Abstract

Background

Despite their integral role, Home Health Aides (HHAs) are largely unrecognized as essential to implementing effective infection prevention and control practices in the home healthcare setting. We sought to understand the infection prevention and control needs and challenges associated with caring for patients during the pandemic from the perspective of HHAs.

Methods

From June to August 2020, data were collected from HHAs in the New York metropolitan area using semi-structured qualitative interviews by telephone; 12 HHAs were interviewed in Spanish. Audio-recorded interviews were transcribed, translated and analyzed using conventional content analysis.

Results

In total, 25 HHAs employed by 4 unique home care agencies participated. HHAs had a mean age of 49.8 (± 9.1), 24 (97%) female, 11 (44%) Black, 12 (48%) Hispanic. Three major themes related to the experience of HHA's working during the COVID-19 pandemic emerged: (1) all alone, (2) limited access to information and resources, and (3) dilemmas related to enhanced COVID-19 precautions. Hispanic HHAs with limited English proficiency faced additional difficulties related to communication.

Conclusions

We found that HHA communication with nursing staff, plays a key role in infection control efforts in home care. Efforts to manage COVID-19 in home care should include improving communication between HHAs and nursing staff.

Key words: COVID-19, Home health aides, Home healthcare, Language barriers, Infection, Prevention and control

The current pandemic of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has caused major strain on the UStates healthcare system, including home healthcare (HHC) agencies. HHC agencies faced numerous challenges during the early phase of the pandemic, including limited availability of personal protective equipment (PPE) and disinfectants necessary to ensure minimal risk of infection for staff caring for patients with COVID-19.1 Nurses, therapists, social workers, and home health aides (HHAs) make up the HHC workforce2; however, HHAs are unique because they spend considerable time with patients in their homes providing critical personal care services essential to support activities of daily living and to enable homebound older adults live in their homes and communities.3

Qualitative studies suggest that HHAs also perform health-related tasks, including reminding patients about clinical instructions and updating clinicians regarding changes in patients’ clinical status.4 Nevertheless, HHAs are largely unrecognized as part of the healthcare team and prior work suggests that communication between HHAs and other healthcare team members is limited.5 , 6 Indeed, amid the current pandemic, early work by Sterling and colleagues showed that HHC workers like HHAs provide frontline care, often at personal risk to support their patients.6 HHAs are overwhelmingly Black and/or Hispanic women,7 , 8 with lower educational attainment, earning near poverty wages.9 , 10 Many Hispanic HHAs speak Spanish and have limited English proficiency.11 This demographic profile represents a key segment of the HHC workforce which already experiences high levels of marginalization, and faced greater risk for COVID-19 given the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on Black and Hispanic communities.12, 13, 14 Developing strategies to better support this diverse direct care workforce is critical to meeting the needs of an increasingly diverse aging population in the United States.15 , 16

Despite the integral role of HHAs in the care of homebound patients, limited research attention has focused on exploring their experiences, particularly during the COVID-19 pandemic. Additionally, no study has focused on the experiences of Spanish-speaking HHAs with limited English proficiency during the pandemic. As the COVID-19 pandemic expedites existing trends to move long-term care patients from facilities to community-based care,17 better understanding of the challenges faced by HHAs is necessary to inform the development of improved practices and policies to better support this marginalized group. This qualitative study sought to understand the infection prevention and control needs and challenges associated with caring for patients during the pandemic from the perspective of HHAs employed by Licensed Home Care Service Agencies.

Methods

Study design and population

This study was part of a larger, qualitative study designed to describe the care planning process for HHC nurses and HHAs for patients with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. From June to August 2020, we conducted in-depth, semistructured interviews with HHAs. HHAs were eligible if they cared for HHC patients during the pandemic (from March 2020), spoke English or Spanish, worked in the agency for at least a year and had cared for patients with Alzheimer's disease and related dementias. HHAs were recruited from 4 agencies (2 private for-profit, 2 nonprofits; 3 in New York City, 1 in Westchester County). Recruitment efforts were conducted in English and Spanish and included flyers mailed to eligible participants by agency administrators, in addition to text messages. In addition, in one site, research staff screened 24 HHAs from the agency's employee list to confirm eligibility, with 10 agreeing to participate in the study. Participants were reimbursed a $20.00 e-gift card for interview completion. The study was approved by the Adelphi University's Institutional Review Board and informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Data collection

Interview guides that informed this substudy were developed from a review of the literature related to infection prevention and control, and informed by Donabedian's conceptual framework of health care quality.18, 19, 20, 21, 22 Donabedian's framework is applicable to understanding factors associated with health care environments (eg, HHC) and how they impact care processes and outcomes.22 Thus, participants were asked about the following areas related to infection prevention and control during the COVID-19 pandemic: (1) hand hygiene in the HHC environment, (2) utilization of COVID-19 related infection prevention information and its impact on the processes of care, and (3) barriers to the provision of care. Questions related to infection prevention and control in this sub-study included: (1) Tell me about challenges you have encountered in receiving COVID-19 infection prevention information, (2) I'd like you to list all the things that you can think of that make it difficult to take care of your patient with Alzheimer's/dementia since the COVID-19 outbreak, and (3) What, if any, barriers to practicing hand hygiene or infection prevention do you encounter in the patient's home environment?

Interviews were conducted via telephone and lasted 25 minutes, on average. Sociodemographic data including age, gender, and race were collected following the semistructured interview. Twelve HHAs were interviewed in Spanish. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim; transcripts in Spanish were subsequently translated to English by a medical interpreter. Interviewers (A.C. and Z.T.O.) debriefed after conducting 1 to 2 interviews to discuss emerging content, summarize material in analytic memos, and assess degree of data saturation to evaluate the need for additional interviews. Upon completion of 23 interviews, interviewers speculated whether a stage of “informational redundancy” was being reached,23 because new interviews were tending to repeat information previously collected on key topics.24 Completion of an additional 2 interviews solidified confidence that data saturation was reached and sampling was stopped.

Data analysis

Data analysis was conducted using a conventional content analysis approach that consists of coding and identifying patterns in the data to describe the experience of HHAs during the COVID-19 pandemic.25 After personal identifiers were removed, transcripts were entered in NVivo qualitative data analysis software (QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 10, 2012). Two members of the research team (J.O. and Z.T.O.) read half of the transcripts independently to further develop in-depth familiarity with the data, and to develop a preliminary codebook. Codes represented categories or concepts emerging from transcripts that served to label and group the data in meaningful ways (eg, communication about COVID-19, infection control in the home, and COVID-19 fears). To ensure the codes were grounded in the qualitative data, codes were systematically refined, eliminated or added through several iterations of transcript reviews and coding until a final codebook was established. Six transcripts were initially coded by each of the 2 coders who subsequently met to resolve coding discrepancies through consensus in order to maximize their consistency of applying codes. The remaining 19 transcripts were then coded by both coders. Finally, to generate themes and subthemes, all authors read coded excerpts, discussed emerging patterns, and collapsed and organized codes into broader topics and themes through iterative discussion.

Results

Sample characteristics

Participants (n = 25) were predominantly female (96 %), with a mean age of 49.8 (± 9.1) (Table 1 ). Participants largely identified as racial/ethnic minorities: 44% were Black and 56% were Hispanic. Thirty-six per cent of our participants had a high school degree or more. On average, participants had 8.6(± 7.3) years of experience working as HHAs. Spanish-speaking participants were specific to Agency 2 and 3.

Table 1.

Characteristics of participating agencies and HHAs

| Characteristic | (N=25) |

|---|---|

| HHA agencies (N = 4) | |

| Agency 1 (private for-profit) | 8 |

| Agency 2 (private for-profit) | 5 |

| Agency 3 (nonprofit) | 2 |

| Agency 4 (nonprofit) | 10 |

| Age | n (%) |

| Mean (SD) years | 49.8 (9.1) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 24 (96) |

| Male | 1 (4) |

| Race/ethnicity | |

| Black | 11 (44) |

| Hispanic | 14 (56) |

| Education level | |

| ≥ High school | 16 (64) |

| < High school | 9 (36) |

| Years of experience working as HHA | |

| Mean (SD) years | 8.6 (7.3) |

HHA, home health aide; SD, standard deviation.

Qualitative themes

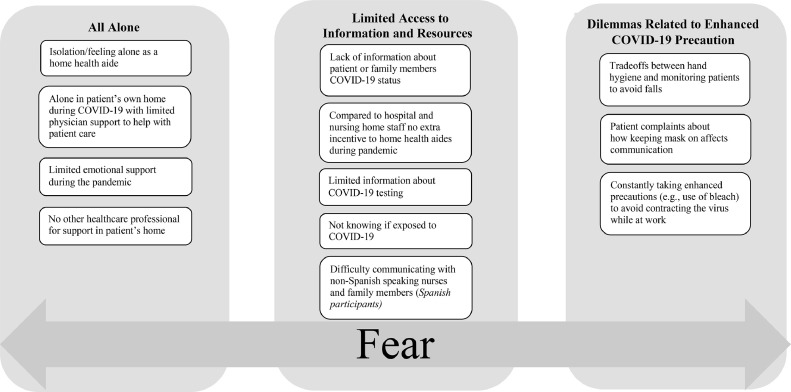

Analyses yielded 3 major themes related to the experience of HHA's working during the COVID-19 pandemic: (1) all alone, (2) limited access to information and resources, and (3) dilemmas related to enhanced COVID-19 precautions (Fig 1 ). Each of these themes had associated subthemes (Fig 1), which are described in detail below. Notably, all themes reflect circumstances wherein the HHAs lived in constant fear while working during the pandemic.

Fig 1.

Emerging themes.

Theme 1: All Alone. HHAs reported challenges they confronted because of the nature of the home healthcare practice environment, which confined them to work in solitude in their patient's home.

Working Alone and Feeling Isolated. —HHAs worked as the only staff in the patient's home for extensive periods, with shifts ranging from 4 to 12 hours. Working in such an environment required a lot of autonomy because there was no back-up staff in the patient's home. Most HHAs described how they felt isolated and undervalued in their job role as HHAs in general:

“This job of aide you pretty much...do it alone. And I don't speak for myself, I speak for all, because the nurses don't come to tell you instructions. They make you feel like you're not worth it, like you are not anything there…that's how I feel. That's the experience I have.” (Spanish- speaking HHA, nonprofit agency). Another English-speaking HHA added, “Nobody comes and says, this is what you are supposed to do, this is this or this is that. And I am not making reference to COVID, this has been going on for a while…so it is not to say it is the COVID time. It has been going on for a while.”

While HHAs reported the perception of working alone and isolation in a HHC setting in general, they emphasized that it was exacerbated during the pandemic:

“HHAs are facing the same issues as those in the hospital and nursing home but we are not given the same treatment… people don't mention HHA as first responders…remember you are alone in the home with the patient…” [English-speaking HHA, for-profit agency].

Another HHA noted the burden of working alone in a setting with no other members of the HHC team physically present: “Everything is on you, because the weight is on you. Because you alone are there with the patient.” [English-speaking HHA, for-profit agency]

Alone in patients’ homes with limited physical support to help with patient care. HHAs provided personal care to patients who had functional limitations. HHAs consistently stated that they had no other health care professional to rely on to help with difficult tasks in patients’ homes, which may require assistance in other settings, such as turning or positioning physically dependent patients. While providing such care, HHAs had fears related to COVID-19 exposure risk.

“It is difficult because you have to feed the client and take care of them…and certain interactions are hard, I try to stay away when I talk to them, but it does not work because some have vision impairment. Social distancing is absolutely impossible because they are completely dependent on you.” [English-speaking HHA, for-profit agency]

Another HHA from a for-profit agency explained:

“…You never know, you have your mask on, but the patient is in your face, remember the patient is bed bound and when you try to help them out of bed, they are in your face. It was the scariest thing…only by the grace of GOD…it is not a good experience.”

Limited emotional support during the pandemic. Working as a HHA during the pandemic posed substantial stressors, yet limited access to emotional support was frequently mentioned by most HHAs. To illustrate the lack of emotional support, participants compared their roles to non- HHC staff. Certified nursing assistants who have similar roles in hospitals and nursing homes benefitted from the opportunity to interact with other healthcare workers,26 potentially receiving emotional support from such interactions. HHAs highlighted that during the peak of the pandemic, they received limited emotional support from other members of the HHC team.

“People who work in nursing homes and hospitals are better. They have more support. We go through worse, there is no support. Because sometimes you need someone to talk to, because sometimes you are so burdened…now nurses don't visit patients often any more…” (English-speaking HHA, for-profit agency) One HHA from a not-for profit agency explained this further with respect to lack of support from other HHC staff: “There is no communication. The only communication is if something happened, and when you call they may call you back. Sometimes it takes a day or 2 or may be a week. It is you, the patient and maybe the patient's family.”

Availability of HHC staff nurses was seen as important in establishing a positive relationship with the HHAs needed for emotional support. Some HHAs shared how the use of telephone calls can be used to enhance proactive communication with HHAs and leveraged to provide them emotional support:

Another HHA from a for-profit agency stated. “The nurse should take care of the HHA, make sure we are taking care of ourselves…little, small details of self-care with the COVID situation…”

Theme 2: Limited Access to Information and Resources. Limited access to information and resources was reflective of the limited organizational support HHAs encountered related to infection control during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Lack of information about patient/family member or other HHAs COVID-19 status. HHAs indicated that they wanted to know if their patient or patient's family had tested positive for COVID-19 but emphasized that this information was not available. They also expressed concern regarding the lack of information about the COVID-19 status of other HHA colleagues who also care for their patient and how this might put them at risk for exposure to COVID-19. A HHA from a for-profit agency explained:

“It's difficult because no one test the family and friends of the patient, no one is testing the patient. You don't know what the patient has going in, but you have to be in there day in, day out. You don't know if the patient even has contracted COVID-19. Nobody is testing them.”

Another HHA said: “I am with a patient, and she has all this different aide coming in and out. No one tells you if an HHA had COVID, I do not know if my patient had it.…”

Not knowing own COVID-19 status and limited information about COVID-19 testing for HHAs. In addition to uncertainty regarding the COVID-19 status of others, HHAs worked with a fear of not knowing their own COVID-19 status because they had not been tested:

“It was like hell going to work every day. It is difficult, because every day, you are thinking, and you want to know if you have contracting something. It was a torment.” HHAs expressed frustration with the limited information they received from HHC nurses or their agency about getting tested: “… they remind you every day ‘if you feel sick, don't go to work.’ If you are at work, you can call the head nurse, all she would say is ‘check temperature, if you're sick stay home.” (English-speaking HHA, non-for-profit agency) Another HHA from a for-profit agency stated, “Nobody is there checking on you or giving you information about test.”

A HHA from a for-profit agency recommended that HHC agencies develop clear processes that would facilitate staff access to testing.

“The only thing I would have really wanted them to do, is to have really provided us some way for us to get tested… because just like they got us an appointment for us to get fitted for the N95 mask. I wish they could have done the same thing to get us tested.”

While HHAs expressed concerns about lack of access to testing, many HHAs appreciated the daily screening COVID-19 which their agencies conducted via telephone. One Spanish-speaking HHA from a non-for-profit agency stated: “No difficulties because the company is well organized, we have cellular communication, apps. Daily, we get tips and techniques on how to stay safe and keep the patient safe. There is a lot we can do. It's sent to us via internet, and we can take care of ourselves better.” One HHA (English-speaking) from a for profit agency emphasized: “Every morning there is a recording, with the agency, wash your hands, wear a mask… blabla bla that's all the information we get. Wash your hands, remember to wear a mask when you're in the presence of the patient. Nothing about the patient. All of us get it. As soon as you clock in that's what you get.”

Limited Access to PPE and Hand hygiene products. Many HHAs experienced challenges with having an adequate supply of PPE during the pandemic. Some noted structural barriers related to the HHC office being closed when their shifts end, making it hard to get access to supplies. One HHA from a nonprofit agency stated:

“A mask alone is not enough protection to me when I have to be in that home every day. A mask is not supposed to be worn more than 8 hours a day, and you are not given enough. During the weekend, if you don't go, you don't get it. You have to go to the office to pick it up. If you work 9-5, and the office closes at 5 pm, when you close from the case, the office is closed. How are you going to get to the office before you go to work? They are not mailing supplies after COVID, you have to go in and get it.”

Further exacerbating this challenge was the limited availability of adequate hand hygiene products in patients’ homes, as a HHA from a nonprofit agency stated: “[The patient] has a lot of hand bar soap. So, I spoke to the wife, and I told her to please get us hand washing soap like a pump.” While many participants verbalized acceptance of the HHC process, which, as noted, generally requires HHC staff to travel to a central office location to pick up supplies (eg, PPE), HHAs suggested that nurses could help facilitate access to PPE: “The nurse should take care of the HHA … ensure that we are not running low.” (for-profit agency)

More expenses, no extra incentives. HHAs shared that health care employees on the frontline in hospitals and nursing homes received financial incentives or bonuses during the COVID-19 pandemic. In contrast, HHAs noted that they incurred extra financial expenses and received no incentives during the pandemic. One HHA described the extra costs associated with purchasing PPE and hand washing supplies, given the limited access from agencies’ and in patients’ homes, as noted above: “I buy all my supplies, my soap, and everything because I have to protect myself even though it is expensive. I don't want to bring these things back to my house.” Despite the increased personal costs, another participant emphasized how no reimbursements or financial incentives were made available: “We went through so much during COVID-19, there was no relief, nothing at all …. CNAs in the hospital or nursing home, they got special pay for COVID-19… we did not get that.”

Difficulty communicating with non-Spanish-speaking nurses and family members (Spanish-speaking Participants). Among Spanish-speaking participants, gaining access to COVID-19 related information necessary to facilitate patient care was a challenge. Spanish-speaking HHAs preferred working with Spanish-speaking patients: “Don't send me where I can't communicate. The first thing I have to do is communicate with that person.” Another HHA expressed how language posed a barrier to effective communication with non-Spanish-speaking HHC nurses: “almost always, the nurses who arrive speak English, do not speak Spanish. And I don't speak much English, very little.” Other HHAs recommended that COVID-19 trainings, teaching material, and other information should be provided in English and Spanish: “I consider that they should have a bilingual person. Give training to bilingual person and to people who do not speak the language, explain it in English and Spanish.” Another HHA similarly emphasized, “it would be good if the agencies had the same thing that the hospital has, which gives you (COVID-19) information in Spanish and English.”

Because of limited English proficiency, Spanish-speaking HHAs had to locate resources to facilitate communication with patients, families and the health care team, and to understand COVID-19 related information. Many Spanish-speaking HHAs thus relied on their family members to translate care plans or clinical information: “When they send it to me in English, I send it to my daughter. My daughter explains it to me. I was once sent an English case from the same agency.” HHAs indicated a need for more resources to facilitate communication. When asked if being a Spanish-speaking HHA impacts a HHAs job role, another HHA explained:

“Of course, it does. To understand a plan of care, it would be good if we were given Hispanic people because who could do it in Spanish. As a Spanish-speaking person you're going into a house, the care plan is in English, and you won't be able to read it.”

Theme 3. Dilemmas related to enhanced COVID-19 precautions. Participants described constantly trying to balance the risk of working as HHAs and their own health.

Tradeoffs between hand hygiene and monitoring patients to avoid falls. HHAs placed high priority on keeping patients safe at home and free from falls. This effort frequently compromised their ability to maintain hand hygiene practices, thus increasing potential COVID-19 risk. One HHA, from a non-for profit agency explained how this dilemma manifests while caring for her patient with unsteady gait:

“You can't even get up and go to the bathroom. Most of the time, they don't stay put and they are not steady on their feet, so most of the time you have to be with them. You have to be there with the walker because they will not stay put…you can't even leave to go to the bathroom to wash your hands because she's going to get up and she's going to fall.”

Maintaining mask-wearing amidst patient complaints about its impact on communication. Many HHAs described the unique challenge to keep their masks on in patients’ homes and the conflict with patient satisfaction. Mask wearing made it difficult for patients with hearing impairments to fully understand HHAs when speaking. As a result, HHAs reported being caught between maintaining infection prevention practices at the risk of achieving high patient satisfaction—a factor critical to being retained as a HHA with patients. One HHA from a for profit agency stated.

“I keep my mask on 99% of the time…She asks me about my mask and says she doesn't understand what I am saying, I should take it off. I explain and explain why I wear my mask.… but she doesn't like the mask and I tell her it is necessary. If I have to speak clearly, I remove it off my mouth and then put it back. She doesn't like the mask. It is a challenge.”

HHAs also feared that their vulnerability to COVID-19 was greater because patients sometimes did not adhere to wearing masks: “Patients remove masks, they touch everything. They sit outside. They don't wash hands at home…” (HHA from for profit agency)

Constantly taking enhanced precautions (eg, use of bleach) to avoid contracting the virus exacerbated PPE shortages. HHAs discussed how enhanced infection practices during the COVID-19 pandemic even more rapidly depleted the already limited supplies available:

“We have more burden to change gloves, washing hand…” Another HHA described increased reliance on the use of bleach and disinfectants to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 in the patient's home during her shift: “When I start, I spray the air, bleach the area. I re-clean everything once I start a case. COVID has made me rethink how I do things…. I bleach the kitchen, bathroom. I am a bleach user.” (HHA from for profit agency)

Another HHA from a for profit agency described extensive increased use of Lysol and alcohol for infection control:

“Because when he sneezes it spreads…. I back off, I Lysol the area, get alcohol to kill the germ when he sneezes. Then I have to clean the table, I have to throw away the food. Clean everything up with alcohol. Then I clean his hands and brush his teeth. I have to clean the germs because I am breathing the air he is breathing in the apartment.”

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first study to describe the experiences of English and Spanish-speaking HHAs working during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our findings suggest that as HHAs worked in a patient's own home environment in isolation from the rest of the healthcare team, they often had limited access to information and resources, encountered various dilemmas related to COVID-19 precautions, and worked amid constant fear during the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings suggest that infection prevention and control during the pandemic relied on effective communication processes, particularly between the nurse and HHAs. Overall, HHAs offered valuable insights which were consistent with prior qualitative work exploring the experiences of HHAs.6 , 27

In particular, our results were similar to a recent qualitative study where Sterling and colleagues examined HHC workers’ experiences of caring for older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Sterling et al. described difficulties owing to shortage of PPE, risk of contracting COVID-19 from public transportation, transmission to their patients and families, and lack of emotional support and recognition for their role as essential workers.6 However, in our study, an additional theme of dilemmas related to enhanced COVID-19 precautions emerged, and for Spanish-speaking participants, difficulty communicating with non-Spanish-speaking nurses and family members.

Prior studies have found that, even before the pandemic, HHAs experienced difficulties communicating with the HHC team, including nurses. 5 , 6 , 27 , 28 Consistent with our study, previous research prior to the pandemic suggests that HHAs have limited interactions with nurses or other members of the healthcare team.3 , 27 These limited interactions placed additional strain on HHAs during the pandemic, as this had an impact on their limited access to information or resources to deliver patient care and their emotional wellbeing.

HHAs emphasized a need for more ongoing contact with supervisors and nurses, including via telephone for COVID-19 related guidance and emotional support. HHAs felt supported if nurses called to check on them to ask if they had adequate PPE or find out how they were navigating COVID-19 precautions in patients’ homes. Our findings suggest that additional efforts to expand nurse-HHA communication are clearly needed to support HHA emotional well-being and preparedness both during and post-pandemic. HHA supervisory visits by nurses, as mandated by the Department of Health,29 offer an important opportunity to connect and engage HHAs in training and education about infection prevention guidelines related to COVID-19 in addition to providing feedback from nurses. Of note, during the pandemic, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services issued waivers for supervision of HHAs,28 these waivers removed the requirement for in person HHA supervision by home care nurses and may have led to a reduced the presence of home care nurses highlighted by our participants. Most HHAs in our study expressed favorable attitudes to receipt of daily screening of COVID-19 symptoms via text messaging systems. Such technology can be leveraged to augment trainings, supervise HHAs, and monitor availability of PPE for HHAs.

When comparing interviews with English- and Spanish-speaking participants, we found a number of important differences. For example, English-speaking participants indicated much higher expectations for additional training and incentives relative to Spanish-speaking participants. In contrast, among Spanish-speaking participants, concerns appeared to be primarily linked to limited English proficiency and in part, led to limited effective communication with the healthcare team. Interviews conducted in English reflected more concerns related to better working conditions compared to interviews in Spanish. Although previous research has not explored how challenges HHAs experienced during the pandemic might differ according to language, our findings are similar to other studies that have identified language as a barrier to infection prevention and control among certified nursing assistants in the nursing home setting.30 Our findings suggest that language preference might be a particularly relevant factor in ensuring effective infection control practices among HHAs during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Challenges experienced by HHAs working during the pandemic were further exacerbated for Spanish-speaking HHAs in our study who navigated language barriers while working during the pandemic. These language barriers resulted in more work-related time spent navigating communication differences—further magnifying existing disparities among this group.31 Amid the pandemic, HHAs with limited English proficiency highlighted that they were assigned to patients who did not speak Spanish. During the pandemic, HHC agency leaders, similar to other health care leaders, were confronted with staffing and resource shortages to meet agency needs.12 Thus, Spanish-speaking HHAs may have been assigned to non-Spanish-speaking patients to ensure adequate patient coverage, exacerbating the need for interpreter services. HHAs in our study highlighted the need for enhanced access to medical interpreters as important to the provision of high-quality care. Participants in our study also highlighted difficulties associated with being assigned to a case with a non-Spanish-speaking nurse. Researchers have found that language concordance, even with co-workers (eg, HHA to nurse), is associated with job satisfaction and lower turnover among HHAs,7 lending support to the need to invest in building diverse HHC teams and interpreter services. The variety of resources HHAs used for interpretation also raise concerns about privacy of health information. Given that our interviews illustrated how iPADs, internet and cell phones were frequently utilized for work-related purposes, this technology may represent an additional avenue for agencies to ensure consistent access to medical interpreter services for Spanish-speaking HHAs and the HHC team.

The U.S Centers for Disease Prevention and Control (CDC) put forth a communication plan that recommends that employers communicate information about the pandemic in employees’ preferred languages and at their reading levels.32

As voiced by participants in our study, HHAs must navigate infection control issues similar to those in hospitals or nursing homes, but with even more limited access to a healthcare team or resources, in addition to being isolated in a patient's home environment. In our sample of HHA participants, we did not find any differences by agency ownership. Overall, HHAs are a marginalized workforce that endures physically demanding work and high levels of economic stress, exacerbated during the pandemic. Sterling and colleagues also found that home care workers expressed anxieties stemming from multiple stressors including limited economic resources.6 These findings are consistent with prior studies, even in nonpandemic times, that show that HHAs experience high levels of economic stress.33 , 34 Nevertheless, it is alarming that a significantly disadvantaged workforce, with very low income, had to incur additional expenses to pay for PPE to ensure their own occupational safety and protection from the virus. Further inequities exist as HHAs who faced greater risk during the pandemic are also more likely to live in poverty and experience work-related strain.13 , 33 Despite the integral role of HHAs to the aging population and long-term care system, the median wage for direct care is $12.27 per hour; at that wage, a full time HHA lives below the poverty line.10 , 35 Today, progress toward increasing the wages of HHAs is in sight with the American Rescue Plan Act of 2021, recently signed into law.36

Insights gained from our study suggest strategies to better support HHAs and guide infection prevention practices in HHC settings as the pandemic evolves, and even post-pandemic. First, it is clear that HHC administrators need to bridge the gap in communication between HHAs and nurses to enhance infection prevention and control practices during the pandemic. Most urgently, HHC administrators and infection control nurses need to build better workflows with HHA input to enhance communication. Second, clear, concise, and easily accessible knowledge must be disseminated to all HHAs with recognition of the language preference of employees with limited English proficiency. Related, with the growing Hispanic HHA workforce, including those with limited English proficiency,11 ongoing efforts are necessary to ensure access to interpreter services in the HHC setting. Third, because HHC staff generally need to travel to their central office location to get access to PPE, efforts to ensure access to PPE and home care supplies should consider on-going use of mailing systems to the homes of home care staff or patients—a strategy used during the early phase of the pandemic in one of our study agencies. Finally, as HHC providers move beyond the current crisis, future infection and control efforts in HHC agencies may consider expanding the use of information technology to facilitate communication between HHA and HHC staff (eg, nurses, supervisors, and coordinators).

Limitations

A number of study limitations need to be acknowledged. Recruitment relied on agency leadership reaching out to their teams, which may have limited who expressed interest in participating. Additionally, we interviewed HHAs who had experience working with patients with ADRD, which may not be representative of the general HHA population. We only interviewed HHAs and future studies should solicit the perspective of other stakeholders (eg, HHC nurses, nurse managers) to understand their role in infection prevention and how it intersects with the HHAs.

Conclusions

This study contributes to the understanding of experiences of both English- and Spanish-speaking HHAs, across 4 agencies in the New York metropolitan area serving a diverse patient population during the COVID-19 pandemic. We found that the pandemic further exacerbated HHAs sense of being alone, PPE and information shortages, financial stress, and feelings of being undervalued, while triggering new dilemmas in patient care, which all contributed to working in a state of fear and anxiety. We also found that communication with nursing staff - broadly defined - plays a key role in infection prevention and control efforts in HHC. The use of information technologies, specifically phone text messaging was a valued and accepted strategy for screening of COVID-19 symptoms among our HHA participants. This study has affirmed the relevance of further exploring infection prevention structures and processes focused on the HHA workforce, particularly amid the current pandemic.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: None to report.

References

- 1.Shang J, Chastain AM, Perera UGE. COVID-19 preparedness in US home health care agencies. J Am Med Dir Assoc. 2020;21:924–927. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2020.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Landers S, Madigan E, Leff B. The future of home health care: a strategic framework for optimizing value. Home Health Care Manage Pract. 2016;28:262–278. doi: 10.1177/1084822316666368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stone RI, Bryant NS. The future of the home care workforce: training and supporting aides as members of home-based care teams. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2019;67(S2):S444–S448. doi: 10.1111/jgs.15846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reckrey JM, Tsui EK, Morrison RS. Beyond functional support: the range of health-related tasks performed in the home by paid caregivers in New York. Health Affairs. 2019;38:927–933. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Franzosa E, Tsui EK, Baron S. Who's caring for us?”: understanding and addressing the effects of emotional labor on home health aides’ well-being. Gerontologist. 2019;59:1055–1064. doi: 10.1093/geront/gny099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sterling MR, Tseng E, Poon A. Experiences of home health care workers in New York City during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic: a qualitative analysis. JAMA Intern. Med. 2020;180:1453–1459. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Weng SS, Landes SD. Culture and language discordance in the workplace: evidence from the national home health aide survey. Gerontologist. 2017;57:900–909. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartmann H, Hayes J. The growing need for home care workers: Improving a low-paid, female-dominated occupation and the conditions of its immigrant workers. Public Policy Aging Report. 2017;27:88–95. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stone R, Wilhelm J, Bishop CE, Bryant NS, Hermer L, Squillace MR. Predictors of intent to leave the job among home health workers: analysis of the national home health aide survey. Gerontologist. 2017;57:890–899. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnw075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.PHI. (2019). Workforce data center. Available at: https://phinational.org/policyresearch/workforce-data-center/. Accessed July 30, 2021.

- 11.Campbell S. Racial disparities in the direct care workforce: spotlight on hispanic/Latino workers. Research Brief, February New York: Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute.2018. Available at: https://phinational.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Latino-Direct-Care-Workers-PHI-2018.pdf. Accessed July 30, 2021.

- 12.Sama SR, Quinn MM, Galligan CJ. Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on home health and home care agency managers, clients, and aides: a cross-sectional survey, March to June, 2020. Home Health Care Manage Pract. 2021;33:125–129. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shippee TP, Akosionu O, Ng W. COVID-19 pandemic: exacerbating racial/ethnic disparities in long-term services and supports. J Aging Soc Policy. 2020;32:323–333. doi: 10.1080/08959420.2020.1772004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hooper MW, Nápoles AM, Pérez-Stable EJ. COVID-19 and racial/ethnic disparities. JAMA. 2020;323:2466–2467. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.8598. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Durán R. The changing US Latinx immigrant population: demographic trends with implications for employment, schooling, and population Integration. Ethn Racial Stud. 2020;43:218–232. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scales K. It is time to resolve the direct care workforce crisis in long-term care. Gerontologist. 2021;61:497–504. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inzitari M, Risco E, Cesari M. Editorial: nursing homes and long term care after COVID-19: a new era? J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;24:1042–1046. doi: 10.1007/s12603-020-1447-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Carter EJ, Greendyke WG, Furuya EY. Exploring the nurses' role in antibiotic stewardship: a multisite qualitative study of nurses and infection preventionists. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46:492–497. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2017.12.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uchida M, Stone PW, Conway LJ, Pogorzelska M, Larson EL, Raveis VH. Exploring infection prevention: policy implications from a qualitative study. Policy Politics Nurs Pract. 2011;12:82–89. doi: 10.1177/1527154411417721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Russell D, Dowding DW, McDonald MV. Factors for compliance with infection control practices in home healthcare: findings from a survey of nurses' knowledge and attitudes toward infection control. Am J Infect Control. 2018;46:1211–1217. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2018.05.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kagan LJ, Aiello AE, Larson E. The role of the home environment in the transmission of infectious diseases. J Community Health. 2002;27:247–267. doi: 10.1023/A:1016378226861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Donabedian A. The quality of care: how can it be assessed? JAMA. 1988;260:1743–1748. doi: 10.1001/jama.260.12.1743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sandelowski M, Given LM. The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications. Available at: https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/the-sage-encyclopedia-of-qualitative-research-methods/book229805. Accessed October 13, 2021

- 24.Saunders B, Sim J, Kingstone T. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Qual Quant. 2018;52:1893–1907. doi: 10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hsieh H-F, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15:1277–1288. doi: 10.1177/1049732305276687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Travers JL, Schroeder K, Norful AA, Aliyu S. The influence of empowered work environments on the psychological experiences of nursing assistants during COVID-19: a qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2020;19:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12912-020-00489-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Franzosa E, Tsui EK, Baron S. Home health aides' perceptions of quality care: goals, challenges, and implications for a rapidly changing industry. New Solutions: A journal of environmental and occupational health policy. 2018;27:629–647. doi: 10.1177/1048291117740818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sterling MR, Silva AF, Leung PB. “It's like they forget that the word ‘health'Is in ‘home health aide’”: understanding the perspectives of home care workers who care for adults with heart failure. J Am Heart Assoc. 2018;7 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.118.010134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.NYS Department of Health Report. Guidelines for the Provision of Personal Care Services in Medicaid Managed Care. New York, NY: NYS Department of Health. Available at: https://www.health.ny.gov/health_care/medicaid/redesign/docs/final_personal_care_guidelines.pdf. Accessed March 28, 2021.

- 30.Travers J, Herzig CT, Pogorzelska-Maziarz M. Perceived barriers to infection prevention and control for nursing home certified nursing assistants: a qualitative study. Geriatr Nurs. 2015;36:355–360. doi: 10.1016/j.gerinurse.2015.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Muench U, Spetz J, Jura M, Harrington C. Racial disparities in financial security, work and leisure activities, and quality of life among the direct care workforce. Gerontologist. 2021;61:838–850. doi: 10.1093/geront/gnaa190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2020). COVID-19 Communication Plan for Select Non-healthcare Critical Infrastructure Employers. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/communication-plan.html. Accessed December 28, 2020

- 33.Denton M, Zeytinoglu IU, Davies S, Lian J. Job stress and job dissatisfaction of home care workers in the context of health care restructuring. Int J Health Serv. 2002;32:327–357. doi: 10.2190/VYN8-6NKY-RKUM-L0XW. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shotwell JL, Wool E, Kozikowski A. “We just get paid for 12 hours a day, but we work 24”: home health aide restrictions and work related stress. BMC Health Serv Res. 2019;19:1–6. doi: 10.1186/s12913-019-4664-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Office of the assistant secretary for planning and evaluation. 2020 Poverty guidelines. Available at: https://aspe.hhs.gov/topics/poverty-economic-mobility/poverty-guidelines/prior-hhs-poverty-guidelines-federal-register-references/2020-poverty-guidelines

- 36.Cooper LA, Sharfstein JM, Thornton RL. What the American rescue plan means for health equity. JAMA Forum. Available at: https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama-health-forum/fullarticle/2778283. Accessed October 13, 2021 [DOI] [PubMed]