Abstract

Background: Social media is ubiquitous as a tool for collaboration, networking, and dissemination. However, little is known about use of social media platforms by pulmonary and critical care medicine fellowship programs.

Objective: We identify and characterize pulmonary and critical care fellowship programs using Twitter and Instagram, as well as the posting behaviors of their social media accounts.

Methods: We identified all adult and pediatric pulmonary, critical care medicine (CCM), and combined pulmonary and critical care medicine (PCCM) programs in the United States using the Electronic Residency Application Service. We searched for Twitter profiles for each program between January 1, 2018, and September 30, 2018. Tweets and Twitter interactions were classified into the following three types: social, clinical, or medical education (MedEd) related. We collected data about content enhancements of tweets, including the use of pictures, graphics interchange format or videos, hashtags, links, and tagging other accounts. The types of tweets, content enhancement characteristics, and measures of engagement were analyzed for association with number of followers.

Results: We assessed 341 programs, including 163 PCCM, 36 adult CCM, 20 adult pulmonary, 67 pediatric CCM, and 55 pediatric pulmonary programs. Thirty-three (10%) programs had Twitter accounts. Of 1,903 tweets by 33 of the 341 programs with Twitter accounts, 476 (25%) were MedEd related, 733 (39%) were clinical, and 694 (36%) were social. The median rate of tweets per month was 1.65 (interquartile range [IQR], 0.4–6.65), with 55% programs tweeting more than monthly. Accounts tweeting more often had significantly more followers than those tweeting less frequently (median, 240 followers; 25–75% IQR, 164–388 vs. median, 107 followers; 25–75% IQR, 13–188; P = 0.006). Higher engagement with clinical and social Twitter interactions (tweets, retweets, likes, and comments) was associated with more followers but not for the MedEd-related Twitter interactions. All types of content enhancements (pictures, graphics interchange format/videos, links, and tagging) were associated with a higher number of followers, except for hashtags.

Conclusion: Despite the steadily increasing use of social media in medicine, only 10% of the pulmonary and critical care fellowship programs in the United States have Twitter accounts. Social and clinical content appears to gain traction online; however, additional evaluation is needed on how to effectively engage audiences with MedEd content.

Keywords: graduate medical education, medical education, social media, Twitter

Social media is increasingly recognized and used as a tool to create collaborations and disseminate information for medical education. In medicine, social media use has been shown to facilitate communication as well as improve knowledge and skills, especially in educational settings (1–4). These fast-paced interactions allow for rapid dissemination of traditionally published literature and digital scholarship, which can aid in career advancement (5, 6). Social media use creates opportunities for learner engagement, garnering feedback, and community development and leads to increased collaboration and professional development (4, 7–10).

Training programs have embraced these trends, and social media has been integrated into curricula across a number of specialties and disciplines (11–14). Social media has been used by programs to engage their learners and to attract applicants (13, 15). Since the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic and the impact it has had on education, especially in terms of limitations placed on in-person interviewing, social media has gained importance for both programs and aspiring trainees to connect meaningfully (16).

However, there is no literature available about the use of social media platforms by pulmonary and critical care medicine fellowship programs. We sought to identify and define characteristics of programs using Twitter, one of the most commonly used social media platforms by medical professionals (17, 18). Twitter, a social media platform, stands out for succinct posting because of its limitation on the number of characters per tweet (280 characters), optimization for use on hand-held devices, and support of sharing of information in various formats, including text, figures, images. and videos (19). A unique aspect of Twitter as a platform is the ability for users to engage with accounts that may not necessarily follow them back, removing the social pressure of “friending” someone to access their content.

We studied the posting behaviors of the social media accounts of these pulmonary and/or critical care medicine (CCM) fellowship programs. Using the data from this study and other literature in the field of medicine, we also provide a stepwise guide for educators and trainees interested in establishing and operating successful accounts for their fellowship programs.

Methods

We identified all adult and pediatric pulmonary, critical care, and combined pulmonary and critical care (PCCM) programs in the United States using the Electronic Residency Application Service between January 1, 2018, and September 30, 2018. We searched for Twitter profiles for each program, using variations of the program and hospital names. We specifically sought to identify accounts belonging to a fellowship; however, when only a division account was available, it was included in the study. Available accounts were assessed for authorship information as well as verification status.

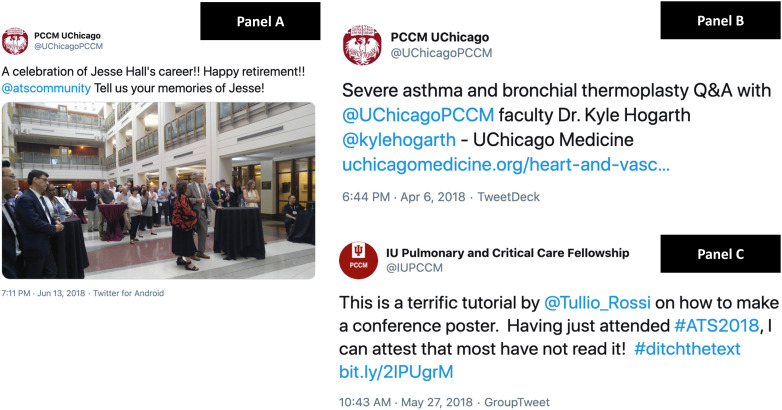

We evaluated the Twitter interactions (tweets, retweets, comments, and likes) from all available program accounts that were using Twitter between January 1, 2018, and September 30, 2018. Tweets and Twitter interactions were classified into three types on the basis of their content: social, clinical, or MedEd related. Social tweets were defined as those that focused on nonclinical social activities or interactions (Figure 1A). Clinical tweets were those pertaining to patient care or the practice of medicine (Figure 1B), as opposed to MedEd-related tweets, which were defined as those pertaining specifically to the field of education in medicine (Figure 1C). We collected data about content enhancements of tweets, including the use of pictures, graphics interchange format (GIF) or videos, hashtags, links, and tagging other accounts. Numbers of followers and following for Twitter were collected on October 5, 2018. The types of tweets, content enhancement characteristics, and measures of engagement were then analyzed for association with the number of followers.

Figure 1.

Demonstrative examples of a social tweet (A), clinical tweet (B), medical education tweet (C).

Data were analyzed using JMP statistical software (version 10.0.1; SAS Institute Inc.). Descriptive and comparative statistics were performed. Data are reported as medians with 25–75% interquartile range (IQR) or as frequencies (percentage). A Shapiro-Wilk test was used to assess normality, and nonparametric statistics were performed as appropriate. Comparisons were made using χ2, correlation coefficients, and Wilcoxon rank sum tests. A P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Because of the public nature of this research data, institutional review board approval was waived.

Results

We assessed 341 programs, including 163 PCCM, 36 adult CCM, 20 adult pulmonary, 67 pediatric CCM, and 55 pediatric pulmonary programs. Thirty-three (10%) programs had accounts on Twitter. There were no differences in the odds of having a Twitter account for any of the types of fellowship program (P = 0.052); 13% of the PCCM programs had Twitter accounts (21/163), 3% of the CCM programs had Twitter accounts (1/36), 13% of pediatric CCM programs had Twitter accounts (9/67), and 4% of pediatric pulmonary programs had Twitter accounts (2/55). No adult pulmonary fellowship programs had a Twitter account. Of 21 adult PCCM accounts, one adult CCM account, 10 pediatric CCM accounts, and two pediatric pulmonary accounts, 13, zero, six, and zero accounts, respectively, were dedicated fellowship accounts.

Programs with a Twitter account were larger in terms of number of faculty (median, 27 vs. 15; P = 0.0003) and fellows (median, 14 vs. 9; P < 0.0001). University fellowship programs were more likely than community-based fellowship programs to have a Twitter account (77% vs. 23%; odds ratio, 5.1; P = 0.01). None of the accounts were verified; 64% included a website, and only 9% identified an author responsible for managing the account. The median number of followers was 170 (IQR, 92.5–344), and the median number of accounts the programs were following was 97 (IQR, 55.5–198.5). Fellowship programs had been on Twitter for a median of 21 months (IQR, 9–32 mo). Time on Twitter was not related to the number of followers (R2 = 0.01; P = 0.59). The number of accounts the programs were following was related to the number of followers (R2 = 0.54, P < 0.0001). PCCM accounts had fewer followers than other accounts (median, 146 vs. 372; P = 0.002), and pediatric CCM accounts had more followers than other accounts (median, 377 vs. 145; P = 0.001).

A total of 1,903 tweets were published by the 33 programs that had Twitter accounts. Of these, 733 (39%) were clinical, 694 (36%) were social, and 476 (25%) were MedEd-related tweets. The types of tweets published by each type of fellowship are shown in Table 1. The median rate of tweets per month was 1.65 (IQR, 0.4–6.65), with 55% programs tweeting more than once per month. Accounts that tweeted more than once a month had significantly more followers than those that did not (median, 240 [25–75% IQR, 164–388] followers vs. median, 107 [25–75% IQR, 13–188] followers; P = 0.006). The number of tweets and the number of users followed were also associated with a higher number of followers (R2 = 0.54; P < 0.0001 and R2 = 0.20; P = 0.008, respectively).

Table 1.

Types of tweets from each type of fellowship

| Type of Account | MedEd Tweets [Median (IQR)] | Clinical Tweets [Median (IQR)] | Social Tweets [Median (IQR)] |

|---|---|---|---|

| Adult PCCM | 6 (0–25) | 0 (0–1) | 18 (3.5–18) |

| Adult CCM | 3 (3–3) | 25 (25–25) | 21 (21–21) |

| Pediatric CCM | 12 (3.5–24) | 6 (1–11) | 15 (4–61) |

| Pediatric pulmonary | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) | 0 (0–0) |

Definition of abbreviations: CCM = critical care medicine; IQR = interquartile range; MedEd = medical education; PCCM = pulmonary and critical care medicine.

Measures of content engagement (e.g., tweets, retweets, and likes of comments) for different types of content matter were also assessed (Table 2). Social tweets had higher numbers of likes and retweets than MedEd-related and clinical tweets. Furthermore, clinical and social Twitter interactions such as tweets (R = 0.44; P = 0.01 and R = 0.41, P = 0.02), retweets (R = 0.51; P = 0.002 and R = 0.44; P = 0.01), likes (R = 0.50; P = 0.003 and R = 0.48; P = 0.005), and comments (R = 0.44; P = 0.01 and R = 0.14, P = 0.02) correlate with higher number of followers. However, there is no correlation between MedEd-related Twitter interactions and number of followers. Accounts that used content enhancements such as pictures, GIFs, videos, links, and tags of other users also had higher numbers of followers. This correlation was not seen with the use of hashtags.

Table 2.

Engagement based on types of content as well as use of content enhancements

| Tweets [Median (IQR)] | Retweets [Median (IQR)] | Likes [Median (IQR)] | Comments [Median (IQR)] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Type of content | ||||

| Total | 39 (7.5–81.5) | 52 (4.5–124.5) | 230 (43.5–462) | 4 (0.5–21.5) |

| MedEd | 4 (0–23.5) | 8 (0–32.5) | 23 (0–137.5) | 1 (0–6) |

| Clinical | 3 (0–16.5) | 2 (0–31) | 13 (0–97) | 0 (0–4.75) |

| Social | 17 (2–34) | 13 (1.5–43.5) | 82 (19–173) | 2 (0–5.75) |

| Content enhancements | ||||

| Pictures | 19.5 (2.25–35.5) | 37.5 (2–67) | 119.5 (19–226) | 2 (0–10) |

| GIF/video | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–1) | 0 (0–4.75) | 0 (0–0) |

| Hashtag | 20 (1.5–39) | 21 (0.5–92.5) | 75 (4–303) | 3 (0–13) |

| Links | 12 (1.5–27.5) | 20 (0.75–57.5) | 52 (5–154) | 1 (0–6) |

| Tags | 20 (2–47) | 34 (3–77) | 109 (20–251) | 2 (0–14) |

Definition of abbreviations: GIF = graphics interchange format; IQR = interquartile range; MedEd = medical education.

Discussion

Despite the steadily increasing use of social media in medicine, only 10% of the pulmonary and/or CCM fellowship programs in the United States have accounts on Twitter. Developing a social media presence may be an opportunity for programs to engage both their learners and potential candidates. Although there are a number of social media platforms (7), Twitter is the most commonly used microblogging site by medical professionals.

We found that university programs and those with a higher number of faculty and fellows are more likely to have social media accounts. The median age of accounts on Twitter was only 21 months, suggesting that programs are likely still in the learning phase of social media presence. Notably, no adult or pediatric pulmonary fellowship programs had a presence on Twitter at the time of our data collection. Adult PCCM fellowship programs predominantly posted social and MedEd-related tweets as opposed to adult CCM programs, which posted predominantly social and clinical content. Pediatric CCM programs, on the other hand, produced a mixture of social, clinical, and MedEd-focused content. Further investigation on the content strategy and the reasoning behind it would help gain further insight into the priorities and effectiveness of various programs.

Establishing best practices, content type, and engagement goals and developing a consistent message takes time. With continued online presence, we anticipate that the existing accounts will be able to streamline their presence. The pediatric CCM fellowship accounts have more followers than other fellowships. This is likely a reflection of the consistent posting from the pediatric CCM community focused around the #PedsICU hashtag (20).

Our findings also suggest that a regular posting frequency, as well as demonstrating increased engagement by following other accounts, may lead to a higher number of followers. Use of content enhancements (e.g., pictures, GIFs/videos, links, and tagging) was associated with a higher number of followers, except for the use of hashtags. The strategy of augmenting the written tweet with pictures, GIFs/videos, links, and tagging has been successfully employed by various healthcare entities when tweeting (21, 22). As such, we suggest programs consider using content enhancers to augment their tweets to gain higher traction on social media. Table 3 provides some tips for establishing a successful fellowship Twitter account.

Table 3.

Eight steps for creating and operating a successful fellowship Twitter account

| Steps | Actions |

|---|---|

| Establishing clear objectives |

|

| Assembling a team of contributors |

|

| Creating a Twitter account |

|

| Posting content |

|

| Fostering collaborative growth |

|

| Advertising the account and the program |

|

| Measuring metrics |

|

| Setting up a pipeline of contributors |

|

Definition of abbreviations: GIF = graphics interchange format; MedEd = medical education; PCCM = pulmonary and critical care medicine.

Perhaps the most interesting observation is that these various content enhancements, as well as the clinical and social tweets themselves, were associated with a higher number of followers, but the same was not noted for the MedEd-related tweets. This suggests that users may be more interested in the clinical and social aspects of Twitter than the MedEd aspect. Alternatively, we hypothesize that MedEd-oriented content may need to be constructed in a different manner, and this needs to be studied further. It is also possible that the community of educators on Twitter may still be gaining prominence, and, hence, the digital conversations may not include these relatively young training programs. Finally, MedEd as a term is used rather vaguely on social media and, as such, could be leading to limitations in educators banding around the specific hashtags (e.g., #MedEd). It could be helpful, in that case, if educators created and focused their conversations around a rather unique hashtag. Conversations on Twitter have been created and nurtured around various events (#COVID19 and various conferences), specialties (#PedsICU), and disease states (#LCSM and #Asthma), which has allowed for better engagement, curation, and promotion and of these digital interactions (7, 20–23).

Our study does have some limitations. First, it is possible that some programs may not have been captured by our search strategy if their account names were not reflective of the official program or hospital name in the Electronic Residency Application Service. Similarly, if program accounts were not searchable, they would not have appeared in this search strategy. We only included original tweets or retweets in which accounts made comments to the original tweets (quote retweets). There is more that goes into gaining audience engagement, such as strategic retweets (without comments), which we did not capture. We were only able to evaluate the publicly available content and were not able to interview or survey content posters for the various accounts. Such investigation will certainly be helpful in evaluating priorities for various programs for being on social media and basis for posting strategy and potentially evaluating the success of one strategy over another. The search strategy was not designed to evaluate the contribution to engagement with fellowship accounts that might be driven by faculty or trainees recognized as “influencers” on social media. Studies have shown that organizational accounts are likely to post messages more frequently than personal accounts, and furthermore, because organizations tend to have more followers, their content receives disproportionately more visibility. This would suggest that a fellowship account even in the presence of a well-recognized social media influencer as faculty or trainee can have a valuable impact; however, the inability of our data to evaluate this impact remains a limitation of the study (24). In addition, we recognize that with the rapid evolution of the social media landscape, educational modalities, availability of digital resources, and, most importantly, changing learner needs, as well as fellowship program priorities, significant shifts are likely to occur in digital conversations. Thus, timely introspection and regular evaluation of posting strategy is advised. This is reflected in the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, in which social media has played a key role in knowledge dissemination and scientific discourse. As stated earlier, social media is playing an important role during the pandemic. Our study was conceived and designed much before the pandemic, with data collection occurring in 2018. We recognize that these data do not capture the changes in Twitter use that may have occurred in the past year because of the limited travel, professional networking, and transition to virtual education formats. However, our findings and recommendations remain relevant to a medical education community that continues to grow its Twitter presence. Fellowship programs and institutions can optimize their use of social media, particularly Twitter, to augment virtual interviewing experiences. Although our analysis does not capture this shift in conversations occurring during the ongoing pandemic, further research is warranted to assess the impact on the presence and engagement of fellowship Twitter accounts (25).

In summary, we found that pulmonary and/or CCM programs have started using the power of social media to deliver social, clinical, and MedEd-related content. Although not many programs were present on Twitter during the period of the study, we believe this can be a valuable opportunity for a program to market themselves, celebrate their fellows, and create opportunities for collaboration. Social and clinical content appears to gain traction online. Further evaluation is needed on how best to engage audiences with MedEd-related content.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Author Contributions: All authors have read and approved the final submission of this manuscript. All authors contributed to study conception and design. S.G., N.H.S., D.K., P.G., and V.K. performed all of the data collection. C.L.C. performed the data analysis. S.G. and V.K. drafted the manuscript, and all authors performed critical revision.

Author disclosuresare available with the text of this article atwww.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Nickson CP, Cadogan MD. Education and training. Emerg Med Australas. 2014;26:76–83. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Davis WM, Ho K, Last J. Advancing social media in medical education. CMAJ. 2015;187:549–550. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.141417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hamm MP, Chisholm A, Shulhan J, Milne A, Scott SD, Klassen TP, et al. Social media use by health care professionals and trainees: a scoping review. Acad Med. 2013;88:1376–1383. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31829eb91c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cheston CC, Flickinger TE, Chisolm MS. Social media use in medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2013;88:893–901. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31828ffc23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Weingart SD, Faust JS. Future evolution of traditional journals and social media medical education. Emerg Med Australas. 2014;26:62–66. doi: 10.1111/1742-6723.12192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Cabrera D, Vartabedian BS, Spinner RJ, Jordan BL, Aase LA, Timimi FK. More than likes and tweets: creating social media portfolios for academic promotion and tenure. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9:421–425. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-17-00171.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnes SS, Kaul V, Kudchadkar S.Social media engagement and the critical care medicine community 2019[updated 2020 Jun 17]. Available from: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0885066618769599 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8. Chan T, Trueger NS, Roland D, Thoma B. Evidence-based medicine in the era of social media: scholarly engagement through participation and online interaction Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine Cambridge Core. Canadian Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2017;20:3–8. doi: 10.1017/cem.2016.407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Carroll CL, Bruno K, Ramachandran P. Building community through a #pulmcc twitter chat to advocate for pulmonary, critical care, and sleep. Chest. 2017;152:402–409. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2017.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Carroll CL, Dangayach NS, Khan R, Carlos WG, Harwayne-Gidansky I, Grewal HS, et al. Social Media Collaboration of Critical Care Practitioners and Researchers (SoMe-CCCPR) Lessons learned from web- and social media-based educational initiatives by pulmonary, critical care, and sleep societies. Chest. 2019;155:671–679. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Scott KR, Hsu CH, Johnson NJ, Mamtani M, Conlon LW, DeRoos FJ. Integration of social media in emergency medicine residency curriculum. Ann Emerg Med. 2014;64:396–404. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Bahner DP, Adkins E, Patel N, Donley C, Nagel R, Kman NE. How we use social media to supplement a novel curriculum in medical education. Med Teach. 2012;34:439–444. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.668245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Galiatsatos P, Porto-Carreiro F, Hayashi J, Zakaria S, Christmas C. The use of social media to supplement resident medical education - the SMART-ME initiative. Med Educ Online. 2016;21:29332. doi: 10.3402/meo.v21.29332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Merchant RM, Elmer S, Lurie N. Integrating social media into emergency-preparedness efforts. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:289–291. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1103591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Sterling M, Leung P, Wright D, Bishop TF. The use of social media in graduate medical education: a systematic review. Acad Med. 2017;92:1043–1056. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Nguyen JK, Shah N, Heitkamp DE, Gupta Y. COVID-19 and the radiology match: a residency program’s survival guide to the virtual interview season. Acad Radiol. 2020;27:1294–1297. doi: 10.1016/j.acra.2020.06.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Choo EK, Ranney ML, Chan TM, Trueger NS, Walsh AE, Tegtmeyer K, et al. Twitter as a tool for communication and knowledge exchange in academic medicine: a guide for skeptics and novices. Med Teach. 2015;37:411–416. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2014.993371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Topf JM, Hiremath S. Social media, medicine and the modern journal club. Int Rev Psychiatry. 2015;27:147–154. doi: 10.3109/09540261.2014.998991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Pershad Y, Hangge PT, Albadawi H, Oklu R. Social medicine: twitter in healthcare. J Clin Med. 2018;7:121. doi: 10.3390/jcm7060121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. McMenaman K, Carroll C, Kaul V, Kudchadkar S. 1053: little patients, bigger footprint: social media presence of critical care fellowship programs. Crit Care Med. 2020;48:506. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Kaul V, Boka K, Greenstein Y, Namendys-Silva S, Carroll C. Counting conversations on lung cancer: analyzing the footprint of various healthcare stakeholders on twitter. Chest. 2019;156:A1082. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Carroll C, Dangayach N, Kaul V, Sala K, Bruno K. Describing the digital health footprints or “sociomes” of asthma on twitter. Chest. 2019;156:A998. doi: 10.34197/ats-scholar.2019-0014OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Carroll CL, Szakmany T, Dangayach NS, DePriest A, Duprey MS, Kaul V, et al. Growth of the digital footprint of the Society of Critical Care Medicine Annual Congress: 2014–2020. Crit Care Explor. 2020;2:e0252. doi: 10.1097/CCE.0000000000000252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. McCorriston J, Jurgens D, Ruths D. Organizations are users too: characterizing and detecting the presence of organizations on Twitter. Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media 2015 [accessed 2020 Dec 1]. Available from: https://ojs.aaai.org/index.php/ICWSM/article/view/14672.

- 25. Chan AKM, Nickson CP, Rudolph JW, Lee A, Joynt GM. Social media for rapid knowledge dissemination: early experience from the COVID-19 pandemic. Anaesthesia. 2020;75:1579–1582. doi: 10.1111/anae.15057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Widmer RJ, Engler NB, Geske JB, Klarich KW, Timimi FK. An academic healthcare twitter account: the mayo clinic experience. Cyberpsychol Behav Soc Netw. 2016;19:360–366. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2015.0607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Wadhwa V, Latimer E, Chatterjee K, McCarty J, Fitzgerald RT. Maximizing the tweet engagement rate in academia: analysis of the AJNR twitter feed. AJNR Am J Neuroradiol. 2017;38:1866–1868. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A5283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.McLachlan S.12 of the best link shorteners that aren’t the google URL shortener 2020[updated 2020 Sep 7]. Available from: https://blog.hootsuite.com/what-are-url-shorteners/

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.