Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced novel stressors into the lives of youth. Identifying factors that protect against the onset of psychopathology in the face of these stressors is critical. We examine a wide range of factors that may protect youth from developing psychopathology during the pandemic. We assessed pandemic-related stressors, internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, and potential protective factors by combining two longitudinal samples of children and adolescents (N = 224, 7–10 and 13–15 years) assessed prior to the pandemic, during the stay-at-home orders, and six months later. We evaluated how family behaviors during the stay-at-home orders were related to changes in psychopathology during the pandemic, identified factors that moderate the association of pandemic-related stressors with psychopathology, and determined whether associations varied by age. Internalizing and externalizing psychopathology increased substantially during the pandemic. Higher exposure to pandemic-related stressors was associated with increases in internalizing and externalizing symptoms early in the pandemic and six months later. Having a structured routine, less passive screen time, lower exposure to news media about the pandemic, and to a lesser extent more time in nature and getting adequate sleep were associated with reduced psychopathology. The association between pandemic-related stressors and psychopathology was reduced for youths with limited passive screen time and was absent for children, but not adolescents, with lower news media consumption related to the pandemic. We provide insight into simple, practical steps families can take to promote resilience against mental health problems in youth during the COVID-19 pandemic and protect against psychopathology following pandemic-related stressors.

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic has introduced unprecedented changes in the lives of children and adolescents. These changes brought a sudden loss of structure, routine, and sense of control. Families faced unique stressors ranging from unexpected illness, sudden unemployment and financial stressors, difficulty accessing basic necessities, and increased caretaking responsibilities paired with the shift to remote work, among others [1, 2]. Social distancing guidelines have limited youth’s contact with friends, extended family, and teachers, which may increase isolation and loneliness. Schools traditionally provide resources that may buffer youth against the negative consequences of stressors—including supportive social interactions, physical exercise, consistent meals, and a structured routine—that were unavailable to many U.S. youth for a prolonged period of time during the pandemic. These disruptions and pandemic-related stressors are likely to increase risk for depression, anxiety, and behavior problems in youth. Here, we identify factors that may protect against increases in mental health problems during the COVID-19 pandemic in a longitudinal sample assessed both prior to the pandemic and during the stay-at-home order period. We focus on simple and practical strategies that families can take in an effort to promote positive mental health outcomes in children and adolescents during the pandemic.

Exposure to stressors is strongly related to the onset of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology in children and adolescents [3–8]. The powerful association between stress and psychopathology has been replicated in longitudinal studies [7, 9, 10], including following community stressors, such as natural disasters [11, 12] and terrorist attacks [13–15]. Numerous pandemic-related experiences reflect novel stressors for youth and families, including unpredictability and daily routine disruptions [16, 17], unexpected loss of family members, friends, and loved ones [18], chronic exposure to information about threats to well-being and survival in situations that were previously safe [19], and social isolation [20]. Thus, exposure to pandemic-related stressors is likely to be associated with increases in anxiety, depression, and behavior problems in children and adolescents [1, 21, 22]. Indeed, emerging data demonstrates that youth psychopathology has increased during the COVID-19 pandemic [23].

Identifying factors that may promote youth well-being during the pandemic is a critical priority and has clear benefits for parents, pediatricians, and medical professionals. Leading theoretical models of resilience posit that factors that promote resilience exist across multiple levels including the individual, family, school, community, and broader cultural systems [24–26]. Critically, during the early period of the COVID-19 pandemic when schools were closed, stay-at-home orders were in place, and many community resources were shuttered, children were cut off from many common sources of resilience, particularly those occurring at the school and community levels. As such, home and family-level factors may have been of even greater importance than in normal circumstances. Furthermore, given the constraints faced by many families with children, we focus on a set of simple and practical strategies that are easily accessible, inexpensive, and require no specialized resources or services outside the home. We selected factors that have previously been associated with reduced child psychopathology or buffer against mental health problems following exposure to stressors, including: higher levels of physical activity [27–29]; access to nature and the outdoors [30–33]; a consistent daily routine providing structure and predictability [16, 34]; getting a sufficient amount of sleep, which is often disrupted following stressors [35–37]; and lower levels of passive screen time and news media consumption, given that higher use has been associated with elevations in child psychopathology [38], particularly following community-level stressors, like terrorist attacks [39–42].We also assessed the degree to which youth engaged in adaptive coping strategies during times of distress (e.g., exercising, seeking support from loved ones, or practicing mindfulness or meditation) [43–45]. Finally, providing help for others in need is associated with reduced anxiety and depression [46, 47]. Here, we evaluated whether these nine simple and inexpensive strategies are (a) associated with reduced psychopathology symptoms during the pandemic and (b) buffer against the negative mental health consequences of pandemic-related stressors in children and adolescents.

We examined these questions by combining two longitudinal samples of children and adolescents whose mental health was assessed prior to the COVID-19 pandemic in Seattle, Washington. This aspect of this study is critical because one of the strongest predictors of psychopathology during the pandemic is likely to be psychopathology prior to the pandemic. By controlling for pre-pandemic psychopathology, we are able to investigate changes in psychopathology that occurred during the pandemic. We then assessed pandemic-related stressors, internalizing and externalizing symptoms, and potential protective factors during six weeks between April and May of 2020—a period when the Seattle area was particularly hard-hit by the pandemic and stay-at-home orders were in place. We also followed up with participants six months later, between late November of 2020 and early January of 2021, to assess mental health. During this second follow-up, schools in the Seattle area were still operating virtually, social distancing guidelines were still in place, and new COVID-19 cases had reached a second peak. We examined whether exposure to pandemic-related stressors were associated with increases in internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, both concurrently and prospectively, controlling for pre-pandemic symptoms. We explored whether the potential protective factors were associated with changes in psychopathology during the pandemic or moderated the association of pandemic-related stressors with changes in psychopathology both during the stay-at-home orders and six months later. Finally, we tested whether these associations varied as a function of age, to determine whether the associations of potentially protective factors with psychopathology were similar for children and adolescents both concurrently and prospectively. Given the unique context of the COVID-19 pandemic, we did not have strong hypotheses about which particular protective factors would be more beneficial to children or adolescents. However, we did hypothesize that adolescents would show a stronger association between pandemic-related stress and psychopathology given previous work that shows that adolescence is a period of particular vulnerability to mental health problems following stressful life events [6, 7, 48–50].

Methods

Participants

Participants were recruited from two ongoing longitudinal studies of children and adolescents in the greater Seattle area. A sample of 224 youth aged 7–15 (Mage = 12.65, SD = 2.59, range: 7.64–15.24, 47.8% female) and a caregiver completed a battery of questionnaires to assess social behaviors and experiences and pandemic-related stressors. Participants also completed assessments of symptoms of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Two participants did not complete these mental health assessments and therefore were excluded from analyses. Six months later, 184 of these youth (82% of the initial pandemic sample) and a caregiver again completed an assessment of internalizing and externalizing symptoms. Ten participants did not complete these mental health assessments and therefore were excluded from analyses at T2. The racial and ethnic background of participants reflected the Seattle area, with 66% of participants identifying as White, 11% as Black, 11% as Asian, 8% as Hispanic or Latino, and 3% as another race or ethnicity.

Children from the first sample were recruited from a study of younger children (N = 99) originally recruited between January 2016 and September 2017 [51, 52]. Between March 2018 and November 2018, a subset of the original sample (N = 90) participated in a follow-up assessment of mental health. All participants who participated at baseline were contacted for the current study during the period of stay-at-home orders of the pandemic. From this sample, 68 youths (68.9% of the original sample; Mage = 8.88, range: 7.64–10.21, 53% female) and a caregiver participated in the first time point of current study (during the stay-at-home orders) and 53 completed the six-month follow-up. Mental health assessments obtained at age 6–8 years were used to control for pre-pandemic psychopathology. Three participants did not complete the most recent assessment, and mental health assessments at age 5–6 were used to control for pre-pandemic psychopathology.

Adolescent participants were drawn from a longitudinal study of children followed from early childhood to adolescence and their mothers [53]. Participants completed the most recent assessment at age 11–12 years (N = 227) between June 2017 and October 2018. These participants were re-contacted for assessment for the current study. From this sample, 154 youths (Mage = 14.3, range: 13.12–15.24, 46% female) and their caregiver completed the current study (67.8% of the most recently assessed sample) and 121 completed the six-month follow-up. Mental health assessments at age 11–12 were used to control for pre-pandemic psychopathology.

These two samples came from the same general population (youth in the Seattle area from a wide range of socioeconomic backgrounds). Critically, these two samples did not differ with regards to socioeconomic status, as measured by the income-to-needs ratio, sex distribution (ps > .8), or in exposure to pandemic-related stressors (p = .907).

Participants were excluded from the parent studies based on the following criteria: IQ < 80, active substance dependence, psychosis, presence of pervasive developmental disorders (e.g., autism), and psychotropic medication use. Across both samples, legal guardians provided informed consent and youths provided assent via electronic signature obtained using Qualtrics (Provo, UT). All study procedures were approved by the Institutional Review Board at Harvard University. Youth and their caregivers were each paid $50 for participating in the first wave of the study and $35 for the second wave.

Procedure

Parents and youth separately completed electronic surveys. Families contacted an experimenter if youth had trouble completing the surveys on their own, and an experimenter then called via phone or video chat and read the questions aloud and recorded their responses (this experimenter was blind to all data from the previous assessments). Data were collected during a six-week period between mid-April, 2020 and May 31st, 2020 (T1), during which schools were closed and stay-at-home orders were in place. A follow-up (T2) was conducted between late November 2020 and early January 2021 in which youth mental health was assessed again.

Pandemic-related stressors

We developed a set of questions to assess pandemic-related stressors (https://osf.io/drqku/; see S1 File). The assessment included health, financial, social, school, and physical environment stressors that occurred within the preceding month, based on both caregiver and child report (See Table 1). Given that the COVID-19 pandemic presented a wide range of unique stressors that have not occurred in prior community-wide disruptions, it was necessary to create a novel measure to assess these types of experiences. It is standard practice in the field to do so when novel events occur for which existing stress measures do not adequately capture the full extent of specific types of stressful experiences (e.g., to understand the unique hurricane-related stressors that occurred during Hurricane Katrina or experiences specific to the terrorist attacks on September 11th or the Oklahoma City bombing [12, 41, 54, 55].

Table 1. COVID-19 pandemic-related stressors and potential protective factors.

| Stressor Domain | Description | Number of Items | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Health Stressors | Participant contracted COVID-19; a parent, sibling or another relative contracted COVID-19; a partner or close friend contracted COVID-19; the participant knew someone who died of the virus; had a parent who was an essential worker (e.g. healthcare worker, grocery store worker) who was still working during the initial months of the pandemic. | 7 | |

| Social | having a difficult relationship with a parent or other member of the household that had gotten worse during the last month; experiencing loneliness a few times per week or more; and experiencing racism, prejudice or discrimination related to the pandemic. | 4 | |

| Financial | a parent was laid off or had other significant loss of employment; the family experienced food insecurity, assessed using previously-validated items [81, 82]; the family was evicted or otherwise were forced to leave their home because of financial reasons; the family experienced significant financial loss (e.g. due do loss of business, job loss, stock market losses, etc.). | 4 | |

| School | experiencing difficulty getting schoolwork done at home; the environment where the child does schoolwork is noisy. | 2 | |

| Physical Environment | crowding in the home based on the total number of people in the home divided by the approximate square footage reported by the parent [32] | 1 | |

| Potential Protective Factor | Description of Measurement | ||

| Physical Activity | Total minutes of physical activity per week | ||

| Time in Nature | Days per week they spent time in natural green spaces including parks, canals, nature areas, beaches, countryside, and farmland. | ||

| Time Outdoors | Days per week participants spend time outside of their home (e.g. backyard or neighborhood street) for at least 30 minutes | ||

| News Consumption | Time spent watching news coverage about the pandemic on a TV, computer, iPad or other electronic device per day. Scored as a binary variable with less than 2 hours per day being scored as 0, and 2 or more hours per day being scored as 1. | ||

| Passive Screen Time | Hours per day, on average spent watching video on an electronic device, passively scrolling through social media, looking at websites and online news, watching movies and TV. Summed for total passive screen time | ||

| Sleep Quantity | Binary measure computed using CDC recommended guidelines for children in this age range (9–12 hours per night for children aged 8–10; 8–9 hours per night for adolescents [83]. | ||

| Daily Routine | Participant report on a 4-point Likert scale about the extent to which their days had a fairly consistent routine. | ||

| Adaptive Coping Strategies | Binary measure. Participants were given a 1 if they endorsed any of the following ways of dealing with distress related to the coronavirus: talked to family or friends, exercised, meditated, or engaged in self-care activities. | ||

| Helping in Community | Binary measure. Participants were given a 1 if they endorsed having participated in any of the following activities: volunteering time at hospitals, donating or preparing food, donating money or supplies, giving shelter to displaced people, praying for others, writing letters or contacting isolated people, cheering on health care workers, or other ways of helping. | ||

We created a composite of pandemic-related stressors using a cumulative risk approach, [56] by determining the presence of each potential stressors (exposed versus not exposed), and creating a risk score reflecting a count of these stressors (18 maximum). Importantly, many previous studies demonstrate the utility and convergent validity of cumulative stress measures in relation to health outcomes, with a greater number of stressors predicting higher levels of mental and physical health problems [56]. Here, we provide additional evidence for convergent validity by showing that the number of stressors is moderately associated with a measure of perceived stress as measured by the Perceived Stress Scale in this sample (r = 0.399). This value is similar to the correlation between stressful life events and perceived stress observed in the original validity studies used to create the Perceived Stress Scale (r = 0.24-.35) [57].

We also assessed pandemic-related stressors at T2. Importantly we only asked about stressors occurring between T1 and T2. If, for example, a participant had family member who became ill with COVID-19 in April 2020, this would be counted in the pandemic-related stressors at T1, but not at T2. We used pandemic-related stressors at T1 in all analyses (including prospective analyses) but report on pandemic-related stressors at T2 to illustrate the ongoing nature of the pandemic during the second wave of data collection.

Potential protective factors

We assessed nine potentially protective aspects of youth and family behavior during the prior month: (a) physical activity, (b) time spent in nature, (c) time spent outdoors, (d) screen time, (e) news consumption, (f) sleep quantity, (g) family routines, (h) coping strategies, and (i) helping others (https://osf.io/drqku/, Table 1).

Internalizing and externalizing psychopathology

Psychopathology was assessed prior to the pandemic by parent and child report on the Youth Self Report (YSR) and Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) [58, 59]. The CBCL scales are widely used measures of youth emotional and behavioral problems and use normative data to generate age-standardized estimates of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. We used the highest T-scores from the caregiver or child on the Internalizing and Externalizing symptoms subscales as measures of pre-pandemic symptoms. The children who were 6–8 years old at the pre-pandemic time point did not complete the YSR; only the CBCL was used to compute their pre-pandemic symptoms at that time point. The use of the higher caregiver or child report for psychopathology is an implementation of the standard “or” rule used in combining caregiver and child reports of psychopathology. In this approach, if either a parent or child endorses a particular symptom it is counted with the assumption that if a symptom is reported, it is likely present. This is a standard approach in the literature on child psychopathology–for example it is how mental disorders are diagnosed in population-based studies of psychopathology in children and adolescents [60, 61].

To assess psychopathology at T1 and T2, parents and youths completed the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire, a widely-used assessment of youth mental health [62]. The SDQ has good reliability and validity [63, 64] and correlates strongly with the CBCL/YSR [65]. We chose to use the SDQ to reduce participant burden, as it has substantially fewer items than the CBCL/YSR. We used the highest reported value on the Internalizing and Externalizing symptoms subscales from the caregiver or child.

Family income

At T1, we asked caregivers to report their total combined family income for the 12 months prior to the onset of the pandemic in 14 bins. The median of the income bins was used except for the lowest and highest bins which were assigned $14,570 and $150,000, respectively. We then calculated the income-to-needs ratio by dividing the family’s income by the federal poverty line for a family of that size in 2020, with values less than one indicating income below the poverty line. Nine caregivers did not provide information on family income and were thus excluded from analyses. Median income-to-needs ratio was 4.19 (min = 0.35, max = 8.41).

Statistical analysis

We used linear regression to investigate the questions of interest. Continuous predictors were standardized using a z-score. Analyses were performed in R using the lme4 package and standardized coefficients are presented. Continuous age, sex, income-to-needs ratio, and pre-pandemic symptoms measured using the CBCL/YSR prior to the pandemic were included as covariates in all analyses. First, we examined the association of pandemic-related stressors with internalizing and externalizing symptoms, both concurrently and prospectively. Next, we examined the association of potential protective factors with internalizing and externalizing problems, both concurrently and prospectively. Then, we tested whether these factors moderated the association of pandemic-related stressors with psychopathology, both concurrently and prospectively. Finally, we computed interactions of each protective factor with age predicting psychopathology and the interaction of pandemic-related stressors, each potential protective factor, and age predicting psychopathology, both concurrently and prospectively. Simple slopes analysis was used to follow-up on significant interactions using the R pequod package. Stratification for simple slope analyses in analyses that used continuous moderators were conducted using a median split. In the case of age analyses, because there was a gap in age between the oldest children (10 years) and the youngest adolescents (13 years), stratifying by sample for these purposes was equivalent to stratifying by a median split. False discovery rate (FDR) correction was applied at the level of hypothesis such that we corrected for comparisons at T1 and T2 (e.g., association between physical activity and internalizing psychopathology at T1 and T2). Listwise deletion was used to handle missing data at T2, excluding participants from analysis who did not complete the second follow-up during the pandemic.

Results

Prior to the pandemic, 71 participants (31.7% of the sample) were in the subclinical or clinical range for internalizing problems and 39 participants (17.4% of the sample) were in the subclinical or clinical range for externalizing problems. Internalizing and externalizing symptoms increased substantially during the early phase of the pandemic. Specifically, 127 (56.7%) were in the subclinical or clinical range for internalizing problems and 126 (56.2%) were in the subclinical or clinical range for externalizing problems at the beginning of the pandemic.

See S1 File for the frequency of different domains of stressors at T1 and T2 (S1 Table in S1 File), the distribution of potential protective factors and psychopathology symptoms before and after the pandemic (S2 Table in S1 File), bivariate correlations between all study variables (S3 Table in S1 File) and associations between individual stressors and psychopathology at T1 and T2 (S4 Table in S1 File).

As expected, one of the strongest predictors of psychopathology during the pandemic was pre-pandemic psychopathology (see S3 Table in S1 File). Therefore, it is important to highlight that all analyses controlled for pre-pandemic psychopathology to assess changes in psychopathology specific to the pandemic period.

Pandemic-related stressors and psychopathology

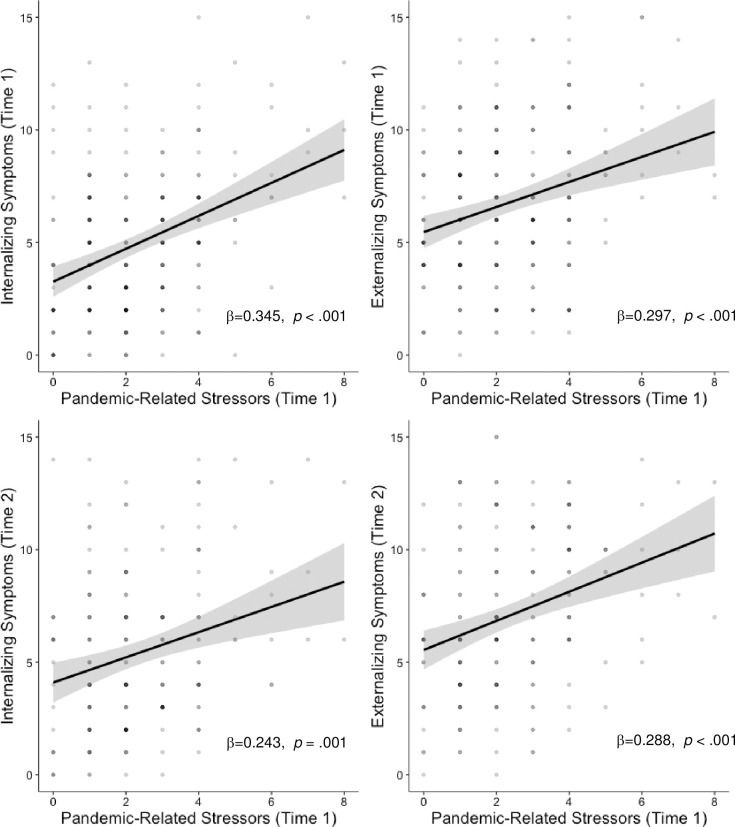

The number of pandemic-related stressors was strongly associated with increases in both internalizing (β = 0.345, p < .001), and externalizing symptoms (β = 0.297, p < .001) symptoms during the pandemic, controlling for pre-pandemic symptoms (Fig 1). As expected, pre-pandemic symptoms were also strongly associated psychopathology during the pandemic in this model (β = 0.279, p < .001 and β = 0.296, p < .001 for internalizing and externalizing psychopathology, respectively).

Fig 1. Main effects of pandemic-related stressors and psychopathology.

All analyses control for age, sex, income-to-needs and pre-pandemic psychopathology symptoms.

Similarly, the number of pandemic-related stressors early in the pandemic was positively associated with internalizing (β = 0.243, p = .001) and externalizing (β = 0.288, p < .001) symptoms later in the pandemic, controlling for pre-pandemic symptoms (Fig 1). Again, pre-pandemic symptoms were strongly associated with internalizing and externalizing problems at T2 (β = 0.260, p = .001 and β = 0.278, p < .001, respectively).

The association of pandemic-related stressors with internalizing symptoms varied by age (β = 0. 0.602, p = .043), such that the association was stronger among adolescents (simple slope: b = 0.437, p < .001) than children (simple slope: b = 0.220, p = .004) concurrently. There were interactions between age and pandemic-related stressors in predicting externalizing symptoms concurrently or prospectively.

Potential protective factors

Associations of potential protective factors with concurrent psychopathology and interactions with stress and age are summarized in Table 2. Associations of potential protective factors with prospective psychopathology and interactions with stress and age are summarized in Table 3.

Table 2. Associations of potential protective factors with psychopathology and interactions with stress and age at T1.

Significant associations are presented in BOLD and marginal associations are presented in italics.

| Protective Factors | Internalizing | Externalizing | Age Internalizing Interaction | Age Externalizing Interaction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | ||

| Physical Activity | Main effect | -0.120 | 0.132 | -0.016 | 0.900 | 0.075 | 0.826 | 0.391 | 0.243 |

| Stress Interaction | -0.153 | 0.191 | -0.146 | 0.448 | 0.151 | 0.790 | 0.609 | 0.588 | |

| Time in Nature | Main effect | -0.124 | 0.074 | 0.029 | 0.777 | 0.045 | 0.885 | 0.139 | 0.658 |

| Stress Interaction | -0.067 | 0.602 | 0.013 | 0.913 | -0.580 | 0.271 | 0.218 | 0.682 | |

| Time Outdoors | Main effect | 0.000 | 0.999 | 0.018 | 0.779 | -0.455 | 0.144 | -0.215 | 0.484 |

| Stress Interaction | -0.088 | 0.846 | -0.238 | 0.112 | -0.146 | 0.793 | 0.613 | 0.381 | |

| Passive Screen Time | Main effect | 0.059 | 0.431 | 0.272 | 0.0004 | -1.084 | 0.074 | -0.979 | 0.087 |

| Stress Interaction | 0.561 | 0.002 | 0.329 | 0.050 | -1.399 | 0.368 | 0.729 | 0.531 | |

| News Consumption | Main effect | 0.093 | 0.374 | 0.193 | 0.010 | -0.741 | 0.083 | -0.312 | 0.453 |

| Stress Interaction | 0.273 | 0.074 | 0.197 | 0.136 | -1.474 | 0.028 | 0.389 | 0.771 | |

| Sleep Quantity | Main effect | -0.018 | 0.995 | -0.061 | 0.370 | 0.674 | 0.130 | 0.551 | 0.126 |

| Stress Interaction | -0.171 | 0.326 | 0.094 | 0.762 | -1.728 | 0.064 | -0.623 | 0.451 | |

| Daily Routine | Main effect | -0.022 | 0.736 | -0.122 | 0.058 | -0.062 | 0.854 | -0.011 | 0.974 |

| Stress Interaction | -0.197 | 0.211 | -0.131 | 0.535 | 0.206 | 0.766 | 0.214 | 0.763 | |

| Adaptive Coping | Main effect | 0.061 | 0.688 | 0.124 | 0.102 | -0.436 | 0.377 | -0.040 | 0.906 |

| Stress Interaction | 0.177 | 0.276 | -0.083 | 0.488 | -0.587 | 0.630 | 1.225 | 0.078 | |

| Helping | Main effect | 0.002 | 0.978 | 0.012 | 0.848 | 0.401 | 0.231 | 0.186 | 0.575 |

| Stress Interaction | -0.059 | 0.623 | -0.081 | 0.968 | -0.348 | 0.571 | 0.674 | 0.281 | |

Table 3. Associations of potential protective factors with psychopathology and interactions with stress and age at T2.

Significant associations are presented in BOLD and marginal associations are presented in italics.

| Protective Factors | Internalizing | Externalizing | Age Internalizing Interaction | Age Externalizing Interaction | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | p | β | p | β | p | β | p | ||

| Physical Activity | Main effect | -0.049 | 0.515 | 0.009 | 0.900 | -0.126 | 0.826 | 0.534 | 0.243 |

| Stress Interaction | -0.241 | 0.179 | 0.028 | 0.816 | 0.712 | 0.686 | -0.182 | 0.802 | |

| Time in Nature | Main effect | -0.136 | 0.074 | -0.021 | 0.777 | -0.264 | 0.885 | 0.371 | 0.516 |

| Stress Interaction | 0.077 | 0.602 | 0.069 | 0.913 | -0.706 | 0.271 | -0.869 | 0.300 | |

| Time Outdoors | Main effect | -0.048 | 0.999 | 0.066 | 0.750 | -0.566 | 0.144 | -0.351 | 0.484 |

| Stress Interaction | 0.029 | 0.846 | -0.163 | 0.254 | 0.543 | 0.793 | 0.568 | 0.381 | |

| Passive Screen Time | Main effect | 0.097 | 0.431 | 0.157 | 0.076 | -1.953 | 0.030 | -1.264 | 0.087 |

| Stress Interaction | 0.401 | 0.049 | 0.606 | 0.003 | -1.243 | 0.368 | 1.158 | 0.531 | |

| News Consumption | Main effect | -0.040 | 0.627 | 0.114 | 0.152 | -1.743 | 0.004 | -0.932 | 0.170 |

| Stress Interaction | 0.034 | 0.829 | 0.223 | 0.136 | -2.199 | 0.018 | 0.238 | 0.771 | |

| Sleep Quantity | Main effect | 0.000 | 0.995 | -0.158 | 0.080 | 0.299 | 0.479 | 0.682 | 0.126 |

| Stress Interaction | 0.045 | 0.761 | 0.043 | 0.762 | -1.685 | 0.089 | -1.562 | 0.184 | |

| Daily Routine | Main effect | 0.034 | 0.736 | -0.164 | 0.049 | -0.129 | 0.854 | 0.589 | 0.238 |

| Stress Interaction | -0.191 | 0.221 | 0.092 | 0.535 | -0.648 | 0.766 | -0.865 | 0.666 | |

| Adaptive Coping | Main effect | -0.015 | 0.845 | 0.103 | 0.156 | -0.353 | 0.377 | -0.152 | 0.906 |

| Stress Interaction | 0.099 | 0.506 | 0.153 | 0.488 | -0.149 | 0.849 | 0.218 | 0.767 | |

| Helping | Main effect | 0.036 | 0.978 | 0.026 | 0.848 | 0.835 | 0.064 | -0.237 | 0.575 |

| Stress Interaction | -0.088 | 0.623 | -0.005 | 0.968 | 1.296 | 0.186 | 1.054 | 0.281 | |

Physical activity

Physical activity was unrelated to psychopathology concurrently or prospectively.

Time spent in nature and outdoors

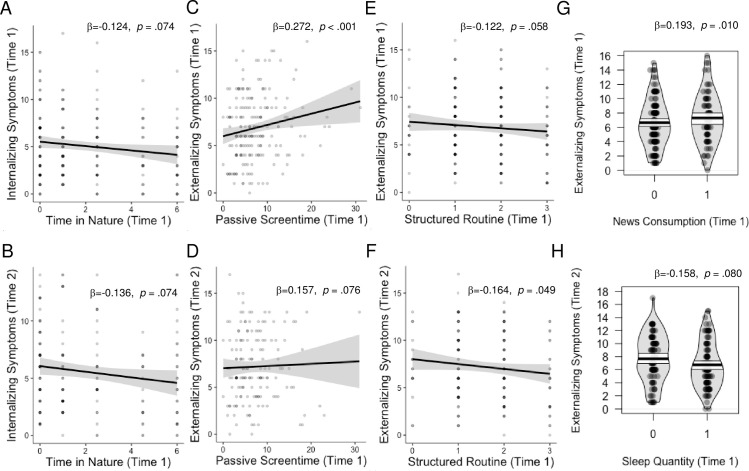

Greater time spent in nature was marginally associated with lower internalizing problems both concurrently and prospectively (Fig 2A and 2B), controlling for pre-pandemic symptoms. Time spent outdoors was unrelated to psychopathology. Age did not moderate any of these associations.

Fig 2. Main effects of protective factors on psychopathology.

All analyses controlled for age, sex, income-to-needs, and pre-pandemic psychopathology symptoms.

News consumption and passive screen time

Early in the pandemic, youths who spent less time on digital devices each day had lower externalizing symptoms (Fig 2C and 2D), controlling for pre-pandemic symptoms. Consuming <2 hours of news per day was also associated with reduced externalizing symptoms early in the pandemic (Fig 2G).

The longitudinal association between screen time and internalizing symptoms varied by age (S1 Fig in S1 File), such that children showed a positive association between screen time and internalizing psychopathology six months later (b = 0.572, p = .008), but adolescents did not (b = -0.074, p = .512).

Age moderated the association between news consumption and internalizing psychopathology prospectively. Specifically, while children showed a positive association between news consumption and internalizing psychopathology at T2 (b = 0.438, p = 0.015), adolescents showed a negative association between news consumption and internalizing psychopathology at T2 (b = -0.299, p = .015).

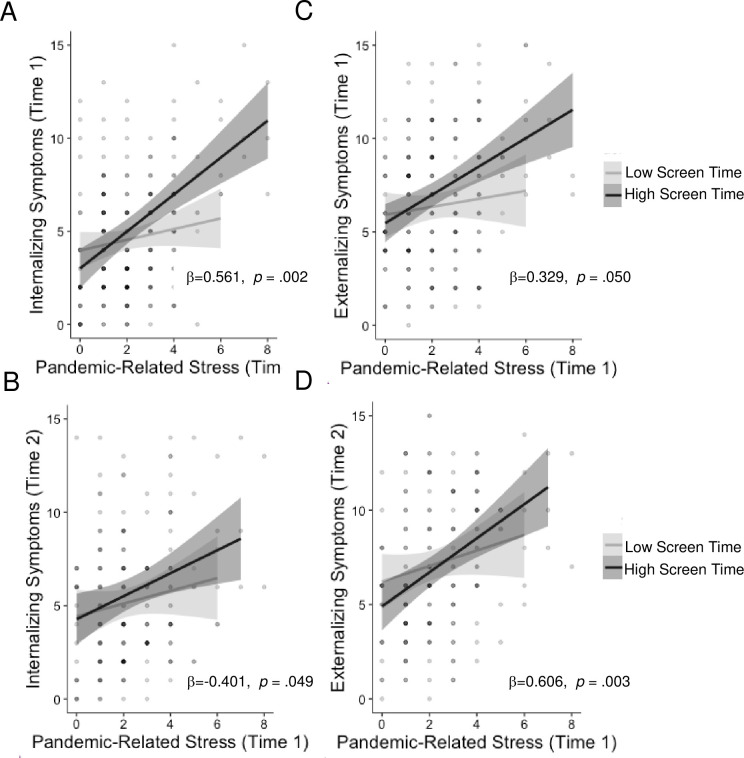

Screen time moderated the association of pandemic-related stressors with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology concurrently and prospectively (Fig 3). Specifically, youths who spent more time on screens showed a strong positive association of pandemic-related stressors with concurrent (b = 0.513, p < .001) and prospective (b = .335, p < .001) internalizing symptoms as well as both concurrent (b = 0.285, p < .001) and prospective (b = .383, p < .001) externalizing problems that was absent for youths who spent less time on screens at both time points (b = 0.020–0.061, p = .445-.935).

Fig 3. Passive screen time x stress interaction.

Low screen time use buffers against pandemic-related increases in internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. All analyses control for age, sex, income-to-needs ratio, and pre-pandemic psychopathology symptoms.

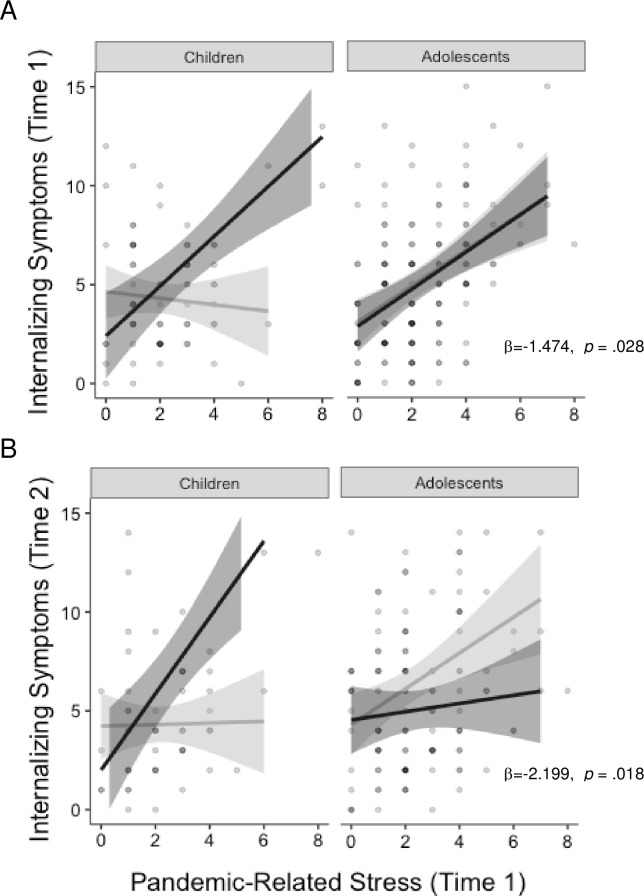

A three-way interaction was observed between news consumption, age, and pandemic-related stressors in predicting internalizing symptoms both concurrently and prospectively (Fig 4). Pandemic-related stressors were unrelated to internalizing problems concurrently (b = -.087, p = .502) or prospectively (b = -0.036, p = .808) among children who consumed <2 hours of news media per day, but were strongly associated with internalizing psychopathology both concurrently (b = 0.39 2, p < .001) and prospectively (b = 0.328, p = .026) among children with >2 hours daily news consumption. Among adolescents, pandemic-related stressors were strongly associated with internalizing problems concurrently (b = 0.409–0.452, p < .001), regardless of news consumption. Adolescents who consumed low levels of news during the stay-at-home orders showed a positive association between pandemic-related stressors and internalizing psychopathology six months later (b = 0.509, p = .002), while adolescents who consumed more news did not (b = 0.113, p = .346).

Fig 4. Age x stress x news interaction.

Low news consumption buffers children, but not adolescents, against pandemic-related increases in internalizing psychopathology concurrently (A) and prospectively (B). All analyses control for age, sex, income-to-needs ratio, and pre-pandemic psychopathology symptoms.

Sleep quantity

Getting the recommended number of hours of sleep was unrelated to psychopathology concurrently. However, getting the recommended amount of sleep during the stay-at-home orders was marginally associated with lower levels of externalizing psychopathology six months later, controlling for pre-pandemic symptoms (Fig 2H). These associations did not vary by age.

Routine

Youths with a more structured daily routine had lower externalizing (Fig 2E and 2F) six months later. No associations of a structured routine were found with internalizing symptoms, and no interactions with age or stress emerged.

Coping strategies

There was no significant association between engaging in adaptive coping strategies with psychopathology concurrently or prospectively.

Helping others

Helping in one’s community was unrelated to psychopathology concurrently or prospectively.

Discussion

The present study identifies simple and practical behaviors that are associated with well-being among children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Critically, this study involved a longitudinal sample of children and adolescents for which mental health had been assessed prior to the pandemic, during the stay-at-home orders, and six months later allowing us to investigate psychopathology during the pandemic while controlling for pre-pandemic symptoms. As expected, we found that youths who experienced greater pandemic-related stressors had higher levels of internalizing and externalizing psychopathology. Importantly, greater pandemic-related stressors during the stay-at-home orders were also prospectively associated with higher levels of both internalizing and externalizing psychopathology six months later. Critically, we identified several factors—including a structured daily routine, low passive screen time use, low news media consumption about the pandemic, and to a lesser extent spending more time spent in nature and getting the recommended amount of sleep—that are associated with better mental health outcomes in youth during the pandemic. We additionally demonstrate that the strong association between pandemic-related stressors and psychopathology is absent among children with lower amounts of screen time and news media consumption.

Youth who had a structured and predictable daily routine were less likely to experience increases in externalizing problems during the pandemic than youth with less structured routines. A sudden loss of routine has occurred for many families during the pandemic related to school closures, changes in parental work arrangements, and loss of access to activities outside the home for youth and adolescents. These disruptions in daily routine are associated with increased risk for behavior problems in youth during the pandemic, consistent with prior work suggesting that lack of predictability is strongly linked to youth psychopathology [16, 34, 66, 67]. Moreover, a recent paper during the pandemic showed that preschoolers in families that maintained a structured routine during the pandemic showed lower rates of depression and externalizing problems, over and above the effect of food insecurity, socioeconomic status, dual-parent status, maternal depression, and stress [68]. Our current findings extend this work by demonstrating that a structured routine may also be important for older children and adolescents. Although maintaining routine and structure is challenging as school closures continue and many aspects of daily life remain unpredictable, creating a structured daily routine for children and adolescents may promote better mental health during the pandemic.

Greater passive screen time use was associated with higher levels of externalizing psychopathology early in the pandemic, and greater passive screen time use was associated with higher internalizing psychopathology later in the pandemic for children but not adolescents. Additionally, the strong association of pandemic-related stressors with internalizing and externalizing psychopathology both concurrently and prospectively was reduced in children and adolescents with low passive screen time use. Previous studies have argued that the increases in screen time use over the last decade may be responsible for rising levels of anxiety and depression among children and adolescents [38]. However, others have suggested that greater screen time use may not have negative impacts [69, 70] and that psychopathology and digital device use have a reciprocal association with one another [71]. During the pandemic, youths were encouraged to use digital devices more than ever for school and social connection, which are likely to be beneficial for their development. Here, we measured passive use of digital devices, including watching videos on an electronic device, passively scrolling through social media, looking at websites and online news, and watching movies and TV—excluding more active uses of digital devices for schooling and social communication. Greater research is needed to determine whether the amount of passive screen time itself has negative effects on youth mental health or whether this association simply reflects that greater time on digital devices takes time away from other important behaviors such as exercise, sleep, or connecting with friends or family. Indeed, in the present study, screen time was inversely related with sleep quantity (S3 Table in S1 File). Therefore, one reason that youths with lower screen time use may be buffered against pandemic-related increases in psychopathology is because they are engaging in other behaviors that promote well-being such as getting sufficient sleep, among others. Together, these findings suggest some potential benefits associated with limiting passive screen time among youth during the pandemic.

Our findings also suggest that limiting news consumption about the pandemic may be beneficial, particularly for younger children. Greater news media consumption about the pandemic was associated with higher levels of externalizing problem early in the pandemic. Moreover, the strong association between pandemic-related stressors and internalizing psychopathology was absent in children who consumed lower levels of news media, although pandemic-related stressors were positively associated with internalizing symptoms in adolescents regardless of news consumption concurrently. This finding is broadly consistent with previous studies observing strong associations between media exposure about community-level stressors, including terrorist attacks and natural disasters, and higher rates of psychopathology in children and adolescents [41, 42, 72–74]. Interestingly, the same pattern persisted for children six months into the pandemic, while for adolescents who consumed more news during the stay-at-home orders showed a weaker association between stress and internalizing psychopathology six months later than those who consumed less news. Therefore, it is possible that for adolescents, having more knowledge about the pandemic early on may have been beneficial over time. Together these findings suggest that limiting certain types of news media exposure may protect against pandemic-related increases in internalizing problems, especially among young children. Importantly, this does not imply that parents should refrain from discussing the pandemic or hide the realities from their children. In fact, previous studies have found that honest conversations between parents and children provide an important protection against the development of psychopathology in the wake of natural disasters [75]. Therefore, we suggest limiting sensational news media consumption, in favor of talking to children about what is happening, listening to their concerns, and answering their questions in an age-appropriate manner.

Additionally, we found weaker and only marginally significant associations between time spent in nature and getting the recommended amount of sleep with youth psychopathology during the pandemic. We briefly discuss these findings here, as they highlight additional strategies that could be beneficial to families when considering how to support the mental health of their children during the pandemic. Greater time spent in nature was marginally associated with lower increases in internalizing symptoms relative to pre-pandemic symptoms both concurrently and prospectively. These findings are broadly consistent with prior evidence that spending at least two hours in nature per week is associated with greater well-being in adults [31] and better mental health in children [76]. Additionally, the association of stressors with well-being is reduced among children with greater access to nature [77]. Encouraging youths to spend time in nature may also be beneficial for mental health during the pandemic. In addition, children and adolescents who got the recommended amount of sleep at the beginning of the pandemic showed marginally lower levels of externalizing psychopathology six months later. These findings highlight the importance of encouraging youths to get an adequate amount sleep. Given the negative association between screen time and sleep duration both here and in prior work [78], reducing access to digital devices prior to bedtime may be one simple strategy parents can use to make it easier for their children to get an adequate amount of sleep.

Limitations

The present study has several limitations which should be acknowledged. First, we relied on self-report measures of behavior, which can be inaccurate due to recall bias. Future studies may benefit from using actigraphy to assess physical activity and sleep, geolocation to measure time spent in nature and outdoors, and direct reports of screen time use and news media consumption from digital devices for more accurate measures of potential protective factors. Second, while the longitudinal nature of the present study is a strength, it only included two snapshots of youth behavior and mental health during the pandemic. It will be important to continue to follow youths throughout the pandemic to determine factors that promote long-term risk and resilience. Third, we used a different measure of psychopathology prior to the pandemic (CBCL/YSR) than after the onset of the pandemic (SDQ). While it would have been ideal to have the same measure at all time points, the CBCL/YSR is much longer than the SDQ and we were focused on minimizing participant burden during a period of time when families were facing numerous stressors and loss of access to typical childcare options. Thus, we chose to use a shorter questionnaire that is strongly correlated with the CBCL/YSR [62, 65, 79, 80]. Relatedly, we asked questions about potential protective factors in our COVID Experiences Survey, rather than using longer validated scales for each of the factors (e.g. Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index, Physical Activity Questionnaire for Children, Media Parenting Practices, Family Routines Inventory, German Coping Questionnaire for `Children and Adolescents, etc.). This choice was made to maximize the information gained about each family, while minimizing participant burden and thus maximizing our sample size. Fourth, we combined data from two separate samples of children (aged 7–10 and 13–15 at T1). Both samples were recruited using similar methods from the same target population, and we had identical measures of pre-pandemic psychopathology on both samples. Moreover, the samples did not differ in demographics, SES, or exposure to pandemic-related stressors. However, using two samples with a gap in age limited our ability to understand age effects across the entire spectrum of childhood and adolescence. Fifth, we demonstrate the predictive validity of the pandemic-related stress measure via moderate associations with psychopathology at both waves as well as a measure of perceived stress. However, this cumulative risk approach is limited in that it weights stressors equally that could have variable impacts. Future work should investigate whether specific stressors have been more strongly linked to changes in mental health during the pandemic (see S4 Table in S1 File for associations of specific stressors and psychopathology at T1 and T2). Finally, the present study is correlational and we are therefore limited in our ability to make causal inferences about the factors that promote well-being during the pandemic. However, given the extensive literature about the links between these factors and youth mental health, there is little reason to expect downsides to encouraging families to engage in these types of protective behaviors with their children and adolescents during the pandemic.

Conclusions and practical implications

We identify practical and easily accessible strategies that may promote greater well-being for children and adolescents during the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on these findings, we suggest that parents encourage youth to develop a structured daily routine, limit passive screen time use, limit exposure to news media—particularly for young children, and to a lesser extent spend more time in nature, and encourage youth to get the recommended amount of sleep.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The authors would also like to acknowledge Reshma Sreekala for help with data collection and Frances Li for help with compiling surveys.

Data Availability

All data are available on open science framework https://osf.io/y7cmj/.

Funding Statement

Funding/Support: This work was supported by the Bezos Family Foundation (to ANM) for collection of data. This work was also supported by the National Institute of Child Health and Human development (F32 HD089514 and K99 HD099203 to MLR) and the National Institute of Mental Health (R01 MH106482 to KAM).

References

- 1.Gruber J, Prinstein MJ, Clark LA, Rottenberg J, Abramowitz JS, Albano AM, et al. Mental health and clinical psychological science in the time of COVID-19: Challenges, opportunities, and a call to action. Am Psychol. 2020. 10.1037/amp0000707 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown SM, Doom JR, Lechuga-Peña S, Watamura SE, Koppels T. Stress and parenting during the global COVID-19 pandemic. Child Abuse Negl. 2020;110(Pt 2):104699. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2020.104699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kessler RC, Davis CG, Kendler KS. Childhood adversity and adult psychiatric disorder in the US National Comorbidity Survey. Psychol Med. 1997;27(5):1101–19. doi: 10.1017/s0033291797005588 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, Zaslavsky AM, Kessler RC. Childhood adversities and first onset of psychiatric disorders in a national sample of US adolescents. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(11):1151–60. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.2277 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hankin BL, Abela JRZ. Development of psychopathology: A vulnerability-stress perspective. Thousand Oaks: Sage; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Grant KE, Compas BE, Stuhlmacher AF, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, Halpert JA. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Moving from markers to mechanisms of risk. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(3):447–66. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.3.447 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Grant KE, Compas BE, Thurm AE, McMahon SD, Gipson PY. Stressors and child and adolescent psychopathology: Measurement issues and prospective effects. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2004;33(2):412–25. doi: 10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLaughlin KA. Future directions in childhood adversity and youth psychopathology. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2016;45(3):361–82. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2015.1110823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenness JL, Peverill M, King KM, Hankin BL, McLaughlin KA. Dynamic associations between stressful life events and adolescent internalizing psychopathology in a multiwave longitudinal study. J Abnorm Psychol. 2019;128(6):596–609. doi: 10.1037/abn0000450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McLaughlin KA, Hatzenbuehler ML. Mechanisms linking stressful life events and mental health problems in a prospective, community-based sample of adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2009;44(2):153–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.06.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.La Greca AM, Silverman WK, Vernberg EM, Prinstein MJ. Symptoms of posttraumatic stress in children after Hurricane Andrew: A prospective study. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1996;64(4):712–23. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.64.4.712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McLaughlin KA, Fairbank JA, Gruber MJ, Jones RT, Lakoma MD, Pfefferbaum B, et al. Serious emotional disturbance among youths exposed to Hurricane Katrina 2 years postdisaster. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2009;48(11):1069–78. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181b76697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hoven CW, Duarte CS, Lucas CP, Wu P, Mandell DJ, Goodwin RD, et al. Psychopathology among New York City public school children 6 months after September 11. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62(5):545–52. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.62.5.545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mullett-Hume E, Anshel D, Guevara V, Cloitre M. Cumulative trauma and posttraumatic stress disorder among children exposed to the 9/11 World Trade Center attack. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2008;78(1):103–8. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.78.1.103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lengua LJ, Long AC, Smith KI, Meltzoff AN. Pre-attack symptomatology and temperament as predictors of children’s responses to the September 11 terrorist attacks. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(6):631–45. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00378.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Glynn LM, Stern HS, Howland MA, Risbrough VB, Baker DG, Nievergelt CM, et al. Measuring novel antecedents of mental illness: The Questionnaire of Unpredictability in Childhood. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2019;44(5):876–82. doi: 10.1038/s41386-018-0280-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chorpita BF, Barlow DH. The development of anxiety: The role of control in the early environment. Psychol Bull. 1998;124(1):3–21. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.124.1.3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Keyes KM, Pratt C, Galea S, McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Shear MK. The burden of loss: Unexpected death of a loved one and psychiatric disorders across the life course in a national study. Am J Psychiatry. 2014;171(8):864–71. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13081132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kendler KS, Hettema JM, Butera F, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Life event dimensions of loss, humiliation, entrapment, and danger in the prediction of onsets of major depression and generalized anxiety. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60(8):789–96. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.8.789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matthews T, Danese A, Wertz J, Ambler A, Kelly M, Diver A, et al. Social isolation and mental health at primary and secondary school entry: A longitudinal cohort study. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2015;54(3):225–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2014.12.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pfefferbaum B, North CS. Mental health and the Covid-19 pandemic. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(6):510–2. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp2008017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fegert JM, Vitiello B, Plener PL, Clemens V. Challenges and burden of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic for child and adolescent mental health: A narrative review to highlight clinical and research needs in the acute phase and the long return to normality. Child Adolesc Psychiatry Ment Health. 2020;14:20. doi: 10.1186/s13034-020-00329-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chahal R, Kirshenbaum JS, Miller JG, Ho TC, Gotlib IH. Higher executive control network coherence buffers against puberty-related increases in internalizing symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic. Biol Psychiatry Cogn Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2021;6(1):79–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2020.08.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Masten AS. Resilience theory and research on children and families: Past, present, and promise. Journal of Family Theory and Review. 2018;10(1):12–31. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Masten AS, Motti-Stefanidi F. Multisystem resilience for children and youth in disaster: Reflections in the context of COVID-19. Advers Resil Sci. 2020;1:95–106. doi: 10.1007/s42844-020-00010-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Masten AS. Resilience of children in disasters: A multisystem perspective. Int J Psychol. 2021;56(1):1–11. doi: 10.1002/ijop.12737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bernstein EE, McNally RJ. Acute aerobic exercise helps overcome emotion regulation deficits. Cogn Emot. 2017;31(4):834–43. doi: 10.1080/02699931.2016.1168284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bernstein EE, McNally RJ. Exercise as a buffer against difficulties with emotion regulation: A pathway to emotional wellbeing. Behav Res Ther. 2018;109:29–36. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2018.07.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schuch FB, Vancampfort D, Rosenbaum S, Richards J, Ward PB, Stubbs B. Exercise improves physical and psychological quality of life in people with depression: A meta-analysis including the evaluation of control group response. Psychiatry Res. 2016;241:47–54. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Maas J, Verheij RA, de Vries S, Spreeuwenberg P, Schellevis FG, Groenewegen PP. Morbidity is related to a green living environment. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2009;63(12):967–73. doi: 10.1136/jech.2008.079038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.White MP, Alcock I, Grellier J, Wheeler BW, Hartig T, Warber SL, et al. Spending at least 120 minutes a week in nature is associated with good health and wellbeing. Sci Rep. 2019;9:7730. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-44097-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Evans GW. Child development and the physical environment. Annu Rev Psychol. 2006;57:423–51. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.57.102904.190057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cox DTC, Shanahan DF, Hudson HL, Fuller RA, Anderson K, Hancock S, et al. Doses of nearby nature simultaneously associated with multiple health benefits. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2017;14(2):172. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14020172 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fiese BH, Tomcho TJ, Douglas M, Josephs K, Poltrock S, Baker T. A review of 50 years of research on naturally occurring family routines and rituals: Cause for celebration? J Fam Psychol. 2002;16(4):381–90. doi: 10.1037//0893-3200.16.4.381 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim EJ, Dimsdale JE. The effect of psychosocial stress on sleep: A review of polysomnographic evidence. Behav Sleep Med. 2007;5(4):256–78. doi: 10.1080/15402000701557383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sadeh A, Gruber R. Stress and sleep in adolescence: A clinical-developmental perspective. In: Carskadon MA, editor. Adolescent sleep patterns: Biological, social, and psychological influences.Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2009. pp. 236–253. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vidal Bustamante CM, Rodman AM, Dennison MJ, Flournoy JC, Mair P, McLaughlin KA. Within-person fluctuations in stressful life events, sleep, and anxiety and depression symptoms during adolescence: A multiwave prospective study. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2020;61(10):1116–25. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13234 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Twenge JM, Campbell WK. Associations between screen time and lower psychological well-being among children and adolescents: Evidence from a population-based study. Prev Med Reports. 2018;12:271–83. doi: 10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.10.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gold AL, Sheridan MA, Peverill M, Busso DS, Lambert HK, Alves S, et al. Childhood abuse and reduced cortical thickness in brain regions involved in emotional processing. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2016;57(10):1154–64. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Busso DS, McLaughlin KA, Sheridan MA. Media exposure and sympathetic nervous system reactivity predict PTSD symptoms after the Boston Marathon bombings. Depress Anxiety. 2014;31(7):551–8. doi: 10.1002/da.22282 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pfefferbaum B, Seale TW, McDonald NB, Brandt EN, Rainwater SM, Maynard BT, et al. Posttraumatic stress two years after the Oklahoma City bombing in youths geographically distant from the explosion. Psychiatry. 2000;63(4):358–70. doi: 10.1080/00332747.2000.11024929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fairbrother G, Stuber J, Galea S, Fleischman AR, Pfefferbaum B. Posttraumatic stress reactions in New York City children after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks. Ambul Pediatr. 2003;3(6):304–11. doi: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kallapiran K, Koo S, Kirubakaran R, Hancock K. Review: Effectiveness of mindfulness in improving mental health symptoms of children and adolescents: A meta-analysis. Child Adolesc Ment Health. 2015;20(4):182–94. doi: 10.1111/camh.12113 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wegner M, Amatriain-Fernández S, Kaulitzky A, Murillo-Rodriguez E, Machado S, Budde H. Systematic review of meta-analyses: Exercise effects on depression in children and adolescents. Front Psychiatry. 2020;11:81. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00081 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cohen S. Social relationships and health. Am Psychol. 2004;59(8):676–84. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Liang J, Krause NM, Bennett JM. Social exchange and well-being: Is giving better than receiving? Psychol Aging. 2001;16(3):511–23. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.16.3.511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Doré BP, Morris RR, Burr DA, Picard RW, Ochsner KN. Helping others regulate emotion predicts increased regulation of one’s own emotions and decreased symptoms of depression. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2017;43(5):729–39. doi: 10.1177/0146167217695558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Espejo EP, Hammen CL, Connolly NP, Brennan PA, Najman JM, Bor W. Stress sensitization and adolescent depressive severity as a function of childhood adversity: A link to anxiety disorders. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2007;35(2):287–299. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9090-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Larson R, Ham M. Stress and “storm and stress” in early adolescence: The relationship of negative events with dysphoric affect. Dev Psychol. 1993;29(1):130–140. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Monroe SM, Rohde P, Seeley JR, Lewinsohn PM. Life events and depression in adolescence: Relationship loss as a prospective risk factor for first onset of major depressive disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 1999;108(4):606–614. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.108.4.606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Rosen ML, Hagen MP, Lurie LA, Miles ZE, Sheridan MA, Meltzoff AN, et al. Cognitive stimulation as a mechanism linking socioeconomic status with executive function: A longitudinal investigation. Child Dev. 2020;91(4):e762–79. doi: 10.1111/cdev.13315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosen ML, Meltzoff AN, Sheridan MA, McLaughlin KA. Distinct aspects of the early environment contribute to associative memory, cued attention, and memory-guided attention: Implications for academic achievement. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 2019;40:100731. doi: 10.1016/j.dcn.2019.100731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lengua LJ, Moran L, Zalewski M, Ruberry E, Kiff C, Thompson S. Relations of growth in effortful control to family income, cumulative risk, and adjustment in preschool-age children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2015;43(4):705–20. doi: 10.1007/s10802-014-9941-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Galea S, Ahern J, Resnick H. Psychological sequelae of the September 11 terrorist attacks in New York City. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;346(13):982–987. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa013404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Galea S, Brewin CR, Gruber M, Jones RT, King DW, King LA, et al. Exposure to hurricane-related stressors and mental illness after Hurricane Katrina. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64(12):1427–1434. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.12.1427 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Evans GW, Li D, Whipple SS. Cumulative risk and child development. Psychol Bull. 2013;139(6):1342–96. doi: 10.1037/a0031808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–396. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Achenbach TM, Dumenci L, Rescorla LA. DSM-oriented and empirically based approaches to constructing scales from the same item pools. J Clin Child Adolesc Psychol. 2003;32(3):328–40. doi: 10.1207/S15374424JCCP3203_02 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Achenbach TM. Integrative guide for the 1991 CBCL/4-18, YSR, and TRF profiles. Burlington: University of Vermont, Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kessler RC, Avenevoli S, Costello EJ, Georgiades K, Green JG, Gruber MJ, et al. Prevalence, persistence, and sociodemographic correlates of DSM-IV disorders in the National Comorbidity Survey Replication Adolescent Supplement. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2012;69(4):372–380. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, et al. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in U.S. adolescents: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication-adolescent supplement (NCS-A). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49(10):980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Goodman R. Psychometric properties of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(11):1337–45. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200111000-00015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Dickey WC, Blumberg SJ. Revisiting the factor structure of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire: United States, 2001. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2004;43(9):1159–67. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000132808.36708.a9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goodman A, Lamping DL, Ploubidis GB. When to use broader internalising and externalising subscales instead of the hypothesised five subscales on the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ): Data from British parents, teachers and children. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 2010;38(8):1179–91. doi: 10.1007/s10802-010-9434-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Goodman R, Scott S. Comparing the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire and the Child Behavior Checklist: Is small beautiful? J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1999;27(1):17–24. doi: 10.1023/a:1022658222914 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Davis EP, Stout SA, Molet J, Vegetabile B, Glynn LM, Sandman CA, et al. Exposure to unpredictable maternal sensory signals influences cognitive development across species. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 2017;114(39):10390–10395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1703444114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Glynn LM, Baram TZ. The influence of unpredictable, fragmented parental signals on the developing brain. Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 2019;53:100736. doi: 10.1016/j.yfrne.2019.01.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Glynn LM, Davis EP, Luby JL, Baram TZ, Sandman CA. A predictable home environment may protect child mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic. Neurobiol Stress. 2021;14:100291. doi: 10.1016/j.ynstr.2020.100291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Orben A. Teenagers, screens and social media: A narrative review of reviews and key studies. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol. 2020;55(4):407–14. doi: 10.1007/s00127-019-01825-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jensen M, George MJ, Russell MR, Odgers CL. Young adolescents’ digital technology use and mental health symptoms: Little evidence of longitudinal or daily linkages. Clin Psychol Sci. 2019;7(6):1416–33. doi: 10.1177/2167702619859336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.George MJ, Russell MA, Piontak JR, Odgers CL. Concurrent and subsequent associations between daily digital technology use and high-risk adolescents’ mental health symptoms. Child Dev. 2018;89(1):78–88. doi: 10.1111/cdev.12819 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Weems CF, Scott BG, Banks DM, Graham RA. Is TV traumatic for all youths? The role of preexisting posttraumatic-stress symptoms in the link between disaster coverage and stress. Psychol Sci. 2012;23(11):1293–7. doi: 10.1177/0956797612446952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.fefferbaum B, Nixon SJ, Tivis RD, Doughty DE, Pynoos RS, Gurwitch RH, et al. Television exposure in children after a terrorist incident. Psychiatry. 2001;64(3):202–11. doi: 10.1521/psyc.64.3.202.18462 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Comer JS, Kendall PC. Terrorism: The psychological impact on youth. Clin Psychol Sci Pract. 2007;14(3):179–212. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cobham VE, McDermott B, Haslam D, Sanders MR. The role of parents, parenting and the family environment in children’s post-disaster mental health. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2016;18(6):53. doi: 10.1007/s11920-016-0691-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.McCormick R. Does access to green space impact the mental well-being of children: A systematic review. J Pediatr Nurs. 2017;37:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.pedn.2017.08.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wells NM, Evans GW. Nearby nature: A buffer of life stress among rural children. Environ Behav. 2003;35(3):311–30. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Twenge JM, Hisler GC, Krizan Z. Associations between screen time and sleep duration are primarily driven by portable electronic devices: evidence from a population-based study of U.S. children ages 0–17. Sleep Med. 2019;56:211–218. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2018.11.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Van Roy B, Veenstra M, Clench-Aas J. Construct validity of the five-factor Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ) in pre-, early, and late adolescence. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Klasen H, Woerner W, Wolke D, Meyer R, Overmeyer S, Kaschnitz W, et al. Comparing the German versions of the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire (SDQ-Deu) and the Child Behavior Checklist. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;49(12):1304–1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.McLaughlin KA, Green JG, Alegría M, Jane Costello EJ, Gruber MJ, Sampson NA, et al. Food insecurity and mental disorders in a national sample of U.S. adolescents. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2012;51(12):1293–1303. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2012.09.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Blumberg SJ, Bialostosky K, Hamilton WL, Briefel RR. The effectiveness of a short form of the Household Food Security Scale. Am J Public Health. 1999;89(8):1231–4. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.8.1231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Paruthi S, Brooks LJ, D’Ambrosio C, Hall WA, Kotagal S, Lloyd RM, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for pediatric populations: A consensus statement of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2016;12(6):785–6. doi: 10.5664/jcsm.5866 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]