Abstract

Objective

To assess and compare demographic, clinical, neuroimaging, and pathologic characteristics of a cohort of patients with right hemisphere–predominant vs left hemisphere–predominant logopenic progressive aphasia (LPA).

Methods

This is a case-control study of patients with LPA who were prospectively followed at Mayo Clinic and underwent [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET scan. Patients were classified as rLPA if right temporal lobe metabolism was ≥1 SD lower than left temporal lobe metabolism. Patients with rLPA were frequency-matched 3:1 to typical left-predominant LPA based on degree of asymmetry and severity of temporal lobe metabolism. Patients were compared on clinical, imaging (MRI, FDG-PET, β-amyloid, and tau-PET), and pathologic characteristics.

Results

Of 103 prospectively recruited patients with LPA, 8 (4 female) were classified as rLPA (7.8%); all patients with rLPA were right-handed. Patients with rLPA had milder aphasia based on the Western Aphasia Battery–Aphasia Quotient (p = 0.04) and less frequent phonologic errors (p = 0.015). Patients with rLPA had shorter survival compared to typical LPA: hazard ratio 4.0 (1.2–12.9), p = 0.02. There were no other differences in demographics, handedness, genetics, or neurologic or neuropsychological tests. Compared to the 24 frequency-matched patients with typical LPA, patients with rLPA showed greater frontotemporal hypometabolism of the nondominant hemisphere on FDG-PET and less atrophy in amygdala and hippocampus of the dominant hemisphere. Autopsy evaluation revealed a similar distribution of pathologic findings in both groups, with Alzheimer disease pathologic changes being the most frequent pathology.

Conclusions

rLPA is associated with less severe aphasia but has shorter survival from reported symptom onset than typical LPA, possibly related to greater involvement of the nondominant hemisphere.

Logopenic progressive aphasia (LPA), a variant of primary progressive aphasia (PPA),1 is a neurodegenerative language disorder characterized by anomia, hesitant spontaneous speech, frequent phonologic errors, and impaired retention and repetition of long and complex spoken stimuli.2 Due to the more frequent lateralization of language function to the left hemisphere in both right- and left-handed individuals,3,4 the LPA syndrome is typically accompanied by atrophy or hypometabolism of the left hemisphere, particularly in a temporoparietal distribution.5 Nevertheless, cases of LPA with predominantly right hemispheric involvement have been reported.6-9 Notably, all of them have occurred in right-handed individuals, often termed dextrals, therefore often designated as representing crossed aphasia in dextrals (CAD).10,11

CAD is a rare syndrome occurring in 1%–3% of right-handed individuals with right-hemispheric focal damage typically associated with vascular insults.12,13 Recent evidence suggests that CAD is more frequent in LPA, with one study reporting a frequency of 26%.14 Due to a gap in the understanding of right hemisphere–predominant LPA (rLPA), it is of interest to characterize it and explore whether and how it differs from the typical left hemisphere–predominant LPA.

We developed and applied criteria to identify patients with rLPA based on [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose-PET (FDG-PET) and compared their demographic, clinical, neuroimaging, and pathologic characteristics to matched patients with typical LPA. Because hippocampal atrophy and different patterns of hippocampal subfield vulnerability were described in atypical Alzheimer disease (AD),15,16 we additionally investigated whether there are different patterns of hippocampal atrophy in rLPA vs typical LPA.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

We conducted a case-control clinical-imaging study using data from 103 patients who had been recruited into multiple NIH-funded observational studies (SLD1 and ATA3), and prospectively followed by the Neurodegenerative Research Group (NRG) at Mayo Clinic between 2010 and 2019. They completed a standardized research battery of validated tests, received an LPA diagnosis based on published clinical criteria by consensus,1,2 and completed a FDG-PET scan. SLD1 recruited patients between 2010 and 2016 with a diagnosis of PPA, including LPA, and ATA3 recruited patients between 2016 and the present with an atypical Alzheimer dementia diagnosis including LPA. For all patients, aphasia was the initial complaint, the most debilitating impairment, and was insidious in onset with a progressive course. Patients were screened for language abnormalities including (1) impaired single-word retrieval in spontaneous speech and naming, (2) impaired repetition of sentences and phrases, (3) presence of phonologic errors in speech, (4) spared single-word comprehension and object knowledge, (5) spared motor speech, and (6) absence of overt agrammatism in speech and writing. Imaging was not required to support LPA diagnosis.

Twenty individuals serving as imaging controls for the voxel-based analysis only were recruited from the community (Rochester, Minnesota) by NRG. They were sex- and age-matched to the patients with LPA: 50% female, median age at scan 63 years (range 49–81). These imaging controls had no cognitive complaints, had a median 15 years of education (range 12–19), performed normally on the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) with mean score of 27 (range 26–28), and had undergone brain imaging but had no other neurologic testing besides MoCA.

FDG-PET Scan and Case vs Control Designation

All FDG-PET scans were acquired using a GE PET/CT scanner. Patients were injected with 18F-FDG of ∼459 MBq (range 367–576 MBq), and after a 30-minute uptake period, underwent an 8-minute 18F-FDG scan. Emission data were reconstructed into a 256 × 256 matrix with a 30-cm field of view (pixel size = 1.0 mm, slice thickness = 1.96 mm). All patients also underwent an MRI protocol that included a 3D magnetization-prepared rapid-acquisition gradient-echo (MPRAGE) scan. Individual patterns of hypometabolism were analyzed using 3D stereotactic surface projections17 and the CortexID suite (GE Healthcare [gehealthcare.co.uk/-/media/13c81ada33df479ebb5e45f450f13c1b.pdf]), whereby activity at each voxel is normalized to the pons and Z scored to an age-segmented normative database. Average Z scores for left and right lateral temporal lobes were outputted from CortexID for each patient (negative scores represent hypometabolism). To be considered rLPA, a patient had to have metabolism in the right temporal lobe ≥1 SD (Z score) lower than metabolism in the left temporal lobe. The hemisphere with more severe hypometabolism in the lateral temporal lobe (defined by a lower Z score) was considered dominant, and the hemisphere with less severe hypometabolism in the same region was considered nondominant. That is, dominant hemisphere for rLPA was always the right hemisphere, and for typical LPA, the left hemisphere. Asymmetry scores (nondominant Z score minus dominant Z score) were calculated.

Of the 103 patients with LPA, 8 (7.8%) met our criteria for rLPA and were frequency-matched 1:3 to 24 patients with typical LPA (left hemisphere–predominant) by an equally reversed degree of asymmetry based on Z scores and severity of metabolism of the lateral temporal lobe (average of left and right). Therefore, a total of 32 patients were included in this case-control study. All patients underwent genetic evaluation for APOE genotype.

Neurologic Evaluation

Neurologic examination was performed by an experienced, board-certified behavioral neurologist (K.A.J. or J.G.-R.). The following battery of tests was completed: MoCA with calculation, forward and backward digit span subscores reported separately; the Limb Apraxia subtest of the Western Aphasia Battery (WAB); the Frontal Behavioral Inventory (FBI); the Neuropsychiatric Inventory–Questionnaire (NPI-Q); and the Movement Disorders Society–sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson's Disease Rating Scale part III.

Speech and Language Evaluation

The speech–language assessment was performed by a speech–language pathologist (J.R.D.). Global language ability and aphasia severity were indexed by the WAB Aphasia Quotient (AQ). Certain subscores of the WAB were reported separately: fluency, sequential commands, reading irregular words, reading nonsense words, writing irregular words, and writing nonsense words. Additional tests included the WAB repetition, the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination (BDAE) repetition, and the 15-item Boston Naming Test. Repetition was categorized as abnormal when the BDAE repetition score was <8 or when the WAB repetition score was <9.77. The WAB repetition cut-off value represents a score of ≥2 SDs below the mean score of WAB repetition in an independent, healthy control cohort.5 Standardized writing samples from the WAB were reviewed for evidence of agrammatism.2 The articulatory errors score (AES)18 was used to index the frequency of phonologic errors in speech, given that none of the patients in the study made errors in speech attributable to a motor speech disorder (apraxia of speech or dysarthria).1,2

Neuropsychological Evaluation

Neuropsychological evaluation of patients with LPA was overseen by an experienced neuropsychologist (M.M.M.) independently of the neurologic and speech/language assessments. Cognitive tests targeting functions mainly localized to the left hemisphere included animal fluency and letter fluency. Tests targeting right hemispheric function included a facial recognition test and the Visual Object and Space Perception cube and incomplete letters subtests,19 tests of visuospatial and visuoperceptual functioning. Other assessed cognitive domains included object knowledge, the Pyramids and Palm Trees test,20 object-object version; visual perception and visuoconstructional praxis, the Rey-Osterrieth Complex Figure Test; and episodic memory, the Auditory Verbal Learning Test (AVLT) long-term recall. Norms used in this study have been previously described.21-23

Voxel-Level FDG-PET Analysis

Voxel-level analyses of FDG-PET were also performed to assess patterns of hypometabolism across the brain. Before analysis, the FDG-PET and MPRAGE scans from the patients with rLPA were left-right flipped so that the dominantly affected hemisphere was on the same side of the image for both rLPA and typical LPA. This allowed us to compare involvement in the dominant and nondominant hemisphere between groups. FDG-PET images were each registered to the participant's MPRAGE using Statistical Parametric Mapping 12 (SPM12) software (fil.ion.ucl.ac.uk/spm/software/spm12/), 6 degrees of freedom registration. Normalization measures were computed between each MPRAGE and the Mayo Clinic Adult Lifespan Template (MCALT) (nitrc.org/projects/mcalt/) using advanced neuroimaging tools.24 Within these measures, the MCALT atlases were propagated to native MRI space. All voxels in the MPRAGE space FDG-PET images were divided by the median uptake in the pons using the MCALT atlas to create standard uptake value ratio (SUVR) images. These SUVR images were normalized to the MCALT and smoothed at 6 mm full width at half maximum. Analyses were performed without partial volume correction (PVC) and also repeated with PVC. Voxel-level comparisons of FDG-PET SUVR images were performed using SPM12. The rLPA and typical LPA groups were compared to cognitively intact imaging controls, and the LPA groups were compared to each other. All comparisons to controls were performed at a family-wise error correction of p < 0.05; all direct comparisons were performed at a false discovery rate correction of p < 0.05.

Molecular PET Imaging

Of the 32 study patients, 31 had antemortem β-amyloid PET imaging with Pittsburgh compound B (PiB) using a GE PET/CT scanner. Briefly, patients were injected with ∼628 MBq (range, 385–723 MBq) of PiB, and after a 40-minute uptake period, a 20-minute PiB scan was obtained. Global PiB SUVR was calculated as previously described with a cut-point of 1.48 used to define PiB-PET positivity.25

Ten of the 32 study patients had antemortem tau PET imaging with [18F] flortaucipir performed with a GE PET/CT scanner. Briefly, patients were injected with ∼370 MBq (range, 333–407 MBq) of [18F] AV-1451 (flortaucipir), followed by a 20-minute PET acquisition performed 80 minutes after injection. Emission data were reconstructed as described for FDG-PET. Flortaucipir PET images were divided by uptake in the cerebellar crus gray matter to create SUVR images. Regional flortaucipir values were outputted using MCALT.

MRI Analysis of Medial Temporal Lobe

Total gray matter volume, hemispheric gray matter volumes, as well as gray matter volumes of the left and right hippocampus, amygdala, entorhinal cortex, parahippocampal gyrus, and hippocampal subfields, were quantified using Freesurfer software version 6.0 (surfer.nmr.mgh.harvard.edu). Each hippocampus was segmented into the following subfields: CA1, CA2, CA3, CA4, molecular and granule cell layers of the dentate gyrus (granule cell layer–molecular layer–dentate gyrus), subiculum, hippocampal amygdala transition area, presubiculum, parasubiculum, fimbria, molecular layer of the hippocampus, hippocampal tail, and hippocampal fissure. All gray matter volumes were adjusted for total intracranial volume.

Pathologic Evaluation

All patients who had died and had previously agreed to a postmortem examination underwent brain autopsy according to standard neuropathologic examination by a board-certified neuropathologist (D.W.D.) according to Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease26 with thioflavin S fluorescent microscopy, which was used to assign Braak neurofibrillary tangle stage,27 Thal phase,28 neuritic plaque density, and cerebral amyloid angiopathy scores.29 The presence of Lewy bodies in the brainstem, limbic system, amygdala, and neocortex was staged according to the Braak Lewy body staging scheme.30 Diagnoses of AD or Lewy body disease were based on consensus recommendations.31,32 Patients with AD pathologic diagnosis were subtyped into typical and hippocampal-sparing AD variants as previously described.33 Trans-active response DNA-binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43) pathology was considered positive if it was identified in the amygdala.34 Hippocampal sclerosis was diagnosed based on consensus recommendations.35 Arteriolosclerosis was rated semiquantitatively as none, mild, moderate, or severe. Only the left hemisphere was examined in all but 2 cases where examined hemisphere was not specified (1 rLPA, 1 typical LPA).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses, except for survival analysis, were performed in JMP software (version 15; SAS Institute). Significance was set at p < 0.05. Figures were generated in RStudio software (version 1.2.5042; RStudio Inc.) and Prism 8 (version 9.2.1 [441]; GraphPad Software, Inc.). Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals (95% CIs) were calculated for clinical data based on 1 unit increase in the predictor; p values are from likelihood ratio test. For imaging and pathologic data, Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare continuous variables, and Fisher exact test was used to compare categorical variables. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed for supplemental WAB reading and writing tasks adjusted for WAB-AQ. For survival analysis, we fit a Cox proportional hazard model to distinguish a difference in overall survival between rLPA and typical LPA. This model used survival time from disease onset to death as the outcome predicted by left- or right-sided disease. We also performed sensitivity analysis by adjusting the model for age at onset. Both models were fit using the statistical software R36 version 3.6.2 with the survival package version 3.2–7.37 There was little evidence that the assumption of proportional hazards was violated (Schoenfeld p value = 0.885).

Standard Protocol Approvals, Registrations, and Patient Consents

This study was approved by the Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board and all patients or their proxies signed a written informed consent form before taking part in any research activities in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Data Availability

Anonymized data are available from the corresponding author upon request from any qualified investigator for purposes of replicating procedures and results.

Results

Demographic, Genetic, and Clinical Associations

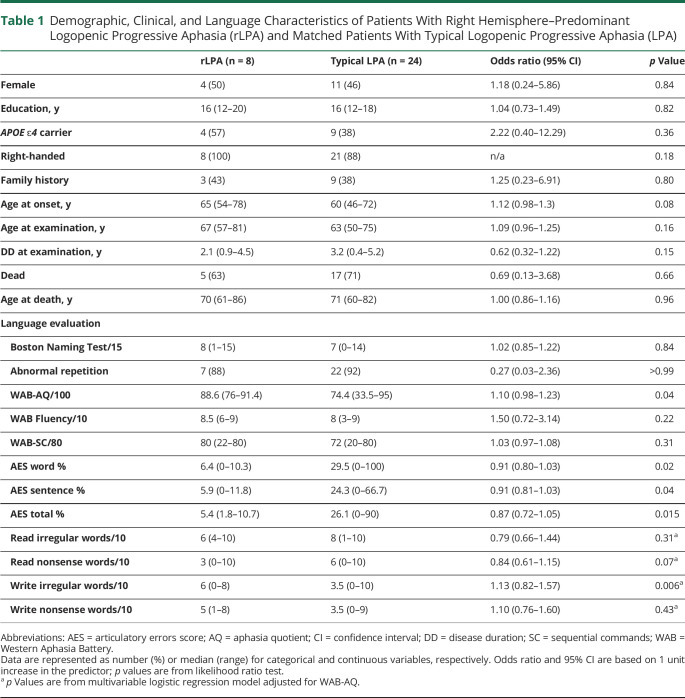

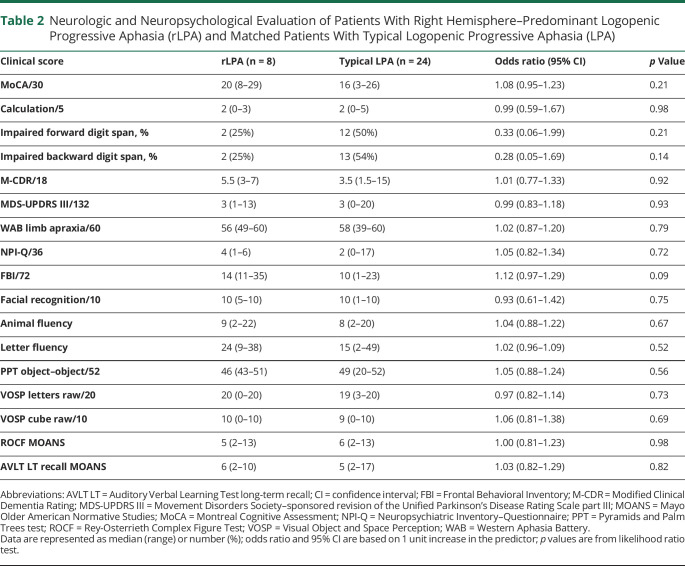

Demographic, genetic, and clinical data are summarized in tables 1 and 2. Patients with rLPA did not differ from patients with typical LPA in demographics, APOE ɛ4 frequency, and in the majority of the clinical tests. However, the patients with rLPA had milder aphasia severity compared to typical LPA based on the WAB-AQ. After adjusting for WAB-AQ, patients with rLPA also performed better at writing irregular words. Total AES frequency, as well as word and sentence AES, was lower in rLPA compared to typical LPA. Although not statistically significant, patients with rLPA tended to be older at symptom onset and had higher scores on the FBI. None of the patients with rLPA had a history of learning disabilities.

Table 1.

Demographic, Clinical, and Language Characteristics of Patients With Right Hemisphere–Predominant Logopenic Progressive Aphasia (rLPA) and Matched Patients With Typical Logopenic Progressive Aphasia (LPA)

Table 2.

Neurologic and Neuropsychological Evaluation of Patients With Right Hemisphere–Predominant Logopenic Progressive Aphasia (rLPA) and Matched Patients With Typical Logopenic Progressive Aphasia (LPA)

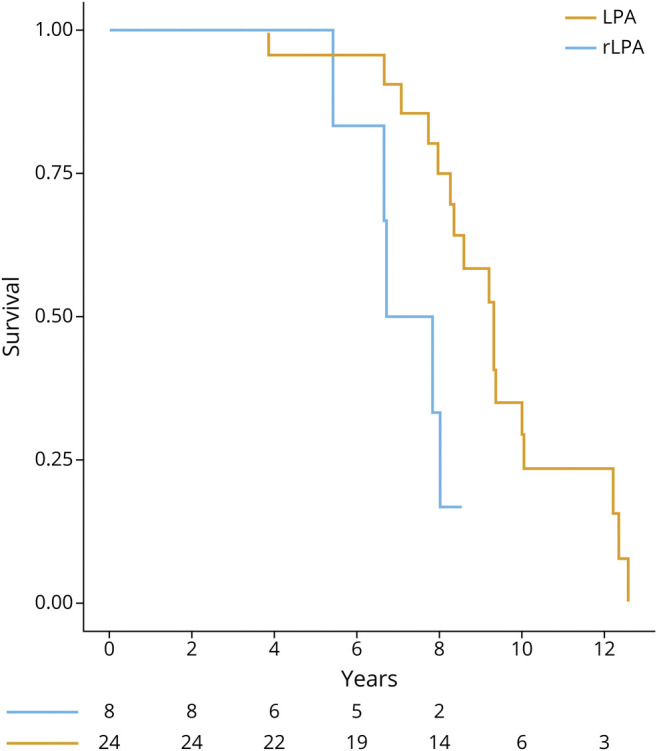

Survival Analysis

Proportional hazards model detected a difference in survival between rLPA and typical LPA: log-rank (Mantel-Cox), p = 0.01. Patients with rLPA had shorter survival periods from symptom onset compared to typical LPA: hazard ratio (HR) (95% CI) 4.0 (1.2–12.9), p = 0.02 (figure 1). The results of the second model adjusted for age at onset were as follows: HR for the time of onset to death 3.6, p = 0.04; HR for 1-year difference in age at onset 1.01, p = 0.67.

Figure 1. Kaplan-Meier Curves Reflecting Survival Differences in Right Hemisphere–Predominant Logopenic Progressive Aphasia (rLPA) vs Typical Logopenic Progressive Aphasia (LPA).

Patients with rLPA show shorter survival from the symptom onset compared to patients with typical LPA.

Neuroimaging Findings

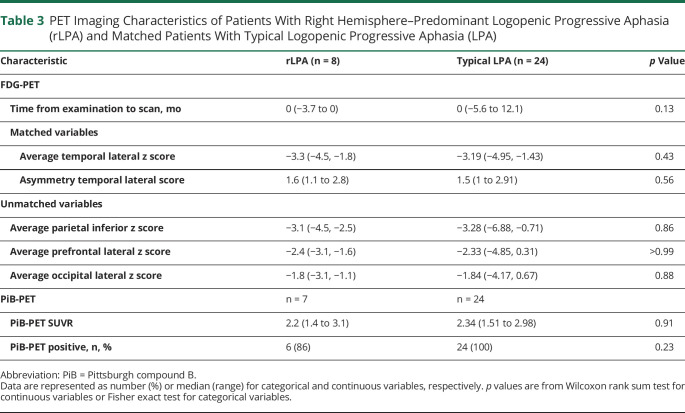

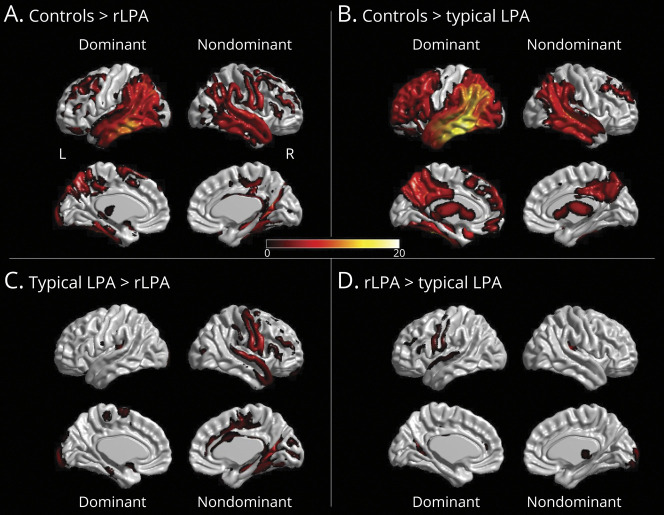

FDG-PET and PiB PET findings are summarized in table 3. In the voxel-level analysis, patients with rLPA showed temporoparietal hypometabolism and milder frontal hypometabolism in both the dominant and nondominant hemispheres, with greater involvement of the dominant hemisphere and additional hypometabolism in the sensorimotor cortex in the nondominant hemisphere, compared to cognitively intact imaging controls (figure 2A). The patients with typical LPA similarly showed temporoparietal and frontal hypometabolism in both the dominant and nondominant hemisphere, with greater involvement of the dominant hemisphere and additional hypometabolism in the occipital lobe of the dominant hemisphere, compared to cognitively intact imaging controls (figure 2B). When compared to patients with typical LPA, patients with rLPA had more severe hypometabolism in the superior temporal, perisylvian, sensorimotor, and frontal cortices of the nondominant hemisphere (figure 2C). Conversely, patients with typical LPA had more severe hypometabolism in the sensorimotor cortex of the dominant hemisphere compared to patients with rLPA (figure 2D). There was no difference across groups in the overall degree of hypometabolism or in global PiB-PET SUVR.

Table 3.

PET Imaging Characteristics of Patients With Right Hemisphere–Predominant Logopenic Progressive Aphasia (rLPA) and Matched Patients With Typical Logopenic Progressive Aphasia (LPA)

Figure 2. 3D Brain Renderings Showing Results of FDG-PET Analyses in Right Hemisphere–Predominant Logopenic Progressive Aphasia (rLPA) and Typical Logopenic Progressive Aphasia (LPA).

Hypometabolism in dominant and nondominant hemisphere in rLPA or LPA compared to age- and sex-matched controls in shown in A and B, respectively, punc < 0.001 for family-wise error = 0.05. Comparison of hypometabolism in dominant and nondominant hemisphere in rLPA against typical LPA is shown in C and typical LPA against rLPA is shown in D, punc < 0.001 for false discovery rate = 0.05. The FDG-PET and magnetization-prepared rapid-acquisition gradient-echo scans from the patients with rLPA were left–right flipped, so that the dominantly affected hemisphere was on the same side of the image for both rLPA and typical LPA.

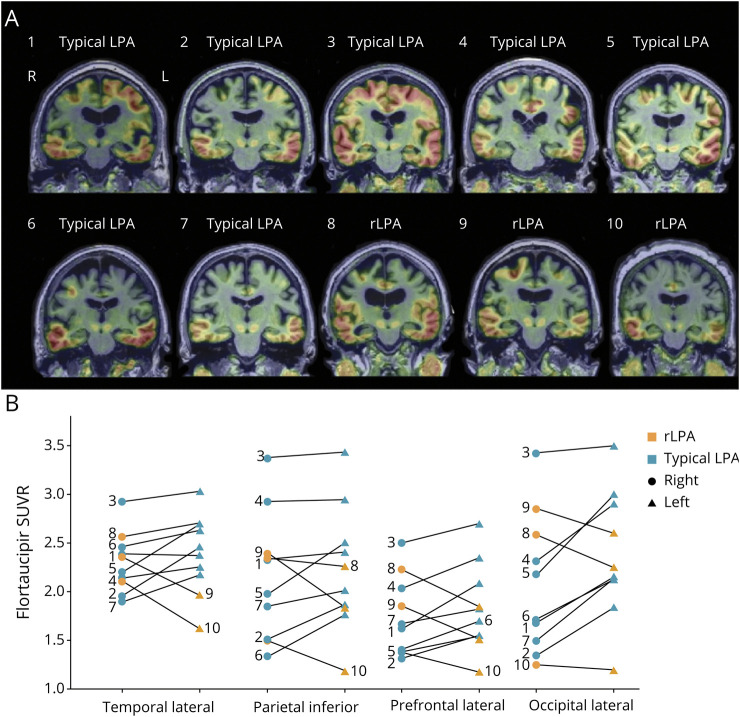

A subset of patients had flortaucipir PET images and regional flortaucipir SUVR values, shown in figure 3. Tau burden, measured by flortaucipir uptake, showed evidence for lateralization to the side with greater hypometabolism in most cases.

Figure 3. Flortaucipir PET Standard Uptake Value Ratio (SUVR) Images in Typical Logopenic Progressive Aphasia (LPA) and Right Hemisphere–Predominant LPA (rLPA).

Flortaucipir uptake lateralizes to the hemisphere with greater hypometabolism in most of the cases with a few cases showing symmetrical flortaucipir uptake (A). Regional flortaucipir uptake is greater in the left hemisphere in all regions for all patients with typical LPA and greater in the right hemisphere in all regions for all patients with rLPA with an exception of 1 rLPA patient with higher left temporal lateral flortaucipir uptake (B). Symbols connected by the gray line represent regional flortaucipir uptake of a single patient. Numbers associated with individual flortaucipir PET scans in A correspond to individual regional flortaucipir SUVR values in B.

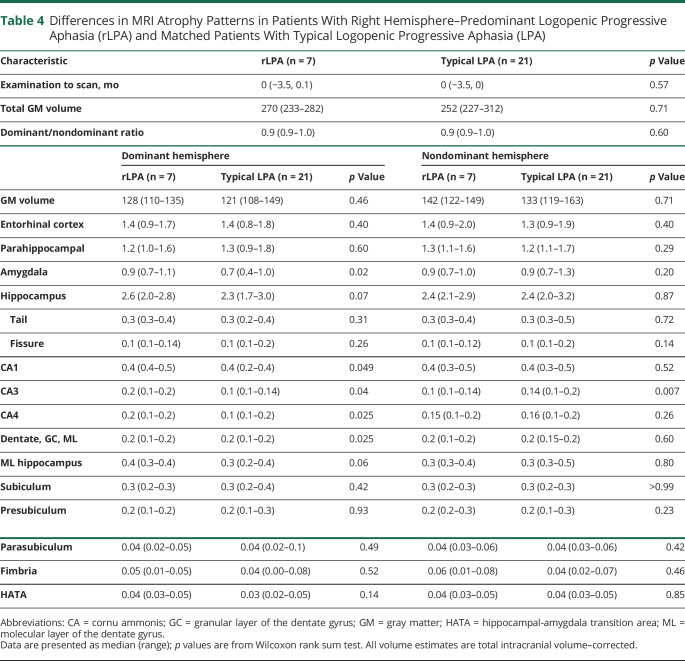

Volumetric differences between rLPA and typical LPA are summarized in table 4. Patients with rLPA had larger amygdala volumes in the dominant hemisphere compared to patients with typical LPA, with a trend for larger volumes of the hippocampus. Subanalysis of the hippocampal subfields in the dominant hemisphere also showed more preserved volumes in rLPA in the following regions: granule cell layer–molecular layer–dentate gyrus, CA1, CA2, CA3, and molecular layer of the hippocampus. In the nondominant hemisphere, patients with rLPA had more atrophy in CA3 but no other differences from typical LPA.

Table 4.

Differences in MRI Atrophy Patterns in Patients With Right Hemisphere–Predominant Logopenic Progressive Aphasia (rLPA) and Matched Patients With Typical Logopenic Progressive Aphasia (LPA)

Pathologic Associations

Of the 32 patients with LPA in the study, 10 patients (5 patients with rLPA and 5 with typical LPA) died and underwent brain autopsy. All patients had high-to-intermediate likelihood of AD pathology. Interestingly, 4/5 (80%) patients with typical LPA, compared to 2/5 (40%) patients with rLPA, had hippocampal-sparing pathologic variant of AD. Copathologies were common in both groups: Lewy body disease was present in 80% of patients with typical LPA vs 20% of patients with rLPA. Two patients had diffuse Lewy body disease: 1 rLPA, 1 typical LPA. TDP-43 proteinopathy was equally frequent (40%) in rLPA and typical LPA. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy and arteriolosclerosis were present in ≥80% of patients in each group. There were no statistically significant differences in the frequency of pathologies or their distribution between rLPA and typical LPA.

Discussion

We found the frequency of rLPA to be ∼ 8%. Patients with rLPA had milder aphasia, made fewer phonologic errors, and made fewer errors in writing irregular words compared to patients with typical LPA. Notably, we found some evidence that patients with rLPA have shorter survival periods from reported symptom onset to death compared to patients with typical LPA. Compared to the patients with typical LPA, patients with rLPA also had more severe hypometabolism in regions of the nondominant hemisphere as well as less atrophy in the medial temporal lobe of the dominant hemisphere. There were no significant histologic differences between the groups, although most brains from patients with typical LPA showed hippocampal-sparing AD pathology, which was a less frequent AD pathologic variant for rLPA.

All patients with rLPA in our study were right-handed and therefore may be considered by some as examples of CAD. However, when compared to cognitively intact imaging controls, our patients with rLPA also had significant left hemisphere involvement (figure 2A), which could play a role in the aphasic characteristics of rLPA. Therefore, brain damage in LPA is more widespread than focal, as is the case for poststroke patients, where a CAD diagnosis strongly indicates atypical language lateralization. Some of our patients with rLPA might have right-hemisphere language lateralization and would meet criteria for CAD, but this is inconclusive in the absence of task-specific fMRI data. Nevertheless, given that the frequency of rLPA in this study was 8%, there may be a higher frequency of right hemisphere–predominant involvement in LPA compared to other PPA variants, where right greater than left hemisphere involvement occurs in only 1%–3%.14

The proportion of patients with rLPA in our LPA cohort was more modest than another LPA series in which rLPA cases comprised a quarter of all cases.14 A possible explanation for the discrepancy in the observed frequency may be differences in criteria; ours were based on quantitative asymmetric metabolism on FDG-PET scan with a specific cut-off value, whereas the other center relied on visual assessment. In fact, some FDG-PET scans in our cohort visually had more severe hypometabolism in the right lateral temporal lobe; however, the difference in z scores between the right and left was <1 SD. Hence, we opted to classify such cases as LPA with symmetrical involvement rather than rLPA or typical left-sided LPA.

The patients with rLPA in our study had milder aphasia and less frequent phonologic errors compared to patients with typical LPA but had comparable disease duration and severity of imaging findings. In several recent clinical-imaging studies, phonologic errors were associated with atrophy and hypometabolism in the left temporoparietal regions.38,39 Therefore, it is not surprising that the patients with rLPA made fewer phonologic errors than patients with typical LPA in the light of the less severe left-hemispheric involvement. It also explains the relatively preserved writing of irregular words compared to typical LPA, which has also been shown to localize to the left hemisphere.40 This finding suggests that the patients with rLPA in this study are more likely to have a typical left-hemisphere lateralization of language function. Nevertheless, if some of the patients with rLPA had language lateralization to the right hemisphere, less severe language impairment in these patients could be due to compensatory activation of the left temporal lobe. Compensatory recruitment of the right hemisphere has been demonstrated in left-hemisphere stroke survivors with poststroke aphasia41; however, the left temporal lobe might be more suited for language-related functions than the right and, therefore, account for better language performance in patients with rLPA compared to patients with typical LPA.

In our case-control study, the patients with rLPA were otherwise phenotypically indiscernible from patients with typical LPA based on the results of a battery of neurologic and neuropsychological testing, as reported in another case series.14 The latter study did find differences in working memory as measured by the digit span test.14 We cannot confirm or refute that finding, although we saw no evidence for a difference based on the forward and backward digit span subtest from the MoCA. Inclusion of 3 (12%) left-handed patients in the typical LPA group could have affected our results, as handedness is often considered when discussing language lateralization. Given that left-hemispheric language lateralization is more common for both right and left-handed individuals with <30% of left-handers have atypical language lateralization,4 it is unlikely our results were significantly affected. In addition, our case vs control designation was based on imaging criteria and not handedness.

Notably, we found no differences in performance on neuropsychological tests targeting functions lateralizing to the right hemisphere including visuoperceptual, visual spatial, and constructional skills (constructional apraxia) and facial recognition. Future studies assessing differences between rLPA and typical LPA should employ additional test batteries assessing other right-hemisphere functions such as dressing, topographic orientation, emotional indifference, aprosodia, and theory of mind,42 which may allow for discernment of rLPA from typical LPA.

Interestingly, we observed that caregivers of the patients with rLPA tended to endorse more behaviors on the FBI compared to caregivers of the patients with typical LPA. More overt behaviors (e.g., perseveration, compulsion, and disinhibition) are more characteristic of patients with right versus left hemisphere involvement and have been reported in the right-temporal variant of frontotemporal dementia.43-45

An important finding of the present study is the shorter survival period of patients with rLPA from symptom onset. This is intriguing given that the patients with rLPA had a milder aphasic clinical phenotype initially. Possibly, the patients with rLPA had subtle symptoms present earlier than reported due to lack of insight, anosognosia (ignoring symptoms), or anosodiaphoria (not attaching importance to symptoms) resulting from right hemispheric involvement.46 However, upon careful review of clinical histories obtained from caregivers, we did not find any evidence suggesting anosognosia or anosodiaphoria. Furthermore, it would have required loss of insight on the part of the caregiver contributing to the history as well as the patient. It may be that right hemisphere–associated impairment is less likely to cause significant patient and caregiver distress and hence may have been perceived as age-related changes. Lastly, early cognitive deficits unrecognized by both the patient and the caregiver could have been revealed with additional early formal neuropsychological testing. However, early symptoms might also have gone undetected in patients with typical LPA. Hence, while the disease duration in reality might have been longer for both groups, it would have not eliminated the difference in disease duration and survival. In addition, as mentioned above, traditional neuropsychological batteries have fewer tests designed to evaluate cognitive functions specific to the right hemisphere; even if patients with rLPA were tested earlier, it is unlikely that they would have been diagnosed earlier. Therefore, it is unclear what accounts for the shorter survival from symptom onset in our patients with rLPA. We also do not know the causes of death in our patients, which may provide a clue to the shorter survival in patients with rLPA. Lastly, validation of survival in a larger multicenter cohort would be of benefit.

Pathologic evaluation of the patients in our cohort provided no evidence to account for the observed clinical, survival, and neuroimaging differences. We found no differences in terms of types, frequency, or burden of pathologies encountered, with all patients meeting criteria for high/intermediate likelihood of AD. One possible explanation is that the pathologic examination was limited to the left hemisphere as per protocol in which the left hemisphere is formalin-fixed for histologic examination while the right is flash-frozen. However, if both hemispheres were to be examined in a patient with LPA, the dominantly affected hemisphere would be expected to have more atrophy and higher burden of pathologies compared to the nondominant hemisphere. Furthermore, there might be differences in the presence, burden, and distribution of additional copathologies.47

We identified neuroimaging differences in our study. The patients with rLPA had more hypometabolism in the nondominant hemisphere, denoting more bilateral involvement in patients with rLPA compared to patients with typical LPA, which could potentially contribute to shorter survival. It should be noted that voxel-based analysis comparison would have assessed nontemporal regions by design, since we matched for lateral temporal lobe hypometabolism. Therefore, matching could have reduced the differences observed in the nondominant hemisphere. Interestingly, we observed more preserved amygdala and hippocampi volumes in the dominant hemisphere of patients with rLPA compared to typical LPA. Hippocampal subfield analysis revealed regions of the dominant hemisphere in patients with rLPA that were relatively spared compared to the same regions in the dominant hemisphere in typical LPA. These included the cornu Ammonis regions (CA1, CA3, CA4), the molecular layer of hippocampus, and the molecular and granular cell layers of the dentate gyrus, all regions participating in both encoding and retrieval of information.48,49 Nevertheless, it is not surprising that we did not observe any differences in memory performance between rLPA and typical LPA in verbal memory as assessed by the AVLT, given that the left hippocampal formation of typical LPA and rLPA were similar in volume (see table 4; analyses reported above do not compare left hippocampus in typical LPA to left hippocampus in rLPA).

In addition to clinical, MRI, FDG-PET, and pathologic findings, we also assessed for differences related to the presence of the APOE ɛ4 allele and β-amyloid (Aβ) burden as measured by molecular PET. We did not find any differences in the frequency of the APOE ɛ4 allele or Aβ burden; the latter supports a previous study, which also did not find differences in Aβ burden based on CSF analysis.14 We did see some evidence for greater flortaucipir uptake in the right hemispheric regions in patients with rLPA and greater uptake in the left hemispheric regions for patients with typical LPA; however, our sample size with flortaucipir imaging was too small for statistical analysis.

There were several strengths to our study, including our strict criteria based on neuroimaging for rLPA diagnosis; careful matching; detailed clinical examinations; and multimodal neuroimaging with FDG-PET, 3.0T volumetric MRI, and amyloid determination with PiB PET, flortaucipir PET, and autopsy examination in a subset. To our knowledge, this is one of the largest series of patients with rLPA reported from a single center, although due to rarity of this syndrome, the sample size is still small. Limitations of our study include limited cognitive tests to assess right frontal lobe function, the fact that not all patients had flortaucipir PET, not all deceased patients had autopsy examination, and autopsies that were limited to one hemisphere. Exclusion of the patients with LPA with more symmetric patterns of hypometabolism may limit the generalizability of the findings to patients with LPA with less striking difference in hypometabolism between right and left hemisphere. Lastly, our patients were not racially diverse, with all patients being Caucasian, of European descent, and of non-Hispanic ethnicity. Nevertheless, patients enrolled in this study come from different cities and states across the United States, and the methods used for comparison are widely used by other centers, making the findings of the present study generalizable.

We conducted a detailed clinical, multimodal neuroimaging and neuropathologic analysis of patients with rLPA compared to patients with typical LPA. We identified several differences; most importantly, a shorter survival period, which has clinical relevance for prognosis. Further research is warranted to investigate additional clinical features, mechanistic pathways, and biological factors to account for the faster progression to death of patients with rLPA compared to patients with typical LPA.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank Lea Dacy for assistance with formatting this manuscript.

Glossary

- Aβ

β-amyloid

- AD

Alzheimer disease

- AES

articulatory errors score

- AQ

Aphasia Quotient

- AVLT

Auditory Verbal Learning Test

- BDAE

Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination

- CAD

crossed aphasia in dextrals

- CI

confidence interval

- FBI

Frontal Behavioral Inventory

- FDG

fluorodeoxyglucose

- HR

hazard ratio

- LPA

logopenic progressive aphasia

- MCALT

Mayo Clinic Adult Lifespan Template

- MoCA

Montreal Cognitive Assessment

- MPRAGE

magnetization-prepared rapid-acquisition gradient-echo

- NRG

Neurodegenerative Research Group

- PiB

Pittsburgh compound B

- PPA

primary progressive aphasia

- PVC

partial volume correction

- rLPA

right hemisphere–predominant logopenic progressive aphasia

- SUVR

standard uptake value ratio

- TDP-43

trans-active response DNA-binding protein 43 kDa

- WAB

Western Aphasia Battery

Appendix. Authors

Study Funding

NIH grants R01 DC10367 and R01 AG50603.

Disclosure

M. Buciuc, J.R. Duffy, M.M. Machulda, J. Graff-Radford, N.T.T. Pham, P.R. Martin, and M.L. Senjem report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. C.R. Jack Jr. has consulted for Biogen, served as a speaker for Eisai, and serves on an independent data monitoring board for Roche, but receives no personal compensation from any commercial entity. N. Ertekin-Taner and D.W. Dickson report no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. V.J. Lowe consults for Bayer Schering Pharma, GE Healthcare, Avid Radiopharmaceuticals, Eisai, and Merck Research and receives research support from GE Healthcare, Siemens Molecular Imaging, and Avid Radiopharmaceuticals. J.L. Whitwell reports grants from NIH. K.A. Josephs reports grants from NIH. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76(11):1006-1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Botha H, Duffy JR, Whitwell JL, et al. Classification and clinicoradiologic features of primary progressive aphasia (PPA) and apraxia of speech. Cortex. 2015;69:220-236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szaflarski JP, Binder JR, Possing ET, McKiernan KA, Ward BD, Hammeke TA. Language lateralization in left-handed and ambidextrous people: fMRI data. Neurology. 2002;59(2):238-244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Knecht S, Dräger B, Deppe M, et al. Handedness and hemispheric language dominance in healthy humans. Brain. 2000;123:2512-2518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gorno-Tempini ML, Dronkers NF, Rankin KP, et al. Cognition and anatomy in three variants of primary progressive aphasia. Ann Neurol. 2004;55(3):335-346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cabrera-Martín M, Matías-Guiu J, Yus-Fuertes M, et al. 18F-FDG PET/CT and functional MRI in a case of crossed logopenic primary progressive aphasia. Rev Esp Med Nucl Imagen Mol. 2016;35(6):394-397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Demirtas-Tatlidede A, Gurvit H, Oktem-Tanor O, Emre M. Crossed aphasia in a dextral patient with logopenic/phonological variant of primary progressive aphasia. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2012;26(3):282-284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parente A, Giovagnoli AR. Crossed aphasia and preserved visuospatial functions in logopenic variant primary progressive aphasia. J Neurol. 2015;262(1):216-218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jang YK, Park S, Kim HJ, et al. A dextral primary progressive aphasia patient with right dominant hypometabolism and tau accumulation and left dominant amyloid accumulation. Case Rep Neurol. 2016;8(1):78-86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Brown JW, Wilson FR. Crossed aphasia in a dextral: a case report. Neurology. 1973;23(9):907-911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bramwell B. On “crossed” aphasia and the factors which go to determine whether the “leading” or “driving” speech-centres shall be located in the left or in the right hemisphere of the brain: with notes of a case of “crossed” aphasia (aphasia with right-sided hemiplegia) in a left-handed man. Lancet. 1899;153(3953):1473-1479. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mariën P, Engelborghs S, Vignolo LA, De Deyn PP. The many faces of crossed aphasia in dextrals: report of nine cases and review of the literature. Eur J Neurol. 2001;8(6):643-658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mariën P, Paghera B, De Deyn PP, Vignolo LA. Adult crossed aphasia in dextrals revisited. Cortex. 2004;40(1):41-74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ferrari C, Polito C, Berti V, et al. High frequency of crossed aphasia in dextral in an Italian cohort of patients with logopenic primary progressive aphasia. J Alzheimers Dis. 2019;72(4):1089-1096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Christensen A, Alpert K, Rogalski E, et al. Hippocampal subfield surface deformity in nonsemantic primary progressive aphasia. Alzheimers Dement. 2015;1(1):14-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gabere M, Thu Pham NT, Graff-Radford J, et al. Automated hippocampal subfield volumetric analyses in atypical Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimers Dis. 2020;78(3):927-937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Minoshima S, Frey KA, Koeppe RA, Foster NL, Kuhl DE. A diagnostic approach in Alzheimer's disease using three-dimensional stereotactic surface projections of fluorine-18-FDG PET. J Nucl Med. 1995;36(7):1238-1248. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duffy JR, Strand EA, Clark H, Machulda M, Whitwell JL, Josephs KA. Primary progressive apraxia of speech: clinical features and acoustic and neurologic correlates. Am J Speech Lang Pathol. 2015;24(2):88-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Warrington E, James M. The Visual Object and Space Perception Battery. Thames Valley Test; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Howard D, Patterson K. The Pyramids and Palm Trees Test: A Test of Semantic Access from Words and Pictures. Pearson Assessment; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Machulda MM, Ivnik R, Smith G, et al. Mayo's older Americans normative studies: visual form discrimination and copy trial of the Rey–Osterrieth complex figure. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2007;29(4):377-384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Machulda MM, Whitwell JL, Duffy JR, et al. Identification of an atypical variant of logopenic progressive aphasia. Brain Lang. 2013;127(2):139-144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stricker NH, Christianson TJ, Lundt ES, et al. Mayo normative studies: regression-based normative data for the auditory verbal learning test for ages 30-91 years and the importance of adjusting for sex. J Int Neuropsychological Soc. 2021;27(3):211-226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Avants BB, Epstein CL, Grossman M, Gee JC. Symmetric diffeomorphic image registration with cross-correlation: evaluating automated labeling of elderly and neurodegenerative brain. Med Image Anal. 2008;12(1):26-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jack CR, Wiste HJ, Botha H, et al. The bivariate distribution of amyloid-beta and tau: relationship with established neurocognitive clinical syndromes. Brain. 2019;142(10):3230-3242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mirra SS, Heyman A, McKeel D, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's disease (CERAD): part II: standardization of the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1991;41(4):479-486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Braak H, Alafuzoff I, Arzberger T, Kretzschmar H, Del Tredici K. Staging of Alzheimer disease-associated neurofibrillary pathology using paraffin sections and immunocytochemistry. Acta Neuropathol. 2006;112(4):389-404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Thal DR, Rüb U, Orantes M, Braak H. Phases of Aβ-deposition in the human brain and its relevance for the development of AD. Neurology. 2002;58(12):1791-1800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ellis RJ, Olichney JM, Thal LJ, et al. Cerebral amyloid angiopathy in the brains of patients with Alzheimer's disease: the CERAD experience, part XV. Neurology. 1996;46(6):1592-1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braak H, Del Tredici K, Rüb U, De Vos RA, Jansen Steur EN, Braak E. Staging of brain pathology related to sporadic Parkinson's disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2003;24(2):197-211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hyman BT, Phelps CH, Beach TG, et al. National Institute on Aging–Alzheimer's Association guidelines for the neuropathologic assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Alzheimers Dement. 2012;8(1):1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McKeith IG, Boeve BF, Dickson DW, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: fourth consensus report of the DLB Consortium. Neurology. 2017;89(1):88-100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Murray ME, Graff-Radford NR, Ross OA, Petersen RC, Duara R, Dickson DW. Neuropathologically defined subtypes of Alzheimer's disease with distinct clinical characteristics: a retrospective study. Lancet Neurol. 2011;10(9):785-796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Josephs KA, Murray ME, Whitwell JL, et al. Updated TDP-43 in Alzheimer's disease staging scheme. Acta Neuropathol. 2016;131(4):571-585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rauramaa T, Pikkarainen M, Englund E, et al. Consensus recommendations on pathologic changes in the hippocampus: a postmortem multicenter inter-rater study. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2013;72(6):452-461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Team RC. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (version 3.1. 2). R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Therneau T. A Package for Survival Analysis in R. R Package Version 3.2-3. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Catricalà E, Polito C, Presotto L, et al. Neural correlates of naming errors across different neurodegenerative diseases: a FDG-PET study. Neurology. 2020;95(20):2816-2830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Petroi D, Duffy JR, Borgert A, et al. Neuroanatomical correlates of phonologic errors in logopenic progressive aphasia. Brain Lang. 2020;204:104773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.DeMarco AT, Wilson SM, Rising K, Rapcsak SZ, Beeson PM. Neural substrates of sublexical processing for spelling. Brain Lang. 2017;164:118-128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xing S, Lacey EH, Skipper-Kallal LM, et al. Right hemisphere grey matter structure and language outcomes in chronic left hemisphere stroke. Brain. 2016;139(pt 1):227-241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lemée JM, Bernard F, Ter Minassian A, Menei P. Right hemisphere cognitive functions: from clinical and anatomical bases to brain mapping during awake craniotomy: part II: neuropsychological tasks and brain mapping. World Neurosurg. 2018;118:360-367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ulugut Erkoyun H, Groot C, Heilbron R, et al. A clinical-radiological framework of the right temporal variant of frontotemporal dementia. Brain. 2020;143:2831-2843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chan D, Anderson V, Pijnenburg Y, et al. The clinical profile of right temporal lobe atrophy. Brain. 2009;132(pt 5):1287-1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Josephs KA, Whitwell JL, Knopman DS, et al. Two distinct subtypes of right temporal variant frontotemporal dementia. Neurology. 2009;73(18):1443-1450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mesulam M. Behavioral neuroanatomy: large-scale networks, association cortex, frontal syndromes, the limbic system, and hemispheric specializations. In: Mesulam M, ed. Principles of behavioral and cognitive neurology. Second edition. Oxford University Press; 2000: 1-120. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mesulam MM, Weintraub S, Rogalski EJ, Wieneke C, Geula C, Bigio EH. Asymmetry and heterogeneity of Alzheimer's and frontotemporal pathology in primary progressive aphasia. Brain. 2014;137(pt 4):1176-1192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Eldridge LL, Engel SA, Zeineh MM, Bookheimer SY, Knowlton BJ. A dissociation of encoding and retrieval processes in the human hippocampus. J Neurosci. 2005;25(13):3280-3286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zeineh MM, Engel SA, Thompson PM, Bookheimer SY. Dynamics of the hippocampus during encoding and retrieval of face-name pairs. Science. 2003;299(5606):577-580. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Anonymized data are available from the corresponding author upon request from any qualified investigator for purposes of replicating procedures and results.