Abstract

Qualitative research methods are important and have become increasingly prominent in medical education and research. The reason is simple: many pressing questions in these fields require qualitative approaches to elicit nuanced insights and additional meaning beyond standard quantitative measurements in surveys or observatons. Among the most common qualitative data collection methods are structured or semistructured in-person interviews and focus groups, in which participants describe their experiences relevant to the research question at hand. In the era of physical and social distancing because of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic, little guidance exists for strategies for conducting focus groups or semistructured interviews. Here we describe our experience with, and recommendations for, conducting remote focus groups and/or interviews in the era of social distancing. Specifically, we discuss best practice recommendations for researchers using video teleconferencing programs to continue qualitative research during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Keywords: qualitative research, videoconferencing, social distancing

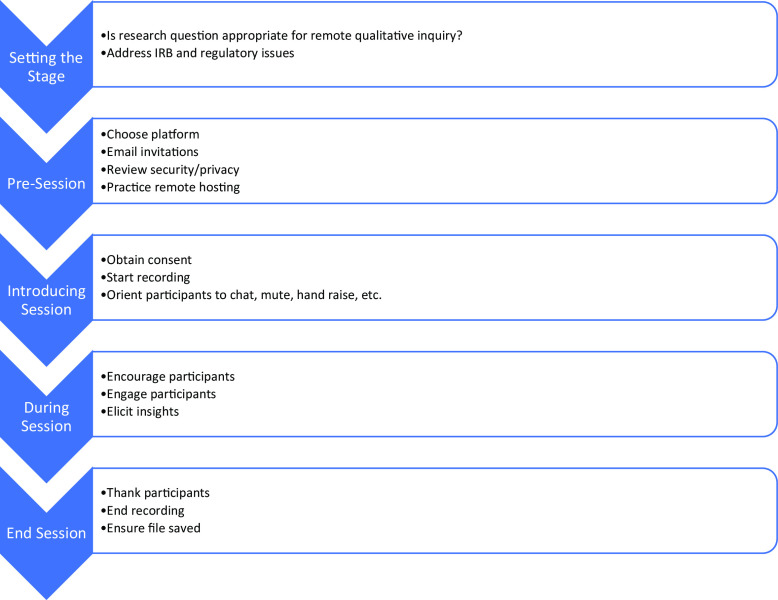

Qualitative research focuses on exploring individuals’ perspectives related to specific research questions, issues, or activities (1). Frequently, structured interviews or focus groups are tools employed for data collection for qualitative research. In-person interviews are ideal, although phone and digital alternatives may be considered (2, 3). However, little guidance exists for strategies for conducting focus groups or semistructured interviews in the era of physical and social distancing with the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) pandemic. In this article, we describe some strategies for conducting focus groups or structured interviews with the use of video conferencing platforms (Figure 1). Video conferencing may provide researchers and research participants with a convenient and safe alternative to in-person qualitative research, albeit with some important limitations and considerations.

Figure 1.

Key strategies to ensure successful remote focus groups and interviews. IRB = institutional review board.

Throughout 2019, we collaborated on a series of stakeholder focus groups to explore clinician experiences with patient handoffs between the intensive care unit and the wards. These focus groups, conducted in-person at our respective academic medical centers, helped us delineate key strengths and “pain points” of our handoff processes and identify facilitators and barriers to the user-centered design and implementation of a new process (4). We had scheduled subsequent in-person focus groups for this iterative design and testing process to take place in Spring 2020. However, we were forced to recalibrate our plans based on the rapidly changing COVID-19 situation and the situations of our intended participants (internal medicine residents). This article provides some practical guidance and reflections based on our experiences conducting semistructured focus groups using a videoconference platform with internal medicine residents at three academic medical centers. We outline our recommendations by describing the process of these remote focus groups, from planning and recruitment to the execution and technical troubleshooting of the videoconference.

Setting the Stage

More than ever, healthcare professionals are overtaxed because of increased clinical responsibilities; new or altered clinical environments and workflows; and increased burdens of administrative, educational, and investigatory work conducted by phone, e-mail, and video conference (5–7). Because of the school and childcare facility closures, many healthcare professionals may be engaged in nonclinical work while simultaneously caring for their children or supervising remote learning (8). With this in mind, we recommend that researchers carefully consider the timing of planned focus groups or interviews to maximize participation and minimize the strain on potential participants. Whenever possible, researchers should seek input on optimal timing and duration from potential participants.

The flexibility of video conferencing may potentially allow researchers to recruit participants by eliminating transportation and transit time barriers and allows for increased flexibility to consider scheduling focus groups or interviews at nontraditional times to accommodate the participants’ schedules.

Overall, we recommend that focus groups are conducted over video rather than audio if unable to be done in-person. Audio-only experiences are inherently more challenging than remote video sessions; it is difficult to tell when participants are speaking but muted, to identify an individual speaker among many participants, and to interpret tone and body language. In addition, audio-only encounters often limit crosstalk, which can enhance the depth of responses. We acknowledge that video is less private than audio, but it may be more private than in-person (e.g., a participant may decline to enroll in an in-person interview or group around a sensitive topic if they do not wish to be seen physically entering or exiting a known research room). Consent must specify whether audio alone is being recorded, or whether video and audio are both recorded.

Most importantly, before recruitment and consent, researchers should identify which video teleconferencing platform (e.g., Zoom, Google Meet, or Microsoft Teams) is best suited for the project (Table 1); because these platforms share many of the same capabilities (e.g., screencasting/sharing and audio recording), this decision may be based on institutional adoption or availability.

Table 1.

Overview of several common videoconferencing platforms

| Zoom | Microsoft Teams | Google Meet | BlueJeans | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supported operating systems | Windows | Windows | Windows | Windows |

| MacOS | MacOS | MacOS | MacOS | |

| iOS | iOS | iOS | iOS | |

| Android | Android | Android | Android | |

| Web browser | Web browser | Web browser | Web browser | |

| Cost | Free tier available | Free tier available | Free tier available | Monthly charges for individuals or enterprise |

| Monthly charges for individuals or enterprise | Monthly charges for individuals or enterprise | Monthly charges for individuals or enterprise | ||

| Encryption | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Time limits | 40 min on free tier | No limits | 60 min on free tier | No limits |

| No limits on paid tiers | No limits on paid tiers | |||

| Screencasting supported | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Chat functionality | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Audio recording | Yes | Only on paid tiers | Only on paid tiers | Yes |

| Breakout rooms | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| Waiting room | Yes | No | No | No |

| Electronic calendar Integration | Outlook | Outlook | Outlook | Outlook |

| Google calendar | Google calendar | Google calendar | ||

| iCal | ||||

| HIPAA compliance | Available to organizations | Available to organizations | Available to organizations | Available to organizations |

Definition of abbreviation: HIPAA = Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Recruitment and Consent

Although some local institutional review board (IRB) procedures may have changed in response to COVID-19, qualitative research projects with human participants still require IRB review for determination of exempt status or formal approval. Researchers should obtain IRB approval to record the audio from the focus group or structured interview if a recording is desired.

Recruitment is likely to be predominantly virtual, in the form of e-mail “blasts” describing the study and providing the information needed for informed consent. After completing recruitment and selecting a video conferencing platform for the proposed research, we recommend providing attendees a password-protected electronic invitation to ensure the privacy of the session. In addition, it is helpful when this invitation includes an attached electronic calendar “event,” which can allow potential participants to quickly cross reference their electronic calendars, which are increasingly full of virtual meetings. Gray and colleagues found that participants wanted to synchronize these invitations with their electronic calendars and preferred the interview be limited to 1 hour at most, to avoid fatigue and schedule disruption (9). Zoom and other similar platforms offer a straightforward option for participants to add the session to their personal electronic calendars automatically. We recommend this method of invitation to increase convenience for participants who are increasingly accustomed to daily schedules of virtual meetings.

As with in-person focus groups, there is likely to be a “U-shaped” relationship between the number of participants and the volume and depth of insights gained within a session; too few participants may prevent dialogue and limit progress toward thematic saturation or uncovering new insights, whereas too many participants will preclude opportunities for deeper follow-up and will limit the amount of time that any single participant may contribute. Most commonly available videoconference platforms permit audience sizes of 50 or more, which far exceeds the number of participants a typical focus group would contain.

Presession Technical Preparation

It is crucial that researchers familiarize themselves with the interface and options of their chosen videoconference platform, both to maximize the effectiveness of their session facilitation and to improve their ability to solve common technical difficulties that may arise. This preparation should take place on the computing device that the researcher intends to use for research sessions to ensure that video, audio volume, and internet speed are adequate to host a successful video conference meeting. We recommend recording a practice session to become familiar with recording logistics and file storage locations, and to ensure the device’s microphone records clearly enough for participants’ hearing and transcription. Beyond the opportunity to troubleshoot the virtual platform, this practice session may also serve the second purpose of familiarizing the facilitator with the discussion questions.

Of note, researchers should evaluate the adequacy of their devices’ storage capabilities, given the large file sizes required to record audio and video. Many universities provide network storage solutions to members of their academic community, which may help facilitate storing large files. Importantly, if the research participants are patients, any recorded data (i.e., audio, video, and transcripts) are considered protected health information. These data require additional privacy considerations, especially around storage and electronic transfer. Because commercial video chat platforms may host or store files on their servers, the research team should ensure, ahead of time, that any commercial video chat platform used for research meets both the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act and institutional standards for secure data storage.

After successful completion of the trial run as a host, we recommend contacting the study participants before the session to ensure that any technical questions or concerns are addressed.

Introducing the Session

Initializing a virtual meeting is, in many ways, similar to initializing an in-person meeting. Like physical meetings, attendees may “trickle in” late because of preceding scheduled events or technical difficulties. We recommend allowing 1–5 minutes at the session’s beginning to account for late arrivals and to address technical issues if any are apparent. Once individuals are in the meeting, the facilitator can “lock” the session so uninvited attendees do not “Zoom-bomb.” In addition, researchers can further protect their meeting by using a Waiting Room, if available. Videoconference waiting rooms are virtual staging areas, which prevents attendees from joining a meeting until permitted, either individually or in a group, to enter. The facilitator should introduce the focus group or structured interviews just as they would an in-person session, including assurances regarding confidentiality, an overview of the session’s objectives, and an explicit statement of the session’s ground rules. The facilitator should obtain permission to record the focus group or structured interview and provide attendees the opportunity to leave the meeting if they do not consent to the recording. Finally, we recommend that researchers consider using a visual cue on a shared slide to remind them to initiate recording before beginning the session’s questions. Ideally, having two individuals record the meeting helps ensure redundancy so that if one individual has recording issues, the copy is preserved.

Depending on the size of the focus group or structured interview, the facilitator may wish to describe, at the meeting’s beginning, how attendee opinions will be solicited. For example, focus group participants can “unmute” themselves to speak or use the “raise hand” function on the meeting service. We recommend discouraging the use of the “chat” function because chat box contents are not recorded unless explicitly read aloud. If attendees do type in the chat box during the session, we recommend that the facilitator read the chat box contents aloud to capture these insights in the recording and transcript. Last, consider asking attendees to share their video feeds so participants and leaders can view attendee facial expressions and identify visual cues when individuals are about to speak (or are speaking, but are inadvertently muted). However, we recognize that this recommendation could limit participation by attendees without video-capable devices and/or put undue stress or burden on attendees who may be simultaneously parenting or multitasking. Above all, researchers should encourage attendees to make choices that will maximize their comfort with the session, and thus, maximize their contributions to the discussion.

During the Session

In general, remote qualitative inquiry sessions should follow a structure similar to that of face-to-face sessions. The facilitator should use effective moderation techniques online just as they would in-person. We have found that having an additional research team member serve as a scribe and timekeeper is helpful, if available. This teammate could also serve as a backup host if the primary host has unresolvable technical issues. Facilitators guiding semistructured interviews should ask follow-up probing questions and avoid sharing their own opinion, asking closed or leading questions, and other missteps that contribute to bias.

Within these general guidelines, however, the research team should be cognizant of the ways in which remote interactions differ from a live discussion. For instance, participants may be either more (e.g., because of additional perceived anonymity) or less (e.g., because of multitasking) likely to interact on videoconference, which may require proactive facilitation (e.g., direction questions or probes to individual participants). Similarly, a proactive facilitator may wish to be particularly attentive for openings to ask probing or follow-up questions, as some data suggest that online qualitative inquiry provides less opportunity for probing and follow-up (10). Furthermore, microphone technology is likely to preclude the degree of crosstalk seen in many face-to-face focus groups, which could limit the depth and quality of dialogue elicited. This lack of crosstalk may inhibit the ability to develop social norms, which are often a key factor distinguishing focus groups from individual structured interviews. It is not known whether facilitator behaviors or factors like focus group size can modify these limitations, although certain characteristics of focus group questions (e.g., open-ended) appear to yield richer discussion and data (10). Finally, if an audio-only focus group is the only option, we suggest using a visual model (e.g., a map or list of participants) to remind the facilitator of focus group participants, so notes can be transcribed visually under each participant.

Researchers should consider the need to maintain the privacy and potential anonymity of all participants, as outlined in the project’s IRB protocol. This consideration should also include any potential protected health information if the participants are patients. If strict anonymity is required, avoid stating participants’ names during the recording. If deidentification during transcription or review is appropriate, using the names of participants may increase the connection between the facilitator and the respondent, allowing for greater psychological safety.

After the Session

Concluding a virtual interview or focus group is similar to concluding an in-person session of the same type. The researchers should thank participants for their time, particularly given the stressors of the pandemic. In addition, we recommend discussing criteria for possible follow-up discussions. After ending the recording, ensure the file is saved to a secure location. Use professional transcription software to transcribe the audio recording from the focus group. Analyze the data with the qualitative framework outlined in the study design stage.

Because qualitative analysis of remote interviews and focus groups is typically conducted on transcribed audio, the decision to use a video platform often has little impact on data analysis. However, in some situations, the recorded video may prove advantageous. For example, the inclusion of video might facilitate the differentiation of speakers or clarification of unclear words during transcription or transcript reviews. Similarly, video might provide context around pauses, hand gestures, or facial expressions. Whether remote sessions have the same Hawthorne-esque effect on participants (i.e., do they behave in a particular way because of their awareness of being observed) is unknown. For instance, it is possible that participants behave differently when observed on video as compared with an audio-only (e.g., telephone) experience, or as compared with an in person session. One implication of this possibility could involve the perceived acceptability of multitasking or split attention; not infrequently, video participants elect not to share their individual video feeds.

Common Pitfalls and Strategies for Success

Qualitative interviews and focus groups, regardless of the setting, are subject to certain pitfalls along with a project’s progression from research question to analysis and dissemination. For instance, suboptimal recruitment practices (e.g., lack of advertisement) may limit enrollment, whereas incomplete or rushed interview scripts may not elicit complete or nuanced insights from participants. For remote interviews or focus groups, distance and technology may present additional obstacles (or interact with known risks), which can threaten a project’s success (Table 2). Overall, the virtual qualitative experience offers a tradeoff between participant availability and an increased number of potential distractions. Whether these potential threats to qualitative insight are worth access to participants who might be unable to attend face-to-face sessions is likely to vary across research questions and teams of investigators. In general, these pitfalls can be avoided or mitigated with careful preplanning, practice sessions, and deliberate attention to areas of risk.

Table 2.

Potential remote focus group pitfalls and related strategies for success

| Pitfalls | Success Strategies |

|---|---|

| Before the session | |

| Limited attendance | Advertising, incentives |

| Electronic calendar invitation | |

| Limit duration to 1 h or less | |

| During the session | |

| Technical difficulties | Arrange for a backup host at each session |

| Practice sessions, including pretesting virtual environment | |

| Dedicate beginning of session to orientation and technical troubleshooting | |

| Low participant engagement | Set “ground rules” at the beginning—ask participants to turn on video if able and to engage with full attention for the limited time |

| Can call on participants to draw out their thoughts if individuals are not being as responsive | |

| Suboptimal data collection | Backup host |

| Visual recording reminder | |

| Throughout | |

| Privacy risks | Work with IRB to ensure appropriate privacy protections, including HIPAA compliance when needed |

| Ensure that commercial video chat platform used for research meets both HIPAA and institutional standards for secure data storage | |

| Password-protect sessions | |

| Use the “waiting room” feature, when available | |

| Always consider privacy deliberately for both data storage and electronic transfer |

Definition of abbreviations: IRB = institutional review board; HIPAA = Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act.

Conclusions

We hope that these practical tips can help with conducting rigorous qualitative inquiry through remote focus groups or structured interviews in the era of physical and social distancing.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

Supported by an APCCMPD, CHEST, and ATS Education Research Award (L.S.).

Author Contributions: Conception and design: P.G.L. Drafting of the article: L.S., J.C.R., and P.G.L. Critical revision of the article for important intellectual content: L.S., J.C.R., and P.G.L. Final approval of the article: L.S., J.C.R., and P.G.L. Administrative, technical, or logistic support: P.G.L.

Author disclosuresare available with the text of this article atwww.atsjournals.org.

References

- 1. Teherani A, Martimianakis T, Stenfors-Hayes T, Wadhwa A, Varpio L. Choosing a qualitative research approach. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7:669–670. doi: 10.4300/JGME-D-15-00414.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gill P, Baillie J. Interviews and focus groups in qualitative research: an update for the digital age. Br Dent J. 2018;225:668–672. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2018.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care. 2007;19:349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rojas J, Lyons P, Garcia B, Thomashow M, Santhosh L. Design thinking to create user-centered intensive care unit-ward handoffs at three academic hospitals. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2020;201:A1401. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Mahul-Mellier AL. Screams on a Zoom call: the theory of homeworking with kids meets reality. Nature. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-01296-7. [online ahead of print] 1 May 2020; DOI: 10.1038/d41586-020-01296-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Morawo A, Sun C, Lowden M. Enhancing engagement during live virtual learning using interactive quizzes. Med Educ. 2020;54:1188. doi: 10.1111/medu.14253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Sasangohar F, Jones SL, Masud FN, Vahidy FS, Kash BA. Provider burnout and fatigue during the COVID-19 pandemic: lessons learned from a high-volume intensive care unit. Anesth Analg. 2020;131:106–111. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0000000000004866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gabster BP, van Daalen K, Dhatt R, Barry M. Challenges for the female academic during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet. 2020;395:1968–1970. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)31412-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gray LM, Wong-Wylie G, Rempel GR, Cook K. Expanding qualitative research interviewing strategies: Zoom video communications. Qual Rep. 2020;25:1292–1301. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Davies L, LeClair KL, Bagley P, Blunt H, Hinton L, Ryan S, et al. Face-to-face compared with online collected accounts of health and illness experiences: a scoping review. Qual Health Res. 2020;30:2092–2102. doi: 10.1177/1049732320935835. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.