Key Points

Question

What are the similarities and differences in between pediatric and adult patients with hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) before diagnosis?

Findings

In this cohort study of 1094 pediatric patients and 7633 adults, pediatric patients with HS were likely to see pediatricians, emergency department staff, and family physicians and receive diagnoses of folliculitis and comedones before HS diagnosis. Pediatric patients with HS had high rates of comorbid acne vulgaris, acne conglobata, obesity, and anxiety.

Meaning

The findings of this study suggest that HS may be underdiagnosed in pediatric patients; education directed at primary care clinicians may aid in early recognition of HS and facilitate specialist referrals for outpatient treatment.

Abstract

Importance

Up to 50% of patients may have hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) onset between age 10 and 21 years. To our knowledge, little is known about how adolescents with HS utilize health care during their journey to receiving a diagnosis.

Objective

To assess the clinical characteristics and health care utilization patterns of pediatric vs adult patients with HS.

Design, Setting, and Participants

This retrospective cohort study included adult and pediatric patients with HS claims from the MarketScan medical claims database during the study period, January 1, 2012, to December 31, 2016. The data were analyzed between March 1 and March 31, 2021.

Exposures

Clinical characteristics and health care utilization patterns of pediatric vs adult patients with HS.

Main Outcomes and Measures

Health care utilization patterns were examined and included concurrent diagnoses, outpatient care by discipline, and emergency/urgent care and inpatient claims.

Results

This study included 8727 members, comprising 1094 pediatric (155 male [14.2%] and 939 female patients [85.8%]; mean [SD] age, 14.3 [2.47] years) and 7633 adult patients (1748 men [22.9%] and 5885 women [77.1%]; mean [SD] age, 37.2 [12.99] years). Pediatric patients were likely to see pediatricians, dermatologists, emergency department (ED) staff, and family physicians before diagnosis and commonly received diagnoses of folliculitis and comedones. Pediatric patients with HS had high rates of comorbid skin and general medical conditions, including acne vulgaris (558 [51.0%]), acne conglobata (503 [45.9%]), obesity (369 [33.7%]), and anxiety disorders (367 [33.6%]). A higher percentage of pediatric than adult patients had HS-specific claims for services rendered by emergency and urgent care physicians (35.6% vs 28.2%; P < .001; and 18.1% vs 13.4%; P < .001; respectively). However, adult patients were more likely to have inpatient stays (2.38% vs 4.22%; P = .002). Pediatric patients had 2.24 ED claims per person, while adults had 3.5 claims per person. The mean cost per ED claim was similar between groups ($413.27 vs $682.54; P = .18). The largest component of the total 5-year disease-specific cost was the cost of inpatient visits for pediatric and adult patients with HS.

Conclusions and Relevance

This cohort study suggests that pediatric patients utilize high-cost ED care when HS can often be treated as an outpatient. These data suggest that there are opportunities to improve recognition of HS in pediatric patients by nondermatologists and dermatologists.

This cohort study examines clinical characteristics and health care utilization patterns of pediatric vs adult patients with hidradenitis suppurativa.

Introduction

Hidradenitis suppurativa (HS) is a chronic, inflammatory, follicular occlusive disease.1 It has an average onset at age 23 years and is reportedly rare in children, with an estimate that fewer than 2% of cases occur before age 11 years.2 Despite this, up to 50% of patients show symptoms between ages 10 and 21 years.3,4,5 Thus, HS is likely not rare in pediatric patients, but the estimates may reflect delays in seeking care, potential for misdiagnosis, or underdiagnosing.6,7,8,9 Small studies and case reports reveal that pediatric patients with HS present to endocrinology, pediatrics or other primary care, or gastroenterology departments.10,11,12,13,14 Prompt diagnosis by all clinicians with prompt referral for treatment is important, as it may also mitigate the need for care in high-cost settings, such as the emergency department (ED) or inpatient hospitalization.15 However, to our knowledge, specific data are unavailable on how pediatric patients with HS utilize health care.

In addition, HS can be associated with other comorbid conditions; however, these associations have been primarily studied in adults with HS.16 Based on previous studies, pediatric patients with HS have been reported to have comorbid endocrine dysfunction, particularly precocious puberty, premature adrenarche, metabolic syndrome, hypothyroidism, polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS), or androgen excess.12,14,17,18 However, these studies are generally small, and comorbid conditions in pediatric patients with HS need to be further elucidated. Overall, little is known about how the presentation and manifestations of HS compare between the pediatric and adult populations. Therefore, in this study, we sought to assess and compare (1) demographic characteristics, (2) comorbidities, and (3) health care utilization patterns, including high-cost inpatient and ED settings.

Methods

This retrospective claims analysis utilized data from the IBM MarketScan commercial database. These data include health insurance claims across the continuum of care (eg, inpatient, outpatient, and emergency/urgent care) as well as enrollment data from large employers and health plans across the US that provide private health care coverage for more than 92 million people. These data have Penn State Hershey institutional review board approval under expedited review. Informed consent was waived because it was a retrospective study that used deidentified data. As a claims database, clinical outcomes are not included.

A 5-year study period was used (January 1, 2012, to December 31, 2016). The study sample included only continuously enrolled individuals during the 5-year period. Patients with HS were defined by 2 or more claims for HS within 18 months as defined by International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision (ICD-9) or ICD-10 codes 705.8 or L73.2, respectively. The date of the first claim for HS was taken as the date of HS diagnosis. Patients were classified in the pediatric HS group if HS diagnosis occurred before age 18 years, whereas patients with an HS diagnosis at or after turning age 18 years were considered adults with HS. Hidradenitis suppurativa onset was based on the first claim for an HS-related diagnosis (Table 1). Delay from HS onset to diagnosis was calculated by taking the difference from claims for an HS-related diagnosis to the first claim for HS. Patient characteristics, including age and sex, were extracted, and comorbid conditions were abstracted based on ICD-9 or ICD-10 documentation on claims (eTable in the Supplement). The authors extracted comorbidities to be included in the study based on prior case reports and case series involving pediatric patients with HS. The utilization and cost variables for outpatient, ED or urgent care, and inpatient care were extracted for claims that included a diagnosis of HS. Claims without an HS diagnosis were excluded for urgent care/ED visits and inpatient stays. The cost of care was calculated from the health system perspective and was the sum of payments by the insurer and the patient. Costs were adjusted for inflation throughout the study period and are reported in 2020 dollars.

Table 1. Characteristics of Pediatric and Adult Patients With Hidradenitis Suppurativa.

| Participant characteristics | Participants, No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatric | Adult | ||

| Sample size, No. | 1094 | 7633 | NA |

| Mean (SD) age, y | 14.34 (2.47) | 37.16 (12.99) | |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 155 (14.2) | 1748 (22.9) | |

| Female | 939 (85.8) | 5885 (77.1) | |

| Age of HS, median (range), y | |||

| Onset | 15 (6-17) | 37 (14-64) | |

| Diagnosis | 15 (6-17) | 40 (18-64) | |

| Potential HS manifestations | |||

| Cutaneous abscess of limb | 83 (7.59) | 671 (8.79) | .19 |

| Carbuncle, unspecified | 91 (8.32) | 581 (7.61) | .41 |

| Furuncle, unspecified | 96 (8.77) | 656 (8.59) | .84 |

| Cellulitis, unspecified | 332 (30.35) | 2177 (28.52) | .21 |

| Folliculitis | 297 (27.15) | 1401 (13.64) | <.001 |

| Comedones (other acne) | 558 (51.00) | 1888 (24.73) | <.001 |

Abbreviations: HS, hidradenitis suppurativa; NA, not applicable.

Descriptive statistics were used to describe the demographic information, comorbid conditions, and the health care utilization and cost data for the cohorts. Calculations included only those members with claims. Differences between cohorts were explored; comparisons of categorical outcomes were made using the χ2 test. Comparisons of continuous outcome variables were made using the t test. Statistical software (SAS, version 9.4; SAS Institute) was used for all analyses. P value less than .05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

This study included 8727 members, comprising pediatric (1094 [12.5%]) and adult (7633 [87.5%]) patients; their characteristics are shown in Table 1. Most patients were female in the pediatric and adult populations, although a higher percentage of patients were female in the pediatric cohort (85.83% vs 77.10%). The mean (SD) age of HS onset, which was based on first claim for HS sign/symptoms, was 14.3 (2.5) years in the pediatric cohort and 37 (13) years in the adult cohort. The mean (SD) age of HS diagnosis was 15 (2) years in the pediatric population and 40 (14) years in the adult population, with a mean delay of 0 and 3 years (P < .001) from symptom onset to diagnosis in the pediatric and adult populations, respectively. Pediatric patients were more likely than adults to receive a diagnosis of comedones (51.00% vs 24.73%; P < .001) and folliculitis (27.15% vs 13.64%, P < .001) while other diagnoses, such as cellulitis, abscesses, and furuncles, were not significantly different between the 2 groups.

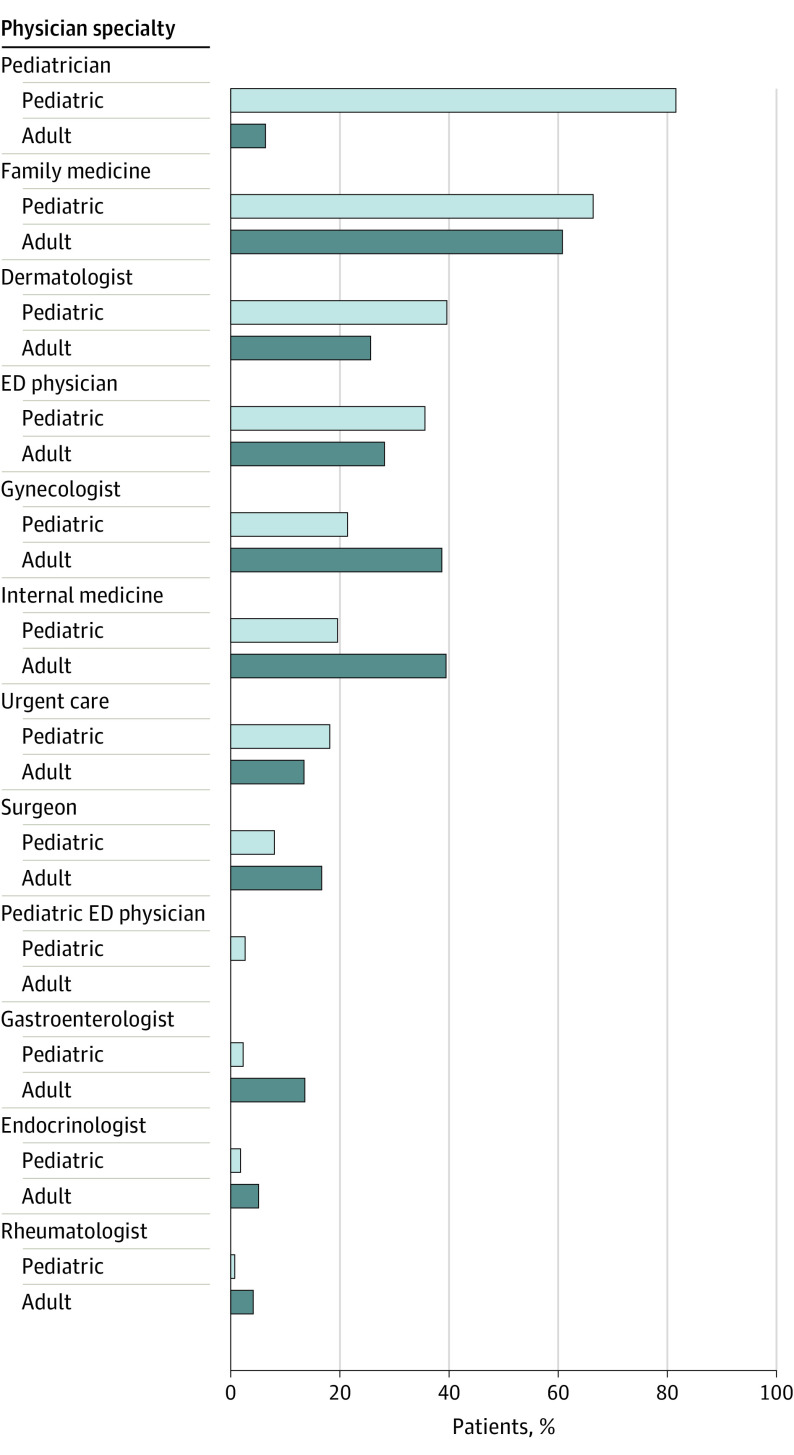

Before HS diagnosis, pediatric and adult patients with HS were most likely to be seen by primary care clinicians. Pediatric patients with HS obtained care from multiple types of clinicians (Figure). They were most likely to have been seen by a pediatric clinician (894 [81.7%]), family medicine (727 [66.5%]), and dermatology department (435 [39.8%]) before HS diagnosis. Comparatively, adult patients with HS presented to family medicine (4634 [60.7%]), internal medicine (3017 [39.5%]), and gynecology departments (2951 [38.7%]). A higher percentage of pediatric than adult patients had care from the ED and urgent care physicians before diagnosis (35.6% vs 28.2%; P < .001 and 18.1% vs 13.4%; P < .001, respectively). Overall, pediatric patients were less likely to see any surgeon than adults (8.1% vs 16.7%; P < .01). This number was not stratified by surgeon type. However, a total of 373 pediatric patients with HS (34.1%) had incision and drainage claims, while 151 (13.8%) had an excision for HS.

Figure. Physician Specialty Seen Before Hidradenitis Suppurativa Diagnosis.

All specialties were significantly statistically different between pediatric and adult cohorts. ED indicates emergency department.

There were similarities and differences in the comorbidities associated with HS among the adult and pediatric groups (Table 2). In the pediatric population, acne vulgaris (558 [51.0%]), acne conglobata (503 [45.9%]), obesity (369 [33.7%]), and anxiety disorder (367 [33.6%]) were the most common comorbidities. In the adult HS population, obesity (3343 [43.8%]), anxiety disorder (3216 [42.1%]), hyperlipidemia (2530 [33.1%]), and acne vulgaris (1888 [24.7%]) were the most common comorbidities.

Table 2. Comorbidities of Pediatric and Adult Patients With Hidradenitis Suppurativa.

| Comorbidities | Participants, No. (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatric | Adult | ||

| Cutaneous | |||

| Acne vulgaris | 558 (51.00) | 1888 (24.73) | <.001 |

| Pyoderma gangrenosum | 6 (0.55) | 54 (0.71) | .55 |

| Pilonidal cyst | 73 (6.67) | 385 (5.04) | .02 |

| Acne conglobata | 503 (45.98) | 1610 (21.09) | <.001 |

| Endocrinologic | |||

| Diabetes | |||

| Type 1 | 20 (1.83) | 215 (2.82) | .06 |

| Type 2 | 50 (4.57) | 1665 (21.81) | <.001 |

| Hypothyroidism | 64 (5.85) | 1164 (15.25) | <.001 |

| Polycystic ovary syndrome | 76 (6.95) | 490 (6.03) | .24 |

| Precocious puberty | 15 (1.37) | 0 | <.001 |

| Obesity, unspecified | 369 (33.73) | 3343 (43.80) | <.001 |

| Metabolic syndrome | 47 (4.30) | 313 (4.1) | .76 |

| Psychiatric | |||

| MDD, recurrent, unspecified | 59 (5.39) | 566 (7.41) | .02 |

| Anxiety disorder, unspecified | 367 (33.55) | 3216 (42.13) | <.001 |

| Tobacco use | 10 (0.91) | 1394 (18.26) | <.001 |

| Other psychoactive abuse, uncomplicated | 9 (0.82) | 45 (0.59) | .26 |

| Cardiovascular | |||

| Essential (primary) hypertension | 22 (2.01) | 3018 (39.54) | <.001 |

| Hyperlipidemia, unspecified | 47 (4.30) | 2530 (33.14) | <.001 |

| Autoimmune | |||

| Crohn disease | 19 (1.74) | 139 (1.82) | .85 |

| Arthropathy, unspecified | 11 (1.00) | 440 (5.76) | <.001 |

| Spondyloarthropathy | 0 | 0 | >.99 |

Abbreviation: MDD, major depressive disorder.

The total 5-year disease-specific ED/urgent care cost for the pediatric and adult HS cohorts after HS diagnosis totaled $61 163.74 and $1 324 130.59, respectively, with 148 claims for 66 patients in the pediatric cohort and 1940 claims for 553 patients in the adult cohort. Pediatric patients had a mean (SD) of 2.24 (1.69) ED claims per person, while adults had 3.5 (4.99) claims per person. The proportion of pediatric and adult patients with HS with ED claims was similar (6.03% vs 6.97%; P = .28), as was the mean cost per ED claim given the large standard deviation ($413.27 vs $682.54; P = .18). The largest component of the total 5-year disease-specific cost was the cost of inpatient visits for adult and pediatric patients with HS, with 30 hospitalizations totaling $811 235 in the pediatric cohort and 541 hospitalizations totaling $12 854 273 in the adult cohort (Table 3). The proportion of pediatric and adult patients with HS with inpatient stays was significantly different (2.38% vs 4.22%; P = .002); however, the mean hospital days per stay was similar (4.9 vs 6.5 days; P = .49).

Table 3. Emergency Department and Inpatient Costs for Pediatric and Adult Patients With Hidradenitis Suppurativa.

| Characteristic | Participants | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pediatric | Adult | ||

| Patients with HS | 1094 | 7933 | |

| Patients with an ED claim for HS, No. (%) | 66 (6.03) | 553 (6.97) | .28 |

| HS ED claims | |||

| Claims, total | 148 | 1940 | NA |

| Claims per person | 2.24 | 3.5 | |

| Cost per claim, mean (SD), $ | 413.27 (474.73) | 682.54 (2451.43) | .18 |

| Cost per claim, median (range), $ | 227.63 (0.50-3129.69) | 173.42 (0.13-23 080.40) | NA |

| Total ED costs, $ | 61 163.75 | 1 324 130.59 | .18 |

| Patients with an HS inpatient claim, No. (%) | 26 (2.38) | 335 (4.22) | <.05 |

| HS inpatient claims | |||

| Total | 30 | 541 | NA |

| Per person | 1.15 | 1.61 | |

| Total inpatient days | 147 | 3523 | NA |

| Hospital length of stay, mean (SD), d | 4.9 (4.5) | 6.5 (12.7) | .49 |

| HS inpatient costs per visit, mean (SD), $ | 27 041 (29 414.9) | 23 760 (35 862.99) | .58 |

| Total inpatient costs, $ | 811 234.92 | 12 854 273.01 | .58 |

Abbreviations: ED, emergency department; HS, hidradenitis suppurativa; NA, not applicable.

Discussion

This study included 8727 patients with HS, including 1094 pediatric patients, making this one of the largest studies of children with HS. To our knowledge, the largest published study to date included 481 children.19 The findings of the present study confirmed that most children with HS are female (85.83%), with the mean age of symptom onset at 15 years, which are similar findings to the recent study by Liy-Wong et al19 that found that 80% were female and the mean age of diagnosis of 14.4 years. The female to male ratio for pediatric patients in our study was 6:1. This value is higher than observations in adult populations, which are typically 3:1.17,18 This may be secondary to an earlier age of onset of HS symptomatology in female pediatric patients or health care–seeking behaviors in pediatric female patients.

This study also highlights the importance of disciplines, such as pediatrics, family medicine, and emergency medicine, in HS diagnosis and management. Critically, pediatric and adult patients with HS were likely to receive care by primary care clinicians before diagnosis. These disciplines have the opportunity to promptly and accurately recognize and diagnose HS to initiate first-line management and referral to a dermatologist or other clinician who is experienced with HS. It has been shown that there is a discrepancy between nondermatologists and dermatologists for the diagnosis of skin conditions, which may partially explain the underdiagnosis of HS.20,21 Given that pediatric patients in this study and a prior study received diagnoses of comedones and folliculitis before HS diagnosis, these features may be critical in helping clinicians recognize HS.17 It is possible that pediatric patients with HS present with less severe disease than adults given early HS findings, along with decreased evaluation by surgical specialists. Increased clinician education, improved screening measures for HS, and coordination of care could lead to decreased diagnostic delay and more effective management of HS.

In the pediatric cohort, patients with HS had high rates of comorbid skin and general medical conditions, including acne vulgaris (51.0%), acne conglobata (45.9%), obesity (33.7%), and anxiety disorders (33.6%). Previous studies have shown that pediatric HS is associated with endocrine dysfunction and inflammatory bowel disease.12,14,17,18,22,23 Similarly, this study showed the prevalence of endocrine disorders, such as type 1 diabetes (1.83%), type 2 diabetes (4.57%), hypothyroidism (5.85%), PCOS (6.95%), precocious puberty (1.37%), and Crohn disease (1.74%). These rates are similar to comorbidity rates in prior studies that showed rates of type 1 diabetes (2.6%-5%), type 2 diabetes (1-2%-2.6%), thyroid dysfunction (2.9%-5%), PCOS (0.2%-3.6%), precocious puberty (0.2%-3.6%), and inflammatory bowel disease (1%-3.3%) in pediatric patients with HS.19,24 Obesity was less prevalent in the pediatric (33.7%) cohort compared with the adult cohort (43.8%) in this study; however, it is important to recognize that obesity in the pediatric HS cohort was higher than the US national average of 18.5%.25 Similarly, while anxiety in the pediatric HS cohort was less than the adult cohort, it was higher than the 10.5% reported by the US Centers for Disease Control for individuals aged 12 to 17 years.26 Moreover, the rate of anxiety in our study was higher than that reported in a study by Tiri et al27 in which psychiatric disorders were the single most common comorbidity in pediatric patients with HS (15.7%), and 5.9% of those were anxiety disorders. Early recognition of these comorbid conditions is crucial to the holistic treatment of patients with HS.28,29

Adults with HS have an increased utilization of high-cost care settings, such as the ED and inpatient hospitalization.23,30,31 In this study, pediatric patients with HS had a comparable number of ED utilization claims per person compared with adult patients with HS. Pediatric patients with HS may seek care from high-cost settings, such as the ED or urgent care, if their outpatient clinician is unable to diagnose or manage their disease. Because of geographic location, finances, or specialist appointment scarcity, many patients with HS do not receive a diagnosis or are unable to receive timely care; therefore, they turn to the ED for diagnosis or symptom relief. In terms of inpatient care, pediatric patients with HS had significantly fewer inpatient hospitalization claims than adult patients; however, they did not differ in the mean cost nor days per stay between cohorts. This difference may be because of the higher occurrence of any comorbid condition in adult patients. The ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes extracted for this study were those that listed HS on the admission chart but not necessarily as the primary reason for admission. In addition, HS may be preferentially underrecognized in the pediatric population, so it is possible that the diagnosis of HS was not included on inpatient claims.

Limitations

The findings of this study should be understood in the context of its limitations. The MarketScan database may not be representative of nor generalizable to other patient populations as it represents those with private insurance, and so may not apply to patients without insurance. Given that patients were identified by HS-specific ICD-9 and ICD-10 codes, the study may favor those with more severe disease. Moreover, the data set only includes patients with a correct diagnosis, while HS is frequently misdiagnosed or undiagnosed. Therefore, the number of cases in this data set likely underrepresents the true number of HS cases. The data set does not contain information on race and ethnicity, clinical findings, or disease severity, so these could not be evaluated in our study and, as such, it may underestimate the delay in diagnosis because of differences in clinical notes and charges on claims. In addition, it is not known whether the HS-related diagnoses extracted in our study were associated with the subsequent HS diagnosis; therefore, reported diagnostic delay may not represent the true timing of care received. Finally, the costs described are all-cause and not just those specific to HS.

Early recognition, prompt intervention, and referral to a dermatologist may be the key to managing the complications and comorbidities of pediatric HS. Ultimately, this may prevent the utilization of high-cost care settings, such as the ED or inpatient hospitalization. Given that pediatric HS populations may present with endocrine abnormalities, higher than average obesity rates, and higher than average anxiety disorder rates compared with their peers, it is important to emphasize patient and clinician education as well as coordination of care among clinicians. Addressing these potential issues may prove to be highly beneficial in controlling patient symptoms, preventing unnecessary health care costs, and, ultimately, getting patients the timely and effective care they require. Given that pediatric and adult patients with HS were most likely to present to primary care specialties before diagnosis, targeted education regarding early manifestations of HS for these clinicians may facilitate early dermatology referral.

Conclusions

Pediatric patients utilize high-cost ED care when HS in children and adults can often be treated as an outpatient if referred to the proper specialist. These data suggest that there are opportunities to improve recognition of HS in pediatrics by nondermatologists and dermatologists.

eTable. Variable Definitions

References

- 1.Jemec GBE. Clinical practice: hidradenitis suppurativa. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(2):158-164. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp1014163 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Scheinfeld N. Hidradenitis suppurativa in prepubescent and pubescent children. Clin Dermatol. 2015;33(3):316-319. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2014.12.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Molina-Leyva A, Cuenca-Barrales C. Adolescent-onset hidradenitis suppurativa: prevalence, risk factors and disease features. Dermatology. 2019;235(1):45-50. doi: 10.1159/000493465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.von der Werth JM, Williams HC. The natural history of hidradenitis suppurativa. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2000;14(5):389-392. doi: 10.1046/j.1468-3083.2000.00087.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jemec GB. The symptomatology of hidradenitis suppurativa in women. Br J Dermatol. 1988;119(3):345-350. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1988.tb03227.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garg A, Wertenteil S, Baltz R, Strunk A, Finelt N. Prevalence estimates for hidradenitis suppurativa among children and adolescents in the United States: a gender- and age-adjusted population analysis. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(10):2152-2156. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2018.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Micheletti RG. Hidradenitis suppurativa: current views on epidemiology, pathogenesis, and pathophysiology. Semin Cutan Med Surg. 2014;33(3)(suppl):S48-S50. doi: 10.12788/j.sder.0091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dessinioti C, Tzanetakou V, Zisimou C, Kontochristopoulos G, Antoniou C.. A Retrospective Study of the Characteristics of Patients with Early-Onset Compared to Adult-Onset Hidradenitis Suppurativa. Vol 57. Blackwell Publishing Ltd; 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bettoli V, Ricci M, Zauli S, Virgili A. Hidradenitis suppurativa-acne inversa: a relevant dermatosis in paediatric patients. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173(5):1328-1330. doi: 10.1111/bjd.13951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wortsman X, Rodriguez C, Lobos C, Eguiguren G, Molina MT. Ultrasound diagnosis and staging in pediatric hidradenitis suppurativa. Pediatr Dermatol. 2016;33(4):e260-e264. doi: 10.1111/pde.12895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Krakowski AC, Admani S, Uebelhoer NS, Eichenfield LF, Shumaker PR. Residual scarring from hidradenitis suppurativa: fractionated CO2 laser as a novel and noninvasive approach. Pediatrics. 2014;133(1):e248-e251. doi: 10.1542/peds.2012-3356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Palmer RA, Keefe M. Early-onset hidradenitis suppurativa. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2001;26(6):501-503. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2230.2001.00876.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Prabhu G, Laddha P, Manglani M, Phiske M. Hidradenitis suppurativa in a HIV-infected child. J Postgrad Med. 2012;58(3):207-209. doi: 10.4103/0022-3859.101403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Randhawa HK, Hamilton J, Pope E. Finasteride for the treatment of hidradenitis suppurativa in children and adolescents. JAMA Dermatol. 2013;149(6):732-735. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.2874 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khalsa A, Liu G, Kirby JS. Increased utilization of emergency department and inpatient care by patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(4):609-614. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.06.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shlyankevich J, Chen AJ, Kim GE, Kimball AB. Hidradenitis suppurativa is a systemic disease with substantial comorbidity burden: a chart-verified case-control analysis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2014;71(6):1144-1150. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2014.09.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liy-Wong C, Pope E, Lara-Corrales I. Hidradenitis suppurativa in the pediatric population. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2015;73(5)(suppl 1):S36-S41. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2015.07.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mengesha YM, Holcombe TC, Hansen RC. Prepubertal hidradenitis suppurativa: two case reports and review of the literature. Pediatr Dermatol. 1999;16(4):292-296. doi: 10.1046/j.1525-1470.1999.00077.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liy-Wong C, Kim M, Kirkorian AY, et al. Hidradenitis Suppurativa in the pediatric population: an international, multicenter, retrospective, cross-sectional study of 481 pediatric patients. JAMA Dermatol. 2021;157(4):385-391. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.5435 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tran H, Chen K, Lim AC, Jabbour J, Shumack S. Assessing diagnostic skill in dermatology: a comparison between general practitioners and dermatologists. Australas J Dermatol. 2005;46(4):230-234. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0960.2005.00189.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gerbert B, Maurer T, Berger T, et al. Primary care physicians as gatekeepers in managed care: primary care physicians’ and dermatologists’ skills at secondary prevention of skin cancer. Arch Dermatol. 1996;132(9):1030-1038. doi: 10.1001/archderm.1996.03890330044008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lewis F, Messenger AG, Wales JKH. Hidradenitis suppurativa as a presenting feature of premature adrenarche. Br J Dermatol. 1993;129(4):447-448. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.1993.tb03174.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iskandar H, Greer JB, Krasinskas AM, et al. IBD LIVE series—case 8: treatment options for refractory esophageal Crohn’s disease and hidradenitis suppurativa. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23(10):1667-1677. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Riis PT, Saunte DM, Sigsgaard V, et al. Clinical characteristics of pediatric hidradenitis suppurativa: a cross-sectional multicenter study of 140 patients. Arch Dermatol Res. 2020;312(10):715-724. doi: 10.1007/s00403-020-02053-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hales CM, Carroll MD, Fryar CD, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016 key findings data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Accessed December 22, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db288_table.pdf#1

- 26.US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Data and statistics on children’s mental health. Accessed December 22, 2022. https://www.cdc.gov/childrensmentalhealth/data.html#ref/

- 27.Tiri H, Jokelainen J, Timonen M, Tasanen K, Huilaja L. Somatic and psychiatric comorbidities of hidradenitis suppurativa in children and adolescents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2018;79(3):514-519. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.02.067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Garg A, Neuren E, Cha D, et al. Evaluating patients’ unmet needs in hidradenitis suppurativa: results from the Global Survey Of Impact and Healthcare Needs (VOICE) Project. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;82(2):366-376. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2019.06.1301 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thorlacius L, Cohen AD, Gislason GH, Jemec GBE, Egeberg A. Increased suicide risk in patients with hidradenitis suppurativa. J Invest Dermatol. 2018;138(1):52-57. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2017.09.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Braunberger TL, Nicholson CL, Gold L, et al. Hidradenitis suppurativa in children: the Henry Ford experience. Pediatr Dermatol. 2018;35(3):370-373. doi: 10.1111/pde.13466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Alavi A, Lynde C, Alhusayen R, et al. Approach to the management of patients with hidradenitis suppurativa: a consensus document. J Cutan Med Surg. 2017;21(6):513-524. doi: 10.1177/1203475417716117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

eTable. Variable Definitions