Abstract

The study aimed to evaluate Teaching Recovery Techniques (TRT) delivered to Brazilian youth who experienced drug violence in one Favela. Thirty children, 8 to 14 years, were randomly assigned to TRT (n = 14) or to a treatment as usual group (n = 16) involving boxing/martial arts. Youth received five 90-min sessions over successive weeks. Standardized measures assessed Posttraumatic Stress and Depression at 2 weeks pre and post-test. An exploratory assessment of posttraumatic growth was also utilized. An interview with group leaders explored perceptions of delivering TRT within the favela. Medium effect sizes were found for PTSD and Depression, and a small effect size for posttraumatic growth. Group leaders emphasized understanding the favela context for program adaptation. In conclusion, TRT was found to be effective for children with PTSD and Depression who experienced drug violence in a Brazilian favela. TRT is recommended for future delivery. Larger scale RCTs are needed in Brazilian favelas.

Keywords: PTSD, Drug gangs, Favelas, Youth, Depression

Research in Brazil has increasingly explored both the prevalence and association of violence and mental health (Andreoli et al. 2009; Teche et al. 2017). The prevalence of psychiatric disorders in urban centers in Brazil has been linked to high rates of exposure to traumatic events, such as assaultive violence, natural and human-made disasters, witnessing a shoot-out, seeing or touching a corpse, and witnessing atrocities (Ribeiro et al. 2013). Brazilian youth face high odds of being the primary perpetrators as well as victims of violence in the community (Faus et al. 2019). Sexual abuse and exploitation, psychological and physical violence, and neglect have been registered as the main reasons for attention from Brazilian social welfare centers for children under 14 years of age (Cardia et al. n.d.). Poverty, maternity psychiatric illness, and violence have been found to be strongly associated with higher rates of psychiatric disorders amongst Brazilian youth aged 7 to 14 (Fleitlich and Goodman 2001). The World Health Organization estimates that mental health problems affect 10–20% of children worldwide, compared to 12% to 25% of Brazilian children and adolescents and almost 100% involved in the country’s justice system (Ribeiro et al. 2019).

Exposure to traumatic events has been found to be higher for urban Brazilians who are under 24 years of age, and those with such exposure have significantly higher rates of substance abuse, depression, and anxiety disorders in adulthood (Jaen-Varas et al. 2016). Childhood abuse as well as neglect have been found to predict post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) among low-income adults or to be frequent among patients with depression and/or dependency issues in Brazil (Grassi-Oliveira and Stein 2008; Tucci et al. 2010; Pupo et al. 2015). Brazilian studies have also linked childhood trauma to bipolar disorder and clinical outcomes such as higher severity of depressive symptoms, prevalence of suicide risk, and global functioning impairment when compared to subjects with bipolar disorder without childhood trauma (Farias de Azambuja et al. 2019; Barbosa et al. 2014). Although epidemiological data on the psychiatric impact of traumatic events during childhood has begun to accumulate over the last decade, evaluations of empirically-based treatment are sparse (Curto et al. 2011; de Assis et al. 2013; Costa et al. 2017).

In order to address the experiences of drug and gang violence in Brazilian favelas for children and adolescents who present with trauma symptoms, the current study aimed to deliver the empirically-based trauma-specific program, the Teaching Recovery Techniques (TRT). Favelas are shanty towns, slums or Brazilian shacks on the edge of Rio de Janeiro and Sao Paulo. It is vacant land at the edge of a city that becomes occupied by squatters using salvaged or stolen materials (Encyclopedia Britannica 2009). TRT has been successfully delivered in a range of contexts that similarly involve cumulative military and domestic violence (Barron et al. 2013; Barron et al. 2016); unaccompanied refugee minors (Sarkadi et al. 2018); and war exposed adolescents in Bagdad (Ali et al. 2019). Studies indicate that a short-duration program can significantly reduce posttraumatic stress compared to waitlist groups (Barron et al. 2013; Barron et al. 2016). To date, however, no studies have specifically examined TRT in Brazil, although a few experimental studies have examined the effectiveness of group-based therapies amongst Brazilian children and adolescents in improving mental health.

The most recent study to evaluate the effects of group CBT (GCBT) in Brazil, utilized a longitudinal follow-up that investigated the psychopathological trajectories of youth with pediatric Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD) (Fatori et al. 2019). At 7–9 years follow up, over two-thirds of the original participants had at least one mental disorder, including OCD. The study found that being treated for OCD with GCBT in the original RCT did not predict OCD at follow-up. The study did not describe the socio-economic or geographic location of the participants at follow-up, though the original study (Asbahr et al. 2005) mentioned that the participants were 9–17 years old and from the major urban center of Sao Paolo.

Waldemar et al. (2016) conducted what they believed to be the first study of a school-based Mindfulness and Socio-Emotional Learning (M-SEL) Program, with 132 fifth graders, half of whom where white and a majority of whom were low-middle class, in three public schools in the southern city Porto Alegre. The researchers sought to evaluate the impact of this intervention on psychological outcomes including mental health (emotion, conduct, hyperactivity, relationships, and prosocial behavior), attention deficit/hyperactivity (ADHD) symptoms, and quality of life through a quasi-experimental design. The results indicated that over the course of twelve 1-h long interventions, the M-SEL program produced significant effects on symptoms related to emotional problems, conduct problems, interpersonal relationships, prosocial behavior, and quality of life (Waldemar et al. 2016).

A quasi-experimental study by Habigzang et al. (2016) examined differences by provider of cognitive behavioral group therapy (GCBT). They drew on findings from a previous study by Habigzang et al. (2013), which had evaluated a GCBT model for the treatment of PTSD, anxiety, and depression. In this initial evaluation of the group CBT treatment model, the researchers noted that in one experimental group, only a quarter of the participants had received immediate attention after reporting the abuse, while half waited between one and 6 months for treatment, and a quarter waited more than 6 months. Nevertheless, Habigzang et al. (2016) found that amongst the total sample of 103 girls aged 9 to 16 who had survived sexual violence, GCBT was associated with a significant reduction in symptoms across groups, with no differences by type of practitioners administering the intervention.

Asserting a lack of professionals qualified to conduct CBT with children and adolescents as well as the non-existence of empirical studies on group CBT in Brazil, De Souza et al. (2013) set out to examine group CBT among youth with anxiety disorders. Twenty participants aged 10 to 13 with at least one anxiety disorder diagnosis completed the 14-weeks long treatment. This consisted of 90-min sessions based on a recognized protocol delivered by two clinical psychologists supervised by researchers with over 10 years of relevant experience. Scores on self- and parent-measures of anxiety improved and externalizing symptoms reduced significantly over time with moderate to large effect sizes, but not in depressive symptoms, and there was no change in quality of life scores. The De Souza et al. (2013) study did not report on the socio-economic or geographic origins of the participants or their families.

Methods

The current study then, aimed to (i) address the lack of trauma-specific programs for dealing with PTSD and (ii) provide a rigorous approach to evaluating program efficacy. The study utilized a small-scale randomized control trial followed by an interview with group leaders. The latter aimed to identify potential factors associated with delivering TRT in the Brazilian favelas that could impact on program delivery and lead to program adaptation. Ethical approval was obtained from a Scottish University Research Ethics Committee. The researcher in the field was a male bilingual PhD student in his twenties at a local Brazilian University who had experience of implementing experimental design research. The researcher was supported by the Principle Investigator in the USA.

Participants

Complexo da Maré, a group of favelas in Rio de Janeiro was selected because of the high levels of drug and community violence as well as scarcity of support services. Fight for Peace (FFP: Luta Pela Paz), a NGO that uses boxing and martial arts as a means of outreach work to youth involved with violence, guns, and drugs, sought to embed a trauma-specific intervention into their youth work. Two female Luta Pela Paz workers, one a social worker, the other a teacher, aged 25 and 35 respectively, were trained over 3 days by a Children and War expert in TRT. Training covered TRT theory, group processes, and the importance of following scripted instructions. Training methods included information giving, modeling, experiential learning, reflection, and feedback.

From a corpus sample of 82, n = 52 were excluded from the study. There were four reasons why children in the corpus sample were not able to participate in the study. Twenty children were unable to participate due to incompatible schedules with other activities, mainly school. Two parents could not transport their child to FFP at the designated times. Eight children lived too far from the FFP building to participate in TRT and finally, the intensification of armed conflicts in the FFP area a few weeks before TRT started, prevented parents from releasing children (n = 16). Only two children males, aged 12 years, directly declined to participate. No reason was given, however, one boy later said “he regretted it” after hearing a friend who participated in TRT talk about his experiences. This may indicate a degree of apprehension in his decision not to be involved.

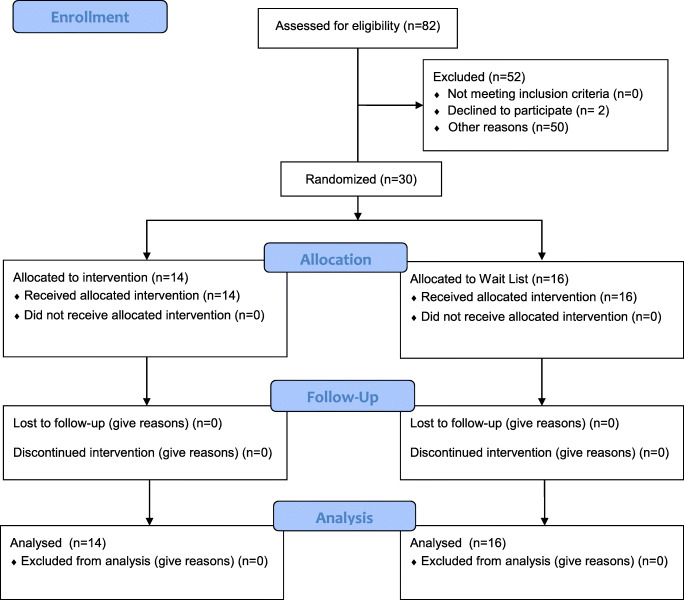

As a result, n = 30 youth were randomly allocated to the TRT group intervention (n = 14) and a treatment as usual group (n = 16), the latter receiving martial arts and boxing classes. The whole sample age range was 8 to 13.10 years, with a mean of 10.1 years (SD = 1.70). The intervention group age range was 8.5 years to 13.10, with a mean of 10.8 years (SD = 1.73). The Wait List control group similarly ranged from 8.3–12.7 years with a mean of 9.5 (SD = 1.51). There were 7 females and 7 males in the TRT group and 9 male and 7 females in the Wait List control group (see Fig. 1 Consort diagram). All participants were indigenous to Brazil. In the intervention five were Caucasian and there were three Caucasian children in the Wait List group. Half the sample were from working class families and half from middle class families. The socio-economic spread across the two groups were as follows: intervention group: 9 working class, 5 middle class and Wait List control group: 6 working class, 10 middle class.

Fig. 1.

Consort flow diagram

Intervention

TRT (Smith et al. 2018) is a psychosocial coping skills program based on cognitive behavioral theory. Five 90-min sessions address the 3-core axis of posttraumatic stress disorder symptoms. Sessions, delivered by the two group leaders (teacher and social worker), were delivered over 5 consecutive weeks. Sessions involved psychoeducation through case studies to normalize the reactions to adverse childhood experiences. Activities include creating a sense of safety, creative visualizations to deal with intrusive and triggered memories, a range of relaxation exercises to calm the body and systematic desensitization to help children and adolescents address avoidance behaviors. The final session focused on response to loss. TRT was blind-back translated and delivered in Portuguese (McDermott and Palchanes 1994). Sessions were delivered during the day when the Wait List group experienced their usual boxing and martial arts activities. Children and adolescents in the Wait List group received the TRT following post-testing.

Program Fidelity

TRT implementation fidelity was assessed through completion of a program adherence checklist by each group leader independently following each session. Fidelity was rated on a 0 to 10 scale where 0 equaled no protocol adherence at all compared to 10 where protocols were fully followed. Group leaders were asked to record any protocol adaptations.

Measures

Standardized measures were used to assess posttraumatic stress, depression and posttraumatic growth. All measures were blind-back translated into Portuguese by the research and another project worker. The Children’s Revised Impact of Events Scale (CRIES-13) measures symptoms of intrusion, avoidance, and arousal, 13 items on a 4-point scale (not at all, rarely, sometimes, often). The CRIES-13 shows good internal consistency with a Cronbach alpha coefficient of .80 (Smith et al. 2003). A cut-off of 17 or more (indicating the probability of PTSD) on the intrusion/avoidance subscales (8 items) was used for screening.

The Moods and Feelings Questionnaire (MFQ), short version, measures the extent of children and adolescents’ depressive symptoms. Thirteen depressive items are rated on a 3-point scale (not true, sometimes, true). A cut-off of 12 or more indicated the probability of a depressive disorder. The MFQ has been found to have good reliability (Thabrew et al. 2018).

The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (PTGI: Tedeschi and Calhoun 1996). was utilized as an exploratory measure to identify potential aspects of growth. The PGTI is short and simple to complete and consists of five dimensions: personal strength, new possibilities, relating to others, appreciation of life, and spiritual change. The scale includes 21 items, with responses on a six-point scale from 0 = no change to 5 = very great degree of change. The reliability of the each of the translated measures was high with the following Cronbach Alpha coefficients for CROPS (.91) and MFQ (.84); and medium reliability for the PTGI (.73).

Group Leaders’ Interview

Group leaders were interviewed to discover their subjective experience of delivering TRT and their perceptions of how children experienced TRT. Group leaders were interviewed together in order to stimulate discussion to identify more issues with a small sample. Questions included presenter experience of delivering TRT; perception of participant experience; benefits of TRT and improvements observed; any negative experience during or after TRT; whether materials were understandable; TRT fit to Favela culture and changes needed for future delivery. The interview lasted an hour and was held in a private space within the Luta Pela Paz building. The two group leader interview was digitally recorded and translated into English.

Analysis

Quantitative data from the standardized measures was analyzed using paired t-tests (pre/post-test) and analysis of covariance comparing intervention and wait-list groups. Effect sizes were calculated using cohen’s d and reported as partial eta. The analysis of interview responses involved an adapted Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step systematic thematic analysis. Steps in the process involved familiarization with the data, generating initial codes, the search for themes, reviewing and naming of themes, and drafting the report. Interview responses were analyzed initially by the researcher in the field. The interview responses were then translated into English for the Western researcher to analyze the data to provide a measure of inter-related reliability.

Results

Treatment Fidelity

Treatment fidelity rating scales were completed for all sessions. Group leaders indicated they held to program protocols between 80 and 90% across the 5 sessions, with a high level of agreement between the two group leaders. Adaptations to TRT protocols included (ii) introducing a ribbon as a blindfold to help children and adolescents engage in imagining activities by reducing distractions, and (ii) providing snacks as part of gain children’s trust and engagement. More significantly, in one session, a shooting occurred outside the building. Group leaders, then, responded to children’s request to talk about the shooting within the session. Group leaders also reported giving some time for participants to raise issues that were not directly related to learning the coping skills, e.g. community or school problems.

Pre-TRT Symptoms

At pre-test, TRT and the Wait List control groups were matched for symptom severity in PTSD and Depression. All participants bar one, were above the cut-off for PTSD. In the TRT group PTSD scores ranged from 17 to 37 with a mean of 25.57 (SD = 6.477) compared to 18 to 34 with a mean of 24.69 (SD = 5.237) in the Wait List control group. No significant difference was found between the two groups F(1,28) = 0.171, p = 683 (see Table 2). No significant differences were found for age and gender.

Table 2.

TRT vs Wait list group (PTSD & Depression)

| Symptom | Group | Range | Mean | SD | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PTSD | TRT (Pre) | 17–37 | 25.75 | 6.477 | F(1,28) = 0.171, p = 683 |

| Wait List (Pre) | 18–34 | 24.69 | 5.237 | ||

| TRT (Post) | 12–13 | 15.50 | 3.590 | F(1,28) = 33.747, p < .01* | |

| Wait List (Post) | 18–32 | 24.69 | 4.868 | ||

| Depression | TRT (Pre) | 5–15 | 11.79 | 4.949 | F(1,28) = 1.470, p = .235 |

| Wait List (Pre) | 0–19 | 9.31 | 6.063 | ||

| TRT (Post) | 3–10 | 6.50 | 1.787 | F(1,28) = 23.008, p < .01* | |

| Wait List (Post) | 3–18 | 12.19 | 4.102 | ||

| Post-traumatic growth | |||||

| TRT (Pre) | 7–28 | 16.50 | 6.346 | F(1,28) = 0.259, p = .615 | |

| Waitlist (Pre) | 7–30 | 1.601 | 6.450 | ||

| TRT (Post) | 15–25 | 20.93 | 3.772 | F(1,28) = 1.446, p = .239 | |

| Waitlist (Post) | 10–28 | 18.81 | 5.552 | ||

*significant result

With Depression, n = 8 participants were at clinically significant levels in the TRT group, whereas in the Wait List all 16 participants were at clinically significant levels. In the TRT group Depression scores ranged from 5 to 19 with a mean of 11.79 (SD = 4.949) compared to 0 to 19 with a slightly lower mean of 9.31 (SD = 6.063) in the Wait List control. As with PTSD, no significant difference was found between the two groups F(1,28) = 1.470, p = .235.

Levels of Posttraumatic Growth were also similar across the two conditions. In the TRT group scores ranged from 7 to 28 with a mean of 16.50 (SD = 6.346) compared to 7 to 30 with a mean of 1.601 (SD = 6.405) in the Waitlist. No significant difference was found between the two groups F(1,28) = 0.259, p = .615.

Post-TRT Symptoms

Following delivery of TRT, the intervention group achieved significant reductions in Posttraumatic stress and Depression and showed promising gains in signs of Posttraumatic Growth.

With PTSD, a high level of significance was found between the two conditions, F(1,28) = 33.747, p < .01. Following TRT, only n = 3 participants fitted the criteria for PTSD compared to all participants continuing to be above the cut-off for PTSD in the Wait List. In the TRT group PTSD scores ranged from 12 to 23 with a mean of 15.50 (SD = 3.590) compared to a higher and wider range of 18 to 32 with a mean of 24.69 (SD = 4.868) in the Wait List.

With Depression, a similarly high level of significance was found between the two conditions following intervention with more significant improvement for the TRT group, F(1,28) = 23.008, p < .01. Indeed, n = 0 of TRT group participants fitted the criteria for Depression post-TRT. This compared to n = 11 in the Wait List, although this was n = 4 children less than at pre-test. In the TRT group post-test Depression scores ranged from 3 to 10 with a mean of 6.50 (SD = 1.787) compared to 3 to 18 with a mean of 12.19 (SD = 4.102) in the Wait List.

No significant difference was found on the experimental for posttraumatic growth between TRT and Waitlist Groups, F(1,28) = 1.446, p = .239. In the TRT group post-test Posttraumatic growth scores ranged from 15 to 25 with a mean of 20.93 (SD = 3.772) compared to 10 to 28 with a mean of 18.81 (SD = 5.552) in the Wait List group. In the TRT group n = 12 participants’ scores increased and two participants scores remained the same, compared to an increase for n = 8 and a decrease in scores for n = 6 participant, the latter potentially indicating a deterioration in signs of posttraumatic growth for some. A pattern not evident in the TRT group.

Effect Size

For the TRT program, medium effect sizes were found for PTSD (d = .64) and Depression (d = .66) whereas a small effect size was found for Posttraumatic Growth (d = .19). No participants dropped out of either the TRT or Wait List groups.

Presenter Interview Responses

In total, seven themes were identified from presenters’ statements and codes, where possible using presenters’ own language (see Table 1). In summary, presenters reported delivering TRT as a ‘Positive and developmental experience’ where the ‘Purpose, skills and application’ of TRT, became clearer within the Favela context. Presenters had to adapt to youth ‘Bringing the real world into TRT’ because of ongoing crisis in the Favelas. Workers perceived TRT as part of a ‘Developing relationship and personal growth to address sensitive issues’ for youth. Although youth initially showed ‘Avoidance’ this persisted in only one youth with severe mental health difficulties. Presenters emphasized the importance of ‘Preparation, adaptation, support, and trust in the process’ to facilitate TRT efficacy. Finally, presenters emphasized ‘The centrality of context’ in adapting TRT.

Table 1.

Presenter Themes, codes and quotes

| Themes | Codes |

|---|---|

| Positive and developmental experience. | Anxious to begin; Needed to reframe what’s normal; Enabled a growing bond; more confidence over time. |

| Learning purpose, skills and application. | Curiosity; Confusion of purpose vs. understand over time; Opportunity to share; Learning and using coping skills. |

| Bringing the real world into TRT. | Immediacy of violence; Need to share in TRT; Presenter uncertainty; Child-based solutions; Learning a ‘safe place’ together. |

| Developing relationship and personal growth to address sensitive issues. | Overcoming resistance; Boosting self-esteem; Getting to know each other; Affection and bonding; New experiences; Addressing sensitive issues; Trust. |

| Avoidance. | Initial reluctance; Severe individual problems |

| Preparation, adaptation, support, and trust in the process. | Rehearsal; Adaptation of language; Facilitating concentration, Support beyond sessions; Parental avoidance and incentives, incentives for children; Introducing resources; It’s the TRT activities that work. |

| The centrality of context. | Context analysis; Addressing embeddedness and conflict of drug gangs; Highlight coping skills; Child loneliness and over-independence; Intrusion of armed conflict; Normalizing reactions not violence; Addressing gender beliefs and behavior; Influence of drug gangs. |

Group Leaders Experience

Four codes were identified under the theme positive and developmental experience. These included: anxious to begin; needed to reframe what’s normal; enabled a growing bond; and more confident over time. TRT was reported as a “positive experience” for group leaders. Initially, group leaders felt “afraid of what might happen” but felt “more secure over time.” This was due to TRT raising issues not normally discussed “Like what are you afraid of … What are your anxieties?” We needed to teach them “It is normal to be afraid.” These questions, were however a break with the protocol, as the manual encourages participants to list what children could be afraid of in general. The group leaders also reported “having more time during TRT” enabled “a greater bond between us and the children.” The moments created the opportunity “to listen and talk … that not everything … present in our daily lives, is normal and we do not have to get used to it” such as “someone shot in the street.” (see Table 1).

Perception of Child Experience

Four codes were identified under the theme learning purpose, skills and application. The codes were: curiosity; confusion of purpose vs. understanding over time; opportunity to share; and learning and using coping skills. Children were reported as “curious at first” as many children thought … they would talk about their anguish, and a psychologist would give the solution to it.” One child thought the focus would be on individual problems, such as “self-esteem, bullying, and problems at home.” Understanding of TRT occurred “little by little as children discovered “they could express themselves, but it was not … therapy between us and them” and “solution to problems that sometimes have no easy solution.” Group leaders aimed to give children “mechanisms to deal with varied situations that they live, learning the techniques to deal with frustrating situations.”

Impact of ‘Present’ Violence

The theme was bringing the real world into TRT. Codes were: immediacy of violence; need to share in TRT; presenter uncertainty; child-based solutions; and learning a ‘safe place’ together. Group leaders highlighted how the immediacy of violence in children’s lives was brought into TRT sessions. “… the brother of a young girl in TRT took a shot and died in the operation … another cousin of one of the children was shot on the same day. They brought these questions to TRT.” In addition, children referred to a recent situation where the police flew into the favela and shot randomly down at the streets below, “helicopters were flying shooting from the sky, so children were scared.” Group leaders questioned how they “could create a safe place this context?” Despite this, one boy drew a beach (his safe place) and in the fifth session drew it again, remembering what works” and “we even named the group ‘Safe Place’. How can we imagine a safe place in an extremely insecure place? But the children brought this to us, the possibility of imagining the group as a safe place in an insecure contest. And at that time we learned from them.”

Benefits and Changes

The identified theme was developing relationship and personal growth to address sensitive issues. The codes under this theme were: overcoming resistance; boosting self-esteem, getting to know each other; affection and bonding; new experiences; addressing sensitive issues; trust.

“Children came asking if they could participate again - it was this moment of welcome, of being heard, and being able to share.” In reference to a girl who didn’t want to participate initially, “at the end she did not want to leave and asked for more sessions.” TRT was also seen as addressing “home issues of parental aggression.” TRT was also reported to raise children’s self-esteem from “I cannot do it, cannot think to being able to “dream”. TRT also offered “contact, dialogue and knowing each other … something they do not have at home,” and to some extent addressing the “forced independence … and need for affection.” Finally, TRT was seen as “strengthening the bond with FFP because I am here as a social worker and x as a teacher and we have never had an opportunity to have contact with children addressing these sensitive issues.” In this regard TRT was seen as helping children and others understand and trust their role in FFP.”

Unanticipated Negative Consequences

The only negative theme raised was that of avoidance associated with two codes: initial reluctance; and severe individual problems. Children were initially reluctant to attend TRT “because thought they would have a psychological treatment.” However, group leaders emphasized this avoidance was specific to individual children who had “specific problems that could not be solved in TRT and who needed psychological treatment for other issues.” In short, anticipatory anxiety associated with not understanding the nature of TRT led to some children avoiding TRT, thinking it was a therapy.

Use of Materials

The theme was preparation, adaptation, support, and trust in the process. Codes were: rehearsal; adaptation of language; facilitating concentration, support beyond sessions; parental avoidance and incentives; incentives for children; introducing resources; it’s the TRT activities that work.

Group leaders mentioned the importance of “rehearsing the sessions” and bringing “language we felt would be more comfortable and comprehensible to them.” Children struggled to close their eyes, concentrate and imagine for the need to watch others “so, we brought ribbons and blindfolded them … they just loved it.” Part of this was “creating a safe and quiet environment with shared purpose.” Group leaders also needed to give time to deal individually “because after finishing some sessions they would come and look for us.” Despite the “big efforts made” parental engagement was challenging. Providing “snacks helped” as some parents were concerned children would be hungry. Where other parents showed little care for children “a basket of food was provided for families.” That acted as an incentive, “with parents engaging in FFP for the first time.” Group leaders were worried this and other resources introduced could be counter-productive and become the main focus of the sessions. “Actually, the activities were the axis and that these things (food, etc.) we used to be just for them to come and stay.”

The Centrality of Context

A separate but significant theme under use of materials was that of the centrality of context. Much of group leaders’ contributions focused on this issue. The seven identified codes were: context analysis; addressing embeddedness and conflict of drug gangs; highlight coping skills; child loneliness and over-independence; intrusion of armed conflict; normalizing reactions not violence; addressing gender beliefs and behavior; and the influence of drug gangs.

Group leaders emphasized the need to “do an analysis of the territory, to know the specifics of each place.” This was not only to attune delivery to children’s needs but to ensure TRT fits into and doesn’t duplicate “service networks and educational and cultural activities.” Group leaders raised the constant possibility of children being enticed by the gangs and drug trafficking. “It is a constant fear that is always present in people’s lives … grooming though friendship.” TRT was seen as “a collective space to discuss identity, fears, aspirations, and power” and ask important questions such as “what causes a young person to enter or not to enter the trafficking life?” These are seen as complex problems, for example, “one of the children has several friends who have died, others who are still in trafficking … so he does not want to distance himself.” Another was “desperate in fear for something happening to his mother and he just wanted to lie in bed crying … we have to be able to discuss these issues with them.”

In relation to children themselves, they needed to understand that TRT was not part of their “ordinary experiences” of FFP. Child loneliness, youth over-independence with parents working two-to three jobs, willingness to address the armed conflict which on the one hand “will always come up” and on the other TRT “stimulated imagination as children are not used to talking about it.” Normalizing a range of emotions in TRT including “fear” and “listening to what your body is saying.” Awareness of gender issues was also raised with boys who believe the response to conflict, atrocities, and anger is “what we have to do is to get a gun” that “man has to be strong … or at least look like a fortress” And it’s not ok for boys to “feel fear … they think this is the only way to escape, to fight.” Girls in contrast, did not present such aggression and were therefore more responsive to the activities.

Discussion

The current study found TRT to be an effective intervention for children and young adolescents with PTSD who experienced drug and gang violence in a Brazilian Favela. Given the cumulative and ongoing of violence in these children’s lives, this is a significant finding for the efficacy of TRT within a context of ongoing conflict and crisis involving military, drug, gang, and domestic violence (Larkins 2015). A secondary gain of TRT was a significant reduction in children’s Depression. As TRT does not specifically address depression, it is likely that as children and adolescents experienced less PTSD symptoms, that is, they experienced less triggered intrusions, hyperarousal and avoidance, depression also decreased (Barron et al. 2013). Although, an exploratory measure of posttraumatic growth was used only 2 weeks following TRT, indications are TRT may be a promising program for promoting, for example, new relationships, new possibilities and personal and spiritual growth for children. Similarly, other Trauma-focused CBT programs have been found to increase posttraumatic growth for children who experienced cumulative trauma, including abuse in other parts of the world, e.g. Iran (Farnia et al. 2018). To know the impact of TRT on posttraumatic growth, future studies will need to include longitudinal follow-up with a measure designed specifically for children (Table 2).

Group leaders self-reported fidelity ratings suggested that despite the challenges within a favela, the protocols of TRT were mostly held to. Incidents did, however, occur and intruded into TRT sessions necessitating protocol adaptation. For example, group leaders had to adapt to an immediate violent crisis where children needed to share their experience. Group leaders indicated, most adaptations were limited and occurred through developing resources to motivate children to engage in activities at start-up, to maintain focus on task, and to achieve program completion. Despite limited parental support, the over-independence of children and unfamiliarity of the intervention, TRT did not need to be scaffolded by motivational approaches that can be used embedded CBT (Cornelius et al. 2011).

Parental engagement appears to have been a significant challenge in the Favelas and reflected the lack of engagement in children’s lives (Piccinini et al. 2013). To address this challenge, group leaders in the current study adopted a creative approach of providing food baskets for families, addressing a family need which appeared to facilitate a degree of parental support (Larkins 2015). However, despite the limited engagement of parents, children still made significant gains. TRT then, may be a program that would benefit from parental engagement but parental engagement does not appear to be a requirement for success.

While group leaders were keen to highlight the chaotic and dangerous context of the Favelas, they also viewed TRT as a means to create a safe space in an unsafe setting and provide new experiences missing from many children’s lives, such as affection, care, an opportunity to share, be listened to and validated (Barron et al. 2016). Group leaders viewed TRT as a program that enabled sensitive topics and taboos to be spoken about (e.g. male vulnerability), to be reframed, and for children to create their own unique solutions. Although not an aim of TRT, the program appears, to create a group environment that enabled a broad range of challenging topics to be raised and discussed beyond coping with traumatic experiences. This may be due to the emotionally safe context created and the experiences of healing that occurring. Group leaders also learned from children, how imaging a safe place in a collective setting, not only teaches a new resource but also turns the group itself into a safe place. The process underlying this program benefit requires focused research. Group leaders’ perceptions of children’s learning was also supported by the gains in symptom reduction. In addition, group leaders identified other benefits of TRT including relationship building, personal growth. Finally, the group leaders referred to their own knowledge and skill development in the preparation and delivery of a trauma specific program. Trusting in the procedures, knowing when to adapt. and the need to support each other were highlighted. This builds on prior TRT studies where group leaders reported that they learned how to deal with the uncertainty of adolescents’ responses by ensuring youth activities were fun and engaging. Further, there was a need to support adults to understand the impact of trauma (Barron et al. 2017).

Limitations

The current study utilized a small sample size, limiting the application of findings to other child and adolescents’ groups not included within the sample. In addition, two groups of sixteen and fourteen youth raises questions regarding the validity of the extensive statistical analysis on such a small population. A qualitative approach might have been more justified as a first step in a new context. In contrast, other studies of TRT have also used small sample sizes and similar statistical analyses to provide both quantitative and qualitative evidence to inform the the promising efficacy of TRT for different youth populations (Barron et al. 2017). The sample of group leaders was also small providing a specific view on program delivery. The small number of standardized measures provided a narrow perspective on what may be a wide range of mental health symptomology. As the age range covered 8–14 years, there is still a need to discover how younger and older adolescents will respond. Program fidelity was by self-report rather than an objective measure such as video record and the lack of cut-off score with the experimental posttraumatic growth measure meant that the extent of clinically significant growth could not be identified.

Conclusions

TRT was found to be an effective intervention for children and young adolescents with PTSD who experienced drug and gang violence in a Brazilian favela. A secondary gain of the program for children was a significant reduction in depression. Although only assessed 2 weeks following program delivery, there were promising indications of positive posttraumatic growth. Group leaders highlighted that despite the challenges of a chaotic and dangerous environment TRT, provided a safe space for learning coping skills, healing and the discussion of sensitive topics.

Recommendations for Practice

TRT is tentatively recommended for children and young adolescents presenting with clinical levels of PTSD in the Brazilian favelas. An analysis of the context, both situational factors and resources as well as the identification of the psychological and social needs of children, may be of considerable importance for program efficacy. Not all children’s score were below clinically significant levels and therefore, there is a need to recognize some children will need individualized trauma specific intervention beyond group based TRT, e.g. trauma-focused CBT (WHO 2013). Sufficient preparation is needed to ensure children understand that TRT is a coping skills program, not a therapy.

Recommendations for Future Research

Larger scale RCTs of TRT are needed in the Brazilian context. There is a need to increase the target population to children younger than 8 years and adolescents older than 14 years. A wider range of standardized measures is needed to explore efficacy with co-morbid conditions, and a child measure of PTG with a cut-off score will enable an assessment of the nature and extent of clinically significant gains. A more robust measure of program fidelity would include expert analysis of video-ed sessions. Sufficient numbers of children as well as group leaders need to be interviewed to gain a breadth and depth of program experience. A longitudinal evaluation design would enable as assessment of whether gains are maintained over time and whether there are further gains in PTG.

Acknowledgements

This study was made possible by the commitment of the workers, volunteers and children and families at Luta Lela Paz / Fight for Peace, Complexo da Mare, Rio De Janeiro, Brazil.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ali NS, Al-Joudi TW, Snell T. Teaching recovery techniques to adolescents exposed to multiple trauma following war and ongoing violence in Baghdad. The Editorial Assistants–Jordan. 2019;30(1):25–33. doi: 10.12816/0052933. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Andreoli SB, Ribeiro WS, Quintana MI, Guindalini C, Breen G, Blay SL, Coutinho ESF, Harpham T, Jorge MR, Lara DR, Moriyama TS, Quarantini LC, Gadelha A, Vilete LMP, Yeh MSL, Prince M, Figueira I, Bressan RA, Mello MF, Dewey ME, Ferri CP, de Jesus Mari J. Violence and post-traumatic stress disorder in Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil: The protocol for an epidemiological and genetic survey. BMC Psychiatry. 2009;9:34. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asbahr FR, Castillo AR, Ito LM, de Oliveira Latorre MRD, Moreira MN, Lotufo-Neto F. Group cognitive-behavioral therapy versus sertraline for the treatment of children and adolescents with obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2005;44(11):1128–1136. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000177324.40005.6f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa LP, Quevedo L, da Silva GDG, Jansen K, Pinheiro RT, Branco J, Lara D, Oses J, da Silva RA. Childhood trauma and suicide risk in a sample of young individuals aged 14–35 years in southern Brazil. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2014;38(7):1191–1196. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron IG, Abdallah G, Smith P. Randomized control trial of a CBT trauma recovery program in Palestinian schools. Journal of Loss and Trauma. 2013;18(4):306–321. doi: 10.1080/15325024.2012.688712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barron I, Abdallah G, Heltne U. Randomized control trial of teaching recovery techniques in rural occupied Palestine: Effect on adolescent dissociation. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma. 2016;25(9):955–973. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2016.1231149. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Barron I, Mitchell D, Yule W. Pilot study of a group-based psychosocial trauma recovery program in secure accommodation in Scotland. Journal of Family Violence. 2017;32(6):595–606. doi: 10.1007/s10896-017-9921-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology. 2006;3(2):77–101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cardia, N., Lagatta, P., & Affonso, C (n.d.) Assessment of child maltreatment prevention readiness country report Brazil. Available at https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/child/brazil_rap_cm.pdf?ua=1.

- Cornelius JR, Douaihy A, Bukstein OG, Daley DC, Wood SD, Kelly TM, Salloum IM. Evaluation of cognitive behavioral therapy/motivational enhancement therapy (CBT/MET) in a treatment trial of comorbid MDD/AUD adolescents. Addictive Behaviors. 2011;36(8):843–848. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa AB, Pasley A, de Lara Machado W, Alvarado E, Dutra-Thome L, Koller SH. The Experience of Sexual Stigma and the Increased Risk of Attempted Suicide in Young Brazilian People from Low Socioeconomic Group. Frontiers in Psychology. 2017;8:192. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curto BM, Paula CS, Do Nascimento R, Murray J, Bordin IA. Environmental factors associated with adolescent antisocial behavior in a poor urban community in Brazil. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology. 2011;46(12):1221–1231. doi: 10.1007/s00127-010-0291-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Assis SG, de Oliveira RDVC, de Oliveira Pires T, Avanci JQ, Pesce RP. Family, school and community violence and problem behavior in childhood: Results from a longitudinal study in Brazil. Paediatrics Today. 2013;9(1):36–48. doi: 10.5457/p2005-114.59. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- de Souza MAM, Salum GA, Jarros RB, Isolan L, Davis R, Knijnik D, Manfro GG, Heldt E. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for youths with anxiety disorders in the community: Effectiveness in low and middle income countries. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy. 2013;41(3):255–264. doi: 10.1017/S1352465813000015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Encyclopedia Britannica (2009). 8th edition. Encyclopedia Britannica. Chicago. 2009.

- Farias de Azambuja C, Cardoso de Azevedo T, Mondin TC, Souza de Mattos LD, da Silva RA, Kapczinski F, Magalhães da Silva PV, Jansen K. Clinical outcomes and childhood trauma in bipolar disorder: A community sample of young adults. Psychiatry Research. 2019;275:228–232. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2018.12.114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnia V, Naami A, Zargar Y, Davoodi I, Salemi S, Tatari F, Alikhani M. Comparison of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy and theory of mind: Improvement of posttraumatic growth and emotion regulation strategies. Journal of Education Health Promotion. 2018;7:58. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_140_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fatori, D., Polanczyk, G. V., de Morais, R. M. C. B., & Asbahr, F. R. (2019). Long-term outcome of children and adolescents with obsessive–compulsive disorder: A 7–9-year follow-up of a randomized clinical trial. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 10.1007/s00787-019-01457-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Faus DP, de Moraes CL, Reichenheim ME, Borges da Matta Souza LM, Taquette SR. Childhood abuse and community violence: Risk factors for youth violence. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2019;98:104182. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2019.104182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fleitlich B, Goodman R. Social factors associated with child mental health problems in Brazil: Cross sectional survey. BMJ [British Medical Journal] 2001;323(7313):599–600. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7313.599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grassi-Oliveira R, Stein LM. Childhood maltreatment associated with PTSD and emotional distress in low-income adults: The burden of neglect. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32(12):1089–1094. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2008.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habigzang LF, Damásio BF, Koller SH. Impact evaluation of a cognitive behavioral group therapy model in Brazilian sexually abused girls. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse. 2013;22(2):173–190. doi: 10.1080/10538712.2013.737445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habigzang LF, de Freitas CPP, Von Hohendorff J, Koller SH. Cognitive-behavioral group therapy for girl victims of sexual violence in Brazil: Are there differences in effectiveness when applied by different groups of psychologists? Anales de Psicología/Annals of Psychology. 2016;32(2):433–441. doi: 10.6018/analesps.32.2.213041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jaen-Varas D, de Jesus Mari J, da Silva Coutinho E, Baxter Andreoli S, Quintana MI, de Mello MF, Affonseca Bressan R, Silva Ribeiro W. A cross-sectional study to compare levels of psychiatric morbidity between young people and adults exposed to violence in a large urban center. BMC Psychiatry. 2016;16:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12888-016-0847-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larkins ER. The spectacular favela: Violence in modern Brazil. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- McDermott MAN, Palchanes K. A literature review of the critical elements in translation theory. Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1994;26(2):113–118. doi: 10.1111/j.1547-5069.1994.tb00928.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Piccinini, C. A., Alvarenga, P., & Marin, A. H. (2013). Child-rearing practices of Brazilian mothers and fathers: Predictors and impact on child development. In Parenting in South American and African Contexts. IntechOpen. Open access peer reviewed chapter. 10.5772/57242.

- Pupo MC, Serafim PM, de Mello MF. Health-related quality of life in posttraumatic stress disorder: 4 years follow-up study of individuals exposed to urban violence. Psychiatry Research. 2015;228(3):741–745. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2015.05.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro WS, Mari J d J, Quintana MI, Dewey ME, Evans-Lacko S, Vilete LMP, Figueira I, Bressan RA, de Mello MF, Prince M, Ferri CP, Coutinho ESF, Andreoli SB. The impact of epidemic violence on the prevalence of psychiatric disorders in Sao Paulo and Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. PLoS One. 2013;8(5):e63545. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0063545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro DS, Ribeiro FML, Deslandes SF. Discourses about mental health demands of young offenders serving detention measure in juvenile correctional centers in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil/Discursos sobre as demandas de saude mental de jovens cumprindo medida de internacao no Rio de Janeiro, Brasil. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva. 2019;10:3837–3846. doi: 10.1590/1413-812320182410.23182017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkadi A, Ådahl K, Stenvall E, Ssegonja R, Batti H, Gavra P, Fängström K, Salari R. Teaching recovery techniques: Evaluation of a group intervention for unaccompanied refugee minors with symptoms of PTSD in Sweden. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2018;27(4):467–479. doi: 10.1007/s00787-017-1093-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P, Perrin S, Dyregrov A, Yule W. Principal components analysis of the impact of event scale with children in war. Personality and Individual Differences. 2003;34(2):315–322. doi: 10.1016/S0191-8869(02)00047-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith P, Dyregrov A, Yule W. The teaching recovery techniques manual. The Children and War Foundation: Bergen; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Teche SP, Barros AJS, Rosa RG, Guimarães LP, Cordini KL, Goi JD, Hauck S, Freitas LH. Association between resilience and posttraumatic stress disorder among Brazilian victims of urban violence: A cross-sectional case-control study. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy. 2017;39(2):116–123. doi: 10.1590/2237-6089-2016-0070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tedeschi RG, Calhoun LG. The posttraumatic growth inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress. 1996;9(3):455–471. doi: 10.1007/bf02103658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thabrew H, Stasiak K, Bavin LM, Frampton C, Merry S. Validation of the mood and feelings questionnaire (MFQ) and short mood and feelings questionnaire (SMFQ) in New Zealand help-seeking adolescents. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 2018;27(3):e1610. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tucci AM, Kerr-Corrêa F, Souza-Formigoni MLO. Childhood trauma in substance use disorder and depression: An analysis by gender among a Brazilian clinical sample. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2010;34(2):95–104. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waldemar JOC, Rigatti R, Menezes CB, Guimarães G, Falceto O, Heldt E. Impact of a combined mindfulness and social–emotional learning program on fifth graders in a Brazilian public school setting. Psychology & Neuroscience. 2016;9(1):79–90. doi: 10.1037/pne0000044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- WHO (2013). World Health Organization, Geneva. https://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/releases/2013/trauma_mental_health_20130806/en/. Accessed 26 July 2020.