Abstract

Histamine-producing bacteria (HPB) produce histamine from histidine contained in food through the action of histidine decarboxylase. To identify HPB isolated from food, it is necessary to detect histamine produced by the bacteria. In this study, we concurrently identified HPB and detected histamine by matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry. After 24 h of incubation, 30 of 34 bacterial strains were correctly identified. Histamine was detected in all HPB cultured on Niven’s medium, and 94% of HPB cultured in histidine broth, except for two strains with low histamine production. This method may greatly simplify the procedure and reduce the time required to identify HPB.

Keywords: Bacterial identification, Histamine, Histamine food poisoning, MALDI-TOF MS, Histamine-producing bacteria

Introduction

Histamine food poisoning is caused by the consumption of fish and fish products contaminated with histamine-producing bacteria (HPB), which possess histidine decarboxylase activity. Upon isolation of HPB from food, histamine production by the bacteria must be checked. Various methods have been reported for histamine detection, including Niven’s medium (Niven et al. 1981), thin-layer chromatography, and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC). To identify HPB, 16S rRNA gene sequencing and/or biochemical tests must be performed after histamine detection. HPB are identified using different methods and types of equipment, making this analysis complicated and costly. Recently, MALDI-TOF MS, which is rapid and inexpensive, has frequently been used for bacterial identification. As this method identifies bacteria by matching with mass spectral patterns registered in a library, mass spectra of known species are required for species identification. However, if the mass spectrum matches that of a known substance, it is possible to identify not only bacteria but also unknown substances. Although some studies used matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry (MALDI-TOF MS) to identify HPB strains (Hu et al. 2015; Velut et al. 2019), few have focused on performing histamine detection and bacterial identification simultaneously. Thus, we investigated the potential efficacy of using MALDI-TOF MS for histamine detection of isolated HPB strains and fish samples that cause histamine food poisoning.

Materials and methods

Bacterial strain isolation

Saury, mackerel, swordfish, horse mackerel, and yellowtail were purchased from a market in Tokyo and transported to the laboratory under refrigeration. A tenfold dilution of the fish weighing 25 g each, was prepared in 225 mL phosphate buffer; thereafter, 1 mL of each diluted sample was inoculated into Niven's medium and cultured at 20 ± 1 °C for 72 h or 35 ± 1 °C for 48 h. The resulting colonies were isolated and cultured in Niven’s medium at 35 ± 1 °C for 24 h. DNA was extracted from the culture using Lyse and Go PCR Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA), and the template DNA was amplified using hdc-specific primers (Takahashi et al. 2003). Thirty-one colonies harboring hdc and 15 non-harboring colonies were selected and designated as HPB and non-HPB, respectively. In total, 49 strains, including three histamine-producing strains purchased from the NBRC Culture Catalogue, were used as test strains.

Food samples

Three samples of sardine fish balls that caused histamine food poisoning and one sample of histamine-free dolphinfish were used. Proteins were extracted by adding and mixing 10 mL of 20% trichloroacetic acid solution to each 10 g sample of the three sardine fish balls and one histamine-free dolphinfish. Each sample was filtered, and distilled water was added to the extracts to a final volume of 100 mL for use as the test solutions. A fixed volume of the internal standard (0.50 mL) and test solutions (1.0 mL) was prepared and quantified by HPLC (JASCO Corp., Tokyo, Japan) after fluorescent labeling with dansyl chloride (Akiyama et al. 2020; Nagayama et al. 1985). The histamine levels in the sardines (sardine-1, sardine-2, and sardine-3) were 160, 170, and 190 mg/100 g, respectively.

Bacterial identification by MALDI-TOF MS

The bacterial strains were incubated on agar plates or in broth. The isolated HPB were inoculated in Niven's medium and Niven's medium modified histidine broth (yeast extract 2.5 g, d-glucose 1.5 g, l-histidine hydrochloride monohydrate 10 g, sodium chloride 20 g in 1 L of purified water, pH adjusted to 5.8), and incubated at 35 ± 1 °C for 24 h. Ten microliters of the pre-culture in histidine broth was inoculated into another 5 mL of histidine broth and incubated at 35 ± 1 °C for 24 h, followed by centrifugation at 13,980×g for 15 min. Each colony on Niven's medium and precipitates in the broth was applied to a target plate, and 1 μL of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid dissolved in a solution containing 50% acetonitrile, 47.5% water, and 2.5% trifluoroacetic acid (Merck, Darmstadt, Germany) was added and dried.

Bacterial identification was performed using a Biotyper (Bruker Daltonik GmbH, Bremen, Germany) and MBT Compass ver. 4.1. Mass spectra were collected using FlexControl 3.4 in the mass range of 2000–20,000 Da. According to the cutoffs proposed by the manufacturers, the identification criteria were as follows: scores of ≥ 2.00 indicated species level, scores of 1.70–1.99 indicated genus level, and scores < 1.70 were considered as unidentifiable. When two species showed scores ≥ 2.00 for the top five strains in the results, the name of each species was listed.

Bacterial identification by DNA sequence analysis

PCR was carried out using DNA extracted from the 31 HPB strains isolated and the universal primers 20F and 802R (Jiranuntipon et al. 2009) to amplify 500 bp upstream of the 16S rRNA gene. After initial denaturation (1 min at 94 °C), 35 cycles (94 °C, 30 s; 55 °C, 30 s; 72 °C, 30 s) of amplifications were performed, followed by a single final extension (7 min at 72 °C). DNA fragments were sequenced using ABI PRISM 3130 automatic sequencing system (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA, USA). Raoultella species were confirmed by nucleotide sequence analysis of the β-lactamase gene (bla) (Walckenaer et al. 2004). The amplified DNA was directly sequenced, and the partial 16S rRNA and bla sequences were aligned using the MEGA6 program (Tamura et al. 2013) and identified using the BLAST database (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi).

Histamine quantification of HPB strains

Histidine broth used for HPB culture was centrifuged at 13,980×g for 15 min, and the amount of histamine in the supernatant was measured with Check Color Histamine (Kikkoman Co., Noda, Japan).

Sample preparation for histamine detection by MALDI-TOF MS

Bacterial strains

The histamine detection rate was compared between the agar plate and broth. In Niven’s medium, the strains were streaked in an 8 mm grid pattern on the medium and cultured at 35 ± 1 °C for 24 h. The inside of the grid was cut into a circle of 6 mm diameter and placed in a 2 mL vial. In histidine broth culture, 500 µL of the supernatant after centrifugation and 0.13 g of sodium chloride were added into a vial, followed by addition of 500 µL of LC/MS-grade acetonitrile (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation, Osaka, Japan) to each vial. The vials were mixed for 3 min, and then 1 μL of the supernatant and 1 μL of α-cyano-4-hydroxycinnamic acid reagent dissolved in 50% acetonitrile, 49.9% water, and 0.1% trifluoroacetic acid were mixed and applied to a target plate, which was dried.

Food samples

To each vial, 500 µL of test solution for extraction by HPLC and 500 µL of acetonitrile were added to each vial and mixed for 3 min. Each supernatant (50 μL) was purified in a ZipTip C18 (Merck Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol, and 1 μL of each extract was tested as described in ‘Bacterial strains’.

Histamine detection by MALDI-TOF MS

Spectral analysis

The Biotyper was calibrated with an MBT-STAR-ACS (Bruker Daltonik GmbH) in the range of 100–700 Da for mass spectrometry. Each spectrum was manually integrated using 400 laser shots, which were obtained in 10 different areas per sample spot. The mass spectra were analyzed qualitatively using FlexAnalysis software (Bruker Daltonik GmbH). A histamine standard solution (Fujifilm Wako Pure Chemical Corporation) was diluted to 10 ppm with acetonitrile, which was detected at 112 Da as a characteristic peak of protonated ions [M + H]+. Five differential spots were analyzed three times to test their reproducibility; the measurement error was a width of 0.2 m/z. If the signal-to-noise ratio of the mass spectrum was 10 or more, and the mass spectral range of protonated histamine as [M + H]+ was found to be within 112 ± 0.5 m/z, the sample was considered as positive for histamine. A characteristic peak of sodium adducts as [M + Na]+ from the histamine standard solution was detected at 134 Da in the same manner. If a peak of [M + Na]+ was observed at 134 ± 0.5 m/z, in addition to the above [M + H]+ peaks, the sample was similarly determined as positive for histamine.

Limit of detection (LOD) in strains

Histamine at seven concentrations (500, 250, 200, 100, 50, 40, and 20 µg/mL) was added to non-HPB cultured in histidine broth, and then analyzed to investigate the LOD by MALDI-TOF MS. Three spots of each concentration of the samples were measured, and the LOD was defined as the concentration at which the signal-to-noise ratio was ≥ 3 for all spots.

Results and discussion

Bacterial identification

The following strains of HPB isolated were identified at the species level by MALDI-TOF MS: 10 strains of Morganella morganii, 2 strains of Photobacterium damselae, 9 strains of Pluralibacter pyrinus, and 6 strains of Raoultella ornithinolytica. These identifications were consistent with the results of 16S rDNA and bla sequence analyses. Additionally, two strains of Pantoea were identified at the genus level, as Pantoea anthophila was not included in the standard Biotyper reference library. R. ornithinolytica was identified by MALDI-TOF MS, whereas R. planticola was not (Table 1). This was predicted to be related to the low number of R. planticola reference samples, and thus we increased the number of strains in the in-house library.

Table 1.

Histamine production and identification of histamine-producing bacteria by MALDI-TOF MS and sequence analysis

| Strain No. | Histamine production (µg/mL) | Bacteral identification | Histamine detection by MALDI-TOF MS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MALDI-TOF MS | 16S rRNA snd β-lactamase gene sequence analysis | Niven's medium | Histidine broth | ||

| ATCC13048 | 6430 | Enterobacter aerogenes | + | + | |

| Klebsiella aerogenes | |||||

| ATCC25830 | 6110 | Morganella morganii | + | + | |

| Morganella morganii | |||||

| h1435-010 | 5370 | Morganella morganii | Morganella morganii | + | + |

| h1420-007 | 5580 | Morganella morganii | Morganella morganii | + | + |

| h1420-014 | 4850 | Morganella morganii | Morganella morganii | + | + |

| h1420-017 | 5670 | Morganella morganii | Morganella morganii | + | + |

| h1420-018 | 5060 | Morganella morganii | Morganella morganii | + | + |

| h1420-019 | 4730 | Morganella morganii | Morganella morganii | + | + |

| h1420-031 | 4610 | Morganella morganii | Morganella morganii | + | + |

| h1420-033 | 4270 | Morganella morganii | Morganella morganii | + | + |

| h1420-037 | 3670 | Morganella morganii | Morganella morganii | + | + |

| h1420-040 | 5030 | Morganella morganii | Morganella morganii | + | + |

| h1435-030 | 4180 | Pantoea agglomerans | Pantoea anthophila* | + | + |

| h1420-022 | 6440 | Pantoea agglomerans | Pantoea anthophila* | + | + |

| ATCC33539 | 2960 | Photobacterium damselae | + | + | |

| Photobacterium damselae | |||||

| h1420-002 | 1130 | Photobacterium damselae | Photobacterium damselae | + | + |

| h1420-003 | 4000 | Photobacterium damselae | Photobacterium damselae | + | + |

| h1435-038 | 6050 | Pluralibacter pyrinus | Pluralibacter pyrinus | + | + |

| hy206-1 | 5 | Pluralibacter pyrinus | Pluralibacter pyrinus | + | − |

| hy210 | 7 | Pluralibacter pyrinus | Pluralibacter pyrinus | + | − |

| h1420-021 | 2940 | Pluralibacter pyrinus | Pluralibacter pyrinus | + | + |

| h1420-023 | 6550 | Pluralibacter pyrinus | Pluralibacter pyrinus | + | + |

| h1420-024 | 3170 | Pluralibacter pyrinus | Pluralibacter pyrinus | + | + |

| h1420-027 | 4910 | Pluralibacter pyrinus | Pluralibacter pyrinus | + | + |

| h1420-028 | 5820 | Pluralibacter pyrinus | Pluralibacter pyrinus | + | + |

| hy192-2 | 5120 | Pluralibacter pyrinus | Pluralibacter pyrinus | + | + |

| h1435-013 | 4730 | Raoultella ornithinolytica | Raoultella ornithinolytica | + | + |

| h1420-009 | 5030 | Raoultella ornithinolytica | Raoultella ornithinolytica | + | + |

| h1420-011 | 4820 | Raoultella ornithinolytica | Raoultella ornithinolytica | ||

| h1420-010 | 4700 | Raoultella ornithinolytica | Raoultella ornithinolytica | + | + |

| h1420-012 | 4270 | Raoultella ornithinolytica | Raoultella ornithinolytica | ||

| h1420-013 | 4360 | Raoultella ornithinolytica | Raoultella ornithinolytica | + | + |

| h1435-026 | 2880 | Raoultella planticola/ornithinolytica | Raoultella planticola | + | + |

| hy93-1 | 1870 | Raoultella planticola/ornithinolytica | Raoultella planticola | + | + |

*Pantoea anthophila was not available in the standard biotyper reference library, and the score of Pantoea agglomerans indicated identification at the genus level

In a previous study, a mass spectral analysis by MALDI-TOF MS showed that HPB had common peaks among species or genera (Fernández-No et al. 2010). However, no peaks were common to all HPBs, and thus the relationship between these peaks and histamine was unknown. Therefore, it was not possible to determine whether the bacteria produced histamine.

Quantification of histamine in HPB strains

Histamine levels in HPB strains were quantified and found to range from 5 to 6550 µg/mL (Table 1). According to previous studies, HPB strains produce between 0.1 and 350.7 mg/100 mL histamine for mesophilic bacteria (López-Sabater et al. 1996), and 167–8977 µg/mL histamine for psychrophilic bacteria (Trevisani et al. 2017). Thus, our findings are consistent with these studies. Based on this result, fish in the market are contaminated with bacteria that can produce high levels of histamine and may cause histamine food poisoning.

Histamine detection by MALDI-TOF MS

Bacterial strains

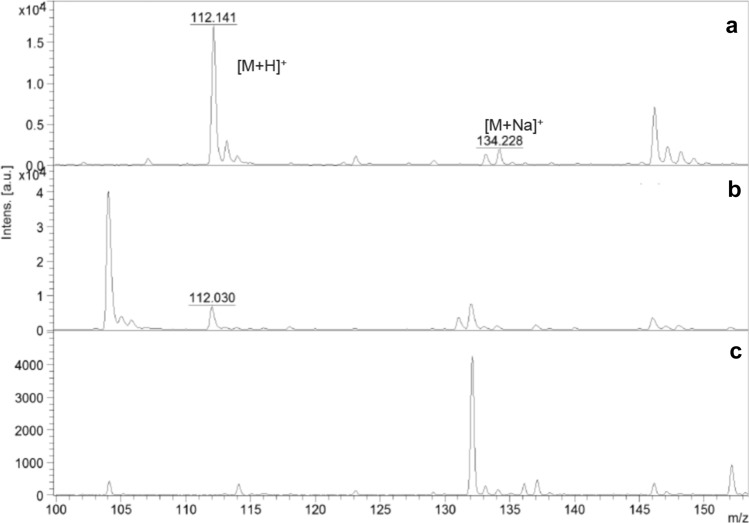

In Niven's medium, histamine was detected in all HPB strains after 24 h of incubation. Histamine was detected in all histidine broths, except in two strains with low histamine production (hy206-1 and hy210). In contrast, in Niven's medium and histidine broth extracted with acetonitrile as a negative control and non-HPB, no mass spectral peak was found at 112 Da (Fig. 1). Although Niven's medium is known to give false-positive results (Fernández-No et al. 2011), MALDI-TOF MS is not associated with false-positives or false-negatives.

Fig. 1.

Mass spectra of histamine standard solution and bacterial strains. a Histamine standard solution, b 1420-009 (Niven’s medium), c 1420-010 (histidine broth), d Niven’s medium, e Histidine broth. Characteristic peaks of protonated ions as [M + H]+ and [M + Na]+ were detected at 112 Da and 134 Da, respectively

In this study, the detection rate of histamine in Niven's medium was higher than that in histidine broth, possibly because of the composition of the medium and testing method. Our method efficiently detected histamine at a peak of 112 Da regardless of the bacterial species and greatly shortened the mass spectral analysis time by using a simpler procedure. The detection of microbial toxins using MALDI-TOF MS has been attempted for various toxins such as mycotoxins (Hleba et al. 2017), botulinum neurotoxin (Kalb et al. 2015), and cereulide (Ulrich et al. 2019). This method is expected to be increasingly used to detect toxins that cause food poisoning.

LOD in strains

The LOD using MALDI-TOF MS was 200 µg/mL, indicating that our method is less sensitive than conventional HPLC, which detects 1.8 µg/mL (Kounnoun et al. 2020). However, histamine was detected in all HPB strains cultured on Niven’s medium after 24 h of incubation. Additionally, previous studies showed that histamine production by Pseudomonadaceae and Enterobacteriaceae HPB is above 200 µg/mL. (Fernández-No et al. 2011; Hu et al. 2015). Therefore, HPB, which produces a large amount of histamine that causes histamine food poisoning, may be detectable. Even if the strains produce histamine at a concentration less than 200 µg/mL, histamine is likely detectable by extending the incubation time or changing the medium.

Food samples

Histamine was detected in sardine-1, sardine-2, and sardine-3 at a signal-to-noise ratio of 20, 43, and 26, respectively. Histamine was not detected in the solution of histamine-free dolphinfish (Fig. 2). Histamine food poisoning is generally associated with the consumption of foods containing high histamine levels (≥ 500 ppm) (FDA 2020). In recent years, histamine food poisoning occurred in France, with histamine detected at 1720 ppm in leftover tuna (Velut et al. 2019). Our method detected histamine in the range of 1600–1900 ppm in sardine fish balls; considering the histamine levels in illness-causing fish, it may be necessary to further enrich the sample.

Fig. 2.

Mass spectra of histamine standard solution and food sample. a Histamine standard solution, b sardine-2 causing histamine food poisoning, c Histamine-free dolphinfish. Histamine was detected in sardine-2 at a signal-to-noise ratio 43 but not detected in histamine-free dolphinfish

Conclusion

Our method enables detection of histamine and identification of bacterial species simultaneously in the same target plate after 24 h of incubation, by calibrating two different ranges. As this method detects histamine, the bacterial strains must be cultured in medium containing histidine. Additionally, as histamine was detectable in fish that caused histamine food poisoning, our method may be useful for early investigation of causative bacteria and food in cases of histamine food poisoning. However, this study has some limitations. First, our method does not quantify the levels of histamine, although this quantification is not essential for detecting HPB. Second, our method shows low sensitivity compared to conventional HPLC. However, bacteria that cause histamine food poisoning produce large amounts of histamine; therefore, this is likely not a major concern. Additionally, sample concentration is required to detect histamine in fish samples. Future studies are required to optimize the enrichment process for increasing the sensitivity of histamine detection.

Author contributions

SU: Conceptualization, methodology, investigation, writing– original draft, writing—review and editing, MK: Investigation, resources, KK: Investigation, resources, JS: Writing—review and editing, supervision, KS: Supervision.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

None.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Akiyama H, Ishii R, Okamoto T, Goto H, Saeki K, Sakai S, Sakuma T, Teshima R, Mino Y (2020) 2.1 Syokuhinseibunsikenhou. In: The Pharmaceutical Society of Japan ed. Methods of analysis in health science 2020, Kanehara Shuppan, Tokyo, pp 197–283

- FDA (2020) Scombrotoxin (Histamine) formation. In: Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Food and Drug Administration, Center for Food Safety and Applied Nutrition, Office of Food Safety, Washington, D.C. Fish and fishery products hazards and controls guidance, 4th edn, pp 113–151

- Fernández-No IC, Böhme K, Gallardo JM, Barros-Velázquez J, Cañas B, Calo-Mata P. Differential characterization of biogenic amine-producing bacteria involved in food poisoning using MALDI-TOF mass fingerprinting. Electrophoresis. 2010;31:1116–1127. doi: 10.1002/elps.200900591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-No IC, Böhme K, Calo-Mata P, Barros-Velázquez J. Characterisation of histamine-producing bacteria from farmed blackspot seabream (Pagellus bogaraveo) and turbot (Psetta maxima) Int J Food Microbiol. 2011;151:182–189. doi: 10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.08.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hleba L, Císarová M, Shariati MA, Tančinová D. Detection of mycotoxins using MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry. J Microbiol Biotechnol Food Sci. 2017;7:181–185. doi: 10.15414/jmbfs.2017.7.2.181-185. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu JW, Cao MJ, Guo SC, Zhang LJ, Su WJ, Liu GM. Identification and inhibition of histamine-forming bacteria in blue scad (Decapterus maruadsi) and chub mackerel (Scomber japonicus) J Food Prot. 2015;78:383–389. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X.JFP-14-296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiranuntipon S, Delia M, Albasib C, Damronglerdc S, Chareonpornwattanad S, Thaniyavarn J. Decolourization of molasses based distillery wastewater using a bacterial consortium. Sci Asia. 2009;35:332–339. doi: 10.2306/scienceasia1513-1874.2009.35.332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalb SR, Baudys J, Wang D, Barr JR. Recommended mass spectrometry-based strategies to identify botulinum neurotoxin-containing samples. Toxins. 2015;7:1765–1778. doi: 10.3390/toxins7051765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kounnoun A, Maadoudi ELM, Cacciola F, Mondello L, Bougtaib H, Alahlah N, Amajoud N, El Baaboua A, Louajri A. Development and validation of a high-performance liquid chromatography method for the determination of histamine in fish samples using fluorescence detection with pre-column derivatization. Chromatographia. 2020;83:893–901. doi: 10.1007/s10337-020-03909-9. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- López-Sabater EI, Rodríguez-Jerez JJ, Hernádez-Herrero M, Roig-Sagués AX, Mora-Ventura MT. Sensory quality and histamine formation during controlled decomposition of tuna (Thunnus thynnus) J Food Prot. 1996;59:167–174. doi: 10.4315/0362-028X-59.2.167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagayama T, Tamura Y, Maki T, Kan K, Naoi K, Nishima T. Non-volatile amines formation and decomposition in abusively stored fishes and shellfishes. J Hyg Chem. 1985;31:362–370. [Google Scholar]

- Niven CF, Jeffrey MB, Corlett DA. Differential plating medium for quantitative detection of histamine-producing bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1981;41:321–322. doi: 10.1128/AEM.41.1.321-322.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi H, Kimura B, Yoshikawa M, Fujii T. Cloning and sequencing of the histidine decarboxylase genes of gram-negative, histamine-producing bacteria and their application in detection and identification of these organisms in fish. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2003;69:2568–2579. doi: 10.1128/aem.69.5.2568-2579.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamura K, Stecher G, Peterson D, Filipski A, Kumar S. MEGA6: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30(12):2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trevisani M, Mancusi R, Cecchini M, Costanza C, Prearo M. Detection and characterization of histamine producing strains of Photobacterium damselae subsp. Damselae isolated from mullets. Vet Sci. 2017;4(2):31. doi: 10.3390/vetsci4020031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrich S, Gottschalk C, Dietrich R, Märtlbauer E, Gareis M. Identification of cereulide producing Bacilluscereus by MALDI-TOF MS. Food Microbiol. 2019;82:75–81. doi: 10.1016/j.fm.2019.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Velut G, Delon F, Mérigaud JP, Tong C, Duflos G, Boissan F, Watier-Grillot S, Boni M, Derkenne C, Dia A, Texier G, Vest P, Meynard JB, Fournier PE, Chesnay A, Pommier de Santi V. Histamine food poisoning: a sudden, large outbreak linked to fresh yellowfin tuna from Reunion Island, France, April 2017. Euro Surveill. 2019;24:1800405. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2019.24.22.1800405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walckenaer E, Poirel L, Leflon-Guibout V, Nordmann P, Nicolas-Chanoine MH. Genetic and biochemical characterization of the chromosomal class a beta-lactamases of Raoultella (formerly Klebsiella) planticola and Raoultella ornithinolytica. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2004;48:305–312. doi: 10.1128/aac.48.1.305-312.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]