1. PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

1.1. Financial inclusion interventions have very small and inconsistent impacts

A wide range of financial inclusion programmes seek to increase poor people's access to financial services to enhance the welfare of poor and low‐income households in low‐ and middle‐income countries. The impacts of financial inclusion interventions are small and variable. Although some services have some positive effects for some people, overall financial inclusion may be no better than comparable alternatives, such as graduation or livelihoods interventions.

1.2. What is this review about?

Financial inclusion programmes seek to increase access to financial services such as credit, savings, insurance and money transfers and so allow poor and low‐income households in low‐ and middle‐income countries to enhance their welfare, grasp opportunities, mitigate shocks, and ultimately escape poverty. This systematic review of reviews assesses the evidence on economic, social, behavioural and gender‐related outcomes from financial inclusion.

What is the aim of this review?

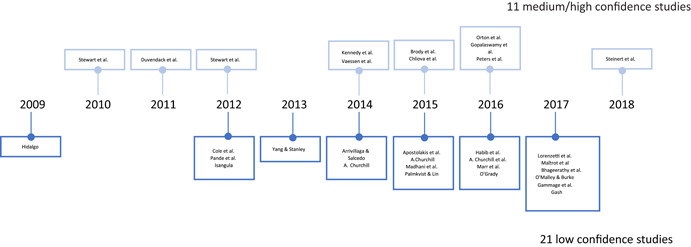

This systematic review of reviews systematically collects and appraises all of the existing meta‐studies—that is systematic reviews and meta‐analyses—of the impact of financial inclusion. The authors first analyse the strength of the methods used in those meta‐studies, then synthesize the findings from those that are of a sufficient quality, and finally, report the implications for policy, programming, practice and further research arising from the evidence. Eleven studies are included in the analysis.

1.3. What are the main findings of this review?

1.3.1. What studies are included?

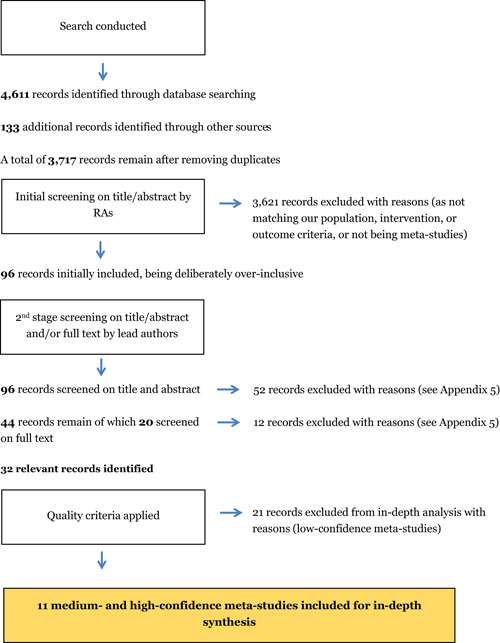

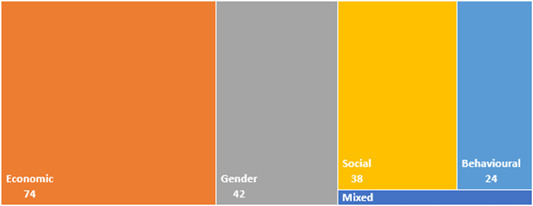

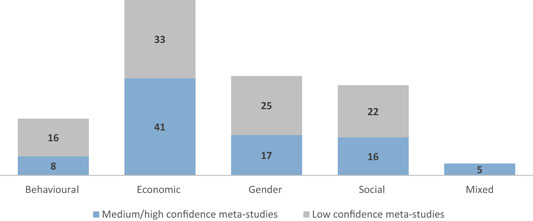

This review includes studies that synthesise the findings of other studies (meta‐studies) regarding the impacts of a range of financial inclusion interventions on economic, social, gender and behavioural outcomes. A total of 32 such meta‐studies were identified, of which 11 were of sufficient methodological quality to be included in the final analysis. The review examined meta‐studies from 2010 onwards that spanned the globe in terms of geographical coverage.

Impacts are more likely to be positive than negative, but the effects vary, are often mixed, and appear not to be transformative in scope or scale, as they largely occur in the early stages of the causal chain of effects. Overall, the effects of financial services on core economic poverty indicators such as incomes, assets or spending, and on health status and other social outcomes, are small and inconsistent. Moreover, there is no evidence for meaningful behaviour‐change outcomes leading to further positive effects.

The effects of financial services on women's empowerment appear to be generally positive, but they depend upon programme features which are often only peripheral or unrelated to the financial service itself (such as education about rights), cultural and geographical context, and what aspects of empowerment are considered.

Accessing savings opportunities appears to have small but much more consistently positive effects for poor people, and bears fewer downside risks for clients than credit. A large number of the meta‐studies included in the final analysis voiced concerns about the low quality of the primary evidence base that formed the basis of their syntheses. This raises concerns about the reliability of the overall findings of meta‐studies.

1.4. What do the findings of this review mean?

This systematic review of reviews draws on the largest‐ever evidence base on financial inclusion impacts. The weak effects found warn against unrealistic hype for financial inclusion, as previously happened for microcredit. There are substantial evidence gaps, notably studies of sufficient duration to measure higher‐level impacts which take time to materialise, and for specific outcomes such as debt levels or indebtedness patterns and the link to macroeconomic development.

This study is the first review of reviews published by the Campbell Collaboration. Some important limitations were encountered working at this level of systematisation. It is recommended that authors of primary studies and meta‐studies engage more critically with study quality and ensure better, more detailed reporting of their concepts, data and methods. More methods guidance and clearer reporting standards for the social science and international development context would be helpful.

1.5. How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies in November 2017, updating elements of the searches in January 2018. This Campbell Systematic Review was published in January 2019.

2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY/ABSTRACT

2.1. Background

Financial inclusion is presently one of the most widely recognised areas of activity in international development. Financial inclusion initiatives have built upon donors’ experience with microfinance, but have displaced and superseded microfinance interventions in recent years with a more encompassing agenda of financial services for poverty alleviation and development. With financial inclusion, policymakers and donors hope that access to financial services (including credit, savings, insurance and money transfers) provided by a variety of financial service providers, of which microfinance institutions (MFIs) are a subset, will allow poor and low‐income households in low‐ and middle‐income countries to enhance their welfare, grasp opportunities, mitigate shocks, and ultimately escape poverty. Another hope is that increased access to financial services will advance macroeconomic development, which is also expected to benefit poor/low‐income households. More recently, some donors have suggested behavioural changes (such as household spending decisions) to be desired outcomes of access to financial services, as well. Unlike most previous systematic reviews, which focused on microfinance interventions (or subsets thereof), we explicitly adopt a broader scope to review any available systematic review and or meta‐analysis evidence on financial inclusion as a whole field.

Systematic reviews and meta‐analyses (in short: meta‐studies) have sought to clarify the impacts from financial inclusion on poor people in low‐ and middle‐income countries, based on an array of different underlying studies which include quantitative and qualitative work based on long‐term and short‐term data. The bulk of these meta‐studies have focused on microfinance, and many specifically on microcredit. The very different quality and approaches of these meta‐studies, and of the studies underlying them, however, pose a major challenge for policymakers, programme managers and practitioners in assessing the benefits and drawbacks of finance‐based approaches to poverty alleviation. Increasingly there is confusion about the impacts, and a risk of “cherry picking” among different findings. Further, many meta‐studies are not taking into account what is missing from their primary studies, which would affect an understanding of the evidence, for example when not analysing or reporting gendered impacts. More recently, primary studies have also sought to understand the impacts of financial inclusion initiatives more broadly, but the systematic review evidence has not yet progressed as far as for microfinance.

2.2. Objectives

The objective of this systematic review of reviews is to systematically collect and appraise the existing meta‐studies of financial inclusion impacts, analyse the strength of the methods used, synthesise the findings from those meta‐studies, and report implications for policy, programming, practice and further research.

Systematic reviews of reviews are undertaken in other sectors for which evidence is widely available, but they are nonexistent in international development. This systematic review of reviews thus provides the opportunity to develop and pilot an evidence synthesis approach in a sector where there is a large body of evidence of variable quality, but a systematic appraisal and synthesis of the body of systematic reviews and meta‐analyses is lacking.

This study critically engages with approaches to systematic reviews of reviews with a view to further developing systematic review of review methods, and it aims to answer the following questions to gain better clarity about financial inclusion impacts:

- Impacts

-

○What is known from existing meta‐studies about the (social, economic and behavioural) poverty impacts of different types of inclusive financial services (e.g., credit, savings, insurance and money transfers), regardless of provider, on poor and low‐income people in low‐ and middle‐income countries? This includes poverty impacts through macroeconomic development, to the extent that it results from financial inclusion.

-

○What is known from existing meta‐studies about the gendered impacts of different types of financial inclusion activity (e.g., credit, savings, insurance and money transfers)—in other words, what does the evidence tell us about how gendered participation affects interventions’ effects, and about whether or not (and in what ways) financial services empower women in low‐ and middle‐income countries?

-

○What is known from existing meta‐studies about the reasons for financial services uptake, or other participant views about the financial services on offer?

-

○

- Methodology

-

○Including using a gender and equity lens, what methods and standards have meta‐studies used to draw conclusions from the studies they reviewed?

-

○What difference does the choice of methods and standards make to the results?

-

○How could the methods and standards be improved in order to draw more robust and reliable conclusions via meta‐studies?

-

○

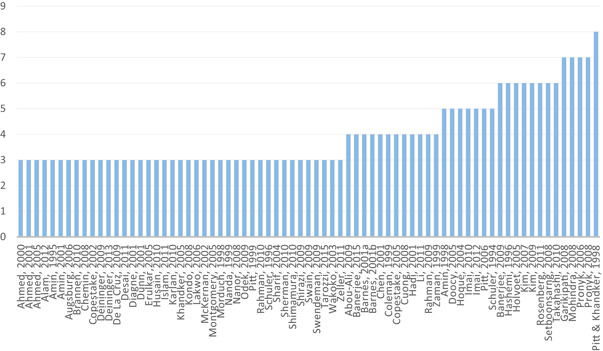

2.3. Search methods

We adopt a multipronged search strategy that explored seven bibliographic databases to identify published literature, plus a wide range of institutional websites for published and unpublished literature, and back‐referencing from recent systematic reviews to ensure additional sources were identified. In addition, a snowballing approach was adopted and an advisory board plus leading authors working on financial inclusion topics were consulted to ensure that no key studies were missed. We also ran citation searches on included systematic reviews and meta‐analyses in Google Scholar, Scopus and Web of Science to identify more recent systematic reviews or meta‐analyses not retrieved in the database searches. No restrictions were placed on the language of papers but all searches were limited to 2010 onwards.

2.4. Selection criteria

We adopted the following selection criteria to establish study inclusion or exclusion:

2.4.1. Types of reviews

We include studies that self‐identify as systematic reviews and or meta‐analyses of the impacts of financial inclusion (including, but not limited to, microfinance). These, in turn, focused on synthesising quantitative, qualitative and or mixed methods evidence.

2.4.2. Types of participants

Our population is the population of participants in inclusive finance activities in low‐ and middle‐income countries.

2.4.3. Types of interventions

We include meta‐studies that address at least one or more types of intervention for financial inclusion. The key is that the intervention must be fundamentally a financial service directed at poor and low‐income people. In most cases, we find the interventions are one or more subcategories of microfinance: credit, savings, insurance, leasing, and/or money transfers. However, our search strategy explicitly targets the broader range of inclusive finance activities, including mobile monies, mobile payments systems, index insurance, or savings promotion.

2.4.4. Types of outcome measures

Meta‐studies capturing a wide range of poverty indicators (including income, assets, expenditure, personal networks, gender/empowerment, well‐being, health, etc.) are included.

All meta‐studies were screened by two research assistants independently, with the two review authors independently reviewing each meta‐study marked for inclusion. Full texts were obtained and screened when a decision could not be made; an arbitration procedure was in place in case of disagreements.

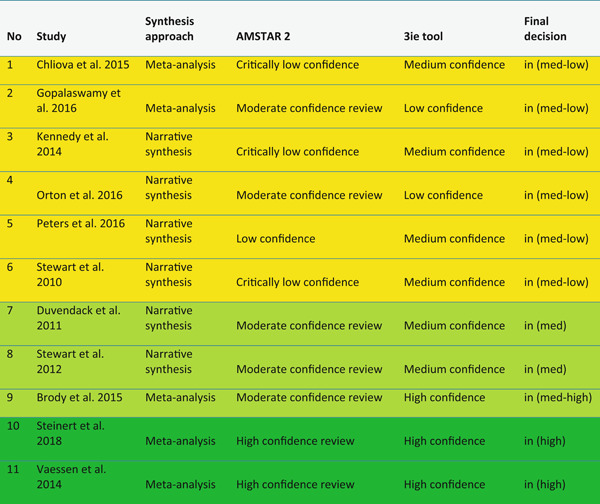

2.5. Data collection and analysis

A total of 32 meta‐studies were identified after completing the screening process. However, only 11 of these were assessed to be of sufficient methodological quality to be included in the final analysis. We note that a large number of these meta‐studies voiced concerns about the low quality of the primary evidence base that formed the basis of their syntheses, which in turn raises concerns about the reliability of the overall findings presented at the review level. Combining a wide range of low quality studies into systematic reviews to aggregate their findings is risky.

A coding tool was developed to extract data from the included meta‐studies on the following areas of interest:

-

1.

Context

-

2.

Type of intervention

-

3.

Type of review, design, and methods used

-

4.

Outcome measures

-

5.

Quality assessment

-

6.

Study results and findings.

Data were extracted at the meta‐study level. However, for meta‐studies classified as high‐ and medium‐confidence, when necessary, we also extracted information at the primary study level.

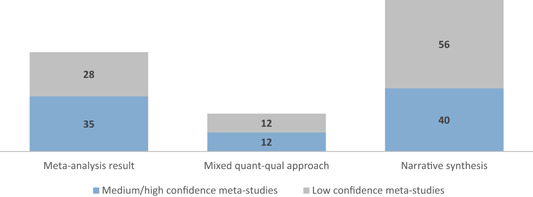

The synthesis of results was guided by a theory‐based mixed methods synthesis approach with a focus on a narrative synthesis that incorporates quantitative elements as appropriate.

2.6. Results

Five out of the 11 (medium‐ and high‐confidence) meta‐studies that we reviewed drew largely positive conclusions about the relationship between financial services access and changes for poor people, and the other six drew largely mixed, neutral, or unclear conclusions. The detailed review of the evidence base uncovered a nuanced picture, reflecting large variations across the effects of different interventions and for different people in different contexts. Findings across the reviews were heterogeneous and often inconsistent, both within and across reviews, and many reviews did not find evidence of expected or presumed impacts.

The present high‐level evidence does not suggest that financial inclusion initiatives have transformative effects. On average, financial services may not even have a meaningful net positive effect on poor or low‐income users, although some services have some positive effects for some people. Overall, we find:

The impacts are more likely to be positive than negative, but the effects vary, are often mixed, and appear not to be transformative in scope or scale, as they largely occur in the early stages of the causal chain.

The effects of financial services on core economic poverty indicators such as incomes, assets or spending are small and inconsistent.

The effects of financial services on women's empowerment appear to be generally positive, but they depend upon programme features (which are often only peripheral or unrelated to the financial service itself, for instance exposure to women's rights), context, and what aspects of empowerment are considered, and their assessment is confounded by a difficulty of consistently conceptualising and measuring empowerment.

The effects of credit and other financial services on health status and other social outcomes appear to be small or nonexistent.

There is no evidence for meaningful behaviour‐change outcomes leading to further positive effects.

Accessing savings opportunities appears to have small but much more consistently positive effects for poor people, and bears fewer downside risks for clients than credit.

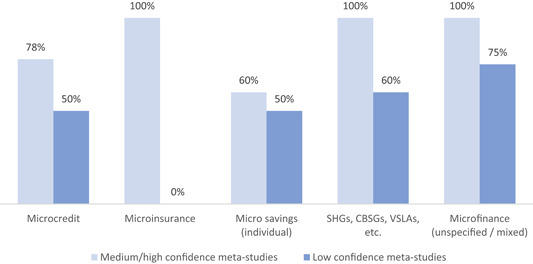

Many of the primary studies that were included in the meta‐studies we analysed in depth had medium or even high risk of bias, due to their study design, poor reporting of methodology, and other causes. As some of the meta‐studies highlighted, it is mainly the higher risk of bias studies that drive most of the positive impact estimates. Our findings thus broadly confirm the “stainless steel” law of evidence that, the more rigorous and lower risk of bias studies become, the less likely they are to find effects. This applies to both our reviews and to the underlying primary evidence that they have reviewed. Given that the reviews we classified as being of lower methodological quality were more likely to report positive effects, we must treat their positive findings with caution.

In summary, almost all effect sizes we find are quite small and hardly indicative of transformative changes from financial inclusion, and are found dominantly on lower‐order or intermediate outcomes. Many effects are strongly heterogeneous, both across studies and over time, places, populations, gender, ethnicity and between interventions; this suggests them to be unreliable and/or context‐dependent. Positive findings tend not to repeat from one context, intervention type or study to another, and at least as many findings are mixed or inconclusive as are positive. As a result, the positive results found for financial inclusion are fragile, and need to be treated with caution. An exception appears to be with regard to savings, where both immediate outcomes and wider poverty measures are affected in a positive, but relatively small, way; however, we base this mainly on the findings of one high confidence meta‐analysis (Steinert et al., 2018). There is no savings “revolution” going on, but savings at least appear to do some good and no harm.

2.7. Authors’ conclusions

We have taken the evolution of the financial inclusion impact literature toward a natural conclusion, with a higher level of evidence systematisation, to provide an overview of what has become an increasingly perplexing array of meta‐studies that each offer partial overviews. By reviewing these reviews, we have drawn on what is likely the largest‐ever evidence base on financial inclusion impacts, and have uncovered strengths, gaps and weaknesses of the existing high‐level evidence. We hope that we have reduced the amount of confusion and uncertainty arising from the many different meta‐studies on financial inclusion published in recent years, not least thanks to our systematic assessment of the variations in quality within that field.

The (perhaps boring) truth that seems to emerge about financial inclusion is that it is not changing the world. On average, financial services may not even have a meaningful net positive effect on poor or low‐income users, although some services have some positive effects for some people. Considering that for most people financial services (whether they can access them, and how they use them) will be only one among many possible determinants of their life chances and their socioeconomic well‐being, this finding ought not to be unexpected, and we anticipate that it will be confirmed by future research. The potential and actual impacts of financial inclusion need to be viewed against those of comparable interventions, such as graduation and livelihoods‐enhancement programmes.

We note that, fortunately, our findings regarding impact chime in with an emerging realism around microfinance, including in the donor community: recognising that erstwhile claims of transformative impact were unrealistic and that the hype for microfinance, particularly microcredit, was overblown. We welcome this newfound realism and wish to encourage it with the help of this review, in which we provide a systematic overview of the evidence as well as the areas of doubt in the evidence base. At the same time, we wished that going through all stages of the hype cycle—enthusiasm, inflated expectations, and disillusionment—had not been necessary in order to arrive here. And we must warn that we see a similar hype of strong claims emerging around the much more encompassing notion of financial inclusion, with the promise of marrying macro‐structural economic improvements with micro‐structural poverty relief. We found no evidence for the wider claims made for the beneficence of financial inclusion, as offering poor people a better service, or as having broader macro‐structural effects, being any truer than those once made for microfinance, in large part due to a lack of appropriate research at the meta‐study level. We strongly caution against repeating the hype cycle, this time around the idea of financial inclusion.

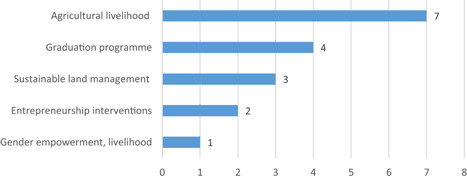

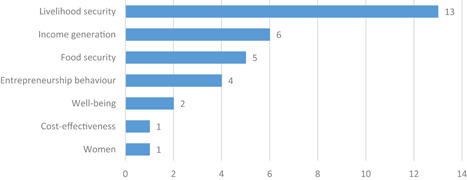

At the same time, we think it crucial to bear in mind that the alternative to financial inclusion is not to do “nothing,” but rather it is necessary to uncover what kinds of interventions work best for whom and where, and how best to deliver them. The policy and research space—and ultimately poor and low‐income people themselves—would benefit from a more open and clear‐sighted discussion on the many valid alternatives to financial inclusion programming and on how best to gain the necessary evidence to inform that discussion. To this end, our review also includes a brief examination of the impact evidence for graduation and livelihoods programmes.

In terms of evidence gaps, it is noteworthy that none of the meta‐studies we reviewed (high‐, medium‐ or low‐confidence) managed to assess debt levels or indebtedness patterns in depth as an outcome of financial inclusion. While we cannot comment on the reasons for the lack of attention paid to the issue, except that we are aware of it also being a blind spot of the underlying primary studies, we find this to be a glaring omission of the financial inclusion literature as a whole. We believe the political economy of research funding needs to shift such that researchers are enabled and encouraged to more rigorously explore the most important potential downsides and risks of development initiatives like financial inclusion. Furthermore, we found no evidence (among the high‐, medium‐ or low‐confidence meta‐studies) for the claim that financial inclusion interventions lead to macroeconomic development and subsequent improvements in the lives of the poor; this may be because the argument has only become prominent in recent years. There is also not much attention given (among the high‐, medium‐ or low‐confidence meta‐studies) to service/amenities‐related programmes such as water credit, sanitation loans, or loans for micro solar systems, especially the notion of “Green Microfinance” where microfinance is applied to promote environmental sustainability.

Moreover, given that the majority of financial inclusion effects we found in assessing the high‐ and medium‐confidence studies were at the early stages of the causal chain, there is a need for studies to better capture long‐term effects and demonstrate more meaningful impacts, especially at the final stages of the causal chain. The vast majority of the studies that our meta‐studies reviewed had a duration of 1–3 years. These studies are likelier to find changes in behaviours or attitudes rather than structural changes to people's poverty status, and it is not safe to assume that the latter will result from the former. The design of most studies underlying the meta‐studies that we reviewed has not been conducive to establishing whether short‐term or immediate outcomes (such as financial knowledge or entrepreneurial propensity) would translate into intermediate outcomes (such as savings accumulation or microenterprise income) and especially more distal, transformative outcomes (higher net worth or higher incomes). We would suggest that this also reflects a problem of the political economy of development research, with a combination of funder restrictions (favouring shorter timelines over multi‐year projects) and difficulty of gaining long‐term support from implementer organisations discouraging appropriate designs.

We have also encountered some important limitations of working at this level of systematisation, including: difficulties of assessing the reliability of the levels of evidence underlying ours; analysing effect sizes that are presented in standardised and indexed form, which often reveal little about the underlying measures used; the different ways in which data have been analysed and findings presented across very different types of meta‐studies; crude categories for intervention and outcome types, lumping together a highly diverse evidence base that muddies the waters further. Another problem we encountered was that the meta‐studies we reviewed, regardless of their own quality, often built on a relatively weak underlying base of underlying studies, making their findings fragile. To put it differently, combining a wide range of low quality studies into systematic reviews to aggregate their findings is risky, and perhaps analogous to the behaviour of financial institutions in the run‐up to the 2008 financial crisis, with pooling dubious individual assets (such as subprime mortgages and loans) into “triple‐A” structured financial products, with only seemingly better aggregate results.

Going forward, we would recommend that authors of primary studies and meta‐studies engage more critically with study quality and ensure better, more detailed reporting of the concepts, data and methods they used. At the systematic review of review level, more methods guidance (especially in terms of synthesis approaches) and clearer reporting standards that adapt the Cochrane (health‐focused) guidance to the social science and international development context would be helpful.

3. BACKGROUND

3.1. The problem, condition or issue

Financial inclusion is presently one of the most widely recognised areas of activity in international development. As of 2017, globally, about 1.7 billion adults were counted as “unbanked”, not having an account at a financial institution or through a mobile money provider, but 515 million adults worldwide opened an account between 2014 and 2017 (Demirgüc‐Kunt, Klapper, Singer, Ansar, & Hess, 2018 p. 2–4). Adults may be “unbanked” for reasons including unaffordability and inaccessibility of financial services, low quality, or choice. Financial inclusion refers to efforts to deliver affordable financial services—transactions, payments, savings, credit and insurance—to these people in a responsible and sustainable way. Financial exclusion is often blamed for inequalities (including in access to economic opportunities), a lack of security, and an exacerbated exposure to risk (Carbo, Gardener, & Molyneux, 2005, p. 5–7). The expectation underlying financial inclusion is that greater access to financial services will create poverty‐alleviating and empowering effects; or, according to the United Nations Secretary‐General's Special Advocate for Inclusive Finance for Development, have the effect of “transforming lives” (UNSGSA, 2017).

With financial inclusion, policymakers and donors hope that access to financial services (including credit, savings, insurance and money transfers) provided by a variety of financial service providers, of which MFIs are a subset, will allow poor and low‐income households in low‐ and middle‐income countries to enhance their welfare, grasp opportunities, mitigate shocks, and ultimately escape poverty, as well as advance macroeconomic development, which is also expected to benefit poor/low‐income households (Beck, Demirgüc‐Kunt, & Levine, 2007; World Bank, 2014). More recently, some donors have suggested behavioural changes (such as household spending decisions) to be desired outcomes of access to financial services, as well (Karlan, Ratan, & Zinman, 2014; World Bank, 2015). However, the present state of evidence leaves it insufficiently clear to what extent and for whom what benefits occur or do not occur (Demirgüc‐Kunt, Klapper, & Singer, 2017; Mader, 2016).

Systematic reviews and meta‐analyses (in short: meta‐studies, we often use the term “reviews” interchangeably with “meta‐studies” in the sections below) have sought to clarify the impacts from financial inclusion on poor people in low‐ and middle‐income countries, based on an array of different underlying studies which include quantitative and qualitative work based on long‐term and short‐term data. The bulk of these meta‐studies have been focused on microfinance, and many specifically on microcredit. The very different quality and approaches of these meta‐studies, and of the studies underlying them, however, pose a major challenge for policymakers, programme managers and practitioners in assessing the benefits and drawbacks of finance‐based approaches to poverty alleviation. Increasingly there is confusion about the impacts and a risk of “cherry picking” among different findings. Further, many meta‐studies are not taking into account what is missing from their primary studies, which would affect the understanding of the evidence, for example by not analysing or reporting gendered impacts. More recently, primary studies1 have also sought to understand the impacts of financial inclusion initiatives more broadly, especially regarding macro‐structural changes (Cull, Ehrbeck, & Holle, 2014; Demirgüç‐Kunt & Klapper, 2013), but the systematic review evidence has not yet progressed as far.

Our primary aim is to gain better clarity about the impacts of financial inclusion on the poor by systematically reviewing the existing systematic reviews and meta‐analyses (meta‐studies). Unlike most previous systematic reviews, which focused on microfinance interventions (or subsets thereof), we explicitly adopt a broader scope to review any available systematic review and or meta‐analysis evidence on financial inclusion as a whole field. Greater clarity through greater evidence systematisation is urgently needed given the strong focus on expanding access to financial services in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), in particular SDG 1 on eradicating poverty2 and SDG 5 on achieving gender equality and women's empowerment,3 and in light of the risks that some forms of financial inclusion pose to vulnerable populations (Guérin, Morvant‐Roux, & Villarreal, 2013). In addition to this primary aim, we have three secondary sub‐objectives

to better inform the decisions of development donors, policymakers and programme managers by establishing what is known and not known about the impacts, using a meta review methodology;

to facilitate better research by assessing the strengths and weaknesses of existing systematic reviews and meta‐analyses, and suggesting pathways toward improved and common standards and methods, particularly with more explicit attention to gendered equity determinants and better use of qualitative studies;

to understand better the political economy of knowledge, which may explain which questions are asked and why, what analysis used and why, and how results are interpreted.

3.2. The intervention

Financial inclusion is an umbrella term, which the World Bank Group defines as follows: “Financial inclusion means that individuals and businesses have access to useful and affordable financial products and services that meet their needs—transactions, payments, savings, credit and insurance—delivered in a responsible and sustainable way.”4

The field of interventions to bring about financial inclusion in low‐ and middle‐income countries is diverse and complex. It encompasses microfinance, as the best‐known intervention in this space, but increasingly extends well beyond it. Microfinance refers to the provision of financial services including loans, savings accounts, insurance (e.g., health, crop, life, credit life or default insurance), and money transfer services, specifically to poor and low‐income people in low‐ and middle‐income countries around the world who are not usually served by the regular banking sector, by dedicated providers who collectively identify as MFIs; these providers may range in size and type from small, local nonprofit NGOs to large commercial microfinance companies. Financial inclusion interventions refer to the range of broader efforts to expand financial systems to deliver financial services—loans, savings, insurance or payment services—to a wider client base, in particular poor and low‐income people in low‐ and middle‐income countries, that has not traditionally been served by the regular banking sector, by any range of formal service providers.5 These service providers commonly include MFIs in addition to commercial banks, nonbank financial companies, credit card companies, government programmes, cooperative banks, village savings and loan associations, some types of self‐help groups (SHGs), and also mobile network operators and fintech companies. In recent years, the delivery of financial services through digital means of service provision has been increasingly emphasised by governments, development funders and service providers themselves (Gabor & Brooks, 2017).

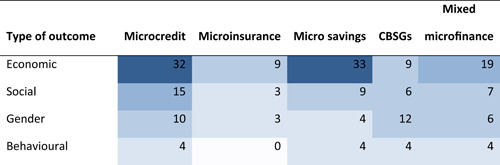

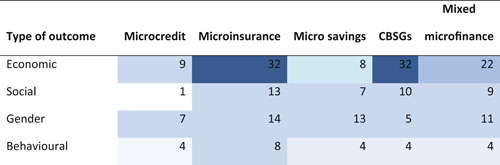

The financial services provided in the financial inclusion space are of four main types: credit, savings, insurance and payment services. The most commonly‐provided services within financial inclusion still are microcredit loans, made to about 211 million families worldwide (Microcredit Summit Campaign, 2015), with durations of around 12 months, which are repaid in weekly (and sometimes bi‐weekly or monthly) instalments, and are often guaranteed by group membership, small collateral items, or personal guarantors. Savings and insurance services are usually offered only in conjunction with loans—mixed (micro‐) finance—, but also sometimes independently. Particularly in South Asia, savings, credit, and other financial services are often delivered through community‐based savings groups (CBSGs), which include SHGs. Money transfers and mobile payments services (i.e., financial technologies, or fintech, that have the potential to disrupt established business models of the inclusive financial space by delivering financial services via digital platforms) are a relatively new area of activity, which is still under development in many countries, but has achieved scale in parts of East Africa and South Asia. In assessing financial inclusion, we thus face a multitude of services, providers, and users. Interventions for financial inclusion include of a diverse set of services orchestrated through various delivery mechanisms, ranging from small‐scale and community‐led initiatives to often very large scale government‐organised, donor‐backed or commercially‐driven programmes. The space of financial inclusion is changing rapidly, and the purpose of this systematic review of reviews6 is to assess evidence for the broader range of inclusive financial services increasingly being offered, as far as possible, including but going beyond (micro‐)credit. Below, in reporting outcomes, we differentiate between (micro‐)credit, (micro‐)savings, (micro‐)insurance, CBSGs and mixed microfinance (where it is unclear exactly which microfinancial services are provided, or where several are provided together).7

It is important to note that, while many financial inclusion services may be delivered separately or bundled by a given provider, in practice, households often combine them in a variety of ways, or even use services for different purposes, for instance using access to credit as a form of insurance. Hence, this renders an intervention‐focused systematic review of reviews artificially narrow, and instead calls for a synthesis of impacts by outcomes, while tracing any effects back to particular interventions or services as much as possible, and this is what we propose to do in this review.

3.3. How the intervention might work

The policy rationale behind financial inclusion activities is that the usage of financial services is expected to improve the lives of poor and low‐income people in low‐ or middle‐income countries (i.e., generate a positive impact). Our systematic review of reviews is theory‐based in the sense that it examines the evidence for and against the correctness of the theory of change underlying financial inclusion programming. The importance of developing and applying a theory of change—to clarify how “the intervention is expected to have its intended impact” (White, 2009, p. 274)—has been increasingly emphasised in recent years in impact evaluations and meta‐studies (cf., Maitrot & Niño‐Zarazúa, 2017). A theory of change serves to explain how activities are expected to produce a series of results that contribute to achieving intended impacts, by schematically explaining the causal links from programme inputs to ultimate (or higher‐order) outcomes. Using a theory of change or “logic model” allows us to link “programme inputs and activities to a chain of intended or observed outcomes, and then [use] this model to guide the evaluation” (Rogers, 2008, p. 30; White, 2009). In other words, the theory of change of financial inclusion should show how financial inclusion initiatives are expected to create desired positive changes for the target population, and thus to aid the interpretation of findings by clarifying differences between programme uptake, immediate effects, and more transformative impacts.

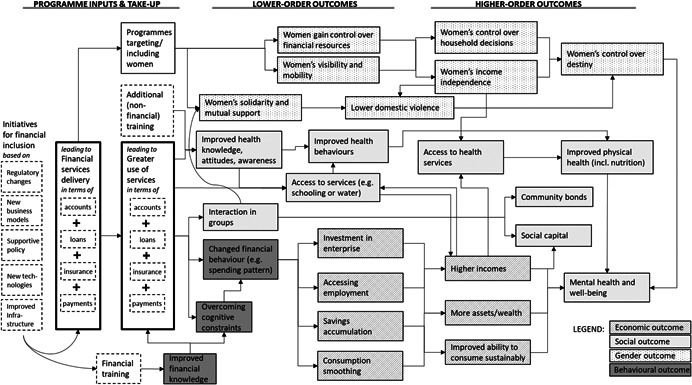

Financial inclusion encompasses a wide range of intervention types and approaches, and numerous different types of intended outcomes and impacts have been suggested as part of its transformative impacts and as intermediary steps leading to them. Given this complexity, our theory of change must necessarily be abstract, simplified, and non‐exhaustive, highlighting main (or exemplary) channels of influence rather than all possible effects (and cross‐linkages between effects) of financial inclusion interventions, Figure 1 highlights the main theorised channels of influence (rather than all possible effects, backward linkages, cross‐linkages, or potential unintended consequences) of financial inclusion interventions, beginning with the possible drivers of enhanced financial service delivery. As shown in the left part of Figure 1, regulatory changes, the emergence of new business models and technologies, supportive policies, and improvements to (financial) infrastructures are expected8 to lead to a more inclusive offering of accounts (including savings accounts), credit, insurance and payments services (as well as financial training), which households in turn access and use (uptake).

Figure 1.

Financial inclusion impacts: Theory of change flow diagram. A macro‐structural outcome category is not shown, because its causal chain does not operate at a household level

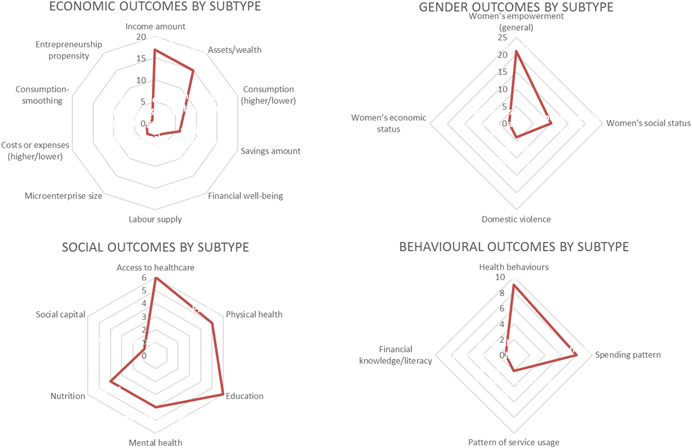

Our representation of the theory of change then proceeds from the recognition that uptake is different within households, and that financial services are fungible within the household, such and that households use and combine them for very different ends (Collins, Morduch, Rutherford, & Ruthven, 2009). Thus, although in reporting findings we seek to distinguish as much as possible between the outcomes from different service types, in developing an encompassing theory of change for financial inclusion, we believe it would be counterproductive to focus on particular impacts as arising only from only particular financial services. We focus on establishing a set of causal chains from households’ uptake (usage of any or several or all of these financial services) to immediate changes (lower‐order outcomes) and from there to more transformative changes (higher‐order outcomes). In doing this, we distinguish between four outcome categories: economic, social, gender, and behavioural (distinguished in Figure 1 by different shading). Notably, these causal chains from financial inclusion to potential impacts of financial services usage on poverty are interdependent, as indicated by the cross‐connections in the figure. Most existing meta‐studies have focussed on individual parts of this broad theory of change, or only certain pathways within them.

3.3.1. Economic

In theory, financial inclusion could lead to benefits for poor people through changes in their financial behaviours such that they use financial services to gain access to new income sources or enhance existing ones, to save money that they would otherwise spend or lose, to invest in assets, to sustainably consume more goods, or to cope with shocks. Specifically, credit might be used to create or expand a business that then makes a profit, or to gain access to a new (other) income‐earning opportunity, such as a job that requires travel. Credit or savings might also be used to mitigate a shock, invest in a household asset, or pay off a more expensive loan. Credit or savings can allow people to accumulate a lump sum for a large investment, cope with shocks, or simply to avoid more expensive credit. Lower‐order outcomes, that is, impacts found on outcomes early in the causal chain, would include the simple fact of having an enterprise (rather than none), increasing the size of one's enterprise, accessing new or better employment, accruing more savings, and having smoother consumption patterns (for instance no periods of hunger). Higher‐order outcomes that occur further along the causal chain (and which these lower‐order outcomes ought to lead to, in order to actually alleviate poverty) would include sustainably higher incomes and more assets or wealth (higher household net worth, net of debts). The ability to consume more goods sustainably (i.e., without over‐spending) is also a higher‐order outcome; however the sustainability of consumption is difficult to ascertain, because changes in consumption levels are might stem from positive causes (such as having more available income) or negative causes (such as higher costs or spending on credit).

3.3.2. Social

Under the heading of “social outcomes” we collect the gamut of other beneficial outcomes that are not strictly behavioural, economic or gender‐related. We break these down further into three broad categories: health (physical health, nutrition, mental and psychological health), social‐relational (strengthening of social ties, community bonds), and access to beneficial services (such as water or schooling). In theory, financial inclusion might affect these in multiple different ways, again with lower‐order outcomes leading to higher‐order outcomes within each category.

Health: Financial services, particularly when accompanied with training or awareness‐raising efforts, might positively affect health knowledge, attitudes or behaviours (lower‐order outcomes), which in turn may lead to improved health outcomes (higher‐order). Increased incomes, savings or spending capacity would also enable people to access to health services by making them more affordable, leading to better health outcomes (as a higher‐order outcome). Increased income independence and improved control over their own destiny for women could improve their health outcomes in particular. Reduced poverty or increased capabilities resulting initially access to financial services could also improve mental health and psychological well‐being (higher‐order).

Social‐relational: In particular with forms of financial service delivery that lead to more regular and positive interaction in groups (lower‐order), clients’ social ties and social capital might be strengthened and community bonds be created (higher‐order). Reduced poverty at an individual level may also improve clients’ social capital, as they rise in the estimation of others (higher‐order).

Services: reduced poverty, which may result from financial inclusion, would make households more able to pay for services such as schooling, water and sanitation (lower‐order outcomes), which in turn would lead to better health and economic outcomes (higher‐order outcomes). Financial products might also be used by clients directly to finance access to particular services or amenities, if they choose to do so; or financial services may be linked to the purchase or use of particular products, as with school savings accounts or sanitation loans. Financial service delivery might also include components of sensitisation, awareness or attitude‐change, to increase clients’ propensity to use (or pay for) particular amenities.

3.3.3. Gender

Financial services may have very different impacts on women and men, particularly if they target women or at least are accessible for women. Many financial inclusion programmes (particularly microfinance and SHGs) have a history of targeting women and aiming to effect women's empowerment; some modes of digital financial services have also been claimed to have positive effects particularly for women by allowing them to save independently, despite not targeting women. In theory, financial services could affect gender relations in a number of complex and interrelated ways, which would be difficult to label as lower‐order or higher‐order.9 Through financial inclusion, women could gain control over financial resources and this may improve their implicit or explicit bargaining position within the household, including on matters such as family planning. Women's control over financial resources could allow them to create or access an independent source of income. As their women's independence improves, domestic violence could reduce. Leaving the home to access financial services or engage in business can make women more visible in the community and give them greater mobility, and women's participation in economic life outside the home may also lead to a broader sense of empowerment and control over destiny, all of which could improve their physical and mental health and well‐being. Furthermore, regular meetings of women could improve women's sense of solidarity and strengthen their mutual support, and some programmes have specific components of solidarity‐building or exposure to women's rights. However, with all these changes, it is important to note that they may contain ambivalences, for instance where women might not want to be more visible (as in some traditional societies) or when newfound independence leads to adverse reactions from men which could mitigate or undermine the benefits.

3.3.4. Behavioural

It has been suggested, particularly by behavioural economists and recently the World Bank,10 that financial services, especially ones that contain particular modalities to affect users’ behaviour, lead to various potentially desirable cognitive capabilities and behavioural changes. In theory, changes in behaviours and cognitive capacities could come from several factors. First, changes in financial knowledge and abilities could come directly from directly being taught in financial literacy or education programmes (which are sometimes attached to financial service delivery, but which on their own we deemed beyond the scope of this review, as not being directly part of financial services and only training for readiness to use the latter) or through experience gained over time in using money and financial services. Financial products might also, as a by‐product of their usage, change users’ money‐usage patterns over time, for instance leading to higher propensities to save, more investment in business, or less spending on particular goods such as “temptation goods” (Banerjee, Duflo, Glennerster, & Kinnan, 2015). It has also been suggested that specially designed financial products could help poor people overcome behavioural or cognitive constraints or attitudes that the designers of these products believe worsen poverty and hold people in poverty, as for instance if “commitment” savings devices commit people to longer‐term goals rather than giving in to possible biases toward present enjoyment. We treat all behavioural outcomes as lower‐order outcomes, because they ought not to be seen as ends in themselves, and merely indicate a potential for poverty‐alleviating effects to happen further along the causal chain.

3.3.5. Macro‐structural

Lastly, in recent years, it has been suggested that inclusive financial sectors are conducive to macroeconomic development, from which poor and low‐income people in turn would benefit (Cull, Demirgüç‐Kunt, & Morduch, 2013; World Bank, 2014). This outcome category is different, as the mechanisms of impact operate at the macro, rather than household, level; we have therefore not included it in Figure 1, which graphically presents the theory of change at the household level (however, our review still aims to capture any evidence on these types of effects). Some economic literature suggests more inclusive financial sector development could drive macroeconomic growth by mobilising savings and investments in the productive sector, and reducing information, contracting and transaction costs across the economy, leading to efficiency gains, which lead to growth; poverty alleviation would result if poor people benefit from subsequent economic growth, for instance through higher demand for their skills. It has also been suggested that financial sector development could reduce economic inequality indirectly (through forms of growth that lower inequality) or through enabling lower‐income individuals to use finance to invest in accumulating human capital (Beck et al., 2007; Jalilian & Kirkpatrick, 2005).

Finally, while this is not part of a theory of change—which serves only to clarify how “the intervention is expected to have its intended impact” (White, 2009, p. 274)—it is important to note that, for all outcome categories, the possibility of unintended negative consequences and adverse effects (on average, or for parts of the population, i.e., mixed impacts) also exists. There is no reason to assume a priori that the impacts of financial inclusion will be positive or significant. Some past evidence has suggested more inclusive financial service provision may also have negative impacts such as worsened impoverishment (Mosley, 2001), financial and emotional stress (Ashta, Khan, & Otto, 2015), debt traps and permanent indebtedness (Guérin et al., 2013; Schicks, 2010), gender‐based violence and women's disempowerment (Rahman, 1999), and undereconomic development and greater social inequality (Bateman, 2010; Sandberg, 2012). Our systematic review of reviews captures and accounts for any findings of negative impacts, including mixed ones.

3.4. Why it is important to do the review

While a large number of methodologically robust studies have systematically synthesised evidence on microfinance, the same cannot yet be said for financial inclusion more broadly. Some donor agencies, especially the World Bank, have carried out primary studies on financial inclusion of various types including microfinance facility to justify why financial inclusion policy matters, how it matters, and what it means to policymaking (cf. Cull et al., 2014; Demirgüç‐Kunt & Klapper, 2013; Demirgüc‐Kunt et al., 2017; World Bank, 2014). But the existing research syntheses on financial inclusion (beyond microfinance) have been unsystematic in their approach.

Polanin, Maynard, and Dell (2017) provide four reasons for why systematic reviews of reviews are important:

-

1.

They can contribute to the knowledge base going beyond what systematic reviews and meta‐analyses report examining trends over time and thus be particularly useful to policymakers, practitioners and researchers.

-

2.

Where many systematic reviews on a given topic exist reporting discordant views, systematic reviews of reviews can be particularly useful to make sense of these diverging conclusions by comparing and contrasting the results of multiple systematic reviews.

-

3.

They have the potential to conduct network meta‐analysis (Ioannidis, 2009) to allow comparisons of multiple treatment and control groups.

-

4.

They can point out when systematic reviews need updating again.

Finally, it is worth noting that systematic reviews of reviews also have a role to play in translating knowledge into policy impact (Whitty, 2015).

In the context of financial inclusion, without robust evidence that financial services generate significant and meaningful—ideally: transformative—impacts in poor people's lives, financial inclusion efforts would lack a clear justification in developmental or social policy terms. This can be said without pre‐judging the evidence. However, the existing meta‐studies (which have focused on microfinance rather than financial inclusion broadly‐defined) have generated few strong or unambiguous results, suggesting that the improvements in poor people's lives that accrue from financial inclusion are relatively small or manifest mainly as intermediary impacts—changes in behaviours and spending patterns, rather than changes in incomes or well‐being—, at least in the shorter term. Presently, too little is known across different meta‐studies with different approaches, and a systematic review of reviews helps generate a clearer picture.

Existing meta‐studies have reviewed primary studies of many different types of financial services. A substantial number of systematic reviews, meta‐analyses and research syntheses on financial inclusion and closely connected topics exist. However, the focus of the bulk of studies (in keeping with the activity focus of the financial inclusion sector) has been on credit and credit‐type (e.g., leasing) services, particularly those provided by MFIs. The evidence based on other services is smaller but growing rapidly, particularly in the area of mobile service provision and fintech for development.

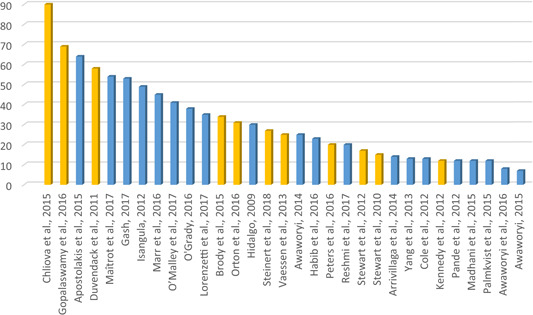

The existing meta‐studies have followed diverse approaches. Some of the systematic reviews (or meta‐studies) are fairly broad, aiming to cover the whole microfinance spectrum (e.g., Duvendack et al., 2011). Others cover specific interventions, such as microcredit (e.g., Vaessen et al., 2014), formal banking services (Pande, Cole, Sivasankaran, Bastian, & Wendel, 2012), microenterprise (e.g., Grimm & Paffhausen, 2015), microsavings and microleasing (Stewart et al., 2012) and microinsurance (Cole, Bastian, Vyas, Wendel, & Stein, 2012). Some systematic reviews focus on particular populations, such as Sub‐Saharan African recipients (e.g., Stewart, van Rooyen, Dickson, Majoro, & de Wet, 2010), particular methods of providing financial services, such as SHGs (e.g., Brody et al., 2015) or particular outcomes, such as health (e.g., Leatherman, Metcalfe, Geissler, & Dunford, 2012) or empowerment (Brody et al., 2015; Vaessen et al., 2014). The systematic reviews also differ by focus, many covering effectiveness evidence, but others incorporating participant views (e.g., Brody et al., 2015; Peters, Lockwood, Munn, Moola, & Mishra, 2016) and barriers or enablers of uptake and effectiveness (e.g., Panda et al., 2016) including innovations in information and communications technology (e.g., Gurman, Rubin, & Roess, 2012; Jennings & Gagliardi, 2013; Lee et al., 2016; Sondaal et al., 2015).

The existing meta‐studies use a range of methodologies to synthesise the evidence, including theory‐based approaches, narrative syntheses and statistical meta‐analyses. Many of them have not been conducted to standards that would support a “high confidence” rating (as discussed below in the Section 5); not all meta‐studies that have impacted policy discussions have used a systematic methodology (Bauchet, Marshall, Starita, Thomas, & Yalouris, 2011; Beck, 2015; Odell, 2010). In addition, the majority of meta‐studies are available in technical reports where there is no transparent decision rule for determining implications of the findings, including critical appraisal and strength of evidence tools like GRADE assessment (Guyatt et al., 2013) and user‐friendly presentation of results (e.g., translating standardised effect sizes into metrics commonly used by decision makers). There is no overall synthesis of the implications for policy, programming, practice and research for the sector from this body of synthesised evidence.

Our systematic review of reviews brings a systematic overview about what is known about what aspects of financial inclusion (what, where, how?) and which gaps and white spaces remain in terms of knowledge about the impacts. Rather than visualise these gaps and white spaces, we describe them narratively, focusing on a range of parameters (e.g., intervention type, outcome measures, geographical focus, etc.), which in turn inform our synthesis approach which, among other things, also focuses on the following unresolved questions (discussed in more depth in the section outlining our approach to data synthesis):

What can explain which questions are asked in some systematic reviews and meta‐studies about the impact of financial inclusion, and which ones not?

What can explain different interpretations of results from existing studies?

A clear mapping of knowledge gaps allows policy‐oriented research funders to better direct funds towards addressing the gaps, and the systematic reviewing of known impacts allows policymakers to focus their efforts on those interventions that are known to work best, on where they work best, or to improve or otherwise eschew them. Our stakeholder engagement strategy includes a non‐technical report (for 3ie), dissemination events, and work with our advisory board of policy‐ and research‐related stakeholders.

4. OBJECTIVES

4.1. The problem, condition or issue

The objective of this systematic review of reviews is to systematically collect and appraise the existing systematic reviews and meta‐analyses of financial inclusion impacts, analyse the strength of the methods used, synthesise the findings from those systematic reviews and meta‐analyses, and report implications for policy, programming, practice and further research.

Systematic reviews of reviews have been undertaken in other sectors for which evidence is widely available, especially health (Becker & Oxman, 2008) and more recently education (Polanin et al., 2017), but they are nonexistent in international development, and thus this study represents a pioneering effort to address a notable evidence gap.11 It provides the opportunity to develop and pilot an evidence synthesis approach in a sector where there is a large body of evidence of variable quality, but systematic appraisal and synthesis of the body of systematic reviews and meta‐analyses is still lacking. Polanin et al. (2017) provide useful guidance on how best to conduct such systematic reviews of reviews; they point towards methodological challenges of such reviews and suggest ways forward to improving them.

This study critically reviews existing approaches to systematic reviews of reviews with a view to further developing systematic review of review methods, and it aims to answer the following questions to gain better clarity about financial inclusion impacts:

- Impacts

-

○What is known from existing meta‐studies about the (social, economic, and behavioural) poverty impacts of different types of inclusive financial services (e.g., credit, savings, insurance and money transfers), regardless of provider, on poor and low‐income people in low‐ and middle‐income countries?12 This includes the poverty impacts from macroeconomic development, to the extent that it results from financial inclusion.13

-

○What is known from existing meta‐studies about the gendered impacts of different types of financial inclusion activity (e.g., credit, savings, insurance and money transfers)—in other words, what does the evidence tell us about how gendered participation affects interventions’ effects, and about whether or not (and in what ways) financial services empower women in low‐ and middle‐income countries?

-

○What is known from existing meta‐studies about the reasons for financial services uptake, or other participant views about the financial services on offer?

-

○

- Methodology

-

○Including using a gender and equity lens, what methods and standards have meta‐studies used to draw conclusions from the studies they reviewed?

-

○What difference does the choice of methods and standards make to the results?

-

○How could the methods and standards be improved in order to draw more robust and reliable conclusions via meta‐studies?

-

○

5. METHODS

5.1. Criteria for considering studies for this review14

5.1.1. Types of reviews

We sought to include all studies of sufficient quality (we discuss our understanding of “sufficient quality” in Section 5.3.3. as outlined in Table 2 but also in Appendix 7) which self‐identified as systematic reviews and or meta‐analyses of the impacts of financial inclusion (including, but not limited to, microfinance). These, in turn, have focused on synthesising quantitative, qualitative and or mixed methods evidence. According to the Campbell Collaboration,

A systematic review summarises the best available evidence on a specific question using transparent procedures to locate, evaluate, and integrate the findings of relevant research (The Campbell Collaboration, 2014, p. 6).

Table 2.

Overview of the critical appraisal tools’ main quality assessment criteriaPossible result classes

| 3ie critical appraisal checklist | A MeaSurement Tools to Assess systematic Reviews (AMSTAR 2) |

|---|---|

| • Inclusion criteria reported | • Research questions and inclusion criteria reported with PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparator, Outcome) |

| • Reasonably comprehensive search strategy | • Review methods established prior to review; deviations from protocol reported |

| • Appropriate review time period | • Selection of included study designs explained |

| • Bias in selection of articles avoided | • Comprehensive literature search strategy used |

| • Characteristics and results of included studies reliably reported | • Study selection performed in duplicate |

| • Clear methods of analysis, including for calculating effect sizes | • Excluded studies listed and justified |

| • Extent of heterogeneity discussed | • Included studies described in adequate detail |

| • Findings of relevant studies appropriately combined relative to the question and available data | • Satisfactory technique used for assessing risk of bias |

| • Evidence appropriately reported | • Sources of funding of the included studies reported |

| • Assessment of factors explaining differences in results | • If meta‐analysis: appropriate methods used for statistical combination of results |

| • Consideration of aspects that may lead to questionable results | • If meta‐analysis: impact of risk of bias considered |

| • Consideration of mitigating factors for reliability | • Consideration of mitigating factors for reliability |

| • Use of programme theory of change a | • Risk of bias considered in interpretation and discussion of results |

| • Qualitative evidence incorporated in theory design a | • Heterogeneity discussed and explained |

| • Outcomes analysed along causal chain a | • If quantitative synthesis: publication bias considered |

| • Qualitative evidence incorporated in analysis a | • Conflicts of interest and funding for the review reported |

| • Qualitative evidence incorporated in other aspects a | |

| • Findings from quantitative and qualitative evidence integrated a | |

| • Quantitative and qualitative evidence integrated in conclusions and implications a | |

| Possible result classes: | |

| Low confidence | Critically low quality |

| Medium confidence | Low quality |

| High confidence | Moderate quality |

| High quality |

Criteria to capture use of theory and causal chain analysis, added after discussions with 3ie. See Appendix 7 for full versions of both quality appraisal tools.

In the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins & Green 2011), the following definition of systematic reviews is outlined which we adopted:

A systematic review attempts to collate all empirical evidence that fits pre‐specified eligibility criteria in order to answer a specific research question. It uses explicit, systematic methods that are selected with a view to minimising bias, thus providing more reliable findings from which conclusions can be drawn and decisions made (Section 1.2 in Higgins & Green, 2011).

Higgins and Green (+++2011) specify the key elements that a systematic review should contain:

A set of clearly stated objectives and pre‐defined eligibility criteria

A methodology that is clearly defined allowing reproducibility

A search strategy that allows the identification of studies meeting the pre‐defined eligibility criteria

A critical appraisal of included studies

A systematic synthesis, in many cases systematic reviews adopt a meta‐analytical approach which is a statistical method to synthesise the results of primary studies included in a systematic review

To identify meta‐analyses, we adopted the definition of the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins & Green, 2011):

“Meta‐analysis [is] the statistical combination of results from two or more separate studies” to produce an overall statistic with the aim to provide a precise estimate of the effects of an intervention (Section 9.1.2 in Higgins & Green, 2011).

It should be noted that not every systematic review automatically contains a meta‐analysis, for example, if primary studies are too heterogeneous in terms of study designs, conceptual framings and or outcomes, then a meta‐analysis may not be appropriate. Furthermore, occasionally meta‐analyses are published separately without drawing on the broader systematic review they may have been originated from.

We exclude any evidence that did not meet the definitions we outlined above.

5.1.2. Types of participants

The scopes of the meta‐studies we include are diverse (different questions are often addressed and a range of linked interventions are examined, such as credit, savings, insurance, leasing, money transfers etc.) but there is considerable overlap in terms of their population of interest. Almost all focus on the impacts of financial inclusion on poor households based in low‐ or middle‐income countries (using the World Bank definition15). In other words, our population is the population of participants in inclusive finance activities that are conducted in low‐ and middle‐income countries. Where meta‐studies include evidence from high‐income countries, we would have only considered the findings that were presented for low‐ and middle‐income countries, but we did not find any such studies to include. We also included meta‐studies covering particular regions within low‐ and middle‐income countries, for example, Sub‐Saharan Africa or fragile and conflict‐affected areas.

At the primary study level, our population of interest would be participants taking part in inclusive finance activities in low‐ and middle‐income countries.

5.1.3. Types of interventions

In this systematic review of reviews, we include all meta‐studies that address at least one or more types of intervention for financial inclusion, as described above. In the majority, the interventions are one or more sub‐categories of microfinance: credit, savings, insurance, leasing, and/or money transfers. However, our search strategy explicitly targets the broader range of inclusive finance activities, such as mobile monies, mobile payments systems, index insurance or savings promotion. For our purposes, to warrant inclusion of the systematic review or meta‐analysis, the reviewed intervention must have at least one financial service as an essential element of the intervention—for instance, not all systematic reviews of mhealth interventions would qualify for inclusion, but systematic reviews of mhealth interventions that required participants to purchase an insurance service would. The key is that the reviewed intervention must be fundamentally a financial service directed at poor and low‐income people, for it to qualify as a review of financial inclusion impacts.

At the primary study level, our intervention of interest would be interventions that address at least one or more types of financial inclusion interventions.

5.1.4. Types of outcome measures

Existing meta‐studies of financial inclusion typically examine a wide range of poverty indicators (including income, assets, expenditure, personal networks, gender/empowerment, well‐being, health, etc.). In this systematic review of reviews, we include all meta‐studies that address at least one or more of these domains. We group the indicators in three categories of impacts: social, economic, or behavioural. We do not distinguish between primary or secondary outcomes but consider all outcome measures.

Our systematic review of reviews also assesses the evidence for outcomes early along the causal chain; most importantly rates of uptake, and then investment in productive activity, human capital accumulation, improved money management, savings accumulation, risk/shock management, health and nutrition spending, and women's economic activity. These might be enablers of improvements on poverty indicators further along the causal chain (over a longer term) even if, importantly, should not themselves be taken as evidence of impact in terms of poverty alleviation.

At the primary study level, our outcomes of interest would be outcomes that address at least one or more of the poverty domains described above.

5.1.5. Timeframe

The first systematic reviews engaging with financial inclusion issues (Duvendack et al., 2011; Stewart et al., 2010) indicated that no systematic reviews existed prior to their reviews. The primary studies these two systematic reviews included date back to the late 1990s reporting on data that was collected in the early 1990s—this coincides with rigorous impact evaluations of financial inclusion (especially microfinance) becoming more mainstream. Hence, our searches are limited to 2010 onwards. However, to ensure that we are not excluding any relevant studies on date, we adopted a snowballing approach (as outlined below). In other words, any relevant meta‐studies published before 2010 would have been picked up through the snowballing procedure.

5.1.6. Language

No restriction was placed on language of papers.

We did not need to make any changes to the eligibility criteria set out in this section during the course of the search and screening process (relates to MECIR checklist, item 13).

Evidence is included irrespective of its publication status (relates to MECIR checklist, item 12).

5.2. Search methods for identification of studies

We adopted a multi‐pronged search strategy which was informed by Kugley et al. (2016) and that explores bibliographic databases to identify published literature, institutional websites for published and unpublished literature, and back‐referencing from recent systematic reviews to ensure additional sources are identified.

5.2.1. Electronic searches

We searched the following bibliographic databases:

Business Source Premier (EBSCO)

Academic Search Complete (EBSCO)

EconLit—Via EBSCO Discovery Service

RePEc—Via EBSCO Discovery Service

World Bank e‐Library—Via EBSCO Discovery Service

Scopus (Elsevier)

Web of Science

5.2.2. Searching other resources

The following institutional websites were searched:

Financial inclusion‐specific institutions and web portals:

CGAP: www.cgap.org

Microbanking Bulletin: www.themix.org

Microfinance Gateway: www.microfinancegateway.org

Microfinance Network: www.mfnetwork.org

Grameen Foundation

BRAC Research and Evaluation Division

Alliance for Financial Inclusion

Accion Centre for Financial Inclusion.

Multilateral and bilateral and non‐governmental donor organisations:

World Bank (WB e‐library was searched within EBSCO's Discovery Service but will also be searched and screened online via the World Bank's website)

African Development Bank

Asian Development Bank

Inter‐American Development Bank

DFID—R4D website

USAID.

Research institutions and research networks:

Centre for Global Development

J‐PAL

3ie databases on systematic reviews

ELDIS

SSRN

ResearchGate

Academia.edu

After completing the screening process, we ran citation searches on included meta‐studies in Google Scholar, Scopus and Web of Science to identify more recent systematic reviews and or meta‐analyses not retrieved in database searches.

We piloted our key search terms (see Appendix 1 for full search strategies) and ran preliminary searches in EconLit (EBSCO) (510 hits), Scopus (1035 hits), RePEc (EBSCO) (238 hits), Academic Search Complete (EBSCO) (366 hits), and Web of Science (2014 hits). Search strategies were constructed using both textwords (title/abstracts) and where available index terms. Each strategy consisted of 3 parts—Intervention (financial inclusion, microfinance and other relevant terms), Study design (adapted from 3ie's search filter for its systematic review database), and LMICs (adapted from the Cochrane EPOC Group's LMICs filter based on World Bank definition of LMICs). We adjusted our search strategy for each database and web source. No restriction was placed on language of papers but all searches were limited to 2010 onwards (rationale provided above). We adopted a snowballing (also called reference harvesting) approach to ensure we have not missed any key systematic reviews and or meta‐analyses. We also consulted our advisory board to get their views on the sample of included studies and highlight any omissions. We ensured that our searches for all relevant databases were up to date, that is, they were updated within 12 months before publication of our study. In addition, we approached leading authors working on financial inclusion topics to double check that we are not missing out on any relevant ongoing studies.

5.3. Data collection and analysis

5.3.1. Selection of studies

Two research assistants (RAs) screened all titles and abstracts of the studies identified by the academic and grey literature searches. Any disagreements were discussed and reconciled. The two review authors (MD and PM) independently reviewed each meta‐study marked for inclusion by the RAs to confirm the inclusion decision. Full texts were obtained and screened when a decision could not be made based on title and abstract screening. Disagreements were resolved by discussion or by involving a third party (e.g., a member of the advisory board) if a consensus could not be reached.

A PRISMA flow diagram is presented in the results section (below) to summarise the study selection process and a table with excluded studies along with the reasons for exclusion is included in Appendix 5—see results section for more in depth discussions.

5.3.2. Data extraction and management

Data were extracted by three RAs using the KoBo Toolbox16 which allowed conversion to an Excel spreadsheet. The extracted data were independently checked by the two review authors (MD, PM). In case of disagreements, they were resolved by discussion. The original authors of included systematic reviews and meta‐analyses were contacted where data were missing.

We extracted data on the following areas (for details see Table 1 below which was informed by Snilstveit et al., 2014):

-

1.

Context

-

2.

Type of intervention

-

3.

Type of review, design and methods used

-

4.

Outcome measures

-

5.

Quality assessment

-

6.

Study results and findings

Table 1.

Data extraction form (template)

| Data extraction items | Details |

|---|---|

| 1. Context | • Source |

| • Author | |

| • Publication year | |

| • Geographical focus (e.g., continent, countries and regions) | |

| • Funding source | |

| 2. Type of intervention | • Details of the population as discussed in the reviews (e.g., household, individual, enterprise; type of finance user, i.e., multiple borrower/saver, repeat borrower/saver; gender or other person characteristics, e.g., women focus or youth focus) |

| • Broad category—type of product/service offered, ensure intervention has at least one essential financial service element | |

| • Detailed sub‐category of product (e.g., credit to existing businesses only, group savings account, etc.) | |

| • Comparator, i.e., comparing against nothing at all or against the next best alternative | |

| • Duration of intervention (e.g., length of exposure to intervention) | |

| • Modality of intervention—group vs individualLocation of intervention—urban/rural | |

| • Focus on women only (yes/no) | |

| 3. Type of review; design and methods | • Research question and review objectives—list actual question, plus clearly stated (yes/no) |

| • Inclusion criteria—clearly stated (yes/no) | |

| • Search methods—e.g., number of databases, dates of search provided, search strategy/key words provided, additional search methods reported, any search restrictions (by language, timeframe?) | |

| • Study selection methods—clearly reported (yes/no), independent screening, full text review, consensus procedure for agreements | |

| • Number of included studies | |

| • Types of included studies | |

| • Types of data extraction methods—clearly reported (yes/no), independent screening | |

| • Types of data synthesis approaches (quantitative/qualitative) | |

| • Subgroup analysis conducted (yes/no) | |

| • Discussion of publication bias (yes/no) | |

| 4. Outcome measures | • Outcome definition, i.e., type of outcome measure to be grouped by social, economic, behavioural |

| • Unit of measurement (e.g., at household or individual level, composition of empowerment indices) | |

| 5. Quality assessment | • Quality of review methods, their use and application—to be assessed using data extracted as part of “3. Type of review; design and methods” which will feed into AMSTAR rating |

| • GRADE rating provided (yes/no) | |

| • Name of other quality assessment tools and their quality scores | |

| • Researcher bias/Conflict of interest | |

| 6. Study results and findings | • For each outcome: |

| ○ Sample size | |

| ○ Type of effect size | |

| ○ Magnitude and direction of effect size, if reported, to allow comparison across included studies |

We extracted the most detailed data (also numerical data if it was available) to allow similar analyses of included studies.

We extracted information at the systematic review level. However, for systematic reviews classified as high and medium confidence, when necessary, we also extracted information at the primary study level on, for example, especially individual programme design, quality, and so forth.

5.3.2.1. Criteria for determination of independent reviews (see MECIR checklist, items 40 and 42)