Abstract

Among the natural pigments anthocyanins have potential to be applied as natural colourants besides exhibiting wide range of bioactivity. Colouring potential and storage stability of black carrot concentrate (BCC) containing anthocyanins in yoghurt was determined in present investigation. The instrumental colour (CIELAB) values were altered by the addition of BCC in yoghurt in which the L* and b* values decreased, while a* value increased with increasing levels of BCC. Maximum sensory scores were observed for yoghurt with 1.5% BCC, as it was similar to strawberry in colour and appearance. Enhancement in the total anthocyanin, total phenolics and DPPH antioxidant activity was observed with increasing levels of BCC in yoghurt. L* value remained same during storage in both yoghurts, but a* value increased slightly. Similar trend was also noticed in BCC yoghurt for anthocyanins and antioxidant activity. The total phenolic content got enhanced in control, but decreased significantly in BCC yoghurt. Sensory evaluation revealed that scores decreased during storage but the product was acceptable up to 15 days. Our study further confirmed that higher stability and better colouring properties of black carrot concentrate in fermented milk system was due to higher degree of acylation.

Keywords: Black carrot concentrate, Anthocyanin, Antioxidant activity, Colour, Yoghurt

Introduction

Application of natural colours during food preparation is an ancient practice which is evident from the inclusion of saffron, paprika, kokum, turmeric in traditional delicacies. The demand for natural colourants is growing among stakeholders due to concerns over the safety of synthetic food dyes. Permitted synthetic colours are under scrutiny as higher intake on regular basis may lead to mutagenesis and/or carcinogenicity and investigated for their potential toxicity.

Naturally occurring pigments including chlorophylls, carotenoids, anthocyanins, and betalains (Stintzing and Carle 2004) are important determinants of quality attributes in fresh fruits and vegetables. Natural pigments have been reported to exhibit several bioactive properties such as anti-oxidant, antibacterial, antifungal, anti-leprotic, antiviral and anti-inflammatory activities (He and Giusti 2010). Most of these health properties are related to the ability of natural pigments to scavenge free radicals and other reactive oxygen species or their interference in microbial metabolism. Among the natural pigments, anthocyanins constitutes an important class of water soluble pigments that impart attractive red, blue, pink and purple colours to fruits, vegetables, cereals, legumes and flowers. On commercial scales anthocyanins are sourced from a variety of fruits and vegetables including grape skin, elderberry, blackcurrant, blackberry and raspberry, but the acylated anthocyanins predominates in red radishes, red potatoes, red cabbages, and black carrots. Acylatation of anthocyanins improved their stability under varying pH, thermal treatments, exposure to light and oxygen (Giusti and Wrolstad, 2003). Among the fermented dairy products, yoghurt is immensely popular because of its unique sensory and nutritional characteristics. Innovation made in yoghurts for enhancing the organoleptic, nutritional and therapeutic characteristics include addition of various non-dairy ingredients, protein-enrichment, incorporating dietary fibers and phytochemicals. Coconut yoghurt made with reduced fat content was rated better in comparison to full fat one and could be an attractive options for vegans (Chetachukwu et al. 2019). Khaledabad et al. (2020) noticed that addition of 0.25% zedo gum and spirulina in probiotic yoghurt enhanced the probiotic counts, antioxidant activity. Researchers applied anthocyanin-rich ingredients such as Eutrepe juice (Coisson, et al. 2005); powder from Peruvian berries (Wallace and Giusti 2008); dried roselle calyx (Daniel et al. 2013) and mulberry juice (Byamukama et al. 2014) for colouring yoghurt and observed improvement not only in colour but also in the bioactivity of yoghurt. However, addition of anthocyanin-rich preparations may adversely affect the flavour of the yoghurt, leads to sedimentation, and affected starter’s growth. Another issue which limits the use of anthocyanins as food colour is their stability which depends on the extent of heating, pH, oxygen concentration, light and other food constituents. Black carrot (Daucus carota subsp. sativus) contains higher concentration of acylated anthocyanins (41%) with excellent stability under varied conditions (Stintzing et al. 2002). Black carrot extract exhibits peach to strawberry red colour at acidic pH and appears to be an ideal natural alternative to synthetic food colourants like FD and C Red #40 (Allura Red). Since it is natural, hence does not require any declaration with an INS or E-number on labelling. Literature pertaining to anthocyanin profiling, antioxidant activity and application of black carrot anthocyanins indicate that it has potential to substitute currently available anthocyanin preparations as colouring matter in wide range of products. However, it has not yet been evaluated for coloring of dairy products including beverages, fermented milks, ice cream and other dairy desserts. Realizing the potential of black carrot concentrate as natural colourant investigation was carried out to determine its colouring properties in yoghurt and evaluate its stability during storage.

Material and methods

Materials

Pooled milk was procured from the Experimental Dairy of ICAR-NDRI, Karnal (India) and yoghurt culture (NCDC 263) was procured from the National Collection of Dairy Cultures, ICAR-NDRI, Karnal. Black carrot concentrate (BCC) was gifted by the Nature’s Solution Private Ltd, New Delhi. Total soluble solids, total anthocyanin content and total phenolic content (TPC) of BCC were 42°Brix, 22.72 g cyanidin-3-glucoside/L and 101.95 g GAE/L, respectively. Synthetic colourant erythrosine was procured from the local market of Karnal.

Preparation of BCC added yoghurt

The procured milk was standardized to 3% fat and 11% MSNF (milk solids not fat), and to which 10% powdered sugar and 0.1% high methoxyl pectin were added into it. Mix was homogenized at 2000 psi, heat processed to 90 °C for 20 min, and, cooled to 42 °C, Black carrot concentrate (BCC) was added at 0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0% level separately to each batch of and inoculated with 1% yoghurt culture (NCDC 263). Control yoghurt was also prepared by adding 50 ppm of synthetic colourant i.e. Erythrosine. The incubation was stopped once the pH of yoghurt reached to 4.5–4.6 and shifted immediately to refrigerator till further analysis.

Physico-chemical analysis of yoghurt

pH and titratable acidity

The pH of the yoghurt samples were determined by insetting the electrode of the pH meter (pHTestr® 30, OAKLON®, USA) probe into thoroughly mixed sample. Titratable acidity was determined as per IS: SP: 18, Part XI (1981). Acidity of milk was expressed as percent lactic acid (% LA (lactic acid).

Sample Preparation for total phenolic, total anthocyanin and antioxidant activity analysis

For sample preparation the method suggested by Wallace and Giusti (2008) was adopted. 10 g yoghurt was thoroughly mixed with 30 mL of 0.1% acidified (HCl of 37% strength) methanol for 5 min and centrifuged (Laboratory centrifuge, Sigma 2–16 PK, USA) at 2250 g for 15 min at 4 °C. The extraction procedure was repeated thrice with each sample to ensure maximum recovery of anthocyanins. The supernatant in each case was carefully filtered and concentrated to a known volume (10 mL) at 40 °C in rotary vacuum evaporator (IKA® RV10) and the concentrates were used for further analysis.

Total anthocyanin content

Total anthocyanin content of the BCC added yoghurt was analyzed by the pH differential method (Lee et al. 2005). Sample extract as prepared in Sect. 2.3.2 were diluted in pH 1.0 buffer (potassium chloride, 0.025 M) and pH 4.5 buffer (sodium acetate, 0.4 M), followed by absorbance recording at two different wavelength i.e. 520 nm and 700 nm using UV–Vis Spectrophotometer (UV–VIS 2700, Shimadzu, Japan). Total absorbance was calculated by Eq. (1) and converted to milligram of cyanindin-3-glucoside equivalents per milliliter according to Eq. (2). Results were expressed as mg cyanidin-3-glucoside equivalent/L or kg of the product.

| 1 |

| 2 |

where A = Total absorbance, MW = Molecular weight of cyaniding 3-glucoside (449.2 g/ mol), DF = Dilution factor for the sample, ɛ = Molar extinction coefficient for Cyanidin3-glucoside (26,900 L × mol−1 × cm−1), 1 = path length in cm, 103 = factor for conversion from g to mg.

Total phenolic content

Method described by Singleton and Rossi (1965) with slight modifications was adopted for the estimation of TPC. 0.5 mL of diluted aliquot of yoghurt sample was mixed with 2.5 mL of Folin-ciocalteu solution (0.2 N) with rigorous shaking for 5 min. After 5 min 2 mL 7.5% sodium carbonate solution was added and mixed well, incubated for 2 h followed by measuring the absorbance at 765 nm. Results were expressed as mg of Gallic acid equivalent/ kg. TPC was assessed by plotting the gallic acid calibration curve (from 0 to 100 mg/L) and expressed as mg of Gallic acid equivalent (GAE) per kg sample.

Antioxidant activity determination

The antioxidant activity of the samples were determined using DDPH- free radical scavenging method employed by Brand-Williams et al. (1995) with slight modifications. 0.1 mL sample aliquot was added to 2.9 mL of 100 µM DPPH solution with thorough mixing. Absorbance was recorded after 30 min incubation at 517 nm. A standard curve was also prepared by using the varied concentration of Trolox and results were expressed in terms of µg of Trolox Equivalent.

Colour measurement of yoghurt

Surface colour of BCC and control yoghurt was determined for CIE (Commission Internationalede l'éclairage) L*, a*, b*, Chroma, whiteness index and hue angle value using a Colorflex colorimeter (Hunterlab Associate Laboratory, Reston, Virginia, USA) using the standard illuminant D65 and 10° observer. The colour coordinates as reflected in CIELAB namely L*, a* and b* represented whiteness, redness to greenness and yellowness to blueness, respectively. Product samples (in triplicate) were brought to room temperature before colour determination. The primary data was computed for Chroma, hue angle and whitening index using below given equations.

| 3 |

| 4 |

| 5 |

Sensory evaluation of yoghurt

Yoghurt samples were evaluated organoleptically for different sensory attributes using a scorecard consisting of Flavour (45), Body and texture (30), Colour & appearance (10), Acidity (10), Container & closure (5) and Overall acceptability score (100) by a semi-trained panel of judges drawn from the faculty and research scholars of the institute. Refrigerated yoghurt samples were presented to 10 panelists just before judging.

Storage stability

Yoghurt with optimized level of black carrot concentrate and control yoghurt containing synthetic colourant were analyzed for physico-chemical and sensory attributes at regular interval of 3 days up to 15 days at refrigerated storage of 7 ± 1 °C. The physico-chemical analysis includes acidity, pH, colour attributes, total anthocyanin, TPC, antioxidant activity and sensory analysis with composite scorecard was carried out. Degradation kinetics of anthocyanins was calculated by plotting a graph between total anthocyanin of the BCC yoghurt against time (Storage days) with Zero, First and Second order reactions and linear regression analysis was carried out to evaluate the adequacy of fir of anthocyanin degradation kinetic model. The degradation rate constant (k) was determined from the first derivative of the curve of the plotted using Eq. (6) and the half-lives were calculated using Eq. (7).

| 6 |

| 7 |

where A0 = Initial concentration of anthocyanin.At = Concentration of anthocyanin after t (storage days) time. t = storage time (days). t1/2 = Half-life (days). k = Degradation constant. ln(2) = Concentration at half-life ).

Statistical analysis

All the experiments were carried out in triplicate. Results are expressed as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM). The data obtained were subjected ANOVA method using IBM SPSS Statistics software (version 20) and the means were compared using Duncan post hock test for significant differences (p < 0.05).

Results and discussion

Effect of level of black carrot concentrate on colour attributes of yoghurt

The L* of 0.5% BCC incorporated yoghurt was 77.51 which decreased to 73.33, 67.00 and 63.54, respectively; with BCC addition @ 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0 percent (Table 1). Lowering of the L* value is related to the enhancement in BCC levels leading to an increase in the anthocyanin concentration and other phenolic compounds. The whitening index was similar to lightness value and followed the trend by enhancing the BCC concentration. The decrease in L* and whiteness index was significant (p < 0.05).The redness value (a*) was 4.04 at 0.5% level of BCC and it increased to 7.35, 9.14 and 10.33 @ 1.0 1.5 and 2.0 percent levels of BCC, respectively. Under low pH there was predominance of pink colour in yoghurts owing to the transformation of anthocyanins. A lowering in yellowness (b*) values was observed which indicated that with increasing concentration of BCC the yoghurt colour becomes purple. Changes in colour values were highly significant for all the colour attributes (p < 0.05). On the other side, chroma intensity increased and hue angle decreased significantly with increasing level of BCC (Table 1). All the yoghurt samples were pink to red in colour which is due to liberation of hydrogen ions under acidic pH that resulted in bathochromic shift of flavylium cation. Control yoghurt exhibited significantly higher L*, b* values, but a* value was similar to 1% BCC added yoghurt. These variations might be related to the colouring characteristics of the dye used in yoghurt. BCC had several classes of anthocyanins and other phenolics, which influenced the colour of yoghurt through interaction among themselves and with yoghurt constituents.

Table 1.

Physico-chemical and sensory analysis of yoghurt added with different levels of Black carrot concentrate (BCC)

| Addition rate of black carrot concentrate (%) in yoghurt | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | 0.5% | 1% | 1.50% | 2% | |

| Physico-chemical parameter* | |||||

| TPC (as mg GAE/kg) | 48.17 ± 0.53e | 101.86 ± 0.1d | 147.74 ± 1.1c | 198.26 ± 0.7b | 253.26 ± 0.95a |

| TAC (as cya-3-glu mg/kg) | – | 9.05 ± 0.06d | 20.74 ± 0.20c | 30.86 ± 0.38b | 39.81 ± 0.15a |

| DPPH AA (µg of TEAC/g) | 37.83 ± 0.6e | 95.30 ± 0.4d | 138.53 ± 1.2c | 182.94 ± 0.6b | 230.16 ± 0.1a |

| L* | 82.79 ± 0.02e | 77.51 ± 0.02a | 73.33 ± 0.02b | 67.00 ± 0.02c | 63.54 ± 0.02d |

| a* | 7.97 ± 0.01c | 4.04 ± 0.01d | 7.35 ± 0.02c | 9.14 ± 0.03b | 10.33 ± 0.04a |

| b* | 5.88 ± 0.03e | 2.09 ± 0.01a | 0.78 ± 0.02b | − 0.68 ± 0.05c | − 2.69 ± 0.02d |

| Chroma value | 9.91 ± 0.01a | 4.55 ± 0.01d | 7.39 ± 0.01c | 9.16 ± 0.02b | 10.67 ± 0.04a |

| Hue angle (rad) | 0.64 ± 0.003a | 0.48 ± 0.002a | 0.11 ± 0.002b | − 0.07 ± 0.005c | − 0.25 ± 0.002d |

| Acidity (% LA) | 0.861 ± 0.01a | 0.895 ± 0.01a | 0.886 ± 0.01a | 0.880 ± 0.01b | 0.886 ± 0.01a |

| pH | 4.54 ± 0.01aA | 4.52 ± 0.01a | 4.47 ± 0.01a | 4.47 ± 0.01a | 4.52 ± 0.01a |

| Sensory parameter** | |||||

| Flavour | 40.00 ± 2.10b | 37.17 ± 1.72c | 39.17 ± 0.98b | 42.17 ± 0.75a | 40.00 ± 0.63b |

| Body and texture | 27.83 ± 0.75a | 23.33 ± 2.50b | 23.67 ± 1.63b | 28.17 ± 0.75a | 26.50 ± 0.84a |

| Acidity | 7.42 ± 0.38a | 6.83 ± 1.17c | 7.58 ± 0.49bc | 9.08 ± 0.38a | 7.75 ± 0.52b |

| Colour and Appearance | 7.42 ± 0.38b | 6.17 ± 0.98c | 7.42 ± 0.38b | 9.00 ± 0.32a | 7.33 ± 0.41b |

| Overall Acceptability | 87.33 ± 2.25a | 77.83 ± 4.12d | 82.33 ± 1.47c | 93.08 ± 0.86a | 86.25 ± 1.61b |

Data are presented as mean ± SEM;

a−dMean values (*n = 3, **n = 10) with different superscripts in same row differ significantly (ρ < 0.05, Duncan post-hoc test)

Effect of level of black carrot concentrate on sensory attributes of yoghurt

Anthocyanins though may improve the colour and appearance of many food items but may adversely affect the sensory attributes due to presence of certain phenolics that may impart astringent and bitter taste. There was a significant effect of BCC addition on flavour of yoghurt and maximum score was obtained with 1.5 percent BCC (Table 2). Further increase in the BCC level caused significant (p < 0.05) lowering in flavour scores. However, the flavour score was acceptable at all concentration of BCC probably because yoghurt was sweetened one that has masked the off flavour. Phenolic compounds present in BCC might have contributed wide range of flavour notes has affected the flavour of yoghurt. Phenolics are associated with certain peculiar aroma note mainly medicinal, bitterness and astringency (Duffy et al. 2016) and panelists indicated such flavour perception at higher levels of addition. There was significantly higher textural score at 1.5% of BCC and panelist reported slightly loose body and texture at higher and lower levels of BCC (Table 2). Effect of BCC constituents on texture might be due to the inhibition of yoghurt starter. Similar trend was also noticed for acidity scores as significantly higher score was observed for yoghurt made with 1.5% BCC (Table 2). Although, there was not much variation in acidity and pH values of yoghurt, but probably the colour of yoghurt containing 1.5% BCC resembled to strawberry that might have influenced the panelists. BCC concentration had a significant effect on colour and appearance of yoghurt and maximum score was observed for yoghurt made with 1.5 percent BCC. At 0.5% BCC yoghurt was dull whereas at higher levels panelist observed enhanced darkness in product which was negatively evaluated. The overall acceptability scores were 87.33, 77.83, 82.33, 93.08 and 86.25 in control and yoghurt made with BCC @ 0.5, 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0 percent, respectively (Table 2).

Table 2.

Linear regression equation, R2 value and RMS error value of zero order, first order and second order of BCC anthocyanin degradation in yoghurt during storage at 7 ± 1 °C

| Order of reaction | Linear regression equation | R2 | RMS error value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Zero | y = −0.0808x + 31.855 | 0.98 | 2.347 |

| First | y = −0.0026x + 3.4613 | 0.98 | 0.733 |

| Second | y = 8E−0.5x + 0.0314 | 0.98 | 1.093 |

Effect of level of Black carrot concentrate on physico-chemical analysis of the yoghurt

The BCC addition at any concentration had no significant effect (p > 0.05) on acidity and pH of the yoghurt. Final pH was targeted in the range of 4.5–4.6 and samples were removed once the pH value was achieved. TPC of 48.17 GAE mg/kg in control yoghurt was increased by BCC addition to 2–5 times (Table 1). Increase in TPC of yoghurt is expected as BCC possess wide range of phenolics and the rise in TPC was significant (p < 0.05) in yoghurt. BCC was prepared by concentrating the enzymatically extracted black carrot juice that contained anthocyanin and associated phenolics. Black carrots have been reported to possess higher concentrations of ρ-coumaric, ferulic, ρ-hydroxy benzoic acid (PABA) and sinapic acid (Sharma et al. 2012) Algarra et al. (2014). reported TPC as 187.8 and 492 mg GAE/100 g Fruit weight (FW) in two black carrot cultivars, whereas it was only 9.4 mg GAE/100 g in orange carrots. Higher levels of phenolics in black carrot was due to the presence of anthocyanins that account for 25–50% of total phenolics.

Initial anthocyanin content of 9.79 mg/kg in 0.5% BCC yoghurt enhanced to 20.81, 31.03 and 41.25 mg/kg on addition of 1.0, 1.5 and 2.0% BCC, respectively (Table 1). Khandare et al. (2011) reported that pectin hydrolyzing enzymes enhanced the 33% juice yield, 27% total phenolics, 46% total flavonoids and 100% total anthocyanins. Further they noted the values of total phenols and total anthocyanins in the range of 300–382 mg GAE/100 mL juice and 504–1005 mg/L of juice, respectively. BCC incorporation also improved the antioxidant activity of the yoghurt and it was approximately 2.5–6.0 times higher than control. Enhancement in DPPH radical scavenging activity in yoghurt was due to increase in total phenolics and anthocyanin content. Enhancement in anti-oxidative activities could also be related to proteolysis products formed during fermentation by yoghurt starters. Antioxidant activities of anthocyanins involves scavenging of free radicals, reactive oxygen species (ROS), inhibition of lipid oxidation, chelation of heavy metals and induction of anti-oxidative enzymes (Miguel 2011).

Change in pH and acidity (%LA) during storage

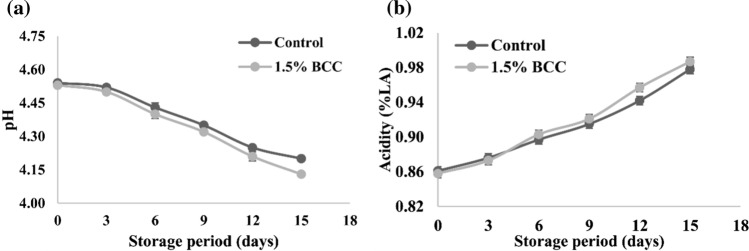

Sensory characteristics, safety and shelf-life of fermented milks depends on their acidity and pH. The acidity values gradually increased during the storage in both control and BCC added yoghurt during storage. Initial acidity of 0.86% LA in control and BCC yoghurt increased to 0.98% LA at the end of 15 days (Fig. 1). With increased in acidity pH lowered from 4.54 to 4.12 and 4.53 to 4.13 for control and BCC added yoghurt, respectively. There was non-significant (p < 0.05) variation in acidity of control and BCC added yoghurt except on 12th day. Addition of BCC and subsequent increase in the levels of phenolic is expected to have an inhibitory effect on starter bacteria present in yoghurt. Shah et al. (1995) noticed that supplementation of grape seed extracts in yoghurt did not influenced the pH of commercial blueberry yoghurt. In another study there was no significant difference observed in pH of control and supplemented samples throughout the storage (Chouchouli et al. 2013).

Fig. 1.

Changes in a pH and b acidity (%LA) of Control and 1.5% BCC yoghurt during storage at 7 ± 1 °C

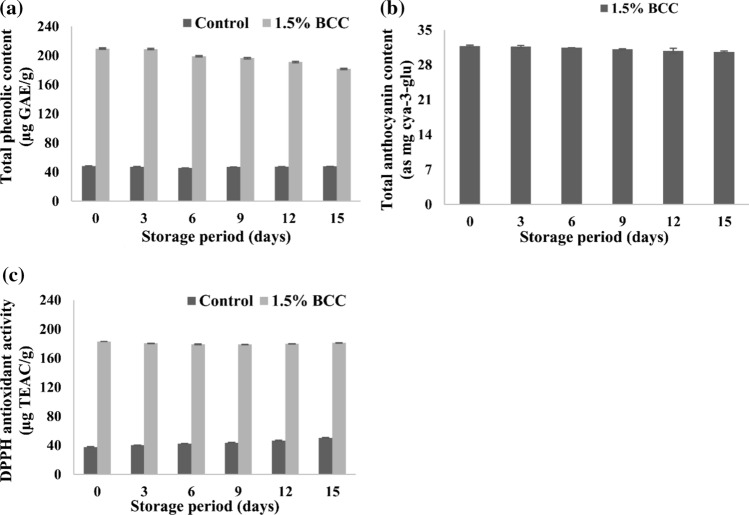

Change in total phenolics content (mg GAE/kg) and antioxidant activity (µg TEAC/g) during storage

The TPC in BCC yoghurt lowered slowly during storage, on the other side no definite trend was observed for control yoghurt. Initial TPC of 209.55 mg/kg in yoghurt decreased to 181.72 mg/kg at the end of 15 days of storage (Fig. 2). Decrease in TPC was significant after 3rd day of storage (p < 0.05), inconsistent trend was noticed in control yoghurt. In control, the initial decrease in the TPC may be due to the degradation of natural phenolics present in it. Later on, increase in TPC may be due to the release of aromatic amino acids on proteolysis. Continuous decline in TPC may be related to degradation of BCC polyphenols by yoghurt microflora. Our findings are in consonance with results of Daniel et al. (2013) who reported that TPC in Roselle calyxes added yoghurt lowered by 15.5% after 36 days. There was about 7.5% decrease in the TPC of BCC added yoghurt after 15 days. About 14% reductions in TPC was observed within 24 h in strawberry added yoghurt; however, afterwards only 10% decrease occurred at the end of 28 days (Oliveira et al. 2015).

Fig. 2.

Changes in a Total phenolic content b *Total anthocyanin content and (c) DPPH antioxidant activity of Control and 1.5% BCC yoghurt during storage at 7 ± 1 °C

The DPPH radical scavenging activity in control yoghurt enhanced significantly during storage, whereas there was no definite trend observed in BCC yoghurt. The antioxidant activity of control yoghurt enhanced from initial value of 37.83 µg TEAC /g significantly (p < 0.05) to 50.21 µg TEAC/g at the end of 15 days (Fig. 3). Although, change in antioxidant activity was in the range of 1–2.5 µg TEAC/g, however it was statistically significant (p < 0.05). Initial decrease in anti-oxidant activity of yoghurt is owing to reduction in levels of anthocyanin. However, release of antioxidant peptides via proteolysis on milk proteins increased the antioxidant activity at later stages of storage. Farvin et al. (2010) noticed enhanced anti-oxidant activity in yoghurt and attributed it to production of free amino acids and small peptides (< 1000 Da).

Fig. 3.

Changes in colour attributes a L*, b a*, c b*, d Chroma, e Hue angle of Control and 1.5% BCC yoghurt during storage at 7 ± 1 °C

Protein/Peptide-polyphenol interaction during 1st week of storage owing to the release of free hydroxyl group and initiation of covalent bonding could be the possible explanation for lower anti-oxidant activity between protein and polyphenol interaction (Viljanen et al. 2004). Masking of antioxidant activity was due to interaction of polyphenols with proteins (Heinonen et al. 1998), however, masking depends on both type and amount of protein and phenolic. Arts et al. (2002) noticed maximum inhibitory effect due to the complexation of casein with gallic acid in tea extract.

The total anthocyanin content of BCCI containing yoghurt gradually decreased during storage. The initial anthocyanin content of 31.761 mg cya-3-glu/L decreased to 30.626 mg cya-3-glu/L at the end of 15 days storage, which accounts for only 3.57% loss (Fig. 2). Anthocyanins undergo polymerization with other phenolics and subjected to degradation by endogenous or exogenous enzymes resulting in their concentration (Skrede et al. 2004; Scibisz et al. 2012). Yoghurt starter metabolites especially hydrogen peroxide may accelerate the degradation of anthocyanins through oxidation (Scibisz et al. 2012). Kinetic investigation indicates that alteration in anthocyanins followed first order reaction during storage of yoghurt with highest R2 and lower RMS (root mean square) error value. The R2 values were in the range of 0.97–0.98 for zero, first and second order reaction. Anthocyanins degradation mostly follows the first order reaction kinetic with respect to time (Giusti and Wrolstad 1996). The anthocyanin degradation constant (k-value) in BCC yoghurt was 2.43 × 10–3 day−1 and calculated half-life value was 285.60 days (Table 3). Wallace et al. (2008) noted that Yoghurt containing non-acylated anthocyanins from Berberies boliviana had the half-life of 125 days, while it was 550.2, 232.6, and 128.9 days for full fat, low fat and not fat yoghurt made with acylated anthocyanins from purple carrot. Monomeric anthocyanins of roselle calyx added yoghurt poorly correlated with first-order kinetics probably due to matrix complexity and polymerization reactions (Daniel et al. 2013).

Table 3.

Degradation rate constant (k) and half-life of BCC anthocyanins in yoghurt during storage at < 4 °C

| Degradation rate constant (k) | 2.43 × 10–3 day−1 |

|---|---|

| Half-life value (t1/2) | 285.60 days |

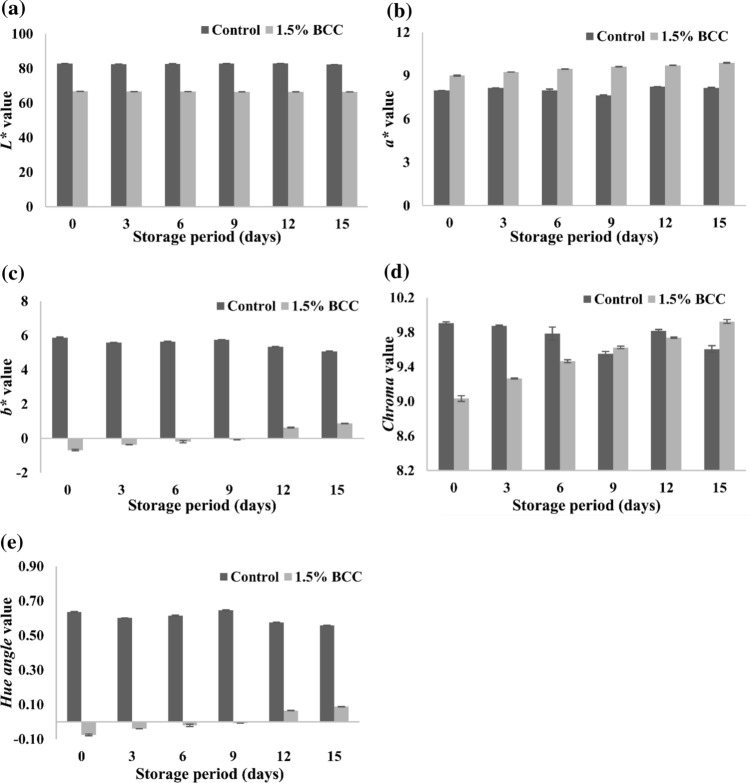

Change in colour properties of yoghurt during storage

Among the colour indices L* values decreased non-significantly (p < 0.05) in BCC yoghurt and while no definite trend was observed in control samples. Initial L* value of 66.81 in experimental yoghurt decreased to 66.49 at the end of storage (Fig. 3a). Wallace and Giusti (2008) observed that Yoghurt added with 20 mg cy-3-glu equivalent/100 g from purple carrot showed the lower L* and more chroma value as compared to commercial blueberry yoghurt but similar visual shade was observed. Further they reported only minor changes in the colour of yoghurt during 2 months of storage.

The redness value marginally increased during storage of BCC yoghurt but there was no definite trend observed in control yoghurt (Fig. 3b). The increase in the redness of BCC yoghurt was attributed mainly to structural changes in the anthocyanin pigment with reduction in pH. The yellowness value increased during storage of BCC yoghurt and there slight reduction in control yoghurt. The initial b* value of BCC yoghurt, which was –0.68 increased to 0.87 at the end of 15 days storage (Fig. 3c). Increase in b* value reflected the reduction in blueness of yoghurt because bluish quinoidal base transformed into red flavanium cation. Both chroma and hue angle increased marginally during the storage in BCC yoghurt (Fig. 3d, e).

Effect of black carrot concentrate on sensory attributes of yoghurt during storage

Sensory scores decreased during the storage in both control and BCC yoghurt. The flavour scores of control and BCC added yoghurt samples scores were 40 and 40.50, respectively on initial day that decreased significantly (p < 0.05) to 36.33 and 36.17, respectively after 15 days (Table 4). Reduced flavour scores might be related to two phenomenon including acidity development leading to the transformation of polyphenols and microbial enzyme mediated production of peptides and free amino acids. The body and texture score of control and BCC yoghurt decreased significantly (p < 0.05) throughout the storage period. Marginal decrease in body and texture scores was due to the reduction in firmness and viscosity of the yoghurt. The uniformity of colour and appearance is essential for the consumer acceptance of the product. There was minor but yet significant (p < 0.05) increase in control and BCC yoghurt till 9th day then it lowered marginally. There was non- significant variation in colour and appearance scores of both types of yoghurt. The acidity scores of both yoghurts increased throughout the storage period, but the increase was non-significant (p < 0.05) (Table 4). Overall acceptability of the control and BCC yoghurt lowered significantly (p < 0.05) but it was more on 9th days onwards. There was no significant (p < 0.05) difference between both yoghurts on same day throughout the storage period. The reduction in overall acceptability was mainly due to perceived phenolic, bitter and stringent taste along with slight syneresis.

Table 4.

Changes in sensory attributes scores of control and BCC yoghurt during storage at 7 ± 1 °C

| Storage days | Flavour | Body and texture | Colour and appearance | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | BCC | Control | BCC | Control | BCC | |

| 0th | 40.00 ± 2.10aA | 40.50 ± 1.87aA | 27.83 ± 0.75aA | 27.17 ± 1.17aB | 7.42 ± 0.38bA | 7.50 ± 0.45cA |

| 3rd | 40.17 ± 1.72aA | 40.33 ± 1.63aA | 27.00 ± 0.89abA | 26.00 ± 1.41abA | 7.83 ± 0.52abA | 7.58 ± 0.38bcA |

| 6th | 38.33 ± 2.16abA | 38.67 ± 1.03abA | 25.83 ± 0.98bcA | 26.50 ± 1.05abA | 7.92 ± 0.38abA | 8.08 ± 0.38abA |

| 9th | 37.83 ± 0.75bA | 37.17 ± 1.47bcA | 25.17 ± 0.98cA | 26.50 ± 1.52abA | 8.08 ± 0.38aA | 8.33 ± 0.41aA |

| 12th | 36.67 ± 1.63bA | 36.33 ± 1.51cA | 24.67 ± 1.51cA | 26.00 ± 1.10abB | 7.67 ± 0.41abA | 8.08 ± 0.38abA |

| 15th | 36.33 ± 1.21bA | 36.17 ± 1.60cA | 24.50 ± 1.05cA | 25.00 ± 1.10bA | 7.83 ± 0.26bA | 7.83 ± 0.41abcA |

| Storage days | Acidity | Container and closure | Overall acceptability | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | BCC | Control | BCC | Control | BCC | |

| 0th | 7.42 ± 0.38aA | 7.42 ± 0.38aA | 4.67 ± 0.52aA | 4.67 ± 0.52aA | 87.33 ± 2.25aA | 87.25 ± 2.55aA |

| 3rd | 7.50 ± 0.45aA | 7.58 ± 0.49aA | 4.50 ± 0.55aA | 4.50 ± 0.55aA | 87.00 ± 3.21aA | 86.00 ± 0.89abA |

| 6th | 7.50 ± 0.45aA | 7.53 ± 0.49aA | 4.50 ± 0.55aA | 4.50 ± 0.55aA | 84.08 ± 1.80bA | 85.33 ± 1.69abA |

| 9th | 7.58 ± 0.38aA | 7.75 ± 0.52aA | 4.50 ± 0.55aA | 4.50 ± 0.55aA | 83.17 ± 0.93bcA | 84.25 ± 2.81bcA |

| 12th | 7.58 ± 0.59aA | 7.75 ± 0.69aA | 4.67 ± 0.52aA | 4.67 ± 0.52aA | 81.25 ± 1.17cA | 82.83 ± 1.89cB |

| 15th | 7.67 ± 0.61aA | 7.83 ± 0.26aA | 4.50 ± 0.55aA | 4.50 ± 0.55aA | 80.83 ± 1.03cA | 81.33 ± 1.13dA |

Data are presented as means ± SEM (n = 10)

a−eMeans with different superscripts in same column differ significantly (ρ < 0.05, Duncan);

A−BMeans with different superscripts in same row differ significantly (ρ < 0.05, Duncan)

Conclusion

Black carrot anthocyanins addition in yoghurt formulation, not only imparted the desirable strawberry red colour, but enhanced the total anthocyanins, TPC and antioxidant activity of the yoghurt. BCC incorporation @ 1.5 percent yielded an organoleptically acceptable product with desirable colour indices (L*, a*, b*, chroma & hue). Besides providing the colouring properties BCC can add value to yoghurt with enhanced health benefits through antioxidant activity. There was slight decrease in TPC, anti-oxidant activity, pH, L*, b* value, but total acidity, a* value increased marginally. Product remained acceptable up to 15 days of refrigerated storage. There was only 3.57 percent reduction in the total anthocyanins during 15 day’s storage indicating higher degree of pigment stability. Predominance of acylated anthocyanins in BCC appears to be one of the reasons. Findings of our investigation provide an opportunity for dairy industry to use black carrot anthocyanins concentrate in processed dairy products as natural colourant with better stability besides improving the nutritional and health promoting virtues. It will assist them in diversifying their natural additive based product profile.

Acknowledgement

The authors acknowledge the financial support received by first author from ICAR-National Dairy Research Institute to carry out the research work.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Bhavesh Baria, Email: bariabhavesh2@gmail.com.

Ashish Kumar Singh, Email: aksndri@gmail.com.

Narender Raju Panjagari, Email: pnr.ndri@gmail.com.

Sumit Arora, Email: sumit123@gmail.com.

P. S. Minz, Email: psminz@gmail.com

References

- Algarra M, Fernandes A, Mateus N, de Freitas V, da Silva JCE, Casado J. Anthocyanin profile and antioxidant capacity of black carrots (Daucus carota L. ssp. sativus var. atrorubens Alef.) from Cuevas Bajas, Spain. J of Food Comp and Anal. 2014;33(1):71–76. doi: 10.1016/j.jfca.2013.11.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alizadeh Khaledabad M, Ghasempour Z, Moghaddas Kia E, Rezazad Bari M, Zarrin R. Probiotic yoghurt functionalised with microalgae and Zedo gum: chemical, microbiological, rheological and sensory characteristics. Int J of Dairy Tech. 2020;73(1):67–75. doi: 10.1111/1471-0307.12625. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Arts MJ, Haenen GR, Wilms LC, Beetstra SA, Heijnen CG, Voss HP, Bast A. Interactions between flavonoids and proteins: effect on the total antioxidant capacity. J of Agri and Food Chem. 2002;50(5):1184–1187. doi: 10.1021/jf010855a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brand-Williams W, Cuvelier ME, Berset CLWT. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food Sci and Tech. 1995;28(1):25–30. doi: 10.1016/S0023-6438(95)80008-5. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Byamukama R, Andima M, Mbabazi A, Kiremire BT. Anthocyanins from mulberry (Morus rubra) fruits as potential natural colour additives in yoghurt. African J of Pure and App Chem. 2014;8:182–190. [Google Scholar]

- Chetachukwu AS, Thongraung C, Yupanqui CT. Development of reduced-fat coconut yoghurt: physicochemical, rheological, microstructural and sensory properties. Int J of Dairy Tech. 2019;72(4):524–535. doi: 10.1111/1471-0307.12600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chouchouli V, Kalogeropoulos N, Konteles SJ, Karvela E, Makris DP, Karathanos VT. Fortification of yoghurts with grape (Vitis vinifera) seed extracts. LWT-Food Sci and Tech. 2013;53(2):522–529. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2013.03.008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Coisson JD, Travaglia F, Piana G, Capasso M, Arlorio M. Euterpe oleracea juice as a functional pigment for yogurt. Food Res Int. 2005;38:893–897. doi: 10.1016/j.foodres.2005.03.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Daniel L, Diana E, Barragan Huerta BE, Vizcarra Mendoza MG, Anaya Sosa I. Effect of drying conditions on the retention of phenolic compounds, anthocyanins and antioxidant activity of roselle (Hibiscus sabdariffa L.) added to yogurt. Int J of Food Sci Tech. 2013;48(11):2283–2291. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy VB, Rawal S, Park J, Brand MH, Sharafi M, Bolling BW. Characterizing and improving the sensory and hedonic responses to polyphenol-rich aronia berry juice. Appetite. 2016;107:116–125. doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2016.07.026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farvin KS, Baron CP, Nielsen NS, Jacobsen C. Antioxidant activity of yoghurt peptides: Part 1-in vitro assays and evaluation in ω-3 enriched milk. Food chem. 2010;123(4):1081–1089. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.05.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giusti MM, Wrolstad RE. Acylated anthocyanins from edible sources and their applications in food systems. Biochem Engi J. 2003;14:217–225. doi: 10.1016/S1369-703X(02)00221-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Giusti MM, Wrolstad RE. Radish anthocyanin extract as a natural red colorant for maraschino cherries. J of Food Sci. 1996;61(4):688–694. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.1996.tb12182.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- He J, Giusti MM. Anthocyanins: natural colourants with health-promoting properties. Ann Rev Food Sci Tech. 2010;1:167–187. doi: 10.1146/annurev.food.080708.100754. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen M, Rein D, Satue-Gracia MT, Huang SW, German JB, Frankel EN. Effect of protein on the antioxidant activity of phenolic compounds in a lecithin−liposome oxidation system. J of Agri and Food Chem. 1998;46:917–922. doi: 10.1021/jf970826t. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khandare RV, Kabra AN, Kurade MB, Govindwar SP. Phytoremediation potential of Portulaca grandiflora Hook (Moss-Rose) in degrading a sulfonated diazo reactive dye Navy Blue HE2R (Reactive Blue 172) Biore Tech. 2011;102(12):6774–6777. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2011.03.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Durst RW, Wrolstad RE. Determination of total monomeric anthocyanin pigment content of fruit juices, beverages, natural colorants, and wines by the pH differential method: collaborative study. J of AOAC Int. 2005;88(5):1269–1278. doi: 10.1093/jaoac/88.5.1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miguel MG. Anthocyanins: Antioxidant and/or anti-inflammatory activities. J of Appl Pharma Sci. 2011;1:7–15. [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira A, Alexandre EM, Coelho M, Lopes C, Almeida DP, Pintado M. Incorporation of strawberries preparation in yoghurt: impact on phytochemicals and milk proteins. Food Chem. 2015;171:370–378. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.08.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scibisz I, Ziarno M, Mitek M, Zaręba D. Effect of probiotic cultures on the stability of anthocyanins in blueberry yoghurts. LWT-Food Sci and Tech. 2012;49(2):208–212. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2012.06.025. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shah NP, Lankaputhra WE, Britz ML, Kyle WS. Survival of Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bifidobacterium bifidum in commercial yoghurt during refrigerated storage. Int Dairy J. 1995;5(5):515–521. doi: 10.1016/0958-6946(95)00028-2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma KD, Karki S, Thakur NS, Attri S. Chemical composition, functional properties and processing of carrot—a review. J of Food Sci and Tech. 2012;49:22–32. doi: 10.1007/s13197-011-0310-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singleton VL, Rossi JA. Colorimetry of total phenolics with phosphomolybdic-phosphotungstic acid reagents. American J of Enol and Viti. 1965;16(3):144–158. [Google Scholar]

- Skrede G, Larsen VB, Aaby K, Jorgensen AS, Birkeland SE. Antioxidative properties of commercial fruit preparations and stability of bilberry and black currant extracts in milk products. J of Food Sci. 2004;69(9):S351–S356. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2621.2004.tb09948.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stintzing FC, Carle R. Functional properties of anthocyanins and betalains in plants, food, and in human nutrition. Trends in Food Sci & Tech. 2004;15(1):19–38. doi: 10.1016/j.tifs.2003.07.004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Stintzing FC, Stintzing AS, Carle R, Frei B, Wrolstad RE. Color and antioxidant properties of cyanidin-based anthocyanin pigments. J of Agri and Food Chem. 2002;50(21):6172–6181. doi: 10.1021/jf0204811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viljanen K, Kylli P, Kivikari R, Heinonen M. Inhibition of protein and lipid oxidation in liposomes by berry phenolics. J of Agri and Food Chem. 2004;52(24):7419–7424. doi: 10.1021/jf049198n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallace TC, Giusti MM. Determination of color, pigment, and phenolic stability in yogurt systems colored with non-acylated anthocyanins from Berberis boliviana L. as compared to other natural/synthetic colorants. J of Food Sci. 2008;73(4):C241–C248. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3841.2008.00706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]