybe ask those questions on the ward when things have settled down.” | |

| 3•3 Discharge process | Discharge information sent to local primary clinic and hospital on time | Mum 4: “(Hospital doctors) need to have a plan …I need the specialist in Perth to talk to the doctors back home and make a plan so that everyone knows what to do.” | |

| 3•4 Follow-up process | Book follow-up appointment at time of discharge | Mum 2: “I think a good way is to have someone down here to book the appointment for them. Then the clinics can follow-up with their child. I go to the local clinic as they know her. Where I come from there are different doctors coming and going and so that can make it difficult. But usually, the clinic will send out the reminder for the family and they can drive out and drop off mail.” | |

| SMS reminder for appointment in 1-month | Mum 3: “I find the SMS system very helpful. If it recommended that families need to follow-up in a month then send the SMS... So, the SMS will remind me, so I don't forget. I have a hectic household. I also find getting the discharge letter helpful.” | ||

| Clinic will ensure follow-up | Grandmother: “The clinic will make sure the follow-up happens. Families travel around. So, if the patient is in a different community- the clinic will know, and they will tell the other community clinics to follow-up instead...” | ||

| 4. Beliefs and attitudes (staff and parents) | 4.1 Parent perception of staff | Provide training for staff on impact of racism in health | Mum 15: “…And yes, we also need to make sure staff are well trained in how to help patients feel safe and listened to.”Mum 2: “... the staff there don't know to do it. They need training so that can happen...” |

| Doctors have credibility and are respected | Mum 3: “Now that the respiratory doctor is involved, I feel a massive relief that they can look after his lungs.”Grandmother: “Hearing it from the doctor is the most important. He's the one they respect...” | ||

| 4.2 Parent perception of hospitals | Provision of Aboriginal staff in hospitals | Mum 15: “It is difficult for hospital staff. I think sometimes staff try everything, and it doesn't work, and patients are convinced staff decisions/actions are made based on their race. In these instances, we need Aboriginal staff – liaison staff to talk with the patients.” Mum 2: “I think training up Aboriginal workers is important...” |

Abbreviations:

GP: General Practice doctor

AHP: Aboriginal Health Practitioner

SMS: Short Message Service

Table 7.

Barriers for staff to facilitate primary care follow-up for Aboriginal children hospitalised with ALRI

| Theme | Sub-theme | Code | Exemplars |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Knowledge | 1•1Medical knowledge of clinicians | Clinicians not aware of risk to Aboriginal children and need for follow-up at 1 month | Focus group consensus of widespread unawareness by clinicians |

| 1•2Parent health literacy | No health information given to parents | Widespread unawareness of need to give parents health information in culturally secure way. Doctor 6: “I did not know that teaching parents about bronchiolitis and follow-up with the flip chart would have an impact. I must admit, I haven't ever done this...” | |

| 1•3Staff knowledge of culturally responsive care | Unaware of interpreter service or need to ask if interpreter required | Nurse 3: “I did not know we had an interpreter service for Aboriginal languages. I had never considered Aboriginal languages as a need for interpreter services.” Doctor 1: “There are so many Aboriginal languages. How do you know which one they speak? I did not know that interpreter services could be organised for our Aboriginal patients.” | |

| Clerks not asking Aboriginal status | Clerk 6: “I did not realise it was a requirement to ask. We don't like to ask about ATSI (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander status) as we are worried that we will offend people” Doctor Aboriginal health: “The problem is that Aboriginal status is not being filled in. We can't flag kids if we don't have this information up to date. It (Aboriginal status) is not being asked routinely despite it being a requirement.” | ||

| Clerks not asking for local clinic details | Doctor Aboriginal health: “The trouble is, our patients are asked who their local GP is. They say they don't have one – which is true as there is no regular GP in communities. There are locums and they change every 2-weeks.” Clerk 4: “When we ask if they have a GP, Aboriginal families will often tell us they don't have a GP, so we just leave it blank.” | ||

| Lack of staff training in culturally responsive care | Clerk 5: “We don't get taught how to do things (culturally informed engagement with families).” | ||

| 2. Skills | 2•1Cultural security skills | Lack of skills in culturally responsive care | Clerk 3: “We have never been told how to engage with families before and we have not been taught how to ask about Aboriginal status.” Clinical nurse specialist: “We have not had training in how to talk with families. None of the (current mandatory) training goes through specifics of how to engage.” |

| 3. Hospital process and environment | 3•1Cultural safety of environment | History of forcible removal of Aboriginal children | Focus group Aboriginal health: Acknowledgement of history of forcible removal of children from hospitals creates negative stigma of hospitals for Aboriginal families. |

| 3•2Admissions process | Timing of ascertaining patient information from parents | A head clerk: “In the Emergency it can be very stressful for families as their child is very sick. There is often no time to ask about local clinic and best contact...” | |

| 3•3Discharge process | No Aboriginal status drop-down box in electronic discharge system | Doctor 1: “Currently there is nothing in (electronic discharge system) to distinguish Aboriginal patients, so we need that...” | |

| No ALRI drop-down box with auto populated discharge instructions for primary care doctors | Doctor 1: “…there is no pre-populated templates in the system to make standard discharge instructions quick and easy for doctors to send to local doctors, so we need to embed a template in discharge instructions with the letter to (primary care doctor). Our system is clunky and difficult to use.” | ||

| Discharge summary instructions not sent to local clinic/not sent on time | Respiratory consultant: “I don't do discharge summaries for my patients who are discharged on the weekends.” Focus group consensus:1. If discharge summaries are not completed then they will not be sent. 2. If doctors are busy, completed discharge summaries can be delayed | ||

| Complexities of requirements for discharge summary | Discharge doctor: “Any extra steps for busy residents will be a barrier as doctors are very busy. For instance – if it says, ‘no GP’ (Primary-care doctor) docs will not likely follow-up. If we expect docs to go onto (department) website and copy and paste links – it won't happen. Discharge summaries need to happen on the same day also. No doctor is going to copy and write out the link for the GP letter or the training online...” | ||

| 10 am discharge policy of hospital | Discharge doctor: “… discharge needs to happen before 10am – so it's very busy." Nurse 4: “The last couple of Aboriginal boys I looked after- the whole discharge process was such a rush as they had to get a plane to fly home. There was no time to do all the things for follow-up.” | ||

| 3•4Follow-up process | Lack of policy for ALRI 1-month follow-up | Department of General Paediatrics focus group consensus: There is no policy or procedure for routine follow-up for Aboriginal children with ALRI. | |

| 4Beliefs and attitudes (staff and parents) | 4•1Staff views of other staff roles | Expectation other staff should give health information to parents | Doctor 5: “The nurses should teach the parents as they get to know the patients as they spend more time with them.” Nurse 5: “I think the ALO is the best one to teach patients as they are Aboriginal and can relate best to the family. Aboriginal families don't open up to us.” |

| Excessive demands on busy staff | Nurse 6: “The problem with the flip chart is that it is just another time-consuming thing, and we are so busy...” | ||

| Staff may have bias/prejudice against Aboriginal people | Consensus of Aboriginal health staff focus group:1. Important to acknowledge institutional racism within hospital. 2. Important to acknowledge individual bias and prejudice within hospital | ||

| 4•2Staff belief about parents | Belief parents will feel blamed by staff | Clerk 8: “Some families seem afraid to give information to us. I feel like they might think they are in trouble.” | |

| Belief parents will feel discriminated against by staff | Clerk 5: “Isn't it discriminatory to identify Aboriginal people and single them out and treat them differently? Won't it be seen as discrimination if Aboriginal people are required to have specific follow-up and not other patients?” AHP: “I worry that families will feel discriminated against. They might wonder why it is that only Aboriginal families have to follow-up with their doctor? I know some Aboriginal families have asked me why there are all these extra immunisations they have to have that the white fellas don't have to get…Why are we focussing on Aboriginal people and how do we tell our mob, so they don't feel shame?” Clerk 3: “We don't always ask about Aboriginal status – we ask if it is obvious, they look Aboriginal, but we worry we might offend people by asking.” Clerk 6: “I would only ask someone who obviously looked Aboriginal if they were Aboriginal as I would not want to offend them if they are not Aboriginal.” | ||

| Belief about language proficiency of parents | Nurse 1: “We don't use interpreters because most patients have decent English, and we can talk medical knowledge to them...” |

Abbreviations:

ATSI: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander

GP: General Practice doctor

ALRI: Acute Lower Respiratory Tract Infections

ALO: Aboriginal Liaison Officer

AHP: Aboriginal Health Practitioner

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors thank the local Aboriginal families and staff at the hospital for their support and collaboration in all aspects of the planning and operation of the study.

The authors would like to thank the Aboriginal families and the staff at the hospital who agreed to participate in the study. We would like to thank the external stakeholders who provided valuable information to assist in developing processes for implementation. We would like to thank Sonali Dodangoda (BSc, MInfectDis), Wal-yan Centre for Respiratory Research, Telethon Kids Institute for creation of figures and infographics. The project was funded by the Western Australian Health Translation Network knowledge translation grant.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100239.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

REFERENCES

- 1.Bailey EJ, Maclennan C, Morris PS, Kruske SG, Brown N, Chang AB. Risks of severity and readmission of Indigenous and non-Indigenous children hospitalised for bronchiolitis. J Paediatr Child Health. 2009;45(10):593–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2009.01571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.O'Grady KA, Torzillo PJ, Chang AB. Hospitalisation of Indigenous children in the Northern Territory for lower respiratory illness in the first year of life. Med J Aust. 2010;192(10):586–590. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2010.tb03643.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore H, Burgner D, Carville K, Jacoby P, Richmond P, Lehmann D. Diverging trends for lower respiratory infections in non-Aboriginal and Aboriginal children. J Paediatr Child Health. 2007;43(6):451–457. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2007.01110.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chang AB, Masel JP, Boyce NC, Torzillo PJ. Respiratory morbidity in central Australian Aboriginal children with alveolar lobar abnormalities. Med J Aust. 2003;178(10):490–494. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05322.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.McCallum GB, Chatfield MD, Morris PS, Chang AB. Risk factors for adverse outcomes of Indigenous infants hospitalized with bronchiolitis. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2016;51(6):613–623. doi: 10.1002/ppul.23342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chang AB, Bush A, Grimwood K. Bronchiectasis in children: diagnosis and treatment. Lancet. 2018;392(10150):866–879. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31554-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.National Aboriginal Community . RACGP; East Melbourne, Vic: 2018. Controlled Health Organisation and The Royal Australian College of General Practitioners: National guide to a preventive health assessment for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people. 3rd edn. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Smylie J, Olding M, Ziegler C. Sharing What We Know about Living a Good Life: Indigenous Approaches to Knowledge Translation. J Can Health Libr Assoc. 2014;35:16–23. doi: 10.5596/c14-009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Laird P, Walker R, Lane M, Totterdell J, Chang AB, Schultz A. Recognition and Management of Protracted Bacterial Bronchitis in Australian Aboriginal Children: A Knowledge Translation Approach. Chest. 2021;159(1):249–258. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.06.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Smith . Zed Books; 2012. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. Second edition. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, Kirsh SR, Alexander JA, Lowery JC. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implement Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.D'Sylva P, Walker R, Lane M, Chang AB, Schultz A. Chronic wet cough in Aboriginal children: It's not just a cough. J Paediatr Child Health. 2018;55:833–843. doi: 10.1111/jpc.14305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Laird P LM, Walker R, Chang AB, Schultz A. Telethon Kids Institute, University of Western Australia; 2018. Educational Resource, Chronic Lung Sickness. https://www.telethonkids.org.au/contentassets/b50404b2050d4c1e92cb7225fc3c2047/wetcough-flipchart.pdf Date last updated 20.12.2019. Date last accessed 14.04.2020. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19(6):349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS), 3235.0 Population by Age and Sex, Regions of Australia. https://www.abs.gov.au/AUSSTATS/abs@.nsf/DetailsPage/3235.02016?OpenDocument Date last updated 28.08. 2017 Date last accessed 6.5.20.

- 16.Patton M. 2nd ed. Sage; Newbury Park, California: 1990. Qualitative Evaluation and Research Methods. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Braun V, Clarke V. To saturate or not to saturate? Questioning data saturation as a useful concept for thematic analysis and sample-size rationales. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health. 2021;13:201–216. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2020 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ebener S KA, Shademani R, Compernolle L, Beltran M, Lansang M, Lippman M. Vol. 84. Bulletin of the World Health Organisation; 2006. pp. 636–642. (Knowledge mapping as a technique to support knowledge translation). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Creswell J, Creswell JD. SAGE Publications, Inc; Thousand Oaks, California: 2018. Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches. 5th ed. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vail E. Knowledge mapping, getting started in knowledge management. CIMS. Babson Park Center for Information Management Studies; MA: 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 22.National best practice guidelines for collecting Indigenous status in health data sets. In: Welfare AIoHa, editor. Cat no IHW 29. Canberra: AIHW; 2010.

- 23.de Wit L, Fenenga C, Giammarchi C. Community-based initiatives improving critical health literacy: a systematic review and meta-synthesis of qualitative evidence. BMC Public Health. 2017;18(1):40. doi: 10.1186/s12889-017-4570-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.AHMAC . AHMAC (Australian Health Ministers’ Advisory Council); Canberra: 2016. Cultural Respect Framework 2016–26 for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health: a national approach to building a culturally respectful health system. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lowell A, Maypilama E, Yikaniwuy S, Rrapa E, Williams R, Dunn S. Hiding the story": indigenous consumer concerns about communication related to chronic disease in one remote region of Australia. Int J Speech Lang Pathol. 2012;14(3):200–208. doi: 10.3109/17549507.2012.663791. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Henry BR, Houston S, Mooney GH. Institutional racism in Australian healthcare: a plea for decency. Med J Aust. 2004;180(10):517–520. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durey A, Thompson SC, Wood M. Time to bring down the twin towers in poor Aboriginal hospital care: addressing institutional racism and misunderstandings in communication. Intern Med J. 2012;42(1):17–22. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.2011.02628.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Walker R, Schultz C, Sonn C. Working together: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander mental health and wellbeing principles and practice; 2014. Cultural competence–Transforming policy, services, programs and practice. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arabena K. Future initiatives to improve the health and wellbeing of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. Med J Aust. 2013;199(1):22. doi: 10.5694/mja13.10816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Laird P, Walker R, Lane M, Chang AB, Schultz A. We won't find what we don't look for: Identifying barriers and enablers of chronic wet cough in Aboriginal children. Respirology. 2020;25(4):383–392. doi: 10.1111/resp.13642. Epub 2019 Jul 25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.