1. PLAIN LANGUAGE SUMMARY

1.1. Bystander programs increase bystander intervention but no effect on perpetrating sexual assault

Bystander sexual assault prevention programs have beneficial effects on bystander intervention but there is no evidence of effects on sexual assault perpetration. Effects on knowledge and attitudes are inconsistent across outcomes.

1.2. What is this review about?

Sexual assault is a significant problem among adolescents and college students across the world. One promising strategy for preventing these assaults is the implementation of bystander sexual assault prevention programs, which encourage young people to intervene when witnessing incidents or warning signs of sexual assault. This review examines the effects bystander programs have on knowledge and attitudes concerning sexual assault and bystander behavior, bystander intervention when witnessing sexual assault or its warning signs, and participants’ rates of perpetration of sexual assault.

What is the aim of this review?

This Campbell systematic review examines the effects of bystander programs on knowledge and attitudes concerning sexual assault and bystander intervention, bystander intervention when witnessing sexual assault or its warning signs, and the perpetration of sexual assault. The review summarizes evidence from 27 high‐quality studies, including 21 randomized controlled trials.

2. WHAT ARE THE MAIN FINDINGS OF THIS REVIEW?

2.1. What studies are included?

This review includes studies that evaluate the effects of bystander programs for young people on (a) knowledge and attitudes concerning sexual assault and bystander intervention, (b) bystander intervention behavior when witnessing sexual assault or its warning signs, and (c) perpetration of sexual assault. Twenty‐seven studies met the inclusion criteria. These included studies span the period from 1997 to 2017 and were primarily conducted in the USA (one study was conducted in Canada and one in India). Twenty‐one studies were randomized controlled trials and six were high quality quasi‐experimental studies.

2.2. Do bystander programs have an effect on knowledge/attitudes, on bystander intervention, or on sexual assault perpetration?

Bystander programs have an effect on knowledge and attitudes for some outcomes. The most pronounced beneficial effects are on rape myth acceptance and bystander efficacy outcomes. There are also delayed effects (i.e., 1 to 4 months after the intervention) on taking responsibility for intervening/acting, knowing strategies for intervening, and intentions to intervene outcomes. There is little or no evidence of effects on gender attitudes, victim empathy, date rape attitudes, and on noticing sexual assault outcomes.

Bystander programs have a beneficial effect on bystander intervention. There is no evidence that bystander programs have an effect on participants’ rates of sexual assault perpetration.

3. WHAT DO THE FINDINGS OF THIS REVIEW MEAN?

The United States 2013 Campus Sexual Violence Elimination (SaVE) Act requires postsecondary educational institutions participating in Title IX financial aid programs to provide incoming college students with sexual violence prevention programming that includes a component on bystander intervention.

Bystander programs have a significant effect on bystander intervention. But there is no evidence that these programs have an effect on rates of sexual assault perpetration. This suggests that bystander programs may be appropriate for targeting the behavior of potential bystanders but may not be appropriate for targeting the behavior of potential perpetrators.

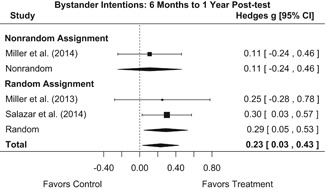

Beneficial effects of bystander programs on bystander intervention were diminished by 6 months post‐intervention. Thus, booster sessions may be needed to yield any sustained effects.

There are still important questions worth further exploration. Namely, more research is needed to investigate the underlying causal mechanisms of program effects on bystander behavior (e.g., to model relationships between specific knowledge/attitude effects and bystander intervention effects), and to identify the most effective types of bystander programs (e.g., using randomized controlled trials to compare the effects of two alternate program models). Additionally, more research is needed in contexts outside of the USA so that researchers can better understand the role of bystander programs across the world.

4. HOW UP‐TO‐DATE IS THIS REVIEW?

The review authors searched for studies up to June 2017. This Campbell systematic review was submitted in October 2017, revised in October 2018, and published January 2019.

5. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY/ABSTRACT

5.1. Background

5.1.1. Sexual assault among adolescents and college students

Sexual assault is a significant problem among adolescents and college students in the United States and globally. Findings from the Campus Sexual Assault study estimated that 15.9% of college women had experienced attempted or completed sexual assault (i.e., unwanted sexual contact that could include sexual touching, oral sex, intercourse, anal sex, or penetration with a finger or object) prior to entering college and 19% had experienced attempted or completed sexual assault since entering college (Krebs, Lindquist, Warner, Fisher, & Martin, 2009). Similar rates have been reported in Australia (Australian Human Rights Commission, 2017), Chile (Lehrer, Lehrer, & Koss, 2013), China (Su, Hao, Huang, Xiao, & Tao, 2011), Finland (Bjorklund, Hakkanen‐Nyholm, Huttunen, & Kunttu, 2010), Poland (Tomaszewska & Krahe, 2018), Rwanda (Van Decraen, Michielsen, Herbots, Van Rossem, & Temmerman, 2012), Spain (Vázquez, Torres, & Otero, 2012), and in a global survey of countries in Africa, Asia, and the Americas (Pengpid & Peltzer, 2016).

5.1.2. The bystander approach

One promising strategy for preventing sexual assault among adolescents and young adults is the implementation of bystander programs, which encourage young people to intervene when witnessing incidents or warning signs of sexual assault. Bystander programs seek to sensitize young people to warning signs of sexual assault, create attitudinal changes that foster bystander responsibility for intervening (e.g., creating empathy for victims), and build requisite skills and knowledge of tactics for taking action (Banyard, 2011; Banyard, Plante, & Moynihan, 2004; Burn, 2009; McMahon & Banyard, 2012). Many of these programs are implemented with large groups of adolescents or college students in the format of a single training/education session (e.g., as part of college orientation). However, some programs use broader implementation strategies, such as advertising campaigns that post signs across college campuses to encourage students to act when witnessing signs of violence.

By treating young people as potential allies in preventing sexual assault, bystander programs have the capacity to be less threatening than traditional sexual assault prevention programs, which tend to address young people as either potential perpetrators or victims of sexual violence (Burn, 2009; Messner, 2015; [Jackson] Katz, 1995). Instead of placing emphasis on how young people may modify their individual behavior to either respect the sexual boundaries of others or reduce their personal risk for being sexually assaulted, bystander programs aim to foster prerequisite knowledge and skills for intervening on behalf of potential victims. Thus, by treating young people as part of the solution to sexual assault, rather than part of the problem, bystander programs may limit the risk of defensiveness or backlash among participants (e.g., decreased empathy for victims, increased rape myth acceptance; Banyard et al., 2004; Katz, 1995).

5.2. Objectives

The overall objective of this systematic review and meta‐analysis was to examine what effects bystander programs have on preventing sexual assault among adolescents and college students. More specifically, this review addressed three objectives.

-

1.

The first objective was to assess the overall effects (including adverse effects), and the variability of the effects, of bystander programs on adolescents’ and college students’ attitudes and behaviors regarding sexual assault.

-

2.

The second objective was to explore the comparative effectiveness of bystander programs for different profiles of participants (e.g., mean age of the sample, education level of the sample, proportion of males/females in the sample, proportion of fraternity/sorority members in the sample, proportion of athletic team members in the sample).

-

3.

The third objective was to explore the comparative effectiveness of different bystander programs in terms of gendered content and approach (e.g., conceptualizing sexual assault as a gendered or gender‐neutral problem, mixed‐ or single‐sex group implementation).

5.3. Search methods

Candidate studies were identified through searches of electronic databases, relevant academic journals, and gray literature sources. Gray literature searches included contacting leading authors and experts on bystander programs to identify any current/ongoing research that might be eligible for the review, screening bibliographies of eligible studies and relevant reviews to identify additional candidate studies, and conducting forward citation searches (searches for reports citing eligible studies) using the website Google Scholar.

5.4. Selection criteria

To be included in the review studies had to meet eligibility criteria in the following domains: types of study, types of participants, types of interventions, types of outcome measures, duration of follow‐up, and types of settings.

5.4.1. Types of studies

To be eligible for inclusion in the review, studies must have used an experimental or controlled quasi‐experimental research design to compare an intervention group (i.e., students assigned to a bystander program) with a comparison group (i.e., students not assigned to a bystander program).

5.4.2. Types of participants

The review focused on studies that examined outcomes of bystander programs that targeted sexual assault and were implemented with adolescents and/or college students in educational settings. Eligible participants included adolescents enrolled in grades 7 through 12 and college students enrolled in any type of undergraduate postsecondary educational institution. The mean age of samples could be no less than age 12 and no greater than age 25.

5.4.3. Types of interventions

Eligible intervention programs were those that approached participants as allies in preventing and/or alleviating sexual assault among adolescents and/or college students. Some part of the program had to focus on ways that cultivate willingness for a person to respond to others who are at risk for sexual assault. All delivery formats were eligible for inclusion (e.g., in‐person training sessions, video programs, web‐based training, and advertising/poster campaigns). There were no intervention duration criteria for inclusion.

Eligible comparison groups must have received no intervention services targeting bystander attitudes/behavior or sexual assault.

5.4.4. Types of outcome measures

We included studies that measured the effects of bystander programs on at least one of the following primary outcome domains:

-

1.

General attitudes toward sexual assault and victims (e.g., victim empathy, rape myth acceptance).

-

2.

Prerequisite skills and knowledge for bystander intervention as defined by Burn (2009) (e.g., noticing sexual assault or its warning signs, identifying a situation as appropriate for intervention, taking responsibility for acting/intervening, and knowing strategies for helping/intervening).

-

3.

Self‐efficacy with regard to bystander intervention (e.g., respondents’ confidence in their ability to intervene).

-

4.

Intentions to intervene when witnessing instances or warning signs of sexual assault.

-

5.

Actual intervention behavior when witnessing instances or warning signs of sexual assault.

-

6.

Perpetration of sexual assault (i.e., participants’ rates of perpetration).

5.4.5. Duration of follow‐up

Studies reporting follow‐ups of any duration were eligible for inclusion. When studies reported outcomes at more than one follow‐up wave, each wave was coded and identified by its reported duration. Follow‐ups of similar durations were analyzed together.

5.4.6. Types of settings

The review focused on studies that examined outcomes of bystander programs that targeted sexual assault and were implemented with adolescents and/or college students in educational settings. Eligible educational settings included secondary schools (i.e., grades 7–12) and colleges or universities. There were no geographic limitations on inclusion criteria. Research conducted in any country was eligible.

5.5. Data collection and analysis

5.5.1. Selection of studies

Once candidate studies were identified, two reviewers independently screened each study title and abstract for eligibility; disagreements between reviewers were resolved by discussion and consensus. Potentially eligible studies were then retrieved in full text, and these full texts were reviewed for eligibility, again using two independent reviewers.

5.5.2. Data extraction and management

Two reviewers independently double‐coded all included studies, using a piloted codebook. Coding disagreements were resolved via discussion and consensus. The primary categories for coding were as follows: participant demographics and characteristics (e.g., age, gender, education level, race/ethnicity, athletic team membership, fraternity/sorority membership); intervention setting (e.g., state, country, secondary or postsecondary institution, mixed‐ or single‐sex group); study characteristics (e.g., attrition, duration of follow‐up, study design, participant dose, sample N); outcome construct (e.g., type, description of measure); and outcome results (e.g., timing at measurement, baseline, and follow‐up means and standard deviations or proportions).

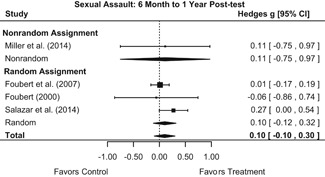

5.5.3. Measures of treatment effect

During the coding process, relevant summary statistics (e.g., means and standard deviations, proportions, observed sample sizes) were extracted from research reports to calculate effect sizes. Effect sizes were reported as standardized mean differences (SMD), adjusted for small sample size (Hedges’ g). Positive effect size values (i.e., greater than 0) indicate a beneficial outcome for the bystander intervention group.

5.5.4. Data synthesis

Intervention effects for each outcome construct were synthesized via meta‐analyses using random‐effects inverse variance weights. All statistical analyses were conducted with the metafor package in R. Synthesis results are displayed using forest plots. Mean effect sizes are reported with their 95% confidence intervals.

5.6. Results

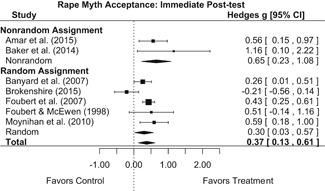

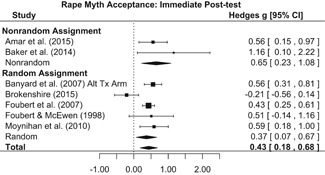

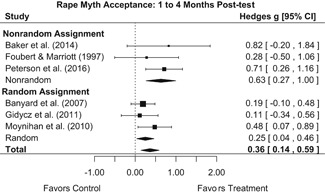

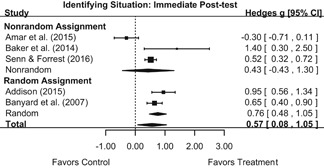

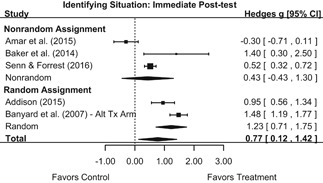

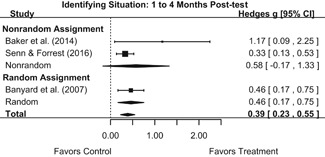

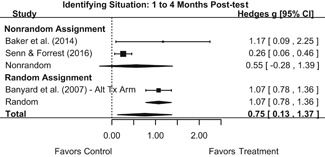

5.6.1. Objective 1: Effects on knowledge, attitudes, and behavior

Knowledge/Attitudes

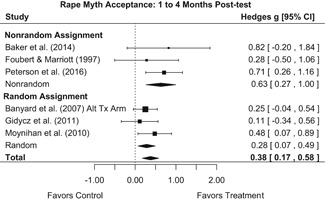

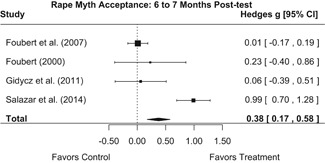

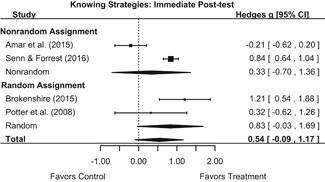

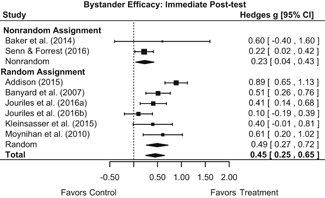

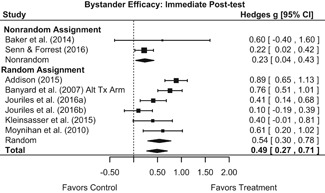

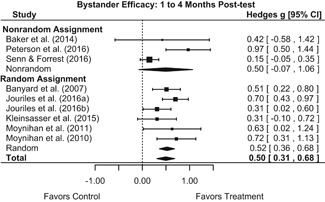

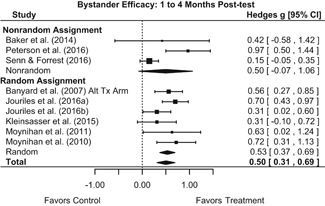

Effects for knowledge and attitude outcomes varied widely across constructs. The most pronounced beneficial effect in this domain was on rape myth acceptance. The effect for this outcome was immediate and sustained across all reported follow‐up waves (i.e., from immediate posttest to 6‐ to 7‐month post‐intervention). Intervention effects on bystander efficacy were also fairly pronounced, with an effect observed at both immediate posttest and 1‐ to 4‐month post‐intervention. A significant effect was not observed for this outcome 6 months post‐intervention; however, this should be interpreted with caution, as only one study reported bystander efficacy effects at this follow‐up period.

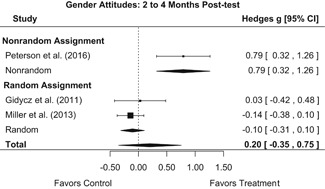

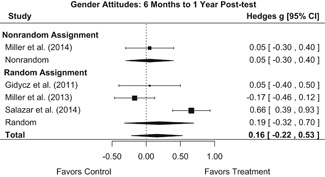

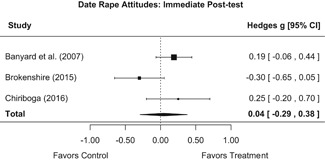

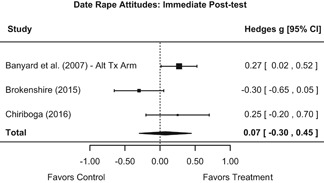

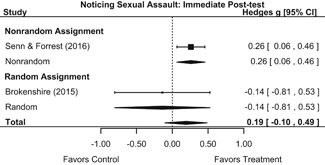

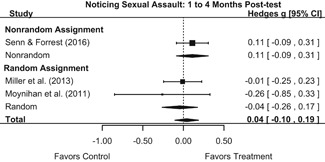

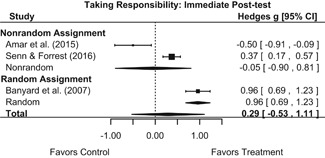

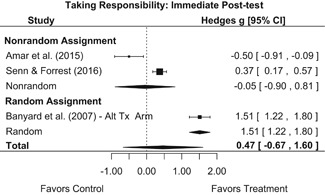

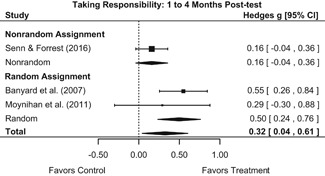

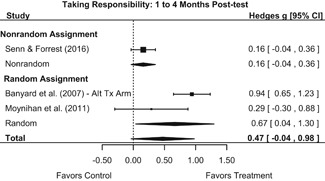

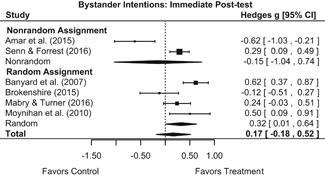

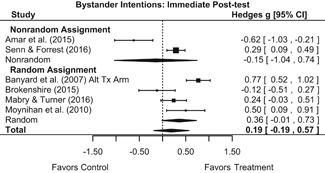

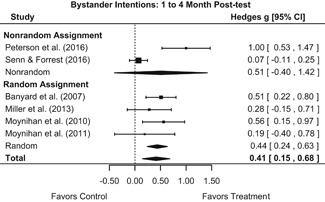

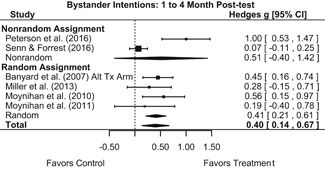

Effects on other knowledge and attitude outcomes were either delayed or unobserved. Intervention effects on taking responsibility for intervening or acting, knowing strategies for intervening, and intentions to intervene were nonsignificant at immediate posttest, but significant and beneficial by 1‐ to 4‐month post‐intervention. We found limited or no evidence of significant intervention effects on gender attitudes, victim empathy, date rape attitudes, and noticing sexual assault.

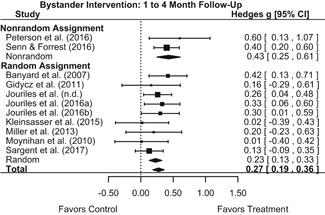

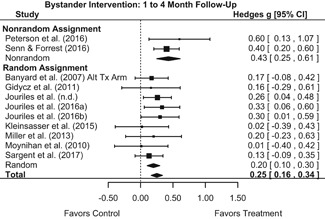

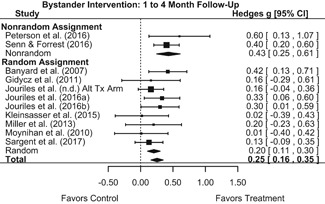

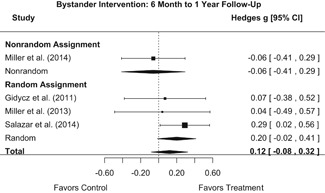

Behavior

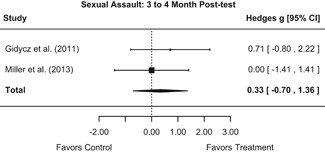

The results indicated that bystander programs have a beneficial effect on bystander intervention behavior. However, this effect, which was observed at 1‐ to 4‐month post‐intervention, was not statistically significant at 6 months post‐intervention. Bystander programs did not have a significant effect on sexual assault perpetration.

5.6.2. Objective 2: Effects for different participant profiles

We had planned to conduct moderator analyses to assess a wide range of participant characteristics as potential effect size moderators. However, our review only yielded a sufficient number of studies (n ≥ 10) to conduct moderator analyses for the bystander intervention outcome domain. The results indicated that mean age, education level, and proportion of males/female were not statistically significant predictors of the magnitude of intervention effects.

5.6.3. Objective 3: Effects based on gendered content/implementation

We conducted moderator analyses to assess any differential effects of bystander programs on measured outcomes based on (a) the gender of perpetrators and victims in specific bystander programs and (b) whether programs were implemented in mixed‐ or single‐sex settings. Our review only produced a sufficient number of studies (n ≥ 10) to conduct such moderator analyses for the bystander intervention outcome domain. We found that neither of these measures was a significant predictor of the effectiveness of bystander programs on bystander intervention.

5.7. Authors’ conclusions

5.7.1. Implications for practice and policy

The overwhelming majority of eligible studies assessing the effects of bystander programs were conducted in the United States. This is not necessarily surprising considering that the United States has implemented public policy that encourages the implementation of such programs on college campuses. The United States 2013 Campus SaVE Act requires postsecondary educational institutions participating in Title IX financial aid programs to provide incoming college students with primary prevention and awareness programs addressing sexual violence. The Campus SaVE Act mandates that these programs include a component on bystander intervention. Currently, there is no comparable legislation regarding sexual assault among adolescents (e.g., mandating bystander programs in secondary schools).

Findings from this review indicate that bystander programs have beneficial effects on bystander intervention behavior. This review therefore provides important evidence of the effectiveness of mandated programs on college campuses. Additionally, results from the moderator analyses indicated that the effects on bystander intervention are similar for adolescents and college students, which suggests that early implementation of bystander programs (i.e., in secondary schools with adolescents) may be warranted.

Importantly, although we found that bystander programs had a significant effect on bystander intervention behavior, there was no evidence that these programs had an effect on participants’ sexual assault perpetration. Although most bystander sexual assault prevention programs aim to shift attitudes in the hopes of preventing sexual assault perpetration, this review provided no evidence that these programs decrease participants’ perpetration rates. This suggests that bystander programs may be appropriate for targeting bystander behavior but may not be appropriate for targeting the behavior of potential perpetrators. Additionally, effects of bystander programs on bystander intervention diminished 6‐month post‐intervention. Thus, booster sessions may be needed to yield any sustained intervention effects.

5.7.2. Implications for research

Findings from this review suggest there is a fairly strong body of research assessing the effects of bystander programs on attitudes and behaviors. However, there are important questions worth further exploration.

First, according to one prominent logic model, bystander programs promote bystander intervention by fostering prerequisite knowledge and attitudes (Burn, 2009). Our meta‐analysis provides inconsistent evidence of the effects of bystander programs on knowledge and attitudes, but promising evidence of short‐term effects on bystander intervention behavior. These results cast uncertainty on the proposed relationship between knowledge/attitudes and bystander behavior. However, our methods do not permit any formal evaluation of this relationship. The field's understanding of the causal mechanisms of program effects on bystander behavior would benefit from further analysis (e.g., path analysis mapping relationships between specific knowledge/attitude effects and bystander intervention).

Second, bystander programs exhibit a great deal of content variability, most notably in framing sexual assault as a gendered or gender‐neutral problem. That is, bystander programs tend to adopt one of two main approaches to addressing sexual assault: (a) they present sexual assault as a gendered problem (overwhelmingly affecting women) or (b) they present sexual assault as a gender‐neutral problem (affecting women and men alike). Differential effects of these two types of programs remain largely unexamined. Our analysis indicated that (a) the sex of victims/perpetrators presented in interventions (i.e., portrayed in programs as gender neutral or male perpetrator and female victim) and (b) whether programs were implemented in mixed‐ or single‐sex settings were not significant predictors of program effects on bystander intervention. However, these findings are limited to a single outcome and they should be considered preliminary, as they are based on a small sample (n = 11). The field's understanding of the differential effects of gendered versus gender neutral programs would benefit from the design and implementation of high‐quality primary studies that make direct comparisons between these two types of programs (e.g., randomized controlled trials [RCTs] comparing the effects of two active treatment arms that differ in their gendered approach).

Finally, as previously noted, all but two eligible studies were conducted in the United States. Thus, high‐quality studies conducted outside of the United States are needed to provide a global perspective on the efficacy of bystander programs.

6. BACKGROUND

6.1. The problem, condition, or issue

6.1.1. Sexual assault among adolescents and college students

Sexual assault is a significant problem among adolescents and college students in the United States and globally. Findings from the Campus Sexual Assault study estimated that 15.9% of American college women had experienced attempted or completed sexual assault (i.e., unwanted sexual contact that could include sexual touching, oral sex, intercourse, anal sex, or penetration with a finger or object) prior to entering college and 19% had experienced attempted or completed sexual assault since entering college (Krebs et al., 2009).

Similar rates have been reported in Australia (Australian Human Rights Commission, 2017), Chile (Lehrer et al., 2013), China (Su et al., 2011), Finland (Bjorklund et al., 2010), Poland (Tomaszewska & Krahe, 2018), Rwanda (Van Decraen et al., 2012), Spain (Vázquez et al., 2012), and in a global survey of countries in Africa, Asia, and the Americas (Pengpid & Peltzer, 2016).

These rates are problematic, as sexual assault in adolescence and/or young adulthood is associated with numerous adverse outcomes, including risk of repeated victimization, depressive symptomology, heavy drinking, and suicidal ideation (Exner‐ Cortens, Eckenrode, & Rothman, 2013; Cui, Ueno, Gordon, & Fincham, 2013; Halpern, Spriggs, Martin, & Kupper, 2009). Importantly, there is evidence that indicates that experiences of sexual assault during these two life phases are related as victimization and perpetration during adolescence, respectively, associated with increased risk of victimization and perpetration during young adulthood (Cui et al., 2013). Thus, early prevention efforts are of paramount importance.

Reviews of research on the effectiveness of programs designed to prevent sexual assault among adolescents and college students have noted both a dearth of high‐quality studies, such as RCTs and minimal evidence that these prevention programs have meaningful effects on young people's behavior (De Koker, Mathews, Zuch, Bastien, & Mason‐Jones, 2014; DeGue et al., 2014). Concerning the latter point, evaluations of such programs tend to measure attitudinal outcomes (e.g., rape supportive attitudes, rape myth acceptance) more frequently than behavioral outcomes (e.g., perpetration or victimization; Anderson & Whiston, 2005; Cornelius & Resseguie, 2007; DeGue et al., 2014). Additionally, findings from a meta‐analysis of studies assessing outcomes of college sexual assault prevention programs suggested that effects are larger for attitudinal outcomes than for the actual incidence of sexual assault (Anderson & Whiston, 2005).

6.2. The intervention

6.2.1. The bystander approach

Given this paucity of evidence regarding behavior change, it is imperative to identify effective strategies for preventing sexual assault among adolescents and young adults. One promising strategy is the implementation of bystander programs, which encourage young people to intervene when witnessing incidents or warning signs of sexual assault (e.g., controlling behavior, such as intervening with a would‐be perpetrator leading an intoxicated person into an isolated area). The strength of the bystander model lies in its emphasis on the role of peers in the prevention of violence. Peers are a salient influence on young people's intimate relationships (Adelman & Kil, 2007; Giordano, 2003). In some respects, this influence can be detrimental, as having friends involved in violent intimate relationships (i.e., characterized by sexual or physical violence) is a risk factor for becoming both a perpetrator and victim of violence (Arriaga & Foshee, 2004; Foshee, Benefield, Ennett, Bauman, & Suchindran, 2004; Foshee, Linder, MacDougall, & Bangdiwala, 2001; Foshee, Reyes, & Ennett, 2010; McCauley et al., 2013). However, peers can also have a positive impact on intimate relationships.

Young victims and perpetrators of violence are often reluctant to divulge their experience or to seek help (especially from adults), but when they do seek help they often seek it from their peers (Ashley & Foshee, 2005; Black, Tolman, Callahan, Saunders, & Weisz, 2008; Molidor & Tolman, 1998; Weisz, Tolman, Callahan, Saunders, & Black, 2007). Victims may trust their peers to provide a valuable source of support after an assault has occurred, and as such, peers have the potential to play a pivotal role in the prevention of sexual assault by intervening when they witness its warning signs. In fact, in a contemporary “hookup culture” adolescents and young adults are more likely to meet and socialize in groups than they are to date in pairs and, therefore, warning signs of assault are frequently exhibited in communal spaces (Bogle, 2007; 2008; England & Ronen, 2015; Molidor & Tolman, 1998; Wade, 2017). Thus, the social nature of intimate relationships during these life stages can make peers pivotal actors in the prevention of sexual assault.

However, the potential for peer intervention can be undermined by a general “bystander effect” that diffuses responsibility for action in group settings (Darley & Latane, 1968). To intervene as a witness to sexual assault, individuals must notice the event (or its warning signs), define the event as warranting action/intervention, take responsibility for acting (i.e., feel a sense of personal duty), and demonstrate a sufficient level of self‐efficacy (i.e., perceived competence to successfully intervene; Latane & Darley, 1969). Studies have indicated that, as witnesses to sexual assault, young people often fail to meet these criteria (Banyard, 2008; Bennett, Banyard, & Garnhart, 2014; Burn, 2009; Casey & Ohler, 2012; Exner & Cummings, 2011; McCauley et al., 2013; McMahon, 2010; Noonan & Charles, 2009), with males being less likely than females to intervene (Banyard, 2008; Burn, 2009; Edwards, Rodenhizer‐Stampfli, & Eckstein, 2015; Exner & Cummings, 2011; McMahon, 2010).

Thus, bystander programs seek to sensitize young people to warning signs of sexual assault, create attitudinal change that fosters bystander responsibility for intervening (e.g., creating empathy for victims), and build requisite skills/tactics for taking action (Banyard et al., 2004; Banyard, 2011; Burn, 2009; McMahon & Banyard, 2012). Many of these programs are implemented with large groups of adolescents or college students in the format of a single training/education session (e.g., as part of college orientation). However, some programs use broader implementation strategies, such as advertising campaigns where signs are posted across college campuses to encourage students to act when witnessing signs of violence. The bystander model was developed and popularized in the US but has been adapted for use in global contexts.

6.3. How the intervention might work

By treating young people as potential allies in preventing sexual assault, bystander programs have the potential to be less threatening than traditional sexual assault prevention programs, which tend to approach young people as either potential perpetrators or victims of sexual violence (Burn, 2009; [Jackson] Katz, 1995; Messner, 2015). Instead of placing emphasis on how young people may modify their individual behavior to either respect the sexual boundaries of others or reduce their personal risk for being sexually assaulted, bystander programs aim to foster prerequisite knowledge and skills for intervening on behalf of victims. Thus, by treating young people as part of the solution to sexual assault, rather than part of the problem, bystander programs limit the risk of defensiveness or backlash among participants (e.g., decreased empathy for victims, increased rape myth acceptance; Banyard et al., 2004; Katz, 1995).

In addition to encouraging young people to prevent sexual violence through bystander intervention, these programs may reduce the likelihood of participants committing sexual assault themselves. To illustrate, Katz (1995) describes the rationale behind the mentors in violence prevention (MVP) bystander program as follows: “rather than focus on men as actual or potential perpetrators (emphasis in original), we focus on them in their role as potential bystanders (emphasis in original). This shift in emphasis greatly reduces the participants’ defensiveness” (p. 168). In other words, young men may be more receptive to prevention programming, and thus less likely to commit sexual assault, when they are approached as part of the solution rather than part of the problem to sexual assault. Consistent with this line of reasoning, studies on the effects of bystander programs often measure participants’ rates of sexual assault as a program outcome (Foubert, 2000; Foubert, Newberry, & Tatum, 2007; Gidycz, Orchowski, & Berkowitz, 2011; Miller et al., 2013; Miller et al., 2014; Salazar, Vivolo‐Kantor, Hardin, & Berkowitz, 2014).

As outlined by Burn (2009) bystander programs are designed to promote the following prerequisites for intervention: noticing an event, identifying a situation as warranting intervention, taking responsibility for acting, and deciding how to help. This often involves educating young people about what constitutes sexual assault, portraying victims as worthy of assistance, and building skills necessary to intervene (e.g., providing strategies for what to do and say). Although most bystander programs share the common goal of promoting such prerequisites for intervention, their specific program content and framing of sexual assault varies.

Research has indicated that, relative to males, females are overwhelmingly the victims of sexual assault (Foshee, 1996; Gressard, Swahn, & Tharp, 2015; Harned, 2001; Howard, Wang, & Yan, 2007). Thus, the earliest bystander programs tended to apply a gendered perspective to the prevention of sexual assault among adolescents and college students. For example, Katz (1995) developed MVP with the goal of inspiring male college athletes to challenge sociocultural definitions of masculinity that equate men's strength with dominance over women. At the time of its inception, MVP was unique in its explicit focus on masculinity as well as its nonthreatening bystander approach that encouraged young men to intervene when witnessing acts (or warning signs) of violence against women. As Katz explained, MVP reduces young men's defensiveness to violence prevention efforts by focusing on men as potential bystanders to violence, rather than potential perpetrators of violence. In addition to reducing men's defensiveness to intervention efforts, this bystander approach emphasizes the point that “when men don't speak up or take action in the face of other men's abusive behavior toward women, that constitutes implicit consent of such behavior” (Katz, 1995, p. 168).

Since the inception of MVP a number of programs have emerged to address barriers to bystander intervention among adolescents and college students. Although they all share the common goal of inspiring bystanders to act in ways that prevent sexual assault, these programs exhibit a great deal of variation in scope pertaining to their target bystander populations (i.e., males and/or females, secondary school or college students), sex of victims, and gendered versus gender‐neutral approach. For example, some programs use a gendered approach by (a) critiquing gender norms that can promote violence against women and (b) encouraging males to intervene on behalf of female victims (e.g., MVP, see Katz, 1995). Others use a gender‐neutral approach to build a sense of community responsibility to intervene on behalf of both male and female victims of sexual assault (e.g., Bringing in the Bystander, see Banyard, Moynihan, & Crossman, 2009; Banyard, Moynihan, & Plante, 2007). One of the major differences between gendered and gender‐neutral bystander programs is that the former places socio‐cultural forces, such as gender norms, at the center of discussions of violence whereas the latter places the bystander, and individual cognitive processes when encountering violence, at the center of discussions of violence ([Jackson] Katz, Heisterkamp, & Fleming, 2011; Messner, 2015).

Comparing the effects of gendered and gender‐neutral programs has the potential to identify important determinants of the success of bystander programs. Although there is no empirical examination of the different effects of these programs, there are theoretical reasons to believe that each has the potential to be successful under certain conditions. Namely, gendered approaches to bystander education programs may be better suited to target socio‐cultural facilitators of sexual assault against women and address different patterns of bystander behaviors exhibited by males and females (Banyard, 2008; Burn, 2009; Exner & Cummings, 2011; Katz, Heisterkamp, & Fleming, 2011; [Jennifer] Katz, 2015; [Jennifer] Katz, Colbert, & Colangelo, 2015; McCauley et al., 2013; McMahon, 2010; Messner, 2015). On the other hand, gender‐neutral programs may have the benefit of deflecting the criticism that prevention programs utilizing a gendered approach are inherently anti‐male (Katz et al., 2011; Messner, 2015). Proponents of such programs assert that avoidance of such criticism is paramount to the success of sexual assault prevention programs. In their view, adolescents and young adults who are coming of age in a “post‐feminist” era may be likely to reject gendered explanations of sexual assault and, instead, may respond more positively to gender‐neutral programs that use inclusive language that can be applied to a broad range of victims and perpetrators (Barreto & Ellemers, 2005; Kettrey, 2016; Swim, Aikin, Hall, & Hunter, 1995).

6.4. Why it is important to do the review

Policymakers in the United States perceive bystander programs to be beneficial, as evidenced by the 2013 Campus SaVE Act's requirement that postsecondary educational institutions participating in Title IX financial aid programs provide incoming college students with primary prevention and awareness programs addressing sexual violence. The Campus SaVE Act mandates that these programs include a component on bystander intervention. Currently, there is no comparable legislation regarding sexual assault among adolescents (e.g., mandating bystander programs in secondary schools). This is an unfortunate oversight, as adolescents who experience sexual assault are at an increased risk of repeated victimization in young adulthood (Cui et al., 2013). Thus, the implementation of bystander programs in secondary schools not only has the potential to reduce sexual assault among adolescents but may also have the long‐term potential to reduce sexual assault on college campuses.

Findings from this systematic review will provide valuable evidence of the extent to which bystander programs, as mandated by the Campus SaVE Act, are effective in preventing sexual assault among college students. Additionally, by examining effects of these programs among adolescents, this review will provide educators and policy makers with information for determining whether such programs should be widely implemented in secondary schools.

Currently, there are no Campbell or Cochrane Collaboration Reviews evaluating the effects of bystander programs on sexual assault among adolescents and/or college students. Of modest relevance to the proposed review, the Campbell and Cochrane Collaboration libraries include meta‐analyses of the effects of more general programs (not bystander programs) designed to prevent or reduce relationship/dating violence among adolescents and/or young adults (De La Rue, Polanin, Espelage, & Pigott, 2014; Fellmeth, Heffernan, Nurse, Habibula, & Sethi, 2013). Both of these reviews reported violence outcomes as aggregate measures that do not distinguish sexual violence from other forms of violence. Although they each found some evidence of significant effects on knowledge or attitudes pertinent to violence, neither found evidence of significant effects on young people's behavior (i.e., rates of perpetration or victimization).

Two reviews published outside of the Campbell and Cochrane Collaboration libraries are of closer relevance to this review. These include a meta‐analysis of the effects of bystander programs on sexual assault on college campuses (Katz & Moore, 2013) and a narrative review of studies examining the effects of bystander programs on dating and sexual violence among adolescents and young adults (Storer, Casey, & Herrenkohl, 2015).

In what they called an “initial” meta‐analysis of experimental and quasi‐experimental studies published through 2011, Katz & Moore (2013) found moderate beneficial effects of bystander programs on participants' self‐efficacy and intentions to intervene, and small (but significant) effects on bystander behavior, rape‐supportive attitudes, and rape proclivity (but not perpetration). Effects were generally stronger among younger samples and samples containing a higher percentage of males. The stronger effect for younger participants (i.e., younger college students) suggests such programs may be particularly effective with adolescents.

In a narrative review of studies examining the effects of bystander programs on dating violence and sexual assault among adolescents and young adults, Storer et al. (2015) highlighted beneficial effects on bystander self‐efficacy and intentions but noted less evidence of beneficial effects on actual bystander behavior or perpetration of violence. While informative, each of these reviews has limitations. Katz & Moore's (2013) meta‐analysis focused exclusively on sexual assault on college campuses and did not examine effects of such programs among adolescents. Although Storer et al. (2015) focused on studies examining violence among both adolescents and young adults, their sample was limited in that it was exclusively comprised of peer‐reviewed articles (i.e., the sample explicitly excluded theses, dissertations, and other gray literature). Additionally, the authors specified no research design criteria for inclusion (i.e., the sample included low‐quality studies such as those utilizing single group pre‐ and post‐test designs), limiting the strength of their conclusions. Importantly, Storer et al. reported no meta‐analytic findings. Thus, to our knowledge there are currently no existing meta‐analyses examining the effects of bystander programs on attitudes and behaviors regarding sexual assault among both college students and adolescents. Additionally, Katz & Moore's early meta‐analysis only included studies published/reported through 2011 (2 years prior to the 2013 Campus SaVE Act) and did not evaluate program content as a moderator.

Our review examined the effects of bystander programs on attitudes (i.e., perceptions of violence/victims, self‐efficacy to intervene, and intentions to intervene) and behaviors (i.e., actual intervention behavior, perpetration) regarding sexual assault among adolescents and college students. Importantly, we present meta‐analytic findings to quantitatively assess the influence of moderators (e.g., gender composition of sample, mean age of sample, education level of sample, single‐ or mixed‐sex implementation, gendered content of program, fraternity/sorority membership, and athletic team membership) on the effects of bystander programs.

7. OBJECTIVES

7.1. The problem, condition or issue

The overall objective of this systematic review and meta‐analysis was to examine the effects bystander programs have on preventing sexual assault among adolescents and college students. More specifically, and given the study designs that were included, this review addressed three objectives.

-

1.

The first objective was to assess the overall effects (including adverse effects), and the variability of the effects, of bystander programs on adolescents' and college students' attitudes and behaviors regarding sexual assault. This included general attitudes toward violence and victims, prerequisite skills and knowledge to intervene, self‐efficacy to intervene, intentions/willingness to intervene when witnessing signs of sexual assault, actual intervention behavior, and perpetration of sexual assault.

-

2.

The second objective was to explore the comparative effectiveness of bystander programs for different profiles of participants (e.g., mean age of the sample, education level of the sample, proportion of males/females in the sample, proportion of fraternity/sorority members in the sample, and proportion of athletic team members in the sample).

-

3.

The third objective was to explore the comparative effectiveness of different bystander programs in terms of gendered content and approach (e.g., conceptualizing sexual assault as a gendered or gender‐neutral problem, mixed‐ or single‐sex group implementation).

8. METHODS

8.1. Criteria for considering studies for this review

8.1.1. Types of studies

To be eligible for inclusion in the review, studies must have used an experimental or controlled quasi‐experimental research design to compare an intervention group (i.e., students assigned to a bystander program) with a comparison group (e.g., students not assigned to a bystander program). We limited our review to such study designs because these typically have lower risk of bias relative to other study designs (e.g., single group designs). More specifically, we included the following designs:

-

1.

Randomized controlled trials: Studies in which individuals, classrooms, schools, or other groups were randomly assigned to intervention and comparison conditions.

-

2.

Quasi‐randomized controlled trials: Studies where assignment to conditions was quasi‐random, for example, by birth date, date of week, student identification number, month, or some other alternation method.

-

3.Controlled quasi‐experimental designs: Studies where participants were not assigned to conditions randomly or quasi‐randomly (e.g., participants self‐selected into groups). Given the potential selection biases inherent in these controlled quasi‐experimental design, we only included those that also met one of the following criteria:

-

a.Regression discontinuity designs: Studies that used a cutoff on a forcing variable to assign participants to intervention and comparison groups, and assessed program impacts around the cutoff of the forcing variable.

-

b.Studies that used propensity score or other matching procedures to create a matched sample of participants in the intervention and comparison groups. To be eligible for inclusion, these studies must have also provided enough statistical information to permit estimation of pretest effect sizes for the matched groups.

-

c.For studies where participants in the intervention and comparison groups were not matched, enough statistical information must have been reported to permit estimation of pretest effect sizes for at least one outcome measure.

-

a.

Consistent with Campbell Collaboration policies and procedures, studies using experimental and quasi‐experimental research designs were synthesized separately in the meta‐analyses, given that experimental study designs have the highest level of internal validity. Furthermore, we collected extensive data on the risk of bias and study quality of all eligible studies, which we attended to when interpreting the findings from the systematic review and meta‐analyses (described in greater detail below).

8.1.2. Types of participants

The review focused on studies that examined outcomes of bystander programs and target sexual assault and are implemented with adolescents and/or college students in educational settings. Eligible participants included adolescents enrolled in grades 7 through 12 and college students enrolled in any type of undergraduate postsecondary educational institution.

Eligible participant populations included studies that reported on general samples of adolescents and/or college students as well as studies using specialized samples such as those primarily consisting of college athletes, fraternity/sorority members, and single‐sex samples. Study samples primarily consisting of postgraduate students were ineligible for inclusion; the mean age of samples could be no less than 12 and no greater than 25 to be included in the review.

8.1.3. Types of interventions

Eligible intervention programs were those that approached participants as allies in preventing and/or alleviating sexual assault among adolescents and/or college students. Some part of the program had to focus on ways that cultivate willingness for a person to respond to others who are at risk for sexual assault. All delivery formats were eligible for inclusion (e.g., in‐person training sessions, video programs, web‐based training, and advertising/poster campaigns). There were no interventions duration criteria for inclusion.

Studies that reported bystander outcomes but did not meet the aforementioned intervention inclusion criterion were not eligible for inclusion. Additionally, studies that assessed outcomes of programs that aimed to facilitate pro‐social bystander behavior, but that did not explicitly include a component addressing sexual assault (e.g., programs to prevent bullying) were not eligible for inclusion.

Eligible comparison groups must have received no intervention services targeting bystander attitudes/behavior or sexual assault. Thus, treatment–treatment studies that compared outcomes of individuals assigned to a bystander program versus those assigned to a general sexual assault prevention program were not eligible for inclusion. Eligible comparison groups may have received a sham or attention treatment expected to have no effect on bystander outcomes or attitudes/behaviors regarding sexual assault.

8.1.4. Types of outcome measures

We included studies that measured the effects of bystander programs on at least one of the following primary outcome domains:

-

1.

General attitudes toward sexual assault and victims (e.g., victim empathy, rape myth acceptance).

-

2.

Prerequisite skills and knowledge for bystander intervention as defined by Burn (2009) (e.g., noticing sexual assault or its warning signs, identifying a situation as appropriate for intervention, taking responsibility for acting/intervening, knowing strategies for helping/intervening).

-

3.

Self‐efficacy with regard to bystander intervention (e.g., respondents' confidence in their ability to intervene).

-

4.

Intentions to intervene when witnessing instances or warning signs of sexual assault.

-

5.

Actual intervention behavior when witnessing instances or warning signs of sexual assault.

-

6.

Perpetration of sexual assault (i.e., rates of perpetration among individuals assigned to the treatment or comparison group of a study).

Depending on directionality, these outcomes capture both beneficial and adverse effects (e.g., increases or decreases in victim empathy, pro‐social bystander behavior, etc.) that are important to adolescents, college students, and decision‐makers alike.

Any outcome falling in these domains was eligible for inclusion. This includes outcomes measured with any form of assessment (e.g., self‐report, official/administrative report, observation, etc.) that could be summarized by any type of quantitative score (e.g., percentage, continuous variable, count variable, categorical variable, etc.). In the event that a particular study included multiple measures of a single construct category (e.g., two measures of rape myth acceptance or bystander intervention within a given study), we only included one outcome per study for that construct. We selected the most similar outcomes for synthesis within a construct category (described in detail below).

8.1.5. Duration of follow‐up

Studies reporting follow‐ups of any duration were eligible for inclusion. When studies reported more than one follow‐up wave, each wave was coded and identified by its reported duration. As described in more detail below, follow‐ups of similar durations were analyzed together.

8.1.6. Types of settings

The review focused on studies that examine outcomes of bystander programs and target sexual assault and are implemented with adolescents and/or college students in educational settings. Eligible educational settings included secondary schools (i.e., grades 7–12) and colleges or universities. Studies that assessed bystander programs implemented with adolescents and young adults outside of educational institutions (e.g., in community settings, military settings) were ineligible for inclusion in the review. There were no geographic limitations on inclusion criteria. Research conducted in any country was eligible.

8.2. Search methods for identification of studies

8.2.1. Search strategy

We identified candidate studies through searches of electronic databases, relevant academic journals, and gray literature sources. We also contacted leading authors and experts on bystander programs to identify any current/ongoing research that might be eligible for the review. Additionally, we screened the bibliographies of eligible studies and relevant reviews to identify additional candidate studies. We conducted forward citation searches (searches for reports citing eligible studies) using the website Google Scholar, as this database produces similar results to other search engines (e.g., Web of Science; Tanner‐Smith & Polanin, 2015) and is also more likely to locate existing gray literature. Our search was global in scope and attempted to identify studies of bystander programs implemented in any country.

8.2.2. Electronic searches

The prevention of sexual assault among college students and adolescents is a topic that spans multiple disciplines (e.g., sociology, psychology, education, and public health). Thus, we searched a variety of databases that are relevant to these fields. Search terms varied by database, but generally included two blocks of terms and appropriate Boolean or proximity operators, when allowed: blocks included terms that address the intervention and outcomes. We specifically searched the following electronic databases (hosts) in October 2016 and June 2017:

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL).

Cochrane Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE).

Education Resources Information Center (ERIC, via ProQuest).

Education Database (via ProQuest).

International Bibliography of the Social Sciences (IBSS, via ProQuest).

PsycINFO (via ProQuest).

PsycARTICLES (via ProQuest).

PubMed.

Social Services Abstracts (via ProQuest).

Sociological Abstracts (via ProQuest).

The strategy for searching electronic databases involved the use of search terms specific to the types of interventions and outcomes eligible for inclusion. Search terms for types of interventions included general terms for bystander programs as well as names of specific bystander programs (e.g., MVP). Search terms for types of outcomes included terms that are specific to measures of sexual violence (e.g., sexual assault) as well as more general terms that have the potential to identify studies that measure physical and/or sexual violence. Due to the overwhelming focus of bystander programs on adolescents and college students (aside from a few implementations with military samples) search terms did not limit initial results by the age or general characteristics of the target population.

The search terms and strategy for PsycINFO via ProQuest were as follows (terms were modified for other databases):

(AB,TI(“bystander”)) AND (AB,TI(“education” OR “program” OR “training” OR “intervention” OR “behavior” OR “attitude” OR “intention” OR “efficacy” OR “prosocial” OR “pro‐social” OR “empowered” OR “Bringing in the Bystander” OR “Green Dot” OR “Step Up” OR “Mentors in Violence Prevention” OR “MVP” OR “Know Your Power” OR “Hollaback” OR “Circle of 6” OR “That's Not Cool” OR “Red Flag Campaign” OR “Where Do You Stand” OR “White Ribbon Campaign” OR “Men Can Stop Rape” OR “The Men's Program” OR “The Women's Program” OR “The Men's Project” OR “Coaching Boys into Men” OR “Campus Violence Prevention Program” OR “Real Men Respect” OR “Speak Up Speak Out” OR “How to Help a Sexual Assault Survivor” OR “InterACT”)) AND (AB,TI(“sexual assault” OR “rape” OR “violence” OR “victimization”))

8.2.3. Searching other resources

We searched the tables of contents of current issues of journals that publish research on sexual violence. This included the following journals: Journal of Adolescent Health, Journal of Community Psychology, Journal of Family Violence, Journal of Interpersonal Violence, Psychology of Violence, Violence Against Women, and Violence and Victims. We searched these sources in October 2016 and June 2017.

We also conducted gray literature searches to identify unpublished studies that met inclusion criteria. This included searching electronic databases that catalog dissertations and theses, searching conference proceedings, and searching websites with content relevant to sexual assault and/or violence against women. We specifically searched the following gray literature sources in October 2016 and June 2017:

ProQuest Dissertations and Theses Global.

Clinical Trials Register (https://clinicaltrials.gov).

End Violence Against Women International ‐ conference proceedings (http://www.evawintl.org/conferences.aspx).

National Sexual Violence Resource Center website (nsvrc.org).

National Online Resource Center on Violence Against Women website (VAWnet.org).

Us Department of Justice Office on Violence Against Women website (www.justice.gov/ovw).

Center for Changing our Campus Culture website (www.changingourcampusculture.org).

Additionally, we searched reference lists of previous systematic reviews and meta‐analyses, CVs and websites of primary authors of eligible studies, and reference lists of eligible studies. We also conducted forward citation searches of all eligible studies.

8.3. Data collection and analysis

8.3.1. Selection of studies

Once candidate studies were identified in the literature search, each reference was entered into the project database as a separate record. Two reviewers then independently screened each study title and abstract and recorded their eligibility recommendation (i.e., ineligible or eligible for full‐text screening) into the pertinent database record. Disagreements between reviewers were resolved by discussion and consensus, and the final abstract screening decision was recorded in the database. Potentially eligible studies were then retrieved in full text and these full texts were reviewed for eligibility, again using two independent reviewers who recorded their eligibility recommendation (and, when applicable, rationale for an ineligibility recommendation). Disagreements between reviewers were again resolved via discussion and consensus and the final eligibility decision was recorded in the database. In cases where we could not determine eligibility due to missing information in a report, we contacted study authors for this information.

Throughout the search and screening process we maintained a document that included the number of unique candidate studies identified through various sources (e.g., electronic database searches, academic journal searches, and gray literature searches). We used the information in this record to create a PRISMA flow chart that reports the screening process (Moher et al., 2015). Additionally, we used the final screening decisions recorded in the meta‐analysis database to create a table that lists studies excluded during the full‐text screening phase along with the rationale for each exclusion decision.

8.3.2. Data extraction and management

Two reviewers independently double‐coded all included studies, using a piloted codebook (see Appendix). All coding was entered into an electronic database, with a separate record maintained for each independent coding of each study. Coding disagreements were resolved via discussion and consensus with final coding decisions maintained in a separate record. If data needed to calculate an effect size were missing from a report, we contacted the primary study authors for this information.

The primary categories for coding are as follows: participant demographics and characteristics (e.g., age, gender, education level, race/ethnicity, athletic team membership, fraternity/sorority membership); intervention setting (e.g., state, country, secondary or postsecondary institution, mixed‐ or single‐sex group); study characteristics (e.g., attrition, duration of follow‐up, study design, participant dose, sample N); outcome construct (e.g., type, description of measure); and outcome results (e.g., timing at measurement, baseline and follow‐up means and standard deviations or proportions).

8.3.3. Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

We assessed risk of bias in included studies using the Cochrane risk of bias tools for randomized studies (Higgins & Green, 2011) and nonrandomized studies (Sterne, Higgins, & Reeves, 2016). The Cochrane risk of bias tool for randomized studies assesses risk of bias in the following domains: random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants and personnel, blinding of outcome assessment, incomplete outcome data, selective reporting, and other bias. These domains are each rated as low, unclear, or high risk of bias.

The Cochrane risk of bias tool for nonrandomized studies, ROBINS‐I, requires that at the protocol stage of the review, two sets of items are determined: (a) confounding areas that are expected to be relevant to all or most studies in the review and (b) cointerventions that could be different between intervention groups with the potential to differentially impact outcomes. In our protocol, we anticipated the following confounding factors, which were coded in the risk of bias assessments for nonrandomized studies: gender, fraternity/sorority membership, athletic team membership, preintervention attitudes (e.g., victim empathy, rape myth acceptance), preintervention bystander measures (e.g., efficacy, intentions, behavior), and prior sexual assault victimization. Additionally, we anticipated the following cointerventions to have a potential impact on outcomes, and they were coded in the risk of bias assessments: general sexual assault prevention programs, dating violence prevention programs, and general bystander programs (not explicitly targeting sexual violence).

8.3.4. Measures of treatment effect

We extracted relevant summary statistics (e.g., means and standard deviations, proportions, observed sample sizes) to calculate effect sizes. We then used Wilson's (2013) online effect size calculator to calculate effect sizes. The overwhelming majority of studies reported continuous measures of treatment effects, so we used a SMD effect size metric with a small sample correction (i.e., Hedges' g). In the rare cases in which binary outcome measures were reported in included studies, we deemed these measures to represent the same underlying construct as continuous measures, as they typically relied on the same measurement tools as relevant continuous measures. Thus, we transformed any log odd ratio effect sizes available from binary measures into SMD effect sizes by entering the observed proportions and sample sizes into Wilson's (2013) online effect size calculator. All SMD effect sizes were coded such that positive values (i.e., greater than 0) indicate a beneficial outcome for the intervention group.

8.3.5. Unit of analysis issues

The unit of analysis of interest for this review was the individual (i.e., individual‐level attitudes and behaviors). Nine of the included studies used cluster randomized trial designs where participants were randomized into the intervention or comparison conditions at the group level (e.g., entire schools were assigned to a single condition), and inferences were made at the individual level. To correct for these unit of analysis errors, we followed the procedures outlined in the Cochrane Handbook (Higgins & Green, 2011) to inflate the standard errors of the effect sizes from these nine studies by multiplying them by the design effect:

where M is the average cluster size for a given study and ICC is the intracluster correlation coefficient for a given outcome. In cases where study authors did not report ICCs we used a liberal assumed value of 0.10. This value has been used in a past Campbell review that synthesizes attitude and behavior outcomes of dating/sexual violence prevention programs (De La Rue et al., 2014) and is supported by Hedges and Hedberg's (2007) research on ICCs in cluster randomized trials conducted in educational settings.

8.3.6. Dealing with missing data

When studies reported insufficient data to calculate effect sizes we contacted the primary authors to request the necessary information. This author query method was highly successful; there were only two cases in which we were unable to obtain sufficient data from study authors (see details below with search results).

8.3.7. Assessment of heterogeneity

We assessed and reported heterogeneity using the χ 2 statistic and its corresponding p value, as well as the I 2 and τ 2 statistics. We used the restricted maximum likelihood estimator for τ 2. When at least 10 studies were included in any given meta‐analysis, we also used mixed‐effect meta‐regression models to conduct moderator analyses. Moderators specified in the protocol included: (a) gendered content of the program, (b) mixed‐ or single‐sex group implementation, (c) gender composition of the sample, (d) education level of the sample (i.e., secondary school or college students), (e) mean age of the sample, (f) proportion of fraternity/sorority members in the sample, and (g) and proportion of athletic team members in the sample.

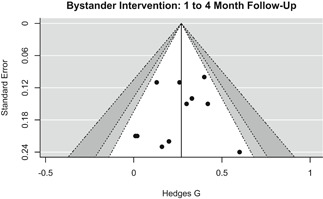

8.3.8. Assessment of reporting biases

To assess the potential of small study/publication bias, we used the contour enhanced funnel plot (Palmer, Peters, Sutton, & Moreno, 2008), Egger's regression test (Egger, Smith, Schneider, & Minder, 1997), and trim and fill analysis (Duval & Tweedie, 2000).

8.3.9. Data synthesis

We conducted all statistical analyses with the metafor package in R. We conducted meta‐analyses using random‐effects inverse variance weights and reported 95% confidence intervals along with all mean effect size estimates. We conducted and reported all meta‐analyses separately for RCTs and non‐RCTs. Additionally, we conducted all syntheses separately by outcome domain (i.e., attitudes toward sexual assault and victims, prerequisite skills and knowledge to intervene, bystander self‐efficacy, bystander intentions, bystander behavior, perpetration) and follow‐up timing. For most outcomes, follow‐up timing fell into the following categories: immediate post‐intervention, 1‐ to 4‐month post‐intervention, and 6 months to 1‐year post‐intervention. We displayed each synthesis using forest plots.

To minimize any potential bias in the meta‐analysis results due to effect size outliers, prior to conducting the meta‐analysis, we Winsorized any outlier effect sizes that fell more than two standard deviations away from the mean of the effect size distribution (Lipsey & Wilson, 2001). In such cases, we replaced the outlier effect size with the value that fell exactly two standard deviations from the mean of the distribution of effect sizes.

As noted previously, each meta‐analysis synthesized a set of statistically independent effect sizes. To ensure the statistical independence of effect sizes synthesized within any given meta‐analysis, we split all analyses by follow‐up timing and outcome domain. In the event that a particular study included multiple measures within a single outcome domain (e.g., two measures of rape myth acceptance within a given study), we only included one outcome per study for that construct. We selected the most similar outcomes for synthesis within a construct category. We adopted this approach for synthesizing statistically independent effect sizes given the small number of included studies and effect sizes available for synthesis. Other approaches that can be used to synthesize dependent effect sizes, such as robust variance estimation, require larger sample sizes for efficient parameter estimation than the sample sizes we had available for analysis (Hedges, Tipton, & Johnson, 2010; Tanner‐Smith & Tipton, 2014; Tipton, 2013).

8.3.10. Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We performed sub‐group analyses based on study design, synthesizing effect sizes (a) for RCTs alone, (b) for non‐RCTs alone, and (c) for RCTs and non‐RCTS combined. For each of these three subgroup analyses we assessed and reported heterogeneity using the χ 2 statistic and its corresponding p value, I 2, and τ 2. When at least ten studies were included in any given meta‐analysis, we used mixed‐effect meta‐regression models to conduct moderator analyses.

8.3.11. Sensitivity analysis

When at least 10 studies were included in a given meta‐analysis we conducted sensitivity analyses to examine whether study‐level attrition and high risk of bias (for each domain assessed with the risk of bias tools) were associated with effect size magnitude, using mixed‐effects meta‐regression models. Additionally, we conducted sensitivity analyses that removed any Winsorized effect sizes from the meta‐analysis, to assess whether this method for handling outliers may have substantively altered the review findings.

8.3.12. Interpretation of findings

To provide substantive interpretations of statistically significant mean effect sizes, we transformed the average SMD effect size back into an unstandardized metric using commonly reported scales/measures in the respective outcome domains. Namely, we multiplied the average SMD effect size by the standard deviation of a scale/measure that was frequently used in our meta‐analytic sample to yield an unstandardized difference in means. We aimed to select means and standard deviations from the most representative studies in our sample (e.g., RCTs and/or studies with larger sample sizes), but we recognize this is an imperfect process that requires generalization from a single study (for each significant outcome). We present these transformations in our Discussion section, at the conclusion of this report. Readers should be mindful of the fact that these are extrapolations intended to provide meaningful context to our findings, and that results are most accurately represented by the Hedges' g effect sizes.

9. RESULTS

9.1. Description of studies

9.1.1. Results of the search

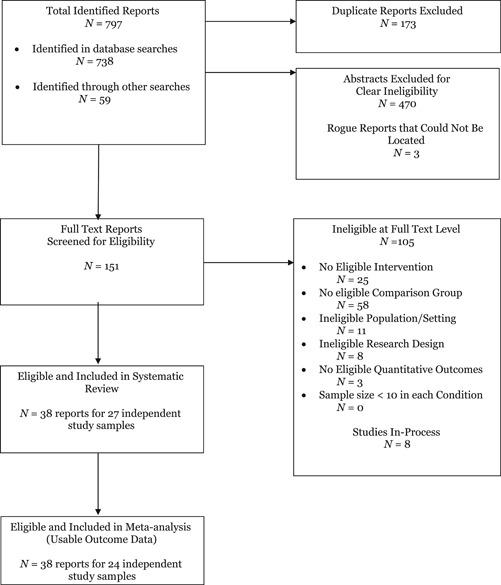

We conducted an initial literature search in October 2016 and an updated search in June 2017. Figure 1 outlines the flow of studies through the search and screening process. Through our initial and updated search we identified 797 reports. Of these reports, 738 were identified from searches of electronic databases, 19 from ClinicalTrials.gov, 1 from conference proceedings, 5 from website searches, 20 from reference lists of review articles, 1 from tables of contents searches, 3 from reference lists of eligible reports, 9 from CVs and websites of primary authors of eligible studies, and 1 from forward citation searching of eligible studies. After deleting duplicate reports and reports that were deemed ineligible through the abstract screening process 154 reports were deemed eligible for full‐text screening. Three of these reports could not be located; thus, we screened a total of 151 full‐text reports for eligibility.

Figure 1.

PRISMA study flow diagram

9.1.2. Included studies

Twenty‐seven independent studies summarized in 38 reports met inclusion criteria. One report (Jouriles, Rosenfield, Yule, Sargent, & McDonald, 2016b) presented findings from two independent studies. We coded these two studies separately and identified them as Jouriles et al. (2016a) and Jouriles et al. (2016b). Table 1 summarizes aggregate characteristics of all eligible studies. Twelve studies utilized random assignment at the individual level, nine studies utilized random assignment at the group level, and six studies utilized nonrandom assignment but reported pretest equivalence measures on at least one eligible outcome. More specific details of each individual study are summarized in Table A1 (see Figures and Tables Appendix). The majority of studies were conducted in the United States, with one study conducted in Canada and one conducted in India. This geographic pattern was primarily due to a paucity of research on bystander programs conducted outside of the United States and, to a lesser extent, to the failure of studies conducted outside the United States to meet the scope and methodological criteria for this review.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies (N = 27)

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Study design | ||

| Randomized – Individual | 12 | 44.44 |

| Randomized – Group | 9 | 33.33 |

| Nonrandomized | 6 | 22.22 |

| Comparison treatment | ||

| Active/Sham treatment | 9 | 33.33 |

| Inactive control | 18 | 66.67 |

| Peer reviewed | 22 | 81.48 |

| Funded | 18 | 66.67 |

| Study report year | ||

| 2017 | 2 | 7.41 |

| 2016 | 6 | 22.22 |

| 2015 | 4 | 14.81 |

| 2014 | 4 | 14.81 |

| 2012 | 1 | 3.70 |

| 2011 | 2 | 7.41 |

| 2010 | 1 | 3.70 |

| 2008 | 1 | 3.70 |

| 2007 | 2 | 7.41 |

| 2000 | 1 | 3.70 |

| 1998 | 1 | 3.70 |

| 1997 | 1 | 3.70 |

| Not reported | 1 | 3.70 |

| Educational setting | ||

| College/University | 22 | 81.48 |

| Secondary school | 5 | 18.52 |

| Country | ||

| United States | 25 | 92.59 |

| Canada | 1 | 3.70 |

| India | 1 | 3.70 |

Three studies were eligible for the review by methodological standards but did not report codable outcomes (Cook‐Craig et al. 2014; Darlington, 2014; Mabry & Turner, 2016). For example, in Cook‐Craig et al.'s (2014) study the unit of analysis was the school, not the individual. The study authors surveyed entire intervention and comparison schools across several years. As a result, the individual students composing the sample changed from wave to wave—and many students entering the school in later waves did not receive direct intervention. Darlington (2014) only reported within‐group pre‐post effect sizes. No between‐group data were reported and our attempt to obtain these data from the study author was unsuccessful. Mabry and Turner (2016) reported three‐way ANOVA findings from a three‐armed study (i.e., one eligible intervention group, one ineligible intervention group, and a comparison group). Our attempts to obtain data for the eligible intervention and comparison groups from the study author were unsuccessful. We therefore summarized each of these three studies in the systematic review but were unable to include results from those studies in any of the meta‐analyses.

Two studies (Banyard et al., 2007; Jouriles et al., n.d.) included two eligible intervention arms. Banyard et al. (2007) randomly assigned participants to one of three groups: (a) a no‐treatment control that only completed pre‐ and post‐intervention surveys, (b) an intervention group that was assigned to complete one 90‐min bystander program session, or (c) an intervention group that was assigned to complete three 90‐min bystander program sessions. Jouriles et al. (n.d.) randomly assigned participants to one of three groups: (a) a comparison “sham treatment” condition that presented material on study skills, (b) a computer‐delivered bystander program that participants completed independently, or (c) a computer‐delivered bystander program that participants completed in a lab under supervision. We handled these multiple‐arm studies by selecting the intervention groups that were most consistent with the intervention groups from the other studies in the sample (i.e., the single‐session treatment for Banyard et al. and the unmonitored treatment for Jouriles et al.). We contrasted these intervention groups with their comparison groups and included the calculated effect sizes in our main meta‐analyses. We then conducted sensitivity analyses in which we ran additional meta‐analyses that included effect sizes that compared the alternative intervention arms with the comparison arm.

9.1.3. Excluded studies

As shown in Figure 1, 105 reports were deemed ineligible after full‐text screening. These reports were ineligible because they either did not present an evaluation of an eligible intervention (n = 25), did not include an eligible comparison group (n = 58), did not involve an eligible population or setting (n = 11), did not involve an eligible research design (n =8), or did not measure any eligible outcomes (n = 3). Table A2 provides a brief description of each of these studies as well as the specific reasons for exclusion (see Figures and Tables Appendix).

9.2. Risk of bias in included studies

9.2.1. Randomized studies

Table 2 summarizes the risk of bias for the 21 randomized studies included in the systematic review. A large percentage of studies failed to report information that would permit assessment of risk of bias; these were coded as unclear risk. Among those studies reporting sufficient information, most exhibited low risk of bias in the domains of random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding of participants, and selective reporting. The majority of randomized studies (95.2%) exhibited high risk of bias in blinding of outcome assessment; these studies relied on self‐report outcome data. Although a slight majority of randomized studies (52.4%) exhibited low risk of bias in handling incomplete outcome data, one‐third exhibited high risk of bias. These studies with high risk of bias tended to exhibit uneven attrition between the intervention and comparisons groups or handled missing data inappropriately (e.g., mean imputation). The majority of randomized studies (81.0%) exhibited high risk of bias in the “other” domain; these studies tended to be conducted by researchers who either developed the intervention under evaluation or were closely affiliated with the developer of the intervention under evaluation.

Table 2.

Risk of bias of randomized studies

| Low risk | High risk | Unclear risk | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Random sequence generation | 8 | 38.1 | 0 | 0 | 13 | 61.9 |

| Allocation concealment | 3 | 14.3 | 0 | 0 | 18 | 85.7 |

| Blinding of participants | 1 | 4.8 | 0 | 0 | 20 | 95.2 |

| Blinding of outcome assessment | 1 | 4.8 | 20 | 95.2 | 0 | 0 |

| Incomplete outcome data | 11 | 52.4 | 7 | 33.3 | 3 | 14.3 |

| Selective reporting | 19 | 90.5 | 2 | 9.5 | 0 | 0 |

| Other bias | 3 | 14.3 | 17 | 81.0 | 1 | 4.8 |

Note: N = 21 studies.

9.2.2. Nonrandomized studies

Table 3 summarizes the risk of bias for the six nonrandomized studies included in the systematic review. Among the studies that reported group differences in confounding variables, most reported congruence between groups. This was often a product of the targeted population. For example, three studies targeted a specific gender (i.e., young men or young women) and two specifically targeted fraternity or sorority members. Only one study reported group differences between participants' previous experiences with co‐interventions. The remaining studies either failed to report this information (n = 3) or reported it at the aggregate level (n = 2).

Table 3.

Risk of bias of nonrandomized studies

| Even between groups | Uneven between groups | Not reported | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Confounding variables | ||||||

| Gender | 4 | 66.7 | 1 | 16.7 | 1 | 16.7 |

| Fraternity/sorority | 2 | 33.3 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 66.7 |

| Athlete | 1 | 16.7 | 0 | 0 | 5 | 83.3 |

| Preintervention attitudes | 3 | 50.0 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 50.0 |