Abstract

Prevention behaviors represent important public health tools to limit spread of SARS-CoV-2. Adherence with recommended public health prevention behaviors among 20000 + members of a COVID-19 syndromic surveillance cohort from the mid-Atlantic and southeastern United States was assessed via electronic survey following the 2020 Thanksgiving and winter holiday (WH) seasons. Respondents were predominantly non-Hispanic Whites (90%), female (60%), and ≥ 50 years old (59%). Non-household members (NHM) were present at 47.1% of Thanksgiving gatherings and 69.3% of WH gatherings. Women were more likely than men to gather with NHM (p < 0.0001). Attending gatherings with NHM decreased with older age (Thanksgiving: 60.0% of participants aged < 30 years to 36.3% aged ≥ 70 years [p-trend < 0.0001]; WH: 81.6% of those < 30 years to 61.0% of those ≥ 70 years [p-trend < 0.0001]). Non-Hispanic Whites were more likely to gather with NHM than were Hispanics or non-Hispanic Blacks (p < 0.0001). Mask wearing, reported by 37.3% at Thanksgiving and 41.9% during the WH, was more common among older participants, non-Hispanic Blacks, and Hispanics when gatherings included NHM. In this survey, most people did not fully adhere to recommended public health safety behaviors when attending holiday gatherings. It remains unknown to what extent failure to observe these recommendations may have contributed to the COVID-19 surges observed following Thanksgiving and the winter holidays in the United States.

Keywords: COVID-19, Holiday travel, Gatherings, Prevention behaviors

Introduction

After declining following a summer surge, infections due to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2) precipitously increased across the United States with over 1.87 million cases reported during the month of October 2020 [1]. New cases exceeded 100000 per day for the first time on 30 October [2]. With Thanksgiving approaching, it was widely reported in the news media that Thanksgiving gatherings might serve as superspreader events, further exacerbating the surge in coronavirus disease-19 (COVID-19) cases [3]. Guidelines for Thanksgiving travel and safe holiday gatherings were issued by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) on 12 November [4]. Guidance included recommendations to minimize travel, to take steps to prevent transmission if gathering with non-household members (NHM), and to limit the number of guests at gatherings. At any type of gathering, all attendees were encouraged to wear masks, observe social distancing guidelines, wash their hands often, and gather outdoors if possible [4]. Despite recommendations designed to decrease the risk of SARS-CoV-2 transmission by attending celebrations only with people in the household and deferring travel, the Associated Press reported that 1.17 million travelers passed through US airports on the Sunday after Thanksgiving [5]. Predictions of a post-Thanksgiving surge proved accurate [6, 7], so the CDC again cautioned Americans about travel and gatherings over the winter holiday (WH) season [8] and encouraged a broad range of safety precautions. As emphasized by the media, the potential consequences of WH travel and gatherings might be “catastrophic” [9], a concern that again proved prescient with COVID-19 cases peaking during the second week of January [10].

To assess participation in gatherings over Thanksgiving and during the WH season, especially those involving NHM, and to collect information about the use of measures to prevent exposure to, and transmission of, SARS-CoV-2 during gatherings, we surveyed > 20,000 participants in the COVID-19 Community Research Partnership (CCRP) after Thanksgiving 2020 and again in early January 2021. The results of those two surveys form the basis for this report.

Methods

The CCRP is a COVID-19 syndromic surveillance program approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. This activity was also reviewed by CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy. Participants were recruited through direct email outreach to enroll patient populations from health care systems at six sites (Table 1): Wake Forest Baptist Health in the Winston-Salem NC, USA area, Atrium Health in the Charlotte NC, USA area, WakeMed in the Raleigh NC, USA area, MedStar Health in the Washington DC, USA area, New Hanover Regional Medical Center in the Wilmington NC, USA area, and a small number of participants at the University of Mississippi in the Oxford MS, USA area. Participants provided informed consent through an online consenting system. Over 32000 adults 18 years and older had volunteered to participate in the partnership by 24 December, 2020 with most originating from the mid-Atlantic (Washington DC area) and southeastern (North Carolina) United States. Beginning in April, 2020, CCRP participants began receiving a brief 5-question daily electronic survey via text or e-mail asking the recipient to report their health status, including questions about COVID-19 symptoms, testing, and diagnoses. To assess attendance at Thanksgiving and WH gatherings with NHM and use of recommended safety behaviors to prevent COVID-19, supplemental mini-surveys consisting of questions focused upon holiday behaviors were added to the standard daily survey on 30 November, 2020 covering the 4-day Thanksgiving holiday and on 4 January, 2021 covering the 2-week winter holiday period (Fig. 1). It should be noted that the opportunity for COVID-19 vaccination was limited at the time of the two surveys.

Table 1.

Percentage of people in selected regions of the southeastern United States who gathered with persons outside their immediate household at Thanksgiving, 2020, and during the winter holiday, 2020–2021, according to age, sex, race/ethnicity, healthcare worker status, and study site

| Did you gather with people outside your immediate household over Thanksgiving? | Did you gather with people outside your immediate household over the winter holiday? | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | No | Yes | RR (95%CI) | p-value | Total | No | Yes | RR (95% CI) | p-value | |||||

| n | n | Percent | n | Percent | n | n | Percent | n | Percent | |||||

| Total | 20281 | 10721 | 52.9 | 9560 | 47.1 | 26841 | 8249 | 30.7 | 18592 | 69.3 | ||||

| Sex | ||||||||||||||

| Women | 13985 | 7204 | 51.5 | 6781 | 48.5 | 1.10 (1.06, 1.14) | < 0.0001 | 18579 | 5507 | 29.6 | 13072 | 70.4 | 1.05 (1.03, 1.07) | < 0.0001 |

| Men | 6296 | 3517 | 55.9 | 2779 | 44.1 | Ref | 8262 | 2742 | 33.2 | 5520 | 66.8 | Ref | ||

| Age group (years) | ||||||||||||||

| < 30 | 1151 | 460 | 40.0 | 691 | 60.0 | 1.65 (1.55, 1.77) | < 0.0001 | 1375 | 253 | 18.4 | 1122 | 81.6 | 1.34 (1.29, 1.39) | < 0.0001 |

| 30–39 | 3253 | 1402 | 43.1 | 1851 | 56.9 | 1.57 (1.48, 1.66) | 4313 | 956 | 22.2 | 3357 | 77.8 | 1.28 (1.24, 1.32) | ||

| 40–49 | 3926 | 2020 | 51.5 | 1906 | 48.5 | 1.34 (1.26, 1.42) | 5351 | 1568 | 29.3 | 3783 | 70.7 | 1.16 (1.12, 1.20) | ||

| 50–59 | 4405 | 2357 | 53.5 | 2048 | 46.5 | 1.28 (1.21, 1.36) | 5640 | 1833 | 32.5 | 3807 | 67.5 | 1.11 (1.07, 1.14) | ||

| 60–69 | 4618 | 2616 | 56.6 | 2002 | 43.4 | 1.20 (1.13, 1.27) | 6282 | 2124 | 33.8 | 4158 | 66.2 | 1.09 (1.05, 1.12) | ||

| ≥ 70 | 2928 | 1866 | 63.7 | 1062 | 36.3 | Ref | 3880 | 1515 | 39.0 | 2365 | 61.0 | Ref | ||

| Race/ethnicity | ||||||||||||||

| White (not Hispanic/Latino) | 18235 | 9427 | 51.7 | 8808 | 48.3 | 1.54 (1.40, 1.70) | < 0.0001 | 24072 | 7129 | 29.6 | 16943 | 70.4 | 1.28 (1.22, 1.35) | < 0.0001 |

| Hispanic or Latino | 455 | 265 | 58.2 | 190 | 41.8 | 1.34 (1.15, 1.55) | 604 | 224 | 37.1 | 380 | 62.9 | 1.15 (1.06, 1.24) | ||

| Other | 720 | 431 | 59.9 | 289 | 40.1 | 1.28 (1.12, 1.46) | 1003 | 371 | 37.0 | 632 | 63.0 | 1.15 (1.07, 1.23) | ||

| Black or African American | 871 | 598 | 68.7 | 273 | 31.3 | RAef | 1162 | 525 | 45.2 | 637 | 54.8 | Ref | ||

| Study site | ||||||||||||||

| WakeMed | 565 | 249 | 44.1 | 316 | 55.9 | 1.40 (1.22, 1.61) | < 0.0001 | 2524 | 708 | 28.1 | 1816 | 71.9 | 1.09 (1.05, 1.13) | < 0.0001 |

| New Hanover | 276 | 123 | 44.6 | 153 | 55.4 | 1.39 (1.27, 1.53) | 653 | 161 | 24.7 | 492 | 75.3 | 1.14 (1.08, 1.20) | ||

| Atrium Health | 5260 | 2639 | 50.2 | 2621 | 49.8 | 1.25 (1.14, 1.37) | 5477 | 1695 | 30.9 | 3782 | 69.1 | 1.04 (1.01, 1.08) | ||

| Wake Forest Baptist Health | 13462 | 7278 | 54.1 | 6184 | 45.9 | 1.15 (1.02, 1.31) | 15729 | 4869 | 31.0 | 10860 | 69.0 | 1.04 (1.01, 1.07) | ||

| U Mississippi | 0 | 87 | 17 | 19.5 | 70 | 80.5 | 1.21 (1.09, 1.35) | |||||||

| MedStar Health Research Institute | 718 | 432 | 60.2 | 286 | 39.8 | Ref | 2371 | 799 | 33.7 | 1572 | 66.3 | Ref | ||

| Healthcare worker | ||||||||||||||

| Yes | 6002 | 2959 | 49.3 | 3043 | 50.7 | 1.11 (1.08, 1.15) | < 0.0001 | 7464 | 2210 | 29.6 | 5254 | 70.4 | 1.02 (1, 1.04) | < 0.0001 |

| No | 14279 | 7762 | 54.4 | 6517 | 45.6 | Ref | 19377 | 6039 | 31.2 | 13338 | 68.8 | Ref | ||

Chi-square tests were used to compare frequency of gathering and safe behaviors across demographic groups, and Mantel–Haenszel Chi-square test for trend was used across age groups

RR = risk ratio; risk ratios compared percentages in each category to the reference category indicated with 95% confidence intervals computed based on the asymptotic normality of maximum likelihood estimators

Fig. 1.

Questions included in electronic surveys completed by study participants following Thanksgiving and the winter holidays

Statistical Methods

Chi-square tests were used to compare completion of supplemental questionnaires, frequency of gathering, and safe behaviors among those who gathered, across demographic groups, with Mantel–Haenszel Chi-square used across age groups; risk ratios (95% confidence intervals) compared percentages in each category to the reference category indicated. Multivariable logistic regression models were used to identify variables that independently predict gathering with NHM at each of the holidays, and among those who gathered to independently predict mask wearing during the gatherings, adjusting for age, sex, race/ethnicity, study site and healthcare worker status in both models. For Thanksgiving only, participants who reported three or more specified behaviors (pre-gathering COVID-19 testing, mask wearing, social distancing, hand washing, and outdoor gatherings) were compared to those who reported none or one behavior. Confidence limits for the estimated parameters were computed based on the asymptotic normality of maximum likelihood estimators. SAS, Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA) was used for all analysis.

Results

Of 25427 participants enrolled in the CCRP by 30 November, 2020, 20281 (79.8%) completed the post-Thanksgiving mini-survey, 26841 of 32031 participants (83.8%) enrolled by 24 December, 2020 completed the post-WH survey, and 19354 participants responded to both surveys. The majority of respondents were non-Hispanic White (Thanksgiving: 89.7%, WH: 89.0%), female (Thanksgiving: 70.2%; WH: 70.0%), and aged ≥ 50 years (Thanksgiving: 52.2%; WH: 52.5%). Healthcare workers comprised 30.8 and 29.0% of the study population at Thanksgiving and WH, respectively. Response rates differed by sex (Thanksgiving: 80.3% men vs. 75.6% women; WH: 83.0% men vs. 80.3% women; both p < 0.0001), age (Thanksgiving: decreasing from 90.2% in those age ≥ 70 years to 57.4% in those < 30 years; WH: decreasing from 90.8% in those age ≥ 70 years to 62.6% in those < 30 years; both p-trend < 0.0001), and healthcare worker status (Thanksgiving: 78.3% non-healthcare worker vs. 74.0% healthcare worker; WH: 82.2% non-healthcare worker vs. 78.3% healthcare workers; both p < 0.0001). A total of 9560 (47.1%) respondents indicated that they attended gatherings with NHM during Thanksgiving, whereas a higher percentage of respondents (69.3%) attended gatherings with NHM over the WH.

Table 1 compares demographic characteristics of those participating and not participating in gatherings with NHM over Thanksgiving and during the WH. Women were slightly more likely to gather with persons outside their household than were men (Thanksgiving: 48.5 vs. 44.1%, p < 0.0001; WH: 70.4 vs. 66.8%, p < 0.0001). The percent of participants who attended gatherings with NHM decreased with increasing age (Thanksgiving: 60.0% of participants aged < 30 years to 36.3% of participants aged ≥ 70 years [p-trend < 0.0001]; WH: 81.6% of participants aged < 30 years to 61% of participants aged ≥ 70 years [p-trend < 0.0001]). Gathering with NHM differed across race/ethnic group (p < 0.0001) with non-Hispanic White participants more likely to gather with NHM than were Hispanic or Latino, or non-Hispanic Black or African American participants during both Thanksgiving and the WH (Thanksgiving: 48.3 vs. 41.8% and 31.3%, respectively; WH: 70.4 vs. 62.9% and 54.8%, respectively). Healthcare workers more frequently participated in gatherings with NHM than did non-healthcare workers (Thanksgiving: 50.7 vs. 45.6%, p < 0.0001; WH: 70.4% vs. 68.8, p < 0.0001). At both holidays, participants from MedStar Health Research Institute, which encompasses the Washington, DC, USA metro area, were least likely to hold gatherings with members outside their household (p < 0.0001). During both holidays, women, older age, non-Hispanic Black or African American race, Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, and enrollment from MedStar Health and, during the WH, occupation as a healthcare worker, were independently predictive of not gathering with NHM (data not shown).

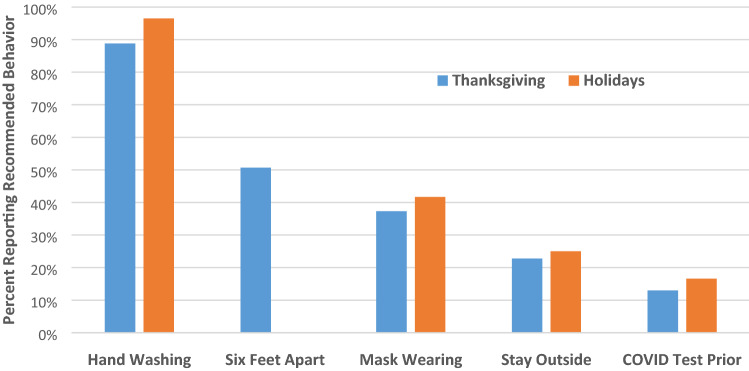

Prevalence of specified behaviors (pre-gathering COVID testing, frequent hand hygiene, social distancing, masking, gathering outdoors) among those who gathered with NHM during both Thanksgiving and the WH is summarized in Fig. 2. Of those gathering with NHM, 13.0 and 16.7% underwent testing for COVID-19 prior to gathering at Thanksgiving and the WH, respectively. Among those gathering during the Thanksgiving holiday, 88.8% reported washing hands or using hand sanitizer, 50.7% avoided contact with others within 6 feet, and 37.3% indicated that they wore a mask or face covering. Twenty-three percent of participants who reported gatherings with NHM indicated that gatherings were held outdoors. During the WH, 96.7% reported washing hands or using hand sanitizer and 41.9% wore face masks; gathering outdoors only was reported for 25.1% of gatherings. At Thanksgiving, three or more specified behaviors were reported by 38% of respondents whereas 37% utilized only one or none. During both holidays, age ≥ 70 years, non-Hispanic Black or African American race, Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, enrollment from MedStar Health (compared with Wake Forest and Atrium), and occupation as a healthcare worker were independently associated with wearing a mask or face covering, among those gathering with NHM (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Frequency of respondents who reported observing specific recommended safeguards to prevent COVID-19 among respondents who reported gathering with people outside their immediate household over Thanksgiving and the winter holidays. The six feet apart question was not asked in the winter holiday survey

Table 2.

Logistic regression models predicting mask wearing during gatherings, among participants who gathered with non-household members at Thanksgiving, 2020 (n = 9560) and over the winter holiday, 2020–2021 (n = 18592)

| Variable | Thanksgiving | Winter holiday | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | Odds ratio (95% CI) | p-value | |

| Sex (men vs. women) | 1.13 (1.02, 1.24) | 0.2503 | 1.12 (1.01, 1.23) | 0.0258 |

| Age group | ||||

| Age < 30 vs. ≥ 70 years | 0.38 (0.3, 0.47) | < 0.0001 | 0.36 (0.28, 0.45) | < 0.0001 |

| Age 30–39 vs. ≥ 70 years | 0.42 (0.35, 0.49) | < 0.0001 | 0.41 (0.35, 0.49) | < 0.0001 |

| Age 40–49 vs. ≥ 70 years | 0.49 (0.41, 0.57) | < 0.0001 | 0.49 (0.41, 0.58) | < 0.0001 |

| Age 50–59 vs. ≥ 70 years | 0.64 (0.55, 0.75) | < 0.0001 | 0.63 (0.54, 0.74) | < 0.0001 |

| Age 60–69 vs. ≥ 70 years | 0.73 (0.62, 0.85) | 0.0028 | 0.72 (0.61, 0.84) | < 0.0001 |

| Study site | ||||

| Atrium vs. MedStar | 0.61 (0.47, 0.78) | < 0.0001 | 0.6 (0.46, 0.77) | < 0.0001 |

| New Hanover vs. MedStar | 0.76 (0.51, 1.15) | 0.1466 | 0.76 (0.5, 1.15) | 0.1911 |

| Wake Forest vs. MedStar | 0.68 (0.53, 0.87) | < 0.0001 | 0.66 (0.52, 0.85) | 0.0013 |

| WakeMed vs. MedStar | 0.78 (0.56, 1.10) | 0.0504 | 0.7 0(0.49, 1.00) | 0.0520 |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic black or African American vs non-Hispanic white | 2.71 (2.11, 3.48) | < 0.0001 | 2.54 (1.96, 3.28) | < 0.0001 |

| Hispanic vs non-Hispanic White | 1.45 (1.08, 1.96) | 0.1604 | 1.43 (1.06, 1.93) | 0.0208 |

| Other vs non-Hispanic white | 1.38 (1.09, 1.76) | 0.2359 | 1.36 (1.06, 1.75) | 0.0161 |

| Healthcare worker (Y vs. N) | 1.31 (1.18, 1.44) | < 0.0001 | 1.31 (1.19, 1.45) | < 0.0001 |

| Pre-gathering COVID-19 test (Y vs. N) | 1.23 (1.09, 1.39) | 0.1449 | 1.25 (1.1, 1.42) | 0.0006 |

Based on separate logistic regression models at Thanksgiving and the winter holidays, adjusted for all variables listed

Discussion

This survey provides a unique snapshot of behaviors associated with the Thanksgiving and WH seasons among persons in the eastern US. A large percentage of respondents (47.1%) reported gathering with members outside their immediate household over Thanksgiving and an even larger percentage (69.3%) did so over the longer WH. Among those who gathered with NHM, adherence to COVID-19 transmission prevention strategies other than handwashing or using hand sanitizer, were infrequent. Notably, the majority of people who gathered did not wear masks, one of the most important prevention strategies [11]. It is recognized that continually wearing masks is difficult since many holiday activities are centered upon eating which requires removal of masks. Even given the reality of the necessity to frequently remove masks for eating, our data raise concerns that consistent use of masks may not have occurred at times other than meals. In general, older participants, participants of non-Hispanic Black or African American race, Hispanic or Latino ethnicity, and those living in the urban DC area were less likely to gather with NHM and more likely to adhere to mask wearing during these gatherings than younger and non-Hispanic White participants and those from other sites. This observation suggests that holiday behaviors were modified in those groups in recognition of the fact that older age, racial minority groups, and Hispanic or Latino ethnicity are major risk factors for severe COVID-19 infection [2]. In contrast, respondents aged < 30 years old were most likely to attend gatherings with NHM, consistent with the hypothesis that many younger persons consider themselves to be at low risk for infection, especially serious infection [12]. Following Thanksgiving travel and gatherings [7], an ongoing increase in COVID-19 cases occurred across the US and that surge accelerated after the WH season [10]. Although a causal relationship was not established, lack of compliance with recommended prevention guidance, as was demonstrated by our survey, may have been a factor in this increase.

Several of our observations are consistent with a similar survey from Johns Hopkins which targeted Thanksgiving travel only [13]. In this survey of 7905 individuals from ten US states, 25.9% of respondents spent Thanksgiving outside their own home and 27.3% celebrated Thanksgiving with at least one NHM. Of note, mask wearing was practiced by nearly two-thirds of those who gathered with NHM or who traveled outside the home for Thanksgiving.

Maintaining high levels of adherence with public health guidelines and instructions is often challenging and is dependent upon multiple sociodemographic variables [14]. A recently published research letter examined changes in reported adherence with non-pharmaceutical interventions (NPI) for mitigation of COVID-19 in the US [15]. Using national surveillance data from the Coronavirus Tracking Survey for the period of April to November of 2020, those authors noted that there was a significant decrease in the NPI adherence index from 70 to 60% during the study period which ended in late November (i.e., around Thanksgiving) [15]. Protective behaviors for which adherence decreased over time included remaining at home except for essential activities, avoiding contact with members outside their household, and not having visitors in the home, all of which were “risk behaviors” assessed by the CCRP study cohort during the Thanksgiving and WH seasons.

An increased proportion of our survey participants chose to gather with members outside their immediate household over the WH season as compared to Thanksgiving. Possibilities for this observation include the longer WH season allowing more opportunity to hold gatherings with NHM, “pandemic fatigue” [16] including a general decline with observance of distancing and interaction guidelines over time [15, 17], and the desire of many Americans to participate in traditional holiday gatherings even in the face of strong recommendations not to do so [2, 4, 8]. It remains unclear as to what extent COVID-19 pandemic fatigue, coupled with increasing proportions of the population being vaccinated, will influence behaviors over the summer 2021 holidays. However, it is important to recognize that incomplete attainment of population immunity due to lack of vaccine confidence [18], combined with the emergence of more transmissible and potentially vaccine-resistant variants [19, 20], means that adherence to protective behaviors may still be important for some time to come. That message may require further refinement since guidelines about travel, gatherings, and “safeguard behaviors” were repeatedly emphasized prior to the Thanksgiving and WH [2, 4, 8], yet many persons in our study cohort failed to observe those guidelines and behaviors.

Our surveys had several limitations. Participants in the CCRP are restricted geographically to the mid-Atlantic and southeastern US. Behaviors of that population of participants may differ from those living in other areas of the US or the world. The survey is based on self-reported data which cannot be independently verified for accuracy. Participation in the CCRP and the mini-survey completion were voluntary, and the mini-surveys were more likely to be completed by older participants, men, and non-healthcare workers than their counterparts. Thus, the motivations of those choosing to participate and respond may differ from that of the general population. The specific questions asked were not identical to the CDC guidelines; for example, CDC recommended consideration of SARS-CoV-2 testing only prior to travel, not routinely before attending a gathering [8]. The size of the gatherings and the exact number of NHM at those gatherings were not quantified. The two surveys encompassed holidays of differing lengths of time (4-days for Thanksgiving vs. over 2-weeks for the winter holidays). Lastly, the survey did not inquire about plans for post-holiday COVID-19 testing or whether those participating in gatherings with NHM intended to quarantine prior to travel or for 14 days afterward.

In conclusion, despite warnings from public health authorities that Thanksgiving and WH season travel and participation in gatherings with NHM might exacerbate the evolving surge in COVID-19 cases [2, 4, 8], about half of respondents chose to travel and pursue traditional gatherings. In addition, only ~ 40% of study participants (37.3% at Thanksgiving and 41.9% during the winter holidays) reported wearing a mask or face covering when gathering with others outside their household. These data raise questions about whether inadequate adoption of recommended safe COVID-19 behaviors over the holidays may have contributed to the well-documented post-holiday surge in COVID-19 cases, and highlight the need for more effective ways to promote all recommended safe COVID-19 behaviors in the future. In conjunction with vaccination, the ongoing selective utilization of preventive behaviors may be important to ensure that increases in COVID-19 infections do not occur as pre-pandemic activities are resumed [21].

Acknowledgements

The COVID-19 Community Research Partnership gratefully acknowledges the commitment and dedication of the study participants. Programmatic, laboratory, and technical support was provided by Vysnova Partners, Inc., Javara, Inc., and Oracle Corporation. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement by, CDC/HHS, or the U.S. Government.

Wake Forest School of Medicine: John Walton Sanders MD, MPH, Thomas F Wierzba PhD, MPH, David Herrington MD, MHS, Mark A. Espeland PhD, Morgana Mongraw-Chaffin PhD, Alain Bertoni MD, Martha A. Alexander-Miller PhD, Allison Mathews PhD, Iqra Munawar MS, Austin Lyles Seals MS, Brian Ostasiewski, Christine Ann Pittman Ballard MPH, Metin Gurcan, PhD, Alexander Ivanov, MD, Allison Matthews, PhD, Giselle Melendez Zapata, MD, Marlena Westcott, PhD, Karen Blinson, Laura Blinson, Douglas McGlasson, Mark Mistysyn, Donna Davis, Lynda Doomy, Perrin Henderson, MS, Alicia Jessup, Kimberly Lane, Beverly Levine, PhD, Jessica McCanless, MS, Sharon McDaniel, Kathryn Melius, MS, Christine O’Neill, Angelina Pack, RN, Ritu Rathee, RN, Scott Rushing, Jennifer Sheets, Sandra Soots, RN, Michele Wall, Samantha Wheeler, John White, Lisa Wilkerson, Rebekah Wilson, Kenneth Wilson, Deb Burcombe. Atrium Health: Michael S. Runyon, MD, MPH, Lewis H. McCurdy, MD, Michael A. Gibbs, MD, Yhenneko J. Taylor, PhD, Lydia Calamari, MD, Hazel Tapp, PhD, Amina Ahmed, MD, Michael Brennan, DDS, Lindsay Munn, PhD, RN, Keerti L. Dantuluri, MD, Timothy Hetherington, MS, Lauren C. Lu, Connell Dunn, Melanie Hogg, MS, CCRA, Andrea Price, Mariana Leonidas, Laura Staton, Kennisha Spencer, MPH, Melinda Manning, Whitney Rossman, MS, Frank Gohs, MS, Anna Harris, MPH, Bella Gutnik, MS, Jennifer S. Priem, PhD, MA, Ryan Burns, MS. MedStar Health Research Institute: William S. Weintraub, MD , Kristen Miller, DrPH, CPPS, , Chris Washington, Allison Moses, Sarahfaye Dolman, Julissa Zelaya-Portillo, John Erkus, Joseph Blumenthal, Ronald E. Romero Barrientos, Sonita Bennett, Shrenik Shah, Shrey Mathur, Christian Boxley, Paul Kolm, PhD, Long La, Cheng Zhang, PhD, Eva Hochberger, Ella Franklin, Deliya Wesley, Naheed Ahmed. Tulane University: Richard Oberhelman, MD, Joseph Keating, PhD, Patricia Kissinger, PhD, John Schieffelin, MD, Joshua Yukich, PhD, Andrew “AJ” Beron, MPH, Devin Hayes, BS, Johanna Teigen, MPH. University of Maryland School of Medicine: Karen Kotloff, MD, Wilbur Chen, MD, MS, DeAnna Friedman-Klabanoff, MD, Andrea Berry, MD, Helen Powell, PhD, Lynnee Roane, MS, RN, Reva Datar, MPH. University of Mississippi: Adolfo Correa, MD, PhD, Leandro Mena, MD, MPH, Bhagyashri Navalkele, MD, Yuan-I Min, PhD, Alexandra Castillo, MPH, Lori Ward, PhD, MS, Robert P. Santos, MD, Courtney Gomillia, MS-PHS, Pramod Anugu, Yan Gao, MPH, Jason Green, Ramona Sandlin, RHIA, Donald Moore, MS, Lemichal Drake, Dorothy Horton, RN. Wake Med Health and Hospitals: William H. Lagarde, MD, LaMonica Daniel, BSCR. New Hanover Regional Medical Center: Patrick D. Maguire, MD, Charin L. Hanlon, MD, Lynette McFayden, RN, Isaura Rigo, MD, Kelli Hines, Lindsay Smith, Alexa Drilling, Monique Harris, Belinda Lissor, Vivian Cook, Maddy Eversole, Terry Herrin, Dennis Murphy, Lauren Kinney, Polly Diehl, Nicholas Abromitis, Tina St. Pierre, Judy Kennedy BSCS, MBA, Lauren Kinney, BS, Bill Heckman, Denise Evans, Vivian Cook, Maddy Eversole, Julian March, Ben Whitlock, Wendy Moore. Vidant Health: Shakira Henderson, PhD, DNP, MS, MPH, Thomas R. Gallaher, MD, Michael Zimmer, PhD, Danielle Oliver, Tina Dixon, Kasheta Jackson, Martha Reavis, Monica Menon, Brandon Bishop, Rachel Roeth, Mathew Johanson, Alesia Ceaser, Amada Fernandez, Carmen Williams, Jeremiah Hargett, Keeaira Boyd, Kevonna Forbes, Latasha Thomas, Markee Jenkins, Monica Coward, Derrick Clark, Omeshia Frost, Angela Darden, Lakeya Askew, Sarah Phipps, Victoria Barnes. Campbell University School of Osteopathic Medicine: Robin King-Thiele, DO, Terri S. Hamrick, PhD, Abdalla Ihmeidan, MHA (Campbell University School of Osteopathic Medicine), Chika Okafor, MD (Cape Fear Valley Medical Center), Regina B. Bray Brown, MD (Harnett Health System, Inc.), Poornima Vinod, MD (Southeastern Health), Lawrence Klima, MD (Harnett Health System), Amber Brewster, MD (Harnett Health System), Danius Bouyi, DO (Harnett Health System), Katrina Lamont, MD (Harnett Health System), Kazumi Yoshinaga, DO (Harnett Health System), A. Suman Peela, MD (Southeastern Health System), Giera Denbel, MD (Southeastern Health System), Jason Lo, MD: Southeastern Health System, Mariam Mayet-Khan, DO (Southeastern Health System), Akash Mittal, DO (Southeastern Health System), Reena Motwani, MD (Southeastern Health System), Mohamed Raafat, MD (Southeastern Health System), Evan Schultz, DO (Cumberland County Hospital System, Cape Fear Valley), Aderson Joseph, MD (Cumberland County Hospital System, Cape Fear Valley), Aalok Parkeh, DO (Cumberland County Hospital System, Cape Fear Valley), Dhara Patel, MD (Cumberland County Hospital System, Cape Fear Valley), Babar Afridi, DO (Cumberland County Hospital System, Cape Fear Valley). George Washington University Data Coordinating Center: Diane Uschner, PhD, Sharon L Edelstein, ScM, Michele Santacatterina, PhD, Greg Strylewicz, PhD, Brian Burke, MS, Mihili Gunaratne, MPH, Meghan Turney, MA, Shirley Qin Zhou, MS. Oracle Corporation: Rebecca Laborde, PhD. Vysnova Partners: Anne McKeague, PhD, Grace Tran, MPH, Johnathan Ward, Joyce Dieterly, MPH, Nana Darko, MPH, Kimberly Castellon, Isabella Malcolm, Ryan Brink, MS. Javara Inc: Atira Goodwin. External Advisory Council: Ruth Berkelman MD, Emory, Kimberly Hanson MD, U of Utah, Scott Zeger PhD, Johns Hopkins, Cavan Reilly PhD, U. of Minnesota, Kathy Edwards MD, Vanderbilt, Helene Gayle MD/MPH, Chicago Community Trust.

Author Contributions

Concept/design: JEP, JWS, DMH, TFW. Data analysis/interpretation: SLE, ALS, DMH. Drafting article: JEP, SLE, DMH. Critical revision of article: JEP, SLE, DMH, JWS, WHL, WSW, IDP, SS. Approval of article: all authors. Statistics: SLE, ALS. Data collection: all authors.

Funding

This publication was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) [Contract #75D30120C08405] and the CARES Act of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) [Contract # NC DHHS GTS #49927]. Fifty percent of the current project was funded by the CDC/HHS award and fifty percent by the CARES Act/HHS award. The Partnership is listed in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04342884).

Data Availability

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

JEP owns common stock in Pfizer, Inc. The other authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

The study was reviewed and approved by the Wake Forest School of Medicine Institutional Review Board. This activity was also reviewed by the CDC and was conducted consistent with applicable federal law and CDC policy.

Consent to Participate

All participants in the COVID-19 Community Research Partnership provided informed consent for participation.

Consent for Publication

Not applicable. No identifying data from any individual person is contained in the manuscript.

Footnotes

Trial Registration: The COVID-19 Community Research Partnership is listed in clinicaltrials.gov (NCT04342884).

Members of The COVID-19 Community Research Partnership Study Group are listed in Acknowledgement section.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

James E. Peacock, Jr., Email: jpeacock@wakehealth.edu

for The COVID-19 Community Research Partnership Study Group:

John Walton, Mark A. Espeland, Morgana Mongraw-Chaffin, Alain Bertoni, Martha A. Alexander-Miller, Allison Mathews, Iqra Munawar, Brian Ostasiewski, Christine Ann Pittman Ballard, Metin Gurcan, Alexander Ivanov, Allison Matthews, Giselle Melendez Zapata, Marlena Westcott, Karen Blinson, Laura Blinson, Douglas McGlasson, Mark Mistysyn, Donna Davis, Lynda Doomy, Perrin Henderson, Alicia Jessup, Kimberly Lane, Beverly Levine, Jessica McCanless, Sharon McDaniel, Kathryn Melius, Christine O’Neill, Angelina Pack, Ritu Rathee, Scott Rushing, Jennifer Sheets, Sandra Soots, Michele Wall, Samantha Wheeler, John White, Lisa Wilkerson, Rebekah Wilson, Kenneth Wilson, Deb Burcombe, Lewis H. McCurdy, Michael A. Gibbs, Yhenneko J. Taylor, Lydia Calamari, Hazel Tapp, Amina Ahmed, Michael Brennan, Lindsay Munn, Keerti L. Dantuluri, Timothy Hetherington, Lauren C. Lu, Connell Dunn, Melanie Hogg, Andrea Price, Mariana Leonidas, Laura Staton, Kennisha Spencer, Melinda Manning, Whitney Rossman, Frank Gohs, Anna Harris, Bella Gutnik, Jennifer S. Priem, Ryan Burns, Kristen Miller, Chris Washington, Allison Moses, Sarahfaye Dolman, Julissa Zelaya-Portillo, John Erkus, Joseph Blumenthal, Ronald E. Romero Barrientos, Sonita Bennett, Shrenik Shah, Shrey Mathur, Christian Boxley, Paul Kolm, La Long, Cheng Zhang, Eva Hochberger, Ella Franklin, Deliya Wesley, Naheed Ahmed, Richard Oberhelman, Joseph Keating, Patricia Kissinger, John Schieffelin, Joshua Yukich, Andrew J. Beron, Devin Hayes, Johanna Teigen, Karen Kotloff, Wilbur Chen, DeAnna Friedman-Klabanoff, Andrea Berry, Helen Powell, Lynnee Roane, Reva Datar, Leandro Mena, Bhagyashri Navalkele, Yuan I. Min, Alexandra Castillo, Lori Ward, Robert P. Santos, Courtney Gomillia, Pramod Anugu, Yan Gao, Jason Green, Ramona Sandlin, Donald Moore, Lemichal Drake, Dorothy Horton, LaMonica Daniel, Charin L. Hanlon, Lynette McFayden, Isaura Rigo, Kelli Hines, Lindsay Smith, Alexa Drilling, Monique Harris, Belinda Lissor, Vivian Cook, Maddy Eversole, Terry Herrin, Dennis Murphy, Lauren Kinney, Polly Diehl, Nicholas Abromitis, Tina St. Pierre, Judy Kennedy, Lauren Kinney, Bill Heckman, Denise Evans, Vivian Cook, Maddy Eversole, Julian March, Ben Whitlock, Wendy Moore, Shakira Henderson, Thomas R. Gallaher, Michael Zimmer, Danielle Oliver, Tina Dixon, Kasheta Jackson, Martha Reavis, Monica Menon, Brandon Bishop, Rachel Roeth, Mathew Johanson, Alesia Ceaser, Amada Fernandez, Carmen Williams, Jeremiah Hargett, Keeaira Boyd, Kevonna Forbes, Latasha Thomas, Markee Jenkins, Monica Coward, Derrick Clark, Omeshia Frost, Angela Darden, Lakeya Askew, Sarah Phipps, Victoria Barnes, Robin King-Thiele, Terri S. Hamrick, Abdalla Ihmeidan, Chika Okafor, Regina B. Bray Brown, Poornima Vinod, Lawrence Klima, Amber Brewster, Danius Bouyi, Katrina Lamont, Kazumi Yoshinaga, A. Suman Peela, Giera Denbel, Jason Lo, Mariam Mayet-Khan, Akash Mittal, Reena Motwani, Mohamed Raafat, Evan Schultz, Aderson Joseph, Aalok Parkeh, Dhara Patel, Babar Afridi, Diane Uschner, Michele Santacatterina, Greg Strylewicz, Brian Burke, Mihili Gunaratne, Meghan Turney, Qin Zhou, Rebecca Laborde, Anne McKeague, Grace Tran, Johnathan Ward, Joyce Dieterly, Nana Darko, Kimberly Castellon, Isabella Malcolm, Ryan Brink, Atira Goodwin, Ruth Berkelman, Kimberly Hanson, Scott Zeger, Johns Hopkins, Cavan Reilly, Kathy Edwards, and Helene Gayle

References

- 1.The COVID Tracking Project. (2021). Totals for the US. https://covidtracking.com/data/national. Accessed May 21

- 2.Honein MA, Christie A, Rose DA, et al. Summary of guidance for public health strategies to address high levels of community transmission of SARS-CoV-2 and related deaths, December 2020. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Reports. 2020;69(49):1860–1867. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6949e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kelleher SR. (2020). Thanksgiving travel will create the next big superspreader event, experts fear. Forbes. November 6, 2020. https://www.forbes.com/sites/suzannerowankelleher/2020/11/06/thanksgiving-travel-will-create-the-next-big-superspreader-event-fear-experts/?sh=7147777216df. Accessed Dec 8 2020

- 4.Centers for Disease Control. (2020). Celebrating thanksgiving. Updated November 19, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/daily-life-coping/everyone_can_make_thanksgiving_safer.html.pdf. Accessed Dec 8 2020

- 5.Koenig D. (2020). Holiday air travel surges despite dire health warnings. Associated Press News. November 30, 2020. https://apnews.com/article/travel-air-travel-health-thanksgiving-holidays-17b2945ee64aedcc7a3ad66e9d3671aa. Accessed Dec 9 2020

- 6.Plater R. (2020). The post-Thanksgiving COVID-19 surge is here: What to expect now. Healthline. December 10, 2020. https://www.healthline.com/health-news/the-post-thanksgiving-covid-19-surge-is-here-what-to-expect-now. Accessed Dec 15 2020

- 7.Tanne JH. Covid-19: US faces surge upon a surge. British Medical Journal. 2020;371:4693. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m4693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control. (2020). Holiday celebrations and small gatherings. Updated December 11, 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/downloads/daily-life-coping/everyone_can_make_winter_holidays_safer.pdf. Accessed Dec 15 2020

- 9.Mitropoulos A. (2020). Potential post-holiday COVID-19 surge could have catastrophic impact, experts warn. December holiday travel and gatherings could result in a COVID-19 surge. ABC News. December 23, 2020. https://abcnews.go.com/Health/potential-post-holiday-covid-19-surge-catastrophic-impact/story?id=74859998. Accessed Jan 11 2021

- 10.Centers for Disease Control. (2021). COVID data tracker. Trends in number of COVID-19 cases and deaths in the US reported to CDC, by state/territory. https://covid.cdc.gov/covid-data-tracker/#trends_dailytrendscases. Accessed Jun 16 2021

- 11.Qaseem A, Etxeandia-Ikobaltzeta I, Yost J, et al. Use of N95, surgical, and cloth masks to prevent COVID-19 in health care and community settings: Living practice points from the American College of Physicians (version 1) Annals Internal Medicine. 2020;173(8):642–649. doi: 10.7326/M20-3234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Abbasi J. Younger adults caught in COVID-19 crosshairs as demographics shift. JAMA. 2020;324(21):2141–2143. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.21913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mehta SH, Clipman SJ, Wesolowski A, Solomon SS. There’s no place like home for the holidays: Travel and SARS-CoV-2 testing positivity following Thanksgiving weekend. Preprint retrieved from medRxiv. 10.1101/2020. 12.22.20248719

- 14.Weiss BD, Paasche-Orlow MK. Disparities in adherence to COVID-19 public health recommendations. Health literacy research and practice. 2020;4(3):171–173. doi: 10.3928/24748307-20200723-01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crane MA, Shermock KM, Omer SB, Romley JA. Change in reported adherence to nonpharmaceutical interventions during the COVID-19 pandemic, April-November 2020. JAMA. 2021;325(9):883–885. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.World Health Organization. (2020). Pandemic fatigue: Reinvigorating the public to prevent COVID-https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/335820/WHO-EURO-2020-1160-40906-55390-eng.pdf. Accessed Feb 24 2021

- 17.Hutchins HJ, Wolff B, Leeb R, et al. (2020). COVID-19 mitigation behaviors by age group—United States, April–June 2020. Morbidity Mortality Weekly Reports, 69(43), 1584–1590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Fisher KA, Bloomstone SJ, Walder J, Crawford S, Fouayzi H, Mazor KM. Attitudes toward a potential SARS-CoV-2 vaccine. A survey of US adults. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2020;173(12):964–973. doi: 10.7326/M20-3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdool Karim SS, de Oliveira T. New SARS-CoV-2 variants––-Clinical, public health, and vaccine implications. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;384(19):1866–1868. doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2100362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mascola JR, Graham BS, Fauci AS. SARS-CoV-2 viral variants––tackling a moving target. JAMA. 2021;325(13):1261–1262. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.2088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Patel MD, Rosenstrom E, Ivy JS, et al. Association of simulated COVID-19 vaccination and non-pharmaceutical interventions with infections, hospitalizations, and mortality. JAMA Network Open. 2021;4(6):e2110782. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2021.10782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.