Abstract

Background

Homelessness has emerged as a public health priority, with growing numbers of vulnerable populations despite advances in social welfare. In February 2020, the United Nations passed a historic resolution, identifying the need to adopt social‐protection systems and ensure access to safe and affordable housing for all. The establishment of housing stability is a critical outcome that intersects with other social inequities. Prior research has shown that in comparison to the general population, people experiencing homelessness have higher rates of infectious diseases, chronic illnesses, and mental‐health disorders, along with disproportionately poorer outcomes. Hence, there is an urgent need to identify effective interventions to improve the lives of people living with homelessness.

Objectives

The objective of this systematic review is to identify, appraise, and synthesise the best available evidence on the benefits and cost‐effectiveness of interventions to improve the health and social outcomes of people experiencing homelessness.

Search Methods

In consultation with an information scientist, we searched nine bibliographic databases, including Medline, EMBASE, and Cochrane CENTRAL, from database inception to February 10, 2020 using keywords and MeSH terms. We conducted a focused grey literature search and consulted experts for additional studies.

Selection Criteria

Teams of two reviewers independently screened studies against our inclusion criteria. We included randomised control trials (RCTs) and quasi‐experimental studies conducted among populations experiencing homelessness in high‐income countries. Eligible interventions included permanent supportive housing (PSH), income assistance, standard case management (SCM), peer support, mental health interventions such as assertive community treatment (ACT), intensive case management (ICM), critical time intervention (CTI) and injectable antipsychotics, and substance‐use interventions, including supervised consumption facilities (SCFs), managed alcohol programmes and opioid agonist therapy. Outcomes of interest were housing stability, mental health, quality of life, substance use, hospitalisations, employment and income.

Data Collection and Analysis

Teams of two reviewers extracted data in duplicate and independently. We assessed risk of bias using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool. We performed our statistical analyses using RevMan 5.3. For dichotomous data, we used odds ratios and risk ratios with 95% confidence intervals. For continuous data, we used the mean difference (MD) with a 95% CI if the outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We used the standardised mean difference with a 95% CI to combine trials that measured the same outcome but used different methods of measurement. Whenever possible, we pooled effect estimates using a random‐effects model.

Main Results

The search resulted in 15,889 citations. We included 86 studies (128 citations) that examined the effectiveness and/or cost‐effectiveness of interventions for people with lived experience of homelessness. Studies were conducted in the United States (73), Canada (8), United Kingdom (2), the Netherlands (2) and Australia (1). The studies were of low to moderate certainty, with several concerns regarding the risk of bias. PSH was found to have significant benefits on housing stability as compared to usual care. These benefits impacted both high‐ and moderate‐needs populations with significant cimorbid mental illness and substance‐use disorders. PSH may also reduce emergency department visits and days spent hospitalised. Most studies found no significant benefit of PSH on mental‐health or substance‐use outcomes. The effect on quality of life was also mixed and unclear. In one study, PSH resulted in lower odds of obtaining employment. The effect on income showed no significant differences. Income assistance appeared to have some benefits in improving housing stability, particularly in the form of rental subsidies. Although short‐term improvement in depression and perceived stress levels were reported, no evidence of the long‐term effect on mental health measures was found. No consistent impact on the outcomes of quality of life, substance use, hospitalisations, employment status, or earned income could be detected when compared with usual services. SCM interventions may have a small beneficial effect on housing stability, though results were mixed. Results for peer support interventions were also mixed, though no benefit was noted in housing stability specifically. Mental health interventions (ICM, ACT, CTI) appeared to reduce the number of days homeless and had varied effects on psychiatric symptoms, quality of life, and substance use over time. Cost analyses of PSH interventions reported mixed results. Seven studies showed that PSH interventions were associated with increased cost to payers and that the cost of the interventions were only partially offset by savings in medical‐ and social‐services costs. Six studies revealed that PSH interventions saved the payers money. Two studies focused on the cost‐effectiveness of income‐assistance interventions. For each additional day housed, clients who received income assistance incurred additional costs of US$45 (95% CI, −$19, −$108) from the societal perspective. In addition, the benefits gained from temporary financial assistance were found to outweigh the costs, with a net savings of US$20,548. The economic implications of case management interventions (SCM, ICM, ACT, CTI) was highly uncertain. SCM clients were found to incur higher costs than those receiving the usual care. For ICM, all included studies suggested that the intervention may be cost‐offset or cost‐effective. Regarding ACT, included studies consistently revealed that ACT saved payers money and improved health outcomes than usual care. Despite having comparable costs (US$52,574 vs. US$51,749), CTI led to greater nonhomeless nights (508 vs. 450 nights) compared to usual services.

Authors' Conclusions

PSH interventions improved housing stability for people living with homelessness. High‐intensity case management and income‐assistance interventions may also benefit housing stability. The majority of included interventions inconsistently detected benefits for mental health, quality of life, substance use, employment and income. These results have important implications for public health, social policy, and community programme implementation. The COVID‐19 pandemic has highlighted the urgent need to tackle systemic inequality and address social determinants of health. Our review provides timely evidence on PSH, income assistance, and mental health interventions as a means of improving housing stability. PSH has major cost and policy implications and this approach could play a key role in ending homelessness. Evidence‐based reviews like this one can guide practice and outcome research and contribute to advancing international networks committed to solving homelessness.

1. PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

1.1. Housing, income assistance, and case management improve housing outcomes for persons with lived experience of homelessness

Permanent supportive housing (PSH) interventions appear to improve short‐ and long‐term housing stability for persons with lived experience of homelessness. Income assistance and intensive mental health interventions show moderate benefits in housing outcomes, and evidence on standardised case management suggests potential to improve housing stability. Peer support alone does not impact housing stability. Inconsistent results on mental health, substance use and other social outcomes require additional research.

1.1.1. What is this review about?

Homelessness greatly magnifies morbidity and mortality and worsens preventable health and social inequities. We present evidence on a wide range of interventions targeting homelessness: PSH; income assistance; standard case management (SCM) and peer support; mental health interventions such as assertive community treatment (ACT), intensive case management (ICM), critical time intervention (CTI), and injectable antipsychotics; and substance use interventions such as SCFs, managed alcohol programmes (MAPs) and pharmacological interventions for opioid use disorders.

What is the aim of this review?

This systematic review and meta‐analysis examines the effects of a broad range of interventions on housing stability, mental health, quality of life, substance use, hospitalisations and health service utilisation, as well as employment and income among individuals with lived experience of homelessness.

1.2. What studies are included?

We included 86 studies across 128 publications among individuals with lived experience of homelessness. The vast majority of studies followed a randomised controlled design. Most took place in the United States (73). The rest were undertaken in Canada (8), the UK (2), the Netherlands (2) and Australia (1).

1.3. What are the main findings of this review?

Studies on housing interventions showed significant improvements in housing stability, with potential sustained benefit for up to 5.4 years. Income assistance interventions also appeared to be effective in improving housing outcomes. SCM carried the potential to improve housing, with mixed evidence suggesting its added benefit, whereas peer support programmes demonstrated no impact on housing relative to usual care.

Intensive mental health interventions demonstrated moderate improvements in housing stability and often worked in synergy with permanent housing.

Cost‐analysis studies of housing interventions reported mixed economic results. Income assistance was associated with increased costs that were offset by its added benefits. Intensive mental health interventions, such as ACT, ICM and CTI, were found to be economically beneficial. In contrast, SCM did not offer good value for money compared to other interventions.

No economic evidence was found for peer support, injectable antipsychotics or substance use interventions.

1.4. What do the findings of this review mean?

PSH may improve and maintain housing stability. Further examination of implementation barriers of housing programmes is needed to inform decisionmakers.

Income assistance, SCM and intensive mental health interventions carry the potential to improve housing outcomes, but more research is needed to examine their mechanisms. Our results on mental health and other social outcomes were mixed and inconclusive. This could be attributed to the significant proportion of study participants who were suffering from chronic mental health or substance use conditions.

1.5. What are the implications for research and policy?

More longitudinal research is needed to better examine nonhousing outcomes. Furthermore, poor reporting, lack of blinding and allocation bias reduced the certainty and precision of our results.

There are other ongoing gaps that warrant more investigation, including peer support programmes, community substance use interventions, and programmes targeted towards special populations. Further examination of implementation barriers of housing programmes is also needed.

The absence of evidence on substance use interventions for people living with homelessness represents an important research and policy gap.

1.6. How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies that had been published up until February 10, 2020.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1. The problem, condition or issue

Worldwide, over 1.8 billion people lack adequate housing and almost 25% of the world's urban population reside in informal accommodation (UN HRC, 2019). “People with a lived experience of homelessness” is a term coined to describe individuals who are, have been, or at risk of becoming homeless. This population lacks stable, permanent, appropriate housing, or may be without immediate prospect, means and ability to acquire it (Canadian Observatory on Homelessness, 2017). This population continues to grow, giving rise to a major international clinical and public health priority. Homelessness is strongly associated with high levels of morbidity (Hwang, 2009) and mortality (Nordentoft & Wandall‐Holm, 2003). People with lived experience of homelessness are at an increased risk for acute illnesses such as traumatic injury (including brain injury), frostbite, peripheral vascular disease, soft tissue infections, and dental decay (Hwang & Bugeja, 2000). Many homeless people also suffer from chronic medical conditions such as diabetes (Hwang & Bugeja, 2000), cardiovascular disease (Lee et al., 2005), cancer (Krakowsky et al., 2013) and respiratory illnesses (Raoult et al., 2001). Rates of serious mental illness (Fazel et al., 2014), cognitive impairment (Stergiopoulos et al., 2015b) and drug and alcohol use (Aubry et al., 2012; Grinman et al., 2010; Kennedy et al., 2017; Kerr et al., 2009; Torchalla et al., 2011) are disproportionately high, as are rates of homicide and suicide (Cheung & Hwang, 2004). Moreover, people who are homeless experience a disproportionately high prevalence of infectious diseases such as hepatitis C, HIV and tuberculosis (Beijer et al., 2012; Corneil et al., 2006; Roy et al., 2001). Despite the significant burden of disease, people with lived experience of homelessness are less likely to access and maintain the care required for their cure and treatment (Milloy et al., 2012; Palepu et al., 2011). People with lived experience of homelessness encounter many barriers to health and social care. The competing need to find food and shelter results in delays in accessing health care services (Gelberg et al., 1997) and those who do seek health care often experience discrimination that precludes adequate uptake of preventative health services (Wen et al., 2007). The structural stigma they experience when accessing health or social services is a major cause of their health inequities (Hatzenbuehler et al., 2013). For example, people with lived experience of homelessness with coexisting mental health conditions report specific barriers to accessing care, such as being unaware of the location of care, affordability, wait times and having experienced previous rejection from health or social services (Rosenheck et al., 1997). In addition, many health care recommendations, such as dietary advice, can prove impossible without access to resources, such as proper nutrition and cooking facilities (Hwang, 2001). This lack of appropriate access to community based care and reliable social contexts to implement preventive health behaviours results in disproportionately high acute care use by people with lived experience of homelessness (Saab et al., 2016). This population frequently experiences longer hospital stays and a higher risk of unplanned readmission than the general population (Saab et al., 2016), as discharge planning is compromised by inadequate housing to return to and suboptimal structures to support proper follow up care (Kushel, 2016).

Substantial research demonstrates that people with lived experience of homelessness benefit from receiving tailored, patient‐centred care within interprofessional teams with an integrated approach to community and social services (Coltman et al., 2015; Hwang & Burns 2014; James et al., 2005). A systematic review on health interventions for marginalised and socially excluded populations identified a range of potentially effective interventions that have relevance for marginalised and excluded populations, but it was not specific to people with lived experience of homelessness (Luchenski et al., 2017). Additionally, numerous studies have looked at the effectiveness of patient‐centred care for people with lived experience of homelessness within community services and social services (Coltman et al., 2015; Hwang & Burns 2014; James et al., 2005). Our review aims to evaluate current evidence on the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of interventions that directly or indirectly improve the health of those with lived experience of homelessness.

2.2. Description of the condition

2.2.1. The intervention

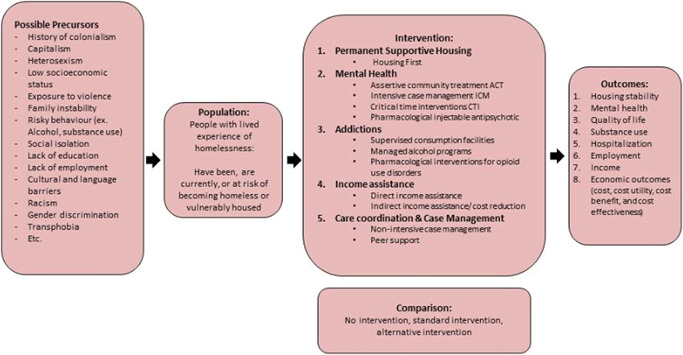

We evaluated the effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of interventions for people with lived experience of homelessness that aim to improve these people's health, service usage, and social outcomes. Prior to conducting this systematic review, to rank the priority topics and the needs that were the most important for this vulnerable population, we used a Delphi Consensus process (Keeney et al., 2010) to engage 76 people with lived experience of homelessness and 84 healthcare workers and researchers with professional experience in the field of homelessness (Shoemaker et al., 2020). A literature review and consensus process informed the final selection of the five categories of interventions to be included in this review (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Logic model

2.3. Description of the intervention

2.3.1. Housing interventions

PSH is long‐term housing in the community combined with the provision of individualised supportive services that are tailored to participants' needs and choices. PSH follows the principles of “Housing First,” whereby the ability to access housing is not contingent on sobriety/abstinence, or the ability to follow through with treatment plans (Benston, 2015). This approach runs in contrast to what has been the orthodoxy of “treatment‐first” approaches, whereby people experiencing homelessness are placed in emergency services and must address certain personal issues (e.g., addictions, mental health) prior to being deemed “ready” for housing. Rather, in “Housing First,” the priority is to provide an individual with permanent housing and the choice to access treatment and supports, such as ACT or ICM offered by a multidisciplinary team (Aubry, Nelson, et al., 2015; Somers et al., 2017).

2.3.2. Income assistance interventions

Income assistance is a fundamental intervention for preventing and addressing homelessness. It consists of interventions that directly increase an individual's available income or improve their access to basic living necessities. Some examples include government assistance (i.e., income‐supplement programme (Brownell et al., 2016), charity donation or panhandling (Poremski et al., 2015), provision of cheques, tax benefits or cash transfers. Cash transfers are a form of financial aid offered on either a conditional or an unconditional basis (Lagarde et al., 2009). Further examples include support finding and maintaining employment or offering information on income benefits or financial literacy/debt‐management counselling (Abbott & Hobby, 2000), and the provision of food, daycare and fuel or rent supplements (Gruber et al., 2000; Power et al., 2015; Whittle et al., 2015).

2.3.3. SCM and peer support

Case management entails a myriad of services in which people with multiple morbidities or issues are supported by case managers who assess, plan and facilitate the access to health and social services that are necessary for the person's plan of care and recovery (De Vet et al., 2013). There are many different types of care‐coordination models, and these vary according to approach and caseload. The more intensive models of case management will be examined under “Mental‐health interventions”. Here, we will examine two specific areas of less intensive‐care coordination.

Standard case management

SCM allows for the coordination of an array of social, health‐care and other services to help individuals maintain good health and strong social relationships. This is achieved by “including engagement, assessment, planning, linkage with resources, consultation with families, collaboration with psychiatrists, patient psycho‐education, and crisis intervention” (Kanter, 1989). The Case Manager or navigator's role is performed by either a clinician, nurse, community outreach worker or social worker with an average caseload of 35 clients (De Vet, 2013; Guarino, 2011). The target population for standard case‐management models are people who are experiencing homelessness or those who are vulnerably‐housed and have complex health concerns and are presenting to primary‐care practitioners and are often provided with this type of care as a time‐limited service (De Vet, 2013).

Peer support

Peer support includes the sharing of knowledge, experience, emotional, social or practical help by or with an individual who has experienced a similar background to the service user (Mead et al., 2001). Peer support workers may be termed differently in different settings, either as mentors, recovery coaches, or life coaches, and all offer emotional and social support to individuals who are newly homeless or on a treatment plan or path to recovery from substance use or homelessness (Barker & Maguire, 2017). Thus, due to their shared experiences and ability to establish a relationship built on trust, peers are uniquely positioned to assist persons experiencing homelessness due to their shared experiences and ability to establish a relationship built on trust (Barker & Maguire, 2017; Faulkner & Basset, 2012; Finlayson et al., 2016).

2.3.4. Mental health interventions

We assessed four evidence‐supported interventions that are relevant to serious mental illness, which is defined as conditions that substantially limit major life activities due to functional impairment (SAMHSA, 2016).

Assertive community treatment

ACT consists of a multidisciplinary group of healthcare workers in the community, that offers team‐based care to persons with high levels of needs. This team has 24‐h/day, 7‐days/week availability and provides services tailored to the needs and goals of each service user (Coldwell & Bender, 2007; De Vet et al., 2013). There is no time limit on the services provided, but transfer to lower intensity services is common after a period of stability (Homeless Hub, n.d.) Ten service users per case manager is the typical caseload, and services are offered in a natural setting, such as the workplace, home or social setting (De Vet et al., 2013).

Intensive case management

ICM is offered to persons with serious mental illness but who typically have moderate needs, such as fewer hospitalisations or less functional impairment, as well as for people experiencing addictions (Dieterich et al., 2017). ICM helps service users through the support of a case manager that brokers access to an array of services. The case manager accompanies the service user to meetings and can be available for up to 12 h/day, 7 days a week. Case managers for ICM often have caseloads of 15–20 service users each (De Vet, 2013).

Critical time intervention

CTIs are a form of time‐limited ICM, defined as a service that supports continuity of care for service users during times of transition; for example, from a shelter to independent housing or following discharge from the hospital. This service strengthens the person's network of support in the community (Silberman School of Social Work, 2017). It is administered by a CTI worker and is usually limited to a period of 6–9 months after institutional discharge or placement in housing. It comprises of three phases: Phase 1: Transition—Provide support and begin to connect the client to people and agencies that will assume the primary role of support; Phase 2: Tryout—Monitor and strengthen support network and client's skills; Phase 3: Transfer of care—Terminate CTI services with support network safely in place (Gaetz et al., 2013; Herman & Mandiberg, 2010).

Injectable antipsychotics

Injectable antipsychotics have a major role to play in the treatment for psychosis of patients living in precarious situations as these individuals often have a limited ability to follow through with oral medication treatment plans (Llorca et al., 2013). The clinical effectiveness of newer (aripiprazole, olanzapine, paliperidone and risperidone) and older antipsychotics (haloperidol, fluphenazine, flupenthixol) is similar (Castillo & Stroup, 2015), but their effectiveness among homeless and vulnerably housed persons is unknown.

2.3.5. Interventions for substance use

We assessed three interventions relating to substance‐use disorders (SUDs) that apply to people experiencing homelessness and those who are vulnerably housed.

Supervised consumption facilities (SCFs)

SCFs are legally sanctioned facilities where people who use substances can consume pre‐obtained substances under supervision (Drug Policy Alliance, n.d.). There exist various terminologies for these facilities, including supervised injection facilities (SIF), supervised consumption sites (SCS), medically supervised injection centres (MCIS), among others. Such facilities are frequently used as safe spaces for people experiencing homelessness and those who are vulnerably housed as well as substance users.

Managed alcohol programmes

A MAP provides shelter, medical assistance, social services and the provision of regulated alcohol to help residents cope with severe alcohol use disorder (Shepherds of Good Hope Foundation, n.d.). This programme is provided by professional staff and nurses.

Pharmacological interventions for opioid use disorder

The effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of opioid therapy medications, including buprenorphine/naloxone, naloxone, naltrexone (British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, 2017) methadone, and injectable diacetylmorphine (heroin; Haasen et al., 2007), have been documented in general‐population studies. The literature demonstrates the effectiveness of naltrexone (Krupitsky et al., 2011), buprenorphine (with or without naloxone), and methadone (McKeganey et al., 2013), as well as injectable diacetylmorphine (heroin; Haasen et al., 2007) for treating opiate dependence, but the evidence specific to homeless populations is yet to be synthesised.

2.4. How the intervention might work

2.4.1. Housing interventions

Access to adequate housing is an end‐all objective of most homeless individuals. The unconditional provision of stable housing that is permanent in tenure, supportive in nature, and scattered across the rental market has been associated with a positive impact on the long‐term residential stability of homeless individuals (Aubry et al., 2016; Tsemberis et al., 2004). As well, synchronising the provision of permanent housing with supportive services is found to improve social functioning and quality of life (Aubry et al., 2016; Stergiopoulos et al., 2015).

Another model of providing PSH is to congregate accommodation units with supportive services in a single location that may be situated in a residential or commercial area and equipped with commonly used facilities. Such models were found to positively improve the housing and health‐related outcomes of homeless individuals, as per the scattered model (Somers et al., 2017).

2.4.2. Income assistance interventions

Financial hardships halt all efforts to end the cycle of homelessness (Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Health Care for Homeless People, 1988). Evidence suggests that increasing income is an effective strategy to improve both access to health services and health status (Lagarde et al., 2009). This correlation may, very well, be the result of reduced financial stressors and increased ability to afford fundamental life necessities, such as housing, food, and medications (Richards et al., 2008). Moreover, it was found that providing information on income‐assistance resources has the potential to improve the physical and psychosocial health of disadvantaged populations (Adams et al., 2006).

2.4.3. SCM and peer support

Standard case management

Regardless of the heterogeneity and complexity of case‐management models, literature suggests that case management is associated with improved residential stability and substance‐use outcomes (De Vet, 2013). Patients who are provided with the services of a case manager are more likely to feel supported and guided in their quest to access and maintain fundamental health and social services (Conrad et al., 1998).

Peer support

The peer‐support model employs workers with shared life experiences to provide social support, advocacy, education, and role modelling to homeless individuals (Barker & Maguire, 2017). Among homeless populations, these elements have been found to improve quality of life and reduce problematic substance use (Barker & Maguire, 2017).

2.4.4. Mental health interventions

Assertive community treatment

Evidence suggests that individuals experiencing homelessness may benefit from receiving support in the form of ACT. This model of care is found to reduce days on the street or hospitalised, increase community functioning, and improve life satisfaction and mental‐health‐related outcomes for this vulnerable population (Coldwell & Bender, 2007; De Vet, 2013). The positive impact of this model of care could be attributed to the strength of the provider‐service‐user relationship and the sincere effort of the multidisciplinary team providing the care (Stuart, 2009).

Intensive case management

Critical time intervention

The benefit of CTI lies in its ability to prevent the discontinuity of care during periods of transition. Providing CTI to homeless individuals was associated with increased residential stability, decreased mental‐health symptomatology and strengthened ties with services, family, and friends (De Vet, 2013; Jones et al., 2003).

Injectable antipsychotics

Injectable antipsychotics have been found to be effective for managing serious mental illnesses and reducing episodes of mental‐health emergencies (Llorca et al., 2013).

2.4.5. Interventions for substance use

Supervised consumption facilities

There is increasing evidence suggesting the benefit of SCFs in reducing precarious substance‐use‐related public behaviours and increasing access to and maintenance of treatment services (Kennedy et al., 2017; Wood et al., 2007). These facilities are believed to provide a safe environment for accessible services that provide nonjudgemental staff who help connect clients to health and social services as needed.

Managed alcohol programmes

MAPs follow a harm‐reduction approach by providing clients with shelter and regulated alcohol dispensing, accompanied by health and social support as needed (Podymow et al., 2006). The scarce literature on these interventions among homeless individuals suggest its effectiveness in reducing alcohol intake, hospitalisations and incarcerations (Podymow et al., 2006).

Pharmacological interventions for opioid use disorder

Opioid agonist therapy (OAT) such as methadone, buprenorphine/naloxone, and oral morphines have been associated with decreased mortality and morbidity (British Columbia Centre on Substance Use, 2017). As well, evidence suggests that opioid antagonist therapy such as naltrexone is successful in mitigating overdose‐related mortalities and incarceration rates (Roozen et al., 2006).

2.5. Why it is important to do this review

There has been a long‐standing social discourse on effectively tackling the negative consequences of the urban homelessness that has plagued communities internationally. Persons with lived experience of homelessness face higher rates of infectious and chronic disease and disproportionately poorer outcomes, with reduced rates of access to effective quality care. In order to better understand the needs and resources available for people with lived experience of homelessness, policymakers, practitioners, and allied health professionals need high‐quality systematic reviews and knowledge‐translation strategies on interventions that are specific to this population. Our review aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the benefits and cost‐effectiveness of interventions designed to indirectly or directly improve the health and well‐being of persons with lived experience with homelessness. We present updated perspectives on the effect of PSH, income assistance, SCM/peer support and mental‐health and substance‐use interventions, on the housing stability, mental health, quality of life, hospitalisations, earned income and employment statuses of persons with lived homelessness. This review is part of a series of other publications that inform a national practice guide on homelessness (Pottie et al., 2020), and serves to provide best‐practice updates to health‐care professionals and policymakers and guide the future care of persons with lived experiences of homelessness.

3. OBJECTIVES

The objective of this systematic review is to identify, appraise, and synthesise the best available evidence on the effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of interventions to improve the health and social outcomes of people experiencing homelessness and those who are vulnerably housed. Our outcomes of interest include housing stability, mental health, quality of life, substance use, hospitalisations, employment and income. The following research questions were developed to guide the formation of the systematic review:

-

1.

What is the effectiveness of PSH on the health and social outcomes of people experiencing homelessness and those who are vulnerably housed?

-

2.

What is the effectiveness of income assistance on the health and social outcomes of people experiencing homelessness and those who are vulnerably housed?

-

3.

What is the effectiveness of SCM and/or peer support on the health and social outcomes of people experiencing homelessness and those who are vulnerably housed?

-

4.

What is the effectiveness of mental‐health interventions (ACT, ICM, CTI and injectable antipsychotics) on the health and social outcomes of people experiencing homelessness and those who are vulnerably housed?

-

5.

What is the effectiveness of interventions for substance use (SCFs, MAPs and pharmacological interventions for opioid use disorder) on the health and social outcomes of people experiencing homelessness and those who are vulnerably housed?

-

6.

What are the costs and cost‐effectiveness of the aforementioned interventions for people experiencing homelessness and those who are vulnerably housed?

4. METHODS

4.1. Criteria for considering studies for this review

4.1.1. Types of studies

The protocol was registered with the Campbell Collaboration (Pottie et al., 2019) and reported according to the preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta‐analyses for protocols (PRISMA‐P; Moher et al., 2015). The results of the review are reported using the PRISMA reporting guidelines (Moher et al., 2009).

We included studies as recommended by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Cochrane group for reviews of effectiveness (Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC)‐Cochrane, 2015). We included randomised control trials (RCTs), non‐RCTs, controlled before‐after studies, interrupted time‐series studies, and repeated‐measures studies. We considered studies published in both peer‐reviewed journals and grey literature.

4.1.2. Types of participants

We included populations experiencing homelessness, defined as those who lack stable, permanent, appropriate housing, or who may be without immediate prospects, means, and ability to acquire it. Such physical living situations can include emergency shelters or provisional accommodations (Canadian Definition of Homelessness, 2017). Studies must have reported whether participants were experiencing homelessness in order to be included in this review. We included studies that included a subset of the sample experiencing homelessness as long as 50% of the participants were homeless. We included studies that were among individuals or families and we did not restrict our inclusion criteria by age, sex or gender. We excluded studies that were specific to indigenous populations experiencing homelessness, as this line of inquiry is being pursued by an indigenous‐specific research team (Thistle & Smylie, 2020). We excluded all other populations.

4.1.3. Types of interventions

We included the following interventions, as outlined in Section 1.1.2: PSH: income assistance, SCM, ICM, ACT, CTI, peer support, SCFs, MAPs, injectable antipsychotics, and OAT. We included studies that had multicomponent interventions as long as one of the interventions applied to those mentioned above.

All of the included interventions were either compared to an inactive control (i.e., a placebo, no treatment, standard care) or to an active control intervention (alternative or variant of the intervention; Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC)‐Cochrane, 2015). In the case of an interrupted time series, the control must have been a historical control with three data points. If a study with more than two intervention arms was included, then we only included the intervention and control arms that met the eligibility criteria.

4.1.4. Types of outcome measures

Studies were included in this review if they reported the use of validated measures and reported at least one of the following outcomes.

Primary outcomes

-

1.

Housing stability: Any measures assessing participants housing status, such as the number of days in stable housing, number of days homeless (on the street or in shelters), number of participants in stable housing, and number of participants homeless (on the street or in shelters). Typical tools to measure housing stability include the Residential Timeline Followback Inventory (RTLFB) (Tsemberis et al., 2007).

Secondary outcomes

-

2.

Mental health: any measures assessing psychological status and wellbeing, including but not limited to, psychological distress, self‐reported mental health status, or mental illness symptoms. Typical tools to measure mental health include the Colorado Symptom Index (CSI) (Boothroyd & Chen, 2008), and the self reported mental status SF‐12 (Nelson et al., 2012).

-

3.

Quality of life: which include any assessment of well‐being, life and personal satisfaction, quality of social relationships, and any specific physical or mental quality of life measures. Typical tools to measure quality of life include the Lehman Quality of Life Interview (Lehman et al., 1996), and the EuroQoL 5‐D scale (Lamers et al., 2006).

-

4.

Hospitalisation: any measures of participants' use of hospital and emergency services, such as the number of days hospitalised or number of visits to the emergency department. Such measures can be assessed through a standard questionnaire asking participants for their service use, or through accessing the hospital data sets.

-

5.

Substance use: As measured by the number of days using alcohol or substance, the rate and frequency of using alcohol or substances, number of days of abstinence from alcohol or substances or physical and mental consequences of using alcohol or substances. Typical tools to measure substance use outcomes include the Global Appraisal of Individual Needs‐Short Screener of Substance Use Problems GAIN‐SS (Dennis et al., 2006).

-

6.

Income: Any measures of money that participants acquire from different resources including social assistance, disability benefits, donations, and part or full time employment. Such measures can be assessed through a standard questionnaire asking participants for their weekly, monthly or annual income from different sources.

-

7.

Employment: Any measures of employment that participants partake during the study period, including but not limited to, number of days of paid employment, number of employed or unemployed participants, hourly wage, and employment tenure. Such measures can be assessed through a standard questionnaire asking participants about their employment rates during the study period.

-

8.

Economic outcome: any measures of cost, cost benefit, cost utility or incremental cost‐effectiveness ratio. Such measures can be obtained from administrative databases and cost reports. An example of how an individualised programme cost could be calculated is dividing the sum of all on‐site operation and services costs (maintenance, utilities, insurance, etc.) by the capacity of the project (Larimer, 2009).

Duration of follow‐up

All durations of follow‐up were included. We collected data at each available time‐point.

Types of settings

We included studies where the intervention took place in any setting where the primary care of people experiencing homelessness takes place. Primary care is known as the “entry point to the larger health care system” (Tarlier, 2007) and can be provided by professionals from many disciplines, such as family physicians, psychiatrists, social workers, emergency physicians, and so forth. We also included community‐based interventions provided in social‐service or shelter/supervised consumption locations, private or nonprivate clinics, hospital emergency rooms, outreach care, street patrols, mobile care units, and so forth.

We included studies that occurred in high‐income countries and excluded studies that occurred in low‐ and middle‐income countries (World Bank, 2019).

4.2. Search methods for identification of studies

We searched for relevant literature in consultation with an information specialist (librarian).

4.2.1. Electronic searches

We searched the following bibliographic databases from database inception to February 10, 2020:

Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In‐Process & Other Non‐Indexed Citations, Daily and Versions(R) (1946 to February 7, 2020)

EBM Reviews—Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (January 2020)

EBM Reviews—Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2005 to February 4, 2020)

EBM Reviews—Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (1st Quarter 2016)

EBM Reviews—Health Technology Assessment (4th Quarter 2016),

EBM Reviews—NHS Economic Evaluation Database (1st Quarter 2016)

Embase (1974 to February 7, 2020)

EBSCO CINAHL (–2020)

EBSCO PsycINFO (–2020)

Epistemonikos (–2020)

We used a combination of subject headings and keywords including “homeless”, “marginalized” and “shelter”. Full strategies for each database can be found in Appendix A.

4.2.2. Searching other resources

The reference lists of all articles selected for full‐text review were manually searched for relevant citations. These were cross‐referenced against our original search results and any additional potentially relevant citations were screened. Further, we consulted content experts for any publications or resources that might enrich our findings and we screened their suggestions against our inclusion criteria.

4.3. Data collection and analysis

We collected and analysed data according to our protocol (Pottie et al., 2019).

4.3.1. Selection of studies

Teams of two reviewers independently screened titles and abstracts in duplicate. We pilot tested the screening criteria at both the title‐and‐abstract‐screening stage and the full‐text stage. We used the PRISMA flow diagram to report the eligibility of studies. We retrieved the full text of all of the studies that passed this first‐level screening. The full‐text reviews were also done in duplicate by two reviewers, and agreement was reached by consensus. Disagreements were resolved by consultation with a third reviewer.

4.3.2. Data extraction and management

We developed a standardised extraction sheet for each topic variable and created a table of characteristics to describe a summary of findings from our included studies. The data extraction sheet was piloted by two independent reviewers. We collected and utilised all relevant numerical data (SDs, effects estimates, confidence intervals [CIs], test statistics, p values, etc.). Teams of two reviewers extracted data in duplicate and independently. The reviewers compared their results and resolved disagreements by discussion or with help from a third reviewer.

4.3.3. Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias according to guidance for Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) reviews (Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC)‐Cochrane, 2015). Nine standard criteria are suggested for all randomised trials, nonrandomised trials and controlled before‐after studies, including random‐sequence generation, allocation concealment, baseline‐outcome measurements, baseline characteristics, incomplete‐outcome data, knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study, protection against contamination, selective outcome reporting, and other biases.

Risk of bias was assessed by teams of two review authors, in duplicate. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion or by a third reviewer.

It is important to highlight that we did not subject any of the identified economic evaluations to critical appraisal, in accordance with guidance from the Cochrane Handbook (Shemilt et al., 2019).

4.3.4. Measures of treatment effect

Whenever possible, we performed statistical analyses using RevMan 5. For dichotomous data, we used odds ratios (OR) and risk ratios (RR) with 95% CIs. For continuous data, we used the mean difference (MD) with 95% CI, if the outcomes were measured in the same way between trials. We used the standardised mean difference (SMD) with 95% CI to combine the trials that measured the same outcome but used different methods of measurement.

4.3.5. Unit of analysis issues

The results from some studies were reported in multiple publications. Therefore, to prevent the double counting of data, individual records were screened to identify unique studies and were evaluated for potential overlap by comparing the study design, enrolment and data‐collection dates, authors and their associated affiliations, and the reported selection and eligibility criteria. When reviewing multiple publications, we included only unique data from each study. Several studies included outcome data for multiple time points. Comparisons were therefore carried out separately for periods of 6 months and less (short term), 6–18 months (midterm), and 18 months or more (long‐term). If multiple measures of the same outcome were reported, we prioritised outcomes measured using validated scales for meta‐analyses and reported all available outcome data narratively.

4.3.6. Dealing with missing data

We will contact authors once for any missing data. We will use any supplementary data provided by authors in our analysis, or report findings as extracted otherwise.

4.3.7. Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed heterogeneity among studies in two ways. First, we assessed clinical heterogeneity: heterogeneity in population, interventions or outcomes. We used I 2 statistics as a guide to assess heterogeneity along with a visual inspection of forest plots.

4.3.8. Assessment of reporting biases

There were very few outcomes that provided enough data for a meta‐analysis; therefore we could not assess for reporting bias. For future updates, funnel plots would be used if there are 10 or more studies in a meta analysis for one outcome and an investigation would be conducted for reporting biases, for example, publication bias.

4.3.9. Data synthesis

We aimed to conduct a separate meta‐analysis for each outcome and intervention. We assessed clinical heterogeneity by considering the study population, intervention, comparison, outcome measure, and timing of outcome assessment. The assessments were made in consultation with members of the research team with clinical and statistical expertise. We pooled data from studies we judged to be clinically homogeneous. If more than one study provided usable data in any single comparison, we performed a meta‐analysis. We standardised all the reported effect sizes as RRs for the dichotomous outcomes and MDs or SMDs for the continuous outcomes. For the majority of findings, characteristics of studies (such as study designs, intervention types, or outcomes) were too diverse to yield a meaningful summary estimate of effect. Similarly, we deemed forest plots of single studies to be of limited value to the review. When heterogeneity precluded a meta analysis, we synthesised our findings narratively as recommended by the synthesis without meta‐analysis (SWiM) reporting guideline (Campbell et al., 2020).

4.3.10. Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Based on the availability of the data, we had planned to conduct subgroup analyses for the following subgroups: women, youth, and people with disabilities. However, since very few studies were included in each comparison within the review, we could not conduct any of the aforementioned subgroup analyses.

4.3.11. Sensitivity analysis

We had planned to conduct sensitivity analyses; however, since very few studies for each intervention were included in the review, we could not conduct any sensitivity analyses.

4.3.12. Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

We assessed the certainty of evidence for housing‐stability outcomes by using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations) approach (Balshem et al., 2011). Housing‐stability outcomes were selected as critical patient‐important outcomes by our review team, in consultation with content experts and people with lived experience of homelessness. GRADE rates certainty of evidence are as follows:

| Certainty of evidence | Definition |

|---|---|

| High | There is a lot of confidence that the true effect lies close to that of the estimated effect |

| Moderate | There is moderate confidence in the estimated effect: The true effect is likely to be close to the estimated effect, but there is a possibility that it is substantially different |

| Low | There is limited effect on the estimated effect: The true effect might be substantially different from the estimated effect |

| Very low | There is very little confidence in the estimated effect: The true effect is likely to be substantially different from the estimated effect |

5. RESULTS

5.1. Description of studies

We included 86 studies, described below.

5.1.1. Results of the search

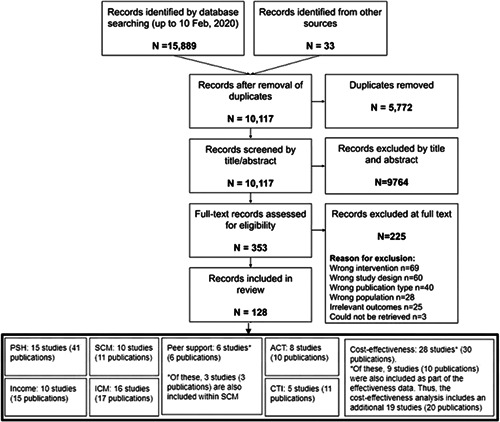

The search was performed from database inception up to February 10, 2020. The search resulted in 15,889 citations, and an additional 33 were identified from other sources. After removal of duplicates we screened 10,117 unique citations by title and abstract, leaving 353 citations that were potentially eligible for inclusion in this review. Full‐text reviews of these works identified 128 citations for inclusion in this review. Figure 2 depicts the search‐and‐selection flow diagram.

Figure 2.

PRISMA flow diagram

5.1.2. Included studies

We included a total of 86 studies (128 publications), broken down by the interventions below:

Permanent supportive housing

We included 15 studies (41 publications) examining the effectiveness of PSH (Aubry et al., 2016; Cherner et al., 2017; Goldfinger et al., 1999; Hwang et al., 2011; Lipton et al., 1988; Martinez & Burt, 2006; McHugo et al., 2004; Rich & Clark, 2005; Sadowski et al., 2009; Siegel et al., 2006; Stefancic & Tsemberis, 2007; Stergiopoulos et al., 2015; Stergiopoulos et al., 2019; Tsemberis et al., 2004; Young et al., 2009). Four studies were conducted in Canada (Aubry et al., 2016; Cherner et al., 2017; Hwang et al., 2011; Stergiopoulos et al., 2019) and the remaining were conducted in the United States. All studies provided PSH with either ACT or ICM, depending on the severity of the mental‐health symptoms and participants' needs. PSH models included scattered‐site and congregate settings. All interventions were delivered to individuals and no studies were specific to families, women or youth.

Income assistance

We included 10 studies (15 publications) examining the effectiveness of income‐assistance interventions (Booshehri, 2017; Ferguson, 2018; Forchuk et al., 2008; Gubits et al., 2018; Hurlburt et al., 1996; Kashner, 2002; Pankratz et al., 2017; Poremski et al., 2015; Rosenheck et al., 2003; Wolitski, 2009). Five studies investigated the impact of housing subsidies with (Hurlburt et al., 1996; Pankratz et al., 2017; Rosenheck et al., 2003; Wolitski, 2009) or without (Gubits et al., 2018) case management. One study offered assistance finding housing and rental supplements (Forchuk et al., 2008) and the remaining four studies assessed the effectiveness of financial education (Booshehri, 2017), compensated work therapy (CWT; Kashner, 2002), or individual‐placement support (IPS; Ferguson, 2018; Poremski et al., 2015). Two studies were conducted among families (Booshehri, 2017; Gubits et al., 2018) and one among youth (Ferguson, 2018). Three studies were conducted in Canada (Forchuk et al., 2008; Pankratz et al., 2017; Poremski et al., 2015) and the remaining seven took place in the United States.

Standard case management

We included 10 studies (11 publications) examining the effectiveness of SCM (Conrad et al., 1998; Graham‐Jones et al., 2004; Hurlburt et al., 1996; Lapham et al., 1996; Nyamathi et al., 2001; Nyamathi et al., 2016; Sosin et al., 1995; Towe et al., 2019; Upshur et al., 2015; Weinreb et al., 2016). All studies were conducted among populations either experiencing or at‐risk for homelessness, with varying degrees of need. Three studies were specific to women (Nyamathi et al., 2001; Upshur et al., 2015; Weinreb et al., 2016); two were specific to men (Conrad et al., 1998; Nyamathi et al., 2016), and five contained mixed‐gender populations (Graham‐Jones et al., 2004; Hurlburt et al., 1996; Lapham et al., 1996; Sosin et al., 1995; Towe et al., 2019). Most (n = 9) studies were set in the United States and one study was conducted in the United Kingdom (Graham‐Jones et al., 2004). The interventions focused on care coordination, including links to primary care (Graham‐Jones et al., 2004; Nyamathi et al., 2001; Weinreb et al., 2016), housing (Hurlburt et al., 1996; Sosin et al., 1995), mental‐health counselling (Lapham et al., 1996; Upshur et al., 2015), and skills provision, such as relapse prevention skills (Conrad et al., 1998), infectious‐disease risk reduction (Nyamathi et al., 2001), and coping skills (Nyamathi et al., 2016). Two studies also included peers with lived experience in their intervention delivery (Nyamathi et al., 2001; Nyamathi et al., 2016).

Peer support

We included six studies (six publications) examining the effectiveness of peer‐support interventions (Corrigan et al., 2017; Ellison et al., 2020; Lapham et al., 1996; Nyamathi et al., 2001; Nyamathi et al., 2016; Yoon et al., 2017). Of these, three studies were three‐arm trials where the third arm is also included under SCM (Lapham et al., 1996; Nyamathi et al., 2001; Nyamathi et al., 2016). All studies were conducted in the United States. In four studies, peers played the role of navigators and mentors, providing training in effective coping skills, self‐management, goal‐setting and assistance in navigating the health‐care and social‐care systems (Corrigan et al., 2017; Nyamathi et al., 2001; Nyamathi et al., 2016; Yoon et al., 2017). Two studies integrated peers into housing programmes, where peers offered support services focused on mental health and substance‐use recovery and community integration (Ellison et al., 2020; Lapham et al., 1996).

Intensive case management

We included 16 studies (17 publications) examining the effectiveness of ICM (Braucht, 1995; Burnam, 1995; Cauce, 1994; Clark & Rich, 2003; Cox et al., 1998; Felton et al., 1995; Grace & Gill, 2014; Korr & Joseph, 1996; Malte et al., 2017; Marshall et al., 1995; Orwin et al., 1994; Rosenblum et al., 2002; Shern et al., 2000; Shumway et al., 2008; Stahler et al., 1995; Toro et al., 1997). Most studies were conducted among homeless individuals with mental illness and/or substance‐use problems, with two studies conducted among adolescents and young adults (Cauce, 1994; Grace & Gill, 2014) and one conducted among adults with children (Toro et al., 1997). Fourteen studies were conducted in the United States, one study was conducted in the United Kingdom (Marshall et al., 1995) and one in Australia (Grace & Gill, 2014). All interventions had a low caseload (12–20 clients) and one intervention included peers with lived experience (Felton et al., 1995).

Assertive community treatment

We included 8 studies (10 publications) examining the effectiveness of ACT (Clarke et al., 2000; Essock et al., 1998, 2006; Fletcher et al., 2008; Lehman et al., 1997; Morse et al., 1992, 1997, 2006). All studies were conducted among homeless adults, in the United States, who had serious and persistent mental illness. All participants received care from a multidisciplinary team that included a psychiatrist. Two studies also integrated a substance‐abuse specialist to their staff (termed “Integrated Assertive Community Treatment” [IACT]) (Fletcher et al., 2008; Morse et al., 2006). Three studies also included peers with lived experience of homelessness and/or poor mental health (often termed “consumers”, “consumer advocates” or “community workers”) in their ACT teams (Clark et al., 1998; Lehman et al., 1997; Morse et al., 1997).

Critical time intervention

We included five studies (11 citations) examining the effectiveness of CTI (De Vet et al., 2017; Herman et al., 2011; Lako et al., 2018; Shinn et al., 2015; Susser et al., 1997). Four studies were conducted among single adults and one study was conducted among families with children (Shinn et al., 2015). One study was conducted following participants' hospital discharge (Herman et al., 2011) and the remaining four studies were conducted while participants were residing in shelters. Two studies were conducted in the Netherlands (De Vet, 2017; Lako et al., 2018) and the other three were conducted in the United States. All CTI interventions followed the same three phases: (1) transition to the community, (2) tryout and (3) transfer of care.

Supervised consumption facilities

We did not identify any eligible studies on SCFs (empty review).

Managed alcohol programmes

We did not identify any eligible studies on MAPs (empty review).

Injectable antipsychotics

We did not identify any eligible studies on injectable antipsychotics (empty review).

Opioid agonist therapy

We did not identify any eligible studies on OATs (empty review).

Cost‐effectiveness

We identified 30 publications that reported on the cost‐effectiveness of our interventions (Aubry et al., 2016; Chalmers McLaughlin, 2011; Clark et al., 1998; Culhane et al., 2002; Dickey et al., 1997; Essock et al., 1998; Evans et al., 2016; Gilmer et al., 2009, 2010; Holtgrave et al., 2013; Hunter et al., 2017; Larimer, 2009; Latimer et al., 2019; Lehman, 1999; Lenz‐Rashid, 2017; Lim et al., 2018; Mares & Rosenheck, 2011; Morse et al., 2006; Nyamathi et al., 2016; Okin et al., 2000; Pauley et al., 2016; Rosenheck et al., 2003; Sadowski et al., 2009; Schinka et al., 1998; Shumway et al., 2008; Srebnik et al., 2013; Stergiopoulos et al., 2015; Susser et al., 1997; Tsemberis et al., 2004; Wolff, 1997). Of these, 10 publications were also included as part of the effectiveness data (Aubry et al., 2016; Essock et al., 1998; Morse et al., 2006; Nyamathi et al., 2016; Rosenheck et al., 2003; Sadowski et al., 2009; Shumway et al., 2008; Stergiopoulos et al., 2015; Susser et al., 1997; Tsemberis et al., 2004). Thus, the cost‐effectiveness analysis includes an additional 19 studies (20 publications). Eighteen of these studies took place in the United States, and only one examined cost‐effectiveness in the Canadian context (Latimer et al., 2019).

Twenty‐one publications provided cost‐effectiveness data on PSH and/or income‐assistance interventions (Aubry et al., 2016; Chalmers McLaughlin, 2011; Culhane et al., 2002; Dickey et al., 1997; Evans et al., 2016; Gilmer et al., 2009, 2010; Holtgrave et al., 2013; Hunter et al., 2017; Larimer, 2009; Latimer et al., 2019; Lenz‐Rashid, 2017; Lim et al., 2018; Mares & Rosenheck, 2011; Pauley et al., 2016; Rosenheck et al., 2003; Sadowski et al., 2009; Schinka et al., 1998; Srebnik et al., 2013; Stergiopoulos et al., 2015; Tsemberis et al., 2004). Of these, five publications also provided effectiveness data (Aubry et al., 2016; Rosenheck et al., 2003; Sadowski et al., 2009; Stergiopoulos et al., 2015; Tsemberis et al., 2004).

For mental‐health interventions, twelve articles provided evidence on cost‐effectiveness: three on SCM (Nyamathi et al., 2016; Okin et al., 2000; Shumway et al., 2008), 6 on ACT (Aubry et al., 2016; Clark et al., 1998; Essock et al., 1998; Lehman, 1999; Morse et al., 2006; Wolff, 1997), 2 on ICM (Rosenheck et al., 2003; Stergiopoulos et al., 2015); and 1 for CTI (Susser et al., 1997). Eight of the mental‐health cost‐effectiveness articles were also included in the effectiveness analysis (Aubry et al., 2016; Essock et al., 1998; Nyamathi et al., 2016; Morse et al., 2006; Rosenheck et al., 2003; Shumway et al., 2008; Stergiopoulos et al., 2015; Susser et al., 1997).

No cost‐effectiveness studies were identified for the other interventions (peer support, SCFs, MAPs, injectable antipsychotics and OAT).

5.1.3. Excluded studies

The search process is diagrammed in Figure 2, which also shows the number of records excluded (n = 225), along with a summary of reasons. Further details of the excluded studies are also available in Excluded studies.

5.2. Risk of bias in included studies

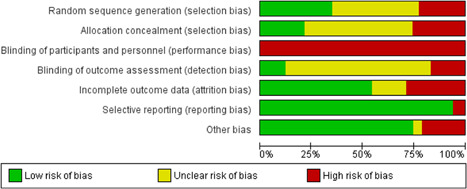

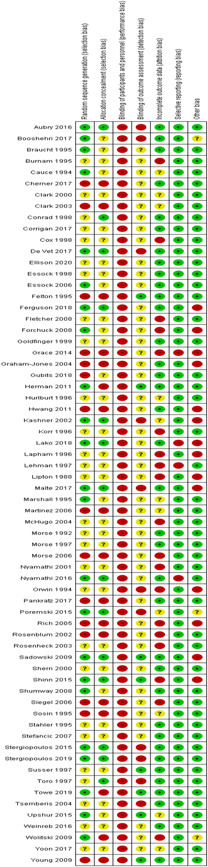

We judged there to be a moderate or high risk of bias in most categories in each of the studies reviewed, see Figure 3 for a summary of judgements on bias across the studies reviewed. Figure 4 provides an insight into the level of potential bias within each study. Characteristics of included studies provides the rationale for each of these judgements. Furthermore, given that the risk of bias associated with economic evaluations differs from that associated with standard RCTs, we did not critically appraise these studies using a standardised tool.

Figure 3.

Risk of bias summary

Figure 4.

Risk of bias in individual studies

5.2.1. Allocation (selection bias)

Selection bias occurs in intervention studies when there are systematic differences between comparison groups in response to treatment or prognosis (Henderson & Page, 2007). Intervention studies are especially susceptible to selection bias unless particular efforts are made to minimise it. The most effective method is random allocation to treatment and control groups. We included both randomised and nonrandomised trials of interventions in our review. As a result, 15 studies were assessed as having high risk of selection bias due to inadequate or absent random sequence generation, while 28 studies had unclear risk of bias on this item. Concerns with allocation concealment were similar, with only 14 deemed as low risk of bias.

5.2.2. Blinding (performance bias and detection bias)

This potential bias is counteracted by the blinding of study participants and personnel, so that they are unaware of their group assignment, and the blinding of outcome assessors. Given the nature of the interventions and the impossibility of blinding of participants, all studies were assessed as high risk for performance bias. Blinding of outcome assessors was often poorly described in our included studies, resulting in the majority of studies having unclear risk of detection bias. Eleven studies did not blind their outcome assessors (assessed as high risk of bias), resulting in only eight studies having low risk of detection bias.

5.2.3. Incomplete outcome data (attrition bias)

Attrition bias refers to the biasing effect of study participants, or study participant data becoming unavailable during the study. This bias can be counteracted by keeping accurate records of participants who drop out of the study, and by using intention‐to‐treat analysis so that drop‐outs do not have a biasing effect on final results. Nineteen studies had high risk for attrition bias, while 11 studies had unclear risk of bias on this item.

5.2.4. Selective reporting (reporting bias)

This bias refers to the selection of a subset of the original recorded outcomes, on the basis of the results, for inclusion in publication. Evidence of this bias was assessed by examining studies for an existing protocol. Among included studies, only four studies had high risk of bias on this item.

5.2.5. Other potential sources of bias

We considered publication bias and funding source bias as other potential sources of bias. Seventeen studies had unclear or high risk of the presence of these other biases.

5.3. Effects of interventions

5.3.1. Permanent supportive housing

Primary outcome: Housing stability

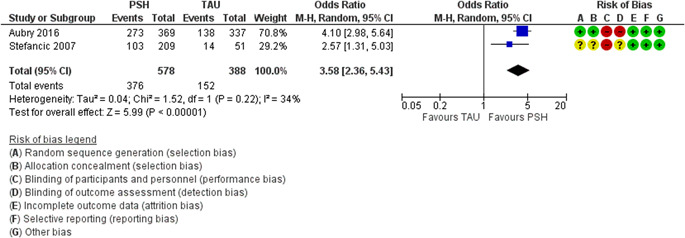

The effect of PSH on housing stability was examined in 15 studies (41 citations) (Aubry et al., 2016; Cherner et al., 2017; Goldfinger et al., 1999; Hwang et al., 2011; Lipton et al., 1988; Martinez & Burt, 2006; McHugo et al., 2004; Rich & Clark, 2005; Sadowski et al., 2009; Siegel et al., 2006; Stefancic & Tsemberis, 2007; Stergiopoulos et al., 2015; Stergiopoulos et al., 2019; Tsemberis et al., 2004; Young et al., 2009). Ten studies were from the United States (Goldfinger et al., 1999; Lipton et al., 1988; Martinez & Burt, 2006; McHugo et al., 2004; Rich & Clark, 2005; Sadowski et al., 2009; Siegel et al., 2006; Stefancic & Tsemberis, 2007; Tsemberis et al., 2004; Young et al., 2009) and 5 were from Canada (Aubry et al., 2016; Cherner et al., 2017; Hwang et al., 2011; Stergiopoulos et al., 2015; Stergiopoulos et al., 2019). Between the 15 studies, follow‐up ranged from 6 months to up to 6 years. Eight studies were RCTs, 1 was an extension of a multicentre RCT, 5 were quasi‐experimental trials and 1 was a controlled before‐and‐after study. Almost all trials included mental illness within the study's inclusion criteria, and many participants also had comorbid substance‐abuse disorders. Due to heterogeneity in the outcome measures and the time points measured, it was not possible to complete a meta‐analysis of all of the studies. However, data analysis from the Canadian At‐Home Chez‐Toi and US Pathways trials were pooled and is presented in Analysis 1.1 (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

(Analysis 1.1) Figure 3. Forest plot of meta‐analysis comparing PSH to TAU on number of days in stable at 18 months or later. PSH, permanent supportive housing; TAU, treatment as usual

Overall, most studies (n = 10) demonstrated significant short‐ and/or long‐term benefits of PSH on housing stability (Aubry et al., 2016; Cherner et al., 2017; Lipton et al., 1988; Martinez & Burt, 2006; Sadowski et al., 2009; Stefancic & Tsemberis, 2007; Stergiopoulos et al., 2015; Stergiopoulos et al., 2019; Tsemberis et al., 2004; Young et al., 2009). One study showed that PSH had a benefit not only in improving the number of days spent in stable housing but also in similar improvements in residential stability over time, compared to treatment as usual (TAU). Of note, however, is that this study did have an unexpectedly large number of participants who were already in stable housing prior to enrolment in the study (Hwang et al., 2011). Of the 15 studies evaluating housing stability, one found no difference with supportive housing (Siegel et al., 2006) and another favoured staffed group homes over independent living, though only for minority groups (Goldfinger et al., 1999). An additional study found differing results, based on interaction with gender (Rich & Clark, 2005). In one study that examined hybrid models of housing, integrative services were found to have improved residential stability compared to parallel housing (McHugo et al., 2004).

Pooled data from the multicity Canadian At Home‐Chez Toi (n = 2148) and US Pathways (n = 225) trials found that an increased number of participants remained in stable housing within the PSH intervention group, compared to TAU, with an OR of 3.58; 95% CIs, 2.36, 5.43 (GRADE certainty of evidence: Moderate) (Aubry et al., 2016; Tsemberis et al., 2004). Both trials were RCTs, enlisting participants with serious mental illness, and were based on the “Pathways to Housing” Housing First (HF) Model, which involved providing participants with scattered‐site apartments alongside ACT or ICM (Aubry et al., 2016). The At Home‐Chez Toi initiative found that over the 2‐year follow up period, participants in the intervention arm spent 73% of the time in stable housing, compared to 32% in the TAU group (Aubry et al., 2016). The individuals who obtained stable housing also moved into housing more rapidly than the TAU participants (72.9 vs. 219.7 days, AAD = 146.4, CI, 118.0–174.9, p < .001). Long‐term analysis of a single site of the At Home‐Chez Toi study, in Toronto, Canada, found that the number of days spent stably housed remained significantly higher in participants in the HF groups than participants in the TAU groups, at all time points, with a median duration of follow up of 5.4 years (Stergiopoulos et al., 2019). The Pathways to Housing Project, based in New York City, similarly found that participants in the intervention group experienced faster reductions in their homelessness statuses and increased their housing stability relative to participants in TAU (F‐4137 = 10.1, p < .001; F 4137 = 27.7, p < .001) over a 2‐year follow‐up period, with an approximately 80% housing‐retention rate. Over 90% of participants in this study had coexistent SUDs (including alcohol) in conjunction with severe mental illness (Tsemberis et al., 2004).

Several other studies also showed improvements in housing status with supportive housing compared to TAU (Cherner et al., 2017; Lipton et al., 1988; Martinez & Burt, 2006; Sadowski et al., 2009; Stefancic & Tsemberis, 2007; Young et al., 2009). Among homeless individuals (n = 236) with a high prevalence of mental illness (86%) and SUDs (91%) in a study out of San Francisco, 81% of participants remained in supportive housing for at least 1 year, 63% for at least 2 years, and 48% for at least 3 years (Martinez & Burt, 2006). A Canadian study in Ottawa found improved rates of housing retention at 2 years in the HF Group (76% vs. 50.8%, p < .001) in participants with problematic substance use (n = 178), with the HF intervention group demonstrating higher housing stability and decreased time to move into housing, compared to the TAU group (MD −68.73 days, 95% CI, −125, −12.08, p < .05) (Cherner et al., 2017). However, another Canadian quasi‐experimental study from Toronto (n = 112) had mixed findings; participants in supportive housing had spent significantly more days in stable housing in the 6 months prior to the study, compared to the TAU group (F1,87 = 15.65, p < .01), but residential stability over time improved equally between the two groups. A large number of participants had already been in stable housing before their study enrolment and independent assignment into groups; only five participants remained homeless throughout the study period (Hwang et al., 2011).

In contrast, some studies either showed no difference between PSH or favoured more traditional or a continuum of interventions. Goldfinger et al., (1999) compared the provision of independent housing to staffed group‐home sites and reported a reduction in days spent homeless for staffed group homes over the independent living group, though only for minority groups (Goldfinger et al., 1999). Another quasi‐experimental study found no significant difference in the percentage of tenants in initial housing placement (n = 157) at 6, 12 and 18 months, between supportive housing versus community residences reliant on sobriety as a precondition for housing (Siegel et al., 2006). McHugo et al. studied two hybrid approaches to housing, “parallel housing” (resembling supportive housing + ACT) and “integrated housing” (resembling the traditional continuum model, whereby decisions regarding housing are influenced by clinicians), due to cited practical considerations, such as the shortage of safe low‐income housing. Within the parallel‐housing model, ACT teams helped participants to find affordable low‐income housing but did not have control over the housing supply itself. Similar to the PSH model, housing services were not dependent on participant's mental‐health treatment. Within the integrated housing model, a single agency provided both comprehensive mental health and controlled housing but did not necessarily require scattered‐site accommodation; congregate settings were felt to be appropriate for some patients. In this study, though both approaches reduced the incidence of participants obtaining functional housing and increased their time in stable housing, the integrated‐housing approach showed benefits over the parallel‐housing‐services group, in terms of the proportion of days of functional homelessness (group × time F value 0.56, d = −0.52, p < .05) and days in stable housing (group × time F value 1.38, d = 0.51) (p < .05) (McHugo et al., 2004).

Effect of gender

Interestingly, McHugo et al. found that the effect of the group on stable housing interacted with the effect of gender (F 1,107 = 8.32, p = .005,) with males in the parallel‐housing‐services group spending significantly less time in stable housing compared to other groups for whom the outcomes were all approximately equal, specifically for females in parallel housing and males and females in the integrated housing services (McHugo et al., 2004).

The gender effect was also explored by Rich and Clark (2005). In contrast to the above study by McHugo et al, this quasi‐experimental study found that homeless men within the comprehensive housing programme actually improved their time in stable housing (similar to PSH model), as compared to those in specialised case management. Men in the comprehensive housing programme increased their number of days in stable housing by 76 out of an average of 180 days, whereas males in specialised case management increased their housing by only 37 days (a difference of 39 days). Women significantly improved their homelessness in both programmes, but women in the specialised case management had more time stably housed than women in the comprehensive housing programme, likely due to women in comprehensive housing spending more time in psychiatric hospitals (Rich & Clark, 2005).

Adolescents

Two subgroup analyses of the At Home‐Chez Toi study were presented. One subgroup analysis, adjusting for study city and ethnoracial and Aboriginal status, found that homeless youth aged 18–24 in the intervention arm were stably housed for a mean of 65% of days, compared to 31% for the TAU youth (p < .001) (Aubry et al., 2016). The difference in the changes in the mean for housing stability for those aged 18–24 years compared to adults more than 24 years old was nonsignificant. Another analysis comparing older (50 years or older) and younger (18–49 years old) homeless adults demonstrated that HF had a similar effect of housing stability on those in the older and younger age groups at 24 months, compared to the TAU group (Aubry et al., 2016).

Substance Use

The evidence was mixed for the effects of substance use on housing retention. Some studies found there was no relationship between SUD and housing stability (Aubry et al., 2016; Martinez & Burt, 2006) whereas one study found it correlated with more days homeless (Goldfinger et al., 1999) (though this may be because of a relatively small number of participants, in the sample, without SUD). A subanalysis of the multicity Canadian At Home‐Chez Toi study found that people with SUD spent less time in stable housing in both the HF and TAU groups but that the HF initiative improved housing stability equally among participants with and without SUD (OR 1.17, 95% CI, −0.77, 1.76) (Aubry et al., 2016). A 5‐site (4 city) study in the United States found that, depending on the treatment site, the effect of intervention varied with substance abuse (Goldfinger et al., 1999).

Outcome 2: Mental health

Eleven studies examined the effects of PSH on mental health (Aubry et al., 2016; Cherner et al., 2017; Hwang et al., 2011; Lipton et al., 1988; McHugo et al., 2004; Rich & Clark, 2005; Sadowski et al., 2009; Siegel et al., 2006; Stergiopoulos et al., 2015; Tsemberis et al., 2004; Young et al., 2009). Only one study showed a benefit of PSH, over the TAU, on mental‐health outcomes (Rich & Clark, 2005) In three studies, psychiatric symptoms were somewhat improved in the comparison group, compared to supportive housing (Aubry et al., 2016; Cherner et al., 2017; Young et al., 2009). One study examined hybrid housing models and found improved psychiatric symptoms in integrated housing, compared to parallel housing (McHugo et al., 2004).

Most studies (n = 5) found no significant differences between PSH and TAU (Hwang et al., 2011; Lipton et al., 1988; Sadowski et al., 2009; Stergiopoulos et al., 2015; Tsemberis et al., 2004). Some studies (n = 2) found that mental‐health symptoms decreased over time for both groups, even though there was no group difference between intervention arms (Sadowski et al., 2009; Tsemberis et al., 2004), while two studies (of which one was a moderate‐needs population of the At Home‐Chez Toi study) did not find any significant differences, either with time or between groups (Hwang et al., 2011; Stergiopoulos et al., 2015). One study reported that participants in PSH experienced fewer psychiatric symptoms over time (p < .06) (Rich & Clark, 2005). However, significant differences between the groups, on these measures at baseline, suggest that their initial values may have accounted for these differences.

A few studies (n = 3) found some improved mental‐health symptoms in the comparison group, as opposed to supportive housing (Aubry et al., 2016; Cherner et al., 2017; Young et al., 2009). The multicity At Home‐Chez Toi trial found that though there were improvements in mental‐health symptoms and psychological integration in both groups (pooled SMD 0.70 and pooled SMD 0.53 respectively), the TAU had a small group benefit at final follow‐up (ASMD, 0.17; CI, 0.05–0.30; p = .01) (Aubry et al., 2016). Another 2‐year study of homeless adults with problematic substance use similarly found improved mental‐health symptoms in the TAU group at the end of the study (p < .01) (Cherner et al., 2017).