Abstract

The spread of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) infection across the world accelerated the adoption of social media as the platform of choice for real-time dissemination of medical information. Though this allowed useful clinical anecdotes and links to the latest articles related to COVID-19 to quickly circulate, the broad use of social media also highlighted the power of platforms such as Twitter to spread misinformation. Trainees in medicine have important perspectives to share on social media but may be reluctant to do so for a variety of reasons. There is a need to provide guidance on how to safely engage with social media as well as move the conversation forward in a meaningful way. In this manuscript, we suggest a stepwise approach for trainee social media engagement that integrates the modified Bloom’s Taxonomy for social media with Aristotle’s principles of rhetoric. This provides trainees with guidance on making ethical, logical, and persuasive cases on social media when creating, consuming, promoting, and discussing content produced by themselves or others.

Keywords: social media, trainees, medical education

The global pandemic caused by the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) has accelerated the rapid change of the health care–social media landscape. Over 3.6 billion people worldwide use social media (1), making it a natural home for both health information and misinformation to circulate widely and rapidly. As our understanding of COVID-19 evolved, social media served as a valuable tool for amplifying the latest developments. As recommendations changed frequently, clinicians, scientists, and organizations took to social media to broadcast their views. However, early data were frequently incomplete, inaccurate, and later revised or rejected (2, 3).

Within the field of pulmonary and critical care medicine, some clinicians rapidly became regarded as experts in this novel coronavirus—some recognized as such by the wider community, while others were self-appointed. Throughout the world, as clinicians battled COVID-19, uncontrolled observations of patients’ physiology or ventilator management strategies quickly became lore and were rapidly disseminated on Twitter before the rigors of peer review had set in. Moreover, because the time-cycle of social media is so brief, even experts whose “hot takes” had quickly gone viral rarely returned to their prior content with corrections, thus unintentionally perpetuating inaccurate information. As responsible stewards of science communication, trainees need to be familiar with best practices to safely and appropriately navigate social media, both in consuming content and posting their own.

The Unique Perspective of Trainees

The fast pace of clinical observations and publication has irrevocably changed clinical training and medical education. Because trainees are deeply embedded in the trenches of daily patient care and are comfortable with social media platforms, having grown up with them, they have an incredibly valuable perspective to contribute to digital conversations.

Because trainees have grown up as “digital natives” who view social media as an important and intrinsic part of society (4), one might assume that trainees are comfortable engaging with social media in a dynamic clinical context. However, students, residents, and fellows may feel reticent, or even discouraged, about sharing their views, especially if they are sharing ideas on areas outside of their expertise or because of feelings of “impostor syndrome” (5). In addition to worries about “impostor syndrome,” some may also feel pressure to “go viral” by accruing likes or followers by making bold or even inflammatory statements in posts. Contributing authentically to the digital conversation, without falling for the common social media “traps,” can be challenging.

Like all social media users, trainees should be very careful about biases and blind spots. The Dunning-Kruger effect (6) is a cognitive bias in which people wrongly overestimate their own knowledge or ability in a specific area. There is not always a linear correlation between confidence and competence, and learners may have blind spots of their own knowledge gaps. This effect can be magnified on social media, where a lack of knowledge combined with a strongly expressed opinion can be a recipe for a bad tweet going viral. This applies to all social media users and is not limited to trainees. For example, Tesla CEO Elon Musk’s tweet that “ICUs [intensive care units] were jumping the gun on intubation and setting PEEP [positive end-expiratory pressure] and O2 too high” (7) was rightfully criticized by the medical community (8).

Trainees who might be reluctant to engage in social media should recognize that, as some of the most “viral” yet inaccurate expert opinions have demonstrated, experience does not always mean that experts’ words should be believed uncritically. In fact, research shows that novices often have more competence and skill than they perceive (9).

We believe that trainee voices are unique, valid, and important and that instead of being reluctant to engage in social media around medical topics, trainees actually have unique expertise that can inform debates. This Perspective describes best practices for trainees to appropriately and effectively navigate social media while gaining the confidence to make their voices heard.

Trainee Engagement with Social Media: A Modified “Bloom’s Taxonomy” Pyramid

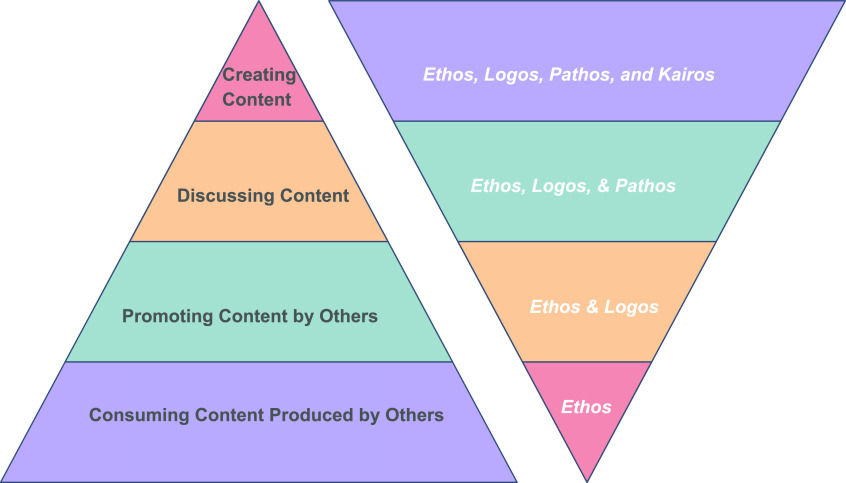

“Bloom’s Taxonomy” is a well-known framework in the medical education literature describing educational objectives and how to link these objectives to assessment (10). Lower levels on the pyramid represent objectives such as merely knowing a fact, whereas higher level objectives ask learners to apply their knowledge or perform a simulated task. Bloom’s Taxonomy is a helpful framework with which many medical educators are familiar, and a modified Bloom’s Taxonomy depicting how trainees can constructively engage with social media has been proposed (11).

In addition to using this modified Bloom’s Taxonomy, we recognize the critical role that persuasion plays in social media discourse of the medical community. Therefore, we propose that to persuasively and effectively communicate on social media, one should integrate Aristotle’s lessons of rhetoric to science communication (12): the use of ethos, logos, pathos, and the lesser-known kairos. Ethos refers to appealing to ethics, that is, conveying to the readership that the author has credibility and expertise. It can be helpful to frame arguments by indicating how you have expertise in this area. Logos refers to appealing to logic, that is, conveying to the readership that the argument is rooted in logic, science, and structure. Systematically and deliberately laying out a case in your social media appeal, and backing it up with pertinent citations, is critical. Pathos refers to the appeal to the reader’s passions. Though clinicians are often reluctant to share their emotions about clinical situations, pathos is useful in making an effective argument. We will outline ways to do so without compromising patient confidentiality. Lastly, the lesser-known kairos refers to the appeal of timeliness and knowing the opportune time to bring forward a persuasive social media discussion.

These two frameworks may be used systematically to explore the different stages of social media engagement to provide guidance for trainees navigating the social media landscape safely and appropriately (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

An approach to effective social media engagement by integrating modified Bloom’s Taxonomy with Aristotle’s principles of rhetoric. Modified Bloom’s taxonomy for social media is shown in the left triangle adjacent to Aristotle’s Principles of Rhetoric in the adjacent inverted triangle. As a trainee engages in higher levels of the modified Bloom’s taxonomy, it is important to incorporate more principles of rhetoric to effectively engage on social media.

Consuming and Promoting Social Media Content: Consider the Ethos and Logos

Novice users begin to get involved in social media by reading what others are posting. However, consumers of social media need to be aware of biases and misinformation. The most popular “viral” posts may not have the most balanced or accurate information (13). Trainees must be cautious, even while consuming content on social media. Consider the ethos, the source, or author of the content: Who has written the article? What are their credentials and experiences that lend them expertise in this area? What are their possible biases? What explicit agenda or hidden curriculum could they be promoting? Do they have any conflicts of interest, either disclosed or undisclosed? Can this information be corroborated elsewhere, or is it just one voice? Is the information presented as fact or opinion? Even when prominent authoritative voices in the field post medical information, these factors should be considered.

Trainees often use social media to promote, celebrate, and disseminate their own scholarly work or that of their peers (14). Similarly, trainees may amplify posts with which they agree. When promoting social media content, the same considerations should be applied: just as when consuming content, trainees should be wary of misinformation and disinformation and consider authorship, expertise, biases, and blind spots. Trainees should apply a critical eye to ensure that arguments that they are amplifying are rooted in evidence (logos) and not merely amplifying experts for the sake of being considered as “experts.”

When posting on social media, trainees should consider who they represent, that is, does this viewpoint represent the trainee, their institution/program, or even their profession? Though many individuals use disclaimers such as “Tweets my own” to indicate that they are speaking only for themselves and not their institution, inflammatory posts can lead to significant implications beyond the individual.

Trainees should consider diversity—or lack thereof—of voices being amplified. When not thoughtfully curated, social media feeds can sometimes become an “echo chamber” of voices that lack diversity of thought, sex, race/ethnicity, and ability (15). Websites that provide sex breakdowns of social media followers (16) are accessible, and opting to see the latest tweets rather than those chosen by an algorithm can help improve the diversity of voices in your timeline.

Discussing Social Media Content: Remember Logos and Beware of Pathos

An exciting aspect of social media and medical Twitter is the real-time vigorous debate of ideas, physiologic principles, new clinical trials, and other important research papers. The “court of social media” has become an important platform for discussion in the modern era of publishing, in which it is common for authors to share their preprints on online servers before the journal peer-review process is complete. Though this can lead to prompt vetting of medical misinformation, unfortunately, it can also lead to erroneous dissemination of information before the facts are clear. Because science is an iterative process, when discussing new science on social media, be willing to revise opinions and recommendations as new data emerges. When discussing evolving recommendations, it is particularly helpful to share links to the original research whenever possible and explain the reasoning as to why recommendations have changed. Though posting screenshots of “old takes” sharing misinformation seems to be a popular “gotcha” mechanism, we caution against this because science is a process in which information changes rapidly, and clinicians need to communicate this respectfully, rapidly, and in a trustworthy fashion. For example, criticizing early anecdotes on how acute respiratory distress syndrome owing to COVID-19 is different from other causes or posting links several months later to old social media warnings early in the pandemic asking people to save masks for healthcare workers, is not helpful in moving the medical conversation forward.

Finally, trainees should remember the “New York Times” rule of ethical conduct, which, when applied to social media, argues that when posting content in a professional capacity, do not post something that you would not want to be reported on the front page of a newspaper. In general, this refers to content that might be perceived as unprofessional, such as comments about patients or families or comments about other specialties. However, this sentiment should not dissuade trainees from using their voices to advocate for issues important to them in an informed and evidence-based way. For example, healthcare providers can persuasively advocate for candidates for political office or policies that improve health care for patients.

Putting it All Together: Ethos, Logos, Pathos, and Kairos to Create Social Media Content

When creating your own content, consider appealing to all aspects of Aristotle’s principles of rhetoric, including considering the author, the audience, the emotion, the argument, and the timeliness of the argument. Arguments should be clear and persuasive, and anecdotes paired with data can often be particularly effective. Posts with images and links to primary literature sometimes linked in threads are best practices for sharing information (17). Trainees should also consider their own unique perspectives reflected by their own experiences and expertise, as well as their own biases and blind spots, when creating social media content.

Posts about patients should always be avoided, and care should be taken to avoid any identifying information in social media posts and to consider the broader implications of a post. Healthcare social media experts such as Dr. A. O. Glasser have noted to “post the pearl, not the patient” to disseminate teaching points while avoiding identifying patients inadvertently (18). Even posts expressing pride or joy about a new invasive procedure performed (e.g., “Used a Bougie like a pro today!”) can come across as insensitive to patients and families and may also run afoul of privacy and ethics rules, as dates can cause the information to be identifiable and traced. Patients and family members follow physicians on social media, so one must balance the timeliness of a post with patient privacy considerations. One practical way to do this is to wait for a few weeks before posting anonymized anecdotes or “pearls.” For example, posting a “pearl” about endocarditis may seem innocent enough, but for the patient’s family member who recognizes the physician as part of the care team, it can feel like an invasion of privacy. To counteract this, it makes sense to wait a few weeks before posting anything remotely identifiable and traceable to a specific patient. When posting sensitive information about one’s institutional policies or leadership, be sensitive to the impact of your tweet on your institution. Finally, if social media discussions become contentious, an important tip is to avoid responding to inflammatory posts or continuing to engage in unproductive conversations.

Table 1 provides a summary with examples of tips and traps to review these principles. Although this list is not comprehensive, the advice is based on our personal experiences navigating social media, and many are based on lessons learned the hard way. At the same time, we acknowledge our bias as faculty at academic medical centers and appreciate that these general tips do not address particular challenges that women and underrepresented-in-medicine trainees may face when engaging in social media (19).

Table 1.

Practical examples summarizing traps to avoid and tips to navigate social media

| Bloom’s | Aristotle | Avoid This Trap | Try This Tip |

|---|---|---|---|

| Consuming content produced by others | Ethos | Reading a press release for a new therapeutic without noting the conflict of interest of the sponsoring pharmaceutical company | Reading a social media post by a clinician and searching for prior writings on this topic by the same author to consider their authority and expertise |

| Promoting content by others | Ethos and Logos | Sharing or disseminating an article or opinion without having read the article or considered the author | Critically examining the voices followed by using proportional or other tools and strategically amplifying authoritative and diverse voices |

| Discussing content | Ethos, Logos, and Pathos | Passionately sharing a patient anecdote to prove a point in a discussion | Pairing deidentified anecdotes with evidence to more persuasively argue a point |

| Creating content | Ethos, Logos, Pathos, and Kairos | Posting about a procedure done today or an interesting patient case witnessed recently in a way that could be identifiable | Constructing a thoughtful teaching thread about the steps involved in doing a procedure, rooted in evidence |

Conclusions

Navigating the fast-paced world of social media need not be treacherous, though trainees should tread carefully to consume, promote, discuss, and create social media content. By remembering Aristotle’s original concepts of rhetoric and persuasion, trainees can thoughtfully and effectively engage in social media by considering the source of information, constructing logical arguments, appealing to emotion, and keeping discussion timely and relevant. We hope that this Perspective demystifies the process and shows trainees that engaging in social media, even in the time of coronavirus, can be educational, impactful, and even joyful.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported, in part, by the National Institutes of Health Clinical Center.

Author disclosuresare available with the text of this article atwww.atsjournals.org.

REFERENCES

- 1.Clement JStatista Number of global social media users 2010–2021 New York, NY: Statista Inc.2020[accessed 2020 Mar 16]. Available from: https://www.statista.com/statistics/278414/number-of-worldwide-social-network-users/ [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bramstedt KA. The carnage of substandard research during the COVID-19 pandemic: a call for quality. J Med Ethics. 2020;46:803–807. doi: 10.1136/medethics-2020-106494. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ledford H, Van Noorden R.High-profile coronavirus retractions raise concerns about data oversight New York, NY: Nature Research; 2020[accessed 2021 Feb 10] Available from: https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586–020–01695-w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prensky M.H. sapiens digital: From digital immigrants and digital natives to digital wisdom Innovate Journal of Online Education 20095Available at: https://nsuworks.nova.edu/innovate/vol5/iss3/1. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Legassie J, Zibrowski EM, Goldszmidt MA. Measuring resident well-being: impostorism and burnout syndrome in residency. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1090–1094. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0536-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Kruger J, Dunning D. Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1999;77:1121–1134. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.77.6.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.@elonmusk. Tesla actually sent out ResMed, Philips & Medtronic units. Latter is fully intratracheal. My personal opinion is that some ICUs are jumping the gun on intubation & setting PEEP & O2 too high. High pressure, pure oxygen increases risk of lung damage [posted 2020 April 15]. Available fromhttps://twitter.com/elonmusk/status/1250602314609520641?s=20

- 8. Burson KA, Larrick RP, Klayman J. Skilled or unskilled, but still unaware of it: how perceptions of difficulty drive miscalibration in relative comparisons. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2006;90:60–77. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.90.1.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bloom BS, Krathwohl DR. Taxonomy of educational objectives: the classification of educational goals. New York: Longman; 1956. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bloom BS.editor. Taxonomy of educational objectives; handbook I: cognitive domain New York: David McKay Co Inc.1956 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jaffe RC, O’Glasser AY, Brooks M, Chapman M, Breu AC, Wray CM. Your@ attending will# tweet you now: using twitter in medical education. Intern Med. 2015;30:1673–1680. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000003314. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Varpio L. Using rhetorical appeals to credibility, logic, and emotions to increase your persuasiveness. Perspect Med Educ. 2018;7:207–210. doi: 10.1007/s40037-018-0420-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Depoux A, Martin S, Karafillakis E, Preet R, Wilder-Smith A, Larson H. The pandemic of social media panic travels faster than the COVID-19 outbreak. J Travel Med. 2020;27:taaa031. doi: 10.1093/jtm/taaa031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Klar S, Krupnikov Y, Ryan JB, Searles K, Shmargad Y. Using social media to promote academic research: identifying the benefits of twitter for sharing academic work. PLoS One. 2020;15:e0229446. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0229446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Campos-Castillo C, Laestadius LI. Racial and ethnic digital divides in posting COVID-19 content on social media among US adults: secondary survey analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e20472. doi: 10.2196/20472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Davis AJJProporti.onl Estimate the gender distribution of your followers and those you follow based on their profile descriptions or first names[accessed 2021 Feb 10]. Available from: https://www.proporti.onl/

- 17.Rogers S.What fuels a Tweet’s engagement? San Francisco, CA: Twitter Inc; 2014[accessed 2021 Feb 10]. Available from: https://blog.twitter.com/en_us/a/2014/what-fuels-a-tweets-engagement.html [Google Scholar]

- 18.@aoglasser. A Friday #tweetorial #medthread about patient privacy on #medtwitter #SoMe. There are many facets of patient privacy & professionalism concerns in this communal space—I’m going to focus on this through the lens of case-based teaching. 1/N [posted 2020 March 6]. Available from: https://twitter.com/aoglasser/status/1236054137420173312?s=21

- 19. Stamp N, Mitchell R, Fleming S. Social media and professionalism among surgeons: who decides what’s right and what’s wrong? J Vasc Surg. 2020;72:1824–1826. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2020.07.076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.