Abstract

The field of medical ultrasound has undergone a significant evolution since the development of microbubbles as contrast agents. However, due to their size, microbubbles remain in the vasculature, and therefore have limited clinical applications. Building a better – and smaller – bubble can expand the applications of contrast-enhanced ultrasound by allowing bubbles to extravasate from blood vessels – creating new opportunities. In this review, we summarize recent research on the formulation and use of NBs as imaging agents and as therapeutic vehicles. We discuss the ongoing debates in the field and reluctance to accepting NBs as an acoustically active construct and a potentially impactful clinical tool that can help shape the future of medical ultrasound. We hope that the overview of key experimental and theoretical findings in the NB field presented in this paper provides a fundamental framework that will help clarify NB-ultrasound interactions and inspire engagement in the field.

Keywords: nanobubbles, microbubbles, contrast enhanced ultrasound, molecular imaging, drug delivery

Introduction

Biomedical ultrasound (US) imaging is a well-established clinical tool used for the diagnosis and management of a broad range of diseases. With applications ranging from fetal imaging to echocardiography, its diagnostic use is exceeded only by 2D X-ray imaging [1]. US imaging uses sound waves above 20 kHz to construct images based on the interaction of the sound waves with the surrounding environment. The US waves, generated by a transducer (for imaging typically in the 1-20 MHz range), will be either reflected, scattered or absorbed by tissue and boundaries between tissues, such as skin and bone. The timing and strength of the returned echoes can then be used to determine the tissue location (assuming the speed of sound is known) and scattering characteristics with high spatial and temporal resolution. US images can be collected at over 20 frames per second, with a spatial resolution approaching 200 microns for higher frequency transducers. For a detailed overview of the physics behind ultrasound, please refer to the book by Richard Cobbold (Fundamentals of Biomedical Ultrasound) [2].

In addition to high temporal and spatial resolution of image acquisition, the popularity of US has been driven by notable advantages over X-ray computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), such as its well-established safety profile, low cost, portability and broad accessibility. These benefits tend to outweigh some of the biggest challenges with ultrasound such as operator dependence and poor soft tissue contrast. The contrast and anatomical detail in ultrasound images has not been considered favorable compared to other modalities (e.g. MRI). One technology that has significantly improved US image quality and expanded US applications worldwide is the development of bubble-based contrast agents.

The advent of microbubble (MB) contrast agents has stimulated innovative strategies for cancer detection, therapy and post-therapy monitoring, especially in the past two decades [3–5]. The use of gas as a contrast agent for ultrasound was first noted over 50 years ago [6]. Since then, several generations of this concept evolved from using unstabilized carbon dioxide (which was rapidly dissipated in the blood) to shell stabilized constructs of more hydrophobic gasses. Current clinical MB formulations are comprised of a hydrophobic gas core (such as perfluoropropane – C3F8 or sulfur hexafluoride -- SF6) stabilized by a lipid, polymer, or protein shell. Bubbles generate contrast due to their interactions with the ultrasound waves. When placed in an acoustic field, bubbles oscillate in response to positive and negative pressure changes; these oscillations are distinct from the surrounding medium due to differences in the compressibility and density between the gas and blood and the viscoelastic properties of the shell, as described below.[7, 8] MBs have US FDA (United States Food and Drug Administration) approval for enhancement of echocardiographs and detection of liver lesions [4] in adult and pediatric [9] populations, and have been investigated widely in numerous other clinical diagnostic applications. An excellent review of clinical diagnostic use of MBs and their safety profile compared to other contrast media was recently published by Erlichman et al. [5]. MBs have also been examined in numerous therapeutic applications ranging from neuromodulation to sensitization of tumors to radiation therapy, and several approaches are currently in clinical trials [7, 10–12]. While a detailed summary of the current state of the art with MBs is beyond the scope of this review, we offer some additional thoughts about this field in the second part of this review.

MBs have had a significant impact in the field; however, MBs have some inherent challenges which may limit their utility in applications such as molecular imaging and image-guided therapy. The development of MB applications has been constrained by a relatively large particle diameter (~1-8 μm), which confines the MB to the vasculature limiting their targets to upregulated biomarkers only within the intravascular space [13–16]. This reduces the potential for MBs to target biomarkers outside of the endothelium. MBs are typically produced at lower concentrations (~106 to 108 bubbles/ml), which reduces their longevity both in ambient conditions and in vivo. Increasing the concentration is feasible, but leads to significant attenuation and shadowing, thus may not be practical to implement [17]. For clinical use, MBs are produced via on-site ‘activation’, which ranges from the hydration of a freeze-dried powder (Lumason®), to mechanical agitation of sealed vials containing lipid solutions and gas (Definity ®). This process yields highly heterogeneous bubble populations, which range from submicron to ~2 to 10-micron bubble diameters. It is worth noting that, in some cases, the polydispersity of MBs could be an advantage since it allows the use of many different frequency transducers and enables imaging of many anatomical targets. However, the general recent community consensus is that monodisperse bubbles could provide increased sensitivity and specificity to detect lower MB concentrations, critical for molecular imaging applications. Likewise, a reduction in bubble diameter to the nanoscale can complement MB capabilities and provide a robust platform for expanding the biomedical applications of ultrasound. Thus, in this review, we will focus on work associated with stable, echogenic, uniform NBs.

Nanobubbles (also frequently referred to as sub-micron or nanoscale bubbles, abbreviated here as NBs) have been known to exist in commercially available microbubble formulations such as Definity® for nearly 20 years [18] [19]. As mentioned above, the microbubble formation, or “activation”, occurs via self-assembly of solubilized amphiphiles around a hydrophobic gas core. This relatively uncontrolled process, results in a highly heterogeneous bubble population with a significant sub-micron component. However, as explained in detail below, the conventional theory would dictate that with decreasing bubble radius the backscatter from coated bubbles decreases significantly, and the resonant frequency increases rapidly. Thus, the sub-micron component of the acoustic activity was thought to be insignificant compared to that of the larger microbubbles (~ 1-5 microns in diameter, which by coincidence, have a resonant frequency close to the operating range of many commercial ultrasound imaging devices, about 3-5 MHz) and was largely dismissed. It was not until the intentional formulation of echogenic NBs by Wheatly et al in 2004[20] and the first demonstration of their activity in vivo in 2006 by the same group [21], that the idea of NBs and their application as contrast agents in biomedical ultrasound became recognized. Concurrently, reports of circulating NBs coalescing in extravascular space into imageable microbubbles were published by Rapoport et al [22]. However, as a field, echogenic NBs did not see rapid adoption until approximately 2010, when a burst of publications reported on their use in cancer imaging [23–31]. In the last decade, research into the application of NBs in diagnostic ultrasound and ultrasound-mediated drug delivery has seen rapid growth as shown in Figure 1A. The growth can also be correlated with the more widespread adoption of bulk NBs by the physics and colloid communities [32].

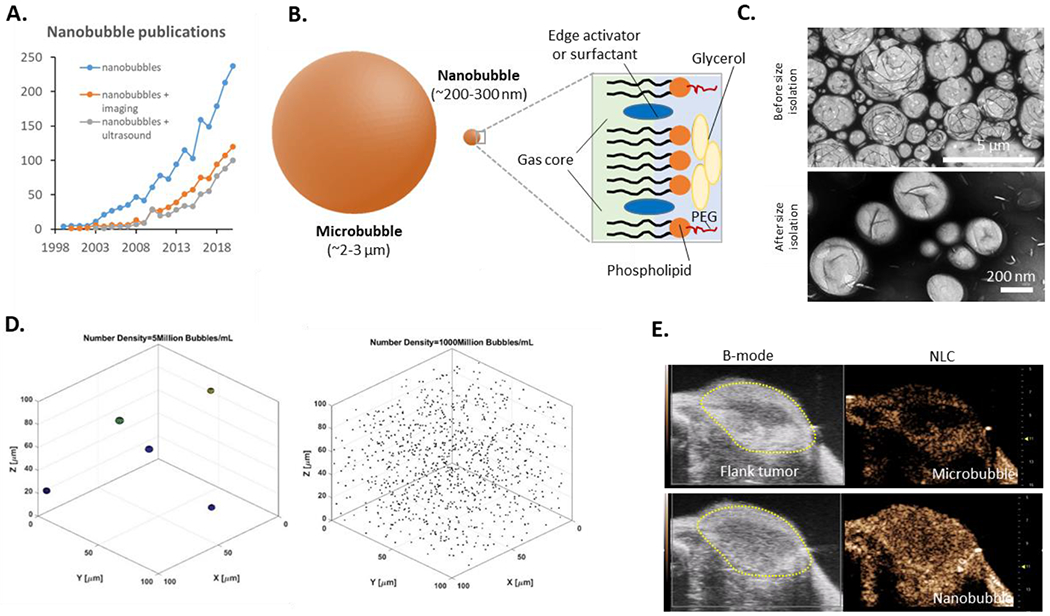

Figure 1.

Overview showing (a) the rapid growth in publications from 1999-2020 focused in general on NBs (blue line), NBs in ultrasound-oriented applications (gray line) with first publication in 2003, and more general imaging applications (orange line) with first publication in the year 2000. (b) To scale representation of a microbubble and NB and the typical composition of a bubble used in ultrasound imaging. (c) Transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images showing structure of bubbles immediately following self-assembly and following size isolation via differential centrifugation. The apparent heterogeneous mixture of bubbles prior is reduced to a fairly uniform NB fraction following the centrifugation process. (d) Simulation illustrating the striking difference in particle density per voxel of microbbubles compared to NBs for typical concentrations. It is likely that the high concentration strongly contributes to the observed NB acoustic activity. (e) Representative images of the same murine flank tumor showing microbubble (MicroMarker®) and NB enhancement in B-mode and nonlinear contrast mode. Images were acquired with the Visualsonics Vevo 3100 scanner at 18 MHz and 4% power. We thank Dr. Al De Leon, Dr. Eric Abenojar, and Mr. Hossein Haghi for contributions to this figure.

Early experimental reports of echogenic NBs garnered little attention from the contrast-enhanced ultrasound and / or microbubble and biophysics communities, due to a lack of concrete, overwhelming evidence demonstrating that the measured or visualized acoustic activity was indeed stemming from the sub-micron bubbles and not from larger (near 1 micron or above) bubbles which may have been contaminating the total bubble population. Theoretically, the backscatter generated from the interaction of ultrasound with a particle is highly dependent on radius, with a 1 μm particle scattering 106 times more than a 0.1 μm particle at the clinical frequency range (3-15 MHz, ignoring potential resonance). However, this assumes Rayleigh scattering independent of the effect of shell composition of the bubble oscillator such as shell viscosity, shell elasticity and surface tension, as well as the acoustic pressure. At higher pressures and/or reduced surface tension of the bubble shell, the nonlinear activity of coated bubbles significantly contributes to its scattering strength. As described in detail later in this review, the current hypothesis is that the nonlinear activity due to lipid shell coupled with the high particle concentration per imaging voxel, are thought to be the major driving force behind the acoustic activity of NBs.

Recent progress in research using NBs for medical ultrasound imaging and drug delivery applications has been aided by the rapid developments in theoretical physics and experimental biophysics which provided strong evidence for the existence of bulk NBs as a viable, long-lasting construct[32]. Concurrently several key experimental developments in imaging applications provided evidence that acoustically active NBs may be a viable contrast agent for ultrasound imaging. These were: 1) the development of NB formulation methodologies with rigorous size control to reduce the size of the NBs to 200-400 nm and to remove all bubbles larger than 1 micron, which could be contaminating the solution and reducing control of acoustic response [28, 30, 33]; 2) availability of instrumentation for quantitative, precise measurement of particle diameter, concentration and, most importantly, buoyancy and total gas volume [34] [35, 36]; 3) manipulation of NB shell to reduce interfacial tension, and increase deformability using surfactants such as Tween 80 and Pluronic and edge activators such as propylene glycol, 4) the theoretical modeling of bubble acoustic response at lower surface tension and higher acoustic pressures [37] [38]; and 5) rigorously controlled in vitro and in vivo demonstrations of NB acoustic activity, extravasation and imaging characteristics compared to microbubbles [39] [29, 40, 41]. In the following sections, we detail these developments in the NB formulation and characterization. We then briefly discuss a theoretical framework for understanding the acoustic activity of NBs, provide an overview of the in vivo imaging and therapeutic applications and finally discuss emerging future directions in this exciting, still-developing field.

NB formulation and characterization:

NB formulation:

A range of formulation strategies for gas-core nanoparticles has been explored. Many of the concepts rely heavily on established processes from the fields of interfacial and colloid science and nanomedicine, where formulation of sub-micron particles, especially via self-assembly, has been thoroughly developed and vetted [42, 43]. It is important to note that many different echogenic nanoparticles have been previously formulated, including echogenic liposomes [44, 45], and nanodroplets [46]. However, this review will focus only on self-assembled gas-core, lipid, and surfactant stabilized NBs.

Production methods of echogenic nanoscale gas bubbles use surfactants and additives to modulate the phospholipid membrane’s viscoelastic properties and reduce the bubble’s size to as low as 120 nm in both ambient and physiological conditions[23, 47–52]. Most of the NB formulation methods evolved from microbubble preparation techniques. The primary mode of formulation is via simple self-assembly of various phospholipids (either a cocktail or a single lipid) or proteins and surfactants at the interface of an aqueous dissolution medium (such as phosphate-buffered saline, PBS, normal saline or water). Lipids commonly utilized include 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DPPC), 1,2-dibehenoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (DBPC), 1,2 Dipalmitoyl-sn-Glycero-3-Phosphate (DPPA), 1,2-dipalmitoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine (DPPE), and 1,2-distearoyl-snglycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-[methoxy(polyethylene glycol)-2000] (ammonium salt) (DSPE-mPEG 2000). High lipid concentrations on the order of 10 mg/mL have been used to form the most effective, stable NB populations. This higher starting lipid content (which is ~10× higher than that for clinical microbubbles) is likely to contribute to high NB yield and a reduction in bubble coalescence [53]. Within this method are three distinct lipid dissolution processes – (a) shell materials dissolved in chloroform or another organic solvent prior to hydration of the lipid cake, (b) direct dissolution of all shell components in the aqueous medium, and (c) direct dissolution of shell components in propylene glycol prior to suspension in aqueous medium [33]. Sonication and/or elevated temperatures can be used in each case to improve lipid dissolution. These processes can be performed with high volumes, increasing the formulation efficiency. The desired hydrophobic gas is forced into solution by mechanical agitation either using a modified dental amalgamator or a probe sonicator. This can be done in the bulk solutions or in individual sealed vials. Following activation, the bubble solution is heterogeneous, and an additional step must be performed to isolate the NBs from this solution. More on this below.

Some notable exceptions to lipid NBs have been reported. Among these are: 1) echogenic gas vesicles developed by Shapiro et al [54, 55], 2) PLGA-shelled NBs [25, 31] 3) nested NBs developed recently [56], and 4) nanocups developed by Kwan et al [57]. Each of these constructs offers unique advantages and possess distinct mechanisms of signal generation in an acoustic field. Gas vesicles are naturally occurring and can be genetically modified and remain stable for an extended period. The unique biologic origin enables extensive and predictable manipulation of these agents. PLGA-shelled NBs also offer greater stability compared to lipid-shelled bubbles. They are also easier to manipulate post-formulation and have a significantly increased cargo capacity for drug delivery. However, both the gas vesicles and the PLGA-based NBs currently require high acoustic pressures for generation of detectable backscatter at clinically relevant frequencies. This also makes their echogenicity short lived. Additional development is needed to address these challenges. While they are not fully coated gas bubbles, nanocups offer an interesting alternative formulation. These constructs are formulated by seeded polymerization of polystyrene coated with cross-linked polymethyl methacrylate. Upon dehydration and re-hydration, the nanocups deform and create a cavity which entraps gas. This gas NBs, in turn, serve as cavitation nuclei upon exposure to ultrasound pressures above 500 kPA, and have been used in drug delivery applications. Nested NBs developed recently, are lipid shell stabilized gas bubbles of C4F10 which are nested inside of liposomes. This formulation may stabilize the gas for an extended period, and is also a promising theranostic agent, due to the increased cargo capacity of the liposome.

On the importance of NB size isolation:

Effective size isolation of NBs is essential for producing reliable and repeatable bubble formulations with well-defined diameters and for carrying out reproducible experiments, the results of which can be used to support the notion that the observed activity is derived from NBs, not a small population of microbubbles. Small numbers of microbubbles can significantly contribute to the overall ultrasound signal from a mixed NB solution. Hypothetically, for a NB concentration of 1×1011 bubbles/ml, even if 99.9% of the particles were in the sub-micron range, this would leave 0.1% (or 10 million) bubbles which were larger than 1 micron and could significantly contribute to the ultrasound backscatter. In some of the first published reports on applications of NBs in imaging, where the reported NB diameter was ~400-600 nm, it is possible that a significant portion of the signal visualized in in vitro and in vivo imaging applications was from microbubbles.

Techniques for improved isolation of NBs from the heterogeneous initial suspension include: isolation by differential centrifugation [35, 58] coupled with filtration by rigorously characterized syringe filters [59]. Both techniques, if implemented rigorously, significantly reduce microbubble contamination in the final suspensions. Due to the greater buoyancy of microbubbles, if left undisturbed, the solutions will separate into two fractions, with the less or neutrally buoyant NBs remaining at the bottom portion within 1-2 hours. However, to expedite the separation, differential centrifugation is typically utilized to effectively isolate NBs and remove most, if not all, microbubbles from the solutions. When centrifuged at 50·g for 5 min, all bubbles larger than 0.7 μm should rise 0.5 cm or more. As an additional or as a standalone step, filtration also can be utilized. Here, either a sequential or single filtration process with well-characterized syringe filters can reduce the NB diameter and further reduce the dispersity of the population [59]. Overall, NBs formulated using this process can be made at a high concentration (1011/ml) with diameters ranging between 100-600 nm, are highly reproducible, scalable, and tend to be significantly more stable in vivo than clinical MB agents. [35, 60, 61] However, characterization of NBs remains a challenge despite many promising technologies.

NB characterization:

Several standard techniques are used to quantify nanoparticle size distribution and concentration. These include dynamic light scattering (DLS), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), cryo-electron microscopy [36], Nanoparticle Tracking Analysis (NTA) [62] and the Coulter Counter [63]. Each of these techniques comes with caveats, and when used alone, none provide an accurate representation of the nanoparticle size distribution and concentration. Thus multiple methods should be used to validate any NB formulation. For diameter measurement, DLS is high throughput and is considered the industry standard for measuring the nanoparticle population’s size distribution. The technique is highly sensitive and can measure a broad size range from several nanometers to >10 microns, and is independent of particle density. Zeta potential measurements are also conducted using the DLS equipment. However, DLS does not measure particle concentration. To measure nanoparticle concentration in addition to size, instruments such as the Coulter Counter, NTS and Resonant Mass Measurement (RMM) are available. Because formulation via self-assembly is not well controlled, the resulting particles are highly heterogeneous, spanning <10 nm to > 5 microns. In unprocessed solutions, the mean diameter is roughly 1-3 microns. These bubbles are typically characterized via the Coulter counter since this technique provides information about the particle size and concentration. However, as reported previously, the Coulter technique has some challenges with detection limits depending on the aperture used, as well as with coincidence artifacts (where several particles are counted as a single one) [64]. The Coulter counter also cannot determine whether a particle is filled with gas or a solid undissolved lipid out of solution or a micelle or a giant unilamellar vesicle or dust. The detection limit for larger apertures tends to hover around 1 micron to 500 nm, and at the smallest aperture as small as 200 nm.

RMM is the only method capable of distinguishing particle buoyancy. The technique has been validated and well established as a useful tool for NB characterization [34, 35]. Experiments have shown that even with well-developed formulation protocols, significant non-buoyant populations of nanoparticles are present in solutions. While these non-buoyant populations of nanoparticles do not have significant acoustic activity, the particles will be counted in techniques such as the Coulter Counter or NTA, which can potentially overestimate the actual gas-core bubble concentration in a formulation. However, RMM is not without caveats. First, it relies on a microfluidic sensor, limiting the size of the nanoparticles passing through it. The nanosensor enables measurement of up to 2 microns. To measure larger particles, the micro-sensor must be utilized. However, this sensor cannot detect smaller particles. As such, both sensors should be used for each heterogeneous solution, making the technique somewhat cumbersome. For buoyant particles, the limit of detection tends to be near 100 nm. Thus many smaller micelles in the solution will not be counted. Finally, the particle diameter calculation relies on input parameters such as the particle density, which the user provides and can be difficult to establish for new formulations.

Ultimately, at least two techniques should be used to characterize a NB formulation. These should be capable of measuring diameter with a broad limit of detection (DLS) and accurately determining the particle concentration (Coulter or RMM). Proper technique development and validation are essential yet quite difficult. A rigorous, quantitative measurement of the gas contained within a bubble can be used to validate any of the above-mentioned measurement methods. Headspace gas chromatography / mass spectrometry (GC/MS) is a well-established, highly quantitative technique that can be used to validate measurements based on Coulter, RMM, NTS and to some degree DLS.

Manipulation of surface tension and shell viscoelastic properties:

A reduction in the interfacial tension of the stabilizing shell reduces the Laplace pressure of a gas bubble. Several surfactants have been explored for this application in the NB community. The most prevalent of these is the non-ionic surfactant Pluronic (also known as poloxamer). Various Pluronics have been explored as NB additives, with the most frequently utilized being Pluronic L10, F68, and L61. The effect of varying the Pluronic composition has been extensively investigated. Furthermore, shell deformability and buckling have also been shown to contribute significantly to the acoustic bubble response and bubble stability both within the acoustic field and under ambient conditions. Here edge activators, such as propylene glycol, which have been used commonly to increase liposomes’ deformability and increase penetration through layers of the skin and liposome literature, have been investigated [65]. Propylene glycol also acts as a solvent for lipids and can be used to eliminate chloroform in NB formulation [33].

To summarize, the formulation of NBs yields particles of <100 to 600 nm in diameter and a high particle concentration (on the order of 1011 bubbles/mL). The resulting NB features were similar to conventional nanoparticles, such as micelles. At the same time, several characteristics distinguish NBs from other nanoparticles. Foremost is the lower particle density due to a gas core. Lower density particles have been shown to marginate more effectively in flow, increasing the probability of extravasation in hyperpermeable vasculature.[66] Another feature is a highly deformable shell combined with a compressible gas core that enables better penetration and extravasation.[67] Nanoparticle density, deformability and concentration [68] have all been shown to improve tumor accumulation. Consistent with these findings, intact, acoustically active NBs have been shown to readily extravasate and accumulate in tumors [39] [69, 70] These features make NBs useful in various applications described below.

Theoretical considerations and simulations

What can explain the contrast seen in the published work? It is not expected that NBs would significantly contribute to ultrasound backscatter at conventional clinical imaging frequencies. The wavelength of ultrasound at clinically relevant frequencies (1-20 MHz) is approximately 1500 – 75 mm, which is orders of magnitude greater than the sub-micron NB size (~ 0.2 μm). Moreover, the resonant frequency of an uncoated bubble can be calculated from [71].

where R0 is the radius of the bubble, P0 is the ambient pressure, γ is the polytropic coefficient, p is the density of the medium (water) and σ is the surface tension of the medium. For a 0.2 μm (200 nm) air bubble, the resonant frequency is ~115 MHz (the addition of a bubble shell increases the resonant frequency). Therefore, NBs are far from their resonant frequency when exposed to 1-20 MHz ultrasound waves.

More generally, it is not expected that NBs have a large scattering cross section, even if the compressibility and density contrast is large (gas/fluid). Solutions to the Anderson model of a fluid sphere (a gas can be considered a liquid), reduce to that of a Rayleigh scatterer when the wavelength of the ultrasound is much greater than the size (a) of the bubble:

Since the scattering cross-section is proportional to a6, it is expected that scattering from a a = 1 μm microbubble is 106 greater than a 0.1 μm (200 nm diameter) bubble (ignoring that the microbubble may be close to resonance depending on the excitation frequency). However, the volume differential of a microbubble compared to a NB is proportional to r3. For a microbubble that is 10 times greater than the NB radius, the gas volume is 103 greater. Therefore, it would be difficult to simply increase the concentration of NBs to compensate for their significantly reduced scattering compared to microbubbles. If NBs can achieve similar echogenicity to microbubbles for clinically relevant ultrasound frequencies, there must be other factors that contribute to their enhanced echogenicity.

A critical insight was provided in our first experiments comparing MB and NB contrast in living mice. The experimental data presented in Figure 2 (unpublished data), which compares the injection of commercial microbubbles (Vevo MicroMarker, FUJIFILM VisualSonics, average size 1.8 μm)[72] with custom made NBs (average size 263 nm)[33]. The injection volumes (5 ml PBS + 50 ml bubble solution) were comparable for both agents. The concentration of the NBs was 1×1010 NB/ml and for the microbubbles 2×108 MB/ml. Contrast-enhanced US (CEUS) images were acquired with a Vevo 2100 (Fujifilm VisualSonics) at 1 fps at 18 MHz. Simultaneous B-mode and nonlinear contrast-enhanced images were acquired. This allows a direct comparison of a) changes in ultrasound backscatter and b) changes in the nonlinear scattering before and after the injection of the NBs. The video (Fig. 2, S1) shows that the NBs have comparable contrast to the MBs, but there are apparent differences in the time-intensity curves (TICs) and the spatial dependence of the kidney TICs. The CEUS images are based on an amplitude modulation method[73]. Consecutive ultrasound pulses of identical shape but with different amplitudes (e.g. a factor of 2) results in similar reflections from the linear scatterers but with an amplitude difference (×2). When scattered by the nonlinear NBs, the same two pulses would differ in both the amplitude and shape due to the bubble nonlinear response. For in-vivo imaging, this would suppress a significant portion of tissue scattering which is linear, and amplify bubble scattering, which is nonlinear. This is seen in Figure 2.

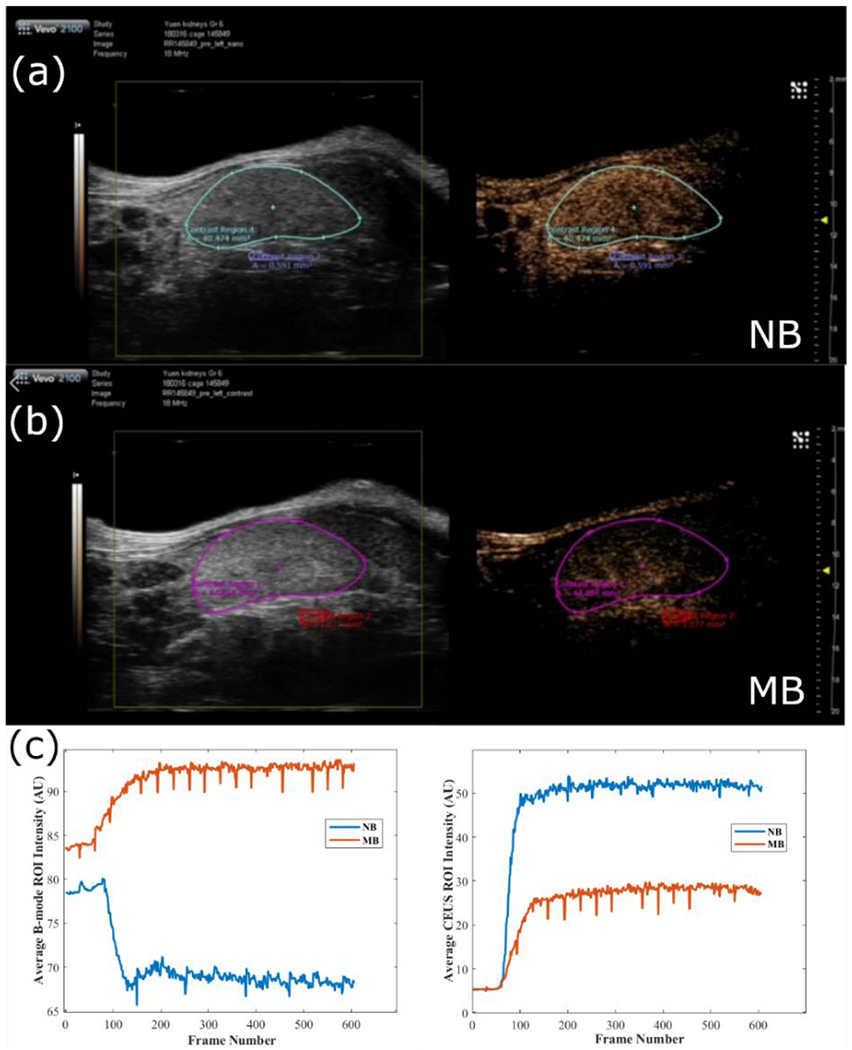

Figure 2.

Comparison of MB and NB contrast kinetics. Ultrasound B-mode images (left) and CEUS ultrasound imaging (right) of the mouse kidney in the last frame collected (data collected at 1fps) for (a) NB injection and (b) microbubble injection. In (c), the time kinetic curves for the mean intensity in the selected ROIs for B-mode (left) and CEUS (right) for the NB injection (blue curve) and MB injection (red curve). Video(s) of the above injections can be found in the Appendix.

The B-mode and CEUS images using MBs are presented in the bottom row. The same experiment was conducted with NBs approximately 25 minutes later, in the same mouse. The data are shown in the top row. For the NB data (top row), it can be observed that for this concentration, there is a significant enhancement in CEUS images. While there is a significant increase in the nonlinear CEUS signal, there is a slight decrease in ultrasound backscatter with the introduction of the NBs (as assessed by the average intensity in the ROI of the B-mode images). If the introduction of the NBs were to increase the ultrasound scattering overall, this would have been detected as an increased intensity in the B-mode image. Some of the differences between the MB and NB formulations can be attributed to the increased attenuation of the NB formulation (due to the higher concentration, evident from tissues under the kidney) and/or acquiring the images in different kidney imaging planes (even though an effort was made to image the same plane). Nevertheless, the difference in the ROI data in Figure 2 supports the hypothesis that key to the CEUS signal of the NBs is not their intrinsic echogenicity, but their nonlinear response to ultrasound.

When using a bolus injection of MBs in the same kidney, there is also a significant change in the CEUS images. However, in this case, the kidney filling dynamics are different: contrast enhancement is first apparent in the renal and interlobular arteries of the kidney, followed by cortical enhancement. Contrast enhancement is predominantly localized to the kidney with a minimal signal in the surrounding tissues. Moreover, there is an increase in the intensity in the B-mode images, indicating that contrast is enhanced without the addition of specialized CEUS sequences. An increase in the B-mode image intensity is not observed during the NB injection.

We have hypothesized that the key to the lipid shell NB effectiveness as a contrast agent are the nonlinear shell properties. It is important to distinguish two types of nonlinear bubble oscillations: a) inherent nonlinear oscillations of the bubble oscillator (in which shell properties are linear) and b) the enhanced nonlinearity of a lipid-coated bubble (in which the shell properties are nonlinear). This enhanced nonlinearity produces rich harmonics, even at very low pressures (as low as a few kPa), making NBs very effective in CEUS modes.

The nonlinear shell properties can contribute to the enhanced echogenicity in two ways: a) decreasing the effective resonance frequency of the NB and b) providing significant contrast due to nonlinear oscillations and a sharp pressure-dependent bubble response. It has been shown that increasing the ultrasound pressure incident on a microbubble decreases their resonant frequency, a phenomenon known as pressure-dependent resonance [74]. The pressure-dependent resonance is more significant for lipid shelled bubbles, with a strong dependence on the initial surface tension on the NB5 (and the shape of the curve that describes the surface tension curve as a function of the bubble radius). For example, in coated bubbles with an initial surface tension σo = 0.01 or 0.062 N/m, the pressure-dependent resonance frequency can occur at frequencies as low as half the linear resonant frequency. Therefore, we expect that the nonlinear shell properties significantly contribute to enhanced echogenicity at lower frequencies. However, this effect would not explain the lack of increased NB echogenicity in the B-mode imaging in Figure 2, while observing at the same time high CTR in the CEUS images. In these images, the strong contrast is likely due to the use of the amplitude modulation CEUS techniques. This is likely because rich harmonics are predicted from the NB oscillations[74–76], providing strong contrast compared to tissue. Moreover, the properties of the lipid shell enhance threshold dependent nonlinear oscillatory behavior. Saddle node (SN) bifurcations in the analysis of bifurcation diagrams, as shown by Sojahrood et. al.[75, 77], result in the abrupt enhancement of the scattered ultrasound above a specific pressure threshold, substantially increasing contrast in amplitude modulated CEUS schemes. As the CEUS scheme implemented on the commercial instrument is based on an amplitude modulation technique, a significant contributor to the enhanced echogenicity is likely the pressure-dependent threshold for the sudden increase in NB echogenicity. Therefore, it is postulated that key to understanding the unexpected echogenicity of lipid-coated NBs is the highly nonlinear response of the bubble oscillator.

Importance of informed optimized imaging hardware and software:

There is some evidence that CEUS contrast using NB contrast agents can be achieved at conventional ultrasound frequencies of using standard onboard nonlinear imaging pulse sequences (using transmit frequencies ranging from 3-9 MHz) [48, 70]. Moreover, the highly nonlinear NB response to ultrasound can be achieved at low pressures. Therefore, in principle, the only specialized ultrasound hardware required to achieve robust contrast is the existence of imaging modes that rely on the efficient detection of nonlinear signals (harmonics, subharmonics, super-harmonics) and especially modes that rely on processing subtraction algorithms (such as pulse inversion / amplitude modulation schemes) that can suppress background tissue echoes. Subtraction algorithms have significant advantages at higher frequencies. The energy of nonlinear tissue signal at the higher harmonics (e.g. 2nd) is more dominant at high frequencies than at low frequencies, reducing the CTR for harmonic CEUS imaging. Moreover, since ultrasound attenuation increases with frequency in soft tissues, the higher harmonic components at high frequencies will undergo higher attenuation than at lower frequencies. Therefore, optimized ultrasound parameters for CEUS imaging will be highly dependent on the application[72]. Finally, the time-intensity curves for NBs have different kinetics than MBs since NBs. Due to the NB size, the NBs potentially extravasate into tissues. Therefore, the contrast kinetic distribution (which depends on factors such as the blood flow and volume, vessel density, and vessel permeability) will be different[78, 79]. This may necessitate different approaches for the interpretation of semiquantitative parameters in the TIC (e.g. area under the curve (AUC), time to peak (TTP), wash-in time (WIT), wash-in rate (WIR), wash-out time (WOT), wash-out rate (WIR)) including more sophisticated compartmental modeling to describe the NB transport in tissues[78].

Monodisperse NBs:

Other investigators have shown that monodisperse MBs have a more uniform acoustic response and increased imaging sensitivity than polydisperse MBs [80, 81]. Consequently, this may also apply to monodisperse NBs when compared to polydisperse NBs. Using microfluidics techniques we have previously reported on[82, 83], we have developed a new approach to make monodisperse NB. The method uses a two-component gas mixture of water-soluble gas (nitrogen) and water-insoluble gas (octafluoropropane) to first generate monodisperse microbubbles (MBs) with a microfluidic flow-focusing junction. The MBs shrink due to the dissolution of the water-soluble components in the gas mixture. The degree of bubble shrinkage may be precisely controlled by tuning the ratio of water-soluble to water-insoluble gas components. This technique maintains the monodispersity of the NBs and in recent experiments has shown similar advantages to those of monodisperse MBs[84].

Imaging applications of NBs

Long-circulating contrast agents that can cross leaky tumor vasculature and penetrate into tissue provide a clear opportunity to augment the applications of contrast-enhanced ultrasound. Many diseases, including type 1 diabetes and cancer, have hyperpermeable vasculature [85]. The field of nanomedicine has taken advantage of, and in some cases hotly debated, the role of vascular permeability in the delivery of therapeutics, especially in cancer. Overall, however, it is generally accepted that vascular permeability does increase tumor accumulation of nanoparticles[86]. Building upon this concept, NBs have also been able to exploit enhanced vascular permeability to image tumors. Extravasation of the NBs to target biomarkers expressed in the tumor microenvironment and on cancer cells make the detection and delineation of tumors more effective and efficient. The small size, highly deformable shell and low density facilitate rapid NB margination and extravasation through leaky vasculature. Furthermore, NBs can be made at a high concentration (1011/ml). This increases scatterer number density, improving the sensitivity of detection and likelihood of extravasation into tumors, as demonstrated recently[68]. Evidence supporting the extravasation of NBs into tumors and the diabetic pancreas in mice is shown in Figure 3.

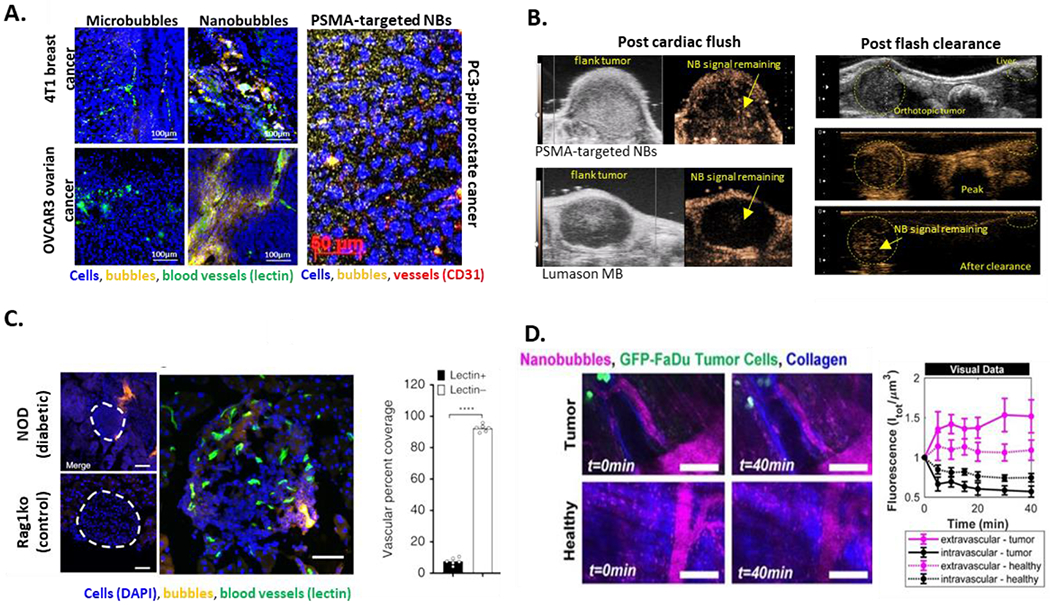

Figure 3.

NB extravasation quantified in a variety of models. (a) immunohistochemical analysis of fluorescent NB distribution in 4T1 breast, and OVCAR 3 ovarian tumors after bubble injection IV via the tail vein. (b) extravasation of acoustically active NBs assessed via ultrasound in animals after cardiac flush and in living mice; in the latter case, circulating bubbles were destroyed peripherally via repeated high-intensity flashes using a clinical transducer. (c) representative confocal images of an islet within a pancreas section of 10-week female non-obese diabetic (NOD) and 10-week-old Rag1ko control mouse following rhodamine-labeled NB infusion (orange). Right image shows maximum-projection confocal image of an islet of NOD mouse and the corresponding mean NB coverage in non-vascular areas (lectin negative) and vascular areas (lectin positive). (d) intravital microscopy in conjunction with simultaneous acoustic emission measurement in a window chamber model. In all cases, extravascular echogenic NB presence is clearly visible, providing strong evidence that NBs indeed can extravasate and accumulate in the extravascular tissue. Data also supports that the extravasated NBs are able to retain, at least in part, their acoustic activity. (a) Adapted with permission from: Wu et al Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology, 45(9), 2019 Fig 7and Perera et al, Nanomedicine NBM, Volume 20, 2020, Fig 5; (b) Unpublished data; (c) Adapted with permission from: Ramirez et al in Nat Commun 11, 2238 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15957-8, Fig 2; (d) Adapted with permission from: Theranostics 2020; 10(25):11690-11706. doi:10.7150/thno.51316, Fig 6.

Consideration of imaging parameters:

As mentioned above, bubbles scatter a large component of the incident pulse energy nonlinearly compared to tissue. Nonetheless, to achieve high sensitivity to bubble echoes in vivo, tissue backscatter must be removed while amplifying signals from the contrast agent. To accomplish this, most clinical scanners use a combination of pulse inversion (PI) and amplitude modulation (AM) to maximize the contrast to tissue ratio (CTR) [87]. PI uses two US pulses sent consecutively into the tissue, with the second pulse being an inverted copy of the first and summing the resulting echo signals. This removes linear scattering. AM detects UCA echoes by sending two ultrasound pulses into tissue, scaling the signal in response to the second pulse, and subtracting successive echo signals [87]. This further removes linear scattering. For NBs, which respond better at higher frequencies, there are two confounding issues with the PI and AM methods. First, the amount of nonlinear tissue signal is greater at high frequencies than at low frequencies [88]. Second, US attenuation increases as a function of frequency in soft tissues[2]. For these reasons, optimizing the frequencies and amplitudes of the transmit pulses to maximize the CTR specifically for NBs, compared to existing microbubbles is a significant unmet need in the field.

The use of parametric dynamic contrast-enhanced US (DCE-US) imaging has been explored in numerous studies to measure contrast kinetics and assess tissue perfusion clinically and pre-clinically [89–93]. The technique relies on MB contrast agents, and exploits the real-time image acquisition, high signal to noise ratio of US to measure MB kinetics. Using non-destructive low mechanical index (MI 0.06-0.2 depending on vendor) nonlinear imaging, DCE-US is used to track the change in signal in a region of interest over time (represented by the Time-Intensity Curve or TIC) on a per pixel basis; these curves can be fitted with mathematical models related to tissue perfusion. DCE-US has been used to assess tumor angiogenesis and antiangiogenic therapy response [89, 90, 94, 95]. Because MBs are exclusively a blood-pool agent, DCE-US may enable accurate perfusion quantification. The NB signal could also provide kinetic information about tumor vascular permeability. Another unmet need is developing new pharmacokinetic models suitable for NBs and targeting NBs, which reflect extravascular activity in tumors [96].

Targeted nanobubbles in imaging applications:

A variety of NB constructs have been developed and tested in in vivo imaging applications. The platform nanoparticles in these studies have typically consisted of a lipid shell with additives, including porphyrins [97] and/or fluorescent dyes used for concurrent optical imaging and immunohistochemical analysis [98]. The main modifications and innovations in most published reports focus on surface functionalization approaches to create targeted NBs. Targeted NBs are attractive agents for molecular imaging and can detect biomarkers on target cells within the vasculature and beyond. Notably, the active targeting moieties have been shown to increase bubble extravasation and retention in tumors compared to untargeted NBs [69]. This approach is attractive for increasing the sensitivity of detection and improving drug delivery efficiency. A range of ligands have been explored. Ligands can be conjugated to lipids via standard conjugation chemistry, including the EDC/NHS reaction mechanism and the use of maleimide-thiol coupling chemistry. Early work also included the use of avidin/biotin complexes to functionalize the NBs, but more translational approaches have mostly replaced this approach. Full antibodies [99], peptides [98], affibodies [100] and nanobodies [101] have all been utilized as targeting moieties.

Two of the most developed areas for targeted-NB applications are prostate cancer and breast cancer imaging and therapy. These areas have a potentially significant and more immediate clinical impact since the use of ultrasound is common in the clinical workflow for disease diagnosis. In prostate cancer, the use of transrectal ultrasound is nearly ubiquitous during biopsies. Here, ultrasound is used to localize the prostate gland [102]. In breast cancer, ultrasound is used commonly to complement mammography and to guide biopsies of suspicious lesions. Thus, innovations in ultrasound contrast agents can increase cancer detection sensitivity and specificity with minor changes to the existing process. Targeting the prostate-specific membrane antigen (PSMA) in prostate cancer via various NBs has been investigated [69, 101, 103, 104]. In breast cancer, using Herceptin to target the Her-2 receptor and folate to target the folate receptor have shown promising results [105, 106].

Additional non-cancer applications have been investigated using NB contrast-enhanced ultrasound. For example, NBs were applied to detect asymptomatic type 1 diabetes in mice as recently reported by Ramirez et al. [107]. Since NBs can permeate the leaky vasculature, the NB signal within the endocrine diabetic pancreas was higher than that from normal mice. NBs were retained within the islets for an extended period. Furthermore, the agents showed increased preferential NB accumulation consistent with the severity of insulitis, allowing potential disease progression assessment.

There are three key challenges in NB development for diagnostic imaging applications. The first is a rigorous and meaningful interpretation of the TIC data when using dynamic parametric CEUS. The change in signal intensity over time within a region of interest (typically within a single imaging plane) can be a valuable parameter for describing vascular architecture in tumors and examining vascular density and heterogeneity and their changes in tumor development or following tumor treatment. However, many factors can influence the contrast kinetics and confound interpretation. These include biological effects such as macrophage uptake, and more general removal via the reticuloendothelial system, acoustic parameters such as the mechanical index (MI) and the imaging frame rate. The acoustic parameters determine the agent’s total exposure to ultrasound energy and, therefore, the longevity of the contrast agent exposed to ultrasound excitation. Likewise, the natural rate of dissipation of the gas from the agent shell will also govern the in vivo circulation time.

The second challenge is that target-bound NBs are vulnerable to rapid decay due to the continued exposure to the acoustic field. This could, in turn, contribute to more rapid signal decay compared to circulating NBs. However, if properly validated, TIC parameters such as the AUC and rate of signal wash-out could be key indicators of these processes, and have been shown to differ in targeted versus untargeted NBs [69]. Unraveling the extravascular and intravascular contributions to the TIC data is a key remaining challenge. For this reason, appropriate controls are needed for proper TIC interpretation. These controls should include microbubbles, which should describe the blood pool agent kinetics. However, caution should be taken to remove sub-micron bubbles from these solutions, which could complicate the microbubble data interpretation. Some nonspecific, non-selective accumulation is expected due to passive extravasation and cell uptake of untargeted nanobubbles and may confound the interpretation of imaging data. However, published studies comparing the acoustic activity of targeted versus untargeted NBs in vivo have shown that the washout of targeted NBs is significantly reduced compared to their untargeted counterparts [41]. This reduced washout may have to do with specific cellular internalization pathways, which may stabilize the targeted nanobubbles once they have entered the target cell. If this is shown to be the case, then nonspecific NB signal can be reduced given sufficient time (~30 min in mice), and the remaining signal is likely to be specific to the target.

Another challenge is the influence of bubble concentration and gas volume on bubble decay. Studies have shown that in both microbubbles and NBs, the signal’s decay rate increases with a decreased concentration and corresponding gas volume. Thus, these factors must be accounted for between experiments and carefully compared. If the optimal diagnostic agent and imaging properties are to be investigated, these will vary between formulations and between NBs and microbubbles. Thus what parameter should be normalized and how controls should be designed remain topics of investigation.

Therapeutic applications

Another key area of growth for NBs is in image-guided therapy. The use of NBs in image-guided therapy follows the well-developed concepts in nanomedicine. For example, a large body of work in nanomedicine has focused on exploiting the enhanced permeability and retention (EPR) in tumors to deliver the therapeutic payload [108]. The same challenges that have held back the development of successful nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems in cancer chemotherapy apply to NBs. These include the same physiological barriers to efficient delivery - foremost nanoparticle-blood interactions, scavenging of the nanoparticles by the reticuloendothelial system, complex blood-nanoparticle interactions, limited margination in flow, extravasation via the leaky endothelium and sufficient distribution within the tumor parenchyma. Another set of barriers, including the NB interaction with target cell membranes, cellular internalization, endosomal entrapment and escape, exist[86] [109]. These processes are relevant to the NBs’ diagnostic/functional imaging and therapeutic potential and need to be studied in depth.

However, when applying the decades of experience from nanoparticle transport studies to NBs, it becomes apparent that NBs have key advantages that make them uniquely suited for overcoming some of these barriers. As mentioned above, these are (a) buoyancy and low density that facilitate margination in blood vessels, (b) high concentration and (c) deformability owing to low elasticity, high deformability and low interfacial tension of the shell. These factors increase the probability of decreased RES uptake, and increased extravasation and movement through the extracellular space. This makes NBs an exciting vehicle for drug delivery to tumors and other pathologies.

Furthermore, NB transport and NB-drug delivery can be aided by US-driven cavitation and other US bioeffects - processes unique to this approach. The use of ultrasound for active, on-demand, delivery of drugs is a promising area of investigation. In these approaches, acoustic waves lead to an increase in the local energy absorbed, acoustic fluid streaming, cavitation of gas bubbles and mild hyperthermia, which, in turn, increase vascular permeability or trigger payload release from the carrier[110]. These strategies are either applied to various existing drug-loaded nanoparticles such as liposomes[111–114] or use US-visible microbubbles (MB, 1-10 μm in diameter, which remain in the blood vessels and cannot directly reach tumor cells) in combination with therapeutics[115, 116]. It is important to note that, upon injection into the bloodstream, the relatively low number density of MBs accessible to the target site at any one time is likely too low to elicit a strong therapeutic effect. In contrast, NB number density, which is 3 orders of magnitude greater, can provide sustained high levels of particles at the target site, which is likely to improve therapy outcomes. Figure 1D illustrates the difference between the two formulations.

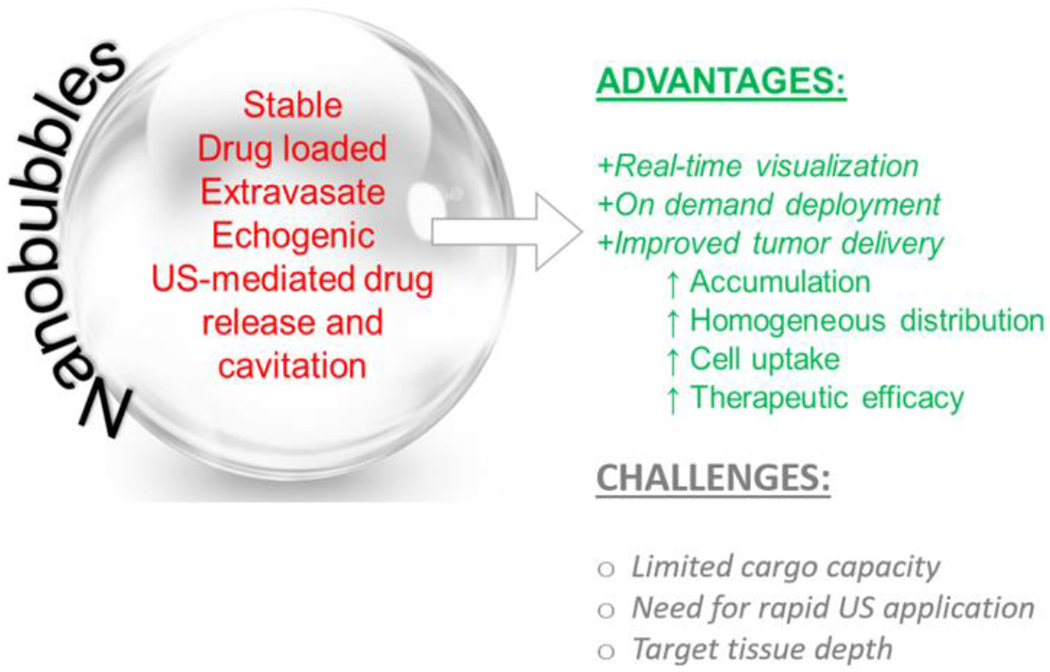

Nanoparticles are not easily visible on US at clinically-utilized frequencies without specialized imaging modes due to their small size and correspondingly high resonant frequency. In contrast, MBs generate strong contrast on clinical equipment and their cavitation can induce considerable bioeffects of vasculature and cell membranes [7]. However, they do not extravasate beyond the vasculature and are thus of limited utility in in vivo applications, which require them to be located proximal to the tumor cells. NBs combine characteristics of MBs and nanoparticle drug carriers into one simple platform that allow for a significant increase in therapeutic index of the delivered agent by penetrating the physiological and cell barriers that limit MB accessibility to intended target sites [31, 56, 117]. The highlights are summarized in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Summary of NB features and challenges in drug delivery

Other unique therapeutic applications of nanoscale contrast agents move beyond ultrasound-mediated drug delivery. These techniques often rely on highly localized ultrasound-induced cavitation (both stable and inertial) of bubbles at the target site. For example, gas vesicles have been recently utilized as molecular reporters for ultrasound imaging of gene expression in vivo [118] and neuromodulation [119]. NBs have been used as sensitizing probes for tumor-specific radiation therapy of prostate cancer [120] and as robust agents for opening the blood-brain barrier [121]. Overall, the capacity to elicit precise therapeutic effects using ultrasound-sensitive nanoscale contrast agents, whether drug-loaded or not, promises to enhance disease management.

Future perspectives and best practices

Key innovations will drive the field forward. Foremost, the efficient and reproducible production of NBs with a narrow, or ideally monodisperse, size distribution, and high yield (concentrations above 1011 NBs/mL) is critical to successful implementation of these agents. Developing monodisperse bubbles can amplify their acoustic activity and further increase the contrast to background signal in the target tissue. Optimizing ultrasound exposure parameters to monodisperse NBs may limit clinical use to a narrow range of applications and decrease the robustness of the agents to natural human variability. Nevertheless, the large increase in sensitivity demonstrated with monodisperse MBs when compared to polydisperse MBs suggests that this tradeoff may be warranted [122]. In combination with producing more monodisperse bubbles, shell engineering - manipulating the viscoelastic properties of bubble coating – will continue to yield significant benefits. Going a step further, model-based rational shell design can yield highly predictable, uniform and tunable acoustic responses. Theoretical modelling and numerical simulations can provide unique insight into the shell effect on the observed controllable acoustic behavior. Both of these advancements can aid in the production of NB libraries of established sizes that can be individually distinguished solely on their resonant frequency shifts or pressure-dependent nonlinear behavior. Such developments will serve to enable multiplex or multicolor ultrasound imaging to distinguish two or more targets simultaneously in the same imaging plane. The innovation in this space would inspire significant advancements in the molecular imaging field.

With all new formulation modifications, rigorous characterization of NBs must be carried out to confirm the (a) concentration, size distribution, stability, and (b) the acoustic activity of the NBs under physiological conditions, especially in whole human blood. The techniques need to have high sensitivity and a broad working range to detect buoyant particles of smaller diameters than currently feasible with RMM. Currently, the best practice is to use a suite of instruments (DLS, Coulter, RMM, TEM, SEM) coupled with headspace GC-MS validation. In addition, working in concert with bubble formulation, the optimization of imaging hardware (such as broader development of high frequency and 3D enabled transducers able to collect nonlinear data in real-time with a high frame rate), acoustic imaging parameters, pulse sequences and pharmacokinetic models to best take advantage of the unique NB properties, will be necessary to advance the field. Characterization of acoustic activity in a bubble population and on a single bubble basis would also provide insights into the acoustic activity for each new agent. Assessment via passive cavitation detection over a range of pressures and frequencies is necessary, especially for therapeutic formulations. This has already been recognized as an important dosimetric consideration in microbubble therapy[123], and will be necessary to implement for NB applications.

Multifunctional NBs are another area that is likely to see significant interest. NBs, which are magnetic via the inclusion of iron oxide nanoparticles within the shell, have been shown to have dual functions as US and MRI contrast agents [124]. They are also being applied as therapeutic moieties. Likewise, combinations of a strong optical absorber and gas core have led to the creation of dual-mode, acoustic and photoacoustic imaging agents, which have many exciting applications. Finally, multi-modality, MR, PA and US imaging and optical/fluorescent imaging probes are under development and can enable successful imaging and therapy and biopsy / surgical resection guidance [98, 125].

Inflammation is associated with a broad array of diseases, from cancer, to osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, CNS-related diseases such as Alzheimer’s disease and cardiovascular pathologies. Therefore, in principle, NB CEUS applications can be expanded to aid in the diagnosis, monitoring of progression, and assessing treatment outcomes of a broad collection of pathologies linked to inflammation. In addition, treatment of these diseases via NB-enhanced or NB-delivered technologies offers considerable promise. In cancer specifically, NBs are poised to have a role in more effective early diagnosis of a variety of tumors and early detection using novel biomarkers. Guidance of procedures – such as tumor biopsy and resection – is also an exciting area of investigation. EPR monitoring is another synergistic role for NBs that can be critical in potentially driving the field of nanomedicine forward. It may be possible that NB transport, as quantified by real-time contrast enhanced imaging, can serve as a tool for assessing vascular permeability and the extent of endothelial fenestrations. Can we apply the knowledge in pharmacokinetic modeling, combined with super-resolution signal and image processing techniques to quantify NB transport in a tissue of interest with high sensitivity? If these techniques can be adequately developed, NBs may then serve as a tool for assessing ‘extravasation potential’ of this target tissue and be used to predict therapeutic efficacy of nanomedicine-based therapeutics. Finally, the use of NBs to elicit an immune response due to mechanical disruption cells in-vivo (abscopal immune responses [126]) and monitor cancer immunotherapy outcomes via targeting of inflammation markers are also an exciting emerging area of investigation.

In addition to immunotherapy, significant advances in the use of NBs, or other nanoscale ultrasound contrast agents such as nanovesicles, will be seen in theranostic applications. Recent reports of gene therapy with nanovesicles show much promise in this area. Using NBs as highly focused delivery vehicles or sensitizers for radiation therapy, chemotherapy, and combination therapies promise to impact cancer treatment significantly [120]. Finally, neuromodulation[119], gene and drug delivery with NBs for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases will also emerge as significant areas of potential innovation and impact.

Finally, a note about clinical translation of nanobubble-base technologies. While there has now been a fair amount of preclinical evidence for the potential of contrast-enhanced ultrasound imaging with NBs, the work has been almost exclusively carried out in small rodents, and often without appropriate controls. Thus, a significant amount of work remains before NBs can make their way to routine human use. Achieving investigative new drug (IND) status with the FDA will require a considerable and concerted effort. Some crucial steps include: (a) scaling up preclinical work to larger animals, such as rabbits, dogs and nonhuman primates to demonstrate nanobubble safety and feasibility of NBs to achieve sufficient contrast at a clinically-appropriate penetration depth for extended time periods compared to mice; (b) toxicology studies in standard models carried out under Good Laboratory Practice (GLP) protocols, (c) working out challenges with formulation manufacturing, such as efficient scale-up and extended storage. In addition, the introduction of specific ligands for molecular imaging or image-guided therapy with contrast will both require additional, highly specialized sonication parameters to work in concert with the NBs and image processing algorithms, including augmentation of quantitative parametric analysis of the kinetic data and creation and validation of unique imaging biomarkers enabled by extravascular targeting. Introducing new software and new hardware capable of taking the best advantage of NBs technology in a specific application will require multicenter clinical trials and support from the appropriate professional societies to enable broad adoption.

Potential pitfalls of the NB agents in human use must also be considered. Namely, one apparent challenge could be the sensitivity of NB detection at low frequencies which are suitable for deeper targets. However, modern transducer technology has already sought to address challenges of penetration depth, and thus it is foreseen that the challenge could be relatively straightforward to address. The alternative could be to focus on applications specific to high-frequency ultrasound, which is currently already clinically utilized for “small parts” imaging applications such as prostate, thyroid, breast, and lymph as well as pediatric applications.

Conclusions

Existing at the interface of imaging physics, colloid science, and nanomedicine, NBs are a deceivingly simple system with broad potential to contribute to the field of biomedical ultrasound. Recent interest and research in the field have propelled NBs to a stage where they are now poised to be a significant driver of innovation in the ultrasound contrast agent field. The successful clinical translation of NB-based contrast agents depends on a better understanding of NB-ultrasound interactions and the establishment of a track record showing exceptional safety, low toxicity and clear imaging benefits in large animal models compared to existing microbubble agents. This will, in turn, drive exciting emerging applications in cancer diagnosis, molecular imaging, gene and drug delivery that can help enhance or change the management of many diseases.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Representative movies showing the dynamics of nanobubble and microbubble (MicroMarker®) enhancement in the same murine kidney in B-mode and nonlinear contrast mode. Images were acquired with the Visualsonics Vevo 2100 scanner at 18 MHz and 4% power.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the many members of the Exner and Kolios laboratories who have contributed to this work. From the Exner lab, especially big thanks go out to Dr. Al De Leon and Dr. Chris Hernandez, whose work on optimizing NB formulations has enabled many of the recent applications. We also acknowledge Dr. Eric Abenojar for his work in formulation and development of best practices for NB characterization, Drs. Reshani Perera and Hanping Wu for their contributions to in vivo bubble imaging. Special thanks also to Dr. James Basilion for his molecular biology expertise and insights into the PSMA-NB projects. We acknowledge funding from the U.S. Department of Defense, the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging and Bioengineering (NIBIB) of the National Institutes of Health and the Wallace E. Coulter Foundation that has supported this work.

From the Kolios lab, special acknowledgments to Dr. Amin Jafari Sojahrood that developed the theoretical models that used nonlinear analysis to provide critical insights into the NB physics, Hossein Hahghi for work with Dr. Sojahrood on microbubble and NB clusters and Elizabeth Berndl, Yang Wang, Dr. Xiaolin He and Dr. Darrren Yuen for collaborative work on kidney characterization that generated the data presented in Figure 2. Funding has been provided by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council and the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR). We also thank FUJIFILM VisualSonics and Siemens Healthineers for their contributions to advancing this work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Topol EJ. The patient will see you now: the future of medicine is in your hands. 2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Cobbold RS. Foundations of biomedical ultrasound: Oxford university press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- [3].Klibanov AL. Ultrasound Contrast: Gas Microbubbles in the Vasculature. Investigative Radiology. 2020;56:50–61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **[4].Frinking P, Segers T, Luan Y, Tranquart F. Three Decades of Ultrasound Contrast Agents: A Review of the Past, Present and Future Improvements. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2020;46:892–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Broad overview of the ultrasound contrast agent field. The work summarizes notable advancements in the field and outlines key future directions and emergent technologies that will guide the next decade of research in this area.

- [5].Erlichman DB, Weiss A, Koenigsberg M, Stein MW. Contrast enhanced ultrasound: A review of radiology applications. Clinical Imaging. 2020;60:209–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Gramiak R, Shah PM. Echocardiography of the aortic root. Investigative radiology. 1968;3:356–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Kooiman K, Vos HJ, Versluis M, de Jong N. Acoustic behavior of microbubbles and implications for drug delivery. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2014;72:28–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].van Rooij T, Daeichin V, Skachkov I, de Jong N, Kooiman K. Targeted ultrasound contrast agents for ultrasound molecular imaging and therapy. International Journal of Hyperthermia. 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Sidhu PS, Cantisani V, Deganello A, Dietrich CF, Duran C, Franke D, et al. Role of contrast-enhanced ultrasound (CEUS) in paediatric practice: an EFSUMB position statement. Ultraschall Med. 2017;38:33–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *[10].Czarnota GJ, Karshafian R, Burns PN, Wong S, Al Mahrouki A, Lee JW, et al. Tumor radiation response enhancement by acoustical stimulation of the vasculature. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2012;109:E2033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; First publication demonstrating the sensitizing effects of MB contrast agents in conjunction with radiation of tumors.

- [11].Eisenbrey JR, Shraim R, Liu J-B, Li J, Stanczak M, Oeffinger B, et al. Sensitization of hypoxic tumors to radiation therapy using ultrasound-sensitive oxygen microbubbles. International Journal of Radiation Oncology* Biology* Physics. 2018;101:88–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Stride E, Segers T, Lajoinie G, Cherkaoui S, Bettinger T, Versluis M, et al. Microbubble agents: New directions. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Unnikrishnan S, Klibanov AL. Microbubbles as ultrasound contrast agents for molecular imaging: preparation and application. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:292–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Klibanov AL, Rasche PT, Hughes MS, Wojdyla JK, Galen KP, Wible JH Jr., et al. Detection of individual microbubbles of ultrasound contrast agents: imaging of free-floating and targeted bubbles. Invest Radiol. 2004;39:187–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Klibanov AL, Hughes MS, Villanueva FS, Jankowski RJ, Wagner WR, Wojdyla JK, et al. Targeting and ultrasound imaging of microbubble-based contrast agents. MAGMA. 1999;8:177–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **[16].Klibanov AL. Preparation of targeted microbubbles: ultrasound contrast agents for molecular imaging. Med Biol Eng Comput. 2009;47:875–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Excellent review of targeted microbubbles used for ultrasound molecular imaging. The paper describes various targeting strategies, and provides recommendations and best practices for the microbubble functionalization process.

- [17].Lampaskis M, Averkiou M. Investigation of the Relationship of Nonlinear Backscattered Ultrasound Intensity with Microbubble Concentration at Low MI. Ultrasound in Medicine & Biology. 2010;36:306–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Unger EC, Porter T, Culp W, Labell R, Matsunaga T, Zutshi R. Therapeutic applications of lipid-coated microbubbles. Advanced drug delivery reviews. 2004;56:1291–314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Chin CT, Burns PN. Predicting the acoustic response of a microbubble population for contrast imaging in medical ultrasound. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2000;26:1293–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Oeffinger BE, Wheatley MA. Development and characterization of a nano-scale contrast agent. Ultrasonics. 2004;42:343–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *[21].Wheatley MA, Forsberg F, Dube N, Patel M, Oeffinger BE. Surfactant-stabilized contrast agent on the nanoscale for diagnostic ultrasound imaging. Ultrasound in medicine & biology. 2006;32:83–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; First report demonstrating in vivo imaging of nanoscale contrast agents using standard clinical equipment and pulse sequences.

- [22].Rapoport N, Gao Z, Kennedy A. Multifunctional nanoparticles for combining ultrasonic tumor imaging and targeted chemotherapy. Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 2007;99:1095–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **[23].Krupka TM, Solorio L, Wilson RE, Wu H, Azar N, Exner AA. Formulation and characterization of echogenic lipid-Pluronic nanobubbles. Mol Pharm. 2010;7:49–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; One of the first experimental reports of lipid-shell stabilized, perfluoropropane nanobubbles, suggesting that shell composition and, in particular, the inclusion of the nonionic surfactant Pluronic, into the nanobubble shell can significantly affect the formulation outcomes and the imaging performance of the nanobubbles.

- [24].Wang Y, Li X, Zhou Y, Huang P, Xu Y. Preparation of nanobubbles for ultrasound imaging and intracelluar drug delivery. International journal of pharmaceutics. 2010;384:148–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Xu JS, Huang J, Qin R, Hinkle GH, Povoski SP, Martin EW, et al. Synthesizing and binding dual-mode poly (lactic-co-glycolic acid)(PLGA) nanobubbles for cancer targeting and imaging. Biomaterials. 2010;31:1716–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Wang CH, Huang YF, Yeh CK. Aptamer-conjugated nanobubbles for targeted ultrasound molecular imaging. Langmuir. 2011;27:6971–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Yin T, Wang P, Zheng R, Zheng B, Cheng D, Zhang X, et al. Nanobubbles for enhanced ultrasound imaging of tumors. Int J Nanomedicine. 2012;7:895–904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Yin T, Wang P, Zheng R, Zheng B, Cheng D, Zhang X, et al. Nanobubbles for enhanced ultrasound imaging of tumors. International journal of nanomedicine. 2012;7:895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Fan X, Wang L, Guo Y, Tong H, Li L, Ding J, et al. Experimental investigation of the penetration of ultrasound nanobubbles in a gastric cancer xenograft. Nanotechnology. 2013;24:325102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Cai WB, Yang HL, Zhang J, Yin JK, Yang YL, Yuan LJ, et al. The optimized fabrication of nanobubbles as ultrasound contrast agents for tumor imaging. Scientific reports. 2015;5:13725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Yang H, Deng L, Li T, Shen X, Yan J, Zuo L, et al. Multifunctional PLGA nanobubbles as theranostic agents: combining doxorubicin and P-gp siRNA co-delivery into human breast cancer cells and ultrasound cellular imaging. Journal of biomedical nanotechnology. 2015;11:2124–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Alheshibri M, Qian J, Jehannin M, Craig VS. A history of nanobubbles. Langmuir. 2016;32:11086–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- **[33].de Leon A, Perera R, Hernandez C, Cooley M, Jung O, Jeganathan S, et al. Contrast enhanced ultrasound imaging by nature-inspired ultrastable echogenic nanobubbles. Nanoscale. 2019;11:15647–58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; This work demonstrates how bubble shell engineering can impact imaging performance of nanobubbles. Specifically, inclusion of edge activators, such as propylene glycol, and known stiffeners, such as glycerol, and the interplay between these and the lipid shells, can have a drastic and direct impact on nanobubble stability, resilience to dissolution, circulation time and acoustic activity.

- **[34].Hernandez C, Abenojar EC, Hadley J, de Leon AC, Coyne R, Perera R, et al. Sink or float? Characterization of shell-stabilized bulk nanobubbles using a resonant mass measurement technique. Nanoscale. 2019;11:851–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; Demonstration and validation of resonant mass measurement as a characterization method for nanobubble size and concentration.

- [35].Abenojar EC, Nittayacharn P, de Leon AC, Perera R, Wang Y, Bederman I, et al. Effect of Bubble Concentration on the in Vitro and in Vivo Performance of Highly Stable Lipid Shell-Stabilized Micro-and Nanoscale Ultrasound Contrast Agents. Langmuir. 2019;35:10192–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Hernandez C, Gulati S, Fioravanti G, Stewart PL, Exner AA. Cryo-EM visualization of lipid and polymer-stabilized perfluorocarbon gas nanobubbles-a step towards nanobubble mediated drug delivery. Scientific reports. 2017;7:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Hernandez C, Nieves L, de Leon AC, Advincula R, Exner AA. Role of Surface Tension in Gas Nanobubble Stability Under Ultrasound. ACS Appl Mater Interfaces. 2018;10:9949–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].JafariSojahrood A, Nieves L, Hernandez C, Exner A, Kolios MC. Theoretical and experimental investigation of the nonlinear dynamics of nanobubbles excited at clinically relevant ultrasound frequencies and pressures: The role oflipid shell buckling. 2017 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS): IEEE; 2017. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- [39].Pellow C, Abenojar EC, Exner AA, Zheng G, Goertz DE. Concurrent visual and acoustic tracking of passive and active delivery of nanobubbles to tumors. Theranostics. 2020;10:11690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Wu H, Abenojar EC, Perera R, De Leon AC, An T, Exner AA. Time-intensity-curve Analysis and Tumor Extravasation of Nanobubble Ultrasound Contrast Agents. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2019;45:2502–14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Perera R, DeLeon A, Wang X, Ramamurtri G, Peiris P, Basilion J, et al. Nanobubble Extravasation in Prostate Tumors Imaged with Ultrasound: Role of Active versus Passive Targeting. 2018 IEEE International Ultrasonics Symposium (IUS): IEEE; 2018. p. 1–4. [Google Scholar]

- [42].Noguchi H, Takasu M. Self-assembly of amphiphiles into vesicles: a Brownian dynamics simulation. Physical Review E. 2001;64:041913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Alexandridis P, Lindman B. Amphiphilic block copolymers: self-assembly and applications: Elsevier; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- [44].Alkan-Onyuksel H, Demos SM, Lanza GM, Vonesh MJ, Klegerman ME, Kane BJ, et al. Development of inherently echogenic liposomes as an ultrasonic contrast agent. Journal of pharmaceutical sciences. 1996;85:486–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Kopechek JA, Haworth KJ, Raymond JL, Douglas Mast T, Perrin SR Jr, Klegerman ME, et al. Acoustic characterization of echogenic liposomes: Frequency-dependent attenuation and backscatter. The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America. 2011;130:3472–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Sheeran PS, Matsuura N, Borden MA, Williams R, Matsunaga TO, Burns PN, et al. Methods of Generating Submicrometer Phase-Shift Perfluorocarbon Droplets for Applications in Medical Ultrasonography. IEEE Trans Ultrason Ferroelectr Freq Control. 2017;64:252–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Perera RH, Solorio L, Wu H, Gangolli M, Silverman E, Hernandez C, et al. Nanobubble ultrasound contrast agents for enhanced delivery of thermal sensitizer to tumors undergoing radiofrequency ablation. Pharm Res. 2014;31:1407–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Wu H, Rognin NG, Krupka TM, Solorio L, Yoshiara H, Guenette G, et al. Acoustic characterization and pharmacokinetic analyses of new nanobubble ultrasound contrast agents. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2013;39:2137–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Hernandez C, Nieves L, de Leon AC, Advincula R, Exner AA. Role of Surface Tension in Gas Nanobubble Stability Under Ultrasound. ACS applied materials & interfaces. 2018;10:9949–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]