Abstract

In this study, some biological activities including antioxidant activity (DPPH radical scavenging activity, ABTS radical scavenging activity, and CUPRAC assay), DPP-IV enzyme inhibitory activity, and α-glucosidase enzyme inhibitory activity of peptides released from in vitro gastrointestinal digested casein and the whey proteins of camel and donkey milk were evaluated. While the highest antioxidant activity was determined to be in the digested camel casein fraction using the ABTS and CUPRAC methods, the digested donkey casein fraction was determined to have the highest radical scavenging activity using the DPPH method. The highest DPP-IV inhibitory activity was detected in digested camel and donkey milk casein fractions. Digested whey fractions of camel and donkey milk had a lower DPP-IV inhibitory activity compared to the digested casein fractions. However, digested whey fractions of camel and donkey milk did not show α-glucosidase inhibitory activity, and digested donkey casein fraction showed the highest α-glucosidase inhibitory activity with a 12.5 µg/mL IC50 value. It was concluded that peptides released from digested casein fraction of camel and donkey milk have potent antioxidant and particularly antidiabetic properties.

Keywords: Camel milk, Donkey milk, Bioactive peptides, DPP-IV inhibitory activity, Antioxidant activity, α-glucosidase inhibitory activity

Introduction

Type II diabetes is the one of the most serious metabolite syndromes affecting many people every year around the world. In 2017, 451 million people worldwide between the ages of 18 and 99 suffered from Type II diabetes, and by the year 2045, it is predicted that this number will rise to 693 million (Cho et al. 2018). Dipeptidyl peptidase-IV (DPP-IV) and α-glucosidase are enzymes inactivating incretins that regulate a normal blood glucose level (Demuth et al. 2005). Inhibition of DPP-IV and α-glucosidase enzymes is the one of the primary methods of controlling Type II diabetes. From in vivo studies, it has been discovered that food proteins have a role in regulating serum glucose levels (Lacroix and Li-Chan 2013). In these studies, animal and marine products and plants were used as food protein resources for the regulation of glucose levels (Méric et al. 2014). Bioactive peptides from several protein sources, particularly milk proteins, have many biological properties including antioxidant, antimicrobial, antidiabetic, antihypertensive, anticancer, and antitumor activities (Ayyash et al. 2018). The DPP-IV inhibitory activities of peptides from bovine milk and its products have been examined in many studies, but the number of studies in which the DPP-IV inhibitory activities of non-cow milk species are focused on is quite limited. Nongonierma et al. (2018) reported that nine new DPP-IV inhibitory peptides were identified in the trypsin hydrolysate of camel milk proteins. Kamal et al. (2018) stated that hydrolyzed camel milk whey protein showed high DPP-IV inhibitory activity. In the literature, while the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of plant origin products have been studied, there is little research on the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of milk and milk products, although Lacroix and Li-Chan (2013) studied the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of pepsin-treated bovine whey proteins, and Ayyash et al. (2018) tried to determine the α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of probiotic camel and bovine milk drinks.

Free radicals and reactive oxygen species promote the onset and progression of cancer and diabetes and degenerative diseases like Alzheimer’s and Parkinson’s (Aluko 2012). It is necessary to control oxidative stress in order to inhibit the development of degenerative diseases and to slow the growth rate of diseases (Barać et al. 2017). In literature, there are many studies on the antioxidant activity of camel milk protein, but research on the antioxidant activity of donkey milk protein derived peptides is still scarce. Rahimi et al. (2016) determined that the microbial proteinase K enzyme hydrolysate of camel milk casein had antioxidant activity (IC50 = 3.3 µg /mL) comparable to vitamin C and trolox.

The interest in functional foods has increased recently due to their nutritional value and health supporting properties as well as their potential to reduce the risk of various diseases (Aspri et al. 2018). Thus, more attention has been given to goat’s milk, camel milk, and donkey milk due to their various health-improving and therapeutic effects. The interest in these milks has increased because the composition of donkey milk is very similar to human milk and camel milk does not contain the beta-lactoglobulin fraction in whey protein that causes milk allergy.

Camel milk and donkey milk differ from bovine milk in terms of their protein content and structure. For example, camel milk does not contain β-lactoglobulin, and the level of αs-casein is higher compared to bovine milk. In the whey protein fraction, donkey milk contains less β-lactoglobulin and more α-lactalbumin and immunoglobulins than that of bovine milk (Uniacke-Lowe and Fox 2010). Donkey and camel milk production levels are very low compared to that of bovine milk worldwide. However, the use of donkey and camel milk is popular because of their properties of health improvement and support. Therefore, it is important to obtain bioactive peptides from these milk types in various ways including enzymatic hydrolysis, fermentation with lactic acid bacteria, and gastrointestinal digestion.

In the literature, the studies of donkey milk bioactive peptides are still scarce. Compared to donkey milk, some extensive studies have been conducted on camel milk peptides. In these studies, the ACE (Angiontensin converting enzyme) inhibitory and antioxidant activities of camel milk enzymatic hydrolysates were investigated (Salami et al. 2011; Jrad et al. 2014a; Rahimi et al. 2016). Although many review studies reported that camel and donkey milk have important effects on Type II diabetes, the number of studies on the antidiabetic properties of the peptides of camel and donkey milk is very limited. In the literature, no study has been found with antidiabetic peptides originating from donkey milk proteins. For this reason, in this study, the attempt was made to provide preliminary information for future studies by evaluating the antioxidant activity and, in particular, the antidiabetic activity of the peptides derived from in vitro gastrointestinal digested casein and whey fractions of camel and donkey milk.

Materials and methods

Chemicals

Porcine pepsin, pancreatin, bile extract porcine, bicinchoninic acid (BCA) reagent, o-phthalaldehyde (OPA) reagent, L-serine, bovine serum albumin, 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH), neocuproine, L-ascorbic acid, 2,2-azino-di-(3-ethylbenzothialozine-sulphonic acid)-diammonium salt (ABTS), (±)-6-hydroxy-2,5,7,8-tetramethylchromane-2-carboxylic acid (Trolox), Gly-Pro-P-nitroanilide, α-Glucosidase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae, p-nitrophenyl α-D-glucopyranoside, p-nitrophenol were provided by Sigma Aldrich (St. Louis, USA).

Camel and donkey milk

Camel milk and donkey milk were provided by Kaya Kardeşler Camel Milk production in Aydın, Turkey and Ege Donkey Milk production in Balıkesir, Turkey, respectively. The milk samples were stored at 4 °C during transportation to the laboratory.

Preparation of whey and casein fractions from milk samples

Firstly, the milk fat layer of the milk samples was removed by centrifugation at 3000×g at 4 °C for 30 min, then the seperation of casein and whey proteins was performed. The casein and whey fraction of the camel and donkey milk were separated by adjusting pH at 4.6 using 6 N HCl and centrifuged (Sigma 3–16 K, Osterode am Harz, Germany) at 3000×g for 30 min at 20 °C. The supernatant (whey) and pellet (casein) were stored at 4 °C until the in vitro digestion process.

In vitro gastrointestinal digestion (GIS) of whey and casein fractions of camel and donkey milk

Whey and casein fractions of camel and donkey milk were digested using a static simulated gastrointestinal digestion protocol according to Minekus et al. (2014). Porcine pepsin and pancreatin enzymes were used during the digestion process. Amylase enzyme was not used in the digestion process because of the aim of acquiring peptides.

Determination of degree of hydrolysis (DH)

The degree of hydrolysis of digested whey and casein fractions of camel and donkey milk was analyzed using the OPA method (Church et al. 1983). The absorbance was measured at 340 nm using the 96-well Microplate Reader. A standard curve was plotted using the serine standard. The degree of hydrolysis was determined by using the following equation:

| 1 |

h: free amino group of digested samples-free amino group of undigested samples.

htot: total number of peptide bonds per protein equivalent. htot value is 8.2 and 8.8 mEq/g protein for casein and whey protein, respectively.

Peptide concentration of digested whey and casein fractions of camel and donkey milk

Peptide contents of digested whey and casein fractions of camel and donkey milk was determined by the BCA method according to Smith et al. (1985). The absorbance was measured at 562 nm using the 96-well Microplate Reader, and bovine serum albumin was used as a standard.

Determination of total antioxidant activity with DPPH, ABTS, and CUPRAC methods

The DPPH (2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl) radical scavenging activity was determined by the method described by Pavithra and Vadivukkarasi (2015) with some modifications. A DPPH radical solution (0.2 mM) was prepared in methanol. A volume of 100 µL DPPH solution was added to 100 µL of the sample and incubated at room temperature for 30 min in the dark. The absorbance was measured at 517 nm using a 96-well Microplate Reader (Thermo Scientific, Multiskan Sky, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). For the control sample, 100 µL methanol was used instead of 100 µL for the sample. Blank solutions were used for both control and sample. The results were expressed as a percentage of DPPH radical scavenging activity (RSA). The IC50 value was defined as the concentration of an inhibitor required to inhibit 50% of the DPPH radical.

| 2 |

The CUPRAC (cupric ion reducing antioxidant capacity) assay was determined by the method described by Apak et al. (2004). A volume of 25 μL 10 mM CuCl2 × H2O, 25 μL of 7.5 mM neocuproine (solved in ethanol), and 25 μL of 1.0 M ammonium acetate buffer (pH 7.0) were mixed in a 96-well microplate and incubated at 37 °C for 30 min. Absorbances were measured at 450 nm using a 96-well Microplate Reader (Thermo Scientific, Multiskan Sky, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), and the results were expressed as a µmol/mL ascorbic acid equivalent.

The ABTS [(2,2-azino-di-(3-ethylbenzothialozine- sulfonic acid)] radical scavenging activity was determined by the method described in Re et al. (1999). Ten µL of the sample and 240 µL of the ABTS solution was mixed and incubated for 10 min. at room temperature. Then, absorbances were measured at 734 nm using a 96-well Microplate Reader (Thermo Scientific, Multiskan Sky, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA). The results were expressed as µg/µL Trolox equivalent antioxidant capacity (TEAC) and percentage of ABTS inhibition.

DPP-IV inhibitory activity

The effect of the digested casein and whey protein extracts on DPP-IV inhibitor activity was determined using a DPP-IV assay described by Zeytünlüoğlu and Zihnioğlu (2015). In a 96-well microplate, a 10 μL DPP-IV enzyme solution and an x μL sample were preincubated at 37 °C for 15 min; after which a 90-x μL buffer (100 mM Tris–HCl, pH 8.0) and a 100 μL H-Gly-Pro-Pna substrate (2 mM) were added, and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. For the control group, a 10 μL DPP-IV enzyme solution and a 90 μL sample were preincubated at 37 °C for 15 min, and then a 100 μL H-Gly-Pro-Pna substrate (2 mM) were added, and the mixture was incubated at 37 °C for 15 min. After the incubation period, the absorbance of the released p-nitroanilide was measured at 405 nm using a 96-well Microplate Reader (Thermo Scientific, Multiskan Sky, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), and p-nitroaniline was used as a standard. H-Gly-Pro-Pna substrate was not added to the sample and control group blanks. The IC50 value was defined as the concentration of an inhibitor required to inhibit 50% of the DPP-IV activity under the assay conditions.

DPP-IV inhibitor activity was calculated by the following formula:

| 3 |

α-glucosidase inhibitory activity

The effect of the digested casein and whey protein extracts on α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was determined by Zhang et al. (2014). A 50 mM sodium phosphate with pH:6,8 used as a buffer, α-glucosidase from Saccharomyces cerevisiae used as an enzyme (prepared as 0.1 U/mL solution and diluted five times), and 2 mM p-Nitrophenyl α-D-glucopyranoside used as a substrate. The sample solutions (50 μL) were preincubated with 50 μL of the α-glucosidase enzyme at 37 °C for 10 min. Then, the 75 μL buffer solution and the 75 μL substrate were added to the mixture and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. The absorbances were measured at 405 nm using a 96-well Microplate Reader (Thermo Scientific, Multiskan Sky, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA), and p-nitrophenol (pnF) (10–100 nmol) was used as a standard. For the control group, 125 μL of the buffer solution was preincubated with 50 μL of the enzyme solution. Then, only the 75 μL substrate solution was added to the mixture and incubated at 37 °C for 10 min. For the blank solution of the control group and sample, the substrate solution was not added to the mixture. The IC50 value was defined as the concentration of an inhibitor required to inhibit 50% of the α-glucosidase activity under the assay conditions.

α-glucosidase inhibitor activity was calculated as the following formula:

| 4 |

RP-HPLC profile of peptides

The in vitro digested casein and whey proteins of the camel and donkey milk were freeze-dried and analyzed by reverse-phase high performance liquid chromatography (RP-HPLC) as described by Hayaloglu et al (2013) using a Shimadzu LC20 AD Prominence HPLC system (Shimadzu Corporation, Kyoto, Japan). A Supelco C18 column 250 × 4.6 mm × 5 μm, 300 Å pore size (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, USA) was used. The solvents were as follows: (A) 0.1% (v/v) trifloroacetic acid (TFA, Sigma, St Louis, USA) in deionized HPLC-grade water (Milli-Q system, Waters Corp., Molshem, France) and (B) 0.1% (v/v) TFA in 100% acetonitrile (Fluka ≥ 99.5, Sigma-Aldrich Chemie, CH-9471 Buchs, USA) at a flow rate of 0.75 mL/min. A 10 mg of freeze-dried sample was dissolved in solvent A (10 mg/mL), filtered through a 0.45 μm cellulose acetate filter (Sterlitech Corp. WA, USA), and an aliquot (60 μL) of filtrate was injected into the column. The samples were eluted initially with 100% A for 10 min, then with a gradient from 0 to 50% B and 50 to 60% B over 90 min and 5 min, respectively. It was maintained at 60% B for 5 min, followed by a linear gradient from 60 to 95% B over 5 min and maintained at 95% B for 5 min. The elute was monitored at 214 nm.

Data analysis

In the research, 2 experimental replicates were carried out. All analysis were performed by 3 technical replicates. For the statistical evaluation of analysis results, a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) in the SPSS version 22.0 (SPSS Inc. Chicago, Illinois) using the DUNCAN test was used. Correlation coefficent was calculated using Pearson Correlation Test. P < 0.05 was considered a statistically significant difference.

Results and discussion

Peptide concentration and degree of hydrolysis (DH)

The peptide concentration and degree of hydrolysis values of samples are shown in Table 1. The maximum peptide concentration value was determined in the DC sample (4.94 mg/mL) whereas the minimum peptide concentration value was determined in the CC sample (3.37 mg/mL). During the in vitro GIS, the degree of hydrolysis values ranged from 50.25 to 75.68% (Table 1). The hydrolysis degree of digested whey protein extracts of camel and donkey milk were higher ca. 25% than the digested casein extracts of camel and donkey milk.

Table 1.

Peptide concentration and degree of hydrolysis values of samples

| Sample | Peptide concentration (mg/mL) | Degree of hydrolysis (%) |

|---|---|---|

| CW | 4.26 ± 0.17b | 75.68 ± 2.70a |

| CC | 3.37 ± 0.07c | 53.06 ± 3.98b |

| DW | 3.90 ± 0.45b | 73.41 ± 4.74a |

| DC | 4.94 ± 0.06a | 50.25 ± 1.04b |

Data are expressed as means ± standard deviation. Means followed by different letters in the columns are significantly different (P < 0.05)

CC, Digested camel milk casein; CW, Digested camel milk whey; DC, Digested donkey milk casein; DW, Digested donkey milk whey

Boirie et al. (1997) showed that the digestion and absorption of amino acid rate of whey protein is more than 37% compared to casein Jrad et al. (2014b) reported that the hydrolysis level of casein was 19% in camel milk casein by pepsin and pancreatin hydrolysates. Kamal et al. (2018) reported that camel milk whey proteins reached the highest hydrolysis level after 6 h of hydrolysis with chymotrypsin enzyme (47.5%). Al-Shamsi et al. (2018) pointed out that with the hydrolysis of camel milk with alcalase, bromelain and papain enzymes, the highest hydrolysis degree (39.6%) was determined as a result of a 6-h papain hydrolysis. In this study, the hydrolysis degree of both camel and donkey whey proteins and casein were higher than those of the studies by Jrad et al. (2014b), Kamal et al. (2018), and Al-Shamsi et al. (2018). In the present study, it can be said that the in vitro gastrointestinal digestion and the GIS environment contributed to the hydrolysis degree based on hydrolysis degree of this research compared to other research results.

Total antioxidant activity for the DPPH, ABTS, and CUPRAC method

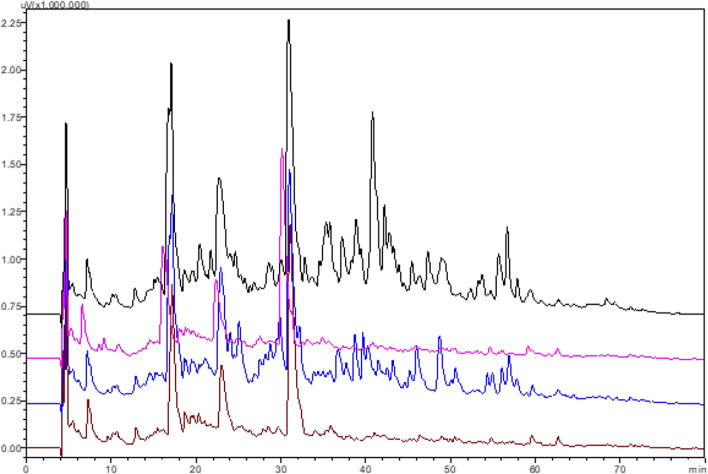

In the present study, DPPH, ABTS and CUPRAC assays were evaluated for the determination of the antioxidant activity of samples. Regarding the DPPH assay, the DC sample showed the highest DPPH radical scavenging activity (IC50 = 262.84 µg/mL, data not shown) compared to the other samples.

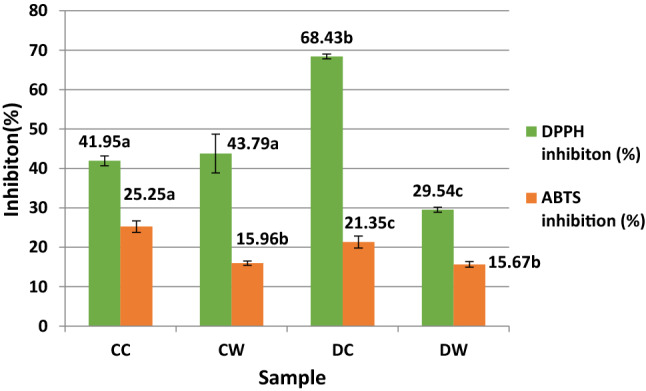

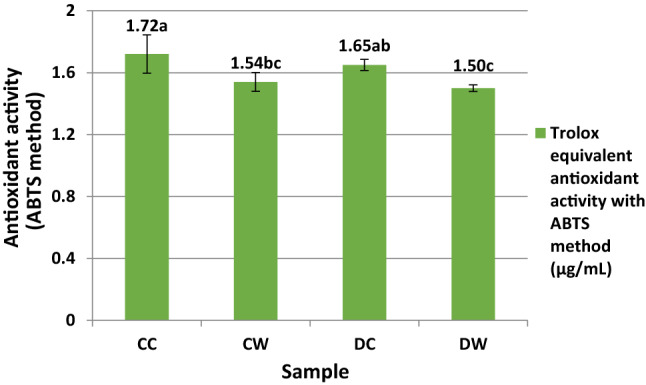

There was no significant difference in DPPH radical scavenging activity between the CC and CW samples (P > 0.05) (Fig. 1). For the ABTS and CUPRAC assays, the CC sample showed the highest antioxidant activity and followed by DC sample (Figs. 2 and 3). For the ABTS and DPPH methods, the DW sample, and for the CUPRAC method, CW sample had the minimum antioxidant activity between the samples. For ABTS method, statistically significant differences were observed between the casein and whey fractions of the camel and donkey milk (P < 0.05). For the CUPRAC method, the antioxidant activity of CC sample showed a statistically difference compared to the other samples (P < 0.05).

Fig. 1.

DPPH inhibition and ABTS inhibition percentages of the samples. CC: Digested camel milk casein, CW: Digested camel milk whey, DC: Digested donkey milk casein, DW: Digested donkey milk whey. Different letters a–c on bars represent significant differences among samples

Fig. 2.

Trolox equilavent antioxidant activity (TEAC) values of the samples with ABTS method (µg/µL). CC: Digested camel milk casein, CW: Digested camel milk whey, DC: Digested donkey milk casein, DW: Digested donkey milk whey. Different letters a–c on bars represent significant differences among samples

Fig. 3.

Ascorbic acid (mM) equilavent antioxidant activity of the samples with CUPRAC method. CC: Digested camel milk casein, CW: Digested camel milk whey, DC: Digested donkey milk casein, DW: Digested donkey milk whey. Different letters a and b on bars represent significant differences among samples

In the present study, for the ABTS and CUPRAC assays, the casein fractions have more antioxidant activity than the whey fractions. In the antioxidative peptides, the hydrophobic and aromatic amino acids found in the peptide structure (Salami et al. 2011) and the hydrophobic amino acid residues at the C terminal in the peptide sequence are important. Jrad et al. (2014b) reported that pepsin and pancreatin hydrolysates of camel milk casein released higher levels of antioxidative peptides than whey proteins. Similar to our results, the CC and DC samples had higher antioxidant activity compared to the CW and DW samples in the ABTS and CUPRAC assays. In addition, in the DPPH assay, when the DW and DC samples were compared, the DC sample had the highest antioxidant activity (IC50: 262 µg/mL) while the DW sample had the lowest antioxidant activity (IC50: 570 µg/mL).

It is known that casein-derived peptides contain more hydrophobic amino acid residues than whey, and whey derived peptides have an EPIC character (Ibrahim et al. 2018). Homayouni-Tabrizi et al. (2016) identified 2 new antioxidative peptides derived from camel milk αs1-casein containing a higher number of residues of Pro, Val, and Met. The main casein fraction in both camel and donkey milk is β-casein which is more susceptible to enzymatic hydrolysis than other casein fractions (Bastian and Brown 1996). It should be pointed out that more antioxidant peptides from β-casein are released in CC and DC samples in this study. It can be said that, since the CC sample could have more hydrophobic peptides than the DC sample, it showed higher antioxidant activity in the ABTS and CUPRAC assays. However, for the DPPH assay the highest antioxidant activity was determined in the DC sample.

In this study, antioxidant activity assay results showed differences because of their method mechanism; in the DPPH method, only the antioxidant activity of hydrophilic peptides can be measured, and in the ABTS and CUPRAC methods, the antioxidant activity of both the hydrophilic and hydrophobic peptides can be measured. A positive high correlation was found between the peptide concentrations of samples and DPPH radical scavenging activity (r = 0.82). In the present study, when antioxidant activity methods were compared with each other, a positive high correlation (r = 0.82) was found between the ABTS and CUPRAC methods. Therefore, in this study, it was concluded that the use of the ABTS and CUPRAC methods was more appropriate for determining the antioxidant activities of the samples.

DPP-IV inhibitory activity

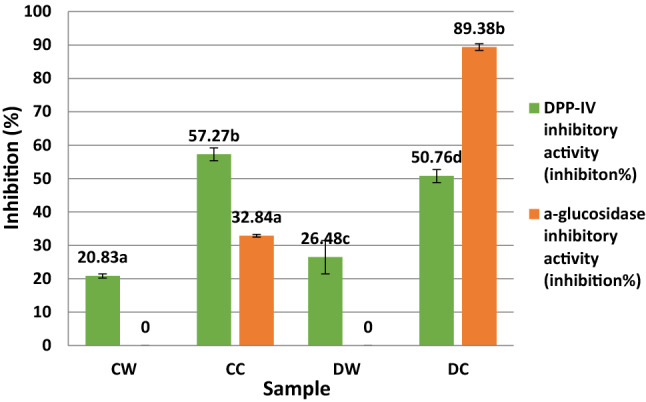

The DPP-IV inhibitory activity values of the digested samples are shown in Fig. 4. The DPP-IV inhibitory activity of samples ranged from 20.83 to 57.27%. The DC sample had the maximum DPP-IV inhibitory activity with an IC50 value of 113.45 µg/mL whereas the CW sample had a minimum DPP-IV inhibitory activity with an IC50 value of 432.69 µg/mL (data not shown). The DPP-IV enzyme inhibitory activities showed a statistically significant difference between samples (P < 0.05). The DPP-IV inhibitory activity of the CC and DC samples was two times higher than the CW and DW samples. In the present study, the casein derived peptides showed more DPP-IV inhibitory activity compared to the whey protein derived peptides. Lacroix and Li-Chan (2013) stated that the peptic hydrolysate of α-lactalbumin, whey protein isolate, and β-lactoglobulin showed 91, 82, and 28% inhibitory activity, respectively. In the present study, contrary to Lacroix and Li-Chan (2013), camel milk whey protein rich in α-lactalbumin showed minimum DPP-IV inhibitory activity between the sample groups. The correlation of the lower DPP-IV inhibitory activity of the CW sample to the DW sample could be because camel milk whey does not include β-lactoglobulin whereas donkey milk whey includes both β-lactoglobulin and α-lactalbumin. Nongonierma et al. (2019) reported that, while a large number of DPP-IV inhibitory peptides from camel milk casein were released, a limited number of peptides from whey protein were released. In the present study, in parallel to Nongonierma et al. (2019), the DPP-IV inhibitory activity of both camel and donkey casein hydrolysates was found to be significantly higher than whey protein hydrolysates (P < 0.05).

Fig. 4.

DPP-IV inhibitory and α-glucosidase inhibitory activity of the samples. CC: Digested camel milk casein, CW: Digested camel milk whey, DC: Digested donkey milk casein DW: Digested donkey milk whey. Different letters a–d on bars represent significant differences among samples

Song et al. (2017) stated that the protease type and hydrolysis conditions are very important for the releasing of DPP-IV inhibitory peptides as well as large number of hydrophobic amino acids in the peptide sequence. The presence of hydrophobic amino acid and proline residue, especially a proline in the second N-terminal residue within the sequence of peptides, is a typical characteristic of DPP-IV inhibitory peptides (Li-Chan et al. 2012) as well as of antioxidative peptides. The proline residue is present within the sequences of bovine whey protein derived DPP-IV inhibitory peptides as the second or third N-terminal residue (Lacroix and Li-Chan 2013). In the present study, interestingly, a positive correlation between the antioxidant activity results determined with the ABTS method and DPP-IV inhibitory activity is quite high (r = 0.97). Based on this correlation coefficient, it can be said that antioxidative peptides and DPP-IV inhibitory peptides have similar amino acid residue in their peptide structure.

α-Glucosidase inhibitory activity

In the present study, samples were evaluated regarding α-glucosidase (microbial baker’s yeast) inhibitory activity (Fig. 4). α-glucosidase inhibitory activity was not determined in the CW and DW samples, but α-glucosidase inhibitory activity values were calculated as 32.84 and 89.38%, respectively (Fig. 4). The DC sample had the maximum level of inhibitory activity with an α-glucosidase IC50 of 12.52 µg/mL. The αs-casein content of donkey milk is higher than that of camel milk; thus, it can be said that, during the in vitro GIS for the DC sample, more peptides with an α-glucosidase inhibitor potent were released and showed a remarkably high level of α-glucosidase inhibitor activity.

Lacroix and Li-Chan (2013) reported that with the whey protein peptic hydrolysates, only β-lactoglobulin and α-lactalbumin hydrolysates displayed inhibitory activity against α-glucosidase (rat intestinal enzyme). Kamal et al. (2018) stated that a 3-h hydrolysis of whey proteins with pepsin and chymotrypsin showed the highest a-glucosidase inhibitory activity (78%). Contrary to these studies, in this research, there was no α-glucosidase inhibitory activity in the CW and DW samples. Possible reasons for this difference are the use of the α-glucosidase assay method, the origin of α-glucosidase enzyme, the enzymatic hydrolysis method, and the materials. However, the exact mechanism by which peptides could inhibit α-glucosidase activity is unknown, and peptides can show inhibitory activity with hydrophobic interactions by binding the active site of the enzyme (Bharatham et al. 2008).

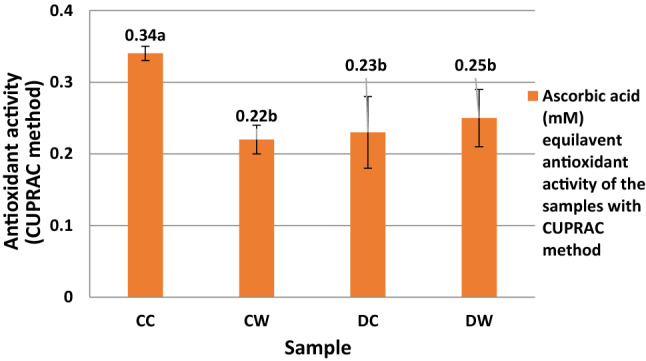

RP-HPLC profile of digested samples

Although the hydrolysis level of the casein of camel and donkey milk is lower than that of whey proteins, it is seen in RP-HPLC chromatograms (Fig. 5) where a large number of casein-derived peptides are released. However, the peptide profiles of the CC and DC samples are similar, and the concentrations of the CC peptides from the retention time of 30 min are quite high compared to the DC sample.

Fig. 5.

RP-HPLC profiles of digested camel and donkey milk casein and whey peptides (the black color profile belongs to the CC sample, the pink color profile belong to the CW sample, the blue color profile belongs to the DC sample, and the brown color profile belong to the DW sample). CC: Digested camel milk casein, CW: Digested camel milk whey, DC: Digested donkey milk casein, DW: Digested donkey milk whey (color figure online)

When RP-HPLC peptide profiles of the CW and DW samples were compared, it was seen that peptide profiles are very similar; only the height of some peaks show a difference. The most obvious difference between camel milk and donkey milk in terms of whey proteins is that camel milk does not contain beta lactoglobulin. When the peptide profiles of digested whey proteins were examined, different peptides were not seen at different retention times. Based on this, we can say that beta lactoglobulin in donkey milk is completely broken down into peptides, and there is no difference in the RP-HPLC profile. The major difference between digested whey and casein is that the peptide concentrations of digested whey proteins are very low from the 30th minute of retention time.

It can be said that the CW and DW samples showed lower DPP-IV inhibitory activity and did not show α-glucosidase inhibitory activity because the peptides contained low hydrophobic amino acid residue. Bidasolo et al. (2012) identified 46 peptides from donkey milk hydrolysates, 30 of which were of β-casein origin. Aspri et al. (2018) identified the digested donkey milk peptides, and they found that most of the peptides were β-casein derived. In accordance with Bidasolo et al. (2012) and Aspri et al. (2018), in the present study, due to the high content of β-casein in donkey and camel milk, most of the peptides may be derived from β-casein.

In the study by Aspri et al. (2018), among the whey proteins, most of the peptides were derived from β-lactoglobulin 1 and 2 because donkey milk β-lactoglobulin is very sensitive to enzymatic hydrolysis (Tidona et al. 2014). Quirós et al. (2005) showed that α-lactalbumin and lysozyme are resistant to GIS due to their tertiary structure and stated that in vitro gastrointestinal digested peptide profiles have a more homogeneous composition because of the great hydrolysis effect of digestive enzymes. The main differences in the peptide profiles of the samples exposed to the in vitro GIS resulted from the presence of 1 or 2 additional amino acids, possibly due to different movements of the amino and carboxy peptidases at the amino or carboxyl terminal end of the peptide during digestion (Aspri et al. 2018).

Conclusion

In this research, casein and whey fractions of camel and donkey milk were digested using a standardized static in vitro GIS method for mimicking human gastrointestinal digestion. Although the donkey milk protein content was lower than that of the camel milk, more peptides were released from the donkey casein after in vitro digestion compared to the camel casein. The most remarkable result of this research is that both donkey and camel milk casein-derived peptides showed better antidiabetic and antioxidant activity compared to whey-derived peptides. The DC sample had the best α-glucosidase inhibitory activity (IC50: 12.52 µg/mL) and antioxidant activity with the DPPH method while the CC peptides showed the best DPP-IV inhibitor activity and antioxidant activity with the ABTS and CUPRAC methods. The CW and DW samples did not show α-glucosidase inhibitory activity. It can be concluded that camel and donkey milk peptides derived from casein fractions could be good candidates for controlling Type II diabetes, more in vitro and in vivo research on bioactive peptides, particularly antidiabetic peptides, from camel and donkey milk proteins is needed.

Acknowledgements

This research was not supported by any funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Compliance with ethical standards

Conflict of interest

The author declare no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Change history

3/25/2021

A Correction to this paper has been published: 10.1007/s13197-021-05076-7

References

- Al-Shamsi KA, Mudgil P, Hassan HM, Maqsood S. Camel milk protein hydrolysates with improved technofunctional properties and enhanced antioxidant potential in in vitro and in food model systems. J Dairy Sci. 2018;101(1):47–60. doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-13194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aluko RE. Functional foods and nutraceuticals. New York: Springer; 2012. pp. 37–61. [Google Scholar]

- Apak R, Güçlü K, Özyürek M, Karademir SE. Novel total antioxidant capacity index for dietary polyphenols and vitamins C and E, using their cupric ion reducing capability in the presence of neocuproine: CUPRAC method. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 2004;52(26):7970–7981. doi: 10.1021/jf048741x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aspri M, Leni G, Galaverna G, Papademas P. Bioactive properties of fermented donkey milk, before and after in vitro simulated gastrointestinal digestion. Food Chem. 2018;268:476–484. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.06.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayyash M, Al-Dhaheri AS, Al Mahadin S, Kizhakkayil J, Abushelaibi A. In vitro investigation of anticancer, antihypertensive, antidiabetic, and antioxidant activities of camel milk fermented with camel milk probiotic: a comparative study with fermented bovine milk. J Dairy Sci. 2018;101(2):900–911. doi: 10.3168/jds.2017-13400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barać M, Pešić M, Vučić T, Vasić M, Smiljanić M. Bijeli sirevi u salamuri kao potencijalni izvor bioaktivnih peptida. Mljekarstvo. 2017;67(1):3–16. doi: 10.15567/mljekarstvo.2017.0101. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bastian ED, Brown RJ. Plasmin in milk and dairy products: an update. Int Dairy J. 1996;6(5):435–457. doi: 10.1016/0958-6946(95)00021-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bharatham K, Bharatham N, Park KH, Lee KW. Binding mode analyses and pharmacophore model development for sulfonamide chalcone derivatives, a new class of α-glucosidase inhibitors. J Mol Graph Model. 2008;26(8):1202–1212. doi: 10.1016/j.jmgm.2007.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bidasolo IB, Ramos M, Gomez-Ruiz JA. In vitro simulated gastrointestinal digestion of donkeys’ milk: peptide characterization by high performance liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Int Dairy J. 2012;24(2):146–152. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2011.04.014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Boirie Y, Dangin M, Gachon P, Vasson MP, Maubois JL, Beaufrère B. Slow and fast dietary proteins differently modulate postprandial protein accretion. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94(26):14930–14935. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho NH, Shaw JE, Karuranga S, Huang Y, da Rocha Fernandes JD, Ohlrogge AW, Malanda B. IDF diabetes atlas: global estimates of diabetes prevalence for 2017 and projections for 2045. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;138:271–281. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2018.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Church FC, Swaisgood HE, Porter DH, Catignani GL. Spectrophotometric assay using o-phthaldialdehyde for determination of proteolysis in milk and isolated milk proteins. J Dairy Sci. 1983;66(6):1219–1227. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(83)81926-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Demuth HU, McIntosh CHS, Pederson RA. Type 2 diabetes Therapy with dipeptidyl peptidase IV inhibitors. Biochim et Biophys Acta Proteins Proteom. 2005;1751(1):33–44. doi: 10.1016/j.bbapap.2005.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hayaloglu AA, Tolu C, Yasar K. Influence of goat breeds and starter culture systems on gross composition and proteolysis in Gokceada goat cheese during ripening. Small Rumin Res. 2013;113(1):231–238. doi: 10.1016/j.smallrumres.2013.03.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Homayouni-Tabrizi M, Shabestarin H, Asoodeh A, Soltani M. Identification of two novel antioxidant peptides from camel milk using digestive proteases: impact on expression gene of superoxide dismutase (SOD) in hepatocellular carcinoma cell line. Int J Pept Res Ther. 2016;22(2):187–195. doi: 10.1007/s10989-015-9497-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim HR, Isono H, Miyata T. Potential antioxidant bioactive peptides from camel milk proteins. Anim Nutr. 2018;4(3):273–280. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2018.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jrad Z, El Hatmi H, Adt I, Girardet JM, Cakir-Kiefer C, Jardin J, Degraeve P, Khorchani T, Oulahal N. Effect of digestive enzymes on antimicrobial, radical scavenging and angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory activities of camel colostrum and milk proteins. Dairy Sci Technol. 2014;94(3):205–224. doi: 10.1007/s13594-013-0154-1. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jrad Z, Girardet JM, Adt I, Oulahal N, Degraeve P, Khorchani T, El Hatmi H. Antioxidant activity of camel milk casein before and after in vitro simulated enzymatic digestion. Mljekarstvo. 2014;64(4):287–294. doi: 10.15567/mljekarstvo.2014.0408. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kamal H, Jafar S, Mudgil P, Murali C, Amin A, Maqsood S. Inhibitory properties of camel whey protein hydrolysates toward liver cancer cells, dipeptidyl peptidase-IV, and inflammation. J Dairy Sci. 2018;101(10):8711–8720. doi: 10.3168/jds.2018-14586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacroix IME, Li-Chan ECY. Inhibition of dipeptidyl peptidase (DPP)-IV and α-glucosidase activities by pepsin-treated whey proteins. J Agric Food Chem. 2013;61(31):7500–7506. doi: 10.1021/jf401000s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li-Chan ECY, Hunag SL, Jao CL, Ho KP, Hsu KC. Peptides derived from Atlantic salmon skin gelatin as dipeptidyl-peptidase IV inhibitors. J Agric Food Chem. 2012;60(4):973–978. doi: 10.1021/jf204720q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Méric E, Lemieux S, Turgeon SL, Bazinet L. Insulin and glucose responses after ingestion of different loads and forms of vegetable or animal proteins in protein enriched fruit beverages. J Funct Foods. 2014;10:95–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2014.05.015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minekus M, Alminger M, Alvito P, Ballance S, Bohn T, Bourlieu C, Carrière F, Boutrou R, Corredig M, Dupont D, Dufour C, Egger L, Golding M, Karakaya S, Kirkhus B, Le Feunteun S, Lesmes U, MacIerzanka A, MacKie A, Brodkorb A. A standardised static in vitro digestion method suitable for food: an international consensus. Food Funct. 2014;5(6):1113–1124. doi: 10.1039/C3FO60702J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nongonierma AB, Cadamuro C, Le Gouic A, Mudgil P, Maqsood S, FitzGerald RJ. Dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) inhibitory properties of a camel whey protein enriched hydrolysate preparation. Food Chem. 2019;279:70–79. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.11.142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nongonierma AB, Paolella S, Mudgil P, Maqsood S, FitzGerald RJ. Identification of novel dipeptidyl peptidase IV (DPP-IV) inhibitory peptides in camel milk protein hydrolysates. Food Chem. 2018;244:340–348. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2017.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavithra K, Vadivukkarasi S. Evaluation of free radical scavenging activity of various extracts of leaves from Kedrostis foetidissima (Jacq.) Cogn. Food Sci Hum Wellness. 2015;4(1):42–46. doi: 10.1016/j.fshw.2015.02.001. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Quirós A, Hernández-Ledesma B, Ramos M, Amigo L, Recio I. Angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitory activity of peptides derived from caprine kefir. J Dairy Sci. 2005;88(10):3480–3487. doi: 10.3168/jds.S0022-0302(05)73032-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahimi M, Ghaffari SM, Salami M, Mousavy SJ, Niasari-Naslaji A, Jahanbani R, Yousefinejad S, Khalesi M, Moosavi-Movahedi AA. ACE- inhibitory and radical scavenging activities of bioactive peptides obtained from camel milk casein hydrolysis with proteinase K. Dairy Sci Technol. 2016;96(4):489–499. doi: 10.1007/s13594-016-0283-4. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Re R, Pellegrini N, Proteggente A, Pannala A, Yang M, Rice-Evans C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Radic Biol Med. 1999;26(9–10):1231–1237. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(98)00315-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salami M, Moosavi-Movahedi AA, Moosavi-Movahedi F, Ehsani MR, Yousefi R, Farhadi M, Niasari-Naslaji A, Saboury AA, Chobert JM, Haertlé T. Biological activity of camel milk casein following enzymatic digestion. J Dairy Res. 2011;78(4):471–478. doi: 10.1017/S0022029911000628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith PK, Krohn RI, Hermanson GT, Mallia AK, Gartner FH, Provenzano MD, Fujimoto EK, Goeke NM, Olson BJ, Klenk DC. Measurement of protein using bicinchoninic acid. Anal Biochem. 1985;150(1):76–85. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(85)90442-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song JJ, Wang Q, Du M, Ji XM, Mao XY. Identification of dipeptidyl peptidase-IV inhibitory peptides from mare whey protein hydrolysates. J Dairy Sci. 2017;100(9):6885–6894. doi: 10.3168/jds.2016-11828. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tidona F, Criscione A, Devold TG, Bordonaro S, Marletta D, Vegarud GE. Protein composition and micelle size of donkey milk with different protein patterns: effects on digestibility. Int Dairy J. 2014;35(1):57–62. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2013.10.018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Uniacke-Lowe T, Fox PF. Equine milk proteins: chemistry, structure and nutritional significance. Int Dairy J. 2010;20(9):609–629. doi: 10.1016/j.idairyj.2010.02.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Zhao S, Yin P, Yan L, Han J, Shi L, Zhou X, Liu Y, Ma C. α-Glucosidase inhibitory activity of polyphenols from the burs of castanea mollissima blume. Molecules. 2014;19(6):8373–8386. doi: 10.3390/molecules19068373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeytünlüoğlu A, Zihnioğlu F. Bazı bitkilerin in vitro koşullarda; potansiyel dipeptidil peptidaz IV inhibitör etkilerinin değerlendirilmesi. Turk J Biochem. 2015;40(3):217–223. [Google Scholar]