Abstract

Background

Globally, almost 1.6 billion individuals lack adequate housing. Many accommodation‐based approaches have evolved across the globe to incorporate additional support and services beyond delivery of housing.

Objectives

This review examines the effectiveness of accommodation‐based approaches on outcomes including housing stability, health, employment, crime, wellbeing, and cost for individuals experiencing or at risk of experiencing homelessness.

Search Methods

The systematic review is based on evidence already identified in two existing EGMs commissioned by the Centre for Homelessness Impact (CHI) and built by White et al. The maps were constructed using a comprehensive three stage search and mapping process. Stage one mapped included studies in an existing systematic review on homelessness, stage two was an extensive search of 17 academic databases, three EGM databases, and eight systematic review databases. Finally stage three included web searches for grey literature, scanning reference lists of included studies and consultation with experts to identify additional literature. We identified 223 unique studies across 551 articles from the effectiveness map on 12th April 2019.

Selection Criteria

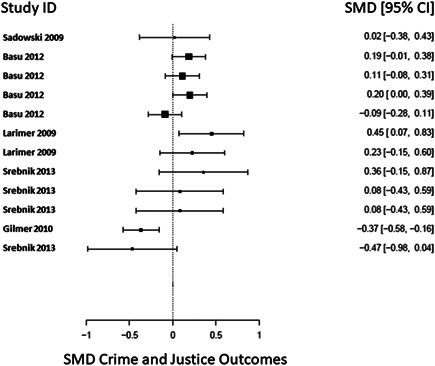

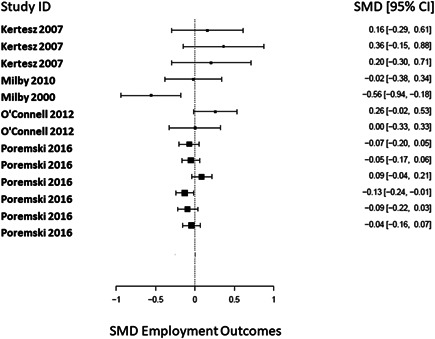

We include research on all individuals currently experiencing, or at risk of experiencing homelessness irrespective of age or gender, in high‐income countries. The Network Meta‐Analysis (NMA) contains all study designs where a comparison group was used. This includes randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐experimental designs, matched comparisons and other study designs that attempt to isolate the impact of the intervention on homelessness. The NMA primarily addresses how interventions can reduce homelessness and increase housing stability for those individuals experiencing, or at risk of experiencing, homelessness. Additional outcomes are examined and narratively described. These include: access to mainstream healthcare; crime and justice; employment and income; capabilities and wellbeing; and cost of intervention. These outcomes reflect the domains used in the EGM, with the addition of cost.

Data Collection and Analysis

Due to the diverse nature of the literature on accommodation‐based approaches, the way in which the approaches are implemented in practice, and the disordered descriptions of the categories, the review team created a novel typology to allow meaningful categorisations for functional and useful comparison between the various intervention types. Once these eligible categories were identified, we undertook dual data extraction, where two authors completed data extraction and risk of bias (ROB) assessments independently for each study. NMA was conducted across outcomes related to housing stability and health.Qualitative data from process evaluations is included using a “Best Fit” Framework synthesis. The purpose of this synthesis is to complement the quantitative evidence and provide a better understanding of what factors influenced programme effectiveness. All included Qualitative data followed the initial framework provided by the five main analytical categories of factors of influence (reflected in the EGM), namely: contextual factors, policy makers/funders, programme administrators/managers/implementing agencies, staff/case workers and recipients of the programme.

Main Results

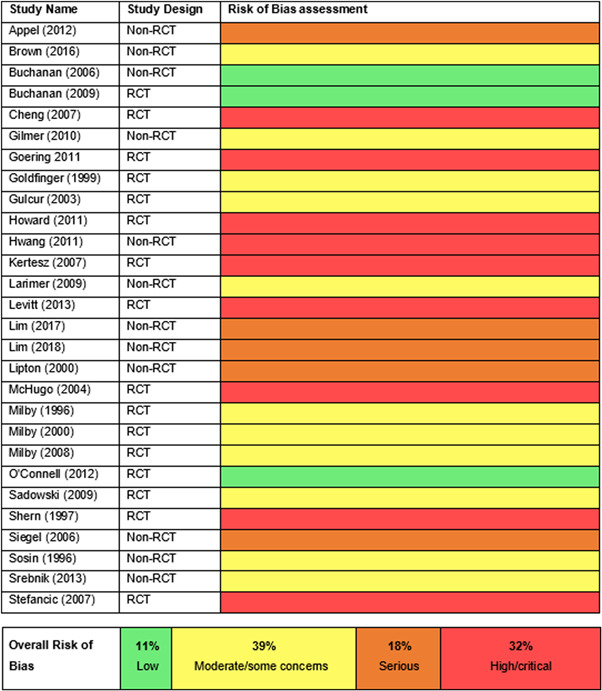

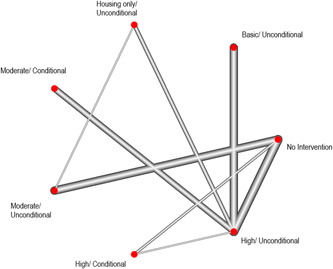

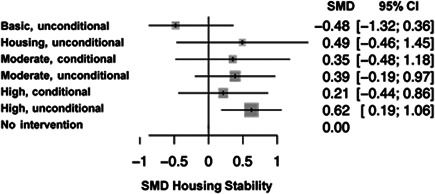

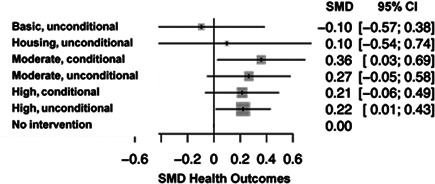

There was a total of 13,128 people included in the review, across 51 reports of 28 studies. Most of the included studies were carried out in the United States of America (25/28), with other locations including Canada and the UK. Sixteen studies were RCTs (57%) and 12 were nonrandomised (quasi‐experimental) designs (43%). Assessment of methodological quality and potential for bias was conducted using the second version of the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for Randomised controlled trials. Nonrandomised studies were coded using the ROBINS‐ I tool. Out of the 28 studies, three had sufficiently low ROB (11%), 11 (39%) had moderate ROB, and five (18%) presented serious problems with ROB, and nine (32%) demonstrated high, critical problems with their methodology. A NMA on housing stability outcomes demonstrates that interventions offering the highest levels of support alongside unconditional accommodation (High/Unconditional) were more effective in improving housing stability compared to basic support alongside unconditional housing (Basic/Unconditional) (ES=1.10, 95% confidence interval [CI] [0.39, 1.82]), and in comparison to a no‐intervention control group (ES=0.62, 95% CI [0.19, 1.06]). A second NMA on health outcomes demonstrates that interventions categorised as offering Moderate/Conditional (ES= 0.36, 95% CI [0.03, 0.69]) and High/Unconditional (ES = 0.22, 95% CI [0.01, 0.43]) support were effective in improving health outcomes compared to no intervention. These effects were smaller than those observed for housing stability. The quality of the evidence was relatively low but varied across the 28 included studies. Depending on the context, finding accommodation for those who need it can be hindered by supply and affordability in the market. The social welfare approach in each jurisdiction can impact heavily on support available and can influence some of the prejudice and stigma surrounding homelessness. The evaluations emphasised the need for collaboration and a shared commitment between policymakers, funders and practitioners which creates community and buy in across sectors and agencies. However, co‐ordinating this is difficult and requires sustainability to work. For those implementing programmes, it was important to invest time in developing a culture together to build trust and solid relationships. Additionally, identifying sufficient resources and appropriate referral routes allows for better implementation planning. Involving staff and case workers in creating processes helps drive enthusiasm and energy for the service. Time should be allocated for staff to develop key skills and communicate engage effectively with service users. Finally, staff need time to develop trust and relationships with service users; this goes hand in hand with providing information that is up to date and useful as well making themselves accessible in terms of location and time.

Authors' Conclusions

The network meta‐analysis suggests that all types of accommodation which provided support are more effective than no intervention or Basic/Unconditional accommodation in terms of housing stability and health. The qualitative evidence synthesis raised a primary issue in relation to context: which was the lack of stable, affordable accommodation and the variability in the rental market, such that actually sourcing accommodation to provide for individuals who are homeless is extremely challenging. Collaboration between stakeholders and practitioners can be fruitful but difficult to coordinate across different agencies and organisations.

1. PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

1.1. Accommodation‐based approaches help people remain healthy and stably housed

Accommodation‐based approaches are mostly effective for increasing housing stability and health outcomes, except for those which offer low support housing without behavioural conditions. These approaches led to worse outcomes related to housing stability and health than receiving nothing at all. Agencies working together and sharing resources such as time and staff creates a commitment to ending homelessness.

1.1.1. What is this review about?

Globally, almost 1.6 billion individuals lack adequate housing. Many accommodation‐based approaches have evolved to incorporate support and services beyond delivery of housing. This review looked at whether these approaches are effective on outcomes including housing stability, health, employment, crime, wellbeing, and cost for individuals experiencing or at risk of experiencing homelessness.

What is the aim of this review?

This Campbell systematic review of qualitative and quantitative evidence examines how useful accommodation‐based approaches are for people experiencing homelessness. The quantitative data summarises evidence from 28 studies, reported in 51 articles, mainly from North America. The qualitative data summarises evidence from 10 articles from high‐income countries.

1.1.2. What studies are included?

The quantitative research provides an overview of effectiveness findings from 28 intervention studies reported in 51 articles of accommodation‐based interventions. Twenty‐five out of the 28 studies are from the United States, two from Canada and one from the UK. The quality of the research is generally low and represents important weaknesses in the evidence base.

The qualitative data presents one evaluation based on an intervention conducted in the UK, two in Ireland, one in Australia, one across Europe and the remaining five carried out in North America; three in the United States and two in Canada. The quality of the evaluations was average and did not directly evaluate the effectiveness interventions discussed in this review.

1.1.3. Do accommodation‐based approaches help people experiencing homelessness?

Interventions which provide the highest levels of support and do not place rules on the person receiving the intervention are best at improving housing stability and health outcomes.

Interventions which offer the lowest levels of support and do not place rules on the person might harm those individuals. For those individuals, housing stability and health outcomes were worse than for all other interventions, including individuals who are not receiving any intervention at all.

1.1.4. What implementation factors affect how well accommodation‐based approaches work?

Staff, resources and time often impacted the delivery of accommodation programmes most. Programme managers knew that members of staff working on the ground took initiative and were capable in their roles. However, they need adequate training and time to build good relations with service users.

There is a tension in funding allocated between new and established services, which can cause issues when services collaborate. It can also impact upon the shared commitment to ending homelessness. Buy‐in at all levels of influence can impact how successful a programme is and how many people experiencing homelessness it can engage with.

1.1.5. What do the findings of this review mean?

Those interventions which are described as Basic/Unconditional (i.e., those that only satisfy very basic human needs such as a bed and food) harm people: meaning they had worse health and housing stability outcomes even when compared to receiving nothing at all. This invites questions on whether these types of accommodation‐based interventions should be discontinued so that other more suitable and effective offers of support can be made available.

Too few studies assess the cost, or important participant characteristics like age and gender. There are also gaps related to where the research is conducted. Most of the studies included are from the United States and Canada which have very different social welfare systems to those of the UK. The process evaluations were conducted in high‐income countries with different housing contexts and social welfare systems.

The studies were of average quality and not connected to the effectiveness studies, which presented issues when drawing connections between the available data. Researchers conducting studies into accommodation‐based interventions should consider evaluating and publishing the factors impacting upon the trial, reflecting on why the intervention did or did not work, and for whom.

1.1.6. How up‐to‐date is this review?

Quantitative studies were downloaded from the effectiveness Evidence and Gap Map on 12 April 2019. Qualitative reports were downloaded from the Process and Implementation Evidence and Gap Map on 10 May 2019.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1. The problem, condition or issue

Homelessness affects individuals who are experiencing life without safe, adequate, or stable housing. Conceived in this way, homelessness not only describes those individuals who are visibly homeless and living on the street, but also those precariously housed individuals who; stay in emergency accommodation, sleep in crowded or inadequate housing, and those who are not safe in their living environment. FEANTSA further classify individuals experiencing homelessness as those who are roofless, those who are houseless and those who experience insecure or inadequate housing (FEANTSA, 2005).

Global data suggests that at least 1.6 billion people lack adequate housing (Habitat for Humanity, 2017). In the European context this figure continues to rise across all European Union member states except for Finland where homelessness has been on the decline since 1987 (FEANTSA, 2017; Y‐Foundation, 2017). Crisis, a charity based in the UK, estimated that in 2019 England acknowledged 57,890 households as homeless. In Wales, homelessness threatened 9,210 households and in Scotland, 34,100 individual applications were assessed for homelessness status (Fitzpatrick et al., 2016). Finally, Northern Ireland have an estimated 18,200 households experiencing homelessness according to a recent report (Fitzpatrick et al., 2020).

Without access to adequate housing, individuals experience multiple adverse effects including; exposure to disease, poverty, isolation, mental health issues, prejudice and discrimination, and are under constant and significant threat to their personal safety. Therefore, having access to safe, stable and adequate housing is internationally recognised as a basic human right (OHCHR, 2009) and is central to create the conditions whereby the population can live healthy, safe and happy lives.

2.2. The intervention

Homelessness is recognised as a multifaceted issue and many accommodation‐based approaches have evolved across the globe to incorporate additional support and services beyond delivery of housing, while other interventions deliver only temporary housing which is insufficient to meet people's basic needs. Through amalgamation of global ideas, the progression of evidence‐based policy and practice, and further establishment of welfare states, classification of accommodation‐based approaches is varied and represents the diversity in how the interventions were formed. The number of interventions which now exist, coupled with inconsistent descriptions of interventions and their elements (e.g., different models of housing, support services, expectations of engagement, etc.), has rendered current categorisations meaningless. Therefore, it was deemed necessary to group interventions based on their components, rather than their name. Later in this review, we describe how the review team created a novel and meaningful typology to categorise included interventions, however, initially we will briefly describe some of the familiar interventions that establish this evidence base.

2.2.1. Housing First

Housing First interventions offer housing to people experiencing homelessness with minimal obligation or preconditions being placed upon the participant. The Housing First programme, as conceived by Tsemberis (Tsemberis & Eisenberg, 2000), had clear principles which other researchers have since deviated from. However, most Housing First programmes share some common themes: (i) the participant is provided access to permanent housing immediately, without conditions, (ii) decisions around the location of the home and the services received are made by the user, (iii) support and services to aid the individual recovery are offered alongside housing placement, (iv) social integration with local community and meaningful engagement with positive activities is encouraged. Housing First is based on the principle that housing should be made available in the first instance and preconditions such as sobriety and involvement in treatment programmes are unnecessary barriers placed upon people who are homeless. Through the removal of these common obstacles, it is believed that the individual has a better chance of achieving stabilisation in appropriate housing and feeling more willing or able to accept treatment. In the original Pathways model of Housing First, housing provision is offered through scattered sites, which is where user choice is emphasised and housing is distributed (scattered) among existing rental properties. A key variation in the model has been the use of congregate housing where a property is reserved solely for the use of individuals experiencing homelessness. There is significant debate about the potential differences in effectiveness of these two models (Mackie et al., 2017).

2.2.2. Rapid rehousing

The rapid rehousing approach seeks to provide accommodation to individuals experiencing homelessness as quickly as possible. Generally, the rapid rehousing approach will identify available accommodation, aid with application, rent and moving in and the provision of case management to support access to other services. Rapid rehousing might provide the service user with a short‐term subsidy to assist with rent, rent in advance, help with rent arrears or help with moving. Generally, rapid rehousing targets those persons experiencing homelessness who have lower support needs and are less likely to require substantial access to services. The amount of support provided through a rapid rehousing approach is usually time limited.

2.2.3. Hostels

Hostels provide accommodation to meet short‐term housing needs. Homeless hostels often impose strict rules on the people who stay there relating to abstinence, behaviour and curfews. The individuals who use hostels vary but may include individuals, including those with pets, families and couples who are homeless. There is no clear definition on what constitutes a hostel and the provision offered will vary across councils, counties, and countries. Sleeping arrangements are variable too, with some offering dormitory style sleeping alongside communal kitchen, living, and shower areas while others have bedsit flats. The type of support offered by a homeless hostel is often determined by the resources available and individuals they can house. There are examples of in‐house support services such as: residents having a support plan to move to more stable accommodation; practical help with form filling and obtaining necessary governmental documents to continue education or gain employment; or treatment for substance abuse or mental health issues. This support is sometimes provided by other outside organisations separate to the hostel.

2.2.4. Shelters

Homeless shelters are typically viewed as a basic form of temporary accommodation where a bed is provided in a shared space overnight which a requirement for the individual to vacate the space during the day. One of the key features of a homeless shelter is that it is transitory and not usually seen as a stable form of accommodation as the individual are often in overcrowded buildings, and often subjected to physical altercations, theft, substance abuse, and unhygienic sleeping conditions. Like hostels, homeless shelters often place additional requirements on potential users including night‐time curfews. Additional services that may or may not be provided by the homeless shelter are warm meals for dinner and breakfast or support from volunteers and staff who help individuals make connections to other services. However, similarly to hostels, some support may be offered by external organisations and not by the shelter itself. Shelters and hostels are often defined in different ways in the UK and the United States, where these models are often used. Even within these categories there is substantial variability on the services that are provided and the conditions in which the facilities operate. Due to some of the common elements between shelters and hostels, which have now been outlined, the interventions are often described interchangeably in the global context, even if that masks some of the heterogeneity in provision.

2.2.5. Supported housing

Supported housing is an umbrella term for various accommodation‐based approaches and therefore an extremely complex intervention type. When providers describe their approach as supported housing, the intervention will typically combine housing with additional supportive services as an integrated package. The housing offered can be permanent or temporary; nonabstinent contingent or abstinent‐contingent; staffed group homes, community based or in a private unit; and the subsidies towards rent also vary. Supportive services will be offered directly to the individual or through referrals to the relevant body. Supportive services might include those to help with mental health issues, substance misuse, those interventions which increase access to health services, support to continue education or find employment, help with accessing benefits, or those services which focus on social aspects of the individual's life such as positive interactions with society, or community engagement. Due to the inconsistencies in the approach which “supported housing” takes, and the wide range of housing and support offered through supported housing interventions, it is incredibly difficult to group supported housing as a homogenous set of interventions for which to compare effectiveness to other groups of accommodation‐based approaches.

2.2.6. Conclusion

In homelessness literature, there is difficulty both in defining homelessness and the interventions which seek to benefit individuals (FEANTSA, 2017). Suttor argues that while it may be advantageous to create interventions tailored to an individual's unique needs, there is a need to classify approaches (Suttor, 2016). Indeed, most commentators acknowledge the challenges of lack of clear definition of the many terminologies used to describe accommodation‐based interventions. One example of this is highlighted in a study which identified 307 unique terms across 400 articles on supported accommodation (Gustafsson et al., 2009). Additionally, the Housing First model initially seems like an approach where categorisation is straightforward, however, there exists significant inconsistencies regarding implementation. Various researchers observe that this may be due to the way the Housing First model has deviated from the original “Pathways to Housing” intervention (Tsemberis & Eisenberg, 2000) due in part to additional services and support (Johnson et al., 2012; Phillips et al., 2011).

2.3. A new typology

Due to the diverse nature of the literature on accommodation‐based approaches, the way in which the approaches are implemented in practice, and the disordered descriptions of the categories, it became apparent that the review team must create meaningful categorisations to allow functional and useful comparison between the various intervention types. The importance of these categorisations cannot be understated, as it provides a comparative international framework from which policy makers and funders can work to understand the effectiveness of different accommodation‐based interventions.

One such typology already exists and is based on an international evidence review of 533 interventions for rough sleepers (Mackie et al., 2017). This review was led by one of the current review authors and identified characteristics of various types of temporary accommodation, namely shelters and hostels. The review team adapted this typology to inform the development of categories for the accommodation‐based interventions. This process was undertaken alongside Lipton and colleagues' (Lipton et al., 2000) descriptive categorisation of low, moderate, or high intensity housing which is based on the degree of structure and level of independence offered to their 2937 study participants. A further category (housing only) was added to allow for interventions which focused on providing accommodation for an extended period without further support or services offered. It was deemed to be more than just meeting the basic needs of the individual, but not intense enough to meet the criteria of the moderate category, as individuals were not receiving any additional services or help.

To develop the typology further, we used an iterative decision model. First, the review team selected a random sample of five accommodation‐based interventions included in the Evidence and Gap Map (EGM) of homelessness interventions (White et al., 2020), upon which this review is based. Second, two review team members independently coded the characteristics, hypotheses and concepts related to each intervention and compared notes. This independent analysis of the sampled papers ensured both objectivity and consistency in this step of the process and allowed the reviewers to investigate substantial amounts of data without bias or a predetermined hypothesis. Third, emerging themes were collated, and reviewers communicated to better understand the patterns which appeared through the sampled studies. Finally, through this iterative process we conclude that the most suitable way to create meaningful categorisations would be based around the intensity (defined as the level of the support offered).

Furthermore, interventions varied on the conditions the user was required to abide by. These conditions include needing to be sober from alcohol and/or drugs, abstain from criminal activity or to gain employment after a certain amount of time. To accurately incorporate these conditions into the categories, it must be stated whether the intervention required such a behavioural condition (conditional) or whether there were no behavioural conditions imposed (unconditional). The typology is described below and presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Typology: summary of categories

| Type of accommodation | Support | Conditionality | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic/conditional | Interventions that meet the user's basic human needs only, for example, providing bed and other basic subsistence such as food. | There are no named additional services or support offered to the user. This type of intervention focuses more on the short‐term benefit to the user | Conditions such as sobriety or punctuality apply |

| Basic/unconditional | Interventions that meet the user's basic human needs only, for example, providing bed and other basic subsistence such as food. | There are no named additional services or support offered to the user. This type of intervention focuses more on the short‐term benefit to the user | Accommodation is not conditional on adherence to rules such as sobriety or punctuality |

| Housing only/conditional | Accommodation provided for an extended period | Without additional support or services | Behavioural expectations are imposed on users, for example, they must enter paid employment within six months |

| Housing only/unconditional | Accommodation provided for an extended period | Without additional support or services | The participant is not required or obligated to meet any behavioural expectation to retain their housing |

| Moderate support/conditional | Accommodation provided for an extended period | The level of support and type of service offered will remain general and aimed towards a group of homeless individuals, and not specific to individual personal needs | Expectations on behaviour in place for example signing a contract agreeing to abstain from drugs and or alcohol |

| Moderate support/unconditional | Accommodation provided for an extended period | The level of support and type of service offered will remain general and aimed towards a group of homeless individuals, and not specific to individual personal needs | Accommodation not conditional on engagement (though engagement may be encouraged) |

| High support/conditional | Accommodation provided for an extended period | Assertive, individualised services and interventions for users. They often focus specifically on the personal needs of the user | Expectations such as abstinence from alcohol and drugs in place |

| High support/unconditional | Accommodation provided for an extended period | Assertive, individualised services and interventions for users. They often focus specifically on the personal needs of the user | No behavioural expectation such as sobriety placed on the user |

| No intervention (control groups) | None provided | None provided except basic information about other services | Not applicable |

-

1.

Basic/conditional

Interventions that meet the user's basic human needs only. This would be the provision of a bed and other basic subsistence such as food. There are no named additional services or support offered to the user. This type of intervention focuses more on the short‐term benefit to the user. The accommodation or support offered will require further conditions from the user upon admission such as sobriety or punctuality. An example of this intervention type would be if users were given one night in a shelter with a meal on the condition that they arrive by 11 pm.

-

2.

Basic/unconditional

Interventions which offer only minimal sleeping facilities to the user without additional services or support. Unlike the type of intervention described above, there are no behavioural expectations placed on the individual. An example of this would be if users were provided access to a shelter without exception.

-

3.

Housing only/conditional

The users are provided a form of accommodation for an extended period, with conditions, but without additional support or services. An example of this is shown in Siegel et al. (2006): one of the interventions described provides participants with housing where they are assisted with rent. Tenants were responsible for their own meals and utility expenses. An example of the behavioural expectations imposed on users receiving this type of intervention may be that they must enter paid employment within six months.

-

4.

Housing only/unconditional

Provision of housing for an extended period but without further support and services offered to the user. The participant is not required or obligated to meet any behavioural expectation to access the housing.

-

5.

Moderate support/conditional

Moderate levels of support and/or services are provided in addition to housing. The level of support and type of service offered will remain general and aimed towards a group of people experiencing homelessness, and not specific to individual personal needs. This housing, coupled with general support and services, will be offered on the condition that an individual meets a behavioural expectation. For example, Sosin et al. (1996) housing intervention a moderately intensive drug case management intervention was offered alongside the housing. To take part, participants had to sign a contract agreeing to abstain from drugs and or alcohol.

-

6.

Moderate support/unconditional

Interventions in this category are the same as the above category except there will be no behavioural expectation placed on the user for accessing the intervention. For example, Lim et al. (2017) focused on accessing cheaper housing and provided additional services to prevent youth from becoming homeless. The participants were encouraged to attend but it was not strictly enforced and there were no conditions placed upon the individuals to partake in the intervention.

-

7.

High support/conditional

These interventions provide housing and actively work to improve user's long‐term outcomes. The intervention provides assertive, individualised services and interventions for users. The intervention can involve improving housing stability, health, and employment, among other specific needs. The accommodation or support offered may place a behavioural expectation upon the person upon admission to the intervention. For example, participants in Schumacher et al. (2003) were provided housing alongside intensive treatment and other services. All participants were routinely tested for drugs and alcohol and were not allowed to continue with the intervention until they were deemed sober.

-

8.

High support/unconditional

Interventions in this category are the same as the above category except there is no behavioural expectation placed on the user. For example, Levitt et al. (2013) intervention included providing housing, meals and on‐site care services. On‐site case managers would consistently work with each individual participant on their substance use and life goals. The participant did not need to be sober to partake in the intervention.

-

9.

No intervention

Interventions in this category would be those that do not actively work to improve the lives of the users. The user is not offered a bed/food or any additional support. An example of this is demonstrated in Sosin et al. (1996) article. The control group used in this experiment received no additional aid. Those in the control group received some minimal information on where they could receive help in the form of abuse agencies or welfare offices but were not offered any additional help or services.

2.4. How the intervention might work

The distinctive component shared by all accommodation‐based interventions is that accommodation will be provided to individuals (even if only for the short‐term). Some interventions may also provide services alongside the accommodation and support they require to continue life independently without the risk of future homelessness.

2.5. Why it is important to do this review

The aim of this systematic review is to establish the effectiveness of accommodation‐based approaches though a robust and rigorous synthesis of the available literature. The typology described above provides a framework that potentially allows us to rank the effectiveness of interventions according to the different categories. However, this is only possible if there are sufficient eligible studies in each category.

2.5.1. Previous reviews

This systematic review is based on evidence already identified in two existing EGMs commissioned by the Centre for Homelessness Impact (CHI) and built by White et al. (2020). The EGMs present studies on the effectiveness and implementation of interventions aimed at people experiencing, or at risk of experiencing, homelessness.

The EGMs identified various systematic reviews which assess the effectiveness of interventions like Housing First (Beaudoin, 2016; Woodhall‐Melnik & Dunn, 2016) and supported housing (Burgoyne, 2013; Nelson et al., 2007; Richter & Hoffmann, 2017), and interventions which were conducted in hostel and shelter settings (Haskett et al., 2016; Hudson et al., 2016). However, an analysis comparing the relative effectiveness of different categories of accommodation‐based interventions for people who are homeless (for example, using network meta‐analysis) does not exist. Various systematic reviews which synthesise accommodation‐based interventions more generally, differ from the proposed review in several ways:

Differences in population

Bassuk, DeCandia, Tsertsvadze, and Richard (Bassuk et al., 2014) systematically reviewed and narratively reported the findings of six studies which looked at the effectiveness of housing interventions and housing combined with additional services. The interventions included Housing First, rapid rehousing, vouchers, subsidies, emergency shelter, transitional housing, and permanent supportive housing. However, authors limited the population to American families who were experiencing homelessness and so any final conclusions on the efficacy of accommodation‐based interventions on the wider population of individuals experiencing homelessness are impossible to reach.

Differences in outcomes of interest

Fitzpatrick‐Lewis and colleagues (Fitzpatrick‐Lewis et al., 2011) conducted a rapid systematic review on the effectiveness of interventions to improve the health and housing status of individuals experiencing homeless which located 84 relevant studies. Only those studies published between January 2004 and December 2009 were included in this review and so the current review is more up to date and broader in scope. Additionally, the primary purpose of the review was to identify literature which improved health outcomes for those experiencing homelessness and so other important outcomes were not included.

Mathew and colleagues (Mathew et al., 2018) conducted a Campbell Collaboration systematic review which looks at how various interventions impact the physical and mental health of people who are homeless alongside other social outcomes. One objective listed in the title registration form is similar to the scope of the current review. Authors assessed “What are the effects of housing models (i.e., Housing First) on the health outcomes of homeless and vulnerably housed adults compared to usual or no housing?” However, the current review has a wider scope by including additional outcomes across a wider population.

A second Campbell Collaboration systematic review (Munthe‐Kaas et al., 2018) assessed the effectiveness of both housing and case management programmes for people experiencing, or at risk of experiencing homelessness. The main outcomes of interest to the authors were reduction in homelessness and housing stability. Authors searched the literature until January 2016 and uncovered 43 RCTs meeting the predetermined inclusion criteria. Authors did not include qualitative research or extract data related to the cost of the interventions, which are variables of interest to this proposed review.

Differences in analytic methods

A recent review by the What Works Centre for Wellbeing (Chambers et al., 2018) included 90 studies which included clusters of Housing First (n = 47), supported housing (n = 12), recovery housing (n = 10), housing interventions for ex‐prisoners (n = 7), housing interventions for vulnerable youth (n = 3) and “other” complex interventions targeted at those with poor mental health (n = 11). Authors presented a comprehensive search strategy of both commercial and grey literature, however, due to resource constraints were unable to conduct independent screening of the potential studies and therefore risk selection bias in the review. Additionally, only studies published after 2005 were included in this review and so the current review is much broader in scope. Finally, the authors' objective was to create a conceptual pathway and evidence map between housing and wellbeing and so the results were not meta‐analysed but described narratively instead.

Inclusion of qualitative studies

Finally, this review also includes qualitative data, to complement the quantitative results on effectiveness, by highlighting important implementation and process issues related to the delivery and uptake of accommodation‐based services. The qualitative studies included in this element of the report are drawn from CHI's implementation and process EGM and described in more detail below.

3. OBJECTIVES

-

1.

What is the effect of accommodation‐based interventions on outcomes including housing stability, health, employment, crime, and wellbeing, for individuals experiencing or at risk of experiencing homelessness?

-

2.

Which type of intervention is most/least effective compared to other interventions and compared to business as usual (passive control)?

-

3.Who do accommodation‐based interventions work best for?

-

a.Young people or older adults?

-

b.Individuals with high or low complex needs?

-

c.Families or single individuals?

-

a.

-

4.

Does the geographical spread of housing (scattered site or conglomerate/congregate) affect the outcomes experienced by individuals experiencing or at risk of experiencing homelessness?

-

5.

What implementation and process factors impact intervention delivery?

4. METHODS

4.1. Criteria for considering studies for this review

4.1.1. Types of studies

The systematic review and network meta‐analysis was prospectively registered with the Campbell Collaboration to improve quality of the review, promote transparency and replicability, and avoid duplication of effort. The protocol was published in September 2020 (Keenan et al., 2020), and can be accessed through the Campbell Collaboration library.

We included all study designs where a comparison group was used. This included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), quasi‐experimental designs, matched comparisons and other study designs that attempt to isolate the impact of the intervention on homelessness using appropriate statistical modelling techniques.

As RCTs are accepted as more rigorous than nonrandomised studies, the potential impact of a nonrandomised study design on effect sizes was explored as part of the analysis of heterogeneity.

Studies were eligible for inclusion in the review if they included a comparison condition, for example:

No treatment.

Treatment as usual where people receive their normal level of support or intervention.

Waiting list where individuals or groups are randomly assigned to receive the intervention at a later date.

Attention control, where participants receive some contact from researchers but both participants and researchers are aware that this is not an active intervention.

Alternative treatment, an active accommodation‐based approach used to compare treatments.

Placebo where participants perceive that they are receiving an active intervention, but the researchers regard the treatment as inactive.

Studies with no control or comparison group, unmatched controls or national comparisons with no attempt to control for relevant covariates were not included. Case studies, opinion pieces or editorials were also not included.

4.1.2. Types of participants

This systematic review focused on all individuals currently experiencing, or at risk of experiencing homelessness irrespective of age or gender, in high‐income countries. Homelessness is defined as those individuals who are sleeping “rough” (sometimes defined as street homeless), those in temporary accommodation (such as shelters and hostels), those in insecure accommodation (such as those facing eviction or in abusive or unsafe environments), and those in inadequate accommodation (environments which are unhygienic and/or overcrowded).

4.1.3. Types of interventions

Interventions included those based on the typology outlined above and were classified according to the nature and characteristics of the intervention rather than the descriptor provided by the study author(s).

The control or comparison condition can include no services/intervention, services as usual, waitlist control, attention control, placebo or an alternative accommodation‐based intervention (see Section 4.1.1 for more detail).

4.1.4. Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

This review primarily addresses how interventions can reduce homelessness and increase housing stability for those individuals experiencing, or at risk of experiencing, homelessness.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes include:

Access to mainstream healthcare

Crime and justice

Employment and income

Capabilities and wellbeing

Cost of intervention.

These outcomes reflect the domains used in the EGM (White et al., 2020), with the addition of cost.

Types of settings

Settings where these accommodation‐based interventions take place were varied and included hostels, shelters, and community housing.

4.2. Search methods for identification of studies

This systematic review is based only on the evidence already identified in two existing EGMs commissioned by the Centre for Homelessness Impact (CHI) and built by White et al. (2020). The EGMs include studies on the effectiveness and implementation of interventions aimed at people experiencing, or at risk of experiencing, homelessness in high income countries.

4.2.1. Electronic searches

The maps used a comprehensive three stage search and mapping process. Stage one was to map the included studies in an existing Campbell review on homelessness (Munthe‐Kaas et al., 2018), stage two was a comprehensive search of 17 academic databases, three EGM databases, and eight systematic review databases for primary studies and systematic reviews. Finally stage three included web searches for grey literature, scanning reference lists of included studies and consultation with experts to identify additional literature. Sample search terms can be found in the protocol (White et al., 2020).

4.2.2. Searching other resources

We did not undertake any additional searching. However, while contacting authors for additional information, authors of the Chez Soi trial (Goering et al., 2011) provided additional reports of identified studies. The inclusion of these reports provided extra data necessary for conducting analysis and ROB assessments

4.3. Data collection and analysis

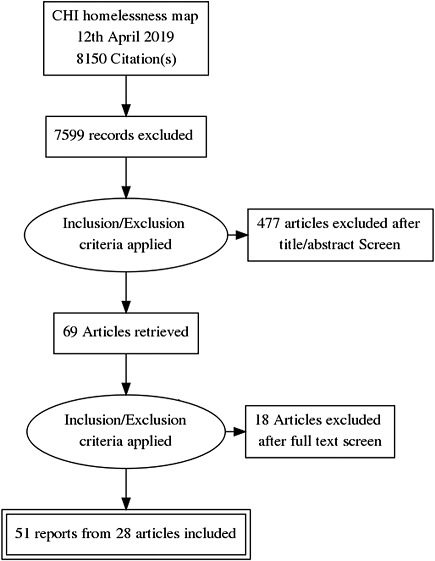

To identify studies from the map that were eligible for inclusion in this review, two reviewers independently screened the title and abstract of all documents in the effectiveness map using EPPI Reviewer 4 software. The full text of studies that met or appeared to meet the inclusion criteria were then screened independently by two reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved in discussion with a third reviewer until a consensus was reached. The same process was applied to screening documents included in the process evaluation maps to identify studies eligible for inclusion in the qualitative synthesis. The flow of studies through the screening process are documented in a PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram

4.3.1. Description of methods used in primary research

Interventions included RCTs and quasi‐experimental studies measuring the effectiveness of accommodation‐based approaches against either a control group or through head‐to‐head comparisons with an alternative (accommodation‐based) treatment.

4.3.2. Criteria for determination of independent findings

Often, authors reported data on the same participants across more than one outcome, this leads to multiple dependent effect sizes within each single study. The meta‐analysis therefore used robust variance estimation to adjust for effect size dependency (Hedges et al., 2010). The correction for small samples (Tipton & Pustejovsky, 2015) was implemented when necessary. Finally, in cases where study authors separate participants into subgroups relating to age, comorbid diagnosis, or gender and it is inappropriate to pool their data, these participants remained independent of each other and were treated as separate studies which each provide unique information.

4.3.3. Selection of studies

To identify studies from the map that were eligible for inclusion in this review, two reviewers independently screened the title and abstract of all documents in the effectiveness map using EPPI Reviewer 4 software. The full text of studies that met or appeared to meet the inclusion criteria were then screened independently by two reviewers. Any disagreements were resolved in discussion with a third reviewer until a consensus was reached. The same process was applied to screening documents included in the process evaluation maps to identify studies eligible for inclusion in the qualitative synthesis. The flow of studies through the screening process are documented in a PRISMA flow chart Figure 1.

4.3.4. Data extraction and management

Once eligible studies were identified, we undertook dual data extraction, where two authors completed data extraction and ROB assessments independently for each study. Coding was carried out by trained researchers. Any discrepancies in screening or coding were discussed with senior authors until a consensus was reached.

Details of study coding categories

A data extraction tool was designed by the authors and piloted by trained research assistants using EPPI Reviewer (Appendix A). At a minimum, we extracted the following data: publication details, intervention details including setting, implementation, delivery personnel, descriptions of the outcomes of interest including instruments used to measure, design and type of trial, sample size of treatment and control groups, data required to calculate Hedge's g effect sizes, quality assessment. We extracted more detailed information on the interventions such as: duration and intensity of the programme, timing of delivery, key programme components (as described by study authors), theory of change.

Alongside extracting data on programme components, descriptive information for each of the studies was extracted and coded to allow for sensitivity and subgroup analysis. This included information regarding:

Setting in which the intervention is delivered

Study characteristics in relation to design, sample sizes, measures and attrition rates, who funded the study and potential conflicts of interest.

Demographic variables relating to the participants including age, complexity of needs, dependent children, and other relevant population characteristics.

Quantitative data were extracted at immediate post‐test to allow for calculation of effect sizes (such as mean change scores and standard error or pre‐ and post‐ means and SDs or binary 2 × 2 tables). Data were then extracted for the intervention and control groups on the relevant outcomes measured, in order to assess the intervention effects.

4.3.5. Assessment of ROB in included studies

Assessment of methodological quality and potential for bias was conducted using the second version of the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool for RCTs (Higgins et al., 2019). The methodological quality of nonrandomised studies was coded using the ROBINS‐ I tool (Sterne et al., 2016).

4.3.6. Measures of treatment effect

Statistical procedures and conventions

Most outcomes reported were based on continuous variables and so the main effect size metric that was used for the purposes of the meta‐analyses was the standardised mean difference, with its 95% confidence interval. Within this, Hedges' g was used to correct for any small sample bias. Where other effect sizes were reported, such as Cohen's d or risk ratios (for dichotomous outcomes) these were converted to Hedges' g for the purposes of the meta‐analysis using formulae provided in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins et al., 2019).

Most outcomes were calculated using the David‐Wilson Calculator (Wilson, 2019), utilising formulae to find the effect size of several continuous data, including means and SDs. Hozo's Formula (Hozo et al., 2005) was also used to help calculate effect sizes when Interquartile range and Median data were provided.

4.3.7. Unit of analysis issues

The analyses presented utilised a random effects model (REM), estimating the variance component with restricted (or residual, or reduced) maximum likelihood (REML). The REM was chosen as the statistical model as it accepts two main differences among primary studies, the first is within study variance, and the second is between study variance. This between study variance, or heterogeneity, can reflect important differences in populations, settings, or progression of time (Borenstein et al., 2009). To allow for estimation of the variance components, the Satterthwaite approximation was used to account for two different sample variances where only estimates of the variance are known. The analysis is useful to calculate an approximation to the effective degrees of freedom (Satterthwaite, 1946).

4.3.8. Dealing with missing data

If study reports did not contain sufficient data to allow calculation of effect size estimates, authors were contacted to obtain necessary summary data, such as means and SDs or standard errors. If no information were forthcoming, the study could not be included in meta‐analysis and was instead included in a narrative synthesis.

4.3.9. Assessment of heterogeneity

The meta‐analysis included the overall mean and prediction interval for all primary outcomes in the analysis to examine the distribution of effect sizes. The analysis was conducted in two phases: (a) the use of meta‐regression to examine heterogeneity across studies, and (b) a network meta‐analysis (NMA) to address the relative effects of the included interventions.

4.3.10. Assessment of reporting biases

A problem which threatens the conclusions made by every meta‐analysis is the potential for publication bias. This threat arises from the decreased likelihood of studies which have negative or insignificant results to be published, and therefore the studies available to the researcher will not be representative of all the studies conducted on the topic of interest. Using the metafor package in R (Viechtbauer, 2010), the samples were visually investigated for publication bias using a funnel plot.

4.3.11. Data synthesis

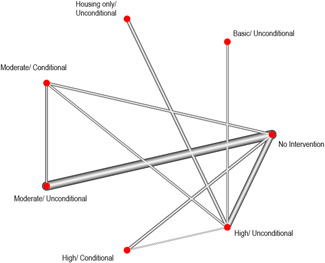

When conducting meta‐analysis on the effectiveness of accommodation‐based interventions, we were attentive to whether different types of accommodation‐based intervention (as defined by our typology) are more or less effective for individuals experiencing homelessness. Few of the included trials compared the effects of two interventions directly (n = 11) and so direct comparisons between some accommodation‐based interventions do not exist, however the majority of interventions were tested against equivalent control groups. Thus, through NMA, it is possible to calculate the indirect effects of comparative accommodation‐based interventions and produce this as a “network” of comparisons. These analyses were completed via a frequentist model using R package, netmeta, and are reported below.

4.3.12. Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted moderator analyses that test whether specific characteristics of the studies or the interventions can explain some of the heterogeneity in results. It is important to understand that moderator analyses are exploratory and should never be implemented to test hypotheses. Even if the meta‐analysis contains only studies with specific methodologies (RCTs and quasi‐experiments), the studies involved in these moderator analyses have not been randomised, they are observational in nature and at a higher ROB. Additionally, these type of analyses generally have lower power due to missing data in the primary research, there is an increased risk of presenting incorrect results which appear simply through chance (false positive conclusion), and potential for various biases (Borenstein et al., 2009; Higgins et al., 2019). Although these analyses are a common inclusion to many meta‐analyses as they are useful for developing ideas and exploring heterogeneity, moderator analysis have low statistical power and should always be interpreted with caution (Borenstein et al., 2009).

We used the R programmes metafor (Viechtbauer, 2010) for analyses, netmeta for NMA (Rücker et al., 2015), and clubSandwich (Pustejovsky, 2017) to adjust the standard errors of the model for dependencies. The intended moderators for subgroup analyses included: participant age, complexity of need, whether the intervention was focused on families or individuals, geographical spread of housing (scattered site or conglomerate), study design, and ROB.

Treatment of qualitative research

The qualitative research that was included in this review is based upon existing evidence collated through the second implementation and process EGM constructed by White et al. (2018). The EGM includes 292 qualitative process evaluations on the implementation issues associated with interventions designed to target homelessness. These are not the same studies that are included in the effectiveness EGM or included in the meta‐analyses reported below. These qualitative reports were downloaded from EPPI reviewer on 10th May 2019 and screened for relevance to the current review.

The EGM categorises included studies into broad categories of barriers and facilitators to the implementation of interventions. These categories were developed by the original authors of the EGM using an iterative process and were initially based on the implementation science framework (Aarons et al., 2011). The categories were independently piloted against a small number of process evaluations and agreement was reached by researchers in the Campbell Collaboration, Campbell UK and Ireland, and Heriot‐Watt University. The five broad categories are contextual factors, policy makers/funders, programme managers/implementing agency, staff/case workers, and recipients. The review team recognise that in the majority of accommodation‐based interventions, more than one of the agreed categories could act as a factor that impacts positively or negatively on the effectiveness of the intervention, or both in some cases. This potential overlap reflects the complexity of the implementation of the interventions and the multifaceted evaluation tools needed within this review. For this reason, the review team decided to focus on factors that influence intervention effectiveness in order to formulate a coherent Synthesis Framework.

We included process evaluations and other relevant qualitative studies that provide data that enables a deeper understanding of why the accommodation‐based programmes included in the quantitative synthesis do (or do not) work as intended, for whom and under what circumstances. We conducted a “Best Fit” Framework synthesis in order to have a highly structured approach to organising and analysing data, which can prove difficult to do with qualitative data. This method is largely informed by background material and team discussions to extract and synthesise findings. This is particularly useful given the mixed methods approach, as the quantitative and qualitative data can work in tandem to give the clearest results possible.

4.3.13. Sensitivity analysis

Every meta‐analysis includes decisions made by the researchers which may affect the findings and inferences which can be drawn from the conclusions. In this meta‐analysis, two sensitivity analyses were employed to explore the robustness of the overall results by removing certain study characteristics which may cause influence on the outcome of the analysis.These included study design and ROB.

4.3.14. Summary of findings and assessment of the certainty of the evidence

The quality of these mixed methods studies was assessed using a tool developed by White and Keenan (Appendix A, Part 7). The tool is similar to the fidelity assessment used by Stergiopoulos et al. (2016) and aims to provide an accurate account of the eligible qualitative studies. The tool considers methodology, recruitment and sampling, bias, ethics, analysis and findings. We also describe the characteristics of included qualitative studies in terms of what qualitative methods have been used to capture this rich data, the number of interviews/focus groups/observations that have taken place, who participated and the nature of qualitative data collection.

5. RESULTS

5.1. Description of studies

We identified 223 unique studies across 551 articles from the effectiveness map on 12th April 2019. Of these 551 articles, we deemed 69 to meet eligible inclusion criteria following title and abstract screening. Full text screening led to the exclusion of a further 18. More details can be found in the PRISMA Flow Diagram (Figure 1). In total, 28 eligible studies reported in 51 accommodation intervention papers were identified and included in this review:

Study ID: Appel 2012

-

Housing first for severely mentally Ill homeless methadone patients (Appel et al., 2012).

Study ID: Brown 2016

-

Housing first as an effective model for community stabilisation among vulnerable individuals with chronic and nonchronic homelessness histories (Brown et al., 2016).

Study ID: Buchanan 2006

-

The effects of respite care for homeless patients: A cohort study (Buchanan et al., 2006).

Study ID: Buchanan 2009

-

The health impact of supportive housing for HIV‐positive homeless patients: A RCT (Buchanan et al., 2009).

Study ID: Cheng 2007

-

Impact of supported housing on clinical outcomes analysis of a randomised trial using multiple imputation technique (Cheng et al., 2007).

Study ID: Gilmer 2010

-

Effect of full‐service partnerships on homelessness, use and costs of mental health services, and quality of life among adults with serious mental illness (Gilmer et al., 2010).

Study ID: Goering 2011 (Chez Soi)

The at Home/Chez Soi trial protocol: A pragmatic, multi‐site, RCT of housing first in five Canadian cities (Goering et al., 2011).

Effect of housing first on suicidal behaviour: A randomised controlled trial of homeless adults with mental disorders (Aquin et al., 2017).

Housing First for people with severe mental illness who are homeless: A review of the research and findings from the At Home‐Chez soi demonstration project (Aubry et al., 2015).

At Home/Chez Soi interim report (Goering, 2012).

The impact of a Housing First RCT on substance use problems among homeless individuals with mental illness (Kirst et al., 2015).

“Housing First” for homeless youth with mental illness (Kozloff et al., 2016).

At Home/Chez Soi randomised trial: How did a Housing First intervention improve health and social outcomes among homeless adults with mental illness in Toronto? Two‐year outcomes from a randomised trial (O'Campo et al., 2016).

Housing first improves subjective quality of life among homeless adults with mental illness: 12‐month findings from a RCT in Vancouver, British Columbia (Patterson et al., 2013).

Effects of housing first on employment and income of homeless individuals: Results of a Randomised Trial (Poremski et al., 2016).

Housing First improves adherence to antipsychotic medication among formerly homeless adults with schizophrenia: Results of a RCT (Rezansoff et al., 2017).

Emergency department utilisation among formerly homeless adults with mental disorders after one year of Housing First interventions: a RCT (Russolillo et al., 2014).

Effect of scattered‐site housing using rent supplements and intensive case management on housing stability among homeless adults with mental illness (Stergiopoulos et al., 2015).

Study ID: Goldfinger 1999

-

Housing placement and subsequent days homeless among formerly homeless adults with mental illness (Goldfinger et al., 1999).

Study ID: Gulcur 2003 (Pathways to Housing)

Housing, hospitalisation, and cost outcomes for homeless individuals with psychiatric disabilities participating in continuum of care and Housing First programmes (Gulcur et al., 2003).

Decreasing psychiatric symptoms by increasing choice in services for adults with histories of homelessness (Greenwood et al., 2005).

Housing first, consumer choice, and harm reduction for homeless individuals with a dual diagnosis (Tsemberis et al., 2004).

Consumer preference programmes for individuals who are homeless and have psychiatric disabilities: A drop‐in centre and a supported housing programme (Tsemberis et al., 2003).

Study ID: Howard 2011

-

Effectiveness and cost‐effectiveness of admissions to women's crisis houses compared with traditional psychiatric wards: Pilot patient‐preference RCT (Howard et al., 2011).

Study ID: Hwang 2011

-

Health status, quality of life, residential stability, substance use, and health care utilisation among adults applying to a supportive housing programme (Hwang et al., 2011).

Study ID: Kertesz 2007

Long‐term housing and work outcomes among treated cocaine‐dependent homeless persons (Kertesz et al., 2007).

To house or not to house: The effects of providing housing to homeless substance abusers in treatment (Milby et al., 2005).

Costs and effectiveness of treating homeless persons with cocaine addiction with alternative contingency management strategies (Mennemeyer et al., 2017).

Study ID: Larimer 2009

-

Health care and public service use and costs before and after provision of housing for chronically homeless persons with severe alcohol problems (Larimer et al., 2009).

Study ID: Levitt 2013

-

Randomised trial of intensive housing placement and community transition services for episodic and recidivist homeless families (Levitt et al., 2013).

Study ID: Lim 2017

-

Impact of a supportive housing program on housing stability and sexually transmitted infections among young adults in New York City who were aging out of foster care (Lim et al., 2017).

Study ID: Li m 2018

-

Impact of a New York City supportive housing programme on Medicaid expenditure patterns among people with serious mental illness and chronic homelessness (Lim et al., 2018).

Study ID: Lipton 2000

-

Tenure in supportive housing for homeless persons with severe mental illness (Lipton et al., 2000).

Study ID: McHugo 2004

-

A randomized controlled trial of integrated versus parallel housing services for homeless adults with severe mental illness (McHugo et al., 2004).

Study ID: Milby 1996

Sufficient conditions for effective treatment of substance abusing homeless persons (Milby et al., 1996).

Costs and effectiveness of treating homeless persons with cocaine addiction with alternative contingency management strategies (Mennemeyer et al., 2017).

Study ID: Milby 2000

Initiating abstinence in cocaine abusing dually diagnosed homeless persons (Milby et al., 2000).

Costs and effectiveness of treating homeless persons with cocaine addiction with alternative contingency management strategies (Mennemeyer et al., 2017).

Study ID: Milby 2008

Toward cost‐effective initial care for substance‐abusing homeless (Milby et al., 2008).

Effects of sustained abstinence among treated substance‐abusing homeless persons on housing and employment (Milby et al., 2010).

Costs and effectiveness of treating homeless persons with cocaine addiction with alternative contingency management strategies (Mennemeyer et al., 2017).

Study ID: O'Connell 2012

-

Differential impact of supported housing on selected subgroups of homeless veterans with substance abuse histories (O'Connell et al., 2012).

Study ID: Sadowski 2009

Effect of a housing and case management program on emergency department visits and hospitalizations among chronically Ill homeless adults a randomized trial (Sadowski et al., 2009).

Comparative cost analysis of housing and case management program for chronically Ill homeless adults compared to usual care (Basu et al., 2012).

Study ID: Shern 1997 (Choices)

Housing outcomes for homeless adults with mental illness: Results from the second‐round McKinney Program (Shern et al., 1997).

Serving street‐dwelling individuals with psychiatric disabilities: Outcomes of a psychiatric rehabilitation clinical trial (Shern et al., 2000).

Consumer preference programmes for individuals who are homeless and have psychiatric disabilities: a drop‐in centre and a supported housing programme (Tsemberis et al., 2003).

Study ID: Siegel 2006

-

Tenant outcomes in supported housing and community residences in New York City (Siegel et al., 2006).

Study ID: Sos in 1996

-

Paths and impacts in the progressive independence model: A homelessness and substance abuse intervention in Chicago (Sosin et al., 1996).

Study ID: Srebnik 2013 (Begin at Home)

-

A pilot study of the impact of Housing First‐supported housing for intensive users of medical hospitalisation and sobering services (Srebnik et al., 2013)

Study ID: Stefancic 2007

Housing First for long‐term shelter dwellers with psychiatric disabilities in a suburban county: a four‐year study of housing access and retention (Stefancic & Tsemberis, 2007).

5.1.1. Results of the search

The flow of studies through the screening process are documented in a PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1).

5.1.2. Included studies

There was a total of 13,128 people included in the review, across 28 studies. Most of the included studies were carried out in the United States of America (25/28), with other locations including Canada (Goering et al., 2011; Hwang et al., 2011) and the UK (Howard et al., 2011). The location of the studies was largely urbanised, with 26/28 of the studies conducted in cities, with one study not specifying its location (O'Connell et al., 2012), and the other focusing on suburban homelessness (Stefancic & Tsemberis, 2007).

Twenty‐seven of the 28 studies were published in journal articles. Sixteen studies were RCTs (57%) and 12 were nonrandomised (quasi‐experimental) designs (43%).

The mean age of all participants was 36.7 years. Most participants were men, on average samples were 71.3% men (ranging from 47.5% to 100% men). In all but two studies the participants had complex needs with poor mental health and substance use issues the main needs identified, and in some studies, the population that participants were drawn from was specifically targeted because of chronic homelessness and multiple complex needs.

The two main sources of funding were research council funding and grants or loans from trusts and charities. Three studies did not specify their source of funding (Brown et al., 2016; Siegel et al., 2006; Stefancic & Tsemberis, 2007). More details on the characteristics of the included studies can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Included studies

| Study title | Name of intervention(s) | Complexity of needs | Sample size | Age | Sex | Design | Typology |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appel (2012) | Keeping “Home project”: Housing First approach | Poor Mental Health and Substance abuse issues | 61 | Mean: Intervention, 45.9 (range 26–63); Control, 39.7 (no range mentioned) |

Male: Intervention, 26 (80.8%); Control, 19 (63.3%). Female: Intervention, 5 (19.2%); Control, 11 (36.7%) |

Non‐RCT | High unconditional |

| Brown (2016) | Housing First | Poor Mental Health (70.9%) and Substance abuse issues (75.8%) | 182 | Mean, 42.79; SD, 11.14 | Male: 73.6%; Female: 26.4% | Non‐RCT | High unconditional |

| Buchanan (2006) | Respite Care | Poor Physical Health | 225 | Mean (SD), Intervention, 43 (9); Control, 44 (10) |

Male: Intervention, 78% (125); Control, 81% (52). Female: Intervention, 22% (36); Control, 19% (12) |

Non‐RCT | Moderate conditional |

| Buchanan (2009) | The Chicago Housing for Health Partnership (CHHP) | Poor Physical Health and substance abuse issues | 94 | Intervention, mean 45 (SD 6.9); Control, mean 43 (SD 7.7) |

Male: Intervention, 39 (72%); Control; 43 (84%). Female: Intervention, 15 (28%); Control, 8 (16%) |

RCT | High—conditional and unconditional, depending on participant |

| Cheng (2007) | HUD‐VASH | Poor Physical Health and substance abuse issues | 460 | Not specified | Not specified | RCT | Moderate unconditional |

| Gilmer (2010) | Full‐Service Partnerships (FSP) | Poor Mental Health and Incarceration | 363 | Mean (SD), Intervention, 44 (9); Control, 43 (11) |

Male: Intervention, 131/209 (63%); Control, 97/154 (63%). Female: Intervention, 78/209 (37%); Control, 57/154 (37%) |

Non‐RCT | High conditional |

| Goering (2011) | Chez Soi—Housing First | Poor Mental Health | 2131 | 40.89 (SD, 11.23) | Male: 1508 (67.9%); Female: 603 (31.2); Other: 20 (.9%) | RCT | High unconditional |

| Goldfinger (1999) | Group homes, or Independent Apartments. | Poor Mental Health and Substance abuse issues | 110 | Mean, 38 |

(Intervention only) Male: 85 (72%); Female 33 (28%) |

RCT | High unconditional |

| Gulcur (2003) | HOUSING FIRST Continuum of Care | Poor Mental Health and Incarceration and Substance abuse issues | 199 | Not specified |

Male: 173; Female: 52 |

RCT | High unconditional |

| Howard (2011) | Crisis House or Patient preference of Crisis House | Poor Mental Health | 44 | Mean (SD), 37.5(11.1) | Female: 102 participants (100%) | RCT | Moderate conditional |

| Hwang (2011) | Supportive housing | None specified | 112 |

22 people aged 17–0, 90 people aged 31 and over |

81 male 72% 30 (27%) women one (1%) transgendered individual | Non‐RCT | High conditional |

| Kertesz (2007) | ACH Vs NACH Vs Control | Poor psychical Health, poor mental health, incarceration and substance abuse issues. | 99 |

Mean (SD): ACH: 38.25 (2.61); N‐ACH: 41.25 (3.19); Control: 38.5 (2.61) |

Male: ACH, 74.6% (47); N‐ACH, 76.8% (50); Control/No Housing, 76.8% (50). Female: ACH, 25.4% (16); N‐ACH, 24.2% (16); Control/No Housing, 24.2% (16) |

RCT |

Intervention 1, high conditional. Intervention 2, high unconditional |

| Larimer (2009) | Housing First | Poor Physical health and substance abuse issues | 134 | Mean (SD), Overall, 48 (10); Intervention: 48 (9); Control: 48 (11) |

Male, 94% (126); Female, 6% (8) |

Non‐RCT | High unconditional |

| Levitt (2013) | Home to stay | None Specified |

Mean (SD), Intervention: 33.5 (8.7); Control: 33.9 (7.2) |

Not specified | RCT | Moderate conditional | |

| Lim (2017) | NYNY IIII | Substance Abuse Issues, care leaver and high risk of harm and/or exploitation | 895 | Mean overall: 18.6 |

Male, 510; Female, 385 |

Non‐RCT | High unconditional |

| Lim (2018) | New York Supportive Housing Program | Poor Mental Health and Substance abuse issues | 330 families/2827 individuals | Number of people in each group: 18–34 years, 16%; 35–44 years, 26%; 45–54 years, 38%; ≥55 years, 20% |

Male, 70% of 2827; Female, 30% of 2827 |

Non‐RCT | High unconditional |

| Lipton (2000) | Intervention 1: High Intensity Housing Intervention 2: Moderate Intensity Housing Intervention 3: Low Intensity Housing | Poor Mental Health and Substance abuse issues | 2937 | Mean (SD), 40.3(10.3) |

Male 67% n = 1980; Female 33%, n = 957 |

Non‐RCT |

Intervention 1, high conditional. Intervention 2, moderate conditional |

| McHugo (2004) | Integrated housing services programme | Poor Mental Health | 113 | Ranged, 21–60 years |

Male: Intervention, 29 (47.5%); Control, 29 (48.3%). Female: Intervention, 32; Control, 31 |

RCT | High unconditional |

| Milby (1996) | Enhanced Care | Substance abuse issues | 176 | Age, mean (SD) Usual Care, 35.7 (6.2); Enhanced Care, 36.0 (6.6) |

Male Intervention 54 (87.1%) Usual Care 50 (72.5%) Female Usual Care 8 (12.9) Enhanced Care 19 (27.5) |

RCT | High conditional |

| Milby (2000) | Day treatment+ | Poor Mental Health and Substance Abuse Issues | 110 | Mean (SD), DT, 39.1 (7.5); DT+, 37.3 (7.2); Al, 38.1 (7.4) |

Male: DT, 45 (83%); DT+, 39 (70%); All, 84 (76%). Female: DT, 9 (17); DT+, 17 (30); All, 26 (24%) |

RCT | High conditional |

| Milby (2008) | CM and CM+ (Contingency Management plus behavioural day treatment) | Substance abuse issues | 206 | CM, 39.5 (7.2); CM+, 40.6 (7.1) |

Male: CM, 77 (74.8%); CM+, 73 (70.9%). Female: CM, 26 (25.2); CM+, 30 (29.1 |

RCT | High conditional |

| O'Connell (2012) | Housing and Urban Development–Veterans Affairs Supported Housing (HUD‐VASH) Intensive Care Management (ICM) | Poor physical Health, Poor mental health, substance abuse issues | 207 | Age (median + SD), TAU, 42.3 + −7.5; ICM, 44.0 + −6.3; HUD‐VASH, 41.8 + −7.1 | 100% Male | RCT | Moderate unconditional |

| Sadowski (2009) | Housing and Case management (HOUSING FIRST) | Poor mental health and substance abuse issues | 357 | 25 and over |

Male, 310/405 75%; Female, 95/405 25% |

RCT | High unconditional |

| Shern (1997) | New York Street Study—Specialised Housing | Poor Mental Health | 168 | 37.5 (9.01) years |

Male, 72%; Male, (644). Female, 28%; Female, (250) |

RCT | Moderate conditional |

| Siegel (2006) | Supported Housing (SH) vs community residences (CR) | Poor Physical Health, poor mental health and Substance abuse issues | 47 |

Mean (SD): Stratum 1 (N‐10): SH, 34.7 (7.9); CR, 36(7.9) (n‐37). Stratum 2: SH, 41.6 (11.2) (N‐18); CR, 41.3 (10) (N‐28). Stratum 3: SH, 47.4 (10.1) (N‐39); CR, 41.6 (8.5) (N‐7) |

Male: 91/139 across three strata of interventions. Female: 48/139 Across three strata of interventions |

Non‐RCT |

Intervention 1, high unconditional. Intervention 2, high conditional |

| Sosin (1996) | Housing and case management Case management alone | Substance abuse issues | 419 | Mean, 35; Housing, 35.5; case management, 35.2; control, 34.6 |

Male: 74.5% 312. Female: 25.5% 107 |

Non‐RCT | Moderate conditional |

| Srebnik (2013) | Housing First | Poor Physical Health, poor mental health and substance abuse issues | 60 | Intervention mean, 51.3; SD, 9.2. Control mean, 50.0; SD, 6.9 |

Male: 52 (87%); Intervention, 21 (72%); Comparison, 31 (100%); Female: 8 (13%); Intervention, 8 (28%); Comparison, 0 (0%) |

Non‐RCT | High unconditional |

| Stefancic and Tsemberis (2007) | Pathways Consortium (Housing First) | Poor mental health and substance abuse issues | 392 | over 18 to be eligible, otherwise not specified |

Male:74.23% 193; Pathways, 71, 67.6%; Consortium, 83, 79.8%; Control, 39, 76.5%. Female: 25.77%. 67; Pathways, 34, 32.4%; Consortium, 21, 20.2%; Control, 12, 23.5% |

RCT | High unconditional |

Descriptive account of reported accommodation interventions

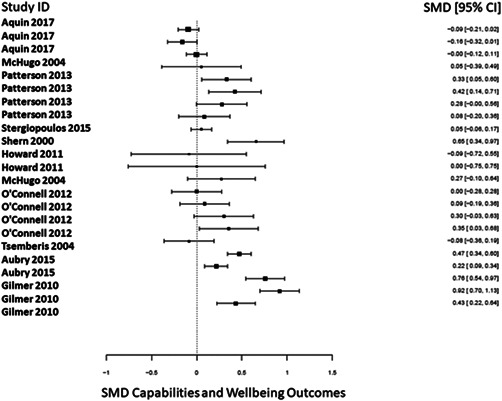

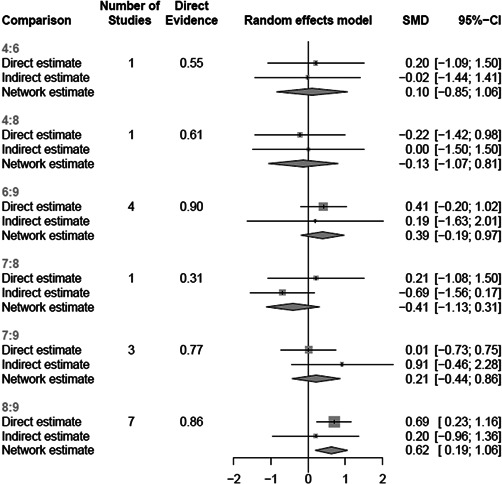

As presented in Table 2, interventions varied considerably between studies, with some evaluating Housing First interventions (e.g., Brown et al., 2016; Goering et al., 2011) and others evaluating accommodation with specific services like case management (e.g., Sosin et al., 1996) and enhanced care (Milby et al., 1996). The most common aspect of the interventions was providing accommodation alongside some other form of additional service such as case management (e.g., Sosin et al., 1996), continuum of care (e.g., Gulcur et al., 2003), and other services delivered through a supportive housing approach (e.g., Lipton et al., 2000).