Abstract

Background

Multiagency responses to reduce radicalisation often involve collaborations between police, government, nongovernment, business and/or community organisations. The complexities of radicalisation suggest it is impossible for any single agency to address the problem alone. Police‐involved multiagency partnerships may disrupt pathways from radicalisation to violence by addressing multiple risk factors in a coordinated manner.

Objectives

-

1.

Synthesise evidence on the effectiveness of police‐involved multiagency interventions on radicalisation or multiagency collaboration

-

2.

Qualitatively synthesise information about how the intervention works (mechanisms), intervention context (moderators), implementation factors and economic considerations.

Search Methods

Terrorism‐related terms were used to search the Global Policing Database, terrorism/counterterrorism websites and repositories, and relevant journals for published and unpublished evaluations conducted 2002–2018. The search was conducted November 2019. Expert consultation, reference harvesting and forward citation searching was conducted November 2020.

Selection Criteria

Eligible studies needed to report an intervention where police partnered with at least one other agency and explicitly aimed to address terrorism, violent extremism or radicalisation. Objective 1 eligible outcomes included violent extremism, radicalisation and/or terrorism, and multiagency collaboration. Only impact evaluations using experimental or robust quasi‐experimental designs were eligible. Objective 2 placed no limits on outcomes. Studies needed to report an empirical assessment of an eligible intervention and provide data on mechanisms, moderators, implementation or economic considerations.

Data Collection and Analysis

The search identified 7384 records. Systematic screening identified 181 studies, of which five were eligible for Objective 1 and 26 for Objective 2. Effectiveness studies could not be meta‐analysed, so were summarised and effect size data reported. Studies for Objective 2 were narratively synthesised by mechanisms, moderators, implementation, and economic considerations. Risk of bias was assessed using ROBINS‐I, EPHPP, EMMIE and CASP checklists.

Results

One study examined the impact on vulnerability to radicalisation, using a quasi‐experimental matched comparison group design and surveys of volunteers (n = 191). Effects were small to medium and, aside from one item, favoured the intervention. Four studies examined the impact on the nature and quality of multiagency collaboration, using regression models and surveys of practitioners. Interventions included: alignment with national counterterrorism guidelines (n = 272); number of counterterrorism partnerships (n = 294); influence of, or receipt of, homeland security grants (n = 350, n = 208). Study findings were mixed. Of the 181 studies that examined mechanisms, moderators, implementation, and economic considerations, only 26 studies rigorously examined mechanisms (k = 1), moderators (k = 1), implementation factors (k = 21) or economic factors (k = 4).

All included studies contained high risk of bias and/or methodological issues, substantially reducing confidence in the findings.

Authors' Conclusions

A limited number of effectiveness studies were identified, and none evaluated the impact on at‐risk or radicalised individuals. More investment needs to be made in robust evaluation across a broader range of interventions.

Qualitative synthesis suggests that collaboration may be enhanced when partners take time to build trust and shared goals, staff are not overburdened with administration, there are strong privacy provisions for intelligence sharing, and there is ongoing support and training.

1. PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

1.1. Limited evidence for police‐involved multiagency partnerships that seek to reduce radicalisation to violence

Multiagency partnerships involving police are often implemented to foster collaboration and reduce radicalisation to violence. There is no clear evidence to support this approach, although a small number of studies provide mixed evidence about the effectiveness of multiagency partnerships for improving collaboration. Some studies offer insights about the costs and ways to best implement multiagency programmes.

1.2. What is this review about?

Police multiagency responses to violent extremism aim to reduce radicalisation to violence by fostering collaboration and partnering with other governmental agencies, private businesses, community organisations, or service providers. Police can play a central role in these partnerships because they are often one of the first points of contact with individuals who have radicalised to extremism.

What is the aim of this review?

This Campbell systematic review examines the processes and impact of police‐involved multiagency partnerships that aim to address terrorism, violent extremism, or radicalisation to violence. The review summarises evidence from five studies that met the impact review criteria and 26 studies that were qualitatively synthesised to explore the processes of multiagency collaboration.

1.3. What studies are included?

This review includes studies that evaluated either the processes or impacts of programmes that involve police acting in partnership with at least one other agency and that were aimed at reducing terrorism, violent extremism or radicalisation to violence.

The systematic search identified 7384 potential studies, of which five assessed the effectiveness of police‐involved multiagency interventions. A total of 181 studies examined how the intervention might work (mechanisms), under what context or conditions the intervention operates (moderators), the implementation factors and economic considerations. Of the 181 studies, 26 studies met the threshold for in‐depth qualitative synthesis to more comprehensively understand the mechanisms, moderators, implementation and economic considerations for police‐involved multiagency interventions.

1.4. What are the findings of this review?

There is not enough evidence to assess whether these programmes work to reduce radicalisation to violence. Only one study assessed the impact of a police‐involved multiagency partnership on radicalisation to violence. This study evaluated the World Organisation for Resource Development Education (WORDE) programme, a Muslim community‐based education and awareness programme involving police in some components.

1.4.1. Do multiagency programmes that aim to reduce radicalisation to violence improve collaboration?

There is a small amount of mixed evidence regarding whether these programmes can work to improve collaborations between agencies. Four studies met the inclusion criteria to assess the impact of a police multiagency partnership on interagency collaboration. The first study examined the impact of agency alignment with a Target Capabilities List (TCL). The evidence from this study showed that greater alignment with the TCL was associated with better working relationships, more intelligence sharing, and more engagement with the U.S. Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), other law enforcement agencies, and fusion centres.

The second study assessed whether the number of multiagency collaborative partners influenced perceptions of clarity and understanding of the strategies and goals of organisations at three levels. Evidence from this study suggests that a larger number of collaborative partners is associated with better understandings of missions, responsibilities and goals at the state and local/departmental level, but not at the federal level, where more partners is associated with less understanding.

The third and fourth studies both examined the impact of grants from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS). One study found a negative direct relationship between the perceptions of the influence of DHS grants, and homeland security preparedness. The final study found that the receipt of DHS funding did not significantly predict whether or not an agency engaged in at least one form of homeland security innovation.

1.4.2. What processes facilitate or constrain implementation of this intervention?

Twenty‐six studies met our threshold for more thorough examination of the processes that facilitate or constrain implementation, as well as providing information about the costs and benefits of the programme. Some themes that emerged include the importance of taking time to build trust and shared goals among partners; not overburdening staff with administrative tasks; targeted and strong privacy provisions in place for intelligence sharing; and access to ongoing support and training for multiagency partners.

1.5. What do the findings of this review mean?

There is limited and mixed evidence about the processes and impact of police‐involved multiagency programs aimed at reducing radicalisation to violence. Only five initiatives so far have been evaluated for effectiveness, and with low quality methods. A larger number of studies (181) provide insights in the context, functioning and cost effectiveness of police‐involved multiagency initiatives, with 26 higher‐quality studies synthesised in‐depth. Future research should aim to rigorously evaluate the outcomes of such initiatives.

1.6. How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies conducted between January 2002 and December 2018.

2. BACKGROUND

2.1. The problem, condition or issue

Violent radicalisation is a complex problem, complicated by the lack of a clear terrorist profile and variation in the risk factors that predict violent extremism across individuals and groups (Campelo et al., 2018; Carlsson et al., 2020; Desmarais et al., 2017; Wolfowicz et al., 2019). While models of understanding radicalisation vary (Borum, 2015; Christmann, 2012; Desmarais et al., 2017; Horgan, 2008; Koehler, 2017; Kruglanski et al., 2019; Sarma, 2017), it is broadly defined as the process by “which a person adopts extremist views and moves towards committing a violent act” (Hardy, 2018, p. 76; Irwin, 2015; Jensen et al., 2018). Radicalisation has been linked with individual and group engagement in terrorist attacks against innocent civilians (Wilner & Dubouloz, 2010), as well as individuals entering conflict zones to join formal extremist groups to engage in violent combat (Lindekilde et al., 2016). As a result, radicalisation has become a key focus for counterterrorism and violence prevention interventions.

The complex and varied nature of individuals' progression from radicalisation to violence presents challenges for designing and evaluating appropriate interventions and policy responses (Hafez & Mullins, 2015; Helmus et al., 2017; Horgan, 2008; Horgan & Braddock, 2010; Jensen et al., 2018; Kruglanski et al., 2019). This level of complexity has driven national counterterrorism policy agendas to adopt intersectoral and multiagency responses that aim to address various radicalisation processes and risks (Beutel & Weinberger, 2016). These multiagency responses often involve partnerships and collaborations between various different agencies and entities (Hardy, 2018), such as governmental agencies, private businesses, community organisations, and service providers.

Multiagency interventions can provide a framework for pooling and sharing resources to address a common problem (Crawford, 1999; Rosenbaum, 2002), such as radicalisation to violence. Yet they can be challenging to implement, and their effectiveness may be influenced by the quality and nature of the collaboration between agencies (see Berry et al., 2011 for review; Atkinson, 2019; Gittell, 2006; Kelman et al., 2013; McCarthy & O'Neill, 2014; Rosenbaum, 2002). Multiagency interventions may be conceptualised on a continuum, with activities ranging from minimal collaboration to a wholistic integration of agencies and organisations (Atkinson, 2019). As a result, the outcomes of multiagency interventions may vary depending on where the intervention falls—or is perceived to fall—on this collaborative continuum (Atkinson, 2019). Partnerships can enhance formal and informal communication, trust, respect, shared goals, and knowledge (Bond & Gittell, 2010). Conversely, partnership‐based interventions may highlight a number of shortcomings in service delivery including the disjointed nature of services, the need for significant stakeholder buy‐in, the isolation for some of the organisations or individuals, and the resource‐intensive nature of many of these collaborations (Atkinson, 2019; Bond & Gittell, 2010; Crawford, 1999; McCarthy & O'Neill, 2014; Youansamouth, 2019). There is also the possibility that multiagency approaches could lead to adverse outcomes (Galloway, 2017; Norton, 2018). For example, multiagency responses that have poor levels of coordination and communication could lead to cases falling through the cracks where no one agency responds under the misguided assumption that another partner agency is taking the lead (Richards, 2017; Smith et al., 1992). Ransley (2016) also raises the possibility of coercion from multiagency responses. Therefore, when assessing the effectiveness and the intended outcomes of multiagency interventions, it is also important to consider the context, potential backfire effects, and quality of the processes underpinning multiagency collaboration.

A broad range of agencies and experts can be involved in multiagency approaches for reducing radicalisation to violence or violent extremism (Weine et al., 2017). Nevertheless, the police are often one of the first points of contact with individuals who have radicalised to extremism. The police are also the first point of call for those who are concerned about or report known associates, friends or family members as being at‐risk of radicalisation. As such, police are important partners for identifying, reducing and building resilience to radicalisation (Cherney, 2015). This review will, therefore, focus on the effectiveness of police‐involved multiagency interventions for reducing radicalisation to violence and improving multiagency collaboration.

2.2. The intervention

Multiagency interventions are characterised by two or more entities partnering to solve a shared problem. These entities may be government agencies (such as education, immigration, customs, home affairs, employment, housing, health), or nongovernmental agencies, including: local councils; businesses; community organisations (such as churches, mosques and other houses of worship) and service providers (such as resettlement agencies, local health providers). This review included any multiagency intervention, where at least one of those partners is the police and where the intervention explicitly aims to address terrorism, violent extremism or radicalisation to violence. This type of intervention can include a range of approaches, including: police engaging with different community and agency stakeholders to help identify terrorist threats (Innes et al., 2011; Ramiriz et al., 2013); police working with other agencies to refer, assess, or case‐manage individuals convicted of terrorism or identified as at‐risk for radicalisation (Cherney & Belton, 2019); or police forming task forces or partaking in regular structured meetings with other agencies to problem‐solve issues pertaining to radicalisation or extremism (Koehler, 2016).

2.3. How the intervention might work

Some observe that there is a great deal of heterogeneity in the risk factors and triggers for radicalisation (Dalgaard‐Nielsen, 2010, 2018; Horgan, 2009). This means there is a variety of risk and background factors that may lead an individual (or a group of individuals) to radicalise to violent extremism (Campelo et al., 2018; Carlsson et al., 2020; Vergani et al., 2018). Research also demonstrates the complex nature of different progression pathways from radicalisation to violence (Horgan, 2008; Kruglanski et al., 2019, 2020). The literature is, therefore, in agreement that the complex nature of radicalisation risk and pathway processes to violence makes it difficult for any single agency, organisation or entity to address the problem alone (Dalgaard‐Nielsen, 2018). As such, interventions to address the problem of radicalisation to violence are often characterised by multiagency partnerships, working across different service delivery sectors (see e.g., Cherney & Belton, 2019; Innes et al., 2011).

Multiagency partnerships may disrupt pathways from radicalisation to violence by collectively addressing multiple risk factors in a holistic and coordinated manner (Butt & Tuck, 2014). The multiagency approach to tackling violent extremism may be effective because it fosters a coordination of effort (Kelman et al., 2013), draws from a broad range of expertise (Crawford, 1999), allows for information and intelligence sharing (Cherney, 2018; Murphy, 2008; Slayton, 2000), and enables the pooling of resources (Crawford, 1999; Sestoft et al., 2017).

El‐Said (2015) describes a range of different ways that multiagency partnerships operate: by formal and informal arrangements, such as legislative or regulatory frameworks, memoranda of understanding or policy standards stipulating channels for information sharing or better interpersonal relations between agencies (see also Koehler, 2016). These arrangements create opportunities for referrals being made from various sources (Koehler, 2017), increasing the capacities for partnerships to detect and respond to those at early pathways to radicalisation and violence. The capacities of multiagency partnerships to better detect and respond to problems over and above what is possible by agencies or entities working alone are enhanced through better information sharing and referral processes (Cherney, 2018; Murphy, 2008; Slayton, 2000). Partnerships can enhance programme planning and design so that counter radicalisation strategies address the required risks and vulnerabilities amongst individuals and groups (Koehler, 2017). The range of expertise across multiagency partners also help to enhance programme implementation by ensuring that all required components of a strategy are delivered (Crawford, 1999). They are likewise important in relation to programme evaluation by enabling the sharing of data that can be used to assess programme effectiveness (Cherney, 2018).

2.4. Why it is important to do the review

Police cannot tackle the problem of radicalisation, violent extremism, and terrorism on their own (Cherney & Hartley, 2017). Many of the risk factors for radicalisation and violent extremism are complex (Dawson et al., 2016; Hafez & Mullins, 2015; Kruglanski et al., 2019, 2020). Research suggests that it is not just the presence of risk factors, but rather the accumulation of risk factors (Campelo et al., 2018; Carlsson et al., 2020; Simi et al., 2016) and what Vergani et al. (2018) describe as the push, pull and personal nature of the radicalisation process. The complexity of the process, therefore, can trigger a range of different vulnerabilities. Some of these vulnerabilities relate to a lack of sense of belonging (Harris‐Hogan, 2014), which requires different institutional responses spanning the family, educational and work context, all of which contribute to the formation of a sense of identity (Kruglanski et al., 2019).

The complexity and variability of the radicalisation process provides an opportunity for police to partner with various agencies and community groups to tackle radicalisation in a multifaceted manner. As such, multiagency interventions have become an important approach to tackle the problem of radicalisation and violent extremism (Butt & Tuck, 2014; Mucha, 2017; Sestoft et al., 2017). Existing evidence, however, does not provide a clear understanding of the effectiveness of police‐involved, multiagency approaches to radicalisation (Cherney & Hartley, 2017; Koehler, 2017; MacDonald, 2002). In addition, there are no existing reviews of multiagency programs, with police as partner, for addressing radicalisation to violence.1 Given the cost of forming multiagency interventions and the organisational complexities of managing and maintaining these types of responses, it is imperative to know whether current multiagency approaches that include police partners are effective for reducing radicalisation to violence and enhancing multiagency collaboration. Policy makers, practitioners, and researchers also need to understand not only whether the intervention works, but also how the intervention works (mechanisms), under what conditions or contexts (moderators), and what the implementation considerations and cost implications are.

This review aims to fill a significant gap in the evidence‐based literature for countering violent extremism in two ways. First, by quantitatively synthesising the existing evidence for the impact of multiagency police‐involved programs on violent radicalisation or multiagency collaboration. Second, by qualitatively synthesising research that reports on the mechanisms, moderators, implementation considerations, and economic information pertaining to police‐involved multiagency programs that aim to counter radicalisation to violence. The results from this review will inform future decision‐making regarding the design and evaluation of multiagency programs by synthesising the evidence for their effectiveness, identifying potential gaps in the evidence‐base, and providing insight into what level of investment is required for the implementation and evaluation of primary studies.

3. OBJECTIVES

The first objective of this review (Objective 1) is to answer the question: how effective are police‐involved multiagency interventions at reducing radicalisation to violence or improving multiagency collaboration? As part of this objective, the review also aimed to ascertain if the effectiveness of police‐involved multiagency interventions varies by geographical location, target population, nature of the intervention approach (e.g., number of components, specific intervention techniques), and number and type of multiagency partners. The second objective of this review (Objective 2) is to qualitatively synthesise pertinent information about how police‐involved multiagency interventions for countering radicalisation to violence might work (mechanisms), under what context or conditions (moderators), the implementation factors, and economic considerations.

4. METHODS

4.1. Criteria for considering studies for this review

4.1.1. Types of studies

To fulfil the objectives of this review, two types of studies will be included. The specific type of studies used to address each review objective may overlap, and are detailed in the subsections below.

Types of study designs for review of effectiveness (Objective 1)

To be included in the review of effectiveness (Objective 1), a study needed to be a quantitative impact evaluation that employed a randomised experimental (e.g., RCT) or a quasi‐experimental design with a comparison group that does not receive the intervention. Eligible comparison groups were: “business‐as‐usual” treatment, no intervention, or an alternative intervention (treatment‐treatment designs).

Rigorous quasi‐experimental studies can also be used to estimate causality, particularly when the research design includes strategies to minimise threats to internal validity (see Farrington, 2003; Shadish et al., 2002). Strategies for reducing threats to internal validity may include: controlling case assignment to treatment and comparison groups (regression discontinuity), matching characteristics of the treatment and comparison groups (matched control), statistically accounting for differences between the treatment and comparison groups (designs using multiple regression analysis), or providing a difference‐in‐difference analysis (parallel cohorts with pre‐ and posttest measures). The following “strong” quasi‐experimental designs were eligible for this review:

Cross‐over designs

Regression discontinuity designs

Designs using multivariate controls (e.g., multiple regression)

Matched control group designs with or without preintervention baseline measures (propensity or statistically matched)

Unmatched control group designs without preintervention measures where the control group has face validity

Unmatched control group designs with pre‐post intervention measures which allow for difference‐in‐difference analysis

Short interrupted time‐series designs with control group (<25 preintervention and 25 postintervention observations (Glass, 1997)

-

Long interrupted time‐series designs with or without a control group (≥25 preintervention and postintervention observations (Glass, 1997)

Less rigorous quasi‐experimental designs can be used to illustrate the magnitude of the relationship between an intervention and an outcome, yet have limitations for establishing causality. Therefore, we excluded the following weaker quasi‐experimental designs in the synthesis of intervention effectiveness:

Raw unadjusted correlational designs where the variation in the level of the intervention is compared to the variation in the level of the outcome; and

Single group designs with pre‐ and postintervention measures.

Types of study designs for review of mechanisms, moderators, implementation and economic considerations (Objective 2)

To be included in the qualitative synthesis of the potential mechanisms, moderators, implementation factors, and economic considerations related to the intervention (Objective 2), each study needed to be (a) already included in the quantitative synthesis of impact evaluations (see above for review Objective 1); or (b) be an empirical study reporting on an eligible intervention. To be an empirical study, the authors must have either reported on primary quantitative or qualitative data or conducted secondary analysis of primary quantitative or qualitative data. We acknowledge that qualitative studies may not present “data” per se, but report on empirical work such as textual themes from key informant interviews or focus groups, or information gathered by observational methods (e.g., participant‐observers). Purely theoretical work, opinion pieces or research reports that only summarised, referenced or described previous intervention studies were not used for the qualitative synthesis.

4.1.2. Types of participants

For both the review of effectiveness (Objective 1) and the review of mechanisms, moderators, implementation and economic considerations (Objective 2), this review included studies that use any of the following populations:

-

1.

Individuals of any age, gender, or ethnicity; or

-

2.

Micro places (e.g., street corners, buildings, police beats, street segments); or

-

3.

Macro places (e.g., neighbourhoods, communities, police districts).

We placed no limits on the geographical region reported in the study. Specifically, we included studies conducted in high‐, low‐ and middle‐income countries.

4.2. Types of interventions

For both the review of effectiveness (Objective 1) and the review of mechanisms, moderators, implementation, and economic considerations (Objective 2), we included any police‐involved multiagency intervention that aimed to address terrorism, violent extremism or radicalisation to violence. Specifically, each study must have met two intervention criteria:

-

1.

Report on a multiagency intervention where police are a partner, defined as some kind of a strategy, technique, approach, activity, campaign, training, programme, directive, or funding/organisational change that involved police and at least one other agency (Higginson, Eggins, et al., 2015). Police involvement was broadly defined as:

Police initiation, development or leadership;

Police are recipients of the intervention or the intervention is related, focused or targeted to police practices or

Delivery or implementation of the intervention by police.

The other agencies or entities involved in the intervention could be government or nongovernmental agencies, including government agencies (e.g., education, immigration, customs, home affairs, employment, housing, health), local councils, businesses, communities (e.g., churches, mosques and other houses of worship), and services providers (e.g., resettlement agencies, local health providers).

AND

-

2.

Report on a multiagency intervention with police as a partner that aimed to address terrorism, violent extremism, or radicalisation to violence, as defined or specified by study authors.

We anticipated that multiagency interventions with police as a partner that aim to address terrorism, violent extremism or radicalisation to violence may include:

Police being trained OR police training or educating partner(s), to improve recognition, referral and responses to radicalisation, including guiding at‐risk populations towards numerous forms of support services offered by various partnerships, such as life skills mentoring, anger management sessions, and cognitive/behavioural therapy (Home Office, 2015a).

Community awareness programs or training delivered to police OR police delivering community awareness training or programs to partner(s) to help partner(s) identify someone who may already be engaged in illegal terrorist‐related activity and are referred to the police (Home Office, 2009).

Police working in partnership with universities to train, engage, intervene and consult on action plans to reduce at‐risk youth to extremist messaging (Angus, 2016).

Approaches that involve police working with other agencies to refer, assess, or case‐manage individuals convicted of terrorism or identified as at‐risk of radicalisation (Cherney & Belton, 2019).

Police partnering with other agencies to address radicalisation or extremism through regular structured/unstructured focus groups or meetings that may or may not be formalised (e.g., memoranda of understanding) or by forming task forces or multiagency intervention teams.

Police working with external agencies to divert an individual away from violent extremism (e.g., UK Channel program, Home Office, 2015b).

Police officers undertaking various forms of engagement with different community and agency stakeholders to help identify terrorist threats (Innes et al., 2011; Ramiriz et al., 2013).

4.2.1. Types of outcome measures

Types of outcome measures for review of effectiveness (Objective 1)

For the review of effectiveness (Objective 1), we included studies with two main categories of outcomes. The first was radicalisation to violence. For the purposes of this review, radicalisation to violence was defined as the process by “which a person adopts extremist views and moves towards committing a violent act” (Hardy, 2018, p. 76; Jensen et al., 2018). It is important to note that “radicalisation” remains inconclusively defined in the literature (Heath‐Kelly, 2013) and violence is just one potential outcome of radicalisation (Angus, 2016; Hafez & Mullins, 2015; Schmid, 2013). We also recognise that terminology in the extant literature (e.g., radicalisation and extremism) is often used interchangeably (Borum, 2012), and that outcomes may not be labelled explicitly as “radicalisation to violence”. Other labels that may be used include: radicalisation (Horgan, 2009), extremism, violent extremism (Khalil & Zeuthen, 2016), political violence, ideologically motivated violence, political extremism (Lafree et al., 2018), violent radicalisation (Bartlet & Miller, 2012) and terrorism (Christmann, 2012).

We included outcome data measured through self‐report instruments, interviews, observations and/or official data (e.g., contact with police, calls‐for‐service reporting incidents, arrests, charges, prosecution, sentencing and correctional data). Some examples of how radicalisation to violence can be measured include:

Violent Extremist Risk Assessment‐2 (VERA‐2): A risk assessment of the “likelihood of future violence by an identified offender who has been convicted of unlawful ideologically motivated violence” (RTI International, 2018, p. 10; Pressman & Flockton, 2012).

Extremist Risk Guidance Factors (ERG 22+): Assesses the needs and risks of offenders who have either been convicted of an extremist offence or have shown behaviours or attitudes that raise concerns about their potential to commit extremist offences (Knudsen, 2020).

IAT‐8: Assesses the effectiveness of a current intervention at reducing or altering the level of vulnerability to radicalisation (RTI International, 2018).

RADAR assessments: Identifies “individuals who would benefit from services to help them disengage from violent extremism” (RTI International, 2018, p. 10) by assessing a variety of observations including religious understanding and knowledge, radicalisation source, intervention goals and progress undertaken to achieve these goals (Cherney & Belton, 2019)

Terrorist Radicalisation Assessment Protocol (TRAP‐18): A professional judgement instrument for risk and threat assessment of individuals who may engage in lone‐actor terrorism (Meloy, 2018).

The second outcome category in the review was multiagency collaboration, broadly defined as a measure that relates to the quality and nature of the partnership between the agencies involved in the intervention. The quality and nature of collaborations or partnerships can be operationally defined in different ways, ranging from the degree of practical sharing of resources (Rosenbaum, 2002) to relational perspectives that encompass variables such as: frequency and quality of communication, shared goals and knowledge, and trust or respect (Bond & Gittell, 2010; Gittell, 2006). This review included both practical and relational measures of collaboration, captured by self‐report or official/administrative data, in one or more of the following categories:

Information sharing (e.g., frequency, quality);

Perceptions of trust, respect, or legitimacy within multiagency collaborations or

Degree of shared goals and understanding between multiagency partners.

Types of outcome measures for review of mechanisms, moderators, implementation and economic considerations (Objective 2)

To be included in the qualitative synthesis of the potential mechanisms, moderators, implementation factors and economic considerations (Objective 2), no specific outcome measures were required. Any empirical study of a police‐involved multiagency programme that aimed to address terrorism, violent extremism, or radicalisation to violence was examined for empirical qualitative or quantitative data pertaining to mechanisms, moderators, implementation or economic considerations (see Supporting Information Appendix C for definitions). We note the differences in the conceptualisation of “outcomes” for quantitative and qualitative studies, whereby qualitative studies may not distinguish between different types of variables such as independent, predictor, outcome, moderator or mediator variables. Rather, qualitative studies are likely to present thematic textual data drawn from interviews, focus groups or observational methods. In addition, study authors may use mechanism, moderator, implementation and economic variables as outcome variables, or they may use data within these domains as mediators or moderators to explore their impact on study outcomes. To provide a comprehensive synthesis of potential mechanisms, moderators, implementation factors, and economic considerations, we included empirical studies that reported on data in any of these domains, regardless of whether the data are conceptualised as an “outcome variable”.

4.2.2. Duration of follow‐up

For both the review of effectiveness (Objective 1) and the review of mechanisms, moderators, implementation, and economic considerations (Objective 2), we included studies with follow‐up periods of any length. If there was variation in the length of follow‐up across studies, we planned to group and synthesise studies with comparable follow‐up durations. For example, short (e.g., 0–3 months postintervention), medium (>3, <6 months) and long‐term follow‐up (>6 months postintervention). While this was not required for this review, we will take this approach in future updates to the review.

4.2.3. Types of settings

We aimed to include studies reporting on an impact evaluation of an eligible intervention using eligible participants, outcome(s) and an eligible research design in any setting. Where there were multiple conceptually distinct settings, we planned to synthesise the studies within the settings separately. However, due to the paucity of information about study settings, we were unable to take this synthesis approach.

We assessed titles/abstracts and full‐text documents that were conducted or published between January 2002 and December 2018. Titles/abstracts published in a language other than English were translated using Google Scholar to identify if they were potentially eligible for the review. If eligibility could not be determined using Google Translate, the first author of the study was contacted to ascertain eligibility. If there was no response from the author or their contact details could not be located, the study was included in the “References to studies awaiting classification” section.

4.3. Search methods for identification of studies

The full search record for this review is provided in Supporting Information Appendix A. Electronic, grey literature, trial registry, and journal hand searches were conducted between November 2019 and March 2020. Reference harvesting, forward citation searching, and consultation with experts was conducted in November 2020. The overall search captured research conducted or published between January 2002 and December 2018. Due to the search functionalities of some websites, there was no ability to restrict searches to this date range, and so research from all publication years was assessed for eligibility.

4.3.1. Electronic searches

The search for this review was led by the Global Policing Database (GPD) research team at the University of Queensland (Elizabeth Eggins, Lorelei Hine and Lorraine Mazerolle) and Queensland University of Technology (Angela Higginson). The University of Queensland is home to the GPD (www.gpd.uq.edu.au), which served as the main search location for this review. The GPD is a web‐based and searchable database designed to capture all published and unpublished experimental and quasi‐experimental evaluations of policing interventions conducted since 1950. There are no restrictions on the type of policing technique, type of outcome measure or language of the research (Higginson, Benier, et al., 2015). The GPD is compiled using systematic search and screening techniques, which are reported in Higginson, Eggins, et al. (2015) and summarised in Supporting Information Appendix B. Broadly, the GPD search protocol includes an extensive range of search locations to ensure that both published and unpublished research is captured across criminology and allied disciplines.

The GPD systematic search uses a broad range of policing and research search terms and systematically progresses the screening of the captured research in sequential stages with increasing specificity. At the initial title and abstract screening stage, records identified by the systematic search are screened on whether they are broadly about police or policing (see Higginson, Benier, et al., 2015). At subsequent full‐text screening stages, documents retained at the initial stage are then screened on whether they report on a quantitative impact evaluation of an intervention relating to police or policing, with no limits on outcome measures. As a result, refined corpuses of policing research can be searched and extracted from the GPD without the need to use policing search terms. Because our review captured both quantitative and qualitative studies of eligible interventions, we extracted data from the GPD from the point of title and abstract eligibility (i.e., is the document broadly about police or policing). We searched the title and abstracts within this corpus published between 2002 and 2018, using the following search terms: *terror* OR extrem* OR *radical*.

4.3.2. Searching other resources

We also employed strategies to extend the GPD search. This included:

Searching trial registries (those not indexed by WHO, but listed on the Office for Human Research Protections website https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/international/clinical-trial-registries/index.html;

Searching counterterrorism organisation websites (see Table 1);

Conducting reference harvesting on existing reviews and eligible studies;

Forward citation searching for all documents eligible for review Objective 1;

Liaising with the Five Country Research and Development Network (5RD), and the DHS Advisory Board network for the Campbell Collaboration grants, to enquire about eligible studies that may not be publicly available;

Personally contacting prominent scholars in the field and authors of eligible studies to enquire about eligible studies not yet disseminated or published; and

- Hand‐searching the following journals to identify eligible documents published in the 12 months prior to the systematic search date that may not have been indexed in academic databases:

-

a.Critical Studies on Terrorism

-

b.Dynamics of Asymmetric Conflict

-

c.Intelligence and Counter Terrorism

-

d.International Journal of Conflict and Violence

-

e.Journal for Deradicalization

-

f.Journal of Policing

-

g.Perspectives on Terrorism

-

h.Police Quarterly

-

i.Policing—An international Journal of Police Strategies and Management,

-

j.Policing & Society

-

k.Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression

-

l.Studies in Conflict & Terrorism

-

m.Terrorism & Political Violence

-

a.

Table 1.

Grey literature search locations

| Organisation | Website |

|---|---|

| Global Terrorism Research Centre (Monash University) | http://artsonline.monash.edu.au/gtrec/publications/ |

| Triangle Centre on Terrorism and Homeland Security | https://sites.duke.edu/tcths/ |

| Department of Homeland Security | https://www.dhs.gov/topics |

| Public Safety Canada | https://www.publicsafety.gc.ca/index-en.aspx |

| National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START) | https://www.start.umd.edu/ |

| Terrorism Research Centre | http://www.terrorism.org/ |

| Global Centre on Cooperative Security | https://www.globalcentre.org/publications/ |

| Hedayah | http://www.hedayahcentre.org/publications |

| RAND Corporation | https://www.rand.org/topics/terrorism.html?content-type=research |

| Radicalization Awareness Network (RAN) | https://ec.europa.eu/home-affairs/what-we-do/networks/radicalization_awareness_network_en |

| RadicalizationResearch | https://www.radicalizationresearch.org/ |

| Royal United Services Institute (RUSI) | https://rusi.org/ |

| Impact Europe | http://impacteurope.eu/ |

| National Criminal Justice Reference Service | https://www.ncjrs.gov/App/AbstractDB/AbstractDBSearch.aspx |

| Terrorism Research Centre (University of Arkansas) | https://terrorismresearch.uark.edu |

| International Association of Law Enforcement Intelligence Analysts | https://www.ialeia.org |

| Naval Post‐Graduate School | https://nps.edu |

4.4. Data collection and analysis

4.4.1. Selection of studies

Title and abstract screening

After removal of duplicates and ineligible documents types (e.g., book reviews, blog posts), all records captured by the systematic search were imported into review management software, SysReview (Higginson & Neville, 2014). Two review authors (E. E. and L. H.)—with assistance from trained research staff—screened the titles and abstracts for all records identified by the search according to the following exclusion criteria:

-

1.

Ineligible document type (e.g., book review);

-

2.

Record is not unique (i.e., duplicate);

-

3.

Record is not about policing terrorism, radicalisation, or extremism.

Prior to independent screening, all staff engaged in title and abstract screening assessed the same set of 50 records and two review authors (E. E. and L. H.) compared their judgements to verify consistent decision‐making and provide feedback to each screener. In addition, a sample of 10% of all excluded titles and abstracts across all screeners were cross‐checked for accuracy by one review author (L. H.) and any disagreements were mediated by a different review author (E. E.).

Although all efforts were made to remove ineligible document types and duplicates prior to screening, automated and manual cleaning can be less than perfect. As such, the first two exclusion criteria were used to remove ineligible document types and duplicates prior to screening each record on substantive content relevance. It is important to note that “policing” is broadly operationalised in both the GPD screening and the screening for this review. Specifically, a title and abstract can be screened as being about policing if, for example: police are study participants, police are involved in implementing an intervention (alone or in partnership with others), or the focus of the research appears to be police tools, technologies or techniques (see Higginson, Benier, et al., 2015).

All potentially eligible records then progressed to full‐text eligibility screening. Most records indexed in the GPD have a pre‐existing full‐text document. However, records from the additional searches that were deemed as potentially eligible at the title and abstract screening stage progressed to literature retrieval, where attempts were made to locate the full‐text document. Where full‐text documents could not be retrieved via existing university resources, they were ordered through the review authors' university libraries. If the full‐text document could not be located, the abstract was used to assess whether the study met full‐text eligibility criteria. Where a decision could not be unequivocally made about eligibility based on the abstract, the record was categorised as a study awaiting classification (see “References to studies awaiting classification” section).

Full‐text eligibility screening

Two review authors (E. E. and L. H.)—with assistance from trained research staff—screened the full‐text of each document for final eligibility using a two‐stage process. The following exclusion criteria was used for the first stage of screening:

-

1.

Ineligible document type (e.g., book review);

-

2.

Document is not unique (i.e., duplicate);

-

3.

Document does not refer to an eligible intervention;

-

4.

Document does not report on an empirical study of a multiagency intervention with police as a partner that aims to address radicalisation, terrorism, or extremism.

While all efforts were made to remove ineligible document types and duplicate documents in earlier stages, these types of records can occasionally progress into later stages of screening (e.g., where duplicate records are not adjacent to each other during screening or where screeners cannot unequivocally determine the document type based on the title and abstract). Therefore, the first two exclusion criteria were used to remove ineligible document types and duplicates before they progressed to the more time‐intensive full‐text screening on inclusion criteria.

The purpose of the second stage of screening was to categorise studies according to the review objectives. Specifically, screeners were asked to determine whether each study was (a) a quantitative impact evaluation of an eligible intervention, using an eligible research design, outcomes, and participants; (b) an empirical (qualitative and/or quantitative) study describing the implementation factors, economic considerations, moderators, and/or mechanisms of an eligible intervention; or (c) a study that eligible for both (a) and (b).

Two review authors (E. E. and L. H.) trained research staff to screen the documents using a standardised screening companion. Prior to independent screening, each review author or research staff member conducting full‐text document screening was required to screen the same set of 25 documents and their answers were compared against the answers determined by two review authors (E. E. and L. H.). Feedback was provided to all screeners prior to beginning independent screening. A random 5% sample of each screener's exclusion screenings were cross‐checked to identify false negative screening decisions. If a screener's decisions were deemed unreliable due to a high rate of false negatives (), the protocol stated that their exclusion screenings would be reassigned to another screener (Mazerolle, Cherney et al., 2020). There were no instances of high false negative screening decisions. Any disagreements in determining a study's final eligibility for the review were resolved via discussion with a third review author (A. H.).

4.4.2. Data extraction and management

Eligible documents were coded using the coding companion provided in Supporting Information Appendix C. The level of coding was dependent on the category each study was assigned. Data pertaining to the general study characteristics (e.g., document type, study location) were extracted for all studies.

For studies eligible for the review of effectiveness (Objective 1), data was extracted according to the following general domains:

-

1.

Participants (e.g., sample characteristics by condition, attrition)

-

2.

Intervention (e.g., intervention components, intensity, setting)

-

3.

Outcomes (e.g., conceptualisation, mode of measurement, time‐points)

-

4.

Research methodology (e.g., design, unit and type of assignment)

-

5.

Effect size data

-

6.

Risk of bias

For studies eligible for the review of mechanisms, moderators, implementation and economic considerations (Objective 2), each study was first rated on the quality of the evidence across the mechanism, moderator, implementation and economic domains. We used the EMMIE (Effectiveness, Mechanisms, Moderators, Implementation, Economics) appraisal tool developed by Johnson et al. (2015) to guide our decisions (see Table 2). In addition to the criteria delineated by Johnson et al. (2015), to reach a rating of 3 or 4 on the mechanism and moderator domains, studies needed to explicate an independent intervention variable that fit the eligibility criteria for this review, measure an explicit moderator or mechanism, and measure and report on a separate dependent variable.

Table 2.

EMMIE appraisal tool

| Domain | Rating |

|---|---|

| Mechanism |

0 = No reference to theory, simple black box 1 = General statement of assumed theory 2 = Detailed description of theory, drawn from prior work 3 = Full description of the theory of change and testable predictions generated from it 4 = Full description of the theory of change and robust analysis of whether it is operating as expected |

| Moderator |

0 = No reference to relevant contextual conditions that may be necessary 1 = Ad hoc description of possible relevant contextual conditions 2 = Test the effects of contextual conditions defined post hoc using available variables 3 = Theoretically grounded description of relevant contextual conditions 4 = Collection and analysis of relevant data relating to theoretically grounded moderators and contexts |

| Implementation |

0 = No account of implementation or implementation challenges 1 = Ad hoc comments on implementation or implementation challenges 2 = Concerted efforts to document implementation or implementation challenges 3 = Evidence‐based account of levels of implementation or implementation challenges 4 = Complete evidence‐based account of implementation or implementation challenges and specification of what would be necessary for replication elsewhere |

| Economics |

0 = No mention of costs and/or benefits 1 = Only direct or explicit costs and/or benefits estimated 2 = Direct or explicit and indirect costs and/or benefits estimated 3 = Marginal or total or opportunity costs and/or benefits estimated 4 = Marginal or total or opportunity costs and/or benefits estimated by bearer (or recipient) estimated |

Source: Adapted from Thornton et al. (2019).

For studies that reached a rating of 3 or more on any of the mechanism, moderator, implementation and economic domains, data were extracted according to the following (see also “Treatment of qualitative research” section):

-

1.

Research approach (e.g., design, sampling)

-

2.

Participant characteristics

-

3.

Mechanisms that may explain intervention outcomes

-

4.

Moderators that may impact intervention outcomes

-

5.

Implementation considerations (e.g., barriers or facilitators)

-

6.

Economic considerations

For studies that did not meet a rating of 3 on any domain using the EMMIE tool, we coded each study according to document type, setting, intervention, participants, research approach and rating of the level of evidence for mechanisms, moderators, implementation and economics domain.

We anticipated that some studies included in the effectiveness component of the review (Objective 1) may report information eligible for the mechanism, moderator, implementation and economic component of the review (Objective 2), yet this information may not be collected, analysed or reported in the same way as the effectiveness data. Therefore, if studies were eligible for both components data were extracted according to both of the abovementioned frameworks.

All studies eligible for the review of effectiveness (Objective 1) were independently double coded. For studies eligible for the Objective 2 with a rating of three or more on the EMMIE tool, at least one study from each EMMIE domain (Mechanisms, Moderators, Implementation, Economic) and at least one study per coder were independently double coded. The results of this double coding (30% of 26 studies, n = 8) was assessed by one review author (E. E.) prior to independent coding for Objective 2, with feedback provided to coders to ensure consistency. The remaining 18 studies reaching a rating of 3 on the EMMIE tool were independently coded, with the extracted information verified upon synthesis by at least one review author (A. C., E. E., L. H.). The 155 studies included in the qualitative synthesis that did not reach a rating of at least three on the EMMIE tool were independently coded by two study authors (E. E. and L. H.).

4.4.3. Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Due to the nature of the included studies, we selected risk of bias tools most appropriate to the type of research under consideration. In addition, risk of bias assessments were only conducted for the studies included in the effectiveness component (Objective 1, n = 5) and studies included in the Objective 2 that reached a rating of at least one rating of 3 on the EMMIE appraisal tool (n = 26).

Only one study included in the effectiveness component of the review (Objective 1) was a prospective intervention suited to the Cochrane nonrandomised risk of bias tool (ROBINS‐I). This tool guides rating across seven domains to determine low, moderate, serious, or critical risk of bias, or no information to make a judgement (Sterne et al., 2016). The confounding domain assesses whether the study accounts for the baseline and/or time‐varying prognostic factors (e.g., socioeconomic status). The selection domain refers to biases internal to the study in terms of the exclusion of some participants, outcome events, for follow‐up of some participants that is related to both intervention and outcome. The classification of interventions domain refers to differential (i.e., related to the outcome) or nondifferential (i.e., unrelated to the outcome) misclassification of the intervention status of participants. The measurement of outcomes domain assesses whether bias was introduced from differential (i.e., related to intervention status) or nondifferential (i.e., unrelated to intervention status) errors in the measurement of outcome data (e.g., if outcome measures were assessed using different methods for different groups). The deviations from intended interventions refers to differences arising in intended and actual intervention practices that took place within the study. The missing data domain measures bias due to the level and nature of missing information (e.g., from attrition, or data missing from baseline or outcome measurements). Finally, the selection of reported results domain is concerned with reporting results in a way that depends on the findings (e.g., omitting findings based on statistical significance or direction of effect). The results of the risk of bias assessment are provided in a written summary and table. If future updates of the review identify additional eligible studies suited to the ROBINS‐I tool, the results of the risk of bias assessment will also be depicted in a risk of bias summary figure.

The remaining four studies included under Objective 1 were cross‐sectional surveys where one of the independent variables measured an eligible intervention in a way to allow for a counterfactual analysis. These studies were not suited to the ROBINS‐I tool. Consequently, the Effective Public Health Project (EPHPP) tool was used to assess risk of bias. This tool guides the appraisal of studies across six domains: selection bias, study design, confounders, blinding, data collection methods, and withdrawals and drop‐outs. The withdrawals/drop‐outs domain was omitted because the developers state that these questions are not applicable for one‐time survey studies (response rate is captured under questions for the selection bias domain). Based on the guidance specified by the developers, studies are rated as either “strong”, “moderate” or “weak” for each domain. Overall, studies are rated as “strong” (low risk of bias) if they receive no “weak” ratings on any domains, “moderate” if they have only one “weak” rating across domains, or “weak” (high risk of bias) if they receive two or more “weak” ratings across domains.

Five the 26 studies with a rating of 3 or more on the EMMIE appraisal tool that were included in the implementation, mechanisms, moderators, and economics component of the review (Objective 2) were also included in the effectiveness component of the review (Objective 1). As such, the risk of bias for these studies was assessed as outlined above. The risk of bias for the remaining 21 studies was assessed using the suite of CASP critical assessment checklists (https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/). This suite includes a checklist for case‐control studies, cohort studies, economic studies, and qualitative studies, all of which contain questions to guiding the rating for each domain (see Supporting Information Appendix D). The selection of the appropriate checklist was based on the nature of the study under consideration and is delineated in the results section.

4.4.4. Measures of treatment effect

Of the five studies included in the review of effectiveness (Objective 1), only one contained sufficient data to calculate effect sizes and used an outcome falling under the category of radicalisation to violence (Williams et al., 2016). This study used a continuous measure of outcome data collected from individual participants. The independent variable was dichotomous, as the participants were either in the intervention group or the comparison group. The specific data required to calculate effect sizes was not provided in the eligible study reports but was provided by the study authors via personal communication. RevMan was used to calculate standardised mean differences (SMD) and their 95% confidence intervals.

The remaining four studies reported on continuous outcomes that were eligible as a multiagency collaboration outcome category and reported coefficients from statistical tests to represent the intervention effect. It is important to note that the variables that are conceptualised in this review as intervention variables were not the focus of the study, rather, they were one of several independent variables included in the study's models. Carter et al. (2014) reported incident rate ratio (IRR) coefficients from a negative binomial regression model that used an ordinal intervention variable measuring the agency's alignment with DHS TCL. Baldwin (2010) reported the unstandardised coefficients from a linear regression model that used a continuous intervention variable measuring the number of multiagency homeland security partners. Burruss et al. (2012) reported standardised coefficients from structural equation models that used an ordinal intervention variable measuring participants' perception of the influence of partner grants on current homeland security practice. Finally, Stewart and Oliver (2014) reported unstandardised regression coefficients from zero‐inflated negative binomial regression models that used a dichotomous intervention variable measuring whether or not the agency had received homeland security grants.

Where it was possible to calculate a standardised effect size for regression coefficients, we calculated r. The effect size r is interpreted as the number of standard deviation changes in the outcome for every one standard deviation change in the intervention variable, controlling for other predictor variables.

Unstandardised regression coefficients (B) from linear regression models (Baldwin, 2010) and structural equation models (Burruss et al., 2012) were converted to r using the following formulae, and 95% confidence intervals were calculated from r and SE r :

Burruss et al. (2012) reported both the standardised and unstandardised regression coefficients, but did not report SEβ, SDx or SDy to allow calculation of r and the 95% confidence intervals for r. We calculated SDy from the reported data using:

The authors were contacted for additional data, and provided SDx by personal communication.

As there is currently no appropriate method to standardise the coefficients from negative binomial models (Wilson, 2020, personal correspondence), for studies that use negative binomial regression (Carter et al., 2014) or zero inflated negative binomial regression (Stewart & Oliver, 2014) we do not report a standardised effect size for the models presented in these studies. Rather, we describe the results using the metric reported by study authors. Carter et al. (2014) reported their results as exponentiated coefficients or IRRs, and Stewart and Oliver (2014) reported unstandardised coefficients (B). We calculated 95% confidence intervals from these data.

For future updates of this review, we aim to follow the procedures outlined in the protocol to extract and/or calculate measures of treatment effect wherever possible (Mazerolle, Cherney et al., 2020).

4.4.5. Unit of analysis issues

Unit of analysis and/or dependency issues may occur when (a) multiple documents report on a single empirical study; (b) multiple conceptually similar outcomes are reported in the one document; (c) data is reported for multiple time‐points and/or (d) studies have clustering in their research design. None of these issues were relevant when quantifying and synthesising treatment effects for this review. For future updates of this review, our approach for handling these issues is specified in the protocol (Mazerolle, Cherney et al., 2020).

4.4.6. Dealing with missing data

Due to the number of studies included in this review, study authors were only contacted by email to seek missing data if the data would (a) allow for quantitatively synthesising studies via meta‐analysis or reporting effect sizes; or (b) would have changed the risk of bias rating for the study. The results section also specifies which data were obtained from published reports of a study and which data were obtained directly from study authors (not available in the public domain). For future updates of this review, we will follow this procedure.

4.4.7. Assessment of heterogeneity

Due to the inability to conduct meta‐analyses using the studies included in the effectiveness component of this review (Objective 1), we were unable to statistically assess heterogeneity. However, we provide narrative text which explores the differences between the the included studies. For updates of this review, we will implement either this approach or the statistical assessment approach specified in the review protocol (Mazerolle, Cherney et al., 2020).

4.4.8. Assessment of reporting biases

Due to the inability to conduct meta‐analyses using the studies included in the effectiveness component of this review (Objective 1), we were unable to statistically assess reporting/publication biases. For updates of this review, we will implement the approach specified in the review protocol (i.e., inspecting funnel plots for asymmetry, conducting subgroup analyses to assess if the effect sizes from the published and unpublished documents are significantly different).

4.4.9. Data synthesis

Treatment of quantitative evaluation research (Objective 1)

Due to the nature of the studies included in this component of the review, we were unable to conduct meta‐analyses to synthesise the studies. Only one eligible study assessed the impact of the intervention on radicalisation outcomes, and of the four eligible studies using multiagency outcome measures, the disparate intervention and outcomes precluded meta‐analysis. Rather, we describe each study and estimates of treatment effects either using single standardised effect sizes with their corresponding confidence intervals (Williams et al., 2016) or the coefficient reported by study authors where a standardised effect size could not be calculated (Carter et al., 2014; Stewart & Oliver, 2014). For updates of this review, we will use either this approach or the data synthesis approach outlined in the protocol (Mazerolle, Cherney et al., 2020).

Treatment of qualitative research (Objective 2)

For the review of mechanisms, moderators, implementation, and economic considerations (Objective 2) we drew on the EMMIE framework developed by the UK's What Works for Crime Reduction Centre (Johnson et al., 2015; Thornton et al., 2019). This framework aims to structure the extraction and discussion of the Effects of an intervention, the Mechanisms by which the intervention is believed to work, the Moderators that may vary intervention effectiveness (e.g., characteristics of target people or places), Implementation considerations (e.g., required resources, training), and Economic implications for the intervention in terms of costs and benefits (Johnson et al., 2015; Thornton et al., 2019). Objective 1 of this review encompasses the Effectiveness part of the EMMIE framework, so Objective 2 focuses on qualitatively synthesising the mechanisms, moderators, implementation and economic domains. The data extraction for these domains (Supporting Information Appendix C) was adapted from the EMMIE codebook (Tompson et al., 2015), and has been utilised in a number of realist‐informed systematic reviews (e.g., Belur et al., 2017; Sidebottom et al., 2015; see also Gielen, 2015) and for rating the evidence of systematic reviews in the area of criminal justice (see https://whatworks.college.police.uk/toolkit/Pages/Welcome.aspx).

There are multiple approaches available for qualitative synthesis, yet the development of a clear set of guidelines has been a complex and long‐term problem (Booth et al., 2018; Noyes et al., 2019) and many of the methods have not been thoroughly evaluated for use in mixed‐methods systematic reviews (Dixon‐Woods et al., 2005, 2006; Popay et al., 2006; Pope et al., 2007). Explicitly labelling our qualitative synthesis approach is also complicated by the variations in the terminology in the literature and significant overlap in techniques within different synthesis approaches (Booth et al., 2016; Pope et al., 2007).

We used a Framework Synthesis method to synthesise the qualitative data (see Booth et al., 2016), which is an overarching approach that encompasses analogous methods such as content analysis, framework analysis, and aggregate synthesis (see Booth et al., 2016; Booth & Carroll, 2015; Dixon‐Woods et al., 2005, 2006; Dixon‐Woods, 2011; Noyes et al., 2019; Popay et al., 2006). Broadly, these methods use systematic rules or a framework to arrange data into distinct categories that are then synthesised using a variety of techniques such as tables, matrices, and narrative textual summaries (e.g., see Belur et al., 2017; Petrosino et al., 2012; Sidebottom et al., 2015). Using the data extracted from each study eligible for the qualitative component of the review, we categorise and then synthesise the studies in text and tabular format. We then provide specific subsections aligning to the EMMIE domains of mechanisms, moderators, implementation, and economics. Within each domain subsection, narrative text and tables summarise the number of studies reporting data for that domain, the types research approaches used by included studies (e.g., design and participants), the specific findings for mechanism, moderator, and economic domains, and overarching themes for the implementation barriers and facilitators.

4.4.10. Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We had planned to use subgroup analyses to assess whether the impact of the intervention varied by the following factors: geographical location, target population, nature of the intervention approach (e.g., number of components, specific intervention techniques), and number and type of multiagency partners. However, due to the inability to conduct meta‐analyses using the studies included in the effectiveness component of the review (Objective 1), we were unable to conduct subgroup analyses. For updates of this review, provided sufficient data is found, we will follow the subgroup analysis approach specified in the review protocol (Mazerolle, Cherney et al., 2020).

4.4.11. Sensitivity analysis

We had planned to use sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of risk of bias on estimates of the treatment effect. However, due to the inability to conduct meta‐analyses using the studies included in the effectiveness component of the review (Objective 1), we were unable to conduct these analyses. For updates of this review, provided sufficient data is found, we will follow the sensitivity analysis approach specified in the review protocol (Mazerolle, Cherney et al., 2020).

4.5. Deviations from the protocol

Our review made six deviations from the protocol. First, all studies eligible for the review of effectiveness (Objective 1), and 30% (n = 8) of the studies eligible for the review of mechanisms, moderators, implementation factors and economic considerations (Objective 2) were independently double coded. This equated to at least one double coding for each coder and at least one double coding for each of the EMMIE domains. The remaining 18 studies included under Objective 2 were independently coded, but verified upon synthesis by at least one review author (A. C., E. E., L. H.). This is a deviation from the protocol which stated we would utilise a set of five training documents to determine coding accuracy prior to independent coding of all studies included in the review (Mazerolle, Cherney et al., 2020). The reason for this deviation is because we deemed it more important to ensure that coding was consistent across coders by domain for the EMMIE synthesis and that all coding was consistent for the effectiveness studies.

Second, due to the large number of studies included in Objective 2 and the wide variation in quality or explicit focus on the mechanisms, moderators, implementation and economic components within the documents, we did not harvest the references lists or conduct forward citation searching for these studies.

Third, we used the EMMIE appraisal tool to grade each study eligible for review Objective 2 across the mechanism, moderator, implementation, and economic domains. Studies that met a minimum threshold of 3 on each domain were then coded using the form in Supporting Information Appendix C and synthesised narratively in the results section. Any study that did not meet a threshold of 3 was not assessed for risk of bias and was only lightly coded for basic information about the setting, intervention, participants and EMMIE domains. The rationale for this was that the EMMIE appraisal tool provided a preliminary indicator of the quality and depth of evidence in the study. We considered this approach to be analogous to the protocol for the review (Mazerolle, Cherney et al., 2020) whereby studies would not be included in the synthesis if the answer to the following items on the CASP qualitative appraisal tool were “No” or “Can't tell”: (a) Is the research design appropriate to answer the question?; and (b) Was the sampling strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? (see Higginson, Benier, et al., 2015). However, studies rated <3 on the EMMIE appraisal tool were included in an overall summary table, with broad themes noted in the results section. For a full description of this approach, please refer to the “Data extraction and management approach” section.

Our fourth deviation was not contacting study authors where there was either missing information or “unclear” ratings during the risk of bias assessment. We chose this approach because the additional information would not have changed the overall risk of bias result. However, for updates of the review, we aim to follow the original protocol (Mazerolle, Cherney et al., 2020).

Fifth, we used a more suitable risk of bias assessment tool to appraise four of the five studies included in the effectiveness component of the review (Objective 1), rather than the ROBINS‐I tool. The rationale for this deviation is provided in Section 4.4.3.

Sixth, we had planned to examine whether the effectiveness of eligible interventions varied by the following factors: geographical location, target population, nature of the intervention approach (e.g., number of components, specific intervention techniques), and number and type of multiagency partners. Due to the limited evidence located, we did not conduct this analysis.

5. RESULTS

5.1. Description of studies

5.1.1. Results of the search

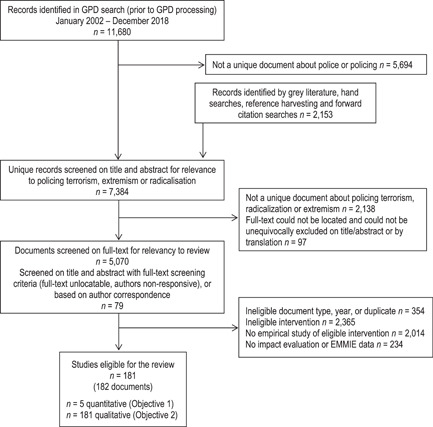

The results of the search and subsequent screening are summarised in Figure 1. The overall GPD systematic search identified 11,680 references published between January 2002 and December 2018 prior to any systematic processing that underpins the GPD (see Supporting Information Appendices B and C). Of these, 5986 references were eligible after title and abstract screening as being potentially about police or policing, and were imported into SysReview to be assessed for eligibility for this review (Higginson & Neville, 2014). The GPD search results were combined with the records identified by the grey literature search, hand searches, reference harvesting, forward citation searching, and consultation with experts (n = 2153) to generate a corpus of 7384 records (after preliminary duplicate removal).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart

A total of 5246 records were eligible after title and abstract screening as being potentially about policing terrorism, radicalisation or extremism. We obtained the full‐text documents for 5070 of these records via institutional libraries or correspondence with document authors, including 145 documents that were written in a language other than English. For documents written in a language other than English, we first assessed the title and abstract of the article using the more specific full‐text screening criteria, as almost all abstracts were written in English. For the remaining documents, we used Google Translate to translate the documents and assess their eligibility. These strategies resulted in the exclusion of 112 documents. For those where translation was not possible or the translation did not permit an unequivocal eligibility decision, we attempted to contact study authors for clarification (n = 33). Three study authors responded and confirmed their study was ineligible for the review. The remaining 30 studies are listed in the “Studies awaiting classification” reference list.

The full‐text documents for 176 records screened as potentially about policing terrorism, extremism or radicalisation could not be located via institutional libraries (including n = 12 written in a language other than English). Of these, just over one third were conference presentations or magazine articles, with the rest of evenly distributed amongst the following categories of document types: journal articles, books or book chapters, reports or working papers (government and technical), and theses. We handled the processing of records with no full‐text document in two stages. First, we screened their titles and abstracts using the more specific full‐text screening criteria. Second, we attempted to contact the authors where we could not unequivocally exclude the record by screening the title and abstract using the full‐text screening criteria. These two strategies resulted in the exclusion of 79 documents. For the remaining 97 records: (a) authors could not provide the document or recall whether it met inclusion criteria; (b) no response was received from document authors or (c) current contact details for document authors could not be found. These documents are reported in the “References to studies awaiting classification” list.

Of the 5149 studies screened on the full‐text screening criteria, five studies met the review eligibility criteria for the review of effectiveness (Objective 1) and 181 studies (reported in 182 documents) met the inclusion criteria for the mechanisms, moderators, implementation and economic component of the review (Objective 2). The five studies eligible for the quantitative analysis were also eligible for Objective 2.

5.1.2. Included studies

Review of quantitative effectiveness studies (Objective 1)

Radicalisation to violence outcome category