1. BACKGROUND

1.1. The problem: Limited evaluation of social and gender equality outcomes of water, sanitation and hygiene interventions

Safely managed water, sanitation and hygiene (WASH) services are viewed as fundamental for human wellbeing, enabling a range of positive outcomes related to health, education, livelihoods, dignity, safety, and gender equality. Progress in providing WASH services and thus achieving these outcomes has not occurred equally, with a range of inequalities in who can access and benefit from WASH services across varying socio‐cultural contexts, geographical areas and socioeconomic settings. For instance, among the 785 million people who lack a basic drinking‐water service, and 2 billion who lack access to basic sanitation services, a greater proportion are poor and living in rural areas (WHO/UNICEF JMP, 2019). Further, unsafely managed water and sanitation disproportionately impacts a number of social groups, including women, girls, and sexual and gender minorities, people with disabilities, people marginalised due to ethnicity, caste, poverty or other factors, and those living in vulnerable situations such as displaced people or people who are experiencing homelessness. As the COVID‐19 pandemic disproportionately affects particular groups of people, it has the potential to exacerbate many of these existing WASH inequalities (Howard et al., 2020).

Gender inequalities related to WASH are particularly large, as women and girls have specific needs related to biological factors, and experience strongly gendered norms surrounding water and sanitation, such as expectations of carrying out water fetching, caregiving and hygiene roles within the household (Caruso et al., 2015). In many countries where women and girls are responsible for water fetching this contributes to a substantial burden of musculoskeletal disease (Geere & Cortobius, 2017). Additionally, women and girls are more negatively impacted by a lack of private and safe sanitation facilities, particularly for menstrual hygiene management which creates sanitation‐related psychosocial stress and may cause urinary tract infections (Das et al., 2015; Torondel et al., 2018). Maternal and child health are also thought to be seriously affected by inadequate WASH—for example, sepsis, one of the biggest causes of neonatal mortality, due to unhygienic practices by mothers and birth attendants(Campbell et al., 2015). Additionally, a lack of a household toilet and the practice of open defecation has been linked to sexual violence (Jadhav et al., 2016). These inequalities extend beyond the household, with women and girls, and socially marginalised groups often under‐represented in decision‐making processes at all levels of WASH governance (Coulter et al., 2019; Shrestha & Clement, 2019). In particular, women have had limited access to skilled and higher‐paid employment in the water sector such as within water utilities (World Bank, 2019). While the WASH sector has frequently focused on women and a binary understanding of gender, sexual, and gender minorities also experience a range of WASH‐related inequalities (Boyce et al., 2018; Neves‐Silva & Martins, 2018; Schmitt et al., 2017).

Besides gender, there is a range of other social inequalities related to WASH. Caste relations have shown to facilitate or create barriers to sanitation interventions, related to cleaning, access to subsidies, latrine design, and purity issues (O'Reilly et al., 2017). People experiencing homelessness often face a denial of their rights to safe water and sanitation (Neves‐Silva & Martins, 2018). For people with disability, WASH services often do not meet specific needs for hygiene and privacy, or eliminate discrimination and abuse (Banks et al., 2019). A multicountry study reported that 23%–80% people with disabilities were unable to fetch water on their own, and those with more severe impairments had problems accessing the sanitation facilities used by other household members (Mactaggart et al., 2018). In many cases gender intersects with other social identifies such as age, sexual orientation, ethnic group, caste, disability, and this may exacerbate disadvantage (or expand advantage) (Crenshaw, 1989). For instance, displaced women and girls face particular challenges in access to safe and private facilities for menstrual hygiene management (Schmitt et al., 2017).

Awareness of these inequalities has resulted in implementation of WASH interventions that include mainstreaming of gender and social equality (GSE) considerations. While a large focus, in terms of both theoretical and empirical work, has been placed on gender inequalities, other forms of social exclusion related to WASH are also being increasingly addressed (WaterAid, 2010). WASH practitioners argue that such interventions will result in services that meet the needs of different groups, as well as challenge unequal power relations in society (Carrard et al., 2013). For example, adequate sanitation and hygiene facilities in schools are widely considered to facilitate girls' school participation and contribute positively to a sense of dignity and self‐esteem (Sommer et al., 2016). Easily accessible water sources are thought to increase economic opportunities and economic empowerment, as people spend less time and energy on unpaid work and have more time for productive or leisure activities. The time‐savings benefits of improved water access have long been recognised as reason alone to investment in improved water supply, even without demonstrable benefits on child survival health (Churchill et al., 1987). For example, Cairncross and Cliff (1987) demonstrated substantial opportunity costs of inadequate water supply for women, which affected time available for child‐care, food preparation, household hygiene, rest, and income generation. Moreover, household sanitation facilities or water on premises are thought to decrease risks of violence associated with open defecation or water collection (Geere et al., 2018; Jadhav et al., 2016). Consideration of gender and power relations within WASH interventions has also been shown to improve women's self‐confidence in intra‐household relations (Leahy et al., 2017), and participation in society, such as community‐level decision‐making (Sam & Todd, 2020).

Despite the wide range of GSE outcomes associated with WASH interventions, evidence has often been anecdotal, based on assumptions, or reported only in the grey literature. Funding agencies, governments, civil society organisations and academia alike have placed a greater emphasis on rigorous evaluation of technical and health outcomes of WASH interventions. This includes measuring provision or uptake of WASH‐related technology or behaviours such as safe water storage, hand‐washing with soap after using a toilet, toilet maintenance and similar (Parvez et al., 2018), or evaluating the relationships between access to inadequate WASH facilities and incidence of diarrhoeal diseases and other infectious diseases (Crocker & Bartram, 2016; Pickering et al., 2019).

Limited efforts to evaluate GSE outcomes may be related to the challenges of measuring social change, often a complex, nonlinear, context‐specific, and slow process (Hillenbrand et al., 2015). It can be difficult to trace clear causal pathways between intervention components and targeted outcomes. For instance, improvements in GSE outcomes may be cross‐sectoral, with difficulties attributing change directly to particular WASH components. Despite these challenges it is important to understand what kind of interventions are most often associated with better or worse GSE outcomes. A lack of attention to monitoring and evaluating changes in GSE outcomes or development of validated methodological approaches for evaluating GSE outcomes (UNESCO, 2019) has translated into gaps in understanding which intervention components contribute to the greatest positive impacts on GSE outcomes, as well as which interventions may lead or contribute to negative impacts that reinforce inequalities. These gaps in understanding are evident in the global policy discourse. For example, Sustainable Development Goal 6 “Clean Water and Sanitation” refers to the sanitation needs of women and girls, but has been described as “gender blind” due to the lack of gender‐sensitive targets (UN WOMEN, 2016). A comprehensive synthesis and greater availability of evidence of GSE outcomes resulting from WASH interventions is therefore needed to support WASH intervention design, implementation, and evaluation.

1.2. The intervention: Understanding gender and social equality in WASH interventions

In this review, we use gender to describe socially constructed identity and the related contextual and variable set of roles, behaviours, norms and responsibilities, while sex refers to a spectrum of biological differences. Although WASH interventions have often applied a female/male binary understanding of gender, there is a diverse spectrum of gender identities and gender expressions, including those who identify across or outside of the gender binary, and this group is described as gender minorities. Gender comprises part of a broader concept of social (in)equality and power hierarchies (Segnestam, 2018). Moreover, gender and other social identities such as age, sexual orientation, ethnic group, citizenship status, socio‐economic status, caste, disability, marital status are interdependent, and may intersect to exacerbate exclusion (Crenshaw, 1989). For instance, there is a particularly large burden on young girls and adolescents for water‐related responsibilities, while boys may be involved in water fetching for productive water uses (Thompson et al., 2011). It is important to note that local interpretations of what is meant by gender equality and other forms of social equality may be contested, adapted, and negotiated, which then influences engagement with the normative global discourse on gender equality. In a particular context, this may influence what components of a WASH intervention targeting GSE outcomes are culturally acceptable or relevant.

In the WASH sector, addressing gender and social equality has often focused on meeting practical needs (Moser, 1989), such as interventions that address people's needs based on gender and other socially constructed roles. This frequently involves instrumental approaches, whereby the focus is on “engaging women” to achieve other ends (e.g., such as engaging women to promote child health or economic development) (MacArthur et al., 2020). Alone these approaches are not viewed as adequate to address inequalities without addressing power issues, the burden of work, or similar (Cornwall, 2016; Hillenbrand et al., 2015). More recently, gender transformative development that addresses unequal power relations, structures and norms is being more widely taken up by actors in the WASH sector (MacArthur et al., 2020; Oxfam, 2020). These approaches focus on power dynamics between different social groups in varied social contexts and seek to address how these relations produce inequalities. For instance, interventions that address these considerations may result in more equal sharing of unpaid domestic and care responsibilities or increased opportunities for marginalised groups to use their voice in decision‐making. A key component of gender transformative approaches in the development sector is women's empowerment, which is understood as a complex process occurring at different levels, spaces and over time (Cornwall, 2016). However, gender transformative approaches aim to go beyond women's empowerment, emphasising working with both women and men to transform social relations towards more equitable arrangements.

To measure and evaluate change, interventions have sometimes been described in terms of their level of responsiveness to gender (and less commonly, social equality) aims. While a range of terms may be used to categorise outcomes (e.g., gender‐sensitive, gender‐responsive, gender integration), they are generally placed along a continuum (Pederson et al., 2014). At one end, interventions are gender‐blind and may exacerbate or exploit inequalities. In the middle, interventions may be inclusive of gender needs to varying extents, such as providing safe water supply or sanitation facilities, but may have a neutral impact on gender and social power relations. At the other end, interventions are aimed at transforming gender and social norms and relations. For instance, WaterAid developed a framework that categorises gender outcomes across the WASH system as ranging from harmful to inclusive, empowering and transformative (WaterAid, 2018). In this review, we use inclusive and transformative gender and social equality outcomes to capture two broadly defined categories of outcomes.

1.3. How the intervention might work

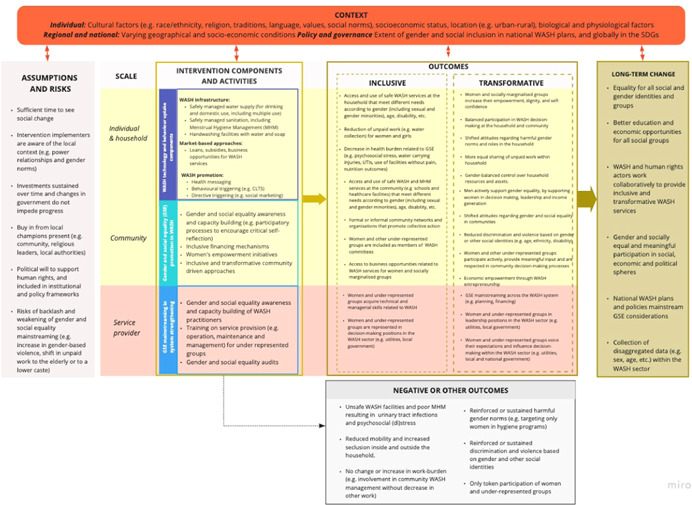

Our theory of change for promoting gender and social equality through WASH interventions is that implementation of various WASH technologies and promotion of behaviours, combined with GSE mainstreaming components, can lead or contribute to better access to services that meet the specific needs of all users (Figure 1). If GSE considerations go beyond meeting the needs of individuals to challenge power relations, WASH interventions will lead to or contribute to transformative changes that reduce inequalities related to WASH challenges and broader society. Together these outcomes will result in or contribute to long term changes in outcomes related to gender and social equality more widely, across different levels of society. These could be increases in the participation of women, girls and marginalised groups in public and economic life, better opportunities for education and livelihoods, and decreased discrimination and violence. At the same time, we acknowledge that these types of changes are complex, slow‐acting and nonlinear. Below, we describe WASH intervention components and resulting GSE outcomes illustrated in our theory of change in more detail.

Figure 1.

A draft theory of change (also available from: https://miro.com/app/board/o9J_ks7q_N8=/). Source: Authors

1.3.1. WASH interventions and their components

Water supply, sanitation or hygiene intervention components are sometimes grouped together (e.g., WASH) due to their inter‐dependent nature, particularly in rural settings. WASH interventions can be described with four main components: “how,” “what,” “where” and “for whom” (Waddington et al., forthcoming). “How” describes how the intervention is delivered, such as behaviour change approaches (e.g., triggering campaigns to end open defecation and similar). “What” describes the targeted WASH technology or practice (e.g., toilet usage, construction of water supply or hand‐washing stations). In the case of water supply, while a focus has been largely on safe drinking water, some interventions may go beyond meeting basic needs for drinking water and hygiene, to serve a range of uses including productive uses (e.g., livestock watering), known as Multiple Use of Water Services. In addition to supply driven approaches, WASH interventions can also involve the use of market‐based approaches to strengthen supply and demand, such as through training of local vendors, or smart subsidies and loans to households to promote uptake of WASH services (USAID, 2018).

“For whom” refers to the targeted participants. Most WASH interventions attempt to improve service provision for households, however interventions may target individuals, entire communities, service providers and authorities at national and subnational levels. Intervention components may be adapated to meet the needs of different groups, such as ensuring menstrual hygiene management in sanitation facilities. WASH interventions may also take place at the service‐provider or regulator level (e.g., local government overseeing service provision and setting up policy and accountability mechanisms) level as part of WASH system strengthening. WASH systems refers to all the social, technical, institutional, environmental and financial elements, actors, relationships and interactions that impact service delivery (Huston & Moriarty, 2018). “Where” describes the targeted location of the intervention such as the household, community (e.g., marketplaces, religious buildings), school or health facilities. Many aspects of WASH service delivery are cross‐sectoral, including housing, education, or health sectors, which can lead to complex arrangements with no clear governance structure. An example is WASH in‐school interventions, which target WASH services in schools to improve health and education outcomes together, which generally involve stakeholders from both WASH and education sectors (Deroo et al., 2015).

WASH interventions are increasingly using GSE mainstreaming components in their designs to ensure that they are inclusive of the needs of all users and contribute to GSE outcomes. Mainstreaming refers to addressing GSE considerations across development, planning, implementation, and evaluation of a WASH intervention (but it may be carried out to varying extents in different types of interventions). GSE mainstreaming is often viewed as having the dual purpose of improving the sustainability and effectiveness of the technical and health outcomes (e.g., such as uptake and sustained use of technologies or specific behaviours), as well as to promote positive change in GSE outcomes. Regardless of whether a WASH intervention includes intentional mainstreaming, it will still have social (and gendered) outcomes. Such an intervention may still lead to positive GSE outcomes, but no change in outcomes or regression with reinforced inequalities is also possible (Taukobong et al., 2016). This indicates the importance of intentional mainstreaming to influence these in the direction of inclusion and equality.

In this review we define WASH interventions as complex interventions because they are comprised of multiple components (show intervention complexity) and have multiple causal pathways and feedback loops (pathway complexity) (see Figure 1). In addition, they also often target multiple participants, groups, and organisational levels (population complexity), require multifaceted implementation strategies to boost adoption and uptake (implementation complexity) and are implemented in multidimensional settings (contextual complexity) (Guise et al., 2017).

1.3.2. GSE outcomes

We define GSE outcomes as inclusive and transformative. Inclusive WASH outcomes are those that relate to the specific WASH needs and barriers of different social groups (Hillenbrand et al., 2015). For instance, these interventions may involve female‐friendly school toilets (e.g., modifications to ensure adequate menstrual hygiene management facilities) to meet girls' menstrual hygiene needs (Schmitt et al., 2018; UNICEF WaterAid & WSUP, 2018), toilets adapted to people with disabilities or toilets that are adapted to religious or cultural practices. Inclusive WASH outcomes may involve provision of water at more convenient locations, such as on premises (e.g., within the household property) to reduce women's time and physical burden spent collecting water, provision of water and sanitation at healthcare facilities to improve maternal outcomes, or provision of sanitation in public spaces such as schools and marketplaces. Beyond infrastructure design, such intervention components may include sharing of information, fair tariff structures, inclusive operating time, etc.

To capture different types of transformative outcomes described in our theory of change we applied Rowland's framework of power (1997) (Table 1). Transformative approaches address social causes of being unable to access and benefit from WASH, and seek to transform harmful power dynamics, norms and relations such as unequal distribution of unpaid work in the household. For example, while provision of a safe water source on premises can reduce the amount of time someone needs to collect water, it does not change their status in the household or community. Any time savings may lead to expectations to conduct other unpaid work. In contrast, men assuming roles traditionally assigned to women may indirectly support women's participation and empowerment in other domains, such as having time to contribute to water governance. Transformative outcomes also relate to women or marginalised group gaining greater control of their lives, for example, obtaining expertise in managing a water source, acquiring land tenure documentation for a water source, or gaining financial autonomy through WASH entrepreneurship.

Table 1.

Types of power with examples of transformative GSE outcomes relevant for WASH sector

| Power types | Description | Transformative GSE outcomes |

|---|---|---|

| Power within | A person's or group's sense of self‐worth, self‐awareness, self‐knowledge, and aspirations, which are also associated with agency and shaped by social norms and gendered relations |

|

| Shifted perceptions towards gender and social equality, for example, men actively support women in decision‐making and leadership | ||

| Power to | Ability to make decisions, act and to realize one's aspirations. It is directly related to the agency dimension of empowerment and is frequently measured in terms of individual skills, capacities |

|

| Engagement of under‐represented groups in design processes and WASH trainings | ||

| Power over | Control over resources (e.g., financial, physical, personal networks and people) |

|

| Power with | Involves collaborative and collective power with others through mutual support |

|

In addition, there may be neutral, negative or other unexpected outcomes resulting from WASH interventions, as shown in Figure 1. In some cases, these may exacerbate inequalities related to WASH. For example, a sanitation intervention may lead to increased exposure to violence and discrimination if facilities are constructed without considering the needs of women and vulnerable groups, lead to backlash related to challenging social norms, or increase the burden of unpaid work (e.g., refilling handwashing stations). Other unintended harmful effects may include unpaid domestic labour shifted to the elderly or to a lower caste. Even when implementers consult with community leaders about socially acceptable ways of working with the community, WASH interventions may lead to increased resistance towards gender equality both at the household (e.g., (re)distribution of work) and community level (e.g., decision making in WASH governance).

1.3.3. Context, assumptions and risks

The process of social change is complex, nonlinear, and it can take a long time to observe change. These processes are highly contextual and dependent on social, gender, cultural, economic, ecological and institutional factors at individual, household, community, and institutional spheres (Carrard et al., 2013). Thus, no intervention leads to positive GSE outcomes in all contexts and outcomes. The outcomes of WASH interventions are also dependent on a set of assumptions, such as continuing investments and political will to support the kind of WASH interventions that lead to GSE outcomes. For instance, in some settings discriminatory policies or laws may be put in place which hinder progress, despite a well‐designed intervention (especially at the level of service provision). There are also risks associated with addressing GSE due to possible backlash. For example, WASH interventions targeting increased decision‐making opportunities in one setting, or reduction of gender‐based violence, may lead to increase in another setting, or to women having less agency regarding their mobility both in and outside the household. There may also be unintended consequences of WASH technology provision as a result of interactions with social norms. For example, Rogers (2005) documented in Egypt that improved village water supplies were viewed suspiciously by villagers, who thought the taste of chlorine in the water was part of a government sterilisation programme. In addition, women preferred to collect surface water from canals where they could socialise with other women.

Finally, each of the outcomes includes an intermediate step to reaching that outcome (such as capacity building for improving employment opportunities or similar) but this could not be represented in Figure 1.

1.4. Why it is important to do this review

There is a growing interest in transformative WASH interventions because of their potential for delivering impact (Oxfam, 2020; WaterAid, 2018). A key message from the UN WOMEN Expert Group Meeting on Gender Equality and Water, Sanitation and Hygiene was as follows: “Taps and toilets are not enough. To realize transformational WASH outcomes, governments must enable women's voice, choice and agency” (UN WOMEN, 2017). In parallel, there is a growing emphasis on developing tools for collecting data on gender outcomes and disaggregating data by sex, age, ability status and other factors (Miletto et al., 2019).

Despite the interest in these outcomes, evaluation practice in the WASH sector has placed more focus on technical and health outcomes, such as technical standards for water sources, or evaluating diarrhoea prevalence, leaving gaps relating to evaluating gender and social equality outcomes (Loevinsohn et al., 2015; Mackinnon et al., 2019). This gap can translate into a lack of budget line items and prioritisation by stakeholders.

Most existing reviews on WASH have no explicit focus on gender, education or other social outcomes. Some reviews account for gender only as a contextual factor in the WASH intervention design (De Buck et al., 2017) or adoption (Hulland et al., 2015). The past and ongoing reviews that explicitly focus on social outcomes have a relatively narrow scope (only one WASH component such as menstrual hygiene management) or one specific group (e.g., girls in schools)) and some of them were conducted more than seven years ago (Birdthistle et al., 2011; DFID, 2013; Hennegan & Montgomery, 2016; Hennegan et al., 2019; Jasper et al., 2012; Munro et al., 2020; Sumpter & Torondel, 2013).

An evidence‐and‐gap map (EGM) (Waddington et al., 2018) compiled systematic reviews and impact assessments and mapped outcomes such as psycho‐social health, education, labour market outcomes, safety and income, consumption or poverty (see https://gapmaps.3ieimpact.org/evidence-maps/water-sanitation-and-hygiene-wash-evidence-gap-map-2018-update). The EGM did not include primary study evidence that used methods other than quantitative approaches, or undertake synthesis of findings from included impact evaluations. The impact studies included in the EGM, will be assessed for eligibility in the current review.

Thus, this review will provide a much‐needed synthesis of effectiveness of complex WASH interventions in contributing to GSE outcomes, facilitating better conceptualisation of GSE and WASH links as well as contributing to development of measurement tools to more accurately evaluate the GSE outcomes. The development of different measurement tools is already happening (e.g., Empowerment in WASH Index [EWI]: https://www.sei.org/projects-and-tools/projects/ewi-empowerment-in-wash-index/); or WASH Gender Equality Measure (WASH‐GEM): https://waterforwomen.uts.edu.au/wash-gem-piloting-in-cambodia-and-nepal/) and the review can directly inform this ongoing work.

2. OBJECTIVES

This review aims to comprehensively and transparently synthesise evidence on gender and social equality outcomes in complex WASH interventions. We also aim to develop and test a set of hypotheses about causal relationships between WASH intervention components and outcomes and related to our theory of change. Our aim is to advance evaluation practices in the WASH sector by providing methodological advice on how to include, assess and measure GSE outcomes. Additionally, we will map definitions of different outcome measures and provide guidelines on this. The findings will be of use for decision makers in policy and practice allowing them to more effectively design and implement gender and social equality mainstreaming in WASH interventions and strategies and learn from best practices. By describing methodological deficiencies in relevant primary research (see section Assessment of risk of bias in included studies), we will provide guidance and best practice examples for future primary research on the subject.

The review questions are:

Review question 1: What are the impacts of complex WASH interventions on gender and social equality outcomes in low‐ and middle‐income countries?

Review question 2: What are barriers to or enablers of change in these outcomes?

Review question 3: Under which conditions do WASH intervention (components) lead to a change in GSE outcomes?

Review question 4: How are GSE outcomes measured in the literature?

3. METHODS

This review follows Campbell Collaboration policies and guidelines (The Campbell Collaboration, 2019).

3.1. Stakeholder engagement

Principles of stakeholder engagement and co‐design will be applied used throughout the review process to improve the rigour of research, maximise acceptance and legitimacy, provide a strong science‐policy link (Land et al., 2017) and facilitate communication of findings (Haddaway & Crowe, 2018).

We comprehensively mapped stakeholders that work in the WASH implementation and policy space, and closely linked stakeholders working on gender and social equality more broadly. A suite of complementary processes was used to identify and map stakeholders (e.g., snowballing and systematic searching). The resulting stakeholder map will also be used for the communication of review findings. Identified key stakeholders, such as representatives of funding agencies and civil society organisations engaged in WASH interventions, and researchers with expertise on a range of WASH outcomes, were engaged in the codesign of the systematic review protocol, review scope and questions, definitions and a theory of change to model the link between intervention components, the context and GSE outcomes (see Figure 1). The engagement occurred via two online workshops in May and June 2020. In addition and to obtain input of wider community, we invited stakeholders to comment on a previous version of the review protocol that was publicly available on the website of Stockholm Environment Institute and shared via Sustainable Sanitation Alliance network (https://www.susana.org), the Rural Water Supply Network and other online communities of WASH practitioners between 16 July and 3 August 2020. Stakeholders' inputs on the protocol and our responses are available here: https://www.sei.org/projects-and-tools/projects/advancing-evaluation-of-gender-equality-outcomes-in-wash/.

3.2. Criteria for considering studies for this review

Below we describe the eligibility criteria. For all the review questions we will apply the same eligibility criteria (except for Types of studies, see below for details).

3.2.1. Types of studies

In order to answer review question 1, we will consider quantitative research with experimental designs (with random assignment), quasi‐experimental designs and natural experiments, which are able to address confounding:

Randomised controlled trials, with assignment to intervention or “encouragement” to intervention at individual or cluster level.

Quasi‐experimental designs with nonrandom assignment, using methods such as naïve and statistical matching on baseline data, and double‐difference analysis of data pre‐ and posttest data.

Natural experiments using methods such as regression discontinuity design to construct comparison groups, where assignment is determined at pretest by a cut‐off on an ordinal or continuous variable (White & Sabarwal, 2014)).

Pipe‐line designs, where individuals or groups are followed over time and compared to comparisons who are eligible for intervention at a later date.

In addition, pre‐post studies will be included in the particular case of immediate outcomes such as time‐use or time‐savings, for which the expected effect is large and confounding is unlikely (Victora et al., 2004).

Mixed‐method study designs will be considered that examine results along the causal pathway, reporting intermediate and endpoint outcomes.

In order to answer research question 2, all qualitative and mixed‐method study designs will be considered, regardless of whether the study design includes an explicit comparator (whether from a separate group or a pretest). All eligible studies included under research questions 1 and 2 will be eligible to answer research question 3 and 4. No commentary papers, theoretical or modelling studies will be included. We will include studies regardless of their publication status and their electronic availability.

3.2.2. Types of participants

All types of study participants (from different gender and social identities, age groups and across rural and urban settings) will be included but restricted to those in low‐ and middle‐income countries (LMICs). We will use the LMIC definition provided by the World Bank including low‐, lower‐middle and upper‐middle income economies from their classification for year 2021 (see https://datahelpdesk.worldbank.org/knowledgebase/articles/906519-world-bank-country-and-lending-groups).

3.2.3. Types of interventions

All types of interventions providing water, sanitation and hygiene software and hardware technologies implemented in both rural and urban settings are eligible for the review. Following Waddington et al. (2018), these include direct hardware provision, behavioural change communication (such as health messaging, psychosocial “triggering”), market‐based approaches (such as subsidies for WASH consumers and microloans or training for producers), GSE promotion in WASH, GSE mainstreaming in system strengthening, systems‐based approaches (such as programmes to empower women in WASH decision making and governance, privatisation or nationalisation of water supply and sewage systems, or decentralised provision, e.g., community‐driven development) and a combination of two or more components are relevant for this review.

WASH interventions may also take place at the service‐provider or regulator (e.g., local government overseeing service provision and setting up policy and accountability mechanisms) level as part of WASH system strengthening. Interventions focusing on irrigation or water resources management are beyond the scope of the review.

3.2.4. Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Any types of GSE outcomes resulting from WASH intervention(s) will be included and categorised into inclusive and transformative outcomes as described above in the Theory of Change. This includes, for example, level of or change in empowerment, such as self‐efficacy, voice, participation, agency and decision‐making related to WASH or more generally (e.g., participation in community‐based decision‐making on WASH or more generally), gender‐based violence, discrimination, injury (e.g., pedestrian traffic injury), attack by wild animals, mental health and other psychosocial outcomes (e.g., self‐esteem), time‐use, work burden, access to jobs, access to leisure and sleep, ownership and control of assets, and changes in behaviour such as increased use of WASH facilities among different groups. Additionally, we will record any adverse and unintended effects of WASH interventions that exacerbate inequalities or negatively affect GSE. If reported, evidence of lack of change will also be recorded. We will exclude outcomes relating to infectious disease and poor water quality, such as diarrhoea and stunting, which are covered extensively in other reviews, but will include health outcomes related to GSE and arising from gender roles and social norms such as musculoskeletal injuries and reduced nutritional status from water carrying, infections from poor menstrual hygiene management and psychosocial stress from poor sanitation facilities. We will include any type of measures of eligible outcomes.

Secondary outcomes

We will record any type of intermediate outcomes, thatis, outcomes that are precursors of (or a necessary condition for) empowerment or other gender and social equality outcomes such as change in level of knowledge, capacity and/or awareness. Studies that include only secondary outcomes will be considered eligible and evidence from these studies will inform theory of change development (see Section 3.4.11).

Duration of follow‐up

All durations of follow‐up are eligible for inclusion, including multiple durations of follow‐up in any single study.

Time frame

Due to the wide‐ranging and comprehensive scope of the review, we will include publications from January 2010 to September 2020 to ensure feasibility. Publications prior to 2010 will be excluded.

Types of settings

We will include WASH interventions implemented in both rural and urban settings including households, schools, health facilities, community spaces or workplace settings, and restricted to LMICs.

Eligible languages

We will include studies in English, Spanish and French (as per skillset of the review team).

3.3. Search methods for identification of studies

We will use a multipronged search strategy. All the searches, as justified above, will be done for literature published after 2010.

3.3.1. Electronic searches

Bibliographic databases

We will search for literature in English in several bibliographic databases and platforms (using subscriptions of Stockholm University and University of Sussex) including:

-

1.

Web of Science Core Collections

-

2.

PubMed

-

3.

Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)

-

4.

WHO Global Health Library

-

5.

Econlit

-

6.

Electronic Theses Online Service (ETHOS)

-

7.

Digital Access to Research Theses (DART)

-

8.

ProQuest: Dissertations and Theses

-

9.

Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (NDLTD)

-

10.

The Trials Register of Promoting Health Interventions (TRoPHI)

-

11.

APA PsycINFO

-

12.

APA PsycArticles

-

13.

Sociological abstracts

-

14.

OpenGrey

-

15.

Education Resource Information Center (ERIC)

-

16.

International Initiative for Impact Evaluation (3ie)

In the final report we will detail for each search source which interface was used, and which search settings were applied. Examples of search strategies for selected sources can be found in the Supporting Information.

Table 2 shows two search substrings with terms related to WASH interventions and GSE outcomes (shown as formatted for Web of Science and to be adapted for other search sources depending on their search facilities). The full search string combines the two substrings with Boolean operator “AND.” Search terms were compiled with stakeholders' input.

Table 2.

Search string

| Substring 1: WASH‐related terms | Substring 2: GSE‐related terms | |

|---|---|---|

| toilet* OR latrine* OR watsan OR sanita* OR sewage OR sewerage OR wastewater* OR "waste water" OR (water NEAR/2 suppl*) OR (water NEAR/2 access) OR "water management" OR (water NEAR/2 drinking) OR (water NEAR/2 scarcity) OR handwash* OR "hand wash*" OR soap$ OR "WASH intervention*" OR "piped water" OR "tippy tap*" OR (water NEAR/2 point) OR (water NEAR/2 service) OR (water NEAR/2 security) OR (water NEAR/2 insecurity) OR "open defecat*" OR (hygiene NEAR/2 promo*) OR "water filter" OR "water pump*" OR "menstrual poverty" OR "period poverty" OR handpump* OR "hand pump*" OR (water NEAR/2 collection) OR "water committee*" OR "water well*" | AND | gender* OR discrimination* OR *equalit* OR *equit* OR inclusive OR "sexual minorit*" OR transgender OR femin* OR masculin* OR menstr* OR menses OR UTI OR "urinary tract infection" OR uro$genital OR pain OR *empower* OR school* OR educat* OR violen* OR psychosocial OR "psycho‐social" OR "psycho social" OR "psychological *stress" OR "mental health" OR dignity OR fear* OR taboo* OR elder* OR disabilit* OR caste OR "social class*" OR daughter* OR girl* OR boy$ OR child* OR prestig* OR sham* OR stigma OR privacy OR voice* OR well$being* OR povert* OR "unpaid labor" OR "unpaid labour" OR livelihood* OR income OR fetch* OR esteem* OR "social capital" OR "land tenure" OR leadership OR time$saving OR "transactional sex" OR musco$skeletal OR musculoskeletal OR wife OR wives OR husband$ OR "decision‐making" OR "decision making" |

Note: This search yielded 27500 results in Web of Science Core Collections for Topic search (including search on title, abstract and keywords) with a subscription of the University of Stockholm. The search was performed on 16 October 2020 for literature published between 2010 and 2020, and filtered to English, Spanish and French languages only.

3.3.2. Searching other resources

Specialist websites

Searches will be performed across a suite of relevant organisational websites (see Table 3). The list of the relevant websites is compiled with inputs from stakeholders. These searches will be particularly important for capturing grey literature. Websites that contain information available in bibliographic databases will not be searched. Each website will be hand‐searched for relevant publications.

Table 3.

Specialist websites with details of search languages

| Organisation | Website | Search language | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | African Development Bank's Africa Water Facility | https://www.afdb.org/en/topics-and-sectors/initiatives-partnerships/african-water-facility | English, French |

| 2 | The United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) | https://www.unicef.org/ | English, Spanish, French |

| 3 | The United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) | https://www.undp.org/ | English, Spanish, French |

| 4 | UN Women | https://www.unwomen.org/en/digital-library/publications | English, Spanish, French |

| 5 | The United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) | https://www.unfpa.org/ | English, Spanish, French |

| 6 | The United Nations Human Rights (OHCHR) | https://www.ohchr.org/EN/Issues/WaterAndSanitation/SRWater/Pages/AnnualReports.aspx | English, Spanish, French |

| 7 | The Deutsche Gesellschaft für Internationale Zusammenarbeit GmbH (GIZ) | https://www.giz.de/en/html/index.html | English |

| 8 | The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) | https://www.usaid.gov/developer/development-experience-clearinghouse-dec-api | English |

| 9 | WaterAid | https://washmatters.wateraid.org/ | English |

| 10 | Oxfam International | https://policy-practice.oxfam.org.uk/ | English, Spanish, French |

| 11 | Oversees Development Institute (ODI) | https://www.odi.org/ | English |

| 12 | The World Bank (WB) | https://www.worldbank.org/ | English |

| 13 | The Department for International Development (DFID) | https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/department-for-international-development | English |

| 14 | The Swedish International Development Cooperation Agency (Sida) | https://www.sida.se/English/ | English |

| 15 | CAF—Development Bank of Latin America | https://www.caf.com/en/ | Spanish |

| 16 | Inter‐American Development Bank (IADB) | https://www.iadb.org/es/sectores/iniciativas-agua | English, Spanish |

| 17 | Care | https://insights.careinternational.org.uk/ | English |

| 18 | Femme International | www.femmeinternational.org | English |

| 19 | SNV | https://snv.org/sector/water-sanitation-hygiene | English |

| 20 | Menstrual Hygiene Day | https://menstrualhygieneday.org/resources-on-mhm/resources-mhm/ | English |

| 21 | PATH | https://www.path.org/ | English |

| 22 | International Disability Alliance | http://www.internationaldisabilityalliance.org/ | English |

| 23 | Programme Solidarité Eau | https://www.pseau.org/fr | French |

| 24 | Sustainable Sanitation Aliance (SuSanA) | https://www.susana.org/ | English |

| 25 | SuSanA Latin American chapter | https://www.susana.org/en/knowledge-hub/regional-chapters/latinoamerica-chapter | Spanish |

| 26 | Action contre la Faim | https://www.actioncontrelafaim.org | French |

| 27 | Sanitation Learning Hub | https://sanitationlearninghub.org/ | English |

| 28 | Water for Women | https://www.waterforwomenfund.org/en/index.aspx | English |

| 29 | WaterAid: Inclusive WASH | https://www.inclusivewash.org.au/ | English |

| 30 | iDE | www.ideglobal.org | English |

| 31 | SIMAVI | https://simavi.org/ | English |

| 32 | Plan International | https://plan-international.org/ | English |

| 33 | Water and Sanitation for the Urban Poor (WSUP) | https://www.wsup.com/ | English |

| 34 | International Water Association (IWA) | https://iwa-network.org/ | English |

| 35 | Multiple Use of Water Services | https://www.musgroup.net/ | English |

| 36 | PSI | https://www.psi.org/practice-area/wash/ | English |

| 37 | IRC | https://www.ircwash.org/ | English |

| 38 | ONGAWA Ingeniería para el Desarrollo Humano | https://ongawa.org/ | Spanish |

| 39 | The Water Supply and Sanitation Collaborative Council (WSSCC) | https://www.wsscc.org/ | English |

| 40 | Sanitation and Water for All (SWA) | https://sanitationandwaterforall.org/ | English |

| 41 | Enterprise in WASH | http://enterpriseinwash.info/research-outputs/ | English |

| 42 | BRAC | http://www.brac.net/wash | English |

| 43 | World vision | https://www.worldvision.org/ | English |

| 44 | Organisation for Economic Co‐operation and Development (OECD) | https://www.oecd.org/water/ | English |

| 45 | FESAN, Federacion Nacional de Cooperativas de Servicios Sanitarios Rurales Chile Ltda | http://fesan.coop/ | English, Spanish |

| 46 | Engineering for change | www.engineeringforchange.org | English |

| 47 | European Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid Operations (ECHO) | https://ec.europa.eu/echo/who/accountability/annual-reports_en | English |

| 48 | Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DFAT) | https://www.dfat.gov.au/ | English |

| 49 | Office of US Foreign Disaster Assistance (OFDA) | https://www.usaid.gov/who-we-are/organization/bureaus/bureau-democracy-conflict-and-humanitarian-assistance/office-us | English |

| 50 | Global Waters | www.globalwaters.org | English |

| 51 | EcoSanRes | http://www.ecosanres.org/publications.htm | English |

| 52 | Sanitation Updates blog | https://sanitationupdates.blog/ | English |

| 53 | Water Currents | https://www.globalwaters.org/resources/water-currents | English |

| 54 | United Nations Evaluation Group (UNEG) | http://www.uneval.org/evaluation/reports | English |

Additionally, bibliographies of relevant reviews identified during searching will be checked for relevant literature. We will ask stakeholders (including researchers) to provide relevant literature, including data from unpublished or ongoing relevant research.

Search engines

Searches will be performed in English, Spanish and French in Google Scholar, with simplified sets of search strings, combining both WASH and GSE terms. The first 1000 search results (Haddaway et al., 2015) will be extracted as citations using Publish or Perish software (Harzing, 2007) and introduced into the duplication removal and screening workflow alongside records from bibliographic databases.

Additional sources

Additional searches for eligible literature will be done in reference lists of eligible studies (included at full text) and bibliographies of relevant reviews (including evidence gap maps). We will also draw on the studies published in the WASH evidence and gap map (Waddington et al., forthcoming; Waddington et al., 2018). Furthermore, we will contact relevant experts and organisations for relevant research, unpublished or ongoing studies.

Testing comprehensiveness of the search

A list of 32 articles of known relevance to the review (a benchmark list) was screened against search results to examine whether the search strategy was able to locate relevant records (a benchmark list can be found in the Supporting Information). In cases where these articles were not found during the scoping exercise, search terms were examined to identify the reasons why relevant records were missed, and search terms were modified accordingly and until all the records from the benchmark list were picked up by the string. The final version of the search string picked all the articles from the list.

Assembling library of search results

Results of the searches in bibliographic databases and Google Scholar will be combined, and duplicates removed prior to screening. A library of search results will be assembled in a review management software EPPI reviewer (Thomas et al., 2020).

3.4. Data collection and analysis

3.4.1. Description of methods used in primary research

We anticipate that our evidence base will include quantitative, qualitative and mixed method research, including impact assessments and other types of project evaluations. A number of studies have collected data on time‐use (usually due to improved water supplies) and we will use it to exemplify a variety of potential methods used in primary research to study this outcome. Devoto et al. (2012) collected time‐use survey data in the context of a randomised encouragement trial in Morocco. Klasen et al. (2011) analysed time‐use available in household survey data in Yemen using fixed effects estimation. Dickinson et al. (2015) measured time use due to improved sanitation in a cluster‐randomised control trial. Arku (2010) conducted a retrospective mixed‐methods before‐after study in Ghana of improved water supply, which collected reported average time‐savings from improved water, relative to recalled baseline information. The study also collected qualitative evidence on barriers to accessing water through focus group discussion and key informant interviews.

3.4.2. Criteria for determination of independent findings

Multiple intervention groups will be carefully assessed to avoid double counting and/or omissions of relevant groups. Dependency of findings will be assessed at the data, publication and within publication levels. Sources of dependency at data level include publications by different authors using the same data. We will endeavour to group any studies based on the same dataset under a single study. Similarly, we will group multiple publications of the same analysis (e.g., working paper versus journal article) under a single study. Dependency at the within‐publication level, for example reporting of multiple effect estimates by follow‐up period, or reporting of multiple outcomes, will be addressed by not including multiple findings in any single analysis, so as to not weight the dependent findings more heavily in comparison with studies reporting only single findings. Thus, for example, where multiple follow‐ups are reported, cross‐study meta‐analysis will include a “synthetic effect” calculated as the sample‐weighted average across follow‐ups (Waddington & Snilstveit, 2009). However, within‐study analysis may still draw on the multiple follow‐ups using time‐series analysis. Alternatively, and in cases where there are sufficient data, we will use multilevel meta‐analysis. Where multiple outcomes are reported, for example overall time‐savings, and time‐use for reproductive health, production and leisure, the outcomes will be analysed separately.

3.4.3. Selection of studies

Screening will be conducted at two levels: at the title and abstract level together, and at full‐text level in EPPI reviewer. Retrieved full texts of potentially relevant records will then be screened at full text, with each record being assessed by one experienced reviewer. As we expect, based on the scoping exercise, the search to yield a large number of records (>40,000), double screening will not be possible due to lack of resources. Nevertheless, we will make the process of screening more efficient through the innovative use of machine learning and other automation technologies in EPPI‐Reviewer. Specifically, a combination of machine learning assisted screening function (“priority screening,” that uses a machine learning algorithm to “learn” the scope of the review as records are manually screened) and modelling (bespoke machine learning classifiers) will be used to support and facilitate manual title and abstract screening and help devise empirically informed cut off point below which no manual screening will be done. A training set would be prepared from the records that were screened by at least two reviewers Machine learning functionality in EPPI Reviewer is a technology in development, but it showed good in performance in screening prioritisation (Tsou et al., 2020).

To assure consistency among all reviewers, consistency checking will be performed on a subset of records at the beginning of each screening stage. A subset of 600 title and abstract records and 120 full texts will be independently screened by all reviewers. The results of the consistency checking will then be compared between reviewers and all disagreements will be discussed in detail. Where the level of agreement is low (below c. 80% agreement), further consistency checking will be performed on an additional set of records and then discussed. Following consistency checking (i.e., when the agreement is above 80%), records will be screened by one experienced reviewer.

3.4.4. Data extraction and management

We will extract data and meta‐data following theory of change components, including bibliographic information; study aims and design including location, data collection method, sample size, analytic approach; critical appraisal, details about intervention and implementation context; population details (including age, identity group(s), intersectionality and other types of moderators); outcomes and study findings (the outcome means and measures of variation in case of quantitative research, or first and second order constructs in case of qualitative research). This list will be expanded during the review process (and as part of framework synthesis, see Section 3.4.11). A draft coding scheme can be found in the Supporting Information.

We will make maximal use of data and where quantitative data are not reported in the form suitable for meta‐analysis (e.g., as means and standard deviations), we will perform necessary data conversions and calculate desired metrics (e.g., SEs can be computed from confidence intervals, t statistics, and p values).

Prior to starting with coding and data extraction, and to assure repeatability of data extraction and coding process, consistency checking exercise will be performed on a subset of records (up to 10%) independently extracted by all reviewers. All disagreements will be discussed among reviewers, and coding scheme will be clarified if needed. The data extraction will be then performed by a single reviewer. In a scenario where only a small number of studies is included for data extraction (≤20), dual data extraction (i.e., by two reviewers independently) will be performed. Discrepancies in data extraction between the reviewers will be resolved through a discussion.

3.4.5. Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Eligible studies will be subject to critical appraisal, where existing and validated tools will be used. For assessing risk of bias in quantitative randomised and nonrandomised studies we will use a tool (Waddington, forthcoming) that has been developed for WASH sector impacts evaluations, drawing on and extending Cochrane's approaches for individual randomised studies (Higgins et al., 2016), cluster‐randomised studies (Eldridge et al., 2016) and nonrandomised studies (Sterne et al., 2016). Overall, the assessment of quantitative studies will include an assessment of external and internal validity including confounding, selection bias, missing data, deviations from intended intervention, measurement error, bias in reporting, and sampling bias.

For qualitative studies we will follow Noyes et al. (2019) guidance focusing on the quality in the research, assessing methodological strengths and limitations (such as clarity of aims and research questions, congruence between research aims and design, the rigour of case/participant identification, sampling and data collection to address the question, appropriates of method application, the richness of findings, exploration of deviant cases and reflexivity of researches) (and more here: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook/current/chapter-21#section-21-8).

As a result of the critical appraisal process, we might categorise relevant studies as, for example, having a high and low validity. This information will be used in a sensitivity analysis during the synthesis stage of the review. Studies with unacceptably low validity may be excluded from the review. The cut off points for each of the categories will be decided during the appraisal process and based on the overall state of the evidence (this will be described in detail in the review report). Studies will not be excluded on the basis of reporting of the outcome data to avoid selective outcome reporting bias.

Prior to starting with this stage, to test the appraisal tools and assure repeatability of the appraisal process, consistency checking will be performed on a subset of records (up to 10%) with different study designs independently assessed by all reviewers. All disagreements will be discussed among the team, and assessment criteria will be clarified if needed. All the studies will be appraised by at least two reviewers.

3.4.6. Measures of treatment effect

Given that we expect differences (in scale and type of data) in outcome reporting, to compare results of continuous measures we may use the standardised mean difference (SMD), and the odds ratio (OR) for binary measures.

3.4.7. Unit of analysis issues

Each article and each study will have uniqe IDs. In case of multi‐arm studies, only intervention and control groups that meet eligibility criteria will be included and related relevant outcome data will be extracted.

3.4.8. Dealing with missing data

Authors of the original studies will be contacted for missing information (if correspondence details are valid and available). Where information is not available, such as on pooled standard deviations, appropriate methods will be used to derive effect sizes from reported information such as t statistics (Borenstein et al., 2009).

3.4.9. Assessment of heterogeneity

For quantitative data (and in case of sufficient number of studies with sufficiently large sample sizes), forest plots will be inspected visually to see the overlap in the confidence intervals for outcome data. I 2 statistic will be calculated to quantify relative heterogeneity across studies (recognising that this statistic produces uncertain assessment of heterogeneity in cases where a number of studies is low (von Hippel, 2015). τ 2 will be calculated as a measure of absolute heterogeneity.

3.4.10. Assessment of reporting biases

To assess risk of reporting bias, the (contour enhanced) funnel plots will be inspected visually, and Egger's test or an appropriate alternative for binary data) will be performed on quantitative data.

To minimise the risk of reporting bias we are conducting extensive searches for both academic and grey literature.

3.4.11. Data synthesis

We will conduct a mixed methods evidence synthesis with a sequential design (Heyvaert et al., 2017) where a theory built in the first stage, will be “tested” in the second stage. For each of the synthesis stages we will use different approaches as detailed below.

First, we will use framework synthesis (of mixed‐method and qualitative research studies) to (1) improve initial theory of change (Figure 1) with new understandings about the links between intervention, their components and outcomes (Kneale et al., 2018), and (2) identify barriers and enablers. Analysis of effect sizes (or meta‐analysis)‐will be used to answer Review Question 1. Meta‐analysis will be done to present forest plots of effect sizes with 95 percent confidence intervals by outcome, using Stata software. Finally, we will use Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and/or meta‐regression to explore heterogeneity and test hypothesis from the theory of change to answer Review Question 3 (see next section).

Framework synthesis (Brunton et al., 2015, 2020; Macura et al., 2019) is a method for organising and synthesising diverse types of evidence as it can accommodate qualitative and mixed method studies. It can be used for studying complex interventions, while supplying (different types of) evidence across longer causal chains (Kneale et al., 2018). Framework synthesis is composed of six analytical stages including (1) familiarisation with the data; (2) framework creation or selection; (3) indexing of data according to a framework; (4) charting or rearranging the data according to the framework and potentially framework modification; (5) mapping and (6) interpretation. The familiarisation and framework selection stages were completed during the protocol drafting process as reviewers got familiar with the topic under study and drafted (along with the stakeholder input) theory of change (see Figure 1). In the next step and at the indexing stage, the review team will perform searches, screening, data extraction (informed by the draft theory of change and as described in the previous sections of this protocol) and identify main characteristics of relevant studies. In the charting stage, characterised studies will be further grouped into categories and themes will be derived from the data. At the mapping stage derived themes will be considered in the light of the original research question and we will investigate how derived themes relate to each other and to the theory of change that can be expanded with new themes at this stage. Based on the number of studies included at this stage, we will be able to decide the next synthesis step (see below). The studies will not be categorised and selected for the next stage on the basis of their results, however. At the interpretation stage derived themes will be considered in the light of the wider research literature.

In a scenario where two or more studies report similar types of quantitative outcomes, we will perform a meta‐analysis, where pooled effect sizes will be estimated using random effects and weighted appropriately to summarise the impact of the intervention. Where there are not more than a single study providing evidence for a particular outcome, we will present effect sizes in forest plots. In one meta‐analysis we will combine and compare GSE outcomes of the same type of WASH intervention (components) (e.g., outcomes of WASH infrastructure provision will not be compared with health messaging interventions).

We will test links from the (now expanded) theory of change and explore heterogeneity among studies using Qualitative Comparative Analysis (QCA) and/or meta‐regression. This step can increase the robustness of the claims made in the theory of change. QCA is a method for identifying (necessary and sufficient) relationships in data. In a review setting, QCA can identify or test links between participants, intervention (components) and context that may be associated with or trigger a successful outcome (Kahwati et al., 2016). QCA is valuable as it can examine complexity within small datasets where number of studies or examples of a phenomenon is small, but number of variables that might explain a given outcome or differences in study findings is large (Kneale et al., 2018; Thomas et al., 2014). The unit of analysis is not an individual study but a set or a configuration of intervention (components), participants and contextual characteristics that together lead (or not) to the outcome of interest. These configurations or combination of different factors are called conditions in QCA (James Thomas et al., 2014). QCA includes six stages: (1) building the data table describing set of conditions and outcomes for each study; (2) constructing a truth table and assigning studies with same configurations of conditions to sets; (3) resolving contradictory configurations where sets of studies with identical configurations of conditions lead to different outcomes; (4) Boolean minimisation to analyse the truth table, finding solutions which encompass as many studies as possible; (5) consideration of the “logical remainders cases” or configurations without any cases; and (6) interpretation of the solution in the light of studies included in the solution, the review questions and theory of change that guided the review (Thomas et al., 2014). The conditions will be identified in the primary studies and during indexing and mapping stage of the framework synthesis. Conditions could be factors that may act as a barrier or a facilitator (sometimes both at the same time and depending on context). Any identified condition thus can be reformulated into a hypothesis that can be tested via QCA. For example, a condition for equality could be that men's support increases women's engagement in WASH‐related decision making. A hypothesis to be tested is in this case is: Does men's support (=condition) increase the likelihood that women are invited into decision boards (=outcome)? Through QCA we could then obtain following answers: yes, no, or depending on a specific context.

Similarly, and in a scenario where enough studies report similar types of quantitative outcomes, meta‐regression could be performed as well to explore the heterogeneity and test hypotheses from the theory of change. The moderators for this analysis will be sourced from the theory of change (amended at the previous synthesis step). We will describe in which cases we will choose QCA over meta‐regression in detail in the review report.

3.4.12. Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis will be performed during the synthesis stage to understand if results of the synthesis depend on the methodological rigour and susceptibility to bias of included studies. If there are sufficient data, we will run separate meta‐analyses for randomised controlled trials and quasi‐experimental studies. These two types of studies can be later combined in one meta‐analysis and results of these two analyses will be compared.

The final report will include a refined theory of change and a description of how intervention components contribute to or result in a change in specific GSE outcomes, an overview of different barriers and enablers to a change in outcomes and ways to measure these outcomes, an assessment of possible knowledge gaps and clusters (produced by cross‐tabulating extracted data from key variables (e.g., type of outcome by type of intervention(component)) and corroborating these findings with stakeholders) that may constitute priority topics for primary research, and a discussion of tentative policy implications of the review findings.

3.4.13. Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity will be analysed using subgroup analysis, whereby gender and social equality outcomes for different population groups (such as women and men or rural, per‐urban and urban populations and similar) are reported. The study will also investigate heterogeneity in integrated synthesis using QCA.

3.4.14. Treatment of qualitative research

As noted above, qualitative research will be incorporated to answer review questions 2 and 3.

CONTRIBUTIONS OF AUTHORS

Content: Sarah Dickin, Naomi Carrard, Louisa Gosling, Lewnida Sara, Marni Sommer, Hugh Sharma Waddington.

Systematic review methods: Biljana Macura, James Thomas, Karin Hannes, Hugh Sharma Waddington.

Statistical analysis: Biljana Macura, James Thomas, Hugh Sharma Waddington.

Information retrieval: Laura Del Duca, Adriana Soto.

DECLARATIONS OF INTEREST

Authors declare no conflict of interest. Reviewers will be prevented from taking part in inclusion decisions or validity assessment of articles they authored.

PRELIMINARY TIMEFRAME

Approximate date for submission of the systematic review: December 2021.

PLANS FOR UPDATING THIS REVIEW

At the moment we do not plan any updates due to limited resources.

SOURCES OF SUPPORT

Internal sources

This review project is co‐funded by Stockholm Environment Institute.

External sources

This review project is funded by the Centre of Excellence for Development Impact and Learning (https://cedilprogramme.org/funded-projects/programme-of-work-1/gender-and-social-outcomes-of-wash-interventions/).

Supporting information

Supporting information

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We are extremely grateful to all the stakeholders who provided valuable comments and inputs on the background and scope, the theory of change and search strategy of this protocol. We are thankful to Alison Bethel and Claire Stansfield for providing advice for bibliographic searches.

| Title | Methodological expectations of Campbell Collaboration intervention reviews: Conduct standards |

| Authors | The Methods Group of the Campbell Collaboration |

| DOI | 10.4073/cpg.2016.3 |

| No. of pages | 23 |

| Last updated | 28 October 2019 |

| Citation |

The Methods Group of the Campbell Collaboration. Methodological expectations of Campbell Collaboration intervention reviews: Conduct standards Campbell Policies and Guidelines Series No. 3 DOI: 10.4073/cpg.2016.3 |

| ISSN | 2535‐2458 |

| Copyright |

© The Campbell Collaboration This is an open‐access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. |

| Acknowledgement |

Adaptations on MECIR Version 2.2 Conduct Standards (Chandler, Churchill, Higgins, Lasserson, & Tovey, 2012) October 2019‐ updated to remove section numbers for Cochrane Handbook since these are out of date with the new Cochrane Handbook published in October 2019 |

| Editor in Chief | Vivian Welch, University of Ottawa, Canada |

| Chief Executive Officer | Howard White, The Campbell Collaboration |

| Managing Editor | Chui Hsia Yong, The Campbell Collaboration |

| The Campbell Collaboration was founded on the principle that systematic reviews on the effects of interventions will inform and help improve policy and services. Campbell offers editorial and methodological support to review authors throughout the process of producing a systematic review. A number of Campbell's editors, librarians, methodologists and external peer‐reviewers contribute. | |

|

The Campbell Collaboration P.O. Box 7004 St. Olavs plass 0130 Oslo, Norway |

Note for authors

This document provides detailed methodological expectations for the conduct of Campbell Collaboration systematic reviews of intervention effects. It is important to note that some Campbell reviews may not focus on intervention effects, but may synthesise observational research that is policy relevant. For instance, such reviews may examine correlational or descriptive research, diagnostic or test accuracy, or other topics that do not necessarily focus on intervention effects. Although most of the methodological expectations listed below will be appropriate for all review topics (intervention focused or not), some (particularly those related to study design) may not be entirely applicable to nonintervention reviews, and have been noted as such under the “rationale and elaboration” column.

Status: Mandatory means that a new protocol or review will not be published if this standard is not met. Highly desirable means that this should generally be done but that there are justifiable exceptions. There may be legitimate variation between or within Campbell Coordinating Groups in the relative emphasis placed on compliance with highly desirable standards. The emphasis placed on compliance with highly desirable standards will remain at the discretion of each Campbell Coordinating Group. Optional means this is done at the authors' discretion.The Campbell Collaboration Policies and Guidelines document and the Cochrane Handbook (2019) may be helpful references for additional details on conduct standards.

| Item No. | Status (T = Title, P = Protocol, R = Review) | Item Name | Standard | Rationale and elaboration | Authors note: pages where addressed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 |

Mandatory (T & P) |

Formulating review questions | Ensure that the review question and particularly the outcomes of interest, address issues that are important to stakeholders such as consumers, practitioners, policy makers, and others | Campbell reviews are intended to support practice and policy, not just scientific curiosity. The needs of consumers play a central role in Campbell Reviews and they should play an important role in defining the review question | 19‐20 |

| C2 |

Mandatory (T & P) |

Pre‐defining objectives | Define in advance the objectives of the review, including participants, interventions, comparators, and outcomes | Objectives give the review focus and must be clear before appropriate eligibility criteria can be developed. If the review will address multiple interventions, clarity is required on how these will be addressed (e.g., summarized separately, combined or explicitly compared). | 19 |

| C3 |

Highly desirable (P) |

Considering potential adverse effects | Consider any important potential adverse effects of the intervention(s) and ensure that they are addressed | It is important that adverse effects are addressed if applicable in order to avoid one‐sided summaries of the evidence. In these cases, the review will need to highlight the extent to which potential adverse effects have been evaluated in any included studies. Sometimes data on adverse effects are best obtained from nonrandomized studies, or qualitative research studies. This does not mean however that all reviews must include nonrandomized studies | 22 |

| C4 |

Highly desirable (P) |

Considering equity and specific populations | Consider in advance whether issues of equity and relevance of evidence to specific populations are important to the review, and plan for appropriate methods to address them if they are. Attention should be paid to the relevance of the review question to populations such as low socioeconomic groups, low or middle‐income regions, women, children, people with disabilities, and older people | Where possible reviews should include explicit descriptions of the effects of the interventions not only on the whole population but also describe their effects upon specific population subgroups and/or their ability to reduce inequalities and to promote their use to the community | 21 and 22 |

| C5 |

Mandatory (P) |

Pre‐defining unambiguous criteria for participants | Define in advance the eligibility criteria for participants in the studies | Pre‐defined, unambiguous eligibility criteria are a fundamental pre‐requisite for a systematic review. The criteria for considering types of people included in studies in a review should be sufficiently broad to encompass the likely diversity of studies, but sufficiently narrow to ensure that a meaningful answer can be obtained when studies are considered in aggregate. Considerations when specifying participants include setting, age, identifying personal characteristics, demographic factors, and other factors that differentiate the participants. Any restrictions to study populations must be based on a sound rationale, since it is important that Campbell reviews are widely relevant | 21 |

| C6 |

Highly desirable (P) |

Pre‐defining a strategy for studies with a subset of eligible participants | Define in advance how to handle studies in which only a subset of the sample is eligible for inclusion in the review | Sometimes a study includes some “eligible” participants and some “ineligible” participants, for example when an age cut‐off is used in the review's eligibility criteria. In case data from the eligible participants cannot be retrieved, a mechanism for dealing with this situation should be pre‐specified | 21 |

| C7 |

Mandatory (P) |

Pre‐defining unambiguous criteria for interventions and comparators | Define in advance the eligible interventions and the interventions against which these can be compared in the included studies | Pre‐defined, unambiguous eligibility criteria are a fundamental pre‐requisite for a systematic review. Specification of comparator interventions requires particular clarity, including the extent to which the experimental interventions are compared with a control or comparison conditions with matched or similar participants. Any restrictions on interventions and comparators, such as regarding delivery, dose, duration, intensity, co‐interventions, and features of complex interventions should also be pre‐defined and explained | 21‐22 |

| C8 |

Mandatory (P & R) |

Clarifying role of outcomes | Clarify in advance whether outcomes listed under “Criteria for Inclusion and Exclusion of Studies in the Review” are used as criteria for including studies (rather than as a list of the outcomes of interest within whichever studies are included) | Outcome measures need not always form part of the criteria for including studies in a review. However, some reviews do legitimately restrict eligibility to specific outcomes. For example, the same intervention may be studied in the same population for different purposes (e.g., reading interventions); or a review may address specifically the adverse effects of an intervention used for several conditions. If authors do exclude studies on the basis of outcomes, care should be taken to ascertain that relevant outcomes are not available because they have not been measured rather than simply not reported | 22 |

| C9 |

Mandatory (P) |