Abstract

According to cultural betrayal trauma theory, within-group violence confers a cultural betrayal that contributes to outcomes, including symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSS). Close relationship with the perpetrator, known as high betrayal, also impacts PTSS. The purpose of the current study is to examine cultural betrayal trauma, high betrayal trauma, and PTSS in a sample of diverse ethnic minority emerging adults. Participants (N = 296) completed the one-hour questionnaire online. Hierarchical linear regression analyses revealed that when controlling for gender, ethnicity, and interracial trauma, high betrayal trauma and cultural betrayal trauma were associated with PTSS. Clinical interventions can include assessments of the relationship with and in-group status of the perpetrator(s) in order to guide treatment planning with diverse survivors.

Keywords: PTSD, Abuse, Cultural betrayal trauma theory, Ethnic minorities, Emerging adulthood

In the U.S., some ethnic minority populations, including Black/African Americans and Latino Americans, are at increased risk for victimization (e.g., National Center for Victims of Crime 2012; Porter and McQuiller Williams 2011; Rape and Network 2016). Such increased risk is problematic, given that violence victimization is linked with a host of mental health outcomes, including symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder, such as hypervigilance, avoidance, and flashbacks (PTSS; Ford and Gómez 2015; Gómez et al. 2018; Kelley et al. 2012; Klest et al. 2013; Lilly and Valdez 2012; Littleton and Ullman 2013; Ullman 2007; Ullman and Filipas, 2005). However, additional factors within victimization have been shown to impact outcomes. For instance, according to betrayal trauma theory (Freyd 1997), a close relationship with the perpetrator(s) contributes to mental health problems. Of relevance for ethnic minority populations, theoretical and empirical work has documented the importance of including contextual factors, such as discrimination and minority status, in violence research (Briere and Scott 2006; Burstow 2003; Christopher 2004; Cohen et al. 2001; Harvey 2007; Korbin 2002; Pole and Triffleman 2010). Nevertheless, such aspects are often excluded in research. Consequently, there may be gaps in understanding the harm of violence in ethnic minority populations. Cultural betrayal trauma theory (CBTT; Gómez 2012, 2017a, 2017b, 2019a, 2019b, 2019c, 2019d; Gómez and Freyd 2018; Gómez and Gobin 2020) was developed in an effort to better understand violence sequelae in minority populations, which are groups that are marginalized due to one or more identities, such as gender and race. With betrayal trauma theory and CBTT as the theoretical foundations, the purpose of the current study is to assess the independent and joint roles of the relationship with the perpetrator (high betrayal) and the in-group identity of the perpetrator (cultural betrayal) on PTSS among ethnic minority emerging adults.

Violence Victimization

In the U.S., exposure to violence, including physical, sexual, and emotional abuse, is relatively common. Prevalence rates range from about 25% to 60%, with over half of the general population experiencing physical abuse (Kilpatrick and Acierno 2003), about one-third experiencing sexual abuse, and approximately 40% being exposed to emotional abuse (Black et al. 2011). Moreover, Black/African American, Latino American, and “other”, as categorized by the U.S. Department of Justice, are at increased for victimization (Morgan and Truman 2018), with some studies suggesting that rates range from 35% to 54% for within-group violence victimization specifically within Asian American, Black/African American, and Latino American emerging adults (Gómez 2017a, 2017b, 2019a). Youth who are transitioning into adulthood are particularly susceptible to both exposure to violence (Porter and McQuiller Williams 2011) and mental health problems, including PTSS (e.g., Hunt and Eisenberg 2010).

Betrayal Trauma Theory

With betrayal trauma theory, Freyd (1996) identified the relationship, such as that between parent and child, as a site where abusive interactions were indicative of a high betrayal. This high betrayal trauma is contrasted with medium betrayal trauma, which are perpetrated by strangers or others who are not close to the victim. As such, Freyd (1997) posited that abuse in close relationships was a traumatic betrayal, as it violates the victim’s trust and/or dependence on the perpetrator. Consequently, according to betrayal trauma theory (Freyd 1996), this traumatic betrayal is harmful and negatively impacts outcomes. Research on betrayal trauma theory has supported the theoretical assumption that high betrayal contributes to mental health outcomes, such as PTSD, dissociation, and borderline personality characteristics. (Brown and Freyd 2008; DePrince et al. 2012; Gobin and Freyd 2009; Goldberg and Freyd 2006; Goldsmith et al. 2012; Gómez 2018; Gómez et al. 2014a; Gómez and Freyd 2017; Gómez and Freyd 2018; Kaehler and Freyd 2009; Kelley et al. 2012). Additional contextual factors, including inequality, may also impact trauma-related mental health.

Ethnic Minority Trauma Psychology

Just as Freyd (1997) contextualized the harm of trauma within interpersonal relationships, other work has detailed how the broader context of inequality can impact the mental and behavioral health outcomes of trauma, such as depression and reduced disclosure (e.g., Brown 2008; Bryant-Davis 2005). This work elucidates the need for aspects of the sociocultural context, such as societal trauma in the form of systemic oppression, to be included in violence work, as such factors can affect violence-related mental health within ethnic minority populations (Brown 2008; Bryant-Davis 2005; Bryant-Davis 2010; Bryant-Davis et al. 2009; Burstow 2003, 2005; Harvey and Tummalanarra 2007; Tyagi 2002). Additionally, research that compares ethnic minorities with Whites may result in invidious group comparisons that promote biological essentialism while deemphasizing the importance of context (Cole and Stewart 2001). Moreover, conceptualizing White American populations as the epicenter of psychological phenomena limits what can be discovered and known about human behavior and processes (Henrich et al. 2010). Therefore, research within ethnic minority populations specifically is warranted.

Cultural Betrayal Trauma Theory (CBTT)

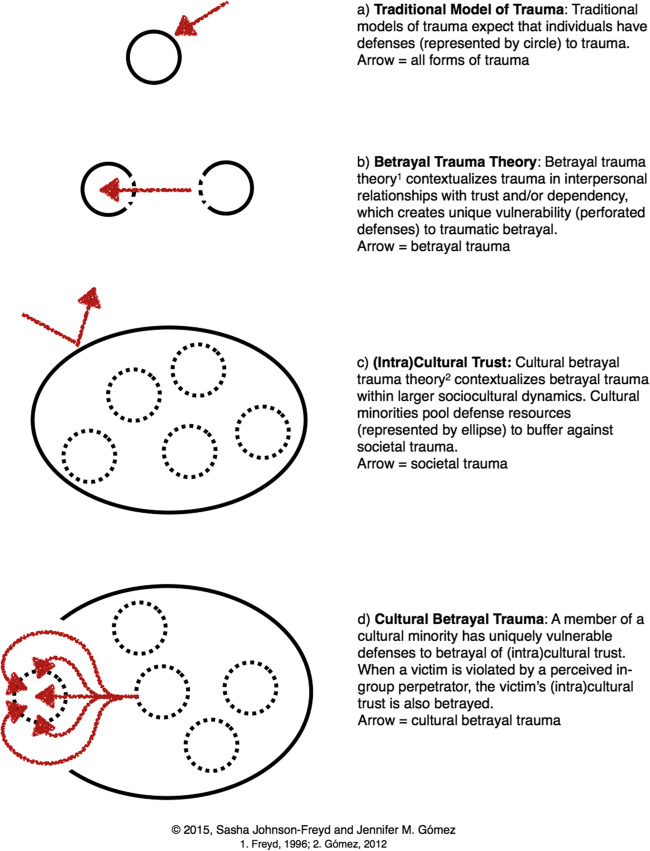

The creation of CBTT (Gómez 2012) was influenced by trauma work based in ethnic minority trauma psychology (e.g., Brown 2008; Bryant-Davis 2005) and within the dominant culture (Freyd 1996, 1997). Gómez (2012) proposed CBTT. In doing so, CBTT expands the concept of betrayal in trauma into the sociocultural context for ethnic and other minority populations. According to CBTT, societal trauma, such as discrimination based on minority status, creates the need for (intra)cultural trust, which is attachment and connection with other minorities (e.g., Gómez 2019d; Gómez and Freyd 2019; Gómez and Gobin 2020). (Intra)cultural trust is distinct from, but analogous to, interpersonal trust in close relationships. Like in close relationships, (intra)cultural trust can elicit attachment, love, loyalty, and responsibility with other members of the minority group. Therefore, similar to close relationships, vulnerability to harm comes with (intra)cultural trust. Importantly, (intra)cultural trust would not exist or be necessary without societal trauma. For ethnic minorities, one form of societal trauma is racism. Within-group violence, such as intra-racial trauma, is a violation of this (intra)cultural trust, which Gómez (e.g., 2019c) defined as a cultural betrayal. As such, within-group violence in minority populations are conceptualized as cultural betrayal traumas (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Traditional Model of Trauma, Betrayal Trauma Theory, Societal Trauma, & Cultural Betrayal Trauma, reprinted with permission

A burgeoning evidence base has provided support for CBTT. For instance, Gómez and Freyd (2018) found that the link between within-group sexual violence and trauma symptoms, including depression and sleep problems, were stronger for minorities than majority members. These findings suggest that cultural betrayal in within-group violence in minority populations contributes to mental health difficulties above and beyond that explained by the within-group status of the perpetrator. Furthermore, additional work has found that when controlling for interracial trauma, cultural betrayal trauma, is associated with diverse outcomes (Gómez 2019c, 2019d) in sub-samples of Latino (hallucinations; Gómez 2017b), Asian American/Pacific Islander (dissociation, hallucinations, and PTSS; Gómez 2017a), and ethnic minority female (PTSS, dissociation; Gómez 2019b) emerging adults. Finally, one prior study on diverse ethnic minority young adults found that cultural betrayal trauma was linked with dissociation and hallucinations after controlling for ethnicity, high betrayal trauma, and interracial trauma (Gómez 2019c).

Purpose of the Study

Ethnic minority college students are at risk for victimization (e.g., Porter and McQuiller Williams 2011), with interpersonal violence being linked with PTSS (e.g., Ullman 2007). Furthermore, contextual factors, such as minority status, play a role in violence sequelae in ethnic minority populations (e.g., Brown 2008). Influenced by betrayal trauma theory (e.g., Freyd 1996) and ethnic minority trauma psychology (e.g., Bryant-Davis et al. 2009), CBTT (e.g., Gómez 2019a) was designed to examine outcomes of violence in diverse minority populations. Rigorously testing CBTT requires isolating the impact of in-group status of the perpetrator, known as cultural betrayal, and close relationship with the perpetrator, known as high betrayal. Thus, in addition to analogously controlling for between-group trauma and medium betrayal trauma—perpetrated by an unclose other(s)—controlling for gender and ethnicity can aid in not overattributing the impact of violence that could be better explained by differences based on the aforementioned demographics. Therefore, the purpose of the current study is to examine the associations between cultural betrayal and high betrayal in trauma with PTSS in a sample of diverse ethnic minority emerging adults. To do so: Hypothesis 1 tests betrayal trauma theory; Hypothesis 2 tests the independent associations of high betrayal and cultural betrayal in trauma with PTSS; and Hypothesis 3 examines how the differential level of interpersonal betrayal (high vs. medium) and cultural betrayal together are associated with PTSS.

Specifically, I hypothesize that:

1) Controlling for gender, ethnicity, and interracial trauma, high betrayal trauma will be associated with PTSS.

2) In adding cultural betrayal trauma to the model, both high betrayal trauma and cultural betrayal trauma will be associated with PTSS.

3) Controlling for gender, ethnicity, interracial trauma, and cultural betrayal trauma with medium betrayal, cultural betrayal trauma with high betrayal will be associated with PTSS.

Method

Participants

Participants (N = 296; Women: 60.5%; Men: 38.9%; Other: .3%; Decline to Answer: .3%) were ethnic minority college students attending a predominantly White public university in the Pacific Northwest. On average, participants were of traditional college age (M = 20.12; SD = 2.81) and ethnically diverse (35.0% Asian, 24.7% Hispanic/Latino American, 14.2% Other, 13.2% Black/African American, 5.7% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, 3.4% American Indian/Alaska Native, and 3.4% Middle Eastern).

Measures

These data are part of a larger study (Gómez 2018); therefore, only the measures used in the current analysis are included here.

Brief Betrayal Trauma Survey

The Brief Betrayal Trauma Survey (BBTS; Goldberg and Freyd 2006) has 12 items that measure rates of physical, sexual, and emotional abuse by close and unclose others, known as high betrayal and medium betrayal, respectively. To compare within-group and between-group status of the perpetrator, the BBTS was modified to ask if the perpetrator’s ethnicity was the same or different as that of the respondent. Within-group victimization is conceptualized as cultural betrayal trauma, whereas between-group victimization is labeled as interracial trauma. The Likert scale ranged from 1- never to 6- more than 100 times. A sample item is: “You were deliberately attacked so severely as to result in marks, bruises, blood, broken bones, or broken teeth by someone of your same ethnicity with whom you were very close.” The BBTS has demonstrated good test re-test reliability and validity as a measure of victimization (Goldberg and Freyd 2006). Given that the BBTS assesses different forms of abuse, a measure of internal consistency is not appropriate (Koss et al. 2007). In analyses, the BBTS was combined with the Sexual Experiences Survey (Koss and Oros 1982) to create a dichotomous variable (1- any victimization, 0- no victimization). Additional details below.

Sexual Experiences Survey

The modified Sexual Experiences Survey (SES; Koss and Oros 1982) has 28 items and assesses sexual victimization. In the current study, the SES was modified to match the BBTS (Goldberg and Freyd 2006) regarding relationship with and ethnic identity of the perpetrator. Like the BBTS (Goldberg and Freyd 2006), the SES used a 6-point Likert scale, from never to more than 100 times. A sample item is: “An unknown or unfamiliar person of the same ethnicity used some degree of physical force (twisting your arm, holding you down, etc.) to try to make you engage in kissing or petting when you didn’t want to.” The SES has demonstrated good test re-test reliability and is a valid measure of victimization (Koss, Gidycz, and Wisniewski, 1987; Koss and Gidycz 1985). Like the BBTS (Goldberg and Freyd 2006), a measure of internal consistency is not warranted because the SES assesses for different events (Koss et al. 2007) as opposed to an underlying construct. Across the modified BBTS (Goldberg and Freyd 2006) and SES (Koss and Oros 1982), the following dichotomous variables of 1-any victimization and 0-no victimization were calculated and used in analyses: any trauma; interracial trauma; high betrayal trauma; cultural betrayal trauma; cultural betrayal trauma with medium betrayal; and cultural betrayal trauma with high betrayal.

PTSD Checklist—5

The PTSD Checklist for DSM-5 (Weathers et al. 2013) is a 20-item questionnaire that assesses PTSS, including hyperarousal, avoidance, and negative alterations in mood. The questionnaire has a 5-point Likert scale from not at all to extremely. A sample item is: “In the past month, how much were you bothered by feeling jumpy or easily startled?” The PTSD Checklist—5 is a valid measure of PTSS (Weathers et al., 2013). The scoring incorporates the instructions and Likert scale across items, with higher scores indicating increased distress related symptomatology. A mean continuous variable for the entire measure was created and used in analyses. In this sample, the PTSD Checklist—5 had excellent internal consistency, α = .95.

Procedure

With the University’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval, participants were recruited from the University’s Human Subjects Pool through the online Sona system, which is a cloud-based subject pool software for universities (Sona Systems Ltd., 2018). A pre-screen item—“I identify as an ethnic minority”—was used to identify eligible individuals. Following completing the pre-screen item questionnaire for the Human Subjects Pool, students were provided with a list of studies they qualified for. Studies were named after composers, such that the current study could be named “Beethoven,” for instance, instead of “Study on Cultural Betrayal Trauma Theory in Ethnic Minority Emerging Adults.” Therefore, students chose the current online study based on the time and credit they would receive for participation, as opposed to self-selecting into the study based on content. This process serves to reduce self-selection bias. Participants accessed the study online at a location of their own choosing. Prior to beginning the study, students read through the consent form online, which informed potential participants of the topic of the study, that the study would take approximately 1 h to complete, that they would receive class credit for their participation, and that they could decline to answer any question or withdraw from the study at any time without penalty. Participants gave consent by clicking “Agree” at the bottom of the form. At the end of the study, participants were provided with a debriefing form that included the purpose of the study, contact information for the researchers, and a list of mental health resources in the community, including those with foci on cultural competency and violence.

Data Analysis Plan

All analyses were run using SPSS Software, Version 25. Five participants’ responses were excluded from analyses due to missing data. An additional participant was excluded because that participant did not identify as an ethnic minority (original sample, N = 302; current sample, N = 296). Descriptive analyses were run on all study variables. Two hierarchical linear regression analyses were run with the dependent variable, PTSS. In the first analyses, gender and ethnicity were inputted into Step 1, interracial trauma was added to Step 2, high betrayal trauma was entered in Step 3, and finally, cultural betrayal trauma was added into Step 4. In the second analyses, Steps 1 and 2 were the same, cultural betrayal trauma with medium betrayal was added to Step 3, and cultural betrayal trauma with high betrayal was inputted into Step 4. Finally, in order to assess the unique variance attributable to different betrayal traumas, squared semi-partial correlational analyses were run for the last step of each regression model, with gender, ethnicity, and interracial trauma as control variables.

Results

In this sample of ethnic minority college students attending a predominantly White public university, over half (52.0%) reported any violence exposure across the lifespan, with 44.3%, 43.9%, and 42.9% reporting any interracial, high betrayal, and cultural betrayal trauma, respectively. Additionally, almost one-quarter of participants reported cultural betrayal trauma with medium betrayal (23.4%), while over one-third reported cultural betrayal trauma with high betrayal (36.5%). The sample was relatively healthy, reporting low to moderate scores of PTSS (M = 1.80, SD = 0.76; sample range = 1–4.33).

In line with Hypothesis 1, hierarchical linear regression analyses revealed that while controlling for gender, ethnicity, and interracial trauma, high betrayal trauma was linked with PTSS. Support was also found for Hypothesis 2, with both high betrayal trauma (semi-partial r2 = .07) and cultural betrayal trauma (semi-partial r2 = .06) being associated with PTSS when controlling for gender, ethnicity, and interracial trauma (Table 1). Finally, Hypothesis 3 was partially supported, with cultural betrayal trauma with both medium betrayal (semi-partial r2 = .06) and high betrayal (semi-partial r2 = .06) each being associated with PTSS (Table 2). These results suggest that cultural betrayal that is implicit in intra-racial trauma may be a traumatic dimension of harm that is uniquely associated with PTSS in ethnic minority populations.

Table 1.

PTSS- Interracial, High Betrayal, & Cultural Betrayal Trauma: Hierarchical Linear Regression Analyses

| Step | Trauma | ß | R2 | F Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Gender | .019 | .003 | – |

| Ethnicity | −.051 | |||

| Step 2 | Gender | −.002 | .070 | F (1, 279) = 20.037*** |

| Ethnicity | −.044 | |||

| Interracial Trauma | .259*** | |||

| Step 3 | Gender | −.018 | .128 | F (1, 265) = 18.625*** |

| Ethnicity | −.041 | |||

| Interracial Trauma | .027 | |||

| High Betrayal Trauma | .337*** | |||

| Step 4 | Gender | .004 | .142 | F (1, 277) = 4.549* |

| Ethnicity | −.040 | |||

| Interracial Trauma | .027 | |||

| High Betrayal Trauma | .202* | |||

| Cultural Betrayal Trauma | .179* |

*significant at the .05 level; ***significant at the .001 level

High Betrayal Trauma: Perp- Close Other

Cultural Betrayal Trauma: Perp- Same Ethnicity

Table 2.

PTSS- Cultural Betrayal Trauma with and without High Betrayal: Hierarchical Linear Regression Analyses

| Step | Trauma | ß | R2 | F Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step 1 | Gender | .019 | .003 | – |

| Ethnicity | −.051 | |||

| Step 2 | Gender | −.002 | .070 | F (1, 279) = 20.037*** |

| Ethnicity | −.044 | |||

| Interracial Trauma | .259*** | |||

| Step 3 | Gender | −.018 | .138 | F (1, 278) = 22.012*** |

| Ethnicity | −.041 | |||

| Interracial Trauma | .125 | |||

| Cultural Betrayal Trauma with Medium Betrayal | .297*** | |||

| Step 4 | Gender | .004 | .170 | F (1, 277) = 10.818*** |

| Ethnicity | −.040 | |||

| Interracial Trauma | .027 | |||

| Cultural Betrayal Trauma with Medium Betrayal | .240*** | |||

| Cultural Betrayal Trauma with High Betrayal | .213*** |

*significant at the .05 level; ***significant at the .001 level

Cultural Betrayal Trauma with Medium Betrayal: Perp- Same Ethnicity, Unclose Other

Cultural Betrayal Trauma with High Betrayal: Perp- Same Ethnicity, Close Other

Discussion

The current study with diverse ethnic minority emerging adults contributes to the literature that suggests that the marginalization experienced by minorities impacts mental and behavioral health following trauma (e.g., Brown 2008; Bryant-Davis 2005). By examining perceived ethnicity of the perpetrator, the current study complements the research that theoretically (e.g., Freyd 1997) and empirically (e.g., Delker and Freyd 2017; Edwards et al. 2012; Kelley et al. 2012; Gobin and Freyd 2017; Ullman 2007) show that close relationship with the perpetrator, known as high betrayal, impacts mental health. As an additional dimension of traumatic harm, the current study further examines the impact on PTSS of within-group victimization in ethnic minorities, known as cultural betrayal trauma. Though some findings were mixed, the results by and large show that cultural betrayal, and at times high betrayal, in trauma contribute to PTSS in diverse ethnic minority emerging adults.

Specifically, in line with decades of work on betrayal trauma theory (see DePrince et al. 2012; Gómez et al. 2014bfor reviews), Hypothesis 1 was supported in this ethnically diverse sample of emerging adults, with high betrayal trauma predicting PTSS above and beyond the violence itself (Edwards et al. 2012; Kelley et al. 2012; Klest et al. 2013; Ullman 2007). Additionally, Hypothesis 2 was supported, with both high betrayal trauma and cultural betrayal trauma being associated with PTSS while controlling for gender, ethnicity, and interracial trauma. This finding is particularly important given that previous work on dissociation and hallucinations showed that high betrayal trauma was no longer linked to these outcomes when cultural betrayal trauma was included in the model (Gómez 2019c). These mixed findings potentially point to the nuance in violence sequelae, with different kinds of betrayal predicting disparate mental health outcomes, such as dissociation and PTSS. Thus, findings for the associations between high betrayal and cultural betrayal trauma on one outcome should not be interpreted as necessarily generalizing to other mental health outcomes.

Finally, Hypothesis 3 was partially supported. After controlling for gender, ethnicity, interracial trauma, and cultural betrayal trauma with medium betrayal, cultural betrayal trauma with high betrayal was associated with PTSS; however, cultural betrayal trauma with medium betrayal was still linked with PTSS in this model, indicating that the within-group identity of the perpetrator contributed to outcomes regardless of the relationship with the perpetrator. This finding is similar to prior work (Gómez 2019c), in which high betrayal trauma was no longer a significant predictor of hallucinations when cultural betrayal trauma was included in the model. The current study’s analysis should be tested again in other samples to see if it can be replicated. If it is, future work can further examine what makes cultural betrayal, as opposed to high betrayal, an important factor in PTSS specifically. For instance, it is possible that hypervigilance related to seeing people of the same ethnic group exacerbates symptomatology (Gómez 2015). Taken together, these findings bolster the literature on CBTT, suggesting that cultural betrayal is a dimension of traumatic harm that helps explain outcomes of violence (Gómez 2017a, b, 2019a, b, c, d; Gómez and Freyd 2018, 2019; Gómez and Gobin 2020).

Research Implications

The current study adds to the literatures on both betrayal trauma theory (e.g., Freyd 1996) and CBTT (e.g., Gómez and Gobin 2020). Given the relative newness of CBTT, research implications include attempts to replicate the current study’s findings. Moreover, future work should continue to assess the independent and joint impacts of high betrayal and cultural betrayal, given that most perpetrators are both known and of the same ethnic group as those they victimize (e.g., Bryant-Davis et al. 2009). The ethnic diversity of the sample provides an important landscape for testing CBTT. However, this diversity also masks between and within-group differences (O’Connor et al. 2007; Pole and Triffleman 2010) in both victimization and outcome trajectory. Therefore, future work that employs a community-of-interest approach can design studies within a minority group and incorporate group-level cultural experiences, such as type of oppression and acculturation. This could provide increased specificity to the empirical understanding of violence within and across ethnic groups. Moreover, latent class analyses can identify trajectories for cultural betrayal trauma’s impact on mental health in diverse subpopulations, such as gay Black young men and Latinas with high SES backgrounds. Such an approach provides an avenue for incorporating how multiple identities and forms of oppression impact violence sequelae among diverse individuals.

Clinical Implications

Emerging adulthood is a unique time period of both risk and development. Specifically, there is increased risk for the onset of mental health problems during the transition into adulthood (Hunt and Eisenberg 2010; Kessler et al. 2007). Moreover, students may be particularly vulnerable in the university setting: students have lowered status and power within the hierarchy of academia—potentially with minority students enduring even lower status given societal inequality; they tend to be of younger age; they often have pride for their university; and perhaps most importantly, students depend on the university, not only for education, food, and housing, but also for social and emotional resources at a time in their lives that for many are transitional (Gómez et al. 2014b). Both violence (Porter and McQuiller Williams 2011; Smith and Freyd 2013, 2017; Smith et al. 2016; Smidt et al. 2019) and discrimination (Harwood et al. 2012; Solórzano et al. 2000; Pyke 2018) that occur while in college may further contribute to deleterious mental health.

While uncovering relatively high rates of violence exposure, the current study utilizes CBTT to better understand the ways in which the relational and ethnic identities of perpetrators is related to PTSS in diverse ethnic minority college students. Given that cultural betrayal in trauma, irrespective of close/unclose relationship with the perpetrator, was associated with PTSS, campus interventions can focus on addressing cultural betrayal as an entry point to healing. Specifically, campus violence interventions can deliberately and explicitly assess for and, as relevant, incorporate how students’ (intra)cultural trust and cultural betrayal impact their experiences of violence. For instance, standard therapeutic questions about victimization can be accompanied with queries around perpetrator ethnic identity, as well as comfort level with discussion regarding within-group victimization in the setting of a predominantly White university. As a result, campus interventions that proactively incorporate such factors may be more desirable and effective for ethnic minority students who experience cultural betrayal trauma.

Relatedly, the current study’s findings are in line with calls for cultural competency in clinical interventions for people who experience violence (e.g., Brown 2004, 2008; Bryant-Davis 2005), which can include attending to how cultural betrayal in trauma may impact mental health and engagement in predominantly White mental health care settings. Furthermore, relational cultural therapy (Jordan 2010; Miller 1976; Miller and Stiver 1997) may be particularly beneficial for people who experience cultural betrayal trauma (Gómez 2020; Gómez et al. 2016). Relational cultural therapy (e.g., Miller and Stiver 1997) is an evidence-informed therapeutic approach that can conceptualize how violence exposure is impacted by systemic equality based on gender, race, and other identities, while centralizing the therapeutic relationship as a primary mechanism of change. In doing so, relational cultural therapy (e.g., Miller 1976) grapples with interpersonal power dynamics in ways that are congruent with CBTT. For instance, by hypothesizing that a Black young woman’s reluctance to speak with a White therapist about her Black perpetrator is due to her wanting to protect the Black community, this potential barrier can be assessed and further addressed in therapy. Thus, the therapeutic process can become more culturally congruent in at least this one domain and conceivably may be more beneficial in reducing mental health symptoms.

Limitations & Future Directions

The current study provides some insight into how intra-racial trauma as a cultural betrayal trauma in ethnic minority populations may be associated with PTSS. Future research can build upon the current study’s limitations. First, in this study, measures that have been validated on majority White samples were adapted to include information on ethnicity of perpetrator; thus, the psychometric properties of the adapted measures are unknown. Furthermore, key constructs of CBTT, including (intra)cultural trust, were excluded from measurement entirely. Creating and validating a questionnaire for CBTT can address both of these limitations. Such a measure could be developed within a community of interest, such as Black American emerging adults, and include assessments for (intra)cultural trust, cultural betrayal, cultural betrayal trauma, (intra)cultural support, and (intra)cultural pressure. This allows for testing potential mediators and moderators for outcomes of cultural betrayal trauma, thus facilitating the examination of important within- and between-group differences. Moreover, future work can tease apart the differential impact of cultural betrayal in physical, sexual, and emotional abuse from both single and cumulative measures of trauma and revictimization, including types of betrayals in trauma. Additionally, developmental time period of abuse, as well as type, duration, and severity of abuse was not assessed in the current study; therefore, the impact of these factors in conjunction with high betrayal and cultural betrayal remains unclear. Other potential confounds should also be incorporated into future work, such as year in school, nativity status, and experiences with discrimination. Finally, though institutions of higher learning provide an important site for understanding violence sequelae given relatively high prevalence rates (e.g., Porter and McQuiller Williams 2011), future research can explore the current study’s research questions in community and clinical samples to gain a better sense of generalizability across various ethnic minority populations. Such research can incorporate the multi-systemic oppression (e.g., racism, classism, sexism) that different ethnic minority groups face to better understand its role in violence sequelae.

Concluding Thoughts

Over the years, research has evolved to incorporate how various components of the violence contribute to its harm (e.g., DePrince and Freyd 2002). Specifically, betrayal trauma theory itself and its empirical foundation have crystallized the importance of relationship with the perpetrator (e.g., Freyd 1996). As another dimension of traumatic harm, cultural betrayal (e.g., Gómez 2019d) can provide additional specificity to empirical models that examine violence sequelae. As such, clinical interventions can address cultural betrayal and other facets of CBTT (e.g., (intra)cultural pressure) to better serve diverse minorities who experience violence.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

The current study was made possible through funding from the Ford Foundation Fellowship Programs, administered by the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, & Medicine.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Black, M. C. et al. (2011). Center for Disease Control & Prevention national intimate partner and sexual violence survey: Summary report. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/ViolencePrevention/pdf/NISVS_Report2010-a.pdf

- Briere J, Scott C. Principles of trauma therapy: A guide to symptoms, evaluation, and treatment. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Brown LS. Feminist paradigms of trauma treatment. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training. 2004;41:464–471. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.41.4.464. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown L. Cultural competence in trauma therapy: Beyond the flashback. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Brown LS, Freyd JJ. PTSD criterion a and betrayal trauma: A modest proposal for a new look at what constitutes danger to self. Trauma Psychology, Division 56. American Psychological Association, Newsletter. 2008;3:11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T. Thriving in the wake of trauma: A multicultural guide. Westport, CT: Praeger Publishers; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T. Cultural considerations of trauma: Physical, mental and social correlates of intimate partner violence exposure. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy. 2010;2:263–265. doi: 10.1037/a0022040. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bryant-Davis T, Chung H, Tillman S, Belcourt A. From the margins to the center: Ethnic minority women and the mental health effects of sexual assault. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse. 2009;10:330–357. doi: 10.1177/1524838009339755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burstow B. Toward a radical understanding of trauma and trauma work. Violence Against Women. 2003;9:1293–1317. doi: 10.1177/1077801203255555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Burstow B. A critique of posttraumatic stress disorder and the DSM. Journal of Humanistic Psychology. 2005;45:429–445. doi: 10.1177/0022167805280265. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Christopher M. A broader view of trauma: A biopsychosocial-evolutionary view of the role of the traumatic stress response in the emergence of pathology and/or growth. Clinical Psychology Review. 2004;24:75–98. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Deblinger E, Mannarino A, de Arellano M. The importance of culture in treating abused and neglected children: An empirical review. Child Maltreatment. 2001;6:148–157. doi: 10.1177/1077559501006002007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole ER, Stewart AJ. Invidious comparisons: Imagining a psychology of race and gender beyond differences. Political Psychology. 2001;22:293–308. doi: 10.1111/0162-895X.00240. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Delker BC, Freyd JJ. Betrayed? That’s me: Implicit and explicit betrayed self-concept in young adults abused as children. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, & Trauma. 2017;26:701–716. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2017.1308982. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DePrince, A.P, Brown, L.S., Cheit, R.E., Freyd, J.J., Gold, S.N., Pezdek, K. & Quina, K (2012). Motivated forgetting and misremembering: Perspectives from betrayal trauma theory. In Belli, R. F. (Ed.), True and false recovered memories 193-242. 10.1007/978-1-4614-1195-6_7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- DePrince AP, Freyd JJ. The harm of trauma: Pathological fear, shattered assumptions, or betrayal. In: Kauffman J, editor. Loss of the assumptive world: A theory of traumatic loss. New York: Brunner-Routledge; 2002. pp. 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Edwards VJ, Freyd JJ, Dube SR, Anda RF, Felitti VJ. Health outcomes by closeness of sexual abuse perpetrator: A test of betrayal trauma theory. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2012;21:133–148. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2012.648100. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Gómez JM. The relationship of psychological trauma, and dissociative and posttraumatic stress disorders to non-suicidal self-injury and suicidality: A review. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2015;6:232–271. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2015.989563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freyd JJ. Betrayal trauma: The logic of forgetting childhood abuse. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Freyd JJ. Violations of power, adaptive blindness, and betrayal trauma theory. Feminism Psychology. 1997;7:22–32. doi: 10.1177/0959353597071004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gobin RL, Freyd JJ. Betrayal and revictimization: Preliminary findings. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy. 2009;1:242–257. doi: 10.1037/a0017469. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gobin RL, Freyd JJ. Do participants detect sexual abuse depicted in a drawing? Investigating the impact of betrayal trauma exposure on state dissociation and betrayal awareness. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2017;26:233–245. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2017.1283650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldberg LR, Freyd JJ. Self-reports of potentially traumatic experiences in an adult community sample: Gender differences and test-retest stabilities of the items in a brief betrayal-trauma survey. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2006;7:39–63. doi: 10.1300/J229v07n03_04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith RE, Freyd JJ, DePrince AP. Betrayal trauma: Associations with psychological and physical symptoms in young adults. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2012;27:547–567. doi: 10.1177/0886260511421672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, J. M. (2012). Cultural betrayal trauma theory: The impact of culture on the effects of trauma. In Blind to Betrayal. Retrieved from https://sites.google.com/site/betrayalbook/betrayal-research-news/cultural-betrayal

- Gómez, J. M. (2015). Conceptualizing trauma: In pursuit of culturally relevant research. Trauma Psychology Newsletter (American Psychological Association Division 56), 10, 40-44.

- Gómez JM. Does ethno-cultural betrayal in trauma affect Asian American/Pacific islander college students’ mental health outcomes? An exploratory study. Journal of American College Health. 2017;65:432–436. doi: 10.1080/07448481.2017.1341896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, J. M., Lewis, J. K., Noll, L. K., Smidt, A. M., & Birrell, P. J. (2016). Shifting the focus: Nonpathologizing approaches to healing from betrayal trauma through an emphasis on relational care. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 17, 165–185. 10.1080/15299732.2016.1103104 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gómez, J. M. (2017b). Does gender matter? An exploratory study of cultural betrayal trauma and hallucinations in Latino undergraduates at a predominantly White university. Advanced online publication. Journal of Interpersonal Violence., 088626051774694. 10.1177/0886260517746942. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Gómez, J. M. (2018). Cultural betrayal trauma theory. Dissertation Abstracts International: Section B: The Sciences and Engineering, 79(4-B)(E).

- Gómez JM. Group dynamics as a predictor of dissociation for Black victims of violence: An exploratory study of cultural betrayal trauma theory. Transcultural Psychiatry. 2019;56:878–894. doi: 10.1177/1363461519847300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez JM. Isn’t it all about victimization? (intra)cultural pressure and cultural betrayal trauma in ethnic minority college women. Violence Against Women. 2019;25:1211–1225. doi: 10.1177/1077801218811682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez JM. What’s in a betrayal? Trauma, dissociation, and hallucinations among high-functioning ethnic minority emerging adults. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2019;28:1181–1198. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2018.1494653. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez JM. What’s the harm? Internalized prejudice and intra-racial trauma as cultural betrayal among ethnic minority college students. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2019;89:237–247. doi: 10.1037/ort0000367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez JM. Trainee perspectives on relational cultural therapy and cultural competency in supervision of trauma cases. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration. 2020;30:60–66. doi: 10.1037/int0000154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez JM, Allan N, Santa Ana EJ, Stecker T. Depression and intention to seek treatment among Black and White suicidal military members who are not engaged in mental health care. Advanced online publication. Military Behavioral Health. doi. 2018;6:290–299. doi: 10.1080/21635781.2018.1438937. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez JM, Freyd JJ. High betrayal child sexual abuse and hallucinations: A test of an indirect effect of dissociation. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2017;26:507–518. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2017.1310776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez JM, Freyd JJ. Psychological outcomes of within-group sexual violence: Evidence of cultural betrayal. Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health. 2018;20:1458–1467. doi: 10.1007/s10903-017-0687-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez JM, Freyd JJ. Betrayal trauma. In: Ponzetti JJ, editor. Macmillan encyclopedia of intimate and family relationships: An interdisciplinary approach. Boston, MA: Cengage Learning Inc.; 2019. pp. 79–82. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez JM, Gobin RL. Black women and girls & #MeToo: Rape, cultural betrayal, & healing. Sex Roles: A Journal of Research. 2020;82:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11199-019-01040-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez JM, Kaehler LA, Freyd JJ. Are hallucinations related to betrayal trauma exposure? A three-study exploration. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, & Policy. 2014;6:675–682. doi: 10.1037/a0037084. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gómez JM, Smith CP, Freyd JJ. Zwischenmenschlicher und institutioneller verrat [interpersonal and institutional betrayal] In: Vogt R, editor. Verleumdung und Verrat: Dissoziative Störungen bei schwer traumatisierten menschen als Folge von Vertrauensbrüchen. Roland, Germany: Asanger Verlag; 2014. pp. 82–90. [Google Scholar]

- Harwood SA, Huntt MB, Mendenhall R, Lewis JA. Racial microaggressions in the residence halls: Experiences of students of color at a predominantly White university. Journal of Diversity in Higher Education. 2012;5:159–173. doi: 10.1037/a0028956. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey MR. Towards an ecological understanding of resilience in trauma survivors: Implications for theory, research, and practice. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, & Trauma. 2007;14:9–32. doi: 10.1300/J146v14n01_02. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harvey MR, Tummalanarra P. Sources and expression of resilience in trauma survivors: Ecological theory, multicultural perspectives. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2007;14:1–7. doi: 10.1300/J146v14n01_01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Henrich J, Heine SJ, Norenzayan A. Most people are not WEIRD. Nature. 2010;466:29–29. doi: 10.1038/466029a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt J, Eisenberg D. Mental health problems and help-seeking behavior among college students. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2010;46:3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2009.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jordan JV. Relational-cultural therapy. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Kaehler LA, Freyd JJ. Borderline personality characteristics: A betrayal trauma approach. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2009;1:261–268. doi: 10.1037/a0017833. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley LP, Weathers FW, Mason EA, Pruneau GM. Association of life threat and betrayal with posttraumatic stress disorder symptom severity. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2012;25:408–415. doi: 10.1002/jts.21727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Amminger GP, Aguilar-Gaxiola S, Alonso J, Lee S, Ustun TB. Age of onset of mental disorders: A review of recent literature. Current Opinion in Psychiatry. 2007;20:359–364. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e32816ebc8c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilpatrick DG, Acierno R. Mental health needs of crime victims: Epidemiology and outcomes. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2003;16:119–132. doi: 10.1023/A:1022891005388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klest B, Freyd JJ, Foynes MM. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic symptoms in Hawaii: Gender, ethnicity, and social context. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2013;5:409–416. doi: 10.1037/a0029336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korbin JE. Culture and child maltreatment: Cultural competence and beyond. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2002;26:637–644. doi: 10.1016/S0145-2134(02)00338-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Abbey A, Campbell R, Cook S, Norris J, Testa M, Ullman S, West C, White J. Revising the SES: A collaborative process to improve assessment of sexual aggression and victimization. Psychology of Women Quarterly. 2007;31:357–370. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6402.2007.00385.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Gidycz CA. Sexual experiences survey: Reliability and validity. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1985;53:422–423. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.53.3.422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss MP, Oros CJ. Sexual experiences survey: A research instrument investigating sexual aggression and victimization. Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology. 1982;50:455–457. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.50.3.455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koss, M. P., Gidycz, C. A., & Wisniewski, N. (1987). The scope of rape: Incidence and prevalence of sexual aggression and victimization in a national sample of higher education students. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 55, 162–170. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Lilly MM, Valdez CE. Interpersonal trauma and PTSD: The roles of gender and a lifespan perspective in predicting risk. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2012;4:140–144. doi: 10.1037/a0022947. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Littleton H, Ullman SE. PTSD symptomatology and hazardous drinking as risk factors for sexual assault revictimization: Examination in European American and African American women. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26:345–353. doi: 10.1002/jts.21807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller JB. Toward a new psychology of women. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- Miller JB, Stiver IP. The healing connection: How women form relationships in therapy and in life. Boston, MA: Beacon Press; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Morgan, R.E., & Truman, J. L. (2018). U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Statistics, criminal victimization, 2017. Retrieved from https://www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/cv17.pdf

- National Center for Victims of Crime (2012). Crime information and statistics. Retrieved from http://victimsofcrime.org/library/crime-information-and-statistics

- O’Connor C, Lewis A, Mueller J. Researching “Black” educational experiences and outcomes: Theoretical and methodological considerations. Educational Researcher. 2007;36:541–552. doi: 10.3102/0013189X07312661. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pole NE, Triffleman EE. Introduction to the special issue on trauma and ethnoracial diversity. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2010;2:1–3. doi: 10.1037/a0018979. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Porter J, McQuiller Williams L. Intimate violence among underrepresented groups on a college campus. Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 2011;26:3210–3224. doi: 10.1177/0886260510393011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyke KD. Institutional betrayal: Inequity, discrimination, bullying, and retaliation in academia. Sociological Perspectives. 2018;61:5–13. doi: 10.1177/0731121417743816. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rape, Abuse, & Incest National Network (2016). Statistics. Retrieved from https://www.rainn.org/statistics

- Smidt, A. M., Rosenthal, M. N., Smith, C. P., & Freyd, J. J. (2019). Out and in harm's way: Sexual minority students’ psychological and physical health after institutional betrayal and sexual assault. Advanced online publication. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. doi, 1–15. 10.1080/10538712.2019.1581867. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Smith CP, Freyd JJ. Dangerous safe havens: Institutional betrayal exacerbates sexual trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 2013;26:119–124. doi: 10.1002/jts.21778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CP, Freyd JJ. Insult, then injury: Interpersonal and institutional betrayal linked to health and dissociation. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment, & Trauma. 2017;26:1117–1131. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2017.1322654. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith CP, Cunningham S, Freyd JJ. Sexual violence, institutional betrayal, and psychological outcomes for LGB college students. Translational Issues in Psychological Science. 2016;2:351–360. doi: 10.1037/tps0000094. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solórzano D, Ceja M, Yosso T. Critical race theory, racial microaggressions, and campus racial climate: The experiences of African American college students. Journal of Negro Education. 2000;69:60–73. [Google Scholar]

- Sona System, Ltd. (2018). Sona Systems. Retrieved from https://www.sona-systems.com/default.aspx

- Tyagi, S. V. (2002). Incest and women of color: A study of experiences and disclosure.Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 10, 17-39. 10.1300/J070v10n02_02. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Ullman SE. Relationship to perpetrator, disclosure, social reactions, and PTSD symptoms in child sexual abuse survivors. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2007;16:19–36. doi: 10.1300/J070v16n01_02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ullman, S. E., & Filipas, H. H. (2005). Gender differences in social reactions to abuse disclosures, post-abuse coping, and PTSD of child sexual abuse survivors. Child Abuse & Neglect, 29, 767–782. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Weathers, F. W., Litz, B. T., Keane, T. M., Palmieri, P. A., Marx, B. P., & Schnurr, P. P. (2013). The ptsd checklist for dsm-5 (pcl-5). Scale available from the National Center for PTSD at https://www.ptsd.va.gov/.