Summary

Background: Rohingya girls living in the refugee camps in Bangladesh are disproportionately vulnerable to child marriages and teenage pregnancies. This study examines the factors affecting child marriage and contraceptive use among Rohingya girls who have experienced child marriages.

Methods: We collected and analysed quantitative and qualitative data from adolescent Rohingya girls (age 10-19 years) who experienced child marriages. The quantitative data (n=96) came from a cross-sectional survey, and the qualitative data (n=18) from in-depth interviews conducted in the world's largest refugee camp located in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. We also interviewed service providers (n=9) of reproductive healthcare services to gain their perspectives regarding contraceptive use among these young girls. We used descriptive statistics to characterise the girls’ demographic profiles, ages at their first marriages, and contraceptive use. Thematic analysis was used for the qualitative data to identify key factors influencing child marriage and contraceptive use among these girls.

Findings: On average, the adolescent female participants had been 15.7 years old when they were first married. Over 80% had given birth during the two years before the survey or were pregnant during time of the data collection. The main factors that influenced child marriage were found to be perceptions regarding the physical and mental maturity for marriage, social norms, insecurity, family honour, preferences for younger brides and the relaxed enforcement of the minimum legal age for marriage. A third (34%) of the girls said they were using contraceptives on the week when the study was conducted. The desire for children, religious beliefs, misapprehension about contraception and long waiting periods in facility-based health services and current service provision were the main factors influencing contraceptive use. Depo Provera injections and pills were the dominant methods of contraception. Contraceptive use during the period between marriage and the first childbirth is rare.

Interpretation: Girl child marriage is common in Rohingya camps. Contraceptive use is rare among newly married girls before they give birth for the first time. The involvement of female and male Rohingya volunteers for outreach services can be catalytic in promoting contraceptive use.

Funding: La Trobe Asia, La Trobe University, Melbourne, Australia.

Bengali translation of the abstract in Appendix 1

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

In spite of some commonalities, the situation with regard to child marriage in each refugee setting is unique and so are the factors affecting this practice. However, few studies have been conducted into child marriages in conflict and humanitarian settings. Data on contraceptive use among newly married young girls who experienced child marriages are even scarcer. In a patriarchal society, child marriage marks the initiation of sexual activity at an age when girls’ bodies are still developing and when they know little about their sexual and reproductive health and rights. Although child marriages and associated pregnancies in humanitarian settings are gaining attention, little is known about these in the context of the displaced Rohingya people.

Added value of this study

This study provides an understanding of the context of child marriages and contraceptives use among married Rohingya girls who have experienced child marriages in the refugee camps in Bangladesh. The illegal status of the refugees may have exacerbated the circumstances around the practice of child marriage. Although a minimum legal age for marriage has been introduced in the camps, some parents circumvent this. Some factors that affect child marriage are unique to this setting, such as preferences for younger brides because of the view that beauty diminishes with age. Contraceptive use before they give birth to their first babies is rare. The involvement of female and male Rohingya volunteers for outreach services can be catalytic in promoting contraceptive use.

Implications of all the available evidence

Throughout the world, forcibly displaced populations grew substantially, from 43 million in 2009 to 71 million in 2018, when it reached a record high. Relatively high rates of child marriages and the limited use of contraceptive services among newly married girls are critical public health issues. Given that the practice of child marriage and the use of contraceptives in refugee settings are context-specific, it is essential to understand the factors that affect these before appropriate programmes can be designed. Child marriage is often considered to be a social issue, and inadequate legal frameworks and their enforcement are believed to be the main barriers to reducing the practice. Increasing the opportunities for girls to receive formal education is strongly recommended. Health services can be a crucial avenue for reaching this vulnerable subgroup and can play a critical role both in deterring child marriages and providing contraception services.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

Introduction

Child marriage is common in many parts of the world, and even with a global commitment to end this practice, such marriages are relatively prevalent in developing countries and among populations with low socioeconomic backgrounds.1,2 The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) defines “child marriage” as the formal union of an individual who is under the age of 18.3 Child marriage is a complex issue and often a harmful practice. Although both girls and boys are affected by the practice of child marriage, the prevalence is disproportionately high among girls; around 21% of girls throughout the world are married before their 18th birthdays compared to 4.5% of boys.4 In the literature, the effects that displacements and emergency situations have on child marriages are inconsistent and appear to vary across settings and contexts.5 As a result, there is evidence of both declines and increases in such marriages among young women in conflict-affected settings. Several factors have been identified as influencing this practice, including poverty, lack of education, social norms and the heightened insecurity faced by unmarried young girls.[6], [7], [8] Also, refugee crises are characterised by loss of livelihoods, decreased economic opportunities and overall uncertainty, all of which can contribute to the prevalence of child marriages.7,9

Child marriage is a violation of human rights, because it harms the health and development of children, most frequently girls, and denies their rights to decide on when and whom to marry.10 For many of them, it is too early in terms of their cognitive and emotional development, to assume the roles and responsibilities expected of them in married relationships. Marrying so young usually means the initiation of sexual activity at an age when girls know little about their bodies, their sexual and reproductive health, or the benefits of contraceptive use. Also, the sexual and reproductive health of these girls is likely to be threatened, since they are usually forced into sexual relationships with male spouses who are often considerably older than they are.11 Child brides generally lack the status and knowledge to negotiate for safe sex and reproductive rights, increasing their risks of pregnancies at early ages. Moreover, as girl child marriage is prevalent in families living in poverty and with poor nutrition, many of these girls are not physically ready to have safe pregnancies, and this puts them and their new-borns at substantial risk of adverse health.12 Indeed, child marriage is linked to high fertility, repeat childbirths in under 24 months, relatively low health-seeking behaviours13 and contraceptive use to delay the first pregnancy,14 complications during pregnancy, underweight babies and their stunted growth.15 In developing countries, complications from pregnancy and childbirth are the leading cause of death in young women aged 15 to 19.16 Worldwide, around 70,000 adolescent mothers die each year because they have children before they are physically ready for parenthood.17 Therefore, child brides are a group that could benefit more than any other from family planning services. However, data on contraceptive use among newly married young girls are scarce in conflict and humanitarian settings. Much of what we know is based on a few limited observations by field practitioners and researchers and grey literature.[18], [19], [20] Thus, to gain a better understanding of the context of girl child marriages, the barriers regarding access to contraceptive use and long-term plans, further research is needed in conflict areas and humanitarian settings.

From August to September 2017, Bangladesh allowed a sudden influx of 700,000 Rohingya refugees from the Rakhine state of Myanmar to cross the border and settle in its southern district of Cox's Bazar (Figure 1). Together with 200,000 who came during the previous waves of displacement, currently, almost one million Rohingya refugees live in temporary homes that are crowded into an area of only 13 square killometres. To our knowledge, currently, this is the world's largest refugee settlement in terms of both size and population density. These refugees were fleeing from ethnic cleansing in Myanmar, one that was recently declared to be genocide in a hearing at the International Court of Justice.21 Bangladesh identifies these refugees as “Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals,” a designation that denies their refugee status and related rights and puts them on precarious legal footing under domestic law.22 More than one quarter of these refugees are females of reproductive age.23 This displacement created a situation that is conducive to child marriage. For instance, Myanmar had a government restriction against child marriage, and permission was needed even for marriages among Rohingya men and women of mature ages.24 However, after they had been displaced to Bangladesh, the Rohingya people did not face such restrictions, particularly during the first year. Together with other facilitators, this relaxed situation may have made unmarried adolescent girls disproportionately vulnerable to child marriages. In addition, contraception use is a sensitive issue among these people because of their previous experiences of state-imposed measures of population control in Rakhine.25 However, little is known about the practice of child marriage in this largest settlement of displaced population. The data on contraceptive use among young women who experienced child marriages are even scarcer.5 This study aimed to examine the factors that influence child marriage and contraceptive use among Rohingya adolescent girls who have experienced child marriages.

Figure 1.

Location of Rakhine state and Cox's Bazar in the world map

Methods

Study setting, design and data collection

The study was conducted during the second week of November 2019 in the world's largest refugee setting, Kutupalong Refugee makeshift, which is spread in five square mile areas and divided into 34 camps comprising a total of 208 blocks. On average, each block has 892 households. These people are entirely dependent on humanitarian assistance. The World Food Programme assists by providing food to those in the camp and nutrition services to pregnant and nursing mothers and young children.26 Around 150 government, non-government and international organisations are involved in providing health, family planning and nutrition services through both static and mobile health facilities in areas of the camp, with a variety of service provisions and referral linkages to sub-district and district health complexes and hospitals run by the government.27 Almost all healthcare providers are Bangladeshi citizens.

The data for this study were collected from four randomly selected camps in the Kutupalong Registered Rohingya Refugee settlement. There were 19 blocks in these four camps from which eight blocks (2 blocks from each camp) were selected randomly for this study. We administered face-to-face quantitative surveys followed by qualitative interviews. We followed a cross-sectional design for the quantitative data and interviewed as many eligible women as possible within the eight blocks selected for this study. This study included quantitative data (n=96) of adolescent married girls who were sexually active during the previous two years. The first version of the quantitative questionnaire was developed by incorporating some relevant questions from the Demographic and Health Survey,28 which has been validated and is recognised worldwide. The adapted questionnaire was piloted among 15 Rohingya women to ensure its appropriateness. Inconsistencies identified were addressed.

The qualitative interviews were also administered face to face and potential participants were identified by a local Rohingya volunteer who lived in that settlement. Two qualitative interviewers then contacted the potential participants using a recruitment script and interviewed 18 adolescent Rohingya girls who were married (aged from 10 to 19 years). The interviewer endeavoured to ensure confidentiality by having one-on-one interviews either in participants’ houses or outside, without the presence of others. To ensure this, the interviewer had to make several visits to the shelters of some participants. We also interviewed nine service providers of reproductive healthcare services, to gain their perspectives regarding contraceptive use among the adolescent married girls living in the camps. For selecting service providers, we endeavoured to ensure representation from managerial, clinical and outreach levels. This group included two doctors, two counsellors, three family planning visitors and two health managers. The qualitative data were collected using semi-structured interview guides. We used a convenience sampling approach for selecting participants of qualitative interviews. The questions in the interview guides involved the following core topics: child marriage, contraceptive use and associated questions. The interview guides were discussed with the qualitative interviewers before the interviews. The Rohingya participants were also asked about the perceptions they had regarding the practices of child marriage and contraceptive use while they were in Myanmar, since the literature from other settings suggests that these practices in the refugees’ countries of origin and their displacement situations may still be drivers of the ages for marriage.29 The research team organised half a day of training for the interviewers. The qualitative interview guides gave the interviewers flexibility in asking relevant questions, based on the respondents’ answers and circumstances.

Six local female interviewers, who are fluent in Rohingya dialect, conducted the survey/interview with the Rohingya girls. Interviewers are Bangladeshi citizens from a nearby community. They had completed a university degree and had previous experience of interviewing Rohingya people for research studies. The research team interviewed service providers and managers, trained the interviewers and supervised the data collection. All participants were informed of the purpose of the study, the voluntary nature of participation and the anonymous use of the data. All participants provided informed consent before their interviews. No identifying information was collected in the interview or the audio-recordings, and all data were stored on password-protected computers. Ethical Approval for this survey was given by the Institute of Biological Science, Rajshahi University.

Data analysis

Using quantitative data, we computed frequency and mean to understand the demographic, age of first marriage, contraceptive use among Rohingya adolescent female participants. All qualitative interviews were audiotaped and transcribed into Bengali. They were reviewed and checked for accuracy and completeness. The first and second authors read the content several times while observing general patterns in respondents’ answers. Recurrent ideas were coded, and codes were sorted into categories and themes. We followed the open coding approach and revised the codebook continuously as we coded additional interviews. Themes were developed inductively, and the focus of the analysis was on the explicit meanings of the information provided by the participants. Manual coding was used for organizing, coding, and analysing data. Only those parts of Bengali transcriptions needed for quotes were translated to English. Hard copies of the interview transcripts were stored securely in a locked cabinet.

Role of the funding source

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. All authors had access to the raw data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit this paper for publication.

Results

Descriptive statistics of quantitative survey

At the time of the survey, girls' mean was 17.4 years and their husbands' mean was 21.7 years. On average, the adolescent female participants had been 15.7 years old when they first married, and 34% had been married before they turned 16. Over 80% had given birth during the two years before the survey or were pregnant at the time of the survey (Table 1). Almost 68% had received no formal education, and 56% reported that their husbands had no formal education. Of those married girls who received a formal education, only three percent went to a secondary school.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic characteristics of and contraceptive use among female Rohingya refugee adolescent girls who experienced child marriage (n = 96)

| Characteristics | Estimate |

| Girls’ age, mean (±SD) | 17.44 (±1.34) |

| Husbands’ age, mean (±SD) | 21.67 (±3.05) |

| Age at first marriage, mean (±SD) | 15.67 (±1.41) |

| Number of children ever born, mean (±SD) | 1.27 (±0.66) |

| Current or past pregnancy1 | |

| Gave birth to one or more child | 53.13 % |

| Currently pregnant | 35.42 % |

| Neither gave birth nor currently pregnant | 10.42 % |

| Unsure about current pregnancy status | 4.17 % |

| Girls’ education status | |

| Formal education1 | 32.29 % |

| No formal education | 67.71 % |

| Husbands’ education status | |

| Formal education2 | 43.75 % |

| No formal education | 56.25 % |

| Currently use contraception | |

| Yes | 34.37 % |

| No | 65.63 % |

| Decision maker of contraception use among those currently using any contraceptives | |

| Girls | 36.54 % |

| Husbands | 40.38 % |

| Both girls and husbands | 15.38 % |

| Others (e.g., parents-in-law) | 7.69 % |

| Family planning personnel's visit to girls’ homes in the three months preceding the survey | |

| Yes | 47.92 % |

| No | 52.08 % |

Note: 1 The total adds up to more than 100 as some girls who gave birth previously were pregnant or unsure of their pregnancy status at the time of the survey. 2 Received at least some education from formal educational institutions e.g., school, college.

A third (34%) of the girls said they were using contraceptives on the week the survey was conducted (Table 1): 60% used Depo injections, 37% took pills and 3% received implants (not shown in the table). For almost half of these girls who were using contraceptives at this time, it was their husbands or others (e.g., parents-in-law) who had made the decisions about contraceptive use. Almost half (48%) of the adolescent female respondents reported that family planning personnel had visited their homes, supplied contraceptives and/or discussed referrals for further assistance.

Demographic characteristics and contraceptive use among the participants of qualitative interviews

The average age of the 18 participants who attended the qualitative interviews was 17.9 years, and the average age at the time of their marriages was 16.5 years. Nine participants had given birth, and four were pregnant during the data collection. None of the participants had used contraceptives before giving birth to their first babies. Those who were not pregnant and also had not yet given birth to a child also not using contraceptives during the survey. Only two participants were using contraceptives after having given birth to their first babies: one of these girls had an implant, and the other was taking pills.

Identified themes related to child marriage

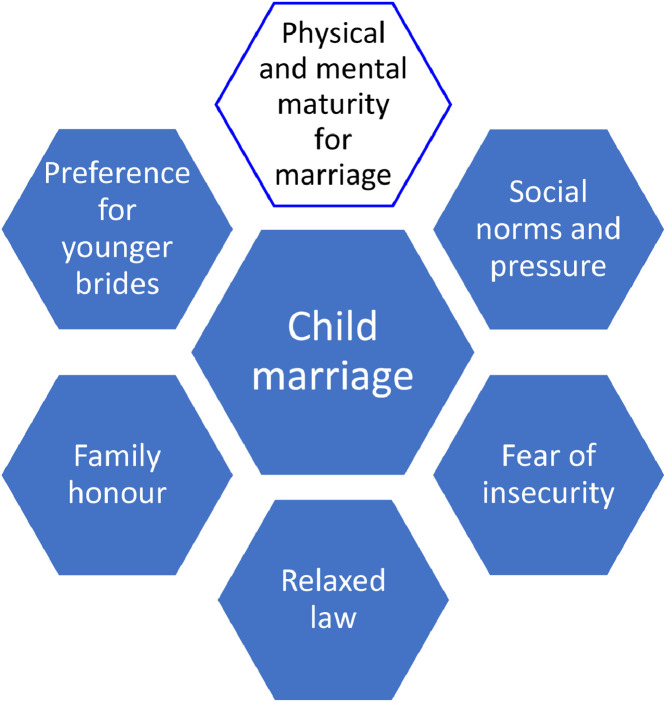

Seven themes on factors affecting child marriage emerged from interview data (Figure 2): physical and mental maturity for marriage, social norms and pressure, fear of insecurity, relaxed law, family honour and preference for younger brides.

Figure 2.

Factors influencing child marriage. All the factors except “physical and mental maturity for marriage” promote child marriage

Physical and mental maturity for marriage

Most participants considered 18 years to be the preferable minimum age for marriage among girls. Most of them mentioned the importance of physical and mental maturity in successfully navigating the difficulties of conjugal life. Some participants believed that there is a change in early marriage practice, although such change is slow. A participant said the following:

“It is better to get married between 18 and 20 years of age. Girls younger than 18 may not have the necessary temperaments to overcome the difficulties they face in their husbands’ family. Usually, girls of mature age [18 or more] hold patience, understand their vulnerabilities, the consequences of their actions. They will try to save their conjugal lives no matter what. I think, many people now understand that we [this generation] are different than the earlier generations. The generation of our parents/grandparents used to marry at the age of 10-12, which is rare now because most parents realise the risks of such marriages for our generation.” (P7, age 19)

However, it is unclear to what extent participants’ age at their first marriages impacted their abilities to handle day-to-day affairs in their in-laws’ homes. Here is a quote from a participant and how she responded to subsequent questions:

“I got married at the age of 16. My husband recently divorced me. He used to hurt me by using abusive words. His family wanted more for the dowry. In the camp, we barely survive with humanitarian aid. How can my family afford more for the dowry? I now live with my three-month old baby in a separate place from my parents but near their home”. (P2, age 17).

Interviewer: “Do you think you married at the right age?”

Respondent: “I don't think so. I think it would have been better to have waited a couple of years. Perhaps, I could then have handled things prudently in my husband's home”.

Interviewer: “Would you consider marrying in the future?”

Respondent: “Yes. It's not safe for women to stay single.”

Although most participants believe that 18 years of age is the preferable minimum age for marriage, none reported that their parents had delayed their marriages because of concerns about their maturity. One participant expressed this issue more as a government rule than a necessity. Here is one response from that participant about her age at marriage:

“In Myanmar, you cannot marry until you are 18. It's the same here now. But if Allah [God] desires you to marry earlier, you won't be able to wait until 18. I think that's what happened in my marriage.” (P11, age 18)

Social norms and pressure

Social pressure caused by perceptions of how others think and act influences behaviour. For instance, in a family with two or more girls who are close in age and have reached puberty, the parents may feel pressure to marrying off without further delay. A quote from one participant illustrates this:

“We are two siblings; I am 17, and my sister is 15 and a half. When there are two or more daughters who are close in age, the elder girl appears much older than she really is. My father was growing old. People suggested he marry me off without further delay. So, I was married at age 16.” (P1, age 17)

Religious belief is an important element of social conformity. Many Rohingya people believe that a girl becomes eligible for marriage once she experiences menarche and consider it a religious duty to marry her off without delay. Here is a quote from a service provider:

“In the Rohingya community, girls are considered eligible for marriage as soon as they have their first menstruation. For boys, the eligible age is generally 20 or more, although the ability of boys to earn money is increasingly being considered an essential criterion.”

Fear of insecurity

Fear of insecurity and associated uncertainties prompt many parents to consider early marriages for their daughters. Islam prohibits sex outside marriage and abortion. Sexual exposure prior to marriage may make it almost impossible for a girl to find a suitable husband. If a young female is involved in an affair or is exposed to premarital sex, parents have no choice but to favour an immediate marriage, even if she is under-aged. Below is a quote from a Rohingya girl:

“I got married last year. But before my parents gave consent to the proposal, they had considered many things, including sudden relocation to a foreign country where we do not have relatives around us. Marriageable girls are prone to sexual exposure, and this is a constant fear. My parents also feared that a marriage proposal as good as mine might not come again.” (P4, age 17)

Insecurities could be both perceived and actual. Here is a quote from a participant who experienced a forced marriage that was prompted mainly by insecurity:

“I was married when I was 13 and a half. My ex-husband forced me to marry him. I did not have a male member in our family. He used that as an opportunity and intimidated me. I went to seek help from our camp-majhee (a leader of sections of the camps), who realising the constant insecurity I was going through organised my marriage with my ex-husband. This happened during the first few months after we had arrived in Bangladesh. [Possibly] my husband used to obey that majhee. My husband divorced me after he (the majhee) had died.” (P15, age 15)

Relaxed law

Obtaining permission from the camp-in-charge office to get married was not initially needed. This requirement was recently introduced, mainly to enforce the minimum age for marriage. However, there are ways to circumvent this. Below is a quote from a Rohingya girl:

“We now need permission from the CIC (camp-in-charge). Some girls receive permission after using fake identification indicating that they are older than they are. Some parents only get permission after their daughters have already married.” (P6, age 19)

Another participant stated:

“Our parents decided to accomplish our marriage here in the camps. They feared that if we get back to Myanmar, we will not be able to marry until I reach 18.” (P10, age 16)

Some girls reported that although child marriage was strictly prohibited in Rakhine State, Myanmar, there were ways to circumvent this rule by bribing local government officials and leaders. However, in Bangladesh they had never heard of needing money to obtain permission to marry before 18 years of age. One girl reported that her marriage had been somewhat delayed due to her displacement from Myanmar. Here is what she stated:

“I would have married back in 2017 (at the age of 17) if we had still been in Rakhine, Myanmar. I was about to marry but then suddenly things were getting worse when the violence had started. I got married nine months later, in 2018, after we had moved here to Bangladesh.” (P16, age 19)

Family honour

Fears of elopement also prompt parents to consider early marriages for their daughters. If a girl runs away with a boy, this is often considered a disgrace that tarnishes family honour. There were several incidents of girls running away with their boyfriends rather than waiting for parents to find eligible bachelors. Hence, to avoid this risk, some parents prefer to marry their daughters off before they turn 18. Below is a quote from a Rohingya girl:

“My husband and I had an affair before we got married. My parents were unhappy with this because my husband's family did not approve of our relationship. My parents were looking for a suitable groom for me, as people had started talking about our affair. One day, we left our homes and got married without involving our families. We are now living with my parents. We hope that, one day, my husband's family will accept us and I will leave my parental home on that day.” (P8, age 18)

Preference for younger brides

It is easier to find a groom for a young girl, and grooms’ families usually prefer younger brides. The participants believed that young girls are beautiful, and that beauty diminishes with age. Relatively young (and beautiful) girls are likely to receive several marriage proposals. Although most people are aware of the legal age of marriage, when parents or other relatives of brides and grooms agree to a wedding, they prefer organising the ritual immediately. There is a deep-rooted creed that there should not be any delay in such a sacred event. Some parents believe there is little or no difference between the ages of 17 and 18. A decision like this may also be influenced by the insecurity that unmarried girls face. The following comments illustrate these observations:

“It is easier for a relatively young girl to find a suitable groom, because younger-aged girls look pretty. Beauty diminishes with age and so, then, does eligibility for marriage.” (P1, age 17)

"I had married when I was 17. My parents-in-law met me when I visited my sister's house. Then they sent a marriage proposal and kept pursuing [the issue with] my sister to convince [my family to accept]. Since they were very willing, my parents finally gave their consent. Once both parties agreed, everybody thought it would be unwise to delay the wedding just because I was a few months less than 18." (P12, age 18)

Identified themes related to contraceptive use

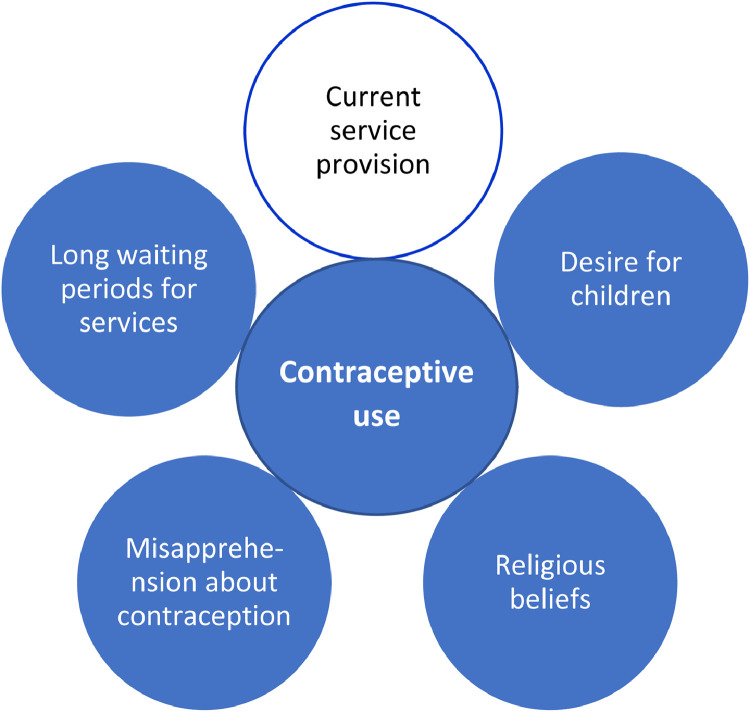

Five themes relating to the factors affecting contraceptive use emerged from the interview data (Figure 3): the desire for children, religious beliefs, misapprehension about contraception, long waiting periods in reproductive health services and current service provision.

Figure 3.

Factors influencing contraceptive use. All the factors except “current service provision” demote contraceptive use.

The desire for children

Contraceptive use is generally limited in the Rohingya community and even more so among married women before they have had their first babies. Some participants, particularly those who had already had a baby, said they contemplated starting contraceptive use as a method of spacing births, particularly those who gave birth to their first baby. Below is a statement by a participant that illustrates this:

“I became pregnant just two months after my wedding. I did not use contraception because my husband and parents-in-law wanted a baby. My baby is now three months old. I have been thinking about commencing a suitable birth-control method. XX apa [an outreach worker] always encourages me about this. I have thought about going to the healthcare centre for this, but I haven't yet been able to make it there.” (P5, age 17).

Some participants identified the importance of having a child for securing their conjugal lives. The following statement demonstrates this sentiment:

“My first baby died a few days after his birth. I did not use any contraceptives, as I wanted to have a baby. Allah [God] willing, I am pregnant now. I believe having a child brings security in conjugal life and my husband will take care of me more once we have a baby. You know, nobody takes care of a tree that doesn't provide fruit.” (P14, age 19)

However, there seems to be an understanding among some girls that birth control measures are helpful after giving birth to the first baby. For instance, one participant stated:

“Why should I use protection now? I may use protection after the birth of my first baby, to have some time before I get pregnant for the second time.” (P10, age 16)

Religious beliefs

Religious beliefs are a common factor affecting contraceptive use. Some participants believe that birth control practice will make the Almighty unhappy with them. Here is a quote from a participant:

“We believe that if people intentionally do something not to give birth to a baby, it's similar to murder and it's a big sin. My husband and I believe in Allah [God]. We don't agree with birth control practice.” (P14, age 19)

Service providers identified several barriers to contraceptive use, including religious beliefs and vetoes of partners and/or other relatives. Often such vetoes are also rooted in religious beliefs. As a female outreach worker said:

"The Rohingya people believe that babies are a gift from Allah [God] for their parents.”

Misapprehension about contraception

Fears about the side effects of contraceptives discourage some women from using them. Below is a quote from an outreach service provider working in a nongovernmental organisation (NGO):

“Some women fear that contraceptive use may harm fertility and that if a woman prevents her first baby she may not be able to give birth after that. Thus, even if they are 16 or 17 years old, they do not want to use contraception. In most cases, husbands or parents-in-law disapprove of contraceptive use. While we can sometimes motivate mothers-in-law, I believe that male outreach workers will be more effective in motivating husbands and fathers-in-law.”

Rumours about contraception are often spread by word of mouth. While in Rakhine, many of these people used to believe that the underlying reason for promoting contraception was to reduce the size of the Rohingya population. However, no participants (neither providers nor girls) reported any such distrust about contraception promotion efforts in Bangladesh.

Difficulties in accessing facility-based reproductive health services

Inadequate accessibility to facility-based reproductive healthcare services was identified as a barrier to contraceptive use. Here are two quotes from girls:

“In healthcare centres, sometimes half a day passes by as I stand in a long queue before finally seeing a doctor. My baby cries for food, and I can't give him breast milk standing in a queue. In the hot and humid weather, how long can one keep waiting in a queue? There is no priority for mothers with babies.” (P6, age 19)

“Most of the health facilities are far away from my home. This is a hilly area and every time I need to get to a health centre I need to descend and climb a medium-sized hill. Also, transports are unavailable in some roads and I need to walk a long way.” (P7, age 19)

Other barriers include unwelcoming behaviours from the providers, neglect and costs (if accessing services in private clinics located in cities). Often such experiences constitute the overall perceptions of the facility-based healthcare services, both for contraception and other types of services.

Current service provision

Most programme personnel reported some positive results with the current service provision, indicating that they were reaching women of reproductive age and offering them contraception. Although not all outreach workers supply contraception, they do offer counselling and refer eligible women to nearby healthcare facilities. Here are some quotes from a physician working in an NGO:

"In the beginning, there was little demand for contraception. However, with our ongoing efforts, contraceptive use among the Rohingya women has increased. Some women now realise the benefits of birth spacing and the adverse health outcome of teenage pregnancies. Although we have a long way to go, I am happy with the progress we have made.”

“We counsel them, providing explanations that are consistent with their religious beliefs. One explanation, for instance, is that the religion of Islam also suggests that parents take care of their children properly, and that parents cannot ensure such care if they have too many babies without enough space between their births.”

Those who have already given birth to one or more babies may show some interest in contraceptive use if they receive counselling. A family planning outreach worker gave the following as an example of how she convinces women to use contraceptives:

“If I see [that] five/six people are living in a small makeshift house, I sometimes use this congested living condition as a point to convince them. I ask them how they will live in such a small house if they have more babies and then I counsel them to consider using contraceptives.”

When this outreach worker was asked the reasons why some women say that they have never seen a health worker visiting them, she responded with the following:

“I try to ensure complete coverage of all women of reproductive age in my blocks. It may be the case that in the other blocks, outreach workers cannot reach everybody.”

Discussion

The findings of this study provide a useful understanding of the context of child marriages and contraceptive use among married Rohingya girls in the refugee camps in Bangladesh. Community norms in the country of origin with regard to girls’ ages when they are married and their use of contraceptives may have influenced many of the factors that have been identified. Although in Rakhine State, in Myanmar, the Rohingya population had been subject to laws prohibiting early marriage and restricting the number of children they could have, previous data suggest that the practice of child marriage is deep-rooted within the Rohingya society. For instance, parents who could afford to bribe government officials would change their daughters’ dates of birth on official documents, which would allow them to marry.20 Our qualitative data suggest that, with changed circumstances and in the absence of legal procedures, there were little or no restrictions on child marriages in the camps. Although we are unable to state precisely whether this situation has increased the prevalence of child marriage, having a less restrictive situation along with other facilitators and also having only a few barriers in the camps may have increased the incidence of child marriages.19

In Muslim communities, sexual relationships outside of marriage are considered to be a religious taboo. This, together with existing social and legal circumstances, makes it difficult to stop child marriages completely. Although permission from the camp-in-charge office is now needed for marriage, those without birth registrations and age documentation may be able to circumvent the requirements. Increasing the opportunities for girls to have education is an effective strategy that has been recognised for reducing child marriage.30 Although there is currently a limited opportunity for education, in early 2020 the government of Bangladesh granted permission to young Rohingya refugees for formal schooling.31 The literature suggests that financial incentives to remain in school and life-skills curricula may help to reduce child marriages.32

In the literature, a range of factors was identified as influencing and facilitating child marriages in refugee settings.6,20,33 While many of these are consistent with our findings, some are not, such as food rations which are distributed by households (often marriages entail the creation of new households), reduced burdens on limited resources (as married girls usually live with their husbands’ families)18 and smaller dowries for younger girls.34 No participant in our study identified any of these three factors. Also, it remains unclear whether the limited abilities of parents to offer dowries have any impact on the practice of child marriages. It also remains unknown whether child marriage in the camps is influenced by a relatively high prevalence of this practice in the host country, Bangladesh.35 Further study is needed for a comprehensive assessment of the underlying factors facilitating child marriage in the camps. Also, research into identifying effective programmes to prevent and reduce its negative consequences among girls who have experienced child marriage in a context of conflict and displacement is critical.

Our results suggest that many of these girls are under pressure to become pregnant soon after their marriages and to have babies even when they are still children themselves, with only limited knowledge of sex and reproductive health.25 This causes almost complete avoidance of contraceptive use among married women before giving birth to the first baby. This finding is consistent with previous literature.36 Therefore, efforts both to promote contraceptive use for birth spacing and counsel newly married females should be strengthened and expanded. Family planning and contraceptive use are sensitive subjects for persecuted Rohingya communities, as these people were subjected to a “Population Control” bill that they believe the Myanmar government had introduced for reducing the Rohingya population.24 Thus, healthcare providers should also take measures to dispel negative rumours about contraception. Besides, our data suggest that husbands do not generally use contraception, and that most programmes operate from the premise that women are the ones to use contraceptives. This must be changed, and we recommend involving male outreach workers to promote contraceptive use among men.

Since most Rohingya women stay inside their homes, maintaining purdah (preventing women from being seen by men who are strangers), and because movements in the camps are limited, outreach services are crucial for being able to reach them. Such services could be more acceptable to the users if Rohingya refugee volunteers are involved. Although some outreach services exist in the camps and play critical roles in increasing contraceptive use, many of our participants had never seen an outreach worker. Perhaps this highlights the necessity to have effective coordination to ensure minimum services for all women and to avoid duplication. Finally, as not all contraceptive methods can be provided by outreach workers, the long waiting periods in healthcare facilities37 must be reduced.

Our study has several limitations. Some girls, out of fear or shame, may not have disclosed their true ages at marriage. In addition, the quantitative data came from a cross-sectional survey. Although we randomly selected four camps and eight blocks, the participants were not randomly selected. Consequently, the findings may not be fully representative of the target group. Another limitation is that we used multiple languages. The questionnaire was developed in Bengali, data collection was conducted verbally in the Rohingya language and recordings of qualitative interviews were later transcribed and analysed in Bengali. The findings were translated back into English to write this paper. This may all have contributed to nuances that were missed and meanings lost in questions, responses and interpretations of findings. We tried to minimise this limitation by engaging experienced data collectors and transcribers.

Finally, our results suggest that girl-child marriages are common in Rohingya camps. Perceptions regarding the physical and mental maturity for marriage, social norms, insecurity, family honour, preferences for younger brides and relaxed enforcement of the minimum legal age of marriage are the main factors that influence child marriages. Increasing the opportunities for girls to receive education may help to reduce this practice. The desire to have children, religious beliefs, misapprehension about contraception and long waiting periods in reproductive health and current service provision were the main factors influencing contraceptive use. Although contraceptive use is gradually increasing, it remains rare among newly married girls before they give birth to their first babies. The counselling and contraception services offered by the outreach health and family planning workers should be expanded. The involvement of both female and male Rohingya volunteers in outreach services could promote contraceptive use.

Contributors

MMI and MNK designed the study. MMI analysed the data and wrote the first draft of the article. MMR and MNK supervised the data collection. MMI and MNK verified the underlying data. All authors edited and approved the final version of the Article.

Data sharing statement

De-identified data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding authors upon reasonable request following the publication of this article. Approval may be required from the Office of the Refugee Relief & Repatriation Commissioner, Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh.

Editor note: The Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All other authors declare no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

This study received a research grant from La Trobe Asia.

Footnotes

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100175.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.WHO . 2020. Child marriages: 39 000 every day. Available at: https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2013/child_marriage_20130307/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huda MM, O'Flaherty M, Finlay JE, Al Mamun A. Time trends and sociodemographic inequalities in the prevalence of adolescent motherhood in 74 low-income and middle-income countries: a population-based study. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30311-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.UNICEF . 2020. Child marriage. Available at: https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-protection/child-marriage/ [Google Scholar]

- 4.UNICEF . 2021. Child marriage among boys: A global overview of available data.https://data.unicef.org/resources/child-marriage-among-boys-available-data/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Neal S, Stone N, Ingham R. The impact of armed conflict on adolescent transitions: a systematic review of quantitative research on age of sexual debut, first marriage and first birth in young women under the age of 20 years. BMC Public Health. 2016;16:225. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-2868-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kohno A, Techasrivichien T, Suguimoto SP, Dahlui M, Nik Farid ND, Nakayama T. Investigation of the key factors that influence the girls to enter into child marriage: A meta-synthesis of qualitative evidence. PLoS One. 2020;15(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0235959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.2018. Girls not brides: The Global Partnership to End Child Marriage. Child marriage in humanitarian settings. Available at: https://www.girlsnotbrides.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Child-marriage-in-humanitarian-settings.pdf. London. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stark L, Seff I, Reis C. Gender-based violence against adolescent girls in humanitarian settings: a review of the evidence. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(20)30245-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mourtada R, Schlecht J, DeJong J. A qualitative study exploring child marriage practices among Syrian conflict-affected populations in Lebanon. Confl Health. 2017;11(Suppl 1):27. doi: 10.1186/s13031-017-0131-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.United Nations . Assembly UG; New York: 1964. Convention on Consent to Marriage, Minimum Age for Marriage and Registration of Marriages. [Google Scholar]

- 11.International Women's Health Coalition . 2020. The Facts on Child Marriage. Available at: https://iwhc.org/resources/facts-child-marriage/ [Google Scholar]

- 12.Parsons Jennifer, Edmeades Jeffrey, Kes Aslihan, Petroni Suzanne, Sexton Maggie, Wodon Q. Economic Impacts of Child Marriage: A Review of the Literature. The Review of Faith & International Affairs. 2015;13(3):12–22. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sekine K, Carter DJ. The effect of child marriage on the utilization of maternal health care in Nepal: A cross-sectional analysis of Demographic and Health Survey 2016. PLoS One. 2019;14(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raj A, Saggurti N, Balaiah D, Silverman JG. Prevalence of child marriage and its effect on fertility and fertility-control outcomes of young women in India: a cross-sectional, observational study. Lancet. 2009;373(9678):1883–1889. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(09)60246-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Paul P, Chouhan P, Zaveri A. Impact of child marriage on nutritional status and anaemia of children under 5 years of age: empirical evidence from India. Public Health. 2019;177:95–101. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.WHO . 2020. Adolescent pregnancy. Available at: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-pregnancy. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mayor S. Pregnancy and childbirth are leading causes of death in teenage girls in developing countries. BMJ. 2004;328(7449):1152. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7449.1152-a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mazurana D, Marshak A, Spears K. Child marriage in armed conflict. International Review of the Red Cross. 2019;101(911):575–601. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ainul Sigma, Ehsan Iqbal, Haque Eashita F. The Population Council; Dhaka, Bangladesh: 2018. Marriage and sexual and reproductive health of rohingya adolescents and youth in bangladesh: A qualitative study. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Al Mamun MA, Bailey N, Koreshi MA, Rahman F. BBC Media Action; London, UK: 2018. Violence against women within the rohingya community: Prevalence, reasons and implications for communication. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lancet The. The Rohingya people: past, present, and future. Lancet. 2020;394(10216):2202. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33139-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Human Rights Watch . United States of America; 2018. Bangladesh Is Not My Country” The Plight of Rohingya Refugees from Myanmar. Available at: https://www.hrw.org/report/2018/08/06/bangladesh-not-my-country/plight-rohingya-refugees-myanmar; Accessed on 6 July 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ahmed R, Farnaz N, Aktar B. Situation analysis for delivering integrated comprehensive sexual and reproductive health services in humanitarian crisis condition for Rohingya refugees in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh: protocol for a mixed-method study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(7) doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.UNHCR . 2018. Independent evaluation of UNHCR's emergency response to the Rohingya refugees influx in Bangladesh August 2017 – September 2018. Geneva. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ripoll S, Iqbal I, Farzana KF. Social and cultural factors shaping heath and nutrition, wellbeing and protection of the Rohingya within the humanitarian context. Soc Sci Humanit Action. 2017:1–34. [Google Scholar]

- 26.World Food Programme . 2021. WFP in Cox's Bazar Information Booklet. Available at: https://www.wfp.org/countries/bangladesh. Dhaka, Bangladesh. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Inter-sector Coordination Group. Rohingya Crisis in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh: Health Sector Bulletin Number 4. Bangladesh: Health Sector Coordination Team, World Health Organization, 2018.

- 28.National Institute of Population Research and Training - NIPORT . 2020. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, ICF. Bangladesh Demographic and Health Survey 2017-18. Dhaka, Bangladesh: NIPORT/ICF.https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR344/FR344.pdf Available at. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sieverding M, Krafft C, Berri N, Keo C. Persistence and Change in Marriage Practices among Syrian Refugees in Jordan. Stud Fam Plann. 2020;51(3):225–249. doi: 10.1111/sifp.12134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wodon QT, Male C, Montenegro CE, Nguyen H, Onagoruwa AO. Educating Girls and Ending Child Marriage: A Priority for Africa. The Cost of Not Educating Girls Notes Series. 2018 https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/268251542653259451/educating-girls-and-ending-child-marriage-a-priority-for-africa [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahmed K. 2020. Bangladesh grants Rohingya refugee children access to education The Guardian. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kalamar AM, Lee-Rife S, Hindin MJ. Interventions to Prevent Child Marriage Among Young People in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Systematic Review of the Published and Gray Literature. J Adolesc Health. 2016;59(3 Suppl):S16–S21. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Melnikas AJ, Ainul S, Ehsan I, Haque E, Amin S. Child marriage practices among the Rohingya in Bangladesh. Confl Health. 2020;14:28. doi: 10.1186/s13031-020-00274-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Innovations for Poverty Action (IPA) 2018. UNICEF. Current Level of Knowledge, Attitudes, Practices, and Behaviours (KAPB) of the Rohingya Refugees and Host Community in Cox's Bazar. A Report on Findings from the Baseline Survey. Dhaka, Bangladesh. [Google Scholar]

- 35.WHO . 2020. Child marriages: 39 000 every day. https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2013/child_marriage_20130307/en/ (accessed 22 December 2020) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Godha D, Hotchkiss DR, Gage AJ. Association between child marriage and reproductive health outcomes and service utilization: a multi-country study from South Asia. J Adolesc Health. 2013;52(5):552–558. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2013.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chowdhury MAK, Billah SM, Karim F, Khan ANS, Islam S, Arifeen SE. ICDDR'B and UNFPA; 2018. Demographic Profiling and Needs Assessment of Maternal and Child Health (MCH) Care for the Rohingya Refugee Population in Cox's Bazar, Bangladesh. Dhaka, Bangladesh. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.