Abstract

Ninety-nine percent of global maternal deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries. The high mortality rates are often attributed to a large portion of births occurring outside of formal health care facilities. This has prompted the creation of programs to promote the use of formal delivery care. However, poor-quality care in health facilities in low- and middle-income countries is well documented. It is not clear that shifting births into health facilities in these settings necessarily leads to better-quality care. We present results from a randomized controlled trial in Nigeria that evaluated a conditional cash transfer intervention that paid pregnant women to deliver in a health facility. We found that the intervention led to a 41 percent increase in facility deliveries. We also found improvements in the quality of delivery care (as a result of more births taking place in formal health care settings) and in overall satisfaction with care. We found no evidence of a reduction in preventable complications that led to maternal deaths, though we found some improvements in self-reported health. Our results indicate that promoting facility deliveries can improve the quality of care received, even in settings where formal care quality is poor. However, modest quality improvements might not be sufficient to substantially improve health outcomes.

About 300,000 maternal deaths occur annually worldwide, or more than 800 deaths per day.1 Ninety-nine percent of these deaths occur in low- and middle-income countries, where many women do not deliver in a health facility.2 The primary causes of maternal death, such as hemorrhage and sepsis,3 are all treatable or preventable with existing health technology that is often not available outside of a health facility. Increasing use of formal health services by pregnant women, therefore, has the potential to save many thousands of lives and help achieve policy targets set forth in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals that countries agreed to achieve by 2030.4

These facts have led to the growing popularity of programs designed to increase the use of health services among pregnant women, such as antenatal care and institutional care at birth.5 Programs such as cash transfers conditional on service use and vouchers for free services are now available in dozens of low- and middle-income countries. Studies from Latin America, sub-Saharan Africa, and Asia have demonstrated that such programs can effectively increase the take-up of maternal health services.5 However, whether these programs lead to better maternal health outcomes remains unclear.5,6

For programs that increase service use to improve maternal outcomes, they must lead to better-quality care for pregnant women. However, the poor quality of maternal care in low- and middle-income countries is well documented.7 Many women believe that formal birth attendants within the health system do not provide better care than informal birth attendants, also known as traditional birth attendants,8 and there is some evidence that they may be right.9 If increasing service use does not significantly improve the quality of care received, then there is little reason to expect improvements in maternal outcomes. Alternatively, if commonly used facilities lack necessary lifesaving technology, then increasing use might not lead to significant reductions in mortality. For example, evaluations of a large conditional cash transfer (CCT) program in India found that while it increased rates of institutional births, it had no discernible effect on maternal mortality.10,11 One possible explanation is low quality of care in health institutions. Clearly, much more evidence is needed on whether demand-side interventions can achieve their intended purpose of increasing quality and delivering better maternal health outcomes.5,12

This article reports the results of a randomized controlled trial in Nigeria that evaluated the effect of CCTs on the quality of delivery care received and on maternal health. We also examined whether the effects on maternal health depended on the capability of the facility to provide emergency obstetric care.13

Study Data And Methods

SETTING AND POLICY CONTEXT

Nigeria is the most populous country in Africa, with an estimated population of over 180 million people. It is the second-largest contributor to maternal deaths worldwide.2 In a report assessing the well-being of mothers and children in various countries around the world, Nigeria was ranked 171 out of 178 countries.14

Use of maternal health services in Nigeria is low: 33 percent of women in the country do not receive any prenatal care, and only 39 percent of births take place in a health care facility.15 There is significant heterogeneity in outcomes across regions, with the northern regions—particularly the North-East and North-West—having the worst indicators. For example, while 39 percent of Nigerian women used a health facility for delivery, only 25 percent and 16 percent in these two regions, respectively, did so.15

STUDY PARTICIPANTS AND INTERVENTON

This randomized controlled trial was conducted in 180 primary health facility service areas. Each of these areas consists of households served by a public primary health care facility. On average, the health facility service areas serve about 7,000 people, so the participating areas covered more than 1.2 million people. The participating areas were drawn from five states: Akwa Ibom (in the South), Bauchi and Gombe (North-East), and Jigawa and Kano (North-West). We chose two states each from the North-East and North-West because of the regions’ poor indicators. To increase generalizability, we also chose one state from the South-South region (the South-South region has the worst outcomes in the South). The specific states were chosen in consultation with our local partner, a well-known university-based research group. In each state the participating areas were chosen with the help of government health officials. The selected facilities had to offer prenatal and delivery services and were predominantly located in rural and semirural communities.

Census areas within each health facility service area were randomly assigned to either the intervention or the control group with equal probability (that is, each area served as a single randomization block).16 Households in intervention areas were offered cash payments of 5,000 Naira (approximately US$14 at the prevailing exchange rate), conditional on the use of prenatal, delivery, and postnatal care by eligible pregnant women in the household. For context, the payment amount was equivalent to about 30 percent of monthly household food expenditures.17 It was also equivalent to the weighted average total cost of a facility birth (with costs weighted by the fraction of births in each facility setting and including transportation costs).

Program implementation was carried out by our local partner. Rollout visits took place in the period March–August 2017. During the rollout, field personnel employed by our partner met with community heads and went house to house to identify all households in the census area with an eligible woman (someone in her first or second trimester of pregnancy). We restricted the program to such households to allow pregnant women enough time to attend the required number of prenatal visits. In each eligible household the pregnant woman was interviewed, after which the program and its conditions were announced. To receive the $14, women had to meet all of the conditions: at least three prenatal visits, a health facility delivery, and at least one postnatal visit. Verification and payment would be made at a follow-up visit after the birth of the child.

Based on budgetary and sample size considerations, the target enrollment number was sixty women per health facility service area. Field personnel visited randomly drawn census areas until they reached this target. All eligible women in a census area who agreed to participate were enrolled in the program. In census areas assigned to the control arm, the same protocol was followed (except for the announcement of the program and its conditions). All households were reminded about the importance of seeking proper care during pregnancy and delivery.

This study provides some of the first robust evidence to link demand-side incentives to higher-quality delivery care.

FOLLOW-UP VISITS

Field personnel returned to the study communities in the period September 2017–August 2018. During these follow-up visits they returned to households where participating women had given birth. On average, follow-up visits were conducted about three months after the birth. If the woman had died, proxy interviews were conducted with a knowledgeable household member—typically the spouse. Verification of health care use was done using health cards and other available documentation. In intervention areas, women who met all of the conditions were paid in cash. Independent verification and payment were performed by a team supervisor. In cases where satisfactory documentation could not be provided, health care use was verified directly from health facility registers (in these cases, women were paid during a later visit). Participating women in control areas received small gifts (with a monetary value of $0.43) for participating in the study. Receipt of these gifts was not announced at baseline.

PARTICIPANT SURVEYS

All study participants were interviewed at baseline and follow-up. The baseline interview collected information about individual and household characteristics and any prior births. The follow-up interview collected information about health care use and delivery complications. The 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-12) was also administered to participants to measure general health.18,19

HEALTH FACILITY SURVEYS

Data were also collected from the health facility service areas’ facilities. Information was collected about staffing, opening and closing times, availability of equipment and supplies, and basic emergency obstetric capability. We assessed the facilities’ ability to carry out six basic emergency obstetric care “signal” functions (described in the online appendix).20 Data collectors also observed and recorded the overall cleanliness of the facilities and the state of their infrastructure.

OUTCOMES

We evaluated the impact of the conditional cash transfer intervention on five outcome domains: the use of delivery care, quality of delivery care, satisfaction with care, delivery complications, and mothers’ general health. (See the appendix for a complete description of how each outcome was constructed.)20

USE OF CARE: The primary outcome was whether the women gave birth in a health facility, a key objective of the intervention. We also examined the type of attendant present at the birth.

QUALITY OF CARE: We assessed measures related to the technical and interpersonal aspects of quality of care, two key elements outlined in a recent report from the National Academies of Science, Engineering, and Medicine.21 (See the appendix for descriptions of the indicators.)20

SATISFACTION WITH CARE: Delivering patient-centered care is an important health policy goal, and overall patient satisfaction is one measure of patients’ experiences with care. We used a five-point scale to assess overall satisfaction with the care the patients received.

DELIVERY COMPLICATIONS: We examined two specific complications—postpartum hemorrhage and infections—that account for nearly two in five global maternal deaths.3 We focused on these two outcomes not only because of their importance, but also because it is well known that they can be prevented.22–24 We examined the effect of the intervention on the rates of these two complications and the overall complication rate.

MOTHER’S GENERAL HEALTH: We used responses to the SF-12 to create a physical health index, based on the work of John Ware and coauthors.18 We also report the general health measure associated with the SF-12 to provide a sense of overall well-being as reported by respondents.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

We assessed the effect of the CCT intervention on each outcome, using an intention-to-treat framework. Our unit of observation was a birth. The key explanatory variable was an indicator that denoted assignment to the CCT arm. We estimated an unadjusted model and an adjusted model for each outcome. In the unadjusted model, we included only a set of indicator variables for each health facility service area, because randomization was stratified by area.25 For the adjusted model, we added a set of covariates that we expected to be predictive of our outcomes: mother’s age, ethnicity, education, number of prior births, history of previous birth outcomes such as prior stillbirths, dummies for each household wealth quintile (constructed using principal component analysis), time between the interview and the birth, and interaction of birth year and birth month (birth year × birth month) fixed effects to control for seasonal effects. The addition of these variables could have corrected bias in our treatment effect if there were covariate imbalance by chance, but their main purpose was to improve the precision of our estimates.

We used linear probability models for binary outcomes and ordinary least squares for continuous outcomes. We chose linear models instead of logistic models because the latter are known to be biased in a setting (such as ours) with high dimensional fixed effects (we used health facility service area fixed effects for the 180 unique areas).26 Census areas were not randomly sampled from the population: We first sampled health facility service areas and then sampled census areas within those areas. Therefore, we clustered the standard errors at the level of the health facility service area.27

MULTIPLE HYPOTHESIS TESTING

To account for multiple hypothesis testing, following the work of Michael Anderson28 we aggregated related outcomes within each of the five domains into a single index and then tested whether the intervention had an effect on the index. Specifically, we created indices for each domain for quality of care and birth complications. To create the indices, we standardized each out come against the control group and then took a weighted average of standardized outcomes within the same family. By aggregating all outcomes into a single index, we accounted for potential bias associated with testing multiple outcomes.

HETEROGENEITY

We hypothesized that the quality of delivery care might be an important mediator of health outcomes. Specifically, we tested the hypothesis that the intervention would have a stronger effect on health outcomes when a health facility service area was served by a higher-quality health facility relative to a lower-quality facility. To assess this, we constructed a capabilities index (we refer to this loosely as “quality”) for the health facility that served each study area (78 percent of facility births in the control group took place in the relevant health facility). The list of indicators is in the appendix.20 The use of this methodology for quality assessment is fairly standard in the literature.29,30 We divided the continuous index into quartiles and assigned each area facility to one of the quartiles. In our analysis, we interacted each quartile dummy with the treatment indicator to assess whether facility quality modified the effect of the CCT intervention. We also assessed heterogeneity by wealth, education, and pregnancy risk factors (see the appendix).20 For each modifier, we included a set of terms that interacted the CCT indicator with the categories of the modifier variable.

ETHICAL APPROVAL

Ethical approval for the study was given by RAND’s Human Subjects Protection Committee and the Ethics Committee of Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, in Nigeria.

LIMITATIONS

Our results should be interpreted in light of the study’s limitations. First, all of our outcomes relied on self-reporting. In settings such as our study’s, where a large number of births take place outside formal institutions, this is often the only way to collect data on outcomes. There is a possibility of inaccurate recall, which could have led to measurement error in the outcome. This might have introduced noise into the estimates and made it harder to detect an effect.

Second, our study was underpowered to assess other important (but rare) maternal health outcomes, such as maternal mortality. We only had forty-three deaths in our study population, so our study lacked statistical power to detect meaningful changes in that outcome. To be adequately powered to look at maternal mortality, the sample would need to be much larger. Instead, we focused on examining intermediate outcomes known to be key causes of maternal mortality.

Study Results

STUDY PARTICIPANTS

Overall, the intervention and control groups were well balanced on covariates at baseline (exhibit 1). There were 10,852 study participants who were enrolled in 2,383 census areas, of which 1,248 were allocated to the conditional cash transfer intervention arm and 1,135 to the control arm (see appendix figure A1 for the CONSORT flow diagram).20 Of these participants, 266 dropped out or were lost to follow-up before the final assessment. The dropout rate was slightly higher in the control group than in the intervention group (3 percent versus 2 percent). We had follow-up data for 10,586 women. Of the women for whom we had follow-up data, 9,410 gave birth. These women made up the analytical sample.

Exhibit 1.

Summary sample statistics of the study of a conditional cash transfer (CCT) for delivery care in Nigeria

| CCT (n = 5,259) | Control (n = 4,151) | p value of difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mother characteristics | |||

| Mean age, years | 24.77 | 24.57 | 0.16 |

| Mean number of prior births | 1.93 | 1.87 | 0.29 |

| Married | 95.6% | 95.0% | 0.30 |

| Completed primary school | 27.9 | 26.5 | 0.35 |

| Could read | 26.1 | 23.0 | 0.06 |

| Religion was Islam | 82.4 | 81.7 | 0.60 |

| Was currently working | 40.7 | 43.4 | 0.11 |

| Had bank account | 14.2 | 14.0 | 0.83 |

| Household characteristics | |||

| Main source of water was tap | 63.9% | 64.1% | 0.93 |

| Finished roof | 56.7 | 55.1 | 0.44 |

| Wealth quintile | |||

| 1 | 18.0 | 19.3 | 0.42 |

| 2 | 19.1 | 19.4 | 0.82 |

| 3 | 20.5 | 19.9 | 0.65 |

| 4 | 21.2 | 20.7 | 0.74 |

| 5 | 21.2 | 20.7 | 0.76 |

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from household surveys carried out by the authors during 2017 and 2018.

NOTEp values are from a test of difference between the treatment and control arms and were estimated using standard errors clustered on the health facility service area.

Given the design, the sample should have been evenly distributed between the intervention and control arms. The imbalance came from one state, Gombe, where two-thirds of the sample was in the intervention group. In the other states the sample was evenly distributed, as expected. Further analysis suggested that field personnel in Gombe selectively enrolled more women in census areas allocated to the intervention. Debriefings suggested that this was done out of a desire for as many women as possible to benefit from the cash transfer (that is, for partly altruistic reasons). As a sensitivity check, we examined whether the results were sensitive to exclusion of people in Gombe from the analysis.

EFFECT ON UTILIZATION

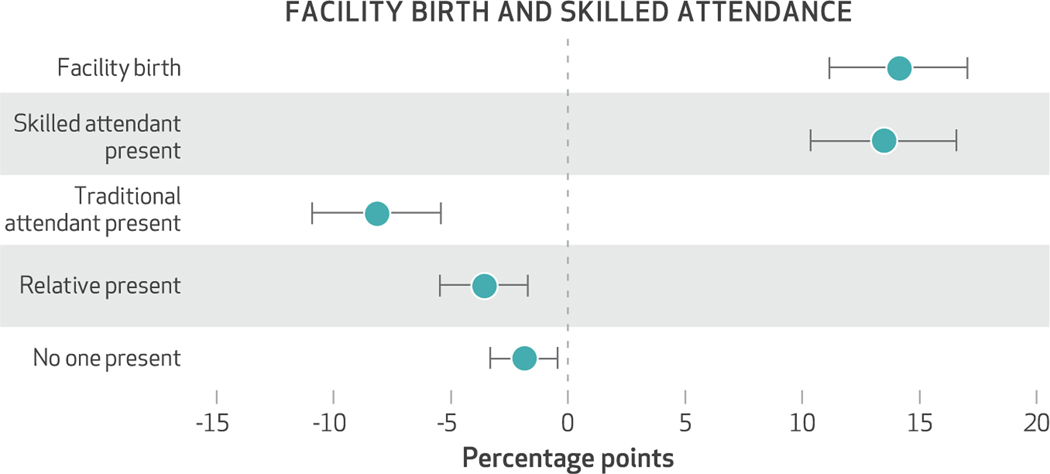

The CCT intervention led to a substantial increase in the use of health services. Women in the treatment group were 14 percentage points more likely to deliver in a health facility (exhibit 2), a 41 percent increase relative to the control group (control-group means are in appendix table A1).20 This increased the probability that a skilled birth attendant was present during the birth by 14 percentage points (a 37 percent increase). This increase was a result of women moving away from informal sources of delivery care. Women in the CCT arm were significantly less likely to use a traditional birth attendant (8 percentage points), a relative change of 4 percentage points, or to have an unattended birth (2 percentage points). Covariate-adjusted results in all cases were similar to the unadjusted results. (Appendix table A1 presents means of our study outcomes as well as unadjusted and adjusted differences between arms.)20 Unadjusted models included fixed effects only for health facility service areas, to account for the stratified design.

Exhibit 2. Percentage-point differences in facility birth and skilled attendance between the treatment and control arms of the study of a conditional cash transfer for delivery care in Nigeria.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from household surveys carried out by the authors during 2017 and 2018. NOTES Each point represents a coefficient from a separate linear probability model that regressed the relevant outcome on the conditional cash transfer indicator, controlling for mother’s age, ethnicity, education, number of prior births, prior birth history (history of stillbirths, miscarriages, or abortions), dummies for each household wealth quintile (constructed using principal component analysis), time between the interview and the birth, birth year × month fixed effects, and health facility service area fixed effects. The error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals that were estimated using standard errors clustered by the health facility service area.

EFFECT ON THE QUALITY OF DELIVERY CARE

The CCT intervention led to significant improvements in the quality of delivery care received by participants as a result of the shift in births to health facilities. Women in the treatment group were 8 percentage points more likely to have received oxytocin after birth (exhibit 3), a 27 percent increase (control-group means are in appendix table A1); 4 percentage points more likely to have received controlled cord traction, an after-delivery procedure (that is, an increase of 11 percent); 4 percentage points (an increase of 10 percent) more likely to have received uterine stimulation during labor; and 4 percentage points (an increase of 41 percent) more likely to have received medication to ease labor pain. We also found significant improvements in interpersonal quality. Women in the treatment group were substantially less likely to report being physically or verbally abused or mistreated by those providing delivery care. Covariate adjustment did not have a meaningful effect on our estimates. Quality as measured by the weighted index increased by 0.1 standard deviations. Appendix figure A2 graphically represents the estimated effects.20

Exhibit 3. Percentage-point differences in the quality of delivery care between the treatment and control arms of the study of a conditional cash transfer for delivery care in Nigeria.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from household surveys carried out by the authors in 2017 and 2018. NOTES Each point represents a coefficient from a separate linear probability model that regressed the outcome on the conditional cash transfer indicator, controlling for the variables listed in the notes to exhibit 2. The error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals, as explained in the notes to exhibit 2. Receipt of oxytocin, controlled cord traction, uterine stimulation, and pain medication during labor represent technical quality. Having no physical or verbal mistreatment by delivery care providers represents interpersonal quality. “Cord traction” is explained in the text.

EFFECT ON SATISFACTION WITH CARE

Consistent with women receiving higher-quality care, we found a substantive increase in satisfaction with care (appendix table A1).20 Women in the intervention group were 3 percentage points (3.6 percent) more likely to report being “very satisfied” with the care they received.

EFFECT ON MATERNAL HEALTH

Despite the significant improvements in quality, we found no evidence that the treatment led to a reduction in preventable delivery complications (exhibit 4). Differences between the intervention and control arms were close to zero, though the confidence intervals were fairly wide. Aggregating these outcomes into a single index helped increase our ability to detect same-signed effects. We examined the delivery complications index (appendix figure A2).20 Here again we found no evidence of a reduction in complications. The confidence intervals were narrower, and we could rule out reductions larger than 0.02 standard deviations.

Exhibit 4. Percentage-point differences in maternal health between the treatment and control arms of the study of a conditional cash transfer for delivery care in Nigeria.

SOURCE Authors’ analysis of data from household surveys carried out by the authors during 2017 and 2018. NOTES Each point represents a coefficient from a separate linear probability model that regressed the outcome on the CCT indicator, controlling for the variables listed in the notes to exhibit 2. The error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals, as explained in the notes to exhibit 2.

However, we did find evidence of a modest improvement in general (self-reported) health. Women in the CCT arm reported a higher general health score, on average, and were 3 percentage points more likely to report having one of the two highest general health ratings, relative to the control group (exhibit 4). There was no improvement in the physical health index generated from the SF-12 (appendix figure A2).20 Next we examined whether health effects might be moderated by the obstetric capability of the health facility.

HETEROGENEITY

While we did not find an improvement in birth complications on average, this could be because many women lived in areas where the primary health facility did not have the necessary capability (or lacked the technology) to avert these complications. For example, while we found an improvement in the average quality of care received, because more women gave birth in health facilities, many of the women who gave birth in a facility as a result of the CCT intervention did not, in fact, receive better quality care. It is possible that the CCT intervention would have a more positive effect on health in areas where the health facility was of higher quality. To address this possibility, we conducted analyses that compared the effect of the CCT intervention on complications for women in health facility service areas with a higher-quality primary health facility, relative to complications for women in areas with a lower-quality facility (appendix figure A3).20 We found no evidence that living in an area served by a higher-quality facility led to fewer complications.

We also assessed heterogeneity in the CCT effect by household wealth, mother’s level of schooling, and mother’s pregnancy risk factors. We found no difference in the CCT effect by household wealth (appendix figure A4).20 The CCT appears to have increased facility deliveries more for women with no formal education and for women who attended Islamic school than for women with at least primary traditional education (appendix figure A5),20 though this difference was not significant. There was no difference in the effect on quality or complications by mother’s education. Appendix figure A620 presents some evidence that the CCT increased facility births by more for women with zero or one pregnancy risk factor than for women with at least two risk factors, but there was no difference in the effect on quality or complications.

SENSITIVITY ANALYSIS

We conducted several sensitivity analyses, all of whose results are presented in the appendix.20 First, we found very similar results when we excluded Gombe from the analysis (appendix table A2).20 Second, clustering standard errors by census area instead of by health facility service area reduced standard errors slightly but did not qualitatively change the results (appendix table A3).20 Finally, we tested the sensitivity of our results to differential attrition by constructing bounds assuming that all attriters in the CCT arm had negative outcomes and all attriters in the control arm had positive outcomes (and vice versa). Appendix table A4 shows that our utilization and quality results were robust even under the most extreme assumptions about attriters.20

Discussion

We have shown that a conditional cash transfer intervention in Nigeria in which households received a payment of $14 conditional on the uptake of maternal health care led to substantial improvements in institutional delivery and the presence of skilled birth attendants, both important policy objectives.31 As a result, the quality of delivery care was higher, and women reported higher levels of satisfaction with care. This study provides some of the first robust evidence to link demand-side incentives to higher-quality delivery care, and it fills a large gap in the literature.5

Despite the positive effects of the intervention on utilization and quality, we found little evidence of improvements in maternal health.32 The only positive finding was a modest improvement in general self-reported health. This result echoes previous findings by Bharat Randive and coauthors,11 who found no effect of the Janani Suraksha Yojana program in India on maternal deaths. However, it diverges from findings by Edward Okeke and A. V. Chari,33 who found that women deterred from delivering in a health facility by heavy rainfall experienced more delivery complications. We examined whether heterogeneity in the quality of health facilities used might help explain this result, hypothesizing that health gains might be larger for women who lived in areas served by a more capable health facility. We found no evidence that this was the case. It is important, though, to stress that our measurements of health facility quality were relative to other facilities in the sample. Even a “higher-quality” facility in our sample was arguably low quality in an absolute sense. Only 7 of the 180 (4 percent) facilities scored above 75 percent on the capabilities index. Further driving this point home, only 27 percent of facilities in the top quartile had an antishock garment (a technology that might help save the life of a hemorrhaging woman). It may also be that our measure of quality was not “sharp” enough, and we may have missed important dimensions of facility quality.

How should we think about the lack of a strong effect on maternal health? Should we conclude that there is no value (in terms of women’s health) to incentivizing deliveries in a health care facility? We believe that the answer to this is no. First, we have shown that the intervention led to overall improvements in the quality of delivery care (primarily because more births took place in higher-quality settings). By itself, this is an important and desirable policy outcome, and over the long run, it might be expected to lead to reductions in maternal morbidity and mortality.

Second, it is worth noting that while the proportional increase in the quality of delivery care was large (10–41 percent), the absolute increase was only 4–8 percentage points. This might not be large enough to translate into significant health improvements, especially when one considers the relative rarity of these outcomes.

Third, we did not have data on when women arrived at health facilities. If women started laboring at home and only went to the facility if they had difficulty giving birth, then we might not expect to see a large reduction in complications. This is because even though the women did give birth in a health facility, whether or not they experienced complications was, in some sense, determined before their arrival.34

Policy Implications

Our findings have three main implications. First, they show unambiguously that conditional incentives lead to greater use of health services and better quality.

Second, the fact that we did not find evidence of a reduction in delivery complications (though there was some evidence of an improvement in self-reported health) suggests that demand-side incentives alone might not lead to large reductions in maternal deaths. It is likely that improvements in the capabilities of health facilities used by households will be needed to achieve policy goals. It is also important not to forget that health workers play a critical role in determining outcomes.35 If health workers are not properly trained and incentivized to do their best, upgrading facilities might not be enough to significantly shift outcomes.36

Third, despite the success of the intervention at increasing facility deliveries, nearly half of the women in the intervention arm still did not deliver in a health facility. This suggests that incentives are not a cure-all, and one must address other prevailing constraints.

Conclusion

This study has presented new evidence on the effectiveness of conditional cash incentives in improving the uptake of maternal health care, the quality of care, and maternal health outcomes in Nigeria. We have shown that the intervention led to significant improvements in utilization and quality, but we found no evidence that it led to a reduction in preventable complications that are implicated in maternal deaths. ■

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (Grant No. R01HD083444; principal investigator: Edward Okeke). The funder had no role in the study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation, or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all of the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. This study could not have been carried out without the help and support of many people. A. V. Chari and Peter Glick were collaborators during the early stages of this work and provided many helpful comments and discussions. Christie Akwaowo, Usman Bashir, Nnenna Ihebuzor, and Obinna Onwujekwe helped facilitate implementation in Nigeria. Susan Lovejoy, Onyinye Stephen-Gow, and Laura Pavlock-Albright provided project support. Juliana Chen, Crystal Huang, Stephen Okpalaononuju, Adeyemi Okunogbe, and Victor Olajide provided research assistance. Bamidele Aderibigbe, Saidu Abubakar, Sadia Aliyu, Sadiya Awala, Yakubu Suleiman, and Edidiong Umoh led the fieldwork. Lastly, the authors are grateful to all of the study participants, who gave generously of their time. Helpful comments on an earlier draft were provided by Margaret Kruk.

Contributor Information

Edward N. Okeke, Department of Economics, Sociology, and Statistics, RAND Corporation, in Arlington, Virginia, and a professor of policy analysis in the Pardee RAND Graduate School, in Santa Monica, California..

Zachary Wagner, Department of Economics, Sociology, and Statistics, RAND Corporation, in Santa Monica, California..

Isa S. Abubakar, Bayero University and Aminu Kano Teaching Hospital, both in Kano, Nigeria..

NOTES

- 1.Alkema L, Chou D, Hogan D, Zhang S, Moller AB, Gemmill A, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in maternal mortality between 1990 and 2015, with scenario-based projections to 2030: a systematic analysis by the UN Maternal Mortality Estimation Inter-Agency Group. Lancet. 2016; 387(10017):462–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank. Trends in maternal mortality: 1990 to 2015: estimates by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA, World Bank Group and the United Nations Population Division [Internet]. Geneva: World Health Organization; c 2015. [cited 2020 Mar 30]. Available from: https://www.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/9789241565141_eng.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 3.Say L, Chou D, Gemmill A, Tunçalp Ö, Moller AB, Daniels J, et al. Global causes of maternal death: a WHO systematic analysis. Lancet Glob Health. 2014;2(6):e323–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhutta ZA, Das JK, Bahl R, Lawn JE, Salam RA, Paul VK, et al. Can available interventions end preventable deaths in mothers, newborn babies, and stillbirths, and at what cost? Lancet. 2014;384(9940):347–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hunter BM, Harrison S, Portela A, Bick D. The effects of cash transfers and vouchers on the use and quality of maternity care services: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2017; 12(3):e0173068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Murray SF, Hunter BM, Bisht R, Ensor T, Bick D. Effects of demand-side financing on utilisation, experiences, and outcomes of maternity care in low- and middle-income countries: a systematic review. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014; 14(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kruk ME, Gage AD, Arsenault C, Jordan K, Leslie HH, Roder-DeWan S, et al. High-quality health systems in the Sustainable Development Goals era: time for a revolution. Lancet Glob Health. 2018;6(11): e1196–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Titaley CR, Hunter CL, Dibley MJ, Heywood P. Why do some women still prefer traditional birth attendants and home delivery?: A qualitative study on delivery care services in West Java Province, Indonesia. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2010; 10(1):43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chaturvedi S, Upadhyay S, De Costa A. Competence of birth attendants at providing emergency obstetric care under India’s JSY conditional cash transfer program for institutional delivery: an assessment using case vignettes in Madhya Pradesh province. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2014;14(1):174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lim SS, Dandona L, Hoisington JA, James SL, Hogan MC, Gakidou E. India’s Janani Suraksha Yojana, a conditional cash transfer programme to increase births in health facilities: an impact evaluation. Lancet. 2010;375(9730):2009–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Randive B, Diwan V, De Costa A. India’s conditional cash transfer programme (the JSY) to promote institutional birth: is there an association between institutional birth proportion and maternal mortality? PLoS One. 2013;8(6):e67452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dettrick Z, Firth S, Jimenez Soto E. Do strategies to improve quality of maternal and child health care in lower and middle income countries lead to improved outcomes? A review of the evidence. PLoS One. 2013; 8(12):e83070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gabrysch S, Civitelli G, Edmond KM, Mathai M, Ali M, Bhutta ZA, et al. New signal functions to measure the ability of health facilities to provide routine and emergency newborn care. PLoS Med. 2012;9(11): e1001340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Save the Children. State of the world’s mothers 2014: saving mothers and children in humanitarian crises [Internet]. Westport (CT): Save the Children; c 2014. [cited 2020 Mar 30]. Available from: https://www.savethechildren.org/content/dam/usa/reports/advocacy/sowm/sowm-2014.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nigeria National Population Commission. Nigeria: demographic and health survey 2018 [Internet]. Rockville (MD): ICF Inc.; 2019October [cited 2020 Mar 30]. Available from: https://www.dhsprogram.com/pubs/pdf/FR359/FR359.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 16.Census areas are clusters of contiguously located households defined by the National Population Commission.

- 17.Nigerian National Bureau of Statistics. LSMS-Integrated Surveys on Agriculture: General Household Survey Panel, 2015/2016 [Internet]. Washington (DC):World Bank; 2016. [cited 2020 May 4]. Available from: https://africacheck.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/GHS_Panel_Survey_Report_W3_2015_16_Revised-2.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ware J Jr, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: construction of scales and preliminary tests of reliability and validity. Med Care. 1996;34(3):220–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. How to score the SF-12 physical and mental health summary scales. 3rd ed. Lincoln (RI): Quality Metric Inc.; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 20.To access the appendix, click on the Details tab of the article online.

- 21.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Crossing the global quality chasm: improving health care worldwide. Washington (DC): National Academies Press; 2018. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Begley CM, Gyte GM, Devane D, McGuire W, Weeks A. Active versus expectant management for women in the third stage of labour. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015; (3):CD007412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gülmezoglu AM, Lumbiganon P, Landoulsi S, Widmer M, Abdel-Aleem H, Festin M, et al. Active management of the third stage of labour with and without controlled cord traction: a randomised, controlled, non-inferiority trial. Lancet. 2012;379(9827):1721–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization. WHO recommendations for prevention and treatment of maternal peripartum infections [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; c 2015. [cited 2020 Mar 31]. Available from: https://www.google.com/books/edition/WHO_Recommendations_for_Prevention_and_T/bls0DgAAQBAJ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bruhn M, McKenzie D. In pursuit of balance: randomization in practice in development field experiments. Am Econ J Appl Econ. 2009;1(4): 200–32. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Greene W. The behaviour of the maximum likelihood estimator of limited dependent variable models in the presence of fixed effects. Econom J. 2004;7(1):98–119. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Using more complex multilevel models (estimated using maximum likelihood) that took into account the nesting structure of the data produced similar results.

- 28.Anderson ML. Multiple inference and gender differences in the effects of early intervention: a reevaluation of the Abecedarian, Perry Preschool, and Early Training Projects. J Am Stat Assoc. 2008;103(484):1481–95. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen J, Rothschild C, Golub G, Omondi GN, Kruk ME, McConnell M. Measuring the impact of cash transfers and behavioral “nudges” on maternity care in Nairobi, Kenya. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(11): 1956–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Peet ED, Okeke EN. Utilization and quality: how the quality of care influences demand for obstetric care in Nigeria. PLoS One. 2019;14(2): e0211500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization. Making pregnancy safer: the critical role of the skilled attendant: a joint statement by WHO, ICM and FIGO [Internet]. Geneva: WHO; 2004. [cited 2020 Mar 31]. Available from: https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/42955/9241591692.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 32.Elsewhere we found that the intervention led to economically meaningful improvements in child survival. Okeke EN, Abubakar IS. Healthcare at the beginning of life and child survival: evidence from a cash transfer experiment in Nigeria. J Dev Econ. 2020;143:102426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okeke EN, Chari A. Home and dry? Bad weather, place of birth, and birth outcomes. Santa Monica (CA): RAND Corporation; 2016. (Working Paper). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Thaddeus S, Maine D. Too far to walk: maternal mortality in context. Soc Sci Med. 1994;38(8):1091–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Okeke EN. Working hard or hardly working: Health worker effort and health outcomes. Economic Development and Cultural Change [serial on the Internet]. 2019October10 [cited 2020 Mar 25]. Available from: 10.1086/706823 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Das J, Hammer J. Quality of primary care in low-income countries: facts and economics. Annu Rev Econom. 2014;6:525–53. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.