Abstract

The development of near-infrared-II (NIR-II) fluorescence imaging has implemented real-time detection of biological cells, tissues and body, monitoring the disease processes and even enabling the direct conduct of surgical procedures. NIR-II fluorescence imaging provides better imaging contrast and penetration depth, benefiting from the reducing photon scattering, light absorption and autofluorescence. The majority of current NIR-II fluorophores suffer from uncontrollable emission wavelength and low quantum yields issues, impeding the clinical translation of NIR-II bioimaging. By lengthening the polymethine chain, tailoring heterocyclic modification and conjugating electron-donating groups, cyanine dyes have been proved to be ideal NIR-II fluorophores with both tunable emission and brightness. However, a simpler and faster method for synthesizing NIR-II dyes with longer wavelengths and better stability still needs to be explored. This minireview will outline the recent progress of cyanine dyes with NIR-II emission, particularly emphasizing their pharmacokinetic enhancement and potential clinical translation.

Keywords: near-infrared-II, cyanine/polymethine dyes, multiplexed channels, molecular imaging, pharmacokinetics

Introduction

Near infrared fluorescence imaging technology is widely used in tracking biological processes and disease diagnosis due to its non-invasive, real-time and multi-dimensional monitoring characteristics. Indocyanine green (ICG) and methylene blue (MB) has been approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for clinical using, such as angiography or directing cancer surgery (Chen et al., 2019). Contrast to the NIR-I (700–1,000 nm) region, the NIR-II (1,000–1,700 nm) region has higher tissue penetration depth and imaging contrast for mammalian bioimaging (Frangioni, 2003), resulting from the reducing photon scattering, light absorption and tissue autofluorescence (Hong et al., 2017). Initially, some inorganic materials were developed for NIR-II imaging, given the examples like carbon nanotubes (Welsher et al., 2009), quantum dots (Bruns et al., 2017; Li et al., 2015), rare Earth doped nanoparticles (Fan et al., 2018; Naczynski et al., 2013; Zhong et al., 2017) or gold nanocluster (Liu et al., 2019; Zhu et al., 2018a). These materials usually have relatively high quantum yield and tunable emission wavelengths, which is particularly advantageous for vessel (Hong et al., 2014), liver or kidney (Loynachan et al., 2019) imaging. However, the long-term retention and unconfirmed biotoxicity limit their clinical translation (Zhang et al., 2013).

Researchers then refocused on organic dyes with good biocompatibility and fast excretion post-imaging. A variety of NIR-II dyes have been synthesized, such as donor-acceptor-donor (D-A-D) (Antaris et al., 2016) and cyanine fluorophores. D-A-D molecules have relatively low extinction coefficient and moderate quantum yield in nonpolar organic solvent, while they are easily quenched by water and thus lower the quantum yield in water (Yang et al., 2017). The introduction of shielding groups can partly reduce the intermolecular interaction caused by excessive conjugated system, thus improving the fluorescent brightness (Yang et al., 2018; Zhang et al., 2016). Compared with the D-A-D structures, the cyanine dyes have higher absorption coefficient and moderate quantum yield (Ding et al., 2019). Typically, cyanine dyes consist of two heterocyclic end groups connected by a polymethine chain with tunable lengths (Bricks et al., 2015). The π-conjugate strength can be enhanced by lengthening the polymethine chain or modifying heterocycle, effectively promoting the emission wavelength of cyanine dyes over 1,000 nm, such as IR-26, IR-1061, IR-1080 and Flav7 (Casalboni et al., 2003; Cosco et al., 2017; Li et al., 2018). However, there are still critical issues in developing a NIR-II dye for clinical trials, due to poor molecular stability and short circulation time.

In this Minireview, we summarized commercial NIR-II cyanine dyes with both NIR-II peak and off-peak emission (Antaris et al., 2017; Carr et al., 2018; Zhu et al., 2018a). Meanwhile, we describe recent developments in the synthesis of NIR-II cyanine derivatives, and outline the progress of the pharmacokinetics improvement and in vivo imaging applications of cyanine dyes.

Synthesis of Near-Infrared-II Cyanine/Polymethine Dyes

Commercial Cyanine Dyes With Both Peak and Tail NIR-II Emission

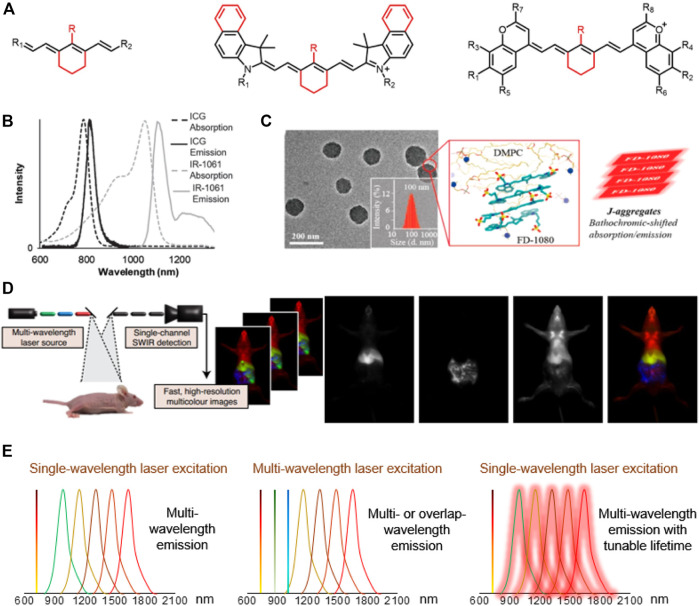

Small molecules with NIR-II emission have been synthesized and commercialized for years (Bricks et al., 2015), such as IR-26, IR-1061, IR-783 (Figure 1A). Some of them have been further expanded for imaging in vivo. A case in point is IR-1061, which was sequentially wrapped by polyacrylic acid (PAA) and DSPE-mPEG to form a stable nanocomplex in aqueous solution (Tao et al., 2013). The IR-1061 nanocomplex provided high-resolution vessel imaging in the 1,300–1,700 nm sub-NIR-II window, with a minimally discernible blood vessel width ∼150 μm. NIR-I dyes (ICG and IRDye800CW) spectroscopic mischaracterization on silicon detectors with insufficient NIR sensitivity falsely recorded their emission properties (Figure 1B). Recently, detecting on InGaAs camera have recovered the real emission spectrum of NIR-I-peak dyes. It has been found that most of NIR-I dyes have detectable NIR-II fluorescence (tail emission), and their NIR-II fluorescence intensity is even higher than that of some NIR-II peak emission dyes (Antaris et al., 2017; Zhu et al., 2018a). Highlighting the importance of NIR-II imaging with bright NIR-I-peak dyes that will fundamentally alter both clinical fluorescent imaging systems and current NIR-II dye synthetic strategies (Zhu et al., 2018b).

FIGURE 1.

The development of NIR-II cyanine dyes for improving biological bioimaging, disease diagnosis and navigation surgery. (A) Core structures of NIR-I/II cyanine dyes. (B) Absorption and emission spectra of ICG and IR-1061 (in acetonitrile). Reproduced with permission from (Yeroslaysky et al., 2019). (C) TEM images, DLS, molecular dynamics simulation (red frame), and schematic diagram of FD-1080J-aggregates. Reproduced with permission from (Sun et al., 2019) Copyright 2019 ACS publications. (D) Multicolor imaging in mice using ICG, MeOFlav7 and JuloFlav7. Reproduced with permission from (Cosco et al., 2020) Copyright 2020 Springer Nature Publishing Group. (E) The diagram of multichannel biological imaging through multi-wavelength emission and tunable lifetime.

Current Synthesis Strategies for NIR-II Peak Emission of Cyanine Dyes

Researchers have taken large efforts to design and synthesize NIR-II fluorophores with long wavelength, high quantum efficiency, good biocompatibility and optical/physiological stability, producing novel cyanine dye structures with improved optical properties (Figure 1A; Table 1). Zhang’s group designed a set of fluorophores with tunable wavelength emission named CXs by changing the number of methylene groups (Lei et al., 2019). Compared with commercial IR-26, CXs has better water solubility and optical stability. By increasing the quantity of methylene groups, the peak emission shifted from CX-1 at 920 nm, CX-2 at 1,032 nm to CX-3 at 1,140 nm. Inspired by IR-26 structure, Sletten’s group replaced the sulfur heteroatom in thiaflavylium to oxygen to enhance the fluorescence intensity (Cosco et al., 2017). The electron-donating dimethylamino group was added to compensate the conjugated system to ensure long-wave absorption/emission. They eventually synthesized a series of cyanine dyes by linking two dimethylamino flavylium heterocycles with a polymethylene chain (Flav7). They further found that the steric hindrance of substituents would affect the π-conjugation strength, so that the emission wavelength of Flav7 adjusted ∼80 nm through changing the position of the substituents (Pengshung et al., 2020). Zhang’s group also synthesized a NIR-II FD-1080 dye which can be excited at 1,064 nm (Li et al., 2018). Adding a cyclohexene group in the middle of the methylene chain effectively increased the stability of FD-1080. The water solubility of FD-1080 was significantly increased by introducing sulfonic acid groups on the heterocyclic ring and the quantum yield of FD-1080-FBS complex can be increased from 0.31 to 5.94%. In addition, the FD-1080J-aggregate was achieved through self-assembly with 1, 2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine (Figure 1C) (Sun et al., 2019). J-aggregate of FD-1080 has pushed the emission peaks to 1,370 nm, affording even clearer imaging contrast for vasculature visualization. With the benefit of FD-1080-J-aggregates labelled mesoporous implant, the researchers fabricated the MSTP-FDJ@PAA to guide osteosynthesis with minuscule invasion, high resolution, and real-time surgical navigation in the NIR-II bioimaging window (Sun et al., 2021). However, the lack of cyanine dyes with peak emission over 1,500 nm and precisely tunable-emission wavelength has unfortunately limited NIR-II imaging exploration.

TABLE 1.

Typically reported peak-emission NIR-II fluorophores.

| λabs/λem | QY [%] | solvent | εφ[M−1cm−1] | Properties | Refs | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FD 1080 | 1,043/1,089 | 0.44 | DMSO | 196 | Water-soluble | Li et al. (2018) |

| Flav 7 | 1,026/1,045 | 0.53 | DCM | 1,250 | Water-soluble by micelles | Cosco et al. (2017) |

| CX 3 | 1,089/1,135 | 0.082 | DMSO | 7 | Water-soluble | Lei et al. (2019) |

| BTC 1070 | 1,012/1,066 | 0.04 | DMSO | 31 | Water-soluble by micelles | Wang et al. (2019) |

| BTC 982 | 948/986 | 1.26 | DMSO | 2,520 | Water-soluble by micelles | Wang et al. (2019) |

| LZ 1055 | 1,058/1,100 | 3.89 | DMSO | 5,700 | Water-soluble | Li et al. (2020) |

| IR 1061 | 1,061/1,100 | 0.59 | DCM | 1,400 | Water-soluble by micelles | Tao et al. (2013) |

The Enhancement of NIR-II Brightness

Generally, the quantum yield of a single NIR-II fluorescent molecule, owing to the small HOMO\LUMO energy gap and excessively large conjugated system lead to low structural rigidity (Lei et al., 2021), is relatively low. The intramolecular twist (Lei et al., 2021), the interaction between molecules or the interaction between molecules and water will also reduce the brightness in biological conditions. Therefore, researchers sought to increase the intermolecular distance by increasing the steric hindrance between molecules to increase the quantum yield of NIR-II dyes (Li et al., 2018). The Forster resonance energy transfer (FRET) effect between CXs can effectively enhance the brightness of CX-3, thereby realizing the response to biomarker of drug-induced hepatotoxicity OONO− (Lei et al., 2019). The complex formed by the protein (albumin) and the dye (NIR-I-peak cyanine) can also effectively increase the brightness by restricting the intramolecular rotation of the fluorophore (Tian et al., 2019). Besides, recent academic publication has shown that in addition to the length of the polymethine chain, substituents affect the brightness of cyanine dyes (Cosco et al., 2017; Cosco et al., 2020; Lei et al., 2019; Pengshung et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2019). For example, Sletten’s group found choosing substituents with fewer vibration modes could significantly increase the fluorescence quantum yield of the dye, which is attributed to the reduction of non-radiative energy dissipation (Cosco et al., 2021).

Pharmacokinetics Improvement and In Vivo Imaging of NIR-II Cyanine Dyes

Although NIR-II dye have not been approved for clinical use, small animal experiments have repeatedly shown that NIR-II-peak dyes and NIR-I-peak dyes with NIR-II tail emission has commendable performance including real-time vascular imaging and tumor recognition. To address the short-blood-circulation issue of current NIR-I-peak dyes, bovine serum albumin (BSA) was used to self-assemble with cyanine dyes (e.g., IR-783) into IR-783@BSA complex, which efficiently prolonged NIR-I/II bioimaging window (Tian et al., 2019). A NIR-II-peak dye (LZ-1105) was also developed to specifically bond with fibrinogen, providing the long blood circulation time for real-time angiography (Li et al., 2020). In addition, an anti-quenched fluorophore BTC1070 was synthesized with response to pH through the process of nitrogen protonation/deprotonation, realizing non-invasive and accurate ratiometric imaging of gastric pH in vivo (Wang et al., 2019). Sletten’s group further rationally changed the substituents of Flav7 to screen two dyes MeOFlav7 and JuloFlav7, which can match the 980 and 1,064 nm commercial lasers, respectively. By coupling with ICG as the third channel, they finally achieved three-color, high-speed and real-time bioimaging (Figure 1D,E) (Cosco et al., 2020). With the added companion of chromenylium dyes to flavylium dyes, they performed the four-channel bioimaging (ICG, JuloChrom5, Chrom7 and JuloFlav7) (Cosco et al., 2021).

Perspective and Challenges

NIR-II organic dyes are relatively facile to synthesize, easily modifiable, and have low biological toxicity, providing great potential for clinical translation. ICG and IRDye800CW are by far the most critical dyes to display NIR-II emission given their widespread use in modern medical imaging (Hu et al., 2020). In particular, the cyanine NIR-II fluorophore can effectively optimize its spectroscopic properties by changing the methylene groups and heterocyclic donor, thus overcoming the color-barrier for multichannel biological imaging and improving bioimaging quality to the longer NIR-II wavelength regions (Zhu et al., 2019). In addition to improving the molecular structure, researchers also tried to increase the steric hindrance or designed FRET-based fluorescent probes, effectively increasing the emission wavelength and the quantum yield (Lei et al., 2019). Imaging in the longer NIR-II sub-window (i.e. 1,500–1,700 nm NIR-IIb) provides nealy “zero” background (reduced photon scattering/autofluorescence and water absorbance) and even better imaging quality, however, organic dyes with a maximum emission wavelength beyond 1,200 and/or 1,500 nm are still rare. This requires the design of a larger conjugated system, and a more optimized molecular structure of the dye molecules. All in all, strategies to improve the photophysical properties, pharmacokinetics and in vivo imaging of NIR-II cyanine dyes still remain to be explored.

Author Contributions

YD. wrote the manuscript. XL. and SZ. commented and revised the final version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The reviewer (LW) declared a past co-authorship with one of the authors (SZ) to the handling Editor.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Antaris A. L., Chen H., Cheng K., Sun Y., Hong G., Qu C., et al. (2016). A Small-Molecule Dye for NIR-II Imaging. Nat. Mater 15, 235–242. 10.1038/nmat4476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antaris A. L., Chen H., Diao S., Ma Z., Zhang Z., Zhu S., et al. (2017). A High Quantum Yield Molecule-Protein Complex Fluorophore for Near-Infrared II Imaging. Nat. Commun. 8, 15269. 10.1038/ncomms15269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricks J. L., Kachkovskii A. D., Slominskii Y. L., Gerasov A. O., Popov S. V. (2015). Molecular Design of Near Infrared Polymethine Dyes: A Review. Dyes Pigm. 121, 238–255. 10.1016/j.dyepig.2015.05.016 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bruns O. T., Bischof T. S., Harris D. K., Franke D., Shi Y., Riedemann L., et al. (2017). Next-generation In Vivo Optical Imaging with Short-Wave Infrared Quantum Dots. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 1, 0056. 10.1038/s41551-017-0056 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr J. A., Franke D., Caram J. R., Perkinson C. F., Saif M., Askoxylakis V., et al. (2018). Shortwave Infrared Fluorescence Imaging with the Clinically Approved Near-Infrared Dye Indocyanine green. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 115, 4465–4470. 10.1073/pnas.1718917115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casalboni M., De Matteis F., Prosposito P., Quatela A., Sarcinelli F. (2003). Fluorescence Efficiency of Four Infrared Polymethine Dyes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 373, 372–378. 10.1016/s0009-2614(03)00608-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen W., Cheng C.-A., Cosco E. D., Ramakrishnan S., Lingg J. G. P., Bruns O. T., et al. (2019). Shortwave Infrared Imaging with J-Aggregates Stabilized in Hollow Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 12475–12480. 10.1021/jacs.9b05195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosco E. D., Arús B. A., Spearman A. L., Atallah T. L., Lim I., Leland O. S., et al. (2021). Bright Chromenylium Polymethine Dyes Enable Fast, Four-Color In Vivo Imaging with Shortwave Infrared Detection. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 143, 6836–6846. 10.1021/jacs.0c11599 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosco E. D., Caram J. R., Bruns O. T., Franke D., Day R. A., Farr E. P., et al. (2017). Flavylium Polymethine Fluorophores for Near‐ and Shortwave Infrared Imaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 56, 13126–13129. 10.1002/anie.201706974 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cosco E. D., Spearman A. L., Ramakrishnan S., Lingg J. G. P., Saccomano M., Pengshung M., et al. (2020). Shortwave Infrared Polymethine Fluorophores Matched to Excitation Lasers Enable Non-invasive, Multicolour In Vivo Imaging in Real Time. Nat. Chem. 12, 1123–1130. 10.1038/s41557-020-00554-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding F., Fan Y., Sun Y., Zhang F. (2019). Beyond 1000 Nm Emission Wavelength: Recent Advances in Organic and Inorganic Emitters for Deep‐Tissue Molecular Imaging. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 8, 1900260. 10.1002/adhm.201900260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y., Wang P., Lu Y., Wang R., Zhou L., Zheng X., et al. (2018). Lifetime-engineered NIR-II Nanoparticles Unlock Multiplexed In Vivo Imaging. Nat. Nanotech 13, 941–946. 10.1038/s41565-018-0221-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frangioni J. (2003). In Vivo near-infrared Fluorescence Imaging. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 7, 626–634. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2003.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong G., Antaris A. L., Dai H. (2017). Near-infrared Fluorophores for Biomedical Imaging. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 1. 10.1038/s41551-016-0010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong G., Diao S., Chang J., Antaris A. L., Chen C., Zhang B., et al. (2014). Through-skull Fluorescence Imaging of the Brain in a New Near-Infrared Window. Nat. Photon 8, 723–730. 10.1038/nphoton.2014.166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu Z., Fang C., Li B., Zhang Z., Cao C., Cai M., et al. (2020). First-in-human Liver-Tumour Surgery Guided by Multispectral Fluorescence Imaging in the Visible and Near-Infrared-I/II Windows. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 4, 259–271. 10.1038/s41551-019-0494-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Z., Sun C., Pei P., Wang S., Li D., Zhang X., et al. (2019). Stable, Wavelength‐Tunable Fluorescent Dyes in the NIR‐II Region for In Vivo High‐Contrast Bioimaging and Multiplexed Biosensing. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 58, 8166–8171. 10.1002/anie.201904182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lei Z., Zhang F. (2021). Molecular Engineering of NIR‐II Fluorophores for Improved Biomedical Detection. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 60, 16294–16308. 10.1002/anie.202007040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Lu L., Zhao M., Lei Z., Zhang F. (2018). An Efficient 1064 Nm NIR-II Excitation Fluorescent Molecular Dye for Deep-Tissue High-Resolution Dynamic Bioimaging. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 57, 7483–7487. 10.1002/anie.201801226 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B., Zhao M., Feng L., Dou C., Ding S., Zhou G., et al. (2020). Organic NIR-II Molecule with Long Blood Half-Life for In Vivo Dynamic Vascular Imaging. Nat. Commun. 11, 3102. 10.1038/s41467-020-16924-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C., Li F., Zhang Y., Zhang W., Zhang X.-E., Wang Q. (2015). Real-Time Monitoring Surface Chemistry-dependent In Vivo Behaviors of Protein Nanocages via Encapsulating an NIR-II Ag2S Quantum Dot. ACS Nano 9, 12255–12263. 10.1021/acsnano.5b05503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H., Hong G., Luo Z., Chen J., Chang J., Gong M., et al. (2019). Atomic‐Precision Gold Clusters for NIR‐II Imaging. Adv. Mater. 31, 1901015. 10.1002/adma.201901015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loynachan C. N., Soleimany A. P., Dudani J. S., Lin Y., Najer A., Bekdemir A., et al. (2019). Renal Clearable Catalytic Gold Nanoclusters for In Vivo Disease Monitoring. Nat. Nanotechnol. 14, 883–890. 10.1038/s41565-019-0527-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naczynski D. J., Tan M. C., Zevon M., Wall B., Kohl J., Kulesa A., et al. (2013). Rare-earth-doped Biological Composites as In Vivo Shortwave Infrared Reporters. Nat. Commun. 4, 2199. 10.1038/ncomms3199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pengshung M., Li J., Mukadum F., Lopez S. A., Sletten E. M. (2020). Photophysical Tuning of Shortwave Infrared Flavylium Heptamethine Dyes via Substituent Placement. Org. Lett. 22, 6150–6154. 10.1021/acs.orglett.0c02213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C., Li B., Zhao M., Wang S., Lei Z., Lu L., et al. (2019). J-aggregates of Cyanine Dye for NIR-II In Vivo Dynamic Vascular Imaging beyond 1500 Nm. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 141, 19221–19225. 10.1021/jacs.9b10043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C., Sun X., Pei P., He H., Ming J., Liu X., et al. (2021). NIR‐II J‐Aggregates Labelled Mesoporous Implant for Imaging‐Guided Osteosynthesis with Minimal Invasion. Adv. Funct. Mater. 31, 2100656. 10.1002/adfm.202100656 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Z., Hong G., Shinji C., Chen C., Diao S., Antaris A. L., et al. (2013). Biological Imaging Using Nanoparticles of Small Organic Molecules with Fluorescence Emission at Wavelengths Longer Than 1000 Nm. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 13002–13006. 10.1002/anie.201307346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian R., Zeng Q., Zhu S., Lau J., Chandra S., Ertsey R., et al. (2019). Albumin-chaperoned Cyanine Dye Yields Superbright NIR-II Fluorophore with Enhanced Pharmacokinetics. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw0672. 10.1126/sciadv.aaw0672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S., Fan Y., Li D., Sun C., Lei Z., Lu L., et al. (2019). Anti-quenching NIR-II Molecular Fluorophores for In Vivo High-Contrast Imaging and pH Sensing. Nat. Commun. 10, 1058. 10.1038/s41467-019-09043-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welsher K., Liu Z., Sherlock S. P., Robinson J. T., Chen Z., Daranciang D., et al. (2009). A Route to Brightly Fluorescent Carbon Nanotubes for Near-Infrared Imaging in Mice. Nat. Nanotech 4, 773–780. 10.1038/nnano.2009.294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q., Hu Z., Zhu S., Ma R., Ma H., Ma Z., et al. (2018). Donor Engineering for NIR-II Molecular Fluorophores with Enhanced Fluorescent Performance. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 140, 1715–1724. 10.1021/jacs.7b10334 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Q., Ma Z., Wang H., Zhou B., Zhu S., Zhong Y., et al. (2017). Rational Design of Molecular Fluorophores for Biological Imaging in the NIR-II Window. Adv. Mater. 29, 1605497. 10.1002/adma.201605497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeroslaysky G., Umezawa M., Okubo K., Nigoghossian K., Doan Thi Kim D., Kamimura M., et al. (2019). Photostabilization of Indocyanine Green Dye by Energy Transfer in Phospholipid-PEG Micelles. J. Photopolymer Sci. Technology 32, 115–121. 10.2494/photopolymer.32.115 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang X.-D., Wang H., Antaris A. L., Li L., Diao S., Ma R., et al. (2016). Traumatic Brain Injury Imaging in the Second Near-Infrared Window with a Molecular Fluorophore. Adv. Mater. 28, 6872–6879. 10.1002/adma.201600706 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y., Zhang Y., Hong G., He W., Zhou K., Yang K., et al. (2013). Biodistribution, Pharmacokinetics and Toxicology of Ag2S Near-Infrared Quantum Dots in Mice. Biomaterials 34, 3639–3646. 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2013.01.089 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y., Ma Z., Zhu S., Yue J., Zhang M., Antaris A. L., et al. (2017). Boosting the Down-Shifting Luminescence of Rare-Earth Nanocrystals for Biological Imaging beyond 1500 Nm. Nat. Commun. 8, 737. 10.1038/s41467-017-00917-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S., Chen X. (2019). Overcoming the Colour Barrier. Nat. Photon. 13, 515–516. 10.1038/s41566-019-0500-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S., Hu Z., Tian R., Yung B. C., Yang Q., Zhao S., et al. (2018a). Repurposing Cyanine NIR-I Dyes Accelerates Clinical Translation of Near-Infrared-II (NIR-II) Bioimaging. Adv. Mater. 30, 1802546. 10.1002/adma.201802546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu S., Yung B. C., Chandra S., Niu G., Antaris A. L., Chen X. (2018b). Near-Infrared-II (NIR-II) Bioimaging via Off-Peak NIR-I Fluorescence Emission. Theranostics 8, 4141–4151. 10.7150/thno.27995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]