Abstract

Background and purpose:

Tyrosinase enzyme has a key role in melanin biosynthesis by converting tyrosine into dopaquinone. It also participates in the enzymatic browning of vegetables by polyphenol oxidation. Therefore, tyrosinase inhibitors are useful in the fields of medicine, cosmetics, and agriculture. Many tyrosinase inhibitors having drawbacks have been reported to date; so, finding new inhibitors is a great need.

Experimental approach:

A variety of 6-hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalenone chalcone-like analogs (C1-C10) have been synthesized by aldol condensation of 6-hydroxy tetralone and differently substituted benzaldehydes. The compounds were evaluated for their inhibitory effect on mushroom tyrosinase by a spectrophotometric method. Moreover, the inhibition manner of the most active compound was determined by Lineweaver-Burk plots. Docking study was done using AutoDock 4.2. The drug-likeness scores and ADME features of the active derivatives were also predicted.

Results/Findings:

Most of the compounds showed remarkable inhibitory activity against the tyrosinase enzyme. 6-Hydroxy-2-(3,4,5-trimethoxybenzylidene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one (C2) was the most potent derivative amongst the series with an IC50 value of 8.8 μM which was slightly more favorable to that of the reference kojic acid (IC50 = 9.7 μM). Inhibitory kinetic studies revealed that C2 behaves as a competitive inhibitor. According to the docking results, compound C2 formed the most stable enzyme-inhibitor complex, mainly via establishing interactions with the two copper ions in the active site. In silico drug-likeness and pharmacokinetics predictions for the proposed tyrosinase inhibitors revealed that most of the compounds including C2 have proper drug-likeness scores and pharmacokinetic properties.

Conclusion and implications:

Therefore, C2 could be suggested as a promising tyrosinase inhibitor that might be a good lead compound in medicine, cosmetics, and the food industry, and further drug development of this compound might be of great interest.

Keywords: Anti-tyrosinase activity, Chalcones, Drug-likeness, Kinetic studies, Molecular docking, Tyrosinase inhibitor

INTRODUCTION

Tyrosinase (EC 1.14.18.1) is a dicopper-containing monooxygenase enzyme that is commonly distributed in bacteria, fungi, plants, and animals (1). It is the main regulatory enzyme responsible for the melanin biosynthesis catalyzing L-tyrosine oxidation (monophenolase activity) and L-DOPA oxidation to ortho-dopaquinone (diphenolase activity) (2,3). Tyrosinase enzyme has a significant role in medicinal, cosmetic, and agricultural fields (4). Tyrosinase inhibitors are applied as a remedy for skin disorders, such as hyperpigmentation diseases, age spots, melisma, and seborrheic (5,6), whereas tyrosinase activators protect the skin from UV damage due to an increase in melanogenesis (4,7).

Moreover, tyrosinase inhibition is suggested as a possible treatment for Parkinson’s and Huntington’s neurodegenerative diseases (8,9,10). Tyrosinase inhibitors also prevent vegetables and fruit browning that occurs as a result of enzymatic polyphenols oxidation (11,12).

A large number of structurally diverse naturally occurring and synthetic tyrosinase inhibitors have been reported (13,14,15,16,17), and some of them such as arbutin, hydroquinone, azelaic acid, L-ascorbic acid, ellagic acid, tranexamic acid, and kojic acid have been applied as skin-whitening agents with certain disadvantages. The use of reported tyrosinase inhibitors is limited due to their toxicity, chemical instability, allergic reactions, low lipophilicity, and lack of safety (18,19). Therefore, finding new tyrosinase inhibitors with ideal drug-likeness character and less toxicity is still a great necessity.

Chalcones (1,3-diaryl-2-propen-1-ones), which are abundantly found in plants, possess various pharmacological effects, such as antibacterial, antimalarial, antitubercular, antifungal, anticancer, antidiabetic, and anti-inflammatory activities (20,21,22,23). It was reported that hydroxyl- and alkoxy-substituted chalcones are potent tyrosinase inhibitors (24,25,26). Therefore, the target benzylidene-6-hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalenone derivatives bearing different substitutions were designed based on the structure of chalcones using the ring introduction strategy. Previously, we proved the anti-tyrosinase potential of some 6-methoxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalenone chalcone-like derivatives (27). Hence, as part of our ongoing investigation to find new and effective tyrosinase inhibitors and also to examine the structure-activity relationships (SAR), ten chalconoids having benzylidene-6-hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalenone structure were synthesized and screened for their inhibitory activity on the tyrosinase enzyme.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Instrumentations

Infrared (IR) spectra were acquired using a Perkin-Elmer spectrometer (Perkin-Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA). Melting points were obtained using a hot stage apparatus (Electrothermal, Essex, UK) and were uncorrected. Mass spectra were recorded on an Agilent spectrometer (Agilent technologies 9575c inert MSD, USA). Nuclear magnetic resonance spectra (1HNMR and 13CNMR) were achieved on a Burker-Avance DPX-300 MHz in DMSO-d6.

Chemicals

All chemicals and solvents used in this experiment were of analytical grade. Chemical reagents used in synthesis and biological sections, and mushroom tyrosinase (EC1.14.18.1) were purchased from Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA).

Synthesis of (E)-2-benzylidene-6-hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalenone derivatives

A solution of 6-hydroxy tetralone (1.00 mmol), p-toluenesulfonic acid (PTSA) (0.25 mmol), and corresponding aldehyde (1.00 mmol) were stirred in refluxing ethanol (10 mL) for 24 h. Reaction progress was monitored by thin-layer chromatography (TLC) using petroleum ether/ethyl acetate (70:30) as the mobile phase. Then, the reaction mixture was cooled and ethanol was reduced by vacuum evaporation. The resulting precipitate was filtered, recrystallized in ethanol, and washed with diethyl ether, petroleum ether, and cool ethanol.

(E)-6-hydroxy-2-(4-methoxybenzylidene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one (C1)

Yellow crystalline solid; yield: 80%; MP: 184-188 °C; 1HNMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz) δH (ppm): 2.80-2.84 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 3.01-3.03 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 3.71 (s, 3H, OCH3), 6.68 (s, 1H, H-5), 6.77 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-7), 7.01 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, H-3′,5′), 7.48 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, H-2′,6′), 7.61 (s, 1H, -C=CH-Ph), 7.84 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-8), 10.44 (s, 1H, OH). MS (EI), m/z (%): 279 ([M+-1], 100), 265 (20), 249 (18.6). IR (KBr) vmax (cm-1): OH, 3164; CH-aromatic, 2989.65; CH-aliphatic, 2838.38; C=O, 1604.

(E) - 6- hydroxy - 2- (3,4,5- trimethoxy-benzylidene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one (C2)

Light brown crystalline solid; yield: 52%; MP: 192-195 °C; 1HNMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz) δH (ppm): 2.80-2.86 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 3.06-3.10 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 3.70 (s, 3H, OCH3), 3.81 (s, 6H, OCH3), 6.68 (s, 1H, H-5), 6.76-6.81 (m, 3H, H-7, 2′,6′), 7.60 (s, 1H, -C=CH-Ph), 7.88 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-8), 10.46 (s, 1H, OH). MS (EI), m/z (%): 340 (M+, 100), 309 (83). IR (KBr) vmax (cm-1): OH, 3272; CH-aromatic, 2982; CH-aliphatic, 2912; C=O, 1648.

(E)-6-hydroxy-2-(2-methoxybenzylidene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one (C3)

Peach crystalline solid; yield: 81%; MP: 169-172 °C; 1HNMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz) δH (ppm): 2.79-2.83 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 2.90-2.93 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 3.82 (s, 3H, OCH3), 6.67 (s, 1H, H-5), 6.79 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, H-7), 7.00 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H, H-5′), 7.08 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 1H, H-3′), 7.32-7.40 (m, 2H, H-4′, 6′), 7.72 (s, 1H, -C=CH-Ph), 8.86 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, H-8), 10.46 (s, 1H, OH). MS (EI), m/z (%): 280 (M+, 9), 249 (100). IR (KBr) vmax (cm-1): OH, 3271; CH-aromatic, 2943; CH-aliphatic, 2841; C=O, 1606.

(E)-2-(3-ethoxy-4-hydroxybenzylidene)-6-hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one(C4)

Brown crystalline solid; yield: 84%; MP: 255-259 °C; 1HNMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz) δH (ppm): 1.34 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3H, OCH2CH3), 2.80-2.84 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 3.03-3.07 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 4.02-4.09 (q, J = 6.9 Hz, 2H, OCH2CH3), 6.67 (s, 1H, H-5), 6.77 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, H-7), 6.87 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-5′), 6.99 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-6′), 7.06 (s, 1H, H-2′), 7.58 (s, 1H, -C=CH-Ph), 8.83 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, H-8), 9.75 (s, 1H, OH), 10.46 (s, 1H, OH). MS (EI), m/z (%): 310 (M+, 100), 293 (24), 281 (51), 265 (30). IR (KBr) vmax (cm-1): OH, 3227; CH-aromatic, 2950; CH-aliphatic, 2849; C=O, 1639.

(E)-6-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxybenzylidene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one (C5)

Light brown crystalline solid; yield: 45%; P: 257-261 °C; 1HNMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz) δH (ppm): 2.82-2.84 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 3.00-3.02 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 6.67 (s, 1H, H-5), 6.77 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-7), 7.38 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, H-3′, 5′), 7.38 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 2H, H-2′,6′), 7.57 (s, 1H, -C=CH-Ph), 7.83 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-8), 9.92 (s, 1H, OH), 10.41 (s, 1H, OH). MS (EI), m/z (%): 265 ([M+-1], 100), 249 (20.4), 107 (23). IR (KBr) vmax (cm-1): OH, 3299; CH-aromatic, 2947; CH-aliphatic, 2845; C=O, 1603.

(E)-2-(3,4-dimethoxybenzylidene)-6-hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one (C6)

Brown crystalline solid; yield: 71%; MP: 201-204 °C; 1HNMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz) δH (ppm): 2.81-2.85 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 3.04-3.08 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 3.79 (s, 6H, OCH3), 6.68 (s, 1H, H-5), 6.78 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-7), 7.02 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, H-5′), 7.08-7.10 (m, 2H, H-2′,6′), 7.61 (s, 1H, -C=CH-Ph), 8.84 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-8), 10.42 (s, 1H, OH). MS (EI), m/z (%): 310 (M+, 100), 295 (52), 279 (48). IR (KBr) vmax (cm-1): OH, 3262; CH-aromatic, 2909; CH-aliphatic, 2838; C=O, 1648.

(E)-2-(4-chlorobenzylidene)-6-hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one (C7)

Purified by TLC, using petroleum ether:ethyl acetate (70:30) as the mobile phase. White crystalline solid; yield: 34%; MP: 201-205 °C; 1HNMR (DMSO-d6, 500 MHz) δH (ppm): 2.82-2.84 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 3.00-3.04 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 6.68 (s, 1H, H-5), 6.79 (d, 1H, J = 8.5 Hz, H-7), 7.48-7.52 (m, 4H, H-2′, 3′,5′, 6′), 7.60 (s, 1H, C=CH-Ph), 7.86 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H, H-8), 10.54 (s, 1H, OH). 13CNMR (DMSO-d6, 125 MHz) δC (ppm): 27.30, 28.76, 114.56, 115.42, 128.35, 129.15, 130.93, 131.78, 132.12, 133.67, 133.70, 134.96, 137.15, 146.64, 162.99 (C6), 185.65 (C=O). MS (EI), m/z (%): 284([M+], 83), 283 (100), 249 (43). IR (KBr) vmax (cm-1): OH, 3272; CH-aromatic, 2987; CH-aliphatic, 2912; C=O, 1648.

(E)-2-(3-chlorobenzylidene)-6-hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one (C8)

Purified by TLC, using petroleum ether:ethyl acetate (70:30) as the mobile phase. White crystalline solid; yield: 37%; MP: 199-202 °C; 1HNMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz) δH (ppm): 2.82-2.84 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 3.00-3.04 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 6.68 (s, 1H, H-5), 6.79 (d, 1H, J = 8.5 Hz, H-7), 7.45-7.59 (m, 5H, H-2′, 3′,5′, 6′and -C=CH-Ph), 7.86 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H, H-8), 10.47 (s, 1H, OH). 13CNMR (DMSO-d6, 75 MHz) δC (ppm): 27.17, 28.60, 114.42, 115.30, 125.40, 128.67, 128.75, 129.66, 130.78, 133.29, 133.71, 137.68, 138.16, 146.58, 162.88 (C6), 185.46 (C=O). MS (EI), m/z (%): 284 ([M+], 63), 283 (100), 249 (20), 162 (100). IR (KBr) vmax (cm-1): OH, 3272; CH-aromatic, 2987; CH-aliphatic, 2912; C=O, 1648.

(E)-6-hydroxy-2-(4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxy-benzylidene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one (C9)

Orange crystalline solid; yield: 49%; MP: 210-213 °C; 1HNMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz) δH (ppm): 2.82-2.86 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 3.08-3.12 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 3.80 (s, 6H, OCH3), 6.86 (s, 1H, H-5), 6.77,6.79 (dd, J = 8.4/2.4 Hz, 1H, H-7), 6.81 (s, 2H, H-2′,6′), 7.60 (s, 1H, -C=CH-Ph), 7.83 (d, J = 8.7 Hz, 1H, H-8), 9.78 (s, 1H, OH), 10.41 (s, 1H, OH). MS (EI), m/z (%): 326 (M+, 100), 295 (85). IR (KBr) vmax (cm-1): OH, 3271 cm-1; CH-aromatic, 2943; CH-aliphatic, 2841; C=O, 1650.

(E)- 2- (4- (dimethylamino) benzylidene) -6-hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one (C10)

Yellow crystalline solid; yield: 78%; MP: 211-214 °C; 1HNMR (DMSO-d6, 300 MHz) δH (ppm): 2.80-2.84 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 3.00-3.03 (m, 2H, dihydronaphthalenone-CH2), 3.11 (s, 6H, N(CH3)2), 6.69 (s, 1H, H-5), 6.78 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-7), 7.14 (d, J = 8.1 Hz, 2H, H-2′6′), 7.51-7.56 (m, 3H, H-3′,5′, -C=CH-Ph), 7.85 (d, J = 8.4 Hz, 1H, H-8), 9.66 (s, 1H, OH). MS (EI), m/z (%): 293 (M+, 100), 264 (15), 249 (14), 172 (26). IR (KBr) vmax (cm-1): OH, 3227; CH-aromatic, 2930; CH-aliphatic, 2899; C=O, 1639.

Tyrosinase inhibition assay

Mushroom tyrosinase inhibitory activity was assessed as reported in our previous studies (28-30). L-DOPA was used as the substrate. The diphenolase activity of tyrosinase was examined spectrophotometrically by detecting dopachrome formation at 475 nm. Stock solutions at 40 mM in DMSO were prepared for all the test samples and diluted to the required concentrations. In 96-well microplates, tyrosinase (10 mL, 0.5 mg/mL) was mixed with phosphate buffer (160 mL, 50 mM, pH = 6.8) and then the test sample (10 mL) was added. The mixture was pre-incubated at 28 °C for 20 min, then after L-DOPA solution (20 mL, 0.5 mM) was inserted into the wells. Kojic acid was applied as the positive control. Each experiment was done as three separate replicates. The inhibitory activity of the compounds was stated in terms of IC50 which is the concentration that inhibited 50% of the enzyme activity. The percentage inhibition ratio was assessed, using the following equation:

The IC50 values were achieved by creating a nonlinear regression curve, using CurveExpert software.

Determination of the inhibition type

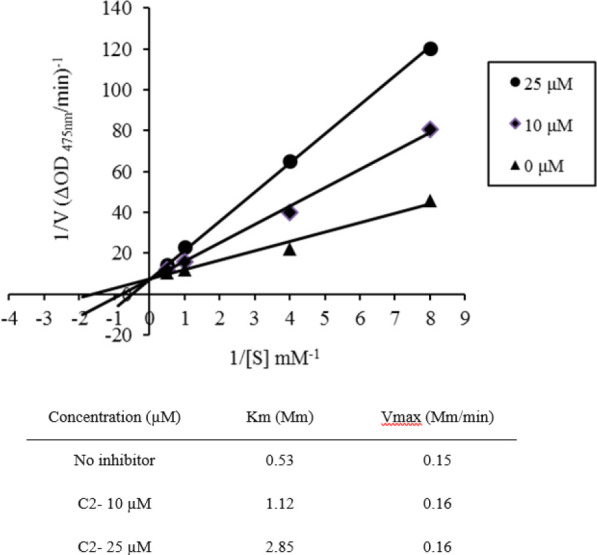

Derivative C2 as the most potent tyrosinase inhibitor was selected for the kinetic study. The inhibition type of the enzyme was assayed by Lineweaver-Burk plots of the inverse of velocities (1/V) versus the inverse of substrate (L-DOPA) concentrations 1/[S] mM-1. The inhibitor and substrate concentration ranges were 0-25 μM and 0.125-2.000 mM, respectively in all kinetic studies. Pre-incubation and measurement times were considered the same as defined in the tyrosinase inhibition assay protocol. Maximum initial velocity was determined from the initial linear portion of absorbance for 10 min after the addition of L-DOPA with one min interval. The Michaelis constant (Km) and the maximal velocity (Vmax) were calculated by the Lineweaver-Burk plot.

Computational analysis

in silico drug-likeness scores and pharmaco-kinetics predictions

The drug-likeness and pharmacokinetic properties of the compounds were predicted, using the preADMET online server (http://preadmet.bmdrc.org/).

Molecular docking analysis

The crystal structure of Agaricus bisporus tyrosinase (PDB ID: 2Y9X) was obtained from the RCSB Protein Databank (http://www.rcsb.org). The co-crystallized ligand (tropolone) and water molecules were removed from the crystal structure. Hydrogen atoms were added, non-polar hydrogens were merged and Gasteiger charges were calculated for the protein by using AutoDock Tools 1.5.4 (ADT). The ligand structures were drawn and minimized by HyperChem software. The ligands were prepared in PDBQT formats by assigning Gasteiger charges and setting the torsions degree using ADT. Grid box parametric dimension values were adjusted to 40 × 40 × 40 with 0.375 Å spacing. The binding site containing the two copper ions was selected for docking and the grids’ center was set on the tropolone’s binding site. Lamarckian genetic search algorithms were selected and the number of runs was adjusted to 100.

RESULTS

Compound synthesis

Many synthetic procedures have been reported for the benzylidene-tetralone derivatives (31,32,33). In this study, ten benzylidene-6-hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1-on derivatives (C1-C10) were synthesized by the aldol condensation reaction of 6-hydroxy tetralone (A) with different aromatic aldehydes (B) in the presence of PTSA as the catalyzer (Scheme 1). The chemical structures of the target derivatives were characterized using 1HNMR, MS, and IR

Scheme 1.

The synthetic procedure of benzylidene-6-hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1-on derivatives.

Biological studies

Mushroom tyrosinase inhibitory activity of 6-hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1-on chalcone-like derivatives

The inhibitory activity of target benzylidene-6-hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1-on compounds on mushroom tyrosinase was studied. Kojic acid was used as a reference agent and the results in terms of IC50 values are shown in Table 1. Due to the solubility problem of compound C8, it was not evaluated for the biological effect. Generally, results revealed that the majority of the compounds displayed antityrosinase activities at the tested concentrations. The anti-tyrosinase activities varied depending on the substitutions on the phenyl ring. Among the tested derivatives, compounds C2 and C3 bearing 3,4,5-trimethoxyphenyl and 2-methoxphenyl moieties were the dominant inhibitors with the IC50 values of 8.8 ± 1.8 and 11.1 ± 2.5 μM, respectively. C2 and C3 anti-tyrosinase activities were comparable to that of kojic acid (IC50 = 9.7 ± 1.3 μM). Other derivatives showed a lower tyrosinase inhibitory effect than kojic acid did. Compounds C1, C4, C6, and C7 possessing 4-methoxy, 3-methoxy-4-hydroxy, 3,4-dimethoxy, and 4-chloro substitutions on benzylidene, respectively, also exhibited good anti-tyrosinase activity (IC50=17.6 – 48.6 μM). Derivatives C5, C9, and C10 bearing 4-hydroxyphenyl, 4-hydroxy-3,5-dimethoxyphenyl and 4-(dimethylamino)phenyl moieties did not have any considerable activity at the tested concentrations.

Table 1.

Tyrosinase inhibitory activities of synthesized compounds. Values represent means ± SEM, n = 4.

| |||

|

| |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Compounds | R | Molecular weight | IC50 (μM) |

|

| |||

| C1 | 4-OCH3 | 280.3 | 17.6 ± 1.1 |

| C2 | 3,4,5-(OCH3)3 | 340.4 | 8.8 ± 1.8 |

| C3 | 2-OCH3 | 280.3 | 11.1 ± 2.5 |

| C4 | 3-OCH2CH3, 4-OH | 310.3 | 21.4 ± 3.1 |

| C5 | 4-OH | 266.3 | 48.6 ± 2.9 |

| C6 | 3,4-(OCH3)2 | 310.3 | 17.6 ± 2.4 |

| C7 | 4-Cl | 284.8 | 22.4 ± 3.1 |

| C8 | 3-Cl | 284.7 | Not determined |

| C9 | 4-OH, 3,5-(OCH3)2 | 326.3 | > 50 |

| C10 | 4-N(CH3)2 | 293.4 | >5 0 |

| Kojic acid | - | 142.1 | 9.7 ± 1.3 |

Kinetic studies of C2 derivative

The inhibition mode of the enzyme by the most potent derivative, C2, was assessed by Lineweaver-Burk plot analysis and the result is displayed in Fig. 1. The Lineweaver-Burk plot of 1/V versus 1/[S] showed a series of straight lines. Kinetic analysis of the enzyme in the presence of different concentrations of C2 indicated that while the concentration of the inhibitor was elevated, Km values increased and Vmax values remained constant. Therefore, it can be stated that derivative C2 inhibited the tyrosinase enzyme competitively.

Computational analysis results

Molecular docking analysis

Molecular docking of 6-hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1-on chalcone-like derivatives with mushroom tyrosinase enzyme (PDB ID: 2Y9X) was conducted to obtain some information into the binding modes and possible interactions of the derivatives in the binding site of the enzyme. Many researchers reported small-molecule docking into metalloproteins by autodock software (34,35). The enzyme-inhibitor complexes binding affinities are presented in Table 2. All the derivatives had more negative estimated free binding energies than tropolone and kojic acid as the co-crystallized ligand and the reference drug, respectively. Compounds C2, C8, and C3 possessing the most negative binding energies (-7.46, -7.44, and -7.28 kcal/mol, respectively) formed the most stable enzyme-inhibitor complexes. The binding models of compounds showed the most favored binding energies (C2 and C8) and the rest of the compounds within the tyrosinase active site are depicted in Fig. 2. Docking results revealed that in all of the proposed compounds, the hydroxyl group of dihydronaphthalenone core established tough bonds with the copper ions in the binding pocket. The binding mode of C2 and C8 was similar; however, it was different from the other compounds.

Table 2.

Docking results of 6-hydroxy-3, 4 - dihydronaphthalen-1- on chalcone - like derivatives having anti-tyrosinase activity, and kojic acid into the mushroom tyrosinase active site.

| Compounds | ΔG (kcal/mol) | Ki (μM) |

|---|---|---|

| C1 | -6.35 | 18.83 |

| C2 | -7.46 | 3.38 |

| C3 | -7.28 | 3.86 |

| C4 | -6.35 | 21.98 |

| C5 | -6.39 | 20.83 |

| C6 | -6.40 | 20.35 |

| C7 | -6.78 | 10.70 |

| C8 | -7.44 | 3.49 |

| C9 | -6.17 | 30.14 |

| C10 | -6.50 | 17.20 |

| Tropolone | -4.36 | 0.61 × 103 |

| Kojic acid | -3.57 | 2.40 × 103 |

Fig. 1.

Lineweaver-Burk plots for tyrosinase inhibition in the presence of C2 compound. The reciprocal tyrosinase inhibitory activity was plotted against the reciprocal substrate concentration (double reciprocal plot, n = 3). Concentrations of C2 were 0, 10, and 25 μM, while substrate L-DOPA concentrations were 0.125, 0.250, 1.000, and 2.000 mM. Km is the Michaelis-Menten constant and Vmax is the maximum reaction velocity.

Fig. 2.

(A) The docking interactions and (B) binding orientation of compounds C2 (cyan) and C8 (yellow) within the tyrosinase active site. (C) The docking interactions and (D) binding orientation of compounds C1 (yellow), C3 (blue), C4 (purple), C5 (yellow), C6 (cyan), C7 (pink), C9 (green), and C10 (brown) within the tyrosinase active site.

in silico drug-likeness and ADMET investigation results

Drug-likeness scores (including Lipinski rule of five, CMC like rule, lead like rule, MDDR like rule, and WDI like rule) and pharmacokinetic properties (including human intestinal absorption, in vitro Caco-2 cell permeability, in vitro MDCK cell permeability, in vitro plasma protein binding and, in vivo blood-brain barrier penetration) were predicted for the derivatives exhibited good tyrosinase inhibitory activity, using PreADMET online server (www.preadmet.bmdrc.org). Drug-likeness and ADMET calculation results are presented in Tables 3 and 4, respectively.

Table 3.

in silico Lipinski rule of five, lead like rule, CMC like rule, MDDR like rule, and WDI like rule prediction for 6-hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1-on chalcone-like derivatives possessing tyrosinase inhibitory activity.

| Compounds | CMC like rule | Lead like rule | MDDR like rule | Lipinski's rule of five | WDI like rule |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C1 | Qualified | Violated | Mid-structure | Suitable | In 90% cutoff |

| C2 | Qualified | Violated | Mid-structure | Suitable | In 90% cutoff |

| C3 | Qualified | Violated | Mid-structure | Suitable | In 90% cutoff |

| C4 | Qualified | Suitable1 | Mid-structure | Suitable | In 90% cutoff |

| C6 | Qualified | Violated | Mid-structure | Suitable | In 90% cutoff |

| C7 | Qualified | Violated | Mid-structure | Suitable | In 90% cutoff |

Table 4.

in silico ADME profiling of 6-hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1-on chalcone-like derivatives possessing tyrosinase inhibitory activity.

| Compounds | Absorption | Distribution | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| Human intestinal absorption (%) 0 - 20 (poor) 20 - 70 (moderate) 70 - 100 (good) | in vitro caco-2 cell permeability (nm/s) <4 (low) 4–70 (moderate) >70 (high) | in vitro MDCK cell permeability (nm/s) < 25 (low) 25–500 (moderate) >500 (high) | in vitro skin permeability (log Kp, cm/h-) | in vitro plasmaprotein binding (%) > 90 (strong) < 90 (weak) | in vivo blood-brain barrier penetration (C.brain/C.blood) < 0.1 (low) 0.1 - 2 (moderate) > 2 (high) | |

| C1 | 95.60 | 28.01 | 20.28 | -2.64 | 94.93 | 1.08 |

| C2 | 95.97 | 34.48 | 4.55 | -2.99 | 91.47 | 0.13 |

| C3 | 95.60 | 5.80 | 0.39 | -2.64 | 94.89 | 0.95 |

| C4 | 93.45 | 21.56 | 19.10 | -2.73 | 97.04 | 1.55 |

| C6 | 95.62 | 32.09 | 14.78 | -3.09 | 89.08 | 0.20 |

| C7 | 96.46 | 25.47 | 39.32 | -2.52 | 100.00 | 4.46 |

| Kojic acid | 79.39 | 3.79 | 9.77 | -4.78 | 20.53 | 0.26 |

The results showed that all the structures fulfilled Lipinski’s rule of five, CMC like rule, MDDR like rule, and WDI like rule (Table 3).

As presented in Table 4, all the compounds predicted to have human intestinal absorption values of more than 70%, indicative of being appropriate for oral administration. All the compounds exhibited less negative log Kp values than kojic acid did; therefore, the proposed tyrosinase inhibitors might have better skin permeability compared to kojic acid. This can be an advantage of C2 (the most potent derivative) over kojic acid since poor skin penetration has been reported as a restriction for kojic acid. In addition, it was predicted for all the derivatives to bind strongly to the plasma proteins (an exception is for C6), indicating reduced excretion and increased half-life. Compound C7 could not be suggested as a good candidate, since it possessed a plasma protein binding value of 100%. Low blood-brain barrier permeation was assessed for the C1, C2, C3, and C4 derivatives; hence, it can be hoped that they are less likely to induce neurotoxicity. However, compounds C6 and C7 are predicted to show moderate and high penetration to the central nervous system, respectively.

DISCUSSION

Benzylidene-6-hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalenone chalconoids (C1-C10) were synthesized by the aldol condensation reaction of 6-hydroxy tetralone and differently substituted benzaldehydes. The synthesized compounds were evaluated for their potential inhibitory effect on the diphenolase activity of mushroom tyrosinase by a spectrophotometric method. Surprisingly, most of the compounds exhibited good inhibition of tyrosinase (IC50 = 8.8 – 48.6 μM). Compound C2 bearing 3,4,5-trimethoxy substitution on benzylidene group was found to be the most potent tyrosinase inhibitor with an IC50 value of 8.8 μM, which was comparable to that of kojic acid. Moreover, the inhibition kinetic study showed that C2 was a competitive tyrosinase inhibitor. It is well-established that in chalcones, 2 and 4 hydroxyl group attached to the ring A is important for tyrosinase inhibition and 4-hydroxyl substituted derivatives were found to be the most active tyrosinase inhibitor showed strong chelation with binuclear copper-containing tyrosinase enzymes (4,24,36). Moreover, 4′ hydroxyl group is slightly more selective than 2′ hydroxyl (24). In our findings, the presence of hydroxyl (the present work) or methoxy (our previous work) (27) on the C6 position of tetralone ring (as C4 position in chalcones) has led to potent tyrosinase inhibitors. In the case of 6-hydroxy substituted benzylidene-tetralones, the presence of methoxy group on ring B and especially on 2′, 4′, and 5′ positions (benzylidene) resulted in more potent compounds. It seems that introducing hydroxyl on ring B would reduce the activity. However, in the case of 6-methoxy-benzylidene-tetralones presence of hydroxyl group on ring B-methoxy substituted derivatives improved the activity (27). The potential inhibitory effect of the dihydronaphthalenones derivatives was also examined in silico, via molecular docking analysis. The docking outcomes were in good agreement with the biological results and C2, having the most favored binding energy, was well accommodated in the active site of tyrosinase by establishing strong bonds with copper ions. The in silico drug-likeness and ADME prediction investigations further revealed that all the compounds, except C6 and C7 possessed acceptable drug-like and ADME properties; hence, it can be concluded that the lead tyrosinase inhibitor C2 might serve as a suitable drug-like candidate and can be suggested as a promising candidate for further drug development.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, a successful synthesis, biological evaluation, and analysis of possible molecular interactions of benzylidene-6-hydroxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalenones derivatives as tyrosinase inhibitors have been described. Taken together, the present study revealed that C2 (6-hydroxy-2-(3,4,5-trimethoxybenzylidene)-3,4-dihydronaphthalen-1(2H)-one) is a potent tyrosinase inhibitor and could be considered for further drug development.

Conflicts of interest statement

The authors declared no conflict of interest in this study.

Authors’ contribution

S. Ranjbar designed the experiment, analyzed the data, and co-wrote the paper. M. Mohammadabadi Kamarei performed the synthesis and biological tests. M. Khoshneviszadeh performed the biological tests and analyzed the data. H. Hosseinpoor and N. Edraki analyzed the data and co-wrote the paper. M. Khoshneviszadeh designed the experiment, analyzed the data, and co-wrote the paper.

Acknowledgments

This article was a part of the Pharm.D thesis of Mehraneh Mohammadabadi Kamarei which was financially supported by the Vice-Chancellor for Research, Shiraz University of Medical Sciences, Shiraz, I.R. Iran under Grant No. 94-01-12-10215. The authors wish to thank Mr. H. Argasi at the Research Consultation Center (RCC) of Shiraz University of Medical Sciences for his invaluable assistance in editing this manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Seo SY, Sharma VK, Sharma N. Mushroom tyrosinase: recent prospects. J Agric Food Chem. 2003;51(10):2837–2853. doi: 10.1021/jf020826f. DOI: 10.1021/jf020826f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lai X, Wichers HJ, Soler-Lopez M, Dijkstra BW. Structure and function of human tyrosinase and tyrosinase-related proteins. Chem Eur J. 2018;24(1):47–55. doi: 10.1002/chem.201704410. DOI: 10.1002/chem.201704410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korner A, Pawelek J. Mammalian tyrosinase catalyzes three reactions in the biosynthesis of melanin. Science. 1982;217(4565):1163–1165. doi: 10.1126/science.6810464. DOI: 10.1126/science.6810464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parvez S, Kang M, Chung HS, Bae H. Naturally occurring tyrosinase inhibitors: mechanism and applications in skin health, cosmetics and agriculture industries. Phytother Res. 2007;21(9):805–816. doi: 10.1002/ptr.2184. DOI: 10.1002/ptr.2184. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pillaiyar T, Manickam M, Namasivayam V. Skin whitening agents: medicinal chemistry perspective of tyrosinase inhibitors. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2017;32(1):403–425. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2016.1256882. DOI: 10.1080/14756366.2016.1256882. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pandya AG, Guevara IL. Disorders of hyperpigmentation. Dermatol Clin. 2000;18(1):91–98. doi: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70150-9. DOI: 10.1016/s0733-8635(05)70150-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.You A, Zhou J, Song S, Zhu G, Song H, Yi W. Structure-based modification of 3-/4-aminoacetophenones giving a profound change of activity on tyrosinase: from potent activators to highly efficient inhibitors. Eur J Med Chem. 2015;93:255–262. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.02.013. DOI: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2015.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tief K, Schmidt A, Beermann F. New evidence for presence of tyrosinase in substantia nigra, forebrain and midbrain. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1998;53(1-2):307–310. doi: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00301-x. DOI: 10.1016/s0169-328x(97)00301-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carballo-Carbajal I, Laguna A, Romero-Giménez J, Cuadros T, Bové J, Martinez-Vicente M, et al. Brain tyrosinase overexpression implicates age-dependent neuromelanin production in Parkinson’s disease pathogenesis. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):973–991. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-08858-y. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-019-08858-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hasegawa T. Tyrosinase-expressing neuronal cell line as in vitro model of Parkinson’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2010;11(3):1082–1089. doi: 10.3390/ijms11031082. DOI: 10.3390/ijms11031082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zolghadri S, Bahrami A, Hassan Khan MT, Munoz-Munoz J, Garcia-Molina F, Garcia-Canovas F, et al. A comprehensive review on tyrosinase inhibitors. J Enzyme Inhib Med Chem. 2019;34(1):279–309. doi: 10.1080/14756366.2018.1545767. DOI: 10.1080/14756366.2018.1545767. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Nerya O, Ben-Arie R, Luzzatto T, Musa R, Khativ S, Vaya J. Prevention of Agaricus bisporus postharvest browning with tyrosinase inhibitors. Postharvest Biol Technol. 2006;39(3):272–277. DOI: 10.1016/j.postharvbio.2005.11.001. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eghbali-Feriz S, Taleghani A, Al-Najjar H, Emami SA, Rahimi H, Asili J, et al. Anti-melanogenesis and anti-tyrosinase properties of Pistacia atlantica subsp. mutica extracts on B16F10 murine melanoma cells. Res Pharm Sci. 2018;13(6):533–545. doi: 10.4103/1735-5362.245965. DOI: 10.4103/1735-5362.245965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saghaie L, Pourfarzam M, Fassihi A, Sartippour B. Synthesis and tyrosinase inhibitory properties of some novel derivatives of kojic acid. Res Pharm Sci. 2013;8(4):233–242. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ranjbar S, Shahvaran PS, Edraki N, Khoshneviszadeh M, Darroudi M, Sarrafi Y, et al. 1,2,3-Triazole-linked 5-benzylidene (thio) barbiturates as novel tyrosinase inhibitors and free-radical scavengers. Arch Pharm. 2020;353(10):2000058. doi: 10.1002/ardp.202000058. DOI: 10.1002/ardp.202000058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Karimian S, Ranjbar S, Dadfar M, Khoshneviszadeh M, Gholampour M, Sakhteman A, et al. 4H-benzochromene derivatives as novel tyrosinase inhibitors and radical scavengers: synthesis, biological evaluation, and molecular docking analysis. Mol Divers. 2020:1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11030-020-10123-0. DOI: 10.1007/s11030-020-10123-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Darroudi M, Ranjbar S, Esfandiar M, Khoshneviszadeh M, Hamzehloueian M, Khoshneviszadeh M, et al. Synthesis of novel triazole incorporated thiazolone motifs having promising antityrosinase activity through green nanocatalyst CuI-Fe3O4@ SiO2 (TMS-EDTA) Appl Organomet Chem. 2020;34(12):e5962. DOI: 10.1002/aoc.5962. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang TS. An updated review of tyrosinase inhibitors. Int J Mol Sci. 2009;10(6):2440–2475. doi: 10.3390/ijms10062440. DOI: 10.3390/ijms10062440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ito N, Hirose M, Fukushima S, Tsuda H, Shirai T, Tatematsu M. Studies on antioxidants: their carcinogenic and modifying effects on chemical carcinogenesis. Food Chem Toxicol. 1986;24(10-11):1071–1082. doi: 10.1016/0278-6915(86)90291-7. DOI: 10.1016/0278-6915(86)90291-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rammohan A, Reddy JS, Sravya G, Rao CN, Zyryanov GV. Chalcone synthesis, properties and medicinal applications: a review. Environ Chem Lett. 2020;18:433–458. DOI: 10.1007/s10311-019-00959-w. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rocha S, Ribeiro D, Fernandes E, Freitas M. A systematic review on anti-diabetic properties of chalcones. Curr Med Chem. 2020;27(14):2257–2321. doi: 10.2174/0929867325666181001112226. DOI: 10.2174/0929867325666181001112226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kar Mahapatra D, Asati V, Bharti SK. An updated patent review of therapeutic applications of chalcone derivatives (2014-present) Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2019;29(5):385–406. doi: 10.1080/13543776.2019.1613374. DOI: 10.1080/13543776.2019.1613374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mousavi ZSZ, Zarghi A, Alipour E. The synthesis of chalcon derivatives containing epoxide SO2Me with potential anticancerous effects. Res Pharm Sci. 2012;7(5):S613. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Akhtar MN, Sakeh NM, Zareen S, Gul S, Lo KM, Ul-Haq Z, et al. Design and synthesis of chalcone derivatives as potent tyrosinase inhibitors and their structural activity relationship. J Mol Struct. 2015;1085:97–103. DOI: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2014.12.073. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kostopoulou I, Detsi A. Recent developments on tyrosinase inhibitors based on the chalcone and aurone scaffolds. Curr Enzym Inhib. 2018;14:3–17. DOI: 10.2174/1573408013666170208102614. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Khatib S, Nerya O, Musa R, Shmuel M, Tamir S, Vaya J. Chalcones as potent tyrosinase inhibitors: the importance of a 2,4-substituted resorcinol moiety. Bioorg Med Chem. 2005;13(2):433–441. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.10.010. DOI: 10.1016/j.bmc.2004.10.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ranjbar S, Akbari A, Edraki N, Khoshneviszadeh M, Hemmatian H, Firuzi O, et al. 6-Methoxy-3,4-dihydronaphthalenone chalcone-like derivatives as potent tyrosinase inhibitors and radical scavengers. Lett Drug Des Discov. 2018;15(11):1170–1179. DOI: 10.2174/1570180815666180219155027. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ghafari S, Ranjbar S, Larijani B, Amini M, Biglar M, Mahdavi M, et al. Novel morpholine containing cinnamoyl amides as potent tyrosinase inhibitors. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019;135:978–985. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.05.201. DOI: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.05.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dehghani Z, Khoshneviszadeh M, Khoshneviszadeh M, Ranjbar S. Veratric acid derivatives containing benzylidene-hydrazine moieties as promising tyrosinase inhibitors and free radical scavengers. Bioorg Med Chem. 2019;27(12):2644–2651. doi: 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.04.016. DOI: 10.1016/j.bmc.2019.04.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tehrani MB, Emani P, Rezaei Z, Khoshneviszadeh M, Ebrahimi M, Edraki N, et al. Phthalimide-1,2,3-triazole hybrid compounds as tyrosinase inhibitors; synthesis, biological evaluation and molecular docking analysis. J Mol Struct. 2019;1176:86–93. DOI: 10.1016/j.molstruc.2018.08.033. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yee SW, Jarno L, Gomaa MS, Elford C, Ooi LL, Coogan MP, et al. Novel tetralone-derived retinoic acid metabolism blocking agents: synthesis and in vitro evaluation with liver microsomal and MCF-7 CYP26A1 cell assays. J Med Chem. 2005;48(23):7123–7131. doi: 10.1021/jm0501681. DOI: 10.1021/jm0501681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahdavi M, Ashtari A, Khoshneviszadeh M, Ranjbar S, Dehghani A, Akbarzadeh T, et al. Synthesis of new benzimidazole-1,2,3-triazole hybrids as tyrosinase inhibitors. Chem Biodivers. 2018;15(7):e1800120. doi: 10.1002/cbdv.201800120. DOI: 10.1002/cbdv.201800120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yee SW, Simons C. Synthesis and CYP24 inhibitory activity of 2-substituted-3,4-dihydro-2H-naphthalen-1-one (tetralone) derivatives. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2004;14(22):5651–5654. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.08.040. DOI: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2004.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Asadi P, Khodarahmi G, Farrokhpour H, Hassanzadeh F, Saghaei L. Quantum mechanical/molecular mechanical and docking study of the novel analogues based on hybridization of common pharmacophores as potential anti-breast cancer agents. Res Pharm Sci. 2017;12(3):233–240. doi: 10.4103/1735-5362.207204. DOI: 10.4103/1735-5362.207204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Khodarahmi G, Asadi P, Farrokhpour H, Hassanzadeh F, Dinari M. Design of novel potential aromatase inhibitors via hybrid pharmacophore approach: docking improvement using the QM/MM method. RSC Adv. 2015;5:58055–58064. DOI: 10.1039/C5RA10097F. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang X, Hu X, Hou A, Wang H. Inhibitory effect of 2,4,2′4,′-tetrahydroxy-3-(3-methyl-2-butenyl)-chalcone on tyrosinase activity and melanin biosynthesis. Biol Pharm Bull. 2009;32(1):86–90. doi: 10.1248/bpb.32.86. DOI: 10.1248/bpb.32.86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]