Abstract

Extensive research on traumatic life experiences reveals how healthy development can be derailed and brain architecture altered by excessive or prolonged activation of the body’s stress response, impacting health, mental health, learning, behavior and relationships. Schools offer a unique environment to prevent and counter the impacts of childhood trauma. This study aimed to investigate empirical evidence for school-wide trauma-informed approaches that met at least two of the three essential elements of trauma-informed systems defined by SAMSHA (2014). SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 14-4884. Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SMA14-4884.pdf) and consider commonalities in approaches, drivers of change, challenges and learnings related to implementation, sustainability and outcomes for students. A systematic review searching foremost databases was conducted for evidence of trauma-informed school-wide approaches used between 2008 and 2019. Four papers were identified, incorporating four school-wide approaches, The Healthy Environments and Response to Trauma in Schools (HEARTS) Model; The Heart of Teaching and Learning (HTL): Compassion, Resiliency, and Academic Success Model; The New Haven Trauma Coalition (NHTC) and The Trust-Based Relational Intervention. Although heterogeneous, the models shared core elements of trauma-informed staff training, organization-level changes and practice change, with most models utilizing student trauma-screening. Generalizability of the findings was low given the small number of studies, the mix of mainstream and specialist schools and high risk of bias. Given the limitations of research in this emergent but rapidly accelerating field, future research is urgently required to understand the interaction between core elements of a trauma-informed approach, teaching pedagogy and organizational factors that support the embedding, use and transferability of school-wide approaches.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (10.1007/s40653-020-00321-1) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Trauma-informed, School-wide, Complex trauma, Childhood trauma, School mental health

Extensive research on traumatic life experiences and the neurobiology of stress reveals how healthy development can be derailed and brain architecture altered, especially during critical developmental periods, by excessive or prolonged activation of the body’s stress response and immune systems, impacting health, mental health, learning, behaviour and relationships (Finkelhor et al. 2015; Fonagy et al. 2013; McLaughlin et al. 2013; Perfect et al. 2016; Proche et al. 2016; Teicher and Khan 2019; Van der Kolk 2007). The landmark Centre for Disease Control, Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACES) study highlighted both the commonality and pervasiveness of childhood adversity (Felliti et al. 1998) revealing that trauma has no boundaries of age, gender, ethnicity, or geography, nor economic or social status and has become a global health epidemic (Felliti et al. 1998). As emphasised by the National Child Traumatic Stress Network ([NCTSN] 2017) even when a traumatic event does not result in clinical symptoms such as posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), anxiety, or depression (Teicher and Khan 2019), it can have a serious impact across all major domains of functioning including cognition and learning, impacting ability to pay attention, retain information and interact positively (DuPaul et al. 2014; Fabiano et al. 2013).

The intent of trauma-informed school approaches is to ameliorate the impact of trauma and support healing, growth and change by leveraging all aspects of the school system inclusive of policies and procedures that collectively create safe and supportive learning environments (Bateman et al. 2013) to support the wellbeing and development of all students, enabling students to regulate their emotions, focus their attention, and succeed academically and socially (Cole et al. 2013; Giboney Wall 2020; Rowe et al. 2007). The inclusion of school-wide practice and infrastructure change is considered essential to create a culture shift that promotes “trauma sensitive thinking and acting” (Cole et al. 2013, p. 8). As described by the NCTSN (2016), in a trauma-informed service “all parties involved recognize and respond to the impact of traumatic stress on all who have contact with the system, including children, caregivers, staff, and service providers” (p. 2). Although a universally agreed upon definition of ‘trauma-informed’ is currently lacking (Thomas et al. 2019), implicit in being trauma-informed is holding four main premises: (1) that exposure to trauma is widespread and has pervasive impacts; (2) believing that healing from trauma is possible; (3) that relationships play a key role in the process of change; and (4) that safety is critical for healing and preventing further impact (Bloom 2016; National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) 2016; Chafouleas et al. 2016).

The Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA 2014) defines trauma-informed care, using ‘the 4 R’s’, as programs, organizations, or systems “that realize the widespread impact of trauma and understands potential paths for recovery; recognize the signs and symptoms of trauma in clients, families, staff, and others involved with the system; and respond by fully integrating knowledge about trauma into policies, procedures, and practices, and seeks to actively resist re-traumatization” (SAMSHA 2014, p. 9), whilst examining assumptions and biases and the intersection of inequality and trauma.

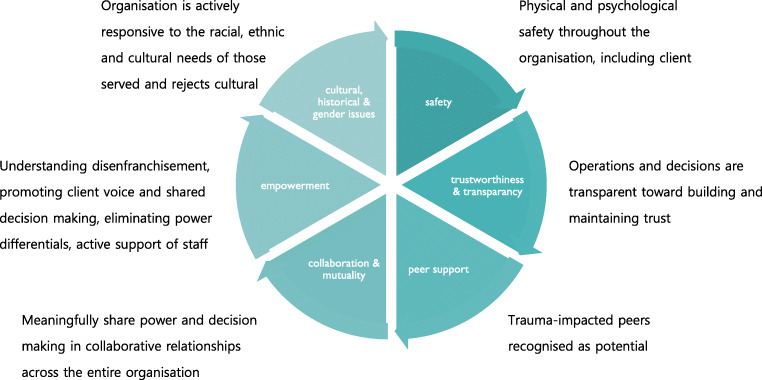

SAMHSA (2014) also provides a guide to implementation centred on six key principles of a trauma informed approach as seen in Fig. 1, which assume a continuum of care approach ranging from prevention through to intensive targeted interventions.

Fig. 1.

Adapted from SAMHSA’s six key principals of trauma-informed care

Consistent with the SAMSHA principals and guidelines, an American Institute of Research report (Jones et al. 2018) on a 2-year demonstration study implementing the Trauma Learning Policy Initiative’s (TLPI) Flexible Framework approach, highlights that there are multiple interrelated elements to trauma-informed schools.

There is substantial momentum for trauma-informed school-wide approaches to avert the “cascading risks of school failure” (Cole et al. 2013, p. ix), experienced by youth with histories of childhood adversity (Becker-Blease 2017; Blodgett and Dorado 2016; Overstreet and Chafouleas 2016). Considerable diversity exists, however, in how trauma-informed interventions are delivered in schools and little is known about what constitutes the essential elements of a trauma-informed school, whether these change for different demographics and how the elements work together to effect outcomes.

The primary aim of this systematic review was to investigate current evidence for trauma-informed school-wide models that incorporate at least two of the three domains of trauma-informed organisation wide practice as defined by SAMSHA (2014) and to consider commonalities and differences in approaches, use of staff training, drivers of change, and the challenges and learnings related to implementation and sustainability and outcomes for students. A systematic review examining evidence rigour for trauma-informed schools (Maynard et al. 2018), found a significant lack of scientific strength in the field. Domains of inherent complexity, such as trauma, may be more receptive to qualitative or mixed methods evaluations (Dixon et al. 2014) than more formal approaches such as randomised control trials. A need for greater consistency in research methods is reported by Berger (2019) in a systematic review of trauma-responsive multi-tiered frameworks in schools. The current review has extended upon the work of Maynard et al. (2018) and Berger (2019) and included qualitative and mixed methods study designs and school-wide approaches that may or may not be within a multi-tiered framework.

Our secondary aim was to assess the quality of reviewed papers and risk of bias at the study level. Many of the standard indicators of bias risk that are used in reviews of clinical interventions, such as the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE), are not relevant to research on complex, multi-component interventions like trauma-informed care. Accordingly, our procedure for assessing risk of bias/study quality was informed by guidelines for systematic reviews (PRISMA-P, Cochrane, GRADE) as well as emerging guidelines for systematic reviews of complex interventions (Pinnock et al. 2015; Thomas et al. 2004).

Method

Information Sources

On 01 October 2019, 10 interdisciplinary data-bases were searched: A+ Education, Campbell Collaboration, ERIC, OVID Medline, ProQuest Central, ProQuest Dissertations and Thesis, ProQuest Published Literature on Traumatic Stress, ProQuest Social Science, PsychINFO and all EBM Reviews, incorporating, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, ACP Journal Club, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials, for papers in the time period between January 2008 and October 2019 given the relative newness of trauma-informed school developments.

Search Strategy

The search was organised around subheadings that were generated from the research aims of the first author (JA) and reviewed and endorsed by (MM and HM) and the senior author (HS). The systematic review protocol including PICO was submitted to PROSPERO [CRD42019119825] on 22 January 2019, prior to piloting the search. Search terms are shown in Supplementary Table 1. Covidence was used to manage the search results, with two independent reviewers screening the titles, abstracts and keywords of every article retrieved by the search strategy according to the selection criteria. Full text of the articles was retrieved for further assessment if the information given suggested that the study met the selection criteria or if there was any doubt regarding eligibility of the article based on the information given in the title and abstract.

As shown in Fig. 2, after removing 1835 duplicates, 11 papers accessed through searching additional sources including Google Scholar, bibliographies of included papers and from personal communication with authors, were added. This resulted in 7395 papers evaluated at the title and abstract level for potential inclusion against the criteria by two researchers, with discussion until mutual agreement. The total of 121 full-text papers were screened against inclusion criteria. Twenty-five percent of the total full-text papers were independently screened by both the first and second reviewers.

Fig. 2.

PRISMA diagram of the systematic search

Eligibility Criteria and Study Selection

The search was limited to studies conducted in schools (public, charter, alternative education, specialist campuses). The populations of interest were staff, and students ranging in age between 6 and 18 years, in the education system. Studies needed to be peer-reviewed, published in English, and provide empirical evidence. The intervention of interest was trauma-informed or trauma sensitive, school-wide practices. To meet inclusion criteria, interventions needed to comprise at least two of the following elements endorsed by SAMSHA (2014) and TLPI (Cole et al. 2013) as constituting trauma-informed practice:

Staff professional development directly related to understanding the impact of trauma

Practice change – implement changes in practice behaviours across the school i.e.: trauma screening, prevention and/or intervention and an intentionality towards relational connection with students

Organisational change – includes policies and procedures, strategies or practices to create a trauma-informed environment i.e.: policy relating to disciplinary practices

Studies were excluded where the practices being evaluated were solely trauma screening, assessment or treatment of trauma symptoms such as PTSD.

Risk of Bias Assessment

We assessed the quality of reviewed papers and risk of bias at the study level. Many of the standard indicators of bias risk that are used in reviews of clinical interventions, such as the Grading of Recommendations, Assessment, Development and Evaluations (GRADE), are not relevant to research on complex, multi-component interventions like trauma-informed care. Accordingly, our procedure for assessing risk of bias/study quality was informed by guidelines for systematic reviews (PRISMA-P, Cochrane, GRADE) as well as emerging guidelines for systematic reviews of complex interventions (Pinnock et al. 2015; Thomas et al. 2004).

Using the criteria outlined by Thomas et al. (2004), papers meeting the inclusion criteria were assessed for quality of the methodology related to selection bias, design, confounders, blinding, withdrawals and drop outs, resulting in a rating of either strong, moderate or weak and finally rated on the combined results. Papers with four or more strong ratings and no weak ratings were considered strong; papers with fewer than four strong ratings and one or less weak ratings were considered moderate; papers were considered weak if given two or more weak ratings. Papers rating as either moderate or strong were further assessed on the integrity of the intervention (percentage of study participants receiving the intervention as deigned) and use of an appropriate statistical methodology, including an analysis of intention to treat.

Data Extraction

To follow the recommendation of Thomas et al. (2004), only papers rated as either high or moderate in the risk of bias assessment would be analysed. In the current study, however, no studies met the risk of bias criteria. Therefore, to enable an evaluation and comparison of the models presented in the papers meeting the inclusion criteria, all four papers have been included in the current review. Data was extracted using the standardised format of Thomas et al. (2004). A narrative synthesis approach has been utilised, rather than meta-analysis, given the outcome measures used in the papers were not comparable.

Results

From the initial evaluation of 7395 abstracts and titles after duplicates were removed, 7274 papers were excluded. The excluded papers focused predominantly on medical or dental traumas, health staff trauma-practices, war-related trauma, or childhood PTSD treatments. The 121 papers that potentially met inclusion criteria were further assessed as full-text papers, resulting in the retention of four articles as shown in Fig. 2. Primarily papers that were excluded at this level were discussion papers, opinion papers, studies that lacked either interventions or outcomes or studies on war-related childhood trauma.

Each of the four papers evaluated a separate school-wide model: (a) The Healthy Environments and Response to Trauma in Schools (HEARTS) Model (Dorado et al. 2016; (b) The Heart of Teaching and Learning (HTL): Compassion, Resiliency, and Academic Success Model (Day et al. 2015); (c) The New Haven Trauma Coalition (NHTC) (Perry and Daniels 2016); and (d) The Trust-Based Relational Intervention (TBRI) Model (Parris et al. 2015). All four studies were from the United States, within disadvantaged, predominantly African American high-need populations in low socio-economic areas. Two studies, Day et al. (2015) and Parris et al. (2015) were conducted in specialist charter schools in resident facilities. All studies incorporated the three SAMSHA (2014) practice domains central to this review: staff professional development, practice change and organizational change. Data extraction and synthesis including student demographics, the aims, methodology, outcomes and study limitations of each paper are found in Table 1.

Table 1.

Data extraction and synthesis

| Citation | Aim & intervention | Participants & dropouts | Methodology | Outcomes | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Day et al. (2015) Michigan USA |

Aim: To implement and evaluate the effects of the modified Heart of Teaching and Learning (HTL): Compassion, Resiliency, and Academic Success on 1. levels of trauma 2. self-esteem 3. student attitudes toward teachers, learning, and school climate (student views of teacher supportiveness). Intervention: modified HTL: Compassion, Resiliency, and Academic Success model |

N = 70 students participated in both pre and post-tests. 26% of participantsset header were involved from baseline to post-test. No drop-outs. All staff trained (number not supplied). Demographics 14 - 18 year-old (grade 5 - 6) court-involved females in a residential treatment facility charter school. 86% current residents, 14% ex-residents living in community. 94% High school level and 6% middle-school. The majority of participants were African American (66%), White (20%), Hispanic (3%), and other races or ethnicities (11%). |

Study design: a single group, pre–post-test design. Data Analysis: Mixed methods, using a suite of surveys and screens • Student Needs Survey (SNS) • The Child Report of Post-traumatic Symptoms (CROPS) • The Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (RSE) • Perceptions of school climate survey. series of paired sample t-tests to explore relationships between participants’ pre/post-test scores on the SNS, CROPS, & RSE measures. Two-tailed tests were used in the analysis, the alpha level .05. Effect sizes calculated using Cohen’s d. Covariates: Not stated. Length of follow-up: 72% of participants exposed to intervention for 6 months or more. No further follow-up stated. |

The intervention was found to ameliorate PTSD symptoms. 1. Student Needs: one sub-scale showed a significant negative post-test decrease in the survival rating, effect size medium. Rationales for this are offered. 2. CROPS - PTSD significant pre-post-test difference for PTSD score indicting medium positive effect. 3. Self-esteem: scores were in the normal to high range with an average of 27 in the pre- and post-test groups, indicating that self-esteem was not a significant issue for this group initially and was not significantly altered post intervention. 4. School Climate: no significant difference, students felt almost all teachers were responsive to their needs prior to the intervention. |

• small sample size completing full intervention • variable length of participation • actual participation rate, including withdrawal or dropout data not provided • unclear whether school attendance & study participation mandated re: residential school • absence of control to account for student perceptions of teachers & student self-esteem found at baseline, with no significant changes in either factor post intervention • data gathering methodology provided is limited • potential influence of school counsellor gathered student data |

| Dorado et al. (2016) San Francisco USA |

Aim: Evaluate the effectiveness of the Healthy Environments & Response to Trauma in Schools (HEARTS) programme to: 1. increase school staff knowledge about addressing trauma and in use of trauma-sensitive practices; 2. improve student school engagement; 3. decrease behavioural problems associated with loss of instructional time due to disciplinary measures; 4. decrease trauma-related symptoms in students who received HEARTS therapy. Intervention: The HEARTS model |

Students N = 1,243 across 4 schools. Student Survey response rate 62%. A sub-sample of 88 students participated in HEARTS psychotherapy. Staff survey N = 175 teaching and non-teaching participants, from 280 surveys distributed. Demographics K - Grade 8 (76% students qualified for free or reduced lunch). Girls 47% Boys 53%. 38% African-American, 34% Hispanic or Latino of any race, 4% Asian, 8% Pacific Islander, 4% Filipino, 2% White, 4% two or more Races, 1% American Indian or Alaska Native, 4% race/ethnicity not given. |

Study design: multi-group & retrospective pre-post-test and multiple post-tests. Data analysis: Mixed methods. T-test comparisons of pre - post scores. • staff-report on student engagement, administrative data on attendance, disciplinary office referrals and suspensions. • retrospective pre-post staff survey; survey data gathered at the end of each full year of implementation using the HEARTS Program Evaluation Staff Survey. • Pre and post scores T-test comparison of Child & Adolescent Needs and Strengths (CANS) scales used to measure HEARTS therapy outcomes. Covariates: not stated Length of follow-up: Differed for individual schools: School A, 5 years; School B for 4 years (1-year gap between the 3rd and 4th years); School C, 2 years, School D, 1.5 years. |

Staff knowledge: increases across five knowledge and practice items: • knowledge about trauma and its effects = 57% increase • understanding how to help traumatised children learn = 61% increase • knowledge of trauma-sensitive practices = 68% increase • knowledge of burnout & vicarious traumatisation = 65% increase • use of trauma informed practices = 49% increase School engagement: significant changes across each student engagement item, with increases in: • students’ ability to learn = 28% • students’ time on task in class = 27% • students’ time in class = 36% • students’ school attendance = 34% End of year 1 decreases in: total incidents – 32%; physical aggression - 43%; no significant reduction in suspension rate. After year 5 decreases in: total incidents – 87%;, physical aggression – 86%; suspension rate – 95%. Trauma symptoms: significant improvements reported on CANS items: adjustment, affect regulation, intrusions, attachment, dissociation. |

• lack of drop-out data for total student group • no indication as to the validity of the HEARTS Program Evaluation Survey. • variable length of intervention for each of the four schools in the study, impacting cross-school outcome comparison. • the duration of psychotherapy not reported. • not controlling for the influence of a single intervention component over others, esp. relating to impact of staff training on student outcomes - a core element of the study. • self-report retrospective pre-post design for staff knowledge & practice, & staff-views of student engagement. • CANS is a clinician rated report of client outcomes, thereby susceptible to bias. |

| Parris et al. (2015) Texas USA |

Aim: Evaluate the Trust-Based Relational Intervention (TBRI) in a secondary charter school in relation to behavioural outcomes. Intervention: The Trust-Based Relational Intervention (TBRI) Model |

N = 23 teachers N = 138 students in grades 7 - 12 Demographics Residential care campus, referred by Child Protection/ Youth Justice/ Guardians. Student ethnicity - 49 % white, 35 % African-American, 12 % Hispanic, 4 % others. 100% of students attending this school rated as economically disadvantaged and at risk of dropping out of school |

Study design: Qualitative, including Interviews of school staff and administration; Focus groups at multiple time-points; Interviews at end of year -2; Administrative data on incidents. Data analysis: Analysis of school Incident Reports, interview & focus group data Covariates: none Length of follow-up: Two time-points, end of year 1 and end of year 2 |

Key Findings: Incidents of aggressive and disruptive behavior decreased markedly. Office referrals Post year 1 decrease for: • physical aggression or fighting with peers – 33%. Post year 2 decrease for: • physical aggression – 68% • verbal aggression – 88% • disruptive behavior – 95%. Total decrease in incidents after 2 years of implementation – 93.5%. • Noted student increased use of counsellors, reduced profanity, reduced complaints. • Staff reported improved school culture; overall increased positive mood and countenance among staff and students. |

• unclear if the students in CBITS intervention group also part of the student workshop series. • relies on teacher self-report of increased understanding of trauma, with no observations made of change in teacher practice, or changes to teacher self-care. • the student and staff surveys used are not reported as validated. • No retention or drop-out data provided |

| Perry and Daniels (2016) USA |

Aim: Implementation Review of 4 logic model deliverables: 1. School staff/community learn about trauma sensitive practices 2. Students requiring trauma informed supports identified 3. Implementation of support systems to provide TIS to students 4. Students develop skills to cope with current symptoms & how to respond to future stress. Intervention: The New Haven Trauma Coalition (NHTC) Pilot intervention by the Clifford Beers Clinic (CBC) |

Staff training N = 32. Students N = 77, 3-day workshop series in two 5th grade and two 6th grade classrooms (N = 77). Cognitive Behavioural Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS) program participants (n = 17) grade 6 students. Attrition n = 3. Unclear if the students in the CBITS intervention group were also part of the student workshop series. Demographics Grades 5-6 student ethnicity: 82% Black/AfricanAmerican, 13 % Hispanic/Latino, and 5% White. School serves predominantly low-income population; 76 % of students eligible for Free Lunch, 5% eligible for Reduced Lunch |

Study design: mixed methods, exploratory pilot study using a suite of interventions: - direct services - staff training - care co-ordination 3 - 6 months - clinical services to students & families. Data analysis: non-validated surveys, UCLA - 4PTSD assessment - validated and standardised Covariates: None stated. Length of follow-up: No follow-up |

Staff Training Satisfaction – 97% • 47% learnt new stress reduction technique • 38 % learnt to implement better self-care • 16% better able to recognise trauma Classroom workshops: Student Satisfaction Survey – increased understanding in: • how to relax – 95% • trusting others – 92% • how to worry less – 91% Pre-post workshop changes - students report increase in understanding: how to relax (43.5/73.9%); trusting others (33.3/40.6%); worrying less (40/63.8%). CBITSpre-test 100% (N = 17) of students met criteria for PTSD with symptoms reported as: • distress from hearing about a violent death or serious injury of a loved one (65%); seeing someone beaten, shot, or killed (41%) • 52% ‘Other’ ie: hearing about or seeing someone killed, being a victim of violence. Post-test 17% met PTSD overall symptom criteria; 70% met re-experiencing criteria; 41% met avoidance criteria; 71% met increased arousal criteria. |

• interventions occurring jointly at the school & residential facility without controls to account for the potential impact on causal relationships, for example, the use of Nurture groups at the residence, but not the school may have augmented school outcomes. • changes to the office-referral policy during the implementation period of the study. • relies on teacher self-reports of training impact – no observations made of change in teacher practice, or changes to self-care • student and staff surveys used are not reported as validated. • use of a retrospective pre-post student satisfaction survey. • unclear if student outcome data was shared with staff at the various collection points and if or how this may have influenced outcomes. |

All four models reported varied but predominantly positive outcomes across a range of intervention interests, including behavioural change, trauma symptoms, self-esteem and increased staff knowledge of trauma. Variation existed in the use of validated and descriptive measurement tools. School administrative data on office referrals for behavioural incidents was a primary measure of outcomes, with most studies (Day et al. 2015; Dorado et al. 2016; Perry and Daniels 2016) also assessing symptoms of trauma, one study assessed school engagement (Dorado et al. 2016) and one study assessed student’ views of teacher’ supportiveness (Day et al. 2015). Details of the significant features of each model, mapped to the SAMSHA domains are outlined in Table 2.

Table 2.

Components of models mapped to SAMSHA domains

| Model | Description | Training Component | Organisation Level Change | Practice Level Changes | Strengths/ Drivers of Change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HTL (Day et al. 2015) |

The Heart of Teaching and Learning: Compassion, Resiliency and Academic Success (HTL; Wolpow et al. 2009) is grounded in ecological and attachment theories. The model is applied as a manualized curriculum using psychoeducational, cognitive-behavioural and relational approaches emphasising attachment focused interventions and a trauma-informed organisational culture cognizant of the impact of trauma on the individual at the micro-system level through levels of proximity up to broad societal impacts at the higher mesosystem level. The model includes ‘Theraplay’ (Jernberg and Booth 1999) an approach to working with children and adolescents building attachment, self-esteem, trust in others, and positive engagement, and an emphasis on positive staff and student relationships. |

Two half-day staff trainings and 2-hour booster trainings occurring monthly over 8 months. Training included six modules covering trauma, survival responses and compassion, self-care, strategies, collaborative problem solving, trusting others, diversity related issues, use of role plays, games, and case vignettes. Initial training sessions, followed by small group, role play and practice sessions. Additional tools and resources for classroom use where provided, including examples and idea lists. Inclusion of Theraplay training and issues of diversity such as gender and racial identity. |

Alternative school discipline policies and practices to support student regulation and problem-solving. Implemented preventative behaviour intervention polices. Development of specific spaces and supports for proactive student de-escalation – the Monarch Room (MR) – used for 10-15 minutes of calming and the Dream Catcher Room (DC) for longer withdrawal periods. |

1. use of psychoeducational, cognitive-behavioural, and relational approaches to improve student self-management 2. increased teacher attention to sensory needs of students, provision of fidget toys, sensory items, access to music 3. assess to snacks and hydration. 4. supporting student use of the MR and DC rooms for self-management. |

1.Teacher coaching and classroom observations to ensure fidelity of program delivery. 2. Significant focus on positive teacher-student relationships. 3. Focus on student voice. 4. Explicit attention to sensory needs and practices. 5. built student autonomy 6. As a residential charter school, had consistency across school and residence. |

| HEARTS (Dorado et al. 2016) | UCFS Healthy Environments and Response to Trauma in Schools (HEARTS) Model is a continuum of response model that includes universal approaches at Tier 1 and increasing levels of support and individualized intervention in Tiers 2 and 3. Core principles include promoting an understanding of trauma and stress, providing safety and predictability, fostering compassionate and trusting relationships, building resilience and social emotional learning, practicing cultural humility and responsiveness and facilitating empowerment and collaboration. The model draws significantly on the research and theory of the Attachment, Self-Regulation and Competency (ARC) framework (Blaustein and Kinnniburg, 2010). The models' 4 specific aims: (1) increase student wellness, engagement and success in school, (2) build staff and school system capacities to support trauma-impacted students through increasing knowledge and practice of trauma sensitive classroom and school-wide strategies, (3) promote staff wellbeing through addressing burnout and secondary trauma (4) integrate a cultural and equity lens. This model emphasizes a whole of system approach guided by a flexible framework based on TLPI (Cole, et al., 2013) |

Initial and follow-up training, with on-site consultation and capacity building for staff, embedding understanding of survival-based behaviors, student triggers and the student’s safety needs. Staff training presented the neuro-biology and physiology of trauma using educator’ language and everyday metaphors e.g the ‘learning brain’ and the ‘survival brain’, discussion on behaviorally based consequences serving to inadvertently escalate unwanted behaviors and how to focus on the safety needs of the student to reduce escalation. Supplemental training provided additional depth in trauma awareness including the impact of secondary stress for staff and need for self-care. |

Mapped the trauma-informed approach into MTSS used at the school, discipline policy changes from punitive to a focus on meeting safety needs and supporting student emotional regulation. Use of Logic model and clear statement of the model’s core guiding principles, rationale and practices. |

1. use of trauma-sensitive practices (unspecified). 2. trauma-informed behaviour management plans. 3. trauma-impacted students received culturally congruent trauma-specific psychotherapy aimed at building emotion regulation and relationship skills, and other positive coping skills. 4. intergenerational and community impacts of trauma recognised. 5. clinicians working with the caregivers of students in therapy groups to strengthen parenting capacity. |

1.pre-intervention analysis of the readiness and motivation of the school. 2. particular attention to school infrastructure, e.g. a reasonably well functioning Coordinated Care Team with key staff and administrators, and leadership by-in. 3. pre-intervention dove-tailing program principles with school district’s existing values, goals and initiatives. 4. onsite consultation supporting staff to put theory into practice, in-class, in-the-moment modelling of behaviour support strategies. 5. engaging with and supporting families 6. Staff self-care training |

| TBRI (Parris et al. 2015) |

The Trust-Based Relational Intervention (TBRI) model is grounded in authoritative discipline theory with 3 essential principles: empowering, connecting and correcting. The principal of empowering seeks to provide a safe, predictable and nurturing environment for students - includes provision of hydration, snacks and sensory tools. The connecting principles focus on relational practices and 4 specific areas of a) seeking care, b) giving care, c) negotiating, and d) feeling comfortable with an autonomous self. The correcting principles centre on preventing challenging behaviour, teaching appropriate behaviours, self-regulation and social skills. Nurture Groups are a core component, providing opportunities to build relationships, regulation and communication skills. |

2-day all staff training on complex trauma and effects on youth, how to recognise trauma-based behaviours, how to help students regulate and creating environments where students feel safe, creating a balance between structure and nurture in student approaches and training on discipline that is nurturing and involved while fair and consistent. At the beginning of year-2 of implementation, leadership and 1 behaviour specialist received 5-day training in TBRI model. |

Predetermined disciplinary procedures were adapted to allow an individualised response to students’ behaviours while continuing to enforce rules and expectations. Allowing students to have water-bottles at their desks, snacks and fidget toys. Allowing use of headphones for music at lunch time. Removal of punitive discipline procedures | 1. staff act to build positive relationships with student & connect with student needs prior to any office referrals. 2. use healthy touch, listening to student emotional needs and providing frequent affirmations. 3. enhancing student self-management and social skills: using words for emotions, being kind, accepting consequences. 4. Building help-seeking, help-giving and negotiation skills in students. 5. Pro -active prevention of disruptive behaviour e.g. teaching appropriate behaviour, using ‘re-do’s or behavioural rehearsals. 6. create calm positive atmosphere, predictability 7. Preventative meetings to consider underlying drivers of student behaviour. |

1. model develops a shared ‘TBRI’ language across staff and students e.g. ‘compromise and re-do’. 2.comprehensive action plan. 3. had consistency across residential and school approaches. |

| NHTC (Perry & Daniels 2016) | The New Haven Trauma Coalition Program (NHTC), is a collaboration between the New Haven Public Schools, The Mayor’s Office of the City of New Haven, United Way of Greater New Haven/ BOOST!, and the Clifford Beers Clinic. The care-coordination component of the program, based on the Milwaukee Wrap-Around model, focuses on enhancing interactions between school, student and family. All students participated in a three-day workshop series tailored to meet needs expressed by the students i.e.: how to relax and worry less. Cognitive Behavioural Intervention for Trauma in Schools (CBITS) was provided in small, gender-specific groups assessed as significantly trauma-impacted, over the course of 10 weeks. |

2-day all staff training. PD explicitly aimed at creating expertise within the school to respond to students in a trauma-informed manner and creating a culture shift. Balance of trauma 101 /102 knowledge building, including presentations on impact of ACES, Developing Trust in Interpersonal Relationships and Motivational Interviewing. Workshops supported strengths-based interventions and trauma-informed practice change using new knowledge, de-escalation and self-care. |

Assessment of the needs and existing structures in the school. Comprehensive action plan to respond to chronic stress responses in school. Logic model to focus short, medium and long-term outcome expectations. Included systems to collaborate with the NHT Coalition. Alignment of discipline policy with trauma-informed approach. |

1.changed teacher-thinking about drivers of behaviour 2. ongoing dialogue between teachers, student and family 3. collaboration between providers-school-home-student 4. use of teacher self-care strategies. 5. stress-reduction techniques used with students 6. use of trauma-informed behavioural strategies (non-specified) |

1. pre-intervention assessment of school readiness 2.pre-intervention co-design of trauma-training with school leaders and discussions around student needs. 3. school focus on collaboration with students, family, agency. 4. development of comprehensive action plans linked to desired outcomes 5. Assessed both staff and student outcomes. |

The models were primarily grounded in ecological, attachment, and trauma theories and whilst all had core components in common, they used a variety of approaches to practice change and delivery of supports to staff. Elements reported to enhance up-take of effectiveness of each are included under strengths in Table 2. All of the studies leveraged knowledge of trauma impacts to shift attitudes about student behavior, change discipline practices and prioritize relational-focused practice. Models focused on the safety needs of students to reduce behavioral escalation, including sensory and calming supports. Most studies provided additional supports to teachers to embed trauma-informed practices.

A matrix of elements found in the SAMSHA guidelines linking to key values, the 4′R’s and the six core principals of trauma-informed approaches is provided in Table 3, along with the strengths of the model that support drivers for change. The impact of individual intervention elements and the capacity to accomplish the related outcomes was evaluated by Perry and Daniels (2016). How the elements of interventions in combination contributed to overall outcomes has not been part of the current study methodologies.

Table 3.

Overview of the components of models

| Staff PD | Org. level change | Practice change | Student views | Family involved | Cultural consideration | Teacher challenges | Assess trauma | Clinical/therapy | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model | HTL | • | • | • | • | • | • | |||

| HEARTS | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | • | |

| TBRI | • | • | • | |||||||

| NHTC | • | • | • | • | • | • |

Risk of Bias

Addressing the secondary aim of this study, the quality of reviewed papers and risk of bias at the study level was assessed. All of the four studies were rated as weak on the risk of bias assessment (outlined in the methodology section above), due to a range of factors. A weak rating across confounders and blinding was common to all studies, one study was rated as having strong data collection methods (Parris et al. 2015) and three rated as moderate. Three studies were assessed strong on being representative of the population studied (Day et al. 2015; Dorado et al. 2016; Perry et al. 2016) with one study being rated as moderate (Parris et al. 2015). Blinding of participants or researchers was not reported by any of the studies. Withdrawals/dropouts of participants from studies was rated as weak for all but Perry et al. (2016) that had a moderate rating. Study design strength was rated as moderate for all studies. The limitations related to study design are found in Table 1.

Discussion

This review aimed to investigate current evidence for trauma-informed school-wide models, and to synthesize core elements and commonalities of approaches, drivers of change, and the challenges and learnings related to implementation and sustainability. The review found the strength of evidence for school-wide trauma-informed models was low. Although there is a great deal of enthusiasm for trauma-informed schools and a growing body of research, the current review highlights the dearth of robust studies into explicitly trauma-informed whole-of school approaches. Only four papers met the inclusion criteria of containing at least two of the three core domains of organisation-wide practice based on SAMHSA’s guidelines (2014) with all four studies rated as weak overall in the assessment of risk of bias.

The assessment of study design strength was constrained by limited data collection details reported in the studies, including whether participant blinding was utilized. One study (Day et al. 2015) was limited by the small sample size of participants involved for the entirety of the intervention, and two studies did not control for confounders such as pre-intervention levels of self-esteem or additional exposure to intervention, external to the intervention under study (Day et al. 2015; Parris et al. 2015). All four studies used administrative data of incidents pre-and post-intervention to assess outcomes, with the longer studies (Dorado et al. 2016; Parris et al. 2015) utilizing multiple time intervals of incident data collection. Use of administrative data has been noted as offering a potentially valid scientific methodology to evaluate system-wide initiatives (Figlio et al. 2015). While the use of multiple time-point data collection may provide opportunities to monitor outcomes and adapt interventions in responsive timely ways, it is not clear whether data feedback was provided to teachers, and if so, how this may have influenced teacher practices. The impact of data-collection methodology on student and teacher outcomes will be important to consider in future work.

Studies were not implemented as fixed protocols that would enable an experimental study of effectiveness, rather they were grounded in evidence-based Response to Intervention practices (Clark and Alvarez 2010; Jimerson et al. 2007) and trauma research and were tailored to the school context. Flexible frameworks are considered to have many advantages over fixed protocols, including improved uptake by staff and improved responsiveness to the unique culture of each school (Cole et al. 2013; Jones et al. 2018). Consideration of the feasibility and appropriateness of utilizing rigorous empirical approaches such as randomized control trials in studies with the complexities of trauma informed school-wide approaches is warranted.

Commonalities of the Models

A primary aim of this review was to synthesize the core elements of trauma-informed school wide approaches. An overview of the shared components of the studies is found in Table 3 consistent with evidence-based practices as recommended by SAMHSA and TLPI and will be discussed below.

Staff Professional Development and Practice Change

The literature distinguishes a trauma-informed school as having an awareness about trauma’s impact on learning which becomes a primary motivator for taking action (Jones et al. 2018; Perfect et al. 2016). Consistent with this view, professional development was reported in all studies as a change catalyst, central to becoming trauma-informed and improving motivation to adapt practices. Staff training within the current studies was found to assist staff to reframe challenging student behaviors and thereby decrease their own potential re-active responses and the possibility of punitive practices, which in turn may have avoided further escalations of the students. Staff training on the impact of secondary trauma was included in the current studies, which aligns with trauma literature (Bloom 2019; NCTSN 2017). There are, however, a number of un-answered questions regarding what comprises effective trauma-training, in relation to key components, duration, and impact of trauma-informed training (Purtle 2018). The strength of relationship between trauma-training and practice-change in schools may depend on many factors, as evidenced by McIntyre et al. (2019) who found that the impact of knowledge-growth related to trauma was related to how teachers regarded the acceptability of adopting a trauma-informed approach, with teacher’s perception of ‘school-fit’ rating as the most influential factor in translating trauma-informed training into practice.

Use of training that enables a ‘spirit of enquiry’ is supported as a means of achieving ‘buy-in’ from staff, while meeting the unique needs of each school (Cole et al. 2013; SAMHSA; Jones et al. 2018). The current studies found that enabling teacher’s to be active participants in their training along with encouraging staff to express the challenges and systemic barriers they experienced, showed benefits as part of the intervention design.

Associated with teacher ‘buy-in’, are the findings of Brunzel et al. (2019) exploring the development of trauma informed positive education practices, reporting an increase in teachers’ sense of empowerment as professionals, a guiding SAMSHA principal (Fig. 1), to meet the needs of trauma impacted students through active collaboration and co-design design of teaching pedagogies. The consideration of the challenge’s experienced by teachers connects primarily with SAMSHA’s empowerment and safety principals along with the need to respond to staff wellbeing.

Organisational Level Changes

All studies were concerned with achieving outcomes through an intentionality towards connection, compassion, safety, and support, underpinned by staff understanding the ‘intent’ and context of behaviours and asking, ‘what is happening’ for this student at this time?’. Such approaches align with the 4 R’s of a trauma-informed school and SAMSHA principals (Fig. 1). Adoption of trauma-informed policies and procedures especially in relation to disciplinary practices were seen as key organisational changes helping to reduce incidences and optimize learning time. Discipline changes focused on increasing empathy, maintaining relational connection and development of self-regulation skills, supporting ‘time-in’ rather than ‘time-out’ of class. Replacing punitive, reactive measures with restorative, strength-based and skill-building approaches is strongly supported by the literature on evidenced-based interventions for trauma (Cole et al. 2013; Ford and Courtois 2013; NCTSN 2016). Care co-ordination teams of some form were also used across studies to obtain family-driven and student-involved planning and practices and to improve insights and collaboration. Guardian support, community involvement and collaborative intervention planning is recognized in the literature as best practice in trauma-informed care (SAHMSA 2014; NCTSN 2017).

Although there is an emphasis in the literature on creating whole-of-school climate change that will impact all stakeholders, organizational climate change was only measured from the teachers’ perspective in one study (Parris et al. 2015) and from the student perspective, in another (Day et al. 2015). Additionally, there was no reported data on staff well-being, although this is regarded as an essential element in both the delivery and sustainability of trauma-sensitive practice (Bloom 2017; Cole et al. 2013). Cole et al. (2013) emphasize the critical importance of providing school environments where students and staff feel safe and supported, to counter the impacts of trauma.

Student Views, Cultural and Family Needs

Seeking student views (Table 3) was a primary focus of the Day et al. (2015) study and was included in the Dorado et al. (2016) study. Consideration of student views and family involvement is a key value in the SAMSHA implementation domains stating that students and their family should have ‘significant involvement, choice and meaningful voice’ in the services provided (SAMSHA 2014, p. 13). Giving voice to students can result in modifications to classrooms that enhance the learning environment, reducing triggers and supporting relationships (Cole et al. 2005, 2013; SAMSHA 2014). Furthermore, the insights that students, families and communities have into their own needs and strengths, including how they can best be supported, is core to trauma-informed planning, the effectiveness of interventions, and the likely participation in those interventions (Alderson 2001; SAMSHA 2014; NCTSN 2016).

The consideration of student, family and cultural needs link to the empowerment, safety, cultural and gender principals of care (Fig. 1) and the commitment to resist re-triggering. Gaining insights into how school changes impact students, from the view of students is important on many levels, including empowering disenfranchised children to have a voice in what effects them, gaining students’ valuable insights, and aligns research with the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (United Nations General assembly 1989). Trauma-impacted students have typically experienced voicelessness and vulnerability, which may reach back through generations (Atkinson 2019; Mohatt et al. 2014) and a lack of consultation with students serves to reinforce these experiences and increases the risk of re-traumatization. (SAMHSA 2014).

Trauma Screening, Assessment and Therapy

Assessment of trauma and provision of therapy is considered essential in the SAMSHA guidelines, although this is prefaced with the need for consideration to be given to the availability of follow-up procedures and availability and access to trauma-specific services that match the client’s needs before screening and assessment occurs (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 57. Center for Substance Abuse Treatment (US). Studies utilising trauma assessment and intervention (Table 3) found significant improvement in trauma symptomology (Table 1). Information on whether improved trauma symptoms resulted in or was anticipated to improve attendance or decrease discipline referrals wasn’t reported. The use of evaluation plans for outcomes would be a valuable addition to effectiveness studies.

Trauma-informed schools literature suggests such approaches will, over time, lead to improvements in student attendance, engagement with learning and academic outcomes (Giboney Wall 2020; Goss et al. 2017). In the current review only Dorado et al. (2016) collected student engagement, time in class and school attendance data. Academic outcomes, such as student achievement in core curriculum areas, was not reported in the current studies, an important factor to include in future research endeavours, likely requiring longitudinal approaches. Certainly, the various elements of a trauma-informed school, such as social and emotional wellbeing (Atallah et al. 2019; CASEL 2014) and strengths-based relational practices (Grossman 2005; Waters 2011) have strong evidence linking them to improved learning outcomes.

Implementation Learnings

To support practice change in complex systems such as schools, prior consideration needs to be given to whether the multiple components in the system will support or hinder the proposed change (Cole et al. 2005; Fixsen et al. 2015). Although the implementation stories in the current studies are limited, there are a number of learnings that can inform future work, save resources and avoid challenges.

Pre-Intervention

Pre-intervention considerations of school readiness, motivation, leadership buy-in and adequate systems were seen as fundamental to the success of the intervention, along with consideration of how the intervention aligns with the core values and needs of the school and infra-structure such as policies and procedures. Two studies (Perry and Daniels 2016; Day et al. 2015) included implementation workshops and two included the collaborative bespoke design of training to match school needs in support of implementation endeavors (Dorado et al. 2016; Perry and Daniels 2016). The TLPI demonstration schools’ study (Jones et al. 2018) highlights the importance of school readiness factors for successful engagement in a process of change and the importance of considering individual school contexts and collaborative approaches.

Translation of Knowledge to Practice

Attention to the translation of knowledge into practice was seen as critical and found to be supported by the use of teacher coaching models including such elements as regular individual supervision or small group sessions (Day et al. 2015; Dorado et al. 2016), workshops (Perry and Daniels 2016) and in-class and in the moment support from a specialist (Perry and Daniels 2016). Those studies using coaching and supervision (Day et al. 2015; Dorado et al. 2016) considered these elements to have strengthened practice and organizational change, consistent with research linking the provision of ongoing support to teachers to positive student outcomes (Artman-Meeker et al. 2014; Gray et al. 2015). Two strong recommendations in the current studies were provision of initial staff training as an intensive two-day approach to achieve a culture shift (Parris et al. 2015; Perry and Daniels 2016) with the structure and focus of the training developed in partnership with school leadership, and that teachers’ have space to debrief and discuss struggles on a regular and ongoing basis. The application of implementation science to improve the translation of knowledge into practice (Proctor 2012) is emerging in education, offering important insights, methods and frameworks for the development of trauma-informed school systems (Albers and Pattuwage 2017; Mitchell 2011).

Implementation Length

In the longer studies (over 12 months) (Dorado et al. 2016; Parris et al., 2015), a strong relationship was found between implementation length and reduction in the number and severity of behavioural incidences. Additional elements supporting implementation within the current studies included revision of communication protocols with staff, students, parents and community agencies (Dorado et al. 2016; Perry and Daniels 2016) and the use of care co-ordination teams along with interagency and researcher collaborations (Dorado et al. 2016; Perry and Daniels 2016). Collaboration and implementation practices may hold an important key to achieving trauma-informed change and improved outcomes for students, an area needing further exploration. Sustainability learnings inherently require longitudinal studies, beyond the two-year period of the longest of the current studies.

Limitations

Caution is required when evaluating effectiveness of the models included in this study and when making causal links between the intervention components and the outcomes obtained, given the small number of studies meeting inclusion criteria and the lack of homogeneity between studies precluding the use of meta-analysis to generate effect size estimates. Although not a limitation in design, the elimination of over 7000 papers may raise concerns, given the appetite for trauma-informed schools, as to whether schools are currently using evidence-based practices. It is not uncommon to capture large numbers of false positives, papers that may have been relevant but on detailed investigation turned out not to be so, as systematic literature reviews are primarily concerned with aggregating empirical evidence. Although the number of false positives was high in the current review, it is expected that the protocol acted to prevent the search under-representing the available evidence while allowing for the refinement of results through screening against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A limiting factor within the search criteria is the restriction to studies published in English, which is likely to have precluded international papers of interest.

Future Research and Implications

Although there is both great enthusiasm for and an ever-expanding range of, trauma-informed approaches in schools, the small number of published studies meeting the SAMSHA criteria highlights a number of areas of focus for future research. Firstly, a greater understanding is needed regarding barriers to school-based research and how to mitigate these to support the growth in empirical research and analysis. Funding, as cited by two studies (Day et al. 2015; Perry and Daniels 2016), can restrict data-collection options, a constraint highlighting the importance of adequate resourcing and support for research endeavours. Secondly, improvements in research design could increase the power of studies, including larger samples, longitudinal studies and reducing the risk of bias by improvements to participant blinding, accounting for confounders and participant retention. Consideration of how to apply rigor to studies in schools that do not lend themselves easily to RCT approaches will be an interesting and important research challenge. Additionally, the range of stakeholder views regarding interventions under investigation needs extending beyond the consideration of school staff, to represent all stakeholders, especially the views of students and caregivers. Importantly, accuracy of results will be heightened through the triangulation of multiple stakeholder views and outcomes.

There is a need for continued development of psychometrically sound tools (Champine et al. 2019) for schools to identify strengths and needs, measure the extent to which a trauma-informed culture has developed, including shifts in teacher mind-set, the relationships and connections between school, students and families, and monitor progress toward outcome goals. Measures of whether students, staff, and family feel an increased sense of safety and support at school will be an important inclusion in future studies. Critically, measuring program fidelity, whether the intervention was implemented as intended, will improve analysis of outcome strength and how this relates to the focus of the program elements. As a primary aim of schools has been to educate and to nurture successful life-long learners, evaluating the academic impact of trauma-informed school approaches will be an important addition to future research.

Future research effort and analysis is needed to better understand the impact factors of individual elements of a trauma-informed school and, importantly, how the multiple elements interact together (Jones et al. 2018). Consideration of impact factors is significant given limitations and many competing demands on school resources. Equally, there is a need to consider the role of teaching pedagogies, integrated practices and the use of an inquiry approach to school culture change. Factors that support the embedding, use and transferability of school-wide approaches will be areas to include in future research, along with exploring responsive measures of trauma-informed paradigm shift. Finally, the application of implementation science to improve the translation of knowledge into practice (Proctor 2012) although emerging in education, offers important insights, methods and frameworks for the development of trauma-informed school systems (Albers and Pattuwage 2017; Mitchell 2011).

Despite the restrictions of the current published studies, the preliminary findings of this review add to the existing anecdotal evidence for trauma-informed school-wide approaches. Related to this, is the need to better understand and respond to the intersections of trauma with culture, history, race, gender and poverty. Cole et al. (2005) recommend that trauma-sensitive approaches work best and are sustainable when “woven into the fabric of the school”, p. 48, and are part of the usual conditions, rather than being an adjunct to school programmes. Additionally, the social context of trauma and the potential use of relationship as intervention, common to many therapeutic approaches, is a significant area for future focus within the school context. Future work may be guided by an understanding that complex issues of trauma within schools, that are themselves complex environments, is likely to require flexible, tailored and contextualised approaches which could challenge scientifically rigorous study (Cole et al. 2013).

Conclusion

In conclusion, the impact of trauma on individuals is well evidenced and the interest in using trauma-informed school approaches to ameliorate that impact is rapidly accelerating. Limitations in the research and the overall lack of studies indicate more rigorous collaborative research is needed to determine which approaches contribute to what positive outcomes, for which students and under what conditions. This is complex but critical work for practitioners and researchers alike, requiring integrated principles and strategies across the population that makes up a school and its community.

Given the significant impact and almost universal experience of trauma, there is an urgency to creating schools that can counter trauma’s effects and become cultures of safety and care, offering optimal teaching and learning environments, allowing all children and young people every opportunity for success.

Electronic supplementary material

(DOCX 13 kb)

Author Contributions

JA developed the search strategy, led the data collection and analysis, and drafted the manuscript. HM contributed to guiding the review process, data analysis, and revision and editing of the manuscript. EM analysed 25% of papers against inclusion/exclusion criteria and assessed all final studies for risk of bias. MM guided the review process, methodological design, search strategy, and analysis and interpretation of data. MS contributed to the database search and analyzed 25% of the papers for inclusion/exclusion. HS determined the design and scope of the review, edited the manuscript, supervised the review process, and is the guarantor for ensuring the integrity and accuracy of the review data.

Funding

No funding was received for this research.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

As the research did not involve collection of data from human subjects, it did not need to be approved by an organizational unit responsible for the protection of human participants.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Helen Skouteris is a senior author

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

10/7/2020

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s40653-020-00326-w

References

- Albers B, Pattuwage L. Implementation in education: Findings from a scoping review. Melbourne: Evidence for Learning; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Alderson P. Research by children. International Journal of Social Research Methodology. 2001;4:139–153. doi: 10.1080/13645570120003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Artman-Meeker K, Hemmeter ML, Snyder P. Effects of distance coaching on teachers’ use of pyramid model practices: A pilot study. Infants & Young Children. 2014;27(4):325–344. doi: 10.1097/IYC.0000000000000016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atallah DG, Koslouski JB, Perkins KN, Marsico C, Porche MV. An evaluation of Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative’s (TLPI) inquiry-based process: Year three. Boston: Boston University, Wheelock College of Education and Human Development; 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson J. Aboriginal Australia – trauma stories can become healing stories if we work with therapeutic intent. In: Richard B, Haliburn J, King S, editors. Humanising mental health care in Australia: A guide to trauma-informed approaches. New York: Routledge; 2019. pp. 133–142. [Google Scholar]

- Bateman J, Henderson C, Kezelman C. Trauma-informed care and practice: Towards a cultural shift in policy reform across mental health and human services in Australia. A national strategic direction. Lilyfield: Mental Health Coordinating Council; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Becker-Blease KA. As the world becomes trauma-informed, work to do. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2017;18:131–138. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2017.1253401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berger, E. (2019). Multi-tiered approaches to trauma-informed care in schools: A systematic review. School Mental Health, 11(4), 650–664.

- Blaustein M, Kinniburgh K. Treating traumatic stress in children and adolescents: How to foster resilience through attachment, self-regulation, and competency. New York: The Guilford Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Blodgett C, Dorado J. A selected review of trauma-informed school practice and alignment with educational practice. CLEAR-trauma-informed-schools-white-paper. San Francisco: California Endowment; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom SL. Advancing a national cradle-to-grave-to-cradle public health agenda. Journal of Trauma & Dissociation. 2016;17(4):383–396. doi: 10.1080/15299732.2016.1164025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloom SL. Encountering trauma, countertrauma, and countering trauma. In: Gartner RB, editor. Trauma and countertrauma, resilience and counterresilience. London: Routledge; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Bloom SL. Trauma theory. In: Richard B, Haliburn J, King S, editors. Humanising mental health care in Australia: A guide to trauma-informed approaches. New York: Routledge; 2019. pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Brunzel T, Stokes H, Waters L. Shifting teacher practice in trauma-affected classrooms: Practice pedagogy strategies within a trauma-informed positive education model. School Mental Health. 2019;11:600–614. doi: 10.1007/s12310-018-09308-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CASEL. (2014). Collaborative for Academic, Social, and Emotional Learning. 2013 CASEL guide: Effective social and emotional learning programs (Preschool and elementary school edition). Chicago, IL. https://casel.org/library/2013-casel-guide-effective-social-and-emotional-learning-programs-preschool-and-elementary-school-edition-2013/

- Chafouleas S, Johnson A, Overstreet S, Santos N. Toward a blueprint for trauma-informed service delivery in schools. School Mental Health. 2016;8:144–162. doi: 10.1007/s12310-015-9166-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Champine, R. B., Lang, J. M., Nelson, A. M., Hanson, R. F., & Tebes, J. K. (2019). Systems measures of a trauma-informed approach: A systematic review. American Journal of Community Psychology, 64(3–4), 418–437. 10.1002/ajcp.12388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Clark JP, Alvarez ME, editors. Response to intervention: A guide for school social workers. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Cole SF, O’Brien JG, Gadd MG, Ristuccia J, Wallace DL, Gregory M. Helping traumatized children learn: Supportive school environments for children traumatized by family violence. Boston: Massachusetts Advocates for Children; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Cole SF, Eisner A, Gregory M, Ristuccia J. Helping traumatized children learn: Creating and advocating for trauma-sensitive schools. Boston: Massachusetts Advocates for Children; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Day AG, Somers CL, Baroni BA, West SD, Sanders L, Peterson CD. Evaluation of a trauma-informed school intervention with girls in a residential facility school: Student perceptions of school environment. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2015;24(10):1086–1105. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2015.1079279. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dixon J, Biehal N, Green J, Sinclair I, Kay C, Parry E. Trials and tribulations: Challenges and prospects for randomised controlled trials of social work with children. British Journal of Social Work. 2014;44(6):1563–1581. doi: 10.1093/bjsw/bct035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dorado JS, Martinez M, McArthur LE, Liebovitz T. Healthy Environments and Response to Trauma in Schools (HEARTS): A school-based, multi-level comprehensive prevention and intervention program for creating trauma-informed, safe and supportive schools. School Mental Health. 2016;8:144–162. doi: 10.1007/s12310-016-9177-0. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, Reid R, Anastopoulos AD, Power TJ. Assessing ADHD symptomatic behaviors and functional impairment in school settings: Impact of student and teacher characteristics. School Psychology Quarterly. 2014;29(4):409–421. doi: 10.1037/spq0000095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felitti VJ, Anda RF, Nordenberg D, Williamson DF, Spitz AM, Edwards V, Marks JS. Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 1998;14(4):245–258. doi: 10.1016/S0749-3797(98)00017-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Figlio, D., Karbownik, K. & Salvanes, K.G. (2015). Education research and administrative data. Handbook of the Economics of Education, 5 IZA DP (9474), 4–89.

- Finkelhor, D., Turner, H.A., Shattuck, A. & Hamby, S. L. (2015). Prevalence of childhood exposure to violence and crime and abuse: Results from the National survey of children’s exposure to violence. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jamapediatrics/article-abstract/2344705. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Fixsen D, Blase K, Naoom S, Duda M. Implementation drivers: Assessing best practices. Chapel Hill: National Implementation Science Network (NIRN); 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Fonagy P, Target M, Gergely G, et al. The developmental roots of borderline personality disorder in early attachment relationships: A theory and some evidence. Psychoanalytic Inquiry. 2013;23(3):412–459. doi: 10.1080/07351692309349042. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ford JD, Courtois CA. Treating complex traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: An evidence-based guide. New York: Guilford; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Giboney Wall, C. R. (2020). Relationship over reproach: Fostering resilience by embracing a trauma-informed approach to elementary education. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 10.1080/10926771.2020.1737292.

- Goss, P., Sonnemann, J. & Griffiths, K. (2017). Engaging students: Creating classrooms that improve learning. Grattan Institute. https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2017/02/Engaging-students-creating-classrooms-that-improve-learning.pdf

- Gray HL, Contento IR, Koch PA. Linking implementation process to intervention outcomes in a middle school obesity prevention curriculum, ‘choice, control and change’. Health Education Research. 2015;30(2):248–261. doi: 10.1093/her/cyv005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossman PL. Research on pedagogical approaches in teacher education. In: Cochran-Smith M, Zeichner K, editors. Review of research in teacher education. Washington, DC: American Educational Research Association; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Jernberg AM, Booth PB. Theraplay: Helping parents and children build better relationships through attachment-based play. 2. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Jimerson SR, Burns MK, VanDerHeyden AM. Response-to-intervention at school: The science and practice of assessment and intervention. In: Jimerson SR, Burns MK, Van DerHeyden AM, editors. Handbook of response to intervention: The science and practice of assessment and intervention. New York: Springer; 2007. pp. 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Jones W, Berg J, Osher D. Trauma and Learning Policy Initiative (TLPI): Trauma-sensitive schools descriptive study: Final report. Washington, DC: American Institutes for Research; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Maynard, B. R., Farina, A. & Dell, N. A. (2018). Effects of trauma-informed approaches in schools. Retrieved from https://campbellcollaboration.org/media/k2/attachments/ECG_Maynard _Trauma-informed_approaches.pdf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, E. M., Baker, C. N., Overstreet, S., & The New Orleans Trauma-Informed Schools Learning Collaborative. (2019). Evaluating foundational professional development training for trauma-informed approaches in schools. Psychological Services, 16(1), 95–102. 10.1037/ser0000312. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McLaughlin KA, Koenen KC, Hill ED, Petukhova M, Sampson NA, Zaslaysky AM, Kessler RC. Trauma exposure and posttraumatic stress disorder in a national sample of adolescents. Journal of American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2013;52(8):815–830. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell PF. Evidence-based practice in real-world services for young people with complex needs: New opportunities suggested by recent implementation science. Children and Youth Services Review. 2011;33(2):207–216. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.10.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mohatt NV, Thompson AB, Thai ND, Tebes JK. Historical trauma as public narrative: A conceptual review of how history impacts present-day health. Social Science Medicine. 2014;106:128–136. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2016). National child traumatic stress network empirically supported treatments and promising practices. Retrieved from http://www.nctsn.org/resources/topics/treatments-that-work/promising-practices.

- National Child Traumatic Stress Network. (2017). Trauma-informed care: Creating trauma-informed systems. Retrieved from https://www.nctsn.org/trauma-informed-care/creating-trauma-informed-systems.

- Overstreet S, Chafouleas SM. Introduction to the special issue. School Mental Health. 2016;8:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s12310-016-9184-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parris SR, Dozier M, Purvis KB, Whitney C, Grisham A, Cross DR. Implementing trust-based relational intervention® in a charter school at a residential facility for at-risk youth. Contemporary School Psychology. 2015;19:157–164. doi: 10.1007/s40688-014-0033-7. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perfect MM, Turley MR, Carlson JS, Yohanna J, Saint Gilles MP. School related outcomes of traumatic event exposure and traumatic stress symptoms in students: A systematic review of research from 1990–2015. School Mental Health. 2016;8:7–43. doi: 10.1007/s12310-016-9175-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Perry DL, Daniels ML. Implementing trauma-informed practices in the school setting: A pilot study. School Mental Health. 2016;8:177–188. doi: 10.1007/s12310-016-9182-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pinnock, H., Epiphaniou, E., Sheikh, A., Griffiths, C., Eldridge, S., Craig, P., Taylor S. J. C. (2015). Developing standards for reporting implementation studies of complex interventions (StaRI): a systematic review and e-Delphi. Implementation Science, 10(1). 10.1186/s13012-015-0235-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Porche MV, Costello DM, Rosen-Reynoso M. Adverse family experiences, child mental health, and educational outcomes for a national sample of students. School Mental Health. 2016;8:44–60. doi: 10.1007/s12310-016-9174-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Proctor E. Implementation science and child maltreatment. Child Maltreatment. 2012;17(1):107–112. doi: 10.1177/1077559512437034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purtle, J. (2018). Systematic review of evaluations of trauma-informed organizational interventions that include staff trainings. Trauma, Violence & Abuse,4, 1–16. 10.1177/1524838018791304. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Rowe F, Stewart D, Patterson C. Promoting school connectedness through whole school approaches. Health Education. 2007;107(6):524–542. doi: 10.1108/09654280710827920. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration . SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. HHS publication no. (SMA) 14–4884. Rockville: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Teicher, M. H., Khan, A. (2019). Childhood Maltreatment, Cortical and Amygdala Morphometry, Functional Connectivity, Laterality, and Psychopathology. Child Maltreatment, 24(4), 458–465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Thomas B, Ciliska D, Dobbins M, Micucci S. A process for systematically reviewing the literature: Providing the research evidence for public health nursing interventions. Worldviews on Evidenced-Based Nursing. 2004;1(3):176–184. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-475X.2004.04006.x/full. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas SM, Crosby S, Vanderharr J. Trauma-informed practices in schools across two decades: An interdisciplinary review of research. Review of Research in Education. 2019;43(1):422–452. doi: 10.3102/0091732X18821123. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations General Assembly. (1989). United nations convention on the rights of the child. Retrieved from https://www.refworld.org/docid/3ae6b38f0.html

- Van der Kolk BA. The developmental impact of childhood trauma. In: Kirmayer LJ, Lemelson R, Barad M, editors. Understanding trauma: Integrating biological, clinical and cultural perspectives. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University press; 2007. pp. 224–241. [Google Scholar]

- Waters L. A review of school-based positive psychology interventions. The Australian Educational and Developmental Psychologist. 2011;28(2):75–90. doi: 10.1375/aedp.28.2.75. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolpow R, Johnson MM, Hertel R, Kincaid SO. The heart of learning and teaching: Compassion, resiliency, and academic success. Olympia: Washington State Office of Superintendent of Public Instruction Compassionate Schools; 2009. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data