Abstract

The social-ecological diathesis-stress model and related empirical work suggests that individuals who experienced peer victimization in childhood are at risk of revictimization and internalizing problems in young adulthood. The current study examined the association between retrospective and current reports of traditional and cyber victimization and internalizing problems, and the buffering effect of resiliency among 1141 young adults. Results indicated that retrospective traditional victimization was positively associated with current traditional and cyber victimization. Retrospective cyber victimization, however, was positively associated with current cyber victimization only. Retrospective traditional and cyber victimization were positively associated with internalizing problems while controlling for current victimization for both males and females. Resiliency buffered the positive association between retrospective cyber victimization, but not traditional victimization, and current internalizing problems. Findings suggest that retrospective accounts of peer victimization may have a lasting impact on symptoms of depression and anxiety for young adults, regardless of current victimization experiences. Longitudinal studies are needed to examine the associations among revictimization and mental health, and potential buffering mechanisms, among young adults.

Keywords: Traditional victimization, Cyber victimization, Depression, Anxiety, Resiliency

Introduction

Peer victimization is recognized as a public health concern and decades of research have documented its concurrent and lasting effects on overall well-being (Moore et al. 2017). The literature on peer victimization has focused on school-age youth; however, bullying and its effects continue beyond the high school years. Young adulthood is a developmental period that involves a sudden absence of parental supervision, shifts in peer norms, and increased responsibilities (e.g., work, college). Although changes in environments or peer groups may be positive for individuals who previously experienced peer victimization, risk factors for victimization often remain stable (Troop-Gordon 2017). In line with the social-ecological diathesis-stress model (Swearer and Hymel 2015), individuals with prior victimization experiences may continue to be at risk of “revictimization”—as well as subsequent internalizing problems (e.g., depressive symptoms, anxiety)—in young adulthood (Adams and Lawrence 2011; Espelage et al. 2016; Felix et al. 2019). Less is known about the impact of retrospective reports of peer victimization on internalizing problems beyond the effects of current victimization and potential moderating variables. The current study intended to fill these gaps in the literature by examining the association between both retrospective and current reports of traditional and cyber victimization and internalizing problems, and the buffering effect of perceptions of resiliency among young adults through the lens of the social-ecological diathesis-stress model.

Peer Victimization

Peer victimization is unwanted, repetitive, and intentionally harmful behavior directed toward an individual with less power than the perpetrator (Gladden et al. 2014). Peer victimization includes both traditional victimization—bullying that occurs in person including physical (e.g., hitting or kicking), verbal (e.g., name calling), and relational (e.g., rumor spreading)—and cyber victimization, which occurs via electronic devices or online. Approximately 20% to 35% of adolescents report experiencing traditional victimization and 15% report cyber victimization (Kann et al. 2018; Modecki et al. 2014). Prevalence rates among young adults and college students have ranged from 10% to 27% for cyber victimization (Selkie et al. 2015). Traditional peer victimization is less frequent in elementary school, peaks in middle school, and declines through high school (Schneider et al. 2015). Cyber victimization, however, continues to increase throughout high school. Little research has focused on peer victimization and its effects in young adulthood, especially outside of college populations. This needs to be remedied, however, because peer victimization in childhood and adolescence can have lasting effects into adulthood, including anxiety, depression, and PTSD symptoms (Espelage et al. 2016; Hill et al. 2017; Lereya et al. 2015).

Social-Ecological Diathesis-Stress Model

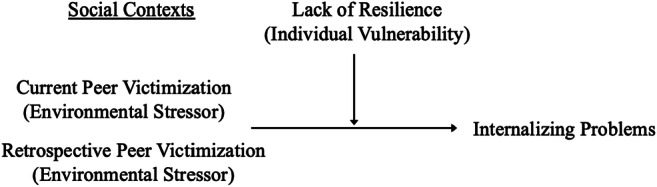

Decades of research have examined peer victimization through the lens of social-ecological theory (Swearer and Hymel 2015), which posits that risk and protective factors occur and interact across contexts (e.g., individual, school, family, peer; Bronfenbrenner 1979). It is well known that peer victimization does not occur solely between the perpetrator and target, but rather within social contexts (Swearer and Hymel 2015). In fact, contextual factors, such as school climate (Espelage et al. 2014), peer groups (Zhu et al. 2017), family (Tucker et al. 2020), and community (Huang and Cornell 2019) have been found to have a sizable influence on peer victimization. Further, the diathesis-stress model posits that mental health problems occur based on the interplay between environmental stressors and a person’s vulnerability to psychopathology (Lazarus 1993). Thus, peer victimization can be considered an environmental stressor which contributes to negative outcomes, including internalizing problems such as depression and anxiety (Swearer and Hymel 2015). This is consistent with prior research on the etiology of internalizing problems (e.g., depression), including cognitive behavioral models which posit that cognitive vulnerabilities (e.g., biased information processing, maladaptive schema) and environmental stressors (e.g., peer victimization) interact in the development of depressive symptoms (Abela and Hankin 2008; Fredrick and Demaray 2018). Similarly, low resiliency can be considered an individual vulnerability towards the development of psychopathology. Thus, as recommended by Swearer and Hymel (2015), the current study integrated the social-ecological and diathesis-stress models in order to better understand the relations among peer victimization, revictimization, resilience, and internalizing problems among young adults (see Fig. 1 for a conceptual model).

Fig. 1.

Conceptual model of study variables within a social-ecological diathesis-stress framework

Revictimization among College Students and Young Adults

According to social-ecological theory, a new context—such as college or workplace—may reduce or increase risk of peer victimization. The literature on revictimization among college students and young adults has largely focused on sexual victimization and only two known studies to date have examined revictimization in the context of peer victimization. Adams and Lawrence (2011) surveyed 269 undergraduates and found that those who had indicated that they were bullied prior to college had significantly higher scores than their peers without a history of victimization on a measure looking at current victimization and negative experiences with peers. Felix et al. (2019) investigated peer victimization and aggressive behavior retrospectively and during the first year of college among 428 college students. Based on retrospective reports, findings from latent class analysis revealed four classes: (1) high victimization and aggression (12%), (2) low involvement (37%), (3) high victimization/low aggression (20%), and (4) high relational victimization and relational aggression (31%). When surveyed again the following semester, latent transition analysis revealed that most students transitioned into the low involvement group; however, the high victimization/aggression class had the fewest participants transition to the low involvement group. This suggests that those participants that reported high levels of victimization prior to college were at highest risk for revictimization over their first year of college. Given the ubiquitous use of screen media among individuals, research is needed to understand retrospective accounts and revictimization specifically for cyber victimization among young adults and whether these relations differ for males and females.

Peer Victimization, Depressive Symptoms, and Anxiety

Diathesis-stress models posit that peer victimization—an environmental stressor—interacts with an individual’s vulnerabilities, resulting in negative outcomes, including depression and anxiety (Swearer and Hymel 2015). Thus, in addition to risk for revictimization, being bullied in childhood or adolescence can have negative impacts on mental health years later in young adulthood. Longitudinal studies have in fact found that childhood victimization has lasting effects on depressive symptoms and anxiety in adulthood for both traditional and cyber victimization (Hill et al. 2017; Lereya et al. 2015). Retrospective accounts of bullying victimization (i.e., recalling past experiences of victimization) have also been linked with both depressive symptoms and anxiety among college students (Reid et al. 2016). Findings from cross-sectional studies also suggest a positive relation between victimization while at college and depressive symptoms and anxiety. Schenk and Fremouw (2012) found that undergraduate students who reported experiencing cyberbullying scored significantly higher on numerous negative outcomes, including depression and anxiety, compared to matched controls who had not experienced cyberbullying. Tennant et al. (2015) found that cybervictimization accounted for a change in depressive symptoms beyond what was accounted for by traditional victimization. Although there is clearly a relation between current experiences of victimization and distress, and odds of revictimization are high among college students, no known research has looked at the association between past victimization and current internalizing problems, while controlling for current victimization. Because peer victimization is stable over time—particularly for those that had experienced high levels of victimization—it is important to parcel out the effects of current and retrospective victimization on mental health.

Sex Differences

Findings are mixed regarding sex differences in peer victimization, although some studies have found that females report higher levels of both traditional and cyber victimization (Kann et al. 2018). Espelage et al. (2016) found a positive association between retrospective accounts of childhood peer victimization and psychological functioning (depressive symptoms, anxiety, post-traumatic stress symptoms) after controlling for other childhood victimization experiences for female undergraduate students. These findings are consistent with previous research which has found a more robust relation between peer victimization and depression and anxiety for females than for males (Iyer-Eimerbrink et al. 2015). Selkie et al. (2015) found that female college students (N = 265) who had experienced cyberbullying were nearly three times more likely to meet criteria for clinical depression than their counterparts who had not experienced cyberbullying. Although there is some support for females experiencing higher levels of victimization—and higher levels of internalizing problems—more research is needed to examine the relations among retrospective and current experiences of victimization and how these experiences relate to internalizing problems for males and females.

The Protective Role of Resiliency

Although diathesis-stress models and related empirical work have found peer victimization to be associated with negative mental health outcomes both concurrently and over time, not all individuals who experience peer victimization experience these deleterious outcomes. Thus, it is important to examine protective factors that may interact with peer victimization and reduce risk of these negative outcomes. There has been increased focus on the construct of resilience—particularly in developmental psychology research—in the past decade, and it has been suggested that resiliency can be taught or reinforced through the environment (Forbes and Fikretoglu 2018), making resiliency an appealing characteristic to examine as a protective factor for youth and adults involved in bullying. Resiliency has been defined as protective factors internal to an individual (e.g., self-esteem) or external in their environment (e.g., social support) that help individuals thrive despite experiencing certain stressors (Luthar et al. 2000). Smith et al. (2008) posits that a more basic definition of resilience is the ability to “bounce back” from stressful experiences and when measuring resiliency we should focus on this basic definition as opposed to the internal or external traits that make an individual resilient. In a large sample of adolescents ages 12- to 17-years (N = 1204), Hinduja and Patchin (2017) found that adolescents higher in resiliency—assessed by self-perceptions of the ability to bounce back from adversity—were less likely to report being bullied and cyberbullied. These youth were also less likely to report that any bullying they experienced (either at school or online) negatively affected their feelings of safety or ability to learn. In a sample of 1430 undergraduate students in Spain, Víllora et al. (2020) found resiliency to moderate the relation between poly-bullying victimization (i.e., experiencing multiple forms of bullying) and subjective well-being such that students experiencing higher levels of poly-bullying victimization and higher resiliency also reported higher well-being compared to students that reported lower resiliency. Further research is needed to better understand if perceptions of resiliency may be a protective factor for young adults with prior experiences of peer victimization.

Current Study

Few studies have examined peer victimization among young adults and further research is needed to examine implications of prior experiences of victimization as they relate to young adults’ risk for revictimization and mental health problems. The few studies to date that have examined revictimization as it relates to peer victimization did not examine cyber victimization and the samples were limited to college students in single geographic locations (Adams and Lawrence 2011; Felix et al. 2019). Further, studies are needed to examine possible moderators (i.e., buffers) in the relation between childhood peer victimization and current internalizing problems. Thus, through the lens of the social-ecological diathesis-stress model, the current study fills these gaps in the literature by investigating the relations among current and retrospective experiences of traditional and cyber victimization, internalizing symptoms, and resiliency among a large, geographically diverse sample of young adults.

The following research questions guided the current investigation: (1) Is there a relation between retrospective peer victimization and current peer victimization and are there sex differences in this relation? (2) Is there a relation between retrospective peer victimization and current depressive and anxiety symptoms, controlling for current victimization? Are there sex differences among these relations? (3) Is resiliency a moderator in the relation between retrospective victimization and current depression and anxiety, controlling for current victimization? We predicted a positive relation among retrospective and current traditional and cyber victimization (Adams and Lawrence 2011; Felix et al. 2019) and that retrospective traditional and cyber victimization would be positively associated with depressive symptoms and anxiety above and beyond current traditional and cyber victimization. We also predicted that these relations would be more robust for females. Finally, we predicted that resiliency would moderate, or buffer, the positive relation between retrospective peer victimization internalizing problems, such that retrospective peer victimization would not be associated with depressive symptoms and anxiety at high levels of resiliency (Hinduja and Patchin 2017; Víllora et al. 2020).

Method

Participants

The current study included 1161 participants who were recruited through Mturk (n = 622) and a Midwestern university (n = 539). Twenty participants’ data were deleted due to endorsing validity items; thus, the final sample consisted of 1141 participants (65% female, 74% White, 70% between 18- to 22-years-old, 71% full time college students). See Table 1 for a description of participant demographics.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Variable | n | % |

|---|---|---|

| Gender | ||

| Male | 363 | 32 |

| Female | 744 | 65 |

| Transgender | 12 | 1 |

| Non-Conforming/Prefer Not to Answer | 20 | 2 |

| Age | ||

| 18 | 250 | 22 |

| 19 | 135 | 12 |

| 20 | 112 | 10 |

| 21 | 144 | 13 |

| 22 | 148 | 13 |

| 23+ | 350 | 31 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||

| White | 846 | 74 |

| Black/African American | 131 | 11 |

| Hispanic/Latino | 47 | 4 |

| Asian | 48 | 4 |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 4 | <1 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 26 | 2 |

| Multiracial/Biracial | 65 | 6 |

| Other/Prefer Not to Say | 6 | 1 |

| Student Status | ||

| Full Time | 815 | 71 |

| Part Time | 112 | 10 |

| Not Enrolled | 204 | 18 |

Note. Two participants had missing responses on all demographic items. Percentage of respondents summed to greater than 100% for the race/ethnicity variable because participants could select more than one applicable racial/ethnic group

Measures

Current and Retrospective Traditional Victimization

The Illinois Bully Scale (IBS; Espelage and Holt 2001) was used to measure current (i.e., within the last 30 days) traditional bullying victimization. In order to measure retrospective bullying victimization, the same items were presented, but participants were instructed to report about experiences occurring prior to entering college. This measure has been used to measure retrospective reports of peer victimization in previously published studies (Espelage et al. 2016). Only the four victimization items were used in the current study (e.g., “I got hit and pushed by other students” and “Other students called me names”). Items are rated on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 (Never) to 4 (7 or more times). Ratings are summed to create a Victim subscale raw score, which can range from 0 to 16. In previous research, the current victimization items have had strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .88; Espelage and Holt 2001). In the current study, confirmatory factor analysis indicated acceptable fit to the data for both current victimization (χ2 = 5.803, p = .06, RMSEA = .041, CFI = .995, SRMR = .015) and retrospective victimization (χ2 = 31.832, p < .001, CFI = .982, RMSEA = .115, SRMR = .016).

Current and Retrospective Cyber Victimization

The Cyberbullying and Online Aggression Survey Instrument (Hinduja and Patchin 2015) was utilized to measure both current and retrospective reports of cyber victimization. This is a 21-item measure that asks participants to report their experiences of cyberbullying perpetration and victimization in the past 30 days utilizing a 4-point Likert scale (Never, Once, A Few Times, Many Times). Only the 11-item victimization scale was used for the current study. Prior research has shown strong internalizing consistency, with Cronbach alphas ranging from .87 to .94 (Hinduja and Patchin 2015). The same 11 items were also presented in order to assess retrospective cyber victimization. A CFA conducted with the current sample for current cyber victimization initially indicated poor fit to the data (χ2 = 104.909, p < .001, RMSEA = .044, CFI = .877, SRMR = .062). Three items were subsequently deleted due to extreme skew (< 2% of participants indicated experiencing these incidents). Re-examination of model fit with the 7 items indicated improved fit (χ2 = 30.996, p < 0.01, CFI = 0.952, RMSEA = 0.034, SRMR = 0.039). A CFA conducted with the current sample for retrospective cyber victimization initially indicated poor fit to the data (χ2 = 343.555, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.829, RMSEA = 0.088, SRMR = 0.069). Modification indices revealed a relation between three pairs of items: two items measured posting mean comments and spreading rumors online, two items measured being threatened online or through texting, and two items measured posting a hurtful video or web page. Each pair of items were allowed to correlate; model fit then indicated acceptable fit to the data (χ2 = 150.686, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.934, RMSEA = 0.057, SRMR = 0.049).

Depression and Anxiety

The Depression Anxiety and Stress Scale (DASS-21; Henry and Crawford 2005) measures internalizing symptoms related to depression (e.g., “I couldn’t seem to experience any positive feeling at all”), anxiety (e.g., “I found it difficult to relax”), and stress, though stress items were not used in the current study. All items are rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 0 (did not apply to me at all) to 3 (applied to me very much or most of the type). Seven items in each subscale are summed to create the subscale score. Cronbach’s alpha in other research has been strong (Depression = .96 and Anxiety = .95; Page et al. 2007). In the current sample, confirmatory factor analysis indicated good fit to the data for both the Depression (χ2 = 67.86, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.982, RMSEA = 0.061, SRMR = 0.022) and Anxiety (χ2 = 83.02, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.965, RMSEA = 0.069, SRMR = 0.031) scales.

Resilience

The Brief Resilience Scale (BRS; Smith et al. 2008) measures how individuals deal with or bounce back from stressful situations. Three items are positively worded “I tend to bounce back quickly after hard times” and three are negatively worded “I tend to take a long time to get over setbacks in my life”. Participants rate each item on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from Strongly Agree to Strongly Disagree. Negatively worded items are reversed-coded, then all responses are summed to create the total score, which can range from 6 to 30. In other research, internal consistency has ranged from .80 to .91 (Smith et al. 2008). In the current study, CFA indicated initial poor fit (χ2 = 225.23, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.877, RMSEA = 0.151, SRMR = 0.056). Modification indices revealed relations among the three positively worded items and thus, were allowed to covary. Re-examination of model fit indicated good fit (χ2 = 117.44, p < 0.001, CFI = 0.937, RMSEA = 0.122, SRMR = 0.045).

Procedures

Convenience sampling was utilized for participant recruitment. Participants were recruited from a rural Midwestern university through the Psychology Department online subject pool system. Participants were offered course credit for the completion of the survey and all were enrolled in an undergraduate level psychology course. Participants were also recruited via Amazon Mechanical Turk (mTurk). Only mTurk participants who were living in the U.S. and between the ages of 18 and 25 were able to see the survey request. MTurk participants were offered $1.50 for participating, which is on par with other survey-based tasks on mTurk. Responses were anonymous as compensation was provided using the mTurk identification number only. IRB approval was obtained from the 2nd and 3rd author’s respective universities prior to data collection.

Data Analyses

Structural equation modeling (SEM) using Mplus 8.3 (Muthén and Muthén 2019) was utilized for the current study (preliminary analyses conducted with IBM SPSS Statistics 25). Model fit was evaluated by examining chi-square statistics, the root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), the comparative fit index (CFI), and the SRMR. RMSEA and SRMR values below .08 and CFI values above .90 are considered indicative of adequate model fit (Hooper et al. 2008). The robust maximum likelihood (MLR) estimator was utilized to account for data nonnormality. Full information maximum likelihood estimation (FIML) was utilized to account for missing data, which utilizes available participant data to generate population parameter estimates. Missing data ranged from .004% (Retrospective Cyber Victimization) to 9% (Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety). To explore sex differences, multiple group analyses were conducted and chi-square difference testing was employed using the Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference testing (∆ S-B χ2) for model comparisons (Satorra and Bentler 2001). Participants that identified as transgender (n = 12) or non-conforming/prefer not to answer (n = 20) were not included in the multi-group analyses. In order to assess Resilience as a (continuous) moderator, two interaction terms were created between Retrospective Traditional and Cyber Victimization and Resilience.

Results

Descriptive Statistics and Measurement Model

See Tables 2 and 3 for means, standard deviations, and bivariate correlations. Preliminary analyses were conducted to investigate the impact of sex, age, and student status (full-time, part-time, not enrolled) across all variables via a series of one-way ANOVAs. Males reported higher levels of Resilience and Current Traditional Victimization and females reported higher levels of Retrospective Cyber Victimization. In general, younger participants reported higher Current Traditional and Cyber Victimization than older participants. Non-students reported lower levels of Current Traditional Victimization than part-time and full-time students. Full-time students reported higher levels of Resilience and lower levels of Depressive Symptoms than non-students. A MANOVA was also conducted to examine group differences across the Mturk and university samples across all variables. No significant differences were found in Current or Retrospective Cyber Victimization, Depressive Symptoms, Resilience, or Retrospective Traditional Victimization. Significant differences were found with Anxiety (F = 5.22, p = .02, ηp2 = .006) and Current Traditional Victimization (F = 33.58, p < .001, ηp2 = .037), with the Mturk sample reporting lower levels of Anxiety and Current Traditional Victimization. However, given effect sizes were small (i.e., less than 6%; Cohen 1988), samples were pooled for current analyses.

Table 2.

Mean and Standard Deviations of Variables

| Gender | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women | Men | ||||||||

| M | SD | N | M | SD | N | M | SD | N | |

|

Retrospective TV range: 0–16 |

4.58 | 4.49 | 742 | 4.10 | 4.48 | 368 | 4.45 | 4.51 | 1132 |

|

Retrospective CV range: 0–30 |

2.82 | 4.75 | 747 | 1.74 | 3.82 | 368 | 2.49 | 4.50 | 1137 |

|

Current TV range: 0–16 |

1.13 | 2.39 | 742 | 1.46 | 2.69 | 368 | 1.23 | 2.52 | 1132 |

|

Current CV range: 0–30 |

0.54 | 2.31 | 687 | 0.48 | 2.33 | 350 | 0.52 | 2.32 | 1055 |

|

Depressive Symptoms range: 0–21 |

6.28 | 5.74 | 683 | 6.04 | 5.24 | 340 | 6.22 | 5.56 | 1042 |

|

Anxiety range: 0–21 |

5.48 | 4.98 | 683 | 5.21 | 4.67 | 340 | 5.40 | 4.87 | 1042 |

|

Resilience range: 6–30 |

18.78 | 5.28 | 699 | 20.70 | 4.79 | 336 | 19.37 | 5.22 | 1055 |

Note. TV = Traditional Victimization; CV = Cyber Victimization. Reported ranges are based on sample

Table 3.

Bivariate Correlations Among Total Sample

| Variables | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Retrospective TV | 1 | .33** | .34** | .20** | .24** | .24** | −.17** |

| 2. Retrospective CV | 1 | .29** | .36** | .26** | .28** | −.15** | |

| 3. Current TV | 1 | .43** | .16** | .22** | −.09** | ||

| 4. Current CV | 1 | .16** | .21** | −.041 | |||

| 5. Depressive Symptoms | 1 | .70** | −.52** | ||||

| 6. Anxiety | 1 | −.40** | |||||

| 7. Resilience | 1 |

Note. TV = Traditional Victimization; CV = Cyber Victimization

**p < .01

Data were first fit to the measurement model, which included all latent variables (i.e., Retrospective and Current Traditional and Cyber Victimization, Depressive Symptoms, Anxiety and Resilience). Model fit indices indicated acceptable fit to the data, χ2 (919) = 2288.96, p < .001, CFI = .924, RMSEA = .036, SRMR = .048. Standardized factor loadings for Retrospective Traditional Victimization ranged from .49 to .97, Current Traditional Victimization .54 to .91, Retrospective Cyber Victimization .57 to .74, Current Cyber Victimization .58 to .83, Depressive Symptoms .58 to .85, Anxiety .42 to .81, and Resilience .54 to .84.

Retrospective and Current Peer Victimization

To examine the first research question, data were fit to the model depicted in Fig. 2. All fit indices were within their respective recommended ranges for acceptable model fit (χ2 [312] = 938.43, p < .001, RMSEA = .042, CFI = .910, SRMR = .062). Retrospective Traditional (β = .25, B = .14, p < .001) and Cyber Victimization (β = .23, B = .28, p < .001) were significantly associated with Current Traditional Victimization (R2 = .23, p < .001). Retrospective Cyber Victimization (β = .43, B = .22, p < .001), but not Retrospective Traditional Victimization (β = .05, B = .01, p = .17), was significantly associated with Current Cyber Victimization (R2 = .21, p = .002). To explore sex differences, the Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference test was utilized to compare the constrained and unconstrained models across sex. The chi-square difference between the unconstrained and constrained model was nonsignificant (∆S-B χ2 = 2.66, p = 0.62), indicating there were no significant sex differences among the paths.

Fig. 2.

Standardized estimates of the relations among Retrospective Traditional and Cyber Victimization and Current Traditional and Cyber Victimization. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05

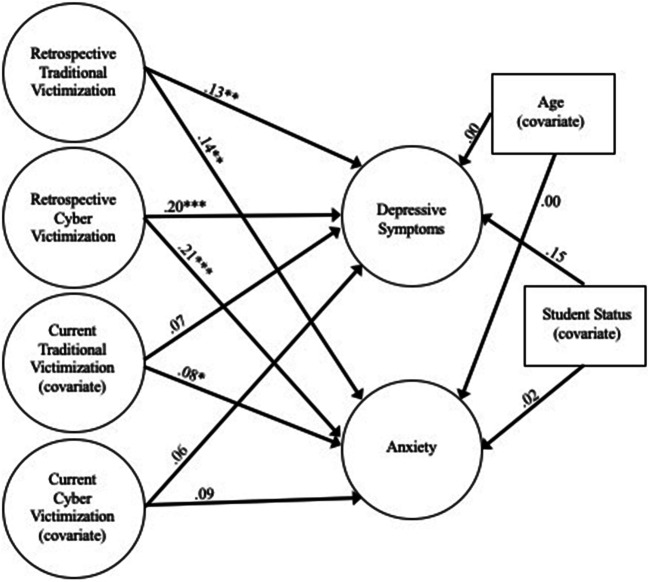

Retrospective Peer Victimization and Current Internalizing Problems

To examine the second research question, data were fit to the model in Fig. 3. All fit indices were within their respective recommended ranges for acceptable model fit (χ2 [312] = 2001.26, p < .001, RMSEA = .038, CFI = .917, SRMR = .054). Retrospective Traditional Victimization (β = .13, B = .07, p = .001) and Retrospective Cyber Victimization (β = .20, B = .23, p < .001) were positively and significantly associated with Depression. Retrospective Traditional Victimization (β = .14, B = .04, p = .001) and Retrospective Cyber Victimization (β = .21, B = .14, p < .001) were also positively and significantly associated with Anxiety. Sex differences were also examined utilizing crossgroup equality constraints. The Satorra-Bentler scaled chi-square difference test was nonsignificant (∆S-B χ2 = 8.53, p = 0.08), indicating the unconstrained model did not fit significantly better than the constrained model (i.e., path estimates were similar across sex).

Fig. 3.

Standardized estimates of the relations among Retrospective Traditional and Cyber Victimization and Depressive Symptoms and Anxiety. ***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05

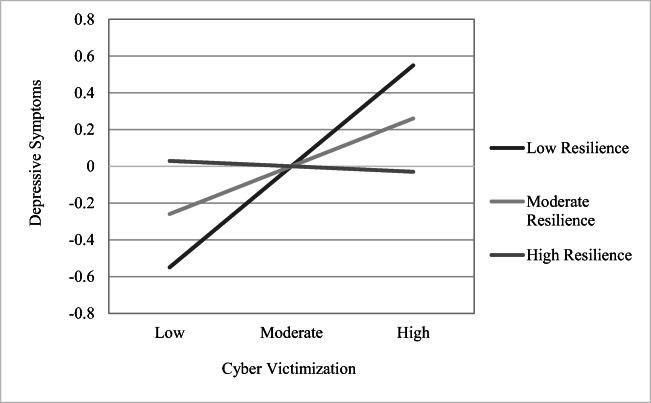

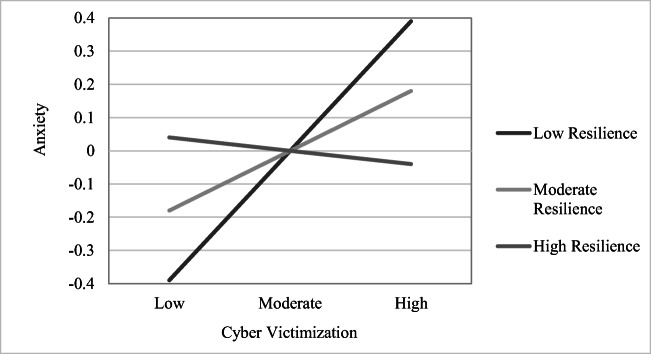

Resilience as a Moderator

Two interaction terms were included in the model (Retrospective Traditional Victimization X Resilience and Retrospective Cyber Victimization X Resilience) in order to examine resilience as a moderator in the relation between retrospective reports of peer victimization and internalizing problems. Retrospective Traditional and Cyber Victimization, Resilience, and the two interaction terms were included as exogenous variables, Depressive Symptoms, and Anxiety were included as endogenous variables, and Current Traditional and Cyber Victimization, Student Status, and Age were included as covariates. Resilience was negatively and significantly associated with depressive symptoms (β = −.54, p < .001) and the Resilience X Retrospective Cyber Victimization interaction term was significant (β = −.08, p = .01); however, the Resilience X Retrospective Traditional Victimization interaction was nonsignificant (β = −.01, p = .81). Similarly, Resilience was significantly associated with Anxiety (β = −.47, p < .001) and the Resilience X Retrospective Cyber Victimization interaction term was significant (β = −.11, p = .02); however, the Resilience X Retrospective Traditional Victimization interaction was nonsignificant (β = .03, p = .47) (See Table 4). Post hoc testing of the significant two-way interaction involved testing the significance of simple slopes at one standard deviation above and below the mean of Resilience. Regarding Depressive Symptoms, the Cyber Victimization X Resilience unstandardized simple slopes for low levels of Resilience was significant (.18, p = .001), but was not significant at moderate (.09, p = .08) and high (−.01, p = .88) levels of Resilience (see Fig. 4). Regarding Anxiety, the Cyber Victimization X Resilience unstandardized simple slopes for low levels of Resilience was significant (.13, p = .001), but was not significant at moderate (.06, p = .08) and high (−.01, p = .81) levels of Resilience (see Fig. 5).

Table 4.

Standardized and Unstandardized Coefficients, 95% Confidence Intervals, Standard Errors, and p Values for Resilience as a Moderator in the Relation Between Retrospective Victimization and Current Internalizing Problems

| Depressive Symptoms | Anxiety | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ß | B | SE B | Lower | Upper | ß | B | SE B | Lower | Upper | |

| Retrospective TV | .06 | .03 | .02 | −.00 | .07 | .08 | .03* | .01 | .01 | .05 |

| Retrospective CV | .08 | .09 | .05 | −.01 | .18 | .09 | .06 | .03 | −.01 | .14 |

| Resilience | −.55 | −.39*** | .03 | −.44 | −.34 | −.47 | −.19*** | .02 | −.54 | −.16 |

| Resilience X TV | −.01 | −.00 | .02 | −.04 | .03 | .03 | .01 | .01 | −.04 | .04 |

| Resilience X CV | −.08 | −.10** | .04 | −.17 | −.02 | −.11 | −.07* | .03 | −.19 | .00 |

| Current TV (covariate) | .04 | .04 | .04 | −.03 | .10 | .06 | .03 | .02 | −.02 | .08 |

| Current CV (covariate) | .07 | .17 | .09 | .00 | .34 | .10 | .13 | .07 | .01 | .30 |

| Age (covariate) | .00 | .00 | .01 | −.02 | .02 | −.00 | .00 | .01 | −.03 | .02 |

| Student Status (covariate) | .07 | .07 | .04 | −.00 | .13 | −.04 | −.02 | .02 | −.15 | .03 |

Note. TV = Traditional Victimization; CV = Cyber Victimization

***p < .001, **p < .01, *p < .05

Fig. 4.

The Interaction of Resilience in the Relation Between Cyber Victimization and Depressive Symptoms

Fig. 5.

The Interaction of Resilience in the Relation Between Cyber Victimization and Anxiety

Discussion

The goal of the current study was to explore associations between retrospective and current experiences of traditional and cyber victimization and internalizing symptoms among young adults, as well as the moderating effect of resilience through the lens of the social-ecological diathesis stress model. Previous research suggests that peer victimization occurring in childhood or adolescence may continue to occur into adulthood (Adams and Lawrence 2011; Felix et al. 2019) and can have a lasting impact on mental health according to both longitudinal designs (Hill et al. 2017; Lereya et al. 2015) and retrospective accounts (Espelage et al. 2016; Reid et al. 2016). We sought to add to this literature on peer victimization in young adulthood in several ways. First, we explored sex differences in the relations between retrospective victimization and current victimization, as well as internalizing problems. Although prior research has found sex differences in outcomes of peer victimization, no known study has examined sex differences in the relation between retrospective accounts of victimization, revictimization, and internalizing problems. Further, we examined the relation between retrospective accounts of peer victimization and current internalizing problems, while controlling for the effects of current victimization. Finally, we explored the moderating effect of perceptions of resilience on the association between retrospective victimization and internalizing difficulties. These study aims were investigated via structural equation modeling—allowing us to account for measurement error—with a large geographically diverse sample of young adults.

Although not a primary aim of the current study, preliminary analyses indicated important differences in current and retrospective peer victimization across sex, age, and student status. Males reported higher levels of current traditional victimization, while females reported higher levels of retrospective cyber victimization. This is consistent with prior research that has examined sex differences in current victimization, with males reporting higher levels of certain aspects of traditional victimization (i.e., physical victimization; Barzilay et al. 2017) and females reporting higher cyber victimization (Kann et al. 2018). Younger participants reported higher levels of current traditional and cyber victimization—but not retrospective victimization—suggesting that victimization may decrease as adolescents and young adults mature. Interestingly, full-time and part-time college students reported higher levels of current traditional victimization, but not cyber victimization, than students not enrolled in college. College students may be more likely to be with similarly aged peers, especially in larger groups (e.g., dorm rooms or other areas on campus) with minimal supervision and thus more at risk for traditional victimization. Of note, full-time students reported higher levels of resilience and lower levels of depressive symptoms than students not enrolled in college, suggesting that there may be important differences between young adult students and non-students and thus an important area for future research.

Retrospective and Current Peer Victimization

As predicted, retrospective reports of traditional victimization were positively and significantly associated with current experiences of traditional victimization, but not current cyber victimization. In other words, higher rates of previous face-to-face victimization (i.e., physical, verbal, or social victimization) were related to higher rates of current face-to-face victimization, but not current victimization via technology. However, retrospective reports of cyber victimization were positively and significantly associated with both current cyber and traditional victimization, which aligns with our hypothesis (Adams and Lawrence 2011; Felix et al. 2019). These relations were the same for both males and females. Many adolescents who are victimized face-to-face are often also victimized through electronic means (Mitchell et al. 2016). Based on the results of the current study, this may not be true when looking over time. That is, experiencing traditional victimization in K-12 may not make one more likely to experience cyber victimization after high school. One reason for this could be due to individuals’ use of technology—perhaps these individuals do not utilize social media or engage with peers through electronic means (both as adolescents and young adults) and thus are less likely to experience cyber victimization. On the other hand, experiencing cyber victimization in K-12 was positively associated with current experiences of both traditional and cyber victimization, which is consistent with prior research that has found a strong overlap between these types of peer victimization.

Retrospective Victimization and Internalizing Problems

As anticipated, we found that retrospective reports of both traditional and cyber victimization were associated with depression and anxiety symptoms, above and beyond current victimization experiences. This is consistent with prior studies examining the relations between traditional and cyber victimization and mental health both in longitudinal designs (Hill et al. 2017; Lereya et al. 2015) and retrospective accounts (Espelage et al. 2016; Reid et al. 2016). Findings from the current study suggest that merely remembering or recalling experiences of peer victimization during childhood or adolescence has negative implications for the mental health of young adults beyond any victimization they may be currently experiencing. Of note, findings from bivariate correlations suggest that current peer victimization is negatively associated with depressive symptoms and anxiety; however, both current traditional and cyber victimization were not significantly related to depressive symptoms and only current traditional victimization was significantly associated with anxiety in the model. This is an important finding which provides evidence for the lasting impact that bullying during K-12 can have on young adults.

Counter to our hypotheses, there were no sex differences found in the relation between retrospective victimization and current internalizing symptoms. Previous research found that the association between victimization and internalizing difficulties was stronger for females (Espelage et al. 2016; Iyer-Eimerbrink et al. 2015). Our hypothesis that there would be sex differences was based on research comparing current victimization and current internalizing difficulties. Though additional research is needed, it is possible that there are not sex differences when examining the link between retrospective victimization and current symptoms.

Resiliency as a Moderator

The third research question was, is resiliency a moderator in the relation between retrospective victimization and current depression and anxiety? In line with predictions (Hinduja and Patchin 2017; Víllora et al. 2020), resilience was a moderator for cyber victimization only, but not traditional victimization. In follow-up analyses, we found that when resilience was low, there was a positive relation between cyber victimization and both anxiety and depressive symptoms; however, when resilience was moderate or high there was not a significant relation between cyber victimization and these internalizing symptoms. These findings suggest that perceptions of the ability to deal with or bounce back from stressful situations can protect individuals from long-term internalizing difficulties associated with cyber victimization. Based on the current findings, the same cannot be said for past traditional victimization. Namely, perceptions of resilience was not a significant moderator in the association between retrospective traditional victimization and either depressive or anxious symptoms. In other words, the positive relation between retrospective traditional victimization and internalizing symptoms is similar across low and high levels of resiliency. Some scholars have speculated that traditional victimization may be associated with worse outcomes compared to cyber victimization—or at least not be as harmful as previously thought—potentially due to higher prevalence rates of traditional victimization and many studies examining cyber victimization do not take traditional victimization into account (Olweus and Limber 2018). In their qualitative study examining adolescents’ perceptions of victimization, Corby et al. (2014) found that many students reported traditional victimization to be more harmful, in particular physical and verbal bullying, and that seeing the aggressor’s body language and facial expressions (e.g., smile) made them feel worse. Thus, it could be that perceptions of resiliency are not a strong enough buffer against negative outcomes of traditional victimization. It also could be that experiences of traditional victimization impact one’s perceptions of their resiliency; thus, an important area for future research would be to examine resilience as a mediator.

Limitations, Future Directions, and Implication

Several limitations of the current study should be noted. All data were collected via self-report and although the online format of the survey allowed the participants to be anonymous, self-report data can be subject to social desirability bias. Prior research has found that retrospective accounts of childhood victimization are relatively accurate (Rivers 2001); however, retrospective reports are also subject to biased or inaccurate recall. We utilized a scale that asked participants to recall specific experiences of bullying (e.g., being hit) rather than asking about vague events which may reduce potential bias (Hardt and Rutter 2004). Further, we cannot make causal statements given the cross-sectional design; longitudinal data are needed in order to determine directionality of relations and to reduce bias of retrospective accounts of bullying. Two different recruiting methods were utilized (i.e., participants were recruited via university and mTurk); however, these methods diversified our sample and increased the external validity of our findings. Further, it allowed us to overcome a major limitation of prior bullying research by including young adults enrolled and not enrolled in college classes. This is particularly important for bullying research as young adults that experienced high levels of childhood bullying may not have entered college due to challenges associated with bullying (e.g., mental health, social challenges). Finally, there are many other personal history factors that could influence the relations we examined in the current study, such as past social experiences, mental health disorders, or counseling and other treatment experiences.

Despite these limitations, the current study addresses gaps in the literature and is one of the first to examine potential moderators (i.e., sex differences, resiliency) in the relation between retrospective and current reports of victimization and mental health among college students. Further research may wish to examine other demographic variables that are likely important (e.g., sexual orientation), as well as external (e.g., university climate/supports, family and peer social support) and internal (e.g., personality types, coping strategies) factors that may aid in reducing the risk of revictimization and subsequent mental health problems among college students and young adults. Further, bias-based bullying (bullying motivated by a target’s actual or perceived identity including race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, religious beliefs) has been found to have more negative effects compared to non-biased-based bullying (Mulvey et al. 2018; Russell et al. 2012). Thus, examining the relation between revictimization and mental health problems among marginalized populations, including sexual and gender minority students and students of color, will be important for future research. Examining different types of traditional victimization may also be important, as some types (e.g., physical) may be more detrimental long-term than others. Finally, it may be important to examine perceptions of resiliency as a mediator—instead of a moderator—as experiences of victimization may influence one’s perceptions of their “ability to bounce back” especially if victimization is chronic and severe. In the current study, resiliency was examined as a moderator (i.e., buffer) as this aligns with our aim to examine protective factors to reduce risk of negative outcomes associated with peer victimization and the diathesis-stress model.

Findings from the current study have several important implications for practitioners working with adolescent and young adult populations. First, college counseling centers and other practitioners working with college students and young adults may wish to include screening for or asking about prior victimization experiences as it relates to current difficulties or distress. Work settings (e.g., companies) that employ young adults should be aware of the long-term impact of bullying and should offer support for employee’s mental health (e.g., through employee assistance programs) with an awareness of the implications of past victimization and potential revictimization among employees. Finally, perceptions of resiliency buffered participants from more negative outcomes of cyber victimization in the current study; thus, it may be important to teach adolescents and young adults ways to promote these perceptions, especially for those experiencing chronic and severe cyber victimization.

The current study addressed several gaps in the literature on peer victimization among young adults by examining the associations among retrospective and current peer victimization, internalizing problems, and perceptions of resilience among a large sample of adults through the lens of the social-ecological diathesis-stress model. Further longitudinal studies are needed to better understand the associations among revictimization and mental health, and potential buffering mechanisms, among young adults.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

On behalf of all authors, the corresponding author states that there is no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Abela, J., & Hankin, B. L. (2008). Cognitive vulnerability to depression in children and adolescents: A developmental psychopathology perspective. In J.R. Abela & B.L. Hankin (Eds.), Handbook of Depression in Children and Adolescents (pp. 35–78). Guilford Press.

- Adams FD, Lawrence GT. Bullying victims: The effects last into college. American Secondary Education. 2011;40:4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. New York: Routledge Academic; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Corby E, Campbell MA, Spears B, Slee P, Butler D, Kift S. Students’ perceptions of their own victimization: A youth voice perspective. Journal of School Violence. 2014;15:322–342. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2014.996719. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barzilay S, Klomek AB, Apter A, Carli V, Wasserman C, Hadlaczky G, et al. Bullying victimization and suicide ideation and behavior among adolescents in Europe: A 10-country study. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2017;61:179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. The ecology of human development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Holt M. Bullying and victimization during early adolescence: Peer influences and psychosocial correlates. Journal of Emotional Abuse. 2001;2:123–142. doi: 10.1300/J135v02n02_08. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Hong JS, Mebane S. Recollections of childhood bullying and multiple forms of victimization: Correlates with psychological functioning among college students. Social Psychology of Education. 2016;19:715–728. doi: 10.1007/s11218-016-9352-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Espelage DL, Low SK, Jimerson SR. Understanding school climate, aggression, peer victimization, and bully perpetration: Contemporary science, practice, and policy. School Psychology Quarterly. 2014;29:233–237. doi: 10.1037/spq0000090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felix ED, Holt MK, Nylund-Gibson K, Grimm RP, Espelage DL, Green JG. Associations between childhood peer victimization and aggression and subsequent victimization and aggression at college. Psychology of Violence. 2019;9:451–460. doi: 10.1037/vio0000193. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Forbes S, Fikretoglu D. Building resilience: The conceptual basis and research evidence for resilience training programs. Review of General Psychology. 2018;22:452–468. doi: 10.1037/gpr0000152. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fredrick SS, Demaray MK. Peer victimization and suicidal ideation: The role of gender and depression in a school-based sample. Journal of School Psychology. 2018;67:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2018.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gladden, R. M., Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., Hamburger, M. E., & Lumpkin, C. D. (2014). Bullying surveillance among youth: Uniform definitions for public health and recommended data elements, version 1.0. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Injury Prevention and Control, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and U.S. Department of Education.

- Hardt J, Rutter M. Validity of adult retrospective reports of adverse childhood experiences: Review of the evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2004;45:260–273. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00218.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry JD, Crawford JR. The short-form version of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS-21): Construct validity and normative data in a large non-clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2005;44:227–239. doi: 10.1348/014466505X29657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill RM, Mellick W, Temple JR, Sharp C. The role of bullying in depressive symptoms from adolescence to emerging adulthood: A growth mixture model. Journal of Affective Disorders. 2017;207:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Cultivating youth resilience to prevent bullying and cyberbullying victimization. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2017;73:51–62. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.09.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hinduja S, Patchin JW. Bullying beyond the schoolyard: Preventing and responding to cyberbullying. 2. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hooper D, Coughlan J, Mullen M. Structural equation modelling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods. 2008;6:53–60. doi: 10.21427/D7CF7R. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huang FL, Cornell DG. School teasing and bullying after the presidential election. Educational Researcher. 2019;48:69–83. doi: 10.3102/0013189X18820291. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer-Eimerbrink PA, Scielzo SA, Jensen-Campbell LA. The impact of social and relational victimization on depression, anxiety, and loneliness: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Bullying and Social Aggression. 2015;1:1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Kann, L., MacManus, T., Harris, W. A., Shanklin, S. L., Flint, K. H., Queen, B., . . . Ethier, K. A. (2018). Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance—United States, 2017. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/yrbs/pdf/2017/ss6708.pdf [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Lazarus RS. From psychological stress to the emotions: A history of changing outlooks. Annual Review of Psychology. 1993;44:1–21. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.44.1.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lereya ST, Copeland WE, Costello EJ, Wolke D. Adult mental health consequences of peer bullying and maltreatment in childhood: Two cohorts in two countries. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2:524–531. doi: 10.1016/52215-0266(15)00165-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, Becker B. The construct of resilience: A critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Development. 2000;71:543–562. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KJ, Jones LM, Turner HA, Shattuck A, Wolak J. The role of technology in peer harassment: Does it amplify harm for youth? Psychology of Violence. 2016;6:193–204. doi: 10.1037/a0039317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Modecki KL, Minchin J, Harbaugh AG, Guerra NG, Runions KC. Bullying prevalence across contexts: A meta-analysis measuring cyber and traditional bullying. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2014;55:602–611. doi: 10.1016/j.adohealth.2014.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore SE, Norman RE, Suetani S, Thomas HJ, Sly PD, Scott JG. Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Psychiatry. 2017;7:60–76. doi: 10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulvey KL, Hoffman AJ, Gönültaş S, Hope EC, Cooper SM. Understanding experiences with bullying and bias-based bullying: What matters and for whom? Psychology of Violence. 2018;8(6):702–711. doi: 10.1037/vio0000206. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2019). Mplus User's Guide (Seventh ed.). Los Angeles: Muthén & Muthén.

- Olweus D, Limber SP. Some problems with cyberbullying research. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2018;19:139–143. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page AC, Hooke GR, Morrison DL. Psychometric properties of the depression anxiety stress scales (DASS) in depressed clinical samples. British Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2007;46:283–297. doi: 10.1348/014466506X158996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reid GM, Holt MK, Bowman CE, Espelage DL, Green JG. Perceived social support and mental health among first-year college students with histories of bullying victimization. Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2016;25:3331–3341. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0477-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rivers I. Retrospective reports of school bullying: Stability of recall and its implications for research. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 2001;19:129–142. doi: 10.1348/026151001166001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell ST, Sinclair KO, Poteat VP, Koenig BW. Adolescent health and harassment based on discriminatory bias. American Journal of Public Health. 2012;102:493–495. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2011.300430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Satorra A, Bentler PM. A scale difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika. 2001;66:507–514. doi: 10.1007/BF02296192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schenk AM, Fremouw WJ. Prevalence, psychological impact, and coping of cyberbully victims among college students. Journal of School Violence. 2012;11:21–37. doi: 10.1080/15388220.2011.630310. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider SK, O’Donnell L, Smith E. Trends in cyberbullying and school bullying victimization in a regional census of high school students, 2006-2012. Journal of School Health. 2015;85:611–620. doi: 10.1111/josh.12290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkie EM, Kota R, Chan Y, Moreno M. Cyberbullying, depression, and problem alcohol use in female college students: A multisite study. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking. 2015;18:79–86. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2014.0371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith BW, Dalen J, Wiggins K, Tooley E, Christopher P, Bernard J. The brief resilience scale: Assessing the ability to bounce back. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2008;15:194–200. doi: 10.1080/10705500802222972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swearer SM, Hymel S. Understanding the psychology of bullying: Moving toward a social-ecological diathesis-stress model. American Psychologist. 2015;70:344–353. doi: 10.1037/a0038929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tennant JE, Demaray MK, Coyle S, Malecki CK. The dangers of the web. Cybervictimization, depression, and social support in college students. Computers in Human Behavior. 2015;50:348–357. doi: 10.1016/j.chb.2015.04.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Troop-Gordon W. Peer victimization in adolescence: The nature, progression, and consequences of being bullied within a developmental context. Journal of Adolescence. 2017;55:116–128. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucker CJ, Finkelhor D, Turner H. Family predictors of sibling versus peer victimization. Journal of Family Psychology. 2020;34:186–195. doi: 10.1037/fam0000592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Víllora B, Larrañaga E, Yubero S, Alfaro A, Navarro R. Relations among poly-bullying victimization, subjective well-being and resilience in a sample of late adolescents. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2020;17:590–602. doi: 10.3390/ijerph17020590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu J, Yu C, Zhang W, Bao Z, Jiang Y, Chen Y, Zhen S. Peer victimization, deviant peer affiliation and impulsivity: Predicting adolescent problem behaviors. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2017;58:39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2016.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]