Abstract

Background

The discipline of anaesthesiology in China has undergone historical changes and development during the past century. However, nationwide comprehensive data on the current status of each hospital department providing anaesthesia care has been lacking since the discipline was first established in China. This information is essential for effective regulation of healthcare policies by both the professional associations and the government health ministry. Therefore, a nationwide survey was set up in 2018 to investigate the current status of Chinese anaesthesiology. This paper reports the findings of the survey.

Methods

We performed a cross-sectional nationwide census survey of the current status of each hospital department providing anaesthesia care in 31 provinces across the Chinese mainland. The content of the survey included general information of the department, the hospital level and scale, the volume of the anaesthesiology department, the characteristics of anaesthesiologists, and the caseload of the anaesthesiology departments. Face-to-face interviews were performed by trained interviewers. The Chinese Anaesthesiology Department Tracking Database (CADTD) was established during the survey. Data quality control was undertaken by the investigation committee throughout the survey process.

Findings

The nationwide census survey was completed by 11,432 hospital departments providing anaesthesia care throughout mainland China from June 1, 2018 to June 30, 2019. Among the 11,432 departments, 4591 (40•16%) belonged to specialised hospitals, while 6841 (59•84%) were affiliated to general hospitals. The proportion of independent anaesthesiology departments was 45•15% in mainland China. There was a total of 92,726 anaesthesiologists, or 6•7 per 100,000 of the population. Regions with better economic conditions had more anaesthesiologists per 100,000 of the population. From 2015 to 2017, the workload of anaesthesiologists has increased by 10%.

Interpretation

The discipline of anaesthesiology in China has entered a rapid development phase. However, the current status of anaesthesiology is not well defined, which makes it difficult to meet the needs of the increasing Chinese healthcare demand. The evidence from this survey offers valuable information for policy makers and anaesthesiology associations to monitor the development of the discipline and regulate healthcare policies effectively.

Funding

National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grant No. 2018YFC2001900).

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

The discipline of anaesthesiology in China has experienced rapid development in the past century as the economy has grown. However, for a long time, the nation's standardised reporting system for the current status of each region's anaesthesiology was lacking, and the status of anaesthesiology has never been comprehensively investigated nationwide since the formal establishment of the discipline in China in the 1950s. As a result, national investigative evidence was seldom available whenever there was a need to make policy relevant to anaesthesiology, which hindered the development of Chinese anaesthesiology to a certain degree. Therefore, a nationwide survey was set up in 2018 to investigate the current status of Chinese anaesthesiology.

Added value of this study

This was the first general survey of all hospital anaesthesia departments in the Chinese mainland. The Chinese Anaesthesiology Department Tracking Database (CADTD) was established. A full picture of the current status of Chinese anaesthesiology was surveyed, including general information of the department, the hospital level and scale, the volume of the anaesthesiology department, the characteristics of anaesthesiologists, and the caseload of the anaesthesiology department. The study summarised the constructional achievements of Chinese anaesthesiology, and revealed existing problems under current conditions. The specialty of anaesthesiology is very large in scale, fast developing with a heavy case load increasing year-by-year. However, the percentage of independent anaesthesiology departments among all hospital departments providing anaesthesia care is less than half, and the anaesthesiology workforce is limited, with improper configuration. The development of Chinese anaesthesiology will be a long and painstaking process in the near future. The continuous update of the CADTD will provide important evidence for policy makers and professional associations to effectively regulate healthcare policies, especially regarding anaesthesiology and surgery.

Implications of all the available evidence

As can be concluded from the survey results, the rapid development of Chinese anaesthesiology is unique to this particular part of the world, but problems such as imbalanced development among regions, heavy workloads, and large gaps in departmental construction are still common. More preferential policies should be offered for the standardised and healthy development of anaesthesiology in China. Successful implementation of the general survey for the discipline in China not only provides a benchmark for monitoring the development of Chinese anaesthesiology, but also accumulates valuable experience for future surveys and offers useful reference data for other medical disciplines around the world.

Alt-text: Unlabelled box

1. Introduction

China has made remarkable progress in its economic development in the past four decades. At the same time, the healthcare system in China, which provides clinical care and public health services to one-fifth of the world's population, has also advanced significantly. The healthcare access quality index (HAQ index) of China has increased dramatically from 42•6 in 1990 to 53•5 in 2000 and 77•9 in 2016, and China has become one of the countries with the most significant improvement in medical care quality [1]. In addition, according to annual statistics released by the National Bureau of Statistics, the total number of surgeries performed in China in 2017 was 55•96 million, with an annual increase of 10•1% [2], but the annual number of hospitalisations was more than 10 times that in the 1980s [3]. The substantial increase of healthcare quality and rapid increase in the number of surgeries epitomise the fast-paced development of modern medicine in China during the past decades. Simultaneously, the discipline of anaesthesiology in China has exhibited drastic changes and progressive growth, transforming from traditional Chinese medicine anaesthesia to modern anaesthesia [4]. This historical change and development reflect the development of anaesthesiology in China, which is different to that in the Western world.

With the increasing demand of the Chinese population for healthcare services and the rapid growth in the number of surgeries, anaesthesiology departments in China are facing enormous challenges [5]. In addition, the shortage of anaesthesiologists and their high burnout rate has hindered development of the discipline [6]. Moreover, the contradiction between the uneven development of Chinese anaesthesiology and the growing demand of Chinese citizens for healthcare services is becoming increasingly significant, which makes greater action at policy and hospital level urgently necessary.

To gain a better general understanding Chinese anaesthesiology and gather more information for accelerating the development of the discipline, a cross-sectional nationwide survey was designed and completed by the Chinese Association of Anaesthesiologists (CAA), the Chinese Society of Anaesthesiologists (CSA), the Chinese Society of Integrative Anaesthesiology (CSIA), and the National Centre for Anaesthesia Medical Quality and Quality Control. This was the first general survey of all anaesthesia departments in Chinese mainland hospitals since the establishment of anaesthesiology in China. The aim of the survey was to obtain information about the current situation of anaesthesiology in China and compare this with other countries. Information collected in the study included the independent establishment of anaesthesiology and its influencing factors, the proportion and geographical distribution of anaesthesiologist human resources, the annual workload of anaesthesiologists, and the correlation between the proportion of anaesthesiologists and health economic indicators.

2. Methods

The nationwide survey was conducted between June 1, 2018 and June 30, 2019. All institutions providing anaesthesia care in mainland China were included and potential respondents were the department chiefs or other designated persons (usually the administrative secretaries) in anaesthesia departments.

2.1. Data source and study sample

At the request of the Chinese Association of Anaesthesiologists (CAA), Chinese Society of Anaesthesiologists (CSA), Chinese Society of Integrative Anaesthesiology (CSIA) and the National Centre for Anaesthesia Medical Quality and Quality Control, a national survey collaboration network that included 31 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions in mainland China was built for this study. With the help of local governments and health commissions, we identified 11,432 hospital anaesthesia departments; members of the CAA provincial branch were recruited to ensure the accessibility and feasibility of the survey. The Chinese Anaesthesiology Department Tracking Database (CADTD) was established from this cross-sectional nationwide survey.

2.2. Questionnaire design

The design of the questionnaire was mainly based on a previous human resources survey conducted by the CSA in 2015 [7]. The questionnaire was designed to be completed by the anaesthesiology department chief or a designated person at every hospital. The questionnaire was divided into seven parts and comprised 26 items in total. In order to get the entire questionnaire filled in, all the questions were designated as compulsory questions. The validity and reliability of the survey questionnaire was assessed and approved by experts of the CAA and statisticians who were not eligible to be surveyed.

-

•

Part 1 of the survey focused on general information about the anaesthesiology department chiefs, which included their age, gender, anaesthesia service duration, ranking, educational background, and work phone.

-

•

Part 2 collected information on the hospital level, including the name of the hospital and the department providing anaesthesia care, its location, and the scale of the hospital.

-

•

Part 3 focused on the volume of the hospitals, which included the total number of beds and beds in surgical departments, and the number of surgeons in the hospital with the ranking of attending or above.

-

•

Part 4 focused on the volume of the anaesthesiology department, including the number of operating rooms (OR), number of beds in post-anaesthesia care units, number of outpatient clinics, and the number of beds in intensive care units (ICUs) and pain wards under the supervision of the anaesthesiology department.

-

•

Part 5 collected information on rankings, educational background, and the specialties of both anaesthesiologists and nurses.

-

•

Part 6 collected the annual caseload of the anaesthesiology department from 2015 to 2017, including the number of anaesthesia cases inside and outside the OR, outpatient clinic numbers, the number of patients admitted to the ICU and pain ward under the supervision of the anaesthesiology department, and the number of patients undergoing therapeutic procedures in the pain ward.

The questionnaire was built electronically on the Wenjuanxing platform (https://www.wjx.cn) with a unique URL.

2.3. Investigative procedures

The investigative procedures were determined by experts of the CAA and statisticians prior to the survey. In order to maximize the accuracy of this national survey, quality control was performed at each process of the survey, including establishment of an investigation committee, questionnaire design, data acquisition, and data analysis. The investigators were responsible for the follow-up, obtaining written consent, conducting the questionnaire survey, and cooperating with data specialists in assessing and controlling quality.

The logicality and rationality of the uploaded data were assessed by data specialists in each province. If unqualified questionnaire results were found by data specialist, the questionnaire would be sent back to the corresponding hospital for re-investigation and data acquisition. The statistician was responsible for the maintenance of the database, and the interpretation and analysis of data (see Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Investigative procedures profile. Stage one, initiation and design of the questionnaire was undertaken by the Chinese PLAGH; Stage two investigations were performed by qualified investigators; Stage three, the logicality and rationality of the uploaded data were assessed by the data specialists in each province; Stage four, the maintenance interpretation and analysis of data were performed by statisticians and epidemiologists. Chinese PLAGH = Chinese People's Liberation Army General Hospital; CAA = Chinese Association of Anaesthesiologists; CSA = Chinese Society of Anaesthesiologists; CSIA = Chinese Society of Integrative Anaesthesiology.

2.4. Questionnaire investigations

A total of 1,548 investigators from 31 provinces, municipalities and autonomous regions from mainland China were trained for 8 hours online before the start of the investigation to clarify the contents of the questionnaire and improve investigation skills. In addition, all investigators had to pass an examination prior to conducting the survey.

Investigators visited all qualified anaesthesia departments. To reduce possible biases and increase the response rate, and avoid the possible bias and low response rate of a non-mandatory questionnaire survey, the questionnaire was conducted by way of a face-to-face interview with the chief or a designated person of the departments.

The purpose, significance, and main contents of the survey were explained, and written consent was obtained from the department chief prior to the investigation. Data entry was performed by the investigator synchronously. A verification system, including checking in the field by the interviewers themselves and checking in the work group by supervisors, was applied during the survey. If mistakes were found by data specialists, the data were sent back to investigators for checking and refilling. Final data quality control was undertaken by the investigation committee throughout the survey process, including a logic check, sequential recording check, phone-call check, and a re-interview check.

2.5. Definitions and explanations

2.5.1. The classification of Chinese hospitals

In China, public hospitals are classified into 3 tiers, i.e., tiers 1, 2 and 3 [8]. Each tier is further classified into three subsidiary levels based on the score assessed by the regional health commission, i.e., Jia (A), Yi (B), or Bing (C). The higher the tier, the better the hospital. For the subsidiary levels, A is better than B, while B is better than C. For example, tier 3A hospitals are top level hospitals in China, which are usually general hospitals in a city with a bed capacity exceeding 500. Tier 1C hospital are usually hospitals in rural areas or community hospitals. However, if the bed capacity of the hospital just exceeds 500 but it has not yet been scored, the classification of the hospital would be regarded as ‘tier 3 other’.

2.5.2. History of the development of Chinese anaesthesiology

Chinese anaesthesiology care services began relatively late. In the 1980s, some anaesthesiologists were nurses rather than doctors due to a lack of doctors and specific medical education. It was not until 1989 that the Ministry of Health at the time announced that anaesthesiology departments were to be changed from medical technical departments to clinical departments [4]. Therefore, Chinese anaesthesiology departments had diverse affiliation relationships, and they could be administered by the hospital, surgical departments (such as departments of obstetrics and gynaecology), or operating rooms.

2.5.3. Physician ranking systems in China

The ranking of physicians in China includes junior (medical assistant, resident), intermediate (attending physician), deputy senior (associate chief physician), and senior (chief physician), which are different to rankings used in Europe and America [9]. The upgrading of a physician's ranking needs to be evaluated according to the practice level, clinical work time, academic achievements, and educational background.

2.5.4. GDP levels of the 31 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities of mainland China

According to data from the national bureau of statistics of China, the level of economic development assessed by gross domestic product (GDP) and GDP per capita can both be divided into three categories: high, medium, and low (See Supplemental Table 1). Guangdong, Zhejiang, Shandong, Henan, Sichuan, Hubei, Hebei, Hunan, Fujian, Shanghai, and Beijing are regions with a high level of GDP. Those with a medium level of economic development include Anhui, Liaoning, Shaanxi, Jiangxi, Guangxi, Chongqing, Tianjin, Yunnan, Heilongjiang, and Inner Mongolia, while Jilin, Shanxi, Guizhou, Xinjiang, Gansu, Hainan, Ningxia, Qinghai, and Tibet are those with a low level of GDP (http://www.stats.gov.cn/).

2.6. Statistical analysis

Data were exported from the Wenjuanxing platform and analysed using R3.5.3. Continuous, normally distributed variables were presented as means ± standard deviation and tested by a t-test or one-way ANOVA among groups. Non-normally distributed continuous variables were presented as medians and interquartile ranges, and were compared by a Mann-Whitney U test. Frequency, rate and prevalence were used for categorical data and tested by χ2 tests.

Multiple logistic regression analysis was established to explore factors influencing the settings of independent anaesthesiology departments. The characteristics of chief physician personnel, professional features, and the features of the hospital were independent variables in the model. A Pearson correlation was conducted between the number of anaesthesiologists per 100,000 of the population and the gross domestic product (GDP), per capita GDP, per capita disposable income, and per capita consumption expenditure. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to analyse differences in the distribution of anaesthesiologists in different regions in mainland China. P<0•05 was considered statistically significant in this study.

2.7. Role of the funding source

The sponsors of this study played no role in the design of the survey, collection or analysis of data, interpretation of results, or in the preparation of this manuscript. The corresponding author had full access to all study data and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

3. Results

The nationwide questionnaire was completed by 11,432 hospital departments providing anaesthesia care in mainland China. The results of the questionnaire were summarised and divided into five parts as outlined below.

3.1. Departments providing anaesthesia care in mainland China

There were 11,432 hospital departments providing anaesthesia care in 31 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities in mainland China in June 2018. Among the 11,432 departments, 4591 (40•16%) departments belonged to specialised hospitals, while 6841 (59•84%) were affiliated to general hospitals. There were 2569 (22•49%), 7631 (66•80%), and 1232 (10•79%) departments belonging to tier 3, tier 2, and tier 1 or lower hospitals, respectively. The constituent ratios of departments providing anaesthesia care across mainland China are listed in Table 1 and Figure 2.

Table 1.

General characteristics of anaesthesiology in mainland China (n = 11,432)

| Total No. | GDP per capita |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | Medium | Low | ||

| Hospitals providing anaesthesia care | 11,432 | 3,841 (33•6%) | 4,562 (39•9%) | 3,029 (26•5%) |

| Independent anaesthesiology dept. | 5,162 (45•2%) | 2,095 (40•6%) | 1,789 (34•6%) | 1,278 (24•8%) |

| Regulated by other dept. | 6,270 (54•9%) | 1,746 (27•8%) | 2,773 (44•3%) | 1,751 (27•9%) |

| Anaesthesiologists and nurses (per 100,000) | ||||

| Anaesthesiologists | 0•67 | 0•75 | 0•65 | 0•58 |

| Anaesthesia nurses | 0•20 | 0•22 | 0•18 | 0•21 |

| Tiers of hospitals | ||||

| Tier 3 | 2,569 (22•5%) | 1,041 (40•5%) | 925 (36•0%) | 603 (23•5%) |

| Tier 2 | 7,631 (66•7%) | 2,278 (29•9%) | 3,163(41•5%) | 2,190 (28•7%) |

| Tier 1 | 1,232 (10•8%) | 522 (42•4%) | 474 (38•5%) | 236 (19•2%) |

| Number of beds (per 100,000) | 40•29 | 39•69 | 42•64 | 37•60 |

| Ranking (per 100,000): | ||||

| Chief | 0•04 | 0•05 | 0•03 | 0•03 |

| Associate chief | 0•11 | 0•13 | 0•10 | 0•09 |

| Attending | 0•25 | 0•29 | 0•25 | 0•21 |

| Residents | 0•27 | 0•28 | 0•27 | 0•26 |

| Educational background (per 100,000): | ||||

| Doctoral degree | 0•02 | 0•03 | 0•01 | 0•01 |

| Master degree | 0•03 | 0•06 | 0•02 | 0•01 |

| Bachelor degree | 0•15 | 0•19 | 0•14 | 0•10 |

| Junior college or Technical secondary schools | 0•19 | 0•23 | 0•17 | 0•16 |

Fig. 2.

The regional distribution of anaesthesiologists (per 100,000 of the population) in mainland China. Territories in red include Anhui, Jiangxi, Henan, Shanxi, Guangxi, Yunnan and Tibet. Territories in orange include Heilongjiang, Jilin, Fujian, Hebei, Guangdong, Hubei, Hunan, Hainan and Gansu. The territory in yellow is Sichuan. Territories in light green include Liaoning, Inner Mongolia, Shandong, Tianjin, Chongqing, Guizhou and Xinjiang. Territories in green include Zhejiang, Shanghai, Jiangsu, Beijing, Shaanxi, Ningxia and Qinghai.

3.2. Hospitals providing anaesthesia range in scale from no fixed beds to 15,000 beds, and no surgeons to 2450 surgeons

The total number of beds in the 11,432 hospitals providing anaesthesia care was 5,593,100, with an average of 489•25 beds per hospital. The total number of beds in all surgical departments was 1,818,332, with an average of 159•06 beds per hospital. There were 466,452 surgeons with an average of 40•08 surgeons per hospital. The scale of anaesthesiology departments correlated with the tier of the hospital. The higher the tier of the hospital, the higher the ratio of the number of operating rooms to the total number beds of the hospital. The number of beds and surgeons in each tier of hospitals are shown in Table 2.

Table 2.

The number of beds and surgeons in each tier of hospitals

| Scale of hospitals providing anaesthesia care in China |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of beds in total |

Number of beds in surgical depts. in total |

Number of surgeons with a ranking of attending or above |

||||

| Subtotal | Avg. | Sub-total | Avg. | Subtotal | Avg. | |

| Tier 3A | 2,244,025 | 1303•15 | 797,758 | 463•27 | 217,038 | 126•04 |

| Tier 3 other | 613,134 | 723•89 | 207,620 | 245•12 | 53,345 | 62•98 |

| Tier 2 | 2,607,466 | 341•69 | 775,824 | 101•67 | 188,209 | 24•66 |

| Tier 1 or lower | 128,475 | 104•28 | 37,130 | 30•14 | 7,860 | 6•38 |

| Total | 5,593,100 | 489•25 | 1,818,332 | 159•06 | 466,452 | 40•80 |

3.3. The settings of departments providing anaesthesia care were not same. The proportion of independent anaesthesiology departments was less than 50% in mainland China hospitals

There were 5,161 (45•15%) independent anaesthesiology departments among the 11,432 departments providing anaesthesia care. The proportion of independent anaesthesiology departments was higher in general hospitals (48•93%) than in specialised hospitals (38•18%). And the proportion of independent anaesthesiology departments had a positive correlation with the tier of the hospitals. The higher the tier of the hospital, the higher the proportion of independent anaesthesiology departments. Tier 3A hospitals had the highest proportion of independent anaesthesiology departments (80•31%), while tier 1 or lower hospitals had the lowest proportion (24•68%).

Most independent anaesthesiology departments had affiliated divisions, which included post-anaesthesia care units (PACUs, 83•18%), pain clinics (45•35%), pain departments (19•06%), and intensive care units (ICUs, 17•18%). The higher the tier of the hospital, the higher the proportion of affiliated divisions. Tier 3A hospitals had the highest rate of PACUs (95•30%), while tier 1 or lower hospitals had the lowest rate (60•20%). Moreover, most independent anaesthesiology departments did not have an affiliated ICU in mainland China hospitals, with the average rate being 17•18%.

The proportion of non-independent anaesthesiology departments was 54•85% (6,271 departments). These departments were supervised by the operating rooms (4•06%) and surgical departments (50•79%). The organisational structure of different tiers of hospitals is shown in Table 3.

Table 3.

The organisational structure of departments providing anaesthesia care in different tiers of hospitals in China (%)

| Type and tier of hospital | Total (frequency) | Relationship of administrative subordination (%) |

Affiliated divisions of independent anaesthesiology depts. (%) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent anaesthesiology dept. | Regulated by surgical dept. | Regulated by operating room | Pain clinic | Pain dept. | PACU | ICU | ||

| Special | 4,591 | 38•18 | 57•00 | 4•81 | 41•41 | 13•69 | 78•78 | 15•40 |

| General | 6,841 | 49•83 | 46•62 | 3•55 | 47•37 | 21•82 | 85•45 | 18•10 |

| Tier 3A | 1,722 | 80•31 | 19•05 | 0•64 | 59•65 | 22•78 | 95•30 | 15•47 |

| Tier 3 other | 847 | 67•53 | 31•17 | 1•30 | 47•73 | 25•00 | 92•83 | 19•41 |

| Tier 2 | 7,631 | 38•04 | 57•49 | 4•47 | 39•48 | 16•88 | 77•92 | 18•53 |

| Tier 1 or lower | 1,232 | 24•68 | 67•13 | 8•20 | 31•91 | 11•84 | 60•20 | 7•89 |

| Total | 11,432 | 45•15 | 50•79 | 4•06 | 45•35 | 19•06 | 83•18 | 17•18 |

ICU = intensive care unit; PACU = post-anaesthesia care unit.

We discovered two major factors influencing the setting of non-independent anaesthesiology departments. One factor was the capability of the anaesthesiologists-in-chief, including their ranking and educational background (p<0•05). The proportion of independent anaesthesiology departments in tier 3A hospitals, tier 3 other hospitals, and tier 1 or lower hospitals was 2•53 (OR = 2•53, 95% CI 2•16-2•96), 2•04 (OR = 2•04, 95% CI 1•74-2•41), and 0•67 (OR = 0•67, 95% CI 0•58-0•78) times higher than that in tier 2 hospitals, respectively. The proportion of independent anaesthesiology departments with a chief who had a doctoral degree (OR = 1•83, 95% CI 1•29-2•66) or master degree (OR = 1•62, 95% CI 1•38-1•90) was significantly higher than those with a chief who had a bachelor degree.

The second factor was the characteristics of the hospital, including type, tier, number of beds, and the number of doctors (p<0•05). The proportion of independent of anaesthesiology departments in general hospitals was 1.34 times higher than that in special hospitals (OR = 1•34, 95% CI 1•23-1•46). Hospitals with a high tier and more beds had a significantly higher proportion of independent anaesthesiology departments (see Table 4).

Table 4.

Multiple logistic regression analysis of independent factors associated with independent anaesthesiology departments

| Variable | OR | 2•50% | 97•50% | Pr (>|z|) | Significance | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group | 30-39 (ref) | 1•00 | ||||

| Below 30 | 0•88 | 0•56 | 1•34 | 0•55 | ||

| 40-49 | 0•98 | 0•86 | 1•12 | 0•80 | ||

| 50-59 | 1•02 | 0•85 | 1•23 | 0•81 | ||

| Above 60 | 1•24 | 0•88 | 1•75 | 0•22 | ||

| Tier of hospital | Tier 2 (ref) | 1•00 | ||||

| Tier 3A | 2•53 | 2•16 | 2•96 | <0•01 | ⁎⁎⁎ | |

| Tier 3 other | 2•04 | 1•74 | 2•41 | <0•01 | ⁎⁎⁎ | |

| Tier 1 or lower | 0•67 | 0•58 | 0•78 | <0•01 | ⁎⁎⁎ | |

| Education | Bachelor degree (ref) | 1•00 | ||||

| Doctoral degree | 1•83 | 1•29 | 2•66 | <0•01 | ⁎⁎ | |

| Junior college | 0•97 | 0•87 | 1•09 | 0•63 | ||

| Master degree | 1•62 | 1•38 | 1•90 | <0•01 | ⁎⁎⁎ | |

| Technical secondary schools | 0•82 | 0•64 | 1•05 | 0•12 | ||

| Ranking | Associate chief (ref) | 1•00 | ||||

| Chief | 1•50 | 1•31 | 1•73 | <0•01 | ⁎⁎⁎ | |

| Attending or lower | 0•62 | 0•56 | 0•68 | <0•01 | ⁎⁎⁎ | |

| Anaesthesia service duration | ≤5 (ref) | 1•00 | ||||

| ≥40 | 0•68 | 0•41 | 1•13 | 0•14 | ||

| 10~19 | 0•97 | 0•71 | 1•33 | 0•85 | ||

| 20~29 | 0•85 | 0•62 | 1•18 | 0•32 | ||

| 30~39 | 0•90 | 0•63 | 1•29 | 0•55 | ||

| 6~9 | 0•94 | 0•67 | 1•33 | 0•72 | ||

| Gender | Male (ref) | 1•00 | ||||

| Female | 0•95 | 0•86 | 1•05 | 0•29 | ||

| Type of hospital | Special (ref) | 1•00 | ||||

| General | 1•34 | 1•23 | 1•46 | <0•01 | ⁎⁎⁎ | |

| Total number of beds in hospital | 1•0005 | 1•0003 | 1•0006 | <0•01 | ⁎⁎⁎ | |

| Number of beds in surgical dept. | 1•0000 | 0•9998 | 1•0003 | 0•82 | ||

| Number of doctors in all surgical dept. requiring anaesthesia cooperation | 1•0018 | 1•0010 | 1•0026 | <0•01 | ⁎⁎⁎ |

p<0•01

p<0•001.

3.4. The quality and quantity of Chinese anaesthesiologists were less than satisfactory. Regions with better economic conditions had more anaesthesiologists per 100,000 of the population

General information on anaesthesiologists-in-chief, including age, length of work, ranking, and educational background were collected. The male to female ratio was 3•26:1. 77•35% were more than 40 years of age, while 48•99% were 40-49 years of age. The average working experience of anaesthesiologists-in-chief was 20•94 ± 9•42 years. The distribution of rankings and educational background of Chinese anaesthesiologists are summarised in Table 5. The ranking and educational background of the anaesthesiologists-in-chief differed significantly in the 3 tiers of hospitals (p<0•01). The majority of department chiefs (65•02%) had bachelor degrees, while 8•81% and 2•96% of department chiefs had master and doctoral degrees, respectively.

Table 5.

The distribution of ranking and educational background of Chinese anaesthesiologists from different tiers of hospitals

| Tier of hospital | Number of anaesthesiologists | Ranking |

Educational background |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chief | Associate chief | Attending | Residents | Doctoral degree | Master degree | Bachelor degree | Other degrees | ||

| Tier 3A | 38,101 | 3,215 | 7,447 | 14,258 | 13,181 | 2,922 | 12,637 | 19,533 | 3,009 |

| Tier 3 other | 9,943 | 549 | 1,755 | 3,825 | 3,814 | 79 | 1,147 | 6,779 | 1,938 |

| Tier 2 | 41,707 | 1,100 | 5,765 | 15,981 | 18,861 | 163 | 1,874 | 21,591 | 18,079 |

| Tier 1 or lower | 2,975 | 65 | 272 | 1,040 | 1,598 | 19 | 133 | 1,258 | 1,565 |

| Total | 92,726 | 4,929 | 15,239 | 35,104 | 37,454 | 3,183 | 15,791 | 49,161 | 24,591 |

| χ2: 2,540•9 | df: 9 | p-value:<0∙01 | χ2: 24,427 | df: 9 | p-value:<0∙01 | ||||

The proportion of rankings, and educational background differed significantly among the tiers of the hospital. The distribution shape of anaesthesiologists’ education was a downward-pointing one. The majority of anaesthesiologists from tier 3 hospitals had bachelor degrees or higher, while anaesthesiologists with a degree lower than bachelor (i.e., graduated from a junior college or technical secondary school) usually worked at tier 2 hospitals. Anaesthesiologists from tier 1 or lower hospitals graduated from junior college or technical secondary schools.

In June 2018, there were a total of 92,726 anaesthesiologists and 28,200 anaesthesia nurses in the 31 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities across mainland China. Although the number of anaesthesiologists has increased rapidly within the last few years, there were only 0•78 anaesthesiologists for each operating room in 2018. The ratio of the number of operating rooms to the number of anaesthesiologists was below 1:1•5 in each tier of hospitals, which was lower than the national standards for anaesthesia departments. Besides, there was less than one anaesthesia nurse for every three operating rooms on average. The ratio of the number of anaesthesiologists to the number of surgeons was 1:5•03, which was again less than satisfactory [10]. The number of anaesthesiologists, anaesthesia nurses and surgeons and their related ratios are shown in Table 6.

Table 6.

The number of anaesthesiologists, anaesthesia nurses and surgeons, and related ratios

| Tier of hospital | Number of anaesthesiologists | Number of anaesthesia nurses | Number of ORs | Number of ORs: number of anaesthesiologists | Number of ORs: number of anaesthesia nurses | Number of surgeons | Number of anaesthesiologists: number of surgeons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 3A | 38,101 | 12,795 | 33,837 | 1:1∙13 | 3:1∙13 | 217,038 | 1:5∙70 |

| Tier 3 other | 9,943 | 2,425 | 10,493 | 1:0∙95 | 3:0∙69 | 53,345 | 1:5∙37 |

| Tier 2 | 41,707 | 12,076 | 70,635 | 1:0∙59 | 3:0∙51 | 188,209 | 1:4∙51 |

| Tier 1 or lower | 2,975 | 904 | 4,499 | 1:0∙66 | 3:0∙60 | 7,860 | 1:2∙64 |

| Total | 92,726 | 28,200 | 119,464 | 1:0∙78 | 3:0∙71 | 466,452 | 1:5∙03 |

OR = operating room.

In June 2018, there were on average 6•7 anaesthesiologists (full-time residents) per 100,000 of the population in mainland China, which was an increase of 1 when compared with the results of an investigation performed in 2014 [7]. However, the survey also revealed the uneven distribution of anaesthesiologists throughout mainland China, ranging from 3•1 to 6•6 anaesthesiologists per 100,000 of the population with Tibet having the lowest number of anaesthesiologists (3•1 anaesthesiologists per 100,000 of the population). The details of anaesthesiologists’ distribution in mainland China are shown in Figure 2.

To further analyse the uneven distribution of Chinese anaesthesiologists, correlation analyses of the number of anaesthesiologists per 100,000 of the population and local economic parameters were performed. We divided the 31 provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities of China into three levels, high, medium, and low, by gross domestic product (GDP) and GDP per capita. The results showed that regions with a higher GDP per capita level had a significantly higher number of anaesthesiologists per 100,000 of the population. However, regions with a higher GDP level did not have a higher number of anaesthesiologists per 100,000 of the population (p<0•01) [see Table 7]. Furthermore, we found a positive correlation between the number of anaesthesiologists per 100,000 of the population and the annual per capita consumption expenditure (r = 0•5642; p<0•05), annual per capita disposable income (r = 0•5634; p<0•05), and GDP per capita (r = 0•445; p<0•05). The annual anaesthesia quantity per anaesthesiologist had a positive correlation with annual per capita consumption expenditure (r = 0•1638; p<0•05), annual per capita disposable income (r = 0•1639; p<0•05), and GDP per capita (r = 0•101; p<0•05).

Table 7.

The proportion of anaesthesiologists in regions with different levels of GDP

| GDP | Number of Provinces | Number of anaesthesiologists per 100,000 of population | GDP per capita | Number of Provinces | Number of anaesthesiologists per 100,000 of population |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | 10 | 6•74 | High | 10 | 7•98 |

| Medium | 11 | 7•35 | Medium | 11 | 6•76 |

| Low | 10 | 6•32 | Low | 10 | 5•74 |

| Total | 31 | 6•82* | Total | 31 | 6•82* |

| GDP | Df | Sum Sq | Mean Sq | F-value | Pr (>F) |

| Level | 2 | 5•60 | 2•801 | 0•940 | 0•402 |

| Residuals | 28 | 83•39 | 2•978 | ||

| GDP per capita | |||||

| Level | 2 | 25•38 | 12•692 | 5•587 | 0•009 |

| Residuals | 28 | 63•60 | 2•272 |

Mean value.

3.5. The workload of anaesthesiologists has been increasing year-by-year, by a rate of 10%

From 2015 to 2017, Chinese anaesthesiologists performed a total of 138,208,490 cases of anaesthesia, and the number of anaesthesia cases per year during this period was 46,069,497.

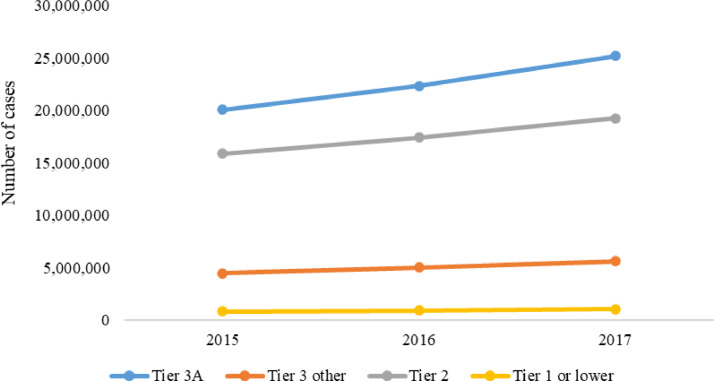

The total number of anaesthesia cases from 2015 to 2017 is summarised in Table 8 and Figure 3. The annual growth rate of anaesthesia cases was 11•32% from 2015 to 2017, with a 9•29% annual increase of anaesthesia cases in operating rooms and 15•64% annual increase of anaesthesia cases outside operating rooms.

Table 8.

The total number of cases from 2015 to 2017

| Year | Setting of anaesthesia |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Subtotal |

Anaesthesia cases inside the operating room |

Nonoperating room anaesthesia |

||||

| Number of cases | Growth rate (%) | Number of cases | Growth rate (%) | Number of cases | Growth rate (%) | |

| 2015 | 41,294,776 | 28,357,219 | 12,937,557 | |||

| 2016 | 45,739,031 | 10•76 | 30,895,252 | 8•95 | 14,843,779 | 14•73 |

| 2017 | 51,174,683 | 11•88 | 33,872,909 | 9•64 | 17,301,774 | 16•56 |

| Total | 138,208,490 | 93,125,380 | 45,083,110 | |||

Fig. 3.

The total number of anaesthesia cases from 2015 to 2017.

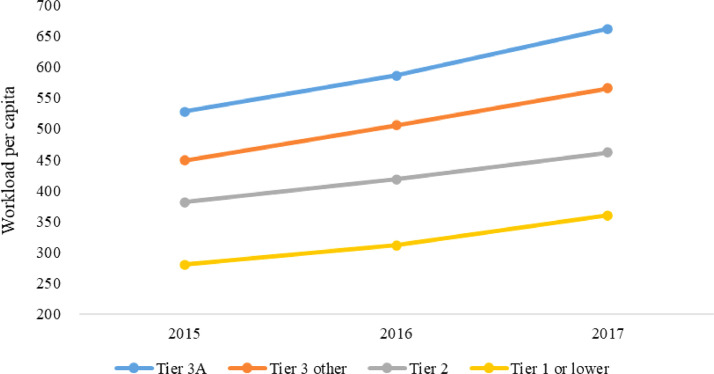

The number of anaesthesia cases at different tiers of hospitals from 2015 to 2017 is summarised in Table 9 and Figure 4. Anaesthesiologists at different tiers of hospitals had a varied annual workload. The higher the tier of the hospital, the larger the number of anaesthesia cases per capita. Anaesthesiologists in tier 3A hospitals had to complete 592 anaesthesia cases per year on average, while anaesthesiologists in tier 1 or lower hospitals only needed to complete 317 anaesthesia cases per year on average, less than a single case per day. Our survey also showed the rapid increase in the workload per capita from 2015 to 2017. Anaesthesiologists in tier 3A hospitals had to complete 75•52 more anaesthesia cases per year in 2017 in comparison with 2016. The annual workload per capita of anaesthesiologists at different tiers of hospitals, and its growth rate are shown in Table 10 and Figure 5.

Table 9.

The number of cases at different tiers of hospitals from 2015 to 2017

| 2017 | 2016 | 2015 | 3-year average | Number of anaesthesiologists | Annual average workload per capita | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 3A | 25,222,817 | 22,345,355 | 20,100,331 | 22,556,167•67 | 38,101 | 592•01 |

| Tier 3 other | 5,625,891 | 5,026,237 | 4,465,684 | 5,039,270•67 | 9,943 | 506•82 |

| Tier 2 | 19,255,741 | 17,441,162 | 15,895,280 | 17,530,727•67 | 41,707 | 420•33 |

| Tier 1 or lower | 1,070,234 | 926,277 | 833,481 | 943,330•67 | 2,975 | 317•09 |

| Total | 51,174,683 | 45,739,031 | 41,294,776 | 46,069,496•67 | 92,726 | 496•83 |

Fig. 4.

The number of anaesthesia cases at different tiers of hospitals from 2015 to 2017.

Table 10.

The annual workload per capita of anaesthesiologists from different tiers of hospitals and growth rates

| Year | Tier 3A |

Tier 3 other |

Tier 2 |

Tier 1 or lower |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Workload per capita | Growth | Growth rate (%) | Workload per capita | Growth | Growth rate (%) | Workload per capita | Growth | Growth rate (%) | Workload per capita | Growth | Growth rate (%) | |

| 2015 | 527•55 | 449•13 | 381•12 | 280•16 | ||||||||

| 2016 | 586•48 | 58•92 | 11•17 | 505•51 | 56•38 | 12•55 | 418•18 | 37•07 | 9•73 | 311•35 | 31•19 | 11•13 |

| 2017 | 662•00 | 75•52 | 12•88 | 565•81 | 60•31 | 11•93 | 461•69 | 43•51 | 10•40 | 359•74 | 48•39 | 15•54 |

Fig. 5.

The annual workload per capita of anaesthesiologists in different tiers of hospitals.

4. Discussion

This survey is the first large investigation to be conducted since the discipline of anaesthesiology was established in China, and is an important step in comprehensively understanding the current situation of Chinese anaesthesiology. General information and the current status of all hospital departments providing anaesthesia care in mainland China were accurately collected from 11,432 departments throughout the Chinese mainland.

4.1. Summary of the main findings

In recent years, the discipline of anaesthesiology in China has made significant progress, with an increase in the proportion of independent anaesthesiology departments and affiliated third-level departments [11]. However, the percentage of independent anaesthesiology departments among all departments providing anaesthesia care (45•15%) is still far from satisfactory. And the anaesthesiology workforce is limited with improper configuration, which leads to an uneven distribution of the workload around the country.

4.2. Number of physician anaesthesia providers

The number of Chinese anaesthesiologists (or physician anaesthesia providers) has steadily increased and reached more than 90,000, which basically meets the requirements and expectations of the No. 21 document (Notice on Issuing Opinions on Strengthening and Improving Anaesthesia Medical Services) [12]. The number of anaesthesiologists per 100,000 of the population in 2018 also increased significantly from 2015, and the number of anaesthesia nurses has tripled from 9,147 in 2015 to 28,200 in 2018.

Our survey showed, however, a relatively low number of anaesthesiologists in many provinces of mainland China. At present, the ratio of anaesthesiologists to surgeons, the ratio of operating rooms to anaesthesiologists, and the ratio of operating rooms to anaesthesia nurses do not meet the basic standards of the nation's criteria for the settings of anaesthesia departments and the quality control of anaesthesiology departments, let alone comparisons with the ratio of anaesthesiologists abroad.

There were marked disparities in the distribution of the anaesthesia workforce between regions and provinces. The number of anaesthesiologists per 100,000 of the population in Beijing is close to the world's advanced level, but Tibet has yet to meet international minimum standards, with 5 anaesthesiologists per 100,000 of the population. This study also found that the number of anaesthesiologists per 100,000 of the population is closely related to the level of economic development of the region or province.

When compared with other countries around the world, China has become the country with the largest number of anaesthesiologists [13]. According to global standards for the proportion of anaesthesiologists issued by the World Federation of Societies of Anaesthesiologists (WFSA), a minimum of 5 anaesthesiologists per 100,000 of the population is required [14]. However, the number of anaesthesiologists per 100,000 of the population in China is still far from that of high-income countries (17•96 per 100,000). The number in China has just about reached the average level of middle-high income countries (6•89 per 100,000), and is less than a third of that in Bolivia (19•21 per 100,000) [13]. When compared with other major developing countries in the world, such as Brazil, Russia, India, and South Africa, the number of anaesthesiologists per 100,000 of the population in China (5•12 per 100,000) only exceeds the number in India (1•26 per 100,000) and is far behind that of Russia (20•91 per 100,000), Brazil (11•55 per 100,000), and South Africa (16•18 per 100,000) [13]. Therefore, the development of Chinese anaesthesiology still has a long way to go.

In addition, different tiers of medical institutions have different structures. Significant differences were found in educational background and physician ranking between different tiers of hospitals. The distribution shape of anaesthesiologists’ education is an inverted triangle (Fig. 6). A large number of well-trained, higher educational background anaesthesiologists is concentrated in tier 3 hospitals, and there is a huge gap between tier 1 or lower hospitals and tier 3 hospitals in terms of the number of well-trained anaesthesiologists, their educational background, and rankings.

Fig. 6.

The distribution of anaesthesiologists’ educational background in mainland China.

4.3. Expansion of the anaesthesia workload and workforce

From 2015 to 2017, the workload of Chinese anaesthesiologists has increased by 10% to 51,174,683 anaesthesia cases per year. Cases inside and outside operating rooms increased by 9% and 15%, respectively. However, the number of anaesthesiologists only increased by 5•97% during the same period, which is half of the increased rate of anaesthesia cases. Predictably, if the growth in the number of anaesthesia cases and anaesthesiologists continue in this manner, Chinese anaesthesiologists are going to be more and more stressed in the near future, with increased burnout and declining job satisfaction. There is increasing evidence that burnout has negative effects on patient care, professionalism, the physicians’ care and safety, and the viability of healthcare systems [15,16]. In a previous study performed in 2015, burnout rates of anaesthesiologists in Beijing, Tianjin, and Hebei were 69%, 70%, and 68%, respectively, which were much higher than those in western countries [17]. Therefore, it is particularly important to strengthen the development of anaesthesiology and to increase the number of anaesthesiologists to mitigate the foreseeable inconsistencies between the anaesthesia workload and the workforce.

4.4. Characteristics of the survey

This was the first general survey conducted by the national anaesthesiology official organisation of all anaesthesia departments in China, and it was supported by government health departments at all levels. It is also the first systematic description and macro summary of the current development of anaesthesiology in China.

The survey summarised the current status and characteristics of Chinese anaesthesiology, compared differences in the development of the discipline and workforce distribution among regions with different economic development levels in China, and discovered existing problems in the current construction. The survey revealed that the current development of the anaesthesiology in China is gradually lagging behind the growing demand for medical and health services by Chinese citizens.

The study observed that the proportion of independent anaesthesiology departments is far below satisfactory. This finding suggests that the importance of anaesthesiology departments, which should be regarded as platform departments or core backbone departments, are not fully recognised at the hospital level. Favourable policies should be implemented to emphasise the development of anaesthesiology among other medical disciplines in hospitals, and ultimately increase their proportion in Chinese hospitals.

The other important problem highlighted by the survey is that the number of Chinese anaesthesia providers is insufficient, which implies: (1) that the attraction of anaesthesiology as a discipline is less than satisfactory (which may be due to multiple reasons such as high workloads and low wages); (2) the public awareness of anaesthesiology in China needs to be improved, so as to increase the social status of anaesthesiology and attract more medical students; and (3) that more attention should be paid to physician training and teaching, and medical schools should increase the enrolment ratio of specialist anaesthesiologists.

Therefore, the study provides objective evidence for healthcare policy makers to formulate policies for the overall development of the discipline, and offers new supply-side reform ideas for mitigating the contradiction between doctors and patients.

In addition, the successful implementation of the survey accumulated valuable experience in the design, organisation and investigation of nationwide medical discipline surveys, which could also facilitate future surveys to some extent. At the same time, this study shares China's experience of anaesthesiology specialty construction with countries that have different economic development levels around the world. The discipline of anaesthesiology should have more preferential policies. Attention should be paid to the construction of anaesthesia disciplines in hospitals of different levels and regions with different economic development levels, and to the cultivation and recruitment of anaesthesia professionals is of great importance as well.

4.5. Limitations

Firstly, despite the quality control measures that were implemented, potential information bias cannot be eliminated. The questionnaire surveys were primarily handled by local investigators in each province with different levels of economic development, and the educational and work backgrounds were inconsistent among the respondents. These factors could lead to information bias. Secondly, data collection, regarding the number of anaesthesia nurses, may not be accurate due to the different roles of nurses. For example, in some hospitals, anaesthesia departments share nurses with operating theatres, and nurses working in the operating rooms can be both anaesthesia nurses, scrub nurses, or circulating nurses.

4.6. Conclusions

This study shows that while the overall development of anaesthesiology in China has been rapid during recent years, problems such as imbalanced development among the regions, heavy workloads, and large gaps in department construction are still common. The development of anaesthesiology in China is unique, but it needs to be fast to catch up with the development of leading departments around the world, and also to meet the people's increasing healthcare needs. The unbalanced development of China's economy and socialisation are major reasons for the unbalanced development of anaesthesiology.

The development of anaesthesiology in China is not easy, and there are no shortcuts. The health development of the discipline depends on investment in medical education, employment and social recognition by our society and government. The most fundamental solution to the development bottleneck may be to increase anaesthesiologists’ social status and the public's knowledge of anaesthesiology.

Declaration of Competing Interest

All authors confirm that no conflicts of interest exist and that there is nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

Contributors

Dr Changsheng Zhang and Dr Shengshu Wang are co-first authors of this paper.

Dr Changsheng Zhang conceptualised and designed the study, coordinated and supervised data collection, interpreted data, and drafted the initial manuscript.

Dr Shengshu Wang coordinated and supervised data collection, analysed the data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

Dr Hange Li designed the questionnaire, analysed and interpreted the data, and edited the manuscript.

Prof. Fan Su conceptualised and designed the study, and coordinated and supervised data collection.

Prof. Yuguang Huang conceptualised and designed the study, and coordinated and supervised data collection.

Prof. Weidong Mi conceptualised and designed the study, designed the questionnaire, coordinated and supervised data collection, and reviewed and revised the manuscript.

The Chinese Anaesthesiology Department Tracking Collaboration Group distributed and collected the questionnaire, entered, and validated the raw data.

All authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Ms. Yi Li from the Department of Public Health and Safety Monitoring, Chongqing Centre for Disease Control and Prevention for professional data management, statistical services, and preparation of the manuscript.

Data sharing statement

The Chinese Anaesthesiology Department Tracking Database (CADTD) is publicly available but need to obtain administrative permission from each investigative hospital.

Footnotes

Editor note: The Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary material associated with this article can be found, in the online version, at doi:10.1016/j.lanwpc.2021.100166.

Contributor Information

Yuguang Huang, Email: garybeijing@163.com.

Weidong Mi, Email: wwdd1962@163.com.

Appendix. Supplementary materials

References

- 1.Access GBDH, Quality C. Measuring performance on the healthcare access and quality index for 195 countries and territories and selected subnational locations: a systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet. 2018;391(10136):2236–2271. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30994-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Bureau of Statistics of China. Number of surgeries in Chinese healthcare institutions 2018; c 2020 [cited 2020 May 19]. Available from: http://www.stats.gov.cn/english/.

- 3.National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China . China Peking Union Medical University Press; Beijing: 2020. The Yearbook of Chinese Healthcare. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feng X, Yu B, Yu X, Huang Y, Wang G, Liu J. A history of anesthesia in China. In: Eger E II, Saidman LJ, Westhorpe RN, editors. The wondrous story of anesthesia. Springer; New York, NY: 2014. pp. 345–354. editors. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fang EF, Scheibye-Knudsen M, Jahn HJ, Li J, Ling L, Guo H. A research agenda for aging in China in the 21st century. Ageing Res Rev. 2015;24:197–205. doi: 10.1016/j.arr.2015.08.003. Pt B. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rui M, Ting C, Pengqian F, Xinqiao F. Burnout among anaesthetists in Chinese hospitals: a multicentre, cross-sectional survey in 6 provinces. J Eval Clin Pract. 2016;22(3):387–394. doi: 10.1111/jep.12498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang L, Zhu T, Li J, Liu J. A survey of human resources of the anesthesiology in China: investigation of reform direction of human resources allocation of Chinese medical and health system based on the current status of human resources of the Anestheisology. Chinese Journal of Anestheisology. 2017;37(11):1281–1286. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Appraisal and Examination Rules for Medical Institutions: National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China; 1995. c2020 [cited 2020 Oct 23]; Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/fzs/s3576/201808/0415d028c18a46c4a316d8339edcdf44.shtml.

- 9.Ni C. Structural change and historical change of ranking system of physicians in China. Hospital Management Forum. 2019;36(7):9–12. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guidelines for building medical service ability of anaesthesiology department (in-test). National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China, 2019. c2020 [cited 2020 Dec 12]; Available from: http://www.gov.cn/xinwen/2019-12/18/content_5462015.htm

- 11.Liu J. The discipline construction and the development trend of China anesthesiology. Practical Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2014;11(2):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Notice on issuing opinions on strengthening and improving anesthesia medical services. National Health Commission of the People's Republic of China., 2018. c2020 [cited 2020 Sep 07]; Available from: http://www.nhc.gov.cn/yzygj/s3594q/201808/4479a1dbac7f43dcba54e6dce873a533.shtml.

- 13.Kempthorne P, Morriss WW, Mellin-Olsen J, Gore-Booth J. The WFSA global anesthesia workforce survey. Anesth Analg. 2017;125(3):981–990. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gelb AW, Morriss WW, Johnson W, Merry AF. International standards for a safe practice of anesthesia. World Health Organization-World Federation of Societies of Anaesthesiologists (WHO-WFSA) Can J Anaesth. 2018;65(6):698–708. doi: 10.1007/s12630-018-1111-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lancet The. Physician burnout: a global crisis. Lancet. 2019;394(10193):93. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31573-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lo D, Wu F, Chan M, Chu R, Li D. A systematic review of burnout among doctors in China: a cultural perspective. Asia Pac Fam Med. 2018;17:3. doi: 10.1186/s12930-018-0040-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Li H, Zuo M, Gelb AW, Zhang B, Zhao X, Yao D. Chinese anesthesiologists have high burnout and low job satisfaction: a cross-sectional survey. Anesth Analg. 2018;126(3):1004–1012. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000002776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.