Abstract

Background

Recent evidence has shown that Solute Carrier Family 39 Member 10 (SLC39A10) promoted tumor progression in several cancer types. The study intended to explore the expression and function of SLC39A10 in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC).

Methods

Multiple bioinformatics analyses were used to evaluate SLC39A10 expression and potential role in HCC. Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction and immunohistochemistry were used to confirm SLC39A10 expression. Intro studies were performed to assess the effects of SLC39A10 on HCC cells proliferation and migration. Furthermore, flow cytometry was conducted to identify its specific function in apoptosis of HCC.

Results

SLC39A10 was significantly over-expressed in HCC samples from both bioinformatic databases and our cohort. Survival analyses suggested patients with high expression of SLC39A10 had poor overall survival and disease-free survival (P-value <0.01). Further, the expression of SLC39A10 was positively correlated with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and some immune checkpoints like CTLA4, TIM3 and TGFB1. In HCC cell lines, SLC39A10 knockdown inhibited cells proliferation and migration, but promoted apoptosis.

Conclusion

An increased SLC39A10 expression was found and served as an unfavorable indicator of survival in HCC. Further studies suggested SLC39A10 promotes tumor aggressiveness and may provide a novel target for HCC therapy.

Keywords: Solute Carrier Family 39 Member 10, hepatocellular carcinoma, immune infiltration, prognosis, cancer aggressiveness

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is a malignant tumor that ranks as the fourth leading cause of cancer-related death worldwide, being responsible for 781,631 deaths globally in 2018.1 The standard curative treatments for HCC are surgical resection, liver transplantation, and local ablation. Despite the enormous progress made in treatment approaches, the long-term survival for HCC patients remains unsatisfactory due primarily to the high rates of recurrence and metastasis.2,3 The 5-year survival rate of HCC patients in Asia is only 18.1%, lower than that in North America and Europe.4 Recent studies have provided novel insights into the biology and choice for personalized treatments of HCC.5 Tumor-specific cytotoxic T cells in HCC express immune checkpoint inhibitors, such as CTLA4, PD-L1, and TIM3, which prevent T cells from effectively recognizing tumor cells, leading to immune escape.6 The combination of bevacizumab and atezolizumab can improve median overall survival by more than 17 months and has been approved as the first-line therapy for HCC.7 Nevertheless, more than 75% of HCC patients show unsatisfactory responses to immunotherapies for reasons that remain unclear.8 Consequently, a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms involved in the regulation of HCC development and progression, as well as the associated immune microenvironment, is needed to help identify predictive biomarkers and improve survival for HCC patients.

Zinc, an important trace element, is indispensable for many cellular processes, including gene expression, immune functions, meiosis, cell-cycle progression, and apoptosis.9–11 Zinc has also been reported to play a key role as a second messenger in signaling pathways related to various physiological processes.12 Because of its involvement in cell apoptosis and proliferation, the role of zinc in cancer has long been the subject of investigation. Zinc distribution is tightly regulated through the activity of two zinc transporter families, namely, solute carrier family 39 (SLC39/ZIP), which functions in zinc influx into the cytoplasm, and solute carrier family 30 (SLC30/ZnT), which facilitates zinc efflux from the cytoplasm.13 Some SLC39 family members, such as SLC39A1 and SLC39A6, are reported to be involved in cancer development and progression.14,15 SLC39A10, one of the 14 known human SLC39 family members, can serve as a biomarker in several cancer types, including renal cell carcinoma (RCC), gastric cancer, and breast cancer.16–18 However, whether it also has a role in HCC is unknown.

In our study, we assessed SLC39A10 expression and its value in predicting survival for HCC patients. We further performed bioinformatics analysis and in vitro experiments to assess how SLC39A10 affects tumor cell behavior and identify the potential underlying mechanisms.

Methods

Data Acquisition

Gene expression data for 366 HCC samples were obtained from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) database up to April 2021 (https://portal.gdc.cancer.gov/repository). The GSE25097 dataset based on the GPL10687 platform (contains 289 liver and 268 HCC samples), the GSE36376 dataset based on the GPL10558 platform (contains 193 liver and 240 HCC samples), and the GSE45436 dataset based on the GPL570 platform (includes 65 liver and 69 HCC samples) were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database for expression validation (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis (GEPIA, http://gepia.cancer-pku.cn/index.html) and Oncomine (https://www.oncomine.org) were also used to validate the transcriptional level of SLC39A10 in HCC and normal liver tissues.19,20

Tissue Samples and Patient Follow-Up

For validation, tumor and adjacent normal tissue samples were obtained from 95 HCC patients at Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (GDPH cohort). All patients underwent surgical resection and were followed up until December 2020. Overall survival (OS) was defined as the date from surgical resection to death or last contact and disease-free survival (DFS) as the date from surgical resection to tumor metastasis or recurrence. The median follow-up time of patients from the GDPH cohort was 25.5 months (range, 16–78). The clinicopathologic information of the enrolled patients, including gender, age, hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg), tumor size, alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), TNM stage, and differentiation were manually collected. The study was approved by the Ethics Association of Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital and all the enrolled patients provided written informed consent before participation. Each tissue sample was evaluated and diagnosed as HCC by two different professional pathologists.

Cox Regression and Kaplan–Meier Survival Analysis

Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were used to identify independent prognostic factors for HCC prognosis in the GDPH cohort. Kaplan–Meier analyses and Log rank tests were conducted for the high- and low-SLC39A10 expression groups in both TCGA and GDPH cohorts to assess the ability to predict patient survival.

Functional and Pathway Enrichment Analysis

The GeneMANIA tool was used to analyze the relationship between SLC39A10 and its neighboring genes and construct a gene network map (http://genemania.org/).21 The STRING database was used to construct a protein–protein interaction (PPI) network for SLC39A10 (https://string-db.org/cgi/).22 Co-expressed genes (|Spearman correlation coefficient| >0.5 and P < 0.05) were screened from the cBioPortal database (https://www.cbioportal.org/) and then integrated into DAVID 6.7 for Gene Ontology (GO) and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analyses (https://david-d.ncifcrf.gov/). The results of the GO and KEGG analyses were visualized using the R “ggplot2” package. Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) was carried out to determine the gene sets and functional pathways that differed significantly between the high- and low-SLC39A10 expression groups. SLC39A10 expression was used as a phenotype label and 1000 gene set permutations were performed per analysis.

Immune Infiltration Analyses Through Multiple Datasets

The Tumor Immune Estimation Resource (TIMER; https://cistrome.shinyapps.io/timer/) webserver was first used to assess the relationship between SLC39A10 expression and infiltration levels of immune cells, including CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophils in HCC.23 Analyses of the correlation between SLC39A10 expression and gene markers of immune-infiltrating cells were conducted using Spearman correlation coefficients. The TISIDB database was subsequently used to identify putative correlations between SLC39A10 expression and immunostimulators or immunoinhibitors in HCC (http://cis.hku.hk/TISIDB).24

Cell Culture and Transfection

Normal human liver (LO2) and HCC (Hep3b, HUH7, PLC/PRE5, HepG2, LM3, and MHCC-97H) cell lines were obtained from Procell (Wuhan, China). Cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 medium (Gibco, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) at 37°C with 5% CO2. The vector for SLC39A10 knockdown was purchased from Obio Technology (Shanghai, China). The GV112 lentiviral vector was transfected into 293T cells using Helper 1.0 Packaging Plasmid Mix and virus particles were collected with lentivirus after 3 days. Precipitation was carried out according to the packaging scheme of System Biosciences. Cells were infected using Trans virus transduction reagent. The non-targeting (negative control, NC) plasmid was constructed with the following target sequence: GV112-NC-1CCGGTTCTCCGAACGTGTCACGTTTCAAGAGAACGTGACACGTTCGGAGAATTTTTG. cDNA for human SLC39A10 was cloned into the hU6-MCS-CMV-puro lentiviral vector and puromycin was used to screen for vector-positive cells.

Cell Proliferation Assays

Cell counting Kit-8 (CCK-8) and colony formation assays were used for the determination of cell viability. For CCK-8 assays, 1500 cells were seeded per well of 96-well plates. At a specific time point, CCK-8 solution was added to each well. The cells were then cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 and the absorbance (OD450) was assessed in a microplate reader after 0, 24, 48, and 72 h. For colony formation assays, cells of each cell type (2000 per well) were seeded into 6-well plates, gently shaken, and cultured at 37°C with 5% CO2 for 7–14 days. The medium was subsequently removed and the cells were stained with 0.1% crystal violet to quantify positive colonies (diameter >30 µm). All data represent means ± SD from independent experiments performed in triplicate.

Cell Migration Assays

Transwell plates (Corning Costar, USA) were used for cell migration analysis. A total of 5×104 cells were seeded in the upper chambers of transwell plates in 200 µL of serum-free Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM) while DMEM containing 10% FBS was added to the lower chambers. After incubating for 24 h, migrated cells in the lower chambers were fixed in methanol and then stained with crystal violet. Migrated cells were imaged using an inverted microscope and quantified from three different fields. Cell migration was also evaluated by wound-healing assay. Cells (1×106) were seeded into each well of a 6-well plate until 80–90% confluence. A sterile 200-µL pipette tip was then used to wound the cell monolayer, following which the cells were washed twice with phosphate buffer saline (PBS). Images of the wounds were obtained at 0 and 30 h using a photomicroscope and wound closure was evaluated in at least 3 different fields using ImageJ 1.52 (National Institute of Health, USA).

Flow Cytometry

Flow cytometry was performed as previously described.25

Immunohistochemistry

Paraffin-embedded HCC tissues were consecutively cut into 4-μm slices and then mounted on glass slides. The sections were dewaxed by soaking in dewaxing agent and 95% alcohol for 10 min and 5 min, respectively, and then washed three times with Tris-buffered saline (TBS). Antigen retrieval was performed in a high-pressure steam sterilizer (800–1200 W) using EDTA antigen-repair solution (pH 9.0). After soaking in TBS and H2O2 and blocking with 10% goat serum in TBS with Tween 20 (TBST) at 25°C for 30 min, the sections were incubated with a primary antibody (diluted 1:50) against SLC39A10 (ab83947; Abcam) overnight at 4°C. The following day, the sections were soaked three times in TBST at 25°C, incubated with an anti-rabbit secondary antibody at 37°C for 45 min, washed, stained with hematoxylin, and sealed with a sealing agent. After drying, the sections were examined and photographed under an Olympus BX63 microscope. SLC39A10 immunoreactivity was determined by staining intensity and distribution; less than 25% staining was considered low expression, while ≥25% staining was considered high expression. The specimens were assessed independently by two pathologists.

Real-Time Reverse Transcription Quantitative PCR (qPCR) and Western Blot

qPCR and Western blotting were performed as previously described.25 The following primer pairs were used for qPCR: SLC39A10 forward 5′-TTTCACTCACATAACCACCAGC-3′ and reverse 5′-GTGATGACGTAGGCGGTGATT-3′; BCL2 forward 5′-GGTGGGGTCATGTGTGTGG-3′ and reverse 5′-CGGTTCAGGTACTCAGTCATCC-3′; BIRC5 forward 5′-AGGACCACCGCATCTCTACAT-3′ and reverse 5′-AAGTCTGGCTCGTTCTCAGTG-3′. GAPDH (reference control) forward 5′-GGTGTGAACCATGAGAAGTATGA-3′ and reverse 5′-GAGTCCTTCCACGATACCAAAG-3′. The antibodies used for Western blotting (SLC39A10 [ab83947], BCL-2 [ab32124], survivin [ab76424], and GAPDH [ab8245]) were purchased from Abcam.

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were performed using R software version 4.0.1 (https://www.r-project.org/) and SPSS version 24.0 (SPSS, Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). A P-value <0.05 was considered statistically significant unless otherwise specified.

Results

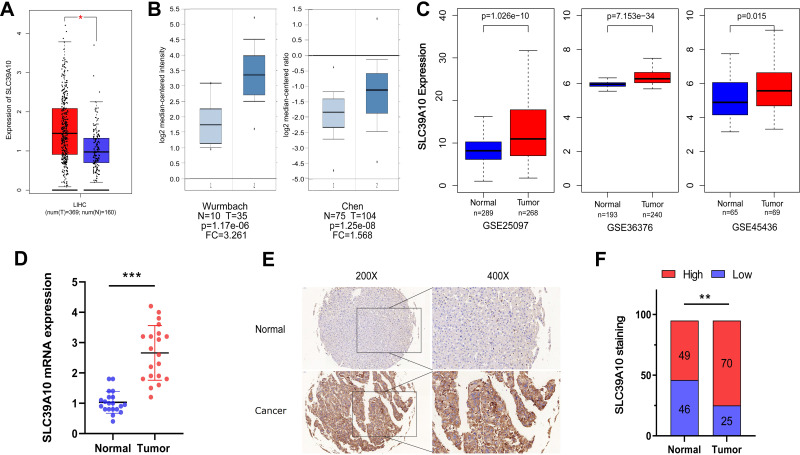

SLC39A10 is Highly Expressed in HCC

We first obtained gene expression data for SLC39A10 in HCC patient samples from public databases as well as the GDPH cohort to evaluate the role of SLC39A10 in HCC. Data acquired from the GEPIA database showed that SLC39A10 expression was higher in HCC samples than in normal liver samples (P < 0.05) (Figure 1A). Similar results were found in two datasets of the Oncomine database (Wurmbach’s and Chen’s datasets) and three GEO datasets (GSE25097, GSE36376, and GSE45436) (Figure 1B and C). qPCR analysis of 20 fresh HCC and adjacent normal liver tissue samples from the GDPH cohort indicated that SLC39A10 mRNA levels were higher in tumor tissues than in control tissues (Figure 1D). As expected, the immunohistochemistry (IHC) results also showed that patients with HCC displayed higher SLC39A10 expression levels than the controls (70 of the 95 HCC patients exhibited higher SLC39A10 expression while the other 25 exhibited lower SLC39A10 expression) (Figure 1E and F).

Figure 1.

SLC39A10 is over-expressed in Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC). (A) Over-expression of SLC39A10 in HCC was identified in GEPIA database. (B) Over-expression of SLC39A10 was identified in HCC in Oncomine database (Wurmbach’s Dataset and Chen’s Dataset). (C) Over-expression of SLC39A10 was identified in HCC in three individual GEO datasets (GSE25097, GSE36376 and GSE45436). (D) The mRNA over-expression levels of SLC39A10 were identified in HCC tissues and normal liver tissues of 20 samples. (E) Representative images of SLC39A10 staining in HCC specimens and normal liver tissues. (F) Immunohistochemistry staining showed SLC39A10 was upregulated in 70 out of 95 HCC tissues. All *P-value <0.05, **P-value <0.01, ***P-value <0.001.

Abbreviations: T, tumor; N, normal.

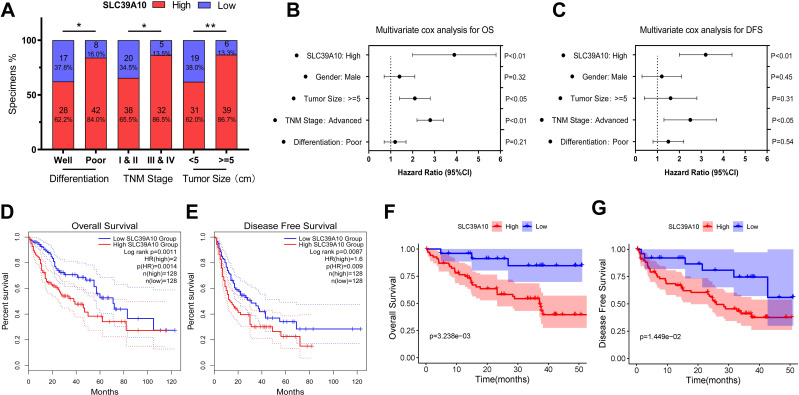

High SLC39A10 Expression Correlates with Unfavorable Clinical Characteristics and Poor Survival in HCC Patients

IHC staining was performed on 95 pairs of HCC and adjacent normal tissues to evaluate the clinical value of SLC39A10. The correlation between SLC39A10 expression and the clinicopathological characteristics of HCC patients is shown in Table 1 and Figure 2A. High SLC39A10 expression in HCC patients was significantly correlated with poor differentiation (P < 0.05), advanced TNM stage (P < 0.05), and larger tumor size (P = 0.01). Univariate and multivariate Cox regression analyses were then performed to confirm the prognostic significance of SLC39A10. The results indicated that high SLC39A10 expression was an independent risk factor for OS and DFS among the 95 HCC patients from the GDPH cohort (Tables 2 and 3 and Figure 2B and C). Additionally, Kaplan–Meier survival analyses for both TCGA and GDPH cohorts indicated that HCC patients with high SLC39A10 expression had inferior OS (P < 0.01) and DFS (P < 0.01) compared to those with low SLC39A10 expression (Figure 2D–G). These findings imply that SLC39A10 may be a potential indicator of HCC patient prognosis.

Table 1.

Correlation Between SLC39A10 Expression with Clinicopathological Characteristics of HCC Patients

| Clinicopathological Variables | Patients (n=95) | SLC39A10 Expression | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low (25) | High (70) | |||

| Gender | ||||

| Male | 83 | 20 | 63 | 0.29 |

| Female | 12 | 5 | 7 | |

| Age | ||||

| ≧50 | 45 | 11 | 34 | 0.87 |

| <50 | 50 | 14 | 36 | |

| AFP | ||||

| ≧200 ng/mL | 40 | 8 | 32 | 0.34 |

| <200 ng/mL | 55 | 17 | 38 | |

| HBsAg | ||||

| Positive | 34 | 6 | 28 | 0.23 |

| Negative | 61 | 19 | 42 | |

| Tumor size | ||||

| ≧5 cm | 50 | 19 | 31 | 0.01 |

| <5 cm | 45 | 6 | 39 | |

| TNM stage | ||||

| Advanced (III & IV) | 39 | 5 | 32 | <0.05 |

| Early (I & II) | 58 | 20 | 38 | |

| Differentiation | ||||

| Poor | 50 | 8 | 42 | <0.05 |

| Well | 45 | 17 | 28 | |

Figure 2.

Over-expression of SLC39A10 correlates with poor survival and unfavorable clinical characteristics in Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC). (A) SLC39A10 expression of HCC was significantly correlated with tumor size, TNM stage and differentiation. (B-C) Multivariate Cox regression analyses were performed to confirmed high expression of SLC39A10 was independent risk factor for overall survival (OS) (B) and disease-free survival (DFS) (C) of 95 HCC patients from GDPH cohort. (D and E) Kaplan-Meier analyses showed HCC patients with high expression of SLC39A10 had inferior OS (D) and DFS (E) than those with low expression in TCGA cohort. (F and G) Kaplan-Meier analyses showed HCC patients with high expression of SLC39A10 had inferior OS (F) and DFS (G) than those with low expression in GDPH cohort. All *P-value <0.05, **P-value <0.01.

Table 2.

Univariate and Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis of Risk Factors Associated with Overall Survival

| Clinicopathological Variables | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| SLC39A10 expression (High vs Low) | 8.02 | 5.39–8.32 | <0.01 | 3.89 | 1.95–5.83 | <0.01 |

| Gender (Male vs Female) | 2.02 | 1.23–2.81 | <0.05 | 1.42 | 0.69–2.85 | 0.32 |

| Age (≧50 vs <50) | 1.37 | 0.41–2.33 | 0.59 | |||

| AFP (≧200 ng/mL vs <200 ng/mL) | 1.48 | 0.94–2.02 | 0.07 | |||

| HBsAg (Positive vs Negative) | 1.21 | 0.63–1.79 | 0.30 | |||

| Tumor size (≧5 cm vs <5 cm) | 3.56 | 2.42–4.7 | <0.01 | 2.12 | 1.41–2.83 | <0.05 |

| TNM stage (Advanced vs Early) | 3.98 | 3.21–4.75 | <0.01 | 2.86 | 2.23–3.49 | <0.01 |

| Differentiation (Poor vs Well) | 1.98 | 1.21–2.75 | <0.05 | 1.19 | 0.70–1.68 | 0.21 |

Table 3.

Univariate and Multivariate Cox Regression Analysis of Risk Factors Associated with Disease-Free Survival

| Clinicopathological Variables | Univariate Analysis | Multivariate Analysis | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | |

| SLC39A10 expression (High vs Low) | 6.31 | 4.30–8.32 | <0.01 | 3.21 | 2.01–4.41 | <0.01 |

| Gender (Male vs Female) | 2.32 | 1.33–2.31 | <0.01 | 1.23 | 0.34–2.12 | 0.45 |

| Age (≧50 vs <50) | 1.06 | 0.25–1.87 | 0.63 | |||

| AFP (≧200 ng/mL vs <200 ng/mL) | 1.34 | 0.91–1.77 | 0.09 | |||

| HBsAg (Positive vs Negative) | 1.12 | 0.59–1.65 | 0.13 | |||

| Tumor size (≧5 cm vs <5 cm) | 3.21 | 2.35–4.07 | <0.01 | 1.65 | 0.48–2.82 | 0.31 |

| TNM stage (Advanced vs Early) | 4.34 | 2.98–5.70 | <0.01 | 2.52 | 1.32–3.72 | <0.05 |

| Differentiation (Poor vs Well) | 2.15 | 1.29–3.01 | <0.05 | 1.51 | 0.79–2.23 | 0.54 |

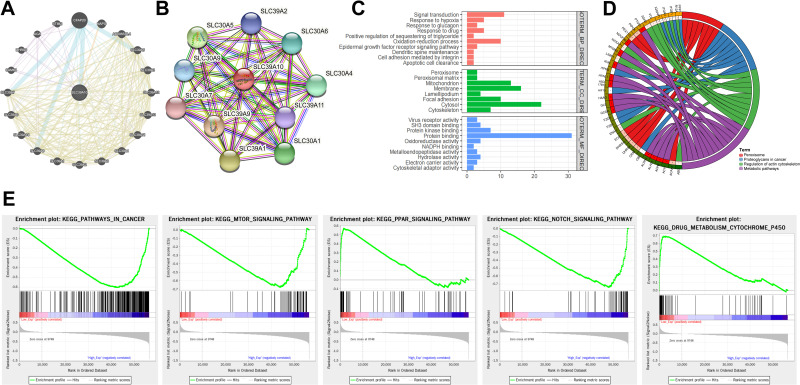

Neighbor Gene Network and Functional Enrichment Analysis of SLC39A10 in HCC

To explore the neighboring genes of SLC39A10, we first analyzed the relationships between these genes and built a gene network map using the GeneMANIA tool (Figure 3A). The central node (SLC39A10) was surrounded by 20 nodes representing genes with close correlations, including SLC39A1–14, CAMK4, DHRS9, AGA, STIM2, CFAP20, NAPG, and AC006538.4. Using STRING tools, we constructed a PPI network for SLC39A10 (Figure 3B) and found that SLC39A10 was connected with SLC39A2, SLC39A9, SLC39A11, SLC30A1, SLC30A4–7, and SLC30A9.

Figure 3.

Neighbor gene network and functional enrichment analyses of SLC39A10 in Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC). (A) GeneMANIA tool was used to show the relationships of neighbor genes of SLC39A10 and construct a network map. (B) STRING tool was used to construct a protein-protein interaction network (PPI) of SLC39A10. (C) Gene Ontology (GO) enrichment analysis of SLC39A10. (D) Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathway analysis of SLC39A10. (E) Gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) of SLC39A10.

We subsequently analyzed the potential biological pathways associated with SLC39A10 to evaluate its molecular function in HCC. A total of 89 co-expressed genes were identified using the cBioPortal dataset, and these were then enrolled into DAVID 6.7 and subjected to GO and KEGG analyses. In GO analysis, SLC39A10 and its neighboring genes were mainly enriched in “signal transduction, response to hypoxia, glucagon and drug, epidermal growth factor receptor signaling pathway, oxidation-reduction process, cell adhesion mediated by integrin, apoptotic cell clearance, peroxisome, mitochondrion, membrane, focal adhesion, cytoskeleton, SH3 domain binding, protein binding, protein kinase binding, and cytoskeletal adaptor activity” (Figure 3C).

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis showed that SLC39A10 may be involved in “Peroxisome, Proteoglycans in cancer, Regulation of actin cytoskeleton, and Metabolic pathways” (Figure 3D). GSEA was also performed to identify the differentially enriched gene sets and pathways between HCC samples with high and low SLC39A10 expression. The top 5 significantly enriched biological processes were found to include ‘Pathways in cancer, mTOR signal pathway, PPAR signal pathway, NOTCH signal pathway, and Drug metabolism - cytochrome P450ʹ (Figure 3E). These results suggested that SLC39A10 may be involved in promoting HCC tumorigenesis and progression via several signaling pathways.

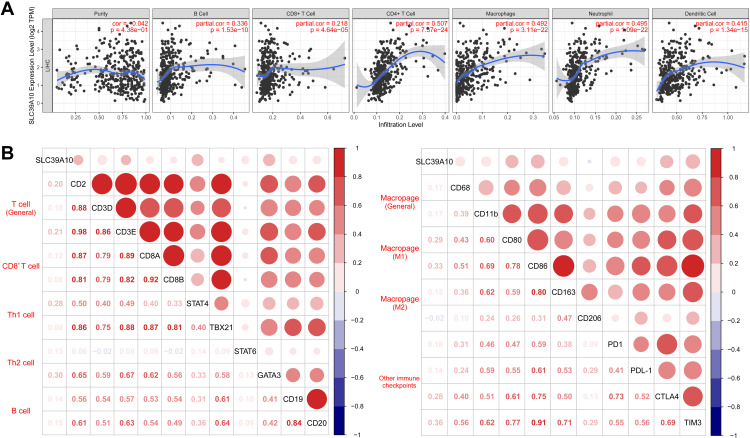

The Association Between Immune Infiltration and SLC39A10 Expression in HCC

Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs), especially CD8+ T cells, are highly correlated with HCC tumorigenesis and progression.26 Here, we evaluated the correlation between SLC39A10 expression and TILs, including CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophils in HCC using the TIMER web server (Figure 4A). After quality control, the results showed that SLC39A10 expression was positively correlated with the abundance of B cells (coefficient = 0.336, P = 1.53e-10), CD8+ T cells (coefficient = 0.218, P = 4.64e-05), CD4+ T cells (coefficient = 0.507, P = 7.37e-24), macrophages (coefficient = 0.492, P = 3.11e-22), neutrophils (coefficient = 0.495, P = 1.09e-22), and dendritic cells (coefficient = 0.415, P = 1.34e-15). In addition, SLC39A10 expression showed positive correlations with gene markers for T cells (CD2 and CD3E), Th1 cells (STAT4), Th2 cells (GATA3), M1 macrophages (CD80 and CD86), and other immune checkpoint markers such as CTLA4 and TIM3 (Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Correlations of SLC39A10 expression with tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) in Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC). (A) Correlations between SLC39A10 expression and TILs shown by Timer web server. (B) Correlations between SLC39A10 expression and gene markers from TILs and other immune checkpoints.

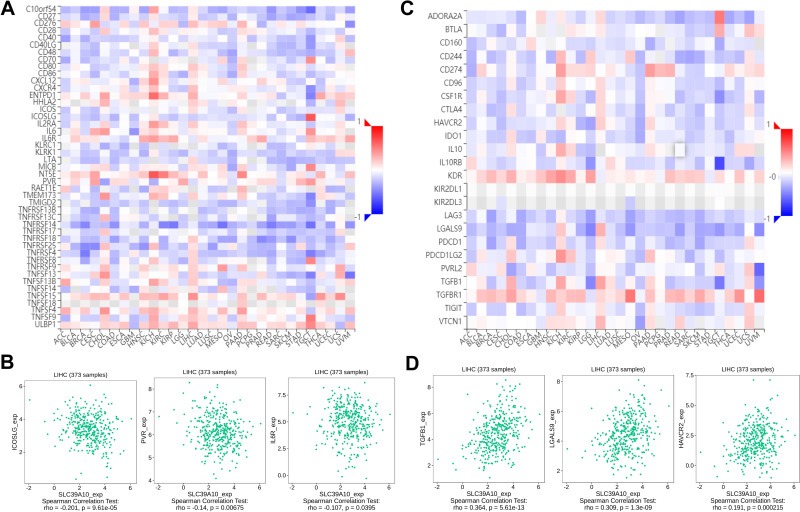

To further explore the role of SLC39A10 in immune regulation, we next determined Spearman correlation coefficients for the association between SLC39A10 and immunostimulators or immunoinhibitors using the TISIDB database (Figure 5A and B). For immunostimulators, SLC39A10 was most negatively correlated with ICOSLG (coefficient = −0.201, P = 9.61e-05), PVR (coefficient = −0.14, P = 6.75e-03), and ENTPD1 (coefficient = −0.107, P = 0.0395) (Figure 5C). For immunoinhibitors, SLC39A10 was most positively correlated with TGFB1 (coefficient = 0.364, P = 5.61e-13), LGALS9 (coefficient = 0.309, P = 1.3e-09), and HAVCR2 (coefficient = 0.191, P = 2.15e-04) (Figure 5D). Combined, these results indicated that SLC39A10 may be involved in mediating tumor-specific immune responses via the regulation of TILs and several immune-related molecules.

Figure 5.

Correlations of SLC39A10 with immunomodulators in Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC). (A) Correlations between immunostimulators and SLC39A10 expression shown by TISIDB database. (B) Top 3 immunostimulators with greatest negative Spearman correlation with SLC39A10. (C) Correlations between immunoinhibitors and SLC39A10 expression shown by TISIDB database. (D) Top 3 immunoinhibitors with greatest positive Spearman correlation with SLC39A10.

SLC39A10 Promotes HCC Cell Proliferation and Migration

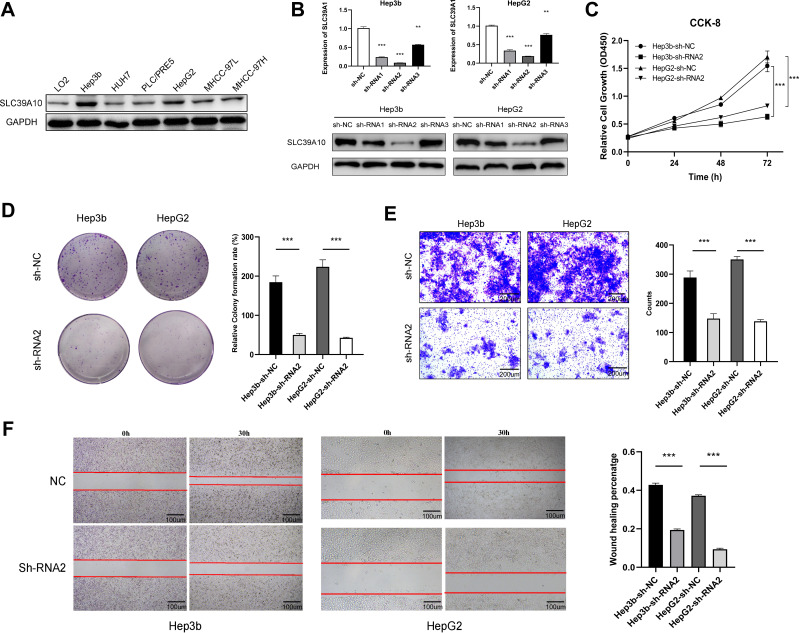

SLC39A10 expression was evaluated in several HCC cell lines, with the results suggesting that it was relatively highly expressed in Hep3b and HepG2 cells (Figure 6A). Three sh-SLC39A10 constructs were transfected into Hep3b and HepG2 cells to assess the effect of SLC39A10 on HCC cell proliferation and migration. qPCR results validated the efficiency of SLC39A10 knockdown in these two cell lines, especially that for Hep3b-sh-RNA2 and HepG2-sh-RNA2 (P < 0.001) (Figure 6B). CCK-8 and colony formation assays both showed that, compared with the NCs, the knockdown of SLC39A10 significantly inhibited tumor cell proliferation in both Hep3b and HepG2 cells (P < 0.001) (Figure 6C and D). Additionally, the results of the transwell and wound-healing assays demonstrated that the migratory ability of HCC cells was suppressed with the silencing of SLC39A10 (P < 0.001) (Figure 6E and F).

Figure 6.

SLC39A10 promotes the proliferation and migration of Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) cells. (A) Western blot showed SLC39A10 was highly expressed in Hep3b and HepG2 cells among HCC cell lines. (B) Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction and Western blot were used to detect the down-regulation of SLC39A10 in Hep3b and HepG2 cells transfection with three SLC39A10-shRNA. (C and D) CCK-8 assay (C) and colony formation assay (D) showed that SLC39A10 knockdown reduced the proliferation in Hep3b and HepG2 cells. (E and F) Transwell assay (E) and wound-healing assay (F) showed that SLC39A10 knockdown reduced the migration in Hep3b and HepG2 cells. All **P-value <0.01, ***P-value <0.001.

SLC39A10 Knockdown Promotes the Apoptosis of HCC Cells

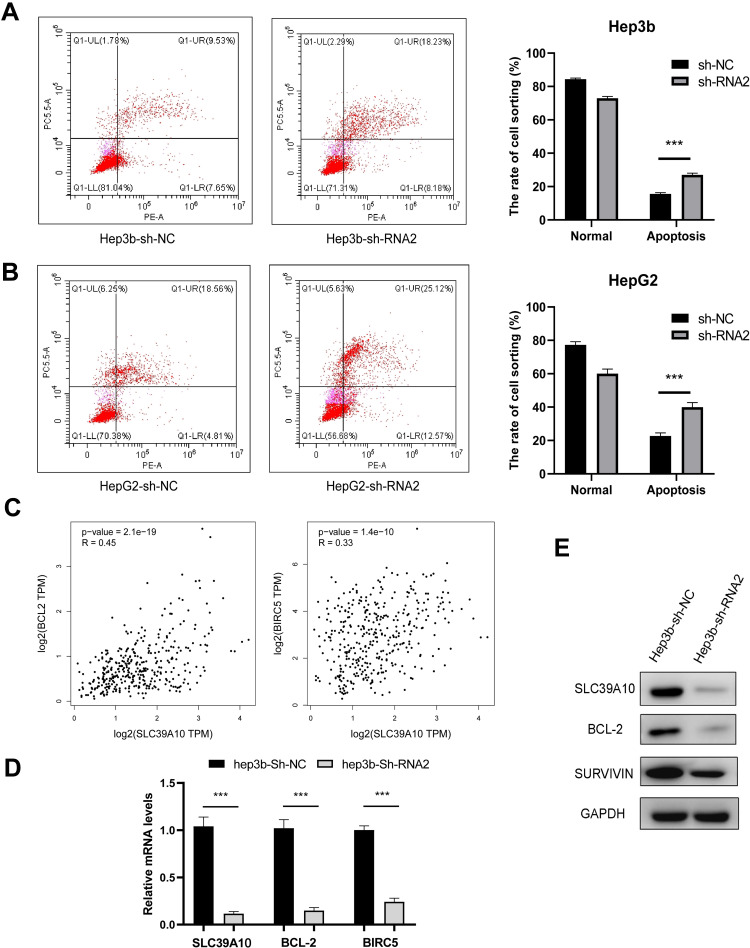

As our GO analysis suggested that SLC39A10 may be enriched in “Apoptotic cell clearance”, we, therefore, undertook a flow cytometric analysis to determine the specific role of SLC39A10 in HCC cell apoptosis. We found that, compared with controls, the knockdown of SLC39A10 increased the percentage of apoptotic Hep3b and HepG2 cells (Figure 7A and B). The results further showed that SLC39A10 expression was positively correlated BCL2 (coefficient = 0.45, P = 2.1e-19) and BIRC5 (coefficient = 0.33, P = 1.4e-10) based on GEPIA data (Figure 7C). The qPCR and Western blot results confirmed that the mRNA and protein expression levels of BCL2 and BIRC5 (survivin) were downregulated in sh-SLC39A10-expressing Hep3b cells (Figure 7D and E). These results indicated that SLC39A10 can promote resistance to apoptosis in HCC by upregulating BCL2 and BIRC5 expression levels.

Figure 7.

Knockdown of SLC39A10 promotes apoptosis of Hepatocellular Carcinoma (HCC) cells. (A and B) Flow cytometry showed that knockdown of SLC39A10 increased the percentage of apoptotic Hep3b (A) and HepG2 (B) cells. (C) Correlations of SLC39A10 expression and BCL2, BIRC5 shown by GEPIA web server. (D and E) Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (D) and Western blot (E) validated the expression of BCL2 and BIRC5 (Survivin) was down-regulated in sh-SLC39A10 Hep3b cell. All ***P-value <0.001.

Discussion

Finding novel effective biomarkers for HCC initiation and progression is of great value for identifying novel therapeutic targets. Studies have shown that zinc distribution is correlated with the tumorigenesis and progression of several cancers, including hepatocarcinoma.27 Various zinc transporters in the SLC39A family have been found to mediate the dysregulated zinc distribution seen in cancers and to be involved in cancer metastasis, such as the lymph node metastasis of breast cancers.28–30 SLC39A10, a member of the SLC39A family, is a major zinc transporter involved in zinc influx and serves as a biomarker in several cancer types.16–18 Studies have shown that SLC39A10 overexpression promotes migration and invasion in breast cancer cells and is associated with the expression levels of the estrogen receptor, ERBB3, and STAT3 in breast cancer.16,31 Additionally, SLC39A10 expression was reported to be significantly upregulated in RCC, especially in high-grade tumors.17 However, whether SLC39A10 plays a role in HCC and whether it may serve as a prognostic marker for this malignancy was not known.

In the present study, we noted that SLC39A10 was highly expressed in HCC tissues both in our GDPH cohort and as determined from data available in public databases. High SLC39A10 expression was positively correlated with advanced TNM stage, poor differentiation, and large tumor size, indicating that SLC39A10 may have prognostic value in HCC. Kaplan–Meier analyses also suggested that patients with high SLC39A10 expression had poor survival. Studies have shown that SLC39A10 serves as a positive regulator of CD45R in B-cell antigen receptor signaling transduction, thereby setting a threshold in human immune responses.32 Downstream of the JAK/STAT signaling pathway, SLC39A10 mediates zinc homeostasis for early B-cell survival, thereby affecting humoral immune system maintenance.33 Using multiple tools, we explored the relationship between SLC39A10 expression and the levels of immune cell infiltration in HCC. The results showed that SLC39A10 expression was positively correlated with the abundance of TILs, including CD8+ T cells, CD4+ T cells, B cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, and neutrophils. However, SLC39A10 expression was also found to be positively correlated with immune checkpoint molecules such as CTLA4, TIM3, and TGFB1. Immune evasion is a hallmark of most cancers, including HCC, and is widely studied as an important therapeutic target.34 Immune checkpoint factors, including CTLA-4, PD-1/PD-L1, TIM3, and TGFB1, serve as immunosuppressors that inhibit the activities of TILs, such as natural killer cells and CD8+ T cells, thereby promoting immune evasion in HCC.35–37 These results indicate that, although high TIL infiltration levels were found in the high-SLC39A10-expression group, SLC39A10 upregulation may simultaneously lead to increased expression of other immune checkpoint factors such as CTLA4, TIM3, and TGFB1, which consequently promote immune evasion in the HCC microenvironment. Further studies are needed to determine the relationship between SLC39A10 and TILs in the HCC immune microenvironment as well as the underlying mechanism.

We constructed neighbor gene and PPI networks for SLC39A10 and identified neighbor genes that may play vital roles in cancer progression in combination with SLC39A10. This included STIM1, an important sensor molecule involved in the regulation of cytosolic Ca2+ levels in the maintenance of B-cell functions.38 Our findings also revealed that SLC39A10 expression was positively correlated with the abundance of B cells and other immune checkpoint factors in HCC. Additional studies are needed to reveal their role in B-cell function or the tumor immune microenvironment. GO and KEGG functional enrichment analyses suggested that SLC39A10 was mainly associated with “Cell adhesion, Apoptotic cell clearance, Focal adhesion, Cytoskeleton, SH3 domain binding, Protein binding, Protein kinase binding, Cytoskeletal adaptor activity, and Regulation of actin cytoskeleton”. GSEA analysis also showed that SLC39A10 was highly associated with “Pathways in cancer, mTOR signal pathway, PPAR signal pathway, NOTCH signaling pathway, and Drug metabolism - cytochrome P450”. Given our initial findings, we further evaluated the effects of SLC39A10 on the proliferative and migratory ability of HCC cells. Consistent with the results of previous studies,16,31 the knockdown of SLC39A10 significantly inhibited proliferation and migration in two HCC cell lines. SLC39A10 may play an antiapoptotic role in coordination with BCL members and is a critical inhibitor of caspase-mediated apoptosis.33 Driven by STAT3, SLC39A10 was also found to interact with SLC39A6 to initiate cell rounding and import zinc into cells to initiate mitosis.39 In the current study, flow cytometry results demonstrated that SLC39A10 knockdown promoted the apoptosis of HCC cells. Furthermore, the mRNA and protein expression of two important apoptosis inhibitors, BCL-2 and BIRC5/survivin, were proportionally reduced in HCC SLC39A10-knockdown cells. These observations suggest that SLC39A10 may promote resistance to apoptosis in combination with BCL-2 and BIRC5.

This is the first study to evaluate and report the expression and effects of SLC39A10 in HCC. However, our study had several limitations. For example, although our results indicated that SLC39A10 may serve as a prognostic biomarker for HCC, further in vivo experiments and prospective studies are needed to validate our results and further reveal the underlying molecular mechanisms.

Conclusion

In summary, we found that high SLC39A10 expression is an unfavorable indicator of HCC prognosis. In vitro studies suggested that SLC39A10 is involved in the regulation of HCC cell proliferation, migration, and apoptosis. Overall, our study has provided novel ideas concerning the mechanisms underlying HCC tumorigenesis and progression, and identified a potential biomarker for HCC prognosis, as well as a potential therapeutic target for HCC treatment.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Special Funding from Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital (2020bq09, 8200100290, KY012021164), Collaborative Funding of Basic and Applied Basis Research Funding of Guangdong Province (2020A1515110536), Basic and applied basic research funding of Guangdong Province (2021A1515011473, 2021A1515012441, and 2021A1515011577), the Science and Technology Program of Guangzhou (202102020030, 202102020107), the Science and Technology Program of Huizhou (2019C0602009), the Science and Technology Program of Huizhou Daya Bay (2020030401), Funding for the Construction of Key Specialty in Huizhou (Qi Zhou), National Natural Science Foundation of China (82072635, 82072637 and 81672475). Zuyi Ma, Zhenchong Li, Shujie Wang, and Qi Zhou are co-first authors for this study.

Abbreviations

HCC, Hepatocellular carcinoma; SLC39A10, Solute Carrier Family 39 Member 10; RCC, renal cell carcinoma; FPKM, Fragments Per Kilobase per Million; TCGA, the Cancer Genome Atlas; GEO, Gene Expression Omnibus; GEPIA, Gene Expression Profiling Interactive Analysis; GPPH, Guangdong Provincial People’s Hospital; OS, Overall survival; DFS, Disease-free survival; AFP, alpha fetoprotein; HBsAg, Hepatitis B surface antigen; PPI, protein protein interaction network; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; GSEA, Gene set enrichment analysis; ATCC, American Type Culture Collection; CCK-8, Cell counting Kit-8 assay; FBS, Fetal Bovine Serum; DMEM, dulbecco’s modified eagle medium; PBS, phosphate buffer saline.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Ko KL, Mak LY, Cheung KS, Yuen MF. Hepatocellular carcinoma: recent advances and emerging medical therapies. F1000Res. 2020;9:620. doi: 10.12688/f1000research.24543.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu J, Zhang XP, Zhong BY, et al. Management of patients with hepatocellular carcinoma and portal vein tumour thrombosis: comparing east and west. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;4(9):721–730. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(19)30178-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer T. Treatment of advanced hepatocellular carcinoma: beyond sorafenib. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(4):218–220. doi: 10.1016/S2468-1253(17)30255-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hassanipour S, Vali M, Gaffari-Fam S, et al. The survival rate of hepatocellular carcinoma in Asian countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Excli J. 2020;19:108–130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Faivre S, Rimassa L, Finn RS. Molecular therapies for HCC: looking outside the box. J Hepatol. 2020;72(2):342–352. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2019.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ruf B, Heinrich B, Greten TF. Immunobiology and immunotherapy of HCC: spotlight on innate and innate-like immune cells. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18(1):112–127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finn RS, Qin S, Ikeda M, et al. Atezolizumab plus bevacizumab in unresectable hepatocellular carcinoma. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(20):1894–1905. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1915745 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Giraud J, Chalopin D, Blanc J-F, Saleh M. Hepatocellular carcinoma immune landscape and the potential of immunotherapies. Front Immunol. 2021;12:655697. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.655697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Que EL, Bleher R, Duncan FE, et al. Quantitative mapping of zinc fluxes in the mammalian egg reveals the origin of fertilization-induced zinc sparks. Nat Chem. 2015;7(2):130–139. doi: 10.1038/nchem.2133 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haase H, Rink L. Multiple impacts of zinc on immune function. Metallomics. 2014;6(7):1175–1180. doi: 10.1039/c3mt00353a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li Y, Maret W. Transient fluctuations of intracellular zinc ions in cell proliferation. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315(14):2463–2470. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2009.05.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fukada T, Yamasaki S, Nishida K, Murakami M, Hirano T. Zinc homeostasis and signaling in health and diseases: zinc signaling. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2011;16(7):1123–1134. doi: 10.1007/s00775-011-0797-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Eide DJ. Zinc transporters and the cellular trafficking of zinc. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763(7):711–722. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.03.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Franklin RB, Feng P, Milon B, et al. hZIP1 zinc uptake transporter down regulation and zinc depletion in prostate cancer. Mol Cancer. 2005;4:32. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-4-32 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Taylor KM, Morgan HE, Smart K, et al. The emerging role of the LIV-1 subfamily of zinc transporters in breast cancer. Mol Med. 2007;13(7–8):396–406. doi: 10.2119/2007-00040.Taylor [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kagara N, Tanaka N, Noguchi S, Hirano T. Zinc and its transporter ZIP10 are involved in invasive behavior of breast cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 2007;98(5):692–697. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2007.00446.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pal D, Sharma U, Singh SK, Prasad R. Association between ZIP10 gene expression and tumor aggressiveness in renal cell carcinoma. Gene. 2014;552(1):195–198. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2014.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ding B, Lou W, Xu L, Li R, Fan W. Analysis the prognostic values of solute carrier (SLC) family 39 genes in gastric cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2019;11(1):486–498. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rhodes DR, Yu J, Shanker K, et al. ONCOMINE: a cancer microarray database and integrated data-mining platform. Neoplasia. 2004;6(1):1–6. doi: 10.1016/S1476-5586(04)80047-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tang Z, Li C, Kang B, Gao G, Li C, Zhang Z. GEPIA: a web server for cancer and normal gene expression profiling and interactive analyses. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017;45(W1):W98–W102. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx247 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mostafavi S, Ray D, Warde-Farley D, Grouios C, Morris Q. GeneMANIA: a real-time multiple association network integration algorithm for predicting gene function. Genome Biol. 2008;9(Suppl 1):S4. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-s1-s4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.von Mering C, Jensen LJ, Snel B, et al. STRING: known and predicted protein-protein associations, integrated and transferred across organisms. Nucleic Acids Res. 2005;33:D433–D437. doi: 10.1093/nar/gki005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li T, Fan J, Wang B, et al. TIMER: a web server for comprehensive analysis of tumor-infiltrating immune cells. Cancer Res. 2017;77(21):e108–e110. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-0307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ru B, Wong CN, Tong Y, et al. TISIDB: an integrated repository portal for tumor-immune system interactions. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(20):4200–4202. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang S, Zhang C, Sun C, et al. Obg-like ATPase 1 (OLA1) overexpression predicts poor prognosis and promotes tumor progression by regulating P21/CDK2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Aging. 2020;12(3):3025–3041. doi: 10.18632/aging.102797 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Federico P, Petrillo A, Giordano P, et al. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in hepatocellular carcinoma: current status and novel perspectives. Cancers. 2020;12(10):3025. doi: 10.3390/cancers12103025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tashiro H, Kawamoto T, Okubo T, Koide O. Variation in the distribution of trace elements in hepatoma. Biol Trace Elem Res. 2003;95(1):49–63. doi: 10.1385/BTER:95:1:49 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Barresi V, Valenti G, Spampinato G, et al. Transcriptome analysis reveals an altered expression profile of zinc transporters in colorectal cancer. J Cell Biochem. 2018;119(12):9707–9719. doi: 10.1002/jcb.27285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wu DM, Liu T, Deng SH, Han R, Xu Y. SLC39A4 expression is associated with enhanced cell migration, cisplatin resistance, and poor survival in non-small cell lung cancer. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):7211. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-07830-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Taylor KM, Vichova P, Jordan N, Hiscox S, Hendley R, Nicholson RI. ZIP7-mediated intracellular zinc transport contributes to aberrant growth factor signaling in antihormone-resistant breast cancer cells. Endocrinology. 2008;149(10):4912–4920. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-0351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takatani-Nakase T, Matsui C, Maeda S, Kawahara S, Takahashi K. High glucose level promotes migration behavior of breast cancer cells through zinc and its transporters. PLoS One. 2014;9(2):e90136. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hojyo S, Miyai T, Fujishiro H, et al. Zinc transporter SLC39A10/ZIP10 controls humoral immunity by modulating B-cell receptor signal strength. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(32):11786–11791. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323557111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyai T, Hojyo S, Ikawa T, et al. Zinc transporter SLC39A10/ZIP10 facilitates antiapoptotic signaling during early B-cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(32):11780–11785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1323549111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fu Y, Liu S, Zeng S, Shen H. From bench to bed: the tumor immune microenvironment and current immunotherapeutic strategies for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):396. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1396-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liu Z, Lin Y, Zhang J, et al. Molecular targeted and immune checkpoint therapy for advanced hepatocellular carcinoma. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38(1):447. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1412-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Katz LH, Likhter M, Jogunoori W, Belkin M, Ohshiro K, Mishra L. TGF-β signaling in liver and gastrointestinal cancers. Cancer Lett. 2016;379(2):166–172. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2016.03.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ihling C, Naughton B, Zhang Y, et al. Observational study of PD-L1, TGF-β, and immune cell infiltrates in hepatocellular carcinoma. Front Med. 2019;6:15. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2019.00015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Baba Y, Matsumoto M, Kurosaki T. Calcium signaling in B cells: regulation of cytosolic Ca2+ increase and its sensor molecules, STIM1 and STIM2. Mol Immunol. 2014;62(2):339–343. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nimmanon T, Ziliotto S, Ogle O, et al. The ZIP6/ZIP10 heteromer is essential for the zinc-mediated trigger of mitosis. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2021;78(4):1781–1798. doi: 10.1007/s00018-020-03616-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]