1. PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

1.1. Individualized funding has positive effects on health and social care outcomes

Individualized funding provides personal budgets for people with disabilities, to increase independence and quality of life. The approach has consistently positive effects on overall satisfaction, with some evidence also of improvements in quality of life and sense of security. There may also be fewer adverse effects. Despite implementation challenges, recipients generally prefer this intervention to traditional supports.

1.2. What is this review about?

Individualized funding is an umbrella term for disability supports funded on an individual basis. It aims to facilitate self‐direction, empowerment, independence and self‐determination. This review examines the effects and experiences of individualized funding.

What is the aim of this review?

This Campbell systematic review examines the effects of individualized funding on a range of health and social care outcomes. It also presents evidence on the experiences of people with a disability, their paid and unpaid supports and implementation successes and challenges from the perspective of both funding and support organizations.

1.3. What are the main findings of this review?

1.3.1. What studies are included?

This study is a review of 73 studies of individualized funding for people with disabilities. These include four quantitative studies, 66 qualitative and three based on a mixed‐methods design. The data refer to a 24‐year period from 1992 to 2016, with data for 14,000 people. Studies were carried out in Europe, the US, Canada and Australia.

Overall, the evidence suggests positive effects of individualized funding with respect to quality of life, client satisfaction and safety. There may also be fewer adverse effects. There is less evidence of impact for physical functioning, unmet need and cost effectiveness. The review finds no differences between approaches for the Adult Social Care Outcomes Toolkit (ASCOT), self‐perceived health and community participation.

Recipients particularly value: flexibility, improved self‐image and self‐belief; more value for money; community integration; freedom to choose ‘who supports you; ‘social opportunities’; and needs‐led support. Many people chose individualized funding due to previous negative experiences of traditional, segregated, group‐orientated supports.

Successful implementation is supported by strong, trusting and collaborative relationships in their support network with both paid and unpaid individuals. This facilitates processes such as information sourcing, staff recruitment, network building and support with administrative and management tasks. These relationships are strengthened by financial recognition for family and friends, appropriate rates of pay, a shift in power from agencies to the individual or avoidance of paternalistic behaviour.

Challenges include long delays in accessing and receiving funds, which are compounded by overly complex and bureaucratic processes. There can be a general lack of clarity (e.g., allowable budget use) and inconsistent approaches to delivery as well as unmet information needs. Hidden costs or administrative charges can be a source of considerable concern and stress.

Staff mention involvement of local support organizations, availability of a support network for the person with a disability and timely relevant training as factors supporting implementation. Staff also highlight logistical challenges in support needs in an individualized way including, for example, responding to individual expectations and socio‐demographic differences.

1.4. What do the findings of this review mean?

This review provides an up‐to‐date and in‐depth synthesis of the available evidence over 25 years. It shows that there are benefits of the individualized funding model. This finding suggests that practitioners and funders should consider moving away from skepticism, towards opportunity and enthusiasm. Policy makers need to be aware of the set‐up and transitionary costs involved. Investment in education and training will facilitate deeper understanding of individualized funding and the mechanisms for successful implementation.

Future studies should incorporate longer follow‐ups at multiple points over a longer period. The authors of the review encourage mixed‐methods approaches in further systematic reviews in the field of health and social care, to provide a more holistic assessment of the effectiveness and impact of complex ‘real‐world’ interventions.

1.5. How up‐to‐date is this review?

The review authors searched for studies up to the end of 2016. This Campbell systematic review was published in January 2019.

2. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY/ABSTRACT

2.1. Background

The World Health Organisation estimates that 15% of the world's population live with a disability and that this number will continue to grow into the future, but with the attendant challenge of increasing unmet need due to poor access to health and social care (WHO, 2013). Historically, the types of supports available to people with a disability were based on medical needs only. More recently, however, the importance of social care needs, such as keeping active and socializing, has been recognized (Malley et al., 2012). There is now an international policy imperative for people with a disability to live autonomous, self‐determined lives whereby they are empowered and as independent as possible, choosing their supports and self‐directing their lives (Perreault & Vallerand, 2007; Saebu, Sørensen, & Halvari, 2013).

One way to achieve self‐determination is by means of a personal budget (United Nations, 2006). Personal budgets are just one example of many terms used to describe individualized funding – a mechanism to provide personalized and self‐directed supports for people with a disability, which places them at the center of decision‐making around how and when they are supported (Carr, 2010). Individualized funding –which is rooted in the Independent Living Movement (Glasby & Littlechild, 2009)– has evolved to take many forms. These include, for example, direct‐payments, whereby funds are given directly to the person with a disability who then self‐manages this money to meet their individual needs, capabilities, life circumstances and aspirations (Áiseanna Tacaíochta, 2014a). Alternatively, a microboard, brokerage model, or ‘managed’ personal budget provide a similar amount of freedom for the person with a disability, but an intermediary service assumes responsibility for administrative tasks, while sometimes also providing support, guidance and information to enable the person to successfully plan, arrange and manage their supports or care plans (Carr, 2010). Other types of models also exist, largely guided by country‐specific contexts, such as social benefits systems.

2.1.1. The intervention

For the purposes of this review, the intervention included any form of individualized funding regardless of the name given, provided it met the following criteria: (a) it must be provided by the state as financial support for people with a lifelong physical, sensory, intellectual, developmental disability or mental health problem; (b) the recipient must be able to freely choose how this money is spent in order to meet their individual needs; (c) the individual can avail of ‘intermediary’ services or any equivalent service which supports them in terms of planning and managing how the money is used over the lifetime of the funding period; (d) the recipient can also independently manage the individualized fund, in whatever way is feasible; and (e) the individualized fund may be provided as a ‘once‐off’ pilot intervention for a defined period of time (minimum 6 months), or it can be a permanent move from more traditional forms of funding arrangements that exist nationally or regionally.

Commentators have indicated that strategic and policy decisions appear to be evolving on the basis of locally sourced or anecdotal evidence, due mainly to a lack of high quality experimental studies in the area (Harkes, Brown, & Horsburgh, 2014; Webber, Treacy, Carr, Clark, & Parker, 2014). While previous literature reviews exist (Carter Anand et al., 2012; Webber et al., 2014), we are not aware of any systematic review that focuses on the effectiveness of individualized funding in relation to people with a disability of any kind. Given the new policy imperative around individualized funding and the growing pool of studies in this area, there is now a need for a systematic review of these models across a spectrum of disabilities, in order to assess their effectiveness in relation to health and social care outcomes.

2.2. Objectives

The objectives of this review are to: (a) examine the effectiveness of individualized funding interventions for adults with a lifelong disability (physical, sensory, intellectual, developmental or mental disorder), in terms of improvements in their health and social care outcomes when compared to a control group in receipt of funding from more traditional sources; and (b) to critically appraise and synthesise the qualitative evidence relating to stakeholder perspectives and experiences of individualized funding, with a particular focus on the stage of ‘initial implementation’ as described by Fixsen, Naoom, Blase, Friedman, and Wallace (2005).

2.3. Search methods

In line with the study protocol (Fleming, Furlong, et al., 2016), ten academic databases and nine other grey literature databases/search engines were utilized. The terms used to customize the search string for specific databases were based on the ‘population’ and ‘intervention’ of interest. ‘Disability’ and all possible variations including mental health, disorders and autism was the first keyword. ‘Budget’ and all variations of same was the second keyword. Database specific conventions were followed to ‘explode’ or ‘truncate’ key terms as appropriate. A list of free‐text terms which were identified in the literature supplemented the syntax developed. Study design and outcomes were not included as part of the search strategy as it was anticipated that this would potentially lead to the omission of relevant literature. Bibliographies from included and some excluded studies (e.g., literature reviews) were used to guide forward citation searching. Conference proceedings, manual browsing of key journals and other online materials guided hand‐searching.

2.4. Selection criteria

The population of interest included: adults aged 18 years and over receiving a personal budget, with any form or level of lifelong disability (physical, sensory, intellectual or developmental disability, level of mental health problem, disorder or illness, or dementia), residing in any country and any type of residential setting (own home, group home, residential care setting, nursing home, hospital, institution). Studies in any language were included.

Minors and older people without a lifelong disability (i.e., no disability in 10 years prior to reaching the age of 65) were excluded, as were privately funded individualized funding interventions.

2.5. Data collection and analysis

Due to the very large search results (n = 82,274 after duplicates and non‐relevant grey literature excluded), an extensive, thorough and transparent ‘results refinement process’ was developed in order to filter these results. Following this refinement process, a screening of studies, based on the inclusion/exclusion criteria, was undertaken in two stages. The first stage involved title and abstract screening; the second involved full text documents. Three independent researchers were involved at each stage. Risk of bias and quality of research was evaluated using a range of tools (depending on study design) by one reviewer (PF). Further quality screening took place, during full text screening, by two second reviewers (MH & SOD).

A very high level of irregularity was observed across studies making them unamenable to metasynthesis, mainly based on the use of inconsistent, unstandardized, and often invalidated outcome measures as well as the selection of control groups. With regard to the latter, some control group participants were randomly assigned, some did not wish to leave traditional services, whilst others were on a waiting list to avail of individualized funding. Furthermore, the study designs were heavily influenced by country‐specific, and changing economic and policy landscapes. Therefore, a narrative analysis of quantitative data was considered the approach which would best represent the results. Narrative systematic reviews serve several functions including reporting the effects of interventions and also the factors impacting their implementation (Popay et al., 2006). A meta‐synthesis of qualitative data was undertaken to build upon the latter point, based on the experiences of intervention participants, in addition to outlining the key facilitators and challenges associated with implementation, from the perspective of multiple stakeholders. Key themes were identified, which were conceptually folded together across studies.

2.6. Results

Of the 82,274 potentially relevant titles originally identified, 7,158 were independently double screened based on ‘title / abstract’ and a subsequent 328 full‐text articles were doubled screened. In total, 73 studies met the inclusion criteria and were included in the review, 66 (90%) of which were qualitative in nature.

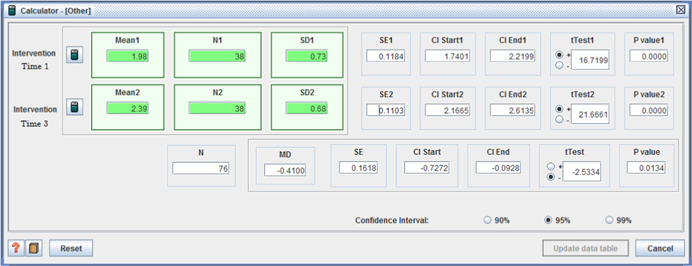

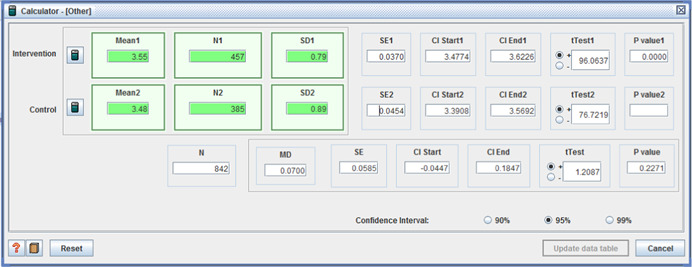

2.6.1. Quantitative

Seven unique studies contained eligible quantitative data (including three mixed methods) and were included in the review, representing 19 titles in total. One of the studies was an unpublished report (available online), while the remaining six were reported in both unpublished reports and published peer‐reviewed journal articles. All studies were English language and the majority were based in the United States (n = 5). One study was a ‘quasi‐experimental controlled longitudinal survey’, three were ‘randomized, controlled cross‐sectional surveys’ and three were ‘randomized controlled before and after studies’. A total of 4,834 adults were represented in the narrative synthesis, with a collective response rate of 73%. The risk of bias was high or unclear for majority of studies, while the quality rating was fair to good. Five studies reported one or both primary outcomes of interest.

Two of the four studies which reported quality of life outcomes showed positive effects for those receiving individualised funding (two showed no difference):

Site 1 (I: 43.4 / C: 22.9, MD = 20.5 (p < 0.001)); Site 2 (I: 63.5 / C: 50.2, MD = 13.3 (p < .01)); and Site 3 (I: 37.5 / C: 21.0, MD = 16.5 (p < .001)) (Brown et al., 2007);

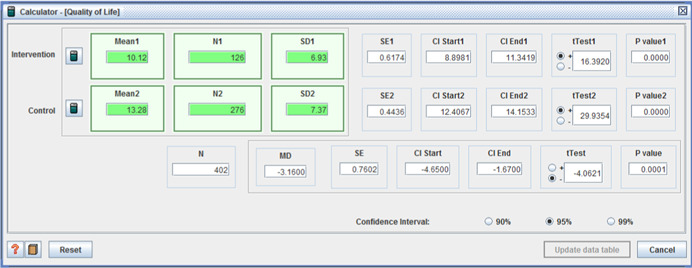

(I: M = 10.12, SD = 6.93 / C: M = 13.28, SD = 7.37, MD =−3.16, (p < .001) (95% CI: −4.65, −1.67)) (Woolham & Benton, 2013).

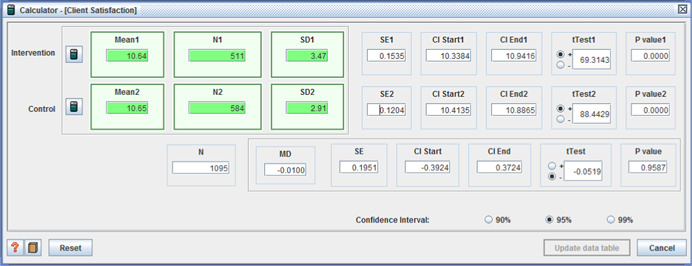

All five studies reporting client satisfaction showed positive effects for those receiving the intervention:

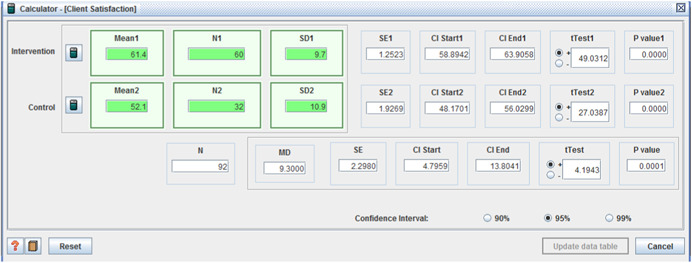

(I: 61.4,: 9.7 / C: 52.1, SD = 10.9, MD = 9.3, (p < .001), (CI 95%: 4.80–13.80)) (Beatty, Richmond, Tepper, & DeJong, 1998);

- satisfaction with:

-

○technical quality ‐ (I: 20.90, SD = 3.31 / C: 20.07, SD = 3.82, MD = 0.83, (p < .001), (CI 95%: 0.41–1.25);

-

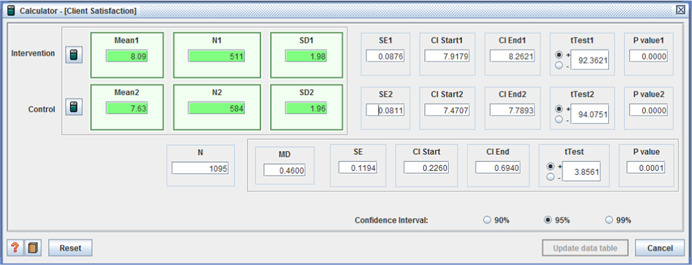

○service impact ‐ (I: 8.09, SD = 1.98 / C: 7.63, SD = 1.96, MD = 0.46, (p < .001), (CI 95%: 0.23– 0.69));

-

○general satisfaction (I: 9.06, SD = 1.65 / C: 8.66, SD = 2.07, MD = 0.40, (p < .001), (CI 95%:0.18– 0.62)); and

-

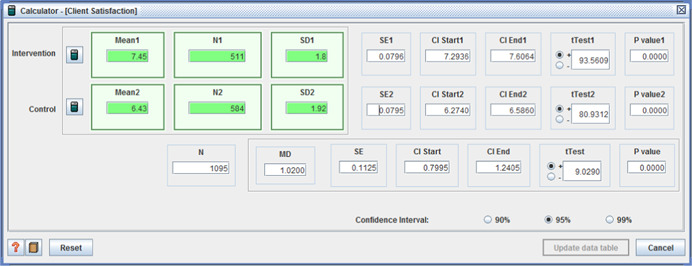

○interpersonal manner (I: 7.45, SD = 1.80 / C: 6.43, SD = 1.92, MD = 1.02, (p < 0.001), (CI 95%: 0.80–1.24)) (Benjamin, Matthias, & Franke, 2000);

-

○

- satisfaction with:

-

○caregiver help

-

▪Site 1 (I: 90.4 / C: 64.0, MD = 26.4, (p < .001));

-

▪Site 2 (I: 85.4 / C: 70.9, MD = 14.5, (p < .01)); and

-

▪Site 3 (I: 84.4 / C: 66.0, MD = 18.4, (p < .001));

-

▪

-

○and overall care arrangements

-

▪Site 1 (I: 71.0 / C: 41.9, MD = 29.2, (p < .001));

-

▪Site 2 (I: 68.2 / C: 48.0, MD = 20.2, (p < .01)); and

-

▪Site 3 (I: 51.9 / C: 35.0, MD = 16.9, (p < .001))(Brown et al., 2007);

-

▪

-

○

(I: M = 3.89, SD = 0.85 / C: M = 2.82, SD = 1.25, MD = 1.07, (CI 95%: 0.63 – 1.51) (p < .001)) (Caldwell, Heller, & Taylor, 2007);

and (I: n = 478, C: n = 431, proportion satisfied I: 0.78, C: 0.70, x2 = 7.54, (p < 0.01)) (Glendinning et al., 2008).

Secondary outcomes included physical functioning, costs and adverse effects. Only one study reported physical functioning, with no difference detected between intervention and control groups.

Two studies reported cost effectiveness data. One showed no difference between groups, while the other suggested that individualized funding was less cost‐effective than traditional supports (in one of two measures). Personal Care/HCBS alone − (Arkansas I: M = 5,435 / C: M = 2,430, MD = 3,005, (p < .001), Florida I: M = 22,017 / C: M = 18,321, MD = 3,696, (p < .001), New Jersey I: M = 11,166, C: M = 9,220, MD = 1,946, (p < 0.001)) (Brown et al., 2007, Table V.1; Dale & Brown, 2005).

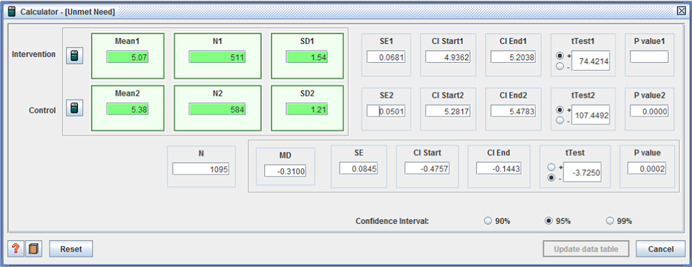

Five studies reported adverse effects with two reporting no difference between intervention and control. One study reported two measures of ‘unmet need’, with one favoring the control group (I: M = 5.07, SD = 1.54, C: M = 5.38, SD = 1.21, MD = −0.31, p < .001, (CI 95%: −0.48 to −0.14;Benjamin et al., 2000), the second showing no difference. For the remaining two studies, those receiving individualized funding reported fewer:

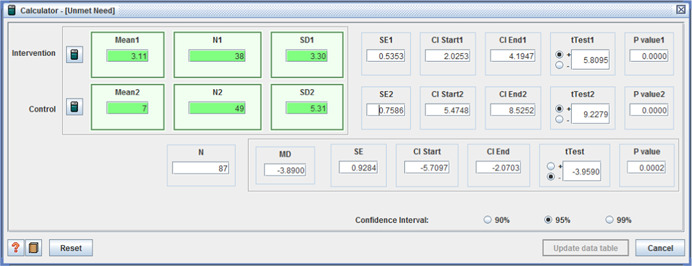

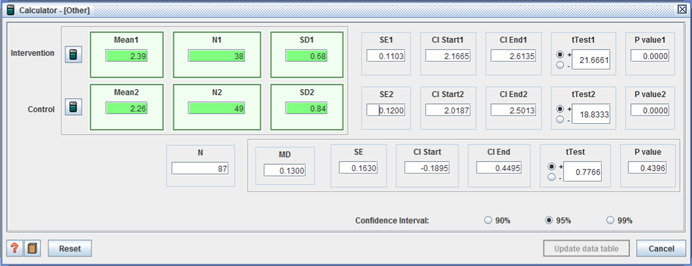

adverse effects: (I: M = 3.11, SD = 3.30 / C: M = 7, SD = 5.31, MD = −3.89, (p < .001), (CI 95%: −5.71 to −2.07)) (Caldwell et al., 2007); and

- unmet needs with daily living activities –

-

○Site 1 (I: 25.8 / C: 41.0, MD = −15.2, (p < .01));

-

○Site 2 (I: 26.7 / C: 33.8, MD = −7.1, (p < .05)); and

-

○Site 3 (I: 46.1 / C: 54.5, MD = −8.4, (p < .05)) (Brown et al., 2007).

-

○

The remaining five measures of unmet need, in the last study, varied between study sites – some reporting no difference, whilst others favoured the intervention group.

Other relevant health and social care outcomes were also reported in three of the four quantitative studies. Safety/sense of security was the only outcome on which a significant difference was reported and in favor of the intervention group (I: M = 9.18, SD = 1.57, C: 8.96, SD = 1.65, MD = 0.22, p < .05 (CI 95%: 0.03– 0.41)) (Benjamin et al., 2000).

2.6.2. Qualitative

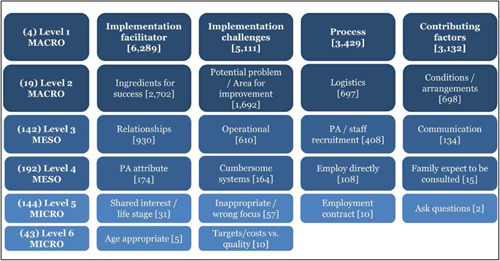

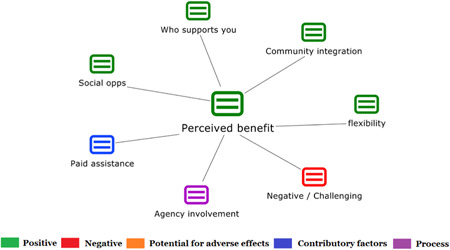

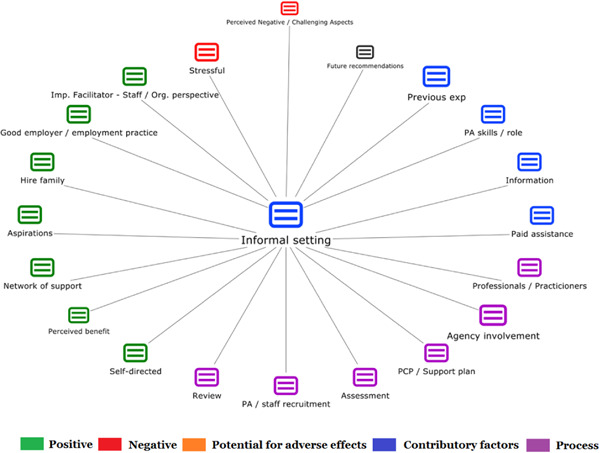

Implementation facilitators

-

1.

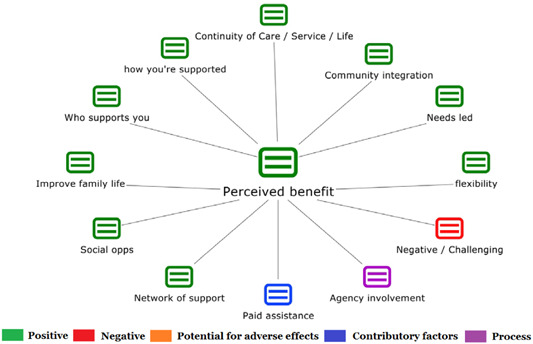

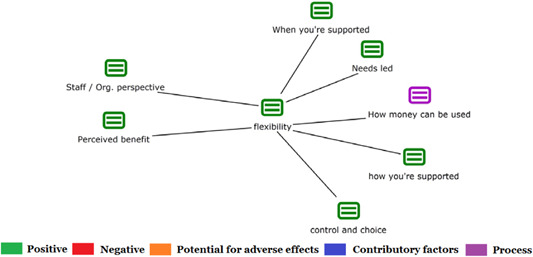

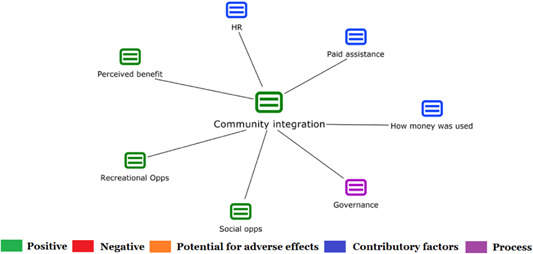

People with a disability and their carers/representatives consistently report many perceived benefits of individualized funding. This strongly suggests that implementation is well received and often advocated for, among people with a disability. Benefits that are particularly valued include: flexibility, improved self‐image and self‐belief; more value for money; community integration; freedom to choose ‘who supports you; ‘social opportunities’; and needs‐led support.

-

2.

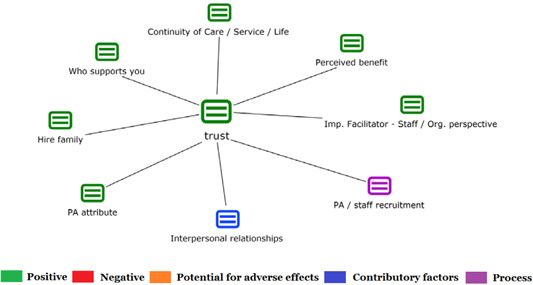

There are many mechanisms of success discussed, including the importance of strong, trusting and collaborative relationships. These extend to both paid and unpaid individuals, often forming the person's network of support which, in turn, plays an integral role in facilitating processes such as information sourcing, staff recruitment, network building, and support with administrative and management tasks. Factors that strengthen these relationships include: financial recognition for family and friends, appropriate rates of pay, a shift in power from agencies to the individual or avoidance of paternalistic behaviour.

-

3.

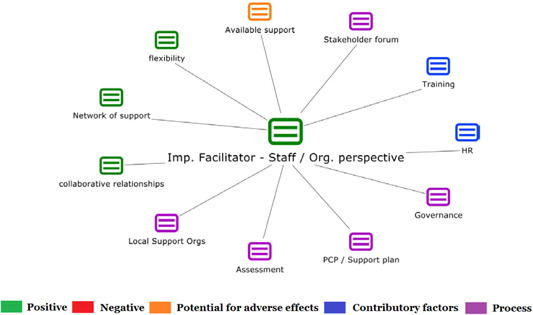

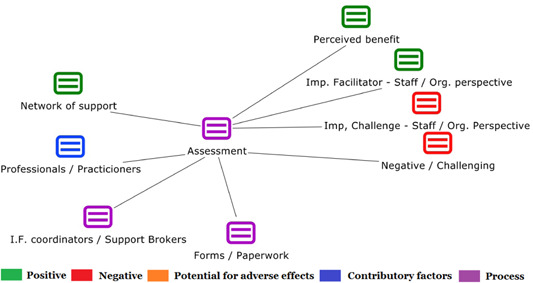

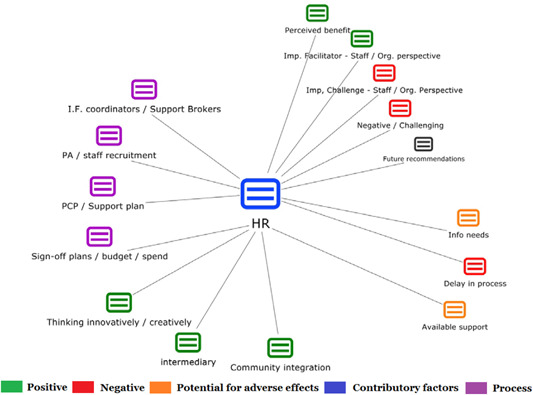

Implementation facilitators from the perspective of staff, include the involvement of local support organizations, and the availability of a network of support for the person with a disability. Timely relevant training for practitioners, coordinators, and other frontline staff is also seen as an important facilitator, as are sufficient support and other human resources available to people with a disability, such as intermediary services, community integration, and innovative/creative supporters.

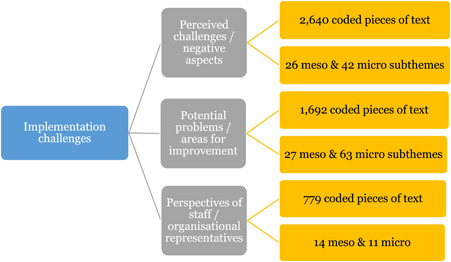

Implementation challenges

-

1.

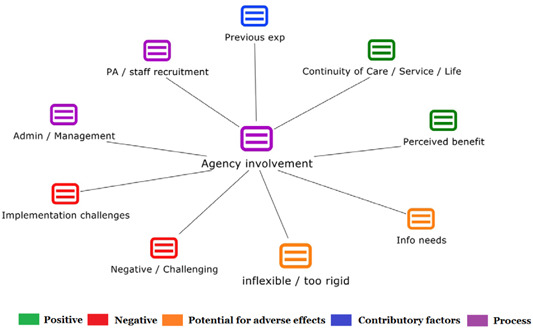

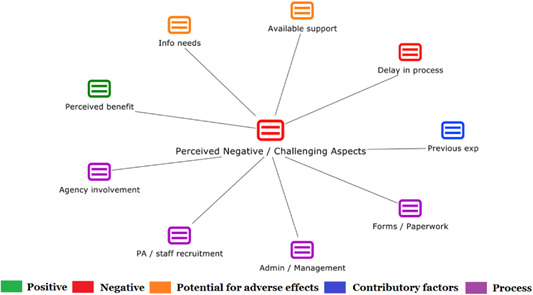

Perceived challenges for participants include agency involvement and lack of trusting working‐relationships due to previous negative experiences. Participants often experience long delays in accessing and receiving funds, which are compounded by overly complex, rigid, and bureaucratic assessment, administrative and review processes. A general lack of clarity (e.g., allowable budget use) and inconsistent approaches to delivery as well as unmet information needs are other major concerns, as are difficulties with finding and retaining suitable staff. Various internal factors (e.g., managing personal issues and negative emotions) and external factors (e.g., weak network of support) are mentioned as additional challenges to the process of implementation.

-

2.

A number of barriers, whilst viewed as generally manageable in the short term, were considered potentially problematic in the longer term. These include: inaccurate or inaccessible information sometimes due to an unclear understanding of individualized funding (compounded by an absence of practitioner training); cumbersome systems that duplicate work and are framed within the directive medical model (i.e., based on a perception that staff inappropriately focus on targets and costs rather than quality of support provided); and a lack of resources/available support, exacerbated by an inaccurate estimation of need and subsequent delay in reviewing /adjusting budgets. This, amongst other things, can lead to conflict and tensions in working relationships, which are also hampered by disabling practices (e.g., exclusion from decision‐making). Lastly, financial hardship is commonly cited, with hidden costs or administrative charges widely identified as a source of considerable concern and stress for participants.

-

3.

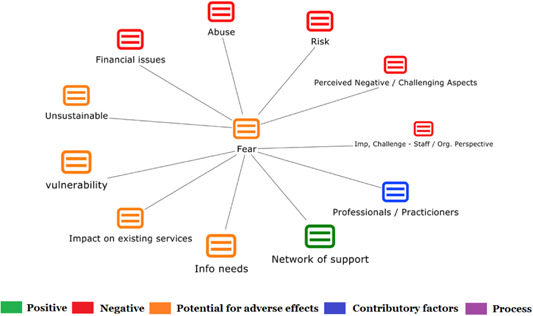

Other challenges to implementation, from the perspective of, or related to, staff/organizations include: risk aversion rooted in fears associated with perceived vulnerability of people with a disability and potential for abuse or exploitation; fear of misuse or fraud (by people with a disability); and concerns related to the long‐term sustainability of individualized funding, the quality of available supports and the impact on the traditional service providers/workforce. Staff also highlight logistical challenges in accommodating a wide range of support needs in an individualized way including, for example, responding to individual expectations and socio‐demographic differences.

2.7. Authors’ conclusions

Due to the considerable and growing interest in individualized funding as a means to improve the lived experience of people with a disability and their wider network of support (paid and unpaid), this review provides a comprehensive synthesis of evidence for future governments, funders, and policy makers. Commentators have previously criticized governments for proceeding with individualized funding initiatives without carefully considering the evidence. This review, therefore, provides an up‐to‐date repository of such evidence, particularly for countries at the early stages of planning or implementation. Not only does it present the most robust effectiveness data available, but it also specifically highlights implementation successes and challenges.

The evidence suggests that practitioners and funders need to shift their focus from one of skepticism, often grounded in fears, to one of opportunity and enthusiasm. Many of the fears, such as fraud/misuse of funds, job losses, recipients flooding the system, are not based on evidence. Funders and practitioners should be guided by the many examples of good practice outlined in this review, whilst working collaboratively toward, and appreciating the consistently reported benefits of, individualized funding. Greater investment is needed in education and training in order to facilitate stakeholder buy‐in and generate a better understanding of individualized funding and the philosophy and ethos and the associated mechanisms required for its successful implementation. Finally, policy makers need to be cognizant of the inevitable set‐up and transitionary costs involved such as capital funding for education and training, as well as redevelopment of assessment, review and other governance systems. In order to facilitate this spending, policy need to be put in place to allow the release of funds from block grants, if implementation is to be cost‐effective in the longer term.

This review clearly highlights and synthesizes the extensive and rich qualitative evidence from studies conducted in many countries – across changing social, political, economic, social care and healthcare landscapes – and over a considerable period of time. It also points to the inherent difficulties associated with collecting quantitative data on complex social interventions of this nature, with a subsequent lack of robust effectiveness data. The complexities around set‐up and attendant delays, highlighted in the qualitative data, suggest necessary changes in any future collection of quantitative outcomes. For example, future researchers should consider (resources permitting) conducting studies which incorporate longer follow‐ups (minimum 9 months), and ideally at multiple time‐points over a longer period of time. Finally, the authors of this review would encourage the adoption of mixed‐methods approaches in further systematic reviews when assessing the effectiveness of complex ‘real‐world’ interventions in the field of health and social care.

3. BACKGROUND

3.1. The problem

More than a billion people – or about 15% of the world's population – are estimated to live with some form of disability, and these rates are increasing over time (WHO, 2013). The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, defines disability as an umbrella term for impairments, activity limitations, and participation restrictions. According to the WHO, disability is the interaction between individuals with a health condition (e.g., cerebral palsy, Down syndrome, and depression) and personal and environmental factors (e.g., negative attitudes, inaccessible transportation and public buildings, and limited social supports; WHO, 2013). The WHO (2013) recognizes that disability is extremely diverse, but that generally, rates of disability are increasing due to population ageing and a greater prevalence of more chronic health conditions, whilst people with disabilities also have less access to health care services and, therefore, more unmet needs than ever before. There is further evidence to suggest that people with disabilities have lower life expectancies (Patja, Iivanainen, Vesala, Oksanen, & Ruoppila, 2000).

The many different needs of people with a disability, learning difficulty or mental health problems tend to be met through a range of activities, which may be described, collectively, as ‘social care’. These include help with personal hygiene, dressing and feeding, or general life skills such as shopping, keeping active, and socializing (Malley et al., 2012). In recent years, the disability and mental health sectors have witnessed a significant shift towards community‐based health and social care services that attempt to place the service user at the centre of decision‐making and service delivery. A growing body of policy now describes how people with all disabilities should be autonomous and self‐determined members of society.

The concept of self‐determination has its roots in self‐determination theory, which is based on human motivation, development and wellness. According to Deci and Ryan (2008), the theory focuses on the type and quality of motivation as a predictor of performance and well‐being outcomes, as well as social conditions that are improved by such motivations. Autonomous motivation, in particular (compared to controlled motivation) – whereby intrinsic and extrinsic motivation allows individuals to identify with an activity's value and integrate it into their sense of self – can lead to better psychological health, performance and a shift toward healthier behaviors. While controlled motivation – when compared to a motivation – ‘can lead to improvements, these are limited because individuals feel a pressure to think, feel and behave in certain ways (in order to avoid shame or to gain approval from the external regulation), when functioning under a system of reward or punishment. Self‐determination theory also examines the impact of self‐determination on life goals and aspirations and can be applied to a wide range of domains, including relationships, work, education and health care (Deci & Ryan, 2008). The findings of a recent meta‐analysis of 184 studies – based on self‐determination theory in health care and health promotion contexts – showed positive relationships between the satisfaction of psychological needs, autonomous motivation and positive health outcomes (Ng. et al., 2012). A number of more specific studies that have examined self‐determination in a sample of people with a disability found similarly positive outcomes (Perreault & Vallerand, 2007; Saebu et al., 2013).

One way to achieve self‐determination is by means of a personal budget (United Nations, 2006). Individualized funding is rooted in the Independent Living Movement and the associated Independent Living Fund, whereby people with a disability self‐directed their support by hiring a ‘personal assistant’ (PA) to gain more control over their lives and services. While the concept of independent living varies internationally, all approaches emphasize choice and control whilst acknowledging that personal budgets are just one way to achieve their goals (Glasby & Littlechild, 2009). A personal budget, also known as ‘individualized funding’, is an umbrella term for various funding mechanisms that aim to provide personalized and individualized support services for people with a disability. Whilst the terminology may vary, the principles are similar and are based on self‐determination, choice and, very often, person centred planning. Thus, individualized funding aims to place the service user at the centre of the decision making process, thereby recognizing their strengths, preferences and aspirations and empowering them to shape public services, social care and support by allowing the service user to identify their needs, and to make choices about how and when they are supported (Carr, 2010). As a result, many international governments are recommending individualized funding as a means to empower individual service users or their advocates, whilst ensuring transparency in the allocation and use of resources.

For example, in Ireland, there are several key policy goals (e.g., enshrined in the Value for Money and Policy Review of Disability Services (Department of Health, 2012)) which promote the use of ‘individual needs assessments’. These assessments can lead to a personal budget which can then be used to purchase services from within existing (limited) resources (Keogh, 2011). In the UK, personal budgets are common and are facilitated by standardized resource allocation systems that include a robust needs assessment. Furthermore, a social care outcomes framework is in place to monitor how well social care services are delivering the most meaningful outcomes for people with disabilities whilst also addressing any shortcomings therein (Department of Health, 2013). The monitoring process is supported by tools such as the ASCOT which was used, for example, in an evaluation of personal budgets commissioned by the UK Department of Health (Forder et al., 2012). This tool comprises eight conceptually distinct attributes or domains including: personal cleanliness and comfort; food and drink; control over daily life; personal safety; accommodation cleanliness and comfort; social participation and involvement; occupation; and dignity (Malley et al., 2012).

There are several types of personal budget which can be used to address these kinds of health and social care needs; the two most common involve either a direct payment model or an intermediary service.

A direct payment involves the funds being given directly to the person with a disability, who then self‐manages this money to meet their individual needs, capabilities, life circumstances and aspirations (Áiseanna Tacaíochta, 2014a). This may include the employment of a personal assistant to help with everyday tasks and/or the purchase of services from private, voluntary or community service provider organizations (Carter Anand et al., 2012). Direct payments often involve considerable administrative duties for the person with a disability and are more likely, therefore, to be utilized by people with a physical or sensory disability and less so by those with an intellectual or developmental disability. However, in some cases, a person with a mild intellectual disability may have the skills to manage the direct payment, with or without the support of family members or other natural supports (or informal care). More severe intellectual disabilities would most likely require some kind of family/natural support – this having been the driving force behind microboards in Canada, for example. A micro board is a small non‐profit group of informal supports (family and friends) who assist persons with disabilities to develop individualized housing and support options (Malette, 1996). This review endeavors to determine whether the benefits of direct payments are affected by the type and degree of disability, or indeed the involvement of third parties whether paid or unpaid.

A microboard, brokerage model, or ‘managed’ personal budget, whilst it provides a similar amount of freedom (as a direct payment) for the person with a disability around choice and control of services utilized, it involves a third‐party assuming responsibility for administrative tasks and providing support, guidance and information to enable the person to successfully plan, arrange and manage their support services or care plans (Carr, 2010). A ‘managed’ personal budget tends to focus more on administration and financial management, with the budget held centrally by an organisation. This service is often referred to as a fiscal intermediary (Carter Anand et al., 2012). The tasks of a broker, on the other hand, include working with the person with a disability to develop an individual action plan, as well as researching options within the community to fulfil the goals in the action plan. The broker can also assist in negotiating costs with service providers and are available for support of the individual when necessary (PossibilitiesPlus, 2014). Brokerage models tend to have a far reaching impact across service provision and local authority purchasing by encouraging more flexible and innovative solutions for user‐orientated services, whilst also influencing the development of payment schemes (Zarb, 1995).

Whilst the involvement of brokers is ongoing, their presence in the life of the individual tends to be more intensive in the initial transition (i.e., from traditional services) and set‐up stages. During this period, the broker will help to develop the ‘circle of support’, either from scratch when none currently exists, or by expanding an existing support structure to include extended family members, such as aunts, uncles, cousins, friends and members of the wider community. During this initial period, the broker may also assist in the recruitment of staff for day‐to‐day support. For this reason, this review seeks to determine whether or not these intervention effects differ based on the level and quality of support available, both paid and unpaid. Some research suggests that the circle of support is integral to the successful implementation of such an intervention (Curryer, Stancliffe, & Dew, 2015; Fleming, McGilloway, & Barry, 2015c). Furthermore, the quality of paid support may also affect outcomes since the provision of broker/facilitator training has been found to be a successful element of individualized models of support (Fleming et al., 2015c; Lord & DeVidi, 2015).

A third type of model, the Cash and Counselling model, is found predominantly in the US and allows the user the flexibility to choose between a self‐managed and a professionally managed/assisted account. This represents a combination of the direct payment and intermediary models described above (NRCPDS, 2014). In many jurisdictions, the brokerage/support function which facilitates planning and implementation, is separated from the ‘fiscal management’ supports which handle the accounting and human resource issues, but not the personal planning/support/monitoring element. While these can be conflated in some cases, it is generally considered important to maintain the independence of the brokerage/planning function from the fiscal dimension to avoid conflict of interest. The separation of the two allows individuals or advocates who do not wish to have any planning support to secure the ‘payroll’ services required without any obligation to avail of planning and monitoring supports.

While ‘individualized funding’ is emerging as an umbrella term for the various funding mechanisms, the terminology remains unclear. A decade ago, ‘cash‐for‐care’ or ‘cash and care’ were predominant umbrella terms when reviewing evidence over several decades from the US, UK and EU (Glendinning & Kemp, 2006; Ungerson & Yeandle, 2007). These early studies highlighted the risks associated with the marketization and indirect privatization of care services whereby ‘consumers of care’ increasingly act as employers without necessarily having the human resource skills or knowledge of available care choices (Woods, 2008). In contrast, evidence suggests that people availing of individualized funding are capable of acquiring the necessary skills, or indeed able to outsource certain tasks in order to successfully bypass the service providers and contract their support services directly (Fleming et al., 2015c). Thus, there exists a tension between individuals with a disability, who can secure potential cost savings while having more autonomy, and traditional service providers who need to maintain contractual agreements with staff members within their organizations.

Further tensions may also exist for frontline staff between their ethical obligations to promote empowerment and self‐determination whilst honouring their legal obligations to limit access to individualized funding (Ellis, 2007). Another challenge for staff relates to risk management. A balancing act is required to facilitate positive risk‐taking whilst ensuring that the individualized funding‐specific risks, such as financial abuse, neglect or physical/emotional abuse, are avoided. This requires careful consideration and planning, but risk management can vary considerably. For example, during the piloting of personal budgets in the UK, local authorities conducted risk assessments but in some cases relied on annual reviews, thereby placing the onus of responsibility on individuals or families in the interim (Glendinning et al., 2008). Carr and Robbins (2009) also highlight the region‐specific contextual factors, such as culture and policy, which can influence implementation of individualized funding. For example, in certain jurisdictions in Canada, the US and the Netherlands, it is compulsory to use an independent support broker, whilst in the UK and US, ‘personal assistants’ are the preferred option for those receiving personal budgets. The eligibility criteria may also differ at initial implementation depending on the region. For example, in Canada, the focus was on younger people with learning disabilities whereas the Swedes focused on adults with physical disabilities; furthermore, very few regions accommodated people with mental health problems. Objectives also differed; for example, Australia initially focussed on tackling fragmented service provision, particularly in rural areas, while the US concentrated on solving staff shortages in long‐term care facilities (Carr & Robbins, 2009).

All of the above interventions, regardless of delivery mode, involve a transitionary period which can present challenges for individuals and families, particularly when national systems of allocating resources are not in place and families have to negotiate the release of funds from a regional disability manager, as is the case, for example, in Ireland (Fleming et al., 2015c). This period of transition can also be a time of great uncertainty for individuals and their families (where applicable) who have left a form of service provision to which they have been accustomed, often for many years. As a result, the length of time that the intervention has been in place may considerably affect its real or perceived effects. Furthermore, socio‐demographic factors may have a similar impact; for example, an older person may have been using traditional forms of services for much longer than a young adult transitioning from mainstream school or another form of secondary education. Thus, past experiences, such as institutionalization, may dramatically affect an older person's ability to adapt to this new model of service provision. Equally, more people living in rural areas have been found to avail of day services when compared to urban dwellers, potentially due to a lack of alternatives within the community (Fleming, McGilloway, & Barry, 2016a). This dependence on traditional day services may impact an individual's ability to adjust to the new model, or could limit the potential for community integration due to a lack of community services for the general population. Therefore, this review took such confounding factors into consideration, both in the inclusion/exclusion criteria and in the subgroup analysis.

3.2. The intervention

For the purposes of this review, the intervention included any form of personal budget, regardless of the name given to the model of delivery. As indicated above and outlined in Table 1, these models may be described in many different ways. For example, Webber et al. (2014) identified the following terms: ‘Individual Budgets’; ‘Recovery Budgets’; ‘Personal Budgets’; ‘Direct Payments’; ‘Direct Health Budgets’; and ‘Cash and Counselling’. Others include ‘third party managed’ personal budgets, direct payments managed by an appointed person and individual service funds. However, a personal budget, to be included in this review, must have the following fundamental characteristics: (a) it must be provided by the state as financial support for people with a lifelong physical, sensory, intellectual, developmental disability or mental health problem; (b) the recipient must be able to freely choose how this money is spent in order to meet their individual needs; (c) the individual can avail of ‘brokerage/intermediary’ services or any equivalent service which supports them in terms of planning and managing how the money is used over the lifetime of the funding period; (d) the recipient can also independently manage the personal budget, in whatever way is feasible, such as setting up a ‘Company Limited by Guarantee’ as is the case in Ireland (Áiseanna Tacaíochta, 2014b); and (e) the personal budget may be provided as a ‘once‐off’ pilot intervention for a defined period of time (minimum 6 months), or it can be a permanent move from more traditional forms of funding arrangements that exist nationally or regionally.

Table 1.

Examples of terminology used globally

| Country | Terms used | Source of money | Support / care mechanism | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S.A | Self‐Determination programs | Medicaid waivers at State level | Independent consultant | |

| Cash and Counseling | Fiscal intermediary services | |||

| Consumer Directed Care/Support | ||||

| U.K. | Direct Payments | Local Authority | Personal assistant | |

| Individual Budget | Local Authority | Package of care from multiple sources | ||

| Block funding from the Social Care budget | Social Care budget | Residential costs and associated care costs | ||

| Independent Living Fund | Department for Social Security | Care from agency OR personal assistant | ||

| Other terms used in UK | Recovery Budget | |||

| Personal Budget | ||||

| Personal Health Budget | ||||

| Microboard | ||||

| Other UK funding sources: | Supporting People fund | |||

| ||||

| ||||

| Netherlands | Person‐centred budget | Dutch Welfare State | Package of self‐determined care. Assisted by employed care worker (Often Informal (family) carers) | |

| Ireland | Independent Support Broker/Brokerage | Innovation funding for pilot | Package of care from multiple sources/residential costs | |

| Ongoing funding from HSE | ||||

| Direct payments | Innovation funding for pilot Ongoing funding from HSE | Package of care from multiple sources/residential costs | ||

| Self‐management model | Innovation funding for pilot | Community Connector | ||

| Canada | Direct Payment/Direct Funding | Community Living British Columbia (CLBC) | Supports and services for the individual as agreed to by the individual, agent and CLBC facilitators and CLBC analysts | |

| Host Agency Funding | CLBC | |||

| Other terms used in Canada |

|

|||

|

||||

|

||||

| Australia |

|

Microboard | ||

| Self‐directed funding | ||||

| ||||

| Consumer‐directed care | ||||

| ||||

| ||||

| Other terms used internationally | Indicative allocation; Individual service fund; Managed account; Managed budget; Notional budget; Personalized care; Pooled budget; Self‐directed care; Self‐directed support; Virtual budget; Cash‐for‐care | |||

Individualized funding interventions are implemented with a view to delivering a range of positive health and social care outcomes over time. It is expected that a persons’ quality of life will improve (e.g., socially, personally, environmentally and in terms of their physical/psychological health) as a result of their increased autonomy, choice and control over daily life decisions and greater social integration and interaction. Client satisfaction is also expected to increase due to greater self‐determination, whilst the same is true for physical functioning which may improve due to better independent life skills (i.e., taking on more responsibilities such as shopping and household chores).

Many of these quality of life outcomes, if improved, could arguably generate cost benefits, although the evidence in this respect is very limited. The small pool of evidence would suggest that individualized funding can be cost effective, ranging from 7% to 16% in the US (Conroy, Fullerton, Brown, & Garrow, 2002) and 30% to 40% in the UK (Zarb & Nadash, 1994). Conversely, one UK study suggested that individualized funding may not result in cost savings, but does represent value for money (Glasby & Littlechild, 2002). Stainton, Boyce and Phillips (2009) support these more conservative findings showing relative cost neutrality for individualized funding when compared to independent service providers; however, individualized funding was more cost effective than traditional in‐house service provision. Furthermore the authors reported higher levels of user satisfaction for those availing of individualized funding, thereby highlighting the link between client satisfaction, quality of life and cost benefits.

3.3. Why it is important to do the review

The international move towards individualized funding has led, in turn, to a growing interest in identifying methods, more generally, that might offer the most potential in terms of informing effective and efficient resource allocation, particularly in the context of recent economic reforms. However, these strategic and policy decisions would appear to be evolving on the basis of locally sourced or anecdotal evidence, since there appears to be a lack of high quality experimental studies in the area (Webber et al., 2014). Nonetheless, current international evidence suggests many benefits of individualized funding, such as increased choice and control, a positive impact on quality of life (QoL), reduced service use and potential for cost effectiveness (Field, 2015; Webber et al., 2014). Thus, it is important to explore the pathways/mechanisms that lead to change (in this case positive change) and to determine the links between activities, outputs and outcomes (Taplin, Clark, Collins, & Colby, 2013).

In the case of individualized funding, it is intended that people with disabilities have more autonomy over their lives which, in turn, acts as a mechanism to enhance self‐determination, something that most people without a disability take for granted. A mantra that resonates globally within the disability sector is ‘Nothing about us, without us’ (Charlton, 1998). This aptly illustrates the fundamental need to place the person with a disability at the centre of decision making. Thus, individualized funding and attendant services are designed as a vehicle/mechanism for potentially improved health and social care outcomes. Such individualized funding arrangements are also important in shifting the power dynamic from service providers and placing it in the hands of individuals with a disability (or their families).

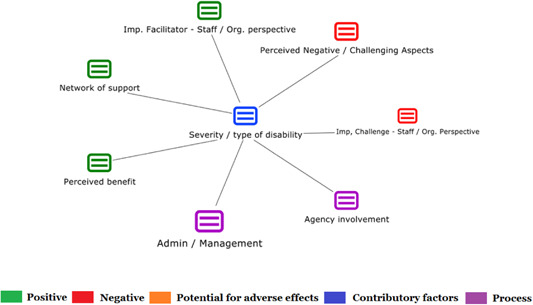

Glendinning et al. (2008) reported mixed findings in their RCT on the impact of a personal budget on health, social care and personal outcomes within their subgroup analyses. Outcomes varied according to age or mental health status, whilst the type of disability did not appear to play an important role (Glendinning et al., 2008). Furthermore, health outcomes may vary across various jurisdictions where different rules exist on what can or cannot be funded from a personal budget – particularly health services which may have different eligibility rules by region. Importantly, international evidence on individualized funding models suggests that there is no ‘one size fits all’ approach for everyone; hence, there is considerable variation with regard to: levels of choice and control given to service users; the professionals involved; the type of funder; and the limitations in both the services available for purchase and administrative structures/ processes (Carter Anand et al., 2012).

It is notable that the type of study design also varies considerably in the evaluation of individualized funding. Studies include, but are not limited to: RCTs (Glendinning et al., 2008; Shen et al., 2008); quasi‐experimental trials with controls (Forder et al., 2012; Foster, Brown, Phillips, & Schore, 2003; Teague & Boaz, 2003); and without controls (Spaulding‐Givens, 2011); cross‐sectional surveys (Hatton & Waters, 2011; Lawson, Pearman, & Waters, 2010); and qualitative studies (Coyle, 2009; Homer & Gilder, 2008; Maglajlic, Brandon, & Given, 2000).

3.3.1. Prior reviews

We are aware of only two reviews, to date, which have specifically examined individualized funding for people with a disability or mental health problem. Both of these included quantitative and qualitative data. The first, by Carter Anand et al. (2012) (25 studies), was a rapid evidence assessment rather than a rigorous systematic review. As a result, the search strategy had some major limitations, such as the exclusion of non‐English studies and a geographical restriction to seven countries: the US, Australia, Germany, Great Britain, Ireland, The Netherlands and New Zealand. The authors acknowledged that the search strategy had resulted in a limited evidence base, which precluded the possibility of drawing strong conclusions about the implementation and impact of individualized funding. However, they also indicated that the qualitative evidence derived from service users tended to reflect positive views about the initiatives. The review did not report on the characteristics of included studies, or on study results in any detail. Furthermore, there was no detail about whether or not a meta‐analysis was conducted, or the methods by which the qualitative data were synthesized. In addition, no subgroup analyses were conducted despite an apparent broad definition of disability (e.g., various types and level of physical and intellectual disabilities, inclusion of older people and those with mental health problems). Finally, while quality was assessed, no information was provided on any assessment of bias.

The second more recent review by Webber et al. (2014) closely followed the EPPI‐Centre methodology for conducting a systematic review, appraising methodology and assessing the research quality and reliability (Gough, Oliver, & Thomas, 2012). Once again however, non‐English studies were excluded, but more importantly, the focus of this systematic review was on mental health only; other physical or learning disabilities were included only if they co‐existed with mental health problems. Fifteen studies were included in the review and the main findings showed that individualized funding can have positive outcomes for people with mental health problems in terms of choice and control, impact on QoL, service use and cost‐effectiveness (Coyle, 2009; Davidson et al., 2012; Glendinning et al., 2008; Spandler & Vick, 2004). However, methodological shortcomings, such as variation in study design, sample size and outcomes assessed, were reported to limit the extent to which the study findings could be accurately interpreted or generalized. This was compounded by considerable variation in the support models included, but without any attempt to undertake a sub‐group analysis (e.g., ‘Personal Budget’ versus ‘Direct Payment’ versus ‘Recovery Budget’ versus ‘Cash and Counselling’). Consequently, the authors concluded that more large, high quality, experimental studies were required before any definitive conclusions could be reached (Webber et al., 2014).

3.3.2. Contribution of this review

We are not aware of any systematic review that focuses on the effectiveness of individualized funding in relation to people with a disability of any kind, including mental health problems. Given the new policy imperative around individualized funding and the growing pool of studies in this area, there is now a need for a systematic review of these models (when compared to a control) across a spectrum of disabilities, in order to assess their effectiveness in relation to health and social care outcomes. A supplementary synthesis of the non‐controlled evaluations and qualitative studies was also included in order to capture these findings in an area that is relatively new. Due to the complex nature of implementing novel initiatives that challenge the status quo, many qualitative studies have been undertaken to capture important perspectives, successes and challenges and these cannot, therefore, be overlooked in this review.

This review: (a) assesses the effectiveness of individualized funding interventions; (b) reports subgroup differences in order to explore how effects may differ by various client and intervention parameters; and (c) appraises and synthesizes the experiences of key stakeholders. The ultimate aim of this review is to provide useful, robust and timely data to inform service providers/organizations working in the field of disability and to provide a rigorous evidence base on which decisions by policy makers (and drivers) can be made around different resource allocation/individualized funding models to support greater choice and control by individuals in their daily lives.

4. OBJECTIVES

4.1. Objectives of the review

The objectives of this review are to: (a) examine the effectiveness of individualized funding interventions for adults with a lifelong disability (physical, sensory, intellectual, developmental or mental disorder), in terms of improvements in their health and social care outcomes when compared to a control group in receipt of funding from more traditional sources; and (b) to critically appraise and synthesize the qualitative evidence relating to stakeholder perspectives and experiences of individualized funding, with a particular focus on the stage of ‘initial implementation’ as described by Fixsen et al. (2005).

Most interventions included in the synthesis, at a minimum, should have reached initial implementation. Unsurprisingly, this is often the most challenging stage of implementation. Fixsen et al. (2005) describe initial implementation as complex process, requiring ongoing/multi‐level change (e.g., individual, environmental and organizational) that is not necessarily linear and which is influenced by external administrative, educational, economic and community factors. As a result, it is during this stage that stakeholders can encounter/experience the most fear of change or inertia. The next stage of implementation, ‘full operation’, cannot be initiated until the challenges associated with initial implementation are overcome and associated learnings are integrated into policy and practice.

Key questions include:

What model of personal budget (e.g., direct payment or facilitated) is relatively more effective at improving health and social care outcomes?

Do support structures such as resource allocation systems, needs assessments, support planning and review affect intervention effectiveness?

How is the intervention effect linked to length/intensity of intervention?

Is the intervention effect linked to type and/or severity of presenting disability (e.g., physical, sensory, intellectual, developmental or mental disorder)?

Is the effect linked to implementation fidelity (e.g., does level of staff knowledge, access to independent information, advice, training and support affect intervention effectiveness)?

Does the effect differ depending on the level of support available from non‐paid advocates (e.g., friends and family)?

Do socio‐demographic factors, (e.g., age, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, gender, religious beliefs, household income, urban/rural setting) impact on intervention effectiveness?

What are the experiences, barriers and facilitators associated with the implementation of individualized funding initiatives for people with a disability or mental health problem?

What is the economic impact of the intervention from both a service user and public service perspective?

5. METHODS

5.1. Criteria for considering studies for this review

5.1.1. Types of studies

Eligible study designs for questions relating to the effectiveness of the individualized funding intervention included randomized, quasi‐randomized and cluster‐randomized controlled trials. Due to the complex nature of the intervention and attendant ethical constraints, randomization may not be possible since the aim of individualized funding is to increase choice and control, and randomization limits this option. Therefore, non‐randomized studies (e.g., controlled before and after studies, cross‐sectional surveys, longitudinal studies or cohort studies) were considered in this part of the review. Randomized and non‐randomized studies are reported separately. A key feature across the studies was the presence of a control group, in order to ascertain differences across a set of health and social care outcomes. As such, single‐case designs, pre‐post studies without a control group, non‐matched control groups, or groups matched in a post‐hoc way after results were known, were excluded from the review.

For the qualitative synthesis, eligible studies included: ethnographic research; phenomenology; grounded theory; participatory action research; case studies; or mixed methods studies in which qualitative approaches were used to gather data. Methods used to collect the qualitative data in primary studies included: interviews; focus groups; observation; open‐ended survey questions; and documentary analysis.

5.1.2. Types of participants

Population Inclusion criteria

Adults aged 18 years and over receiving a personal budget

- Where the study has categorized the person as having:

-

○any form or level of physical, sensory, intellectual or developmental disability

-

○any form or level of mental health problem, disorder or illness

-

○dementia

-

○

- Residing in any country

-

○Residing in any type of residential setting (own home, group home, residential care setting, nursing home, hospital, institution)

-

○

Population Exclusion criteria

Minors under the age of 18 since the decisions around their daily lives are ultimately made by a parent or legal guardian.

Older people (>= 65) who have a disability, but where it was not present for at least ten years of their working‐adult life. Such disabilities would generally be age‐related, such as frailty or difficulty with completing Activities of Daily Living, and are not the focus of this review

Privately funded individualized funding interventions.

5.1.3. Types of interventions

Any form of personal budget or individualized funding which is state funded directly or indirectly.

For the quantitative element of this review, where a control group exists, support services may take two forms: (a) traditional ‘services as usual’ (e.g., predetermined group activities, provided in a congregated setting and financed through block funding to service providers whereby previous annual spend for a service provider is used to estimate the required funding for the upcoming year (NDA, 2011); or (b) a different type of personalized support which does not include a personal budget where, for example, a service user might access services through a congregated setting where finances are centralized, but where an individualized plan is used to determine service user needs and preferred activities. However, the individualization of planned responses may be limited, for example, by majority preferences within the group, staffing limitations or pre‐existing service options.

Individualized funding interventions were excluded where the budget was provided to families, guardians/other carers (only), or where the person with a disability did not have an active role in the decision making and planning process and could not exercise control over the use of funds. However, studies were included where an advocate was managing the funds after an individual assessment of need took place and provided that the funds were being used to meet the needs identified during the assessment.

A personal budget provided by the person's family or by another private means was not included, as this review focuses on use of public funds for people with a disability. Furthermore, private sources of funding introduce confounding factors which would lead to uncontrollable bias.

5.1.4. Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

The primary outcomes of interest (i.e. pertaining to the quantitative studies) are ‘Quality of Life’ and ‘Client Satisfaction’. Each is described in more detail below.

Quality of life, including: physical health; psychological health; well‐being; social relationships; personal and life satisfaction; and environment or disability‐specific QoL including: choice; control over daily living; autonomy; social acceptance; social network and interaction; social inclusion and contribution; future prospects; communication ability; safety and personal potential. Typical measures include the WHO Quality of Life Disability module (M.J.Power & Green, 2010) and the ASCOT (Malley et al., 2012).

Client satisfaction, as measured by access to and continuity of care, shared decision making, level of choice, control and self‐determination, planning, coordination and review of care, respect shown, information provided, staff attitudes and responsiveness, physical and emotional comfort; encouragement, opportunities for positive risk‐taking, risk management, availability of services, staff training and management, cost and administrative burden. The Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers is an example of a set of satisfaction scales which measure and evaluate various aspects of consumers’ experiences of health care, including a tool for measuring: health plans; group and individual service providers; hospitals; nursing homes; and behavioural health services (Kane & Radosevich, 2011b).

Secondary outcomes

Physical functioning, measured by Activities of Daily Living (ADL), such as: bathing; dressing; feeding; transfer; toileting or advanced independent living activities such as: shopping; doing chores; and cleaning. These can be measured using, for example, the Katz Index of ADLs (Katz, Ford, Moskowitz, Jackson, & Jaffee, 1963 as cited in Kane & Radosevich, 2011a).

Costs data, measured for example by: size of personal financial package available; brokerage/management fees; cost of individual services; and cost of recruiting staff (for self‐managed).

Adverse outcomes

Adverse psychological impact, as measured by symptoms of depression, anxiety, stress, social dysfunction, and feelings of isolation. Depression can be measured as clinical (e.g., the Hamilton Rating Scale) or non‐clinical depression (e.g., Carroll Rating Scale;Kane & Radosevich, 2011a) or can be disability specific (e.g., Glasgow Depression Scale for people with a Learning Disability) (Cuthill, Espie, & Cooper, 2003). Anxiety may have been measured for example by general anxiety scales such as the Anxiety Adjective Checklist or Zung's Self‐Rating Anxiety Scale (Kane & Radosevich, 2011a) or the Glasgow Anxiety Scale for people with a learning disability (Hermans, van der Pas, & Evenhuis, 2011).

Qualitative data

For the qualitative synthesis, outcomes or phenomena of interest involved the experiences of stakeholders in receiving and implementing a personal budget. Stakeholders include the client, family members, advocates, personal assistants/key workers, professional staff such as occupational therapists or physiotherapists and other members of the community involved in the process.

5.1.5. Duration of follow‐up

The intervention should be in place for at least 6 months before follow‐up. This does not apply in the case of qualitative studies.

5.2. Search methods for identification of studies

The Campbell Collaboration policy brief for searching studies and information retrieval, informed the search strategy as presented below (Hammerstrøm, Wade, Hanz, & Klint Jørgensen, 2009). In addition, an information retrieval specialist within Maynooth University was consulted during the preparation of search strings, while several search retrieval specialists provided recommendations during the peer‐reviewing process (of the study protocol). Padraic Fleming, the lead author, conducted the searches once the protocol had been peer‐reviewed and approved by Campbell Collaboration. The searches were conducted during the period February 19th and March 9th, 2016. At the end of the screening process, key journals were searched using key‐terms up to the end of January 2017. Studies in any language and from any country were included, provided the abstract was in English.

Searches were completed, as per protocol with a number of minor additions. In some cases the search string could be copied and pasted directly from the protocol, whilst other databases required the search string to be manually populated. As recommended by Higgins and Green (2011), the search strategy is reported in Appendix 1, with any changes to protocol highlighted in bold text. The search strategy is reported (exactly) for each database utilized. This ensures that all searches are reproducible. Furthermore, details of additional grey literature databases are included (highlighted in bold), as recommended by Campbell Collaboration information retrieval specialists.

5.2.1. Electronic searches

A selection of electronic search databases relevant to the area of study was searched. Where available, database thesauri were used to identify database specific terms for inclusion. These terms were ‘exploded’ to encompass all narrower terms when appropriate to do so. These terms also helped in the identification and inclusion of all possible synonyms. In addition to these database specific terms, free text terms which were identified from within the current literature were used to further broaden the search.

The follow databases/search engines were searched:

-

1.

CINAHL (Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature)

-

2.

EMBASE

-

3.

Medline First Search

-

4.

ASSIA (Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts) (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, 2009)

-

5.

PsycInfo

-

6.

SCOPUS

-

7.

Sociological Abstracts

-

8.

Worldwide Political Science Abstracts

-

9.

EconLit with Full text

-

10.

Business Source Complete

-

11.

Greylit

-

12.

OpenGrey.eu

-

13.

ProQuest Dissertations and Theses

-

14.

Google Scholar

-

15.

Google

-

16.

Australian Policy Online

-

17.

VHL Regional Portal – Latin America database

-

18.

NORART (Norwegian and Nordic index to periodical articles)

-

19.

Theses Canada

Search terms

The terms used to customize the search string for specific databases were based on the ‘population’ and ‘intervention’ of interest. ‘Disability’ and all possible variations including mental health, disorders and autism was the first keyword. Where available, database‐specific terms were used, encompassing all types of disability (see extensive list for PsychInfo – Appendix 1). Any overarching terms, encompassing all disabilities – when available – were exploded (see Embase search string in Appendix 1). ‘Budget’ and all its variations was the second keyword. The following truncations: ‘person*’; ‘individ*’; and ‘self‐direct*’ were used to refine the results pertaining to the main keywords, linking them when necessary to the main keywords with, for example, ‘near/n’ or ‘w/n’, where possible. All other keywords were connected with ‘or’/‘and’ when searching titles and abstracts. Search terms were also truncated, when appropriate, to allow for variations in word endings and spellings. Truncation conventions were specific to the database searched. A list of free‐text terms identified in the literature was used to supplement the syntax developed. The term ‘self‐determination’ (‘self‐determin*’) was added to the free‐text terms in addition to the terms outlined in the protocol. Individual studies and systematic reviews already known to the authors were used to check the sensitivity of search strings developed (Carter Anand et al., 2012; Webber et al., 2014).

Study design and outcomes were not included as part of the search strategy as it was anticipated that this would potentially lead to the omission of relevant studies. Furthermore, the mixed methods approach on which this review is based, led to broad inclusion criteria for study designs (Appendix 2 – methods paper).

All search strings are provided in Appendix 1. A sample search string is outlined below:

‘intellectual impairment’/exp OR ‘disability’/exp OR handicap OR ((people OR person* OR individ*) NEAR/3 (disabil* OR disable*)):ab,ti OR insanity OR (mental NEAR/1 (instability OR infantilism OR deficiency OR disease OR abnormality OR change OR confusion OR defect* OR disorder* OR disturbance OR illness OR insufficiency)):ab,ti OR (psych* NEAR/1 (disease OR disorder* OR illness OR symptom OR disturbance)):ab,ti AND (‘financial management’/exp OR ((budget OR finance* OR fund* OR resource OR money OR income OR purchas* OR broker* OR salary OR capital OR investment OR profit) NEAR/3 (individual* OR person*)):ab,ti) OR ‘cash for care’:ab,ti OR ‘consumer directed care’:ab,ti OR ‘direct payment’:ab,ti OR ‘indicative allocation’:ab,ti OR ‘individual budget’:ab,ti OR ‘individual service fund’:ab,ti OR ‘managed account’:ab,ti OR ‘managed budget’:ab,ti OR ‘notional budget’:ab,ti OR ‘personal budget’:ab,ti OR ‘personal health budget’:ab,ti OR personalisation:ab,ti OR ‘personalised care’:ab,ti OR personalization:ab,ti OR ‘person centred’:ab,ti OR ‘pooled budget’:ab,ti OR ‘recovery budget’:ab,ti OR ‘resource allocation system’:ab,ti OR ‘self‐directed assessment’:ab,ti OR ‘self‐directed care’:ab,ti OR ‘self‐directed support’:ab,ti OR ‘support plan’:ab,ti OR ‘virtual budget’:ab,ti OR ‘disability living allowance’:ab,ti OR ‘self‐determin*’:ab,ti AND [1985–2015]/py

Grey literature

An international list of grey literature databases published by the Campbell Collaboration (Hammerstrøm et al., 2009) was consulted in the first instance. A US electronic database, run by The New York Academy of Medicine and dedicated to specifically searching grey literature in public health, was also employed (www.greylit.org). Opengrey.eu was used to search grey literature in Europe. Other international grey literature databases utilised, as recommended by Hammerstrøm et al (2009) included: VHL Regional Portal for Latin American databases; NORART capturing Norwegian and Nordic articles; and Australian Policy Online. Boolean operators are not supported by these databases; therefore keywords, based on the database searches of published work, were searched separately (Appendix 1). Similar search strategies were employed for other country/region specific sites.

Timelines and other restrictions were not imposed in order to maximize the results from grey literature. Reference lists from relevant studies and previous systematic reviews were visually scanned to identify any unpublished literature not previously identified. Google Scholar, the popular internet search engine, was also used to search the terms developed for the academic databases in order to identify any relevant web materials or organizational/governmental reports which are unpublished or not accessible through electronic databases. ProQuest Dissertations and Theses was used to search for relevant theses at doctoral and masters level. Finally, Google search engine was searched to identify any relevant conference proceedings and government documents in addition to relevant NGOs that may have potentially useful research materials unpublished elsewhere. In total, 1,000 Google results and almost 6,000 Google Scholar titles were scanned (Appendix 1).

5.2.2. Cross‐referencing of bibliographies

The references of each of the final studies included in the review were scanned to identify any additional potentially relevant studies. Literature reviews and other non‐eligible studies were also scanned for relevant titles. This forward citation searching led to the addition of 40 additional the full‐text screen. The bibliographies from the two previous reviews were also cross‐referenced (Carter Anand et al., 2012; Webber et al., 2014).

5.2.3. Conference proceedings and experts in the field

Conference proceedings such as the extensive syllabus from the recent international conference hosted by The University of British Columbia's Centre for Inclusion and Citizenship (‘entitled Claiming Full Citizenship: Self Determination, Personalization, Individualized funding) were consulted. This syllabus provided slides from over 100 presentations and contact details for research and practice experts from around the world who specialize in the delivery of individualized funding, self‐determination and personalization of services for people with a disability. This syllabus was used as a reference point for identifying and sourcing data from unpublished or ongoing studies and guided the hand‐searching. Such hand searching led to the addition of 63 to the full‐text screen.

Corresponding authors as listed on published works were contacted, when necessary, to request access to primary data, and/or to provide clarification during the data extraction process on, for example, demographic information and timelines to follow‐up.

5.2.4. Timeframe (and other filters)

According to Leece & Leece (2011), the origins of personalized brokerage schemes and individualized funding can be traced back to the mid‐1980s in to the USA. Around the same time (1988), legislation in Western Australia introduced a form of personal budget known as the Local Area Coordination charter which facilitated a mechanism for ‘Direct Consumer Funding’ (Carter Anand et al., 2012). Thus, individualized funding appears to have emerged for the first time, around the mid‐eighties. For this reason, the searches of published literature were limited to the period 1985 – quarter 1 of 2016. For example, date filters were applied to the Scopus search results (Appendix 1). Other filters were also applied where necessary to refine the search, such as exclusion of non‐relevant subject areas (See Embase search string Appendix 1).

5.2.5. Manually browsing key journals

Toward the end of the data retrieval process, the most recent issues of key journals (i.e., those that produced the most studies in the meta‐analysis) were searched manually to capture any relevant work published since the searches were last run. Seven journals were searched including: (a) British Journal of Social Work; (b) Disability and Society; (c) Health and Social Care in the Community; (d) Health Services Research, Journal of Integrated Care; (e) Journal of Health Services Research & Policy; (f) International Journal of Mental Health Systems; and (g) International Journal of Mental Health Systems. Key terms were used to search these journals resulting in the addition of two titles to full‐text screen (Appendix 1).

5.3. Data collection and analysis

5.3.1. Data extraction and study coding procedures

As outlined in the protocol, titles were reviewed initially in Endnote by the lead author to remove any studies which were clearly irrelevant (e.g., non‐human or pharmaceutical studies). However, due to the very large number of search results (n = 82,274 after duplicates and non‐relevant grey literature excluded), an extensive, thorough and transparent ‘results refinement process’ was developed. In summary, this included a three‐part process of (a) automatic text mining; (b) a failsafe check (to catch any studies inadvertently removed); and (c) a manual title screen. This process is detailed in Appendix 2. Excluded studies can be seen in Appendix 5.